- Sign up for updates

mpa-banner-bt

Driving Economic Growth

Film and television production creates and supports jobs for millions of Americans in front of and behind the camera, while generating a valuable and sought-after global export.

An Engine for the U.S. Economy

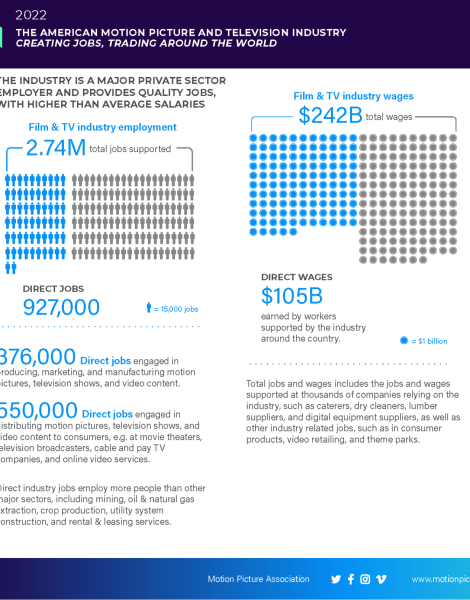

The film and television industry supports a dynamic U.S. creative economy, employing people in every state, and across a diversity of skills and trades. In all, 2.74 million people—from special effects technicians to makeup artists to writers to set builders to ticket takers and more—work in jobs supported by the industry, which pays over $242 billion in wages annually.

When a movie or television show shoots on location, it brings jobs, revenue, and related infrastructure development, providing an immediate boost to the local economy. Our industry pays out $33 billion per year to more than 240,000 businesses in cities and small towns across the country—and the industry itself is comprised of more than 122,000 businesses, 92 percent of which employ fewer than 10 people. As much as $1.3 million can be injected into local economies per day when a film shoots on location. In some cases, popular films and television shows can also boost tourism.

For example, Marvel’s Black Panther involved more than 3,100 local workers in Georgia who took home more than $26.5 million in wages, while 20th Century Fox’s popular television series This Is Us contributed more than $61.5 million to the California economy. And in New York, Oscar-nominated films The Post and The Greatest Showman contributed more than $108 million to the state’s local economy.

A strong national economy depends on a strong creative economy—and it all starts with a story.

The film and television industry supports 2.74 million jobs, pays out $242 billion in total wages, and comprises over 122,000 businesses.

FILM & TELEVISION ECONOMIC CONTRIBUTION BY STATE

The production and distribution of movies and TV shows is one of the nation’s most valuable cultural and economic resources. Each year, film and TV production activity takes places in all 50 states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. To find out more about the industry’s impact on specific states, click on the states below. Additional information and updates can be found at the state's film commission website located here. Note: Industry impact (jobs/wages) numbers reflect 2020 data. Numbers are updated annually following the release of the prior year’s Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data.

Test modal content

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit. Eos, earum odio. Illum distinctio error fugiat quisquam ullam sequi, vel itaque dolor obcaecati consequatur, totam animi cupiditate expedita minus illo laborum?

The American Motion Picture and Television Industry: Creating Jobs, Trading Around the World

The American film and television industry supports 2.74 million jobs, pays out $242 billion in total wages, and comprises more than 122,000 businesses—according to an analysis of the most recent economic figures released by the Motion Picture Association.

For a more detailed analysis of the industry’s economic impact, download the full report:

A Global Creative Economy

American storytelling is enjoyed by audiences around the world, accounting for $14.4 billion annually in exports and registering a positive trade balance with nearly every country in the world.

To maintain our competitiveness and reach global audiences, we need open access to markets around the world via forward-looking trade policies that reduce trade barriers, address intellectual property theft, and improve international copyright laws.

More than 70 percent of global box office sales come from international markets.

More of What We Do

Production incentives.

America’s film and television industry creates and embraces new advances in technology—both in how we tell stories and how we engage audiences. Innovations in filmmaking transport audiences to new worlds and deliver content where, when, and on any device they want.

Sign Up For Updates

To stay up to date with the Motion Picture Association, please sign up for our newsletter.

Your browser is not supported

Sorry but it looks as if your browser is out of date. To get the best experience using our site we recommend that you upgrade or switch browsers.

Find a solution

- Skip to main content

- Skip to navigation

- Back to parent navigation item

- Digital Editions

- Screen Network

- Stars Of Tomorrow

- The Big Screen Awards

- FYC screenings

- World of Locations

- UK in focus

- Job vacancies

- Distribution

- Staff moves

- Territories

- UK & Ireland

- North America

- Asia Pacific

- Middle East & Africa

- Future Leaders

- My Screen Life

- Karlovy Vary

- San Sebastian

- Sheffield Doc/Fest

- Middle East

- Box Office Reports

- International

- Golden Globes

- European Film Awards

- Stars of Tomorrow

- Cannes jury grid

Subscribe to Screen International

- Monthly print editions

- Awards season weeklies

- Stars of Tomorrow and exclusive supplements

- Over 16 years of archived content

- More from navigation items

Nine talking points for the global film industry in 2022

By Ben Dalton , Jeremy Kay , Melanie Goodfellow and Mona Tabbara 2022-01-11T10:43:00+00:00

- No comments

Source: Moon Films / EFM/Juliane Eirich / Getty Images/Wael Abutalib/EyeEm

Top right: EFM, bottom left: Jeddah

The theatrical window could get even shorter

Cinema distribution and theatrical exhibition as we know them are evolving to a place where they are becoming unrecognisable compared to where we were just over two years ago. The question is will the exclusive theatrical window get shorter in 2022 if Covid continues to discourage cinema-going?

Distribution models vary by studio but generally the pandemic-fuelled individual deals cut by distributors and exhibitors around the world mean North America’s pre-Covid 75- to 90-day exclusive theatrical window – 90 days in the UK – has shrunk to 30-45 days. It’s even shorter at Universal, which has the option to move a film from North American cinemas to PVoD after 17 days of exclusive theatrical play, rising to 31 days for those that score a $50m-plus opening weekend. And starting this year all Universal and Focus films will debut on Peacock as soon as 45 days after their theatrical and PVoD release.

The international rollout of HBO Max means Warner Bros titles now have just a 31-day window in the UK (45 days in the US), while Paramount releases in the US can play in cinemas for a maximum of 45 days before heading to Paramount+. Depending on the title, Disney is experimenting with exclusive theatrical and day-and-date models whereby a film opens simultaneously in cinemas and on Disney+. However, the studio will be wary of switching models without careful consultation with talent after Scarlett Johansson sued when Black Widow opened day-and-date, which the star said was contrary to what she believed was an exclusive theatrical agreement and cost her a pile of money in lost potential backend participation. (The parties settled out of court.)

Sony has been the most reluctant US major to abandon exclusive theatrical releases – not surprising given it doesn’t have a global streaming service. In the case of Spider-Man: No Way Home that reluctance has paid huge dividends.

There will always be exceptions to the rule of dwindling theatrical exclusivity. Christopher Nolan and his Oppenheimer project at Universal is a case in point and James Cameron will surely have insisted Disney keep his upcoming Avatar sequels exclusively in cinemas far longer than the new norm. On the whole, however, studios are now expected to play their part in growing subscribers on in-house platforms and their media corporation parent companies will be chomping at the bit to bring films to audiences at home as quickly as possible.

Exhibitors need to adapt. Fast.

Cinema owners have endured a torrid two years and will inevitably contract. Sad to say, but a footprint of 44,000 cinemas in the US today seems needlessly high and wasteful. In these days of the streaming wars, no in-house audits by exhibitors or a perusal of the books by potential suitors will look kindly on keeping the lights on in struggling markets, or at times of the day when there is minimal engagement. The world is changing fast and more exhibitors will need to cut VoD revenue-share deals with distributors, implement dynamic ticket pricing, programme alternative content like sports, theatre and live music, and make more noise with fewer sites.

