- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Women, Art, and Art History: Gender and Feminist Analyses

Introduction, foundational texts: gender, history, and paradigm shift.

- Sources for Women Artists from Classical Antiquity to 17th-Century Europe

- 19th-Century Western Art History: The Survey

- Women as Art Historians, Archaeologists, and Curators

- Women and Art History before 1971

- 20th-Century Dictionaries of Women Artists

- Bibliographies of Women in the Arts

- Reviews of the Emergence of Feminist Studies in Art History in the United States and the United Kingdom

- Western 1970s–1980s

- Western 1990s–2000s: Histories of Feminist Art

- International

- Interviews and Anthologies of Writings

- Italian Renaissance and Baroque

- 18th Century

- Modern Period

- Feminist Art, Theory, and Practice

- Theoretical Approaches

- Museums of Women’s Art

- Reviewing Major Collections

- Curatorial Practices

- Initiating Exhibitions: Women Artists of the Western Tradition

- Feminist Exhibitions

- Specialist Exhibitions

- Increasing the International Perspectives

- Feminism and Visual Culture

- The Hierarchy of the Arts

- Professions

- Feminism and Social History of Art

- Feminism and Semiotics

- Feminist Art History and Aby Warburg

- Feminism and Psychoanalysis

- Selected Perspectives on Period Studies

- The Magnificent Exception: Artemisia Gentileschi

- Self-Portraiture

- Orientalism

- Feminist Analyses of Masculinity and Art

- Race, Ethnicity, Black Subjectivity, and Representation

- Lesbian Subjectivity and Visual Culture

- Jewish Subjectivity, Art, and History

- The Victorians

- Modernity, Landscape, Urban Space, and the Flâneuse

- Thinking about the Modern

- The Avant-Garde

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Art and Psychoanalysis

- Art Theory in Europe to 1800

- Contemporary Art

- Eighteenth-Century Europe

- Gender and Art in the Middle Ages

- Gender and Art in the Renaissance

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Art of the Catholic Religious Orders in Medieval Europe

- Color in European Art and Architecture

- Japanese Buddhist Paintings

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Women, Art, and Art History: Gender and Feminist Analyses by Griselda Pollock LAST REVIEWED: 30 January 2014 LAST MODIFIED: 30 January 2014 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199920105-0034

Following a worldwide feminist movement in the later 20th century, women became a renewed topic for art and art history, giving rise to gender analysis of both artistic production and art historical discourse. Gender is to be understood as a system of power, named initially patriarchal and also theorized as a phallocentric symbolic order. A renewed and theoretically developed as well as activist feminist consciousness initially mandated the historical recovery of the contribution of women as artists to art’s international histories to counter the effective erasure of the history of women as artists by the modern discipline of art history. This has also led to a rediscovery of the contributions of women as art historians to the discipline itself. Gender analysis raises the repressed question of gender (and sexuality) in relation both to creativity itself and to the writing of art’s necessarily pluralized histories. Gender refers to the asymmetrical hierarchy between those distinguished both sociologically and symbolically on the basis of perceived, but not determining, differences. Although projected as natural difference between given sexes, the active and productive processes of social and ideological differentiation produces as its effects gendered difference that is claimed, ideologically, as “natural.” As an axis of power relations, gender can be shown to shape social existence of men and women and determine artistic representations. Gender is thus also understood as a symbolic dimension shaping hierarchical oppositions in representation in texts, images, buildings, and discourses about art. It is constantly being produced by the work performed by art and writing about art. Feminist analysis critiques these technologies of gender while itself also being one, albeit critically seeking transformation of social and symbolic gender. The analysis of gender ideologies in the writing of art history and in art itself, therefore, extend to art produced by all artists, irrespective of the gendered identity of the artist. Women, having been excluded by the gendering discourses of modern art history, have had to be recovered from an oblivion those discourses created while the idea of women as artist has to be reestablished in the face of a an ideology that places anything feminine in a secondary position. Women are not, however, a homogeneous category defined by gender alone. Women are agonistically differentiated by class, ethnicity, culture, religion, geopolitical location, sexuality, and ability. Gender analysis includes the interplay of several axes of differentiation and their symbolic representations without any a priori assumptions about how each artwork/artist might negotiate and rework dominant discourses of gender and other social inflections. The postcolonial critique of Western hegemony and a search for non-Western-centered models of inclusiveness that respect diversity without creating normative relativism are driving the tendency of the research into gender in and art history toward an as yet unrealized inclusiveness regarding gender and difference in general rather than the creation of separate subcategories on the basis of the gender or other qualifying characteristics of the artist. The objectives of critical art historical practices focusing on gender and related axes of power are to ensure consistent and rigorous research into all artists, irrespective of gender, for which a specific initiative focusing on women as artists in order to correct a skewed and gender-selective archive has been necessary, and to expand the paradigm of art historical research in general to ensure that the social, economic, and symbolic functions of gender, sexual, and other social and psycho-symbolic differences are consistently considered as part of the normal procedures of art historical analysis.

Without a foundational understanding of the social meaning and symbolic operation of gender, both the historical process of artistic creation and the historical representation of that history will not be grasped. Women working on art history (domain and discipline) draw on germane theoretical interventions in historical research while also using sociological studies of institutions to call for a paradigm shift in art history itself. Scott 1986 offers a key argument for gender analysis in the historical disciplines, examining different theoretical paradigms that have been introduced to approach gender as an axis in history. Kelly-Gadol 1977 is a critical reading of the major cultural shifts from late medieval culture in which Troubadour culture allowed women agency in relation to love by means of appropriating feudal relations to the Renaissance in which new concepts of the decorative courtier closed out such opportunities for women. In art history, Nochlin 1973 is the foundational text of a specifically feminist challenge to art history. Nochlin calls for a radical, paradigm shift in art history (discipline). Raising the “woman question” becomes a lever to challenge the exclusion of all social and institutional factors in the study of art’s histories. The text’s title is, however, representative of its own moment in 1971 when women art historians had to confront a discipline that presented art history (domain) almost entirely without women, having established a canon solely composed of great masters. Honoring Gabhart and Broun 1972 ’s neologism “Old Mistresses” (cited under Initiating Exhibitions: Women Artists of the Western Tradition ) to point out how language already disqualifies women from recognition as “masters.” Parker and Pollock 2013 (written in 1978 and originally published 1981) identifies the discursive habits of the discipline of art history as structurally gendered and gendering. The authors, however, also stress the ways that women artists actively negotiated their own differential situations to produce distinctive interventions in their own cultural context and to show how they negotiated the image of woman and of the artist in different contexts. Broude and Garrard 1982 lays out the case for feminist studies across all periods of art to reveal the central role of gender in historical cultures and visual practices while recognizing the distorting effects of an unacknowledged masculinist and heteronormative bias in art historical interpretation. The authors demonstrate the overall shifts in art historical method that result from awareness of gender in culture. De Lauretis 1987 uses a Foucaultian model to understand gender as an effect produced in its representations, self-representations, and feminist deconstructions, challenging a model that, privileging man/woman difference, makes lesbian subjectivities invisible. Battersby 1989 traces gender across philosophical aesthetics to reveal its foundational and continuing gender thinking. Broude and Garrard 1992 tracks the developing range of theories of gender in relation to art historical analysis registering the impact of postmodernist concepts of authorship and subjectivity while balancing such trends with an equal acknowledgement of the agency of women in contesting historically variable organizations and representations of gender relations.

Battersby, Christine. Gender and Genius: Towards a Feminist Aesthetics . London: Women’s Press, 1989.

