Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 08 July 2022

A critical examination of a community-led ecovillage initiative: a case of Auroville, India

- Abhishek Koduvayur Venkitaraman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8515-257X 1 &

- Neelakshi Joshi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8947-1893 2

Climate Action volume 1 , Article number: 15 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

7112 Accesses

2 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Sustainability

Human settlements across the world are attempting to address climate change, leading to changing paradigms, parameters, and indicators for defining the path to future sustainability. In this regard, the term ecovillage has been increasingly used as models for sustainable human settlements. While the term is new, the concept is an old one: human development in harmony with nature. However, materially realizing the concept of an ecovillage is not without challenges. These include challenges in scaling up and transferability, negative regional impacts and struggles of functioning within larger capitalistic and growth-oriented systems. This paper presents the case of Auroville, an early attempt to establish an ecovillage in Southern India. We draw primarily from the ethnographic living and working experience of the authors in Auroville as well as published academic literature and newspaper articles. We find that Auroville has proven to be a successful laboratory for providing bottom-up, low cost and context-specific ecological solutions to the challenges of sustainability. However, challenges of economic and social sustainability compound as the town attempts to scale up and grow.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Sustainability and social transformation: the role of ecovillages in confluence with the pluriverse of community-led alternatives

Reviving natural history, building ecological civilisation: the philosophy and social significance of the Natural History Revival Movement in contemporary China

The paradox of collective climate action in rural U.S. ecovillages: ethnographic reflections and perspectives

Introduction.

Scientists have repeatedly argued and emphasized for an equilibrium between human development and the basic ecological support systems of the planet (IPCC 2014 ; United Nations 1987 ). Human settlements have been important in this regard as places of concentrated human activity (Edward & Matthew E, 2010 ; Scott and Storper 2015 ). Settlement planning has responded to this call through visions of the eco-city as a proposal for building the city like a living system with a land use pattern supporting the healthy anatomy of the whole city and enhance its biodiversity, while resonating its functions with sustainability (Barton 2013 ; Register 1987 ; Roseland 1997 ). In planning practice, this means balancing between economic growth, social justice, and environmental well-being (Campbell 1996 ). However, the concept of eco-cities remains top-down in its approach with city authorities taking a lead in involving the civil society and citizens to implement the city’s environment plan (Joss 2010a , b ).

Contrary to the idea of eco-cities, ecovillages are small-scale, bottom-up sites for experimentation around sustainable living. Ecovillages resonate the same core principles of an eco-city but combine the social, ecological, and spiritual aspects of human existence (Gilman 1991 ). Findhorn Ecovillage in Scotland is one of the oldest and most prominent ecovillages in the world and has collaborations with the United Nations and was named as a best practice community (Lockyer and Veteto 2013 ).

Another notable example is the Transitions Town movement that started in Totnes, United Kingdom but has now spread all over the world (Hopkins 2008 ; Smith 2011 ). The movement focuses upon supporting community-led responses to peak oil and climate change, building resilience and happiness. Additionally, it emphasizes rebuilding local agriculture and food production, localizing energy production along with rediscovering local building materials in the context of zero energy building (Hopkins 2008 ). Ecological districts within the urban fabric are also termed as ecovillages (Wolfram 2017 ).

Ecovillages are intentional communities characterized by alternative lifestyles, values, economics and governance systems (Joss 2010a , b ; Ergas 2010 ). At the same time ecovillages are located within and interact with growth-oriented capitalistic systems (Price et al. 2020 ). This dichotomy presents a challenge for ecovillages as they put ideas of sustainability transformation into practice. We explore some of these contradictions through the case study of Auroville, an ecovillage located in southern India. A discussion on the gaps between the ideas of an ecovillage against their lived reality throws light upon the challenges that ecovillages face when they attempt to grow. We begin by elaborating the key characteristics of ecovillages in the “Characteristics of ecovillages” section. We then present our material and methods in the “Methodology” section. Furthermore, we use the key characteristics of an ecovillage as a framework for analysing and discussing Auroville in the “Auroville, an ecovillage in South India” and “Discussion” sections. We conclude with a reflection on the concept of ecovillages.

Characteristics of ecovillages

The concept of an ecovillage is broad and has multiple interpretations. Based on a reading of the existing literature on ecovillages, we summarize some of their key characteristics here:

Alternative lifestyles and values : Ecovillage can be seen as intentional communities (Ergas 2010 ) and social movements which have a common stance against unsustainable modes of living and working (Kirby 2003 ; Snow et al. 2004 ). Ecovillages advocate for achieving an alternate lifestyle involving a considerable shift in power from globalized values to those internalized in local community autonomy. Therefore many ecovillages aspire to restructure power distribution and foster a spirit of collective and transparent decision-making (Boyer 2015 ; Cunningham and Wearing 2013 ). However, it is difficult to convince many people to believe in a common value system since the vision is to establish a world that is not only ecologically sustainable but also personally rewarding in terms of self-sacrifice for a good cause (Anderson 2015 ).

Governance : ecovillages tend to rely on a community-based governance and there is an assumption that the local and regional communities respond more effectively to local environmental problems since these problems pertain to the local context and priorities (Van Bussel et al. 2020 ). In a community-based governance system, activities are organized and carried out through participatory democracy committed to consensual decision-making. However, participatory democracy has its own set of problems. Consensual decision-making is time-consuming, and the degree of participation tends to vary from time to time (Fischer 2017 ). Participatory processes have also been criticized on the grounds for slowing down the decision-making process and resulting in a weak final agreement which doesn’t balance competing interests (Alterman et al. 1984 ).

Economic models in an ecovillages : ecovillages have attempted to combine economic objectives along with the overall well-being of people and have experimented with budgetary solutions appealing to a wider society (Hall 2015 ). As grassroots initiatives, ecovillages have advocated and practised living in community economies (Roelvink and Gibson-Graham 2009 ) and have influenced twentieth century economic practices beyond their geographical boundaries (Boyer 2015 ). Due to the emphasis on sharing in ecovillages, they can be considered to accommodate diverse economies (Gibson-Graham 2008 ) where human needs are met through relational exchanges and non-monetary practices, highlighting strong social ties (Waerther 2014 ). In some ecovillages, living expenses are reduced by sharing costly assets and saving cost on building materials by bulk buying and growing food for community consumption and sale (Pickerill 2017 ). These economic models have their own merit but are perhaps insufficient for the long-term economic sustainability of ecovillages (Price et al. 2020 ). Eventually, ecovillages might have to rely on external sources to import goods and services which cannot be produced on-site. This contradicts the ecovillage principles of being a self-reliant economy, reduction of its carbon footprint and minimizing resource consumption, thus implying a dependence on the market economy of the region (Bauhardt 2014 ).

Self-sufficiency : fulfilling the community’s needs within the available resources is a cornerstone principle for many ecovillages (Gilman 1991 ). This is often achieved through organic farming, permaculture, renewable energy and co-housing. Such measures are an attempt to offset and mitigate unsustainable development and limit the ecovillage’s ecological footprint (Litfin 2009 ). The initial small scale of the community often allows for this. However, as ecovillages grow in size and complexity, the interconnectedness and inter-dependence to the surrounding space become more apparent (Joss 2010a , b ). Examples include drawing resources from central energy and water systems (Xue 2014 ). Furthermore, ecovillages might turn out to be desirable places to live, with better quality of life, driving up land and property prices in the region as well as carbon emissions with additional visitors (Mössner and Miller 2015 ). Furthermore, in their role as catalysts of change in transforming society, ecovillages need to interact with their external surroundings and neighbouring communities, the municipalities, and the state and national level policies (Dawson and Lucas 2006 ; Kim 2016 ). This is particularly relevant in the Global South, where the ecovillage development has the potential to drive regional-scale sustainable development.

The characteristics of an ecovillage, however, do not exist in a geographical vacuum. Scholarly understanding of ecovillages as bottom-up efforts to drive sustainability transitions largely draw from the experiences of the Global North (Wagner 2012 ). Such ecovillage models often challenge the dominant capitalistic paradigm of post-industrial development, overconsumption and growth. Locating ecovillages in the Global South requires an expansion or re-evaluation of their larger socio-economic context as well as their socio-ecological impacts (Dias et al. 2017 ; Litfin 2009 ) .