Indie films’ disappearing act at the box office

The pandemic has shifted the balance of cinema releases even further in the direction of blockbusters and away from local and independent titles. This has been replicated in key international markets including the big English-language ones of the UK-Ireland and Australia, but also in Italy where the big local comedies failed to ignite in 2021, and even in France where the older demographic has had its usual dedication to independent cinema shaken by Covid concerns. Now indie distributors are looking to find space for titles among a release schedule that is still holding back blockbusters first planned for 2020. And while exhibitors will be glad of the money brought by No Time To Die , Spider-Man: No Way Home and co, they – especially independent venues – will know a variety of programming is important to their long-term survival.

The big exception is China, where US releases are severely limited. The China box office has made a stellar start to 2022, continuing its strong form from last year when it was the largest individual territory with $7.4bn. Three of the top five films in last weekend’s global top five were local Chinese titles; local content has also flourished in Thailand in recent weeks.

Festivals cannot sustain the Covid uncertainty for a third year…

The physical components of January festivals Rotterdam and Sundance and the European Film Market in February have been forced online by the pandemic, meaning it will be three years since their last get-togethers should they return as in-person events next year. By March, international film events will be reaching a third pandemic-afflicted edition; and while vaccines have reduced the virus’ damage, events are still walking a tightrope between holding in-person events and being overwhelmed by case numbers.

This uncertainty is not sustainable in the long term, and while numerous events took place last year with varying degrees of ‘Covid safety’, such measures are expensive – prohibitively so for some. With the less-deadly Omicron now widespread in many countries, film festivals may follow other industries in reducing testing and returning towards a scenario where illness is the determining factor in attendance, not swab results. With Cannes now under 130 days away and counting (gulp), for now, the industry is crossing its fingers – and holding its breath.

…and neither can buyers and sellers

International sales companies and distributors are at sea over their immediate next moves, with many now likely scrambling to move their Berlin flight to Cannes.or wondering whether to attend a festival-only event. There’s a nervousness in the market as we head into the third year of the pandemic, with sellers wondering where on earth is best to hold the sales or theatrical launch of a title and fielding growing concern as to whether their long-time distribution clients are in even in a position to buy new titles. Many are still working their way through the release of a backlog. “Normally at this time of the year, we’d be setting out our strategy up until Cannes and beyond but this year, I can’t figure out what is going to happen over the coming three months,” confided one key European sales agent.

US streamers may meet greater regulation in Europe

2021 saw another big push by global streamers into Europe. Their investment in local content is a boon but there is growing unrest in the independent community over the all-rights demands they impose and how they are pricing local producers out of their own markets. Now regulation in this highly regulated region looms. France’s long-awaited bold transposition in December of the European Union’s updated Audiovisual Media Services Services Directive, for example, includes measures to protect independent producers from all-rights deals and sets limits on how long a platform can hold rights. Will other territories follow where France dares to tread?

Covid measures take a toll on mental health – and budgets

The impact of filming under Covid conditions is hitting both budgets and the mental health of the film industry hard as productions attempt to balance duty of care towards employees with ever-evolving and wildly different national guidelines. Fatigue is setting in over regular testing, quarantine requirements and the strain when productions are interrupted by Covid outbreaks. On-set camaraderie, the stuff that gets crew through the long hours and often challenging conditions, has taken a hit, while departmental bubbles have made after-hours bonding sessions almost impossible. Wellbeing officers on set may now be commonplace, but this can add further stress owing to a squeeze on production costs. Removing Covid measures entirely does not appear to be the answer either. But the time may be coming to explore a middle ground, in which protective measures remain in place, but vaccination statuses are taken into greater consideration with regards to on-set regulations and testing regimes, before the burden becomes too great.

NFTs as a possible funding and distribution mechanism

Hollywood is continuing to scrutinise and experiment with the NFT, or non‑fungible token. It’s like a digital version of a rare coin or some other coveted item made from a unique chunk of digital code stored on the blockchain and verified for authenticity. Investors ascribe value to NFTs which are traded on specific marketplaces like Open Sea. At first it was deemed a fad, but the idea of NFTs has not gone away and after gaining popularity in art and music now the film industry is dipping its toes in the water. Warner Bros has partnered with a company to create unique digital avatars of ordinary people trapped in the Matrix, while Quentin Tarantino has locked horns with Miramax in a copyright dispute over his plan to auction off seven digitally scanned scenes based on his original handwritten Pulp Fiction screenplay (with misspellings and original character names intact) as secret NFTs. The content will only be known to the buyer. There has been early blue-sky talk of NFTs as a kind of ultra-boutique distribution model for small films whereby the buyer gets a digital collectible of the work with some unique accompanying element, while the producer or financier pockets the proceeds of the auction. NFTs remain a new frontier for Hollywood, but the industry is circling.

Saudi’s cinema drive may signal a new era

Key Middle East and North African industry players flocked to the first edition of Saudi Arabia’s new Red Sea International Film Festival in December. Most view Saudi Arabia’s push into cinema, after its 35-year ban was lifted at the end of 2017, as a game-changer for the MENA film industry and were eager to connect with the country’s burgeoning filmmaking scene and its market of 34.8 million people, two thirds of whom are under the age of 35. Saudi’s cinema push is already having reverberations in the region, particularly for Egypt, the mainstream comedies of which are proving a hit with the local audiences. A raft of new partnerships between emerging Saudi film companies and established MENA players were announced while the country’s ambitions to become a major international shooting location were exemplified by the arrival of action pictures Desert Warrior and Kandahar .

Five talking points for the UK industry in 2022

No comments yet, only registered users or subscribers can comment on this article., more from features.

Is the indie tax credit finally making the UK a valuable co-production partner?

2024-05-31T13:57:00Z By Geoffrey Macnab

European producers are taking notice.

Word of Mouth - UK casting director Isabella Odoffin: “My mum has the most wide-ranging taste”

2024-05-30T09:55:00Z By Ben Dalton

Odoffin worked on Un Certain Regard titles ’On Becoming A Guinea Fowl’ and ’September Says’

Screen critics’ stand-out titles from Cannes 2024

2024-05-29T11:35:00Z By Fionnuala Halligan

Our critics round up the films that may have flown under the radar but generated a lot of praise.

- Advertise with Screen

- A - Z of Subjects

- Connect with us on Facebook

- Connect with us on Twitter

- Connect with us on Linked in

- Connect with us on YouTube

- Connect with us on Instagram>

Screen International is the essential resource for the international film industry. Subscribe now for monthly editions, awards season weeklies, access to the Screen International archive and supplements including Stars of Tomorrow and World of Locations.

- Screen Awards

- Media Production & Technology Show

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy & Cookie Policy

- Copyright © 2023 Media Business Insight Limited

- Subscription FAQs

Site powered by Webvision Cloud

- Media ›

- TV, Video & Film

Film production worldwide - statistics & facts

The three asian titans, everybody (still) comes to hollywood, key insights.

