Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- The Virtues and Downsides of Online Dating

30% of U.S. adults say they have used a dating site or app. A majority of online daters say their overall experience was positive, but many users – particularly younger women – report being harassed or sent explicit messages on these platforms

Table of contents.

- 1. Americans’ personal experiences with online dating

- 2. Users of online dating platforms experience both positive – and negative – aspects of courtship on the web

- 3. Americans’ opinions about the online dating environment

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

How we did this

Pew Research Center has long studied the changing nature of romantic relationships and the role of digital technology in how people meet potential partners and navigate web-based dating platforms. This particular report focuses on the patterns, experiences and attitudes related to online dating in America. These findings are based on a survey conducted Oct. 16 to 28, 2019, among 4,860 U.S. adults. This includes those who took part as members of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses, as well as respondents from the Ipsos KnowledgePanel who indicated that they identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual (LGB). The margin of sampling error for the full sample is plus or minus 2.1 percentage points.

Recruiting ATP panelists by phone or mail ensures that nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. This gives us confidence that any sample can represent the whole U.S. adult population (see our Methods 101 explainer on random sampling). To further ensure that each ATP survey reflects a balanced cross-section of the nation, the data are weighted to match the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories.

For more, see the report’s methodology about the project. You can also find the questions asked, and the answers the public provided in this topline .

From personal ads that began appearing in publications around the 1700s to videocassette dating services that sprang up decades ago, the platforms people use to seek out romantic partners have evolved throughout history. This evolution has continued with the rise of online dating sites and mobile apps.

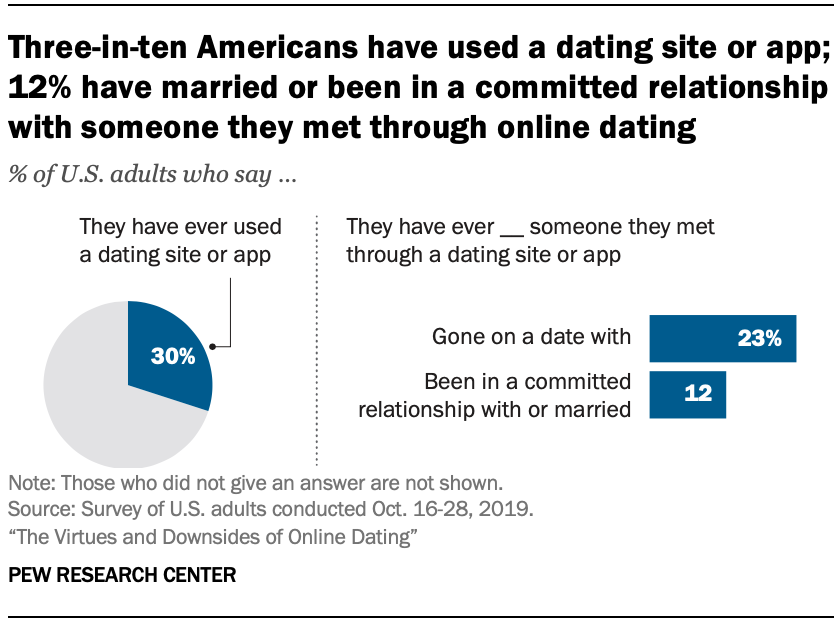

Today, three-in-ten U.S. adults say they have ever used an online dating site or app – including 11% who have done so in the past year, according to a new Pew Research Center survey conducted Oct. 16 to 28, 2019. For some Americans, these platforms have been instrumental in forging meaningful connections: 12% say they have married or been in a committed relationship with someone they first met through a dating site or app. All in all, about a quarter of Americans (23%) say they have ever gone on a date with someone they first met through a dating site or app.

Previous Pew Research Center studies about online dating indicate that the share of Americans who have used these platforms – as well as the share who have found a spouse or partner through them – has risen over time. In 2013, 11% of U.S. adults said they had ever used a dating site or app, while just 3% reported that they had entered into a long-term relationship or marriage with someone they first met through online dating. It is important to note that there are some changes in question wording between the Center’s 2013 and 2019 surveys, as well as differences in how these surveys were fielded. 1 Even so, it is clear that websites and mobile apps are playing a larger role in the dating environment than in previous years. 2

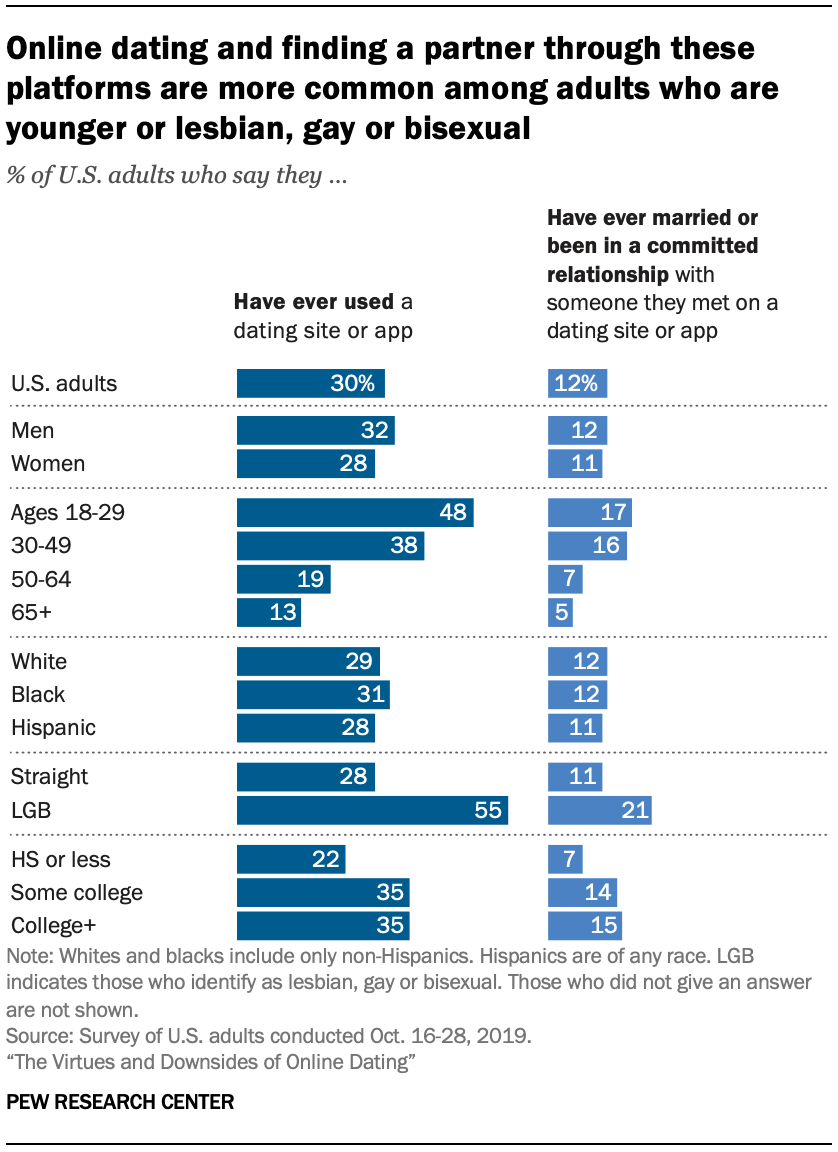

The current survey finds that online dating is especially popular among certain groups – particularly younger adults and those who identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual (LGB). Roughly half or more of 18- to 29-year-olds (48%) and LGB adults (55%) say they have ever used a dating site or app, while about 20% in each group say they have married or been in a committed relationship with someone they first met through these platforms. Americans who have used online dating offer a mixed look at their time on these platforms.

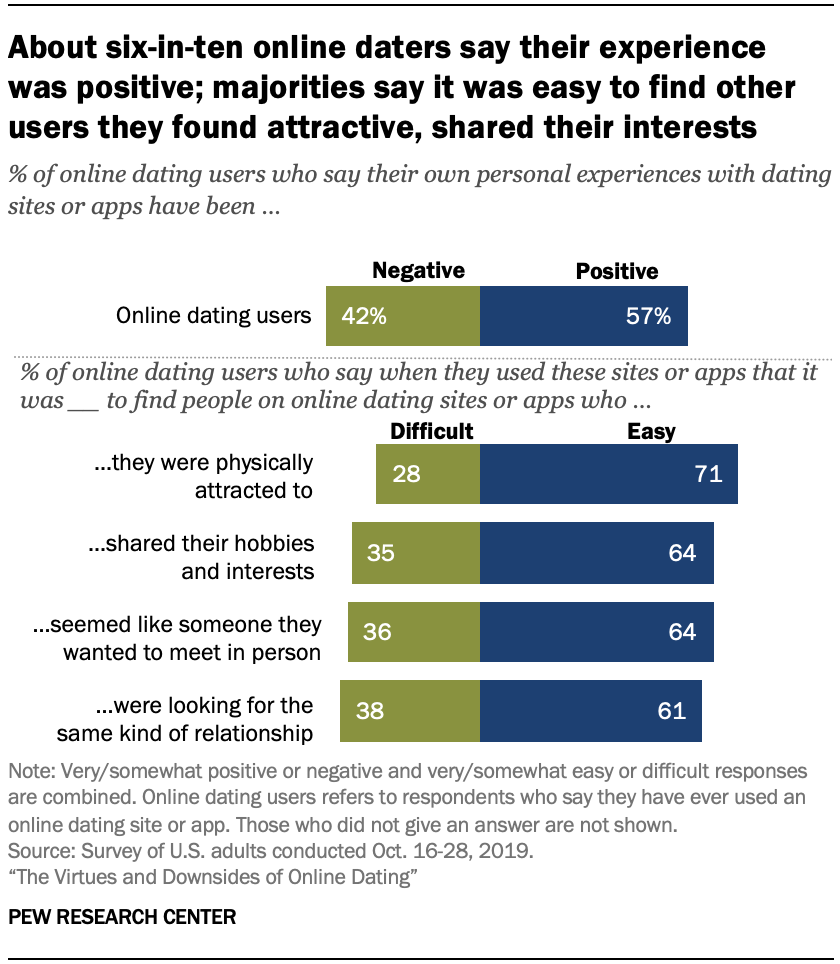

On a broad level, online dating users are more likely to describe their overall experience using these platforms in positive rather than negative terms. Additionally, majorities of online daters say it was at least somewhat easy for them to find others that they found physically attractive, shared common interests with, or who seemed like someone they would want to meet in person. But users also share some of the downsides to online dating. Roughly seven-in-ten online daters believe it is very common for those who use these platforms to lie to try to appear more desirable. And by a wide margin, Americans who have used a dating site or app in the past year say the experience left them feeling more frustrated (45%) than hopeful (28%).