To build upon the opportunities and challenges of ecovillages, locating them within the context of the Global South, we present the case of Auroville, an ecovillage located in southern India.

Methodology

We use the initial theoretical framework of ecovillage characteristics as a starting point for developing the case study of Auroville. Here, we draw from academic literature published about Auroville during 1968–2021. We also draw inferences from self-published reports and documents by the Auroville Foundation. Although we cover multiple interconnected aspects of Auroville, the characteristics pertaining to an ecovillage remain the focus of our work. We review the literature sources deductively, drawing on aspects of values, governance, economics and self-reliance, established in the previous section.

We triangulate the secondary data sources against our ethnographic experience of having lived and worked in Auroville for extended periods of time (2010–2012 and 2013–2014, respectively). We have worked in Auroville as architects and urban planners. During this time, we participated in multiple meetings on Auroville’s development as part of our work. We have discussed aspects of Auroville’s sustainability with Aurovillians working on diverse aspects, from urban planning to regional integration. Furthermore, living and working in Auroville brought us in conversation with several individuals from villages surrounding Auroville, employed in Auroville. For writing this case study, we have revisited our lived experience of Auroville through memory, research and work diaries maintained during this period, photographs as well our previously published research articles (Venkitaraman 2017 ; Walsky and Joshi 2013 ). Given our expertise in architecture and planning, we have also presented the translation of the key characteristics of an ecovillage, namely, alternative values, governance and economic systems and self-reliance, in these domains.

We acknowledge certain limitations to our methodology. We rely largely on secondary data to expand upon the challenges and contradictions in an ecovillage. We have attempted to overcome this by drawing from our first-hand experience of having lived in Auroville. Although our lived experiences are almost a decade old, we have attempted to compliment it with recently published articles as well as newspaper reports.

The next section presents Auroville as an ecovillage followed by a critical examination of its regional impact, governance, and economic structure.

Auroville, an ecovillage in South India

Foundational values.

Sri Aurobindo was an Indian philosopher and spiritual leader who believed that “man is a transitional being” and developed the practice of integral yoga with the aim of evolving humans into divine beings (Sen 2018 ). His spiritual consort, Mirra Alfassa realized his ideas in material form through a “universal township” which would hopefully contribute to “progress of humanity towards its splendid future”. Auroville was founded in 1968 by Mirra Alfassa, as a township near Pondicherry, India. Alfassa envisioned Auroville to be a “site of material and spiritual research for a living embodiment of an actual human unity” (Alfassa 1968 ). On 28 February 1968, the city was inaugurated with the support of UNESCO and the participation of people from 125 countries who each brought a handful of earth from their homelands to an urn that stands at its centre as a symbolic representation of human unity, the aim of the project. This spiritual foundation has guided the development of the socio-economic structure of Auroville for individual and collective growth (Shinn 1984 ). To translate these spiritual ideas into a material form, Mirra Alfassa provided simple sketches, a Charter, and guiding principles towards human unity (Sarkar 2015 ).

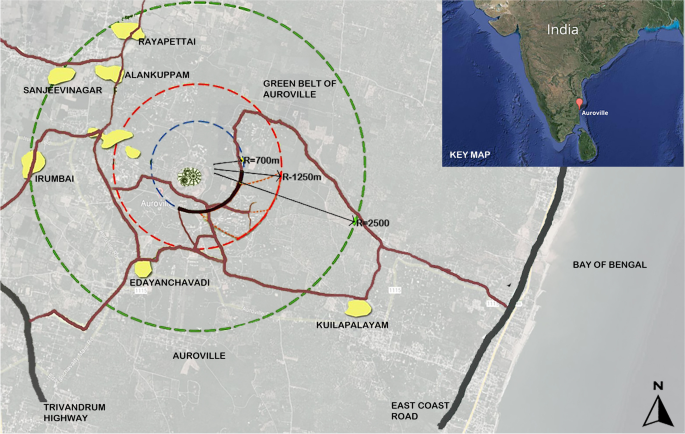

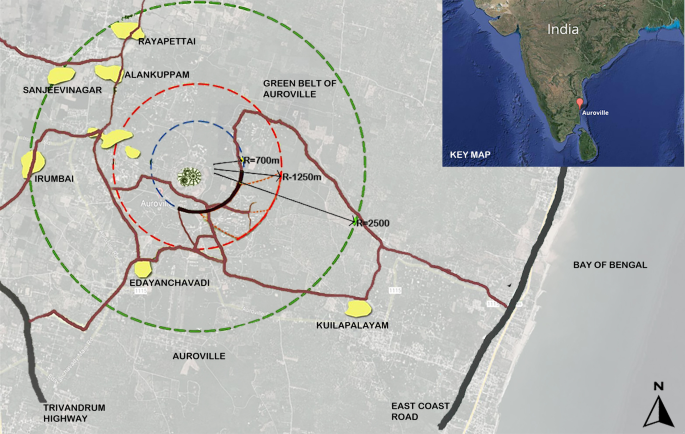

Roger Anger, a French architect translated Alfassa’s dream into the Auroville City Plan that continues to inform the physical development of Auroville (Kundoo 2009 ). The Auroville Masterplan 2025 envisions Auroville to be a circular township (Fig. 1 ) spread over a 20 sq. km (Auroville Foundation 2001 ). Initially planned for a population of 50,000 people, today Auroville today has 3305 residents hailing from 60 countries (Auroville Foundation 2021 ). Since its early days, there has been a divide between the “organicists” and the “constructionists” of Auroville (Kapur 2021 ). The organicists have a bottom-up vision of low impact and environmentally friendly development whereas the constructionists have a top-down vision of sticking with the original masterplan and realize an urban, dense version of Auroville.

A map of Auroville and its surrounding regions, with the main villages in the area

Auroville has served as a laboratory of low-cost and low-impact building construction, transportation, and city planning. Although the term sustainability has not been explicitly used in the Charter, it has been central to the city planning and building development process in Auroville (Walsky and Joshi 2013 ). Unlike many human settlements that negatively impact their ecology, the foundational project of Auroville was land restoration. The initial residents of Auroville were able to grow back parts of the Tropical Dry Evergreen Forest in and around Auroville using top-soil conservation and rainwater harvesting techniques (Blanchflower 2005 ). While the ecological restoration has been lauded both locally and globally, Namakkal ( 2012 ) argues that it is seldom acknowledged that the land was bought from local villagers at low prices and local labour was used to plant the forest as well as build the initial city. At the time of writing this paper, the Auroville Foundation still needs to secure 17% of the land in the city area and nearly 50% of the land for the green belt to realize the original masterplan. However, land prices have gone up substantially as have conflicts in acquiring this land for Auroville (Namakkal 2012 ).

Governance structure

While the Charter of Auroville says that “Auroville belongs to humanity as a whole” (Alfassa 1968 ), in reality, it is governed by a well-defined set of individuals. Auroville’s first few years, between 1968 and 1973, were guided directly by Mirra Alfassa. After her passing, there was a power struggle between the Sri Aurobindo Society, claiming control over the project, and the community members striving for autonomy (Kapur 2021 ).

The Government of India founded the Auroville Foundation Act in 1988 providing in the public interest, the acquisition of all assets and undertakings relatable to Auroville. These assets were ultimately vested in the Auroville Foundation which was formed in January 1991 (Auroville. 2015 ). The Auroville Foundation envisioned a notion of a planned future, resulting in a new masterplan in 1994. This masterplan encouraged participatory planning and recognized that the architectural vision needs to proceed in a democratic manner. This prompted the Auroville community to adopt a more structured form of governance. The Auroville Foundation has other governing institutions under it, namely: The Governing Board which has overall responsibility for Auroville’s development, The International Advisory Council, which advises the Governing Board on the management of the township and the Residents’ Assembly who organize activities relating to Auroville and formulate the master plan. Furthermore, there are committees and working groups for different aspects of development from waste management to building development.

