- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to present patient...

How to present patient cases

- Related content

- Peer review

- Mary Ni Lochlainn , foundation year 2 doctor 1 ,

- Ibrahim Balogun , healthcare of older people/stroke medicine consultant 1

- 1 East Kent Foundation Trust, UK

A guide on how to structure a case presentation

This article contains...

-History of presenting problem

-Medical and surgical history

-Drugs, including allergies to drugs

-Family history

-Social history

-Review of systems

-Findings on examination, including vital signs and observations

-Differential diagnosis/impression

-Investigations

-Management

Presenting patient cases is a key part of everyday clinical practice. A well delivered presentation has the potential to facilitate patient care and improve efficiency on ward rounds, as well as a means of teaching and assessing clinical competence. 1

The purpose of a case presentation is to communicate your diagnostic reasoning to the listener, so that he or she has a clear picture of the patient’s condition and further management can be planned accordingly. 2 To give a high quality presentation you need to take a thorough history. Consultants make decisions about patient care based on information presented to them by junior members of the team, so the importance of accurately presenting your patient cannot be overemphasised.

As a medical student, you are likely to be asked to present in numerous settings. A formal case presentation may take place at a teaching session or even at a conference or scientific meeting. These presentations are usually thorough and have an accompanying PowerPoint presentation or poster. More often, case presentations take place on the wards or over the phone and tend to be brief, using only memory or short, handwritten notes as an aid.

Everyone has their own presenting style, and the context of the presentation will determine how much detail you need to put in. You should anticipate what information your senior colleagues will need to know about the patient’s history and the care he or she has received since admission, to enable them to make further management decisions. In this article, I use a fictitious case to show how you can structure case presentations, which can be adapted to different clinical and teaching settings (box 1).

Box 1: Structure for presenting patient cases

Presenting problem, history of presenting problem, medical and surgical history.

Drugs, including allergies to drugs

Family history

Social history, review of systems.

Findings on examination, including vital signs and observations

Differential diagnosis/impression

Investigations

Case: tom murphy.

You should start with a sentence that includes the patient’s name, sex (Mr/Ms), age, and presenting symptoms. In your presentation, you may want to include the patient’s main diagnosis if known—for example, “admitted with shortness of breath on a background of COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease].” You should include any additional information that might give the presentation of symptoms further context, such as the patient’s profession, ethnic origin, recent travel, or chronic conditions.

“ Mr Tom Murphy is a 56 year old ex-smoker admitted with sudden onset central crushing chest pain that radiated down his left arm.”

In this section you should expand on the presenting problem. Use the SOCRATES mnemonic to help describe the pain (see box 2). If the patient has multiple problems, describe each in turn, covering one system at a time.

Box 2: SOCRATES—mnemonic for pain

Associations

Time course

Exacerbating/relieving factors

“ The pain started suddenly at 1 pm, when Mr Murphy was at his desk. The pain was dull in nature, and radiated down his left arm. He experienced shortness of breath and felt sweaty and clammy. His colleague phoned an ambulance. He rated the pain 9/10 in severity. In the ambulance he was given GTN [glyceryl trinitrate] spray under the tongue, which relieved the pain to 5/10. The pain lasted 30 minutes in total. No exacerbating factors were noted. Of note: Mr Murphy is an ex-smoker with a 20 pack year history”

Some patients have multiple comorbidities, and the most life threatening conditions should be mentioned first. They can also be categorised by organ system—for example, “has a long history of cardiovascular disease, having had a stroke, two TIAs [transient ischaemic attacks], and previous ACS [acute coronary syndrome].” For some conditions it can be worth stating whether a general practitioner or a specialist manages it, as this gives an indication of its severity.

In a surgical case, colleagues will be interested in exercise tolerance and any comorbidity that could affect the patient’s fitness for surgery and anaesthesia. If the patient has had any previous surgical procedures, mention whether there were any complications or reactions to anaesthesia.

“Mr Murphy has a history of type 2 diabetes, well controlled on metformin. He also has hypertension, managed with ramipril, and gout. Of note: he has no history of ischaemic heart disease (relevant negative) (see box 3).”

Box 3: Relevant negatives

Mention any relevant negatives that will help narrow down the differential diagnosis or could be important in the management of the patient, 3 such as any risk factors you know for the condition and any associations that you are aware of. For example, if the differential diagnosis includes a condition that you know can be hereditary, a relevant negative could be the lack of a family history. If the differential diagnosis includes cardiovascular disease, mention the cardiovascular risk factors such as body mass index, smoking, and high cholesterol.

Highlight any recent changes to the patient’s drugs because these could be a factor in the presenting problem. Mention any allergies to drugs or the patient’s non-compliance to a previously prescribed drug regimen.

To link the medical history and the drugs you might comment on them together, either here or in the medical history. “Mrs Walsh’s drugs include regular azathioprine for her rheumatoid arthritis.”Or, “His regular drugs are ramipril 5 mg once a day, metformin 1g three times a day, and allopurinol 200 mg once a day. He has no known drug allergies.”

If the family history is unrelated to the presenting problem, it is sufficient to say “no relevant family history noted.” For hereditary conditions more detail is needed.

“ Mr Murphy’s father experienced a fatal myocardial infarction aged 50.”

Social history should include the patient’s occupation; their smoking, alcohol, and illicit drug status; who they live with; their relationship status; and their sexual history, baseline mobility, and travel history. In an older patient, more detail is usually required, including whether or not they have carers, how often the carers help, and if they need to use walking aids.

“He works as an accountant and is an ex-smoker since five years ago with a 20 pack year history. He drinks about 14 units of alcohol a week. He denies any illicit drug use. He lives with his wife in a two storey house and is independent in all activities of daily living.”

Do not dwell on this section. If something comes up that is relevant to the presenting problem, it should be mentioned in the history of the presenting problem rather than here.

“Systems review showed long standing occasional lower back pain, responsive to paracetamol.”

Findings on examination

Initially, it can be useful to practise presenting the full examination to make sure you don’t leave anything out, but it is rare that you would need to present all the normal findings. Instead, focus on the most important main findings and any abnormalities.

“On examination the patient was comfortable at rest, heart sounds one and two were heard with no additional murmurs, heaves, or thrills. Jugular venous pressure was not raised. No peripheral oedema was noted and calves were soft and non-tender. Chest was clear on auscultation. Abdomen was soft and non-tender and normal bowel sounds were heard. GCS [Glasgow coma scale] was 15, pupils were equal and reactive to light [PEARL], cranial nerves 1-12 were intact, and he was moving all four limbs. Observations showed an early warning score of 1 for a tachycardia of 105 beats/ min. Blood pressure was 150/90 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18 breaths/min, saturations were 98% on room air, and he was apyrexial with a temperature of 36.8 ºC.”

Differential diagnoses

Mentioning one or two of the most likely diagnoses is sufficient. A useful phrase you can use is, “I would like to rule out,” especially when you suspect a more serious cause is in the differential diagnosis. “History and examination were in keeping with diverticular disease; however, I would like to rule out colorectal cancer in this patient.”

Remember common things are common, so try not to mention rare conditions first. Sometimes it is acceptable to report investigations you would do first, and then base your differential diagnosis on what the history and investigation findings tell you.

“My impression is acute coronary syndrome. The differential diagnosis includes other cardiovascular causes such as acute pericarditis, myocarditis, aortic stenosis, aortic dissection, and pulmonary embolism. Possible respiratory causes include pneumonia or pneumothorax. Gastrointestinal causes include oesophageal spasm, oesophagitis, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, gastritis, cholecystitis, and acute pancreatitis. I would also consider a musculoskeletal cause for the pain.”

This section can include a summary of the investigations already performed and further investigations that you would like to request. “On the basis of these differentials, I would like to carry out the following investigations: 12 lead electrocardiography and blood tests, including full blood count, urea and electrolytes, clotting screen, troponin levels, lipid profile, and glycated haemoglobin levels. I would also book a chest radiograph and check the patient’s point of care blood glucose level.”

You should consider recommending investigations in a structured way, prioritising them by how long they take to perform and how easy it is to get them done and how long it takes for the results to come back. Put the quickest and easiest first: so bedside tests, electrocardiography, followed by blood tests, plain radiology, then special tests. You should always be able to explain why you would like to request a test. Mention the patient’s baseline test values if they are available, especially if the patient has a chronic condition—for example, give the patient’s creatinine levels if he or she has chronic kidney disease This shows the change over time and indicates the severity of the patient’s current condition.

“To further investigate these differentials, 12 lead electrocardiography was carried out, which showed ST segment depression in the anterior leads. Results of laboratory tests showed an initial troponin level of 85 µg/L, which increased to 1250 µg/L when repeated at six hours. Blood test results showed raised total cholesterol at 7.6 mmol /L and nil else. A chest radiograph showed clear lung fields. Blood glucose level was 6.3 mmol/L; a glycated haemoglobin test result is pending.”

Dependent on the case, you may need to describe the management plan so far or what further management you would recommend.“My management plan for this patient includes ACS [acute coronary syndrome] protocol, echocardiography, cardiology review, and treatment with high dose statins. If you are unsure what the management should be, you should say that you would discuss further with senior colleagues and the patient. At this point, check to see if there is a treatment escalation plan or a “do not attempt to resuscitate” order in place.

“Mr Murphy was given ACS protocol in the emergency department. An echocardiogram has been requested and he has been discussed with cardiology, who are going to come and see him. He has also been started on atorvastatin 80 mg nightly. Mr Murphy and his family are happy with this plan.”

