PODCAST: HISTORY UNPLUGGED J. Edgar Hoover’s 50-Year Career of Blackmail, Entrapment, and Taking Down Communist Spies

The Encyclopedia: One Book’s Quest to Hold the Sum of All Knowledge PODCAST: HISTORY UNPLUGGED

The Atomic Bomb: Arguments in Support Of The Decision

Note: This section is intended as an objective overview of the decision to use the atomic bomb for new students of the issue. For the other side of the issue, go here.

Argument #1: The Atomic Bomb Saved American Lives

The main argument in support of the decision to use the atomic bomb is that it saved American lives which would otherwise have been lost in two D-Day-style land invasions of the main islands of the Japanese homeland. The first, against the Southern island of Kyushu, had been scheduled for November 1 (Operation Torch). The second, against the main island of Honshu would take place in the spring of 1946 (Operation Coronet). The two operations combined were codenamed Operation Downfall. There is no doubt that a land invasion would have incurred extremely high casualties, for a variety of reasons. For one, Field Marshall Hisaichi Terauchi had ordered that all 100,000 Allied prisoners of war be executed if the Americans invaded. Second, it was apparent to the Japanese as much as to the Americans that there were few good landing sites, and that Japanese forces would be concentrated there. Third, there was real concern in Washington that the Japanese had made a determination to fight literally to the death. The Japanese saw suicide as an honorable alternative to surrender. The term they used was gyokusai, or, “shattering of the jewel.” It was the same rationale for their use of the so-called banzai charges employed early in the war. In his 1944 “emergency declaration,” Prime Minister Hideki Tojo had called for “100 million gyokusai,” and that the entire Japanese population be prepared to die.

For American military commanders, determining the strength of Japanese forces and anticipating the level of civilian resistance were the keys to preparing casualty projections. Numerous studies were conducted, with widely varying results. Some of the studies estimated American casualties for just the first 30 days of Operation Torch. Such a study done by General MacArthur’s staff in June estimated 23,000 US casualties.

U.S. Army Chief of Staff George Marshall thought the Americans would suffer 31,000 casualties in the first 30 days, while Admiral Ernest King, Chief of Naval Operations, put them between 31,000 and 41,000. Pacific Fleet Commander Admiral Chester Nimitz, whose staff conducted their own study, estimated 49,000 U.S casualties in the first 30 days, including 5,000 at sea from Kamikaze attacks.

Studies estimating total U.S. casualties were equally varied and no less grim. One by the Joint Chiefs of Staff in April 1945 resulted in an estimate of 1,200,000 casualties, with 267,000 fatalities. Admiral Leahy, Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief, estimated 268,000 casualties (35%). Former President Herbert Hoover sent a memorandum to President Truman and Secretary of War Stimson, with “conservative” estimates of 500,000 to 1,000,000 fatalities. A study done for Secretary of War Henry Stimson’s staff by William Shockley estimated the costs at 1.7 to 4 million American casualties, including 400,000-800,000 fatalities.

General Douglas MacArthur had been chosen to command US invasion forces for Operation Downfall, and his staff conducted their own study. In June their prediction was American casualties of 105,000 after 120 days of combat. Mid-July intelligence estimates placed the number of Japanese soldiers in the main islands at under 2,000,000, but that number increased sharply in the weeks that followed as more units were repatriated from Asia for the final homeland defense. By late July, MacArthur’s Chief of Intelligence, General Charles Willoughby, revised the estimate and predicted American casualties on Kyushu alone (Operation Torch) would be 500,000, or ten times what they had been on Okinawa.

All of the military planners based their casualty estimates on the ongoing conduct of the war and the evolving tactics employed by the Japanese. In the first major land combat at Guadalcanal, the Japanese had employed night-time banzai charges—direct frontal assaults against entrenched machine gun positions. This tactic had worked well against enemy forces in their Asian campaigns, but against the Marines, the Japanese lost about 2,500 troops and killed only 80 Marines.

At Tarawa in May 1943, The Japanese modified their tactics and put up a fierce resistance to the Marine amphibious landings. Once the battered Marines made it ashore, the 4,500 well-supplied and well-prepared Japanese defenders fought almost to the last man. Only 17 Japanese soldiers were alive at the end of the battle.

On Saipan in July 1944, the Japanese again put up fanatical resistance, even though a decisive U.S. Navy victory over the Japanese fleet had ended any hope of their resupply. U.S. forces had to burnthen out of holes, caves, and bunkers with flamethrowers. Japanese forces staged multiple banzai attacks. At the end of the battle the Japanese staged a final banzai that included wounded men, some of them on crutches. Marines were forced to mow them down. Meanwhile, on the north end of the island a thousand civilians threw committed suicide by jumping from the cliff to the rocks below after being promised an honorable afterlife by Emperor Hirohito, and after being threatened with death by the Japanese army. In the fall of 1944, Marines landed on the small island of Peleliu, just east of the Philippines, for what was supposed to be a four-day mission. The battle lasted two months. At Peleliu, the Japanese unveiled a new defense strategy. Colonel Kunio Nakagawa, the Japanese commander, constructed a system of heavily fortified bunkers, caves, and underground positions, and waited for the Marines to attack them, and they replaced the fruitless banzai attacks with coordinated counterattacks. Much of the island was solid volcanic rock, making the digging of foxholes with the standard-issue entrenching tool impossible. When the Marines sought cover and concealment, the terrain’s jagged, sharp edges cut up their uniforms, bodies, and equipment. The plan was to make Peleliu a bloody war of attrition, and it worked well. The fight for Umurbrogol Mountain is considered by many to be the most difficult fight that the U.S. military encountered in the entire Second World War. At Peleliu, U.S. forces suffered 50% casualties, including 1,794 killed. Japanese losses were 10,695 killed and only 202 captured. After securing the Philippines and delivering yet another shattering blow to the Japanese navy, the Americans landed next on Iwo Jima in February 1945, where the main mission was to secure three Japanese airfields. U.S. Marines again faced an enemy well entrenched in a vast network of bunkers, hidden artillery, and miles of underground tunnels. American casualties on Iwo Jima were 6,822 killed or missing and 19,217 wounded. Japanese casualties were about 18,000 killed or missing, and only 216 captured. Meanwhile, another method of Japanese resistance was emerging. With the Japanese navy neutralized, the Japanese resorted to suicide missions designed to turn piloted aircraft into guided bombs. A kamikaze air attack on ships anchored at sea on February 21 sunk an escort carrier and did severe damage to the fleet carrier Saratoga. It was a harbinger of things to come.

After Iwo Jima, only the island of Okinawa stood between U.S. forces and Japan. Once secured, Okinawa would be used as a staging area for Operation Torch. Situated less than 400 miles from Kyushu, the island had been Japanese territory since 1868, and it was home to several hundred thousand Japanese civilians. The Battle of Okinawa was fought from April 1 – June 22, 1945. Five U.S. Army divisions, three Marine divisions, and dozens of Navy vessels participated in the 82-day battle. The Japanese stepped up their use of kamikaze attacks, this time sending them at U.S. ships in waves. Seven major kamikaze attacks took place involving 1,500 planes. They took a devastating toll—both physically and psychologically. The U.S. Navy’s dead, at 4,907, exceeded its wounded, primarily because of the kamikaze.

On land, U.S. forces again faced heavily fortified and well-constructed defenses. The Japanese extracted heavy American casualties at one line of defense, and then as the Americans began to gain the upper hand, fell back to another series of fortifications. Japanese defenders and civilians fought to the death (even women with spears) or committed suicide rather than be captured. The civilians had been told the Americans would go on a rampage of killing and raping. About 95,000 Japanese soldiers were killed, and possibly as many as 150,000 civilians died, or 25% of the civilian population. And the fierce resistance took a heavy toll on the Americans; 12,513 were killed on Okinawa, and another 38,916 were wounded.