Auroville is an example of the ‘bottom-up’ approach, in the sense that developments are decided and implemented by the community and the state level and national level governments get involved later (Sarkar 2015 ). An example of this is seen in the regular meetings held by the Town Development Council of Auroville which also conducted a weeklong workshop in 2019 for the community which covered themes such as place-making, dimensions of water and strategies for liveable cities and community planning (Ministry of Human Reource Development Government of India 2021 ).

Conflicts often arise between the interpretation of the initial masterplan and the present day realities and aspiration of the residents (Walsky and Joshi 2013 ). This is often rooted in the initial vision of Auroville as a city of 50,000 versus its current reality of being an ecovillage of around 3000 people. Spatially, this unusual growth pattern has been problematic in Auroville’s building and mobility planning (Venkitaraman 2017 ). At the time of writing this paper, there is a clash between the Residents’ Assembly and the Auroville Foundation over the felling of trees for the construction of the Crown Road project inside Auroville (The Hindu 2021 ). While the Residents’ Assembly wants a re-working of the original masterplan considering the ecological damage through tree cutting, the Auroville Foundation wants to move ahead with the original city vision.

Beyond its boundaries, Auroville is surrounded by numerous rural settlements, namely, Kuyilapalyam, Edayanchavadi, Alankuppam, Kottakarai, and Attankarai. The Auroville Village Action Group (AVAG) aims to help the village communities to strive towards sustainability and find plausible solutions to the problems of contemporary rural life. In September 1970, a charter was circulated among the sub-regional villages of Auroville, promising better employment opportunities and higher living standards with improved health and sanitation facilities (Social Research Centre Auroville 2005 ). Currently, there are about 13 groups for the development of the Auroville sub-region. However, Jukka ( 2006 ) points out that the regional development vision of Auroville is top-down and does not sufficiently engage with the villagers and their aspirations.

Auroville’s economic model

Auroville has also strived to move away from money as a foundation of society to a distinctive economic model exchange and sharing (Kapoor 2007 ). However, Auroville needs money to realize its multiple land and building projects. Auroville also receives various donations and grants. During 2018–2019, Auroville received around Rs. 2396 lakhs (around 4 million USD) under Foreign Contributions Regulation Act (FCRA) and other donations. The Central Government of India supports the Auroville Foundation with annual grants for Auroville’s management and for the running costs of the Secretariat of the Foundation, collectively known as Grant-in-Aid. Auroville received a total of Rs. 1463 lakhs (around 2 million USD) as Grant-in-Aid during 2018–2019. The income generated by Auroville during this time was Rs. 687 lakhs (around 91,000 USD) (Ministry of Human Reource Development Government of India 2021 ).

Presently, the economy of Auroville is based on manufacturing units and services with agriculture being an important sector, and currently, there are about 100 small and medium manufacturing units. The service sector of Auroville comprises of construction and architectural services and research and training in various sectors (Auroville Foundation 2001 ). In addition to this, tourism is another important source of income generation for Auroville. As per the Annual Report of Auroville Foundation, the donations and income have not been consistent over the years. In this regard, Auroville’s growth pattern in terms of the economy has not been linear and it does not mimic the usual growth patterns associated with the development of counterparts, in terms of capitalization, finance, governance, and on key issues such as distribution policies and ownership rights (Thomas and Thomas 2013 ).

Auroville also benefits from labour from the surrounding villages. The nature of employment provided in Auroville to villages remains largely in low-paying jobs (Namakkal 2012 ). It can be argued that the fruits of Auroville’s development have not been equally shared with the surrounding villages and a feeling of ‘us and them’ still pervades. Striving for human unity is the central tenet of Auroville (Shinn 1984 ), however, it has struggled to do so with its immediate neighbours.

Striving for self-sufficiency

Auroville has strived for self-sufficiency in terms of food production from local farms, energy production from renewable sources like solar and wind sources and waste management.

Many prominent buildings of Auroville have been designed keeping in mind the self-sufficiency principle in Auroville. For example, the Solar Kitchen was designed by architect Suhasini Ayer as a demonstration project to tap the solar energy potential of the region. At present, this building is used for cooking meals thrice a day for over 1000 people. The Solar Kitchen also supports the organic farming sector in Auroville by being the primary purchaser of the locally grown products (Ayer 1997 ). Another example is the Auroville Earth Institute, renowned for its Compressed and Stabilized Earth Block (CSEB) technique, which constitute natural and locally found soil as one of its main ingredients (Figs. 2 and 3 ).

Compressed earth blocks manufactured by Auroville Earth Institute

A residence in Auroville constructed using compressed earth blocks

However, it is important to acknowledge that Auroville does not exist as a 100% self-sufficient bubble. For example, food produced in Auroville provides for only 15% of the consumption (Auroville Foundation 2004 ). An initial attempt to calculate the ecological footprint of Auroville estimates it to be 2.5 Ha, against the average footprint of an Indian of 0.8 Ha (Greenberg 1998 ). Furthermore, though Auroville has strived for material innovation in architecture, it has not been successful in achieving 25 sq. metres as the limit to individual living space (Walsky and Joshi 2013 ). This challenges the notion of Auroville continuing to be an ecovillage if it aspires to be a city of 50,000 people and might end up having substantial ecological impact on its surroundings.

Urban sustainability transformation in a rapidly urbanizing world runs into the risk of focusing on technological fixes while overlooking the social and ecological impacts of growth. In this light, bottom-up initiatives like ecovillages serve as a laboratory for testing alternative and holistic models of development. Auroville, a 53-year-old ecovillage in southern India, has achieved this to a certain extent. Auroville is a showcase of land regeneration, biodiversity restoration, alternative building technologies as well as experimentations in alternative governance and economic models. In this paper, we have critically examined some achievements and challenges that Auroville has faced in realizing its initial vision of being a “city that the world needs” (Alfassa 1968 ). Lessons learnt from Auroville help deepen our understanding of ecovillages as sites of fostering alternative development practices. Here we discuss three aspects of this research:

Alternate lifestyles and values in the context of an ecovillage : Ecovillages are niches providing space for realizing alternative values and lifestyles. However, ecovillages seldom exist in a vacuum. They are physically situated in existing societies and economies. Although residents in an ecovillage seek to achieve collective identity by creating an alternative society, an ecovillage is embedded within a larger culture and thus, the prevailing ideologies of the dominant society affect the ecovillage (Ergas 2010 ) as seen in Auroville. This can be noticed between the material and knowledge flows in and out of Auroville. Furthermore, the India of the 1970s when Auroville was born with socialist values is very different from present-day India where material and capitalistic aspirations are on the rise. These are reflected in higher land prices and living costs in and around Auroville. Amidst the transforming political landscape of India in the 1970s, there were implications which were seen in the character of architectural production. Auroville welcomed and immersed itself into this era of experimentation. These developments form an integral part of the ethos of Auroville. To achieve its initial visions, Auroville depends on multiple external economic sources. In analysing ecovillages, it is important to critically examine the broader context within which they are located and how they influence and, in turn, are influenced by their contexts.

Even though Auroville’s architects and urban planners remain committed to their belief that architecture is a primary tool of community - building, decades later, the developments seem to have progressed at a slow pace. The number of permanently settled residents in Auroville has barely reached 2000 currently and the overall urban design remains fragmentary. Despite witnessing a slower rate of progress, it has been able to sustain a culture of innovation and Auroville remains utopian in its aim to create an alternative lifestyle (Scriver and Srivastava 2016 ).

Governance, economy, and self-sufficiency in an ecovillage that wants to be an eco-city : In growth-based societies, ecovillages present the possibility of providing an alternative vision of degrowth (Xue 2014 ). However, Auroville currently functions as an ecovillage that aspires to be an eco-city as per its initial masterplan. This growth-based model sometimes conflicts with Auroville’s vision of being a self-reliant, non-monetary society. Given the urgent need to remain within our planetary limits, ecovillages like Auroville could re-evaluate their initial growth-based visions and explore alternatives for achieving sustainability and well-being. The visions of ecovillages should thus not be set in stone, but rather remain flexible to evolving ideas and practices (Ergas 2010 ).

