Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

- Artificial Intelligence

Market Research

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

- Qualitative Research Interviews

Try Qualtrics for free

How to carry out great interviews in qualitative research.

11 min read An interview is one of the most versatile methods used in qualitative research. Here’s what you need to know about conducting great qualitative interviews.

What is a qualitative research interview?

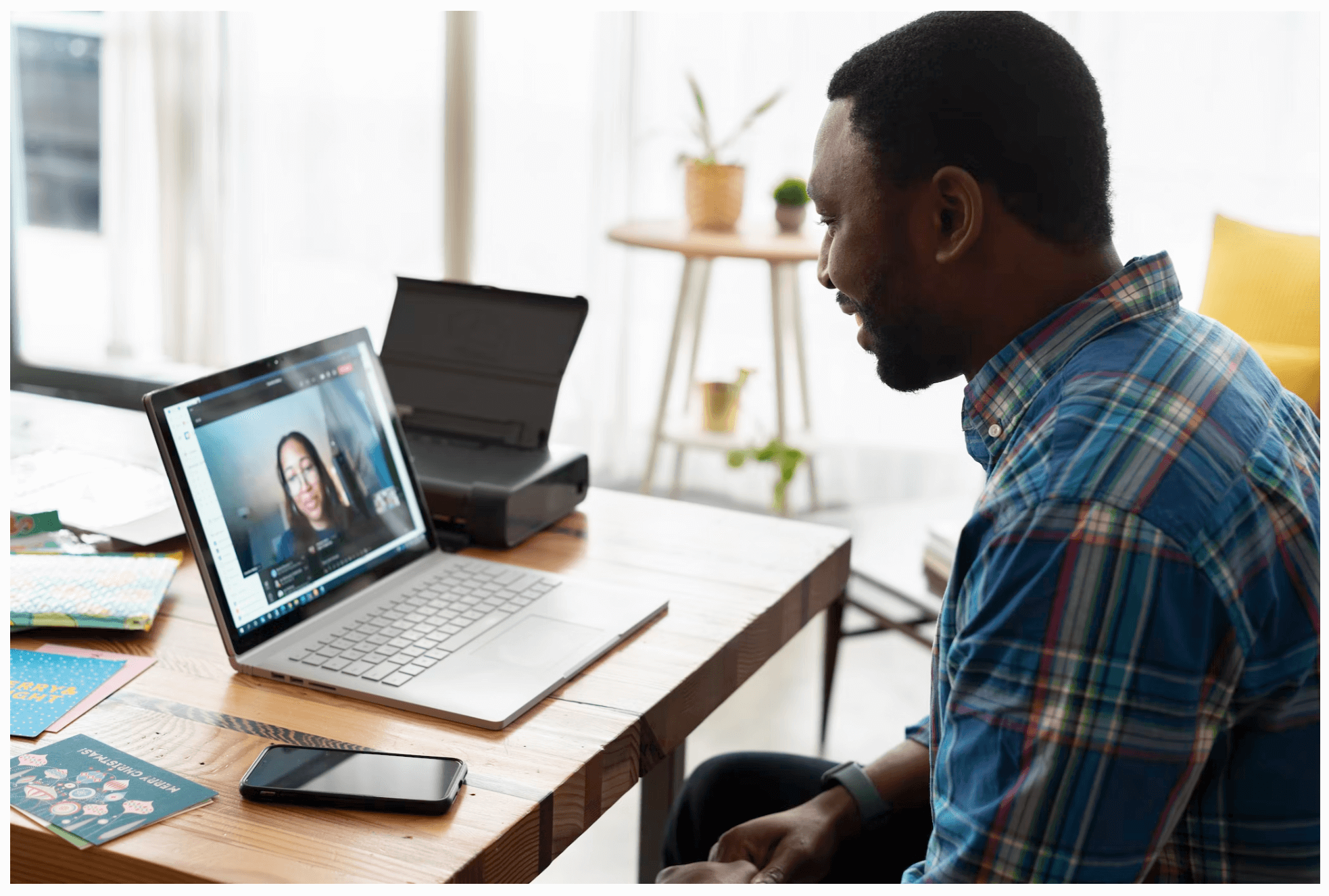

Qualitative research interviews are a mainstay among q ualitative research techniques, and have been in use for decades either as a primary data collection method or as an adjunct to a wider research process. A qualitative research interview is a one-to-one data collection session between a researcher and a participant. Interviews may be carried out face-to-face, over the phone or via video call using a service like Skype or Zoom.

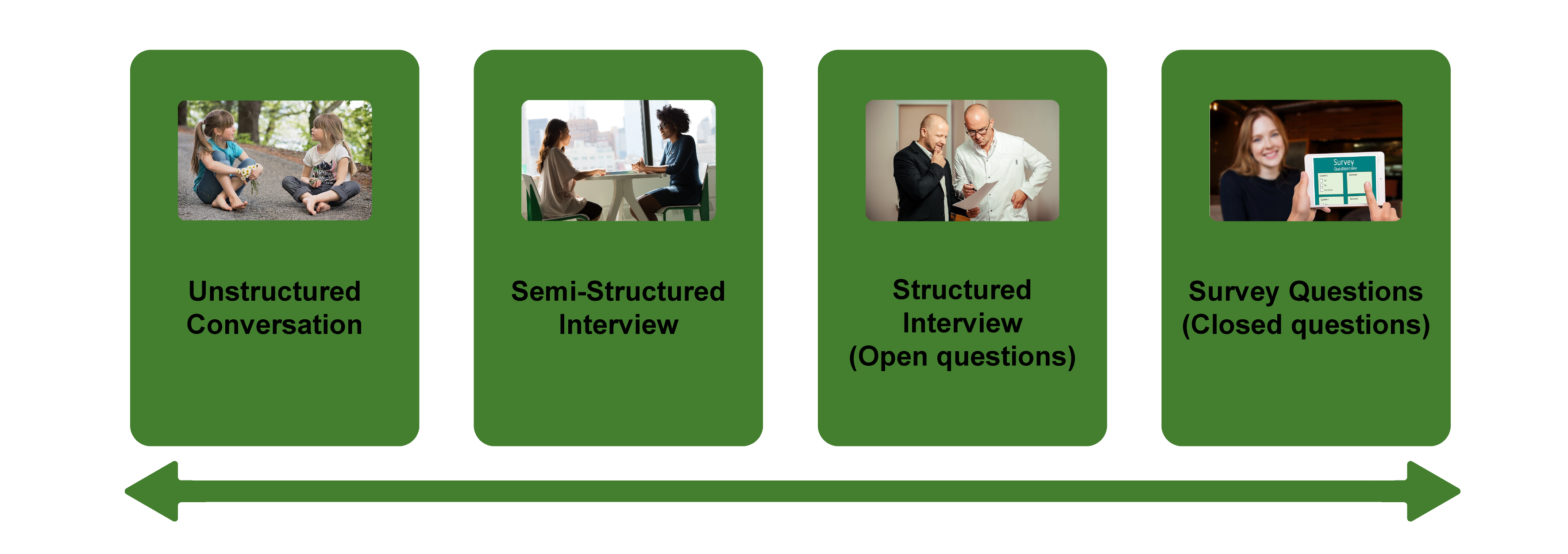

There are three main types of qualitative research interview – structured, unstructured or semi-structured.

- Structured interviews Structured interviews are based around a schedule of predetermined questions and talking points that the researcher has developed. At their most rigid, structured interviews may have a precise wording and question order, meaning that they can be replicated across many different interviewers and participants with relatively consistent results.

- Unstructured interviews Unstructured interviews have no predetermined format, although that doesn’t mean they’re ad hoc or unplanned. An unstructured interview may outwardly resemble a normal conversation, but the interviewer will in fact be working carefully to make sure the right topics are addressed during the interaction while putting the participant at ease with a natural manner.

- Semi-structured interviews Semi-structured interviews are the most common type of qualitative research interview, combining the informality and rapport of an unstructured interview with the consistency and replicability of a structured interview. The researcher will come prepared with questions and topics, but will not need to stick to precise wording. This blended approach can work well for in-depth interviews.

Free eBook: The qualitative research design handbook

What are the pros and cons of interviews in qualitative research?