Detailed statistics

Key data on the movie production & distribution industry worldwide 2022

Forecast filmed entertainment revenue in selected countries worldwide 2026

Forecast filmed entertainment revenue growth in selected markets worldwide 2021-2026

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Cinema & Film

Filmed entertainment revenue in selected countries worldwide 2021

Global box office revenue 2004-2021, by region

Further recommended statistics

- Premium Statistic Global box office revenue 2004-2021, by region

- Premium Statistic Leading box office markets worldwide 2021, by revenue

- Premium Statistic Leading film markets worldwide 2022, by number of tickets sold

- Premium Statistic Key data on the movie production & distribution industry worldwide 2022

- Premium Statistic Forecast filmed entertainment revenue growth in selected markets worldwide 2021-2026

- Premium Statistic Forecast filmed entertainment revenue in selected countries worldwide 2026

- Premium Statistic Movie market revenue worldwide 2002-2020

- Premium Statistic Filmed entertainment revenue in selected countries worldwide 2021

Global box office revenue from 2004 to 2021, by region (in billion U.S. dollars)

Leading box office markets worldwide 2021, by revenue

Leading box office markets worldwide in 2021, by revenue (in billion U.S. dollars)

Leading film markets worldwide 2022, by number of tickets sold

Leading film markets worldwide in 2022, by number of tickets sold (in millions)

Key data on the movie production & distribution industry worldwide 2022

Key data on the movie production and distribution industry worldwide in 2022

Estimated filmed entertainment revenue growth in selected countries worldwide between 2021 and 2026

Estimated filmed entertainment revenue in selected countries worldwide in 2026 (in million U.S. dollars)

Movie market revenue worldwide 2002-2020

Theatrical market revenue worldwide from 2002 to 2020 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Filmed entertainment revenue in selected countries worldwide in 2021 (in million U.S. dollars)

Asia & Australia

- Premium Statistic Number of feature films produced in China 2013-2023

- Premium Statistic Box office revenue in China 2013-2023

- Premium Statistic Number of Japanese movies shown at theaters in Japan 2014-2023

- Premium Statistic Total box office gross in Japan 2014-2023

- Premium Statistic Overseas releases of Indian films 2017-2023

- Premium Statistic Box office revenue in India 2023, by language

- Premium Statistic Movie export number in South Korea 2013-2023

- Premium Statistic Box office revenue in South Korea 2004-2023

- Premium Statistic Number of movies released in Australia 2014-2023, by origin of production

- Premium Statistic Box office revenue in Australia 2014-2023

Number of feature films produced in China 2013-2023

Number of feature films produced in China from 2013 to 2023

Box office revenue in China 2013-2023

Box office revenue in China from 2013 to 2023 (in billion yuan)

Number of Japanese movies shown at theaters in Japan 2014-2023

Number of Japanese movies released to cinemas in Japan from 2014 to 2023

Total box office gross in Japan 2014-2023

Total box office gross in Japan from 2014 to 2023 (in billion Japanese yen)

Overseas releases of Indian films 2017-2023

Overseas releases of Indian films from 2017 to 2023

Box office revenue in India 2023, by language

Box office revenue across India from 2017 to 2023, by language (in billion Indian rupees)

Movie export number in South Korea 2013-2023

Number of exported South Korean films from 2013 to 2023

Box office revenue in South Korea 2004-2023

Box office revenue in South Korea from 2004 to 2023 (in trillion South Korean won)

Number of movies released in Australia 2014-2023, by origin of production

Number of movies released in Australia from 2014 to 2023, by origin of production

Box office revenue in Australia 2014-2023

Box office revenue in Australia from 2014 to 2023 (in million Australian dollars)

United States & Canada

- Basic Statistic Movie releases in the U.S. & Canada 2000-2023

- Premium Statistic Revenue of the film & video production and distribution sector in the U.S. 2005-2022

- Premium Statistic Feature film production shoot days in L.A. 2017-2023

- Basic Statistic Employment in the motion picture & sound recording industries in the U.S. 2001-2024

- Premium Statistic Number of domestic movies produced in Canada 2004-2022

- Premium Statistic Box office revenue in Canada 2007-2022, by origin of production

Movie releases in the U.S. & Canada 2000-2023

Number of movies released in the United States and Canada from 2000 to 2023

Revenue of the film & video production and distribution sector in the U.S. 2005-2022

Estimated revenue of the motion picture and video production and distribution industry in the United States from 2005 to 2022 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Feature film production shoot days in L.A. 2017-2023

Number of shoot days spent on feature film production in Greater Los Angeles from 1st quarter 2017 to 4th quarter 2023

Employment in the motion picture & sound recording industries in the U.S. 2001-2024

Total employment in the motion picture and sound recording industries in the United States from 2001 to 2024 (in 1,000s)

Number of domestic movies produced in Canada 2004-2022

Number of Canadian theatrical movies produced in Canada from fiscal year 2004/05 to 2021/22

Box office revenue in Canada 2007-2022, by origin of production

Box office revenue in Canada from 2007 to 2022, by origin of production (in million Canadian dollars)

- Premium Statistic Number of movies produced in France 2011-2022

- Basic Statistic Revenues of cinema box office in France 2000-2022

- Premium Statistic Cinema films produced in Germany 1999-2020

- Premium Statistic Cinema revenue in Germany H1 2004-H1 2023

- Premium Statistic Number of feature films produced in the United Kingdom 1994-2021

- Basic Statistic Box office revenue in the UK 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic Global theatrical market share of British films 2002-2023, by production type

- Premium Statistic Number of feature movies produced in Spain 2000-2022

- Premium Statistic Box office revenue of domestic feature films in Spain 2000-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of Italian movies released in Italy 2017-2023

- Basic Statistic Box office revenue in Italy 2011-2023

Number of movies produced in France 2011-2022

Number of feature films produced in France from 2011 to 2022

Revenues of cinema box office in France 2000-2022

Revenues of movie theaters in France from 2000 to 2022 (in million euros)

Cinema films produced in Germany 1999-2020

Number of cinema films produced in Germany from 1999 to 2020

Cinema revenue in Germany H1 2004-H1 2023

Cinema revenue in Germany from H1 2004 to H1 2023 (in million euros)

Number of feature films produced in the United Kingdom 1994-2021

Number of feature films produced in the United Kingdom from 1994 to 2021

Box office revenue in the UK 2010-2022

Box office revenue in the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2022 (in million GBP)

Global theatrical market share of British films 2002-2023, by production type

Share of worldwide box office revenue generated by UK films from 2002 to 2023, by production type

Number of feature movies produced in Spain 2000-2022

Number of domestic feature films produced in Spain from 2000 to 2022

Box office revenue of domestic feature films in Spain 2000-2022

Box office revenue of domestic feature films in Spain from 2000 to 2022 (in million euros)

Number of Italian movies released in Italy 2017-2023

Number of domestic films released in Italy from 2017 to 2023

Box office revenue in Italy 2011-2023

Total box office revenue in Italy from 2011 to 2023 (in million euros)

Latin America

- Premium Statistic Box office revenue in selected countries in Latin America 2022

- Premium Statistic Mexico: domestic movies released 2010-2022

- Basic Statistic Mexico: national movie releases outside of Mexico 2009-2022

- Basic Statistic Box office revenue in Mexico 2010-2023

- Premium Statistic New domestic movies released in Brazil 2009-2022

- Premium Statistic Box office revenue in Brazil 2006-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of domestic movies released in Colombia 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic Box office revenue in Colombia 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of domestic movies released in Argentina 2014-2022

- Premium Statistic Box office revenue in Argentina 2014-2022

Box office revenue in selected countries in Latin America 2022

Box office revenue in selected countries in Latin America in 2022 (in million U.S. dollars)

Mexico: domestic movies released 2010-2022

Number of domestic movies released in Mexico from 2010 to 2022

Mexico: national movie releases outside of Mexico 2009-2022

Number of Mexican movie releases outside of Mexico from 2009 to 2022

Box office revenue in Mexico 2010-2023

Box office revenue in Mexico from 2010 to 2023 (in billion Mexican pesos)

New domestic movies released in Brazil 2009-2022

Number of new domestic movies released in Brazil from 2009 to 2022

Box office revenue in Brazil 2006-2022

Box office revenue in Brazil from 2006 to 2022 (in million Brazilian reals)

Number of domestic movies released in Colombia 2010-2022

Number of domestic movies released in Colombia from 2010 to 2022

Box office revenue in Colombia 2010-2022

Box office revenue in Colombia from 2010 to 2022 (in billion Colombian pesos)

Number of domestic movies released in Argentina 2014-2022

Number of domestic movies released in Argentina from 2014 to 2022

Box office revenue in Argentina 2014-2022

Box office revenue in Argentina from 2014 to 2022 (in billion Argentine pesos)

- Premium Statistic Nollywood, Bollywood, and Hollywood titles in anglophone West-Africa 2021