An extended, philosophically based analysis of the gendering of the concept of genius from the ancients of the West to Simone de Beauvoir, revealing the identification of genius with the masculine body and conventionalized masculine attributes defined in opposition to the equally constructed and rhetorical figure of the feminine. Such an analysis is necessary in order to create the ground for any reconsideration of the contribution of women to art.

Broude, Norma, and Mary Garrard. “Introduction: Feminism and Art History.” In Feminism and Art History: Questioning the Litany . Edited by Norma Broude and Mary Garrad 1–18. New York: Harper & Row, 1982.

Introducing their first major collection of substantive works of feminist art historical scholarship, Broude and Garrard position feminism’s impact on art history as a major reconceptualization of previous history and art historiography as patriarchal, necessitating radical revisions to the distortions created by sexual bias in the creation and interpretation of art and demanding a new definition of the cultural and social uses of art.

Broude, Norma, and Mary Garrard. “Introduction: The Expanding Discourse.” In The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History . Edited by Norma Broude and Mary Garrad, 1–25. New York: Harper Collins, 1992.

Representing the theoretical and methodological diversity of feminist studies in art history from its second decade, Broude and Garrard both identify the effects of “postmodernist” theories of authorship, the gaze and the social construction of gender in art history, while contesting the tendency to polarize feminist scholarship between modern and postmodern, essentialist and constructivist, traditionalist and theoretical. They advocate incremental change in the discipline and argue for a continuing acknowledgement of the importance of studies of women’s authorship in art.

de Lauretis, Teresa. “The Technology of Gender.” In Technologies of Gender: Essays on Theory, Film, and Fiction . By Teresa de Lauretis, 1–30. London: Macmillan, 1987.

Challenging predominantly masculine narratives of gender that effectively install the heterosexual contract, which may be reproduced in feminist texts, because of the fact that gender is always being produced in the play between representation and self-representation, de Lauretis sketches out methods for countering the exclusion of nonheteronormative subjectivities by suggesting that otherness and difference is always already present in the “spaces off” of dominant discourses.

Kelly-Gadol, Joan. “Did Women Have a Renaissance?” In Becoming Visible: Women in European History . Edited by Renate Bridenthal and Claudia Koonz, 19–50. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1977.

Kelly-Gadol stresses that the temporalities of gender relations may not only not coincide with the progressive model of historical periodization—the Renaissance as progress—but may be in conflict. Histories attentive to gender do not necessarily coincide with those that are gender-blind. Reprinted in Women, History and Theory: The Essays of Joan Kelly (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), pp. 19–50.

Nochlin, Linda. “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” In Art and Sexual Politics: Women’s Liberation, Women Artists, and Art History . Edited by Thomas B. Hess and Elizabeth C. Baker 44. New York: Collier, 1973.

First published in ARTnews (January 1971), pp. 22–39, 67–71. Nochlin discouraged her colleagues from answering her question by seeking candidates for “great woman artist.” She questioned the rhetorical figure of the autonomous genius and insisted upon the role of discriminatory institutions and practices that had limited women’s, and others’, potential and access to training and recognition. Her perspective suggested that reduced discrimination would create a level playing field for women.

Parker, Rozsika, and Griselda Pollock. Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology . 3d ed. London: I. B. Tauris, 2013.

Defining art history as an ideologically impregnated discourse, the authors track stereotypes of femininity (mindless, decorative, derivative, dextrous, weak) negatively invoked to sustain an unacknowledged masculinization of art and the artist. They critique the gendered hierarchy of art versus craft and assess the strategic interventions into the representation of gender difference, body, and identity of artists from the Middle Ages to the late 20th century.

Scott, Joan W. “Gender: A Useful Category for Historical Analysis.” American Historical Review 91.5 (1986): 1053–1075.

DOI: 10.2307/1864376

Scott reviews working definitions of both the social construction of gender and the symbolic function of gender in representing and enacting hierarchical difference. Gender is presented not only as a historically fabricated social relation but also as an effective element in representational systems that also exceed the relations of masculine and feminine. This is a critical text of the potential for gender as a category for historical research. Available online for purchase or by subscription.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Art History »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Activist and Socially Engaged Art

- Adornment, Dress, and African Arts of the Body

- Alessandro Algardi

- Ancient Egyptian Art

- Ancient Pueblo (Anasazi) Art

- Angkor and Environs

- Art and Archaeology of the Bronze Age in China

- Art and Architecture in the Medieval Kingdom of Hungary

- Art and Propaganda

- Art of Medieval Iberia

- Art of the Crusader Period in the Levant

- Art of the Dogon

- Art of the Mamluks

- Art of the Plains Peoples

- Art Restitution

- Artemisia Gentileschi

- Arts of Senegambia

- Arts of the Pacific Islands

- Assyrian Art and Architecture

- Australian Aboriginal Art

- Aztec Empire, Art of the

- Babylonian Art and Architecture

- Bamana Arts and Mande Traditions

- Barbizon Painting

- Bartolomeo Ammannati

- Bernini, Gian Lorenzo

- Bohemia and Moravia, Renaissance and Rudolphine Art of

- Borromini, Francesco

- Brazilian Art and Architecture, Post-independence

- Burkina Art and Performance

- Byzantine Art and Architecture

- Caravaggio, Michelangelo Merisi da

- Carracci, Annibale

- Ceremonial Entries in Early Modern Europe

- Chaco Canyon and Other Early Art in the North American Sou...

- Chicana/o Art

- Chimú Art and Architecture

- Colonial Art of New Granada (Colombia)

- Conceptual Art and Conceptualism

- Courbet, Gustave

- Czech Modern and Contemporary Art

- Daumier, Honoré

- David, Jacques-Louis

- Delacroix, Eugène

- Design, Garden and Landscape

- Destruction in Art

- Destruction in Art Symposium (DIAS)

- Dürer, Albrecht

- Early Christian Art

- Early Medieval Architecture in Western Europe

- Early Modern European Engravings and Etchings, 1400–1700

- Ephemeral Art and Performance in Africa

- Ethiopia, Art History of

- European Art, Historiography of

- European Medieval Art, Otherness in

- Expressionism

- Eyck, Jan van

- Feminism and 19th-century Art History

- Festivals in West Africa

- Francisco de Zurbarán

- French Impressionism

- Gender and Art in the 17th Century

- Giotto di Bondone

- Gothic Architecture

- Gothic Art in Italy

- Goya y Lucientes, Francisco José

- Great Zimbabwe and its Legacy

- Greek Art and Architecture

- Greenberg, Clement

- Géricault, Théodore

- Iconography in the Western World

- Installation Art

- Islamic Art and Architecture in North Africa and the Iberi...

- Japanese Architecture

- Japanese Buddhist Sculpture

- Japanese Ceramics

- Japanese Literati Painting and Calligraphy

- Jewish Art, Ancient

- Jewish Art, Medieval to Early Modern

- Jewish Art, Modern and Contemporary

- Jones, Inigo

- Josefa de Óbidos

- Kahlo, Frida

- Katsushika Hokusai

- Lastman, Pieter

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Luca della Robbia (or the Della Robbia Family)

- Luisa Roldán

- Markets and Auctions, Art

- Marxism and Art

- Medieval Art and Liturgy (recent approaches)

- Medieval Art and the Cult of Saints

- Medieval Art in Scandinavia, 400-800

- Medieval Textiles

- Meiji Painting

- Merovingian Period Art

- Modern Sculpture

- Monet, Claude

- Māori Art and Architecture

- Museums in Australia

- Museums of Art in the West

- Native North American Art, Pre-Contact

- Nazi Looting of Art

- New Media Art

- New Spain, Art and Architecture

- Pacific Art, Contemporary

- Palladio, Andrea

- Parthenon, The

- Paul Gauguin

- Performance Art

- Perspective from the Renaissance to Post-Modernism, Histor...