Other incidents highlight how dating sites or apps can become a venue for bothersome or harassing behavior – especially for women under the age of 35. For example, 60% of female users ages 18 to 34 say someone on a dating site or app continued to contact them after they said they were not interested, while a similar share (57%) report being sent a sexually explicit message or image they didn’t ask for.

Online dating has not only disrupted more traditional ways of meeting romantic partners, its rise also comes at a time when norms and behaviors around marriage and cohabitation also are changing as more people delay marriage or choose to remain single.

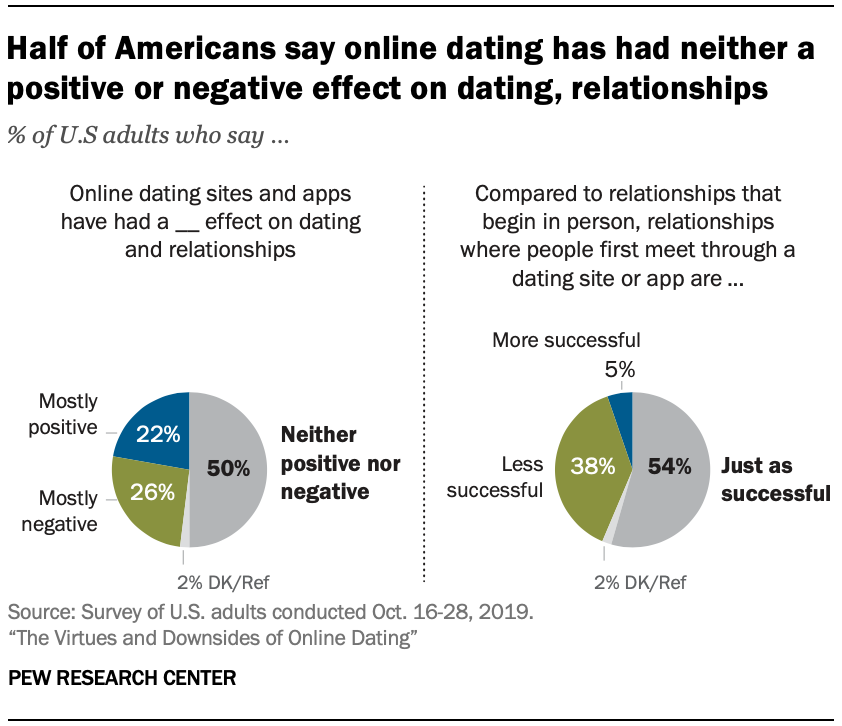

These shifting realities have sparked a broader debate about the impact of online dating on romantic relationships in America. On one side, some highlight the ease and efficiency of using these platforms to search for dates, as well as the sites’ ability to expand users’ dating options beyond their traditional social circles. Others offer a less flattering narrative about online dating – ranging from concerns about scams or harassment to the belief that these platforms facilitate superficial relationships rather than meaningful ones. This survey finds that the public is somewhat ambivalent about the overall impact of online dating. Half of Americans believe dating sites and apps have had neither a positive nor negative effect on dating and relationships, while smaller shares think its effect has either been mostly positive (22%) or mostly negative (26%).

Terminology

Throughout this report, “online dating users” and “online daters” are used interchangeably to refer to the 30% of respondents in this survey who answered yes to the following question: “Have you ever used an online dating site or dating app?”

These findings come from a nationally representative survey of 4,860 U.S. adults conducted online Oct. 16 to 28, 2019, using Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel. The following are among the major findings.

Younger adults – as well as those who identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual – are especially likely to use online dating sites or apps

Some 30% of Americans say they have ever used an online dating site or app. Out of those who have used these platforms, 18% say they are currently using them, while an additional 17% say they are not currently doing so but have used them in the past year.

Experience with online dating varies substantially by age. While 48% of 18- to 29-year-olds say they have ever used a dating site or app, that share is 38% among 30- to 49-year-olds, and it is even smaller among those ages 50 and older. Still, online dating is not completely foreign to those in their 50s or early 60s: 19% of adults ages 50 to 64 say they have used a dating site or app.

Beyond age, there also are striking differences by sexual orientation. 3 LGB adults are about twice as likely as straight adults to say they have used a dating site or app (55% vs. 28%). 4 And in a pattern consistent with previous Pew Research Center surveys , college graduates and those with some college experience are more likely than those with a high school education or less to say they’ve ever online dated.

There are only modest differences between men and women in their use of dating sites or apps, while white, black or Hispanic adults all are equally likely to say they have ever used these platforms.

At the same time, a small share of U.S. adults report that they found a significant other through online dating platforms. Some 12% of adults say they have married or entered into a committed relationship with someone they first met through a dating site or app. This too follows a pattern similar to that seen in overall use, with adults under the age of 50, those who are LGB or who have higher levels of educational attainment more likely to report finding a spouse or committed partner through these platforms.

A majority of online daters say they found it at least somewhat easy to come across others on dating sites or apps that they were physically attracted to or shared their interests

Online dating users are more likely to describe their overall experience with using dating sites or apps in positive, rather than negative, terms. Some 57% of Americans who have ever used a dating site or app say their own personal experiences with these platforms have been very or somewhat positive. Still, about four-in-ten online daters (42%) describe their personal experience with dating sites or apps as at least somewhat negative.

For the most part, different demographic groups tend to view their online dating experiences similarly. But there are some notable exceptions. College-educated online daters, for example, are far more likely than those with a high school diploma or less to say that their own personal experience with dating sites or apps is very or somewhat positive (63% vs. 47%).

At the same time, 71% of online daters report that it was at least somewhat easy to find people on dating sites or apps that they found physically attractive, while about two-thirds say it was easy to find people who shared their hobbies or interests or seemed like someone they would want to meet in person.

While majorities across various demographic groups are more likely to describe their searches as easy, rather than difficult, there are some differences by gender. Among online daters, women are more likely than men to say it was at least somewhat difficult to find people they were physically attracted to (36% vs. 21%), while men were more likely than women to express that it was difficult to find others who shared their hobbies and interests (41% vs. 30%).

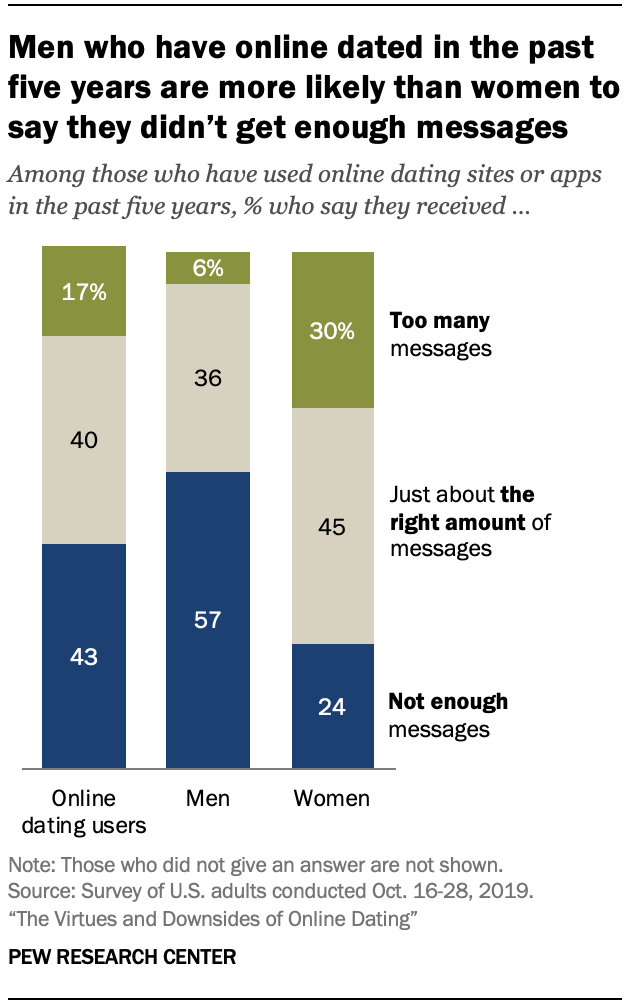

Men who have online dated in the past five years are more likely than women to feel as if they did not get enough messages from other users

When asked if they received too many, not enough or just about the right amount of messages on dating sites or apps, 43% of Americans who online dated in the past five years say they did not receive enough messages, while 17% say they received too many messages. Another 40% think the amount of messages they received was just about right.

