Brainstorming

What this handout is about.

This handout discusses techniques that will help you start writing a paper and continue writing through the challenges of the revising process. Brainstorming can help you choose a topic, develop an approach to a topic, or deepen your understanding of the topic’s potential.

Introduction

If you consciously take advantage of your natural thinking processes by gathering your brain’s energies into a “storm,” you can transform these energies into written words or diagrams that will lead to lively, vibrant writing. Below you will find a brief discussion of what brainstorming is, why you might brainstorm, and suggestions for how you might brainstorm.

Whether you are starting with too much information or not enough, brainstorming can help you to put a new writing task in motion or revive a project that hasn’t reached completion. Let’s take a look at each case:

When you’ve got nothing: You might need a storm to approach when you feel “blank” about the topic, devoid of inspiration, full of anxiety about the topic, or just too tired to craft an orderly outline. In this case, brainstorming stirs up the dust, whips some air into our stilled pools of thought, and gets the breeze of inspiration moving again.

When you’ve got too much: There are times when you have too much chaos in your brain and need to bring in some conscious order. In this case, brainstorming forces the mental chaos and random thoughts to rain out onto the page, giving you some concrete words or schemas that you can then arrange according to their logical relations.

Brainstorming techniques

What follows are great ideas on how to brainstorm—ideas from professional writers, novice writers, people who would rather avoid writing, and people who spend a lot of time brainstorming about…well, how to brainstorm.

Try out several of these options and challenge yourself to vary the techniques you rely on; some techniques might suit a particular writer, academic discipline, or assignment better than others. If the technique you try first doesn’t seem to help you, move right along and try some others.

Freewriting

When you freewrite, you let your thoughts flow as they will, putting pen to paper and writing down whatever comes into your mind. You don’t judge the quality of what you write and you don’t worry about style or any surface-level issues, like spelling, grammar, or punctuation. If you can’t think of what to say, you write that down—really. The advantage of this technique is that you free up your internal critic and allow yourself to write things you might not write if you were being too self-conscious.

When you freewrite you can set a time limit (“I’ll write for 15 minutes!”) and even use a kitchen timer or alarm clock or you can set a space limit (“I’ll write until I fill four full notebook pages, no matter what tries to interrupt me!”) and just write until you reach that goal. You might do this on the computer or on paper, and you can even try it with your eyes shut or the monitor off, which encourages speed and freedom of thought.

The crucial point is that you keep on writing even if you believe you are saying nothing. Word must follow word, no matter the relevance. Your freewriting might even look like this:

“This paper is supposed to be on the politics of tobacco production but even though I went to all the lectures and read the book I can’t think of what to say and I’ve felt this way for four minutes now and I have 11 minutes left and I wonder if I’ll keep thinking nothing during every minute but I’m not sure if it matters that I am babbling and I don’t know what else to say about this topic and it is rainy today and I never noticed the number of cracks in that wall before and those cracks remind me of the walls in my grandfather’s study and he smoked and he farmed and I wonder why he didn’t farm tobacco…”

When you’re done with your set number of minutes or have reached your page goal, read back over the text. Yes, there will be a lot of filler and unusable thoughts but there also will be little gems, discoveries, and insights. When you find these gems, highlight them or cut and paste them into your draft or onto an “ideas” sheet so you can use them in your paper. Even if you don’t find any diamonds in there, you will have either quieted some of the noisy chaos or greased the writing gears so that you can now face the assigned paper topic.

Break down the topic into levels

Once you have a course assignment in front of you, you might brainstorm:

- the general topic, like “The relationship between tropical fruits and colonial powers”

- a specific subtopic or required question, like “How did the availability of multiple tropical fruits influence competition amongst colonial powers trading from the larger Caribbean islands during the 19th century?”

- a single term or phrase that you sense you’re overusing in the paper. For example: If you see that you’ve written “increased the competition” about a dozen times in your “tropical fruits” paper, you could brainstorm variations on the phrase itself or on each of the main terms: “increased” and “competition.”

Listing/bulleting

In this technique you jot down lists of words or phrases under a particular topic. You can base your list on:

- the general topic

- one or more words from your particular thesis claim

- a word or idea that is the complete opposite of your original word or idea.

For example, if your general assignment is to write about the changes in inventions over time, and your specific thesis claims that “the 20th century presented a large number of inventions to advance US society by improving upon the status of 19th-century society,” you could brainstorm two different lists to ensure you are covering the topic thoroughly and that your thesis will be easy to prove.

The first list might be based on your thesis; you would jot down as many 20th-century inventions as you could, as long as you know of their positive effects on society. The second list might be based on the opposite claim, and you would instead jot down inventions that you associate with a decline in that society’s quality. You could do the same two lists for 19th-century inventions and then compare the evidence from all four lists.

Using multiple lists will help you to gather more perspective on the topic and ensure that, sure enough, your thesis is solid as a rock, or, …uh oh, your thesis is full of holes and you’d better alter your claim to one you can prove.

3 perspectives

Looking at something from different perspectives helps you see it more completely—or at least in a completely different way, sort of like laying on the floor makes your desk look very different to you. To use this strategy, answer the questions for each of the three perspectives, then look for interesting relationships or mismatches you can explore:

- Describe it: Describe your subject in detail. What is your topic? What are its components? What are its interesting and distinguishing features? What are its puzzles? Distinguish your subject from those that are similar to it. How is your subject unlike others?

- Trace it: What is the history of your subject? How has it changed over time? Why? What are the significant events that have influenced your subject?

- Map it: What is your subject related to? What is it influenced by? How? What does it influence? How? Who has a stake in your topic? Why? What fields do you draw on for the study of your subject? Why? How has your subject been approached by others? How is their work related to yours?

Cubing enables you to consider your topic from six different directions; just as a cube is six-sided, your cubing brainstorming will result in six “sides” or approaches to the topic. Take a sheet of paper, consider your topic, and respond to these six commands:

- Describe it.

- Compare it.

- Associate it.

- Analyze it.

- Argue for and against it.

Look over what you’ve written. Do any of the responses suggest anything new about your topic? What interactions do you notice among the “sides”? That is, do you see patterns repeating, or a theme emerging that you could use to approach the topic or draft a thesis? Does one side seem particularly fruitful in getting your brain moving? Could that one side help you draft your thesis statement? Use this technique in a way that serves your topic. It should, at least, give you a broader awareness of the topic’s complexities, if not a sharper focus on what you will do with it.

In this technique, complete the following sentence:

____________________ is/was/are/were like _____________________.

In the first blank put one of the terms or concepts your paper centers on. Then try to brainstorm as many answers as possible for the second blank, writing them down as you come up with them.

After you have produced a list of options, look over your ideas. What kinds of ideas come forward? What patterns or associations do you find?

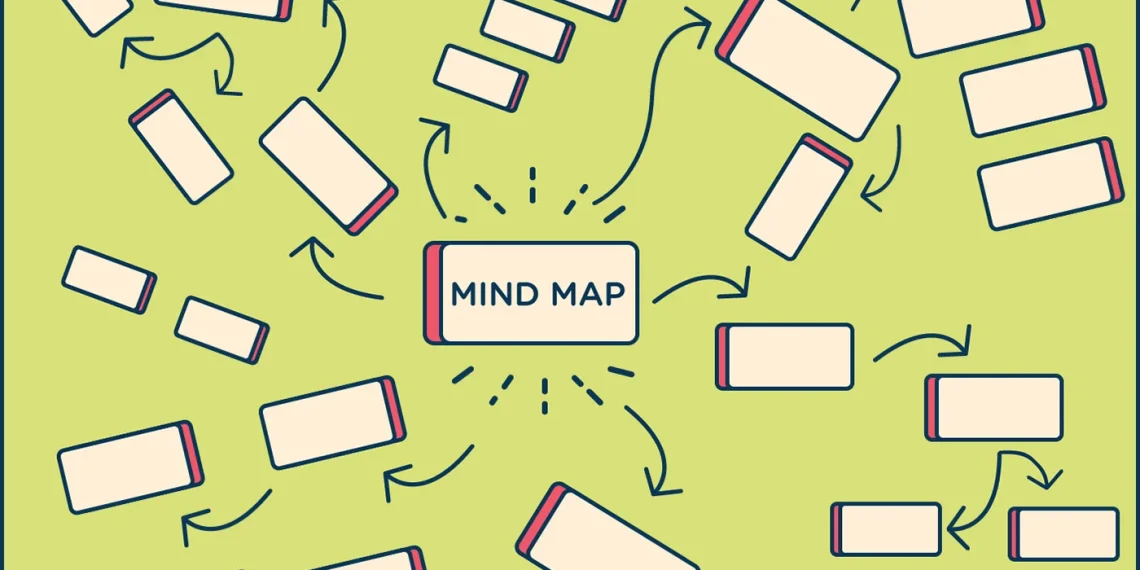

Clustering/mapping/webbing:

The general idea:

This technique has three (or more) different names, according to how you describe the activity itself or what the end product looks like. In short, you will write a lot of different terms and phrases onto a sheet of paper in a random fashion and later go back to link the words together into a sort of “map” or “web” that forms groups from the separate parts. Allow yourself to start with chaos. After the chaos subsides, you will be able to create some order out of it.

To really let yourself go in this brainstorming technique, use a large piece of paper or tape two pieces together. You could also use a blackboard if you are working with a group of people. This big vertical space allows all members room to “storm” at the same time, but you might have to copy down the results onto paper later. If you don’t have big paper at the moment, don’t worry. You can do this on an 8 ½ by 11 as well. Watch our short videos on webbing , drawing relationships , and color coding for demonstrations.

How to do it:

- Take your sheet(s) of paper and write your main topic in the center, using a word or two or three.

- Moving out from the center and filling in the open space any way you are driven to fill it, start to write down, fast, as many related concepts or terms as you can associate with the central topic. Jot them quickly, move into another space, jot some more down, move to another blank, and just keep moving around and jotting. If you run out of similar concepts, jot down opposites, jot down things that are only slightly related, or jot down your grandpa’s name, but try to keep moving and associating. Don’t worry about the (lack of) sense of what you write, for you can chose to keep or toss out these ideas when the activity is over.

- Once the storm has subsided and you are faced with a hail of terms and phrases, you can start to cluster. Circle terms that seem related and then draw a line connecting the circles. Find some more and circle them and draw more lines to connect them with what you think is closely related. When you run out of terms that associate, start with another term. Look for concepts and terms that might relate to that term. Circle them and then link them with a connecting line. Continue this process until you have found all the associated terms. Some of the terms might end up uncircled, but these “loners” can also be useful to you. (Note: You can use different colored pens/pencils/chalk for this part, if you like. If that’s not possible, try to vary the kind of line you use to encircle the topics; use a wavy line, a straight line, a dashed line, a dotted line, a zigzaggy line, etc. in order to see what goes with what.)

- There! When you stand back and survey your work, you should see a set of clusters, or a big web, or a sort of map: hence the names for this activity. At this point you can start to form conclusions about how to approach your topic. There are about as many possible results to this activity as there are stars in the night sky, so what you do from here will depend on your particular results. Let’s take an example or two in order to illustrate how you might form some logical relationships between the clusters and loners you’ve decided to keep. At the end of the day, what you do with the particular “map” or “cluster set” or “web” that you produce depends on what you need. What does this map or web tell you to do? Explore an option or two and get your draft going!

Relationship between the parts

In this technique, begin by writing the following pairs of terms on opposite margins of one sheet of paper:

Looking over these four groups of pairs, start to fill in your ideas below each heading. Keep going down through as many levels as you can. Now, look at the various parts that comprise the parts of your whole concept. What sorts of conclusions can you draw according to the patterns, or lack of patterns, that you see? For a related strategy, watch our short video on drawing relationships .

Journalistic questions

In this technique you would use the “big six” questions that journalists rely on to thoroughly research a story. The six are: Who?, What?, When?, Where?, Why?, and How?. Write each question word on a sheet of paper, leaving space between them. Then, write out some sentences or phrases in answer, as they fit your particular topic. You might also record yourself or use speech-to-text if you’d rather talk out your ideas.

Now look over your batch of responses. Do you see that you have more to say about one or two of the questions? Or, are your answers for each question pretty well balanced in depth and content? Was there one question that you had absolutely no answer for? How might this awareness help you to decide how to frame your thesis claim or to organize your paper? Or, how might it reveal what you must work on further, doing library research or interviews or further note-taking?

For example, if your answers reveal that you know a lot more about “where” and “why” something happened than you know about “what” and “when,” how could you use this lack of balance to direct your research or to shape your paper? How might you organize your paper so that it emphasizes the known versus the unknown aspects of evidence in the field of study? What else might you do with your results?

Thinking outside the box

Even when you are writing within a particular academic discipline, you can take advantage of your semesters of experience in other courses from other departments. Let’s say you are writing a paper for an English course. You could ask yourself, “Hmmm, if I were writing about this very same topic in a biology course or using this term in a history course, how might I see or understand it differently? Are there varying definitions for this concept within, say, philosophy or physics, that might encourage me to think about this term from a new, richer point of view?”

For example, when discussing “culture” in your English, communications, or cultural studies course, you could incorporate the definition of “culture” that is frequently used in the biological sciences. Remember those little Petri dishes from your lab experiments in high school? Those dishes are used to “culture” substances for bacterial growth and analysis, right? How might it help you write your paper if you thought of “culture” as a medium upon which certain things will grow, will develop in new ways or will even flourish beyond expectations, but upon which the growth of other things might be retarded, significantly altered, or stopped altogether?

Using charts or shapes

If you are more visually inclined, you might create charts, graphs, or tables in lieu of word lists or phrases as you try to shape or explore an idea. You could use the same phrases or words that are central to your topic and try different ways to arrange them spatially, say in a graph, on a grid, or in a table or chart. You might even try the trusty old flow chart. The important thing here is to get out of the realm of words alone and see how different spatial representations might help you see the relationships among your ideas. If you can’t imagine the shape of a chart at first, just put down the words on the page and then draw lines between or around them. Or think of a shape. Do your ideas most easily form a triangle? square? umbrella? Can you put some ideas in parallel formation? In a line?

Consider purpose and audience

Think about the parts of communication involved in any writing or speaking act: purpose and audience.

What is your purpose?

What are you trying to do? What verb captures your intent? Are you trying to inform? Convince? Describe? Each purpose will lead you to a different set of information and help you shape material to include and exclude in a draft. Write about why you are writing this draft in this form. For more tips on figuring out the purpose of your assignment, see our handout on understanding assignments .

Who is your audience?

Who are you communicating with beyond the grader? What does that audience need to know? What do they already know? What information does that audience need first, second, third? Write about who you are writing to and what they need. For more on audience, see our handout on audience .

Dictionaries, thesauruses, encyclopedias

When all else fails…this is a tried and true method, loved for centuries by writers of all stripe. Visit the library reference areas or stop by the Writing Center to browse various dictionaries, thesauruses (or other guide books and reference texts), encyclopedias or surf their online counterparts. Sometimes these basic steps are the best ones. It is almost guaranteed that you’ll learn several things you did not know.

If you’re looking at a hard copy reference, turn to your most important terms and see what sort of variety you find in the definitions. The obscure or archaic definition might help you to appreciate the term’s breadth or realize how much its meaning has changed as the language changed. Could that realization be built into your paper somehow?

If you go to online sources, use their own search functions to find your key terms and see what suggestions they offer. For example, if you plug “good” into a thesaurus search, you will be given 14 different entries. Whew! If you were analyzing the film Good Will Hunting, imagine how you could enrich your paper by addressed the six or seven ways that “good” could be interpreted according to how the scenes, lighting, editing, music, etc., emphasized various aspects of “good.”

An encyclopedia is sometimes a valuable resource if you need to clarify facts, get quick background, or get a broader context for an event or item. If you are stuck because you have a vague sense of a seemingly important issue, do a quick check with this reference and you may be able to move forward with your ideas.

Armed with a full quiver of brainstorming techniques and facing sheets of jotted ideas, bulleted subtopics, or spidery webs relating to your paper, what do you do now?

Take the next step and start to write your first draft, or fill in those gaps you’ve been brainstorming about to complete your “almost ready” paper. If you’re a fan of outlining, prepare one that incorporates as much of your brainstorming data as seems logical to you. If you’re not a fan, don’t make one. Instead, start to write out some larger chunks (large groups of sentences or full paragraphs) to expand upon your smaller clusters and phrases. Keep building from there into larger sections of your paper. You don’t have to start at the beginning of the draft. Start writing the section that comes together most easily. You can always go back to write the introduction later.

We also have helpful handouts on some of the next steps in your writing process, such as reorganizing drafts and argument .

Remember, once you’ve begun the paper, you can stop and try another brainstorming technique whenever you feel stuck. Keep the energy moving and try several techniques to find what suits you or the particular project you are working on.

How can technology help?

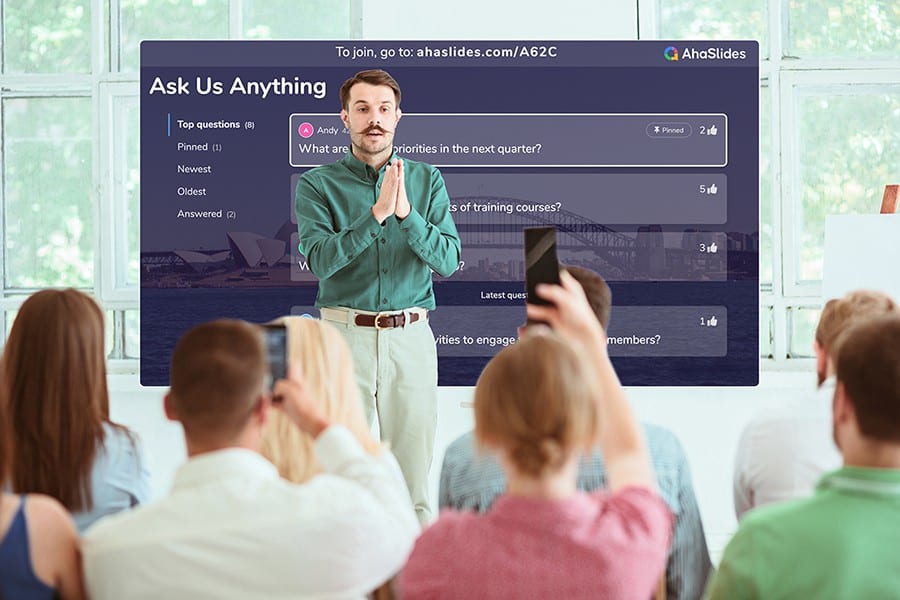

Need some help brainstorming? Different digital tools can help with a variety of brainstorming strategies:

Look for a text editor that has a focus mode or that is designed to promote free writing (for examples, check out FocusWriter, OmmWriter, WriteRoom, Writer the Internet Typewriter, or Cold Turkey). Eliminating visual distractions on your screen can help you free write for designated periods of time. By eliminating visual distractions on your screen, these tools help you focus on free writing for designated periods of time. If you use Microsoft Word, you might even try “Focus Mode” under the “View” tab.

Clustering/mapping. Websites and applications like Mindomo , TheBrain , and Miro allow you to create concept maps and graphic organizers. These applications often include the following features:

- Connect links, embed documents and media, and integrate notes in your concept maps

- Access your maps across devices

- Search across maps for keywords

- Convert maps into checklists and outlines

- Export maps to other file formats

Testimonials

Check out what other students and writers have tried!

Papers as Puzzles : A UNC student demonstrates a brainstorming strategy for getting started on a paper.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Allen, Roberta, and Marcia Mascolini. 1997. The Process of Writing: Composing Through Critical Thinking . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Cameron, Julia. 2002. The Artist’s Way: A Spiritual Path to Higher Creativity . New York: Putnam.

Goldberg, Natalie. 2005. Writing Down the Bones: Freeing the Writer Within , rev. ed. Boston: Shambhala.

Rosen, Leonard J. and Laurence Behrens. 2003. The Allyn & Bacon Handbook , 5th ed. New York: Longman.

University of Richmond. n.d. “Main Page.” Writer’s Web. Accessed June 14, 2019. http://writing2.richmond.edu/writing/wweb.html .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The Writing Process

Making expository writing less stressful, more efficient, and more enlightening, search form, you are here.

- Step 1: Generate Ideas

Brainstorming

"It is better to have enough ideas for some of them to be wrong, than to always be right by having no ideas at all." —Edward de Bono

Most people have been taught how to brainstorm, but review these instructions to make sure you understand all aspects of it.

- Don't write in complete sentences, just words and phrases, and don't worry about grammar or even spelling;

- Again, do NOT judge or skip any idea, no matter how silly or crazy it may initially seem; you can decide later which ones are useful and which are not, but if you judge now, you may miss a great idea or connection;

- Do this for 15, 20, or (if you're on a roll) even 30 minutes--basically until you think you have enough material to start organizing or, if needed, doing research.

Below is a sample brainstorm for an argument/research paper on the need for a defense shield around the earth:

Photo: "Brainstorm" ©2007 Jonathan Aguila

Home / Guides / Writing Guides / Writing Tips / How to Brainstorm for an Essay

How to Brainstorm for an Essay

Once you get going on a paper, you can often get into a groove and churn out the bulk of it fairly quickly. But choosing or brainstorming a topic for a paper—especially one with an open-ended prompt—can often be a challenge.

You’ve probably been told to brainstorm ideas for papers since you were in elementary school. Even though you might feel like “brainstorming” is an ineffective method for actually figuring out what to write about, it really works. Everyone thinks through ideas differently, but here are some tips to help you brainstorm more effectively regardless of what learning style works best for you:

Tip #1: Set an end goal for yourself

Develop a goal for your brainstorm. Don’t worry—you can go into brainstorming without knowing exactly what you want to write about, but you should have an idea of what you hope to gain from your brainstorming session. Do you want to develop a list of potential topics? Do you want to come up with ideas to support an argument? Have some idea about what you want to get out of brainstorming so that you can make more effective use of your time.

Tip #2: Write down all ideas

Sure, some of your ideas will be better than others, but you should write all of them down for you to look back on later. Starting with bad or infeasible ideas might seem counterintuitive, but one idea usually leads to another one. Make a list that includes all of your initial thoughts, and then you can go back through and pick out the best one later. Passing judgment on ideas in this first stage will just slow you down.

Tip #3: Think about what interests you most

Students usually write better essays when they’re exploring subjects that they have some personal interest in. If a professor gives you an open-ended prompt, take it as an opportunity to delve further into a topic you find more interesting. When trying to find a focus for your papers, think back on coursework that you found engaging or that raised further questions for you.

Tip #4: Consider what you want the reader to get from your paper

Do you want to write an engaging piece? A thought-provoking one? An informative one? Think about the end goal of your writing while you go through the initial brainstorming process. Although this might seem counterproductive, considering what you want readers to get out of your writing can help you come up with a focus that both satisfies your readers and satisfies you as a writer.

Tip #5: Try freewriting

Write for five minutes on a topic of your choice that you think could be worth pursuing—your idea doesn’t have to be fully fleshed out. This can help you figure out whether it’s worth putting more time into an idea or if it doesn’t really have any weight to it. If you find that you don’t have much to say about a particular topic, you can switch subjects halfway through writing, but this can be a good way to get your creative juices flowing.

Tip #6: Draw a map of your ideas

While some students might prefer the more traditional list methods, for more visual learners, sketching out a word map of ideas may be a useful method for brainstorming. Write the main idea in a circle in the center of your page. Then, write smaller, related ideas in bubbles further from the center of the page and connect them to your initial idea using lines. This is a good way to break down big ideas and to figure out whether they are worth writing about.

Tip #7: Enlist the help of others

Sometimes it can be difficult coming up with paper topics on your own, and family and friends can prove to be valuable resources when developing ideas. Feel free to brainstorm with another person (or in a group). Many hands make light work—and some students work best when thinking through ideas out loud—so don’t be afraid to ask others for advice when trying to come up with a paper topic.

Tip #8: Find the perfect brainstorming spot

Believe it or not, location can make a BIG difference when you’re trying to come up with a paper topic. Working while watching TV is never a good idea, but you might want to listen to music while doing work, or you might prefer to sit in a quiet study location. Think about where you work best, and pick a spot where you feel that you can be productive.

Tip #9: Play word games to help generate ideas

Whether you hate playing word games or think they’re a ton of fun, you might want to try your hand at a quick round of Words With Friends or a game of Scrabble. These games can help get your brain working, and sometimes ideas can be triggered by words you see. Get a friend to play an old-fashioned board game with you, or try your hand at a mobile app if you’re in a time crunch.

Tip #10: Take a break to let ideas sink in

Brainstorming is a great way to get all of your initial thoughts out there, but sometimes you need a bit more time to process all of those ideas. Stand up and stretch—or even take a walk around the block—and then look back on your list of ideas to see if you have any new thoughts on them.

For many students, the most difficult process of paper writing is simply coming up with an idea about what to write on. Don’t be afraid to get all of your ideas out there through brainstorming, and remember that all ideas are valid. Take the time necessary to sort through all of your ideas, using whatever method works best for you, and then get to writing—but don’t be afraid to go back to the drawing board if a new inspiration strikes.

EasyBib Writing Resources

Writing a paper.

- Academic Essay

- Argumentative Essay

- College Admissions Essay

- Expository Essay

- Persuasive Essay

- Research Paper

- Thesis Statement

- Writing a Conclusion

- Writing an Introduction

- Writing an Outline

- Writing a Summary

EasyBib Plus Features

- Citation Generator

- Essay Checker

- Expert Check Proofreader

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tools

Plagiarism Checker

- Spell Checker

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Grammar and Plagiarism Checkers

Grammar Basics

Plagiarism Basics

Writing Basics

Upload a paper to check for plagiarism against billions of sources and get advanced writing suggestions for clarity and style.

Get Started

Writing Studio

Invention (aka brainstorming), what is “invention”.

In an effort to make our handouts more accessible, we have begun converting our PDF handouts to web pages. Download this page as a PDF: Invention Return to Writing Studio Handouts

Invention (also referred to as brainstorming) is the stage of the writing process during which writers discover the ideas upon which their essays will focus. During this stage, writers tend to overcome some of the anxiety they might have about writing a paper, and in many cases, actually become excited about it. Although invention usually occurs at the beginning of the writing process, exercises aimed at facilitating invention can be helpful at many stages of writing. Some of the best writers return to this stage a number of times while composing drafts of their essays.

Recommended Invention Techniques

Freewriting.

Read through your assignment and choose a topic, theme, or question that comes to mind. Write for 10-15 minutes in response to this idea – do not lift your pen from the paper or your hands from the keyboard.

When you are finished, read through your draft and underline or circle ideas that might lead you to a thesis for your paper. Consider asking a classmate or friend to read what you’ve written and ask questions about your ideas and topics.

After freewriting, read through what you have written and underline a phrase or sentence that you think is particularly effective or that expresses your ideas most clearly. Write this at the top of a new sheet of paper and use it to guide a new freewrite.

Repeat this process several times. The more you write and select, the more you will be able to refine your ideas.

Talk to Yourself

Some people often find themselves saying, “I know what I want to say. It’s just that I can’t figure out how to put it in writing.” If this is the case for you, try dictating your thoughts on a digital recording device. After several minutes, listen to what you’ve recorded and write down ideas you want to incorporate into your paper.

If you don’t have a recording device, ask a friend to write down some of the main points you make as you talk about your ideas.

List all the ideas you can think of that are connected to the topic or the subject you want to explore. Consider any idea or observation as valid and worthy of listing (go for quantity at this point). List quickly and then set your list aside for a few minutes. Come back and read your list and then do the listing exercise again.

Using Charts or Shapes

Use phrases or words that are central to your topic and try to arrange them spatially in a graph, grid, table, or chart. How do the different spatial representations help you see the relationships among your ideas? If you can’t imagine the shape of a chart at first, just put the words on a page and draw lines between or around them.

Break Down the Assignment

Sometimes prompts are so complicated that they can seem overwhelming. Students often ask: There’s so much to do, where should I start? Try to break the assignment down into its constituent parts:

- The general topic, like “The relationship between tropical fruits and colonial powers.”

- A specific subtopic or required question, like “How did the availability of multiple tropical fruits influence competition among colonial powers trading from the larger Caribbean islands during the 19th century?”

- A single term or phrase that seems to repeat in the material you’ve read or the ideas you’ve been considering. For example, if have you seen the words “increased competition” several times in the class materials you’ve been reading about tropical fruit exports, you could brainstorm variations on the phrase within the context of those readings or focus on variations of each component of the phrase (i.e., “increased” and “competition”).

Once you have identified the major parts of the topic, try to figure out what you are being asked to think about in the assignment. What questions are you expected to answer? Are there related questions that need to be addressed in order to answer the primary questions? If so, what are they?

Defining Terms

In your own words, write definitions for key terms or concepts given in the assignment. Find other definitions of those terms in your course readings, the dictionary, or through conversations and then compare the definitions to your own. Keep these definitions in mind as you begin to write your essay.

Summarizing Positions

Summarize the positions of relevant authors from your course readings or research. Do you agree or disagree with their ideas, methods, or approaches? How do your interests overlap with the positions of the authors in question? Try to be brief in your descriptions. Write a paragraph or up to a page describing a reading or a position.

Get together with a group of classmates and have each person write down her or his tentative topic or thesis at the top of a blank sheet of paper. Pass the sheets around from left to right so that each person can write down a thoughtful question or suggest related ideas to think about.

Compare / Contrast Matrix

If your assignment asks you to compare or contrast two concepts, texts, subjects, etc., try to organize your thoughts in a compare/contrast matrix by focusing on the attributes you will consider in your draft. These attributes should establish the key points of comparison or contrast with which you will deal in your essay.

Last revised: 07/2008 | Adapted for web delivery: 05/2021

In order to access certain content on this page, you may need to download Adobe Acrobat Reader or an equivalent PDF viewer software.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

College admissions

Course: college admissions > unit 4.

- Writing a strong college admissions essay

- Avoiding common admissions essay mistakes

Brainstorming tips for your college essay

- How formal should the tone of your college essay be?

- Taking your college essay to the next level

- Sample essay 1 with admissions feedback

- Sample essay 2 with admissions feedback

- Student story: Admissions essay about a formative experience

- Student story: Admissions essay about personal identity

- Student story: Admissions essay about community impact

- Student story: Admissions essay about a past mistake

- Student story: Admissions essay about a meaningful poem

- Writing tips and techniques for your college essay

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Video transcript

How to Brainstorming Essays with 100+ Ideas in 2024

Anh Vu • 03 April, 2024 • 10 min read

We have all been there. Teachers assign us an essay due next week. We tremble. What should we write about? What problems to tackle? Would the essay be original enough? So, how do we brainstorming essays ?

It’s like you are venturing into an unexplored abyss. But fret not, because making a brainstorm for essay writing can actually help you plan, execute and nail that A+

Here’s how to brainstorm for essays …

Table of Contents

Engagement tips with ahaslides.

- What is brainstorming?

- Write ideas unconsciously

- Draw a mind map

- Get on Pinterest

- Try a Venn Diagram

- Use a T-Chart

- Online tools

- More AhaSlides Tools

- 14 brainstorming rules to Help You Craft Creative Ideas in 2024

- 10 brainstorm questions for School and Work in 2024

Easy Brainstorm Templates

Get free brainstorming templates today! Sign up for free and take what you want from the template library!

What is Brainstorming?

Every successful creation starts with a great idea, which is actually the hardest part in many cases.

Brainstorming is simply the free-flowing process of coming up with ideas. In this process, you come up with a whole bunch of ideas without guilt or shame . Ideas can be outside of the box and nothing is considered too silly, too complex, or impossible. The more creative and free-flowing, the better.

The benefits of brainstorming can surprise you:

- Increases your creativity : Brainstorming forces your mind to research and come up with possibilities, even unthinkable ones. Thus, it opens your mind to new ideas.

- A valuable skill: Not just in high school or college, brainstorming is a lifelong skill in your employment and pretty much anything that requires a bit of thought.

- Helps organise your essay : At any point in the essay you can stop to brainstorm ideas. This helps you structure the essay, making it coherent and logical.

- It can calm you: A lot of the stress in writing comes from not having enough ideas or not having a structure. You might feel overwhelmed by the hoards of information after the initial research. Brainstorming ideas can help organise your thoughts, which is a calming activity that can help you avoid stress.

Essay brainstorming in an academic setting works a bit differently than doing it in a team. You’ll be the only one doing the brainstorming for your essay, meaning that you’ll be coming up with and whittling down the ideas yourself.

Learn to use idea board to generate ideas effectively with AhaSlides

Here are five ways to do just that…

Brainstorming Essays – 5 Ideas

Idea #1 – write ideas unconsciously.

In “ Blink: The Power of Thinking without Thinking ,” Malcolm Gladwell points out how our unconscious is many times more effective than our conscious in decision-making.

In brainstorming, our unconscious can differentiate between relevant and irrelevant information in a split second. Our intuition is underrated. It can often produce better judgments than a deliberate and thoughtful analysis as it cuts through all the irrelevant information and focuses on just the key factors.

Even if the ideas you come up with in essay brainstorming seem insignificant, they might lead you to something great later. Trust yourself and put whatever you think of on paper; if you don’t focus on self-editing, you may come up with some ingenious ideas.

That’s because writing freely can actually negate writer’s block and help your unconscious run wild!

Idea #2 – Draw a Mind Map

Brains love visual communication and mind maps are exactly that.

Our thoughts rarely arrive in easily digestible chunks; they’re more like webs of information and ideas that extend forward at any given time. Keeping track of these ideas is tough, but manifesting them all in a mind map can help you get more ideas and both understand and retain them better.

To draw an effective mind map, here are some tips:

- Create a central idea : In the middle of your paper draw a central topic/idea which represents the starting point of your essay and then branch out to different arguments. This central visual will act as visual stimulus to trigger your brain and remind you constantly about the core idea.

- Add keywords : When you add branches to your mind map, you will need to include a key idea. Keep these phrases as brief as possible to generate a greater number of associations and keep space for more detailed branches and thoughts.

- Highlight branches in different colours : Coloured pen is your best friend. Apply different colours to each key idea branch above. This way, you can differentiate arguments.

- Use visual signifiers : Since visuals and colours are the core of a mind map, use them as much as you can. Drawing small doodles works great because it mimics how our mind unconsciously arrives at ideas. Alternatively, if you’re using an online brainstorming tool , you can real images and embed them in.

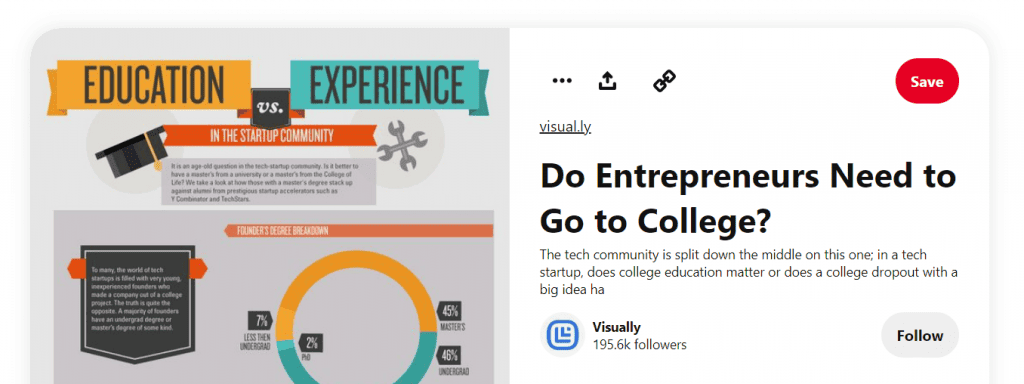

Idea #3 – Get on Pinterest

Believe it or not, Pinterest is actually a pretty decent online brainstorming tool. You can use it to collect images and ideas from other people and put them all together to get a clearer picture of what your essay should talk about.

For example, if you’re writing an essay on the importance of college, you could write something like Does college matter? in the search bar. You might just find a bunch of interesting infographics and perspectives that you never even considered before.

Save that to your own idea board and repeat the process a few more times. Before you know it, you’ll have a cluster of ideas that can really help you shape your essay!

Idea #4 – Try a Venn Diagram

Are you trying to find similarities between two topics? Then the famous Venn diagram technique could be the key, as it clearly visualises the characteristics of any concept and shows you which parts overlap.

Popularised by British Mathematician John Venn in the 1880s, the diagram traditionally illustrates simple set relationships in probability, logic, statistics, linguistics and computer science.

You start by drawing two (or more) intersecting circles and labelling each one with an idea you’re thinking of. Write the qualities of each idea in their own circles, and the ideas they share in the middle where the circles intersect.

For example, in the student debate topic Marijuana should be legal because alcohol is , you can have a circle listing the positives and negatives of marijuana, the other circle doing the same for alcohol, and the middle ground listing the effects they share between them.

Idea #5 – Use a T-Chart

This brainstorming technique works well to compare and contrast, thanks to the fact that it’s super simple.

All you have to do is write the title of the essay at the top of your paper then split the rest of it into two. On the left side, you’ll write about the argument for and on the right side, you’ll write about the argument against .

For example, in the topic Should plastic bags be banned? you can write the pros in the left column and the cons in the right. Similarly, if you’re writing about a character from fiction, you can use the left column for their positive traits and the right side for their negative traits. Simple as that.

💡 Need more? Check out our article on How to Brainstorm Ideas Properly !

Online Tools to Brainstorm for Essays

Thanks to technology, we no longer have to rely on just a piece of paper and a pen. There are a plethora of tools, paid and free, to make your virtual brainstorming session easier…

- Freemind is a free, downloadable software for mind mapping. You can brainstorm an essay using different colours to show which parts of the article you’re referring to. The color-coded features keep track of your essays as you write.

- MindGenius is another app where you can curate and customise your own mind map from an array of templates.

- AhaSlides is a free tool for brainstorming with others. If you’re working on a team essay, you can ask everyone to write down their ideas for the topic and then vote on whichever is their favourite.

- Miro is a wonderful tool for visualising pretty much anything with a lot of moving parts. It gives you an infinite board and every arrow shape under the sun to construct and align the parts of your essay.

More AhaSlides Tools to Make your Brainstorming Sessions Better!

- Use AhaSlides Live Word Cloud Generator to gather more ideas from your crowds and classrooms!

- Host Free Live Q&A to gain more insights from the crowd!

- Gamify engagement with a spin the wheel ! It’s a fun and interactive way to boost participation

- Instead of boring MCQ questions, learn how to use online quiz creator now!

- Random your team to gain more fun with AhaSlides random team generator !

Final Say on Brainstorming Essays

Honestly, the scariest moment of writing an essay is before you start but brainstorming for essays before can really make the process of writing an essay less scary. It’s a process that helps you burst through one of the toughest parts of essay and writing and gets your creative juices flowing for the content ahead.

💡 Besides brainstorming essays, are you still looking for brainstorming activities? Try some of these !

Tips to Engage with Polls & Trivia

More from AhaSlides

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

- Introduction

Good writing requires good ideas—intriguing concepts and analysis that are clearly and compellingly arranged. But good ideas don’t just appear like magic. All writers struggle with figuring out what they are going to say. And while there is no set formula for generating ideas for your writing, there is a wide range of established techniques that can help you get started.

This page contains information about those techniques. Here you’ll find details about specific ways to develop thoughts and foster inspiration. While many writers employ one or two of these strategies at the beginning of their writing processes in order to come up with their overall topic or argument, these techniques can also be used any time you’re trying to figure out how to effectively achieve any of your writing goals or even just when you’re not sure what to say next.

What is Invention?

Where do ideas come from? This is a high-level question worthy of a fascinating TED Talk or a Smithsonian article , but it also represents one of the primary challenges of writing. How do we figure out WHAT to write?

Even hundreds of years ago, people knew that a text begins with an idea and that locating this idea and determining how to develop it requires work. According to classical understandings of rhetoric, the first step of building an argument is invention. As Roman thinker Cicero argued, people developing arguments “ought first to find out what [they] should say” ( On Oratory and Orators 3.31). Two hundred years before Cicero, the Greek philosopher Aristotle detailed a list of more than two dozen ideas a rhetor might consider when figuring out what to say about a given topic ( On Rhetoric , 2.23). For example, Aristotle suggested that a good place to start is to define your key concepts, to think about how your topic compares to other topics, or to identify its causes and effects. (For ideas about using Aristotle’s advice to generate ideas for your own papers, check out this recommended technique .)

More recently, composition scholar Joseph Harris has identified three values important for writers just starting a project. Writers at early stages in their writing process can benefit from being: Receptive to unexpected connections You never know when something you read or need to write will remind you of that movie you watched last weekend or that anthropology theory you just heard a lecture about or that conversation you had with a member of your lab about some unexpected data you’ve encountered. Sometimes these connections will jump out at you in the moment or you’ll suddenly remember them while you’re vacuuming the living room. Harris validates the importance of “seizing hold of those ideas that do somehow come to you” (102). While you can’t count on these kinds of serendipities, be open to them when they occur. Be ready to stop and jot them down! Patient Harris supports the value of patience and “the usefulness of boredom, of letting ideas percolate” (102). It can take time and long consideration to think of something new. When possible, give yourself plenty of time so that your development of ideas is not stifled by an immediate due date. Compelled by the unknown According to Harris, “a writer often needs to start not from a moment of inspiration ( eureka! ) but from the need to work through a conceptual problem or roadblock. Indeed, I’d suggest that most academic writing begins with such questions rather than insights, with difficulties in understanding rather than moments of mastery” (102). Sometimes a very good place to begin is with what you don’t know, with the questions and curiosities that you genuinely want resolved.

In what follows, we describe ten techniques that you can select from and experiment with to help guide your invention processes. Depending on your writing preferences, context, and audience, you might find some more productive than others. Also, it might be useful to utilize various techniques for different purposes. For example, brainstorming might be great for generating a variety of possible ideas, but looped freewriting might help you develop those ideas. Think of this list as a collection of recommended possibilities to implement at your discretion. However, we think the first technique described below—“Analyzing the Assignment or Task”—is a great starting point for all writers.

Any of these strategies can be useful for generating ideas in connection to any writing assignment. Even if the paper you’re writing has a set structure (e.g., scientific reports’ IMRAD format or some philosophy assignments’ prescribed argumentative sequence), you still have to invent and organize concepts and supporting evidence within each section. Additionally, these techniques can be used at any stage in your writing process. Your ideas change and develop as you write, and sometimes when you’re in the middle of a draft or when you’re embarking on a major revision, you find yourself rethinking key elements of your paper. At these moments, it might be useful to turn to some of these invention techniques as a way to slow down and capture the ephemeral thoughts and possibilities swirling around your writing tasks. These practices can help guide you to new ideas, questions, and connections. No matter what you’re writing or where you are in the process, we encourage you to experiment with invention strategies you may not have tried before. Mix and match. Be as creative and adventurous with how you generate ideas just as you are creative and adventurous with what ideas you generate.

Some Invention Techniques

Analyzing the assignment or task.

What do I do? If you are writing a paper in response to a course instructor’s assignment, be sure to read the prompt carefully while paying particular attention to all of its requirements and expectations. It could be that the assignment is built around a primary question; if so, structure your initial thoughts around possible answers to that question. If it isn’t, use your close consideration of this assignment to recast the prompt as a question.

The following list of questions are ones that you can ask of the assignment in order to understand its focus and purpose as well as to begin developing ideas for how to effectively respond to its intensions. You may want to underline key terms and record your answers to these questions:

- When is this due?

- How long is supposed to be?

- Is the topic given to me?

- If I get to choose my topic, are there any stipulations about the kind of topic and I can choose?

- What am I expected to do with this topic? Analyze it? Report about it? Make an argument about it? Compare it to something else?

- Who is my audience and what does this audience know, believe, and value about my topic?

- What is the genre of this writing (i.e., a lab report, a case study, a research paper, a reflection, a scholarship essay, an analysis of a work of literature or a painting, a summary and analysis of a reading, a literature review, etc.), and what does writing in this genre usually look like, consist of, or do?

Why is this technique useful? Reading over the assignment prompt may sound like an obvious starting point, but it is very important that your invention strategies are informed by the expectations your readers have about your writing. For example, you might brainstorm a fascinating thesis about how Jules Verne served as a conceptual progenitor of the nuclear age, but if your assignment is asking you to describe the differences between fission and fusion and provide examples, this great idea won’t be very helpful. Before you let your ideas run free, make sure you fully understand the boundaries and possibilities provided by the assignment prompt.

Additionally, some assignments begin to do the work of invention for you. Instructors sometimes identify specifically what they want you to write about. Sometimes they invite you to choose from several guiding questions or a position to support or refute. Sometimes the genre of the text can help you identify how this kind of assignment should begin or the order your ideas should follow. Knowing this can help you develop your content. Before you start conjuring ideas from scratch, make sure you glean everything you can from the prompt.

Finally, just sitting with the assignment and thinking through its guidelines can sometimes provide inspiration for how to respond to its questions or approach its challenges.

Reading Again

What do I do? When your writing task is centered around analyzing a primary source, information you collected, or another kind of text, start by rereading it. Perhaps you are supposed to develop an argument about an interview you conducted, an article or short story you read, an archived letter you located, or even a painting you viewed or a particular set of data. In order to develop ideas about how to approach this object of analysis, read and analyze this text again. Read it closely. Be prepared to take notes about its interesting features or the questions this second encounter raises. You can find more information about rereading literature to write about it here and specific tips about reading poetry here .

Why is this technique useful? When you first read a text, you gain a general overview. You find out what is happening, why it’s happening, and what the argument is. But when you reread that same text, your attention is freed to attend to the details. Since you know where the text is heading, you can be alert to patterns and anomalies. You can see the broader significance of smaller elements. You can use your developing familiarity with this text to your advantage as you become something of a minor expert whose understanding of this object deepens with each re-read. This expertise and insight can help lead you towards original ideas about this text.

Brainstorming/Listing

What do I do? First, consider your prompt, assignment, or writing concern (see “Analyzing the Assignment or Task”). Then start jotting down or listing all possible ideas for what you might write in response. The goal is to get as many options listed as possible. You may wish to develop sub-lists or put some of your ideas into different categories, but don’t censor or edit yourself. And don’t worry about writing in full sentences. Write down absolutely everything that comes to mind—even preposterous solutions or unrealistic notions. If you’re working on a collaborative project, this might be a process that you conduct with others, something that involves everyone meeting at the same time to call out ideas and write them down so everyone can see them. You might give yourself a set amount of time to develop your lists, or you might stretch out the process across a couple of days so that you can add new ideas to your lists whenever they occur to you.

Why is this technique useful? The idea behind this strategy is to open yourself up to all possibilities because sometimes even the most seemingly off-the-wall idea has, at its core, some productive potential. And sometimes getting to that potential first involves recognizing the outlandish. There is time later in your writing process to think critically about the viability of your options as well as which possibilities effectively respond to the prompt and connect to your audience. But brainstorming or listing sets those considerations aside for a moment and invites you to open your imagination up to all options.

Freewriting

What do I do? Sit down and write about your topic without stopping for a set amount of time (i.e., 5-10 minutes). The goal is to generate a continuous, forward-moving flow of text, to track down all of your thoughts about this topic, as if you are thinking on the page. Even if all you can think is, “I don’t know what to write,” or, “Is this important?” write that down and keep on writing. Repeat the same word or phrase over again if you need to. If you’re writing about an unfamiliar topic, maybe start by writing down everything you know about it and then begin listing questions you have. Write in full sentences or in phrases, whatever helps keep your thoughts flowing. Through this process, don’t worry about errors of any kind or gaps in logic. Don’t stop to reread or revise what you wrote. Let your words follow your thought process wherever it takes you.

Why is this technique useful? The purpose of this technique is to open yourself up to the possibilities of your ideas while establishing a record of what those ideas are. Through the unhindered nature of this open process, you are freed to stumble into interesting options you might not have previously considered.

Invisible Writing

What do I do? In this variation of freewriting, you dim your computer screen so that you can’t see what you’ve written as you type out your thoughts.

Why is this technique useful? This is a particularly useful technique if while you are freewriting you just can’t keep yourself from reviewing, adjusting, or correcting your writing. This technique removes that temptation to revise by eliminating the visual element. By temporarily limiting your ability to see what you’ve written, this forward-focused method can help you keep pursuing thoughts wherever they might go.

Looped Freewriting

What do I do? This is another variation of freewriting. After an initial round of freewriting or invisible writing, go back through what you’ve written and locate one idea, phrase, or sentence that you think is really compelling. Make that the starting point for another round of timed freewriting and see where an uninterrupted stretch of writing starting from that point takes you. After this second round of freewriting, identify a particular part of this new text that stands out to you and make that the opening line for your third round of freewriting. Keep repeating this process as many times as you find productive.

Why is this technique useful? Sometimes this technique is called “mining” because through it writers are able to drill into the productive bedrock of ideas as well as unearth and discover latent possibilities. By identifying and expanding on concepts that you find particularly intriguing, this technique lets you focus your attention on what feels most generative within your freewritten text, allowing you to first narrow in and then elaborate upon those ideas.

Talking with Someone

What do I do? Find a generous and welcoming listener and talk through what you need to write and how you might go about writing it. Start by reading your assignment prompt aloud or just informally explaining what you are thinking about saying or arguing in your paper. Then be open to your listener’s reactions, curiosities, suggestions, and questions. Invite your listener to repeat in his or her own words what you’ve been saying so that you can hear how someone else is understanding your ideas. While a friend or classmate might be able to serve in this role, writing center tutors are also excellent interlocutors. If you are a currently enrolled UW-Madison student, you are welcome to make an appointment at our main writing center, stop by one of our satellite locations , or even set up a Virtual Meeting to talk with a tutor about your assignment, ideas, and possible options for further exploration.

Why is this technique useful? Sometimes it’s just useful to hear yourself talk through your ideas. Other times you can gain new insight by listening to someone else’s understanding of or interest in your assignment or topic. A genuinely curious listener can motivate you to think more deeply and to write more effectively.

Reading More

Sometimes course instructors specifically ask that you do your analysis on your own without consulting outside sources. When that is the case, skip this technique and consider implementing one of the others instead.

What do I do? Who else has written about your topic, run the kind of experiments you’ve developed, or made an argument like the one you’re interested in? What did they say about this issue? Do some internet searches for well-cited articles on this concept. Locate a book in the library stacks about this topic and then look at the books that are shelved nearby. Read where your interests lead you. Take notes about things other authors say that you find intriguing, that you have questions about, or that you disagree with. You might be able to use any of these responses to guide your developing paper. (Make sure you also record bibliographic information for any texts you want to incorporate in your paper so that you can correctly cite those authors.)

Why is this technique useful? Exploring what others have written about your topic can be a great way to help you understand this issue more fully. Through reading you can locate support for your ideas and discover arguments you want to refute. Reading about your topic can also be a way of figuring out what motivates you about this issue. Which texts do you want to read more of? Why? Capitalize on and expand upon these interests.

Visualizing Ideas

Mindmapping, clustering, or webbing.

What do I do? This technique is a form of brainstorming or listing that lets you visualize how your ideas function and relate. To make this work, you might want to locate a large space you can write on (like a whiteboard) or download software that lets you easily manipulate and group text, images, and shapes (like Coggle , FreeMind , or MindMapple ). Write down a central idea then identify associated concepts, features, or questions around that idea. If some of those thoughts need expanding, continue this map, cluster, or web in whatever direction is productive. Make lines attaching various ideas. Add and rearrange individual elements or whole subsets as necessary. Use different shapes, sizes, or colors to indicate commonalities, sequences, or relative importance.

Why is this technique useful? This technique allows you to generate ideas while thinking visually about how they function together. As you follow lines of thought, you can see which ideas can be connected, where certain pathways lead, and what the scope of your project might look like. Additionally, by drawing out a map of you may be able to see what elements of your possible paper are underdeveloped and may benefit from more focused brainstorming.

The following sample mindmap illustrates how this invention technique might be used to generate ideas for an environmental science paper about Lake Mendota, the Wisconsin lake just north of UW-Madison. The different branches and connections show how your mind might travel from one idea to the next. It’s important to note, that not all of these ideas would appear in the final draft of this eventual paper. No one is likely to write a paper about all the different nodes and possibilities represented in a mindmap. The best papers focus on a tightly defined question. But this does provide many potential places to begin and refine a paper on this topic. This mindmap was created using shapes and formatting options available through PowerPoint.

Notecarding

What do I do? This technique can be especially useful after you’ve identified a range of possibilities but aren’t sure how they might work together. On individual index cards, post-its, or scraps of paper, write out the ideas, questions, examples, and/or sources you’re interested in utilizing. Find somewhere that you can spread these out and begin organizing them in whatever way might make sense. Maybe group some of them together by subtopic or put them in a sequential order. Set some across from each other as conflicting opposites. Make the easiest organization decisions first so that the more difficult cards can be placed within an established framework. Take a picture or otherwise capture the resulting schemata. Of course, you can also do this same kind of work on a computer through software like Prezi or even on a PowerPoint slide.

Why is this technique useful? This technique furthers the mindmapping/clustering/webbing practice of grouping and visualizing your thoughts. Once ideas have been generated, notecarding invites you to think and rethink about how these ideas relate. This invention strategy allows you to see the big picture of your writing. It also invites you to consider how the details of sections and subsections might connect to each other and the surrounding ideas while giving you a sense of possible sequencing options.

The following example shows what notecarding might look like for a paper being written on the Clean Lakes Alliance—a not-for-profit organization that promotes the improvement of water quality in the bodies of water around Madison, Wisconsin. Key topics, subtopics, and possible articles were brainstormed and written on pieces of paper. These elements were then arranged to identify possible relationships and general organizational structures.

What do I do? Take the ideas, possibilities, sources, and/or examples you’ve generated and write them out in the order of what you might address first, second, third, etc. Use subpoints to subordinate certain ideas under main points. Maybe you want to identify details about what examples or supporting evidence you might use. Maybe you just want to keep your outline elements general. Do whatever is most useful to help you think through the sequence of your ideas. Remember that outlines can and should be revised as you continue to develop and refine your paper’s argument.

Why is this technique useful? This practice functions as a more linear form of notecarding. Additionally, outlines emphasize the sequence and hierarchy of ideas—your main points and subpoints. If you have settled on several key ideas, outlining can help you consider how to best guide your readers through these ideas and their supporting evidence. What do your readers need to understand first? Where might certain examples fit most naturally? These are the kinds of questions that an outline can clarify.

Asking Questions

Topoi questions.

In the introduction, we referenced the list that Aristotle developed of the more than two dozen ideas a person making an argument might use to locate the persuasive possibilities of that argument. Aristotle called these locations for argumentative potential “topoi.” Hundreds of years later, Cicero provided additional advice about the kinds of questions that provide useful fodder for developing arguments. The following list of questions is based on the topoi categories that Aristotle and Cicero recommended.

What do I do? Ask yourself any of these questions regarding your topic and write out your answers as a way of identifying and considering possible venues for exploration. Questions of definition: What is ____? How do we understand what ____ is? What is ____ comprised of?

Questions of comparison: What are other things that ____ is like? What are things that are nothing like ____?

Questions of relationship: What causes ____? What effects does ____ have? What are the consequences of ____?

Questions of circumstances: What has happened with ____ in the past? What has not happened with ____ in the past? What might possibly happen with ____ in the future? What is unlikely to happen with ____ in the future?

Questions of testimony: Who are the experts on ____ and what do they say about it? Who are people who have personal experience with ____ and what do they think about it?

If any of these questions initiates some interesting ideas, ask follow-up questions like, “Why is this the case? How do I know this? How might someone else answer this question differently?”

Why is this technique useful? The questions listed above draw from what both Aristotle and Cicero said about ways to go about inventing ideas. Questions such as these are tried-and-true methods that have guided speakers and writers towards possible arguments for thousands of years.

Journalistic Questions

What do I do? Identify your topic, then write out your answers in response to these questions: Who are the main stakeholders or figures connected to ____? What is ____? Where can we find ____? Where does this happen? When or under what circumstances does ____ occur? Why is ____ an issue? Why does it occur? Why is it important? How does ____ happen?

Why is this technique useful? This line of questioning is designed to make sure that you understand all the basic information about your topic. Traditionally, these are the kinds of questions that journalists ask about an issue that they are preparing to report about. These questions also directly relate to the Dramatistic Pentad developed by literary and rhetorical scholar Kenneth Burke. According to Burke, we can analyze anyone’s motives by considering these five parts of a situation: Act ( what ), Scene ( when and where ), Agent ( who ), Agency ( how ), and Purpose ( why ). By using these questions to identify the key elements of a topic, you may recognize what you find to be most compelling about it, what attracts your interest, and what you want to know more about.

Particle, Wave, Field Questions

One way to start generating ideas is to ask questions about what you’re studying from a variety of perspectives. This particular strategy uses particles, waves, and fields as metaphorical categories through which to develop various questions by thinking of your topic as a static entity (particle), a dynamic process (wave), and an interrelated system (field).

What do I do?

Ask yourself these questions about your issue or topic and write down your responses:

- In what ways can this issue be considered a particle, that is, a discrete thing or a static entity?

- How is this issue a wave, that is, a moving process?

- How is this issue a field, that is, a system of relationships related to other systems?

Why is this technique useful?

This way of looking at an issue was promoted by Young, Becker, and Pike in their classic text Rhetoric: Discovery and Change . The idea behind this heuristic is that anything can be considered a particle, a wave, and a field, and that by thinking of an issue in connection to each of these categories you’ll able to develop the kind of in-depth questions that experts ask about a topic. By identifying the way your topic is a thing in and of itself, an activity, and an interrelated network, you’ll be able to see what aspects of it are the most intriguing, uncertain, or conceptually rich.

The following example takes the previously considered topic—environmental concerns and Lake Mendota—and shows how this could be conceptualized as a particle, a wave, and a field as a way of generating possible writing ideas.

Particle: Consider Lake Mendota and its environmental concerns as they appear in a given moment. What are those concerns right now? What do they look like? Maybe it’s late spring and an unseasonably warm snap has caused a bunch of dead fish to wash up next to the Tenney Lock. Maybe it’s a summer weekend and no one can go swimming off the Terrace because phosphorous-boosted blue-green algae is too prevalent. Pick one, discrete environmental concern and describe it. Wave: Consider environmental concerns related to Lake Mendota as processes that have changed and will change over time. When were the invasive spiny water fleas first discovered in Lake Mendota? Where did they come from? What has been done to respond to the damage they have caused? What else could be proposed to resolve this problem. How is this (or any other environmental concern) a dynamic process? Field: Consider Lake Mendota’s environmental concerns as they relate to a range of disciplines, populations, and priorities. What recent limnology findings would be of interest to ice fishing anglers? How could the work being done on agricultural sustainability connect to the discoveries being made by chemists about the various compounds present in the water? What light could members of the Ho-Chunk nation shed on Lake Mendota’s significance? Think about how environmental and conservation concerns associated with this lake are interconnected across different community members and academic disciplines.

Moving Around

Get away from your desk and your computer screen and do whatever form of movement feels comfortable and natural for you. Get some fresh air, take a walk, go jogging, get on your bike, go for a swim, or do some yoga. There is no correct degree or intensity of movement in this process; just do what you can and what you’re most likely to enjoy. While you’re moving, you may want to zone out and give yourself a strategic break from your writing task. Or you might choose to mull your tentative ideas for your paper over in your mind. But whether you’re hoping to think of something other than your paper or you need to generate a specific idea or resolve a particular writing problem, be prepared to record quickly any ideas that come up. If bringing along paper or a small notebook and a pen is inconvenient, just texting yourself your new idea will do the trick. The objective with this technique is both to distance yourself from your writing concerns and to encourage your mind to build new connections through engaging in physical activity.

Numerous medical studies have found that aerobic exercise increases your body’s concentration of the proteins that help nerves grow in the parts of your brain where learning and higher thinking happens (Huang et al.). Similarly, from their review of the literature about how yoga benefits the brain, Desei et al. conclude that yoga boosts overall brain activity. Which is to say that moving physiologically helps you think.

Dr. Bonnie Smith Whitehouse, an associate professor of English at Belmont University and an alum of UW-Madison’s graduate program in Composition and Rhetoric Program and a former assistant director of Writing Across the Curriculum at UW-Madison, investigates the writerly benefits of walking. She provides a full treatment of how this particular form of movement can productively support writing in her book Afoot and Lighthearted: A Mindful Walking Log . In the following passage, she argues for a connection between creative processes and walking, but much of what she suggests is equally applicable to the beneficial value of other forms of movement.

A walk stimulates creativity after a ramble has concluded, when you find yourself back at your desk, before your easel, or in your studio. In 2014, Stanford University researchers Marily Opprezzo and Daniel L. Schwarz confirmed that walking increases creative ideation in real time (while the walker walkers) and shortly after (when the walker stops and sits down to create). Specifically, they found that walking led to an increase in “analogical creativity” or using analogies to develop creative relationships between things that may not immediately look connected. So when ancient Greek physician Hippocrates famously declared that walking is “the best medicine,” he seems to have had it right. When we walk, blood and oxygen circulate throughout the body’s organs and stimulate the brain. Walking’s magic is in fact threefold: it increases physical activity, boosts creativity, and brings you into the present moment.

Similarly, in her post about writing and jogging for the UW-Madison Writing Center’s blog, Literary Studies PhD student Jessie Gurd has explained:

What running allows me to do is clear my head and empty it of a grad student’s daily anxieties. Listening to music or cicadas or traffic, I can consider one thing at a time and turn it over in my mind. It’s a groove I hit after a couple of miles; I engage with the problem, question, or task I choose and roll with it until my run is over. In this physical-mental space, I sometimes feel like my own writing instructor as I tackle some stage of the writing process: brainstorming, outlining, drafting.