- Peter Paul Rubens

- Philip II and El Escorial

- Photography, History of

- Pollock, Jackson

- Polychrome Sculpture in Early Modern Spain

- Postmodern Architecture

- Pre-Hispanic Art of Columbia

- Psychoanalysis, Art and

- Qing Dynasty Painting

- Rembrandt van Rijn

- Renaissance and Renascences

- Renaissance Art and Architecture in Spain

- Rimpa School

- Rivera, Diego

- Rodin, Auguste

- Romanticism

- Science and Conteporary Art

- Sculpture: Method, Practice, Theory

- South Asia and Allied Textile Traditions, Wall Painting of

- South Asia, Modern and Contemporary Art of

- South Asia, Photography in

- South Asian Architecture and Sculpture, 13th to 18th Centu...

- South Asian Art, Historiography of

- The Art of Medieval Sicily and Southern Italy through the ...

- The Art of Southern Italy and Sicily under Angevin and Cat...

- Theory in Europe to 1800, Art

- Timurid Art and Architecture

- Turner, Joseph Mallord William

- van Gogh, Vincent

- Warburg, Aby

- Warhol, Andy

- Wari (Huari) Art and Architecture

- Wittelsbach Patronage from the late Middle Ages to the Thi...

- Women, Art, and Art History: Gender and Feminist Analyses

- Yuan Dynasty Art

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.151.9]

- 185.80.151.9

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Impressionism: art and modernity.

Garden at Sainte-Adresse

Claude Monet

Porte de la Reine at Aigues-Mortes

Jean-Frédéric Bazille

La Grenouillère

The Bridge at Villeneuve-la-Garenne

Alfred Sisley

Edouard Manet

Madame Georges Charpentier (Marguérite-Louise Lemonnier, 1848–1904) and Her Children, Georgette-Berthe (1872–1945) and Paul-Émile-Charles (1875–1895)

Auguste Renoir

The Monet Family in Their Garden at Argenteuil

The Dance Class

Edgar Degas

Mademoiselle Bécat at the Café des Ambassadeurs, Paris

Côte des Grouettes, near Pontoise

Camille Pissarro

Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Etruscan Gallery

Allée of Chestnut Trees

Young Woman Seated on a Sofa

Berthe Morisot

Two Young Girls at the Piano

Dancers in the Rehearsal Room with a Double Bass

Young Girl Bathing

Young Woman Knitting

The Garden of the Tuileries on a Spring Morning

Margaret Samu Institute of Fine Arts, New York University

October 2004

In 1874, a group of artists called the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, Printmakers, etc. organized an exhibition in Paris that launched the movement called Impressionism. Its founding members included Claude Monet , Edgar Degas , and Camille Pissarro, among others. The group was unified only by its independence from the official annual Salon , for which a jury of artists from the Académie des Beaux-Arts selected artworks and awarded medals. The independent artists, despite their diverse approaches to painting, appeared to contemporaries as a group. While conservative critics panned their work for its unfinished, sketchlike appearance, more progressive writers praised it for its depiction of modern life. Edmond Duranty, for example, in his 1876 essay La Nouvelle Peinture (The New Painting), wrote of their depiction of contemporary subject matter in a suitably innovative style as a revolution in painting. The exhibiting collective avoided choosing a title that would imply a unified movement or school, although some of them subsequently adopted the name by which they would eventually be known, the Impressionists. Their work is recognized today for its modernity, embodied in its rejection of established styles, its incorporation of new technology and ideas, and its depiction of modern life.

Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris) exhibited in 1874, gave the Impressionist movement its name when the critic Louis Leroy accused it of being a sketch or “impression,” not a finished painting. It demonstrates the techniques many of the independent artists adopted: short, broken brushstrokes that barely convey forms, pure unblended colors, and an emphasis on the effects of light. Rather than neutral white, grays, and blacks, Impressionists often rendered shadows and highlights in color. The artists’ loose brushwork gives an effect of spontaneity and effortlessness that masks their often carefully constructed compositions, such as in Alfred Sisley’s 1878 Allée of Chestnut Trees ( 1975.1.211 ). This seemingly casual style became widely accepted, even in the official Salon, as the new language with which to depict modern life.

In addition to their radical technique, the bright colors of Impressionist canvases were shocking for eyes accustomed to the more sober colors of academic painting. Many of the independent artists chose not to apply the thick golden varnish that painters customarily used to tone down their works. The paints themselves were more vivid as well. The nineteenth century saw the development of synthetic pigments for artists’ paints, providing vibrant shades of blue, green, and yellow that painters had never used before. Édouard Manet’s 1874 Boating ( 29.100.115 ), for example, features an expanse of the new cerulean blue and synthetic ultramarine. Depicted in a radically cropped, Japanese-inspired composition , the fashionable boater and his companion embody modernity in their form, their subject matter, and the very materials used to paint them.

Such images of suburban and rural leisure outside of Paris were a popular subject for the Impressionists, notably Monet and Auguste Renoir . Several of them lived in the country for part or all of the year. New railway lines radiating out from the city made travel so convenient that Parisians virtually flooded into the countryside every weekend. While some of the Impressionists, such as Pissarro, focused on the daily life of local villagers in Pontoise, most preferred to depict the vacationers’ rural pastimes. The boating and bathing establishments that flourished in these regions became favorite motifs. In his 1869 La Grenouillère ( 29.100.112 ), for example, Monet’s characteristically loose painting style complements the leisure activities he portrays. Landscapes , which figure prominently in Impressionist art, were also brought up to date with innovative compositions, light effects, and use of color. Monet in particular emphasized the modernization of the landscape by including railways and factories, signs of encroaching industrialization that would have seemed inappropriate to the Barbizon artists of the previous generation.

Perhaps the prime site of modernity in the late nineteenth century was the city of Paris itself, renovated between 1853 and 1870 under Emperor Napoleon III. His prefect, Baron Haussmann, laid the plans, tearing down old buildings to create more open space for a cleaner, safer city. Also contributing to its new look was the Siege of Paris during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), which required reconstructing the parts of the city that had been destroyed. Impressionists such as Pissarro and Gustave Caillebotte enthusiastically painted the renovated city, employing their new style to depict its wide boulevards, public gardens, and grand buildings. While some focused on the cityscapes, others turned their sights to the city’s inhabitants. The Paris population explosion after the Franco-Prussian War gave them a tremendous amount of material for their scenes of urban life. Characteristic of these scenes was the mixing of social classes that took place in public settings. Degas and Caillebotte focused on working people, including singers and dancers , as well as workmen. Others, including Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt , depicted the privileged classes. The Impressionists also painted new forms of leisure, including theatrical entertainment (such as Cassatt’s 1878 In the Loge [Museum of Fine Arts, Boston]), cafés, popular concerts, and dances. Taking an approach similar to Naturalist writers such as Émile Zola, the painters of urban scenes depicted fleeting yet typical moments in the lives of characters they observed. Caillebotte’s 1877 Paris Street, Rainy Day (Art Institute, Chicago) exemplifies how these artists abandoned sentimental depictions and explicit narratives, adopting instead a detached, objective view that merely suggests what is going on.

