Five Research-Based Ways to Teach Vocabulary

Did you know that typically, only 5% to 10% of instructional time is devoted to vocabulary instruction, yet students, especially struggling students and English learners (ELs), need between 12 and 14 exposures to words and their meanings to fully learn them (Durkin, 1978/79; Roser & Juel, 1982; Scott, Jamieson, Noel, & Asslin, 2003)? Teaching the meanings of important words before learning new content activates students’ background knowledge and prepares them for learning and comprehending. In other words, teaching vocabulary provides the “Velcro” for new information to “stick to.”

What Research Says About Effective Vocabulary Instruction

Vocabulary instruction must be explicit . Explicit vocabulary instruction includes an easy-to-understand definition presented directly to students along with multiple examples and nonexamples of the target word, brief discussion opportunities, and checks for understanding.

Vocabulary instruction must include multiple practice opportunities for using words within and across subjects . That is, instruction must be extended over time with opportunities for students to hear, speak, read, and write words in various contexts. This builds students’ breadth and depth of vocabulary knowledge.

Vocabulary should be taught schoolwide and across all subject areas . Each subject has a unique set of vocabulary terms, and students need to know their meanings and how to use them in various contexts.

Word Selection

Instructional time is precious, and teachers are not able to address every unknown word students might encounter, so careful word selection is key . When deciding which words to target for explicit instruction, consider words that are

- essential to understanding the main idea of the text or unit,

- used repeatedly or frequently encountered across domains, and

- not part of students’ prior knowledge.

ELs may require even more careful word selection and extensive vocabulary instruction because they may be learning conversational language and academic language at the same time. Colorín Colorado provides additional information about selecting vocabulary words to teach ELs .

Some of Our Favorite Vocabulary Instructional Activities for ALL Content Areas

The five activities described below are effective ways to teach vocabulary for all students, but especially for struggling students, students with learning disabilities, and ELs.

1. Essential Words Routine

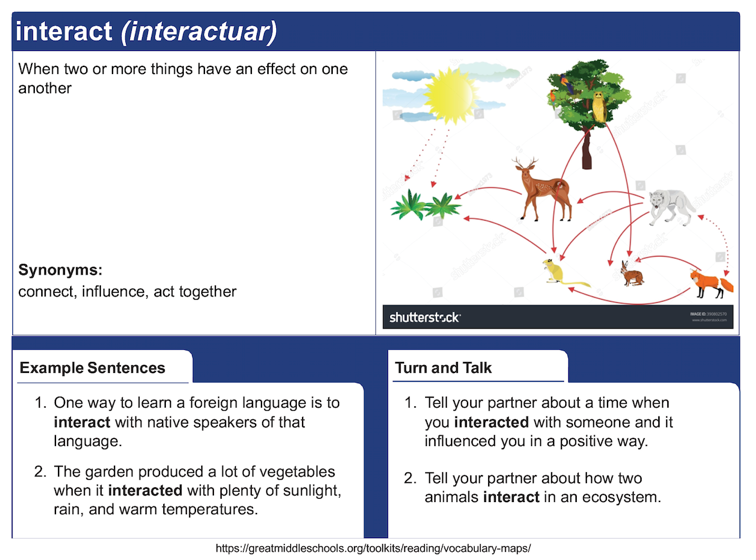

Teachers use a simple graphic organizer to preteach the meanings of important words in about 5 minutes per word. During this routine, teachers introduce target words with definitions, visual cues, and examples. Students engage in immediate practice using the words through collaborative student turn-and-talk activities.

- Vocabulary Maps Toolkit from Middle School Matters

- Reading Instruction for Middle School Students: Developing Lessons for Improving Comprehension (see page 11)

2. Frayer Model

One way to have students extend their knowledge of important words is through a Frayer model. This graphic organizer builds vocabulary and conceptual knowledge across content areas. The strategy requires students (not the teacher) to define a vocabulary word and then list its characteristics, examples, and nonexamples. Frayer models can be completed in collaborative groups using textbooks and other subject-matter materials while the teacher circulates around the classroom and assists students.

Online module, examples, and templates from the IRIS Center

3. Semantic Mapping

Semantic maps visually display and connect a word or phrase and a set of related words or concepts. Implementing semantic map activities in your classroom will help students, especially struggling students and students with learning disabilities, recall the meanings of words and understand how multiple words or concepts “fit together.” Teachers will find that using a semantic map, combined with explicit instruction and practice opportunities, is an effective way of expanding students’ vocabulary and supporting their content knowledge.

- Introduction to semantic maps and sample lesson plans from the Developers of PowerUp What Works

- Semantic mapping teaching strategy guide from PowerUp What Works

4. Vocabulary Review Activities

Multiple opportunities to practice using new words is an important part of vocabulary instruction. In previous TCLD research studies, brief review activities were built into novel unit lesson plans to help students practice (and remember) the meanings of important words. Each of these activities takes 5 to 10 minutes and is easy to prepare.

- Partner Review Routine: Partners work together to quickly review words learned the previous day.

- Sentence Review Routine: Partners create sentences using words assigned by the teacher.

- Examples and Nonexamples: The teacher tells students scenarios or shows pictures and students respond chorally to each scenario, indicating whether it is an example or nonexample.

- What Word Fits? The teacher asks a question and student partners hold up an index card with the word that fits or answers the question.

Each activity is described in more detail beginning on page 33 of the TCLD booklet Reading Instruction for Middle School Students: Developing Lessons for Improving Comprehension

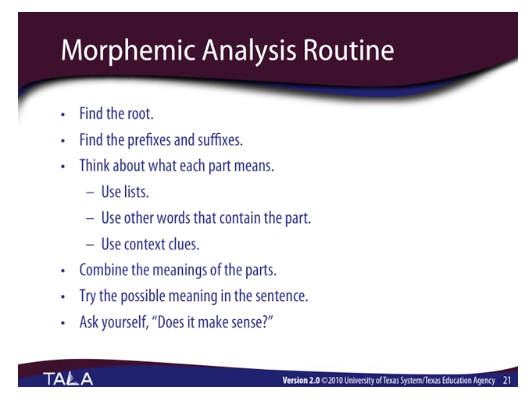

5. Morphemic Analysis Routine

Explicit instruction of words is important, but it is impossible to teach all the unfamiliar words students will encounter. One way to help students develop strategies for approaching unfamiliar vocabulary is to teach morphemes (prefixes, roots, and suffixes). Students can be taught the following morphemic analysis routine to help them engage in independent word study.

Learn more about the morphemic analysis routine by reviewing this online learning module from the Texas Adolescent Literacy Academies.

Have questions? Feel free to drop us a line !

Current Perspectives on Vocabulary Teaching and Learning

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 29 November 2018

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Samuel Barclay 2 &

- Norbert Schmitt 3

Part of the book series: Springer International Handbooks of Education ((SIHE))

1557 Accesses

2 Citations

This chapter reviews key vocabulary research and draws a number of conclusions regarding teaching and learning. Areas addressed include the amount of vocabulary required to use English; what it means to know and learn a word; the incremental nature of vocabulary acquisition; the role of memory in vocabulary learning, incidental, and intentional vocabulary learning; and the implementation of a systematic approach to vocabulary teaching and learning. This chapter also introduces principles by which activities can be developed for vocabulary teaching and instruments that will help teachers choose effective tasks. The insights and techniques discussed in this chapter can help teachers develop principled vocabulary programs for their students.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Al-Homoud F, Schmitt N (2009) Extensive reading in a challenging environment: a comparison of extensive and intensive reading approaches in Saudi Arabia. Lang Teach Res 13(4):383–401

Article Google Scholar

Baddeley AD (1990) Human memory and theory and practice. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hove

Google Scholar

Bahns J, Eldaw M (1993) Should we teach EFL students collocations? System 21(1):101–114

Barclay S (2017) The effect of word class and word length on the decay of lexical knowledge. In: Paper presented at the AAAL, Portland