Similarly, governance structures might need a re-evaluation with changing priorities within the ecovillage as well as a need to be inclusive of regional visions and voices. It would be intriguing to explore on what kind of governance model/leadership is best suited to fulfil the aims of an ecovillage. Auroville seems to follow the elements of sustainability-oriented governance: empowerment, engagement, communication, openness and transparency (Bubna-Litic 2008 ), yet it is seen that conflicts arise. One solution to this could be greater external engagement with government and continuing to engage the external community about Auroville. Generally, intentional communities are organized by embracing the ideology of consensus, but it remains to be seen whether the consensus decision-making model works to its full potential in the context of alternative lifestyles. When individuals seek alternative lifestyles in the current world, there is a shift from globalized values towards local community autonomy, this shift demands a need for processes that allow for a different and more equitable approach to governance (Cunningham and Wearing 2013 ).

Ecovillages in the Global South : Situating ecovillages in the Global South requires a nuanced examination of the social, economic, and environmental aspects of sustainability that the ecovillage aims to achieve (Dias et al. 2017 ; Litfin 2009 ). In the case of Auroville, Auroville has helped bring back ecologically restorative practices in forestry, agriculture, and architecture in the region. However, the average Aurovillian has a higher standard of living than the neighbouring villagers. This in-turn influences the material consumption practices within the community. The lessons in sustainable living, in ecovillages located in the Global South, need not be unidirectional (from the ecovillage to the surrounding society). Rather, the ecovillage also stands to lean from the existing models of low-impact living.

Ecovillages in the Global South such as Auroville face similar problems related to Governance as seen in some other ecovillages in the developed world such as The Aldinga Arts Village in South Australia (Bubna-Litic 2008 ) and in Sweden (Bardici 2014 ). However, despite the issues related to consensus in Governance, the ecovillages are noted for their sustainable innovations.

Auroville’s sustainable measures have been endorsed by the Government of India as well. The Auroville Master Plan for 2000–2025 has been dedicated to creating an environmentally sustainable urban settlement which integrates the neighbourhood rural areas. The surrounding Green Belt, intended to be a fertile zone is presently being used for applied research in various sectors such as water management, food production, and soil conservation. The results promise a replicable model which could be used in urban and rural areas alike (Kapoor 2007 ).

To address the expansion and re-evaluation of the larger socio-economic context of Auroville and its socio-ecological impacts, as enunciated by Dias et al. ( 2017 ) and Kutting and Lipschutz (2009), a proposal for a sustainable regional plan was prepared in 2012 jointly by Government of India, ADEME (French Environment and Energy Management Agency), INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage) and PondyCAN (An NGO which works to preserve and enhance the natural, social, cultural and spiritual environment of Pondicherry). The report was prepared and aimed to be a way forward for unique and diverse communities to grow together as a single entity and to develop a holistic model for future development in this region. This report takes into consideration the surrounding villages and districts around Auroville: Puducherry, Viluppuram and Cuddalore (ADEME, INTACH, PondyCAN,, and Government of India 2012 ).

The concept of eco-cities in urban planning is defined as utopias, hard to achieve standards of human settlements. Ecovillages emerge as small-scale realization of the ideas of an eco-city. Over the years, the alternative practices of Auroville have served as an educational platform for researchers, students, and the civil society alike. However, realizing alternative ecological lifestyles, governance and economic system and self-sufficiency struggle with challenges and contradictions as the ecovillage interact with a larger growth-oriented capitalistic system. Although ecovillages are sites of experimentation, they are seldom insular space. Regional impacts of and on ecovillage are important in analysing their developmental trajectories. Finally, the vision of ecovillages needs to evolve as the ecovillage as well is surroundings grow and change. Experiments in ecovillages like Auroville remind us that alternative visions of human settlements come with opportunities and challenges and are a work-in-progress in achieving a more sustainable future. There is further potential to understand the consensus-based approach and the governance models in an ecovillage in a better manner.

It can be deduced from the findings that ecovillages as catalysts of urban sustainability have a lot of potentials and challenges. The potential is in terms of devising an alternate lifestyle based on an alternative style of governance while the challenges include the local ecological impact and the difficulty in consensus about certain things. There is a future possibility to explore other conditions which facilitate the mainstream translation of ecovillage practices and how future ecovillages can progress to the next level (Kim 2016 ; Norbeck 1999 ).

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

ADEME, INTACH, PondyCAN, & Government of India (2012) Sustainable Regional Planning Framework for Puducherry. Viluppuram, Auroville and Cuddalore

Google Scholar

Alfassa, M. (1968). The Auroville Charter: a new vision of power and promise for people choosing another way of life. https://auroville.org/contents/1

Alterman R, Harris D, Hill M (1984) The impact of public participation on planning: the case of the Derbyshire Structure Plan ( UK). Town Plann Rev 55 (2):177–196. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.55.2.f78767r1xu185563

Article Google Scholar

Anderson E (2015) Prologue. In: Lockyer J, Veteto JR (eds) Environmental Anthropology Engaging Ecotopia: Bioregionalism, Permaculture, and Ecovillages. Oxford, pp 1–18

Auroville Foundation. (2004). No Title.

Auroville Foundation. (2021). Auroville Census.

Auroville SRC (2005) Socio-economic survey of Auroville employees, p 2000

Auroville. (2015). Orgnaisational History and Involvement of Government of India. https://auroville.org/contents/850

Ayer S (1997) Auroville Design Consultants

Bardici VM (2014) A discourse analysis of Eco-city in the Swedish urban context - construction, cultural bias, selectivity, framing and political action, p 32

Barton, H. (2013). Sustainable Communities. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315870649

Bauhardt C (2014) Solutions to the crisis? The Green New Deal, Degrowth, and the Solidarity Economy: Alternatives to the capitalist growth economy from an ecofeminist economics perspective. Ecol Econ 102 :60–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.03.015

Blanchflower P (2005) Restoration of the Tropical Dry Evergreen Forest of Peninsular India. Biodiversity 6(1):17–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/14888386.2005.9712755

Boyer RHW (2015) Grassroots innovation for urban sustainability: comparing the diffusion pathways of three ecovillage projects. Environ Plann A Econ Space 47(2):320–337. https://doi.org/10.1068/a140250p

Bubna-Litic K (2008) The Aldinga Arts Ecovillage. Governance for Sustainability, pp 93–102

Campbell S (1996) Green Cities, Growing Cities, Just Cities?: Urban Planning and the Contradictions of Sustainable Development. J Am Plann Assoc 62 (3):296–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369608975696

Cunningham PA, Wearing SL (2013) The Politics of Consensus: An Exploration of the Cloughjordan Ecovillage, Ireland. Cosmopolitan Civil Soc 5:1–28 https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/27731

Dawson, J., & Lucas, C. (2006). Ecovillages: new frontiers for sustainability. Green Books.

Dias MA, Loureiro CFB, Chevitarese L, Souza CDME (2017) The meaning and relevance of ecovillages for the construction of sustainable soceital alternatives. Ambiente Sociedade 20(3):79–96. https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4422asoc0083v2032017

Edward G, Matthew E, K. (2010) The greenness of cities;Carbon dioxide emissions and urban development. J Urban Econ 67(3):404–418

Ergas C (2010) A model of sustainable living: Collective identity in an urban ecovillage. Organ Environ 23 (1):32–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026609360324

Fischer F (2017) Practicing Participatory Environmental Governance: Ecovillages and the Global Ecovillage Movement. In: Climate Crisis and the Democratic Prospect :Participatory Governance in Sustainable Communities, Oxford, pp 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199594917.001.0001

Foundation A (2001) The Auroville Universal Township Master Plan , Perspective, p 2025 https://www.auroville.info/ACUR/masterplan/index.htm

Gibson-Graham J (2008) Diverse Economies:performative practices for “other worlds.”. Progress Human Geography 32(5):613–632

Gilman, R. (1991). The Eco-Village Challenge. In Context. https://www.context.org/iclib/ic29/

Greenberg, D. (1998). Auroville’s Ecological Footprints. Geocommons.