The independent collective had a fluid membership over the course of the eight exhibitions it organized between 1874 and 1886, with the number of participating artists ranging from nine to thirty. Pissarro, the eldest, was the only artist who exhibited in all eight shows, while Morisot participated in seven. Ideas for an independent exhibition had been discussed as early as 1867, but the Franco-Prussian War intervened. The painter Frédéric Bazille, who had been leading the efforts, was killed in the war. Subsequent exhibitions were headed by different artists. Philosophical and political differences among the artists led to heated disputes and fractures, causing fluctuations in the contributors. The exhibitions even included the works of more conservative artists who simply refused to submit their work to the Salon jury. Also participating in the independent exhibitions were Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin , whose later styles grew out of their early work with the Impressionists.

The last of the independent exhibitions in 1886 also saw the beginning of a new phase in avant-garde painting. By this time, few of the participants were working in a recognizably Impressionist manner. Most of the core members were developing new, individual styles that caused ruptures in the group’s tenuous unity. Pissarro promoted the participation of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, in addition to adopting their new technique based on points of pure color, known as Neo-Impressionism . The young Gauguin was making forays into Primitivism. The nascent Symbolist Odilon Redon also contributed, though his style was unlike that of any other participant. Because of the group’s stylistic and philosophical fragmentation, and because of the need for assured income, some of the core members such as Monet and Renoir exhibited in venues where their works were more likely to sell.

Its many facets and varied participants make the Impressionist movement difficult to define. Indeed, its life seems as fleeting as the light effects it sought to capture. Even so, Impressionism was a movement of enduring consequence, as its embrace of modernity made it the springboard for later avant-garde art in Europe.

Samu, Margaret. “Impressionism: Art and Modernity.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/imml/hd_imml.htm (October 2004)

Further Reading

Bomford, David, et al. Art in the Making: Impressionism . Exhibition catalogue.. New Haven and London: National Gallery, 1990.

Herbert, Robert L. Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988.

House, John. Monet: Nature into Art . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986.

Moffett, Charles S., et al. The New Painting: Impressionism 1874–1886 . San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1986.

Nochlin, Linda, ed. Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, 1874–1904: Sources and Documents . Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1966.

Rewald, John. The History of Impressionism . Rev. and enl. ed. . New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1961.

Tinterow, Gary, and Henri Loyrette. Origins of Impressionism . Exhibition catalogue.. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994. See on MetPublications

Related Essays

- Claude Monet (1840–1926)

- Edgar Degas (1834–1917): Painting and Drawing

- Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

- Mary Stevenson Cassatt (1844–1926)

- African Influences in Modern Art

- American Impressionism

- American Scenes of Everyday Life, 1840–1910

- Americans in Paris, 1860–1900

- Auguste Renoir (1841–1919)

- Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

- Edgar Degas (1834–1917): Bronze Sculpture

- Georges Seurat (1859–1891) and Neo-Impressionism

- Henri Matisse (1869–1954)

- Nineteenth-Century French Realism

- Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art

- Paul Gauguin (1848–1903)

- France, 1800–1900 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1800–1900 A.D.

- The United States and Canada, 1800–1900 A.D.

- 19th Century A.D.

- Academic Painting

- Arboreal Landscape

- Architecture

- Barbizon School

- French Literature / Poetry

- Great Britain and Ireland

- Impressionism

- Literature / Poetry

- Neo-Impressionism

- Oil on Canvas

- Post-Impressionism

- Primitivism

- Women Artists

Artist or Maker

- Bazille, Jean-Frédéric

- Cassatt, Mary

- Cézanne, Paul

- Degas, Edgar

- Gauguin, Paul

- Manet, Édouard

- Monet, Claude

- Morisot, Berthe

- Pissarro, Camille

- Redon, Odilon

- Renoir, Auguste

- Sisley, Alfred

- Sorolla y Bastida, Joaquin

Online Features

- The Artist Project: “George Condo on Claude Monet’s The Path through the Irises “

Summary of Dada

Dada was an artistic and literary movement that began in Zürich, Switzerland. It arose as a reaction to World War I and the nationalism that many thought had led to the war. Influenced by other avant-garde movements - Cubism , Futurism , Constructivism , and Expressionism - its output was wildly diverse, ranging from performance art to poetry, photography, sculpture, painting, and collage . Dada's aesthetic, marked by its mockery of materialistic and nationalistic attitudes, proved a powerful influence on artists in many cities, including Berlin, Hanover, Paris, New York, and Cologne, all of which generated their own groups. The movement dissipated with the establishment of Surrealism , but the ideas it gave rise to have become the cornerstones of various categories of modern and contemporary art.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Dada was the direct antecedent to the Conceptual Art movement , where the focus of the artists was not on crafting aesthetically pleasing objects but on making works that often upended bourgeois sensibilities and that generated difficult questions about society, the role of the artist, and the purpose of art.

- So intent were members of Dada on opposing all norms of bourgeois culture that the group was barely in favor of itself: "Dada is anti-Dada," they often cried. The group's founding in the Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich was appropriate: the Cabaret was named after the 18 th century French satirist, Voltaire, whose novella Candide mocked the idiocies of his society. As Hugo Ball , one of the founders of both the Cabaret and Dada wrote, "This is our Candide against the times."

- Artists like Hans Arp were intent on incorporating chance into the creation of works of art. This went against all norms of traditional art production whereby a work was meticulously planned and completed. The introduction of chance was a way for Dadaists to challenge artistic norms and to question the role of the artist in the artistic process.

- Dada artists are known for their use of readymades - everyday objects that could be bought and presented as art with little manipulation by the artist. The use of the readymade forced questions about artistic creativity and the very definition of art and its purpose in society.

Key Artists

Overview of Dada

Aiming to both to help to stop the war and to vent frustration with the nationalist and bourgeois conventions Dada artists ultimately revolutionized the artmaking of the future.

Artworks and Artists of Dada

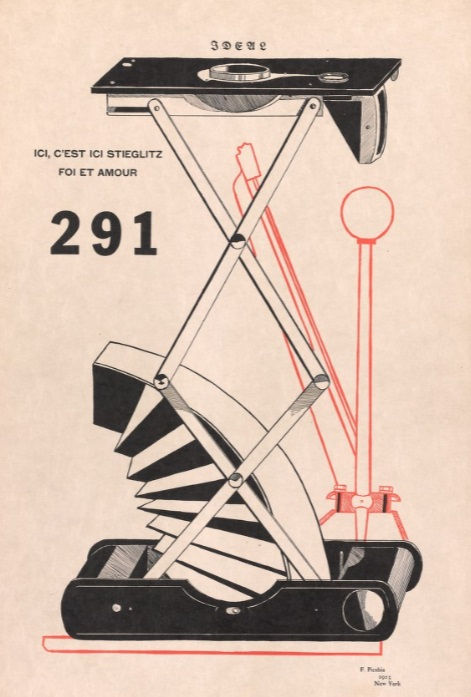

Ici, C'est Stieglitz (Here, This is Stieglitz)

Artist: Francis Picabia

Picabia was a French artist who embraced the many ideas of Dadaism and defined some himself. He very much enjoyed going against convention and re-defining himself to work in new ways a number of times over a career that spanned over 45 years. At first he worked closely with Alfred Stieglitz, who gave him his first one-man show in New York City. But later he criticized Stieglitz, as is evident in this "portrait" of the gallerist as a bellows camera, an automobile gear shift, a brake lever, and the word "IDEAL" above the camera in Gothic lettering. The fact that the camera is broken and the gear shift is in neutral has been thought to symbolize Stieglitz as worn out, while the contrasting decorative Gothic wording refers to the outdated art of the past. The drawing is one of a series of mechanistic portraits and imagery created by Picabia that, ironically, do not celebrate modernity or progress, but, like similar mechanistic works by Duchamp, show that such subject matter could provide an alternative to traditional artistic symbolism.

