How to Write a Critical Essay

Hill Street Studios / Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

Olivia Valdes was the Associate Editorial Director for ThoughtCo. She worked with Dotdash Meredith from 2017 to 2021.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Olivia-Valdes_WEB1-1e405fc799d9474e9212215c4f21b141.jpg)

- B.A., American Studies, Yale University

A critical essay is a form of academic writing that analyzes, interprets, and/or evaluates a text. In a critical essay, an author makes a claim about how particular ideas or themes are conveyed in a text, then supports that claim with evidence from primary and/or secondary sources.

In casual conversation, we often associate the word "critical" with a negative perspective. However, in the context of a critical essay, the word "critical" simply means discerning and analytical. Critical essays analyze and evaluate the meaning and significance of a text, rather than making a judgment about its content or quality.

What Makes an Essay "Critical"?

Imagine you've just watched the movie "Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory." If you were chatting with friends in the movie theater lobby, you might say something like, "Charlie was so lucky to find a Golden Ticket. That ticket changed his life." A friend might reply, "Yeah, but Willy Wonka shouldn't have let those raucous kids into his chocolate factory in the first place. They caused a big mess."

These comments make for an enjoyable conversation, but they do not belong in a critical essay. Why? Because they respond to (and pass judgment on) the raw content of the movie, rather than analyzing its themes or how the director conveyed those themes.

On the other hand, a critical essay about "Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory" might take the following topic as its thesis: "In 'Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory,' director Mel Stuart intertwines money and morality through his depiction of children: the angelic appearance of Charlie Bucket, a good-hearted boy of modest means, is sharply contrasted against the physically grotesque portrayal of the wealthy, and thus immoral, children."

This thesis includes a claim about the themes of the film, what the director seems to be saying about those themes, and what techniques the director employs in order to communicate his message. In addition, this thesis is both supportable and disputable using evidence from the film itself, which means it's a strong central argument for a critical essay .

Characteristics of a Critical Essay

Critical essays are written across many academic disciplines and can have wide-ranging textual subjects: films, novels, poetry, video games, visual art, and more. However, despite their diverse subject matter, all critical essays share the following characteristics.

- Central claim . All critical essays contain a central claim about the text. This argument is typically expressed at the beginning of the essay in a thesis statement , then supported with evidence in each body paragraph. Some critical essays bolster their argument even further by including potential counterarguments, then using evidence to dispute them.

- Evidence . The central claim of a critical essay must be supported by evidence. In many critical essays, most of the evidence comes in the form of textual support: particular details from the text (dialogue, descriptions, word choice, structure, imagery, et cetera) that bolster the argument. Critical essays may also include evidence from secondary sources, often scholarly works that support or strengthen the main argument.

- Conclusion . After making a claim and supporting it with evidence, critical essays offer a succinct conclusion. The conclusion summarizes the trajectory of the essay's argument and emphasizes the essays' most important insights.

Tips for Writing a Critical Essay

Writing a critical essay requires rigorous analysis and a meticulous argument-building process. If you're struggling with a critical essay assignment, these tips will help you get started.

- Practice active reading strategies . These strategies for staying focused and retaining information will help you identify specific details in the text that will serve as evidence for your main argument. Active reading is an essential skill, especially if you're writing a critical essay for a literature class.

- Read example essays . If you're unfamiliar with critical essays as a form, writing one is going to be extremely challenging. Before you dive into the writing process, read a variety of published critical essays, paying careful attention to their structure and writing style. (As always, remember that paraphrasing an author's ideas without proper attribution is a form of plagiarism .)

- Resist the urge to summarize . Critical essays should consist of your own analysis and interpretation of a text, not a summary of the text in general. If you find yourself writing lengthy plot or character descriptions, pause and consider whether these summaries are in the service of your main argument or whether they are simply taking up space.

- 100 Persuasive Essay Topics

- Null Hypothesis Examples

- An Introduction to Academic Writing

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

- The Ultimate Guide to the 5-Paragraph Essay

- How To Write an Essay

- Critical Analysis in Composition

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- What an Essay Is and How to Write One

- How to Write and Format an MBA Essay

- Higher Level Thinking: Synthesis in Bloom's Taxonomy

- How To Write a Top-Scoring ACT Essay for the Enhanced Writing Test

- What Is a Critique in Composition?