As a qualitative research method interviewing is hard to beat, with applications in social research, market research, and even basic and clinical pharmacy. But like any aspect of the research process, it’s not without its limitations. Before choosing qualitative interviewing as your research method, it’s worth weighing up the pros and cons.

Pros of qualitative interviews:

- provide in-depth information and context

- can be used effectively when their are low numbers of participants

- provide an opportunity to discuss and explain questions

- useful for complex topics

- rich in data – in the case of in-person or video interviews , the researcher can observe body language and facial expression as well as the answers to questions

Cons of qualitative interviews:

- can be time-consuming to carry out

- costly when compared to some other research methods

- because of time and cost constraints, they often limit you to a small number of participants

- difficult to standardize your data across different researchers and participants unless the interviews are very tightly structured

- As the Open University of Hong Kong notes, qualitative interviews may take an emotional toll on interviewers

Qualitative interview guides

Semi-structured interviews are based on a qualitative interview guide, which acts as a road map for the researcher. While conducting interviews, the researcher can use the interview guide to help them stay focused on their research questions and make sure they cover all the topics they intend to.

An interview guide may include a list of questions written out in full, or it may be a set of bullet points grouped around particular topics. It can prompt the interviewer to dig deeper and ask probing questions during the interview if appropriate.

Consider writing out the project’s research question at the top of your interview guide, ahead of the interview questions. This may help you steer the interview in the right direction if it threatens to head off on a tangent.

Avoid bias in qualitative research interviews

According to Duke University , bias can create significant problems in your qualitative interview.

- Acquiescence bias is common to many qualitative methods, including focus groups. It occurs when the participant feels obliged to say what they think the researcher wants to hear. This can be especially problematic when there is a perceived power imbalance between participant and interviewer. To counteract this, Duke University’s experts recommend emphasizing the participant’s expertise in the subject being discussed, and the value of their contributions.

- Interviewer bias is when the interviewer’s own feelings about the topic come to light through hand gestures, facial expressions or turns of phrase. Duke’s recommendation is to stick to scripted phrases where this is an issue, and to make sure researchers become very familiar with the interview guide or script before conducting interviews, so that they can hone their delivery.

What kinds of questions should you ask in a qualitative interview?

The interview questions you ask need to be carefully considered both before and during the data collection process. As well as considering the topics you’ll cover, you will need to think carefully about the way you ask questions.

Open-ended interview questions – which cannot be answered with a ‘yes’ ‘no’ or ‘maybe’ – are recommended by many researchers as a way to pursue in depth information.

An example of an open-ended question is “What made you want to move to the East Coast?” This will prompt the participant to consider different factors and select at least one. Having thought about it carefully, they may give you more detailed information about their reasoning.

A closed-ended question , such as “Would you recommend your neighborhood to a friend?” can be answered without too much deliberation, and without giving much information about personal thoughts, opinions and feelings.

Follow-up questions can be used to delve deeper into the research topic and to get more detail from open-ended questions. Examples of follow-up questions include:

- What makes you say that?

- What do you mean by that?

- Can you tell me more about X?

- What did/does that mean to you?

As well as avoiding closed-ended questions, be wary of leading questions. As with other qualitative research techniques such as surveys or focus groups, these can introduce bias in your data. Leading questions presume a certain point of view shared by the interviewer and participant, and may even suggest a foregone conclusion.

An example of a leading question might be: “You moved to New York in 1990, didn’t you?” In answering the question, the participant is much more likely to agree than disagree. This may be down to acquiescence bias or a belief that the interviewer has checked the information and already knows the correct answer.

Other leading questions involve adjectival phrases or other wording that introduces negative or positive connotations about a particular topic. An example of this kind of leading question is: “Many employees dislike wearing masks to work. How do you feel about this?” It presumes a positive opinion and the participant may be swayed by it, or not want to contradict the interviewer.

Harvard University’s guidelines for qualitative interview research add that you shouldn’t be afraid to ask embarrassing questions – “if you don’t ask, they won’t tell.” Bear in mind though that too much probing around sensitive topics may cause the interview participant to withdraw. The Harvard guidelines recommend leaving sensitive questions til the later stages of the interview when a rapport has been established.

More tips for conducting qualitative interviews

Observing a participant’s body language can give you important data about their thoughts and feelings. It can also help you decide when to broach a topic, and whether to use a follow-up question or return to the subject later in the interview.

Be conscious that the participant may regard you as the expert, not themselves. In order to make sure they express their opinions openly, use active listening skills like verbal encouragement and paraphrasing and clarifying their meaning to show how much you value what they are saying.

Remember that part of the goal is to leave the interview participant feeling good about volunteering their time and their thought process to your research. Aim to make them feel empowered , respected and heard.

Unstructured interviews can demand a lot of a researcher, both cognitively and emotionally. Be sure to leave time in between in-depth interviews when scheduling your data collection to make sure you maintain the quality of your data, as well as your own well-being .

Recording and transcribing interviews

Historically, recording qualitative research interviews and then transcribing the conversation manually would have represented a significant part of the cost and time involved in research projects that collect qualitative data.

Fortunately, researchers now have access to digital recording tools, and even speech-to-text technology that can automatically transcribe interview data using AI and machine learning. This type of tool can also be used to capture qualitative data from qualitative research (focus groups,ect.) making this kind of social research or market research much less time consuming.

Data analysis

Qualitative interview data is unstructured, rich in content and difficult to analyze without the appropriate tools. Fortunately, machine learning and AI can once again make things faster and easier when you use qualitative methods like the research interview.