The summary can be a concise recap of what you have presented beforehand or it can sometimes form a standalone presentation. Pick out salient points, such as positive findings—but also draw conclusions from what you highlight. Finish with a brief synopsis of the current situation (“currently pain free”) and next step (“awaiting cardiology review”). Do not trail off at the end, and state the diagnosis if you are confident you know what it is. If you are not sure what the diagnosis is then communicate this uncertainty and do not pretend to be more confident than you are. When possible, you should include the patient’s thoughts about the diagnosis, how they are feeling generally, and if they are happy with the management plan.

“In summary, Mr Murphy is a 56 year old man admitted with central crushing chest pain, radiating down his left arm, of 30 minutes’ duration. His cardiac risk factors include 20 pack year smoking history, positive family history, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension. Examination was normal other than tachycardia. However, 12 lead electrocardiography showed ST segment depression in the anterior leads and troponin rise from 85 to 250 µg/L. Acute coronary syndrome protocol was initiated and a diagnosis of NSTEMI [non-ST elevation myocardial infarction] was made. Mr Murphy is currently pain free and awaiting cardiology review.”

Originally published as: Student BMJ 2017;25:i4406

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed

- ↵ Green EH, Durning SJ, DeCherrie L, Fagan MJ, Sharpe B, Hershman W. Expectations for oral case presentations for clinical clerks: opinions of internal medicine clerkship directors. J Gen Intern Med 2009 ; 24 : 370 - 3 . doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0900-x pmid:19139965 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Olaitan A, Okunade O, Corne J. How to present clinical cases. Student BMJ 2010;18:c1539.

- ↵ Gaillard F. The secret art of relevant negatives, Radiopedia 2016; http://radiopaedia.org/blog/the-secret-art-of-relevant-negatives .

Clinical Radiology Case Presentation: Do's and Don'ts

Affiliations.

- 1 Division of Clinical Radiology, Department of Radiodiagnosis, Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, India.

- 2 Division of Clinical Radiology, Department of Interventional Radiology, Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, India.

- PMID: 34316108

- PMCID: PMC8299493

- DOI: 10.1055/s-0041-1729489

Clinical case presentation is part of daily routine for doctors to communicate with each other to facilitate learning, and ultimately patient management. Hence, the art of good clinical case presentation is a skill that needs to be mastered. Case presentations are a part of most undergraduate and postgraduate training programs aimed at nurturing oratory and presentation design skills. This article is an attempt at providing a trainee in radiology a guideline to good case presentation skills.

Keywords: clinical case presentation; clinical radiology case presentation; presentation skills; resident training.

Indian Radiological Association. This is an open access article published by Thieme under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonDerivative-NonCommercial-License, permitting copying and reproduction so long as the original work is given appropriate credit. Contents may not be used for commercial purposes, or adapted, remixed, transformed or built upon. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Publication types

- Bioimaging Sciences

- Bioimaging Sciences Division

- Clinical Trials Office

- TIMC & Imaging Support Services

- Interventional Oncology Research Lab

- Health Care Research

- Publications

- Imaging Informatics

- Abdominal Imaging

- Breast Imaging

- Cardiac Imaging

- Emergency Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Medical Physics

- Musculoskeletal Radiology

- Neuroradiology

- Nuclear Cardiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Pediatric Radiology

- Thoracic Imaging

- VA Services

- Clinical Locations

- CDS Presentation

- EPIC Decision Support FAQ

- Non-EPIC users FAQ

- CMS - CDS – Appropriate Use Criteria

- To Reach Radiology

- Contact for Various Services

- Questions about Contrast

- Difficult to Order Studies

- Protocolling

- Yale Health

- Further Resources

- Official Interpretations on Outside Imaging Exams

- Practice Guidelines

- For Patients

- Premedication Policy

- Oral Contrast Policies

- CT Policy Regarding a Patient with a Single Kidney

- CT Policy Regarding Contrast-Associated Acute Kidney Injury

- For Diabetic Patients on Glucophage

- Gadolinium Based Contrast Agents

- Gonadal shielding policy for and X-ray/CT

- Policy for Power Injection

- Breastfeeding Policies

- Low-Osmolar Iodinated Contrast and Myasthenia Gravis

- CT intraosseous needle iodinated contrast injection

- Policy Regarding Testing for Pregnancy

- YDR Oral Contrast Policy for Abdominal CT in ED Patients

- YDR Policy for Suspected Pulmonary Embolism in Pregnancy

- Insulin Pumps and Glucose Monitors

- Critical Result Guidelines

- Q & A on "Change order" button for CT and MRI protocols

- EpiPen How to & Safety

- Thoracic Radiology

- West Haven VA

- Emeritus Faculty

- Secondary Faculty Listing

- Voluntary Faculty Listing

- Guidelines for Appointment

- Voluntary Guidelines Clarification

- Application Requirements & Process

- Vol. Faculty Contact Info & Conference Scheduling

- Visiting IR Scholarships for Women and URiM

- Neuroimaging Sciences Training Program

- Why Yale Radiology?

- Applicant Information

- Selection Procedure

- EEO Statement

- Interview Information

- Resident Schedule

- Clinical Curriculum

- Being Well @Yale

- Contact Information & Useful Links

- IR Integrated Application Info

- IR Independent Application Info

- Meet the IR Faculty

- Meet the IR Trainees

- YDMPR Program Overview

- Program Statistics

- Applying to the Program

- YDMPR Eligibility

- Current Physics Residents

- Graduated Residents

- Meet the Faculty

- Residents Wellbeing Policy

- Breast Imaging Fellowship

- Body Imaging Fellowship

- Cardiothoracic Imaging Fellowship

- The ED Fellow Experience

- How to Apply

- Virtual Tour for Applicants

- Current ED Fellows

- Meet the ED Faculty

- Applying to the Fellowship

- Fellowship Origins

- Program Director

- Current Fellows

- Howie's OpEd

- Musculoskeletal Imaging Fellowship

- Neuroradiology Fellowship

- Nuclear Radiology Fellowship

- Pediatric Radiology Fellowship

- Tanzania IR Initiative

- Opportunities for Yale Residents

- Medical School Curriculum

- Elective in Diagnostic Radiology

Elective Case Presentations

- Visiting Students

- Physician Assistant (PA) Radiology Course

- Radiology Educational Videos

- Anatomy Presentations

- Visiting IR Scholarships

- Information Technology

- Graduate Students

- Yale-New Haven Hospital School of Diagnostic Ultrasound

- Radiologic Technology Opportunities

- Educational Resources

- CME & Conferences

- The Boroff-Forman Lecture Series

- Grand Rounds Schedule

- Yale Radiology & Biomedical Imaging Global Outreach Program Tanzania

- Contrast Policies

- MRI Safety Policies and Procedures

- Pregnancy related guidelines

- Radiation safety policies

- COVID19 related SBARS

- Other policies

- Peer Learning and Fellow recheck Program

- Attending Radiologists Resources and SOPs

- Related News and Articles

INFORMATION FOR

- Residents & Fellows

- Researchers

Cardiothoracic

- Skip List Items

- Aberrant Right Subclavian artery

- Anterior_Superior Mediastinal Mass

- Aortic Transection

- Assymetric Pulmnary Edema

- Dermatomyositis ILD

- Post Operative Mediastinal Infections

- Posterior Mediastinal Mass

Gastrointestinal

- Aberrant Left Subclavian

- Colonic Rupture

- Colovesicular Fistula

- Diverticulitis

- Esophagram Complications

- Gallstone Illeus

- Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma

- Portal Venous Gas

- Toxic Megacolon

Genitourinary

- Autosomal Domminant Polycystic Kidney Disease

- Bladder Pheochromocytoma

- Urachal Adenocarcinoma

Musculoskeletal

- Multiple Myeloma

- Osteosarcoma Humerus

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

Miscellaneous

- Retroperitoneal Hemorrhage

- Retropharyngeal Abscess

- Splenic Laceration

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Cardiovasc Dis

- v.2(3); 1975

RADIOLOGIC CASE PRESENTATION

L. paul gerson.

Department of Radiology, St. Luke's Episcopal and Texas Children's Hospitals, Houston, Texas 77025.

Edward B. Singleton

2 Texas Heart Institute, Houston, Texas 77025.

Full text is available as a scanned copy of the original print version. Get a printable copy (PDF file) of the complete article (453K), or click on a page image below to browse page by page.

Images in this article

Image on p.257

Click on the image to see a larger version.

- UTHealth Houston

- UTHealth TMC IR Residents

- Recent Alumni

- TMC IR Faculty

- How to Apply

- Welcome from the Chiefs

- Curriculum and Education

- Benefits, Moonlighting, and Wellness

- Clinician-Educator Track & Teaching

- Resident Research

- Resident Leadership & Accomplishments

- Dual Certification in DR and Nuclear Radiology

- Interviews and Open House

- Class of 2024

- Class of 2025

- Class of 2026

- Class of 2027

- Application Process

- Salary and Benefits

- Program Personnel

- Body Imaging

- Training Program

- Neuroradiology Faculty

- Previous Fellows

- Equipment List

- Research and Publications

- Program Contact

- PET/CT Imaging Mini-Fellowship with hands-on training

- Sports, Orthopedic and Emergency Imaging Fellowship

- Cardiothoracic Fellowship

- Current Fellows

- Course Overview & Electives

- Relevant Links

- Radiology Research Opportunities

- Visiting Student

Case Presentations

- Meet the Officers

- Monthly Meeting Calendar

- Educational Resources

- Conference Schedules

CASE PRESENTATIONS 2021 – 2022

Acute ACL Tear_Andrew Wang, MS4_Kumaravel, MD_June 2021

Tibial Plateau Fractures, Joseph Wilder, MS4, Kumaravel, MD_June 2021

Anoxic Brain Injury_Parth Patel, MS3_Lee, MD_Patel_June 2021

Uterine Scar Endometriosis_KarenPereira, MS3_Sanhaji, MD_June 2021

Acute splenic laceration_Bryan Hoang, MD_Pomfret, MD_Tapnio, MD_June 2021

Pediatric Omental Infarction_Emma Holmes, MS4_Hester, MD_Tapnio, MD_June 2021

Aortic Dissection_Joseph Kim, MS4_Kumaraval, MD_Awdeh, MD_May 2021

Desmoid Tumor_Ava Mirtsching, MS4_Bande, MD_Awdeh, MD_May 2021

Nonspecific Interstital Pnemonia (NSIP)-Interstital Lund Disease (ILD)_Ashley Tom, MS4_Su, MD_Awdeh, MD_May 2021

