Political Instability And Uncertainty Loom Large In Nepal

By gaurab shumsher thapa.

- February 16, 2021

This article was originally published in South Asian Voices.

Nepal’s domestic politics have been undergoing a turbulent and significant shift. On December 20, 2020, at the recommendation of Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli, President Bidya Devi Bhandari dissolved the House of Representatives, calling for snap elections in April and May 2021. Oli’s move was a result of a serious internal rift within the ruling Nepal Communist Party (NCP) that threatened to depose him from power. Opposition parties and other civil society stakeholders have condemned the move as unconstitutional and several writs have been filed against the move at the Supreme Court (SC) with hearings underway. Massive protests have taken place condemning the prime minister’s move. If the SC reinstates the parliament, Oli is in course to lose the moral authority to govern and could be subject to a vote of no-confidence. If the SC validates his move, it is unclear if he would be able to return to power with a majority.

The formation of a strong government after decades of political instability was expected to lead to a socioeconomic transformation of Nepal. Regardless of the SC’s decision, the country is likely to see an escalation of political tensions in the days ahead. The internal rift that led to the December parliamentary dissolution and the political dimensions of the current predicament along with the domestic and geopolitical implications of internal political instability will lead to a serious and long-term weakening of Nepal’s democratic fabric.

Power Sharing and Legitimacy in the NCP

Differences between NCP chairs Oli and former Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal have largely premised on a power-sharing arrangement, leading to a vertical division in the party. In the December 2017 parliamentary elections, a coalition between the Oli-led Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist Leninist or UML) and the Dahal-led Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Center or MC) won nearly two-thirds of the seats. In May 2018, both parties merged to form the NCP. However, internal politics weakened this merger. While both the factions claim to represent the authentic party, the Election Commission has sought clarifications from both factions before deciding on the matter. According to the Political Party Act , the faction that can substantiate its claim by providing signatures of at least 40 percent of its central committee members is eligible to get recognized as the official party. The faction that is officially recognized will get the privilege of retaining the party and election symbol, while the unrecognized faction will have to register as a new party which can hamper its future electoral prospects. A faction led by Dahal and former Prime Minister Madahav Kumar Nepal, was planning to initiate a vote of no-confidence motion against Oli but, sensing an imminent threat to his position, Oli decided to motion for the dissolution of the parliament.

Internal Party Dynamics

Several internal political dynamics have led to the current state of turmoil within the NCP. Dahal has accused Oli of disregarding the power-sharing arrangement agreed upon during the formation of NCP according to which Oli was supposed to hand over either the premiership or the executive chairmanship of the party to Dahal. In September 2020, both the leaders reached an agreement under which Oli would serve the remainder of his term as prime minister and Dahal would act as the executive chair of the party. Yet, Oli failed to demonstrate any intention to relinquish either post, increasing friction within the party. Additionally, Oli made unilateral appointments to several cabinet and government positions, further consolidating his individual authority over the newly formed NCP. He also sidelined the senior leader of the NCP and former Prime Minister Madhav Kumar Nepal, leading Nepal to side with Dahal over Oli. Consequently, Oli chose to dissolve the parliament and seek a fresh mandate rather than face a vote of no-confidence. Importantly, party unity between the Marxist-Leninist CPN (UML) and the Maoist CPN (MC) did not lead to expected ideological unification.

Domestic Politics and Geopolitics

Geopolitical factors and external actors have historically impacted Nepal’s domestic political landscape. Recently, in a bid to cement his authority over the NCP, Oli has attempted to improve ties with India—lately strained due to Nepal’s inclusion of disputed territories in its new political map—resulting in recent high-level visits from both countries. India has also provided Nepal with one million doses of COVID-19 vaccines as part of its vaccine diplomacy efforts in the region. However, while India has previously interfered in Nepal’s domestic politics , it has described the current power struggle as an “ internal matter ” to prevent backlash from Nepali policymakers and to avoid a potential spillover of political unrest.

However, India’s traditionally dominant influence in Nepal has been challenged by China’s ascendancy in recent years. Due to fears of Tibetans potentially using Nepal’s soil to conduct anti-China activities, China considers Nepal important to its national security strategy. Beijing has traditionally maintained a non-interventionist approach to foreign policy; however, this approach is gradually changing as is evident from the Chinese ambassador to Nepal’s proactive efforts to address current crises within the NCP. Nepal’s media speculates that China is in favor of keeping the NCP intact as the ideological affinity between the NCP and the Communist Party of China could help China exert its political and economic influence over Nepal.

Although China is aware of India’s traditionally influential role in Nepal, it is also skeptical of growing U.S. interest in the Himalayan state; especially considering Oli’s push for parliamentary approval of the USD $500 million Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) grant assistance from the United States to finance the construction of electrical transmission lines in Nepal. In contrast, Dahal has opposed the MCC and has described it as part of the U.S.-led Indo-Pacific Strategy to contain China. Given Nepal is a signatory to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing might prefer development projects under the BRI framework and could lobby the Nepali government to delay or reject U.S.-led projects.

Implications for Future Governance

After the political changes of 2006 which ended Nepal’s decade-long armed conflict, it was expected that political stability would usher in economic development to the country. Moreover, a strong majority government under Oli raised hopes of achieving modernization. Sadly, ruling party leaders have instead engaged in a bitter power struggle, and government corruption scandals have undermined trust in the administration.

Amidst the current turmoil within the NCP, the main opposition party, Nepali Congress (NC), is hoping that an NCP division will raise its prospects of coming to power in the future. Although the NC has denounced Oli’s move for snap elections as unconstitutional, it has also stated that it will not shy away from elections if the SC decides to dissolve the lower house. Sensing increasing instability, several royalist parties and groups have accused the government of corruption and protested on the streets for the reinstatement of the Hindu state and constitutional monarchy to reinvent and stabilize Nepal’s image and identity.

The last parliamentary elections had provided a mandate of five years for the NCP to govern the country. However, Oli decided to seek a fresh mandate, claiming that the Dahal-Nepal faction obstructed the smooth functioning of the government. Unfortunately, domestic political instability has resurfaced as the result of an internal personality rift within the party. This worsening democratic situation will not benefit either India or China—both want to circumvent potential spillover effects. Even if the SC validates Oli’s move, elections in April are not confirmed. If elections were not held within six months from the date of dissolution, a constitutional crisis could occur. If the Supreme Court overturns Oli’s decision, he could lose his position as both the prime minister and the NCP chair. Regardless of the outcome, Nepali politics is bound to face deepening uncertainty in the days ahead.

This article was originally published in South Asian Voices.

Recent & Related

About Stimson

Transparency.

- 202.223.5956

- 1211 Connecticut Ave NW, 8th Floor, Washington, DC 20036

- Fax: 202.238.9604

- 202.478.3437

- Caiti Goodman

- Communications Dept.

- News & Announcements

Copyright The Henry L. Stimson Center

Privacy Policy

Subscription Options

Research areas trade & technology security & strategy human security & governance climate & natural resources pivotal places.

- Asia & the Indo-Pacific

- Middle East & North Africa

Publications & Project Lists South Asia Voices Publication Highlights Global Governance Innovation Network Updates Mekong Dam Monitor: Weekly Alerts and Advisories Middle East Voices Updates 38 North: News and Analysis on North Korea

- All News & Analysis (Approx Weekly)

- 38 North Today (Frequently)

- Only Breaking News (Occasional)

United States Institute of Peace

Home ▶ Publications

In Nepal, Post-Election Politicking Takes Precedence Over Governance

The latest bout of coalition politics glosses over the country’s troubling drift toward further political instability.