Ink, graphite, and cut-and-pasted painted and printed papers on paperboard - Alfred Stieglitz Collection

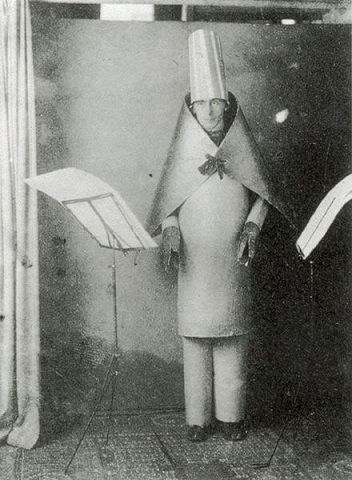

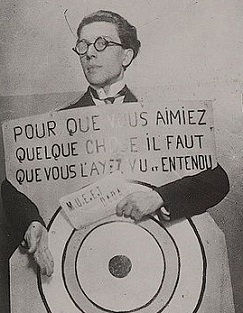

Reciting the Sound Poem "Karawane"

Artist: Hugo Ball

Ball designed this costume for his performance of the sound-poem, "Karawane," in which nonsensical syllables uttered in patterns created rhythm and emotion, but nothing resembling any known language. The resulting lack of sense was meant to reference the inability of European powers to solve their diplomatic problems through the use of rational discussion, thus leading to World War I - equating the political situation to the biblical episode of the Tower of Babel. Ball's strange costume is meant to further distance him from his audience and his everyday surroundings, making his speech even more foreign and exotic. Ball described his costume: "My legs were in a cylinder of shiny blue cardboard, which came up to my hips so that I looked like an obelisk. Over it I wore a huge coat cut out of cardboard, scarlet inside and gold outside. It was fastened at the neck in such a way that I could give the impression of wing-like movement by raising and lowering my elbows. I also wore a high, blue-and-white-striped witch doctor's hat."

Photograph - Kunsthaus Zürich (reproduction of original photograph)

Untitled (Squares Arranged according to the Laws of Chance)

Artist: Hans Arp

Hans Arp made a series of collages based on chance, where he would stand above a sheet of paper, dropping squares of contrasting colored paper on the larger sheet's surface, and then gluing the squares wherever they fell onto the page. The resulting arrangement could then provoke a more visceral reaction, like the fortune telling from I-Ching coins that interested Arp, and perhaps provide a further creative spur. Apparently, this technique arose when Arp became frustrated by attempts to compose more formal geometric arrangements. Arp's chance collages have come to represent Dada's aim to be "anti-art" and their interest in accident as a way to challenge traditional art production techniques. The lack of artistic control represented in this work would also become a defining element of Surrealism as that group tried to find paths into the unconscious whereby intellectual control on creativity was undermined.

Cut-and-pasted colored paper - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

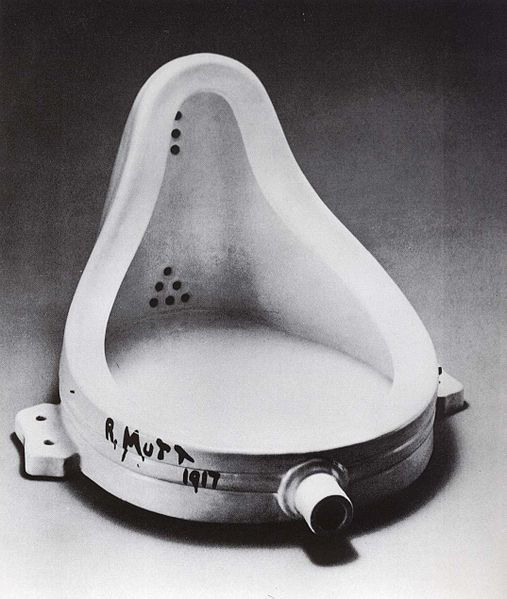

Artist: Marcel Duchamp

Duchamp was the first artist to use a readymade and his choice of a urinal was guaranteed to challenge and offend even his fellow artists. There is little manipulation of the urinal by the artist other than to turn it upside-down and to sign it with a fictitious name. By removing the urinal from its everyday environment and placing it in an art context, Duchamp was questioning basic definitions of art as well as the role of the artist in creating it. With the title, Fountain , Duchamp made a tongue in cheek reference to both the purpose of the urinal as well to famous fountains designed by Renaissance and Baroque artists. In its path-breaking boldness the work has become iconic of the irreverence of the Dada movement towards both traditional artistic values and production techniques. Its influence on later 20 th -century artists such as Jeff Koons, Robert Rauschenberg, Damien Hirst, and others is incalculable.

Urinal - The Philadelphia Museum of Art

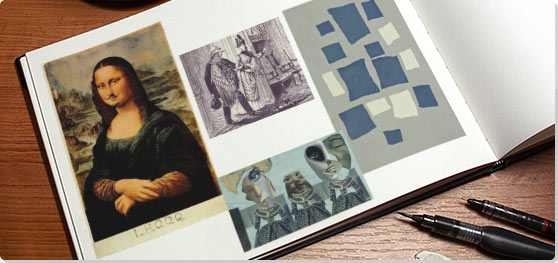

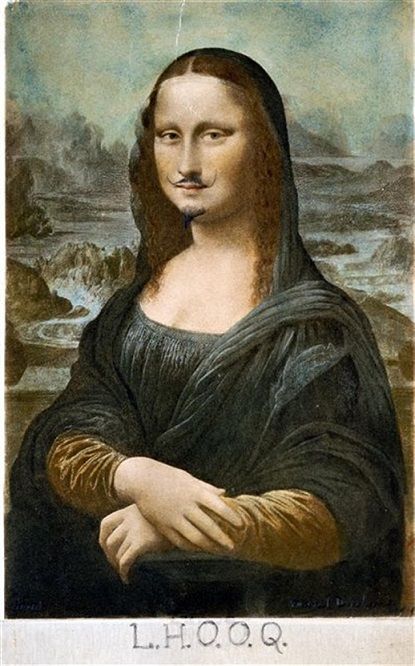

This work is a classic example of Dada irreverence towards traditional art. Duchamp transformed a cheap postcard of the Mona Lisa (1517) painting, which had only recently been returned to the Louvre after it was stolen in 1911. While it was already a well-known work of art, the publicity from the theft ensured that it became one of the most revered and famous works of art: art with a capital A. On the postcard, Duchamp drew a mustache and a goatee onto Mona Lisa's face and labeled it L.H.O.O.Q. If the letters are pronounced as they would be by a native French speaker, it would sound as if one were saying "Elle a chaud au cul," which loosely translates as "She has a hot ass." Again, Duchamp managed to offend everyone while also posing questions that challenged artistic values, artistic creativity, and the overall canon.