CASE PRESENTATIONS 2020 – 2021

ARDS Shelley Burge, MS4_Kumaravel, MD_Awdeh, MD_Apr 2021

Acute Appendicitis_John Jackson, MS4, Awdeh, MD_Apr 2021

Cervical Spine Facture_Anamaria Dragan, MS4, Pomfret, MD, Awdeh, MD_Apr 2021

Back pain following a fall, Jesse Degani, MS4, Awdeh, MD, Mar 2021

COVID Pneumonia with ARDS, Jessilyn Laney, MS4, Awdeh, MD, Mar 2021

Dens Type II, Aashini Patel, MS4, Kumaravel, MD, Awdeh, MD, Mar 2021

Extubated Pediatric Patient with Worsening Respiratory Status, Kayla Walter, MS4, Schwartz, MD, Awdeh, MD, Mar 2021

Mesenteric Ischemia Presentation, William Morris, MS4, Su, MD, Awdeh, MD, Mar 2021

Methotrexate Leukoencephalopathy, Sungita Kumar, MS4, Bonfante-Mejia, MD, Awdeh, MD, Mar 2021

Necrotizing Pancreatitis, Frances Howard, MS4, Wang, MD, Awdeh, MD, Mar 2021

Pneumoperitoneum, Chad Zhao, MS4, Awdeh, MD, Mar 2021

Acute Pancreatitis, Sarah Linson MS4, Lambert, MD, Wang, MD, Foss,MD, Awdeh, MD, Feb 2021

Advanced Neurodegeneration, Nicloe Thomason MS4, Khanpara, MD, Awdeh, MD, Feb 2021

Ankle Pain, Angie Aceves MS4, Awdeh, MD, Feb 2021

Appendiceal Rupture, Alexander Yin MS4, Awdeh, MD, Feb 2021

Bisphosphonate Fracture, Eric Tom MS4, Awdeh, MD, Feb 2021

Incidental Cardiac Finding, John Krapf MS4, Awdeh, MD_Feb 2021

Lateral Epicondylitis, Annika Medhus MS4, Kumaravel, MD_Awdeh, MD, Feb 2021

Mature Cystic Ovarian Teratoma, Olivia Ortiz MS4, Foss, MD, Awdeh, MD, Feb 2021

Pulmonary Embolism, Kyle Meissner MS4, Awdeh, MD, Feb 2021

Pyelonephritis, Eric Fris MS4, Awdeh, MD, Feb 2021

Vacterl, Tori Waters MS4, McCarty, MD, Awdeh, MD, Feb 2021

Abscess_Thomas Rogers, MS4_B.Wand, MD_Awdeh, MD_Jan 2021

Acute Triquetral Fracture _ Radiocarpal Subluxation_Jason Fuller, MS4_Bilow, MD_Awdeh, MD_Jan 2021AD 4013

Distal Femur Fracture Due to Trauma_Maryam Haider, MS4_Bilow, MD_Awdeh, MD_Jan 2021

Filum Terminale Lipoma_Zachary DeZeeuw, MS4_Samant, MD_Awdeh, MD_Jan 2021

Ground Level Fall in a patient w_ Cerebral Palsy_Jacqueline Dickey, MS4_Bilow, MD_Awdeh, MD_Jan 2021

Malrotation_Keziah Thomas, MS4_Qiao, MD_Awdeh, MD_Jan 2021

Renal Abscess _ Pyelonephritis_Weston Grove, MS4_Green, MD_Awdeh, MD_Jan 2021

Traumatic Pneumothorax_Stephen Palasi, MS4_Kumaraval, MD_Bawa, MD_Awdeh, MD_Jan 2021

ACL Tears_Adam Lazarus MS4_Spence, MD_Awdeh, MD_Dec 2020

Acute Scrotum in Children_John McCarthy, MS4_Tavernier, MD_Awdeh, MD_Dec 2020

Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis_Min Yi Dong, MS4_Pomfret, MD_Awdeh, MD_Dec 2020

Fracture w_ Ankylosing Spondylitis_Frederick Lemaistre, MS4_ Hester, MD, Awdeh, MD_Dec 2020

MVA Fractures and Pneumothorax_Bert Ma, MS4_Greenfield, MD_Awdeh, MD_Dec 2020

Pulmonary Abscess_Marina Ibraheim, MS4_Conners, MD_Awdeh, MD_Dec 2020

Shoulder Dislocation with Bony Defects_Sahira Farooq, MS4_Bilow, MD_Awdeh, MD_Dec 2020

Tibial Avulsion Fractures_Nicolas Merutka, MS4_Bilow, MD_Awdeh, MD_Dec 2020

Traumatic Splenic Laceration_Kyle Lauck, MS4_Bilow, MD_Awdeh, MD_Dec 2020

Abdominal Pain_Ge Yan MS4_R. Hlis, MD_H. Awdeh, MD_Nov 2020

Aortic Dissection_Kyle Sheppard MS4_F. Celii, MD_H. Awdeh, MD_Nov 2020

Blunt Chest Truama_Michelle Ghebranious MS4_L. Ellerbrook, MD_H. Awdeh, MD_Nov 2020

Cervical Spine Truama_Justin Carranza MS4_C. Desai, MD_H. Awdeh, MD_Nov 2020

Extrahepathatic Cholangiocinoma_Angela Sheng MS4_W. Floss,MD_H. Awdeh,MD_Nov 2020

Femur Fracture _ Fat Emboli_Margeaux Epner MS4_E. Friedman, MD_H. Awdeh, MD_Nov 2020

Fracture of the Right Hip_Keziah Thomas MS4_W. Green, MD_H. Awdeh, MD_Nov 2020

Horseshoe Kidney_Shannon Swisher MS4_S. Neville, MD_H. Awdeh, MD_Nov 2020

Left Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage_Angela Murira MS4_R. Hills, MD_Awdeh, MD_Nov 2020

Seatbelt Syndrome_Devonne Harris MS4_N Chinapuvvala, MD_C. Desai, MD_H. Awdeh_Nov 2020

Subdural Hematoma_Jacqueline Woloski MS4_C. Sitton, MD_H. Awdeh, MD_Nov 2020

Translational Injury_Priscila Olague MS4_Y. Munir, MD_H. Awdeh, MD_Nov 2020

Abdominal Wall Abscesses_Jessica Williams MS4_Talley, MD_Awdeh, MD_Oct 2020

Acute Appendicitis_Tracy Nwanna MS4_Kumaravel, MD_Awdeh, MD_Oct 2020

Blunt Trauma-Spine_Amy Mulikin MS4_Bosserman, MD_Awdeh, MD_Oct 2020

Colonic Pseudo-Obstruction-Ogilvie Syndrome_Andrei Loghin MS4_Doyle, MD_Jarolimek, MD_Awdeh, MD_Oct 2020

Hepatic Encephalopathy_Frank Cai MS4_Pasciak, MD_Awdeh, MD_Oct 2020

Necrotizing Enterocolitis_Jocelyn Ursua MS4_John, MD_Awdeh, MD_Oct 2020

Ovarian Cysts-Dysmenorrhea_Jamie Haro-Silerio MS4_Bande, MD_Awdeh, MD_Oct 2020

Sarcomatoid Renal Cell Carcinoma_Ayana Taylor MS4_Talley, MD_Hasapes,MD_Awdeh, MD_Oct 2020

Trauma-Pneumothorax_Fauniel Self MS4_Bosserman, MD_Awdeh, MD_Oct 2020

Traumatic Bowel Injury_Rachel Carson MS4_Bilow MD, Awdeh MD_Oct 2020

Uterine Anomalies_Danielle Wilson MS4_Bilow, MD_Awdeh, MD_Oct 2020

ACL tear, Jordon Price MS4, A Bosserman MD Sep 2020

Anoxic brain Injury, Daniel Abramson MS4, M Patino MD Sep 2020

Gallstone Ileus Sally Choi MS4, M Lambert MD Sep 2020

Imaging in Sickle Cell disease, Maria Hernandez MS4, Thupili MD Sep 2020

Perilunate dislocation, Kevin Sok MS4, M Kumaravel MD Sep 2020

Rotator Cuff Repair, John Howell MS4, Kumaravel MD Sep 2020

Cystic Peritoneal Mass, Alexa Janda MS4, Kramer MD Aug 2020

Distal Femoral Fracture, Joaquin Santoy MS4, Scott MD Aug 2020

Hip Fracture, Ashley Notzon MS4, M Kumaravel MD MSK Aug 2020

Ocular Trauma Alex Villarreal MS4, S Scott MD, Aug 2020

Brain death, Kehan Vohra MS4, Bilow MD, ER July 2020

Comminuted Distal Femoral Fracture, Kevin Sok MS4, Kumaravel MD, MSK July 2020

Distal Tibial Fracture, Sally Choi MS4, Kumaravel MD, MSK July 2020

Peritonsillar Abscess, Austin Pickrell MS4, Patino MD, Clark MD July 2020

Rapunzel Syndrome Aashini Patel MS4, Greenfield MD, Pedi July 2020

Subcutaneous Emphysema, Annika Medhus MS4, Bande MD, thoracic July 2020

Traumatic Arm injury, Justin Tran MS4, Bilow MD, ER July 2020

CASE PRESENTATIONS 2019-2020

Womens’ Imaging

Ruptured Ectopic Pregnancy, Trinh Tammy MS4, P Bawa MD

Ductal Carcinoma of the Breast, Janda Alexandra MS3, M Kumaravel MD

Malignant Phyllodes Tumor, Vu Alan MS4, M Kumaravel MD

Body Imaging

Cirrhosis, Jessica Sanders MS3, Nathan Doyle MD, P Bawa MD

Vesicoureteral Reflux Cross Fused Ectopy, Joshua Rosengarten MS4, M. Kumaravel MD