Hall R (2015) The ecovillage experience as an evidence base for national wellbeing strategies. Intellect Econ 9 (1):30–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intele.2015.07.001

The Hindu. (2021). Auroville residents protest uprooting of trees for contentious Crown Project. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/auroville-residents-protest-uprooting-of-trees-for-contentious-crown-project/article37835625.ece#

Hopkins R (2008) The Transition Handbook From Oil Dependency to Local Resilience

IPCC (2014) Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. In: Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Joss S (2010a) Eco-cities: A global survey 2009. WIT Transact Ecol Environ 129:239–250. https://doi.org/10.2495/SC100211

Joss, Simon. (2010b). Eco-Cities — A Global Survey 2009 Part A : Eco-City Profiles. Governance & Sustainability: Innovating for Environmental & Technological Futures, May.

Jukka, J. (2006). Jukka Jouhki Imagining the Other Orientalism and Occidentalism in Tamil-European Relations in South India. In Building (Issue September).

Kapoor R (2007) Auroville: A spiritual-social experiment in human unity and evolution. Futures 39(5):632–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2006.10.009

Kapur, A. (2021). Better to Have Gone: Love, Death, and the Quest for Utopia in Auroville. Scribner Book Company.

Kim MY (2016) The Influences of an Eco-village towards Urban Sustainability: A case study of two Swedish eco-villages

Kirby A (2003) Redefining social and environmental relations at the ecovillage at Ithaca: A case study. J Environ Psycho 23 (3):323–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(03)00025-2

Kundoo A (2009) Roger Anger: research on beauty: architecture. Jovis, pp 1953–2008

Litfin K (2009) Reinventing the future: The global ecovillage movement as a holistic knowledge community. In: Kütting G, Lipschutz R (eds) Environmental Governance: Knowledge and Power in a Local-Global World. Routledge, pp 124–142. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203880104

Chapter Google Scholar

Lockyer J, Veteto JR (2013) Environmental Anthropology Engaging Ecotopia

Ministry of Human Reource Development Government of India. (2021). Auroville Foundation: Annual Report and Accounts(2018-19). https://aurovillefoundation.org.in/publications/annual-report/

Mössner S, Miller B (2015) Sustainability in One Place? Dilemmas of Sustainability Governance in the Freiburg Metropolitan Region. Regions Magazine 300(1):18–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13673882.2015.11668692

Namakkal J (2012) European Dreams, Tamil Land: Auroville and the Paradox of a Postcolonial Utopia. J Study Radicalism 6 (1):59–88. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsr.2012.0006

Norbeck, M. (1999). Individual Community Environment: Lessons from nine Swedish ecovillages. http://www.ekoby.org/index.html

Pickerill J (2017) What are we fighting for? Ideological posturing and anarchist geographies. Dial Human Geography 7 (3):251–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820617732914

Price OM, Ville S, Heffernan E, Gibbons B, Johnsson M (2020) Finding convergence: Economic perspectives and the economic practices of an Australian ecovillage. Environ Innov Soc Trans 34(April 2019):209–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.12.007

Register, R. (1987). Ecocity Berkeley : building cities for a healthy future. Berkeley, Calif. : North Atlantic Books, 1987. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/9910124360102121

Roelvink G, Gibson-Graham J (2009) A Postcaptialist politics of dwelling:ecological humanities and community economies in coversation. Austrailian Human Rev 46:145–158 http://australianhumanitiesreview.org/2009/05/01/a-postcapitalist-politics-of-dwelling-ecological-humanities-and-community-economies-in-conversation/

Roseland M (1997) Dimensions of the eco-city. Cities 14(4):197–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-2751(97)00003-6

Sarkar AN (2015) Eco-Innovations in Designing Ecocity, Ecotown and Aerotropolis. J Architect Eng Technol 05 (01):1–15. https://doi.org/10.4172/2168-9717.1000161

Article CAS Google Scholar

Scott AJ, Storper M (2015) The Nature of Cities: The Scope and Limits of Urban Theory. Int J Urban Regional Res 39(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12134

Scriver, P., & Srivastava, A. (2016). Building utopia: 50 years of Auroville. The Architectural Review. https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/building-utopia-50-years-of-auroville

Sen, P. K. (2018). Sri Aurobindo: His Life and Yoga 2nd Harper Collins Publishers India.

Shinn LD (1984) Auroville: Visionary Images and Social Consequences in a South Indian Utopian Community. Religious Stud 20 (2):239–253. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0034412500016024

Smith A (2011) The Transition Town Network: A Review of Current Evolutions and Renaissance. Social Movement Studies 10(1):99–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2011.545229

Snow DA, Soule SA, Kriesi H (2004) In: Snow DA, Soule SA, Kriesi H (eds) The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470999103

Thomas H, Thomas M (2013) Economics for People and Earth - The Auroville Case 1968-2008. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.33040.40967

United Nations. (1987). Our common future: report of the world commission on environment and development 0, 0. https://doi.org/10.1080/07488008808408783

Book Google Scholar

Van Bussel LGJ, De Haan N, Remme RP, Lof ME, De Groot R (2020) Community-based governance: Implications for ecosystem service supply in Berg en Dal, the Netherlands. Ecological Indicators 117(June):106510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106510

Venkitaraman, A. K. (2017). Addressing Resilience in Transportation in Futurustic Cities: A case of Auroville,Tamil Nadu, India. International Conference on Sustainable Built Environments , 2017. https://aurorepo.in/id/eprint/78/

Waerther S (2014) Sustainability in ecovillages – a reconceptualization. Int J Manage Applied Research 1(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.18646/2056.11.14-001

Wagner F (2012) Realizing Utopia: Ecovillage Endeavors and Academic Approaches. RCC Perspectives 8 :81–94 http://www.environmentandsociety.org/sites/default/files/ecovillage_research_review_0.pdf

Walsky T, Joshi N (2013) Realizing Utopia : Auroville’s Housing Challenges and the Cost of Sustainability. Abacus 8 (1):1–8 https://aurorepo.in/id/eprint/110/

Wolfram M. (2017). Grassroots Niches in Urban Contexts: Exploring Governance Innovations for Sustainable Development in Seoul. Proc Eng 198, 622–641 (Urban Transitions Conference, Shanghai, September 2016)

Xue J (2014) Is eco-village/urban village the future of a degrowth society? An urban planner’s perspective. Ecol Econ 105:130–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.06.003

Download references

Acknowledgements

Code availability.

Code availability is not applicable to this article as no codes were used during the current study.

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Graduate School of Global Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Yoshida-Honmachi, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto, 606-8501, Japan

Abhishek Koduvayur Venkitaraman

Leibniz-Institut für ökologische Raumentwicklung (www.ioer.de), Research Area Landscape, Ecosystems and Biodiversity, Weberplatz 1, 01217, Dresden, Germany

Neelakshi Joshi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Abhishek Koduvayur Venkitaraman .

Ethics declarations

Consent to participate.

Consent to participate is not applicable to this article as no participants were involved.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval is not applicable to this article since the study is based on secondary data.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Koduvayur Venkitaraman, A., Joshi, N. A critical examination of a community-led ecovillage initiative: a case of Auroville, India. Clim Action 1 , 15 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44168-022-00016-3

Download citation

Received : 29 December 2021

Accepted : 24 June 2022

Published : 08 July 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s44168-022-00016-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Global South

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

IRJET- Research Paper on Development of Ahirwadi Village as Smart Village

2021, IRJET

This Research paper deals with the study and development of village as a smart village. The community, individuals and collectively, will be empowered to take smart decisions using smart technologies, communication and innovation. Basic concept of smart village is to collect community efforts and strength of people from various streams and integrate it with information technology to provide benefits to the rural community. At the same time, a "Smart Village" will ensure good education, better infrastructure, proper sanitation facility, health facilities, waste management, renewable energy, environment protection, clean drinking water, resource use efficiency ,etc.