There are substantial gender differences in the amount of attention online daters say they received on dating sites or apps. Men who have online dated in the past five years are far more likely than women to feel as if they did not get enough messages (57% vs. 24%). On the other hand, women who have online dated in this time period are five times as likely as men to think they were sent too many messages (30% vs. 6%).

The survey also asked online daters about their experiences with getting messages from people they were interested in. In a similar pattern, these users are more likely to report receiving too few rather than too many of these messages (54% vs. 13%). And while gender differences remain, they are far less pronounced. For example, 61% of men who have online dated in the past five years say they did not receive enough messages from people they were interested in, compared with 44% of women who say this.

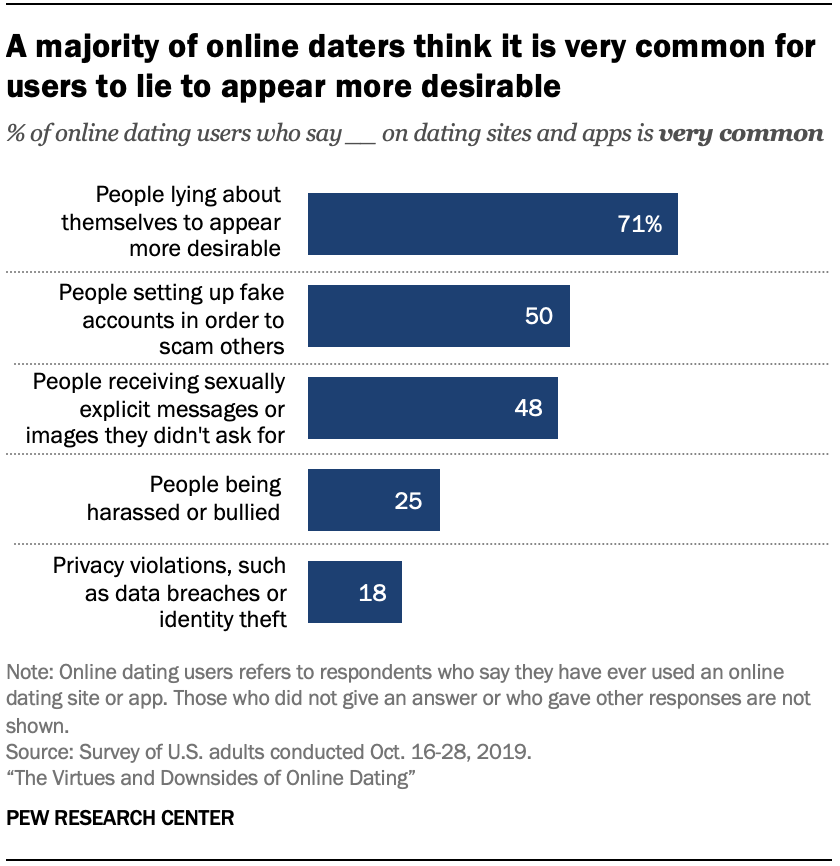

Roughly seven-in-ten online daters think people lying to appear more desirable is a very common occurrence on online dating platforms

Online daters widely believe that dishonesty is a pervasive issue on these platforms. A clear majority of online daters (71%) say it is very common for people on these platforms to lie about themselves to appear more desirable, while another 25% think it is somewhat common. Only 3% of online daters think this is not a common occurrence on dating platforms.

Smaller, but still substantial shares, of online daters believe people setting up fake accounts in order to scam others (50%) or people receiving sexually explicit messages or images they did not ask for (48%) are very common on dating sites and apps. By contrast, online daters are less likely to think harassment or bullying, and privacy violations, such as data breaches or identify theft, are very common occurrences on these platforms.

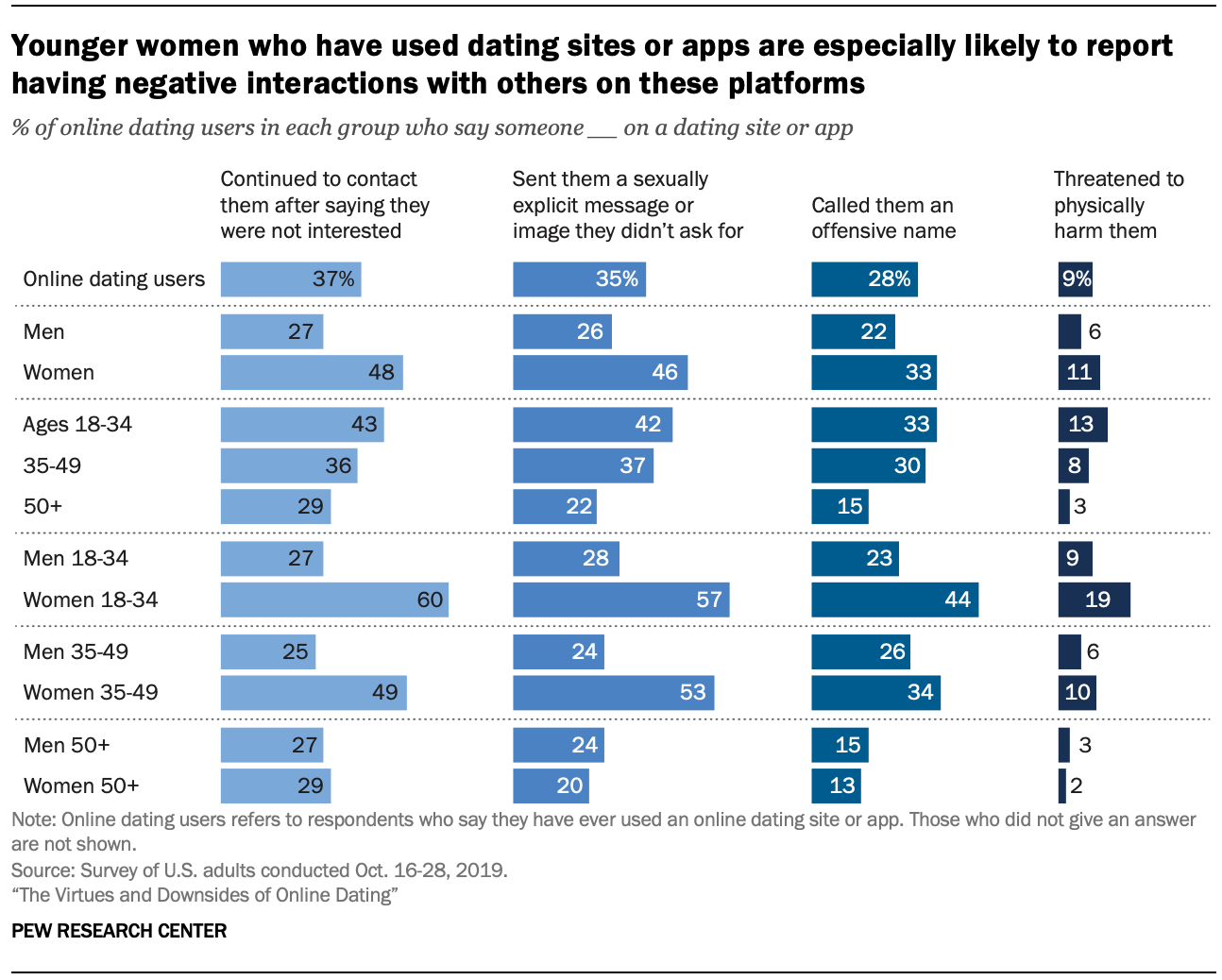

Some users – especially younger women – report being the target of rude or harassing behavior while on these platforms

Some experts contend that the open nature of online dating — that is, the fact that many users are strangers to one another — has created a less civil dating environment and therefore makes it difficult to hold people accountable for their behavior. This survey finds that a notable share of online daters have been subjected to some form of harassment measured in this survey.

Roughly three-in-ten or more online dating users say someone through a dating site or app continued to contact them after they said they were not interested (37%), sent them a sexually explicit message or image they didn’t ask for (35%) or called them an offensive name (28%). Fewer online daters say someone via a dating site or app has threatened to physically harm them.

Younger women are particularly likely to encounter each of these behaviors. Six-in-ten female online dating users ages 18 to 34 say someone via a dating site or app continued to contact them after they said they were not interested, while 57% report that another user has sent them a sexually explicit message or image they didn’t ask for. Other negative interactions are more violent in nature: 19% of younger female users say someone on a dating site or app has threatened to physically harm them – roughly twice the rate of men in the same age range who say this.

The likelihood of encountering these kinds of behaviors on dating platforms also varies by sexual orientation. Fully 56% of LGB users say someone on a dating site or app has sent them a sexually explicit message or image they didn’t ask for, compared with about one-third of straight users (32%). LGB users are also more likely than straight users to say someone on a dating site or app continued to contact them after they told them they were not interested, called them an offensive name or threatened to physically harm them.