- How to Structure an Essay

- How to Write a Solid Thesis Statement

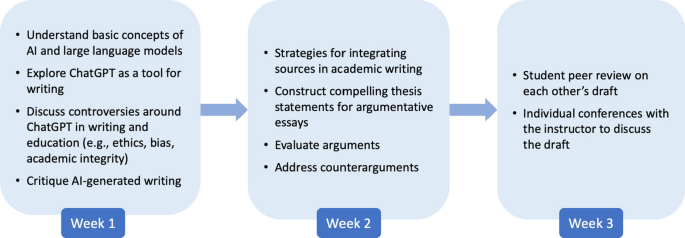

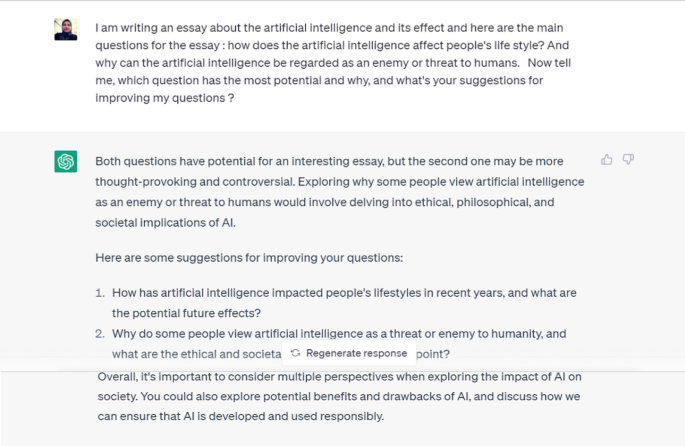

8 Effective Strategies to Write Argumentative Essays

In a bustling university town, there lived a student named Alex. Popular for creativity and wit, one challenge seemed insurmountable for Alex– the dreaded argumentative essay!

One gloomy afternoon, as the rain tapped against the window pane, Alex sat at his cluttered desk, staring at a blank document on the computer screen. The assignment loomed large: a 350-600-word argumentative essay on a topic of their choice . With a sigh, he decided to seek help of mentor, Professor Mitchell, who was known for his passion for writing.

Entering Professor Mitchell’s office was like stepping into a treasure of knowledge. Bookshelves lined every wall, faint aroma of old manuscripts in the air and sticky notes over the wall. Alex took a deep breath and knocked on his door.

“Ah, Alex,” Professor Mitchell greeted with a warm smile. “What brings you here today?”

Alex confessed his struggles with the argumentative essay. After hearing his concerns, Professor Mitchell said, “Ah, the argumentative essay! Don’t worry, Let’s take a look at it together.” As he guided Alex to the corner shelf, Alex asked,

Table of Contents

“What is an Argumentative Essay?”

The professor replied, “An argumentative essay is a type of academic writing that presents a clear argument or a firm position on a contentious issue. Unlike other forms of essays, such as descriptive or narrative essays, these essays require you to take a stance, present evidence, and convince your audience of the validity of your viewpoint with supporting evidence. A well-crafted argumentative essay relies on concrete facts and supporting evidence rather than merely expressing the author’s personal opinions . Furthermore, these essays demand comprehensive research on the chosen topic and typically follows a structured format consisting of three primary sections: an introductory paragraph, three body paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph.”

He continued, “Argumentative essays are written in a wide range of subject areas, reflecting their applicability across disciplines. They are written in different subject areas like literature and philosophy, history, science and technology, political science, psychology, economics and so on.

Alex asked,

“When is an Argumentative Essay Written?”

The professor answered, “Argumentative essays are often assigned in academic settings, but they can also be written for various other purposes, such as editorials, opinion pieces, or blog posts. Some situations to write argumentative essays include:

1. Academic assignments

In school or college, teachers may assign argumentative essays as part of coursework. It help students to develop critical thinking and persuasive writing skills .

2. Debates and discussions

Argumentative essays can serve as the basis for debates or discussions in academic or competitive settings. Moreover, they provide a structured way to present and defend your viewpoint.

3. Opinion pieces

Newspapers, magazines, and online publications often feature opinion pieces that present an argument on a current issue or topic to influence public opinion.

4. Policy proposals

In government and policy-related fields, argumentative essays are used to propose and defend specific policy changes or solutions to societal problems.

5. Persuasive speeches

Before delivering a persuasive speech, it’s common to prepare an argumentative essay as a foundation for your presentation.

Regardless of the context, an argumentative essay should present a clear thesis statement , provide evidence and reasoning to support your position, address counterarguments, and conclude with a compelling summary of your main points. The goal is to persuade readers or listeners to accept your viewpoint or at least consider it seriously.”

Handing over a book, the professor continued, “Take a look on the elements or structure of an argumentative essay.”

Elements of an Argumentative Essay

An argumentative essay comprises five essential components:

Claim in argumentative writing is the central argument or viewpoint that the writer aims to establish and defend throughout the essay. A claim must assert your position on an issue and must be arguable. It can guide the entire argument.