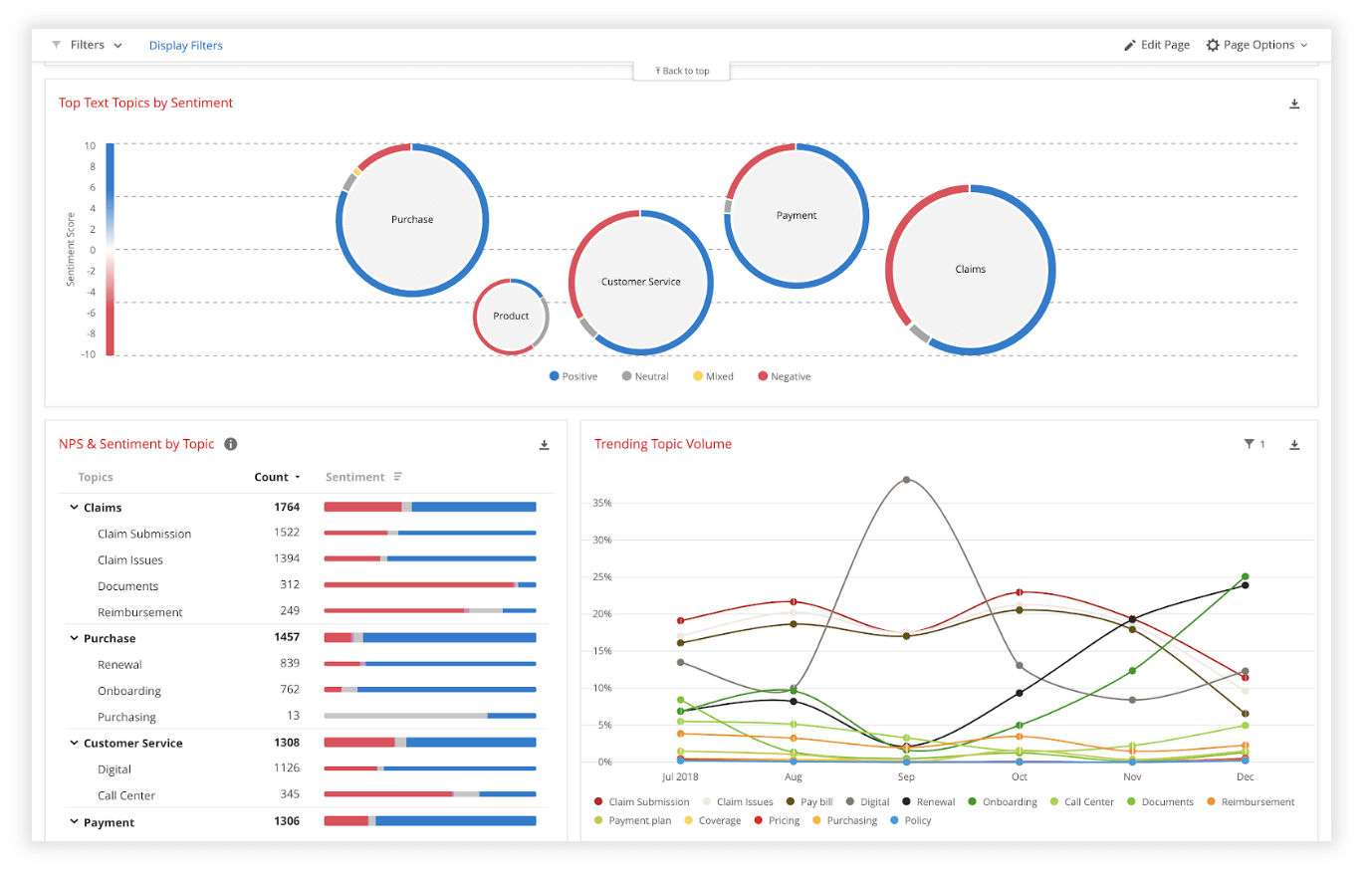

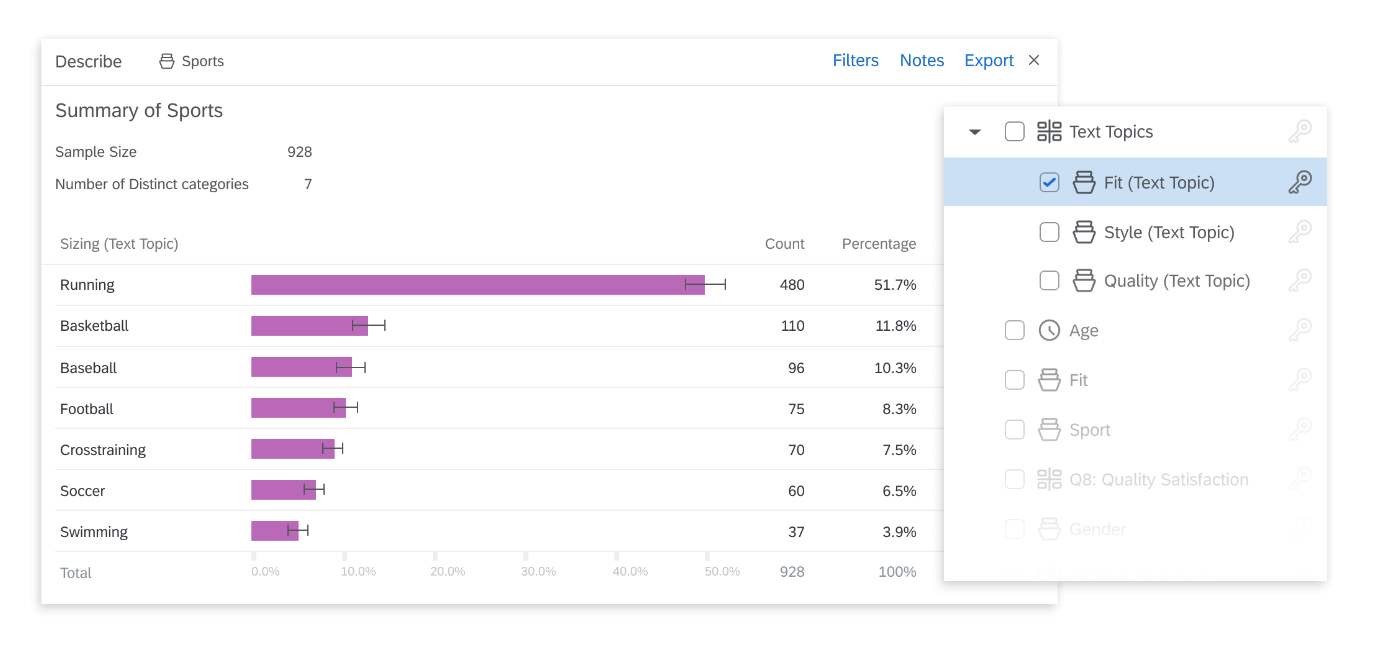

Text analysis tools and natural language processing software can ‘read’ your transcripts and voice data and identify patterns and trends across large volumes of text or speech. They can also perform khttps://www.qualtrics.com/experience-management/research/sentiment-analysis/

which assesses overall trends in opinion and provides an unbiased overall summary of how participants are feeling.

Another feature of text analysis tools is their ability to categorize information by topic, sorting it into groupings that help you organize your data according to the topic discussed.

All in all, interviews are a valuable technique for qualitative research in business, yielding rich and detailed unstructured data. Historically, they have only been limited by the human capacity to interpret and communicate results and conclusions, which demands considerable time and skill.

When you combine this data with AI tools that can interpret it quickly and automatically, it becomes easy to analyze and structure, dovetailing perfectly with your other business data. An additional benefit of natural language analysis tools is that they are free of subjective biases, and can replicate the same approach across as much data as you choose. By combining human research skills with machine analysis, qualitative research methods such as interviews are more valuable than ever to your business.

Related resources

Market intelligence 10 min read, marketing insights 11 min read, ethnographic research 11 min read, qualitative vs quantitative research 13 min read, qualitative research questions 11 min read, qualitative research design 12 min read, primary vs secondary research 14 min read, request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Conducting In-Depth Interviews via Mobile Phone with Persons with Common Mental Disorders and Multimorbidity: The Challenges and Advantages as Experienced by Participants and Researchers

Azadé azad.

1 Department of Psychology, Stockholm University, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden; [email protected]

Elisabet Sernbo

2 Department of Social Work, University of Gothenburg, SE-405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected]

Veronica Svärd

3 Department of Social Work, Södertörn University, SE-141 89 Huddinge, Sweden

4 Division of Insurance Medicine, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, SE-171 77 Stockholm, Sweden

Lisa Holmlund

5 Unit of Intervention and Implementation Research for Worker Health, Institute of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, SE-171 77 Stockholm, Sweden; [email protected] (L.H.); [email protected] (E.B.B.)

Elisabeth Björk Brämberg

Associated data.

The data presented in this study are available on request from the authors V.V. and E.B.B. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Qualitative interviews are generally conducted in person. As the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) prevents in-person interviews, methodological studies which investigate the use of the telephone for persons with different illness experiences are needed. The aim was to explore experiences of the use of telephone during semi-structured research interviews, from the perspective of participants and researchers. Data were collected from mobile phone interviews with 32 individuals who had common mental disorders or multimorbidity which were analyzed thematically, as well as field notes reflecting researchers’ experiences. The findings reveal several advantages of conducting interviews using mobile phones: flexibility, balanced anonymity and power relations, as well as a positive effect on self-disclosure and emotional display (leading to less emotional work and social responsibility). Challenges included the loss of human encounter, intense listening, and worries about technology, as well as sounds or disturbances in the environment. However, the positive aspects of not seeing each other were regarded as more important. In addition, we present some strategies before, during, and after conducting telephone interviews. Telephone interviews can be a valuable first option for data collection, allowing more individuals to be given a fair opportunity to share their experiences.

1. Introduction

In-depth interviews are one of the most common forms of data gathering in qualitative research [ 1 , 2 ]. The purpose is to obtain information about how individuals view, understand, and make sense of their lives, and how they assign meaning to particular experiences, events, and subjects [ 3 ]. Hence, such interviews are appropriate for exploring phenomena about which we have limited knowledge, or in generating knowledge to inform social or healthcare interventions [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ].

Qualitative interviews have traditionally been conducted in-person, either individually or in focus groups [ 3 , 5 ]. There seems to be a consensus in the literature that in-person interviews are the best (‘gold standard’) format [ 9 ]. However, they are not always possible due to logistical, practical, or safety reasons, such as the COVID-19 pandemic [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. The COVID-19 pandemic has produced a wide range of changes in customary practices of conducting research, particularly on the gathering of data [ 13 ]. Researchers, ourselves included, have been forced to use remote methods, such as telephone interviews as a mean of collecting qualitative data. Although proven to be a viable way of data collection [ 14 ], there is still a lack of methodological discussion about the use of telephone interviews for certain groups of participants [ 15 ], such as persons with common mental disorders (CMDs) (i.e., depression, anxiety, adjustment disorders) or multimorbidity. These groups, with symptoms of e.g., exhaustion and bodily aches, have been difficult to recruit to research studies, due to mental distress, medications, stigma, and a reduced capacity to take on new information and thus to consent to participation, for example [ 16 , 17 ]. Telephone interviews might be a well-suited solution for these groups [ 18 ]; however, there are a lack of studies investigating the experiences of telephone interviews from the perspective of people with CMDs and multimorbidity.