Xanthogranulomatous Pyelonephritis, Davis Joy MS3, S. Narayanan MD

Abdominal Gun Shot Wound, Dugger Samuel MS4, P Bawa MD

Adenosquamous Carcinoma, Leonid Khokhlov MS4 Visiting Student, Dr. P.Bawa

Bladder Wall Injury, Dunlop Catherine MS4, P Bawa MD

Boerhaave Syndrome and Esophageal Stricture, Gaglani Tanmay MS4, Dr. Thosani, Dr. Thupili

Cervical Ectopic Pregnancy, David Wideman MS4, M. Kumaravel MD

Chronic Pancreatitis, Ontiveros Diana MS4, Dr. J. Talley PGY2

Gluteal Abscess, Maryam Alam MS3, P Bawa MD

Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Desai Ami MS4, N. Doyle MD, S. Burke MD

Metastatic Cholangiocarcinoma, Chernis Julia MS4, P Bawa MD, A Wolfe MD, C Costelleo MD

Mucinous Adenocarcinoma, lliana Chapa MS4, Wan MD, Shin MD

Ovarian Cancer with Large Bowel Obstruction, Bareis Alexander MS4,M. Kumaravel MD

Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma, Wright Kaylor MS4,S Burke MD, V. Tammisetti MD

Renal Cell Carcinoma, John Howell MS3, M Hanna MD

Sigmoid Volvulus, Sorkin Johnathan MS4, M. Redwine MD, S. Balabhadra MD

Testicular Seminoma, Haqqani Fatima MS4, R. Vikram MD

ER Radiology

Aortic Injury , Steven Ajluni C., Dr. P. Bawa, Dr. M. Kumaravel

Avulsion with Liver Laceration and Hemoperitoneum, Wood Roland MS4, Dr. R. Bilow

Blunt Aortic Injury_ Aortic Transection of Proximal Descending Aorta with Pseudoaneurysm, Drummond, Olivia MS4, L. Sanhaji MD

Brain Hemorrhage GSW, Rose Kevelyn MS4, R.Bilow

Cervical Spine Trauma, Ellis Ryan C MS4, C. Carney MD

Eye Trauma, Howard James J MS4, M. Tran MD

Facial Trauma, Wythe Stephanie MS4, M. Kumaravel MD

Pelvic Fracture and Extraperitoneal Bladder Rupture, Cooper Quiroz MS4, Dr. Chinapuvvula

Splenic Injury with Subcapsular Hematoma and Pseudoaneurysms , Alford Yakira MS4, Dr. R. Bilow

Traumatic Thoracic Aortic Pseudoaneurysm , Sullivan Kirbi MS4, N. Chinapuvvula MD

MSK – Radiology

Multiple Myeloma, Chopra Maneera MS4, Dr. P. Bawa, Dr. B. Wang

Anterior Bundle Ulnar Collateral Ligament Tear, Tran Justin MS3, M. Kumaravel MD

Biceps Tendon Injury, Carter Dalton MS4, P. Bawa MD

Chondroblastoma of the Knee, Milhoan Madison MS4, Dr. R. Kumar

Distal Femur Fracture, Andrews Reid MS4, Dr. P.Bawa

Osteoarthritis-Osteoarthrosis of the Knees, Patrick Conner MS4, Dr. H. Awdeh

Patella Tendon Tear, Rabinovich A. MS4, Dr. K. Bande, Dr. N. Beckmann

Pelvic Ring Injury, Hays Matthew MS4, Dr. P.Bawa

Segond Fracture, Choi Sally MS3, Dr. M. Kumaravel

Sickle Cell Crisis, Gaskey Gregory MS4, M. Kumaravel MD

Vertebral Osteomyelitis , Lam Brian MS4, S. Belchuk MD, K. Bande MD

Pedi Radiology

Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis, Martin Amanda MS4, H.Awdeh

Grade 3 Vesicoureteral Reflux, Lin Amanda MS4, M. Kumaravel MD

Hirschsprung Disease , Amber Garza MS4, M. Kumaravel MD

Hirschsprung Disease_, Hicks Kelsey MS4, M. Kumaravel MD

Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, Alexandria Lawrence MS4, Dr. P. Bawa. pdf

Intussusception, Abeysekera Radhini MS4, Dr. Wang PGY-2, Dr. H. Awdeh

Sepsis/Hydronephrosis 2/2 Obstructive Infected Nephrolithiasis, Rozean Colby MS4,P. Bawa MD

Acute Appendicitis, Chen Vanessa MS4, C. Yalniz MD

Brainstem Pilocytic Astrocytoma , Arca Makenna MS3, E. Bonfante- Mejia MD

Left Lung Pneumatocele , Jacob Dangerfield MS4, K. Hughes MD

RSV with Acute Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure, Air leak Syndrome with Spontaneous Pneumothorax, Pneumomediastinum and Pneumoperitoneum, Steward Sydne MS3, Dr. J. Hester, Dr. S. Greenfield

Salter Harris II Tibial Fracture, Kyra Frost MS4, Dr.M. Kumaravel

Salter-Harris III (Tillaux) Fracture, Dillion William MS4, Dr. Johnathan D Hester

Thoracic Imaging

Anterior Mediastinal Mass, Omar Alnatour MS4, Dr. P. Bawa

Pulmonary Embolism with Right Heart Strain, Hancock Saxon MS4, M. Kumaravel MD

Cardiac Tamponade Non-inflammatory Pericardial Effusion, Sandra Coker MS4, Dr. P.Bawa

Interstitial Lung Disease-Head Cheese Sign, Isabella Alamo-Ciufetelli MS3, B. Wang MD, Dr. P.Bawa

Pulmonary Embolism, Marc St Cyr MS4, Dr. P. Bawa

Pulmonary Nodule, Ashley Notzon MS3, E. Odisio MD, M. Lambert MD

VASC/IR – Radiology

Angiography Pre-Embolization with Internal Iliac Artery Selection, Viranmontes Jose MS4, J. Guccione MD

Bronchial Artery Embolization, Zacharia Grami MS4, Dr. K. Bande MS2

Clear Cell RCC, Srinivasan Aditya MS4, K. BlairMD

Mesenteric Angiography with Intervention for Chronic Portal Vein Occlusion, Korf Janelle MS3, Dr. Z. Bhatti

MSSA Endocarditis, Andrew Gulde MS4, Dr. P.Bawa

Positional Plagiocephaly, Coburn Ryan MS4, R Patel MD

- McGovern Medical School Facebook Page

- McGovern Medical School X Page

- McGovern Medical School Instagram Page

- McGovern Medical School YouTube Page

- McGovern Medical School LinkedIn Page

- Medical School IT (MSIT)

- Campus Carry

- Emergency Info

- How to report sexual misconduct

- University Website Policies

Case report

- Report problem with article

- View revision history

Citation, DOI, disclosures and article data

At the time the article was created Matt A. Morgan had no recorded disclosures.

At the time the article was last revised Matt A. Morgan had no recorded disclosures.

- Case reports

Case reports are a type of radiology research literature. They belong to the class of descriptive studies .

On this page:

- Related articles

The purpose of a radiology case report is to describe the patient history, clinical course, and imaging for a notable or unusual case. The case may be intended to aid other practitioners in interpretation, but frequently the oddity, rarity, and non-generalisibility of cases are meant more to amuse or entertain the reader.

A case report typically contains:

- a short introduction

- patient history and presentation

- a discussion of the imaging and other relevant interventions

- patient course

- summary/discussion

In radiology case reports, images from multiple imaging modalities are usually included, and gross pathology or histology is considered an excellent addition.

Case reports are generally considered the easiest and fastest radiology research paper to assemble.

Although debatable, the lack of "generalisibility" of case reports causes them to be regarded as lesser vehicles within research. Many journals will no longer accept case reports, for various reasons.

One disadvantage of case reports is that it may contribute to a type of recall bias in the reader. The attention the reader gives to a vanishingly rare case is held by the mind in a disproportionate regard compared with more common cases. The well-known maxim "an atypical presentation of a common disease is more likely than a typical presentation of a rare disease", is an effort to combat this type of bias.