Barcroft J (2002) Semantic and structural elaboration in L2 lexical acquisition. Lang Learn 52(2):323–363

Barcroft J (2015) Lexical input processing and vocabulary learning. John Benjamins, Amsterdam

Book Google Scholar

Bot K d, Stoessel S (2000) In search of yesterday’s words: reactivating a long-forgotten language. Appl Linguis 21(3):333–353

Chen C, Truscott J (2010) The effects of repetition and L1 lexicalization on incidental vocabulary acquisition. Appl Linguis 31(5):693–713. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amq031

Crothers E, Suppes P (1967) Experiments in second-language learning. Academic Press, New York

Dang TNY, Webb S (2014) The lexical profile of academic spoken English. Engl Specif Purp 33:66–76

Dang TNY, Webb S (2016) Making an essential word list. In: Nation ISP (ed) Making and using word lists for language learning and testing. John Benjamins, Amsterdam

Ebbinghaus H (1885) Über das Gedchtnis. Untersuchungen zur experimentellen Psychologie. Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig

Ellis NC, Beaton A (1993) Psycholinguistic determinants of foreign language vocabulary learning. Lang Learn 43(4):559–617

Fitzpatrick T (2012) Tracking the changes: vocabulary acquisition in the study abroad context. The Language Learning Journal 40(1):81–98

Fitzpatrick T, Clenton J (2010) The challenge of validation: assessing the performance of a test of productive vocabulary. Lang Test 27(4):537–554

Gardner D, Davies M (2014) A new academic vocabulary list. Appl Linguis 35(3):305–327

Garnier M, Schmitt N (2015) The PHaVE list: a pedagogical list of phrasal verbs and their most frequent meaning senses. Lang Teach Res 19(6):645–666

González-Fernández B, Schmitt N (in press) Word knowledge: exploring the relationships and order of acquisition of vocabulary knowledge components. Applied Linguistics

Goulden R, Nation P, Read J (1990) How large can a receptive vocabulary be? Appl Linguis 11(4):341–363

Hu M, Nation ISP (2000) Vocabulary density and reading comprehension. Read Foreign Lang 13(1):403–430

Ishii T (2014) Semantic connection or visual connection: investigating the true source of confusion. Lang Teach Res 19(6):712–722. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168814559799

Laufer B (1989) What percentage of text lexis is essential for comprehension. In: Lauren C, Nordman M (eds) Special language: from humans thinking to thinking machines. Multilingual Matters, Clevedon, pp 316–323

Laufer B (1997) What’s in a word that makes it hard or easy? Intralexical factors affecting the difficult of vocabulary acquisition. In: Schmitt N, McCarthy M (eds) Vocabulary: description, acquisition, and pedagogy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 140–155

Laufer B, Goldstein Z (2004) Testing vocabulary knowledge: size, strength, and computer adaptiveness. Lang Learn 54(3):399–436

Laufer B, Hulstijn, J (2001) Incidental vocabulary acquisition in a second language: the construct of task-induced involvement. Applied Linguistics 22 (1):1–26

Laufer B, Ravenhorst-Kalovski GC (2010) Lexical threshold revisited: lexical text coverage, learners’ vocabulary size and reading comprehension. Read Foreign Lang 22(1):15–30

Laufer B, Shmueli K (1997) Memorizing new words: does teaching have anything to do with it? RELC J 28(1):89–107

Le-Thi D, Rodgers M, Pellicer-Sanchez A (2017) Teaching formulaic sequences in an English-language class: the effects of explicit instruction versus coursebook instruction. TESL Canada J. 34(3): 111–139

Macis M (2018) Incidental learning of figurative language from a semi-authentic novel: three case studies. Read Foreign Lang. 30(1): 48–75

Martinez R, Murphy VA (2011) Effect of frequency and idiomaticity on second language reading comprehension. TESOL Q 45(2):267–290

McLean S, Rouault G (2017) The effectiveness and efficiency of extensive reading at developing reading rates. System 70:92–106

Montero-Perez M, Peters E, Desmet P (2017) Vocabulary learning through viewing video: the effect of two enhancement techniques. Comput Assist Lang Learn 31(1-2): 1–26

Nakata T (2015) Effects of expanding and equal spacing on second language vocabulary learning: does gradually increasing spacing increase vocabulary learning? Stud Second Lang Acquis 37:677–711. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263114000825

Nakata T (2016) Does repeated practice make perfect? the effects of within-session repeated retrieval on second language vocabulary learning. Stud Second Lang Acquis 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263116000280

Nation ISP (1990) Teaching and learning vocabulary. Heinle and Heinle, Boston

Nation P (1995) The word on words: an interview with Paul Nation [Interviewed by Norbert Schmitt]. Lang Teach 19(2):5–7

Nation ISP (2006) How large a vocabulary is needed for reading and listening. Can Mod Lang Rev 63(1):59–82

Nation P (2007) The four strands. Innov Lang Learn Teach 1(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.2167/illt039.0

Nation P (2008) Teaching vocabulary: strategies and techniques. Heinle, Boston

Nation ISP (2013) Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Nation ISP, Beglar D (2007) A vocabulary size test. Lang Teach 31(7):9–13

Nation P, Meara P (2002) Vocabulary. In: Schmitt N (ed) An introduction to applied linguistics. Arnold, London, pp 35–54

Nation ISP, Webb S (2011) Researching and analyzing vocabulary. Heinle, Cengage Learning, Boston

Pawley A, Syder FH (1983) Two puzzles for linguistic theory: nativelike selection and nativelike fluency. In: Richards J, Schmidt R (eds) Language and communication, pp 191–225

Pellicer-Sanchez A, Schmitt N (2010) Incidental vocabulary acquisition from an authentic novel: do things fall apart? Read Foreign Lang 22(1):31–55

Peters E (2014) The effects of repetition and time of post-test administration on EFL learners’ form recall of single words and collocations. Lang Teach Res 18(1):75–94

Peters E (2017) The effect of out-of-class exposure on learners’ vocabulary size. In: Paper presented at the AAAL 2017, Portland

Peters E, Heynen E, Puimège E (2016) Learning vocabulary through audiovisual input: the differential effect of L1 subtitles and captions. System 63:134–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2016.10.002

Rodgers MPH (2013) English language learning through viewing television: an investigation of comprehension, incidental vocabulary acquisition, lexical coverage, attitudes, and captions . (PhD), Victoria University of Wellington

Schmitt N (1998) Tracking the incremental acquisition of second language vocabulary: a longitudinal study. Lang Learn 48(2):281–317

Schmitt N (2008) Instructed second language vocabulary learning. Lang Teach Res 12(3):329–363

Schmitt N (2014) Size and depth of vocabulary knowledge: what the research shows. Lang Learn 64(4):913–951

Schmitt N, Schmitt D (2014) A reassessment of frequency and vocabulary size in L2 vocabulary teaching. Lang Teach 47(4):484–503

Schmitt N, Zimmerman C (2002) Derivative word forms: what do learners know? TESOL Q 36(2):145–171

Schmitt N, Jiang X, Grabe W (2011) The percentage of words known in a text and reading comprehension. Mod Lang J 95(1):26–43

Snellings P, van Gelderen A, de Glopper K (2002) Lexical retrieval: an aspect of fluent second language production that can be enhanced. Lang Learn 52:723–754

Steinel MP, Hulstijn J, Steinel W (2007) Second language idiom learning in a paired-associate paradigm. Stud Second Lang Acquis 29(3):449–484

Tinkham T (1997) The effects of semantic and thematic clustering on the learning of second language vocabulary. Second Lang Res 13(2):138–163. https://doi.org/10.1191/026765897672376469

van Zeeland H, Schmitt N (2013) Lexical coverage in l1 and l2 listening comprehension: the same or different from reading comprehension? Appl Linguis 34(4):457–479

Webb S (2007a) The effects of repetition on vocabulary knowledge. Appl Linguis 28(1):46–65