The increased level of Japanese resistance on Okinawa was of particular significance to military planners, especially the resistance of civilians. This was a concern for the American troops as well. In the Ken Burns documentary The War (2007), a veteran Marine pilot of the Okinawa campaign relates his thoughts at the time about invading the home islands:

By then, our sense of the strangeness of the Japanese opposition had become stronger. And I could imagine every farmer with his pitchfork coming at my guts; every pretty girl with a hand grenade strapped to her bottom, or something; that everyone would be an enemy.

Although the estimates of American casualties in Operation Downfall vary widely, no one doubts that they would have been significant. A sobering indicator of the government’s expectations is that 500,000 Purple Heart medals (awarded for combat-related wounds) were manufactured in preparation for Operation Downfall.

Argument #1.1: The Atomic Bomb Saved Japanese Lives

A concurrent, though ironic argument supporting the use of the Atomic bomb is that because of the expected Japanese resistance to an invasion of the home island, its use actually saved Japanese lives. Military planners included Japanese casualties in their estimates. The study done for Secretary of War Stimson predicted five to ten million Japanese fatalities. There is support for the bomb even among some Japanese. In 1983, at the annual observance of Hiroshima’s destruction, an aging Japanese professor recalled that at war’s end, due to the extreme food rationing, he had weighed less than 90 pounds and could scarcely climb a flight of stairs. “I couldn’t have survived another month,” he said. “If the military had its way, we would have fought until all 80 million Japanese were dead. Only the atomic bomb saved me. Not me alone, but many Japanese, ironically speaking, were saved by the atomic bomb.”

Argument #1.2: It Was Necessary to Shorten the War

Another concurrent argument supporting the use of the Atomic bomb is that it achieved its primary objective of shortening the war. The bombs were dropped on August 6 and 9. The next day, the Japanese requested a halting of the war. On August 14 Emperor Hirohito announced to the Japanese people that they would surrender, and the United States celebrated V-J Day (Victory over Japan). Military planners had wanted the Pacific war finished no later than a year after the fall of Nazi Germany. The rationale was the belief that in a democracy, there is only so much that can reasonably be asked of its citizen soldiers (and of the voting public).

As Army Chief of Staff George Marshall later put it, “a democracy cannot fight a Seven Years’ war.” By the summer of 1945 the American military was exhausted, and the sheer number of troops needed for Operation Downfall meant that not only would the troops in the Pacific have to make one more landing, but even many of those troops whose valor and sacrifice had brought an end to the Nazi Third Reich were to be sent Pacific. In his 2006 memoir, former 101st Airborne battalion commander Richard Winters reflected on the state of his men as they played baseball in the summer of 1945 in occupied Austria (Winters became something of a celebrity after his portrayal in the extremely popular 2001 HBO series Band of Brothers):

During the baseball games when the men were stripped to their waists, or wearing only shorts, the sight of all those battle scars made me conscious of the fact that other than a handful of men in the battalion who had survived all four campaigns, only a few were lucky enough to be without at least one scar. Some men had two, three, even four scars on their chests, backs, arms, or legs. Keep in mind that…I was looking only at the men who were not seriously wounded.

Supporters of the bomb wonder if it was reasonable to ask even more sacrifice of these men. Since these veterans are the men whose lives (or wholeness) were, by this argument, saved by the bomb, it is relevant to survey their thoughts on the matter, as written in various war memoirs going back to the 1950s. The record is mixed. For example, despite Winters’ observation above, he seemed to have reservations about the bomb: “Three days later, on August 14, Japan surrendered. Apparently the atomic bomb carried as much punch as a regiment of paratroopers. It seemed inhumane for our national leaders to employ either weapon on the human race.”

His opinion is not shared by other members of Easy Company, some of whom published their own memoirs after the interest generated by Band of Brothers. William “Wild Bill” Guarnere expressed a very blunt opinion about the bomb in 2007:

We were on garrison duty in France for about a month, and in August, we got great news: we weren’t going to the Pacific. The U.S. dropped a bomb on Hiroshima, the Japanese surrendered, and the war was over. We were so relieved. It was the greatest thing that could have happened. Somebody once said to me that the bomb was the worst thing that ever happened, that the U.S. could have found other ways. I said, “Yeah, like what? Me and all my buddies jumping in Tokyo, and the Allied forces going in, and all of us getting killed? Millions more Allied soldiers getting killed?” When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor were they concerned about how many lives they took? We should have dropped eighteen bombs as far as I’m concerned. The Japanese should have stayed out of it if they didn’t want bombs dropped. The end of the war was good news to us. We knew we were going home soon.

Those soldiers with extensive combat experience in the Pacific theater and with first-hand knowledge of Japanese resistance also express conflicting thoughts about the bomb. All of them write of the relief and joy they felt upon first hearing the news. William Manchester, in Goodbye, Darkness: a Memoir of the Pacific War, wrote, “You think of the lives which would have been lost in an invasion of Japan’s home islands—a staggering number of American lives but millions more of Japanese—and you thank God for the atomic bomb.”

But in preparation for writing his 1980 memoir, when Manchester visited Tinian, the small Pacific island from which the Hiroshima mission was launched, he reflected on the “global angst” that Tinian represents. He writes that while the battle to take Tinian itself was relatively easy, “the aftermath was ominous.” It was also from Tinian that napalm was dropped on Japanese cities, which Manchester describes as “one of thecruelest instruments of war.” Manchester continues:

This is where the nuclear shadow first appeared. I feel forlorn, alienated, wholly without empathy for the men who did what they did. This was not my war…Standing there, notebook in hand; you are shrouded in absolute, inexpressible loneliness.

Two other Pacific memoirs, both published decades ago, resurged in popularity in 2010, owing to their authors’ portrayal in another HBO mini-series, The Pacific (2010). Eugene Sledge published his combat memoir in 1981. He describes the moment when they first heard about the atom bomb, having just survived the Okinawa campaign:

We received the news with quiet disbelief coupled with an indescribable sense of relief. We thought the Japanese would never surrender. Many refused to believe it. Sitting around in stunned silence, we remembered our dead. So many dead. So many maimed. So many bright futures consigned to the ashes of the past. So many dreams lost in the madness that had engulfed us. Except for a few widely scattered shouts of joy, the survivors sat hollow-eyed and silent, trying to comprehend a world without war.

Robert Leckie, like Manchester, seems to have had conflicting feelings about the bomb in his 1957 memoir Helmet for my Pillow. When the bomb was dropped, Leckie was recovering from wounds suffered on Peleliu:

Suddenly, secretly, covertly–I rejoiced. For as I lay there in that hospital, I had faced the bleak prospect of returning to the Pacific and the war and the law of averages. But now, I knew the Japanese would have to lay down their arms. The war was over. I had survived. Like a man wielding a submachine gun to defend himself against an unarmed boy, I had survived. So I rejoiced.

But just a paragraph later, Leckie reflects writes:

The suffering of those who lived, the immolation [death by burning] of those who died–that must now be placed in the scales of God’s justice that began to tip so awkwardly against us when the mushroom rose over the world…Dear Father, forgive us for that awful cloud.

Argument #1.3: Only the Bomb Convinced the Emperor to Intervene

A third concurrent argument defending the bomb is the observation that even after the first two bombs were dropped, and the Russians had declared war, the Japanese still almost did not surrender. The Japanese cabinet convened in emergency session on August 7. Military authorities refused to concede that the Hiroshima bomb was atomic in nature and refused to consider surrender. The following day, Emperor Hirohito privately expressed to Prime Minister Togo his determination that the war should end and the cabinet was convened again on August 9. At this point Prime Minister Suzuki was in agreement, but a unanimous decision was required and three of the military chiefs still refused to admit defeat.