Telephone Interview as a Method of Collecting Qualitative Data

Previously, telephone interviews have been used as a last resort for collecting qualitative research data [ 3 , 19 , 20 ]. The most common concerns about telephone interviews are that they might have a negative impact on the richness and quality of the collected information [ 19 ], the challenges in establishing rapport [ 21 , 22 ], and the inability to respond to visual and emotional cues [ 15 ]. Other criticisms involve the increased risk of misunderstandings and the inability to know if and when to ask probing questions or introduce more sensitive topics [ 20 ]. However, a growing body of literature using the telephone as a way of collecting data, as well as studies comparing the use of telephone with in-person interviews, do not find support for the traditionalist view. Rather, scholars make the case for the potential of in-depth telephone interviews as a viable and equivalent option for qualitative research [ 23 ], with some even arguing that they are, in some regards, methodologically superior to in-person interviews [ 24 , 25 ].

Available studies have, for example, shown that telephone interviews generate the same amount of data richness as in-person interviews in terms of word count and topic-related information [ 26 , 27 ], and only modest differences in depth of data [ 28 ], even though telephone interviews tend to be shorter [ 29 ]. One study [ 14 ] found that in-person interviews are more conversational and detailed than remote methods (telephone and Skype), but that they do not clearly lead to differences in interview ratings. Other scholars [ 30 ] state that telephone offer flexibility regarding when and where to conduct the interview [ 24 ], which increase anonymity and reduce distraction (for interviewees), thus improving the information given [ 26 , 31 ]. Several attempts to develop tools improving the success of in-depth telephone interviewing have been made [ 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ], considering the criticisms raised against telephone interviews, as well as the counter arguments. These tools provide a set of comprehensive approaches to follow before, during, and after the interview to ensure effective use. These emphasize the significance of communicating the importance of participant contribution, explaining the purpose of the study in the early phase of the research either in writing or initial telephone contact, and establishing rapport through small talk when first contacting the participant [ 32 ]. Because of the absence of non-verbal cues and difficulties in identifying visual emotional expressions, the importance of providing verbal feedback and follow up probes are stressed [ 36 ], as well as using vocalizations and clarification to show responsiveness [ 32 ]. Such verbal cues or probed questions can in turn result in both parties listening more carefully [ 30 ].

Studies investigating the use of telephone interviews from the perspective of the interviewee have mostly yielded positive results. For many, telephone interviews are the preferred choice, when given the option to choose [ 25 ], for reasons of convenience and greater anonymity [ 35 , 37 ]. In contrast to traditionalist views, some researchers have found that interviewees find it is easy to establish rapport [ 23 ]. Hence, some authors claim that telephone interviewing is suitable for vulnerable and marginalized populations and more sensitive questions [ 32 , 35 ].

Telephone interviews can also have advantages for the interviewer, by reducing self-consciousness [ 24 ] and bias and stereotyping about the interviewer. It can also benefit the researcher–participant relationship by providing a more balanced power dynamic between the two [ 27 ].

One group of participants who, despite the growing body of literature examining the advantages and challenges of telephone interviews, have not been further investigated, are people with experience of sick leave due to illness, such as CMDs and/or multimorbidity. It has been argued that there are specific challenges in interviewing people with mental illnesses and barriers having to do with the consequences of their symptoms (such as mental distress, medications, stigma, reduced ability to take in new information, and passive interaction with healthcare professionals) [ 16 , 17 , 38 ]. Research has also shown that recent illness or present ill health affect research participation negatively, and using telephone interviews has been suggested as a way of enhancing response rate [ 18 ]. Including the experiences of people who are or have been on sick leave due to CMDs or multimorbidity in research is critical, due to, for example, the individual and societal burden. However, in doing so, the interview situation must be adapted to suit the participants needs. This may be provided by conducting telephone interviews.

The aim of the present study is, therefore, to explore the use of the telephone for semi-structured interviews from the perspective of these individuals. A further aim is to address the challenges and advantages of using the telephone from the perspective of the interviewer. To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous methodological studies into the use of telephone interviews with individuals with CMD or multimorbidity. Our study is, therefore, a unique contribution to the scarce research available on this topic.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. study design.

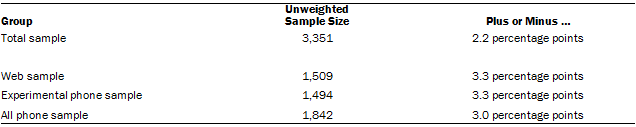

This study used a qualitative approach involving semi-structured interviews with people with CMD or multimorbidity with on-going sick leave, or who had returned to work after sick leave. The interviews reflect the participants’ unique experiences regarding the use of mobile phone when collecting data. The participants are included in two different projects (see Table 1 ). In these projects, in-person interviews were changed to telephone interviews because of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study focuses on the last part of the interviews where probes were added to take account the participants experience of being interviewed by mobile phone. We primarily refer to mobile phones, as ownership of mobile phone is generally, and in Sweden in particular, much higher than landline ownership [ 39 ]. Both participants and researchers used mobile phones during the interviews.

Information about the overall aim of respective project and study, recruitment, and procedure.

RECO = The rehabilitation coordinator project; PROSA = A problem solving intervention in primary health care aimed at reducing sick leave among people suffering from common mental disorders – a cluster-randomized trial; SA = sickness absence; CMD = common mental disorders; RTW = return to work; I, II, III = refers to the three different projects in which data was collected from.

2.2. Participants

Participants were recruited from two projects: the RECO-project [ 40 , 41 ] and the PROSA-project [ 42 ] (see Table 1 ). All participants were given written and/or oral information by post about the study, including that participation was voluntary. In the RECO-project, 70 individuals received written information, of whom 13 replied that they were interested in participating. One person later declined to participate because their knowledge of the investigated subject in the particular project was limited. In one of the PROSA-projects, 49 individuals were given oral information about the study. Of those, 18 received written information and agreed to be contacted by the researcher. Of these, 10 took part in an interview. In the other study linked to the PROSA-project, 15 participants were contacted by telephone by the researcher for information. Of these, three did not answer, one did not fit eligibility criteria, one declined to participate, and 10 were included in the present study.

In total, 32 participants were included in this study. Twelve participants were on sick leave due to multimorbidity, and twenty were on sick leave or had recently returned to work after sick leave due to CMDs. The participants represent a variety in ages (ages ranged from 22 to 62) and gender, although a majority were women (7 men and 25 women) and type of employment. For more detailed information about the participants, see Table 2 .

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants ( n = 32).

2.3. Data Collection

Data were gathered through semi-structured mobile phone interviews with the participants and field notes kept by the researchers. The interviews were conducted between March and September 2020. The interviews followed interview guides with primary questions specifically for each project, and follow-up probes about being interviewed by telephone. Only the data relating to telephone interviewing are included in the present study. The probes addressed the participants’ experience of the conducted telephone interviews, including the challenges and advantages of being interviewed over the telephone. The participants were also asked to reflect over possible alternative modes of interviews (such as in-person or internet-based methods). Their reflections are not to be understood as direct comparisons between the use of different research methodologies, as they only partook in telephone interviews and not internet-based, or in-person interview methods. Rather, the participants experiences are to be understood as unique reflections on being interviewed using mobile phones. During the interviews, the participants reflect on experiences of meeting professionals in-person and/or working with different technologies.

Interviews ranged in length from about 30 to 90 min which included the whole interview. Three members of the research team (first, second and fourth author) conducted the interviews. All members of the research team were experienced in conducting in-depth in-person interviews, and some had also previous experience of conducting telephone interviews. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim in Swedish. The transcripts and digital recordings were cross-checked.

The data also consist of field notes [ 43 ] with reflections upon our experience as researchers conducting in-depth in-person and telephone interviews as a means of data collection. The field notes were written down directly after every phone call. Each interviewer noted their immediate recollection of the conversation, summarizing how they experienced the interview format and content as well as their reflections about the interview generally.