Webb S (2007b) Learning word pairs and glossed sentences: the effects of single context on vocabulary knowledge. Lang Teach Res 11(1):63–81

Webb S, Kagimoto E (2009) The effects of vocabulary learning on collocation and meaning. TESOL Q 43(1):55–77

Webb S, Nation P (2017) How vocabulary is learned. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Webb S, Rodgers M (2009) Vocabulary demands of television programmes. Lang Learn 59(2):335–366

West M (1953) A general service list of English words. Longman, Green & Co, London

Willis M, Ohashi Y (2012) A model of L2 vocabulary learning and retention. Lang Learn J 40(1):125–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2012.658232

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK

Samuel Barclay

The University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK

Norbert Schmitt

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Samuel Barclay .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

The University of Hong Kong , Hong Kong SAR, Hong Kong

Xuesong Gao

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Barclay, S., Schmitt, N. (2019). Current Perspectives on Vocabulary Teaching and Learning. In: Gao, X. (eds) Second Handbook of English Language Teaching. Springer International Handbooks of Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58542-0_42-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58542-0_42-1

Received : 21 August 2018

Accepted : 21 August 2018

Published : 29 November 2018

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-58542-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-58542-0

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Education Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Education

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch

Effective Vocabulary Instruction Fosters Knowing Words, Using Words, and Understanding How Words Work

Margaret g. mckeown.

a Department of Instruction and Learning, University of Pittsburgh, PA, Emerita

This clinical focus article will highlight the importance of vocabulary instruction, in particular, thinking about instruction in terms of focusing students' attention on words and their uses. Vocabulary knowledge that supports literacy and academic learning is extensive and multidimensional. Many learners accumulate high-quality vocabulary knowledge independently, through wide reading and rich language environments that provide abundant practice with words and language forms. However, instruction in vocabulary provides a more efficient way of getting that job done, especially for learners who are less likely to be experiencing rich language interactions, for example, because they struggle with reading and do little of it on their own.

Three aspects of vocabulary instruction, choosing words to teach, the inclusion of morphological information, and the importance of engaging students in interactions around words, will be explored. Considerations in choosing words include their role in the language and their utility to students. Morphology will be discussed in terms of using Latin roots in instruction as a resource for unlocking new word meanings and a framework for understanding language.

Effective instruction means bringing students' attention to words in ways that promote not just knowing word meanings but also understanding how words work and how to utilize word knowledge effectively.

How many words do you know? You deal with an abundance of words every day, comfortably and fluently. You are breezing along in this text right now with hardly a thought to what you know about each word. However, you have no idea, no way of knowing, just how many words you know. So many words are available to us to process with ease, yet an accounting of those words is beyond our reach. This illustrates why it is hard to get a handle on the role and importance of vocabulary learning. Just as the extent and depth of one's knowledge remains elusive, it is hard to understand the extent and depth of knowledge that needs to be acquired by students for them to experience literacy and academic success. Learning—and teaching—vocabulary is a bit of a stealthy process.

The most obvious aspect of a word's meaning is its definition. However, knowing a definition is by no means the essence of word knowledge. A rich variety of information is needed about each word in order to support high-quality literacy and academic learning. Useful theoretical perspectives on word knowledge have been offered by many scholars (e.g., McKeown, Deane, Scott, Krovetz, & Lawless, 2017 ; Nagy & Scott, 2000 ; Perfetti, 2007 ). The emphases in their perspectives differ, but three key characteristics are clear in all three:

- There are many aspects to know about a word, including features of its meaning, situations in which it is used, associations with other words, and how it behaves syntactically in context.

- Words are polysemous; their meanings are not static but shift according to context. These shifts may be large or subtle; for example, accommodate can mean physically providing room for someone and providing for someone's need or request, or it can take a more metaphorical sense of being able to understand a new idea that may challenge your perspective.

- Word knowledge is incremental, gradually developing over multiple encounters.

Given the complex nature of word knowledge, learners need to develop knowledge that allows them to access meaning rapidly when reading and to use that meaning to make sense of the various contexts in which a word might be encountered. Rapid access to word meanings that are relevant to a given context is necessary to keep comprehension from slowing down and eventually breaking down. Making sense of the range of contexts in which any word might appear requires flexible knowledge that can adapt to different uses of words.

Many learners accumulate high-quality vocabulary knowledge independently, mainly through extensive reading and rich language environments that provide abundant practice with words and language forms. However, instruction in vocabulary provides a more efficient way of getting that job done. A more efficient route to vocabulary knowledge is especially critical for learners who are less likely to be experiencing rich language interactions, for example, because they struggle with reading and do little of it on their own. Lack of adequate vocabulary knowledge can too easily cause these students to be left behind in developing literacy, and many of them will never catch up. The consequence is that a great deal of individual and societal potential goes unrealized.

However, all students can benefit from high-quality vocabulary instruction. Even students who have a large vocabulary repertoire can enrich their knowledge in ways that make it more accessible and productive. For example, it is well accepted that words can be known to different levels of knowledge. As Carey (1978) pointed out in her seminal research on fast and extended mapping of word knowledge, every learner is working on as many as 1,600 word meanings that are in various stages of being known. It seems reasonable that instructional interactions around language can have benefits for a range of learners, even though the words being learned and the pace at which learning accumulates vary for different learners. Instruction may be initiating knowledge for some learners, whereas it may be reinforcing, clarifying, and extending knowledge for others.

As educators take on the responsibility of teaching vocabulary, issues of how to proceed center on which words to teach and the nature of the instruction. This clinical focus article first focuses on selecting which words to teach, based on their utility and role in the language. The focus then turns to an aspect of language that is both a feature of words and a potential aspect of instruction, morphology, which is the structure of words and word parts. The third focus of the clinical focus article is the nature of vocabulary instruction itself, in particular, features that make instruction most effective.

Which Words to Teach?

A starting point in considering which words merit instructional attention is the nature of the English language. Language is a dynamic human creation and, thus, inherently a bit of a mess.

Ancestry of English

English, even more than most other languages, is a mishmash, because of historical influences on how the language developed into the English we know today. English began as a Germanic language, Anglo-Saxon or Old English. However, this early language mingled with other languages, with the biggest influence being Latin. Latin influenced English over centuries, either directly or through other Romance languages, especially French. The greatest influence began with the Norman conquest of 1066, which brought French, as spoken by the upper classes, and Latin as the language of books and official documents. In fact, English mingled with Latinate vocabulary to such an extent that modern English seems as much a Romance language as a Germanic language, as far as its word-stock ( Baugh & Cable, 1978 ).

The Germanic versus Latinate divide is significant in how our language is used. The Germanic segment of our word-stock mainly consists of simple, concrete words that typify oral, conversational language. The Latinate portion includes more abstract words that characterize more academic language as found in texts. Of course, the common, high-frequency words are found in text as well. In fact, they make up the majority of words found there. However, the portion of words that particularly characterize text is key to comprehending text. Those words carry the semantic burden in written language.

Consider, for example, the text segment below from the New York Times ( Casey & Escobar, 2018 ). In this 49-word segment, the majority—about 38—of the words are high frequency. Yet, without the lower frequency, italicized, and bolded words, it would be difficult to make sense of this passage. The italicized words are considered academic words; the bolded words are more common, but are used here in a metaphorical sense:

“The peace accords …were meant to bring an end to five decades of fighting that left at least 220,000 dead. Behind the agreement, though, loomed a fear: That many of the thousands of fighters granted amnesty might sour on civilian life and pick up arms again.” (NY Times, Sept 19, 2018; front page)

The divide between conversational and written aspects of English has been labeled the lexical bar ( Corson, 1985 , 1995 ). Corson emphasizes the need for learners to cross this lexical bar or move from using everyday language to mastering text language. This move can be difficult but is crucial to academic success. Crossing the lexical bar requires understanding and using sophisticated, literate vocabulary.