By: Deborah Healy; Sneha Moktan

Publication Type: Analysis

This past November, Nepalis participated in the second federal and provincial election since its current constitution came into effect in 2015. With 61 percent voter turnout , notably 10 percent lower than the 2017 general elections, the polls featured a strong showing from independent candidates.

Almost half of the incumbent members of parliament — even former premiers, cabinet ministers and party leaders — lost their seats to independents or new political rivals. Amid the political instability that has wracked Nepal over the past several years, including a near constitutional crisis in 2021, the electorate appeared to be holding political leaders accountable at the ballot box for putting politicking above governing.

A Surprising Coalition in Parliament

However, what followed election day has dampened hopes for political reform or renewal. Spurred by public resentment toward the established parties, no single party or existing coalition secured a parliamentary majority. Most expected that the outgoing government, led by the Nepali Congress party, would form a new majority following a brief period of negotiation. However, talks between the Nepali Congress’ outgoing Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba and Pushpa Kamal Dahal, leader of Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist Centre (CPN-MC), broke down when the two failed to agree on who would hold the post of prime minister.

After talks with the Nepali Congress ended, Dahal, who is often known by his nom-de-guerre “Prachanda” from his time leading insurgent forces during Nepal’s decade-long civil war from 1996-2006, swiftly brokered a new alliance with his sometime rival, sometime ally KP Sharma Oli and the Communist Party of Nepal-Unified Marxist Leninist (CPN-UML). The two men agreed they would rotate the prime minister’s office between them, with Prachanda serving as prime minister first. With this agreement in hand, Prachanda was sworn in as prime minister on December 26.

Two weeks later, Prachanda was constitutionally obligated to face parliament for a confidence vote. In a surprising reversal, the Nepali Congress and other parties in the opposition announced that they, too, would support the new governing coalition — giving Prachanda a unanimous vote of confidence.

Some analysts suggest this was an attempt by the Nepali Congress to undermine Prachanda’s alliance from the outset by giving Prachanda and the CPN-MC a back-up coalition partner-in-waiting should their pact with the CPN-UML fall through. This would weaken Oli and the CPN-UML’s negotiating power in the new government. The move also dilutes parliamentary checks and balances and calls into question the opposition’s ability to independently scrutinize the actions of a prime minister and government that it helped put in place.

The unanimous vote of confidence creates issues for Prachanda as well, as he must now manage a multi-party coalition representing a spectrum from Marxists to monarchists. Meanwhile, Nepali citizens once again are frustrated and disappointed to see a government formed by parties that have lost a significant number of electoral seats acquire the lion’s share of cabinet positions.

Ongoing Struggle to Implement Federalism

Nepal’s political theme for the last decade has been precarity, and this latest political theater comes amid some worrying trends. Governments rarely run full terms and politicians have played musical chairs with political appointments. Meanwhile, closed-door power-grabs have undermined the electorate’s will. In the seven years since Nepal became a federal state, any initial optimism for the success of federalism has largely waned.

In 2021, only 32 percent of Nepalese said they were satisfied with provincial governments, and chief ministers have complained about the federal government’s reluctance to implement federalism. Provincial assemblies have received limited funding, resources and capacity building support to enable them to be an effective tier of government.

With the outcomes of the 2022 general elections, federalism will continue to face challenges. The governing coalition’s inclusion of the Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP), which served as an umbrella party for the election’s independent candidates, will likely disrupt decisions affecting provincial governments. The RSP are anti-federalism — they did not field any candidates for the provincial government elections, and there were incidents on election day where their supporters visibly rejected Provincial Assembly ballot papers.

With such divergent views within the government, it remains to be seen whether provincial governments will get the support they need to provide effective governance or whether federalism will be able to plant stronger roots in the governance system of Nepal.

Walking a Geopolitical Tightrope

Nepal is wedged between China and India, meaning the country must maintain a delicate balancing act to keep amiable relationships with both powers. While the “left-leaning” parties such as CPN-UML and CPN-MC, who have traditionally been seen as being close to China, seek to strengthen those ties, Nepal has deep historical, cultural and religious ties to India.

However, in recent years, the relationship between Nepal and India has at times been fractious — especially when communist parties have occupied the prime minister's office in Nepal and the right-leaning Modi has occupied the prime minister's office in Delhi.

When Nepal was reeling from devastating earthquakes in 2015, there was an unofficial Indian blockade at the border later that year, which soured India-Nepal relations and saw Oli look to Beijing for support. And in 2019-2020, nationalistic sentiment both in Delhi and Kathmandu — when Oli was prime minister — came to the fore over disputed territories along the border, with both governments re-drawing the demarcations set out in the Sugauli Treaty of 1816.

While accusations of foreign interference in domestic politics have increased over recent years, the domestic political flux has actually made it difficult for foreign powers to negotiate, influence or broker power dynamics in a sustained manner. With fluid alliances and an average of just under one prime minister per year for the past 15 years in Nepal, neither China nor India seems to be able to pull geopolitical strings in the country for a sustained period.

The rollercoaster fate of the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) compact further emphasizes this point. The MCC agreement provides $500 million in U.S. grants to support programs to improve electricity and transportation in Nepal. And while the previous Nepali Congress-led government got MCC ratification over the line, it was only after months of protests against the MCC that were fuelled largely by misformation. Now that the MCC is ratified, high-level U.S. officials have been visiting Nepal in quick succession .

While Prachanda’s political victory was welcomed by media outlets in Beijing, given the diverse political ideologies among the coalition, foreign powers near and far will likely struggle to identify true power brokers and influence national politics. On the other hand, this diplomatic uncertainty also makes it harder to build long-term sustained international relations.

Disinformation Continues to Fuel Conflict

In addition to Nepal’s political instability and diplomatic balancing act, social media has been rife with false information on various issues over the past few years, most notably the MCC. Disinformation around the MCC stoked concerns around Nepal’s sovereignty and fuelled several protests in Nepal in 2022.

The elections saw an uptick in this misinformation and disinformation, with doctored images, forged documents and false claims regarding various political leaders, as well as the former U.S. ambassador to Nepal, circulating over social media. This only served to stoke further allegations of U.S. interference in Nepal’s politics. Should this narrative be allowed to continue, it has the potential to fuel further anti-American sentiment in Nepal.

As political parties, politicians and allegedly foreign actors continue to utilize social media to control or twist narratives, senior journalists fear that the worst is yet to come for Nepal in terms of organized disinformation campaigns. In a country where political dissatisfaction has been simmering for decades, and with the government preoccupied with smoothing over the differences in the coalition, such campaigns could trigger political unrest and violence.

The Lack of Women on the Ballot

Nepal’s parliamentary electoral system is split: Voters are asked to choose from a list of candidates for their district’s parliamentary seat as well as for a political party in the country’s proportional representation (PR) system. 165 members of parliament are directly elected to parliament, while the remaining 110 seats are filled based on parties’ vote share in PR list results.

Out of the 4,611 candidates who directly contested seats in the federal parliament, only 225 (9.3 percent) were women. Of this number, only 25 were fielded by the main political parties. The lack of female candidates on the ballot resulted in only nine being directly elected in the country’s first-past-the-post system — only three more than in 2017.

To meet the constitutionally mandated one-third female representation rule, political parties fielded more female candidates under the PR list system. The PR list system was meant to provide electoral opportunities to women and candidates from marginalized and indigenous communities — but members of parliament can only serve one term through the PR list. The intent was to give these underrepresented groups a chance to build experience, after which they could contest a directly elected seat.

Instead, Nepal’s major political parties have repeatedly taken the easy option of nominating new female candidates to the PR list system to ensure they meet the one-third quota rather than nominate experienced women for directly elected seats.