2. Evidence

Evidence must consist of factual information, data, examples, or expert opinions that support the claim. Also, it lends credibility by strengthening the writer’s position.

3. Counterarguments

Presenting a counterclaim demonstrates fairness and awareness of alternative perspectives.

4. Rebuttal

After presenting the counterclaim, the writer refutes it by offering counterarguments or providing evidence that weakens the opposing viewpoint. It shows that the writer has considered multiple perspectives and is prepared to defend their position.

The format of an argumentative essay typically follows the structure to ensure clarity and effectiveness in presenting an argument.

How to Write An Argumentative Essay

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to write an argumentative essay:

1. Introduction

- Begin with a compelling sentence or question to grab the reader’s attention.

- Provide context for the issue, including relevant facts, statistics, or historical background.

- Provide a concise thesis statement to present your position on the topic.

2. Body Paragraphs (usually three or more)

- Start each paragraph with a clear and focused topic sentence that relates to your thesis statement.

- Furthermore, provide evidence and explain the facts, statistics, examples, expert opinions, and quotations from credible sources that supports your thesis.

- Use transition sentences to smoothly move from one point to the next.

3. Counterargument and Rebuttal

- Acknowledge opposing viewpoints or potential objections to your argument.

- Also, address these counterarguments with evidence and explain why they do not weaken your position.

4. Conclusion

- Restate your thesis statement and summarize the key points you’ve made in the body of the essay.

- Leave the reader with a final thought, call to action, or broader implication related to the topic.

5. Citations and References

- Properly cite all the sources you use in your essay using a consistent citation style.

- Also, include a bibliography or works cited at the end of your essay.

6. Formatting and Style

- Follow any specific formatting guidelines provided by your instructor or institution.

- Use a professional and academic tone in your writing and edit your essay to avoid content, spelling and grammar mistakes .

Remember that the specific requirements for formatting an argumentative essay may vary depending on your instructor’s guidelines or the citation style you’re using (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago). Always check the assignment instructions or style guide for any additional requirements or variations in formatting.

Did you understand what Prof. Mitchell explained Alex? Check it now!

Fill the Details to Check Your Score

Prof. Mitchell continued, “An argumentative essay can adopt various approaches when dealing with opposing perspectives. It may offer a balanced presentation of both sides, providing equal weight to each, or it may advocate more strongly for one side while still acknowledging the existence of opposing views.” As Alex listened carefully to the Professor’s thoughts, his eyes fell on a page with examples of argumentative essay.

Example of an Argumentative Essay

Alex picked the book and read the example. It helped him to understand the concept. Furthermore, he could now connect better to the elements and steps of the essay which Prof. Mitchell had mentioned earlier. Aren’t you keen to know how an argumentative essay should be like? Here is an example of a well-crafted argumentative essay , which was read by Alex. After Alex finished reading the example, the professor turned the page and continued, “Check this page to know the importance of writing an argumentative essay in developing skills of an individual.”

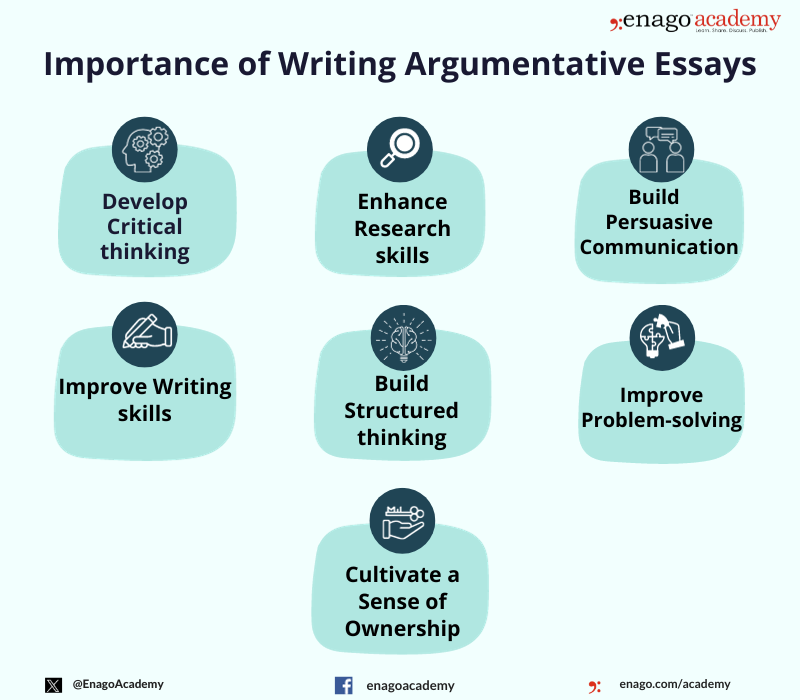

Importance of an Argumentative Essay

After understanding the benefits, Alex was convinced by the ability of the argumentative essays in advocating one’s beliefs and favor the author’s position. Alex asked,

“How are argumentative essays different from the other types?”