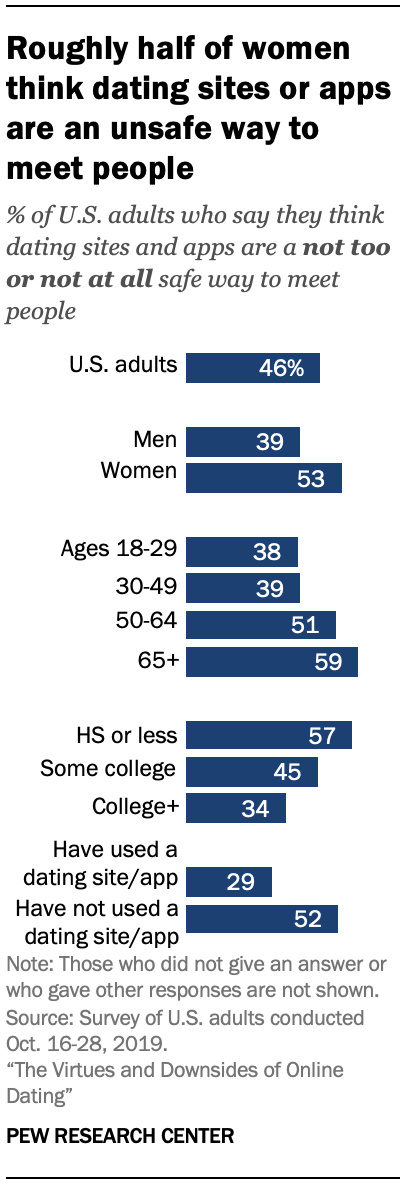

Online dating is not universally seen as a safe way to meet someone

The creators of online dating sites and apps have at times struggled with the perception that these sites could facilitate troubling – or even dangerous – encounters. And although there is some evidence that much of the stigma surrounding these sites has diminished over time, close to half of Americans still find the prospect of meeting someone through a dating site unsafe.

Some 53% of Americans overall (including those who have and have not online dated) agree that dating sites and apps are a very or somewhat safe way to meet people, while a somewhat smaller share (46%) believe these platforms are a not too or not at all safe way of meeting people.

Americans who have never used a dating site or app are particularly skeptical about the safety of online dating. Roughly half of adults who have never used a dating or app (52%) believe that these platforms are a not too or not at all safe way to meet others, compared with 29% of those who have online dated.

There are some groups who are particularly wary of the idea of meeting someone through dating platforms. Women are more inclined than men to believe that dating sites and apps are not a safe way to meet someone (53% vs. 39%).

Age and education are also linked to differing attitudes about the topic. For example, 59% of Americans ages 65 and older say meeting someone this way is not safe, compared with 51% of those ages 50 to 64 and 39% among adults under the age of 50. Those who have a high school education or less are especially likely to say that dating sites and apps are not a safe way to meet people, compared with those who have some college experience or who have at bachelor’s or advanced degree. These patterns are consistent regardless of each group’s own personal experience with using dating sites or apps.

Pluralities think online dating has neither helped nor harmed dating and relationships and that relationships that start online are just as successful as those that begin offline

Americans – regardless of whether they have personally used online dating services or not – also weighed in on the virtues and pitfalls of online dating. Some 22% of Americans say online dating sites and apps have had a mostly positive effect on dating and relationships, while a similar proportion (26%) believe their effect has been mostly negative. Still, the largest share of adults – 50% – say online dating has had neither a positive nor negative effect on dating and relationships.

Respondents who say online dating’s effect has been mostly positive or mostly negative were asked to explain in their own words why they felt this way. Some of the most common reasons provided by those who believe online dating has had a positive effect focus on its ability to expand people’s dating pools and to allow people to evaluate someone before agreeing to meet in person. These users also believe dating sites and apps generally make the process of dating easier. On the other hand, people who said online dating has had a mostly negative effect most commonly cite dishonesty and the idea that users misrepresent themselves.

Pluralities also believe that whether a couple met online or in person has little effect on the success of their relationship. Just over half of Americans (54%) say that relationships where couples meet through a dating site or app are just as successful as those that begin in person, 38% believe these relationships are less successful, while 5% deem them more successful.

Public attitudes about the impact or success of online dating differ between those who have used dating platforms and those who have not. While 29% of online dating users say dating sites and apps have had a mostly positive effect on dating and relationships, that share is 21% among non-users. People who have ever used a dating site or app also have a more positive assessment of relationships forged online. Some 62% of online daters believe relationships where people first met through a dating site or app are just as successful as those that began in person, compared with 52% of those who never online dated.

- Pew Research Center’s 2013 survey about online dating was conducted via telephone, while the 2019 survey was fielded online through the Center’s American Trends Panel . In addition, there were some changes in question wording between these surveys. Please read the Methodology section for full details on how the 2019 survey was conducted. ↩

- Other studies show that online dating is playing a larger role in how romantic partners meet. See Rosenfeld, Michael J., Reuben J. Thomas, and Sonia Hausen. 2019. “ Disintermediating your friends: How online dating in the United States displaces other ways of meeting .” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. ↩

- This survey includes an oversample of lesbian, gay or bisexual (LGB) adults. For more details, see the Methodology section of the report. ↩

- Other research suggests that online dating is an especially important way for populations with a small pool of potential partners – such as those who identify as gay or lesbian – to identify and meet partners. See Rosenfeld, Michael J., and Thomas, Reuben J. 2012. “ Searching for a Mate: The Rise of the Internet as a Social Intermediary .” American Sociological Review. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Gender & Tech

- LGBTQ Attitudes & Experiences

- Online Dating

- Online Harassment & Bullying

- Online Privacy & Security

- Privacy Rights

- Romance & Dating

- Sexual Misconduct & Harassment

- Social Media

U.S. women more concerned than men about some AI developments, especially driverless cars

Young women often face sexual harassment online – including on dating sites and apps, how social media users have discussed sexual harassment since #metoo went viral, there’s a large gender gap in congressional facebook posts about sexual misconduct, facts on foreign students in the u.s., most popular, report materials.

- Shareable facts about Americans’ experiences with online dating

- American Trends Panel Wave 56

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Online-Dating

Jun 13, 2023

540 likes | 562 Views

This insightful guide delves into the world of online dating, equipping you with the knowledge and strategies to navigate the digital landscape and find meaningful relationships. Discover the best platforms and apps, create an appealing profile, and master the art of engaging conversations. Learn effective techniques to spot red flags, assess compatibility, and build trust with potential partners. Navigate the challenges of long-distance relationships and explore strategies for successful online dating etiquette.

Share Presentation

Presentation Transcript

- More by User

Online Dating

Online Dating. A look into finding love on the internet Terri Horn and Emily Miller. What is online dating?.

494 views • 15 slides

For Online Dating

For Online Dating. Gabriella Nurkiewicz CIS 1055-003 11/12/08. Online Dating. Online dating is a dating system that allows individuals, couples and groups to contact each other over the internet.

528 views • 10 slides

Online Dating . Peter Zavitsanos Section 2 . History . Many chat-rooms 1995-1995: Kiss.com and Match.com launched 1996: 16 dating websites listed on yahoo, friendfinder.com 1998: You’ve Got Mail 2002: Social Networking 2007: Americans spent $500 million on online dating. .

454 views • 9 slides

Online Dating. Darcey Sweeney Elle Butler Genesa Rodriguez. Online Dating. Online dating has become an easy applicable way to come intact with other people interested in finding a partner.

369 views • 8 slides

Against Online Dating

Against Online Dating. Presenter : Mai Huynh Section : 005. History. 1986- Before the world wide web, there was a bulletin board system for the few who were active in the computer networking at the time 1955- First online dating service: www.match.com

458 views • 12 slides

Online Dating. By Troy Reeves. Online Dating. Became popular in the early 2000’s Creates more opportunities to find a date Can cost money 50 million online dating accounts today. Pros. Busy p eople can date Easy /Click and wait Find people near you

437 views • 5 slides

Online Dating. Marcus A. Zito CIS1055:Section 011 11/17/08. Safety First!. Over ¼ of “singles” are married!. Watch out for married “singles!” Watch out for scams – Do not send money! Never give out personal information too soon. Set up an anonymous e-mail account

236 views • 10 slides

free online dating

There are numerous dating websites available on internet but there are only some which are genuine enough to find you your hookup.

91 views • 1 slides

Best Online Dating Website | Top Online Dating Site

Are you looking for world's best and free dating website? Than your search ends here at www.worldsingles4love.com. This is a great platform to find singles and make new relationships.

195 views • 5 slides

Online Dating Advice

Hey it’s your trusted expert dating and relationship coaches Dr. Ashley & Dr. Michael. Many of our clients search for their soul mate online. There are so many online dating sites out there it can be overwhelming to even choose a couple of them to start using.

71 views • 1 slides

Online Dating Sites

Find your love with us, make your first date memorable and lovable, meet with you soul mate at best online dating sites platform truelove2.com. For more information, please visit here: http://www.truelove2.com/

100 views • 3 slides

Free Online Dating

Straight; Bisexual; Gay/Lesbian. Man, Woman. Woman. Man; Woman. Continue. Signing up takes two minutes and is totally free. Our matching algorithm helps to find the right people. You can chat, see photos, have fun, and even meet!

38 views • 1 slides

Best Online dating - Online video dating

Start dating today and meet your partner App4Dating helps you to find your soul mate, join us today.

21 views • 1 slides

The Christian singles dating is enhanced with the help of the Christian dating website which is meant to help the visitors find soul partners, friends, and soul partners for themselves. Get ready to find one for yourself. It is one of the online dating sites that has helped the customers in the very best way.

97 views • 5 slides

Best online dating - Video Dating online

22 views • 1 slides

Localtemptation - Online Dating

You need to create a profile that will generate a lot of hot responses from the paying members of a site like localtemptation.

55 views • 4 slides

online dating

Set my Dates is the leading dating website of India.Propose first date gifts to attractive sugar are interested. acceective relationship may be created.

112 views • 5 slides

Online Dating Site

Online Dating Site For Couples And Singles

26 views • 2 slides

online dating belgie

Belgiumdate is the only dating website that connects people based on interests and beliefs. Visit here for meaningful connections and find great dates on Belgiumdate right now. For more information to visit our official website https://belgiumdate.be/ or feel free to contact us.

54 views • 5 slides

On one of the sketchier dating destinations from Latinfeels.com, indeed. Ahhh, Tinder, the famously assigned u201cconnectu201d application.