The divide between everyday words and the language of text was the starting point for the notion of word tiers ( Beck & McKeown, 1985 ; Beck, McKeown, & Kucan, 2002 , 2013 ). The concept originated when colleagues challenged our recommendations for direct vocabulary instruction, saying that there were too many words in the language to teach them all. We countered, saying that there was no need to teach all the words. We conceptualized a three-tier heuristic by considering that different words have different utility and roles in the language. Tier 1 words characterize everyday oral language, and children learn these readily when hearing them in context. Tier 3 includes words that tend to be limited to specific domains (e.g., chromosome) or extremely rare ( abecedarian ) and are best learned within their domains.

Tier 2 comprises words that are characteristic of written language (e.g., coherent, diminish, or eloquent) and not so common in conversation ( Hayes & Ahrens, 1988 ). These are words of high utility for literate language users. Tier 2 words overlap to a great extent with general academic words, that is, words that are common across various domains of academic texts. Good databases of academic words include Coxhead's (2000) Academic Word List (AWL) and Gardner and Davies' (2013 ) more recent Academic Vocabulary List. Each of these lists is based on a large corpus of words from sources such as academic journals and university textbooks across broad academic areas. A difference between academic words and Tier 2 words is that Tier 2 includes words from fiction, whereas academic words are drawn from nonfiction, disciplinary texts. Thus, Tier 2 includes words that typically apply to characters and emotions, such as sinister, mutter, and obsessed . We think these kinds of words are good candidates for instruction, for several reasons. They can help students read and enjoy fiction, they provide students with interesting words to use in describing people and human interactions in writing, and they are rather delicious and fun! Students enjoy, for example, imagining what sinister characters might do or demonstrating muttering versus murmuring.

Children typically have a rather small repertoire of Tier 2 words when they enter school but increase Tier 2 knowledge as they become readers. Tier 2 words are more difficult to learn than Tier 1 words, partly because they are less frequent in the language as a whole—thus the frequent repetition that aided learning Tier 1 words is gone—but also because written context in which Tier 2 words typically appear provides less information about a word's meaning than the immediate oral contexts in which Tier 1 words are found. Think of it this way: When children hear words spoken every day, they have the physical surroundings, gesture, intonation, and familiarity of their everyday life to support figuring out word meaning. However, when they read, or are read to, they have only other words to glean information from.

An important caveat about word tiers is that it is an imprecise concept. It was meant as a heuristic to help bound the selection of words to teach and also to draw attention to properties of words and their roles in the language that make some words more useful to know. Classrooms are typically inundated with words from the various curricular materials that teachers and students deal with. The tiers concept can support teachers in selecting from among that sea of words those words that are most beneficial to attend to and keep around. Tier 2 words are beneficial to learn because they are found in a variety of texts and can thus provide access to a range of contexts.

Yet, the fact that Tier 2 words can apply to varied contexts also means that these words have multiple related senses or nuances—they are polysemous. Negotiating these shades of meaning can be tricky for learners. A typical sticking point in learning vocabulary is that, when we learn a word, we initially learn a particular sense and then we tend to use that sense to understand subsequent contexts we meet. Thus, if we learn the word foundation as an organization that provides funding and then meet a context about people building a “foundation of friendship,” we might think it means an organization that provides funding for friendships.

Rampant polysemy is, then, another reason for giving students supported practice with using these kinds of words. By providing varied contexts and supportive interactions around them, students become able, for example, to understand that a student with academic potential is one who has the ability to be a good student and a merchant's potential customer is someone who might buy from them. Probing two such contexts also helps students to see that at the core of potential is a meaning of “possibility of becoming something in the future.” Word knowledge needs to become decontextualized—generalized beyond specific contexts—to provide the kind of flexibility learners will need as they meet words in new contexts.

As the above discussion of polysemy suggests, it is important to give attention to different senses or nuances of word meaning in instruction. However, it is not necessary to try to include every sense that a word might have—that could get way too confusing! Part of the reason for focusing on different senses is to help students build a general understanding that words can shift their meaning in different contexts and to understand the limits of that. The way my colleagues and I have handled polysemous senses is to provide a definition that describes the core concept of a word, which is broad enough to cover various senses. We employed these kinds of definitions in the middle school vocabulary program we developed called RAVE (Robust Academic Vocabulary Encounters; McKeown, Crosson, Beck, Sandora, & Artz, 2012 ). For example, the definition of approach applied to getting physically closer to something and a way to deal with or solve an issue: “If you approach something, you get closer to it in order to reach it or to deal with it.” Then, we presented contexts that used the word in both ways and asked students to explain what the context meant. So, for example, for a context such as “Our group had to come up with a new approach for our science project,” the teacher would guide students to understand that the group was trying to figure out a new way to create a science project.

It is important not to confuse polysemy, multiple senses or nuances of related meaning, with words that have multiple unrelated meanings. The latter are actually homographs, words that are spelled the same but with no similarity in meaning. Examples would be fast as in speed and fast as in to forego food. There is no reason to make a habit of introducing homographs of instructed words. That is likely to breed confusion. The only circumstances for introducing a homograph would be to avoid confusion with an already known word. So, for example, if fast , meaning to forego food, is being taught, mention that students probably already know fast as meaning a high rate of speed but that this is another word that sounds and looks the same and has a different meaning.

Consideration of Tier 2 words can provide a focus and a mindset, but it still may not make it easy to find and select precisely which words to teach. It can seem that there are, at once, too many words to choose from and not enough “really good words” to share with students. Which are the right ones? First of all, there is no definitive list of words that students must know. The best guide is to choose from texts students are reading in the classroom, which already come with attached contexts to launch from. Thinking about how to choose among words that appear in texts and curricular materials can be spurred by inspecting lists such as the AWL and the Academic Vocabulary List. Other resources for lists of words include Stahl and Nagy (2006) and Beck, McKeown, and Kucan (2008) , which present sets of lists for particular texts and websites that offer word lists for particular content areas, texts, and grade levels (see, e.g., https://www.vocabulary.com and https://www.spellingcity.com ). However, all of these lists should be used along with one's own prudent judgment, which should include considerations of the word's general utility and, specifically, if it seems useful to one's particular students—can you imagine your students finding a way to use the words?

A special case of selecting words can occur when students are reading at levels below their thinking or language comprehension levels. This can occur with both younger and struggling readers. Materials for these students may not offer abundant useful words to teach as far as vocabulary development. A strategy we have used is to select “words about” the text. For example, a simple story may tell the tale of a boy and his dog. You could introduce the word companion . Or a story might portray a child's excitement about an upcoming birthday. You could introduce anticipate or eager. The best overall strategy for selecting words is to tune your attention to be on the lookout for good words in texts or in experiences that students will interact with. Go for words that are important to a text and frequent enough in the language that learning them is worthwhile.

As far as appropriateness for students of different ages and reading levels, when focusing on increasing students' knowledge of word meanings, Tier 2 words are appropriate for every level. For example, here are some words we have taught—and students have learned and used—in kindergarten: extraordinary, commotion, inseparable, cautious, reluctant, delicate, stingy, and remarkable. Note that these words, although considered Tier 2, are not highly polysemous and not as abstract as many on the AWL. The point is to prepare students for language they will be meeting as they go up the grade levels and encounter increasingly academic language. Even if students are not mastering all words that are introduced, the initial experiences are valuable for this preparation.

Why Include Morphology?

One aspect of vocabulary instruction universally understood in the field is that not only would it be an impossible task to teach every word but it would also be impossible to teach even a majority of agreed-upon, important-to-know words. One way to leverage instruction is to attend to general patterns of language, with morphology being the most prominent among those.

What Are Morphemes?

Morphology is the study of morphemes, the smallest units of language that have identifiable meaning or function. Types of morphemes include prefixes, suffixes, and roots. So, for example, unthinkable has three morphemes: un, think, and able . Think is the freestanding root; that is, it can stand on its own as a word. However, our language also contains bound roots, which are word parts that have meaning across words but cannot stand by themselves, such as nov in novel and renovate or voc in vocabulary and advocate . These bound roots are mostly from our Latin heritage, although there are some Greek roots as well.