- Premium Statistic Nollywood, Bollywood, and Hollywood revenue in West-Africa 2022

- Premium Statistic Films produced by the Nigerian film industry 2017-2021

- Premium Statistic GDP by motion pictures, sound and music production in Nigeria 2019-2021

Nollywood, Bollywood, and Hollywood titles in anglophone West-Africa 2021

Number of titles released by the main film industries in Ghana, Liberia, and Nigeria in 2021

Nollywood, Bollywood, and Hollywood revenue in West-Africa 2022

Distribution of revenue generated by the main film industries in Ghana and Nigeria as of 2022

Films produced by the Nigerian film industry 2017-2021

Number of movies produced and censored by Nollywood from 2017 to the 2nd quarter of 2021

GDP by motion pictures, sound and music production in Nigeria 2019-2021

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) generated by the industry of motion pictures, sound recording and music production in Nigeria from 2019 to 2021 (in million Naira)

Further reports

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

The Indian film industry in a changing international market

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 03 May 2019

- Volume 44 , pages 97–116, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Sayantan Ghosh Dastidar 1 &

- Caroline Elliott ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1218-4164 2

47k Accesses

20 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

India has a longstanding reputation for its acclaimed film industry and continues to be by far the world’s largest producer of films. Nevertheless, domestic demand for films appears to be waning as in a number of developed countries with mature film industries. Hence, the econometric analysis in this paper is particularly timely as with demand for films in Indian cinemas falling it is important to identify those factors that make films appealing for Indian audiences. An original dataset is utilised that includes data on all Bollywood films released in India between 2011 and 2015. Account is taken of the potential endogeneity between variables through the use of the generalised method of moments approach. Results are used to demonstrate how the Indian film market can continue to have a significant positive impact on the Indian economy. The discussion highlights appropriate film production company strategies and government policy responses that should be considered to ensure the continued success of the Indian film industry both domestically and in an increasingly competitive international market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Public Film Policy and the Rise of Economic Principles: The Case of Switzerland

Americanisation in Reverse? Hollywood Films, International Influences, and US Audiences, 1946–1965

Introduction

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

India has a longstanding reputation for its acclaimed film industry, with the term Bollywood synonymous with vividly coloured films featuring complex dance routines, singing and spectacular large cast scenes. India continues to be by far the world’s largest producer of films, producing 1724 films in 2013 compared to 738 films produced in the USA, and 638 films produced in China. Footnote 1 Nevertheless, domestic demand for films appears to be waning as in a number of developed countries including the USA and UK. For comparison purposes, film industry data for China, the USA and the UK as well as India are provided in Table 1 .

It is immediately clear that while India produces by far the greatest number of films, with the number of films produced continuing to rise, the number of consumers paying to see films at cinemas in India has declined dramatically in recent years, despite significant growth in GDP since 2000 and international investment in the Indian film industry, Fetscherin ( 2010 ). However, falling popularity of going to the cinema is not exclusive to India, with falls in cinema ticket sales also seen in the USA and UK. Each of these film markets can be considered mature markets, with long established, successful film production industries, and cinema visits a long-established social activity. Indeed, the first full-length Indian film, Raja Harischandra , was produced in 1913, and by the 1920s, large-scale Indian film studio companies existed, and Mumbai had established itself as an early hub for film making (to become known as Bollywood). See Jones et al. ( 2008 ) for a history of the Indian film industry.

The importance of the Indian film industry to the Indian economy cannot be overstated: in 2012, Indian cinema box office revenues were $1.6 billion (McCarthy, 2014 ), in a services sector which accounts for more than 50% of the Indian economy. Footnote 2 Fetscherin ( 2010 ) suggests that the film industry accounts for approximately 20% of all revenues in the Indian media and entertainment industries. Further, despite the high profile of ‘Bollywood’ which is based in Mumbai, film production also has positive spillover benefits to other local economies, particularly Chennai where film production has long been established, with films made in four key southern Indian languages. There are also notable film production activities in Hyderabad, Karnataka, Kolkata and Kerala that benefit the local economies. Local economy benefits are not restricted to the direct benefits and multiplier effects associated with film production and therefore employment in specific local economies. Bollywood, in particular, also has tourism benefits with Bollywood locations boosting tourist visitor numbers, i.e. an indirect channel through which the Indian film industry contributes to gross domestic product (GDP).

Yet, the Indian film industry currently faces a number of challenges. First, a major challenge remains film piracy which limits the revenues that can be reinvested by producers, distributors and exhibitors. A complicated system of regulations with responsibility shared by a number of national and state level government departments only contributes to the often ineffective nature of policies and laws that should guard against piracy, Jones et al. ( 2008 ). The problem of piracy results in lower revenues across the film industry, and the negative effect on investment in the industry is compounded by the high entertainment tax rates imposed in India.

Second, relative to many countries, domestic cinema ticket prices remain low, Jones et al. ( 2008 ) and see Table 1 . This again results in smaller box office revenues to be shared between film exhibitors, distributors and producers, reducing opportunities for reinvestment across the Indian film industry. This is particularly important at the moment as international film producers are increasingly investing in expensive technology associated with ‘enhanced format’ films, such as 3D and IMAX. Elliott et al. ( 2018 ) have found these films particularly popular with Chinese audiences, but these films require very large production budgets, as well as investment in cinemas by film exhibitors. Nevertheless, despite the costs of producing enhanced format films, they offer the advantage that the piracy of these films is less attractive as the special effects will be much less impressive to viewers when watching pirated films either on television screens or computer monitors. A further issue relating to low ticket prices is that regardless of this advantage, consumers are still purchasing fewer cinema tickets.

Meanwhile, despite difficulties until the early 1990s, the Chinese film market now continues to grow rapidly, both in terms of films produced and audiences’ desire to view films at cinemas. Despite initially slow growth of the film industry in China prior to the 1990s, its film box office revenues were expected to exceed $10 billion in 2016, coming close to overtaking the USA which enjoyed box office revenues of $11 billion in 2015, Shoard ( 2016 ). It is within this context that the performance of the Indian film industry has to be considered. The Indian and Chinese film industries share some similarities. Both countries have adopted economic liberalisation policies since the later years of the twentieth century, and as a result in both countries, the film industry has attracted greater foreign investment. Meanwhile, liberalisation has led to greater competition for domestic films from large budget, internationally produced films, often originating in Hollywood, with both Indian and Chinese audiences keen to watch these films.

This paper seeks to identify the factors that contribute to films’ success in Indian cinemas using an econometric analysis such that film production companies are in a better position to identify strategies to ensure their future success. These strategies relate to film characteristics as well as marketing strategy. Given the importance of the film industry to the Indian economy and the difficulties currently faced by the industry, our analysis is particularly important and timely. We believe this to be the first paper econometrically to estimate the determinants of domestic box office success for the Indian film industry. To do this, an original dataset has been collated and utilised, considering all Bollywood films released in Indian cinemas over the period 2011 to 2015. For each film, released data are collected on the size of production budget; Indian cinema box office revenues; film genre; the use of Bollywood star actors and directors; and the distributor of the film in India. Alternative measures of critical acclaim for each film are also collected. As well as identifying those factors associated with films’ Indian box office success, the results of the statistical analysis are used to develop government policy recommendations.

A literature review covering economic analyses of the film industry, both in India and more broadly, is provided in Sect. 2 . The data and econometric methodology are described in Sect. 3 . Results are reported in Sect. 4 , with discussion of these results, policy implications and conclusions provided in Sect. 5 .