While the parties are fulfilling the constitutional obligations by meeting the quota, there seems to be little long-term investment in developing women leaders. Going forward, the parties need to do more to increase female and marginalized community representation and promote a more representative and inclusive parliament that reflects the spirit of the constitution — not one dominated by the same figures who wish to maintain the status quo.

Where Does Nepal Go from Here?

The past two decades have yielded significant transitions for Nepal: a peaceful resolution to the decade-long Maoist conflict, as well as the end of monarchy and the promulgation of a new constitution that upheld secularism, inclusion and federalism.

But this positive momentum seems to now be staggering, with the same actors from several decades ago largely interested in maintaining a status quo while inflation steadily rises and federalism struggles.

While political forecasting in Nepal continues to be as accurate as reading tea leaves, there continues to be concerns about prolonged political instability — as can be seen by the fragility of the current coalition, which is already in danger of collapsing with the withdrawal of RSP, the third largest coalition partner.

Throw in the upcoming and contentious question of which party gets to nominate the president, and the Nepali people are once again left to witness blatant politicking at the expense of timely attention to economic and governance challenges.

Meanwhile, the Finance Ministry has warned that funding to provincial and local governments could be cut as a result of economic concerns. The entire federal system will be undermined if governments cannot deliver on services and development. Federalism was envisaged as a vehicle for economic development and if it flounders, it could have an impact on Nepal’s graduation to a lower middle-income country in 2026 based on the World Bank’s projections .

Still, the U.S. government sees Nepal as one of two places in Asia with an excellent opportunity for inclusion in the Partnership for Democratic Development. And with high-profile visits from U.S. government officials and scheduled high-profile visits from European governments on the way, there is an opportunity for the international community to urge Nepal’s government to stop politicking and start governing so that Nepal can flourish as a truly democratic nation that respects the rights of the many and not the few.

Deborah Healy is the senior country director for Nepal at the National Democratic Institute.

Sneha Moktan is the program director for Asia-Pacific at the National Democratic Institute.

Related Publications

China’s Engagement with Smaller South Asian Countries

Wednesday, April 10, 2019

By: Nilanthi Samaranayake

When the government of Sri Lanka struggled to repay loans used to build the Hambantota port, it agreed to lease the port back to China for 99 years. Some commentators have suggested that Sri Lanka, as well as other South Asian nations that have funded major infrastructure projects through China’s Belt and Road Initiative, are victims of “China’s debt-trap diplomacy.” This report finds that the reality is...

Type: Special Report

Environment ; Economics

Nonformal Dialogues in National Peacemaking

Wednesday, October 18, 2017

By: Derek Brown

Nonformal dialogues offer complementary approaches to formal dialogues in national peacemaking efforts in contexts of conflict. As exemplified by the nonformal dialogues in Myanmar, Lebanon, and Nepal examined in this report, nonformal dialogues are able to...

Type: Peaceworks

Mediation, Negotiation & Dialogue ; Peace Processes

Connecting Civil Resistance and Conflict Resolution

Thursday, August 10, 2017

By: Maria J. Stephan

In 2011, the world watched millions of Egyptians rally peacefully to force the resignation of their authoritarian president, Hosni Mubarak. “When Mubarak stepped down … we realized we actually had power,"...

Nonviolent Action ; Mediation, Negotiation & Dialogue

Reconciliation and Transitional Justice in Nepal: A Slow Path

Wednesday, August 2, 2017

In 2006, the government of Nepal and Maoist insurgents brokered the end of a ten-year civil war that had killed thousands and displaced hundreds of thousands. The ensuing Comprehensive Peace Agreement laid out a path to peace and ushered in a coalition government. Nepal’s people were eager to see the fighting end. Their political leaders, however...

Type: Peace Brief

Reconciliation ; Justice, Security & Rule of Law

- Culture & Lifestyle

- Madhesh Province

- Lumbini Province

- Bagmati Province

- National Security

- Koshi Province

- Gandaki Province

- Karnali Province

- Sudurpaschim Province

- International Sports

- Brunch with the Post

- Life & Style

- Entertainment

- Investigations

- Climate & Environment

- Science & Technology

- Visual Stories

- Crosswords & Sudoku

- Corrections

- Letters to the Editor

- Today's ePaper

Without Fear or Favour UNWIND IN STYLE

What's News :

- Madhesh government change

- Policy corruption

- Quake-hit settlements

- Kathmandu waste disposal

- Cooperatives fraud probe committee

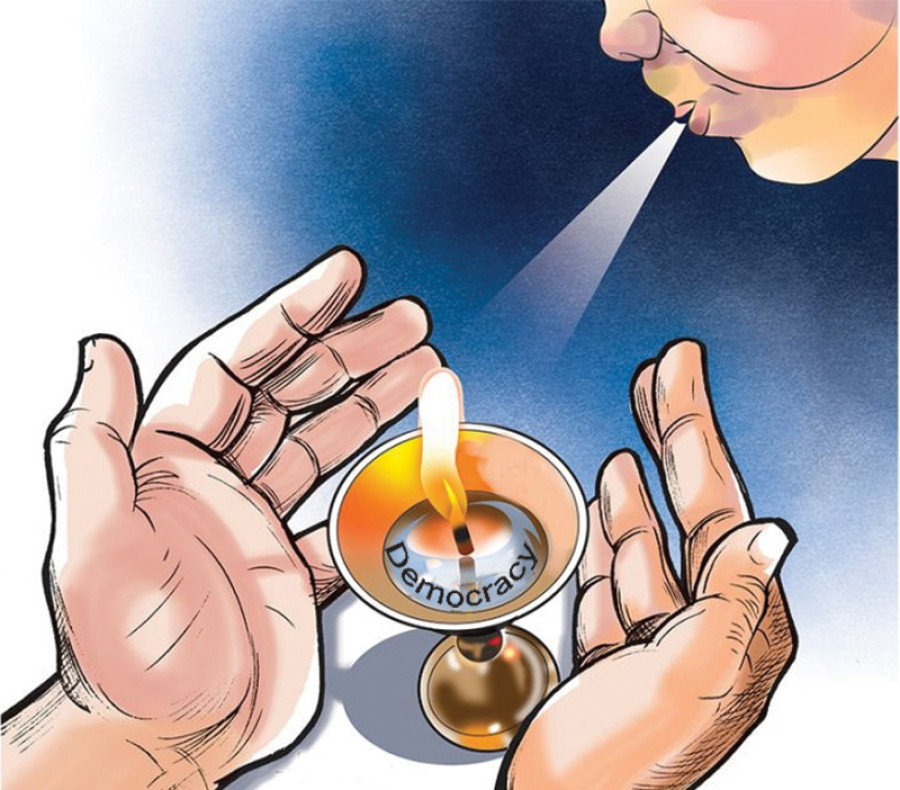

Nepal’s democracy challenges

Seventy years ago, on this day (Falgun 7) Nepal ended 104-year-old Rana rule and ushered in democracy. Nepal’s first steps towards democracy, however, were clumsy. It saw five different governments until 1959 when the country held its first general election. The Nepali Congress, which played a key role in overthrowing the Rana regime, was voted to power with a two-thirds majority. Congress’ BP Koirala was elected prime minister. But Nepal’s democracy dreams were short-lived. Just a year later, in 1960, King Mahendra staged a coup, banned political parties and set up a party-less Panchayat rule, a system the monarch said was “suitable to the Nepali soil”.

It took 30 years before Nepal’s political parties could restore democracy that was snatched away by king Mahendra. In 1990, Nepal proclaimed the dawn of democracy. Maendra’s son Birendra was on the throne. Nepal adopted a multiparty system with the constitutional monarchy and wrote a new constitution in 1990.