Other disadvantages of case reports include:

- large numbers of case reports introduce an element of "noise" when searching the literature

- case reports claiming the first presentation of a case often find that they are actually not the first

- journals find that case reports do not get accessed as much as original research (it lowers their "impact factor")

That said, there are some advantages to case reports as well:

- the easier format allows junior researchers a chance to contribute to the literature, and helps them develop their skills

- a few case reports may develop into larger contributions to original research (for instance, in interventional radiology)

- they can be entertaining

- 1. Buckley O, Torreggiani WC. The demise of the case report. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189 (2): W54-5. doi:10.2214/AJR.07.2203 - Pubmed citation

- 2. Branstetter BF. Case reports: a premature demise. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190 (1): W80. doi:10.2214/AJR.07.2953 - Pubmed citation

Incoming Links

- BJR|case reports

- Case series

Related articles: Research

- case report

- case series

- Bayes' theorem

- Bayes' factor

- sensitivity

- specificity

- sensitivity and specificity of multiple tests

- positive predictive value (PPV)

- negative predictive value (NPV)

- incidence

- likelihood ratio (LR)

- standard error of the mean

- confidence interval (CI)

- retrospective studies

- prospective studies

- student t-test

- paired t-test

- one-way ANOVA

- factorial ANOVA

- repeated measures ANOVA

- multivariate ANOVA (MANOVA)

- single linear regression

- multiple linear regression analysis

- multiple logistic regression analysis

- chi-squared test

- automation bias

- length time bias

- lead time bias

- recall bias

- selection bias

Promoted articles (advertising)

ADVERTISEMENT: Supporters see fewer/no ads

By Section:

- Artificial Intelligence

- Classifications

- Imaging Technology

- Interventional Radiology

- Radiography

- Central Nervous System

- Gastrointestinal

- Gynaecology

- Haematology

- Head & Neck

- Hepatobiliary

- Interventional

- Musculoskeletal

- Paediatrics

- Not Applicable

Radiopaedia.org

- Feature Sponsor

- Expert advisers

Case of pediatric cerebellar, hippocampal, and basal nuclei transient edema with restricted diffusion (CHANTER) syndrome in a 2-year-old girl

- Case Report

- Open access

- Published: 17 April 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Robert A. Koenigsberg 1 , 2 ,

- Luke Ross ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0000-0884-8362 1 ,

- Jason Timmerman 1 ,

- Rithika Surineni 1 ,

- Kara Breznak 2 &

- Tina C. Loven 2

157 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Cerebellar, hippocampal, and basal nuclei transient edema with restricted diffusion (CHANTER) syndrome is a recently described entity that refers to a specific pattern of cerebellar edema with restricted diffusion and crowding of the fourth ventricle among other findings. The syndrome is commonly associated with toxic opioid exposure. While most commonly seen in adults, we present a case of a 2-year-old girl who survived characteristic history and imaging findings of CHANTER syndrome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Bilateral lesions of the basal ganglia and thalami (central grey matter)—pictorial review

Autoimmune encephalitis: what the radiologist needs to know

Comprehensive review of Wernicke encephalopathy: pathophysiology, clinical symptoms and imaging findings

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cerebellar, hippocampal, and basal nuclei transient edema with restricted diffusion (CHANTER) syndrome represents a rare disorder with a constellation of imaging findings in patients with opioid neurotoxicity. Clinically, patients present with altered mental status in the context of substance intoxication. The recently described pattern of imaging findings includes cytotoxic edema in bilateral hippocampi, cerebellar cortices, and the basal ganglia [ 1 ]. Patients also frequently develop early obstructive hydrocephalus from fourth ventricular compression [ 2 ]. Although these findings are usually associated with irreversible neuronal death and poor overall outcomes, patients with CHANTER syndrome can show significant clinical and radiographic improvement over time [ 1 ]. The disease has almost exclusively been observed and reported in adults, but we present the case of a 2-year-old girl who was found unconscious after consuming fentanyl. Her clinical presentation, history, and subsequent imaging findings are all consistent with a diagnosis of CHANTER syndrome.

Case description

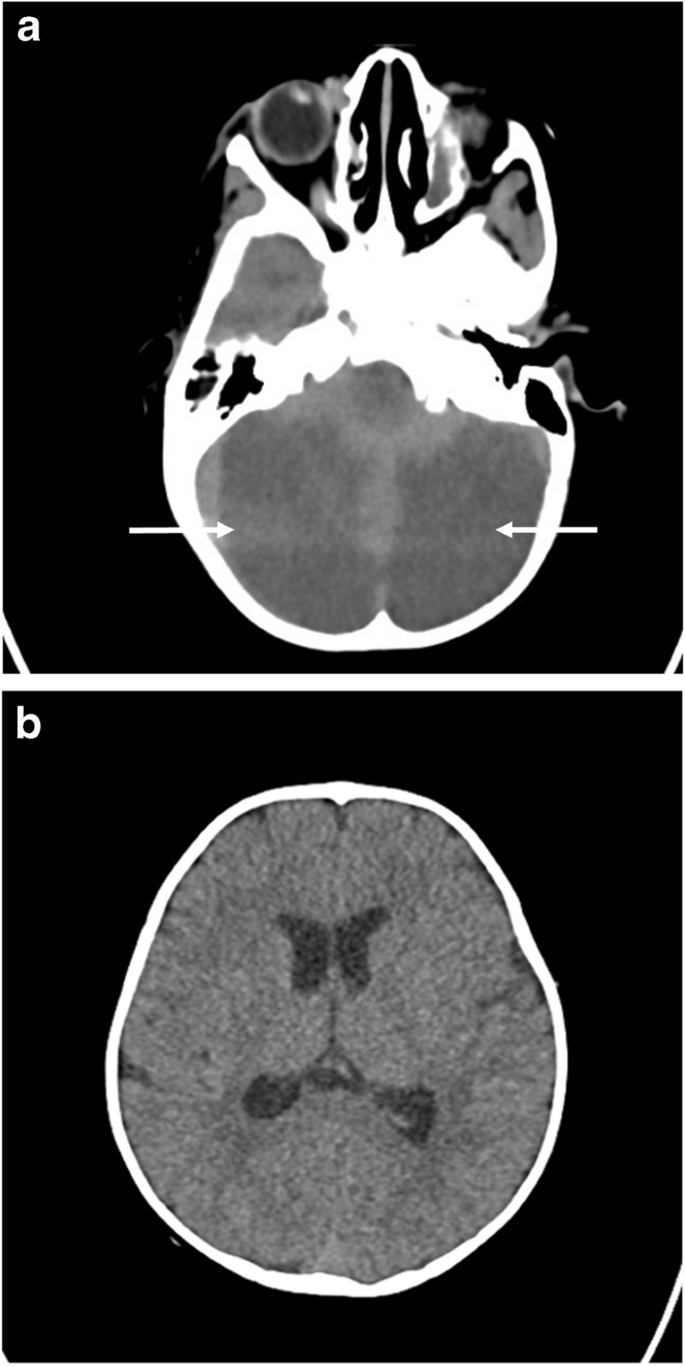

A 2-year-old female was found unconscious in her home for an unknown length of time. Urine drug screen was positive for fentanyl and a respiratory panel was positive for influenza. Noncontrast head computed tomography (CT) performed at day of presentation showed diffuse hypodensity in the bilateral cerebellar hemispheres and early ventriculomegaly (Fig. 1 a, ab).

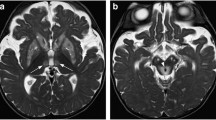

Two-year-old girl found unresponsive after fentanyl ingestion. a Axial noncontrast CT head at the level of the posterior fossa shows bilateral diffuse cerebellar hypodensity suggestive of diffuse edema or infarction. b Mild ventriculomegaly is noted at the level of the lateral ventricles

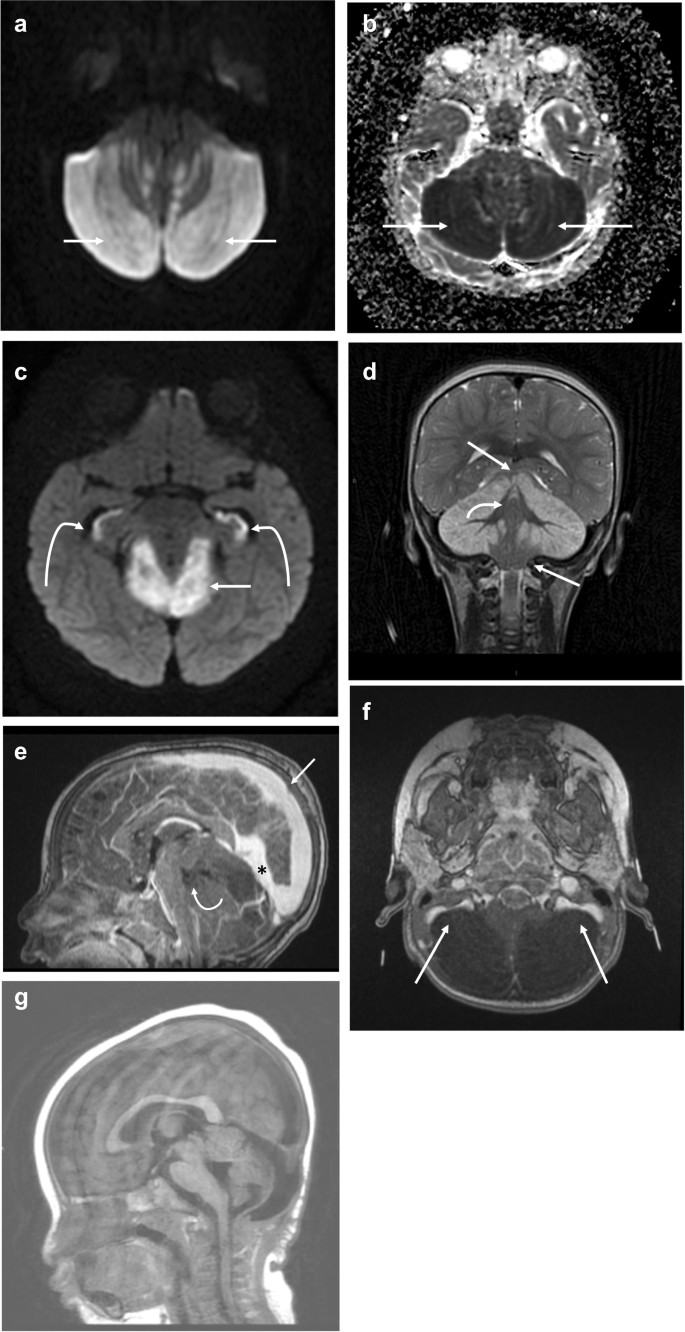

Subsequent brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed worsening of cerebellar edema, mass effect, and cerebellar herniation. There was bilateral restricted diffusion involving the cerebellum confirmed on apparent diffusion coefficient ADC map (Fig. 2 a and b). Bilateral restricted diffusion was also demonstrated separately within the hippocampus bilaterally (Fig. 2 c). Coronal T2 imaging demonstrated diffuse cerebellar edema with superior transtentorial herniation and downward tonsillar herniation at the level of the foramen magnum (Fig. 2 d). Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the brain was performed which showed normal caliber of the intracranial arteries, including the vertebral arteries at the skull base (not shown). However, there was proximal dural venous sinus distention due to bilateral sigmoid sinus compression from bilateral cerebellar edema (Fig. 2 e and f).