51 views • 3 slides

Online Dating Site - Internet Dating

Start dating today and meet your partner App4Dating helps you to find your soul mate, join us today. Free online chat, online webcam chat, live video chat

24 views • 1 slides

Free Online Dating Apps | Online Dating Apps India

So if you are really looking to take your virtual banter into reality and meet up with a potential companion, Suitors, one of the best Online Dating Apps India, might not be a bad place to start. The possibilities for digital dating are endless. Online dating gives you the power to make the first move. Whether that may mean swiping right or initiating the conversation, the ball is ultimately in your court. Digital dating can transition into real-life, head-over-heels love. Itu2019s possible, and it has happened for some, so why not give Suitors a try?

50 views • 4 slides

Got any suggestions?

We want to hear from you! Send us a message and help improve Slidesgo

Top searches

Trending searches

26 templates

15 templates

computer technology

287 templates

59 templates

60 templates

49 templates

Dating App Pitch Deck

It seems that you like this template, dating app pitch deck presentation, premium google slides theme and powerpoint template.

They say love is in the air, and this digital age we’re living in can make things easier than ever. Dating apps are very popular, so try giving a pitch deck for your own thanks to this template by Slidesgo, full of affection and useful resources!

Set the right mood at first sight with this design, focused on red and pink tones, the colors of passion and love. The backgrounds exhibit wavy lines, which convey spontaneity and motivate action. In the case of illustrations, they come with flat colors and look like no other you’ve seen before. Have you seen the cute animals finding their beloved ones? These grab a lot of attention, just like the infographic resources, designed to be effective even with big amounts of data. If these resources aren’t enough to boost the popularity of your app, then try our choice of fonts, including a typeface specifically devised for displays, and a condensed font for body text that eases the reading process. So, is this template a match?

Features of this template

- An attractive slide design with endearing illustrations and the perfect color palette to fire people up!

- 100% editable and easy to modify

- 30 different slides to impress your audience

- Contains easy-to-edit graphics and maps

- Includes 1000+ icons and Flaticon’s extension for customizing your slides

- Designed to be used in Google Slides and Microsoft PowerPoint

- 16:9 widescreen format suitable for all types of screens

- Includes information about fonts, colors, and credits of the free and premium resources used

What are the benefits of having a Premium account?

What Premium plans do you have?

What can I do to have unlimited downloads?

Don’t want to attribute Slidesgo?

Gain access to over 25600 templates & presentations with premium from 1.67€/month.

Are you already Premium? Log in

Related posts on our blog

How to Add, Duplicate, Move, Delete or Hide Slides in Google Slides

How to Change Layouts in PowerPoint

How to Change the Slide Size in Google Slides

Related presentations.

Premium template

Unlock this template and gain unlimited access

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Why Submit?

- About Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication

- About International Communication Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, literature review, acknowledgments, about the authors.

- < Previous

Managing Impressions Online: Self-Presentation Processes in the Online Dating Environment

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Nicole Ellison, Rebecca Heino, Jennifer Gibbs, Managing Impressions Online: Self-Presentation Processes in the Online Dating Environment, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , Volume 11, Issue 2, 1 January 2006, Pages 415–441, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00020.x

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This study investigates self-presentation strategies among online dating participants, exploring how participants manage their online presentation of self in order to accomplish the goal of finding a romantic partner. Thirty-four individuals active on a large online dating site participated in telephone interviews about their online dating experiences and perceptions. Qualitative data analysis suggests that participants attended to small cues online, mediated the tension between impression management pressures and the desire to present an authentic sense of self through tactics such as creating a profile that reflected their “ideal self,” and attempted to establish the veracity of their identity claims. This study provides empirical support for Social Information Processing theory in a naturalistic context while offering insight into the complicated way in which “honesty” is enacted online.

The online dating arena represents an opportunity to document changing cultural norms surrounding technology-mediated relationship formation and to gain insight into important aspects of online behavior, such as impression formation and self-presentation strategies. Mixed-mode relationships, wherein people first meet online and then move offline, challenge established theories that focus on exclusively online relationships and provide opportunities for new theory development ( Walther & Parks, 2002 ). Although previous research has explored relationship development and self-presentation online ( Bargh, McKenna, & Fitzsimons, 2002; McLaughlin, Osbourne, & Ellison, 1997; Parks & Floyd, 1996; Roberts & Parks, 1999; Utz, 2000 ), the online dating forum is qualitatively different from many other online settings due to the anticipation of face-to-face interaction inherent in this context ( Gibbs, Ellison, & Heino, 2006 ) and the fact that social practices are still nascent.

In recent years, the use of online dating or online personals services has evolved from a marginal to a mainstream social practice. In 2003, at least 29 million Americans (two out of five singles) used an online dating service ( Gershberg, 2004 ); in 2004, on average, there were 40 million unique visitors to online dating sites each month in the U.S. ( CBC News, 2004 ). In fact, the online personals category is one of the most lucrative forms of paid content on the web in the United States ( Egan, 2003 ) and the online dating market is expected to reach $642 million in 2008 ( Greenspan, 2003 ). Ubiquitous access to the Internet, the diminished social stigma associated with online dating, and the affordable cost of Internet matchmaking services contribute to the increasingly common perception that online dating is a viable, efficient way to meet dating or long-term relationship partners ( St. John, 2002 ). Mediated matchmaking is certainly not a new phenomenon: Newspaper personal advertisements have existed since the mid-19th century ( Schaefer, 2003 ) and video dating was popular in the 1980s ( Woll & Cosby, 1987; Woll & Young, 1989 ). Although scholars working in a variety of academic disciplines have studied these earlier forms of mediated matchmaking (e.g., Ahuvia & Adelman, 1992; Lynn & Bolig, 1985; Woll, 1986; Woll & Cosby, 1987 ), current Internet dating services are substantively different from these incarnations due to their larger user base and more sophisticated self-presentation options.

Contemporary theoretical perspectives allow us to advance our understanding of how the age-old process of mate-finding is transformed through online strategies and behaviors. For instance, Social Information Processing (SIP) theory and other frameworks help illuminate computer-mediated communication (CMC), interpersonal communication, and impression management processes. This article focuses on the ways in which CMC interactants manage their online self-presentation and contributes to our knowledge of these processes by examining these issues in the naturalistic context of online dating, using qualitative data gathered from in-depth interviews with online dating participants.

In contrast to a technologically deterministic perspective that focuses on the characteristics of the technologies themselves, or a socially deterministic approach that privileges user behavior, this article reflects a social shaping perspective. Social shaping of technology approaches ( Dutton, 1996; MacKenzie & Wajcman, 1985; Woolgar, 1996 ) acknowledge the ways in which information and communication technologies (ICTs) both shape and are shaped by social practices. As Dutton points out, “technologies can open, close, and otherwise shape social choices, although not always in the ways expected on the basis of rationally extrapolating from the perceived properties of technology” (1996, p. 9). One specific framework that reflects this approach is Howard’s (2004) embedded media perspective, which acknowledges both the capacities and the constraints of ICTs. Capacities are those aspects of technology that enhance our ability to connect with one another, enact change, and so forth; constraints are those aspects of technology that hinder our ability to achieve these goals. An important aspect of technology use, which is mentioned but not explicitly highlighted in Howard’s framework, is the notion of circumvention , which describes the specific strategies employed by individuals to exploit the capacities and minimize the constraints associated with their use of ICTs. Although the notion of circumvention is certainly not new to CMC researchers, this article seeks to highlight the importance of circumvention practices when studying the social aspects of technology use. 1

Self-Presentation and Self-Disclosure in Online and Offline Contexts

Self-presentation and self-disclosure processes are important aspects of relational development in offline settings ( Taylor & Altman, 1987 ), especially in early stages. Goffman’s work on self-presentation explicates the ways in which an individual may engage in strategic activities “to convey an impression to others which it is in his interests to convey” (1959, p. 4). These impression-management behaviors consist of expressions given (communication in the traditional sense, e.g., spoken communication) and expressions given off (presumably unintentional communication, such as nonverbal communication cues). Self-presentation strategies are especially important during relationship initiation, as others will use this information to decide whether to pursue a relationship ( Derlega, Winstead, Wong, & Greenspan, 1987 ). Research suggests that when individuals expect to meet a potential dating partner for the first time, they will alter their self-presentational behavior in accordance with the values desired by the prospective date ( Rowatt, Cunningham, & Druen, 1998 ). Even when interacting with strangers, individuals tend to engage in self-enhancement ( Schlenker & Pontari, 2000 ).

However, research suggests that pressures to highlight one’s positive attributes are experienced in tandem with the need to present one’s true (or authentic) self to others, especially in significant relationships. Intimacy in relationships is linked to feeling understood by one’s partner ( Reis & Shaver, 1988 ) and develops “through a dynamic process whereby an individual discloses personal information, thoughts, and feelings to a partner; receives a response from the partner; and interprets that response as understanding, validating, and caring” ( Laurenceau, Barrett, & Pietromonaco, 1998 , p. 1238). Therefore, if participants aspire to an intimate relationship, their desire to feel understood by their interaction partners will motivate self-disclosures that are open and honest as opposed to deceptive. This tension between authenticity and impression management is inherent in many aspects of self-disclosure. In making decisions about what and when to self-disclose, individuals often struggle to reconcile opposing needs such as openness and autonomy ( Greene, Derlega, & Mathews, 2006 ).