Collotype - Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

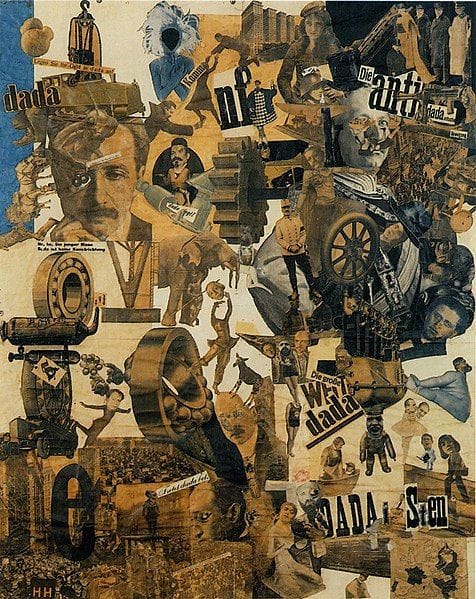

Cut with a Kitchen Knife Dada through the Last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany

Artist: Hannah Höch

Hannah Höch is known for her collages and photomontages composed from newspaper and magazine clippings as well as sewing and craft designs often pulled from publications she contributed to at the Ullstein Press. As part of Club Dada in Berlin, Hoch unabashedly critiqued German culture by literally slicing apart its imagery and reassembling it into vivid, disjointed, emotional depictions of modern life. The title of this work, refers to the decadence, corruption, and sexism of pre-war German culture. Larger and more political than her typical montages, this fragmentary anti-art work highlights the polarities of Weimer politics by juxtaposing images of establishment people with intellectuals, radicals, entertainers, and artists. Recognizable faces include Marx and Lenin, Pola Negri, and Kathe Kollwitz. The map of Europe that identifies the countries in which women had already achieved the right to vote suggests that the newly enfranchised women of Germany would soon "cut" through the male "beer-belly" culture. Her inclusion of commercially produced designs in her montages broke down distinctions between modern art and crafts, and between the public sphere and domesticity.

Cut paper collage - National Gallery, State Museum of Berlin

The Spirit of our Time

Artist: Raoul Hausmann

This assemblage represents Hausmann's disillusion with the German government and their inability to make the changes needed to create a better nation. It is an ironic sculptural illustration of Hausmann's belief that the average member of (corrupt) society "has no more capabilities than those which chance has glued to the outside of his skull; his brain remains empty". Thus Hausmann's use of a hat maker's dummy to represent a blockhead who can only experience that which can be measured with the mechanical tools attached to its head - a ruler, a tape measure, a pocket watch, a jewelry box containing a typewriter wheel, brass knobs from a camera, a leaky telescopic beaker of the sort used by soldiers during the war, and an old purse. Thus, there is no ability for critical thinking or subtlety. With its blank eyes, the dummy is a narrow-minded, blind automaton.

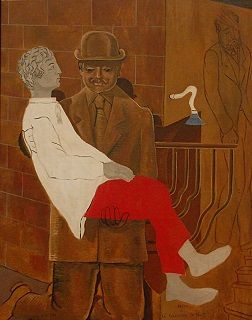

Chinese Nightingale

Artist: Max Ernst

Ernst's use of photomontage was less political and more poetic than those of other German Dadaists, creating images based on random associations of juxtaposed images. He described his technique as the "systematic exploitation of the chance or artificially provoked confrontation of two or more mutually alien realities on an obviously inappropriate level - and the poetic spark that jumps across when these realities approach each other". Between 1919 and 1920, Ernst made a series of collages that combined illustrations of war machinery with those of human limbs and various accessories to create strange hybrid creatures. Thus the fear generated by weaponry was combined with benign elements and often lyrical titles. This catharsis no doubt had a personal resonance for Ernst who was injured in the war by the recoil of a gun. In The Chinese Nightingale , for example, the arms and fan of an oriental dancer act as the limbs and headdress of a creature whose body is an English bomb. An eye has been added above the bracket on the side of the bomb to create the effect of a bizarre bird. Thus Ernst's whimsy defuses the fear associated with bombs. The title was taken from a fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen.

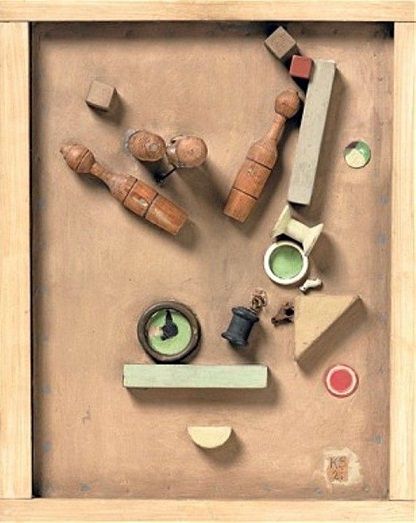

Merzpicture 46A. The Skittle Picture

Artist: Kurt Schwitters

This is an early example of assemblage in which two and three dimensional objects are combined. The word "Merz," which Schwitters used to describe his art practice as well as his individual pieces, is a nonsensical word, like Dada, that Schwitters culled from the word "commerz", the meaning of which he described as follows: "In the war, things were in terrible turmoil. What I had learned at the academy was of no use to me.... Everything had broken down and new things had to be made out of the fragments; and this is Merz". In his Merzpictures , which have been called "psychological collages," he arranged found objects - usually detritus - in simple compositions that transformed trash into beautiful works of art. Whether the materials were string, a ticket stub, or a chess piece, Schwitters considered them to be equal with any traditional art material. Merz, however, is not ideological, dogmatic, hostile, or political as is much of Dada art.

Assemblage of wood, oil, metal, board on board, with artist's frame - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

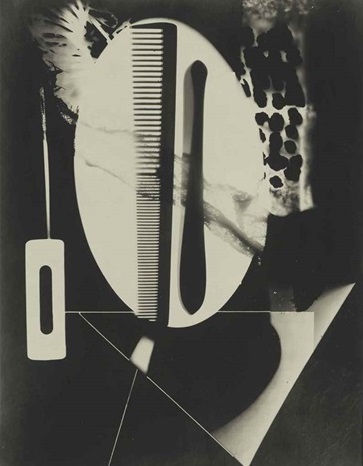

Artist: Man Ray

Man Ray was an American artist who spent most of his working years in France. He termed his experiments rayographs , which are photographs made by placing objects directly on sensitized paper and exposing them to light. The random objects leave behind a shadowy imprint that dissociates them from their original context. These works, with their often strange combination of objects and ghostly appearance, reflected the Dada interest in chance and the nonsensical. As other Dada artists liberated painting and sculpture from its traditional role as a representational art, Ray did the same for photography - in his hands it was no longer a mirror of nature. Ray's discovery of the rayograph was itself based on chance: after he had forgotten to expose an image and was waiting for an image to appear in the dark room, he placed some objects on the photo paper. Upon seeing them, Tzara called them "pure Dada creations" and they were an instant hit among like-minded artists. While Man Ray did not invent the photogram, his were the most famous.

Beginnings of Dada

Switzerland was neutral during WWI with limited censorship and it was in Zürich that Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings founded the Cabaret Voltaire on February 5, 1916 in the backroom of a tavern on Spiegelgasse in a seedy section of the city. In order to attract other artists and intellectuals, Ball put out a press release that read, "Cabaret Voltaire. Under this name a group of young artists and writers has formed with the object of becoming a center for artistic entertainment. In principle, the Cabaret will be run by artists, guests artists will come and give musical performances and readings at the daily meetings. Young artists of Zürich, whatever their tendencies, are invited to come along with suggestions and contributions of all kinds." Those who were present from the beginning in addition to Ball and Hennings were Hans Arp , Tristan Tzara , Marcel Janco , and Richard Huelsenbeck .

In July of that year, the first Dada evening was held at which Ball read the first manifesto. There is little agreement on how the word Dada was invented, but one of the most common origin stories is that Richard Huelsenbeck found the name by plunging a knife at random into a dictionary. The term "dada" is a colloquial French term for a hobbyhorse, yet it also echoes the first words of a child, and these suggestions of childishness and absurdity appealed to the group, who were keen to put a distance between themselves and the sobriety of conventional society. They also appreciated that the word might mean the same (or nothing) in all languages - as the group was avowedly internationalist.