But Nepal’s fledgling democracy was assaulted once again. This time by Mahendra’s second son–Gyanendra–in 2005. King Birendra and his family were killed in the 2001 royal massacre.

Nepal needed yet another people’s movement in 2006 which abolished the centuries-old monarchy. A Constituent Assembly in 2015 drew up a new constitution, which was promulgated amid reservations from various sections of society. But five years after the new “people’s” constitution, democracy is once again under threat—this time from KP Sharma Oli, an elected prime minister.

As Nepalis mark Democracy Day, to commemorate the historic day of 1951, the country is yet again facing a democratic crisis.

“We have failed to set up a system, especially after 1990,” said Daman Nath Dhungana, a former House Speaker, who was on the forefront of the 1990 people’s movement, which is also dubbed “first people’s movement”. “It’s unfortunate that even a constitution that was delivered by the Constituent Assembly could not establish a political system.”

Many blame a lack of political culture among the parties for why the country has failed to strengthen democracy.

As in after 1951, the Nepali Congress was voted to power after the restoration of democracy in 1990. Democracy hugely suffered because of the growing intra-party feud in the Congress. Despite leading a majority government, then prime minister Girija Prasad Koirala dissolved the Parliament and called snap polls. Congress senior leader Krishna Prasad Bhattarai had to face a defeat largely due to the internal conflict in the party.

Disenchantment started to grow among the people, politicians were failing to deliver on their promises despite adopting “the world’s best constitution”.

A section of politicians that was vehemently opposed to the parliamentary system was priming itself for a drastic movement, which would later be known as “people's war”—an armed struggle against the state.

As the governments were formed and pulled down in Kathmandu, the Maoists waged the war in 1996, which continued until 2006. By the time it ended, at least 17,000 people had died and thousands were disappeared and maimed.

In 2001, Nepal grabbed international headlines when Birendra, who now in the hindsight many believe was a benevolent monarch, was killed along with his family. His younger brother Gyanendra succeeded.

People’s growing frustrations with politicians and the ongoing armed insurgency prompted Gyanedra, an ambitious individual with less political and more business acumen, into adventurism. When he staged a royal military coup in 2005, borrowing heavily from his father Mahendra’s over decades-old playbook, Nepal’s ever-squabbling parties made a united front. The Maoists who were looking for a safe landing agreed to lend their support.

The 2006 movement thus managed to extract democracy back from Gyanendra’s clutches. Out of sheer people’s power—widespread demonstrations were held across the country—at the call of political parties, the Parliament was resurrected.

The same year, a historic peace deal brought the Maoists to mainstream politics. The parties agreed to Maoists’ Constituent Assembly demand. But the parties that were together to fight the king once again could not maintain their unity for the larger interest of the public and the nation.

After the first Constituent Assembly elections in 2008, the game of musical chairs began again. The assembly was held hostage to politicians’ petty interests.

It took seven years for the assembly to deliver a constitution–once again dubbed “the best in the world”. The constitution guaranteed Nepal as a secular federal republic.

But five years later, the country is running the risk of losing all those gains and democracy is under threats.

“One of the main reasons why democracy in Nepal has suffered one blow after another is we failed to build institutions and systems,” said Ujjwal Prasai, a writer and political commentator who is also a columnist for the Post’s sister paper Kantipur. “We failed to strengthen and build the system and institutions friendly to the people.”

Prasai is currently an active member of the ongoing civilian protest, being organised under the banner Brihat Nagarik Andolan, to protest Prime Minister Oli’s December 20 decision to dissolve the House.

The Supreme Court is testing the constitutionality of Oli’s House dissolution, as his move has been challenged saying he took an unconstitutional step because the current constitution does not allow him to dissolve the House.

“We consider democracy in a formal context because we are holding elections regularly, we have free press, or there is human rights,” said Prasai. “But that is not enough. A democracy should be able to establish a link with the general public and society. We failed to inject democratic values and ethos in society.”

Nepal’s democratic evolution has also been described by many as one step forward two steps back. When Nepal heralded democracy for the first time in 1951, it was crushed by Mahendra and the country suffered for three decades.

When democracy was restored in 1990, politicians instead of nurturing it, made it feeble, thereby offering Gyanendra an opportunity on a platter to seize power.

Today democracy is under threat from the same actors who once championed for the cause.

Oli has argued that he was forced to take the drastic step because he was being driven into a corner by his opponents, especially Pushpa Kamal Dahal.

In what makes the greatest example of politics making strange bedfellows, Oli and Dahal decided to embrace each other in 2018 with a promise to launch “a great communist movement” that would transform Nepal. Dahal led the decade-long Maoist war, and Oli is among those politicians in Nepal who has always been critical of Dahal.

When Oli returned to power in 2018, it appeared that political stability was finally here to stay. But the factional feud in the Nepal Communist Party, especially between Oli and Dahal, resulted in the House dissolution, in what comes as a repeat episode of 1994 when GP Koirala had dissolved the House over infighting in his party.

This time, however, Oli took the step despite the constitution restricting him to do so, displaying his totalitarian streak, say analysts.

“Earlier political parties had conflicts with the monarchy. Now we are fighting against totalitarian tendencies,” said Dhungana. “Political parties have deviated from their primary duty of nation-building to power-grabbing. In earlier days, it was the palace which had an insatiable desire for power, these days political parties have inherited that tendency.”

During the 30 years of Panchayat rule, power was largely exercised by the palace, with some spoils shared among a handful of royal sycophants.

After the restoration of democracy, just as power was transferred to political parties, Nepal started to see the advent of rent-seeking tendencies. By the time the country became a federal republic, patron-client relationship emerged strongly, corruption became the new cottage industry where politicians and cadres started to go to any extent to exploit state resources.

Analysts say Nepali politicians totally forgot the age-old maxim of the government of the people, by the people and for the people.

“Democracy should serve the aspirations of millions of people and it’s definitely a tall order. That’s why democracy is chaotic also,” said Prasai, the writer. “But by building robust institutions and systems, governments can address people’s grievances and needs. That’s how democracy functions.”

While Nepali politicians are blamed for democratic backsliding, there is a section that strongly believes that until Nepal defeats foreign intervention, it cannot attain stability and cannot make strides in socio-economic sectors.

“The role of foreign hands in every big change in Nepal is no secret–in 1950 or 1990 or 2006,” said CP Mainali, a senior communist leader. “We failed to find the leadership at home that could fight foreign intervention. This is the sole reason we have failed to sustain the achievements in the last 70 years and have not been able to bring changes in people’s lives.”

According to Mainali, once Oli’s mentor, Nepal’s democratic movements have been laudable but a lack of failure to find a true leader has meant people’s aspirations of democracy and development continue to remain unfulfilled.

“We rather allowed more space to foreign hands to expand their clout instead of trying to become strong and independent in our decision-making,” said Mainali. “Our leaders totally failed to comprehend the fact their fight for democracy meant creating an environment where people are served. It’s instead the opposite. It looks like leaders fought for democracy for their benefit.”

Most of today’s leaders in Nepali politics have quite a record of their own under their belts, most of them have served jail terms fighting against the Panchayat regime and then the monarchy. There is no denying that they exhibited their unwavering commitment to democratic values, equitable society and rule of law–and above all, for the people. But the moment they get to power, they tend to forget all these, according to analysts.

“From 1959 to 2006, we were in a direct conflict with the monarchy that always stood against the fundamentals of democracy,” said Prof Krishna Khanal, who teaches political science at Tribhuvan University. “We may have failed to nurture democracy well, but a reversal is unlikely.”

According to Khanal, in Nepal, people's power has always prevailed.

