Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

This topic will provide an overview of major issues related to breech presentation, including choosing the best route for delivery. Techniques for breech delivery, with a focus on the technique for vaginal breech delivery, are discussed separately. (See "Delivery of the singleton fetus in breech presentation" .)

TYPES OF BREECH PRESENTATION

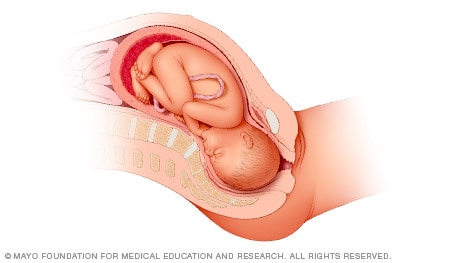

● Frank breech – Both hips are flexed and both knees are extended so that the feet are adjacent to the head ( figure 1 ); accounts for 50 to 70 percent of breech fetuses at term.

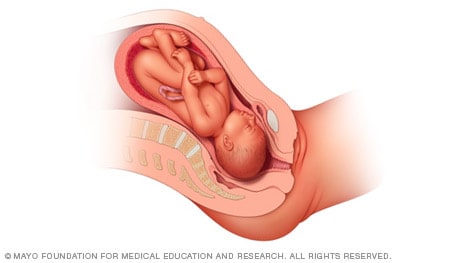

● Complete breech – Both hips and both knees are flexed ( figure 2 ); accounts for 5 to 10 percent of breech fetuses at term.

Fetal Presentation, Position, and Lie (Including Breech Presentation)

- Variations in Fetal Position and Presentation |

During pregnancy, the fetus can be positioned in many different ways inside the mother's uterus. The fetus may be head up or down or facing the mother's back or front. At first, the fetus can move around easily or shift position as the mother moves. Toward the end of the pregnancy the fetus is larger, has less room to move, and stays in one position. How the fetus is positioned has an important effect on delivery and, for certain positions, a cesarean delivery is necessary. There are medical terms that describe precisely how the fetus is positioned, and identifying the fetal position helps doctors to anticipate potential difficulties during labor and delivery.

Presentation refers to the part of the fetus’s body that leads the way out through the birth canal (called the presenting part). Usually, the head leads the way, but sometimes the buttocks (breech presentation), shoulder, or face leads the way.

Position refers to whether the fetus is facing backward (occiput anterior) or forward (occiput posterior). The occiput is a bone at the back of the baby's head. Therefore, facing backward is called occiput anterior (facing the mother’s back and facing down when the mother lies on her back). Facing forward is called occiput posterior (facing toward the mother's pubic bone and facing up when the mother lies on her back).

Lie refers to the angle of the fetus in relation to the mother and the uterus. Up-and-down (with the baby's spine parallel to mother's spine, called longitudinal) is normal, but sometimes the lie is sideways (transverse) or at an angle (oblique).

For these aspects of fetal positioning, the combination that is the most common, safest, and easiest for the mother to deliver is the following:

Head first (called vertex or cephalic presentation)

Facing backward (occiput anterior position)

Spine parallel to mother's spine (longitudinal lie)

Neck bent forward with chin tucked

Arms folded across the chest

If the fetus is in a different position, lie, or presentation, labor may be more difficult, and a normal vaginal delivery may not be possible.

Variations in fetal presentation, position, or lie may occur when

The fetus is too large for the mother's pelvis (fetopelvic disproportion).

The uterus is abnormally shaped or contains growths such as fibroids .

The fetus has a birth defect .

There is more than one fetus (multiple gestation).

Position and Presentation of the Fetus

Variations in fetal position and presentation.

Some variations in position and presentation that make delivery difficult occur frequently.

Occiput posterior position

In occiput posterior position (sometimes called sunny-side up), the fetus is head first (vertex presentation) but is facing forward (toward the mother's pubic bone—that is, facing up when the mother lies on her back). This is a very common position that is not abnormal, but it makes delivery more difficult than when the fetus is in the occiput anterior position (facing toward the mother's spine—that is facing down when the mother lies on her back).

When a fetus faces up, the neck is often straightened rather than bent,which requires more room for the head to pass through the birth canal. Delivery assisted by a vacuum device or forceps or cesarean delivery may be necessary.

Breech presentation

In breech presentation, the baby's buttocks or sometimes the feet are positioned to deliver first (before the head).

When delivered vaginally, babies that present buttocks first are more at risk of injury or even death than those that present head first.

The reason for the risks to babies in breech presentation is that the baby's hips and buttocks are not as wide as the head. Therefore, when the hips and buttocks pass through the cervix first, the passageway may not be wide enough for the head to pass through. In addition, when the head follows the buttocks, the neck may be bent slightly backwards. The neck being bent backward increases the width required for delivery as compared to when the head is angled forward with the chin tucked, which is the position that is easiest for delivery. Thus, the baby’s body may be delivered and then the head may get caught and not be able to pass through the birth canal. When the baby’s head is caught, this puts pressure on the umbilical cord in the birth canal, so that very little oxygen can reach the baby. Brain damage due to lack of oxygen is more common among breech babies than among those presenting head first.

In a first delivery, these problems may occur more frequently because a woman’s tissues have not been stretched by previous deliveries. Because of risk of injury or even death to the baby, cesarean delivery is preferred when the fetus is in breech presentation, unless the doctor is very experienced with and skilled at delivering breech babies or there is not an adequate facility or equipment to safely perform a cesarean delivery.

Breech presentation is more likely to occur in the following circumstances:

Labor starts too soon (preterm labor).

The uterus is abnormally shaped or contains abnormal growths such as fibroids .

Other presentations

In face presentation, the baby's neck arches back so that the face presents first rather than the top of the head.

In brow presentation, the neck is moderately arched so that the brow presents first.

Usually, fetuses do not stay in a face or brow presentation. These presentations often change to a vertex (top of the head) presentation before or during labor. If they do not, a cesarean delivery is usually recommended.

In transverse lie, the fetus lies horizontally across the birth canal and presents shoulder first. A cesarean delivery is done, unless the fetus is the second in a set of twins. In such a case, the fetus may be turned to be delivered through the vagina.

- Cookie Preferences

Copyright © 2024 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.

- MSD careers

Fetal Presentation, Position, and Lie (Including Breech Presentation)

- Key Points |

Abnormal fetal lie or presentation may occur due to fetal size, fetal anomalies, uterine structural abnormalities, multiple gestation, or other factors. Diagnosis is by examination or ultrasonography. Management is with physical maneuvers to reposition the fetus, operative vaginal delivery , or cesarean delivery .

Terms that describe the fetus in relation to the uterus, cervix, and maternal pelvis are

Fetal presentation: Fetal part that overlies the maternal pelvic inlet; vertex (cephalic), face, brow, breech, shoulder, funic (umbilical cord), or compound (more than one part, eg, shoulder and hand)

Fetal position: Relation of the presenting part to an anatomic axis; for transverse presentation, occiput anterior, occiput posterior, occiput transverse

Fetal lie: Relation of the fetus to the long axis of the uterus; longitudinal, oblique, or transverse

Normal fetal lie is longitudinal, normal presentation is vertex, and occiput anterior is the most common position.

Abnormal fetal lie, presentation, or position may occur with

Fetopelvic disproportion (fetus too large for the pelvic inlet)

Fetal congenital anomalies

Uterine structural abnormalities (eg, fibroids, synechiae)

Multiple gestation

Several common types of abnormal lie or presentation are discussed here.

Transverse lie

Fetal position is transverse, with the fetal long axis oblique or perpendicular rather than parallel to the maternal long axis. Transverse lie is often accompanied by shoulder presentation, which requires cesarean delivery.

Breech presentation

There are several types of breech presentation.

Frank breech: The fetal hips are flexed, and the knees extended (pike position).

Complete breech: The fetus seems to be sitting with hips and knees flexed.

Single or double footling presentation: One or both legs are completely extended and present before the buttocks.

Types of breech presentations

Breech presentation makes delivery difficult ,primarily because the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge. Having a poor dilating wedge can lead to incomplete cervical dilation, because the presenting part is narrower than the head that follows. The head, which is the part with the largest diameter, can then be trapped during delivery.

Additionally, the trapped fetal head can compress the umbilical cord if the fetal umbilicus is visible at the introitus, particularly in primiparas whose pelvic tissues have not been dilated by previous deliveries. Umbilical cord compression may cause fetal hypoxemia.

Predisposing factors for breech presentation include

Preterm labor

Uterine abnormalities

Fetal anomalies

If delivery is vaginal, breech presentation may increase risk of

Umbilical cord prolapse

Birth trauma

Perinatal death

Face or brow presentation

In face presentation, the head is hyperextended, and position is designated by the position of the chin (mentum). When the chin is posterior, the head is less likely to rotate and less likely to deliver vaginally, necessitating cesarean delivery.

Brow presentation usually converts spontaneously to vertex or face presentation.

Occiput posterior position

The most common abnormal position is occiput posterior.

The fetal neck is usually somewhat deflexed; thus, a larger diameter of the head must pass through the pelvis.

Progress may arrest in the second phase of labor. Operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery is often required.

Position and Presentation of the Fetus

If a fetus is in the occiput posterior position, operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery is often required.

In breech presentation, the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge, which can cause the head to be trapped during delivery, often compressing the umbilical cord.

For breech presentation, usually do cesarean delivery at 39 weeks or during labor, but external cephalic version is sometimes successful before labor, usually at 37 or 38 weeks.

- Cookie Preferences

Copyright © 2024 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

What Is Breech?

When a fetus is delivered buttocks or feet first

- Types of Presentation

Risk Factors

Complications.

Breech concerns the position of the fetus before labor . Typically, the fetus comes out headfirst, but in a breech delivery, the buttocks or feet come out first. This type of delivery is risky for both the pregnant person and the fetus.

This article discusses the different types of breech presentations, risk factors that might make a breech presentation more likely, treatment options, and complications associated with a breech delivery.

Verywell / Jessica Olah

Types of Breech Presentation

During the last few weeks of pregnancy, a fetus usually rotates so that the head is positioned downward to come out of the vagina first. This is called the vertex position.

In a breech presentation, the fetus does not turn to lie in the correct position. Instead, the fetus’s buttocks or feet are positioned to come out of the vagina first.

At 28 weeks of gestation, approximately 20% of fetuses are in a breech position. However, the majority of these rotate to the proper vertex position. At full term, around 3%–4% of births are breech.

The different types of breech presentations include:

- Complete : The fetus’s knees are bent, and the buttocks are presenting first.

- Frank : The fetus’s legs are stretched upward toward the head, and the buttocks are presenting first.

- Footling : The fetus’s foot is showing first.

Signs of Breech

There are no specific symptoms associated with a breech presentation.

Diagnosing breech before the last few weeks of pregnancy is not helpful, since the fetus is likely to turn to the proper vertex position before 35 weeks gestation.

A healthcare provider may be able to tell which direction the fetus is facing by touching a pregnant person’s abdomen. However, an ultrasound examination is the best way to determine how the fetus is lying in the uterus.

Most breech presentations are not related to any specific risk factor. However, certain circumstances can increase the risk for breech presentation.

These can include:

- Previous pregnancies

- Multiple fetuses in the uterus

- An abnormally shaped uterus

- Uterine fibroids , which are noncancerous growths of the uterus that usually appear during the childbearing years

- Placenta previa, a condition in which the placenta covers the opening to the uterus

- Preterm labor or prematurity of the fetus

- Too much or too little amniotic fluid (the liquid that surrounds the fetus during pregnancy)

- Fetal congenital abnormalities

Most fetuses that are breech are born by cesarean delivery (cesarean section or C-section), a surgical procedure in which the baby is born through an incision in the pregnant person’s abdomen.

In rare instances, a healthcare provider may plan a vaginal birth of a breech fetus. However, there are more risks associated with this type of delivery than there are with cesarean delivery.

Before cesarean delivery, a healthcare provider might utilize the external cephalic version (ECV) procedure to turn the fetus so that the head is down and in the vertex position. This procedure involves pushing on the pregnant person’s belly to turn the fetus while viewing the maneuvers on an ultrasound. This can be an uncomfortable procedure, and it is usually done around 37 weeks gestation.

ECV reduces the risks associated with having a cesarean delivery. It is successful approximately 40%–60% of the time. The procedure cannot be done once a pregnant person is in active labor.

Complications related to ECV are low and include the placenta tearing away from the uterine lining, changes in the fetus’s heart rate, and preterm labor.

ECV is usually not recommended if the:

- Pregnant person is carrying more than one fetus

- Placenta is in the wrong place

- Healthcare provider has concerns about the health of the fetus

- Pregnant person has specific abnormalities of the reproductive system

Recommendations for Previous C-Sections

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) says that ECV can be considered if a person has had a previous cesarean delivery.

During a breech delivery, the umbilical cord might come out first and be pinched by the exiting fetus. This is called cord prolapse and puts the fetus at risk for decreased oxygen and blood flow. There’s also a risk that the fetus’s head or shoulders will get stuck inside the mother’s pelvis, leading to suffocation.

Complications associated with cesarean delivery include infection, bleeding, injury to other internal organs, and problems with future pregnancies.

A healthcare provider needs to weigh the risks and benefits of ECV, delivering a breech fetus vaginally, and cesarean delivery.

In a breech delivery, the fetus comes out buttocks or feet first rather than headfirst (vertex), the preferred and usual method. This type of delivery can be more dangerous than a vertex delivery and lead to complications. If your baby is in breech, your healthcare provider will likely recommend a C-section.

A Word From Verywell

Knowing that your baby is in the wrong position and that you may be facing a breech delivery can be extremely stressful. However, most fetuses turn to have their head down before a person goes into labor. It is not a cause for concern if your fetus is breech before 36 weeks. It is common for the fetus to move around in many different positions before that time.

At the end of your pregnancy, if your fetus is in a breech position, your healthcare provider can perform maneuvers to turn the fetus around. If these maneuvers are unsuccessful or not appropriate for your situation, cesarean delivery is most often recommended. Discussing all of these options in advance can help you feel prepared should you be faced with a breech delivery.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. If your baby is breech .

TeachMeObGyn. Breech presentation .

MedlinePlus. Breech birth .

Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R, West HM. External cephalic version for breech presentation at term . Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2015 Apr 1;2015(4):CD000083. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000083.pub3

By Christine Zink, MD Dr. Zink is a board-certified emergency medicine physician with expertise in the wilderness and global medicine.

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 25: Breech Presentation

Jessica Dy; Darine El-Chaar

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

General considerations.

- CLASSIFICATION

- RIGHT SACRUM ANTERIOR

- MECHANISMS OF LABOR: BREECH PRESENTATIONS

- PROGNOSIS: BREECH PRESENTATIONS

- INVESTIGATION OF BREECH PRESENTATION AT TERM

- MANAGEMENT OF BREECH PRESENTATION DURING LATE PREGNANCY

- MANAGEMENT OF DELIVERY OF BREECH PRESENTATION

- ARREST IN BREECH PRESENTATION

- BREECH EXTRACTION

- HYPEREXTENSION OF THE FETAL HEAD

- SELECTED READING

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Breech presentation is a longitudinal lie with a variation in polarity. The fetal pelvis is the leading pole. The denominator is the sacrum. A right sacrum anterior (RSA) is a breech presentation where the fetal sacrum is in the right anterior quadrant of the mother's pelvis and the bitrochanteric diameter of the fetus is in the right oblique diameter of the pelvis ( Fig. 25-1 ).

FIGURE 25-1.

Positions of breech presentation. LSA, left sacrum anterior; LSP, left sacrum posterior; LST, left sacrum transverse; RSA, right sacrum anterior; RSP, right sacrum posterior; RST, right sacrum transverse.

Breech presentation at delivery occurs in 3 to 4 percent of pregnancies. However, before 28 weeks of gestation, the incidence is about 25 percent. As term gestation approaches, the incidence decreases. In most cases, the fetus converts to the cephalic presentation by 34 weeks of gestation.

As term approaches, the uterine cavity, in most cases, accommodates the fetus best in a longitudinal lie with a cephalic presentation. In many cases of breech presentation, no reason for the malpresentation can be found and, by exclusion, the cause is ascribed to chance. Some women deliver all their children as breeches, suggesting that the pelvis is so shaped that the breech fits better than the head.

Breech presentation is more common at the end of the second trimester than near term; hence, fetal prematurity is associated frequently with this presentation.

Maternal Factors

Factors that influence the occurrence of breech presentation include (1) the uterine relaxation associated with high parity; (2) polyhydramnios, in which the excessive amount of amniotic fluid makes it easier for the fetus to change position; (3) oligohydramnios, in which, because of the small amount of fluid, the fetus is trapped in the position assumed in the second trimester; (4) uterine anomalies; (5) neoplasms, such as leiomyomata of the myometrium; (6) while contracted pelvis is an uncommon cause of breech presentation, anything that interferes with the entry of the fetal head into the pelvis may play a part in the etiology of breech presentation.

Placental Factors

Placental site: There is some evidence that implantation of the placenta in either cornual-fundal region tends to promote breech presentation. There is a positive association of breech with placenta previa.

Fetal Factors

Fetal factors that influence the occurrence of breech presentation include multiple pregnancy, hydrocephaly, anencephaly, chromosomal anomalies, and intrauterine fetal death.

Notes and Comments

The patient commonly feels fetal movements in the lower abdomen and may complain of painful kicking against the rectum, vagina, and bladder

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Pregnancy week by week

- Fetal presentation before birth

The way a baby is positioned in the uterus just before birth can have a big effect on labor and delivery. This positioning is called fetal presentation.

Babies twist, stretch and tumble quite a bit during pregnancy. Before labor starts, however, they usually come to rest in a way that allows them to be delivered through the birth canal headfirst. This position is called cephalic presentation. But there are other ways a baby may settle just before labor begins.

Following are some of the possible ways a baby may be positioned at the end of pregnancy.

Head down, face down

When a baby is head down, face down, the medical term for it is the cephalic occiput anterior position. This the most common position for a baby to be born in. With the face down and turned slightly to the side, the smallest part of the baby's head leads the way through the birth canal. It is the easiest way for a baby to be born.

Head down, face up

When a baby is head down, face up, the medical term for it is the cephalic occiput posterior position. In this position, it might be harder for a baby's head to go under the pubic bone during delivery. That can make labor take longer.

Most babies who begin labor in this position eventually turn to be face down. If that doesn't happen, and the second stage of labor is taking a long time, a member of the health care team may reach through the vagina to help the baby turn. This is called manual rotation.

In some cases, a baby can be born in the head-down, face-up position. Use of forceps or a vacuum device to help with delivery is more common when a baby is in this position than in the head-down, face-down position. In some cases, a C-section delivery may be needed.

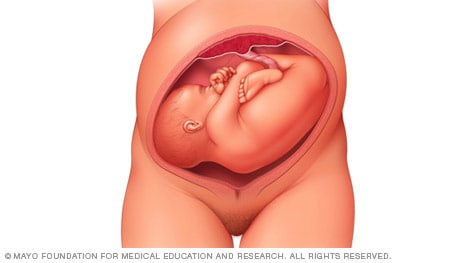

Frank breech

When a baby's feet or buttocks are in place to come out first during birth, it's called a breech presentation. This happens in about 3% to 4% of babies close to the time of birth. The baby shown below is in a frank breech presentation. That's when the knees aren't bent, and the feet are close to the baby's head. This is the most common type of breech presentation.

If you are more than 36 weeks into your pregnancy and your baby is in a frank breech presentation, your health care professional may try to move the baby into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. It involves one or two members of the health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

If the procedure isn't successful, or if the baby moves back into a breech position, talk with a member of your health care team about the choices you have for delivery. Most babies in a frank breech position are born by planned C-section.

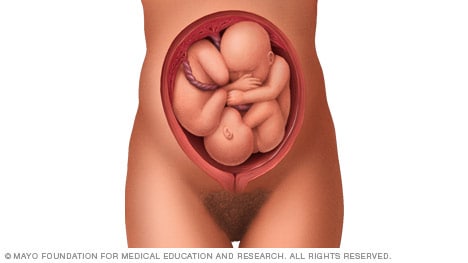

Complete and incomplete breech

A complete breech presentation, as shown below, is when the baby has both knees bent and both legs pulled close to the body. In an incomplete breech, one or both of the legs are not pulled close to the body, and one or both of the feet or knees are below the baby's buttocks. If a baby is in either of these positions, you might feel kicking in the lower part of your belly.

If you are more than 36 weeks into your pregnancy and your baby is in a complete or incomplete breech presentation, your health care professional may try to move the baby into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. It involves one or two members of the health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

If the procedure isn't successful, or if the baby moves back into a breech position, talk with a member of your health care team about the choices you have for delivery. Many babies in a complete or incomplete breech position are born by planned C-section.

When a baby is sideways — lying horizontal across the uterus, rather than vertical — it's called a transverse lie. In this position, the baby's back might be:

- Down, with the back facing the birth canal.

- Sideways, with one shoulder pointing toward the birth canal.

- Up, with the hands and feet facing the birth canal.

Although many babies are sideways early in pregnancy, few stay this way when labor begins.

If your baby is in a transverse lie during week 37 of your pregnancy, your health care professional may try to move the baby into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. External cephalic version involves one or two members of your health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

If the procedure isn't successful, or if the baby moves back into a transverse lie, talk with a member of your health care team about the choices you have for delivery. Many babies who are in a transverse lie are born by C-section.

If you're pregnant with twins and only the twin that's lower in the uterus is head down, as shown below, your health care provider may first deliver that baby vaginally.

Then, in some cases, your health care team may suggest delivering the second twin in the breech position. Or they may try to move the second twin into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. External cephalic version involves one or two members of the health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

Your health care team may suggest delivery by C-section for the second twin if:

- An attempt to deliver the baby in the breech position is not successful.

- You do not want to try to have the baby delivered vaginally in the breech position.

- An attempt to move the baby into a head-down position is not successful.

- You do not want to try to move the baby to a head-down position.

In some cases, your health care team may advise that you have both twins delivered by C-section. That might happen if the lower twin is not head down, the second twin has low or high birth weight as compared to the first twin, or if preterm labor starts.

- Landon MB, et al., eds. Normal labor and delivery. In: Gabbe's Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed May 19, 2023.

- Holcroft Argani C, et al. Occiput posterior position. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 19, 2023.

- Frequently asked questions: If your baby is breech. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/if-your-baby-is-breech. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Hofmeyr GJ. Overview of breech presentation. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Strauss RA, et al. Transverse fetal lie. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Chasen ST, et al. Twin pregnancy: Labor and delivery. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Cohen R, et al. Is vaginal delivery of a breech second twin safe? A comparison between delivery of vertex and non-vertex second twins. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2021; doi:10.1080/14767058.2021.2005569.

- Marnach ML (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. May 31, 2023.

Products and Services

- A Book: Obstetricks

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy

- 3rd trimester pregnancy

- Fetal development: The 3rd trimester

- Overdue pregnancy

- Pregnancy due date calculator

- Prenatal care: 3rd trimester

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Management of Breech Presentation (Green-top Guideline No. 20b)

Summary: The aim of this guideline is to aid decision making regarding the route of delivery and choice of various techniques used during delivery. It does not include antenatal or postnatal care. Information regarding external cephalic version is the topic of the separate Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Green-top Guideline No. 20a, External Cephalic Version and Reducing the Incidence of Term Breech Presentation .

Breech presentation occurs in 3–4% of term deliveries and is more common in preterm deliveries and nulliparous women. Breech presentation is associated with uterine and congenital abnormalities, and has a significant recurrence risk. Term babies presenting by the breech have worse outcomes than cephalic presenting babies, irrespective of the mode of delivery.

A large reduction in the incidence of planned vaginal breech birth followed publication of the Term Breech Trial. Nevertheless, due to various circumstances vaginal breech births will continue. Lack of experience has led to a loss of skills essential for these deliveries. Conversely, caesarean section can has serious long-term consequences.

COVID disclaimer: This guideline was developed as part of the regular updates to programme of Green-top Guidelines, as outlined in our document Developing a Green-top Guideline: Guidance for developers , and prior to the emergence of COVID-19.

Version history: This is the fourth edition of this guideline.

Please note that the RCOG Guidelines Committee regularly assesses the need to update the information provided in this publication. Further information on this review is available on request.

Developer declaration of interests:

Mr M Griffiths is a member of Doctors for a Woman's right to Choose on Abortion. He is an unpaid member of a Quality Standards Advisory Committee at NICE, for which he does receive expenses for related travel, accommodation and meals.

Mr LWM Impey is Director of Oxford Fetal Medicine Ltd. and a member of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. He also holds patents related to ultrasound processing, which are of no relevance to the Breech guidelines.

Professor DJ Murphy provides medicolegal expert opinions in Scotland and Ireland for which she is remunerated.

Dr LK Penna: None declared.

- Access the PDF version of this guideline on Wiley

- Access the web version of this guideline on Wiley

This page was last reviewed 16 March 2017.

Fetal Presentation, Position, and Lie (Including Breech Presentation)

- Key Points |

Abnormal fetal lie or presentation may occur due to fetal size, fetal anomalies, uterine structural abnormalities, multiple gestation, or other factors. Diagnosis is by examination or ultrasonography. Management is with physical maneuvers to reposition the fetus, operative vaginal delivery , or cesarean delivery .

Terms that describe the fetus in relation to the uterus, cervix, and maternal pelvis are

Fetal presentation: Fetal part that overlies the maternal pelvic inlet; vertex (cephalic), face, brow, breech, shoulder, funic (umbilical cord), or compound (more than one part, eg, shoulder and hand)

Fetal position: Relation of the presenting part to an anatomic axis; for transverse presentation, occiput anterior, occiput posterior, occiput transverse

Fetal lie: Relation of the fetus to the long axis of the uterus; longitudinal, oblique, or transverse

Normal fetal lie is longitudinal, normal presentation is vertex, and occiput anterior is the most common position.

Abnormal fetal lie, presentation, or position may occur with

Fetopelvic disproportion (fetus too large for the pelvic inlet)

Fetal congenital anomalies

Uterine structural abnormalities (eg, fibroids, synechiae)

Multiple gestation

Several common types of abnormal lie or presentation are discussed here.

Transverse lie

Fetal position is transverse, with the fetal long axis oblique or perpendicular rather than parallel to the maternal long axis. Transverse lie is often accompanied by shoulder presentation, which requires cesarean delivery.

Breech presentation

There are several types of breech presentation.

Frank breech: The fetal hips are flexed, and the knees extended (pike position).

Complete breech: The fetus seems to be sitting with hips and knees flexed.

Single or double footling presentation: One or both legs are completely extended and present before the buttocks.

Types of breech presentations

Breech presentation makes delivery difficult ,primarily because the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge. Having a poor dilating wedge can lead to incomplete cervical dilation, because the presenting part is narrower than the head that follows. The head, which is the part with the largest diameter, can then be trapped during delivery.

Additionally, the trapped fetal head can compress the umbilical cord if the fetal umbilicus is visible at the introitus, particularly in primiparas whose pelvic tissues have not been dilated by previous deliveries. Umbilical cord compression may cause fetal hypoxemia.

Predisposing factors for breech presentation include

Preterm labor

Uterine abnormalities

Fetal anomalies

If delivery is vaginal, breech presentation may increase risk of

Umbilical cord prolapse

Birth trauma

Perinatal death

Face or brow presentation

In face presentation, the head is hyperextended, and position is designated by the position of the chin (mentum). When the chin is posterior, the head is less likely to rotate and less likely to deliver vaginally, necessitating cesarean delivery.

Brow presentation usually converts spontaneously to vertex or face presentation.

Occiput posterior position

The most common abnormal position is occiput posterior.

The fetal neck is usually somewhat deflexed; thus, a larger diameter of the head must pass through the pelvis.

Progress may arrest in the second phase of labor. Operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery is often required.

Position and Presentation of the Fetus

If a fetus is in the occiput posterior position, operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery is often required.

In breech presentation, the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge, which can cause the head to be trapped during delivery, often compressing the umbilical cord.

For breech presentation, usually do cesarean delivery at 39 weeks or during labor, but external cephalic version is sometimes successful before labor, usually at 37 or 38 weeks.

Copyright © 2024 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.

- Cookie Preferences

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

A comparison of risk factors for breech presentation in preterm and term labor: a nationwide, population-based case–control study

Anna e. toijonen.

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Hospital (HUS), University of Helsinki, Haartmaninkatu 2, 00290 Helsinki, Finland

3 School of Medicine, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

Seppo T. Heinonen

Mika v. m. gissler.

2 National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL), Helsinki, Finland

Georg Macharey

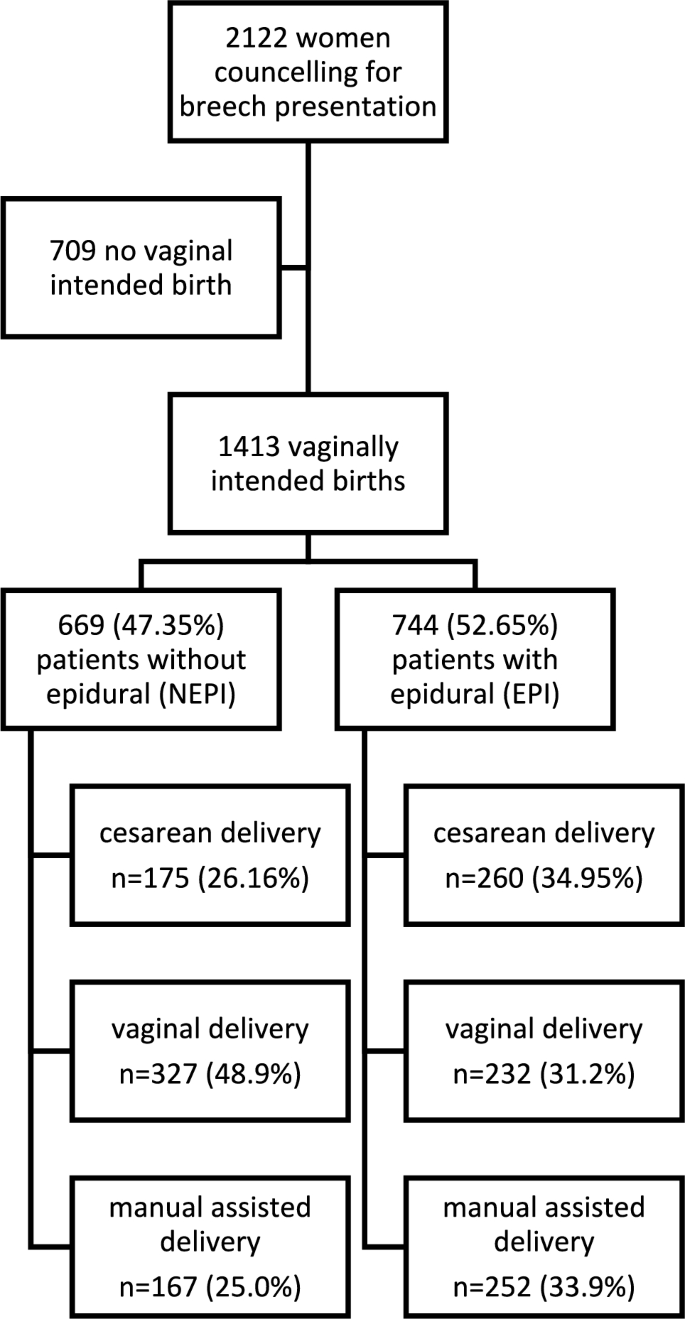

To determine if the common risks for breech presentation at term labor are also eligible in preterm labor.

A Finnish cross-sectional study included 737,788 singleton births (24–42 gestational weeks) during 2004–2014. A multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to calculate the risks of breech presentation.

The incidence of breech presentation at delivery decreased from 23.5% in pregnancy weeks 24–27 to 2.5% in term pregnancies. In gestational weeks 24–27, preterm premature rupture of membranes was associated with breech presentation. In 28–31 gestational weeks, breech presentation was associated with maternal pre-eclampsia/hypertension, preterm premature rupture of membranes, and fetal birth weight below the tenth percentile. In gestational weeks 32–36, the risks were advanced maternal age, nulliparity, previous cesarean section, preterm premature rupture of membranes, oligohydramnios, birth weight below the tenth percentile, female sex, and congenital anomaly. In term pregnancies, breech presentation was associated with advanced maternal age, nulliparity, maternal hypothyroidism, pre-gestational diabetes, placenta praevia, premature rupture of membranes, oligohydramnios, congenital anomaly, female sex, and birth weight below the tenth percentile.

Breech presentation in preterm labor is associated with obstetric risk factors compared to cephalic presentation. These risks decrease linearly with the gestational age. In moderate to late preterm delivery, breech presentation is a high-risk state and some obstetric risk factors are yet visible in early preterm delivery. Breech presentation in extremely preterm deliveries has, with the exception of preterm premature rupture of membranes, similar clinical risk profiles as in cephalic presentation.

Introduction

The prevalence of breech presentation at delivery decreases with increasing gestational age. At 28 pregnancy weeks, every fifth fetus lies in the breech presentation and in term pregnancies, less than 4% of all singleton fetuses are in breech presentation at delivery [ 1 , 2 ]. Most likely this is due to a lack of fetal movements [ 3 ] or an incomplete fetal rotation, since the possibility of a spontaneous rotation declines with increasing gestational age. Consequently, preterm labor itself is often associated with breech presentation at delivery, since the fetus was not yet able to rotate [ 4 – 9 ]. This fact makes preterm labor as one of the strongest risk factors for breech presentation.

Vaginal breech delivery in term pregnancies is not only associated with poorer perinatal outcomes compared to vaginal delivery with a fetus in cephalic presentation [ 6 , 10 , 11 ], but also it is debated whether the cause of breech presentation itself is a risk for adverse peri- and neonatal outcomes [ 3 , 12 , 13 ]. Several fetal and maternal features, such as fetal growth restriction, congenital anomaly, oligohydramnios, gestational diabetes, and previous cesarean section, are linked to a higher risk of breech presentation at term, and, furthermore, are associated with an increased risk for adverse perinatal outcomes [ 3 – 5 , 8 , 9 , 14 – 17 ].

The literature lacks studies on the risk factors of breech presentation in preterm pregnancies. It remains unclear whether breech presentation at preterm labor is only caused by the incomplete fetal rotation, or whether breech presentation in preterm labor is also associated with other obstetric risk factors. Most of the studies reviewing risk factors for breech presentation focus on term pregnancies. Our hypothesis is that breech presentation in preterm deliveries is, besides preterm pregnancy itself, associated with other risk factors similar to breech presentation at term. We aim to compare the risks of preterm breech presentation to those in cephalic presentation by gestational age. Such information would be valuable in the risk stratification of breech deliveries by gestational age.

Materials and methods

We conducted a retrospective population-based cross-sectional study. The population included all the singleton preterm and term births, from January 2004 to December 2014 in Finland. The data were collected from the national medical birth register and the hospital discharge register, maintained by the National Institute for Health and Welfare. All Finnish maternity hospitals are obligated to contribute clinical data on births from 22 weeks or birth weight of 500 g to the register. All newborn infants are examined by a pediatrician and given a personal identification number that can be traced in the case of perinatal mortality or morbidity. The hospital discharge register contains information on all surgical procedures and diagnoses (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision, ICD-10) in all inpatient care and outpatient care in public hospitals.

Authorization to use the data was obtained from the National Institute for Health and Welfare as required by the national data protection law in Finland (reference number THL/652/5.05.00/2017).

The study population included all the women with a singleton fetus in breech presentation at the time of delivery. The control group included all the women with a singleton fetus in cephalic presentation at delivery. Other presentations were excluded from the study ( N = 1671) (Fig. 1 ). Gestational age was determined according to early ultrasonographic measurement which is routinely performed in Finland and it encompasses over 95% of the mothers, or if not available, to the last menstrual period. We excluded neonates delivered before 24 weeks of gestation and birth weight of less than 500 g, because the lower viability may have influenced the mode of the delivery or the outcome. The study population was divided into four categories according to the World Health Organization (WHO) definitions of preterm and term deliveries. WHO defines preterm birth as a fetus born alive before 37 completed weeks of pregnancy. WHO recommends sub-categories of preterm birth, based on gestational age, as extremely preterm (less than 28 pregnancy weeks), very preterm (28–32 pregnancy weeks), and moderate to late preterm (32–37 pregnancy weeks).

Breech presentation for singleton pregnancies during the period of 2004–2014 in Finland

In our study, we assessed four factors that may be associated with breech presentation based on prior reports [ 3 – 5 , 14 , 17 – 20 ]. These factors were: maternal age below 25 and 35 years or more, smoking, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) over 30, and in vitro fertilization. The following factors were also analyzed: nulliparity, more than three previous deliveries, and history of cesarean section. The obstetric risk factors including maternal hypo- or hyperthyroidism (ICD-10 E03, E05), gestational diabetes (ICD-10 O24.4) and other diabetes treated with insulin (ICD-10 O24.0), arterial hypertension or pre-eclampsia (ICD-10 O13, O14), and maternal care for (suspected) damage to fetus by alcohol or drugs (ICD-10 O35.4, O35.5) were assessed in the analysis. The variables that were also included in the analysis were: oligohydramnios (ICD-10 O41.0), placenta praevia (ICD-10 O44), placental abruption (ICD-10 O45), preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) (ICD-10 O42), infant sex, fetal birth weight below the tenth percentile, fetuses with birth weight above the 97th percentile, and fetal congenital anomalies as defined in the register of congenital malformations.

The babies born in breech presentation from the four study groups were compared with the babies born in cephalic presentation with the equal gestational age, according to WHO classification. The calculations were performed using SPSS 19. Statistical differences in categorical variables were evaluated with the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. We calculated odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using binary logistic regression. Each study group was separately adjusted, according to gestational age at delivery, defined by WHO. The adjustment for the risk factors was done by multivariable logistic regression model for all variables. Differences were deemed to be statistically significant with P value < 0.05.

This analysis includes 737,788 singleton births, from these 20,086 were in breech presentation at the time of delivery. Out of all deliveries, 33,489 infants were born preterm. The prevalence of breech presentation at delivery decreased with the increase of the gestational age: 23.5% in extremely preterm delivery, 15.4% very preterm deliveries, and 6.7% in moderate to late preterm deliveries. At term, the prevalence of breech presentation at delivery was 2.5% (Fig. 1 ).

From all deliveries, 2056 fetuses were born extremely preterm (24 + 0 to 27 + 6 gestational weeks). The differences in the possible risk factors for breech presentation at delivery were higher odds of PPROM (aOR 1.39, 95% CI 1.08–1.79, P = 0.010) and a lower risk of placental abruption (aOR 0.59, 95% CI 0.36–0.98, P = 0.040). No statistically significant differences were observed for the other factors (Table (Table1, 1 , Figs. 1 , ,2, 2 , ,3, 3 , ,4 4 ).

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for risk factors in singleton extremely preterm 24 + 0 to 27 + 6 weeks of gestational age fetuses in breech and in cephalic presentations during 2004–2014 in Finland

BMI body mass index, IVF in vitro fertilization, maternal intoxication, PPROM preterm premature rupture of membranes

Prevalence of obstetric risk factors for breech presentation compared to cephalic by gestational age. PPROM preterm premature rupture of membranes, PROM premature rupture of membranes

Obstetric risk factors for breech presentation with adjusted odds ratios by gestational age. PPROM preterm premature rupture of membranes, PROM premature rupture of membranes, aOR adjusted odds ratio

The determinants of breech presentation by gestational age. PPROM preterm premature rupture of membranes, PROM premature rupture of membranes

The group of very preterm deliveries (28 + 0 to 31 + 6 gestational weeks) included 4582 singleton newborns. Breech presentation at delivery was associated with PPROM (aOR 1.61, 95% CI 1.32–1.96, P < 0.001), oligohydramnios (aOR 1.65, 95% CI 1.03–2.64, P = 0.038), fetal birth weight below the tenth percentile (aOR 1.57, 95% CI 1.19–2.08, P = 0.002), and maternal pre-eclampsia and arterial hypertension (aOR 1.31, 95% CI 1.04–1.66, P = 0.023). Details of risk factors in very preterm breech deliveries are described in Table Table2. 2 . The risk of placenta praevia as well as having a birth weight above the 97th percentile was lower in pregnancies with fetuses in breech rather than in cephalic presentation (Table (Table2, 2 , Figs. Figs.2, 2 , ,3, 3 , ,4 4 ).

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for risk factors in singleton very preterm 28 + 0 to 31 + 6 weeks of gestational age fetuses in breech and in cephalic presentations during 2004–2014 in Finland

BMI body mass index, IVF in vitro fertilization, PPROM preterm premature rupture of membranes

The moderate to late preterm delivery group (32 + 0 to 36 + 6 gestational weeks) included 26,851 deliveries. Breech presentation in moderate to late preterm deliveries was associated with older maternal age (maternal age 35 years or more aOR 1.24, 95% CI 1.10–1.39, P < 0.001), nullipara (aOR 1.43, 95% CI 1.27–1.60, P < 0.001), maternal BMI less than 25 (maternal BMI ≥ 25 aOR 0.75, 95% CI 0.62–0.91, P = 0.004), previous cesarean section (aOR 1.31, 95% CI 1.12–1.53, P < 0.001), female sex (aOR 1.22, 95% CI 1.11–1.34, P < 0.001), congenital anomaly (aOR 1.37, 95% CI 1.22–1.55, P < 0.001), fetal birth weight below the tenth percentile (aOR 1.31, 95% CI 1.10–1.56, P = 0.003), oligohydramnios (aOR 3.60, 95% CI 2.63–4.92, P < 0.001), and PPROM (aOR 1.58, 95% CI 1.41–1.78, P < 0.001). Breech presentation decreased the odds of having a fetus with birth weight above the 97th percentile (aOR 0.60, 95% CI 0.42–0.85, P = 0.004) (Table (Table3, 3 , Figs. Figs.2, 2 , ,3, 3 , ,4 4 ).

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for risk factors in singleton moderate to late preterm 32 + 0 to 36 + 6 weeks of gestational age fetuses in breech and in cephalic presentations during 2004–2014 in Finland

The term and post-term group included 704,299 deliveries, among them 17,044 fetuses in breech presentation. The factors associated with breech presentation amongst these were: maternal age of 35 years or more (aOR 1.24, 95% CI 1.19–1.29, P < 0.001), nullipara (aOR 2.46, 95% CI 2.37–2.55, P < 0.001), maternal BMI less than 25 (BMI ≥ 25 aOR 0.90, 95% CI 0.85–0.96, P < 0.001), maternal hypothyroidism (aOR 1.53, 95% CI 1.28–1.82, P < 0.001), pre-gestational diabetes treated with insulin (aOR 1.24, 95% CI 1.00–1.53, P = 0.049), placenta praevia (aOR 1.45, 95% CI 1.11–1.91, P = 0.007), premature rupture of membranes (PROM) (aOR 1.58, 95% CI 1.45–1.72, P < 0.001), oligohydramnios (aOR 2.02, 95% CI 1.83–2.22, P < 0.001), congenital anomaly (aOR 1.97, 95% CI 1.89–2.06, P < 0.001), female sex (aOR 1.28, 95% CI 1.24–1.32, P < 0.001), and birth weight below the tenth percentile (aOR 1.18, 95% CI 1.12–1.24, P < 0.001) Table Table4 4 includes details for risk factors of term and post-term group (Figs. 2 , ,3, 3 , ,4 4 ).

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for risk factors in singleton term pregnancies in breech and in cephalic presentations during 2004–2014 in Finland

BMI body mass index, IVF in vitro fertilization, PROM premature rupture of membranes

The main novel finding of our study was that the risk associations increase with each gestational age group after 28 weeks of gestation. With the exception of PPROM, the extremely preterm breech deliveries have similar clinical risk profiles as in cephalic presentation when matched for gestational age. However, as gestation proceeds, the risks start to cluster. In moderate to late preterm pregnancies as in term pregnancies, the breech presentation is a high-risk state being associated with several risk factors: PPROM, oligohydramnios, advanced maternal age, nulliparity, previous cesarean section, fetal birth weight below the tenth percentile, female sex, and fetal congenital anomalies. These are in line with the findings of previous studies [ 3 , 5 , 7 , 8 ], that associated breech presentation at term with obstetric risk factors. The prevalence of breech presentation was negatively correlated with the gestational age with a decline from 23.5% in extremely preterm pregnancies to 2.5% at term. The prevalence of breech presentation in preterm pregnancies observed in our trial is similar to that of comparable studies [ 1 , 2 ].

In extremely preterm deliveries, PPROM was the only risk factor for breech presentation and it stayed as a risk for breech presentation through the gestational weeks. This finding is comparable to the previous literature suggesting that PPROM occurs more often at earlier gestational age in pregnancies with the fetus in breech presentation compared with cephalic [ 21 , 22 ]. PPROM might prevent the fetus to change into cephalic presentation. Furthermore, Goodman and colleagues (2013) reported that in pregnancies with a fetus in a presentation other than cephalic had more complications such as oligohydramnios, infections, placental abruption, and even stillbirths. In our study, surprisingly, placental abruption seemed to have a negative correlation with breech presentation among extremely preterm deliveries. This inconsistency between our results and the literature might be due to the small number of cases. Many of the obstetric complications, for example gestational diabetes, late pre-eclampsia, and late intrauterine growth restriction develop during the second or the third trimester of the pregnancy which explains partially why the risk factors for breech presentation are rarer in extremely preterm deliveries.

In very preterm delivery, breech presentation was associated with PPROM, pre-eclampsia, and fetal birth weight below the tenth percentile. Fetal growth restriction is a known risk factor for breech presentation at term, since it is associated with reduced fetal movements due to diminished resources [ 23 – 25 ]. Furthermore, fetal growth restriction is known to be the single largest factor for stillbirth and neonatal mortality [ 26 – 30 ]. Maternal arterial hypertension disturbs placental function which might cause low birth weight [ 31 , 32 ]. Arterial hypertension and pre-eclampsia increased the risk for breech presentation in very preterm births, but not in earlier or later preterm pregnancies. This finding may be due to the bias that pre-eclampsia is a well-described risk factor for PPROM, fetal growth restriction, and preterm deliveries which are also independent markers for breech presentation itself [ 4 , 5 , 31 , 33 , 34 ]. The severity of early pre-eclampsia might affect the fetal wellbeing, reduce fetal movements and growth, which might reduce the spontaneous fetal rotation to the cephalic position [ 35 ]. In addition, the most severe cases might not reach older gestational age before the delivery.

The risk factor for breech presentation in moderate to late preterm breech delivery was PPROM, oligohydramnios, advanced maternal age, nulliparity, previous cesarean section, fetal birth weight below the tenth percentile, female sex, and fetal congenital anomalies. Oligohydramnios is a known significant risk factor for term breech pregnancies [ 25 ] and it is linked to the reduced fetal movements partly due to a restricted intrauterine space [ 24 , 35 ] and nuchal cords [ 35 ]. Additionally, oligohydramnios is associated with placental dysfunction, which might reduce fetal resources and thus has a progressive effect on the fetal movements and prevent the fetus from turning into cephalic presentation [ 3 , 4 , 18 ]. Fetal female sex in moderate to late preterm breech pregnancies remained as a risk factor, as identified previously for term pregnancies [ 3 – 5 ]. It has been debated whether this risk is due to a smaller fetal size or that female fetuses tend to move less [ 9 , 20 ]. The mothers of infants born in breech presentation in moderate to late preterm and term and post-term pregnancies seemed to be older and had an increased risk of having a fetus with a congenital anomaly. The advanced maternal age is associated with negative effects on vascular health, which may have an influence on the developing fetus and increase the incidence of congenital anomalies [ 19 , 34 , 36 ]. Furthermore, congenital anomalies may have a negative influence on fetal movements [ 19 , 35 ]. Whereas, the low birth weight was found as a risk for breech presentation, a birth weight above the 97th percentile was, coherently a protective factor for breech presentation in very to term and post-term pregnancies.

We found that in term pregnancies, breech presentation was associated with advanced maternal age, nulliparity, maternal hypothyroidism, pre-gestational diabetes, placenta praevia, PROM, oligohydramnios, fetal congenital anomaly, female sex of the fetus, and birth weight below the tenth percentile. A previous cesarean section is known to be positively related to the odds of having a fetus in breech presentation at term [ 5 , 14 ], and in our study, this risk factor started to show already in moderate to late preterm pregnancies. Instead of the scar being the cause of breech presentation, it is more likely that the women with a history of breech cesarean section have, during subsequent pregnancies, a fetus in breech presentation again or have a cesarean section for another reason [ 3 , 5 , 37 ]. Our data suggest that the advanced maternal age and nulliparity are the risks for breech presentation at term, but as well as in moderate to late preterm pregnancies. The tight wall of the abdomen and the uterus of nulliparous women might inhibit the fetus from rotating to cephalic presentation [ 9 ]. In a meta-analysis from 2017, older maternal age has been considered to increase the risk of placental dysfunction such as pre-eclampsia and preterm birth [ 36 ] that are also common risk factors for breech presentation [ 4 , 5 ]. Bearing the first child in older maternal age and giving birth by cesarean section may affect the decision not to have another child and might explain the higher rate of nulliparity among moderate to late preterm and term deliveries [ 1 ]. Our study found correlation between maternal hypothyroidism and breech presentation at term. Some studies have demonstrated an association between maternal thyroid hypofunction and adverse pregnancy outcomes such as pre-eclampsia and low birth weight which are, furthermore, risks for breech presentation and may explain partly the higher prevalence of maternal hypothyroidism in term breech deliveries [ 38 – 40 ]. However, the absence of screening of, for example, thyroid diseases may cause bias in the diagnoses.

Our study demonstrated that as gestation proceeds, more obstetric risk factors can be found associating with breech presentation. In the earlier gestation and excluding PPROM, breech deliveries did not differ in obstetric risk factors compared to cephalic. The risk factors in 32 weeks of gestational age are comparable to those in term pregnancy, and several of these factors, such as low birth weight, congenital anomalies and history of cesarean section, are associated with adverse fetal outcomes [ 1 , 4 , 5 , 8 , 14 , 17 ] and must be taken into account when treating breech pregnancies. Risk factors should be evaluated prior to offering a patient an external cephalic version, as the presence of some of these risks may increase the change of failed version or fetal intolerance of the procedure. This study had adequate power to show differences between the risk profiles of breech and cephalic presentations in different gestational phase. Further research, however, is needed for improving the identification of patients at risk for preterm breech labor and elucidating the optimal route for delivery in preterm breech pregnancies.

Our study is unique since it is the first study, to our knowledge, that compares the risks for breech presentation in preterm and term deliveries. The analysis is based on a large nationwide population, which is the major strength of our study. The study population included nearly 34,000 preterm births over 11 years in Finland and 737,788 deliveries overall. The medical treatment of pregnancies is homogenous, since there are no private hospitals treating deliveries. A further strength relates to the important information on the characteristics of the mother, for example smoking during pregnancy and pre-pregnancy body mass index. The retrospective approach is a limitation of the study, another one is the design as a record linkage study, due to which the variables were restricted to the data availability. Therefore, we were not able to assess, for example uterine anomalies or previous breech deliveries to the analysis.

Our results show that the factors associated with breech presentation in very late preterm breech deliveries resemble those in term pregnancies. However, breech presentation in extremely preterm breech birth has similar clinical risk profiles as in cephalic presentation.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Helsinki including Helsinki University Central Hospital.

Abbreviations

Author contribution.

AT: Project development, manuscript writing. SH: Project development. MG: Data collection and analysis, manuscript editing. GM: Project development, manuscript editing.

This study was supported by Helsinki University Hospital Research Grants. Authorization to use of the data was obtained from the National Institute for Health and Welfare as required by the national data protection legislation in Finland (reference number THL/652/5.05.00/2017).

Compliance with ethical standards

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

For this type of study, formal consent is not required. The National Institute for Health and Welfare authorized to use the data (reference number THL/652/5.05.00/2017).

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Anna E. Toijonen, Email: [email protected] .

Seppo T. Heinonen, Email: [email protected] .

Mika V. M. Gissler, Email: [email protected] .

Georg Macharey, Email: [email protected] .

- Getting Pregnant

- Registry Builder

- Baby Products

- Birth Clubs

- See all in Community

- Ovulation Calculator

- How To Get Pregnant

- How To Get Pregnant Fast

- Ovulation Discharge

- Implantation Bleeding

- Ovulation Symptoms

- Pregnancy Symptoms

- Am I Pregnant?

- Pregnancy Tests

- See all in Getting Pregnant

- Due Date Calculator

- Pregnancy Week by Week

- Pregnant Sex

- Weight Gain Tracker

- Signs of Labor

- Morning Sickness

- COVID Vaccine and Pregnancy

- Fetal Weight Chart

- Fetal Development

- Pregnancy Discharge

- Find Out Baby Gender

- Chinese Gender Predictor

- See all in Pregnancy

- Baby Name Generator

- Top Baby Names 2023

- Top Baby Names 2024

- How to Pick a Baby Name

- Most Popular Baby Names

- Baby Names by Letter

- Gender Neutral Names

- Unique Boy Names

- Unique Girl Names

- Top baby names by year

- See all in Baby Names

- Baby Development

- Baby Feeding Guide

- Newborn Sleep

- When Babies Roll Over

- First-Year Baby Costs Calculator

- Postpartum Health

- Baby Poop Chart

- See all in Baby

- Average Weight & Height

- Autism Signs

- Child Growth Chart

- Night Terrors

- Moving from Crib to Bed

- Toddler Feeding Guide

- Potty Training

- Bathing and Grooming

- See all in Toddler

- Height Predictor

- Potty Training: Boys

- Potty training: Girls

- How Much Sleep? (Ages 3+)

- Ready for Preschool?

- Thumb-Sucking

- Gross Motor Skills

- Napping (Ages 2 to 3)

- See all in Child

- Photos: Rashes & Skin Conditions

- Symptom Checker

- Vaccine Scheduler

- Reducing a Fever

- Acetaminophen Dosage Chart

- Constipation in Babies

- Ear Infection Symptoms

- Head Lice 101

- See all in Health

- Second Pregnancy

- Daycare Costs

- Family Finance

- Stay-At-Home Parents

- Breastfeeding Positions

- See all in Family

- Baby Sleep Training

- Preparing For Baby

- My Custom Checklist

- My Registries

- Take the Quiz

- Best Baby Products

- Best Breast Pump

- Best Convertible Car Seat

- Best Infant Car Seat

- Best Baby Bottle

- Best Baby Monitor

- Best Stroller

- Best Diapers

- Best Baby Carrier

- Best Diaper Bag

- Best Highchair

- See all in Baby Products

- Why Pregnant Belly Feels Tight

- Early Signs of Twins

- Teas During Pregnancy

- Baby Head Circumference Chart

- How Many Months Pregnant Am I

- What is a Rainbow Baby

- Braxton Hicks Contractions

- HCG Levels By Week

- When to Take a Pregnancy Test

- Am I Pregnant

- Why is Poop Green

- Can Pregnant Women Eat Shrimp

- Insemination

- UTI During Pregnancy

- Vitamin D Drops

- Best Baby Forumla

- Postpartum Depression

- Low Progesterone During Pregnancy

- Baby Shower

- Baby Shower Games

Breech, posterior, transverse lie: What position is my baby in?

Fetal presentation, or how your baby is situated in your womb at birth, is determined by the body part that's positioned to come out first, and it can affect the way you deliver. At the time of delivery, 97 percent of babies are head-down (cephalic presentation). But there are several other possibilities, including feet or bottom first (breech) as well as sideways (transverse lie) and diagonal (oblique lie).

Fetal presentation and position

During the last trimester of your pregnancy, your provider will check your baby's presentation by feeling your belly to locate the head, bottom, and back. If it's unclear, your provider may do an ultrasound or an internal exam to feel what part of the baby is in your pelvis.

Fetal position refers to whether the baby is facing your spine (anterior position) or facing your belly (posterior position). Fetal position can change often: Your baby may be face up at the beginning of labor and face down at delivery.

Here are the many possibilities for fetal presentation and position in the womb.

Medical illustrations by Jonathan Dimes

Head down, facing down (anterior position)

A baby who is head down and facing your spine is in the anterior position. This is the most common fetal presentation and the easiest position for a vaginal delivery.

This position is also known as "occiput anterior" because the back of your baby's skull (occipital bone) is in the front (anterior) of your pelvis.

Head down, facing up (posterior position)

In the posterior position , your baby is head down and facing your belly. You may also hear it called "sunny-side up" because babies who stay in this position are born facing up. But many babies who are facing up during labor rotate to the easier face down (anterior) position before birth.

Posterior position is formally known as "occiput posterior" because the back of your baby's skull (occipital bone) is in the back (posterior) of your pelvis.

Frank breech

In the frank breech presentation, both the baby's legs are extended so that the feet are up near the face. This is the most common type of breech presentation. Breech babies are difficult to deliver vaginally, so most arrive by c-section .

Some providers will attempt to turn your baby manually to the head down position by applying pressure to your belly. This is called an external cephalic version , and it has a 58 percent success rate for turning breech babies. For more information, see our article on breech birth .

Complete breech

A complete breech is when your baby is bottom down with hips and knees bent in a tuck or cross-legged position. If your baby is in a complete breech, you may feel kicking in your lower abdomen.

Incomplete breech

In an incomplete breech, one of the baby's knees is bent so that the foot is tucked next to the bottom with the other leg extended, positioning that foot closer to the face.

Single footling breech

In the single footling breech presentation, one of the baby's feet is pointed toward your cervix.

Double footling breech

In the double footling breech presentation, both of the baby's feet are pointed toward your cervix.

Transverse lie

In a transverse lie, the baby is lying horizontally in your uterus and may be facing up toward your head or down toward your feet. Babies settle this way less than 1 percent of the time, but it happens more commonly if you're carrying multiples or deliver before your due date.

If your baby stays in a transverse lie until the end of your pregnancy, it can be dangerous for delivery. Your provider will likely schedule a c-section or attempt an external cephalic version , which is highly successful for turning babies in this position.

Oblique lie

In rare cases, your baby may lie diagonally in your uterus, with his rump facing the side of your body at an angle.

Like the transverse lie, this position is more common earlier in pregnancy, and it's likely your provider will intervene if your baby is still in the oblique lie at the end of your third trimester.

Was this article helpful?

What to know if your baby is breech

What's a sunny-side up baby?

What happens to your baby right after birth

How your twins’ fetal positions affect labor and delivery

BabyCenter's editorial team is committed to providing the most helpful and trustworthy pregnancy and parenting information in the world. When creating and updating content, we rely on credible sources: respected health organizations, professional groups of doctors and other experts, and published studies in peer-reviewed journals. We believe you should always know the source of the information you're seeing. Learn more about our editorial and medical review policies .

Ahmad A et al. 2014. Association of fetal position at onset of labor and mode of delivery: A prospective cohort study. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology 43(2):176-182. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23929533 Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Gray CJ and Shanahan MM. 2019. Breech presentation. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448063/ Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Hankins GD. 1990. Transverse lie. American Journal of Perinatology 7(1):66-70. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2131781 Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Medline Plus. 2020. Your baby in the birth canal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002060.htm Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Where to go next

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- Backchannel

- Newsletters

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

Andy Greenberg

The Full Story of the Stunning RSA Hack Can Finally Be Told

Amid all the sleepless hours that Todd Leetham spent hunting ghosts inside his company’s network in early 2011, the experience that sticks with him most vividly all these years later is the moment he caught up with them. Or almost did.

It was a spring evening, he says, three days—maybe four, time had become a blur—after he had first begun tracking the hackers who were rummaging through the computer systems of RSA, the corporate security giant where he worked. Leetham—a bald, bearded, and curmudgeonly analyst one coworker described to me as a “carbon-based hacker-finding machine”—had been glued to his laptop along with the rest of the company’s incident response team, assembled around the company’s glass-encased operations center in a nonstop, 24-hours-a-day hunt. And with a growing sense of dread, Leetham had finally traced the intruders’ footprints to their final targets: the secret keys known as “seeds,” a collection of numbers that represented a foundational layer of the security promises RSA made to its customers, including tens of millions of users in government and military agencies, defense contractors, banks, and countless corporations around the world.

This article appears in the July/August 2021 issue. Subscribe to WIRED .

RSA kept those seeds on a single, well-protected server, which the company called the “seed warehouse.” They served as a crucial ingredient in one of RSA's core products: SecurID tokens—little fobs you carried in a pocket and pulled out to prove your identity by entering the six-digit codes that were constantly updated on the fob's screen. If someone could steal the seed values stored in that warehouse, they could potentially clone those SecurID tokens and silently break the two-factor authentication they offered, allowing hackers to instantly bypass that security system anywhere in the world, accessing anything from bank accounts to national security secrets.

Now, staring at the network logs on his screen, it looked to Leetham like these keys to RSA’s global kingdom had already been stolen.

Leetham saw with dismay that the hackers had spent nine hours methodically siphoning the seeds out of the warehouse server and sending them via file-transfer protocol to a hacked server hosted by Rackspace, a cloud-hosting provider. But then he spotted something that gave him a flash of hope: The logs included the stolen username and password for that hacked server. The thieves had left their hiding place wide open, in plain sight. Leetham connected to the faraway Rackspace machine and typed in the stolen credentials. And there it was: The server’s directory still contained the entire pilfered seed collection as a compressed .rar file.

Using hacked credentials to log into a server that belongs to another company and mess with the data stored there is, Leetham admits, an unorthodox move at best—and a violation of US hacking laws at worst. But looking at RSA’s stolen holiest of holies on that Rackspace server, he didn’t hesitate. “I was going to take the heat,” he says. “Either way, I'm saving our shit.” He typed in the command to delete the file and hit enter.

Moments later, his computer’s command line came back with a response: “File not found.” He examined the Rackspace server’s contents again. It was empty. Leetham’s heart fell through the floor: The hackers had pulled the seed database off the server seconds before he was able to delete it.

Brendan I. Koerner

Jared Keller

Lauren Goode

Reece Rogers

After hunting these data thieves day and night, he had “taken a swipe at their jacket as they were running out the door,” as he says today. They had slipped through his fingers, escaping into the ether with his company’s most precious information. And though Leetham didn’t yet know it, those secrets were now in the hands of the Chinese military.

Listen to the full story here or on the Curio app .

The RSA breach, when it became public days later, would redefine the cybersecurity landscape. The company’s nightmare was a wake-up call not only for the information security industry—the worst-ever hack of a cybersecurity firm to date—but also a warning to the rest of the world. Timo Hirvonen, a researcher at security firm F-Secure, which published an outside analysis of the breach , saw it as a disturbing demonstration of the growing threat posed by a new class of state-sponsored hackers. “If a security company like RSA cannot protect itself,” Hirvonen remembers thinking at the time, “how can the rest of the world?”

The question was quite literal. The theft of the company's seed values meant that a critical safeguard had been removed from thousands of its customers’ networks. RSA's SecurID tokens were designed so that institutions from banks to the Pentagon could demand a second form of authentication from their employees and customers beyond a username and password—something physical in their pocket that they could prove they possessed, thus proving their identity. Only after typing in the code that appeared on their SecurID token (a code that typically changed every 60 seconds) could they gain access to their account.

The SecurID seeds that RSA generated and carefully distributed to its customers allowed those customers’ network administrators to set up servers that could generate the same codes, then check the ones users entered into login prompts to see if they were correct. Now, after stealing those seeds, sophisticated cyberspies had the keys to generate those codes without the physical tokens, opening an avenue into any account for which someone’s username or password was guessable, had already been stolen, or had been reused from another compromised account. RSA had added an extra, unique padlock to millions of doors around the internet, and these hackers now potentially knew the combination to every one.