There are several ways to categorize morphemes:

- Bound or free: Free are basically single-morpheme words, whereas bound morphemes are either affixes or Latin roots.

- Inflectional or derivational: Inflectional morphemes are suffixes added to a word to change number or tense, for example, the – s in dogs or – ing in many verbs. Derivational morphemes are prefixes or suffixes that change the meaning of a word, such as prefixes un – and re– or suffixes –tion and – able .

- Content or function: Content morphemes are morphemes that carry semantic meaning. These include words that are nouns, adjectives, adverbs, and verbs, as well as derivational morphemes and bound (Latin or Greek) roots. Function (also called grammatical ) morphemes are words or suffixes that serve a functional role, such as prepositions, pronouns, or inflectional morphemes.

What Does Research Say About Including Morphology in Vocabulary Study?

A strong and growing body of research shows that knowledge of morphology contributes to reading comprehension ( Anglin, 1993 ; Carlisle, 1995 , 2000 ; Nagy, Berninger, Abbott, Vaughan, & Vermeulen, 2003 ). However, evidence that instruction in morphology leads to enhanced comprehension is less clear. Results of morphological instruction show that students often learned the meanings for the word parts they were taught but rarely generalized that to the learning of new words ( Bowers, Kirby, & Deacon, 2010 ; Curtis, 2006 ). However, recent meta-analyses by Goodwin and Ahn (2013) and Bowers et al. (2010) provided evidence of enhanced spelling and vocabulary learning across 21 morphological interventions and some, albeit small, transfer to new words and to reading comprehension. Virtually, all research on morphology has focused on derivational morphology (prefixes and suffixes). In some instances, Latin roots were occasionally included in instruction, but their effects were not analyzed separately.

Understanding of Latin roots can provide students with some generative knowledge of language that they can use to unlock meanings of unfamiliar words and a way to give students some understanding of how English got to be the way it is. Providing information about English and its Latin layer can “take the lid off language” to help students see its inner workings. Teaching students about the patterns that words follow makes students aware of the connections within language, such as that duplicate and duplicity have double at the core of their meaning. Understanding patterns of language would seem to help students deal with language and its oddities and feel more in control of their language.

My colleagues and I first added a component of Latin root instruction when we developed our middle school RAVE program ( McKeown et al., 2012 ). We called that component Becoming Aware of Language and introduced it by presenting two key concepts about language: that languages are constantly changing and that all languages adopt words from other languages—with English adding a lot of vocabulary from Latin. The RAVE program then introduced several Latin roots in each weekly cycle of instruction. We selected roots that came from the target words and then introduced several more words with the same root. For example, manipulate was one of the target words, and in the Becoming Aware of Language lesson, we introduced the root man, meaning hand, and root-related words manicure, manager, and emancipate (a good resource for identifying roots of words is an online etymological dictionary found at etymonline.com ).

A potential downside of teaching Latin roots is that roots lack consistency phonologically and orthographically. For example, the root sed, meaning to sit, can also be spelled sid —as in preside . Additionally, the meaning of a Latin root within a word is not always transparent. Consider a set of words that contain the root voc, meaning speak or call. That semantic component is easy to understand in the words vocabulary, vocal, vociferous, and even advocate, meaning to speak for someone. However, that same root also occurs in vocation, which has a more metaphorical relation to the root: A vocation is a calling to some endeavor or profession.

Because roots may demonstrate lack of consistent form or lack of transparent meaning, one principle built into our instruction was flexibility: teaching students to be alert to variations and ready to adapt their thinking about the meaning of a new word they meet. We provided practice in this concept by having activities that asked students to problem-solve by working out meanings of words given contexts that contained an unfamiliar root-related word. For example, we presented a picture of a group of people painting a room, with the caption “These friends are renovating an old house.” Students had already learned that nov meant new and then used the visual and semantic context to figure out that the friends were working to make the house new again.

Despite potential downsides of teaching Latin roots, our view is that knowing about roots, and having some knowledge of specific roots and the words in which they appear, is a resource that students can draw on when encountering a new word in context. This knowledge provides a little extra boost to using context alone to puzzle out new word meaning. Even though learners learn most of the words they know from context, it is notoriously unreliable, as writers write to express ideas, not to teach words. Context may hold strong clues to a word's meaning, or little or no clue, and may even misdirect readers as to word meaning (see, e.g., Beck, McKeown, & McCaslin, 1983 ).

In our RAVE work, we did find evidence that students could use their knowledge of roots to unlock the meaning of unfamiliar words ( Crosson & McKeown, 2016 ). For this study, RAVE and control students were given a task that asked them to provide the meaning of root-related words in context. For example, RAVE taught the word diminish and the root min, and in the study task, we presented the sentence “Most of their conversations were about the minutiae of daily life” and asked “What is this saying about their conversations?” We found that RAVE students were significantly more able to provide an accurate interpretation of the word and context, saying, for example, that the conversations were about small details of life.

In a subsequent project, a vocabulary program designed specifically for English learners focused even more strongly on Latin roots. That program is discussed in another article in this forum ( Crosson, McKeown, Robbins, & Brown, 2019 ).

Full instruction in lexical morphology is likely not appropriate for students younger than upper elementary. However, teachers or clinicians can certainly take advantage of opportunities when working with young students. For example, if the words vocabulary and vocal have been encountered, you might mention that they both have voc in them, which means speak, and ask how that relates to each word. No need to go into language history or Latin, but just plant the seed about language having meaningful parts.

Keys to Effective Instruction

Effective instruction means bringing students' attention to words in ways that promote not just knowing word meanings but also understanding how words work and how to utilize word knowledge effectively in higher level tasks, such as reading comprehension. Research on vocabulary development, vocabulary instruction, and its relationship to comprehension has a long and rich history (see Baumann, 2009 ). Over several decades of investigation, a strong consensus has formed about features of effective vocabulary instruction, which can be summarized as follows: present both definitional and contextual information, provide encounters with words in multiple contexts, and engage students' active processing of word meanings. This research has included reviews of multiple studies and individual intervention studies that compare more traditional instruction to instruction that included broad information about words and activities to engage students with using words. Table 1 presents some of the key research milestones that were instrumental in leading to that consensus. More recent intervention research has confirmed that consensus in studies that focus on students as young as kindergarten ( Coyne, McCoach, Loftus, Zipoli, & Kapp, 2009 ; Coyne et al., 2010 ; McKeown & Beck, 2014 ; Silverman, 2007 ) and even preschool ( Wasik & Bond, 2001 ) and on English learners ( Carlo et al., 2004 ; Kieffer & Lesaux, 2012 ). Additionally, a recent meta-analysis confirmed that explicit instruction and depth of processing yield the strongest effects for children at risk ( Marulis & Neuman, 2013 ).

Research milestones in establishing consensus on vocabulary instruction.

To reiterate, these principles of effective instruction have been found to apply for teaching word meanings for all students—students of all levels, pre-K through high school; learners learning English as an additional language; and learners with learning disabilities. Note, however, that teaching word meanings differs from teaching students to read. Reading requires a different kind of instruction and practice. Although it is a good practice to at least familiarize students with the orthographic representations of words being taught for meaning, the emphasis and goals are different.

The need for instruction that focuses on definitional and contextual information, encounters in multiple contexts, and active processing stems from the nature of word meaning itself. Because word meaning is, as discussed earlier, multifaceted, polysemous, and flexible, it should be clear, first, that a definition of a word will not suffice for effective learning. A definition can only capture limited information, and although definitions can be a good starting point, or good shorthand for remembering a word's meaning, knowing definitions will not support comprehension ( McKeown, Beck, Omanson, & Pople, 1985 ; Stahl & Fairbanks, 1986 ).