“A democracy also means accountability. The only solution is our managers [politicians] must learn how to manage the system,” Khanal told the Post. “Democracy often faces challenges and we can say it is in peril in Nepal today. But it stands an equal chance of becoming vibrant and functional… just that leaders need to be made accountable.”

Some analysts find an uncanny repeat of a cycle, as people once again are on the streets to fight for democracy, just as the country is celebrating its Democracy Day to mark the dawn of democracy in Nepal.

Prasai, the writer, said that unless political actors are constantly kept in check and made accountable to those who elect them, democracy will continue to face challenges.

“Democracy should be realised by the people, and it’s the political actors who can make this happen,” Prasai told the Post. “In our context, it looks like democracy will face some challenges like it is facing today for some decades more.”

Anil Giri Anil Giri is a reporter covering diplomacy, international relations and national politics for The Kathmandu Post. Giri has been working as a journalist for a decade-and-a-half, contributing to numerous national and international media outlets.

Related News

Lawmakers’ ignorance of provisions in bills fuels policy corruption

Dahal prepares for Cabinet reshuffle

After 7 years of provinces, is Upendra Yadav’s grip on Madhesh politics loosening?

UML chief Oli criticises budget for not pursuing socialism

Cooperatives probe committee yet to begin its work

KP Oli personally objects to Madhav Nepal attending opposition parties’ meeting

Most read from politics.

Parties divided over naming Lamichhane in probe panel ToR

Congress vows to toughen stance on home minister investigation

Is Khanal prevailing over Nepal in Unified Socialist?

Editor's Picks

Taming of the shrews

Climate change hits mountain people on multiple fronts

Challenges of Nepali democracy

Nepalis losing millions in illicit pursuit of ‘American dream’

E-paper | june 06, 2024.

- Read ePaper Online

Share this via Facebook Share this via X Share this via WhatsApp Share this via Email Other ways to share Share this via LinkedIn Share this via Reddit Share this via Telegram Share this via Printer

Events of 2021

Nepalese women’s rights activists rallying in Nepal’s capital, Kathmandu, on February 12, 2021, to call for an end to violence and discrimination against women and the scrapping of a proposed law that would restrict travel for many women.

©2021 AP Photo/ Niranjan Shrestha

Inadequate and unequal access to health care in Nepal was exacerbated in 2021 by government failures to prepare or respond effectively when the Covid-19 pandemic surged, leading to many preventable deaths.

A pervasive culture of impunity continues to undermine fundamental human rights in the country. Ongoing human rights violations by the police and army, including cases of alleged extrajudicial killings and custodial deaths resulting from torture, are rarely investigated, and when they are , alleged perpetrators are almost never arrested.

Serious rights challenges remained unaddressed for months in 2021 during internal political infighting, the government was largely paralyzed by a struggle over the post of prime minister and repeated dissolutions of parliament. After the Supreme Court ordered in July that Sher Bahadur Deuba replace K.P. Oli as prime minister, the positions of health and education minister were left vacant for three months.

Both the Oli and Deuba governments continued to block justice for conflict-era violations. The mandates of the two transitional justice commissions were once again extended, although neither has made progress since being established in 2015 to provide truth to victims, establish the fate of the “disappeared,” and promote accountability and reconciliation.

In March the government signed a peace agreement with a banned Maoist splinter group, the Nepal Communist Party (NCP), after it agreed to renounce violence.

Health and Education

During a major wave of Covid-19 infections, which peaked in May, senior health officials described a system at the breaking point, with patients dying due to lack of bottled oxygen .

The government had failed to prepare for the scale of the outbreak. The situation was made worse by a shortage of vaccines, reflecting both global scarcity—wealthy governments blocked an intellectual property waiver that would have allowed for increased international production of vaccines and failed to require more widespread technology transfers—and delays in procurement by the government amid allegations of corruption . Those living in poverty, and members of marginalized social groups, were often least able to obtain treatment, and most vulnerable to economic hardship resulting from lockdowns.

After decades of progress in maternal and neonatal health, there was a substantial drop in the number of births at health facilities , which were overstretched by the pandemic. This was accompanied by increases in neonatal deaths, still births, and pre-term births.

Nepal had made progress in reducing child labor in recent years , but the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, together with school closures and inadequate government assistance, pushed children back into exploitative and dangerous child labor.

Transitional Justice

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons (CIEDP) were established in 2015, but despite receiving over 60,000 complaints of abuses committed during the 1996-2006 conflict, they have made no progress.

Successive governments have promised to bring the Enforced Disappearances Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act (2014) into conformity with international law as directed by the Supreme Court in 2015 but have failed to do so. The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has criticized the act for failing to comply with Nepal’s international legal obligations by giving the commission powers to recommend amnesties for gross violations of international human rights law and serious violations of international humanitarian law, avoiding or delaying criminal prosecutions, and failing to ensure independence and impartiality. The United Nations and international community therefore do not support these commissions.

Meanwhile, the authorities have prevented cases of conflict era violations from being heard in the regular courts on the grounds that they will be addressed by the transitional justice process, although no meaningful or credible transitional justice process exists. Victims’ groups have long called for the government to consult with victims before reappointing commissioners, but one of the first actions of Sher Bahadur Deuba upon becoming prime minister in July 2021 was to extend the commissioners’ terms for another year.

Survivors of sexual violence committed during the conflict suffered from a particular lack of support or interim relief.

Rule of Law

Impunity for human rights abuses extends to ongoing violations, undermining the principles of accountability and rule of law in post-conflict Nepal. In October, police shot dead four people in Rupandehi district while attempting to evict landless settlers from government land. UN rights experts have repeatedly raised cases of killings by the security forces but none have led to prosecutions, although the government acknowledged that one victim had been tortured in police custody.

A partial exception was the case of Rajkumar Chepang , who died in July 2020 after being tortured by soldiers guarding Chitwan National Park. In July 2021 a soldier was found guilty by Chitwan district court, in what is believed to be the first successful prosecution for torture in Nepal since it was criminalized in domestic law in 2018. However, he was sentenced to only nine months in jail.

In December 2020, the then government of K.P. Oli amended the law governing the Constitutional Council , which makes appointments to the National Human Rights Commission, and then appointed new human rights commissioners without proper consultation with opposition members. Because parliament was dissolved, the new commissioners were sworn in without parliamentary approval.

The same process was used to make other appointments, including to the Election Commission.

In October 2021 police detained a human rights defender, Ruby Khan , on false charges of “polygamy,” and initially defied a Supreme Court habeas corpus order to release her, after she led a protest demanding police investigate the alleged murder of two women.

Women’s and Girls’ Rights

Nepal has one of the highest rates of child marriage in Asia, with 33 percent of girls marrying before 18 years and 8 percent married by age 15. Among boys, 9 percent marry before the age of 18. This situation worsened during the pandemic , as children were pushed out of education and families faced increased poverty.

Nepal’s 2006 Citizenship Act, as well as the 2015 constitution, contain provisions that discriminate against women. A draft bill to amend the Citizenship Act, first presented to parliament in 2018, retains several discriminatory provisions. In September 2020, three UN human rights experts wrote to the government raising concerns that “the bill would continue to discriminate systematically against women, regarding their ability to transmit citizenship through marriage and to their children.” Due to flawed citizenship laws, an estimated 5 million people are forced to live without citizenship and are at risk of statelessness .

Reported cases of rape continued to sharply increase in 2021, but the police were often reluctant to register cases and investigations were frequently ineffective, resulting in widespread impunity for sexual violence.