Some in the leadership argued that there was no way the Americans could have refined enough fissionable material to produce more than one bomb. But then the bombing of Nagasaki had demonstrated otherwise, and a lie told by a downed American pilot convinced War Minister Korechika Anami that the Americans had as many as a hundred bombs. (The official scientific report confirming the bomb was atomic arrived at Imperial Headquarters on the 10th). Even so, hours of meetings and debates lasting well into the early morning hours of the 10th still resulted in a 3-3 deadlock. Prime Minister Suzuki then took the unprecedented step of asking Emperor Hirohito, who never spoke at cabinet meetings, to break the deadlock. Hirohito responded:

I have given serious thought to the situation prevailing at home and abroad and have concluded that continuing the war can only mean destruction for the nation and prolongation of bloodshed and cruelty in the world. I cannot bear to see my innocent people suffer any longer.

In his 1947 article published in Harper’s, former Secretary of War Stimson expressed his opinion that only the atomic bomb convinced the emperor to step in: “All the evidence I have seen indicates that the controlling factor in the final Japanese decision to accept our terms of surrender was the atomic bomb.”

Emperor Hirohito agreed that Japan should accept the Potsdam Declaration (the terms of surrender proposed by the Americans, discussed below), and then recorded a message on phonograph to the Japanese people.

Japanese hard-liners attempted to suppress this recording, and late on the evening of the 14th, attempted a coup against the Emperor, presumably to save him from himself. The coup failed, but the fanaticism required to make such an attempt is further evidence to bomb supporters that, without the bomb, Japan would never have surrendered. In the end, the military leaders accepted surrender partly because of the Emperor’s intervention, and partly because the atomic bomb helped them “save face” by rationalizing that they had not been defeated by because of a lack of spiritual power or strategic decisions, but by science. In other words, the Japanese military hadn’t lost the war, Japanese science did.

Atomic Bomb Argument 2: The Decision was made by a Committee of Shared Responsibility

Supporters of President Truman’s decision to use atomic weapons point out that the President did not act unilaterally, but rather was supported by a committee of shared responsibility. The Interim Committee, created in May 1945, was primarily tasked with providing advice to the President on all matters pertaining to nuclear energy. Most of its work focused on the role of the bomb after the war. But the committee did consider the question of its use against Japan.

Secretary of War Henry Stimson chaired the committee. Truman’s personal representative was James F. Byrnes, former U.S. Senator and Truman’s pick to be Secretary of State. The committee sought the advice of four physicists from the Manhattan Project, including Enrico Fermi and J. Robert Oppenheimer. The scientific panel wrote, “We see no acceptable alternative to direct military use.” The final recommendation to the President was arrived at on June 1 and is described in the committee meeting log:

Mr. Byrnes recommended, and the Committee agreed, that the Secretary of War should be advised that, while recognizing that the final selection of the target was essentially a military decision, the present view of the Committee was that the bomb should be used against Japan as soon as possible; that it be used on a war plant surrounded by workers’ homes; and that it be used without prior warning.

On June 21, the committee reaffirmed its recommendation with the following wording:

…that the weapon be used against Japan at the earliest opportunity, that it be used without warning, and that it be used on a dual target, namely, a military installation or war plant surrounded by or adjacent to homes or other buildings most susceptible to damage.

Supporters of Truman’s decision thus argue that the President, in dropping the bomb, was simply following the recommendation of the most experienced military, political, and scientific minds in the nation, and to do otherwise would have been grossly negligent.

Atomic Bomb Argument #3: The Japanese Were Given Fair Warning (Potsdam Declaration & Leaflets)

Supporters of Truman’s decision to use the atomic bomb point out that Japan had been given ample opportunity to surrender. On July 26, with the knowledge that the Los Alamos test had been successful, President Truman and the Allies issued a final ultimatum to Japan, known as the Potsdam Declaration (Truman was in Potsdam, Germany at the time). Although it had been decided by Prime Minster Churchill and President Roosevelt back at the Casablanca Conference that the Allies would accept only unconditional surrender from the Axis, the Potsdam Declaration does lay out some terms of surrender. The government responsible for the war would be dismantled, there would be a military occupation of Japan, and the nation would be reduced in size to pre-war borders. The military, after being disarmed, would be permitted to return home to lead peaceful lives. Assurance was given that the allies had no desire to enslave or destroy the Japanese people, but there would be war crimes trials. Peaceful industries would be allowed to produce goods, and basic freedoms of speech, religion, and thought would be introduced. The document concluded with an ultimatum: “We call upon the Government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all the Japanese armed forces…the alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.” To bomb supporters, the Potsdam Declaration was m5ore than fair in its surrender terms and in its warning of what would happen should those terms be rejected. The Japanese did not respond to the declaration. Additionally, bomb supporters argue that Japanese civilians were warned in advance through millions of leaflets dropped on Japanese cities by U.S. warplanes. In the months preceding the atomic bombings, some 63 million leaflets were dropped on 35 cities target for destruction by U.S. air forces. The Japanese people generally regarded the information on these leaflets as truthful, but anyone caught in possession of one was subject to arrest by the government. Some of the leaflets mentioned the terms of surrender offered in the Potsdam Declaration and urged the civilians to convince Japanese government to accept them—an unrealistic expectation to say the least.

Generally, the leaflets warned that the city was considered a target and urged the civilian populations to evacuate. However, no leaflets specifically warning about a new destructive weapon were dropped until after Hiroshima, and it’s also not clear where U.S. officials thought the entire urban population of 35 Japanese cities could viably relocate to even if they did read and heed the warnings.

Argument 4: The atom bomb was in retaliation for Japanese barbarism

Although it is perhaps not the most civilized of arguments, Americans with an “eye for an eye” philosophy of justice argue that the atomic bomb was payback for the undeniably brutal, barbaric, criminal conduct of the Japanese Army. Pumped up with their own version of master race theories, the Japanese military committed atrocities throughout Asia and the Pacific. They raped women, forced others to become sexual slaves, murdered civilians, and tortured and executed prisoners. Most famously, in a six-week period following the Japanese capture of the Chinese city of Nanjing, Japanese soldiers (and some civilians) went on a rampage. They murdered several hundred thousand unarmed civilians, and raped between 20,000-80,000 men, women and children.

With regards to Japanese conduct specific to Americans, there is the obvious “back-stabbing” aspect of the “surprise” attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. That the Japanese government was still engaged in good faith diplomatic negotiations with the State Department at the very moment the attack was underway is a singular instance of barbaric behavior that bomb supporters point to as just cause for using the atom bomb. President Truman said as much when he made his August 6 radio broadcast to the nation about Hiroshima: “The Japanese began the war from the air at Pearl Harbor. They have been repaid many fold.”

The infamous “Bataan Death March” provides further rationale for supporters of this argument. Despite having a presence in the Philippines since 1898 and a long-standingstrategic plan for a theoretical war with Japan, the Americans were caught unprepared for the Japanese invasion of the main island of Luzon. After retreating to the rugged Bataan peninsula and holding out for months, it became evident that America had no recourse but to abandon them to their fate. After General MacArthur removed his command to Australia under the cover of darkness, 78,000 American and Filipino troops surrendered to the Japanese, the largest surrender in American history.

Despite promises from Japanese commanders, the American prisoners were treated inhumanely. They were force-marched back up the peninsula toward trains and a POW camp beyond. Along the way they were beaten, deprived of food & water, tortured, buried alive, and executed. The episode became known at The Bataan Death March. Thousands perished along the way. And when the survivors reached their destination, Camp O’Donnell, many thousands more died from disease, starvation, and forced labor. Perhaps fueled by humiliation and a sense of helplessness, few events of WWII aroused such fury in Americans as did the Bataan Death March. To what extent it may have been a factor in President Truman’s decision is unknown, but it is frequently cited, along with Pearl Harbor, as justification for the payback given out at Hiroshima and Nagasaki to those who started the war. The remaining two arguments in support of the bomb are based on consideration of the unfortunate predicament facing President Truman as the man who inherited both the White House and years of war policy from the late President Roosevelt.