Related Papers

IRJET Journal

IJIRIS Journal Division

A ‘Smart Village’ will provide long-term social, economic, and environmental welfare activity for village community, which will enable and empower enhanced participation in local governance processes, promote entrepreneurship and build more resilient communities. At the same time, a ‘Smart Village’ will ensure proper sanitation facility, good education, better infrastructure, clean drinking water, health facilities, environment protection, resource use efficiency, waste management, renewable energy etc. There is an urgent need for designing and developing ‘Smart Village’, which are independent in providing the services and employment and yet well connected to the rest of the world. The Smart Village concept will be based on the local conditions, infrastructure, available resources in rural area and local demand as well as potential of export of good to urban areas. The present paper examine motivation behind the concept on ‘Smart Village’ is that the technology should acts as a catalyst for development, enabling education and local business opportunities, improving health and welfare, enhancing democratic engagement and overall enhancement of rural village dwellers. In the Indian context, villages are the heart of the nation. So we can achieve socio economic development of the Nation by enlarging the concept of smart villages on improving pattern

Human society is developing with rapid momentum and achieved various successes for making its livelihood better. The civilization is witness for various changes related to it’s the development through different catalysts like industrial development, green revaluation, science and technology, etc. The present era is augmented on Information and Communication Technology. This technology has proved its potential in various sectors of development in urban and rural landscapes. Urban areas are seems to more inclined to accept and adopt Information and Communication Technology due to advantages of literacy and better infrastructure as compared to rural areas. Due to such suitable situations of urban landscapes good amount of success of this technology is visible in the form of smart cities and better livelihood of residing human beings. But the problems, consequences and opportunities in urban areas are different for effective utilization of Information and Communication Technology for sustainable development of rural masses. The present research article discusses about rural development in developing world for the up-liftment of livelihood of the rural masses and to take a ‘look ahead’ at scientific developments and technologies that might be influential over the next 10 -20 years. The driving motivation behind the concept on “Smart Village” is that the technology should acts as a catalyst for development, enabling education and local business opportunities, improving health and welfare, enhancing democratic engagement and overall enhancement of rural village dwellers. The “Smart Village” concept aims to realize its goal through providing policymakers with insightful, bottom –up analyses of the challenges of village development

IJIRAE - International Journal of Innovative Research in Advanced Engineering , Surya Kadambari

Human society is progressing with fast urge and accumulated various successes for making its sustenance. The civilization gone through for various changes affiliated to its development through different accelerators like green revaluation, science and technology, industrial development etc. The present era is intensified on Information and Communication Technology. The increasing population of the world makes it necessary to alleviate the cities and villages to serve in a smart way. Hence, the idea of Smart cities came into being. Smart Villages are the need of the hour as development is needed for both rural and urban areas for improved livelihood. The impulsive motive behind the concept on “Smart Village " is that the technology .Now it's need of the hour is - integrated planning ,strategy, and above all monitoring and execution of the activities using proper governance models to work properly for the real future of emerging India. This paper has made an attempt to discuss the initiatives factors of the smart village and its implications. It focuses on the key areas as vision and need for smart villages, approaches, government programmes, technology used for smart villages ,areas of interest in smart village and it outcomes expected.

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Growth Evaluation

C.E Dr Sumanta Bhattacharya M.Tech,PhD,P.E,Ch.E

Smart rural development is one of the best criteria to achieve Sustainable Development, there are 60,000 villages in India, where the condition of some of the villages are extremely miserable with no access to water, food and employment. With advancement in technology and bringing in green technology India has made few of its villages developed and constructed them as smart village with 100 % energy security, water access, pucca house, internet connectivity, empowering women, installation of RO, better jobs and government schools which have introduced computer learning. With this smart village development it has reduced the migration rate and brough back the people who went to the urban sector in such of better standard of living and employment. Smart village is a private public partnership model. Smart rural village will help to eradicate poverty, hunger, educated everyone, smart villages have seen an up gradation in the number of students. With sustainable development and smart te...

“If the facilities available in the cities are not made available to rural population, the Governments will not have done their duties” Dr.A.P.J.AbdulKalam, Former President of India. Smart Villages is a community based initiativeofSamanvay.Com Welfare Society, primarily aimed to harness the benefits of information technology forth rural folks. The initiative is a community effort to mobilize the collective strengths of people from various streams and integrate it with information technology to provide benefits to the rural community. Gandhian Concept of Ideal Village- SWARAJ. Gandhi Ji said, my idea of Village Swaraj is that it is a complete republic, independent of its neighbors for its own vital wants, and yet interdependent for many others in which dependence is a necessity. Reconstruction of rural India on the basis of the concept of ideal village was Gandhian dream because it embodies great environmental ambiance needed for healthy human living. Theoretically, Gandhian approach to rural development maybe labeled as ‘idealist’. It attaches supreme importance to moral values and gives primacy to moral values over material conditions

Journal of emerging technologies and innovative research

Mohammedshakil S Malek

Smart Village Technology

Pragyan Nanda

IJSTE - International Journal of Science Technology and Engineering

This paper gives the idea from Smart cities to Smart villages. It focuses on the key areas of interest in the village perspective and also evaluates the applications of IoT in those areas. It also provides a comprehensive view with respect to improvement in the quality of life in villages. There is a need for designing and building Smart Villages which are independent in providing the service and employment and connected to the whole world. Smart villages will be connected to villages via information and communication technologies (ICT) used to access Internet. Smart Village program to improve public facilities in the villages seeks to make villages' smart' on the lines of Smart Cities that will help them become self-reliant, clean and up to date.

SHANLAX INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT

Vinayagamoorthi .G

A smart village knows about its citizens, offered resources, applicable services and schemes. It knows what it needs and when it needs. Smart village initiative focuses on superior resource-use efficiency, empowered local self-governance, access to assured basic amenities and responsible individual and community behavior to build a vibrant and happy society. The present research paper discusses about rural development in developing world for the up-liftman of livelihood of the rural masses. The driving motivation behind the concept on "Smart Village" is that the technology should acts as a means for development, enabling education and local business opportunities, improving health and welfare, enhancing democratic engagement and overall enhancement of rural village dwellers. Now it's need of the hour is-strategy, integrated planning and above all monitoring and execution of the activities using appropriate governance models the present era is increased on Information and Communication Technology.