Following Nepal’s Universal Period Review , the government began consultations to update the criminal code to better safeguard the recognized right to abortion.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

The bill to amend the Citizenship Act also contains a clause that would require transgender people to provide “proof” of their transition to access citizenship documents according to their gender identity—which violates international human rights law and a 2007 Nepal Supreme Court judgment mandating that gender identity be recognized based on “self-feeling.”

While Nepal was among the first countries in the world to protect social and political rights for LGBT people—including legal recognition of a third gender—cases of discrimination and police abuse continue .

Treatment of Minorities

Caste-based violence and discrimination against Dalits are rarely investigated or prosecuted, despite the adoption of the Caste-based Discrimination and Untouchability (Crime and Punishment) Act in 2011. Two emblematic cases of caste-based killings committed on May 23, 2020 , are yet to be prosecuted. One involved the death of a 12-year-old Dalit girl a day after she was forced to marry her alleged rapist, and the second, the killing of six men in Rukum West district after a young Dalit man arrived to marry his girlfriend from another caste.

Key International Actors

Nepal’s most important international relationships are with neighbors India and China, which compete for influence in Nepal. Both provided vaccine and other assistance to help Nepal cope with the pandemic, although India failed to keep up supplies during a surge in cases in early 2021 as it battled a devastating second wave of its own.

Nepal is a participant in the Chinese government’s “Belt and Road Initiative.” It continues to restrict free assembly and expression rights of its Tibetan community under pressure from Chinese authorities.

The Nepal government remains dependent for much of its budget on international development aid. Several of Nepal’s donors have funded programs for many years intended to support respect for human rights, police reform, access to justice, and respect for the rule of law, but have not pressed the government to advance transitional justice or end the impunity of the security forces.

Nepal is serving a second consecutive term on the UN Human Rights Council from 2021-2023.

Protecting Rights, Saving Lives

Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people in close to 100 countries worldwide, spotlighting abuses and bringing perpetrators to justice

Select a language

Accord ISSUE 26 March 2017

Downloads: 1 available

Available in

- Introduction: Two steps forward, one step back

- Nepal's war and political transition: a brief history

- Section 1: Peace process

- Stability or social justice?

- Role of the citizen in Nepal's transition: interview with Devendra Raj Panday

- Preparing for another transition?: interview with Daman Nath Dhungana

- Architecture of peace in Nepal

- International support for peace and transition in Nepal

- Transitional justice in Nepal

- Transformation of the Maoists

- Army and security forces after 2006

- People’s Liberation Army post-2006: integration, rehabilitation or retirement?

- Post-war Nepal - view from the PLA: interview with Suk Bahadur Roka

- PLA women's experiences of war and peace: interview with Lila Sharma

- Looking back at the CPA: an inventory of implementation

- Section 2: Political process

- Legislating inclusion: Post-war constitution making in Nepal

- Comparing the 2007 and 2015 constitutions

- Political parties, old and new

- Electoral systems and political representation in post-war Nepal

- Federal discourse

- Mapping federalism in Nepal

- Decline and fall of the monarchy

- Local governance and inclusive peace in Nepal

- Section 3: Inclusion

- Social movements and inclusive peace in Nepal

- Post-war armed groups in Nepal

- Secularism and statebuilding in Nepal

- Justice and human rights: interview with Mohna Ansari

- Gender first: rebranding inclusion in Nepal

- Inclusive state and Nepal’s peace process

- Inclusive development: interview with Shankar Sharma

- Backlash against inclusion

- Mass exodus: migration and peaceful change in post-war Nepal

- Section 4: Conclusion

- Uncertain aftermath: political impacts of the 2015 earthquakes in Nepal

- Conclusion More forward than back?: next steps for peace in Nepal

- Chronology of major political events in contemporary Nepal

Issue editors Deepak Thapa and Alexander Ramsbotham review the decade-long transition since the 2006 Comprehensive Peace Accord and consider whether Nepal is indeed post-conflict, or if the last ten years of fractious politics and episodic violence represent simply another phase of struggle. Regardless, they argue that the war and the peace process have brought significant change to Nepal’s social and political landscape, even if social justice remains a way off for many Nepalis outside the prevailing elite.

Peace by chance?

The manner in which the Maoist insurgency ended – with the removal of the monarchy – was far from inevitable. Indeed, chance was a recurrent motif in political developments in Nepal stretching from the early 1990s all the way to the 2006 CPA, facilitated by the capriciousness of the political parties and power struggles among political leaders. Nearly all the principal actors involved in the end of the war did little to address the insurgency in its early stages, and their paramount role in winding it down was not so much a deliberate strategy as following the old maxim that ‘the enemy of my enemy is my friend’.

Internal tussles in the Nepali Congress (NC) in particular accompanied significant developments in the Maoist conflict and how it ended. Factionalism began after the 1991 election, in which the NC won a majority. The three and a half years of the Girija Prasad Koirala-led government was the longest any had lasted in the post- 1990 period, but the latter stages were marred by bitter infighting. After losing a parliamentary vote in mid-1994, rather than step down, Koirala dissolved parliament in order to rein in his party’s dissidents. Significantly, this also spelt an end to parliamentary politics for the third largest force in the House of Representatives – the United People’s Front, the political wing of the semi-underground far-left party, a faction of which evolved into the insurgent Communist Party of Nepal–Maoist (CPN-M).

Koirala’s call for mid-term polls turned out to be a miscalculation. The NC was beaten by the CPN–Unified Marxist-Leninist (UML), but with only a plurality of parliamentary seats, the minority UML government lasted just nine months. Its removal set in motion a process of extremely unstable politics that saw a number of coalition governments, a situation that suited the Maoists and their budding insurgency very well.

The NC came back to power with a majority in 1999 and Koirala began his third term as prime minister in 2000. Factionalism was by now more or less institutionalised in the party and Sher Bahadur Deuba emerged as the leader of the anti-Koirala faction of the NC. Within a year of Koirala’s return to power, the Maoists clearly began favouring Deuba as someone with whom they could do business. Deuba had been prime minister when the insurgency began, but he had also been appointed to a committee to seek ways to bring a peaceful solution to the Maoist conflict.

The Deuba-Maoist detente played out in the 2001 ceasefire. However, when the Maoists quite suddenly resumed fighting, Deuba unleashed the full might of the state against the rebels, deploying the army for the first time. Now it was Koirala who moved closer to the Maoists, pressing for an end to the state of emergency in place at the time. The Koirala-Deuba feud ultimately resulted in Deuba dissolving parliament, just as Koirala had done nine years earlier. But, this time Deuba was expelled from the party, and he responded by splitting the NC itself.

In the meantime, the monarchy had become much more prominent in politics. King Gyanendra pounced on the opening provided by the disarray in the NC and the absence of parliament, but over the first years of his reign he managed to thoroughly alienate the political parties. The Maoists had hoped to exploit this gulf by striking a deal with Gyanendra, but the February 2005 royal takeover ensured an end to all overtures they had been making towards the king.

The king’s manoeuvres succeeded in bringing the parties and the Maoists to the realisation that their principal adversary was the palace. New Delhi also felt let down by the king studiously ignoring the long-held Indian position on what it viewed to be the twin pillars of political stability in Nepal: multiparty democracy and constitutional monarchy. The king’s snub came at a time when India had thrown itself firmly into the fight against the Maoists, such as by providing much-needed materiel to the Nepali Army. And although India had not realised the depth of popular anger against the palace, it had no choice but to go along with events that unfolded in the wake of the second People’s Movement and the complete sidelining of the monarchy.

Thus, political one-upmanship created the conditions for the Maoist movement to take off. But, its continuation over a decade also laid the foundations for the end of the conflict and the entry of the Maoists into mainstream politics.