a Axial diffusion-weighted image (DWI) b1,000 s/mm 2 showing diffuse cerebellar restricted diffusion confirmed as profound decreased signal on ADC map ( b ). c Axial DWI shows symmetric hippocampal restricted diffusion (curved arrows). Superior transtentorial herniation with cerebellar cortical restricted diffusion (straight arrow). d T2-weighted coronal image shows diffuse cortical cerebellar hemispheric edema with superior transtentorial herniation and bilateral downward cerebellar tonsillar herniation (straight arrows). Notice relative sparing of edema in cerebellar vermis (curved arrow). e Sagittal contrast T1 midline image demonstrating severe brainstem compression. Notice severely dilated sagittal (arrow) and straight (*) dural sinuses and compression of fourth ventricle (curved arrow). f Axial contrast T1 image at the level of the medulla confirming symmetric bilateral sigmoid sinus compression (arrows). g Follow-up T2 axial image obtained 2 months after initial presentation shows bilateral cerebellar encephalomalacia

Following MRI, the patient was emergently taken to the operating room for suboccipital decompressive craniectomy including C1 laminectomy. Postoperatively, the patient’s neurological exam gradually improved as she awoke and became progressively more alert. One month after presentation, the patient was discharged to rehabilitation moving both upper extremities without difficulty but had decreased movement of the bilateral lower extremities. Follow-up imaging at 2 months demonstrated resolution of cerebellar edema, with resultant bilateral cerebellar encephalomalacia (Fig. 2 g). At 10 months after initial presentation, the patient was able to ambulate independently and had neurologically recovered.

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reports that in 2021 alone, more than 80,000 people died of an opioid overdose [ 3 ]. It is reported that thousands of infants are born each year with opioid withdrawal. Furthermore, toddlers are ingesting caregiver’s medications and children and adolescents are prescribed opioids leading to addictions [ 4 ]. The most common place for a pediatric opioid death is in the household and most of these deaths are unintentional. The most common drugs implicated in pediatric overdose deaths were prescription opioids [ 4 ]. While the increasing toll of opioid addiction is often discussed among adults, the pediatric population has become a significant victim of the epidemic.

A spectrum of opioid toxicity–related syndromes has been described in the literature. These include CHANTER syndrome, pediatric opioid use-associated neurotoxicity with cerebellar edema (POUNCE) syndrome, heroin-associated spongiform leukoencephalopathy (also known as “chasing the dragon leukoencephalopathy”), and opioid-associated amnestic syndrome (OAA). While all these toxidromes share many similarities, they can be distinguished from one another by differences on imaging.

POUNCE syndrome has previously been described in children accidentally exposed to opioids who presented with altered mental status [ 5 ]. On imaging, malignant cerebellar edema is a prominent finding which often results in obstructive hydrocephalus similar to CHANTER syndrome. POUNCE syndrome is not associated with involvement of the hippocampi and basal ganglia, unlike CHANTER syndrome (as seen in our case). POUNCE syndrome is characterized by its predilection for white matter with areas of hypoattenuation on CT, and T2 hyperintense lesions on MRI [ 1 ]. Similar cases of accidental pediatric overdoses with subsequent cerebral edema have also shown a pattern of leukoencephalopathy rather than hippocampal and basal ganglia injury [ 6 , 7 ]. This is hypothesized to be due to differing distribution and predominance of opiate receptors between adults and children [ 8 ].

Clinically, pediatric opioid intoxication manifests similarly to adults. The most common presenting symptoms include drowsiness, vomiting, respiratory depression, miosis, agitation, and tachycardia [ 9 ]. Opioid overdose in children differs from the adult population in that there can be a delayed onset of toxicity, unexpectedly severe poisoning, and prolonged toxic effects. These can be attributed to the fact that children have differing rates of drug absorption and differing metabolisms, and drugs may distribute more easily into the central nervous system of children [ 10 ]. Furthermore, children often ingest higher doses than adults per kilogram of body weight and are less likely to have any opioid tolerance [ 11 ].

Diffuse cerebellar edema with restricted diffusion and crowding of the fourth ventricle are hallmark imaging findings of CHANTER syndrome [ 12 ]. This pattern of restricted diffusion was found in our 2-year-old patient after a fentanyl overdose, who presented with cerebellar edema and fourth ventricular compression. Vascular imaging ruled out arterial occlusion as the etiology of cerebellar edema and the patient’s history of fentanyl consumption made CHANTER syndrome the likely diagnosis. Fortunately, the patient did not further suffer from venous infarction, although there was imaging evidence of venous hypertension. Yet, we postulate that the deep ganglionic and hippocampal signal changes encountered in these patients are perhaps related to venous hypertension, which was potentially present in our case.

Conclusions

This case report presents a young child who was diagnosed with CHANTER syndrome and ultimately survived. With the use of opioids evermore increasing, identifying, diagnosing, and treating the various opioid toxidromes, especially in children, are of paramount importance. We hope that our case increases the awareness of this entity.

Atac MF, Vilanilam GK, Damalcheruvu PR et al (2023) Cerebellar, hippocampal, and basal nuclei transient edema with restricted diffusion (CHANTER) syndrome in the setting of opioid and phencyclidine use. Radiol Case Rep 18:3496–3500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radcr.2023.07.015

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Jasne AS, Alsherbini KH, Smith MS et al (2019) Cerebellar hippocampal and basal nuclei transient edema with restricted diffusion (CHANTER) syndrome. Neurocrit Care 31:288–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-018-00666-4

(2023) Opioid overdose. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/deaths/opioid-overdose.html . Accessed 26 Feb 2024

Gaither JR, Shabanova V, Leventhal JM (2018) US national trends in pediatric deaths from prescription and illicit opioids, 1999–2016. JAMA Netw Open 1:e186558. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6558

Kim DD, Prasad AN (2020) Clinical and radiologic features of pediatric opioid use-associated neurotoxicity with cerebellar edema (POUNCE) syndrome. Neurology 94:710–712. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009293

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Jasne AS, Alsherbini KA, Smith MS et al (2020) Response to “Malignant cerebella edema in three-year-old girl following accidental opioid ingestion and fentanyl administration.” Neuroradiol J 33:158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1971400920903106

Shrot S, Poretti A, Tucker EW et al (2017) Acute brain injury following illicit drug abuse in adolescent and young adult patients: spectrum of neuroimaging findings. Neuroradiol J 30:144–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1971400917691994

Zagon IS, Gibo DM, McLaughlin PJ (1990) Adult and developing human cerebella exhibit different profiles of opioid binding sites. Brain Res 523:62–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(90)91635-t

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lavonas EJ, Banner W, Bradt P et al (2013) Root causes, clinical effects, and outcomes of unintentional exposures to buprenorphine by young children. J Pediatr 163:1377–1383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.06.058 . e1–3

Boyer EW (2012) Management of opioid analgesic overdose. N Engl J Med 367:146–155. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1202561

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Stoecker WV, Madsen DE, Cole JG, Woolsey Z (2016) Boys at risk: fatal accidental fentanyl ingestions in children: analysis of cases reported to the FDA 2004–2013. Mo Med 113:476–479

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mallikarjun KS, Parsons MS, Nigogosyan Z et al (2022) Neuroimaging findings in CHANTER syndrome: a case series. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 43:1136–1141. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A7569

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Radiology, Temple University Hospital, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Robert A. Koenigsberg, Luke Ross, Jason Timmerman & Rithika Surineni

Saint Christopher’s Hospital for Children, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Robert A. Koenigsberg, Kara Breznak & Tina C. Loven

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Luke Ross .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest, additional information, publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Koenigsberg, R.A., Ross, L., Timmerman, J. et al. Case of pediatric cerebellar, hippocampal, and basal nuclei transient edema with restricted diffusion (CHANTER) syndrome in a 2-year-old girl. Pediatr Radiol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-024-05928-2

Download citation

Received : 02 October 2023

Revised : 05 April 2024

Accepted : 08 April 2024

Published : 17 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-024-05928-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cerebellar infarction

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

ACR President William T. Herrington, MD, FACR, Calls on Leaders to Mentor, Nominate Next Generation

The page you recommended will be added to the "what others are reading" feed on "My ACR".

The page you bookmarked will be added to the "my reading list" feed on "My ACR".

Please enter at least 3 characters

Derailing Case Blue

Stiff Soviet resistance thwarted Hitler’s plan in the south along the Eastern Front in the summer of 1942.

This article appears in: April 2020

By Pat McTaggart

After the brutal defensive fighting during the winter of 1941-1942, Adolf Hitler was ready for another round with the Russians. This time, his armies would strike south with the twin goals of conquering the Caucasus and its rich oil fields and taking the city of Stalingrad. As far back as July 1940, when the planning for the invasion of the Soviet Union began, those two objectives had been part of the overall plan.

The unexpected Soviet resistance in late 1941 put a hold on those plans, but they were still on Hitler’s mind even after his failure to take Moscow and Leningrad earlier in the year. The Germans needed oil, and the Caucasus would provide it. He also knew that controlling Stalingrad would mean the loss of a major industrial city and would also cut traffic on the southern portion of the Volga River.