2 Literature review

Despite the large and burgeoning film industry literature, spanning the Economics, Marketing and Management disciplines, there are very few analyses of the Indian film industry. The only econometric analysis of factors impacting on Indian film success is that of Fetscherin ( 2010 ), who considers the variables that affect the opening week and total cinema box office returns of Indian films exhibited in the UK and USA. Fetscherin ( 2010 ) concludes that neither star power nor the previous directing experience of the director impacted on opening week or total box office revenues, and that consumer online reviews, posted on the www.imdb.com website, also had no significant impact on either revenue variable. Our statistical analysis differs as we are interested in the factors determining the success of Indian films in the domestic, Indian market. Arguably, our analysis is also strengthened as we were able to obtain data on film production budgets and film critic review scores and could identify if a film was a sequel. Other analyses of the impact of the Indian film industry include Jones et al. ( 2008 ) and Balasubramanyam ( 2009 ), but a lack of Indian film industry data has resulted in a paucity of Indian analyses despite the high profile of Bollywood. Our analysis contributes directly to this limited literature.

A film represents an experience good, for which full details of the properties and quality of the good cannot be determined, prior to purchase and consumption. Consequently, it is important for consumers to receive quality signals in advance of cinema ticket (or DVD) purchase decisions, to help ensure that consumers select films that best match their preferences. Beyond the Indian market, there is a large literature that considers the factors that determine films’ box office success, and much of the literature highlights factors that can be considered quality signals. See Mckenzie ( 2012 ) for a recent literature survey.

A number of potential quality signals under the control of film production companies have been considered, with research estimating their impact on film box office revenues. A consensus has emerged in the literature that there is a positive, significant relationship between a film’s budget and box office revenues with consumers perceiving higher film budgets as a signal of film quality, Elliott et al. ( 2018 ). Footnote 3 Related to film budget, one of the most expensive costs of producing a film may be the costs of employing high profile star actors and actresses. The use of stars is a very visible signal that production companies are willing to invest large amounts of money in a film, and also signals the actors’ belief in the quality of a film. A number of researchers have considered the impact of employing stars in films, including US analyses of Prag and Casavant ( 1994 ), Ravid 1999 ), Elberse ( 2007 ), Brewer et al. ( 2009 ), Akdeniz and Talay ( 2013 ), the Italian analysis of Bagella and Becchetti ( 1999 ), as well as Fetscherin’s ( 2010 ) Indian analysis. However, results remain mixed, with some but not all studies concluding that the use of stars positively impacts on film box office revenues. Similarly, the use of a high profile film director as a signal quality that may impact positively on box office revenues has been considered by Bagella and Becchetti ( 1999 ) as well as Fetscherin ( 2010 ).

If a film is successful in terms of box office revenues, this may then encourage film production companies to invest in a sequel, as considered by, Basuroy et al. ( 2003 ), Moon et al. ( 2010 ), Akdeniz and Talay ( 2013 ). Similarly, cinemagoers may be eager to pay to view a sequel if they have enjoyed an earlier film in a film franchise. Elliott et al. ( 2018 ) conclude that Chinese audiences are positively attracted to sequel films. The final quality signal under the control of film production and distribution companies is the date of release of a film, with firms keen for films that they think will particularly appeal to audiences to be screened around major holiday periods. This has previously been explored in a US context by Litman ( 1983 ), Sochay ( 1994 ), Einav ( 2007 ) and Brewer et al. ( 2009 ) and is considered in the Indian context in the analysis below.

A second set of potential quality signals that may influence consumers’ film ticket purchase decisions is not under the control of film production companies, namely expert critics’ review scores and online review scores given by members of the general public. The impact of critics’ review scores on box office revenues has been explored by Eliashberg and Shugan ( 1997 ), Basuroy et al. ( 2003 ), Reinstein and Snyder ( 2005 ) in the US context, and by Elliott and Simmons ( 2008 ) using UK data. Nevertheless, Moon et al. ( 2010 ) suggest that consumers may take more note of consumer reviews than those of expert critics. The increasing availability of online review scores posted by non-expert reviewers has led to Elliott et al. ( 2018 ) exploring the impact of these reviews on Chinese box office revenues, concluding that these reviews are positively and significantly related to box office revenues.

All of the quality signals highlighted above, including both those under the control of film production companies, and those associated with expert and non-expert critics are considered in the statistical analysis below.

A crucial issue addressed in the literature is how to take account of the potentially highly skewed distribution of film revenues which may also be characterised by unbounded variance, as identified by Collins et al. ( 2002 ); De Vany and Lee ( 2001 ); De Vany and Walls ( 1996 , 1999 , 2002 ). These characteristics result in film revenue variables violating the classical assumptions required for ordinary least squares (OLS) of variables having well-defined mean and constant and finite variance. De Vany and Walls ( 1999 , 2002 ) have suggested using the Pareto distribution to deal with the excessive kurtosis; Collins et al. ( 2002 ) used an ordered Probit model with threshold revenue values imposed, while Walls ( 2005 ) recommends using a t-skew distribution. These issues will be addressed in Sect. 3 .

3 Data and methodology

The dataset comprises all Bollywood films screened in Indian cinemas over five years, 2011–2015 for which data on all required variables were available. This gives rise to a dataset of 245 films as data were missing on key variables for a number of films released in India during this period. Nevertheless, we believe this to be the largest dataset collated to date on the Indian film industry. Variable definitions and data sources are detailed in Appendix 1, while descriptive statistics for the continuous variables are reported in Table 2 .

Both total Indian film box office revenues and opening week box office revenues are used as dependent variables ( REVENUE ). While much of the literature focuses on factors that determine total box office revenues, we also consider opening week revenues as these are particularly important in the Indian film market context given the rapidity with which films are pirated, with film revenues often falling rapidly within the first two weeks after they are released. Both variables are reported in 10 million Indian Rupees INR (crore) and converted into real values taking 2010 as the base year and using World Bank Consumer Prices Index (CPI) data from 2011 to 2015 to deflate the budget and box office revenue values during 2011–2015. Hence, the budget and revenue variables used are in 2010 constant prices. As is standard in the film industry literature, the revenue and budget variables are logged in the statistical analysis. In Sect. 2 , we highlighted that previously researchers have identified that box office revenues may not be normally distributed. We tested for skewness and kurtosis of our revenue variables. As anticipated, non-logged opening week and total revenues do suffer from kurtosis with values of 4.63 and 5.30, respectively. However, the skewness values are less concerning at 2.08 and 2.17 for opening week and total revenues, respectively. Reassuringly, the values for the logged variables indicate less of a problem with skewness and kurtosis, as the values for skewness are − 1.59 and − 1.08, and with kurtosis values of 2.61 and 1.23, again for opening week and total revenues, respectively.

As well as BUDGET , a number of further potential quality signals are used as explanatory variables. A dummy variable STARPOWER was created, indicating the reputation of the leading actor/actress. There are many rankings of Bollywood actors and actresses but the TIMES Celebex ranking is often considered the most well respected. The data of 2011 are not available as the ranking was only launched in 2012, Guptal ( 2015 ). Hence, we consider a film to have an actor/actress with star power if they have been in the TIMES Celebex ranking at any time during 2012–2015. There are approximately five actors and five actresses in the ranking in any one year, with persistence of actors and actresses in the top five ranking for at least one year and sometimes throughout the period 2012–2015. See Appendix 2 for a list of actors and actresses who are considered to have star power in our analysis. An alternative star power explanatory variable was also created, and rather than a dummy variable, this was a count variable of the number of films that the leading actor/actress had been in during their career, the data taken from www.imdb.com . This is in line with Chang and Ki ( 2005 ) and Fetscherin ( 2010 ) who similarly count the number of films an actor or actress has appeared in as a measure of star power. However, the coefficient on this variable was insignificantly different from zero; this also the case when the variable plus the squared variable were used reflecting a possible nonlinear relationship between star power and box office revenues. Hence, the statistical analysis continued using the dummy STARPOWER variable. As a further robustness check, the regression analysis was repeated using an interaction variable STARPOWER * ( logged ) BUDGET , but again, the coefficient on this explanatory variable was insignificantly different from zero so results with this interaction variable were excluded from the model. Again following Chang and Ki ( 2005 ) and Fetscherin ( 2010 ), a DIRECTORPOWER variable was created by counting the number of films a director had previously directed to reflect the star power and experience of a director.