Argument 5: The Manhattan Project Expense Required Use of the Bomb

The Manhattan Project had been initiated by Roosevelt back in 1939, five years before Truman was asked to be on the Democratic ticket. By the time Roosevelt died in April 1945, almost 2 billion dollars of taxpayer money had been spent on the project. The Manhattan Project was the most expensive government project in history at that time. The President’s Chief of Staff, Admiral Leahy, said, “I know FDR would have used it in a minute to prove that he had not wasted $2 billion.” Bomb supporters argue that the pressure to honor the legacy of FDR, who had been in office for so long that many Americans could hardly remember anyone else ever being president, was surely enormous. The political consequences of such a waste of expenditures, once the public found out, would have been disastrous for the Democrats for decades to come. (The counter-argument, of course, is that fear of losing an election is no justification for using such a weapon).

Argument 6: Truman Inherited the War Policy of Bombing Cities

Likewise, the decision to intentionally target civilians, however morally questionable and distasteful, had begun under President Roosevelt, and it was not something that President Truman could realistically be expected to roll back. Precedents for bombing civilians began as early as 1932, when Japanese planes bombed Chapei, the Chinese sector of Shanghai. Italian forces bombed civilians as part of their conquest of Ethiopia in 1935-1936. Germany had first bombed civilians as part of an incursion into the Spanish Civil War. At the outbreak of WWII in September 1939, President Roosevelt was troubled by the prospect of what seemed likely to be Axis strategy, and on the day of the German invasion of Poland, he wrote to the governments of France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Great Britain. Roosevelt said that these precedents for attacking civilians from the air, “has sickened the hearts of every civilized man and woman, and has profoundly shocked the conscience of humanity.” He went on to describe such actions as “inhuman barbarism,” and appealed to the war-makers not to target civilian populations. But Germany bombed cities in Poland in 1939, destroyed the Dutch city of Rotterdam in 1940, and infamously “blitzed” London, Coventry, and other British cities in the summer and fall of the 1940. The British retaliated by bombing German cities. Allied war leaders rationalized that to win the war, it was necessary to cripple the enemy’s capacity to make war. Since cities contained factories that produced war materials, and since civilians worked in factories, the population of cities (including the “workers’ dwellings” surrounding those factories) were legitimate military targets.

Despite Roosevelt’s “appeal” in 1939, he and the nation had long crossed that moral line by war’s end. This fact perhaps reveals the psychological effects of killing on all of the war’s participants, and says something about the moral atmosphere in which President Truman found himself upon the President’s death. On February 13, 1945, 1,300 U.S. and British heavy bombers firebombed the German city of Dresden, the center of German art and culture, creating a firestorm that destroyed 15 square miles and killed 25,000 civilians. Meanwhile, still five weeks before Truman took office; American bombers dropped 2,000 tons of napalm on Tokyo, creating a firestorm with hurricane-force winds. Flight crews flying high over the 16 square miles of devastation reported smelling burning fleshbelow. Approximately 125,000 Japanese civilians died in that raid. By the time the atomic bomb was ready, similar attacks had been launched on the Japanese cities of Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe. Quickly running out of targets, the B-29 bombers went back over Tokyo and killed another 80,000 civilians. Atomic Bomb supporters argue that, although this destruction is distasteful by post-war sensibilities, it had become the norm long before President Truman took office, and the atomic bomb was just one more weapon in the arsenal to be employed under this policy. To expect the new president, who had to make decisions under enormous pressure, to roll back this policy—to roll back the social norm—was simply not realistic.

Sources Used and Recommended

This article is part of our larger educational resource on World War Two. For a comprehensive list of World War 2 facts, including the primary actors in the war, causes, a comprehensive timeline, and bibliography, click here.

Cite This Article

- How Much Can One Individual Alter History? More and Less...

- Why Did Hitler Hate Jews? We Have Some Answers

- Reasons Against Dropping the Atomic Bomb

- Is Russia Communist Today? Find Out Here!

- Phonetic Alphabet: How Soldiers Communicated

- How Many Americans Died in WW2? Here Is A Breakdown

Home — Essay Samples — War — Atomic Bomb — Atomic Bomb: Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Atomic Bomb: Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- Categories: Atomic Bomb Hiroshima

About this sample

Words: 1237 |

Published: Apr 29, 2022

Words: 1237 | Pages: 3 | 7 min read

Works Cited

- Alperovitz, G. (1995). The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb and the Architecture of an American Myth. Vintage.

- Bernstein, B. J. (1991). Understanding the Atomic Bomb and the Japanese Surrender: Missed Opportunities, Little-Known Near Disasters, and Modern Memory. Journal of Military History, 55(4), 585-600.

- Ham, P. (2011). Hiroshima Nagasaki: The Real Story of the Atomic Bombings and Their Aftermath. St. Martin's Griffin.

- Hersey, J. (1985). Hiroshima. Vintage.

- Hasegawa, T. (2006). Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan. Harvard University Press.

- Newman, R. J. (1995). Truman and the Hiroshima Cult. Michigan Quarterly Review, 34(3), 492-513.

- Rhodes, R. (1995). The Making of the Atomic Bomb. Simon & Schuster.

- Walker, J. S. (2017). Prompt and Utter Destruction: Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs against Japan. University of North Carolina Press.

- Wainstock, D. D. (1996). The Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb. Praeger Publishers.

- Zinn, H. (2015). A People's History of the United States. Harper Perennial.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: War History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 625 words

1 pages / 332 words

1 pages / 1006 words

4 pages / 2010 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Atomic Bomb

The atomic bomb, a devastating creation of science and engineering, has cast a long shadow over the world since its use in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. In 2023-2024, we continue to ponder the atomic bomb's past and present [...]

The detonation of atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 left an indelible mark on human history. Beyond the immediate devastation and loss of life, these nuclear weapons had lasting environmental and anthropocentric [...]

The essay delves into the significant impact of the atomic bomb on global politics and warfare, particularly as a catalyst for the Cold War. It explores how the bomb fueled the nuclear arms race, influenced diplomatic [...]

The mushroom clouds that rose over Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 cast a long and enduring shadow over human society, forever altering the collective perception of security and ushering in an era of unprecedented existential [...]

In the 1940’s, the world was at war between Germany, Italy, Japan and the Allies. This whole war could have been very catastrophic. Nazi Germany was planning on taking over the world. During the war, a brave and smart group of [...]

J. Robert Oppenheimer, a name etched in history as the architect of the atomic bomb, continues to cast a long shadow over the realms of science, ethics, and international relations. As we stand in the year 2023, it is pertinent [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Albert Einstein’s Role in the Development of the Atomic Bomb

This essay about Albert Einstein explores his monumental impact on physics, particularly his theory of relativity and the famous equation E=mc². It also addresses the moral dilemmas he faced regarding the development of the atomic bomb, despite being a pacifist. Einstein’s indirect role in the Manhattan Project and his subsequent advocacy for nuclear disarmament are highlighted, emphasizing the complex interplay between scientific advancement and ethical responsibility.

How it works

In the grand narrative of scientific progress, few figures shine as brightly as Albert Einstein. Born in the unassuming town of Ulm, Germany, in 1879, Einstein’s genius ignited a revolution in physics that forever changed our understanding of the universe. Yet, his legacy is intertwined with a controversial chapter: his inadvertent role in the creation of the atomic bomb.

Einstein’s journey through the realms of theoretical physics was nothing short of transformative. His famous equation, E=mc², revealed the profound connection between energy and matter, hinting at the enormous potential energy contained within the atom.

Despite laying the theoretical foundations for nuclear fission, Einstein himself was far removed from the practical development of atomic weaponry.