The multifaceted, polysemous nature of word knowledge also means that vocabulary learning is incremental. It is virtually impossible to learn everything you need to know about a word from just one encounter. Experiencing words in multiple contexts leads learners to build rich networks of connections to a word and across similar words. A word's meaning becomes generalized across encounters, losing its connection to specific contexts, which allows it to be applied flexibly to new contexts. Flexible knowledge enables learners to bring the most relevant aspects of a word's meaning to bear in making sense of subsequent contexts in which the word is met ( Reichle & Perfetti, 2003 ).

However, simply encountering words in multiple contexts does not maximize learning. A learner needs to engage in active processing of the information in those encounters in order to reap top benefits. Active processing means interacting with words—manipulating ideas around words in order to extend and deepen knowledge of the word, its uses, and its connections to other words and situations. This is requisite for building the kind of rich and flexible knowledge that will support students in comprehending and using language.

The focus of this section is what effective interactions that engage students' active processing look like. The core of such interactions is really pretty simple—prompt students to do something with the words that encompasses thinking about features of a word's meaning and how the word can be used. The activities presented are generally examples of activities that teachers have used with whole classrooms, but they could easily be used or slightly adapted to be used in a clinical setting, such as by a speech-language pathologist and an individual student. The activities are appropriate for all levels as well. The same activity formats can be used with kindergartners or high schoolers; the words themselves and the responses of the students drive the maturity level of the discussions. The examples used here are from first grade, second grade, and middle school.

The following examples illustrate interactions that are intended to prompt student thinking about different aspects and features of word meaning. Experiencing this variety helps students build a flexible, reflective approach to words and their uses. This first activity helps students think about how different words can relate to the same contexts and to choose the word they would apply. The teacher would then follow up by asking the student to explain how their choice fits:

- Try out a flying machine

- Taste a new food made of seaweed

- Taste a new kind of chocolate

- Enter a singing contest

Interactions that ask students to make choices can prompt them to reflect on a word's features, for example, the extent of change that refine entails.

- Making some small changes to your science project or starting all over with a new one?

- Getting your hair trimmed or having your head shaved?

It is important to include interactions that prompt students to think about different senses of a word, such as the different senses of expose in the following:

- How could middle school students be exposed to what it will be like in high school?

- How could you expose someone who was mistreating his dog?

Interactions can and should be quick and fun! We have seen teachers turn up the fun quotient in various ways. One example is the way they ask students to indicate their response. A teacher we worked with told her first-grade students, “If you think I'm talking about something that is mighty, show me your muscles,” and then provided examples such as “a strong woman lifting up a tiger” and “a big river that floods nearby homes.”

Interactions should include providing feedback to students, for example, asking “why” when a student responds to the eager/reluctant prompts. Feedback helps to build and reinforce connections to a word in the student's mental lexicon.

Asking students to provide their own examples of a word is an interaction strategy that is easily implemented and potentially effective. For example, simply ask “What is something in your life that you would like to refine?” or “What is something you are always eager to do?” Asking students to create their own examples, however, should not be one of the first activities students are asked to do with a newly introduced word. Students often have difficulty coming up with their own ideas initially and often repeat the context in which a word has been introduced. So calling on students' creative use of words is best employed after students have been exposed to a number of uses and had time to reflect on how it might apply to them.

Feedback is especially important for interactions that prompt student-created examples, to monitor understanding and keep responses on the right track or redirect if necessary. A good way to build an effective habit of feedback is to think about the rule of thumb of improv comedy—“Yes, and…,” which involves acknowledging what someone has said and then expanding on it. In an improv troupe, this keeps the comedy rolling; in vocabulary instruction, it keeps the connections building. Note the “yes, and”-ing in the following exchange:

Teacher: What is something you'd want if you were famished? Student: Pizza. Teacher: Mm, pizza! And what would you do with that pizza if you were famished? Student: Gobble it all right up! Teacher: Oh, boy, yeah, because if you're famished, do you want just one piece of pizza?

Note in this next example that the teacher's “and” allows her to prompt students to generalize about entailments of the target word delicate .

Teacher: What are some things that are delicate ? … Student 1: A glass vase. Student 2: A brand new baby. Teacher: What is it about delicate things, like vases and babies? How do we have to act around them? Student 3: Be really, really careful….

Although the above examples of “yes, and” are from a classroom discussion, that technique is strongly applicable to clinical interactions between one child and a clinician. A clinician is in a good position to tailor feedback to a student's individual needs and interests.

Because vocabulary learning requires multiple exposures and because time with students is a precious resource, we need to seek ways to leverage attention to words, or figure out how to get more bang for the buck! Having a clinician coordinate with a student's classroom teacher could offer an ideal opportunity to leverage attention to vocabulary. A clinician can ask the classroom teacher for words that the class is focusing on or words that a particular student needs help with. The clinician is in a good position, then, to apply playful techniques, such as the activities exemplified above; to provide practice in vocabulary; and to build enjoyment with language. The clinician is also in a good position to provide extension and enrichment, for example, by introducing other words that associate with the classroom vocabulary. Because the activities suggested set a conversational, spontaneous tone, they might allow the clinician to identify gaps in a student's vocabulary repertoire and both directly help with those and inform the teacher about words that seem unfamiliar to a student or difficult for a student to use.

Another way for clinicians to enhance vocabulary attention is through their own word use. This can start with awareness of their own language use, deliberately using sophisticated words—both those that are being taught and others that are appropriate to situations—in interactions with students. Challenge students to “catch” you using target words and then turn it around—challenge students to use target words during lessons and provide some sort of points or simple rewards when they do.

Another important leverage point in vocabulary instruction is prompting students to use and be aware of words outside formal instruction. Such prompting can start with informal coordination among school professionals—classroom teacher, clinician, and beyond. This might begin with posting a list of target words on the classroom door and privately encouraging other adults to use the words when they visit or when students work with them. A next level of increased attention could include a vocabulary bulletin board, posting interesting uses of target words, both those found in written materials and those that students have generated.

Going beyond instructional sites for vocabulary should also include going beyond school, motivating students to take their vocabulary awareness home with them. Clinicians can easily take a lead role in this and then prompt the classroom teacher to join in. Challenge students to find target words in books they are reading, in menus, music, and video games, and to use the words with their families. My colleagues and I have promoted these kinds of activities in two studies and found that students respond with enthusiasm! However, best of all, we found that it affects the outcomes. In a fourth-grade study, when students were offered the opportunity to find words outside class through an activity we called Word Wizard , we found increased comprehension effects over instruction that did not include the Wizard component ( McKeown et al., 1985 ).

In a study with sixth graders, we invited them to engage through In the Media , an activity that challenged them to find their words in any media outside school. We received great response, including students finding words in sports broadcasts— dynamic players—and in Sunday school verses! In that study, we found that students who engaged with In the Media had greater learning gains on a vocabulary posttest ( McKeown, Crosson, Artz, Sandora, & Beck, 2013 ). Although our direct experiences have involved fourth grade and middle school students, we have worked with teachers who have had success with such activities with students from kindergarten through high school.

If students do not respond at first to the idea of finding words, that activity can be seeded with some specific directions to spur students on. For example, ask them to notice in something they read, hear, or see, such as

- someone who does something voluntary

- someone who needs to adapt to a new situation

- someone who had to consult with another person.

Or you might ask them to choose one of their vocabulary words to describe

- a character in a book they are reading

- someone on the news or in the newspaper

- someone in a commercial

- an actor in a video or movie.

As a final point, it is necessary to include a caveat to clinicians: You may be disappointed to find that teachers you work with devote little, if any, time to vocabulary. Even if they do, the words they work with may not be the best choices for generative vocabulary building, but words with specific and narrow use in curricular materials. If that situation is in play, you are on your own—so I implore you to take up the mantle of vocabulary progenitor! This can flow from a cultivated interest and attention to words and word use. Choose words that appear in student materials or that emerge from current school or community events, for example. Use newspapers, websites, word lists such as the AWL ( Coxhead, 2000 ), or words you bump into in your own reading to create a set of words to use with students. Included in the Appendix are the words we taught in RAVE, all of which are taken from the AWL.