Interactants in online environments experience these same pressures and desires, but the greater control over self-presentational behavior in CMC allows individuals to manage their online interactions more strategically. Due to the asynchronous nature of CMC, and the fact that CMC emphasizes verbal and linguistic cues over less controllable nonverbal communication cues, online self-presentation is more malleable and subject to self-censorship than face-to-face self-presentation ( Walther, 1996 ). In Goffman’s (1959) terms, more expressions of self are “given” rather than “given off.” This greater control over self-presentation does not necessarily lead to misrepresentation online. Due to the “passing stranger” effect ( Rubin, 1975 ) and the visual anonymity present in CMC ( Joinson, 2001 ), under certain conditions the online medium may enable participants to express themselves more openly and honestly than in face-to-face contexts.

A commonly accepted understanding of identity presumes that there are multiple aspects of the self which are expressed or made salient in different contexts. Higgins (1987) argues there are three domains of the self: the actual self (attributes an individual possesses), the ideal self (attributes an individual would ideally possess), and the ought self (attributes an individual ought to possess); discrepancies between one’s actual and ideal self are linked to feelings of dejection. Klohnen and Mendelsohn (1998) determined that individuals’ descriptions of their “ideal self” influenced perceptions of their romantic partners in the direction of their ideal self-conceptions. Bargh et al. (2002) found that in comparison to face-to-face interactions, Internet interactions allowed individuals to better express aspects of their true selves—aspects of themselves that they wanted to express but felt unable to. The relative anonymity of online interactions and the lack of a shared social network online may allow individuals to reveal potentially negative aspects of the self online ( Bargh et al., 2002 ).

Although self-presentation in personal web sites has been examined ( Dominick, 1999; Schau & Gilly, 2003 ), the realm of online dating has not been studied as extensively (for exceptions, see Baker, 2002; Fiore & Donath, 2004 ), and this constitutes a gap in the current research on online self-presentation and disclosure. The online dating realm differs from other CMC environments in crucial ways that may affect self-presentational strategies. For instance, the anticipated future face-to-face interaction inherent in most online dating interactions may diminish participants’ sense of visual anonymity, an important variable in many online self-disclosure studies. An empirical study of online dating participants found that those who anticipated greater face-to-face interaction did feel that they were more open in their disclosures, and did not suppress negative aspects of the self ( Gibbs et al., 2006 ). In addition, because the goal of many online dating participants is an intimate relationship, these individuals may be more motivated to engage in authentic self-disclosures.

Credibility Assessment and Demonstration in Online Self-Presentation

Misrepresentation in online environments.

As discussed, online environments offer individuals an increased ability to control their self-presentation, and therefore greater opportunities to engage in misrepresentation ( Cornwell & Lundgren, 2001 ). Concerns about the prospect of online deception are common ( Bowker & Tuffin, 2003; Donath, 1999; Donn & Sherman, 2002 ), and narratives about identity deception have been reproduced in both academic and popular outlets ( Joinson & Dietz-Uhler, 2002; Stone, 1996; Van Gelder, 1996 ). Some theorists argue that CMC gives participants more freedom to explore playful, fantastical online personae that differ from their “real life” identities ( Stone, 1996 ; Turkle, 1995 ). In certain online settings, such as online role-playing games, a schism between one’s online representation and one’s offline identity are inconsequential, even expected. For instance, MacKinnon (1995) notes that among Usenet participants it is common practice to “forget” about the relationship between actual identities and online personae.

The online dating environment is different, however, because participants are typically seeking an intimate relationship and therefore desire agreement between others’ online identity claims and offline identities. Online dating participants report that deception is the “main perceived disadvantage of online dating” ( Brym & Lenton, 2001 , p. 3) and see it as commonplace: A survey of one online dating site’s participants found that 86% felt others misrepresented their physical appearance ( Gibbs et al., 2006 ). A 2001 research study found that over a quarter of online dating participants reported misrepresenting some aspect of their identity, most commonly age (14%), marital status (10%), and appearance (10%) ( Brym & Lenton, 2001 ). Perceptions that others are lying may encourage reciprocal deception, because users will exaggerate to the extent that they feel others are exaggerating or deceiving ( Fiore & Donath, 2004 ). Concerns about deception in this setting have spawned related services that help online daters uncover inaccuracies in others’ representations and run background checks on would-be suitors ( Baertlein, 2004 ; Fernandez, 2005 ). One site, True.com , conducts background checks on their users and has worked to introduce legislation that would force other online dating sites to either conduct background checks on their users or display a disclaimer ( Lee, 2004 ).

The majority of online dating participants claim they are truthful ( Gibbs et al., 2006; Brym & Lenton, 2001 ), and research suggests that some of the technical and social aspects of online dating may discourage deceptive communication. For instance, anticipation of face-to-face communication influences self-representation choices ( Walther, 1994 ) and self-disclosures because individuals will more closely monitor their disclosures as the perceived probability of future face-to-face interaction increases ( Berger, 1979 ) and will engage in more intentional or deliberate self-disclosure ( Gibbs et al., 2006 ). Additionally, Hancock, Thom-Santelli, and Ritchie (2004) note that the design features of a medium may affect lying behaviors, and that the use of recorded media (in which messages are archived in some fashion, such as an online dating profile) will discourage lying. Also, online dating participants are typically seeking a romantic partner, which may lower their motivation for misrepresentation compared to other online relationships. Further, Cornwell and Lundgren (2001) found that individuals involved in online romantic relationships were more likely to engage in misrepresentation than those involved in face-to-face romantic relationships, but that this was directly related to the level of involvement. That is, respondents were less involved in their cyberspace relationships and therefore more likely to engage in misrepresentation. This lack of involvement is less likely in relationships started in an online dating forum, especially sites that promote marriage as a goal.

Public perceptions about the higher incidence of deception online are also contradicted by research that suggests that lying is a typical occurrence in everyday offline life ( DePaulo, Kashy, Kirkendol, Wyer, & Epstein, 1996 ), including situations in which people are trying to impress prospective dates ( Rowatt et al., 1998 ). Additionally, empirical data about the true extent of misrepresentation in this context is lacking. The current literature relies on self-reported data, and therefore offers only limited insight into the extent to which misrepresentation may be occurring. Hitsch, Hortacsu, and Ariely (2004) use creative techniques to address this issue, such as comparing participants’ self-reported characteristics to patterns found in national survey data, but no research to date has attempted to validate participants’ self-reported assessments of the honesty of their self-descriptions.

Assessing and Demonstrating Credibility in CMC

The potential for misrepresentation online, combined with the time and effort invested in face-to-face dates, make assessment strategies critical for online daters. These assessment strategies may then influence participants’ self-presentational strategies as they seek to prove their trustworthiness while simultaneously assessing the credibility of others.

Online dating participants operate in an environment in which assessing the identity of others is a complex and evolving process of reading signals and deconstructing cues, using both active and passive strategies ( Berger, 1979; Ramirez, Walther, Burgoon, & Sunnafrank, 2002; Tidwell & Walther, 2002 ). SIP considers how Internet users develop impressions of others, even with the limited cues available online, and suggests that interactants will adapt to the remaining cues in order to make decisions about others ( Walther, 1992; Walther, Anderson, & Park, 1994 ). Online users look to small cues in order to develop impressions of others, such as a poster’s email address ( Donath, 1999 ), the links on a person’s homepage ( Kibby, 1997 ), even the timing of email messages ( Walther & Tidwell, 1995 ). In expressing affinity, CMC users are adept at using language ( Walther, Loh, & Granka, 2005 ) and CMC-specific conventions, especially as they become more experienced online ( Utz, 2000 ). In short, online users become cognitive misers, forming impressions of others while conserving mental energy ( Wallace, 1999 ).

Walther and Parks (2002) propose the concept of “warranting” as a useful conceptual tool for understanding how users validate others’ online identity cues (see also Stone, 1996 ). The connection, or warrant, between one’s self-reported online persona and one’s offline aspects of self is less certain and more mutable than in face-to-face settings ( Walther & Parks, 2002 ). In online settings, users will look for signals that are difficult to mimic or govern in order to assess others’ identity claims ( Donath, 1999 ). For instance, individuals might use search engines to locate newsgroup postings by the person under scrutiny, knowing that this searching is covert and that the newsgroup postings most likely were authored without the realization that they would be archived ( Ramirez et al., 2002 ). In the context of online dating, because of the perceptions of deception that characterize this sphere and the self-reported nature of individuals’ profiles, participants may adopt specific presentation strategies geared towards providing warrants for their identity claims.

In light of the above, our research question is thus:

RQ: How do online dating participants manage their online presentation of self in order to accomplish the goal of finding a romantic partner?

In order to gain insight into this question, we interviewed online dating participants about their experiences, thoughts, and behaviors. The qualitative data reported in this article were collected as part of a larger research project which surveyed a national random sample of users of a large online dating site (N = 349) about relational goals, honesty and self-disclosure, and perceived success in online dating. The survey findings are reported in Gibbs et al. (2006) .

Research Site

Our study addresses contemporary CMC theory using naturalistic observations. Participants were members of a large online dating service, “ Connect.com ” (a pseudonym). Connect.com currently has 15 million active members in more than 200 countries around the world and shares structural characteristics with many other online dating services, offering users the ability to create profiles, search others’ profiles, and communicate via a manufactured email address. In their profiles, participants may include one or more photographs and a written (open-ended) description of themselves and their desired mate. They also answer a battery of closed-ended questions, with preset category-based answers, about descriptors such as income, body type, religion, marital status, and alcohol usage. Users can conduct database searches that generate a list of profiles that match their desired parameters (usually gender, sexual orientation, age, and location). Initial communication occurs through a double-blind email system, in which both email addresses are masked, and participants usually move from this medium to others as the relationship progresses.