RELATED PAPERS

Anna Ray-Jones

Frontiers in cellular neuroscience

Thomas Offner

Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance - Issues and Practice

Md Zabid Rashid

Agricultura Familiar: Pesquisa, Formação e Desenvolvimento

Rosana Quaresma Maneschy

Legislación y Política de Ciencia y Género

Carolina Olvera

Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing

Roger Skjetne

Jurnal Sylva Lestari

Arantha Sabilla

Spazi e immagini della fede, Cittadella

Severino Dianich

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health

Amanda Amos

Journal of Comparative Neurology

Monique Amey-Özel

Middle East Report

Bassel Salloukh

Future Business Journal

Anthony Promise

Biochemistry

Brazilian Journal of Development

Isabella Silveira

Pericles Zouhair

Endometrial cancer

Shilpa Kolhe

The Astronomical Journal

Jon Jenkins

Jurnal Kebijakan Sosial Ekonomi Kelautan dan Perikanan

Muhammad Rizky

Journal of emergency medicine case reports

Fikret Bildik

Physical review

Frank Tabakin

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin

Yoshihisa Kashima

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution

Chris Humphrey

Historia Caribe

Annals of Data Science

Mustapha Muhammad

Jurnal Teknologi Elektro

Endang Saputra

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Call For Papers 2023

- Online Submission

- Authors GuideLines

- Publication Charge

- Registration

- Certificate Request

- Thesis Publication

- Journal Indexing

- How to publish research paper

- Research Paper Topics

- Editorial Board

- Peer Review & Publication Policy

- Ethics Policy

- Editorial Scope

- 2024- List of Thesis

- Online Thesis Submission

- Thesis Publication Detail

- January 2024 Edition

- February 2024 Edition

- March 2024 Edition

- April 2024 Edition

- May 2024 Edition

- January 2023 Edition

- February 2023 Edition

- March 2023 Edition

- April 2023 Edition

- May 2023 Edition

- June 2023 Edition

- July 2023 Edition

- August 2023 Edition

- September 2023 Edition

- October 2023 Edition

- November 2023 Edition

- December 2023 Edition

- January 2022 Edition

- February 2022 Edition

- March 2022 Edition

- April 2022 Edition

- May 2022 Edition

- June 2022 Edition

- July 2022 Edition

- August 2022 Edition

- September 2022 Edition

- October 2022 Edition

- November 2022 Edition

- December 2022 Edition

- January 2020 Edition

- February 2020 Edition

- March 2020 Edition

- April 2020 Edition

- May 2020 Edition

- June 2020 Edition

- July 2020 Edition

- August 2020 Edition

- September 2020 Edition

- October 2020 Edition

- November 2020 Edition

- December 2020 Edition

- January 2019 Edition

- February 2019 Edition

- March 2019 Edition

- April 2019 Edition

- May 2019 Edition

- June 2019 Edition

- July 2019 Edition

- August 2019 Edition

- September 2019 Edition

- October 2019 Edition

- November 2019 Edition

- December 2019 Edition

- January 2018 Edition

- February 2018 Edition

- March 2018 Edition

- April 2018 Edition

- May 2018 Edition

- June 2018 Edition

- July 2018 Edition

- August 2018 Edition

- September 2018 Edition

- October 2018 Edition

- November 2018 Edition

- December 2018 Edition

- January 2017 Edition

- February 2017 Edition

- March 2017 Edition

- April 2017 Edition

- May 2017 Edition

- June 2017 Edition

- July 2017 Edition

- August 2017 Edition

- September 2017 Edition

- October 2017 Edition

- November 2017 Edition

- December 2017 Edition

- Archives- All Editions

- Registration Form

- Copyright Transfer

JOURNAL CALL FOR PAPER

- Call for Paper 2023

- Publication Indexing

AUTHORHS & EDITORS

- Author Guidelines

THESIS PUBLICATION

- Submit Your Thesis

- Published Thesis List

- Thesis Guidelines

CONFERENCE SPONSERSHIP

- Conference Papers

- Sponsorship Guidelines

PUBLICATIONS

- January 2016 Edition

- February 2016 Edition

- March 2016 Edition

- April 2016 Edition

- May 2016 Edition

- June 2016 Edition

- July 2016 Edition

- August 2016 Edition

When structural factors that cause interethnic violence work in favour of peace: The story of Baljvine, a warless Bosnian-Herzegovinian peace mosaic

- Original Article

- Published: 13 May 2024

Cite this article

- Faris Kočan 1 ,

- Janja Vuga Beršnak 1 &

- Rok Zupančič 1

Explore all metrics

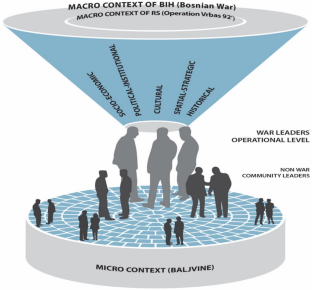

In this paper, we analyse the dynamics of interethnic relations in Baljvine, a village in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), where local Bosniaks and Serbs did not resort to interethnic violence that otherwise marked most of BiH during the last war. Drawing on structural factors that shed light on the dynamics of relations in post-conflict societies where interethnic violence occurred, the aim is to explain why and how bloodshed was prevented in Baljvine during the last war. To achieve this, we employ a multi-method research approach, combining qualitative observation with participation and interviews with the villagers. The results show that intersubjective motivations and a set of smaller coincidences in Baljvine affected structural factors and resulted in avoidance of interethnic violence. This enabled us to coin the concept of “peace mosaic” to demonstrate how several smaller pieces have to align in a community to allow it to remain peaceful. The key contribution is in advancing the argument that the structural factors that explain interethnic violence can also work in favour of peace.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

A contemporary instance of such a trajectory can be illustrated by the case of the Russian Federation’s full-scale aggression against Ukraine. This event not only captured the attention of IR scholars, as highlighted by Burlyuk and Musliu ( 2023 ), but also spurred an extraordinary surge in military budgets worldwide. The latter was further underscored by the 2023 report issued by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), which showed that world military expenditure rose by 3.7% in real terms in 2022, to reach a record high of 2240 billion USD.

Republika Srpska is one of the two (semi-) autonomous entities in BiH, populated mostly by Bosnian Serbs.

Armakolas (2012), focusing on wartime city of Tuzla, showed how new political structures, legacies of the past, pre-existing institutions, networds and creative policymaking were used for both fostering and defusing the conflict.

Moore ( 2013 ), focusing on post-war Mostar and Brčko, highlighted how the design of political institutions, the sequencing of political and economic reforms, local and regional legacies from the war, and the practice and organization of international peacebuilding efforts, overcome divisions that continue to stymie the postwar peace process in BiH.

While Saulich and Werthes ( 2018 ) define such places as non-war communities, Kaldor ( 1999 ) calls them ”islands of civility”. Autesserre ( 2014 ), for example, coined such places as ”peace islands” or ”islands of peace”. Stemming from this, we define Baljvine as ”village of peace”.

In 2003, the archaeological site of 'stećci' (monumental tombstones) in Baljvine – dating back to medieval times – was designated as a national monument of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Commission to Preserve National Monument, 2003).

In September 2022, we talked to Prof. Dr. Husnija Kamberović and Assoc. Prof. Dr. Max Bergholz in order to obtain relevant literature on happenings in Bosanska Krajina region during WWII. Based on their recommendations, we contacted Mr. Dino Dupanović, a local archivist at the Museum of Una-Sana Canton in Bihać, and Mr. Vladan Vukliš, assistant director of the Arhiv Republike Srpske in Banja Luka. Wealso talked to David Humar, brigadier of the Slovenian Armed Forces, with whom we discussed the doctrine and operational level of the Yugoslav People’s Army, based on which the Army of RS functioned during the Bosnian war.

In April 2022, we conducted interviews with three (older) inhabitants of Baljvine who lived in the village during the Bosnian war. One of them was also a member of the 'interethnic commission', which outlined everyday life in Baljvine amidst the presence of the Republika Srpska army in the village.

In December 2022 and January 2023, we exchanged several e-mails, held three telephone conversations and conducted two interviews with local officers of the Army of Republika Srpska and the commanding police officer for the Mrkonjić Grad and its surroundings. These individuals were all engaged with everyday dynamics in Baljvine in 1992 in the crucial period when the threat of bloodshed loomed large.

Today known as Kneževo.

Ustasha, a nationalistic and racist movement responsible also for the assassination of the Yugoslav king Alexander in 1934, were founded by Ante Pavelić. At the outbreak of WWII and the collapse of the Yugoslav regime in 1941, he became the leader of a fascist puppet state known as the Independent State of Croatia. The ideology of the movement was a blend of fascism, Roman Catholicism and Croatian ultranationalism and based on hatred against Serbs, Jews and Roma.

In 1992, the ethnically-mixed area around Jajce was occupied by the military offensive undertaken by the Army of RS in the period between June–October 1992; Jajce was of strategic importance for broader security of the Banja Luka region.

As stated by an officer of the Army of RS, they first came to the village in June 1992 (after the start of Operation Vrbas '92) when they heard gunfire around the village and saw that the situation in the village was worsening – particularly because of the individuals from surrounding villages that sporadically came to Baljvine and tried to instill fear among the villagers with an aim to sell arms. After the intervention of the Army of RS officer and police commander of Mrkonjić Grad in June 1992, the village was considered 'safe'.

Operation Southern Move was the final Croatian Army (HV) and HVO offensive of the Bosnian war. It began in Croatia and continued into Bosnia-Herzegovina. The offensive displaced 10.000 Bosnian Serb refugees from Mrkonjić Grad.

He mentioned the so-called ”Arkan's Tigers”, which were responsible for numerous war crimes and massacres. They operated, among other, also in Mrkonjić Grad.

Most of them returned a year or two after the Dayton Peace Agreement was signed, meaning that the looting may also have happened at the hands of neighbouring villagers after the end of the war.

The author used the following cases: the Semai (Malaya), Siriono (Bolivia), Kung Bushment (Kalahari desert), Mbuti Pygmies (equatorial Africa), Copper Eskimo (Canada), Hutterities (North America) and the Islanders of Tristan da Cunha (South Pacific).

It was comprised of four individuals (two Bosniaks from Lower Baljvine and two Serbs from Upper Baljvine).

And vice versa, as the now employed villagers buy goods from the local shop, providing the owner with means to survive even if they could get the goods in other (bigger) shop for cheaper.

Dost – translated as a friend – is one of many Turkish words in contemporary language in BiH that describes a strong friendship extending beyond casual everyday interactions greetings.