Initially, regressions were run including a quality signal variable of Times of India critics’ film review scores, CRITIC . The reviews in this newspaper were selected as the Times of India is the largest selling English daily newspaper sold in India. However, this quality signal was not found to influence cinemagoers significantly and it was dropped from the analysis. Instead, mean online review scores for films posted on the internationally well-known website www.imdb.com were collected and used as an alternative quality signal, ONLINEREVIEW . Audiences will often submit online review scores very soon after films’ release that further potential audiences can access easily prior to deciding which films to watch at the cinema. Moon et al. ( 2010 ) conclude that for potential audiences, online reviews are a better quality signal than expert review scores.

A dummy variable, DISTRIBUTOR , was included to indicate a film distributed in India by one of the ten largest film distribution companies. However, given that the coefficient on this variable was consistently found to be insignificantly different from zero, alternative distributor dummy variables were also created. Given the traditional importance of family firms in the Indian economy, DISTRIBUTORFAM indicates that the distribution company is family owned, while DISTRIBUTORFAM10 indicates that a film was distributed by one of the ten largest distribution companies that are family owned. Only the coefficient on DISTRIBUTORFAM10 was ever found to be significantly different from zero so this is the variable used in the analysis below.

A SEASON dummy variable, taking the value unity when a film was released in India during key Muslim, Hindu and Christian festivals as well as around Independence Day, Republic Day and New Year, was also included to aid comparability with studies published that consider the impact on revenues of films released around major holiday periods. See Appendix 3 for details. Yet, again the coefficient on this explanatory variable was found to be insignificantly different from zero. Hence, alternative forms of this variable were considered. Successively, less important festivals were assigned a zero value, and the regressions rerun to test if the coefficient on the SEASON dummy variable became significantly different from zero. However, even when only the three largest festivals were assigned a value of unity, namely Christmas, Diwali and Eid, the coefficient on the SEASON dummy variable remains insignificantly different from zero. It is this final iteration of the SEASON dummy variable which is used in the results below. Both the DISTRIBUTOR and SEASON dummy variables can be considered potential quality signals as films expected to do well at the box office are likely to attract major distributors, with production and distribution companies keen to release films that they anticipate will do well around holiday periods.

Alternatively, potential film audiences may only have limited leisure time and have to select between alternative leisure activities. Izquierdo Sanchez et al. ( 2016 ) highlight that when key football tournaments take place, potential European cinema audiences may choose instead to watch football matches. Hence, to test whether potential Indian film audiences similarly select between cinema visits and the watching of major cricket matches, a dummy variable CRICKET is included that takes the value unity for films released during the Indian Premier League (IPL) season. Footnote 4

A set of genre dummy variables was included as these are commonly included in statistical analyses in the literature. For example, Elliott and Simmons ( 2008 ) conclude that, in the UK, films targeted at children do well, while Ravid and Basuroy ( 2004 ) consider US R-rated films, which are targeted at adult audiences. In our analysis, we categorised the films into the following genres COMEDY , DRAMA , ROMANCE and ACTION/THRILLER where COMEDY was treated as the control category of genre. Finally, a dummy SEQUEL variable was included, taking the value unity if a film was a sequel in a film franchise. Audiences may take a film’s sequel status as a signal of quality if they have enjoyed another film in a film franchise, while film production companies may be keen to invest in a sequel if a previous film in a franchise has had box office success.

Inspection of the correlation matrices indicated that multicollinearity is not expected to be a particular concern in the statistical analysis. Footnote 5 The lack of multicollinearity is confirmed in the results, Table 3 .

3.2 Methodology

The model first estimated was an ad hoc model with explanatory variables chosen following a thorough review of the film industry literature. Hence, we started by estimating the following equation:

for movie i, e denotes the error term.

Initially, the model was estimated using OLS, with robust standard errors to correct for potential heterscedasticity in the residuals. However, if there is endogeneity or reverse causality in the model, then the OLS results will be biased and unfit for drawing inferences. Potentially, there may be reverse causality from REVENUE towards BUDGET as production companies decide film budget levels partly on the expectation of film revenues that are likely to accrue. Further, as highlighted in Sect. 2 , it is generally accepted in the film industry literature that film budget may be a quality signal to potential audiences, with consumers believing that higher budget films are likely to be of higher quality. To test this hypothesis, we estimated the following model (Eq. 2 ) and employed the GMM C test to assess whether BUDGET is endogenous in our model.

where z denotes the residuals obtained from the estimation of Eq. 1 and u is the error term.

The quality signal CRITIC was dropped from the model because it is determined post-release of the movie and therefore cannot have any influence on the budget of a movie. We use STARPOWER and DIRECTORPOWER as the instruments of BUDGET as the estimation results for Eq. 1 indicated that neither of these variables affect REVENUE directly. Both variables may impact on film budget as it may be more expensive to employ film stars and/or a director with greater previous experience.

The results indicated that BUDGET is indeed endogenous, and so, to control for this issue, we continued our estimation of the model in Eq. 1 by employing the instrumental variable general method of moments (GMM) approach. Footnote 6 Both the OLS and GMM estimation results indicated that expert critic ratings have no effect on the box office revenues of films. Hence, in the results reported in Sect. 4 , the CRITIC variable is replaced with the ONLINEREVIEW variable as a quality signal outside the control of film production companies. Finally, note that the methods proposed by Collin et al. ( 2002 ); De Vany and Walls ( 1999 , 2002 ) and Walls ( 2005 ) for dealing with non-normally distributed film revenues have the cost attached that because of computational complexity, it is only possible to estimate a reduced form model rather than a structural model. As we are able to confirm that BUDGET is in fact endogenously determined, and because the skewness and kurtosis values for our logged REVENUE variables do not give cause for major concern, we are reassured that it is appropriate to use the GMM approach, the results of which are reported in Sect. 4 .

4 Econometric results

Regression results for the key film box office revenue dependent variables are reported in Table 3 , controlling for endogeneity as outlined in the section above. The first thing to note is the robustness of the results, regardless of whether total or opening week box office revenues are selected as the dependent variable. This result is in line with expectations given the short period of time that films remain popular on Indian cinema screens, and the rapidity with which films are pirated. The Hansen J statistic indicates that the instruments are valid as are the over-identification restrictions.

The magnitude of a film’s budget is found to be key to a film’s success: budget has a positive, significant effect on both opening week box office revenues and total revenues. A film’s budget is one potential quality signal to consumers of the film’s quality. Unlike for many goods, film companies are often happy to reveal large budgets attached to film production. A large budget indicates a production company’s faith in the quality of film being produced, and film budget data are routinely reported on websites such as www.imdb.com . Indian film budgets typically remain low compared to those of Hollywood films (Balasubramanyam 2009 ), but as in previous USA and UK studies, a higher budget is associated with film box office success.

The other signal of quality that is found to be a crucial influencer is the mean of online review scores posted by the general public on www.imdb.com . Again, the coefficient on this variable is always positive and significant, regardless of whether we consider its impact on opening week revenues or total revenues. This impact of online reviews is in line with that found in Elliott et al. ( 2018 ) in the Chinese film market context and highlights the importance for production and distribution companies of establishing and maintaining effective communication with potential audiences.

No consensus has been reached in the literature to date on whether films enjoy greater revenues if they are released around major holidays. For example, Litman ( 1983 ) suggests that Christmas is the optimum time to release a film in the USA, while Sochay ( 1994 ) concludes that the summer holiday period is preferred, with Brewer et al. ( 2009 ) supporting this result but also indicating that in the US films perform better if they are released around Thanksgiving. Our results indicate that release date has no significant impact on a film’s box office revenues in the Indian market despite testing various formulations of the SEASON dummy variable. This may reflect the diversity of holiday dates in the Indian calendar as highlighted in Appendix 3. Similarly, in the econometric analysis, we test whether films perform significantly worse if released in the IPL season but find no significant evidence of this. This result indicates that Indian audiences do not substitute between viewing films at the cinema and watching major cricket matches.