Data Collection

Given the relative lack of prior research on the phenomenon of online dating, we used qualitative methods to explore the diverse ways in which participants understood and made sense of their experience ( Berger & Luckman, 1980 ) through their own rich descriptions and explanations ( Miles & Huberman, 1994 ). We took an inductive approach based on general research questions informed by literature on online self-presentation and relationship formation rather than preset hypotheses. In addition to asking about participants’ backgrounds, the interview protocol included open-ended questions about their online dating history and goals, profile construction, honesty and self-disclosure online, criteria used to assess others online, and relationship development. Interviews were semistructured to ensure that all participants were asked certain questions and to encourage participants to raise other issues they felt were relevant to the research. The protocol included questions such as: “How did you decide what to say about yourself in your profile? Are you trying to convey a certain impression of yourself with your profile? If you showed your profile to one of your close friends, what do you think their response would be? Are there any personal characteristics that you avoided mentioning or tried to deemphasize?” (The full protocol is available from the authors.)

As recommended for qualitative research ( Eisenhardt, 1989; Glaser & Strauss, 1967 ), we employed theoretical sampling rather than random sampling. In theoretical sampling, cases are chosen based on theoretical (developed a priori) categories to provide examples of polar types, rather than for statistical generalizability to a larger population ( Eisenhardt, 1989 ). The Director of Market Research at Connect.com initially contacted a subsample of members in the Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay areas, inviting them to participate in an interview and offering them a free one-month subscription to Connect.com in return. Those members who did not respond within a week received a reminder email. Of those contacted, 76 people volunteered to participate in an interview. Out of these 76 volunteers, we selected and scheduled interviews with 36 (although two were unable to participate due to scheduling issues). We chose interview participants to ensure a good mix on each of our theoretical categories: gender, age, urban/rural, income, and ethnicity. We focused exclusively on those seeking relationships with the opposite sex, as this group constitutes the majority of Connect.com users. We also confirmed that they were active participants in the site by ensuring that their last login date was within the past week and checking that each had a profile.

Fifty percent of our participants were female and 50% were male, with 76% from an urban location in Los Angeles and 24% from a more rural area surrounding the town of Modesto in the central valley of California. Participants’ ages ranged from 25 to 70, with most being in their 30s and 40s. Their online dating experience varied from 1 month to 5 years. Although our goal was to sample a mix of participants who varied on key demographic criteria rather than generalizing to a larger population, our sample is in fact reflective of the demographic characteristics of the larger population of Connect.com ’s subscribers. Thirty-four interviews were conducted in June and July 2003. Interviews were conducted by telephone, averaging 45 minutes and ranging from 30 to 90 minutes in length. The interview database consisted of 551 pages, including 223,001 words, with an average of 6559 words per interview.

Data Analysis

All of the phone interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and checked for accuracy by the researcher who conducted the interview. Atlas.ti, a software program used for qualitative content analysis, was used to analyze interview transcripts. Data analysis was conducted in an iterative process, in which data from one informant were confirmed or contradicted by data from others in order to refine theoretical categories, propositions, and conclusions as they emerged from the data ( Lincoln & Guba, 1985 ). We used microanalysis of the text ( Strauss & Corbin, 1998 ) to look for common themes among participants. The data analysis process consisted of systematic line-by-line coding of each transcript by the first two authors. Following grounded theory ( Glaser & Strauss, 1967 ), we used an iterative process of coding. Coding consisted of both factual codes (e.g., “age,”“female,”“Los Angeles”) and referential codes (e.g., “filter,”“rejection,”“honesty”) and served both to simplify and reduce data as well as to complicate data by expanding, transforming, and reconceptualizing concepts ( Coffey & Atkinson, 1996 ). New codes were added throughout the process, and then earlier transcripts were recoded to include these new conceptual categories. All of the data were coded twice to ensure thoroughness and accuracy of codes. The researchers had frequent discussions in which they compared and refined coding categories and schemes to ensure consistency. During the coding process, some codes were collapsed or removed when they appeared to be conceptually identical, while others were broken out into separate codes when further nuances among them became apparent.

A total of 98 codes were generated by the first two authors as they coded the interviews. Unitization was flexible in order to capture complete thought units. Codes were allowed to overlap ( Krippendorff, 1980 ); this method of assigning multiple codes to the same thought unit facilitated the process of identifying relationships between codes. See Appendixes A and B for more information on codes.

These interview data offer insight into the self-presentation strategies utilized by participants in order to maximize the benefits and minimize the risks of online dating. Many of these strategies revolved around the profile, which is a crucial self-presentation tool because it is the first and primary means of expressing one’s self during the early stages of a correspondence and can therefore foreclose or create relationship opportunities. These strategies are intimately connected to the specific characteristics of the online dating context: fewer cues, an increased ability to manage self-presentation, and the need to establish credibility.

The Importance of Small Cues

When discussing their self-presentational strategies, many participants directly or indirectly referred to the fact that they carefully attended to subtle, almost minute cues in others’ presentational messages, and often seemed to take the same degree of care when crafting their own messages. As suggested by SIP ( Walther, 1992 ), subtle cues such as misspellings in the online environment are important clues to identity for CMC interactants. For instance, one participant said she looked for profiles that were well-written, because “I just think if they can’t spell or … formulate sentences, I would imagine that they’re not that educated.” Because writing ability was perceived to be a cue that was “given off” or not as controllable, participants noticed misspelled words in profiles, interpreting them as evidence of lack of interest or education. As one female participant put it, “If I am getting email from someone that obviously can’t spell or put a full sentence together, I’m thinking what other parts of his life suffer from the same lack of attentiveness?” These individuals often created their own profiles with these concerns in mind. For instance, one participant who found spelling errors “unattractive” composed his emails in a word processing program to check spelling and grammar.

Many of the individuals we interviewed explicitly considered how others might interpret their profiles and carefully assessed the signals each small action or comment might send:

I really analyzed the way I was going to present myself. I’m not one of these [people who write] all cutesy type things, but I wanted to be cute enough, smart enough, funny enough, and not sexual at all, because I didn’t want to invite someone who thought I was going to go to bed with them [as soon as] I shook their hand. (PaliToWW, Los Angeles Female) 2

In this case, the participant “really analyzed” her self-presentation cues and avoided any mention of sexuality, which she felt might indicate promiscuity in the exaggerated context of the profile. This same understanding of the signals “sexual” references would send was reflected in the profile of another participant, who purposefully included sexually explicit terminology in his profile to “weed out” poor matches based on his past experience:

The reason I put [the language] in there is because I had some experiences where I got together [with someone], we both really liked each other, and then it turned out that I was somebody who really liked sex and she was somebody that could take it or leave it. So I put that in there to sort of weed those people out. (imdannyboy, Los Angeles Male)

Participants spoke of the ways in which they incorporated feedback from others in order to shape their self-presentational messages. In some cases, they seemed genuinely surprised by the ways in which the digital medium allowed information to leak out. For instance, one male participant who typically wrote emails late at night discussed his reaction to a message that said, “Wow, it’s 1:18 in the morning, what are you doing writing me?” This email helped him realize how much of a “night owl” he was, and “how not attractive that may be for women I’m writing because it’s very clear the time I send the email.” Over time, he also realized that the length of his emails was shaping impressions of him, and he therefore regulated their length. He said:

In the course of [corresponding with others on the site] I became aware of how I had to present myself. Also, I became quite aware that I had to be very brief. … More often than not when I would write a long response, I wouldn’t get a response. … I think it implied. … that I was too desperate for conversation, [that] I was a hermit. (joet8, Los Angeles Male)

The site displayed the last time a user was active on the site, and this small cue was interpreted as a reliable indicator of availability. As one male participant said, “I’m not going to email somebody who hasn’t been on there for at least a week max. If it’s been two weeks since she’s logged on, forget her, she’s either dating or there’s a problem.”

Overall, the mediated nature of these initial interactions meant that fewer cues were available, therefore amplifying the importance of those that remained. Participants carefully attended to small cues, such as spelling ability or last login date, in others’ profiles in order to form impressions. In a self-reflexive fashion, they applied these techniques to their own presentational messages, carefully scrutinizing both cues given (such as photograph) and, when possible, those perceived to be given off (such as grammar).

Balancing Accuracy and Desirability in Self-Presentation

Almost all of our participants reported that they attempted to represent themselves accurately in their profiles and interactions. Many expressed incomprehension as to why others with a shared goal of an offline romantic relationship would intentionally misrepresent themselves. As one participant explained, “They polish it up some, like we all probably do a little bit, but for the most part I would say people are fairly straightforward.” However, as suggested by previous research on self-disclosure and relationship development, participants reported competing desires. At times, their need to portray a truthful, accurate self-representation was in tension with their natural inclination to project a version of self that was attractive, successful, and desirable. Speaking about this tendency towards impression management, one participant noted that she could see why “people would be dishonest at some point because they are still trying to be attractive … in the sense they would want this other person to like them.”