Peace through inclusion

The government and political parties sought to undercut the Maoists’ progressive agenda with the introduction of a number of competing measures for reform. Many of these were what various social movements had long been agitating for. Steps such as the formation of the Committee for the Neglected, Oppressed and Dalit Class and the National Foundation for Development of Indigenous Nationalities were taken partly in response to pressure from social activists. But the insurgency brought home the depth of dissatisfaction with the status quo.

The Maoist movement pushed successive governments into adopting ever more inclusive provisions. Hence, while the Deuba government in 2001 had responded with a National Dalit Commission and the National Women’s Commission, among others, within a few years the idea of affirmative action policies had more or less become the accepted norm. The Maoists, too, were taken to task over the issue of inclusion, for despite their demands for gender equality, not a single woman was involved in their five- member negotiating team for the 2003 ceasefire.

By the time of the 2006 People’s Movement, it had been generally recognised that the state would have to become much more inclusive. The notion of state restructuring outlined in the CPA was clearly meant to accomplish that, but the momentum granted by the People’s Movement extended much further. When the First Madhes Movement erupted in early 2007, the public discourse was overwhelmingly in favour of Madhesis with a general excoriation of the state for the long subjugation they had experienced, and calls for addressing the sources of their dissatisfaction. Likewise, when the government later introduced reservations in elections and also in public sector jobs, the move met with hardly any opposition.

Such government policies have been instrumental in sustaining peace in the long term. The form of federalism may have been contested but despite misgivings expressed by more than a few influential people, there have been no considered attempts so far to roll back the achievements made towards a more inclusive state, whether through job reservations or electoral quotas – although the recent reduction of the number of seats to be elected through proportional reservations in the federal and provincial legislatures is considered by many to be exclusionary, as are steps such as the narrow definition provided for secularism, among others.

The integration of the Maoists into competitive politics may not have been achieved so easily had it not been for these measures. Their agenda was in part achieved even if their larger goal of a complete transformation of the socio- political structure could never be met, since the conflict was ended through a negotiated settlement with give and take from both sides. The core of the Maoist fighters who sustained the war against the state have been the most disappointed with the outcome. But, the training that had formed an intrinsic part of the party organisation, in which the military wing remained subservient to the political side, ensured compliance to all party decisions.

Peace and external support

While the push for greater inclusion came with the 1990 political change and was carried forward by the social movements and the Maoist insurgency, the government and its donor partners later became equally invested in supporting such an outcome. The government’s periodic plans in the 1990s had outlined ambitions to reach out to population groups that were increasingly being recognised as excluded from the development mainstream. But as the Maoist insurgency grew stronger and more widespread, there was a rising call from the donor community that it would also have to be countered by addressing the root causes of the conflict, which by definition meant opening up the state to greater levels of inclusion.

External actors have also had a more direct role in the unfolding of the peace process. Most consequential was the involvement of the United Nations, beginning with the Maoists’ initial response to the UN’s offer in 2002 to provide help in reaching a negotiated settlement to the conflict. For a group that had managed to isolate itself through its pronouncements (calling India ‘hegemonic’ and the United States ‘imperialist’) and its actions (killing Nepali staffers employed by the US embassy and targeting programmes funded by western countries, particularly by the US), an international guarantor was required for any agreement reached, not to mention for the Maoists’ personal safety.

But UN involvement would have been impossible without the acquiescence of India. The two countries routinely vilified by the Maoists, India and the US, had both labelled the CPN-M a terrorist organisation. India still clung to its ‘twin-pillar’ policy while the US had tried without success to effect a rapprochement between the palace and the mainstream parties. King Gyanendra’s obduracy slowly pushed India towards acceptance of UN involvement in bringing the conflict to a close. That the UN was even mentioned in the 12-Point Understanding signed in New Delhi in November 2005 is instructive of this change. Even earlier, India had gone along with setting up the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in Kathmandu. Established in May 2005, soon after the royal coup, its presence in the streets has been credited with the comparatively restrained response by the security forces during the April 2006 People’s Movement.

The UN Mission in Nepal (UNMIN) was deployed in January 2007 with the mandate to monitor arms, armies and the ceasefire, and to oversee the election of the Constituent Assembly. This limited mandate was primarily to allay Indian concerns. But contradictory interpretations of UNMIN’s role proved highly controversial over the four years of its tenure – on the one hand the failure to fully appreciate the specific tasks UNMIN had been given, and on the other the perception that the UN was somehow all-powerful. Thus, a meeting by the head of UNMIN with Madhesi leaders was criticised for overreach. At other times, UNMIN was accused of doing too little to rein in the Maoists. And the Maoists spoke out against UNMIN’s intrusive scrutiny of their activities. To its credit, UNMIN succeeded in seeing through the election to the 2008 Constituent Assembly, and even though the Maoist combatants were still in the cantonments by the time its mission ended, it preserved the peace between the two sides and laid the ground for the eventual disbandment of the Maoist army.

Over time there has been some concern about the direction the country has taken. Conflating the related but separate concepts of federalism and inclusion, influential sections in the government, the political parties and the media have pressured donors to ease off on the social inclusion agenda. Even India has not been able to make much headway in its call for a more inclusive polity. New Delhi’s position today is a far cry from the post- 2006 period, when it was viewed almost as an arbiter of Nepal’s fate, having stood with the political parties and the Maoists against the monarchy and enforcing an end to the second People’s Movement by leaning hard on the king. But, India continued with its political games, such as engineering the formation of a political party, the Tarai Madhes Loktantrik Party, to counter the Madhesi Janadhikar Forum Nepal, which was viewed as being too independent with its own power base. It coddled the NC and the UML, to act as a counterpoise to the Maoists and their radical agenda, only to realise later that the NC-UML combination is in general a conservative force, and that this conservatism would affect how they would deal with the grievances of Madhesis as well.

The fracas over the 2015 constitution, including the blockade at the border with India, and the tepid concession to Madhesi demands granted by the UML government with the first amendment to the constitution, has laid bare the limits of India’s power. There is no sign at the time of writing that the second amendment, introduced in November 2016 to further assuage Madhesis, is going to get anywhere. But although India has lost a lot of leverage recently, geopolitical reality dictates that New Delhi will always remain a major player in Nepal’s politics. And, the terms and conditions of that engagement that will be decided by political developments on the Madhes issue.

Whether one sees Nepal as post-conflict or in a new period of intense transition, it is clear that the war and the peace process have brought significant change. Communities on the periphery of Nepali politics and society – whether marginalised by culture, class, geography, gender or caste and ethnicity, or some configuration of these – have been at the centre of the struggle. But social justice is still a long way off for many Nepalis outside the prevailing elite. With the new constitution in place, which has been so symbolic as the culmination of Nepal’s transition ‘from war to peace’, advocates for inclusion may need to find new forums in which to negotiate change.

All authors and contributors

- Dr Alexander Ramsbotham

- Deepak Thapa

- Bishnu Sapkota

- Aditya Adhikari

- Mandira Sharma

- Jhalak Subedi

- Sudheer Sharma

- Chiranjibi Bhandari

- Suk Bahadur Roka ‘Sarad’

- Lila Sharma ‘Asmita’

- Krishna Hachhethu

- Dipendra Jha

- Sujeet Karn

- Kåre Vollan

- Krishna Khanal

- Gagan Thapa

- Bandita Sijapati

- Mukta S. Tamang

- Chiara Letizia

- Mohna Ansari

- Lynn Bennett

- Yam Bahadur Kisan

- Shankar Sharma

- Shradha Ghale

- Amrita Limbu

- Austin Lord

- Sneha Moktan

Accord Issue Issue 26

Advertisement

Modi’s Party May Need Partners to Form a Government

Prime Minister Narendra Modi is on track to secure a third term, but a dip in his party’s electoral support will have political consequences.