Wrapping Up

Always keep in mind that language is a strange, fascinating, vibrant human creation. Exploring its puzzlements and figuring out its patterns should be endlessly intriguing. Sparking that kind of attitude in students takes them a long way toward being successful, confident language users. Clinicians and teachers can propel students along that way by choosing useful, interesting words, helping students get an initial understanding of them through multiple exposures and lively interactions, and clinicians and teachers, as well as other school personnel in contact with students, can encourage students to notice and revel in words in their environment. The essence of all these activities that keep attention focused on vocabulary is to generate excitement around words and students' uses of them.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the Institute for Education Sciences of the U.S. Department of Education for its support to some of the research described in this clinical focus article: Robust Instruction of Academic Vocabulary for Middle School Students, Award R305A100440 granted to Margaret G. McKeown and Isabel L. Beck from the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. The opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the institute, and no official endorsement should be inferred.

Words Taught in Robust Academic Vocabulary Encounters Program

Funding statement.

The author gratefully acknowledges the Institute for Education Sciences of the U.S. Department of Education for its support to some of the research described in this clinical focus article: Robust Instruction of Academic Vocabulary for Middle School Students, Award R305A100440 granted to Margaret G. McKeown and Isabel L. Beck from the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

- Anglin, J. M. (1993). Vocabulary development: A morphological analysis . Monographs of the Society of Research in Child Development , 58 , i–186. [ Google Scholar ]

- Baugh, A. C. , & Cable, T. (1978). A history of the English language (6th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Baumann, J. F. (2009). Vocabulary and comprehension: The nexus of meaning . In Israel S. E. & Duffy G. G. (Eds.), Handbook of research on reading comprehension (pp. 323–346). New York, NY: Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck, I. L. , & McKeown, M. G. (1985). Teaching vocabulary: Making the instruction fit the goal . Educational Perspectives , 23 ( 1 ), 11–15. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck, I. L. , McKeown, M. G. , & Kucan, L. (2002). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction . New York, NY: Guilford. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck, I. L. , McKeown, M. G. , & Kucan, L. (2008). Creating robust vocabulary: Frequently asked questions and extended examples . New York, NY: Guilford. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck, I. L. , McKeown, M. G. , & Kucan, L. (2013). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck, I. L. , McKeown, M. G. , & McCaslin, E. S. (1983). Vocabulary development: All contexts are not created equal . The Elementary School Journal , 83 , 177–181. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bos, C. S. , & Anders, P. L. (1990). Effects of interactive vocabulary instruction on the vocabulary learning and reading comprehension of junior-high learning disabled students . Learning Disability Quarterly , 13 ( 1 ), 31–42. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bos, C. S. , & Anders, P. L. (1992). Using interactive teaching and learning strategies to promote text comprehension and content learning for students with learning disabilities . International Journal of Disability, Development and Education , 39 ( 3 ), 225–238. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bowers, P. N. , Kirby, J. R. , & Deacon, S. H. (2010). The effects of morphological instruction on literacy skills: A systematic review of the literature . Review of Educational Research , 80 ( 2 ), 144–179. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carey, S. (1978). The child as word learner . In Halle M., Bresnan J., & Miller G. (Eds.), Linguistic theory and psychological reality (pp. 264–293). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carlisle, J. F. (1995). Morphological awareness and early reading achievement . In Feldman L. (Ed.), Morphological aspects of language processing (pp. 189–209). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carlisle, J. F. (2000). Awareness of the structure and meaning of morphologically complex words: Impact on reading . Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal , 12 , 169–190. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carlo, M. S. , August, D. , McLaughlin, B. , Snow, C. E. , Dressler, C. , Lippman, D. N. , … White, C. E. (2004). Closing the gap: Addressing the vocabulary needs of English language learners in bilingual and mainstream classrooms . Reading Research Quarterly , 39 , 188–215. [ Google Scholar ]

- Casey, N. , & Escobar, R. (2018, September 19). Colombia struck a peace deal with guerrillas, but many return to arms . New York Times . Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com

- Corson, D. J. (1985). The lexical bar . Oxford, United Kingdom: Pergamon Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Corson, D. J. (1995). Using English words . Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic. [ Google Scholar ]

- Coxhead, A. (2000). A new academic word list . TESOL Quarterly , 34 ( 2 ), 213–238. [ Google Scholar ]

- Coyne, D. M. , McCoach, D. B. , Loftus, S. , Zipoli, R., Jr. , & Kapp, S. (2009). Direct vocabulary instruction in kindergarten: Teaching for breadth versus depth . The Elementary School Journal , 110 ( 1 ), 1–18. [ Google Scholar ]

- Coyne, M. D. , McCoach, D. B. , Loftus, S. , Zipoli, R. , Ruby, M. , Crevecoeur, Y. , … Kapp, S. (2010). Direct and extended vocabulary instruction in kindergarten: Investigating transfer effects . Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness , 3 ( 2 ), 93–120. [ Google Scholar ]

- Crosson, A. C. , & McKeown, M. G. (2016). Middle school learners' use of Latin roots to infer the meaning of unfamiliar words . Cognition and Instruction , 34 ( 2 ), 1–24. [ Google Scholar ]

- Crosson, A. C. , McKeown, M. G. , Robbins, K. P. , & Brown, K. J. (2019). Key elements of robust vocabulary instruction for emergent bilingual adolescents . Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools , 50 , 493–505. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_LSHSS-VOIA-18-0127 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Curtis, M. E. (2006). The role of vocabulary instruction in adult basic education . In Comings J., Garner B., & Smith C. (Eds.), Review of adult learning and literacy (Vol. 6 , pp. 43–69). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dole, J. A. , Sloan, C. , & Trathen, W. (1995). Teaching vocabulary within the context of literature . Journal of Reading , 38 ( 6 ), 452–460. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gardner, D. , & Davies, M. (2013). A new academic vocabulary list . Applied Linguistics , 35 ( 3 ), 305–327. [ Google Scholar ]

- Goodwin, A. P. , & Ahn, S. (2013). A meta-analysis of morphological interventions in English: Effects on literacy outcomes for school-age children . Scientific Studies of Reading , 17 ( 4 ), 257–285. [ Google Scholar ]

- Graves, M. F. , & Prenn, M. C. (1986). Costs and benefits of various methods of teaching vocabulary . Journal of Reading , 29 ( 7 ), 596–602. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hayes, D. P. , & Ahrens, M. (1988). Vocabulary simplification for children: A special case of “motherese.” Journal of Child Language , 15 , 395–410. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kieffer, M. J. , & Lesaux, N. K. (2012). Effects of academic language on relational and syntactic aspects of morphological awareness for sixth graders from linguistically diverse backgrounds . Elementary School Journal , 112 ( 3 ), 519–545. [ Google Scholar ]

- Margosein, C. M. , Pascarella, E. T. , & Pflaum, S. W. (1982). The effects of instruction using semantic mapping on vocabulary and comprehension . Paper presented at the meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New York, NY. [ Google Scholar ]

- Marulis, L. M. , & Neuman, S. B. (2013). How vocabulary interventions affect young children at risk: A meta-analytic review . Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness , 6 , 223–262. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mezynski, K. (1983). Issues concerning the acquisition of knowledge: Effects of vocabulary training on reading comprehension . Review of Educational Research , 53 ( 2 ), 253–279. [ Google Scholar ]

- McKeown, M. G. , & Beck, I. L. (2014). Effects of vocabulary instruction on measures of language processing: Comparing two approaches . Early Childhood Research Quarterly , 29 ( 4 ), 520–530. [ Google Scholar ]

- McKeown, M. G. , Beck, I. L. , Omanson, R. C. , & Pople, M. T. (1985). Some effects of the nature and frequency of vocabulary instruction on the knowledge and use of words . Reading Research Quarterly , 20 , 522–535. [ Google Scholar ]

- McKeown, M. G. , Crosson, A. C. , Artz, N. J. , Sandora, C. , & Beck, I. L. (2013). In the media: Expanding students' experience with academic vocabulary . The Reading Teacher , 67 ( 1 ), 45–53. [ Google Scholar ]

- McKeown, M. G. , Crosson, A. C. , Beck, I. , Sandora, C. , & Artz, N. (2012). Robust Academic Vocabulary Encounters (RAVE) . Intervention developed for Robust Instruction of Academic Vocabulary for Middle School Students . Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, Award R305A100440.