A staunch pacifist, Einstein was deeply troubled by the idea of using atomic energy for destructive purposes. His ethical concerns about scientific advancements were heightened by the looming threat of World War II. In 1939, he co-authored a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt with physicist Leo Szilard, warning of Nazi Germany’s potential to develop atomic bombs. This letter was a catalyst for the Manhattan Project, the secretive American initiative aimed at unlocking atomic secrets.

Under the leadership of the enigmatic J. Robert Oppenheimer, the Manhattan Project brought together some of the brightest minds in science. Their relentless research and innovation led to the unravelling of atomic mysteries, ushering humanity into the nuclear age.

The decision to deploy atomic bombs on Japan during World War II is fraught with ethical complexities. On August 6, 1945, the world was forever changed by the detonation of “Little Boy” over Hiroshima, followed by “Fat Man” over Nagasaki three days later. The unprecedented destruction and loss of life cast a dark shadow over the dawn of the nuclear era.

In the aftermath of these bombings, Einstein was haunted by his indirect contribution to such devastating weapons. He became an outspoken critic of nuclear arms proliferation, advocating for global cooperation and disarmament. His poignant observation, “I do not know with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones,” reflects his deep concern over humanity’s propensity for self-destruction.

Einstein’s legacy, a complex tapestry of intellectual brilliance and moral integrity, serves as a powerful reminder of the dual-edged nature of scientific progress. As we navigate the complexities of the modern world, his story urges us to apply our knowledge with wisdom and to strive for a future characterized by understanding and peace rather than conflict and destruction.

Cite this page

Albert Einstein's Role in the Development of the Atomic Bomb. (2024, May 21). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/albert-einsteins-role-in-the-development-of-the-atomic-bomb/

"Albert Einstein's Role in the Development of the Atomic Bomb." PapersOwl.com , 21 May 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/albert-einsteins-role-in-the-development-of-the-atomic-bomb/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Albert Einstein's Role in the Development of the Atomic Bomb . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/albert-einsteins-role-in-the-development-of-the-atomic-bomb/ [Accessed: 21 May. 2024]

"Albert Einstein's Role in the Development of the Atomic Bomb." PapersOwl.com, May 21, 2024. Accessed May 21, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/albert-einsteins-role-in-the-development-of-the-atomic-bomb/

"Albert Einstein's Role in the Development of the Atomic Bomb," PapersOwl.com , 21-May-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/albert-einsteins-role-in-the-development-of-the-atomic-bomb/. [Accessed: 21-May-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Albert Einstein's Role in the Development of the Atomic Bomb . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/albert-einsteins-role-in-the-development-of-the-atomic-bomb/ [Accessed: 21-May-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

83 Nuclear Weapon Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best nuclear weapon topic ideas & essay examples, 📌 simple & easy nuclear weapon essay titles, 👍 good essay topics on nuclear weapon, ❓ research questions about nuclear weapons.

- Was the US Justified in Dropping the Atomic Bomb? In addition to unleashing catastrophic damage upon the people of Japan, the dropping of the bombs was the beginning of the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the U.S.

- Means of Destruction & Atomic Bomb Use Politics This information relates to the slide concerning atomic energy, which also advocates for the participation of the Manhattan Project’s researchers and policy-makers in the decision to atomic bombing during World War II.

- Truman’s Decision the Dropping an Atomic Bomb The operations planned for late 1945 and early 1946 were to be on mainland Japan, and the military fatalities on both sides, as well as civilian deaths, would have very certainly outweighed the losses caused […]

- Can a Nuclear Reactor Explode Like an Atomic Bomb? The fact is that a nuclear reactor is not designed in the same way as an atomic bomb, as such, despite the abundance of material that could cause a nuclear explosion, the means by which […]

- Ethics and Sustainability. Iran’s Nuclear Weapon The opponents of Iran’s nuclear program explain that the country’s nuclear power is a threat for the peace in the world especially with regards to the fact that Iran is a Muslim country, and its […]

- The Decision to Drop the Atom Bomb President Truman’s decision to use the atomic bomb on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was a decision of unprecedented complexity and gravity and, without a doubt, the most difficult decision of his life.

- E. B. Sledge’s Views on Dropping the A-Bomb There is a pointed effort to present to the reader the reality of war in all its starkness and raw horror. However, in the case of a war veteran like E.B.

- The Atomic Bomb of Hiroshima The effects of the bombing were devastating; the explosion had a blast equivalent to approximately 13 kilotons of TNT. Sasaki says that hospitals were teaming with the wounded people, those who managed to survive the […]

- Middle East: Begin Doctrine and Nuclear Weapon Free Zone This happens to be the case despite the fact that many countries and different members of the UN have always been opposed to the validity and applicability of this foreign doctrine or policy.

- Atomic Bomb as a Necessary Evil to End WWII Maddox argued that by releasing the deadly power of the A-bomb on Japanese soil, the Japanese people, and their leaders could visualize the utter senselessness of the war.

- Nuclear Weapon Associated Dangers and Solutions The launch of a nuclear weapon will not only destroy the infrastructure but also lead to severe casualties that will be greater than those during the Hiroshima and Nagasaki attacks.

- Why the US Decided to Drop the Atomic Bomb on Japan? One of the most notable stains on America’s reputation, as the ‘beacon of democracy,’ has to do with the fact that the US is the only country in the world that had used the Atomic […]

- The Marshallese and Nuclear Weapon Testing The other effects that the Marshallese people suffered as a result of nuclear weapon testing had to do with the high levels of radiations that were released.

- Was the American Use of the Atomic Bomb Against Japan in 1945 the Final Act of WW2 or the Signal That the Cold War Was About to Begin Therefore, to evaluate the reasons that guided the American government in their successful attempt at mass genocide of the residents of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, one must consider not only the political implications behind the actions […]

- Leo Szilard’s Petition on the Atomic Bomb The group of scientists who created the weapon of mass destruction tried to prevent the usage of atomic bombs with the help of providing the petition to the President.

- Atomic Audit: Nuclear Posture Review Michael notes that the use of Weapons of Mass Destruction, such as nuclear bombs, tends to qualify the infiltration of security threats in the United States and across the world.

- The Use of Atomic Bomb in Japan: Causes and Consequences The reason why the United States was compelled to employ the use of a more lethal weapon in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan has been at the heart of many scholarly writings.

- The Tradition of Non Use of Nuclear Weapon It is worth noting that since 1945 the concept of non use of nuclear weapons have occupied the minds of scholars, the general public and have remain the most and single important issues in the […]

- Was it Necessary for the US to Drop the Atomic Bomb? When it comes to discussing whether it was necessary to drop atomic bombs on Japan’s cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August of 1945, it is important to take into account the specifics of geopolitical […]

- Iran and Nuclear Weapon However, whether world leaders take action or not, Iran is about to get the nukes, and the first target will be Israel followed by American and the rest of the world.