It would be a massive operation, code-named Fall Blau (Case Blue), that involved two panzer armies, three infantry armies, and the 2nd Hungarian Army. The plan was to advance on a broad front stretching from the Sea of Azov to Kursk. In his Führer Directive 41 promulgated on April 12, 1942, Hitler laid out his goals for the southern part of the Soviet Union: “All available forces will be concentrated on the main operations in the southern sector, with the aim of destroying the enemy before the Don [River], in order to secure the Caucasian oil fields and the passes through the Caucasus Mountains themselves.”

Hitler also detailed how this was to be accomplished. “The purpose is, as already stated, to occupy the Caucasus Front by decisively attacking and destroying the Russian forces stationed in the Voronezh area to the south, west or north of the Don … individual breaches of the front should take the form of close pincer movements. We must avoid closing the pincers too late, thus giving the enemy the possibility of avoiding destruction.”

In general, Hitler planned to take the city of Voronezh with a combined panzer-infantry assault and destroy Soviet forces there, giving him a bridgehead on the eastern bank of the Voronezh River, a tributary of the Don. The Führer Directive continued: “Armored and motorized formations are to continue the attack south from Voronezh, with their left flank on the Don River in support of a second breakthrough to take place from the general area east of Kharkov. Here too, the objective is not simply to break the Russian front, but in cooperation with the motorized forces thrusting down the Don, to destroy the enemy armies.”

It sounded simple. Voronezh would be taken quickly, and with that accomplished, the armored and mechanized forces would form the anvil behind the Soviet forces defending the approaches to the Volga River and Stalingrad. The German forces attacking from the east would be the hammer, and the Soviet armies caught between the two would be eliminated, depriving the Russians of vital troops needed to defend Stalingrad and the Caucasus.

The force tasked with taking Voronezh was Army Group von Weichs under the command of General Maximilian Freiherr von Weichs an dem Glon, who was also the commander of the 2nd German Army. The 2nd Army consisted of General Erwin Vierow’s LV Army Corps (45th, 95th, and 299th Infantry Divisions, and the 1st SS Brigade). Army Group von Weichs’ armored fist was General Hermann Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army. Hoth had three corps: General Erich Straube’s XIII (82nd and 385th Infantry and 11th Panzer Divisions), General Willibald Freiherr von Langermann und Erlankamp’s XXIV Panzer (377th Infantry, 9th Panzer, and 3rd Motorized Divisions), and General Werner Kempf’s XLVIII Panzer (24th Panzer and the Gross Deutschland, or Motorized Division).

During the coming operation, some of these divisions would be transferred back and forth between corps as needed. Other divisions would be added to the attack as it continued.

General Gustav Jany’s 2nd Hungarian Army, consisting of two corps, was also under von Weichs’ command. As a reserve force, von Weichs could count on four infantry divisions. General Wolfram von Richthofen (a cousin of the Red Baron of World War I fame) would provide air support with his VIII Air Corps.

Facing von Weichs was Lt. Gen. Filipp Ivanovich Golikov’s Briansk Front. Golikov had an impressive force under his command consisting of three infantry armies and one tank army with 19 rifle divisions, seven rifle brigades, six mechanized brigades, and 30 tank brigades. Air support for the front would be under the control of Maj. Gen. Konstantin Nikolaevich Smirnov’s 2nd Air Army.

In conjunction with the planning of Case Blue, the Germans began an intelligence operation designed to keep Soviet eyes off the southern area of the front. The German offensive in 1941 had come dangerously close to taking its objective of Moscow, and the 2nd and 3rd Panzer Armies of Army Group Center were in almost the exact same positions they had occupied since mid-November. A German salient at Rzhev pointed like a dagger toward Moscow, and the Russians knew it would make a perfect jump-off point for another try at the Soviet capital.

Fall Kreml (Case Kremlin) was set up to play on Stalin’s fears about another assault on Moscow. A top-secret directive from Army Group Center sent out on May 29 stated, “The OHK [Oberkommando des Heeres, or German Army High Command] has ordered the earliest possible resumption of the attack on Moscow.”

Reconnaissance flights in the Moscow area were increased, and sealed maps of the Moscow sector were sent to the army group with orders that they would remain sealed until June 10. When they were opened, corps and divisional staffs began planning for the offensive, unaware that the entire operation was a ruse. Russian spies reported all this activity to Stavka (the Soviet high command), which began making plans to meet the attack that was expected to begin on August 1.

Stalin believed that the Germans, even after the losses they had taken in 1941, could possibly launch two simultaneous operations, one aimed at Moscow and the other directed at the Caucasus. Soviet reports state that he was more concerned about the one directed at Moscow and considered the other extremely unlikely. As late as June 26, Stalin still believed that Case Blue was mostly nonsense. In a telephone call to Golikov, he said that it “was something concocted by intelligence people.”

He must have had some doubts about his own convictions, however, as he ordered Golikov to plan an attack in the Orel area as a preemptive move, just in case the Germans were planning a southern offensive. The Soviet general was still fine-tuning his attack when the Germans struck.

The generals in Berlin were confident that Army Group von Weichs would accomplish its goals quickly and with little difficulty. Golikov’s forward troops defended an area crisscrossed by the Sosna River and its tributaries, as well as by ravines known as balkas. German planning had taken that into account, and if bridges were blown or fords were too heavily defended, engineers stationed just behind the front could be rushed forward to repair or build new bridges over which the advance could continue.

Dawn came early during the summer in southern Russia. The soldiers in forward Soviet positions noticed a thin mist rising from the ravines and hollows as the sky began to lighten at 2 am on June 28. Behind that mist, German reconnaissance units were already on the move, headed for the Russian line.

Suddenly, the western sky lit up as army, corps, and divisional artillery opened fire on Soviet positions. Shells whined over the heads of the attacking Germans, smashing enemy trenches and strongpoints before continuing eastward in a rolling barrage. Close behind the barrage, elements of von Richtofen’s VIII Air Corps rained down bombs on specific fortified strongpoints before heading east to strafe and bomb targets of opportunity and identified supply dumps and communications hubs.

The results were devastating. As the men of Brig. Gen. Walter Hörnlein’s Gross Deutschland Division advanced toward their first objective, the supposedly strongly fortified village of Dubrovka, they found nothing but carnage. The divisional history reported, “Dubrovka itself has been flattened—wreckage and ruins—not a house was left standing, not a fence, only smoking timbers and smoldering rubble.”

The men moved on. A key objective was the capture of bridges crossing the Tim River. Infantrymen of Lt. Col. Ludwig Kohlhaas’s 3rd Battalion, 2nd Infantry Regiment, Gross Deutschland Division sliced through the battered Soviet defenses and reached the narrow river by 6 am. Although the road bridge crossing the river had been destroyed, a rail bridge still stood. Men of Kohlhaas’s 11th Company speedily crossed the bridge and drove defending Russians on the eastern bank out of their positions.

At the height of its success, the 11th was mistakenly attacked by the Luftwaffe, causing several casualties. Kohlhaas was wounded in the attack and had to turn command of the battalion over to a subordinate. He was awarded the Knight’s Cross on November 22 for his actions, just nine days before he was killed in combat.

It was the same all along von Weichs’ front. The speedy advance of the German forward units captured several crossings that were needed for the armored onslaught that would soon follow. The engineers that followed in the wake of the first wave strengthened bridges to support the panzers and built crossing points across the numerous balkas in the area.

As news of the successes of the forward elements reached higher headquarters, Hoth prepared to launch his armored fist. Von Langermann’s XXIV Panzer Corps had approximately 350 tanks, while Kempf’s XLVIII Panzer Corps had about 325. Together, the two corps were to strike the boundary of Lt. Gen. Mikhail Artemevich Pasegov’s 40th Army and Maj. Gen. Nikolai Pavlovich Pukhov’s 13th Army.

The forward positions of Pasegov’s army were defended by five infantry divisions (45th, 62nd, 121st, 160th, and 212th), with the 6th Rifle Division and three rifle brigades farther to the rear. His armor included the 14th and 170th Tank Brigades with a total of about 70 tanks and Maj. Gen. Mikhail Ivanovich Pavelkin’s 16th Tank Corps with about 180 tanks.

Pukhov had four rifle divisions (15th, 132nd, 143rd, and 148th) at the front and the 307th Rifle Division and a rifle brigade in reserve. The 13th Army’s armored force consisted of the 129th Tank Brigade with some 40 tanks and Maj. Gen. Mikhail Efimovich Katukov’s 1st Tank Corps, which was also the front reserve, containing about 170 tanks.

At 10 am, the order came: “Panzer Marsch.” Von Langermann and Kempf rolled forward toward the crossings that had been built or captured. The Russians facing them were in disarray for the most part. Having been pummeled by artillery and bombed and strafed by the Luftwaffe, many defensive positions had simply disappeared. Communications lines had been severed, leaving higher headquarters out of contact with subordinate units, and even company commanders had a hard time communicating with their sub-units.

“We were confident of victory,” wrote Colonel Maximilian Reichsfreiherr von Edelsheim, commander of the 24th Panzer’s 26th Rifle Regiment. In a 1986 letter to the author, he described the scene: “My unit followed close behind the panzers of the 24th Panzer Regiment. Great clouds of dust arose as we pushed forward. To our left and right, similar clouds were raised by other panzer or mechanized units. It seemed like nothing could stop us. We were to find out differently later on, but this day was ours.”

Lieutenant Georg Köhler was in von Edelsheim’s 3rd Company. Ten years before his death in 2006, he wrote to the author concerning the advance: “My men were in a fine mood. Our morale was high. The engineers and other forward elements of the division had done their work well, and we had few problems in crossing the ravines and streams in front of us. As we advanced, we could see clouds of dust rising on our left. It was the bulk of the Gross Deutschland Division moving forward.”