If a film is a sequel, our results suggest that this may have a limited, positive impact on a film’s success. Consequently, a film’s sequel status may be a weak indicator of film quality. Meanwhile, while films distributed by an Indian top ten distribution company that is family owned may not perform significantly better in terms of total box office revenues, they enjoy greater box office success in the opening week of general Indian release, at least at a ten per cent significant level. This suggests that until film quality information is spread through word-of-mouth, for example, through IMDB online reviews, the distributor of films can have some impact on opening week revenues.

Finally, the coefficients on the genre dummy variables indicate that films that can be categorised as romantic, action/thriller or drama all perform significantly worse in terms of box office revenues than the excluded film category – comedies.

Note that in initial regressions, the use of star actors and actresses and major distributors were not found to impact significantly on box office revenues, even though both may be considered as potential signals of a film’s quality. These variables have been found to have a positive, significant effect on revenues in a number of country contexts previously, see for example Elliott et al. ( 2018 ). Nevertheless, the result in the current analysis is in line with that of Fetscherin ( 2010 ) who also considers the Indian market. This result is encouraging as it indicates that two potential barriers to entry, namely the use of costly stars and distributors, are not important in the Indian film industry context.

The analysis above contributes directly to our understanding of the question posed in this research paper, namely what factors contribute to a film’s box office success in the Indian market. Results suggest that two factors are key and are signals of film quality, namely film budget and online review scores. The first, but not the second, is under the control of film production companies.

5 Discussion and conclusions

Higher film budgets and better online reviews result in higher Indian box office revenues for Bollywood films, a result in line with conclusions previously drawn for the Chinese film market, Elliott et al. ( 2018 ). Comparisons between the Indian and Chinese film markets are arguably appropriate as there are similarities between these two major Asian economies that similarly have liberalised in recent years, both subsequently enjoying substantial economic growth. However, while economic growth is associated with greater spending power at least for many consumers, demand for Indian films at Indian cinemas has stagnated, while in China, it has flourished. Other potential quality signals found to impact on Chinese film revenues, namely the production of sequels, the use of stars and major distribution companies, do not significantly affect Indian film revenues. These results may be indicative of a potentially competitive Indian film industry. While admittedly large film budget is important for box office success, production firms including new entrants do not need to rely on the use of stars or major distribution companies. This is reassuring as it is potentially more difficult for new production company market entrants to attract stars and major distribution companies to film projects. Note that Balasubramanyam ( 2009 ) also highlights the competitive nature of the Indian film industry, but rather indicates the lack of horizontal and vertical integration, the importance of family firms and the industry’s spread across the country. Yet, the competitive nature of the Indian film industry does not explain its recent difficulties, namely falling cinema attendance. As Elliott et al. ( 2018 ) note, the Chinese film industry is also increasingly becoming competitive.

Our results indicate that production firms should work to obtain financial backing for film projects, be that domestic funding or international funding, including from major Hollywood firms. Yet, while a competitive market is typically seen as advantageous as firms compete to satisfy consumer demands, can learn from each other, and have an incentive to produce efficiently, Indian film production companies should also consider whether too many films are currently being produced. This is particularly pertinent as consumer demand for watching films at the cinema is declining. Arguably fewer, larger budget, films should be produced with production companies focusing on producing higher quality films more likely to attract positive online reviews. Any marketing activities that may encourage positive online reviews should also be considered, and firms need to be aware that comedy films appear to be most popular with Indian audiences. Meanwhile, the timing of the release of a film in India appears irrelevant to its box office success. This may be explained by the diversity of audiences who speak different languages, and who celebrate festivals associated with different religions.

Producing films that can be exported successfully to increasingly sophisticated and better off diaspora is likely to remain a sensible strategy for film production companies, particularly as the Indian diaspora are believed to exceed 20 million, Jones et al. ( 2008 ). This strategy for Indian films has already been adopted, with the USA and UK being profitable export markets for Indian films, Eliashberg et al. ( 2006 ); Fetscherin ( 2010 ). However, exports of Indian films only make up approximately 10% of box office revenues and this figure has fallen slightly in recent years from 10.6% in 2010 to 9.2% in 2014. Footnote 7 Examples of particularly successful Bollywood films overseas include Monsoon Wedding (2001) and Slumdog Millionaire (2008). These are both relatively large budget films so reinforcing the importance of greater film budgets. The Industrial Development Bank of India (IDBI) set up India’s first major film fund in 2002, Jones et al. ( 2008 ). This initiative is important, but further large-scale investment is required, and the likelihood is that this will partly be funded by overseas, probably Hollywood investment, as well as domestic funds.

Nevertheless, attempts by Hollywood to produce films for domestic audiences have not always been successful, with locally produced films performing better at the box office. Even using Indian casts, crew and directors, it appears that US-backed films can struggle with possible ‘cultural discount’. The cultural discount hypothesis has already received support in other East Asian film markets, as discussed by, for example, Lee ( 2006 , 2009 ), Fu and Lee ( 2008 ), Moon et al. ( 2015 ). Our results above highlight the importance of film budgets, with higher budget films performing significantly better at the Indian box office. Then, the challenge will be to produce films that appeal to domestic audiences, and to do this, the notion of cultural discount will have to be at the forefront of producers’ concerns. The issue of cultural distance is complicated in the case of India by the number of languages in which films are produced, for example with films regularly made in the Bengali; Bhojpuri; Hindi; Kannada; Tamil; and Telugu languages, but the lack of a common language immediately limits the appeal of films to some Indian audiences, creating cultural distance even within country boundaries. Nevertheless, revenues are made from dubbing films into alternative local languages, or by remaking films with regional stars (Balasubramanyam 2009 ).

The challenge of producing big budget films that appeal to audiences is further complicated as evidence suggests that Indian film audiences are becoming increasingly sophisticated in their tastes, for example rejecting more formulaic plots. Meanwhile, middle-class film viewers are increasingly choosing to watch films in the comfort of their homes via cable television subscriptions or the Internet. Footnote 8

The statistical analysis above has a number of limitations, all reflecting data availability problems. Data are restricted to Bollywood films, although results are expected to be comparable for the film industry more broadly across India. This is an area for future research. Data could not be obtained on film advertising expenditures, the number of screens on which films are exhibited in their opening week, major Indian film award nominations both in India and internationally, and any enhanced format features of films released in India. Nevertheless, results for the Chinese film market reported by Elliott et al. ( 2018 ) indicate that enhanced format films are likely to become increasingly important in attempts to attract cinema audiences as well as to deter piracy. Consequently, yet again the importance of large film budgets is highlighted as the production of 3D or IMAX films is particularly costly.

Ultimately, the Indian film industry has faced increasing difficulties in recent years: even increased investment in the film industry by large Hollywood companies and the release in India of internationally produced films has not stemmed falls in audience numbers. The industry is competitive with the capacity to benefit local economies across the country, but the key theme to emerge from this analysis is that funding for large budget films is crucial, and in the future, this may include funding for more enhanced format films. Other mature film markets across the world including in the USA and UK are also struggling to attract cinema audiences, and as a result, film markets are increasingly competitive, with competition from internationally as well as domestically produced films. The Indian film industry cannot afford to delay investments. The continued importance of the Indian film industry cannot be overstated. Governments, both state level and national, must consider whether their policies are sufficient to encourage film funding, should question whether entertainment taxes stifle investment and if policies are sufficiently effective in combating film piracy.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics, www.uis.unesco.org .

World Bank. World Development Indicators.

Note that unlike in many industries where films try not to reveal their costs of production for fear of providing information to competitors, film budgets are typically published, for example with data readily available on websites such as www.imdb.com .

The Indian Premier League (IPL) is the most popular cricketing event in India and is also the most watched T20 cricket league internationally, Barrett ( 2016 ).