One way in which participants reconciled their conflicting needs for positive self-presentation and accuracy was to create profiles that described a potential, future version of self. In some cases, participants described how they or others created profiles that reflected an ideal as opposed to actual self: “Many people describe themselves the way they want [to be] … their ideal themselves.” For example, individuals might identify themselves as active in various activities (e.g., hiking, surfing) in which they rarely participated, prompting one participant to proclaim sarcastically, “I’ve never known so many incredibly athletic women in my life!” One participant explained,

For instance, I am also an avid hiker and [scuba diver] and sometimes I have communicated with someone that has presented themselves the same way, but then it turns out they like scuba diving but they haven’t done it for 10 years, they like hiking but they do it once every second year … I think they may not have tried to lie; they just have perceived themselves differently because they write about the person they want to be … In their profile they write about their dreams as if they are reality. (Christo1, Los Angeles Male)

In two cases, individuals admitted to representing themselves as less heavy than they actually were. This thinner persona represented a (desired) future state for these individuals: “The only thing I kind of feel bad about is that the picture I have of myself is a very good picture from maybe five years ago. I’ve gained a little bit of weight and I feel kind of bad about that. I’m going to, you know, lose it again.” In another case, a woman who misrepresented her weight online used an upcoming meeting as incentive to minimize the discrepancy between her actual self and the ideal self articulated in her profile:

I’ve lost 44 pounds since I’ve started [online dating], and I mean, that’s one of the reasons I lost the weight so I can thank online dating for that. [Because] the first guy that hit on me, I checked my profile and I had lied a little bit about the pounds, so I thought I had better start losing some weight so that it would be more honest. That was in December, and I’ve lost every week since then. (MaryMoon, Los Angeles Female)

In this case, a later physical change neutralized the initial discursive deception. For another participant, the profile served as an opportunity to envision and ideate a version of self that was future-focused and goal-oriented:

I sort of thought about what is my ideal self. Because when you date, you present your best foot forward. I thought about all the qualities that I have, you know, even if I sometimes make mistakes and stuff. … And also got together the best picture I had, and kind of came up with what I thought my goals were at the time, because I thought that was an important thing to stress. (Marty7, Los Angeles Male)

Overall, participants did not see this as engaging in deceptive communication per se, but rather as presenting an idealized self or portraying personal qualities they intended to develop or enhance.

Circumventing Constraints

In addition to impression management pressures, participants’ expressed desires for accurate representation were stymied by various constraints, including the technical interface of the website. In order to activate an online profile, participants had to complete a questionnaire with many closed-ended responses for descriptors such as age, body type, zip code, and income. These answers became very important because they were the variables that others used to construct searches in order to narrow the vast pool of profiles. In fact, the front page of Connect.com includes a “quick” search on those descriptors believed to be most important: age, geographical location, inclusion of photograph, and gender/sexual orientation.

The structure of the search parameters encouraged some to alter information to fit into a wider range of search parameters, a circumvention behavior that guaranteed a wider audience for their profile. For example, participants tended to misrepresent their age for fear of being “filtered out.” It was not unusual for users who were one or two years older than a natural breakpoint (i.e., 35 or 50) to adjust their age so they would still show up in search results. This behavior, especially if one’s actual age was revealed during subsequent email or telephone exchanges, seemed to be socially acceptable. Many of our participants recounted cases in which others freely and without embarrassment admitted that they had slightly misrepresented something in their profile, typically very early in the correspondence:

They don’t seem to be embarrassed about [misrepresenting their age] … in their first reply they say, “oh by the way, I am not so many years, I am that many years.” And then if I ask them, they say, well, they tend to be attracted to a little bit younger crowd and they are afraid that guys may surf for a certain age group of women, because you use those filters. I mean, I may choose to list only those that are between X and Y years old and they don’t want to be filtered away. … They are trying to be sort of clever so that people they tend to be attracted to will actually find them. (Christo1, Los Angeles Male)

If lying about one’s age was perceived to be the norm, those who didn’t engage in this practice felt themselves to be at a disadvantage (see Fiore & Donath, 2004 ). For instance, one participant who misrepresented his age on his profile noted:

I’m such an honest guy, why should I have to lie about my age? On the other hand, if I put X number of years, that is unattractive to certain people. They’re never going to search that group and they’re never going to have an opportunity to meet me, because they have a number in their mind just like I do. … Everybody lies about their age or a lot of people do. … So I have to cheat too in order to be on the same page as everybody else that cheats. If I don’t cheat that makes me seem twice as old. So if I say I am 44, people think that I am 48. It blows. (RealSweetheart, Bay Area Male)

In the above cases, users engaged in misrepresentation triggered by the social norms of the environment and the structure of the search filters. The technical constraints of the site may have initiated a more subtle form of misrepresentation when participants were required to choose among a limited set of options, none of which described them sufficiently. For instance, when creating their profiles, participants had to designate their “perfect date” by selecting one from a dozen or so generic descriptions, which was frustrating for those who did not see any that were particularly appealing. In another case, one participant complained that there was not an option to check “plastic surgery” as one of his “turn-offs” and thus he felt forced to try to discern this from the photos; yet another participant expressed his desire for a “shaved” option under the description of hair type (“I resent having to check ‘bald’”).

Foggy Mirror

In addition to the cases in which misrepresentation was triggered by technical constraints or the tendency to present an idealized self, participants described a third branch of unintentional misrepresentation triggered by the limits of self-knowledge. We call this phenomenon “foggy mirror” based on this participant’s explanation:

People like to write about themselves. Sometimes it’s not truthful, but it’s how they see themselves and that gives you a different slant on an individual. This is how they really see themselves. Sometimes you will see a person who weighs 900 pounds and—this is just an exaggeration—and they will have on spandex, you’ll think, “God, I wish I had their mirror, because obviously their mirror tells them they look great.” It’s the same thing with online. (KarieK, Bay Area Female)

This user acknowledges that sometimes others weren’t lying per se, but the fact that their self-image differed from others’ perceptions meant that their textual self-descriptions would diverge from a third party’s description. In explaining this phenomenon, KarieK used the metaphor of a mirror to emphasize the self-reflexive nature of the profile. She also refers to the importance of subtle cues when she notes that a user’s self-presentation choices give one a “different slant on an individual.” The term “foggy mirror” thus describes the gap between self-perceptions and the assessments made by others. The difference might be overly positive (which was typically the case) or negative, as the below example illustrates. A male participant explained:

There was one gal who said that she had an “average” body shape. … When I met her she was thin, and she said she was “average,” but I think she has a different concept of what “average” is. So I then widened my scope [in terms of search parameters] and would go off the photographs. What a woman thinks is an “average” body and what I think is an “average” body are two different things. (joet8, Los Angeles Male)

In this case, the participant acknowledged the semantic problems that accompany textual self-descriptions and adopted a strategy of relying on photographs as visual, objective evidence, instead of subjective, ambiguous terms like “average.” To counter the “foggy mirror” syndrome in their own profiles, some individuals asked friends or family members to read their profiles in order to validate them.

In regards to self-presentation, the most significant tension experienced by participants was one not unique to the online medium: mediating between the pressures to present an enhanced or desired self ( Goffman, 1959 ) and the need to present one’s true self to a partner in order to achieve intimacy ( Reis & Shaver, 1988 ). In their profiles and online interactions, they attempted to present a vision of self that was attractive, engaging, and worthy of pursuit, but realistic and honest enough that subsequent face-to-face meetings were not unpleasant or surprising. Constructing a profile that reflected one’s “ideal self” ( Higgins, 1987 ) was one tactic by which participants reconciled these pressures. In general, although all of our participants claimed they attempted to be honest in their self-presentation, misrepresentations occurred when participants felt pressure to fudge in order to circumvent the search filters, felt the closed-ended options provided by the site didn’t describe them accurately, or were limited by their self-knowledge.

Establishing Credibility

The increased ability to engage in selective self-presentation, and the absence of visual cues in the online environment, meant that accuracy of self-presentation was a salient issue for our interviewees. The twin concerns that resulted from these factors—the challenge of establishing the credibility of one’s own self-descriptions while assessing the credibility of others’ identity claims—affected one another in a recursive fashion. In an environment in which there were limited outside confirmatory resources to draw upon, participants developed a set of rules for assessing others while incorporating these codes into their own self-presentational messages. For example, one participant made sure that her profile photograph showed her standing up because she felt that sitting or leaning poses were a camouflage technique used by heavier people. This illustrates the recursive way in which participants developed rules for assessing others (e.g., avoid people in sitting poses) while also applying these rubrics to their own self-presentational messages (e.g., don’t show self in sitting pose).

Participants adopted specific tactics in order to compensate for the fact that traditional methods of information seeking were limited and that self-reported descriptions were subject to intentional or unintentional misrepresentation when others took advantage of the “selective self-presentation” ( Walther & Burgoon, 1992 ) available in CMC. As one participant noted, “You’re just kind of blind, you don’t know if what they’re saying in their profile online is true.” Acknowledging the potential for misrepresentation, participants also sought to “show” aspects of their personality in their profiles versus just “telling” others about themselves. They created their profiles with an eye towards stories or content that confirmed specific personality traits rather than including a ‘laundry list’ of attributes. As one Los Angeles male participant explained, “I attempted to have stories in my profile somewhat to attempt to demonstrate my character, as opposed to, you know, [just writing] ‘I’m trustworthy,’ and all that bit.” This emphasis on demonstration as opposed to description was a tactic designed to circumvent the lack of a shared social context that would have warranted identity claims and hedged against blatant deception.

Another aspect of “showing” included the use of photographs, which served to warrant or support claims made in textual descriptions. Profile photographs communicated not only what people looked like (or claimed to look like), but also indicated the qualities they felt were important. For instance, one man with a doctorate included one photo of himself standing against a wall displaying his diplomas and another of him shirtless. When asked about his choice of photos, he explained that he selected the shirtless photo because he was proud of being in shape and wanted to show it off. He picked the combination of the two photos because “one is sort of [my] intellectual side and one is sort of the athletic side.” In this case, the photos functioned on multiple levels: To communicate physical characteristics, but also self-concept (the aspects of self he was most proud of), and as an attempt to provide evidence for his discursive claims (his profile listed an advanced degree and an athletic physique).

To summarize, our data suggest that participants were cognizant of the online setting and its association with deceptive communication practices, and therefore worked to present themselves as credible. In doing so, they drew upon the rules they had developed for assessing others and turned these practices into guidelines for their own self-presentational messages.