Abazović, Dino (2014) ‘Reconciliation, Ethnopolitics and Religion in Bosnia-Herzegovina’ in Dino Abazović and Mitja Velikonja, eds., Post-Yugoslavia: New Cultural and Political Perspectives, 35–56, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ackermann, Alice (2003) ‘The Idea and Practice of Conflict Prevention’, Journal of Peace Research 40(3): 339–47.

Article Google Scholar

Anderson, M. B. and M. Wallace (2013) ‘Opting Out of War: Strategies to Prevent Violent Conflict’, Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Google Scholar

Arriola, Leonardo R. and David A. Dow (2021) ‘Policing Institutions and Post-Conflict Peace’, Journal of Conflict Resolution 65(10): 1738–63.

Armakolas, Ioannis (2011) ‘The ‘Paradox’ of Tuzla City: Explaining Non-nationalist Local Politics during the Bosnian War’, Europe-Asia Studies 63(2): 229-61.

Arnautović, Marija (2010) ‘Baljvine: Selo u kojem nikada nije trijumfovala mržnja’, Institute for War & Peace Reporting, 10 April, available at https://iwpr.net/sr/global-voices/baljvine-selo-u-kojem-nikada-nije-trijumfovala-mrznja (5 October, 2023).

Autesserre, Séverine (2014) Peaceland: Conflict Resolution and the Everyday Politics of International Intervention, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Balkan Insight (2015), The Bosnian Village that Rejected the War, available at https://balkaninsight.com/2015/11/16/baljvine-village-where-there-was-no-war-11-15-2015/ (5 September 2023).

Banović, Damir, Gavrić, Saša and Maria Mariño Barreiro (2021) The Political System of Bosnia and Herzegovina: Institutions, Actors and Processes, Cham: Springer.

Basta, Karlo (2016) ‘Imagined Institutions: The Symbolic Power of Formal Rules in Bosnia and Herzegovina’, Slavic Review 75(4): 944–69.

Becker, Matthew T. (2022) ‘An Ethnic Security Dilemma in Bosnia-Herzegovina: Civic Pride and Civics Education’, Nationalities Papers 51(6): 1235–49.

Belloni, Roberto and Jasmin Ramović (2020) ‘Elite and Everyday Social Contracts in Bosnia and Herzegovina: Pathways to Forging a National Social Contract?’, Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 14(1): 42–63.

Bergholz, Max (2019) ‘To Kill or Not to Kill? The Challenge of Restraining Violence in a Balkan Community’, Comparative Studies in Society and History 61(4): 954–85.

Björkdahl, Annika. (2018) ‘Republika Srpska: Imaginary, performance and spatialization’, Political Geography 66: 34–43.

Brennan, Seán and Branka Marijan (2023) ‘Contested Spaces and Everyday Peace Politics in Northern Ireland’, Journal of Ethnic Studies 90(1), 97–110.

Brewer, John D. (2010) Peace Processes. A Sociological Approach, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Burlyuk, Olga and Vjosa Musliu (2023) ‘The responsibility to remain silent? On the politics of knowledge production and (self-)reflection in Russia’s war against Ukraine’, Journal of International Relations and Development 26: 605–18.

Carabelli, Giulia, Djurasovic, Aleksandra and Renata Summa (2019) ‘Challenging the representation of ethnically divided cities: perspectives from Mostar’, Space and Polity 23(2): 116–24.

Demarest, Leila and Roos Haer (2021) ‘A perfect match? The dampening effect of interethnic marriage on armed conflict in Africa’, Conflict Management and Peace Science 39(6): 686–705.

Diehl, Paul F. (2016) ‘Exploring Peace: Looking Beyond War and Negative Peace’, International Studies Quarterly 60(1): 1–10.

Djordjević, Angela and Rok Zupančič (2024) ‘Undivided’ city in a divided society: explaining the peaceful coexistence of Albanians and Serbs in Kamenicë/Kamenica, Kosovo’, Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 0(0): 1–19.

Đondović, Radomir (1989) Sanitetska služba u narodnooslobodilačkom ratu Jugoslavije 1941–1945, Beograd: Vojnoizdavački i novinarski centar.

Dragojević, Mila (2019) Amoral Communities: Collective Crimes in Times of War, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Dunbar, Robin I. M. and Richard Sosis (2018) ‘Optimising human community sizes’, Evolution and human behavior: Official journal of the Human Behaviour Society 39(1): 106–11.

Fabbro, David (1978) ‘Peaceful Societies: An Introduction’, Journal of Peace Research 15(1): 67–83.

Galtung, Johan (1969) ‘Violence, Peace, and Peace Research’, Journal of Peace Research 6(3): 167–91.

Galtung, Johan (1996) ‘Peace by peaceful means: Peace and conflict, development and civilization’, Oslo: Sage Publications.

Golubović, Jelena (2019) ‘”To me, you are not a Serb”: Ethnicity, ambiguity, and anxiety in post-war Sarajevo’, Ethnicities 20(3): 1–20.

Hancock, Liam and Christopher Mitchell, eds. (2007) Zones of Peace, London: Kumarian Press.

Hoare, Marko Atilla (2002) ‘Whose is the partisan movement? Serbs, Croats and the legacy of a shared resistance’, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 15(4): 24–41.

Hoare, Marko Atilla (2006) Genocide and Resistance in Hitler’s Bosnia: The Partisans and the Chetniks, 1941–1943, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Idler, Anette, Belén Garrido, Maria and Cécile Mouly (2015) ‘Peace Territories in Colombia: Comparing Civil Resistance in Two War-Torn Communities’, Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 10(3): 1–15.

Institute for Economics and Peace (2016) Global Peace Index: Ten Years of Measuring Peace, New York: IEP.

Jelinčić, Daniela Angelina and Sandro Knezović (2021) ‘Cross-border Cultural Relations of Croatia and Serbia: Milk and Honey if Money is Involved’ 16(1): 1–29.

Kaldor, Mary (1999) New and Old Wars: Organized Violence in a Global Era, Cambridge: Polity.

Kalyvas, Stathis N. (2006) The Logic of Violence in Civil Wars, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Katunarić, Vjeran (2010) ‘The Elements of Culture of Peace in some Multiethnic Communities in Croatia’, Journal of Conflictology 1(2): 1–13.

Kemp, Graham and Fry, Douglas. P. (2004) Keeping the Peace: Conflict Resolution and Peaceful Societies Around the World, London: Routledge.

Kočan, Faris and Rok Zupančič, (2023) ‘Capturing post-conflict anxieties: Towards an Analytical Framework’, Peacebuilding 12(1): 120–38.

Lovrenović, Dubravko (2016) ‘Bosnia and Herzegovina as the Stage of Three Parallel and Conflicted Historical Memories’, European Review 24(4):481–90.

Lund, Michael (2002) ‘Preventing Violent Intrastate Conflicts: Learning Lessons from Experience’ in P. Van Tongeren, H. von Van de Veen and J. Verhoeven, eds., Searching for Peace in Europe and Eurasia, 99–123, Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Mac Ginty, Roger (2014) ‘Everyday Peace: Bottom-up and Local Agency in Conflict-Affected Societies’, Security Dialogue 45: 548–64.

Maglajic, Reima Ana, Vejzagić, Halida, Palata, Jasmin and China Mills (2022) ‘‘Madness’ after the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina – challenging dominant understandings of distress’, Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine 28(2): 216–34.

Mitchell, Christopher R. and Catalina Rojas (2012) ‘Against the Stream: Colombian zones of peace under democratic security’ in Christopher. R. Mitchell and Landon E. Hancock, eds., Local Peacebuilding and National Peace: Interaction Between Grassroots and Elite Processes, 39–67, London and New York: Continuum.

Moore, Adam (2013) Peacebuilding in Practice: Local Experience in Two Bosnian Towns, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Morrow, Duncan (2023) ‘Transformation of Truce? Tracing the Decline of ”Reconciliation” and Its Consequences for Northern Ireland Since 1998’, Journal of Ethnic Studies 90(9): 45–61.

Mouly, Cécile, Idler, Annette and Belén Garrido (2015) ‘Zones of Peace in Colombia’s Borderland’, International Journal of Peace Studies 20(1): 51–63.