The aim of Dada art and activities was both to help to stop the war and to vent frustration with the nationalist and bourgeois conventions that had led to it. Their anti-authoritarian stance made for a protean movement as they opposed any form of group leadership or guiding ideology.

The Spread of Dada

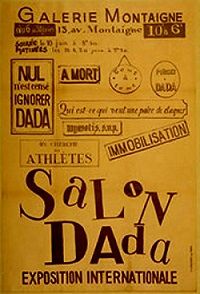

The artists in Zürich published a Dada magazine and held art exhibits that helped spread their anti-war, anti-art message. In 1917, after Ball left for Bern to pursue journalism, Tzara founded Galerie Dada on Bahnhofstrasse where further Dada evenings were held along with art exhibits. Tzara became the leader of the movement and began an unrelenting campaign to spread Dada ideas, showering French and Italian writers and artists with letters. The group published an art and literature review entitled Dada starting in July 1917 with five editions from Zürich and two final ones from Paris. Their art was focused on performance and printed matter.

Once the war ended in 1918, many of the artists returned to their home countries, helping to further spread the movement. The end of Dada in Zürich followed the Dada 4-5 event in April 1919 that by design turned into a riot, something that Tzara thought furthered the aims of Dada by undermining conventional art practices through audience involvement in art production. The riot, which began as a Dada event, was one of the most significant. It attracted over 1000 people and began with a conservative speech about the value of abstract art that was meant to anger the crowd. This was followed by discordant music and then several readings that encouraged crowd participation until the crowd lost control and began to destroy several of the props. Tzara described it thus: "the tumult is unchained hurricane frenzy siren whistles bombardment song the battle starts out sharply, half the audience applaud the protestors hold the hall . . . chairs pulled out projectiles crash bang expected effect atrocious and instinctive . . . Dada has succeeded in establishing the circuit of absolute unconsciousness in the audience which forgot the frontiers of education of prejudices, experienced the commotion of the New. Final victory of Dada." For Tzara the key to the success of a riot was audience involvement so that attendees were not just onlookers of art, but became involved in its production. This was a total negation of traditional art.

Soon after this, Tzara traveled to Paris, where he met André Breton and began formulating the theories that Breton would eventually put together in Surrealism . Dadaists did not self-consciously declare micro-regional movements; the spread of Dada throughout various European cities and into New York can be attributed to a few key artists, and each city in turn influenced the aesthetics of their respective Dada groups.

In 1917, Huelsenbeck returned from Zürich to found Club Dada in Berlin, which was active from 1918 to 1923, and included attendees such as Johannes Baader , George Grosz , Hannah Höch , and Raoul Hausmann . Closer to a war zone, the Berlin Dadaists came out publicly against the Weimar Republic and their art was more political: satirical paintings and collages that featured wartime imagery, government figures, and political cartoon clippings recontextualized into biting commentaries. In February of 1918, Huelsenbeck gave his first Dada speech in Berlin and several journals, including Club Dada and Der Dada , were published that year along with a manifesto in April. The photomontage technique was developed in Berlin during this period. In 1920 Hausmann and Huelsenbeck give a lecture tour in Dresden, Hamburg, Leipzig, and Prague. The "Erste Internationale Dada-Messe" was held in June.

Kurt Schwitters, excluded from the Berlin group likely because of his links to Der Sturm gallery and the Expressionist style, both of which were seen as antithetical to Dada because of their Romanticism and focus on aesthetics, formed his own Dada group in Hannover in 1919, though he was its only practitioner. His Merz , as he termed his art, was less politically oriented than that of the Club Dada; his works instead examine modernist preoccupations with shape and color.

Another Dada group was formed in Cologne in 1918 by Max Ernst and Johannes Theodor Baargeld. Importantly, Hans Arp joined the next year and made breakthroughs in his collage experiments. Their exhibits focused on anti-bourgeois and nonsensical art. In 1920, one such exhibit was closed down by the police. By 1922, German Dada was winding down. In that year, Ernst left Cologne for Paris, thus dissolving that group. Others became interested in other movements. A "Congress of the Constructivists", for example, was held in Weimar in October of 1922, which was attended by a number of the German Dadaists and in 1924, Breton published the Surrealist manifesto after which many of the remaining Dadaists joined that movement. Schwitter's Merz publication continued sporadically for several years.

After hearing of the Dada movement in Zürich, a number of Parisian artists including Andre Breton, Louis Aragon , Paul Eluard , and others become interested. In 1919 Tzara left Zürich for Paris and Arp arrived there from Cologne the next year; a "Dada festival" took place in May 1920 after many of the originators of the movement had converged there. There were several demonstrations, exhibitions, and performances organized along with manifestos and journals published, including Dada and Le Cannibale .

Picabia and Breton withdrew from the movement in 1921 and Picabia published a special issue of 391 in which he claimed that Paris Dada had become the thing it originally fought against: a mediocre established movement. He wrote: "The Dada spirit really only existed between 1913 and 1918 . . . In wishing to prolong it, Dada became closed . . . Dada, you see, was not serious... and if certain people take it seriously now, it's because it is dead! . . . One must be a nomad, pass through ideas like one passes through countries and cities." Paris Dada published a counter-attack under the direction of Tzara. Two final Dada stage performances are held in Paris in 1923 before the group collapsed into internal infighting and ceded to Surrealism.

Marcel Duchamp provided a crucial creative link between the Zürich Dadaists and Parisian proto-Surrealists, like Breton. The Swiss group considered Marcel Duchamp's readymades to be Dada artworks, and they appreciated Duchamp's humor and refusal to define art.

Like Zürich during the war, New York City was a refuge for writers and artists. Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia arrived in the city only days apart in June of 1915 and soon after met Man Ray . Duchamp served as a critical interlocutor, bringing the notion of anti-art to the group where it took a decidedly mechanistic turn. One of his most important pieces, The Large Glass or Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even , was begun in New York in 1915 and is considered to be a major milestone for its depiction of a strange, erotic drama using mechanical forms.

By 1916 Duchamp, Picabia, and Man Ray were joined by the American artist Beatrice Wood and the writers Henri-Pierre Roche and Mina Loy. Much of their anti-art activity took place in Alfred Stieglitz's 291 gallery and at the studio of Walter and Louise Arensberg. Their publications, such as The Blind Man , Rongwrong , and New York Dada challenged conventional museum art with more humor and less bitterness than European groups. It was during this period that Duchamp began exhibiting readymades (found objects) such as a bottle rack, and got involved with the Society of Independent Artists. In 1917 he submitted Fountain to the Society of Independent Artists show.

Picabia's travels helped tie New York, Zürich and Paris groups together during the Dadaist period. From 1917 through 1924 he also published the Dada periodical 391 , which was modeled on Stieglitz's 291 periodical. Picabia's 391 was first published in Barcelona, then in various cities including New York, Zürich, and Paris, depending on his own place of residence and with help from fellow artists and friends in the various cities. The periodical was mainly literary, however, with Picabia being the prime contributor. The 1918 Dada Manifesto had declared: "Every page must explode, whether through seriousness, profundity, turbulence, nausea, the new, the eternal, annihilating nonsense, enthusiasm for principles, or the way it is printed. Art must be unaesthetic in the extreme, useless, and impossible to justify." He broke away from Dada in 1921 as mentioned above. In addition to the special issue of 391 in which he attacked Paris Dada in 1921, in the final issue of 391 in 1924 Picabia accuses Surrealism of being a fabricated movement, writing that "artificial eggs don't make chickens."