2.4. Data Analysis

Thematic analysis [ 44 , 45 ] was conducted to explore participants’ views of participating in qualitative interviews by telephone. We began our analysis by reading through the transcribed text to familiarize ourselves with the material and search for patterns in the data. We then identified important and interesting features focusing on the semantic and latent meanings in line with the aim. These features included words, sentences, or paragraphs relating to what the participants found difficult or easy with being interviewed over telephone, and were then condensed and assigned a code. The third step involved searching for possible themes, by identifying and coding them across participants. This step was performed on the first 22 interviews collected and refocused the analysis at the broader level of themes, rather than codes, and involved sorting the codes into potential themes and collating all the relevant coded data extracts within these themes. The first and second author made a first draft of the themes and the remaining researchers read through and discussed them. This discussion involved reviewing and refining themes, both with regard to each theme in itself and in relation to the data set. The ten remaining transcripts were analyzed based on the drafted themes and used to check for depth in the analysis. No new themes were added and the initial themes were adjusted until the conceptual depth in the themes was agreed upon [ 46 ]. A final step involved rechecking the data to code additional codes that may have been missed, before refining and defining the essence of each theme by naming them. During the analysis process, the coding and themes were repeatedly discussed by all the researchers until consensus was reached. During the analysis process, the first author translated the themes and quotes from Swedish into English and the second and the fourth authors reviewed the translations, before all the authors made a final revision.

The field notes are understood as condensed rather than transcribed, and were jointly discussed and elaborated, inspired by notions on how the written record and memory interact [ 47 ]. Our reflections based on these field notes are analyzed and presented separately from the analysis of the participants’ narratives. This analysis was inspired by thematic analysis, although not following Braun and Clarke’s [ 44 , 45 ] six steps.

3. Results and Discussion

The findings are presented in three themes, including discussion in relation to relevant research: flexibility of location, personal well-being and emotional ease, and balancing anonymity and social responsibility. The themes reflect patterns of meaning relating to the experiences of being interviewed over the mobile phone. They are not hierarchical in relation to one another but rather presuppose each other; one enables the other while being on the same analytical level. After presenting the three themes, the researchers’ experiences and reflections are offered and discussed in relation to the themes.

3.1. Flexibility of Location

The first theme had to do with practical and environmental aspects, such as the flexibility to choose place and surrounding during the mobile phone interview, compared to landline phone or in-person options. The flexibility of using mobile phones meant that the participants were free to choose place for the interview, and did not have to physically meet the interviewer. Most participants conducted the interviews from home, and a few from their workplace—geographically close and familiar environments. Not having to spend time or energy travelling was of great importance for the majority of the participants. The time saved in telephone interview compared to in-person was, for some participants, crucial for participation. For example, one participant said:

It’s also nice to be at home and not have to go to an interview and so on, because that would use so much energy. Then maybe I would choose not to do it. (Female, 38 years, multimorbidity)

Although these benefits—for both participants and researchers—have been identified in previous research [ 24 , 26 ], our results point to the importance of flexibility, both regarding geography and time for this group of participants specifically. As their mental and/or physical health makes it difficult for them to travel, telephone interviews offer a way of participating without having to do so.

Flexibility was also associated with the specificity of the mobile phone rather than other choices of technology, for example internet-based voice options, such as Skype or Zoom. While some thought that internet-based video options were desirable because of the ability to see each other, the vast majority preferred the mobile phone option. As one participant said:

I would also have worried about the [internet-based] technology, I have to say, it’s probably inevitable that you do to some degree. (Female, 34 years, stress syndrome)

Using the mobile phone, however, added no extra technical demands for the participant and, therefore, meant limited technical worries before and/or during the interview. Some used internet-based technology at work, but others had no experience of such tools and said they would have been worried about coping with the technology. This is in line with Seitz’s [ 48 ] reasoning that technical difficulties may have a negative impact on the interview. For our participants, in contrast to what other researchers have purposed, Sipes et al.’s [ 49 ] voice-only options are not always the equal option to using mobile phones.

3.2. Personal Well-Being and Emotional Ease

In personal and emotional terms, using mobile phone rather than in-person interviews was seen as helping the participants’ well-being and emotional ease. Suffering from CMD and/or multimorbidity was already perceived as demanding by the participants. In comparison to an in-person interview or internet-video based options, the mobile phone interview not only enabled them to choose place and surrounding for the interview, but also position and the ability to move around while talking. Some participants appreciated the ability to conduct the interview via mobile phone while having a walk outside, which had not been possible using landline phone. Being physically comfortable and free was highly valued, given that the participants had symptoms of CMDs and/or multimorbidity with depression, exhaustion, and bodily aches. In line with Cachia and Millward’s findings [ 24 ], our participants reported being less self-conscious while not having to think about how to sit or conform to social cues and norms as in an in-person or video-based meeting.

Being able to do the interview over the telephone caused less anxiety and was less emotionally demanding. This is described by one of the participants:

There’s a lot of fear and stress, and talking about these things can make it, since it’s so personal, I get scared of being judged and looking someone in the eye, seeing them react in a negative way about something that has… You can’t see that on the phone. (Female, 50 years, multimorbidity)

Other emotional advantages had to do with feeling less inhibited when not being able to see each other. For some, this meant being able to talk more freely; for others, it meant displaying more emotions such as crying. For example, one participant said that it was easier to continue talking even though she had been crying, because the interviewer may not even have noticed. The telephone was experienced as providing a positive sense of protection when sharing. As one participant put it:

When you get an anxiety attack, or, I don’t know how to put it, but like, you feel kind of protected behind the phone. (Male, 25 years, depression)

In this regard, conducting the interviews over the telephone led to fewer emotions being visible, so it was easier to cry than when meeting someone in person. For some participants, the less emotion work demanded by telephone interviews was a precondition for participation. These findings reinforce those of previous studies [ 37 , 50 ], showing that some participants regarded the telephone interview as the ‘only option’ for them being able to participate at all. This suggests that telephone interviews can increase participation and, thus, the heterogeneity and breadth of the data. In particular, it seems to be crucial for being able to involve some of the most vulnerable groups, i.e., those with limited energy and an ability to participate in an in-person interview due to mental or physical illness. As such groups have been outlined as hard to recruit for research studies [ 16 ], our results point to that telephone interviews might help overcome the challenges in interviewing people with for example CMDs and/or multimorbidity. Using the telephone can simply be considered as an easier way to participate in research interviews, by placing less demands on the participant compared to video options or face-to-face interviews.

These findings also relate to how telephone interviews reduce participants’ emotion work in accordance to Hochschild [ 51 ], because they do not visibly convey and manage their feelings in the social interaction. Goffman [ 52 ] argues that people strive to convey their feelings in a socially acceptable way and manage their emotional expressions and impressions. By removing the visible dimensions of social interaction, and giving participants the opportunity to be ‘protected behind the phone’, the emotion work is not completely removed from the interaction, but the conditions are changed because participants can maintain the desired anonymity and emotional distance. The telephone interview, compared with in-person interviews, allows interviewees to shed an unseen tear, lie down without anybody knowing, and keep visible emotions private. The freedom offered by these choices, together with the flexibility and time- and energy-saving aspects discussed earlier, suggest that telephone interviews allow participants to share their experiences while putting less strain on them as they do so.

3.3. Balancing Anonymity and Social Responsibility

The third theme focuses more explicitly on the relational aspects of the mobile phone interview. The physical distance, with the participant and interviewer unable to see each other, did not only make it easier to protect your emotional expressions, but also created a sense of anonymity, making it easier to talk about sensitive subjects. As one of the participants put it:

It gets very personal, these are very personal things to talk about … and I don’t know you. So then it can be nice to have this little bit of distance. (Male, 46 years, depression)

The sense of freedom related to the ability to choose the level of intimacy in the interview, unique to the telephone mode, thus contributing to a sense of anonymity and psychological distance. This also made it more likely for interviewees to feel comfortable talking about sensitive subjects [ 25 , 37 ]. The perceived higher degree of anonymity might result in richer data and a higher validity among responses, as the telephone mode could decrease social desirability. For example, avoiding being seen by an in-person or video-based interviewer can create a feeling of being less judged and not being in the gaze of the professional [ 25 ]. Telephone interviews can thus lead to a more balanced power dynamic between the participant and the interviewer [ 27 ]. The feeling of distance was also described as making it easier to take control and end a conversation which may not have felt good or right.