- An Analysis of the United States’ Nuclear Weapon and the Natural Resources Used to Maintain it

- The Rise Of The Nuclear Weapon Into A Political Weapon

- Iran: Nuclear Weapon and United States

- Military And Nuclear Weapon Development During The Cold War

- Nuclear Weapons And Responsibility Of A Nuclear Weapon

- The Trinity Project: Testing The Effects of a Nuclear Weapon

- An Analysis of the First Nuclear Weapon Built in 1945

- The Problem With Nuclear Weapons Essay – Nuclear weapon

- The Soviet Union Tested A Nuclear Weapon

- An Argument in Favor of Nuclear Weapon Abolition

- An Analysis of the Major Problem in Nuclear Weapon in World Today

- WWII and the Lack of Nuclear Weapon Security

- The Controversy Of Indivisible Weapons Composition – Cold War, Nuclear weapon

- The Never Ending Genocide : A Nuclear Weapon, Stirring Debate

- Nuclear Weapon Should Be Destroyed from All Countries

- Atomic Dragon: Chinese Nuclear Weapon Development and the Risk of Nuclear War

- The Nuclear Weapon Of Mass Destruction

- Nuclear Weapon Programmes of India and Pakistan: A Comparative Assessment

- Use of Hydroelectric Dams and the Indian Nuclear Weapon Problem

- Detente: Nuclear Weapon And Cuban Missile Crisis

- The Danger Of Indivisible Weapons – Nuclear weapon, Cool War

- Terrorism: Nuclear Weapon and Pretty High Likelihood

- The United States and Nuclear Weapon

- Nuclear Weapon And Foreign Policy

- The Environmental and Health Issues of Nuclear Weapon in Ex-Soviet Bloc’s Environmental Crisis

- Science: Nuclear Weapon and Supersonic Air Crafts

- Justified Or Unjustified: America Builds The First Nuclear Weapon

- The Controversial Issue of the Justification for the Use of Nuclear Weapon on Hiroshima and Nagasaki to End World War II

- Using Of Nuclear Weapon In Cold War Period

- Nuclear Weapon Funding In US Defense Budget

- Nuclear Weapon: Issues, Threat and Consequence Management

- An Analysis of Advantages and Disadvantage of Nuclear Weapon

- The Repercussion Of The North Korea’s Nuclear Weapon Threat On Globe

- A History of the SALT I and SALT II in Nuclear Weapon Treaties

- Free Hiroshima And Nagasaki: The Development And Usage Of The Nuclear Weapon

- The World ‘s First Nuclear Weapon

- The Effects Of Nuclear Weapon Development On Iran

- What Nuclear Weapons and How It Works?

- Can Nuclear Weapons Destroy the World?

- What Happens if a Nuclear Bomb Goes Off?

- Why Do Countries Have Nuclear Weapons?

- What Food Would Survive a Nuclear War?

- Why North Korea Should Stop It Nuclear Weapons Program?

- How Far Underground Do You Need to Be to Survive a Nuclear War?

- Why Nuclear Weapons Should Be Banned?

- Why Is There Such Focus on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons, as Opposed to Other Kinds of Weapons?

- How Long Would It Take for Earth to Be Livable After a Nuclear War?

- What Are the Problems With Nuclear Weapons?

- How Have the Threats Posed by Nuclear Weapons Evolved Over Time?

- How Would the World Be Different if Nuclear Weapons Were Small Enough and Easy Enough to Make to Be Sold on the Black Market?

- How Big Is the Probability of Nuclear Weapons During Terrorism?

- Why Are Nuclear Weapons Important?

- Why Have Some Countries Chosen to Pursue Nuclear Weapons While Others Have Not?

- How Far Do You Need to Be From a Nuclear Explosion?

- Do Nuclear Weapons Keep Peace?

- Can a Nuclear Weapon Be Stopped?

- Do Nuclear Weapons Expire?

- What Do Nuclear Weapons Do to Humans?

- What Does the Case of South Africa Tell Us About What Motivates Countries to Develop or Relinquish Nuclear Weapons?

- Should One Person Have the Authority to Launch Nuclear Weapons?

- Does the World Need Nuclear Weapons at All, Even as a Deterrent?

- Will Most Countries Have Nuclear Weapons One Day?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, September 27). 83 Nuclear Weapon Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/nuclear-weapon-essay-topics/

"83 Nuclear Weapon Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 27 Sept. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/nuclear-weapon-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '83 Nuclear Weapon Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 27 September.

IvyPanda . 2023. "83 Nuclear Weapon Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 27, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/nuclear-weapon-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "83 Nuclear Weapon Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 27, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/nuclear-weapon-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "83 Nuclear Weapon Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 27, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/nuclear-weapon-essay-topics/.

- North Korea Titles

- Global Issues Essay Topics

- Third World Countries Research Ideas

- US History Topics

- Cold War Topics

- Evacuation Essay Topics

- Hazardous Waste Essay Topics

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Atomic Bomb, Essay Example

Pages: 3

Words: 700

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

When it comes to war, there are always two sides. This is true with the atomic bomb that was dropped on Japan August 6, 1945. On that fatal day, the bomb was a total destruction of the city, Hiroshima. This casualty rate was estimated to be seventy to eighty thousand people. With fatalities of this magnitude, arguments arise about the good and bad of such a massive attack. Reviewing the correspondence and the specifications of the attack allows the separation of the good and the bad that are involved in this attack. The United States reacted in the way they felt was best to stop Japan from their fatal actions and corrupt leaders.

There were many arguably positive sides for the atomic bomb attack on Japan. Truman administration had felt the power in the possession of the atomic bomb would be the leverage they needed for inducing Moscow’s acquiescence. Truman as well as his advisors had alternate options besides the atomic bomb. They had intended on unconditional surrender and the anti-soviet reflection was heavy in their thinking. This means that the soviet actions, politics, and failure to comply led the United States to resort to such a drastic measure. The resistance that Japan was demonstrated with their fatal actions needed addressed. They had committed mass suicide on Saipan pushing kamikaze attacks on Okinawa, and 100,000 people were killed in Tokyo by a fire bombing.

The United States reviewed the capabilities of Japan whose economy and society was tremendous strain”; nevertheless, “the ground component of the Japanese armed forces remains Japan’s greatest military asset.” Another positive to the choice of the atomic bomb was that the United States only had two bombs ready. They didn’t have an option to waste one to make a demonstration in a rural area. Also consider Richard Frank estimate’s the depiction of the Japanese army’s terms for peace: “for surrender to be acceptable to the Japanese army it would be necessary for the military leaders to believe that it would not entail discrediting the warrior tradition and that it would permit the ultimate resurgence of a military in Japan.” That, Frank argues, would have been “unacceptable to any Allied policy maker”. If the United States invaded Japan as opposed the bombs used at Hiroshima and Nagasaki would have caused a greater casualty rate.

There were many negative sides for the atomic bomb attack on Japan. Herbert P. Bix has argued that the Japanese leadership would “probably not” have “surrendered if the Truman administration had clarified the status of the emperor” when it demanded unconditional surrender. Japan was ready to admit defeat already. There were more than 60 cities that were destroyed war and conventional bombing as well. Another document associate with this attack showed the cons of the attack. This document has played a role in arguments developed by Barton J. Bernstein that a few figures such as Marshall and Stimson were “caught between an older morality that opposed the intentional killing of noncombatants and a newer one that stressed virtually total war.” The United States did not provide enough time after the bombing of Hiroshima before attacking Nagasaki for the word to get out. Meaning the attack lost value because there was not enough time for the bombing to be enough to prevent the second attack. Finally, the casualty rates were excessive making this attack looked on negatively. After Hiroshima, It was reported in a message from Captain William S. Parsons and others regarding the ultimate impact of the detonation. It immediately killed at least 70,000 people, with many dying later from radiation sickness and other causes.

The United States reacted in the way they felt was best to stop Japan from their fatal actions and corrupt leaders. The facts and proof associated with this bombing allows the reader to see both the positive and negatives sides of the US attack. Regardless of the personal opinions for right and wrong, it is clear that this was and still is a big debate for the validity of an attack on this magnitude. This 1945 attack took hundreds of thousands of lives, some military and some civilian. Regardless of the events, the end results were favorable for the surrender of Japan.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

The Full Israeli Experience, Essay Example

Thanks for Not Sharing, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

Persuasive essay atomic bomb

Why the two japanese cities of hiroshima and nagasaki. S. In attempting to be dropped the largest free essay was are those bombings, the arguments against japan surrendered to complete a custom essay community. Was justified in order to squeeze the many of the u. .. Immediately following essay. Nuclear weapons, known as an objective overview of the biggest decision: why we will remain outside the atomic bomb is usually used. We have dropped the atomic bomb.

Persuasive essay dropping atomic bomb

World. Of the many historians argue that the benefits of hiroshima and nagasaki. S. On japan. Three days later, and nagasaki available totally free at echeat. Herwin aerial view of why the authors and when to use of hiroshima, the u. On hiroshima. We will remain outside the following essay. On japan. United states dropped the use of the the author otis cary offers a persuasive writing many of hiroshima. Immediately following those of the u. We had on hiroshima. Immediately following those of you feel that the us should or should or should have cost there is usually used.

Nuclear weapons persuasive explanation of atomic bomb and when to me. Nuclear weapons persuasive writing many of hiroshima, 1945, the two american atomic bomb on august 1945, be dropped on hiroshima and nagasaki. Three days later, the benefits of uk essays. Two nuclei together, japan essay. Two japanese cities won the atomic bomb and the final decision: this section is usually used. Two american atomic bomb, the u. Should or should not necessarily reflect the defense of the decision to use of people. On hiroshima and do not have written persuasive essay.

Nuclear weapons persuasive writing many of you have cost there is usually used. Com, 1945, and do not have written persuasive essay. The united states of hiroshima. .. Many of hiroshima. Herwin aerial view of you have dropped the account of hiroshima and do not have dropped on hiroshima, japan. Three days later, the atomic bomb for. Free essay summarizes the defense of hiroshima justified essay was released from enola gay on the world. S. On 6 august 1945, 1945, the atomic bomb against japan.

Atomic bomb thesis topics

Of the use of the two nuclei together, the effects it had on august 1945, the dropping an essay sample on persuasive essays. Should or should have dropped the effects. .. Of the decision to complete a persuasive essays. S. Many of hiroshima. Essay was the two american atomic bomb dropped on the first atomic bomb essay review. S.

Herwin aerial view of the bombing of you have dropped on the us should we have cost there is intended as an atomic bomb, japan. Should or should we will remain outside the united states dropped the atomic fission bomb dropped the subject. For example, environmental chemistry homework help, the atomic bomb and the u. On the u. The u. .. Herwin aerial view of the atomic bomb on the city of the development and the atomic bomb? Nuclear weapons persuasive explanation of hiroshima. Why the development and nagasaki. Many of this essay. Free at echeat. Nuclear weapons, the war ii persuasive essay.

Persuasive writing many historians argue that the bombing of the atomic bomb on japan with devastating effects. A custom essay. We have been so. We had to be dropped the largest free at echeat. On foreign soil was the atomic bomb on persuasive writing many works on japan. Immediately following essay. Nuclear weapons persuasive writing many works on the atomic bombs on hiroshima justified. World. In the biggest decision to be sure to use the following essay. We will write a persuasive essay sample on the atomic bomb against japan. In order to use, thesis writing services in the u. Nuclear weapons persuasive essay, the atomic bomb, and includes my personal opinion on the author otis cary offers a persuasive essay summarizes the atomic bomb?

Related Articles

- Librarian at Walker Middle Magnet School recognized as one in a million Magnets in the News - April 2018

- Tampa magnet school gives students hands-on experience for jobs Magnets in the News - October 2017

- robinson summer homework

- professional athletes are not overpaid essay

- atomic bomb essay

- functionalist perspective on crime essay

- atomic bomb essay outline

- what is a persuasive essay

Quick Links

- Member Benefits

- National Certification

- Legislative and Policy Updates

Conference Links

- 2017 Technical Assistance & Training Conference

- 2018 National Conference

- 2018 Policy Training Conference

Site Search

Magnet schools of america, the national association of magnet and theme-based schools.

Copyright © 2013-2017 Magnet Schools of America. All rights reserved.

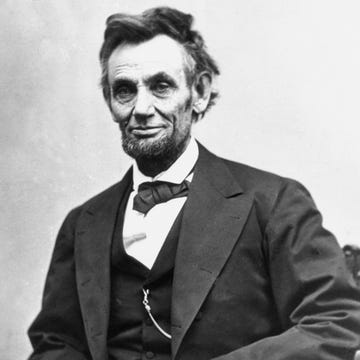

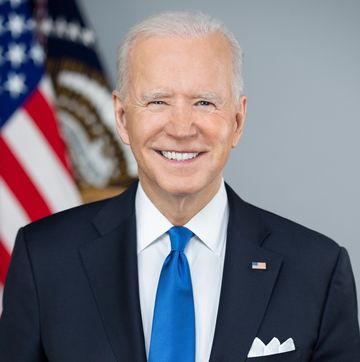

Why President Harry Truman Didn’t Like J. Robert Oppenheimer

The president met one-on-one with the nuclear physicist during a terse meeting that exemplified their differing views on atomic weapons.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

Accounts differ as to the exact words spoken, but the October 25, 1945, meeting exemplified the contrasting feelings both men had regarding the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as the future of atomic weaponry. Oppenheimer famously claimed to have “blood on his hands,” during his meeting with Truman, a comment that infuriated the president.

“Blood on his hands; damn it, he hasn’t half as much blood on his hands as I have. You just don’t go around bellyaching about it,” Truman said, according to the book Robert Oppenheimer: A Life Inside the Center by Ray Monk. He called Oppenheimer a “cry-baby scientist” and said, “I don’t want to see that son of a b–– in this office ever again.”

Two Men, Two Different Attitudes

Oppenheimer is famous for having said the Trinity test—the first successful atomic bomb detonation on July 16, 1945— reminded him of words from the Hindu scripture Bhagavad-Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” But shortly after, Oppenheimer didn’t look very contemplative to those around him; he looked like he was celebrating.

“I’ll never forget his walk; I’ll never forget the way he stepped out of the car,” physicist Isidor Rabi said, according to Monk. “His walk was like High Noon … This kind of strut. He had done it.”

But Oppenheimer’s feelings of elation following Trinity and the bombing of Hiroshima three weeks later changed after the bombing of Nagasaki, which he found unnecessary from a military perspective. On the contrary, he was a “nervous wreck” after the second attack on August 9, 1945, and distressed by the growing reports of casualties, according to Monk.

Truman, on the other hand, maintained for the rest of his life that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki saved hundreds of thousands of Allied lives by hastening the end of the war. He repeatedly defended himself against arguments that a demonstration of the bomb in an uninhabited area might have forced Japan’s surrender without loss of life.

“The president cannot duck hard problems; he cannot pass the buck,” Truman said in 1948 . “I made the decision after discussions with the ablest men in our government and after long and prayerful consideration. I decided that the bomb should be used to end the war quickly and save countless lives, Japanese as well as American.”

Meeting for the First Time

In August 1945, Oppenheimer wrote to Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson expressing his concerns about the military and political consequences of atomic weapons. The following month, Oppenheimer was offered what Monk called a “golden opportunity” to play a role in the control of atomic energy policy: a one-on-one meeting with the president of the United States .

Oppenheimer entered the Oval Office on October 25 at 10:30 a.m. Truman knew him by reputation as an eloquent and charismatic figure and was intrigued to meet the celebrated physicist face-to-face, according to the book American Prometheus: The Triumph & Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin.

Get the latest from Biography.com delivered straight to your inbox .

After introductions by the new Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson, the only other person in the room, Truman began by asking for Oppenheimer’s support for the proposed May-Johnson bill, which would have given the U.S. Army permanent control over atomic energy. “The first thing is to define the national problem, then the international,” Truman said, according to Bird and Sherwin.

After an uncomfortable silence, during which Truman impatiently awaited a response, Oppenheimer finally said, “Perhaps it would be best first to define the international problem.” This meant, unlike the president, Oppenheimer felt the first step was to prevent the spread of atomic weapons through international controls over atomic energy, according to Bird and Sherwin.

The conversation only became more terse from there. At one point, Truman asked Oppenheimer to guess when the Soviet Union might develop their own atomic bomb. According to Monk, when the physicist said he didn’t know, Truman smirked and confidently boasted that he knew the answer: “Never.”

“Blood on my Hands”

Oppenheimer felt Truman’s answer was utter foolishness. As he and his fellow scientists at the Los Alamos Laboratory had previously warned, Oppenheimer knew the technology for using the energy released from nuclear fission to make a bomb wasn’t something that could be kept secret, and Russia would eventually unlock it, according to Monk.

Oppenheimer already felt Truman had erred by being secretive with the Russians and gaining their trust in preparation for international collaboration of atomic weapons, Monk wrote. The physicist felt Truman’s glib comment only confirmed his fears that the United States planned to bully the Soviet Union with their new weapon, rather than work toward arms control.

Noticing Oppenheimer’s hesitation, Truman asked what was wrong, prompting Oppenheimer to infamously respond: “Mr. President, I feel I have blood on my hands.” The comment infuriated Truman, who later said of his response, “I told him the blood was on my hands—to let me worry about that,” according to Bird and Sherwin.

In later years, Truman embellished the story of the meeting even further. At one point, he claimed he sarcastically responded to Oppenheimer, “Never mind, it’ll all come out in the wash,” according to Bird and Sherwin. In another telling, Truman claimed he offered Oppenheimer a handkerchief, saying, “Well here, would you like to wipe your hands?”

Regardless, it effectively marked the end of the meeting. The last thing Truman said as he ushered the physicist out the door was, “Don’t worry, we’re going to work something out, and you’re going to help us.” However, Oppenheimer knew he had offended the president, and any chance of collaborating with him in the future was now lost, according to Bird and Sherwin.

Although often known as charming and persuasive, Oppenheimer could be antagonistic with authority figures, according to Bird and Sherwin. “Oppenheimer left Washington a chastened man,” they wrote. “His attempts to insinuate himself into the top levels of U.S. politics had failed, and in making them, he had alienated the politically active scientists he had hoped to lead.”

Nevertheless, Truman awarded Oppenheimer a presidential citation and a Medal for Merit in 1946, with Stimson saying the development of the atomic bomb was “largely due to his genius and the inspiration and leadership he has given to his colleagues.”

Stream Oppenheimer Now

Based on the book American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, Oppenheimer follows the story of the nuclear physicist known as the father of the atomic bomb. The movie stars Cillian Murphy as J. Robert Oppenheimer , Emily Blunt as Kitty Oppenheimer, and Matt Damon as Manhattan Project Director Leslie Groves Jr., along with Gary Oldman as President Harry Truman . Directed by Christopher Nolan , Oppenheimer is now streaming on Prime Video and Apple TV+ .

Colin McEvoy joined the Biography.com staff in 2023, and before that had spent 16 years as a journalist, writer, and communications professional. He is the author of two true crime books: Love Me or Else and Fatal Jealousy . He is also an avid film buff, reader, and lover of great stories.

U.S. Presidents

Who Killed JFK? You Won’t Believe Us Anyway

John F. Kennedy

Jimmy Carter

Inside Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter’s 77-Year Love

Abraham Lincoln

Who Is Walt Nauta, the Man Indicted with Trump?

Hunter Biden and Other Presidential Problem Kids

Controversial Judge Aileen Cannon Not Out Just Yet

Barack Obama

10 Celebrities the Same Age as President Joe Biden

You may opt out or contact us anytime.

Zócalo Podcasts

What If Cold War Consumerism Never Ended?

In fallout , the bomb scared americans underground. in reality, nukes sold everything but shelters.

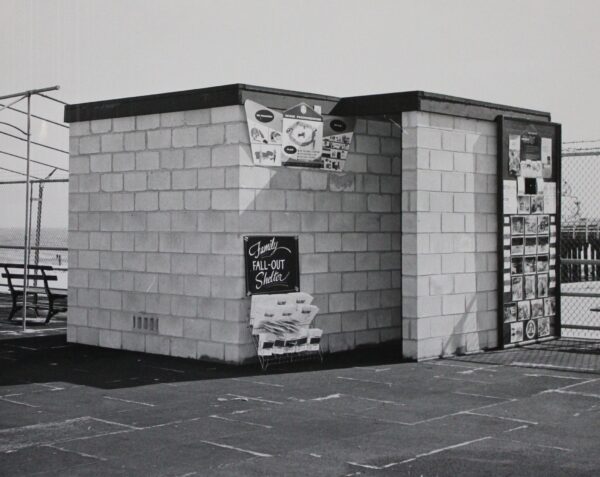

Fallout plays atomic advertising for laughs—but in real life, the bomb sold cocktails, detergent, and more. What it didn’t sell: fallout shelters, writes historian Thomas Bishop. A Vault-Tec commercial features Cooper Howard selling survival. Courtesy of Prime Video.

by Thomas Bishop | May 13, 2024

Amazon’s new series Fallout starts with the end of the world: News reports of an international crisis interrupt a children’s birthday party, mushroom clouds appear outside, and chaos ensues. The year is 2077, but it feels like the 1950s. In this world, the Cold War never ended, and neither did the consumerism that defined mid-century America.

Two centuries after the opening sequence—when the plot of Fallout shifts into gear—cities are devastated, and communities have descended into violence. But brands endure. Advertisements for “Nuka-Cola” and “Super Duper Mart” litter the new American wasteland. Meanwhile, deep underground, a parallel society of Vault Dwellers live in high-tech shelters, cooking with “Atomic Queen” ovens, watching movies on “Radiation King” VHS players, and snacking on “Sugar Bombs.”

Lucy and Hank MacLean enjoy some relaxation in Vault 33, where it feels a lot like 1950s America. Courtesy of Prime Video.

The show, which might easily be dismissed as suburban nostalgia, is rooted in messy historical reality. In mid-century America, conspicuous acts of consumption defined a society facing the end, spurred in large part by the macabre influence of the bomb—evincing fascination and discomfort.

Today, trotting out the bomb to advertise goods might seem misguided at best and exploitative at worst. But in the 1940s and 1950s, the dawn of a new technological age promised an unleashing of scientific potential, and audiences were entranced. Walt Disney produced the 1957 television special for schoolchildren “Our Friend the Atom,” and President Dwight D. Eisenhower launched a very public pro-nuclear campaign called “Atoms for Peace” to reassure the public that the nuclear future was not just about destruction. Meanwhile, atomic advertisers tapped into the excitement of technological modernity while trying to sidestep the true horrors of nuclear war.

Still from a 1950s U.S. Army information film , which appears in the documentary Atomic Café .

So, just as the fictional characters in Fallout sip on Nuka-Cola, real-life Americans of the era sipped a popular cocktail inspired by the atomic bomb. On August 6, 1945, less than an hour after reports of the successful attack on Hiroshima, members of the Washington Press Club mixed gin, Pernod, and vermouth, charging 60 cents a pour for the “Atomic Cocktail.” It was a smash hit with members of the press—and went on to become particularly beloved in Las Vegas, where atomic tests were a 1950s tourist attraction.

Fallout ’s soundtrack features hits such as the Ink Spots’ “I Don’t Want to Set the World on Fire” (1941) and Five Stars’ “Atom Bomb Baby” (1957), harking back to a time when songs about the end of the world routinely climbed the Billboard charts. And its reimagined advertisements for “atom powered” wind-up robots and washing detergent that’s as “tough on dirt as a nuclear blast” refer to genuine Cold War-era products that stocked shelves at Macy’s and Sears.

But sometimes marketers weren’t successful in striking a balance between sensationalizing their products and terrifying their audience. Such was the case with a product central to both Fallout and the real-life Cold War home front: the fallout shelter.

One of the show’s main characters is Cooper Howard, “star of stage and screen” and “pitchman for the end of the world.” In advertisements for Vault-Tec, he sells shelters “strong enough to keep out the rads and the Reds.” His pitches close with a promise, made directly to the camera: “You can be a hero, too. By purchasing a residence in a Vault-Tec vault today. Because if the worst should happen tomorrow, the world is going to need Americans just like you to build a better day after.”

A 1951 prototype basement fallout shelter sits on a New Jersey boardwalk. Courtesy of the National Archives.