- Share full article

By Hari Kumar , Mujib Mashal and Mike Ives

- June 4, 2024

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ruling party will likely need help from junior partners to form a government under the rules of India’s parliamentary system, early election results indicated on Tuesday.

In a 2019 election that handed Mr. Modi a second consecutive term, his Bharatiya Janata Party won 303 of the 543 seats in Parliament. That was well over the 272 seats it needed to rule on its own.

This time, exit polls released over the weekend suggested that the B.J.P. would once again easily win more than 272 seats. But as of early Tuesday afternoon, official voting results indicated that it would win about 240 seats instead .

Winning that much support — 44 percent of the seats in Parliament’s lower house — is an impressive feat in India or any other country. And the new math should not prevent Mr. Modi from securing a third consecutive term as prime minister.

But the dip in the B.J.P.’s electoral support, far short of Mr. Modi’s goal and his last electoral performance, will likely have political ramifications.

At a minimum, the B.J.P. will have to depend more on the junior members of its existing multiparty alliance. Two of the most prominent parties do not share Mr. Modi’s Hindu-first agenda.

And if the governing alliance does not win a majority, the B.J.P. will be able to form a government only by adding new partners.

It may not come to that. As of Tuesday afternoon the alliance was on track to scrape by with a narrow parliamentary majority — far short of its target of 400 seats, but enough to stay in power with its existing members.

Hari Kumar covers India, based out of New Delhi. He has been a journalist for more than two decades. More about Hari Kumar

Mujib Mashal is the South Asia bureau chief for The Times, helping to lead coverage of India and the diverse region around it, including Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bhutan. More about Mujib Mashal

Mike Ives is a reporter for The Times based in Seoul, covering breaking news around the world. More about Mike Ives

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Nepal's domestic politics have been undergoing a turbulent and significant shift. On December 20, 2020, at the recommendation of Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli, President Bidya Devi Bhandari dissolved the House of Representatives, calling for snap elections in April and May 2021. Oli's move was a result of a serious internal rift within the ruling Nepal Communist Party (NCP) that threatened ...

The politics of Nepal functions within the framework of a parliamentary republic with a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the Prime Minister and their cabinet, while legislative power is vested in the Parliament.. The Governing Nepali Congress and Communist Party of Nepal (UML) have been the main rivals of each other since the early 1990s, with each party defeating the other ...

With the prime minister's unilateral move to dissolve Parliament last December, Nepal was thrown into political chaos - with its democracy hanging in the balance. By Peter Gill February 06, 2021

Religious freedom is constitutionally protected, and tolerance is broadly practiced, though some religious minorities occasionally report harassment. Muslims in Nepal are particularly impoverished, occupying a marginalized space. Proselytizing is prohibited under a 2017 law, and some Christians have been prosecuted under this law.

In 2006, the government of Nepal and Maoist insurgents brokered the end of a ten-year civil war that had killed thousands and displaced hundreds of thousands. The ensuing Comprehensive Peace Agreement laid out a path to peace and ushered in a coalition government. Nepal's people were eager to see the fighting end. Their political leaders ...

Nepal's democracy challenges. Analysts say the major impediment to democratic process in the country is a lack of political culture among leaders and their failure to put people first. Post Illustration: Deepak Gautam. Seventy years ago, on this day (Falgun 7) Nepal ended 104-year-old Rana rule and ushered in democracy.

Religious freedom is constitutionally protected and tolerance is broadly practiced, though some religious minorities occasionally report harassment. Muslims in Nepal are particularly impoverished, occupying a marginalized space. Proselytizing is prohibited under a 2017 law, and some Christians have been prosecuted under this law.

The party system's factionalisation and the monarchy's. The party system's factionalisation: Nepal has a polarised and highly partisan political party system. The fragmentation of the party system has worsened Nepal's political instability. In Nepal, he has led political parties for more than 70 years.

A man sits with a huge Nepali flag near a polling station in Kathmandu, Nepal, Nov. 19, 2013. In Nepal, May 28 marks Republic Day, commemorating the date in 2008 when an elected Constituent ...

Kathmandu: Vajra Books. 2013, 280 pp., ISBN 978-9937-623-07-0, US$ 15. Reviewed by Chiara Latizia. This book deals with the sweeping changes that Nepal experienced between 1950 and 2012. Gérard Toffin, drawing on the research he has been conducting in Nepal since the 1970s, reflects on the transformations he witnessed and wrote about over the ...

The 50-page report, "Breaking Barriers to Justice: Nepal's Long Struggle for Accountability, Truth and Reparations," describes the decades-long struggle for justice by survivors and victims.

Essentially, Nepal's people want jobs, health facilities, safe drinking water, education, and road networks, regardless of what party wins in the elections. In the last three decades, the ...

Despite the new Constitution adopted in 2015, political instability continues in Nepal. Political parties are engaged in intense negotiations over the formation of a new government in the post-March 7 verdicts. After scrapping the NCP, no party has the majority in the parliament. However, the Oli-led CPN-UML might claim government formation ...

1. Background. The socio-economic and political injustice in Nepal has given rise to the unequal social relationships along the lines of class, caste, gender, ethnicity, religious and regional disparities and ever widening the gap between the rich and poor. The striking features of under-development in Nepal - rampant poverty, unequal ...

Much of Nepal's economy depends upon remittances from Nepali workers abroad and tourism, and both came to a screeching halt with the pandemic. Tourism suffered an astounding 80% drop, causing many to lose their jobs and homes. Nepal went into a severe lockdown last year from March through July in response to the pandemic.

Political instability has been a persistent issue in Nepal, hindering progress in various sectors and contributing to economic and social problems. Addressing the issue will require a commitment ...

Women's and Girls' Rights. Nepal has one of the highest rates of child marriage in Asia, with 33 percent of girls marrying before 18 years and 8 percent married by age 15. Among boys, 9 ...

Issue editors Deepak Thapa and Alexander Ramsbotham review the decade-long transition since the 2006 Comprehensive Peace Accord and consider whether Nepal is indeed post-conflict, or if the last ten years of fractious politics and episodic violence represent simply another phase of struggle. Regardless, they argue that the war and the peace process have brought significant change to Nepal's ...

The current political situation in Nepal can be attributed to the prevailing social and economic conditions that affect the day-to-day life of Nepalese people, especially the two historically ...

2 decisions.7 A vigorous and effective local democracy is the underlying basis for a healthy and strong national level democracy.8Local democracy provides greater opportunities for political participation and also serves an instrument of social inclusion,9 and particularly attends to the emerging context in Nepal within which the people are seeking their extensive role in state as

UNDER JAYASTHITIMALLA (A.D. 1382-1395) Before the time of Jayasthitimalla the social and religious structure of Nepal was largely Buddhistic and partly Brahmanistic. Main basis this structure was the process of social and religious tension and cohesion. forces had emerged as a powerful proselytising agent in Indian society.

The Return of the Left Alliance in Nepal Changes Regional Power Dynamics. With the pro-India Nepali Congress out of the ruling coalition, and the China-friendly CPN-UML back in, Nepal's diplomacy ...

The economy of Nepal has been undergoing a gradual change along with the political system, changing from a fully agrarian system to a semi-modern system. However, it shows that something is wrong as Nepal is still one of the poorest countries in the world. Economic development requires economic transformation to constantly generate new dynamic ...

Prime Minister Narendra Modi is on track to secure a third term, but a dip in his party's electoral support will have political consequences. By Hari Kumar, Mujib Mashal and Mike Ives Prime ...