Telephone interviews required less social responsibility since participants were able to focus solely on what the other person was saying instead of thinking about social cues and norms as in an in-person meeting (such as where to look, how to sit, when to nod or smile, and so on). Goffman [ 52 ] uses the term impression management to discuss how people put on performances during in-person social interactions in order to manage, rather than show, their feelings. Our findings suggest that the telephone interview may ease the burden on the participants to put on a performance, as they do not have to think about their body language, or relate to social clues or norms to the same extent as in an in-person interview.

The downside of this form of interview was the required intense listening, which is described as somewhat demanding by some participants. Receiving fewer cues via visual interaction is, thus, described as a balancing act, as some participants stressed the importance of the interviewer keeping the conversation on track, not leaving them unsure about whether or not they are talking about the ‘right’ things. They mentioned the importance of the interviewer’s voice, both in relation to being able to understand the other and being understood. For example, participants described finding it easy to ‘get a feeling’ for the other person through the tone of voice instead of through the other social cues used when you are sitting face to face. As one of the participants explained, the way the interviewer spoke, referring to the tone of voice, helped to install confidence. Although verbalization has been stressed in telephone interviews [ 32 ], our finding adds to research by stressing the importance of not only what is being said but also how it is said. The importance of tone and attribute of the interviewers’ voice is, thus, a crucial tool to use within in-depth telephone interviewing.

When talking about the negative aspects of telephone interviews, the participants also mentioned several factors in the first contact and impression of an in-person meeting. For example, they mentioned that it is interesting and fun to meet new people and that it is nice to see the other person. This was often linked to curiosity and ‘the human encounter’. Negative aspects of not being able to see each other were also described to affect interactions:

Not that I find it difficult, but if you’re sitting together, in a way you have another kind of interplay because you can see one and other. (Female, 46 years, multimorbidity)

However, because they viewed this interview as a one-off and were not going to have a further relationship with the person interviewing them, the positive aspects of not seeing each other were regarded as more important. As they explained, they were first and foremost interested in conveying their experiences. Some also reported that they were able to create their own image of the interviewer, which filled the same function as an in-person meeting.

3.4. Researchers’ Experiences and Reflections

The analysis of the researchers’ experiences and field notes resulted in two themes having to do with worries and challenges about the technology and relational and social aspects , as well as a third overarching theme of understanding the telephone as a ‘shield’ . Quotations from our field notes are provided for each theme in order to illustrate and contextualize the results. Regarding the first theme, worries and challenges about the technology , the researchers reflected on that the mobile phone interview was sometimes imbued with worries and challenges about the technology used, for example not being able to control the quality of participants’ network coverage or mobile equipment. Using mobile phone can, therefore, involve more challenges regarding technology compared to using landline phone. Moreover, the participants´ choice of environment in some cases meant disturbances that challenged the researchers´ sense of being able to control the interview. The possible negative impact on the interview if, for example, the interviewees network coverage was insufficient, or if there were disturbances in the physical or social environment is illustrated by this reflection:

The first time I call him, he is in his car, and we agree that I can call again in 15 min, when he has arrived home. At the beginning of the interview, it is somewhat difficult because he has not found a friend for his son to play with [as he had hoped] and he is a bit hesitant related to what he can do to occupy his son. I offer to reschedule, but he wants to do the interview and starts a movie [that his son can watch during the interview]. (Written by L.H. The quote refers to a male participant, 45 years, stress syndrome)

The participants being in a situation where they can decide if they want to wash their dishes or take a stroll while talking in their mobile phone can leave the researcher experiencing loss of power over the situation. This disadvantage for the researcher can be an advantage for the participant, showing that using the telephone for interviewing involves giving away some power over the situation to the interviewee. Whale [ 50 ] points to the loss of power for the researcher, in interviewing over Skype or telephone, as something that enables a more balanced power dynamic between the interviewer and the interviewee. Our findings show that using a mobile phone further expands the freedom for the participants, and inevitably means a redistribution of power from the researcher to the participants. At the same time, the interviewer controls most elements in the interview, such as the topics discussed [ 53 ]. The redistribution of power can, therefore, be both welcomed and challenging.

Regarding other aspects having to do with the theme relational and social aspects , we also reflected on how the participants´ sense of emotional ease contrasted with the researchers’ feelings of being less able to recognize and respond to the participants´ emotions and states of mind. A lack of visible feedback meant a need to use the voice and the language more consciously to convey understanding and show interest in the participant’s unique experiences.

I can hear that she is sad. I tell her this and say something confirmatory. I emphasize that it is ok to take a break if she wants to. (Written by E.S. The quote refers to a female participant, 38 years, stress syndrome)

In an in-person interview or video-based option, it is possible to non-verbally assure participants that their stories are ‘on track’, or show sympathy and understanding, in order to not disrupt them. In a telephone interview, however, the nod of the head must be made audible, all the while avoiding interrupting the interviewee. For the interviewer, this involves a clear shift from the non-verbal feedback style to the audible.

She is crying, which she had hinted might happen the first time that we talked. I tell her that we can take a break or end the interview if needed. Not seeing the other person makes it more difficult for me to decide whether to continue or not. I must trust her. It is apparent that the verbal response becomes more important when someone is showing emotion. (Written by A.A. The quote refers to a female participant, 35 years, multimorbidity)

An advantage, however, was that the format of the telephone interview seemed to enrich the participants’ stories. For example, the participants themselves conveyed that being behind the telephone acted as a ‘shield’ , which, in a sense, allowed them to more easily express themselves, and we reflected over the openness and details in the participants’ stories. For some, the possibility to choose their level of emotional closeness or distance meant that they were more comfortable talking about sensitive subjects.

I am surprised to see that their stories have a flow to them, that they have shared openly. They also reflect on this themselves, that the anonymity allows an openness. (Written by L.H.)

4. Reflections and Strategies for Conducting Telephone Interviews—Before, during and after

The results point to the importance of telephone interviews by decreasing emotional demands put on the participants, focusing the importance of anonymity and social responsibility, and providing the participants with the freedom to choose level of intimacy, but also contributing to research despite dealing with symptoms. Although the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic obliged us, as researchers, to conduct interviews by phone, some participants regarded the mobile phone option as a crucial factor which enabled them to participate in a research interview. These results are important to address in future studies, because the participants—often struggling with symptoms such as pain, exhaustion, or anxiety—had to spend less energy on paying attention to social cues and norms, and could instead focus on how to reveal their personal experiences.

More information about the informal insights derived from qualitative interviews as a means for data has been called for [ 33 ]. Our findings highlight challenges, advantages, and possible strategies which can be useful (1) when preparing the interview, (2) during the interview, and (3) after the interview. These strategies are relevant for all telephone interviews with participants where some are particularly important for the study group, i.e., participants struggling with symptoms such as pain, exhaustion, or anxiety.

When preparing the interview, our findings indicate the importance of a first introductory call to familiarize the interviewer and interviewee with each other and discuss how the interview will be carried out. This entails telling participants that they should preferably be able to talk freely without distraction, and that silence during the interview should be interpreted as active listening from an interviewer who does not want to disturb their stories. This introductory conversation is to prepare the participant for the particular form of dialog that a telephone interview is, but it also serves to establish rapport. In other words, it is a way of ‘getting to know each other’ without seeing each other, rather than clarifying the use of the voice as well as silences. This is important for building trust between the interviewee and the interviewer in line with the recommendation of, for example, Drabble et al. [ 32 ]. We also found that it was important for the interviewer to convey to the participant his or her understanding of the circumstances that are central to the subject of the interview—in our case, their health status and work disability. This suggests that the potential of the method is related to the interviewer being sufficiently familiar with the research topic and the specific kind of difficulties the participants are facing. This can be an important factor for validating the participant during the interview and building a trusting relationship over the telephone, as we were not able to do so using visual cues. As all participants used mobile phones, we found it necessary to encourage participants to choose a place where they have good reception and minimal background noise, especially important when using mobile phone compared to landline phone. This can prevent problems arising during the telephone interview and allay the researcher’s own worries beforehand. The researcher too must choose a space with good reception and check that the recording equipment is working properly.