- McKeown, M. G. , Deane, P. D. , Scott, J. A. , Krovetz, R. , & Lawless, R. R. (2017). Vocabulary assessment to support instruction: Building rich word-learning experiences . New York, NY: Guilford. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nagy, W. E. , Berninger, V. , Abbott, R. , Vaughan, K. , & Vermeulen, K. (2003). Relationship of morphology and other language skills to literacy skills in at-risk second grade readers and at-risk fourth grade writers . Journal of Educational Psychology , 95 ( 4 ), 730–742. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nagy, W. E. , & Scott, J. A. (2000). Vocabulary processes . In Kamil M. L., Mosenthal P. B., David Pearson P., & Barr R. (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. 3 , pp. 69–284). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Google Scholar ]

- National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (NIH Pub. No. 00-4754) . Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health. [ Google Scholar ]

- Perfetti, C. A. (2007). Reading ability: Lexical quality to comprehension . Scientific Studies of Reading , 11 ( 4 ), 357–383. [ Google Scholar ]

- Reichle, E. D. , & Perfetti, C. A. (2003). Morphology in word identification: A word-experience model that accounts for morpheme frequency effects . Scientific Studies of Reading , 7 ( 1 ), 219–238. [ Google Scholar ]

- Silverman, R. (2007). A comparison of three methods of vocabulary instruction during read-alouds in kindergarten . Elementary School Journal , 108 ( 2 ), 97–113. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stahl, S. A. , & Fairbanks, M. M. (1986). The effects of vocabulary instruction: A model-based meta-analysis . Review of Educational Research , 56 , 72–110. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stahl, S. A. , & Nagy, W. E. (2006). Teaching word meanings . Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wasik, B. A. , & Bond, M. A. (2001). Beyond the pages of a book: Interactive book reading and language development in preschool classrooms . Journal of Educational Psychology , 93 , 243–250. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shopping Cart 0

- Read Naturally Live

- Word Warm-ups Live

- One Minute Reader Live

- Read Naturally Live—Español

- Order Read Live

- Log In to Read Live

- Read Live Help

- Read Naturally Encore II

- Read Naturally GATE+

- Word Warm-ups

- Take Aim at Vocabulary

- Signs for Sounds

- All Intervention Programs

- Assessment Tools

- Accessories

- Read Live Hands-on Public Seminar

- Read Live Hands-on District Seminar

- Read Naturally Live Virtual Seminar

- Read Live Online Courses

- Student Training Videos

- Encore II Virtual Seminar

- Conferences

- Read Naturally Strategy

- Components of Reading

- Research Basis for Programs

- Challenges We Address

- Evidence-Based Studies

- Additional Studies and Reviews

- Alignment With Best Practices

- Technical Info (Assessments)

Connect With Us

- Submit a Review

- News and Awards

- Contact Info

- Star of the Month

- School of the Year

- Friends and Partners

- Knowledgebase

The Importance of Vocabulary Development

According to Steven Stahl (2005), “Vocabulary knowledge is knowledge; the knowledge of a word not only implies a definition, but also implies how that word fits into the world.” We continue to develop vocabulary throughout our lives. Words are powerful. Words open up possibilities, and of course, that’s what we want for all of our students.

Key Concepts

Differences in early vocabulary development.

We know that young children acquire vocabulary indirectly, first by listening when others speak or read to them, and then by using words to talk to others. As children begin to read and write, they acquire more words through understanding what they are reading and then incorporate those words into their speaking and writing.

Vocabulary knowledge varies greatly among learners. The word knowledge gap between groups of children begins before they enter school. Why do some students have a richer, fuller vocabulary than some of their classmates?

- Language rich home with lots of verbal stimulation

- Wide background experiences

- Read to at home and at school

- Read a lot independently

- Early development of word consciousness

Why do some students have a limited, inadequate vocabulary compared to most of their classmates?

- Speaking/vocabulary not encouraged at home

- Limited experiences outside of home

- Limited exposure to books

- Reluctant reader

- Second language—English language learners

Children who have been encouraged by their parents to ask questions and to learn about things and ideas come to school with oral vocabularies many times larger than children from disadvantaged homes. Without intervention this gap grows ever larger as students proceed through school (Hart and Risley, 1995).

How Vocabulary Affects Reading Development

From the research, we know that vocabulary supports reading development and increases comprehension. Students with low vocabulary scores tend to have low comprehension and students with satisfactory or high vocabulary scores tend to have satisfactory or high comprehension scores.

The report of the National Reading Panel states that the complex process of comprehension is critical to the development of children’s reading skills and cannot be understood without a clear understanding of the role that vocabulary development and instruction play in understanding what is read (NRP, 2000).

Chall’s classic 1990 study showed that students with low vocabulary development were able to maintain their overall reading test scores at expected levels through grade four, but their mean scores for word recognition and word meaning began to slip as words became more abstract, technical, and literary. Declines in word recognition and word meaning continued, and by grade seven, word meaning scores had fallen to almost three years below grade level, and mean reading comprehension was almost a year below. Jeanne Chall coined the term “the fourth-grade slump” to describe this pattern in developing readers (Chall, Jacobs, and Baldwin, 1990).

Incidental and Intentional Vocabulary Learning

How do we close the gap for students who have limited or inadequate vocabularies? The National Reading Panel (2000) concluded that there is no single research-based method for developing vocabulary and closing the gap. From its analysis, the panel recommended using a variety of indirect (incidental) and direct (intentional) methods of vocabulary instruction.

Incidental Vocabulary Learning Most students acquire vocabulary incidentally through indirect exposure to words at home and at school—by listening and talking, by listening to books read aloud to them, and by reading widely on their own.

The amount of reading is important to long-term vocabulary development (Cunningham and Stanovich, 1998). Extensive reading provides students with repeated or multiple exposures to words and is also one of the means by which students see vocabulary in rich contexts (Kamil and Hiebert, 2005).

Intentional Vocabulary Learning Students need to be explicitly taught methods for intentional vocabulary learning. According to Michael Graves (2000), effective intentional vocabulary instruction includes:

- Teaching specific words (rich, robust instruction) to support understanding of texts containing those words.

- Teaching word-learning strategies that students can use independently.

- Promoting the development of word consciousness and using word play activities to motivate and engage students in learning new words.

Research-Supported Vocabulary-Learning Strategies

Students need a wide range of independent word-learning strategies. Vocabulary instruction should aim to engage students in actively thinking about word meanings, the relationships among words, and how we can use words in different situations. This type of rich, deep instruction is most likely to influence comprehension (Graves, 2006; McKeown and Beck, 2004).

Student-Friendly Definitions

The meaning of a new word should be explained to students rather than just providing a dictionary definition for the word—which may be difficult for students to understand. According to Isabel Beck, two basic principles should be followed in developing student-friendly explanations or definitions (Beck et al., 2013):

- Characterize the word and how it is typically used.

- Explain the meaning using everyday language—language that is accessible and meaningful to the student.

Sometimes a word’s natural context (in text or literature) is not informative or helpful for deriving word meanings (Beck et al., 2013). It is useful to intentionally create and develop instructional contexts that provide strong clues to a word’s meaning. These are usually created by teachers, but they can sometimes be found in commercial reading programs.

Defining Words Within Context