Kempf’s two divisions headed at full speed toward the Tim River, where they slammed into Colonel Mikhail Borisovich Anashkin’s 160th Rifle Division and the neighboring 212th Rifle Division, which were stationed along the western bank north and south of the city of Tim. Not yet recovered from the morning barrage, the Russian defenders were easily overcome, and the panzers continued to race to the southwest.

North of Kempf, von Langermann’s corps also had great success. Brig. Gen. Hermann Balck’s 11th Panzer Division, after crossing the Tim, smashed into Colonel Afanasii Nikitovich Slyshkin’s 15th Rifle Division, shattering its defenses and sending survivors fleeing toward the rear. To Balck’s right, Maj. Gen. Petr Maksimovich Zykov’s 121st Rifle Division met the same fate at the hands of Brig. Gen. Johannes Baessler’s 9th Panzer Division. The first day had lived up to expectations: the panzers were headed to Voronezh, and it seemed that the great envelopment intended to destroy Russian forces west of the Don would proceed as scheduled.

Parsegov reported by radio to Briansk Front headquarters. He told Golikov that the 40th Army had sustained “significant losses,” but, he reported, the army was still capable of combat. He also asked for tank reinforcements to counter the German panzers.

Golikov relayed the request to Stavka. In response, Maj. Gen. Pavelkin’s 16th Tank Corps (107th, 109th, and 164th Tank Brigades) and Maj. Gen. Nikolai Vladimirovich Feklenko’s 17th Tank Corps (66th, 67th, and 174th Tank Brigades and the 31st Mechanized Brigade) were ordered forward to the Kshen River. The 115th and 116th Tank Brigades were also pulled from the Briansk Front reserve and sent forward to bolster Parsegov’s forces.

In addition to those forces, Stavka ordered the Southern Front’s 4th Tank Corps (45th, 47th, and 102nd Tank Brigades and 4th Mechanized Brigade), commanded by Lt. Gen. Vasilii Aleksandrovich Mishulin, and Maj. Gen. Vasilii Mikhailovich Badanov’s 24th Tank Corps (54th and 130th Tank Brigades, 24th Mechanized Brigade, and 4th Guards) north to the Stary Oskol area. When they arrived at their destination, they were to prepare for a counterattack against an expected German attempt to capture the river crossing points near the town.

During the early hours of June 29, it began to rain. It soon turned into a downpour with lightning illuminating the steppe. Throughout the morning, Hoth’s panzers and motorized troops struggled to advance on dirt roads and paths that had suddenly turned to mud. Wachtmeister Siegfried Freyer was in 4th Battalion, Panzer Regiment 24. “We could get little traction for the panzers, because the mud clung to our tracks,” he remembered. “The panzer would slide this way and that way, and it was hard to keep any kind of formation. The engines were also overworked as we tried to move forward in that slime.”

At around 11 am, the rain stopped and the sun came out, its fiery heat quickly drying the sodden ground. By 1 pm, Hoth’s troops were moving forward again at full speed. With Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers swarming overhead and German artillery blasting Soviet defenses, the 11th Panzer reached the banks of the Kshen River about 10 kilometers west of Volavo. Farther north, German infantry was pushing the Russians back toward Livny.

Upon reaching the Kshen, the 11th Panzer ran into Pavelkin’s 16th Tank Corps, which was arriving piecemeal in the area. Since the Soviets did not yet have a force strong enough to counter the Germans, they retreated to await reinforcements. South of Balck, the 9th Panzer was probing 40th Army defenses situated on the eastern bank of the Kshen.

Kempf’s XLVIII Panzer Corps was also making good progress. The Gross Deutschland and 24th Panzer crossed the Kshen and established bridgeheads about 40 kilometers south of the 11th Panzer, with the Gross Deutschland advancing 47 kilometers for the day.

To the Gross Deutschland’s right, Brig. Gen. Bruno Hauenschild had pushed elements of his 24th Panzer across the Kshen bridgehead and hit Maj. Gen. Mikhail Danilovich Grishin’s 6th Rifle Division, which was scattered after a short, sharp fight. As night fell, an advance unit of the division entered the village of Bykovo.

A cluster of trucks was near one of the houses, and upon entering the building, the Germans found maps and documents relating to the Soviet defenses. The Germans had just missed capturing the headquarters staff of the 40th Army. Although the staff had escaped, the material left behind was an intelligence boon. Furthermore, Pasegov had lost command and control over his army, which would be of great help to the Germans in the coming days.

While German forces were battering the 40th Army, General Jany was having a more difficult time as the 2nd Hungarian Army tried to push its way through the Soviet defenses south of the town of Tim. Colonel Vasilii Pavlovich Sokolov’s 45th Rifle Division resisted all attempts by the Hungarians to breach its line. On Sokolov’s flanks, the 212th and 62nd Rifle Divisions also held their own. Soviet resistance also increased on Parsegov’s right flank as Maj. Gen. Nikolai Pavlovich Pukhov’s 13th Army, reinforced by Katukov’s 1st Tank Corps, occupied positions on von Langermann’s left flank.

Late on the 29th, the 1st and 16th Tank Corps launched an attack on the 11th Panzer Division. Although supported by infantry, the attack was poorly coordinated, and the 11th easily repulsed it. The failure showed that the Russians still had quite a way to go when it came to using combined forces and armor en masse.

Undeterred, Stalin directed Golikov to plan another armored attack for the next day. The operation was to use the 1st, 4th, 16th, 17th, and 24th Tank Corps in an effort to halt the German advance and restore a proper defensive line. Soviet forces would have an approximate 2-to-1 advantage in tanks over their German opponents for the attack. Instead of a decisive action, however, it turned into another debacle during the next few days.

Katukov’s 1st Tank Corps hit Balck’s 11th Panzer once again, and once again the assault was plagued by poor command and control between the corps’ subordinate brigades. The same could be said for Pavelkin’s 16th Tank Corps, which attacked the lead elements of Balck’s division. Ultimately, Pavelkin’s surviving tanks were forced to retreat across the Olym River, where they tried to regroup with the remnants of Katukov’s corps.

The 4th and 17th Tank Corps went up against the Gross Deutschland and 24th Panzer Divisions. Mishulin’s 4th Tank Corps met the 14th Panzer 10 kilometers south of Gorshechnoye, about 62 kilometers southwest of Voronezh. With his corps strung out, Mishulin had only two of his four brigades at his immediate disposal. They were easily defeated by Hauenschild’s panzers.

“Tank after tank exploded under our shells,” Wachmeister Freyer recalled. “To us it seemed suicidal, but the Ivans still came. It was almost like practice on the firing range as we destroyed the enemy armor.”

To make things worse, Badanov’s 24th Tank Corps was nowhere to be found on the field of battle. His forces were still assembling at Stary Oskol, about 12 kilometers southwest of Gorshechnoye. Although he must have heard the sounds of battle, he did not have sufficient forces in the area to commit them to the fight.

Meanwhile, Feklenko proved to be an utter failure. He could have joined the battle if he had attacked from Kastornoye, about 16 kilometers away. Instead, he moved his units to and fro, effectively scattering his brigades. With communication between himself and his brigades disintegrating, the 17th proved easy pickings for German combat groups. The 17th was decimated, losing more than three-quarters of its 179 tanks. Feklenko was relieved of his command on July 1.

While the armored battle in the north ran its course, General Paulus launched his 6th Army’s assault against Marshal Semen Konstantinovich Timoshenko’s Southwest Front. This was the southern pincer of the opening phase of Case Blue. Although the attack had to be postponed a day because of heavy rain, Paulus’s troops made good progress in most places on June 30. Swinging his corps to the northeast, he was well on his way to link up with von Weichs’ forces. When the connection was made, it would effectively surround Soviet forces south of Voronezh and deprive the Russians of much needed troops to defend the eastern bank of the Don.

The combination of the defeat of Golikov’s tank corps and the opening of Paulus’s offensive convinced Stavka to order Parsegov’s 40th Army and two of Timoshenko’s armies, the 21st (Maj. Gen. Alexi Ilyich Danilov) and the 28th (Lt. Gen. Dmitrii Ivanovich Riabyshev) to retreat from their perilous positions to a new defensive line along the Olym and Oskol Rivers. Beginning at dawn on July 2, the Soviet armies attempted to pull back under a hail of German artillery fire. The VIII Air Corps, now commanded by Maj. Gen. Martin Fiebig, added to the chaotic retreat as it strafed and bombed the Russian columns.

The Germans kept up their pursuit. At Gorshechnoye, the Gross Deutschland captured the village after a fight that left 51 Soviet tanks destroyed. On Hörnlein’s right flank, the 24th Panzer also kept up the pressure. It seemed that the first phase of Case Blue would be a success.

Stavka’s hope of establishing its new defensive line was shattered as German troops crossed the Oskol River. It was now evident that the paramount Soviet objective should be to get as many troops as possible across the Don River.

While things seemed to be going well for the Germans in von Weichs’ southern sector, Pushkov’s 13th Army was putting up a tougher fight north of Voronezh. Golikov now had his headquarters inside the city, and he was determined to hold it. To bolster Pushkov’s defenses, he had Colonel Sarkis Sogomanovich Martirosian’s 340th Rifle Division, the 1st Guards Rifle Division, two tank brigades, and Colonel Ivan Fedorovich Lunev’s 8th Cavalry Corps (21st and 112th Cavalry Divisions) move forward to reinforce him.

Stalin was also determined to hold Voronezh. With his armies south of the city crumbling, the city’s rail hub and the railway lines east of the city running to the southeast became increasingly important. If a new line could be formed behind the Don or the Voronezh Rivers, those tracks would be vital in moving supplies and troops to endangered areas in the south.