During the interviews, we found that verbalization was important for communicating the reason for silences (e.g., taking notes or giving time for the participant to continue talking). Communicating responses was also important (e.g., saying ‘please continue’, ‘do you need to take a break’, or giving short summaries of what had been said). In addition, the tone of voice was found to be another important tool for conveying interest and understanding, as well as establishing confidence. Further, we found that asking participants about their experience of being interviewed over the telephone was a good way of ending the interview, which primarily was about their experiences of being on sick leave. This smoothly closed the main story, allowed the participants to be brought back to the present and gave them the power of being experts in their own experience of the interview situation.

After the interviews, we found it important to gather our own reflections and experience of the interview by writing summaries of our overall impressions and making field notes about our experience of the interviewing situation as well as the main findings in relation to the questions asked. These field notes were valuable tools for evaluating or supplementing the data and they were used as data for the researcher’s reflections in the findings [ 43 ]. As we did not have to spend any time traveling to or from the interviews, we were able to carry out this post-interview part of the procedure more effectively, directly after the interview. Completing the interviews from home or the workplace for us as researchers also meant that we could secure the data in an effective way, i.e., we could save the recording in a secure manner immediately after the interview was over.

5. Methodological Considerations

There are a lack of methodological studies which investigate the use of telephone interviews with individuals with CMD and/or multimorbidity, where this study contributes to the gap in the literature. The strategic sampling of participants, with a diversity in demographic characteristics and viewpoints, facilitates the provision of a rich data set [ 54 ]. Yet, transferability of findings from qualitative studies may be limited to other groups or settings. To allow for judgment of transferability to other groups or setting, the authors strived to provide detailed descriptions of study design and clear communication of the findings. Although some of the findings are specifically related to the participants symptoms from their CMDs and/or multimorbidity, they may also be transferable to other groups which may not have a diagnosis but do experience the same type of symptoms or difficulties.

A limitation with the study is that the participants in general did not have experience of in-person or internet-based research interviews and that we did not have a comparison group who conducted the interviews in person or via internet-based option. However, as our purpose was not to compare the different formats but rather to gather knowledge on the experience of the telephone interviews from the perspective of participants, this was also beyond our scope. One might also want to consider how the presence of a third person during the interviews could have constrained the participants’ responses; however, we do not have information about the presence of other people, besides children being present during the interviews. Furthermore, in cases where the participants were in public, we rescheduled interviews to a better suited time and setting.

6. Conclusions

To conclude, telephone interviews are a method with both advantages and challenges. They provide more anonymity which seem to have a positive effect on self-disclosure and emotional display, while making fewer demands of participants in terms of emotion work and social responsibility. However, the shift from nonverbal to the audible put higher demands on the use of voice and require more intense listening on both parts. Worries about the quality of the interview due to difficulties with technology and sound or disturbances in the environment are also challenges presented as well as the loss of human encounter. Using telephone interviews as a means of qualitative data collection balance the power relationship between the interviewer and the interviewee, which can be demanding for the interviewer but beneficial for those being interviewed. The advantages, which were deemed as more important than the challenges, may give a certain group of individuals (e.g., those with CMDs or multimorbidity) a fairer opportunity to participate in research projects and share their experiences. Telephone interviews can be regarded as a valuable first option if the purpose of the study is not to build a relationship over time or observe visual cues, but rather about how people experience their lives.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the participants for sharing their stories with us.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A., E.S., V.S., L.H. and E.B.B.; methodology, A.A., E.S., V.S. and E.B.B.; validation, A.A., E.S., V.S., L.H. and E.B.B.; formal analysis, A.A., E.S., V.S., L.H. and E.B.B.; investigation, A.A., E.S., V.S., L.H. and E.B.B.; resources, V.S., L.H. and E.B.B.; data curation, A.A., E.S., V.S., L.H. and E.B.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.; writing—review and editing, A.A., E.S., V.S., L.H. and E.B.B.; supervision, V.S. and E.B.B.; project administration, V.S. and E.B.B.; funding acquisition, V.S., L.H. and E.B.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research was financially supported by grants from The Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE) (Grant No. 2018-01252), AFA-Insurance (Dnr. 199221), and The Kamprad Family Foundation (Reference No 20190271).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in the present study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Swedish Ethical Review Authority and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The projects included in the present study were approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (No 2020-00403; 2020-02462; 496-17, amendment T039-18).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The written consent included publication of anonymized responses.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

How to conduct qualitative interviews (tips and best practices)

Last updated

18 May 2023

Reviewed by

Miroslav Damyanov

However, conducting qualitative interviews can be challenging, even for seasoned researchers. Poorly conducted interviews can lead to inaccurate or incomplete data, significantly compromising the validity and reliability of your research findings.

When planning to conduct qualitative interviews, you must adequately prepare yourself to get the most out of your data. Fortunately, there are specific tips and best practices that can help you conduct qualitative interviews effectively.

- What is a qualitative interview?

A qualitative interview is a research technique used to gather in-depth information about people's experiences, attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions. Unlike a structured questionnaire or survey, a qualitative interview is a flexible, conversational approach that allows the interviewer to delve into the interviewee's responses and explore their insights and experiences.

In a qualitative interview, the researcher typically develops a set of open-ended questions that provide a framework for the conversation. However, the interviewer can also adapt to the interviewee's responses and ask follow-up questions to understand their experiences and views better.

- How to conduct interviews in qualitative research

Conducting interviews involves a well-planned and deliberate process to collect accurate and valid data.

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to conduct interviews in qualitative research, broken down into three stages:

1. Before the interview

The first step in conducting a qualitative interview is determining your research question . This will help you identify the type of participants you need to recruit . Once you have your research question, you can start recruiting participants by identifying potential candidates and contacting them to gauge their interest in participating in the study.

After that, it's time to develop your interview questions. These should be open-ended questions that will elicit detailed responses from participants. You'll also need to get consent from the participants, ideally in writing, to ensure that they understand the purpose of the study and their rights as participants. Finally, choose a comfortable and private location to conduct the interview and prepare the interview guide.

2. During the interview

Start by introducing yourself and explaining the purpose of the study. Establish a rapport by putting the participants at ease and making them feel comfortable. Use the interview guide to ask the questions, but be flexible and ask follow-up questions to gain more insight into the participants' responses.

Take notes during the interview, and ask permission to record the interview for transcription purposes. Be mindful of the time, and cover all the questions in the interview guide.

3. After the interview

Once the interview is over, transcribe the interview if you recorded it. If you took notes, review and organize them to make sure you capture all the important information. Then, analyze the data you collected by identifying common themes and patterns. Use the findings to answer your research question.

Finally, debrief with the participants to thank them for their time, provide feedback on the study, and answer any questions they may have.

Free AI content analysis generator

Make sense of your research by automatically summarizing key takeaways through our free content analysis tool.

- What kinds of questions should you ask in a qualitative interview?

Qualitative interviews involve asking questions that encourage participants to share their experiences, opinions, and perspectives on a particular topic. These questions are designed to elicit detailed and nuanced responses rather than simple yes or no answers.

Effective questions in a qualitative interview are generally open-ended and non-leading. They avoid presuppositions or assumptions about the participant's experience and allow them to share their views in their own words.

In customer research , you might ask questions such as:

What motivated you to choose our product/service over our competitors?

How did you first learn about our product/service?

Can you walk me through your experience with our product/service?

What improvements or changes would you suggest for our product/service?

Have you recommended our product/service to others, and if so, why?

The key is to ask questions relevant to the research topic and allow participants to share their experiences meaningfully and informally.

- How to determine the right qualitative interview participants

Choosing the right participants for a qualitative interview is a crucial step in ensuring the success and validity of the research . You need to consider several factors to determine the right participants for a qualitative interview. These may include:

Relevant experiences : Participants should have experiences related to the research topic that can provide valuable insights.

Diversity : Aim to include diverse participants to ensure the study's findings are representative and inclusive.

Access : Identify participants who are accessible and willing to participate in the study.

Informed consent : Participants should be fully informed about the study's purpose, methods, and potential risks and benefits and be allowed to provide informed consent.

You can use various recruitment methods, such as posting ads in relevant forums, contacting community organizations or social media groups, or using purposive sampling to identify participants who meet specific criteria.

- How to make qualitative interview subjects comfortable

Making participants comfortable during a qualitative interview is essential to obtain rich, detailed data. Participants are more likely to share their experiences openly when they feel at ease and not judged.