Dada: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Dada artworks present intriguing overlaps and paradoxes in that they seek to demystify artwork in the populist sense but nevertheless remain cryptic enough to allow the viewer to interpret works in a variety of ways. Some Dadaists portrayed people and scenes representationally in order to analyze form and movement. Others, like Kurt Schwitters and Man Ray , practiced abstraction to express the metaphysical essence of their subject matter. Both modes sought to deconstruct daily experience in challenging and rebellious ways. The key to understanding Dada works lies in reconciling the seemingly silly, slapdash styles with the profound anti-bourgeois message. Tzara especially fought the assumption that Dada was a statement; yet Tzara and his fellow artists became increasingly agitated by politics and sought to incite a similar fury in Dada audiences.

Irreverence

Irreverence was a crucial component of Dada art, whether it was a lack of respect for bourgeois convention, government authorities, conventional production methods, or the artistic canon. Each group varied slightly in their focus, with the Berlin group being the most anti-government and the New York group being the most anti-art. Of all the groups, the Hannover group was likely the most conservative.

Readymades and Assemblage

A readymade was simply an object that already existed and was commandeered by Dada artists as a work of art, often in the process combined with another readymade, as in Duchamp's Bicycle Wheel , thus creating an assemblage . The pieces were often chosen and assembled by chance or accident to challenge bourgeois notions about art and artistic creativity. Indeed, it is difficult to completely separate conceptually the Dada interest in chance with their focus on readymades and assemblage. Several of the readymades and assemblages were bizarre, a quality that made it easy for the group to merge eventually with Surrealism. Other artists who worked with readymades and assemblages include Ernst, Man Ray, and Hausmann.

Chance was a key concept underpinning most of Dada art from the abstract and beautiful compositions of Schwitters to the large assemblages of Duchamp. Chance was used to embrace the random and the accidental as a way to release creativity from rational control, with Arp being one of the earliest and best-known practitioners. Schwitters, for example, gathered random bits of detritus from a variety of locales, while Duchamp welcomed accidents such as the crack that occurred while he was making The Large Glass . In addition to loss of rational control, Dada lack of concern with preparatory work and the embrace of artworks that were marred fit well with the Dada irreverence for traditional art methods.

Wit and Humor

Tied closely to Dada irreverence was their interest in humor, typically in the form of irony. In fact, the embrace of the readymade is key to Dada's use of irony as it shows an awareness that nothing has intrinsic value. Irony also gave the artists flexibility and expressed their embrace of the craziness of the world thus preventing them from taking their work too seriously or from getting caught up in excessive enthusiasm or dreams of utopia. Their humor is an unequivocal YES to everything as art.

Later Developments - After Dada

As detailed above, after the disbanding of the various Dada groups, many of the artists joined other art movements - in particular Surrealism . In fact, Dada's tradition of irrationality and chance led directly to the Surrealist love for fantasy and expression of the imaginary. Several artists were members of both groups, including Picabia, Arp, and Ernst since their works acted as a catalyst in ushering in an art based on a relaxation of conscious control over art production. Though Duchamp was not a Surrealist, he helped to curate exhibitions in New York that showcased both Dada and Surrealist works.

Dada, the direct antecedent to the Conceptual Art movement , is now considered a watershed moment in 20 th -century art. Postmodernism as we know it would not exist without Dada. Almost every underlying postmodern theory in visual and written art as well as in music and drama was invented or at least utilized by Dada artists: art as performance, the overlapping of art with everyday life, the use of popular culture, audience participation, the interest in non-Western forms of art, the embrace of the absurd, and the use of chance.

A large number of artistic movements since Dada can trace their influence to the anti-establishment group. Other than the obvious examples of Surrealism , Neo-Dada , and Conceptual art , these would include Pop art , Fluxus , the Situationist International , Performance art , Feminist art , and Minimalism . Dada also had a profound influence on graphic design and the field of advertising with their use of collage.

Useful Resources on Dada

- Dalí and The Surrealists - Master Marketers Top 10 marketing stunts by Tristan Tzara, Andre Breton, and Salvador Dalí.

- Dada: Zürich, Berlin, Hannover, Cologne, New York, Paris Our Pick By Dorothea Dietrich, Brigid Doherty, Sabine Kriebel, Leah Dickerman

- The Dada Painters and Poets: An Anthology, Second Edition (Paperbacks in Art History) Our Pick By Robert Motherwell

- Dada: Art and Anti-Art (World of Art) By Hans Richter

- Dada & Surrealism (Art and Ideas) By Matthew Gale

- The DADA Reader: A Critical Anthology By Dawn Ades

- International Dada Archive Project by The University of Iowa Libraries

- From Dada to Surrealism - Review By Phillippe Dagen / The Guardian Weekly (UK) / July 19, 2011

- No Nonsense about Dada - Review of MoMA Exhibition Our Pick By Clare Hurley / World Socialist Web Site / September 18, 2006

- Our Art Belongs to Dada Our Pick By Martin Filler / Departures / March/April 2006

- Dada's Big Mama By Leah Ollman / Los Angeles Times / June 22, 1997

Similar Art

The City Rises (1910)

Still Life with Chair Caning (1912)

Theater Piece No. 1 (1952)

Related artists.

Related Movements & Topics

Content compiled and written by The Art Story Contributors

Edited and published by The Art Story Contributors

Ask Yale Library

My Library Accounts

Find, Request, and Use

Help and Research Support

Visit and Study

Explore Collections

Art History Research at Yale: How to Research Art

- How to Research Art

- Primary Sources

- Biographical Information

- Dissertations & Theses

- Image & Video Resources

- How to Cite Your Sources

- Copyright and Fair Use

- Collecting and Provenance Research This link opens in a new window

- How to Find Images

Books about Writing

Starting Your Research

Before you begin conducting research, it’s important to ask yourself a few questions:

1. What’s my topic? Review your assignment closely and choose an appropriate topic. Is this topic about a single artist or an art movement? Is it a study of one work or a body of works? How long is the paper—will you need a basic overview, or detailed analysis? Guiding questions such as these can help you determine what the best approach to your research will be. If you aren’t sure where to start, you can ask your professor for guidance, and you can always contact an Arts Librarian using their contact information on this page.

2. Which sources are best for my topic? With infinite time, you would want to read everything available, but there are often resources that are more applicable depending on your research topic. How to Find Art Resources provides more detailed information about choosing helpful sources based on general topics. Watch this video for brief instructions on how to find information on a work of art at the Yale University Art Gallery.

3. How will I manage and cite my sources? When you turn in your paper or presentation, you will need to provide citations in keeping with the preferred citation style. Keeping on top of your citations as you work through your research will save time and stress when you are finishing your project. All Yale students have access to tools to keep citations organized, generate a bibliography, and create footnotes/endnotes. For a quick guide, see How to Cite Your Sources , and more guidance is available on the Citation Management guide .

Related Guides for Art History Research at Yale

- Religion and the Arts

- History of British Art

Arts Librarian

- << Previous: Home

- Next: How to Find Art Resources >>

- Last Updated: Aug 17, 2023 11:33 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/arthistoryresearch

Site Navigation

P.O. BOX 208240 New Haven, CT 06250-8240 (203) 432-1775

Yale's Libraries

Bass Library

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Classics Library

Cushing/Whitney Medical Library

Divinity Library

East Asia Library

Gilmore Music Library

Haas Family Arts Library

Lewis Walpole Library

Lillian Goldman Law Library

Marx Science and Social Science Library

Sterling Memorial Library

Yale Center for British Art

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

@YALELIBRARY

Yale Library Instagram

Accessibility Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Giving Privacy and Data Use Contact Our Web Team

© 2022 Yale University Library • All Rights Reserved

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry