When viewing this topic in a different language, you may notice some differences in the way the content is structured, but it still reflects the latest evidence-based guidance.

Breech presentation

- Overview

- Theory

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Follow up

- Resources

Breech presentation refers to the baby presenting for delivery with the buttocks or feet first rather than head.

Associated with increased morbidity and mortality for the mother in terms of emergency cesarean section and placenta previa; and for the baby in terms of preterm birth, small fetal size, congenital anomalies, and perinatal mortality.

Incidence decreases as pregnancy progresses and by term occurs in 3% to 4% of singleton term pregnancies.

Treatment options include external cephalic version to increase the likelihood of vaginal birth or a planned cesarean section, the optimal gestation being 37 and 39 weeks, respectively.

Planned cesarean section is considered the safest form of delivery for infants with a persisting breech presentation at term.

Breech presentation in pregnancy occurs when a baby presents with the buttocks or feet rather than the head first (cephalic presentation) and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality for both the mother and the baby. [1] Cunningham F, Gant N, Leveno K, et al. Williams obstetrics. 21st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1997. [2] Kish K, Collea JV. Malpresentation and cord prolapse. In: DeCherney AH, Nathan L, eds. Current obstetric and gynecologic diagnosis and treatment. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2002. There is good current evidence regarding effective management of breech presentation in late pregnancy using external cephalic version and/or planned cesarean section.

History and exam

Key diagnostic factors.

- buttocks or feet as the presenting part

- fetal head under costal margin

- fetal heartbeat above the maternal umbilicus

Other diagnostic factors

- subcostal tenderness

- pelvic or bladder pain

Risk factors

- premature fetus

- small for gestational age fetus

- nulliparity

- fetal congenital anomalies

- previous breech delivery

- uterine abnormalities

- abnormal amniotic fluid volume

- placental abnormalities

- female fetus

Diagnostic investigations

1st investigations to order.

- transabdominal/transvaginal ultrasound

Treatment algorithm

<37 weeks' gestation and in labor, ≥37 weeks' gestation not in labor, ≥37 weeks' gestation in labor: no imminent delivery, ≥37 weeks' gestation in labor: imminent delivery, contributors, natasha nassar, phd.

Associate Professor

Menzies Centre for Health Policy

Sydney School of Public Health

University of Sydney

Disclosures

NN has received salary support from Australian National Health and a Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship; she is an author of a number of references cited in this topic.

Christine L. Roberts, MBBS, FAFPHM, DrPH

Research Director

Clinical and Population Health Division

Perinatal Medicine Group

Kolling Institute of Medical Research

CLR declares that she has no competing interests.

Jonathan Morris, MBChB, FRANZCOG, PhD

Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Head of Department

JM declares that he has no competing interests.

Peer reviewers

John w. bachman, md.

Consultant in Family Medicine

Department of Family Medicine

Mayo Clinic

JWB declares that he has no competing interests.

Rhona Hughes, MBChB

Lead Obstetrician

Lothian Simpson Centre for Reproductive Health

The Royal Infirmary

RH declares that she has no competing interests.

Brian Peat, MD

Director of Obstetrics

Women's and Children's Hospital

North Adelaide

South Australia

BP declares that he has no competing interests.

Lelia Duley, MBChB

Professor of Obstetric Epidemiology

University of Leeds

Bradford Institute of Health Research

Temple Bank House

Bradford Royal Infirmary

LD declares that she has no competing interests.

Justus Hofmeyr, MD

Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology

East London Private Hospital

East London

South Africa

JH is an author of a number of references cited in this topic.

Differentials

- Transverse lie

- Caesarean birth

- Mode of term singleton breech delivery

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer

Help us improve BMJ Best Practice

Please complete all fields.

I have some feedback on:

We will respond to all feedback.

For any urgent enquiries please contact our customer services team who are ready to help with any problems.

Phone: +44 (0) 207 111 1105

Email: [email protected]

Your feedback has been submitted successfully.

Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

For patients who present in labor with a breech fetus, cesarean birth is the preferred approach in many hospitals in the United States and elsewhere. Cesarean is performed for over 90 percent of breech presentations, and this rate has increased worldwide [ 1,2 ]. However, even in institutions with a policy of routine cesarean birth for breech presentation, vaginal breech births occur because of situations such as patient preference, precipitous birth, out-of-hospital birth, and lethal fetal anomaly or fetal death. Therefore, it is essential for clinicians to maintain familiarity with the techniques required to assist in a vaginal breech birth.

In addition, some clinicians and patients consider vaginal breech birth preferable to cesarean birth. Recent trends, particularly in central Europe, support vaginal breech birth [ 3-5 ]. In selected cases, as described below and depicted in the algorithm ( algorithm 1 ), it is associated with a low risk of complications. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has opined that "Planned vaginal delivery of a term singleton breech fetus may be reasonable under hospital-specific protocol guidelines for eligibility and labor management" [ 6 ].

This topic will focus on vaginal birth of breech singletons, with a brief discussion of breech delivery at cesarean. Choosing the best route of birth for the fetus in breech presentation and delivery of the breech first or second twin are reviewed separately.

● (See "Overview of breech presentation", section on 'Approach to management at or near term' .)

Breech baby at the end of pregnancy

Published: July 2017

Please note that this information will be reviewed every 3 years after publication.

This patient information page provides advice if your baby is breech towards the end of pregnancy and the options available to you.

It may also be helpful if you are a partner, relative or friend of someone who is in this situation.

The information here aims to help you better understand your health and your options for treatment and care. Your healthcare team is there to support you in making decisions that are right for you. They can help by discussing your situation with you and answering your questions.

This information is for you if your baby remains in the breech position after 36 weeks of pregnancy. Babies lying bottom first or feet first in the uterus (womb) instead of in the usual head-first position are called breech babies.

This information includes:

- What breech is and why your baby may be breech

- The different types of breech

- The options if your baby is breech towards the end of your pregnancy

- What turning a breech baby in the uterus involves (external cephalic version or ECV)

- How safe ECV is for you and your baby

- Options for birth if your baby remains breech

- Other information and support available

Within this information, we may use the terms ‘woman’ and ‘women’. However, it is not only people who identify as women who may want to access this information. Your care should be personalised, inclusive and sensitive to your needs, whatever your gender identity.

A glossary of medical terms is available at A-Z of medical terms .

- Breech is very common in early pregnancy, and by 36–37 weeks of pregnancy most babies will turn into the head-first position. If your baby remains breech, it does not usually mean that you or your baby have any problems.

- Turning your baby into the head-first position so that you can have a vaginal delivery is a safe option.

- The alternative to turning your baby into the head-first position is to have a planned caesarean section or a planned vaginal breech birth.

Babies lying bottom first or feet first in the uterus (womb) instead of in the usual head-first position are called breech babies. Breech is very common in early pregnancy, and by 36-37 weeks of pregnancy, most babies turn naturally into the head-first position.

Towards the end of pregnancy, only 3-4 in every 100 (3-4%) babies are in the breech position.

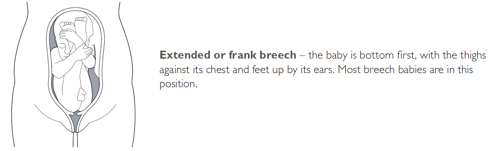

A breech baby may be lying in one of the following positions:

It may just be a matter of chance that your baby has not turned into the head-first position. However, there are certain factors that make it more difficult for your baby to turn during pregnancy and therefore more likely to stay in the breech position. These include:

- if this is your first pregnancy

- if your placenta is in a low-lying position (also known as placenta praevia); see the RCOG patient information Placenta praevia, placenta accreta and vasa praevia

- if you have too much or too little fluid ( amniotic fluid ) around your baby

- if you are having more than one baby.

Very rarely, breech may be a sign of a problem with the baby. If this is the case, such problems may be picked up during the scan you are offered at around 20 weeks of pregnancy.

If your baby is breech at 36 weeks of pregnancy, your healthcare professional will discuss the following options with you:

- trying to turn your baby in the uterus into the head-first position by external cephalic version (ECV)

- planned caesarean section

- planned vaginal breech birth.

What does ECV involve?

ECV involves applying gentle but firm pressure on your abdomen to help your baby turn in the uterus to lie head-first.

Relaxing the muscle of your uterus with medication has been shown to improve the chances of turning your baby. This medication is given by injection before the ECV and is safe for both you and your baby. It may make you feel flushed and you may become aware of your heart beating faster than usual but this will only be for a short time.

Before the ECV you will have an ultrasound scan to confirm your baby is breech, and your pulse and blood pressure will be checked. After the ECV, the ultrasound scan will be repeated to see whether your baby has turned. Your baby’s heart rate will also be monitored before and after the procedure. You will be advised to contact the hospital if you have any bleeding, abdominal pain, contractions or reduced fetal movements after ECV.

ECV is usually performed after 36 or 37 weeks of pregnancy. However, it can be performed right up until the early stages of labour. You do not need to make any preparations for your ECV.

ECV can be uncomfortable and occasionally painful but your healthcare professional will stop if you are experiencing pain and the procedure will only last for a few minutes. If your healthcare professional is unsuccessful at their first attempt in turning your baby then, with your consent, they may try again on another day.

If your blood type is rhesus D negative, you will be advised to have an anti-D injection after the ECV and to have a blood test. See the NICE patient information Routine antenatal anti-D prophylaxis for women who are rhesus D negative , which is available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta156/informationforpublic .

Why turn my baby head-first?

If your ECV is successful and your baby is turned into the head-first position you are more likely to have a vaginal birth. Successful ECV lowers your chances of requiring a caesarean section and its associated risks.

Is ECV safe for me and my baby?

ECV is generally safe with a very low complication rate. Overall, there does not appear to be an increased risk to your baby from having ECV. After ECV has been performed, you will normally be able to go home on the same day.

When you do go into labour, your chances of needing an emergency caesarean section, forceps or vacuum (suction cup) birth is slightly higher than if your baby had always been in a head-down position.

Immediately after ECV, there is a 1 in 200 chance of you needing an emergency caesarean section because of bleeding from the placenta and/or changes in your baby’s heartbeat.

ECV should be carried out by a doctor or a midwife trained in ECV. It should be carried out in a hospital where you can have an emergency caesarean section if needed.

ECV can be carried out on most women, even if they have had one caesarean section before.

ECV should not be carried out if:

- you need a caesarean section for other reasons, such as placenta praevia; see the RCOG patient information Placenta praevia, placenta accreta and vasa praevia

- you have had recent vaginal bleeding

- your baby’s heart rate tracing (also known as CTG) is abnormal

- your waters have broken

- you are pregnant with more than one baby; see the RCOG patient information Multiple pregnancy: having more than one baby .

Is ECV always successful?

ECV is successful for about 50% of women. It is more likely to work if you have had a vaginal birth before. Your healthcare team should give you information about the chances of your baby turning based on their assessment of your pregnancy.

If your baby does not turn then your healthcare professional will discuss your options for birth (see below). It is possible to have another attempt at ECV on a different day.

If ECV is successful, there is still a small chance that your baby will turn back to the breech position. However, this happens to less than 5 in 100 (5%) women who have had a successful ECV.

There is no scientific evidence that lying down or sitting in a particular position can help your baby to turn. There is some evidence that the use of moxibustion (burning a Chinese herb called mugwort) at 33–35 weeks of pregnancy may help your baby to turn into the head-first position, possibly by encouraging your baby’s movements. This should be performed under the direction of a registered healthcare practitioner.

Depending on your situation, your choices are:

There are benefits and risks associated with both caesarean section and vaginal breech birth, and these should be discussed with you so that you can choose what is best for you and your baby.

Caesarean section

If your baby remains breech towards the end of pregnancy, you should be given the option of a caesarean section. Research has shown that planned caesarean section is safer for your baby than a vaginal breech birth. Caesarean section carries slightly more risk for you than a vaginal birth.

Caesarean section can increase your chances of problems in future pregnancies. These may include placental problems, difficulty with repeat caesarean section surgery and a small increase in stillbirth in subsequent pregnancies. See the RCOG patient information Choosing to have a caesarean section .

If you choose to have a caesarean section but then go into labour before your planned operation, your healthcare professional will examine you to assess whether it is safe to go ahead. If the baby is close to being born, it may be safer for you to have a vaginal breech birth.

Vaginal breech birth

After discussion with your healthcare professional about you and your baby’s suitability for a breech delivery, you may choose to have a vaginal breech birth. If you choose this option, you will need to be cared for by a team trained in helping women to have breech babies vaginally. You should plan a hospital birth where you can have an emergency caesarean section if needed, as 4 in 10 (40%) women planning a vaginal breech birth do need a caesarean section. Induction of labour is not usually recommended.

While a successful vaginal birth carries the least risks for you, it carries a small increased risk of your baby dying around the time of delivery. A vaginal breech birth may also cause serious short-term complications for your baby. However, these complications do not seem to have any long-term effects on your baby. Your individual risks should be discussed with you by your healthcare team.

Before choosing a vaginal breech birth, it is advised that you and your baby are assessed by your healthcare professional. They may advise against a vaginal birth if:

- your baby is a footling breech (one or both of the baby’s feet are below its bottom)

- your baby is larger or smaller than average (your healthcare team will discuss this with you)

- your baby is in a certain position, for example, if its neck is very tilted back (hyper extended)

- you have a low-lying placenta (placenta praevia); see the RCOG patient information Placenta Praevia, placenta accreta and vasa praevia

- you have pre-eclampsia or any other pregnancy problems; see the RCOG patient information Pre-eclampsia .

With a breech baby you have the same choices for pain relief as with a baby who is in the head-first position. If you choose to have an epidural, there is an increased chance of a caesarean section. However, whatever you choose, a calm atmosphere with continuous support should be provided.

If you have a vaginal breech birth, your baby’s heart rate will usually be monitored continuously as this has been shown to improve your baby’s chance of a good outcome.

In some circumstances, for example, if there are concerns about your baby’s heart rate or if your labour is not progressing, you may need an emergency caesarean section during labour. A paediatrician (a doctor who specialises in the care of babies, children and teenagers) will attend the birth to check your baby is doing well.

If you go into labour before 37 weeks of pregnancy, the balance of the benefits and risks of having a caesarean section or vaginal birth changes and will be discussed with you.

If you are having twins and the first baby is breech, your healthcare professional will usually recommend a planned caesarean section.

If, however, the first baby is head-first, the position of the second baby is less important. This is because, after the birth of the first baby, the second baby has lots more room to move. It may turn naturally into a head-first position or a doctor may be able to help the baby to turn. See the RCOG patient information Multiple pregnancy: having more than one baby .

If you would like further information on breech babies and breech birth, you should speak with your healthcare professional.

Further information

- NHS information on breech babies

- NCT information on breech babies

If you are asked to make a choice, you may have lots of questions that you want to ask. You may also want to talk over your options with your family or friends. It can help to write a list of the questions you want answered and take it to your appointment.

Ask 3 Questions

To begin with, try to make sure you get the answers to 3 key questions , if you are asked to make a choice about your healthcare:

- What are my options?

- What are the pros and cons of each option for me?

- How do I get support to help me make a decision that is right for me?

*Ask 3 Questions is based on Shepherd et al. Three questions that patients can ask to improve the quality of information physicians give about treatment options: A cross-over trial. Patient Education and Counselling, 2011;84:379-85

- https://aqua.nhs.uk/resources/shared-decision-making-case-studies/

Sources and acknowledgements

This information has been developed by the RCOG Patient Information Committee. It is based on the RCOG Green-top Clinical Guidelines No. 20a External Cephalic Version and Reducing Incidence of Term Breech Presentation and No. 20b Management of Breech Presentation . The guidelines contain a full list of the sources of evidence we have used.

This information was reviewed before publication by women attending clinics in Nottingham, Essex, Inverness, Manchester, London, Sussex, Bristol, Basildon and Oxford, by the RCOG Women’s Network and by the RCOG Women’s Voices Involvement Panel.

Please give us feedback by completing our feedback survey:

- Members of the public – patient information feedback

- Healthcare professionals – patient information feedback

External Cephalic Version and Reducing the Incidence of Term Breech Presentation Green-top Guideline

Management of Breech Presentation Green-top Guideline

Jump to navigation

Planned caesarean section for term breech delivery

What is the issue?

Babies are usually born head first. If the baby is in another position the birth may be complicated. In a ‘breech presentation’ the unborn baby is bottom-down instead of head-down. Babies born bottom-first are more likely to be harmed during a normal (vaginal) birth than those born head-first. For instance, the baby might not get enough oxygen during the birth. Having a planned caesarean may reduce these problems. We looked at evidence comparing planned caesarean sections and vaginal births at the normal time of birth.

Why is this important?

Although having a caesarean might reduce some risks to babies who are lying bottom-first, the operation itself has other risks for the mother and the baby.

What evidence did we find?

We found 3 studies involving 2396 women. (We included studies up to March 2015.) The quality of the studies and therefore the strength of the evidence was mainly low. In the short term, births with a planned caesarean were safer for babies than vaginal births. Fewer babies died or were seriously hurt when they were born by caesarean. However, children who were born by caesarean had more health problems at age two, though the numbers were too small to be certain. Caesareans caused some short-term problems for mothers such as more abdominal pain. They also had some benefits, such as less urinary incontinence and less perineal pain in one study. The studies did not look at effects on future pregnancies, when having had a previous caesarean may cause complications. The studies only looked at single births (not twins or triplets) and did not study premature babies.

What does this mean? If your baby is in the breech position, it may be safer to have a planned caesarean section. However, caesareans may not be so good for the mother and may make future births less safe. We also do not yet know the effects of caesarean birth on babies’ health when they are older.

Planned caesarean section compared with planned vaginal birth reduced perinatal or neonatal death as well as the composite outcome death or serious neonatal morbidity, at the expense of somewhat increased maternal morbidity. In a subset with 2-year follow up, infant medical problems were increased following planned caesarean section and no difference in long-term neurodevelopmental delay or the outcome "death or neurodevelopmental delay" was found, though the numbers were too small to exclude the possibility of an important difference in either direction.

The benefits need to be weighed against factors such as the mother's preference for vaginal birth and risks such as future pregnancy complications in the woman's specific healthcare setting. The option of external cephalic version is dealt with in separate reviews. The data from this review cannot be generalised to settings where caesarean section is not readily available, or to methods of breech delivery that differ materially from the clinical delivery protocols used in the trials reviewed. The review will help to inform individualised decision-making regarding breech delivery. Research on strategies to improve the safety of breech delivery and to further investigate the possible association of caesarean section with infant medical problems is needed.

Poor outcomes after breech birth might be the result of underlying conditions causing breech presentation or due to factors associated with the delivery.

To assess the effects of planned caesarean section for singleton breech presentation at term on measures of pregnancy outcome.

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (31 March 2015).

Randomised trials comparing planned caesarean section for singleton breech presentation at term with planned vaginal birth.

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion and risk of bias, extracted data and checked them for accuracy.

Three trials (2396 participants) were included in the review. Caesarean delivery occurred in 550/1227 (45%) of those women allocated to a vaginal delivery protocol and 1060/1169 (91%) of those women allocated to planned caesarean section (average risk ratio (RR) random-effects, 1.88, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.60 to 2.20; three studies, 2396 women, evidence graded low quality ). Perinatal or neonatal death (excluding fatal anomalies) or severe neonatal morbidity was reduced with a policy of planned caesarean section in settings with a low national perinatal mortality rate (RR 0.07, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.29, one study, 1025 women, evidence graded moderate quality ), but not in settings with a high national perinatal mortality rate (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.24, one study, 1053 women, evidence graded low quality ). The difference between subgroups was significant (Test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 8.01, df = 1 (P = 0.005), I² = 87.5%). Due to this significant heterogeneity, a random-effects analysis was performed. The average overall effect was not statistically significant (RR 0.23, 95% CI 0.02 to 2.44, one study, 2078 infants). Perinatal or neonatal death (excluding fatal anomalies) was reduced with planned caesarean section (RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.86, three studies, 2388 women). The proportional reductions were similar for countries with low and high national perinatal mortality rates.

The numbers studied were too small to satisfactorily address reductions in birth trauma and brachial plexus injury with planned caesarean section. Neither of these outcomes reached statistical significance (birth trauma: RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.16 to 1.10, one study, 2062 infants (20 events), evidence graded low quality ; brachial plexus injury: RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.47, three studies, 2375 infants (nine events)).

Planned caesarean section was associated with modestly increased short-term maternal morbidity (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.61, three studies, 2396 women, low quality evidence ). At three months after delivery, women allocated to the planned caesarean section group reported less urinary incontinence (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.93, one study, 1595 women); no difference in 'any pain' (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.29, one study, 1593 women, low quality evidence ); more abdominal pain (RR 1.89, 95% CI 1.29 to 2.79, one study, 1593 women); and less perineal pain (RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.58, one study, 1593 women).

At two years, there were no differences in the combined outcome 'death or neurodevelopmental delay' (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.52 to 2.30, one study, 920 children, evidence graded low quality ); more infants who had been allocated to planned caesarean delivery had medical problems at two years (RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.89, one study, 843 children). Maternal outcomes at two years were also similar. In countries with low perinatal mortality rates, the protocol of planned caesarean section was associated with lower healthcare costs, expressed in 2002 Canadian dollars (mean difference -$877.00, 95% CI -894.89 to -859.11, one study, 1027 women).

All of the trials included in this review had design limitations, and the GRADE level of evidence was mostly low. No studies attempted to blind the intervention, and the process of random allocation was suboptimal in two studies. Two of the three trials had serious design limitations, however these studies contributed to fewer outcomes than the large multi-centre trial with lower risk of bias.

Clinical Tips of Cesarean Section in Case of Breech, Transverse Presentation, and Incarcerated Uterus

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Juntendo University, Tokyo, Japan.

- 2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Chiba Hokusoh Hospital, Nippon Medical School, Chiba, Japan.

- PMID: 32760790

- PMCID: PMC7396468

- DOI: 10.1055/s-0040-1702985

Cesarean section in breech or transverse presentation involves more complicated procedures than cesarean section in cephalic presentation because the former requires additional manipulations for guiding the presenting part of the fetus, liberation of the arms, and the after-coming head delivery; therefore, those cesarean sections are likely to be more invasive. Making a rather wide uterine incision to prevent uterine injury during delivery of the fetus facilitates smooth delivery of the fetus. Furthermore, in cases of breech or transverse presentation, it is important to initially identify the presenting part of the fetus and guide it to the incision opening in the lower uterine segment, because delivering the presenting part of the fetus first is a basic rule of delivery of the fetus. Smooth delivery of the fetus by means of breech extraction can prevent excessive stress or injury to the fetus. Therefore, it is important to acquire the knowledge and skills necessary to perform these techniques, including the internal version. Smooth delivery of the fetus is also less invasive for the mother because an extension of the uterine excision or injury to arteries and veins in the uterus and parametrium can be avoided. Incarcerated uterus occurring in cases of pregnancy with intrapelvic adhesion, endometriosis, cervical myoma, or extended cervix may result in excessive uterine and cervical injury when a transverse incision of the lower uterine segment is performed without caution. These conditions may result in difficulty in fetal delivery. Therefore, it is important to identify risks in advance and to choose the incision line with great care. Countermeasures for difficult delivery of the fetus need to be mastered by all practitioners of obstetrics. If the transverse incision fails to reach the uterine cavity, an inverted T-shaped or J-shaped incision should be made. Risks of complications such as injury to the cervical canal, the vagina, the bladder or ureter, and massive hemorrhage must be kept in mind.

Keywords: breech presentation; cervical elongation; cesarean section; incarcerated uterus; transverse presentation.

Breech Baby Normal Delivery | Why Vaginal Breech Birth Is Possible Biblical Nutrition Academy Podcast

Happy Mother's Day to all the Mothers out there! Is a breech baby's normal delivery possible? Find out why a vaginal breech birth can be a viable option and how it can help avoid a C-section. In this episode, we discuss the potential benefits of opting for a vaginal delivery in breech presentations under certain conditions. Vaginal delivery avoids the risks associated with surgery, such as infections and complications from anesthesia. Recovery is often faster, with less postpartum pain and shorter hospital stays. Babies born vaginally may have a lower risk of respiratory issues, which is especially important for premature infants. Opting for vaginal delivery can preserve future fertility and provide more options in subsequent pregnancies. Some mothers also prefer the experience of natural labor and delivery, aligning with their birth preferences. Remember, the decision to pursue vaginal delivery for a breech baby should be made with careful consideration and in consultation with healthcare providers to assess individual circumstances and risks. Get access to the FREE Biblical Health Plan: https://thebiblicalnutritionist.com/f... Check out our Mother's Day Specials! https://thebiblicalnutritionist.com/m...

- Episode Website

- More Episodes

- Ⓒ Designed Healthy Living INC

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Glob Health

Maternal and fetal risks of planned vaginal breech delivery vs planned caesarean section for term breech birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Francisco j fernández-carrasco.

1 Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Punta de Europa Hospital, Cádiz, Spain

2 Nursing and Physiotherapy Department, Faculty of Nursing, University of Cádiz, Algeciras, Spain

Delia Cristóbal-Cañadas

3 Neonatal and Paediatric Intensive Care Unit, Torrecárdenas University Hospital, Almeria, Spain

Juan Gómez-Salgado

4 Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Ceuta University Hospital, Midwifery Teaching Unit of Ceuta, University of Granada, Ceuta, Spain

5 Safety and Health Postgraduate Programme, Espíritu Santo University, Guyaquil, Ecuador

Juana M Vázquez-Lara

6 Department of Gynaecology and Obbstetrics, Ceuta University Hospital, Midwifery Teaching Unit of Ceuta, University of Granada, Ceuta, Spain

Luciano Rodríguez-Díaz

Tesifón parrón-carreño.

7 School of Health Sciences, University of Almeria, Almeria, Spain

8 Territorial Delegation of Equality, Health and Social Policies, Health Delegation of Almeria, Almeria, Spain

Associated Data

Breech presentation delivery approach is a controversial issue in obstetrics. How to cope with breech delivery (vaginal or C-section) has been discussed to find the safest in terms of morbidity. The aim of this study was to assess the risks of foetal and maternal mortality and perinatal morbidity associated with vaginal delivery against elective caesarean in breech presentations, as reported in observational studies.

Studies assessing perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with breech presentations births. Cochrane, Medline, Scopus, Embase, Web of Science, and Cuiden databases were consulted. This protocol was registered in PROSPERO CRD42020197598. Selection criteria were: years between 2010 and 2020, in English language, and full-term gestation (37-42 weeks). The methodological quality of the eligible articles was assessed according to the Newcastle-Ottawa scale. Meta-analyses were performed to study each parameter related to neonatal mortality and maternal morbidity.

The meta-analysis included 94 285 births with breech presentation. The relative risk of perinatal mortality was 5.48 (95% confidence interval (CI) = 2.61-11.51) times higher in the vaginal delivery group, 4.12 (95% CI = 2.46-6.89) for birth trauma and 3.33 (95% CI = 1.95-5.67) for Apgar results. Maternal morbidity showed a relative risk 0.30 (95% CI = 0.13-0.67) times higher in the planned caesarean group.

Conclusions

An increment in the risk of perinatal mortality, birth trauma, and Apgar lower than 7 was identified in planned vaginal delivery. However, the risk of severe maternal morbidity because of complications of a planned caesarean was slightly higher.

One of the most controversial topics in obstetrics in recent years has been the discussion about how to deal with breech delivery, whether vaginal or caesarean. Although caesarean is considered a safe way of treating breech delivery, it contributes to high rates of postpartum maternal morbidity in developed countries and it is known to cause significant complications such as anaemia, urinary tract infections, superficial or complete dehiscence of the operative wound, endometritis, inflammatory complications [ 1 ], muscle pain, headache, lack of sexual satisfaction after delivery, digestive problems, fever and infection, abnormal bleeding, and stress urinary incontinence [ 2 ].

However, in 2000, the authors of the Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group (TBT) [ 3 ] published a randomised multicentre collaborative study about how to deal with term breech delivery. They concluded that elective caesareans offered better results than vaginal deliveries in full-term foetuses with breech presentation, while maternal complications were similar between the two groups. So, according to this evidence, the practice of elective caesarean was fostered in such presentations [ 3 ]. Following this trend, the TBT recommendation was adopted by important organisations in many countries, opting for a scheduled caesarean before the end of gestation and this way preventing spontaneous breech vaginal delivery, and the attributed risks, from being triggered [ 4 ].

Subsequently, in 2006 the PREMODA multicentre study was published [ 5 ]. Based on this study, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists changed their protocols that same year and concluded that vaginal delivery in breech presentation and single-term gestation was a reasonable option in properly selected pregnant women and experienced health workers [ 6 ].

Therefore, the TBT study [ 3 ] was called into question and some national associations [ 7 ] included the option of having a vaginal breech delivery in their childbirth care protocol for full-term breech presentation, allowing the free evolution of the delivery process, provided that there is specifically trained staff in the affected centre. This procedure is currently accepted [ 6 ].

Analysing the original TBT data [ 3 ], serious concerns were raised regarding the design of the study, methods, and conclusions. In a considerable number of cases, there was a lack of adherence to the inclusion criteria and there was great interinstitutional variation regarding the standards of care. Also, inadequate methods of foetal antepartum and intrapartum evaluation were used, and a large proportion of women were recruited during active delivery, in many cases, without assistance from a doctor with adequate experience [ 8 ].

Primary caesarean in the first pregnancy has been associated with neonatal and maternal adverse outcomes in subsequent delivery [ 9 ]. In this way, abandoning vaginal delivery with breech presentation and opting indiscriminately for a caesarean would mean denying women access to health care options [ 10 ].

The Cochrane review conducted by Hofmeyr et al., which focused on planned caesarean section for term breech delivery, concluded that it reduced perinatal and neonatal death as well as serious neonatal morbidity, at the expense of somewhat increased maternal morbidity compared with planned vaginal delivery. Authors suggested to consider mother's preference for vaginal birth and risks such as future pregnancy complications, and the option of external cephalic version [ 11 ].

The meta-analysis conducted by Berhan et al. [ 12 ] (1993-2014) aimed at assessing the risk of morbidity and perinatal mortality in breech, full-term and single-foetus deliveries. Results showed a higher relative risk in vaginal delivery for perinatal mortality, trauma at birth, and Apgar at the fifth minute of life.

The present meta-analysis sought to update scientific evidence with the latest studies published in the last 10 years (2010-2020), so the results would be a complementary update. The objective of this meta-analysis was to compare the risks of vaginal delivery with elective caesarean in breech presentations, in terms of neonatal mortality, perinatal trauma, Apgar, neonatal intensive care unit (ICU) admittance, and maternal morbidity, according to evidence published during the last 10 years.

Study design

A systematic review of observational studies and meta-analysis was conducted. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed [ 13 , 14 ].

A systematic bibliographic search was carried out using the Cochrane, Medline, Scopus, Embase, Web of Science, and Cuiden databases. Extensive searches were performed on the reference lists of selected articles. Our search terms included: “breech”, “breech presentation”, “breech birth”, “breech delivery”. During the process, search terms were alternately combined using Boolean logic. The search was based on a clinically answerable question in PICO format, Population (pregnant women with single, full-term foetus, and breech presentation); Intervention (vaginal delivery risks); Comparison (caesarean delivery risks) and Outcomes (risk of neonatal mortality, perinatal trauma, Apgar test with low score, neonatal ICU admittance, and maternal morbidity). Following this structure, the different search strategies were designed. The detailed search strategies employed in each database are summarised in Table S1 in the Online Supplementary Document .

This revision protocol was registered in PROSPERO.

Inclusion and selection criteria

For this study, the default inclusion criteria were:

- Observational studies of cohorts were included; reviews, brief reports, guidelines, and comments were excluded.

- Studies that assessed perinatal mortality and morbidity in relation to the type of delivery with breech presentation.

- Studies published in any language, between January 2010 and September 2020.

- Studies in which the samples were characterised by full-term gestations (between 37 and 42 weeks of gestation), with a single foetus, and breech presentation.

The authors decided to establish observational studies as an inclusion criterion as a review restricted to randomised controlled trials would have given an incomplete summary of the effects of a treatment, due to potential harms. Therefore, ClinicalTrials.gov was not consulted. The studies published before 2010 were excluded because recent scientific publications have turned other previously published ones into outdated evidence, and the aimed was to gather the latest reliable results. In addition, studies where foetuses had lethal congenital abnormalities and caesareans made by other obstetric indications such as multiple pregnancy or intrauterine foetal deaths were also excluded.

The selection of studies was carried out in three stages. First, after reviewing the titles, all relevant literature was retrieved from the respective databases. Second, summaries of all recovered articles were reviewed and then grouped as “eligible for inclusion” or “Not eligible for inclusion”. Third, articles that were grouped as “eligible for inclusion” were revised in detail for the final decision.

The entire process of selection, the quality assessment and also data extraction were carried out by two investigators independently. Each study was individually evaluated by one of the researchers and results were shared. In case of discrepancies, both researchers discussed their arguments and agreement was reached by consensus; occasionally, a third researcher’s assessment was required.

Methodological quality of the included studies

The methodological quality of the eligible articles was assessed according to the Newcastle-Ottawa scale. This scale was designed for assessing the quality of non-randomised studies included in a systematic review and/or meta-analyses. It contains eight items organised in three dimensions: the selection of the study groups (four items); the comparability of the groups (one item); and the ascertainment of the outcome (three items). Studies were evaluated following a star system such that each item can be awarded a maximum of one star, excepting the item related to comparability, which allows the assignment of two stars. The total score ranges between zero and nine stars [ 15 , 16 ].

Data extraction

To structure the collected data, all results compatible with perinatal mortality and morbidity in relation to the type of delivery with breech presentation in full-term gestations (between 37 and 42 weeks of gestation) with a single foetus were searched internationally. The results of the different items were compared on the basis of the primary outcomes, which were neonatal mortality, perinatal trauma, Apgar, neonatal ICU admittance, and maternal morbidity.

Data were extracted using a standard Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet. The extracted data included: the name of the first author, year of publication, period of study, country where the study was conducted in, conclusion of the study, sample size, type of delivery, intrapartum and neonatal mortality, perinatal trauma, Apgar score at the first and fifth minute of life, neonatal ICU admissions, and severe maternal morbidity.

In this review, neonatal mortality was considered as deaths before 7 days of age after birth. The WHO establishes early neonatal mortality up to the seventh day of life. Complications at birth as a result of childbirth are manifested in the first 7 days [ 17 ]. In fact, all the observational studies included in the present meta-analysis took this same period of time as a reference. Perinatal trauma included collarbone fracture, humerus or femur, intracerebral bleeding, cephalic haematoma, facial paralysis, brachial plexus injury, and other trauma.

For this study, severe maternal morbidity was considered as unexpected labour and delivery outcomes that result in significant short-term or long-term consequences for the woman's health. Serious complications of the intervention, whether caesarean or delivery, severe postpartum haemorrhages, neurological problems, sepsis, lung, kidney, or cardiac problems were included [ 18 ].

Statistical analysis

A meta-analysis was performed to evaluate each of the indicators that could measure morbidity and mortality in planned vaginal delivery and scheduled caesarean for breech presentations for both the newborn and the mother.

The Mantel-Haenszel method was used to obtain typical RR estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Heterogeneity was determined using the Cochran’s Q χ 2 test and the I 2 values for the following variables:

(1) Early and incipient neonatal death, (2) birth trauma, (3) Apgar test score at 5 minutes, (4) neonatal admission to ICU, (5) severe maternal morbidity.

Heterogeneity between studies was assessed by calculating values for I 2 and P values. Due to the high I 2 , an important statistic for assessing heterogeneity, the random effects method was used. The I 2 value was interpreted as without heterogeneity (0%), low heterogeneity (<40%), moderate heterogeneity (<60%), substantial heterogeneity (<75%) and considerable heterogeneity (≥75%) [ 19 ]. The stability of the overall RR in the withdrawal of any of the studies was performed by sensitivity analysis (treating one study at a time). All meta-analyses were performed using the Epidat Software 3.0 (Xunta de Galicia, Santiago de Compostela, Spain).

Description of the included studies

The initial electronic search yielded a total of 19 055 references, and after removing duplicate records, 6802 references were reviewed. Of these, after reading the title and abstract, 6644 references were deleted for not meeting the inclusion criteria, so 158 were selected for full text review. Following the research protocol, 142 were excluded because they were not related to the current revision, because some made comparisons between breech and vertex presentation, and others assessed long-term maternal and neonatal complications. Finally, 16 articles were selected for meta-analysis [ 10 , 20 - 34 ]. The selection process is shown in Figure 1 .

PRISMA flowchart.

Of the 16 studies, 10 had been conducted in Europe, 2 in Asia, 2 in Oceania, and 2 in Africa. Of these, 4 were in favour of elective caesarean to minimise neonatal morbidity but recognised that this increased long-term maternal morbidity by conditioning the type of birth for a future pregnancy [ 10 , 21 , 27 , 34 ]. Two of the reviewed studies found that caesarean reduced the risk of neonatal mortality [ 10 , 21 ]. However, 12 of the studies involved in the meta-analysis concluded that vaginal delivery could be an acceptable option in breech presentation provided that strict criteria for the selection of cases were established [ 20 , 22 - 26 , 28 - 33 ]. Sample sizes for the studies included ranged from 111 to 58 320 ( Table 1 ).

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis

Regarding methodological quality assessment, the included studies were scored from 5 to 9 stars according to de Newcastle-Ottawa scale ( Table 2 ). The publication bias was analysed, and results were summarised in Figure S1 and Figure S2 in the Online Supplementary Document .

Methodological quality assessment and quality of evidence*

*Selection: maximum score ****, Comparability: maximum score **, Outcome: maximum score ***. GRADE: 1 = high, 2 = moderate, 3 = low, 4 = very low.

Findings of the meta-analysis

Perinatal mortality analysis consisted of 16 studies and included 94 285 single foetus, full-term, breech presentation deliveries (38 787 planned vaginal deliveries and 55 498 scheduled caesareans). As shown in Figure 2 , perinatal mortality (intrapartum and early neonatal death) in the planned vaginal delivery group was 235 (0.6%), and in the elective caesarean group it was 76 (0.14%) (10,20-34). The grouped meta-analysis has shown that the risk of perinatal mortality was 5.48 (95% CI = 2.61 to 11.51) times higher in the vaginal delivery group than in the planned caesarean group. The overall heterogeneity of the tests showed substantial variability between studies (I 2 = 72%). Sensitivity analysis showed that the overall RR was 3.10; 95% CI = 1.8 - 5.2 (the detailed sensitivity analysis of each variable are summarised in Table S2 in the Online Supplementary Document ).

Meta-analysis of perinatal deaths in full-term singleton breech presentation (planned vaginal delivery vs planned caesarean section) (n = 94 285).

Perinatal trauma analysis included 70 143 single foetus, full-term, breech presentation deliveries (30 523 planned vaginal deliveries and 39 620 planned caesareans). As shown in Figure 3 , perinatal trauma in the planned vaginal delivery group was 285 (0.41%), and in the elective caesarean group it was 124 (0.18%) [ 10 , 20 , 22 - 25 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 32 - 34 ]. The grouped meta-analysis showed a 4.12 (95% CI = 2.46 to 6.89) times increased risk of birth trauma in the planned vaginal delivery group. The overall heterogeneity of the tests showed substantial variability between studies (I 2 = 70%). The sensitivity analysis showed that the overall RR was 3.6 95% CI = 2.17-6.09.

Meta-analysis of perinatal trauma in term singleton breech presentation (planned vaginal delivery vs planned caesarean section) (n = 70 143).

Regarding the Apgar score at minute 5, 13 studies were assessed including 92 135 deliveries with breech, single foetus, and term presentations (37 502 planned vaginal deliveries and 54 633 planned caesareans). 846 (0.92%) neonates of the planned vaginal delivery group had an Apgar below 7 points at the 5th minute of life. Also, in the planned caesarean group, there were 218 (0.24%) neonates whose test score was less than 7 points at 5 minutes of life [ 10 , 20 , 21 , 23 - 27 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 33 ] ( Figure 4 ). The grouped meta-analysis showed a nearly 3.33 (95% CI = 1.95-5.67) times higher risk of the Apgar test having a score of less than 7 points in the planned vaginal delivery group. The overall heterogeneity of the tests showed considerable variability between studies (I 2 = 86%). However, the sensitivity analysis showed that the overall RR was 3.8 95% CI = 2.07-7.25.

Meta-analysis of 5-minute Apgar <7 score in term singleton breech presentation (planned vaginal delivery vs planned caesarean section) (n = 92 135).

Admittance to neonatal ICU assessment included 9 studies, 32 438 single foetus, full-term, breech presentation deliveries (9053 planned vaginal deliveries and 23 385 elective caesareans) were included. In the planned vaginal delivery group, there were 435 (1.86%) admittances at the ICU of newborns, while in the planned caesarean group, the figure was 869 (3.72%) [ 20 , 21 , 23 - 25 , 27 , 29 , 30 ] ( Figure 5 ). The grouped meta-analysis showed a 1.90 (95% CI = 1.34-2.70) times increased risk of admittance to ICU in the planned vaginal delivery group. The overall heterogeneity of the tests showed substantial variability between studies (I 2 = 64%). However, the sensitivity analysis showed that the overall RR was 1.9 (95% CI = 1.36-2.76).

Meta-analysis of intensive care unit (ICU) admissions in term, singleton breech presentation (planned vaginal delivery vs planned caesarean section) (n = 32 438).

Regarding maternal morbidity, the analysis included 4 studies. 4007 single foetus, full-term, breech presentation deliveries were included (863 planned vaginal deliveries and 3144 planned caesareans) [ 23 , 27 , 30 , 34 ] ( Figure 6 ). Maternal morbidity was found in 6 cases (0.69%) for the planned vaginal delivery group, and in 83 cases (2.64%) for the planned caesarean group. The grouped meta-analysis showed a 0.30 (95% CI = 0.13-0.67) times reduced risk of severe maternal morbidity in the planned vaginal delivery group than in the planned caesarean group. The overall heterogeneity of the tests showed very low variability between studies (I 2 = 0%).

Meta-analysis of severe maternal morbidity in term singleton breech presentation (planned vaginal delivery vs planned caesarean section) (n = 4007).

Main findings

The meta-analysis has shown a decreased relative risk perinatal mortality and morbidity in a planned caesarean as compared with a vaginal delivery when breech presentation.

Interpretation

Regardless of whether childbirth is done vaginally or through caesarean delivery, morbidity and mortality rates have been represented higher at breech births than at cephalic births [ 35 ]. Since the publication of TBT [ 3 ], several studies have shown increased morbidity and perinatal mortality with breech presentations in planned vaginal delivery vs planned caesarean [ 9 , 21 , 36 , 37 ]. These results were consistent with TBT [ 3 ] and PREMODA results [ 5 ].

Although the potential biases associated with the observational design of the studies included in this meta-analysis must be recognised, with the consequent caution in comparing results with similar previous studies, our results were in line with previous meta-analyses. According to Berhan et al. [ 12 ], the relative risk of perinatal mortality, trauma at birth, and Apgar at the fifth minute of life were higher in the planned vaginal delivery than in planned caesarean for term singleton breech (3.4 vs 6.3; 3.1 vs 4.2; and 4.7 vs 2.99, respectively). Our study, despite having included only observational studies, agreed with these outcomes.

For the severe maternal morbidity indicator, the present meta-analysis showed a relative risk of 0.30 in favour of vaginal delivery. This means that vaginal delivery is a protective factor against severe maternal morbidity. Although the risk is low, maternal morbidity and mortality increase as a result of complications of a planned caesarean for breech presentations [ 21 , 36 ]. Several studies claimed that planned caesarean may increase the risks for the mother as a result of scarred uterus [ 9 , 21 , 34 ], so the relative safety of planned caesarean should be weighed [ 9 , 38 ].

In the absence of a contraindication for vaginal delivery, a woman with a breech presentation foetus must be truthfully informed, considering the scientific evidence so far, of the risks and benefits of vaginal breech delivery and elective caesarean, so that the woman can decide and consent to the desired type of delivery [ 29 , 39 ]. The woman's decision must be respected and, to do so, the staff attending births must be trained and updated in the assistance of breech vaginal deliveries [ 39 , 40 ]. Otherwise, the woman will be denied a medical treatment option to which she could have turned to [ 40 ].

Regardless of the way of planning the type of delivery, vaginal delivery in breech presentation will always exist, as a delivery may always become urgent and present with these characteristics. Therefore, it is essential that staff attending births do not lose this ability and master it in order to provide quality health care to women [ 39 ].

Strengths and limitations

The risks for neonatal mortality and maternal morbidity implies an ethical dilemma: assuming either the risk of neonatal mortality or the risk of severe maternal morbidity. The risk of neonatal mortality was higher; therefore, we would only consider exposing the mother and foetus to vaginal delivery in the case of good obstetric conditions and given that the health care professional is well trained and experienced in these procedures. Otherwise, we recommend delivery by caesarean section. Our study bases the practice of individualisation on decision-making when choosing the type of delivery in unique gestations with full-term foetuses and breech presentation. Each pregnancy should assess the risks individually, considering the woman's preferences and the context, and seeking a balance between neonatal mortality and maternal morbidity.

Some limitations have been found in conducting this research, starting with the great variability regarding the size of the samples. Studies with very small samples have had little weight when calculating RR in the grouped meta-analysis, while studies with a very large sample size had much more weight. For this reason, we have had to accept a relatively high (moderate) percentage of heterogeneity (I 2 ) in some meta-analyses as, if eliminated, the sample would be drastically reduced.

Vaginal, breech, full-term delivery with a single foetus had a higher risk of morbidity and perinatal mortality than caesarean delivery under the same conditions. Still, the results of this meta-analysis suggested that the risk of vaginal breech delivery is lower than in the results of other previously published studies [ 29 - 31 , 33 , 34 ].

Additionally, the potential bias accompanying observational studies should be acknowledged, given the Newcastle-Ottawa tool identified some items with lack of quality. Therefore, caution is suggested when comparing and generalising the results.

CONCLUSIONS

Term breech birth risks have been analysed according to two possibilities: Vaginal delivery and caesarean delivery risks. Caesarean had high rates of postpartum maternal morbidity. Also, there is no evidence of reduced child perinatal morbidity or mortality. Otherwise, there is no contraindication for vaginal delivery in breech presentation in selected pregnant women and in the presence of experienced health workers.

Our results could help in decision-making related to breech delivery, individualising the decision for each case by knowing the risks associated with each option. From an ethical perspective, the issue addressed in the review is highly sensitive, considering the risk of maternal morbidity and the risk of neonatal mortality. For this reason, further research is suggested that consolidates the available evidence for decision-making between the studied delivery methods.

Additional material

Funding : None.

Authors contributions : Conceptualization, FJFC, DCC, JMVL, TPC and LRD; Data curation, FJFC and DCC; Formal analysis, FJFC, DCC, JGS, JMVL, TPC and LRD; Investigation, FJFC, DCC, JGS, JMVL and TPC; Methodology, FJFC, JGS, JMVL, TPC and LRD; Project administration, TPC and LRD; Resources, DCC, JGS, JMVL and LRD; Software, FJFC, DCC, JGS and LRD; Supervision, JMVL, TPC and LRD; Validation, DCC, JGS, JMVL and TPC; Visualization, TPC; Writing – original draft, FJFC, DCC and JMVL; Writing – review & editing, JGS, JMVL, TPC and LRD.

Disclosure of interest: The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and declare no conflicts of interest.

COMMENTS

A cesarean section in breech presentation involves more complicated procedures than a cesarean section in cephalic presentation because the former requires additional manipulations for guiding the presenting part of the fetus, liberation of the arms, and the after-coming head delivery. Therefore, a cesarean section in breech presentation is ...

1 Delivery of Breech by Caesarean Section . Page 1 Types of Breech Presentation . Page 2 Preoperative ward round and Surgical Brief . Surgical Procedure . Complications . ... This is the commonest type of breech presentation and occurs most frequently in the primigravid woman towards term: the fetal thighs are flexed, but the legs are extended ...

Breech presentation refers to the fetus in the longitudinal lie with the buttocks or lower extremity entering the pelvis first. The three types of breech presentation include frank breech, complete breech, and incomplete breech. ... Planned caesarean section for women with a twin pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Dec 19; 2015 (12 ...

Labour with a preterm breech should be managed as with a term breech. C. Where there is head entrapment, incisions in the cervix (vaginal birth) or vertical uterine D incision extension (caesarean section) may be used, with or without tocolysis. Evidence concerning the management of preterm labour with a breech presentation is lacking.

Observational, usually retrospective, series have consistently favoured elective caesarean birth over vaginal breech delivery. A meta-analysis of 27 studies examining term breech birth, 5 which included 258 953 births between 1993 and 2014, suggested that elective caesarean section was associated with a two- to five-fold reduction in perinatal mortality when compared with vaginal breech ...

Between 1998 and 2002, 35,453 term infants were delivered. The cesarean delivery rate for breech presentation increased from 50% to 80% within 2 months of the trial's publication and remained elevated. The combined neonatal mortality rate decreased from 0.35% to 0.18%, and the incidence of reported birth trauma decreased from 0.29% to 0.08%.

1 INTRODUCTION. Approximately 3% of all infants are born in breech presentation with bottom first, sometimes a foot or knee is leading. 1-3 The risk of breech presentation is sometimes increased, for example, in malformations of the child or the uterus; however, most of the infants and mothers among breech deliveries are totally healthy. 4 Vaginal delivery in breech compared with cephalic ...

Breech presentation is defined as a fetus in a longitudinal lie with the buttocks or feet closest to the cervix. This occurs in 3-4% of all deliveries. The percentage of breech deliveries decreases with advancing gestational age from 22-25% of births prior to 28 weeks' gestation to 7-15% of births at 32 weeks' gestation to 3-4% of births at term.

Summary. Breech presentation refers to the baby presenting for delivery with the buttocks or feet first rather than head. Associated with increased morbidity and mortality for the mother in terms of emergency cesarean section and placenta previa; and for the baby in terms of preterm birth, small fetal size, congenital anomalies, and perinatal ...

Breech birth is a divisive clinical issue, however vaginal breech births continue to occur despite a globally high caesarean section rate for breech presenting fetuses. Inconsistencies are known to exist between clinical practice guidelines relating to the management of breech presentation.

The main types of breech presentation are: Frank breech - Both hips are flexed and both knees are extended so that the feet are adjacent to the head ( figure 1 ); accounts for 50 to 70 percent of breech fetuses at term. Complete breech - Both hips and both knees are flexed ( figure 2 ); accounts for 5 to 10 percent of breech fetuses at term.

Cesarean is performed for over 90 percent of breech presentations, and this rate has increased worldwide . However, even in institutions with a policy of routine cesarean birth for breech presentation, vaginal breech births occur because of situations such as patient preference, precipitous birth, out-of-hospital birth, and lethal fetal anomaly ...

A breech baby (breech birth or breech presentation) is when a baby's feet or buttocks are positioned to come out of your vagina first. This means its head is up toward your chest and its lower body is closest to your vagina. ... Performing a C-section when a baby is breech might be slightly more difficult, but obstetricians are usually familiar ...

Babies lying bottom first or feet first in the uterus (womb) instead of in the usual head-first position are called breech babies. Breech is very common in early pregnancy, and by 36-37 weeks of pregnancy, most babies turn naturally into the head-first position. Towards the end of pregnancy, only 3-4 in every 100 (3-4%) babies are in the breech ...

MedNav is dedicated to developing educational and innovative technology to support healthcare professionals and patients in managing medical conditions in hi...

In a 'breech presentation' the unborn baby is bottom-down instead of head-down. Babies born bottom-first are more likely to be harmed during a normal (vaginal) birth than those born head-first. For instance, the baby might not get enough oxygen during the birth. Having a planned caesarean may reduce these problems.

With a policy of routine caesarean section for breech presentation at term, in time, the clinical skills of vaginal breech delivery will be eroded, placing women who deliver vaginally at increased risk. Implications for research. Childbirth is a profound and unique human experience. Little is known about the evolutionary importance of the birth ...

Methods: At 121 centres in 26 countries, 2088 women with a singleton fetus in a frank or complete breech presentation were randomly assigned planned caesarean section or planned vaginal birth. Women having a vaginal breech delivery had an experienced clinician at the birth. Mothers and infants were followed-up to 6 weeks post partum.

Cesarean section in breech or transverse presentation involves more complicated procedures than cesarean section in cephalic presentation because the former requires additional manipulations for guiding the presenting part of the fetus, liberation of the arms, and the after-coming head delivery; therefore, those cesarean sections are likely to be more invasive.

We undertook the Term Breech Trial to determine whether planned caesarean section was better than planned vaginal birth for selected fetuses in the breech presentation at term. The study was done in centres that could assure women having a vaginal breech delivery that an experienced clinician would be present at the birth.

In 2016 I was pregnant with a baby that refused to move from breech position. It was my first child and the decision about how to bring my baby into the world weighed heavily upon me. At 37 weeks, external cephalic version was attempted, a procedure that felt curiously archaic in its execution, as the usual glut of machines and devices were eschewed in favour of a doctor and nurse valiantly ...

Find out why a vaginal breech birth can be a viable option and how it can help avoid a C-section. In this episode, we discuss the potential benefits of opting for a vaginal delivery in breech presentations under certain conditions. Vaginal delivery avoids the risks associated with surgery, such as infections and complications from anesthesia. ...

Meta-analysis of 5-minute Apgar <7 score in term singleton breech presentation (planned vaginal delivery vs planned caesarean section) (n = 92 135). Admittance to neonatal ICU assessment included 9 studies, 32 438 single foetus, full-term, breech presentation deliveries (9053 planned vaginal deliveries and 23 385 elective caesareans) were included.

Zoo Atlanta is celebrating the birth of a crowned lemur. The newborn was delivered via Cesarean section on May 20 to mother Sava after labor stalled, suggesting a breech presentation. The infant is the fourth surviving offspring of experienced parents Sava, 10, and male Xonsu, 11. Crowned lemurs are found on the northernmost tip of Madagascar ...