Here are some ways to make interview subjects comfortable:

Explain the purpose of the study

Start the interview by explaining the research topic and its importance. The goal is to give participants a sense of what to expect.

Create a comfortable environment

Conduct the interview in a quiet, private space where the participant feels comfortable. Turn off any unnecessary electronics that can create distractions. Ensure your equipment works well ahead of time. Arrive at the interview on time. If you conduct a remote interview, turn on your camera and mute all notetakers and observers.

Build rapport

Greet the participant warmly and introduce yourself. Show interest in their responses and thank them for their time.

Use open-ended questions

Ask questions that encourage participants to elaborate on their thoughts and experiences.

Listen attentively

Resist the urge to multitask . Pay attention to the participant's responses, nod your head, or make supportive comments to show you’re interested in their answers. Avoid interrupting them.

Avoid judgment

Show respect and don't judge the participant's views or experiences. Allow the participant to speak freely without feeling judged or ridiculed.

Offer breaks

If needed, offer breaks during the interview, especially if the topic is sensitive or emotional.

Creating a comfortable environment and establishing rapport with the participant fosters an atmosphere of trust and encourages open communication. This helps participants feel at ease and willing to share their experiences.

- How to analyze a qualitative interview

Analyzing a qualitative interview involves a systematic process of examining the data collected to identify patterns, themes, and meanings that emerge from the responses.

Here are some steps on how to analyze a qualitative interview:

1. Transcription

The first step is transcribing the interview into text format to have a written record of the conversation. This step is essential to ensure that you can refer back to the interview data and identify the important aspects of the interview.

2. Data reduction

Once you’ve transcribed the interview, read through it to identify key themes, patterns, and phrases emerging from the data. This process involves reducing the data into more manageable pieces you can easily analyze.

The next step is to code the data by labeling sections of the text with descriptive words or phrases that reflect the data's content. Coding helps identify key themes and patterns from the interview data.

4. Categorization

After coding, you should group the codes into categories based on their similarities. This process helps to identify overarching themes or sub-themes that emerge from the data.

5. Interpretation

You should then interpret the themes and sub-themes by identifying relationships, contradictions, and meanings that emerge from the data. Interpretation involves analyzing the themes in the context of the research question .

6. Comparison

The next step is comparing the data across participants or groups to identify similarities and differences. This step helps to ensure that the findings aren’t just specific to one participant but can be generalized to the wider population.

7. Triangulation

To ensure the findings are valid and reliable, you should use triangulation by comparing the findings with other sources, such as observations or interview data.

8. Synthesis

The final step is synthesizing the findings by summarizing the key themes and presenting them clearly and concisely. This step involves writing a report that presents the findings in a way that is easy to understand, using quotes and examples from the interview data to illustrate the themes.

- Tips for transcribing a qualitative interview

Transcribing a qualitative interview is a crucial step in the research process. It involves converting the audio or video recording of the interview into written text.

Here are some tips for transcribing a qualitative interview:

Use transcription software

Transcription software can save time and increase accuracy by automatically transcribing audio or video recordings.

Listen carefully

When manually transcribing, listen carefully to the recording to ensure clarity. Pause and rewind the recording as necessary.

Use appropriate formatting

Use a consistent format for transcribing, such as marking pauses, overlaps, and interruptions. Indicate non-verbal cues such as laughter, sighs, or changes in tone.

Edit for clarity

Edit the transcription to ensure clarity and readability. Use standard grammar and punctuation, correct misspellings, and remove filler words like "um" and "ah."

Proofread and edit

Verify the accuracy of the transcription by listening to the recording again and reviewing the notes taken during the interview.

Use timestamps

Add timestamps to the transcription to reference specific interview sections.

Transcribing a qualitative interview can be time-consuming, but it’s essential to ensure the accuracy of the data collected. Following these tips can produce high-quality transcriptions useful for analysis and reporting.

- Why are interview techniques in qualitative research effective?

Unlike quantitative research methods, which rely on numerical data, qualitative research seeks to understand the richness and complexity of human experiences and perspectives.

Interview techniques involve asking open-ended questions that allow participants to express their views and share their stories in their own words. This approach can help researchers to uncover unexpected or surprising insights that may not have been discovered through other research methods.

Interview techniques also allow researchers to establish rapport with participants, creating a comfortable and safe space for them to share their experiences. This can lead to a deeper level of trust and candor, leading to more honest and authentic responses.

- What are the weaknesses of qualitative interviews?

Qualitative interviews are an excellent research approach when used properly, but they have their drawbacks.

The weaknesses of qualitative interviews include the following:

Subjectivity and personal biases

Qualitative interviews rely on the researcher's interpretation of the interviewee's responses. The researcher's biases or preconceptions can affect how the questions are framed and how the responses are interpreted, which can influence results.

Small sample size

The sample size in qualitative interviews is often small, which can limit the generalizability of the results to the larger population.

Data quality

The quality of data collected during interviews can be affected by various factors, such as the interviewee's mood, the setting of the interview, and the interviewer's skills and experience.

Socially desirable responses

Interviewees may provide responses that they believe are socially acceptable rather than truthful or genuine.

Conducting qualitative interviews can be expensive, especially if the researcher must travel to different locations to conduct the interviews.

Time-consuming

The data analysis process can be time-consuming and labor-intensive, as researchers need to transcribe and analyze the data manually.

Despite these weaknesses, qualitative interviews remain a valuable research tool . You can take steps to mitigate the impact of these weaknesses by incorporating the perspectives of other researchers or participants in the analysis process, using multiple data sources , and critically analyzing your biases and assumptions.

Mastering the art of qualitative interviews is an essential skill for businesses looking to gain deep insights into their customers' needs , preferences, and behaviors. By following the tips and best practices outlined in this article, you can conduct interviews that provide you with rich data that you can use to make informed decisions about your products, services, and marketing strategies.

Remember that effective communication, active listening, and proper analysis are critical components of successful qualitative interviews. By incorporating these practices into your customer research, you can gain a competitive edge and build stronger customer relationships.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 11 January 2024

Last updated: 15 January 2024

Last updated: 17 January 2024

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 12 May 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

Telephone Interviewing as a Qualitative Methodology for Researching Cyberinfrastructure and Virtual Organizations

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 10 October 2019

- Cite this reference work entry

- Kerk F. Kee 4 &

- Andrew R. Schrock 4

2053 Accesses

7 Citations

Cyberinfrastructure (CI) involves networked technologies, organizational practices, and human workers that enable computationally intensive, data-driven, and multidisciplinary collaborations on large-scale scientific problems. CI enables emerging forms of mediated relationships, dispersed groups, virtual organizations, and distributed communities. Researchers of CI often employ a limited set of methodologies such as trace data analysis and ethnography. In response, this chapter proposes a more flexible framework of interviewing members of dispersed groups, virtual organizations, and distributed communities whose work, interaction, and communication are primarily mediated by communication technologies. Telephone interviewing can yield high-quality data under appropriate conditions, making it a productive mode of data collection comparable to a face-to-face mode. The protocol described in this chapter for telephone interviews has been refined over three studies (total N = 236) and 10 years (2007–2017) of research. The protocol has been shown to be a flexible and effective way to collect qualitative data on practices, networks, projects, and biographical histories in the virtual CI communities under study. These benefits speak to a need in CI research to expand from case studies and sited ethnographies. Telephone interviewing is a valuable addition to the growing literature on CI methodologies. Furthermore, our framework can be used as a pedagogical tool for training students interested in qualitative research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Atkins DE et al (2003) Revolutionizing science and engineering through cyberinfrastructure: report of the National Science Foundation Blue-Ribbon Advisory Panel on cyberinfrastructure. National Science Foundation, Washington, DC

Google Scholar

Baxter LA, Babbie ER (2003) The basics of communication research. Wadsworth, Belmont

Berry JM (2002) Validity and reliability issues in elite interviewing. PS 35:679–682

Browning LD, Morris GH, Kee KF (2011) The role of communication in positive organizational scholarship. In: Cameron KS, Spreitzer GM (eds) Oxford handbook of positive organizational scholarship. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

Brummans BH (2014) Pathways to mindful qualitative organizational communication research. Manag Commun Q 28:440–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318914535286

Article Google Scholar

Chen L (1997) Verbal adaptive strategies in US American dyadic interactions with US American or East-Asian partners. Commun Monogr 64:302–323