Correlation results withheld for the sake of brevity but available on request.

OLS results are provided in Appendix 4 for thoroughness and to illustrate the robustness of our GMM results.

https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2015/03/FICCI-KPMG_2015.pdf .

https://www.moviemaker.com/archives/moviemaking/directing/articles-directing/the-fall-of-bollywood-3235/ .

Akdeniz, M. B., & Talay, M. B. (2013). Cultural variations in the use of marketing signals: A multilevel analysis of the motion picture industry. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41 (5), 601–624.

Article Google Scholar

Bagella, M., & Becchetti, L. (1999). The determinants of motion picture box office performance: Evidence from movies produced in Italy. Journal of Cultural Economics, 23, 237–256.

Balasubramanyam, V. (2009). The contribution of India’s movie industry to the economy; all show and no substance? conference paper presented at the British Northern Universities India Forum 3rd Annual Conference . India: Hyderabad.

Google Scholar

Barrett, C. (2016). Big Bash League jumps into top 10 of most attended sports leagues in the world. The Sydney Morning Herald, 11th January, 2016. Accessed at: http://www.smh.com.au/sport/cricket/big-bash-league-jumps-into-top-10-of-most-attended-sports-leagues-in-the-world-20160110-gm2w8z .

Basuroy, S., Chatterjee, S., & Ravid, S. A. (2003). How critical are critical reviews? The box office effects of film critics, star power and budgets. Journal of Marketing, 67, 103–117.

Brewer, S. M., Kelley, J. M., & Jozefowicz, J. J. (2009). A blueprint for success in the US film industry. Applied Economics, 41 (5), 589–606.

Chang, B.-H., & Ki, E.-J. (2005). Devising a practical model for predicting theatrical movie success: Focusing on the experience good property. Journal of Media Economics, 18 (4), 247–269.

Collins, A., Hand, C., & Snell, M. (2002). What Makes a Blockbuster? Economic Analysis of Film Success in the UK. Managerial and Decision Economics, 23, 343–354.

De Vany, A., & Lee, C. (2001). Quality Signals in Information Cascades and the Dynamics of the Distribution of Motion Picture Box Office Revenues. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 25, 593–614.

De Vany, A., & Walls, W. D. (1996). Bose-Einstein Dynamics and Adoptive Contracting in the Motion Picture Industry. Economic Journal, 106, 1493–1514.

De Vany, A., & Walls, W. D. (1999). Uncertainty in the movies: Can star power reduce the terror of the box office? Journal of Cultural Economics, 23, 285–318.

De Vany, A., & Walls, W. D. (2002). Does Hollywood Make Too Many R-Rated Movies? Risk, Stochastic Dominance and the Illusion of Expectations. Journal of Business, 75, 425–451.

Einav, L. (2007). Seasonality in the U.S. motion picture industry. Rand Journal of Economics, 38 (1), 127–145.

Elberse, A. (2007). The power of stars: Do star actors drive the success of movies? Journal of Marketing, 71, 102–120.

Eliashberg, J., Elberse, A., & Leenders, M. (2006). The motion picture industry: Critical issues in practice, current research, and new research directions. Marketing Science, 25 (6), 638–661.

Eliashberg, J., & Shugan, S. (1997). Film critics: Influencers or predictors? Journal of Marketing, 61 (2), 68–78.

Elliott, C., Konara, P., Ling, H., Wang, C., & Wei, Y. (2018). Behind film performance in China’s changing institutional context: The impact of signals. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 35 (1), 63–95.

Elliott, C., & Simmons, R. (2008). Determinants of box office success: The impact of quality signals. Review of Industrial Organization, 33, 93–111.

Fetscherin, M. (2010). The main determinants of Bollywood movie box office sales. Journal of Global Marketing, 23 (5), 461–476.

Fu, W. W., & Lee, T. K. (2008). Economic and cultural influences on the theatrical consumption of foreign films in Singapore. Journal of Media Economics, 21 (1), 1–27.

Guptal, P. (2015). Salman Khan tops the Times Celebex ranking for the year 2014. The Times of India, 5th April, 2015. Accessed at: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/entertainment/hindi/bollywood/news/Salman-Khan-tops-the-Times-Celebex-ranking-for-the-year-2014/articleshow/46804927.cms .

Izquierdo Sanchez, S., Elliott, C., & Simmons, R. (2016). Substitution between leisure activities: A quasi-natural experiment using sports viewing and cinema attendance. Applied Economics, 48 (40), 3848–3860.

Jones, G., Arora, N., Mishra, S., & Lefort, A. (2008). Can Bollywood go global? Harvard Business School discussion paper, 9-806-040.

Lee, F. F. (2006). Cultural discount and cross-culture predictability: Examining the box office performance of American movies in Hong Kong. Journal of Media Economics, 19 (4), 259–278.

Lee, F. F. (2009). Cultural discount of cinematic achievement: The academy awards and U.S. movies’ East Asian box office. Journal of Cultural Economics, 33 (4), 239–263.

Litman, B. (1983). Predicting success of theatrical movies: An empirical study. Journal of Popular Culture, 16, 159–175.

McCarthy, N. (2014). Bollywood: India’s film industry by the numbers. Forbes, September 3rd.

McKenzie, J. (2012). The economics of movies: A literature survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 26 (1), 42–70.

Moon, S., Bayus, B. L., Yi, Y., & Kim, J. (2015). Local consumers’ reception of imported and domestic movies in the Korean movie market. Journal of Cultural Economics, 39 (1), 99–121.

Moon, S., Bergey, P. K., & Iacobucci, D. (2010). Dynamic effects among movie ratings, movie revenues, and viewer satisfaction. Journal of Marketing, 74 (1), 108–121.

Prag, J., & Casavant, J. (1994). An empirical study of the determinants of revenues and marketing expenditures in the motion picture industry. Journal of Cultural Economics, 18, 217–235.

Ravid, S. A. (1999). Information, blockbusters, and stars: A study of the film industry. Journal of Business, 72 (4), 463–492.

Ravid, S. A., & Basuroy, S. (2004). Managerial objectives, the R-rating puzzle, and the production of violent films. Journal of Business, 77 (2), S155–S192.

Reinstein, D., & Snyder, C. (2005). The influence of expert reviews on consumer demand for experience goods: A case study of movie critics. Journal of Industrial Economics, 103 (1), 27–51.

Shoard, C. (2016). China’s box office certain to overtake US as takings up 50% in 2016’s first quarter. The Guardian. Accessed at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/apr/01/chinas-box-office-certain-to-overtake-us-as-takings-up-50-in-2016s-first-quarter .

Sochay, S. (1994). Predicting the performance of motion pictures. Journal of Media Economics, 53, 27–52.

Walls, W. D. (2005). Modelling heavy tails and skewness in film returns. Applied Financial Economics, 15, 1181–1188.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to participants at the British Northern Universities India Forum workshop at the University of Bradford, March 2016, and the International Symposium on Innovation, Catch-Up and Internationalisation: Comparative Studies of China, India and other Emerging Economies, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, Chengdu, July 2016, for very valuable comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Business, Law and Social Science, University of Derby, Kedleston Road, Derby, DE22 1GB, UK

Sayantan Ghosh Dastidar

Aston Business School, Aston University, Birmingham, B4 7ET, UK

Caroline Elliott

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Caroline Elliott .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1: Variable information

Appendix 2: star actors and actresses.

- Full year data on actresses in the ranking were not provided until 2013

Appendix 3: List of festivals and holidays

- Where not specified the date of festivals varies from year to year

Appendix 4: OLS regression results

- Multicollinearity is confirmed not to be an issue as we obtained mean VIF scores of 1.3 and 1.32 with total revenue and opening week revenue, respectively, as dependent variables (both VIF scores considerably lower than 10)

- Robust standard errors in brackets; * p < 0.10; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01

Rights and permissions