Prof. Mitchell answered, “Argumentative essays differ from other types of essays primarily in their purpose, structure, and approach in presenting information. Unlike expository essays, argumentative essays persuade the reader to adopt a particular point of view or take a specific action on a controversial issue. Furthermore, they differ from descriptive essays by not focusing vividly on describing a topic. Also, they are less engaging through storytelling as compared to the narrative essays.

Alex said, “Given the direct and persuasive nature of argumentative essays, can you suggest some strategies to write an effective argumentative essay?

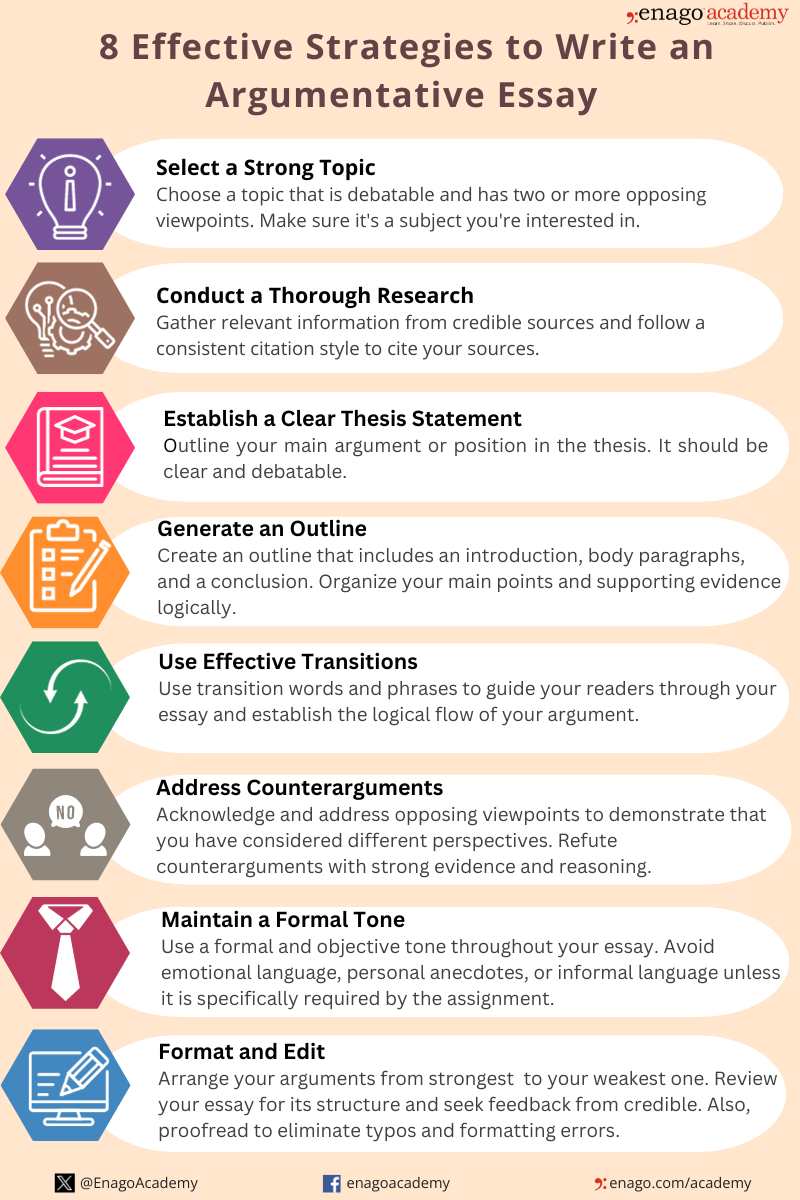

Turning the pages of the book, Prof. Mitchell replied, “Sure! You can check this infographic to get some tips for writing an argumentative essay.”

Effective Strategies to Write an Argumentative Essay

As days turned into weeks, Alex diligently worked on his essay. He researched, gathered evidence, and refined his thesis. It was a long and challenging journey, filled with countless drafts and revisions.

Finally, the day arrived when Alex submitted their essay. As he clicked the “Submit” button, a sense of accomplishment washed over him. He realized that the argumentative essay, while challenging, had improved his critical thinking and transformed him into a more confident writer. Furthermore, Alex received feedback from his professor, a mix of praise and constructive criticism. It was a humbling experience, a reminder that every journey has its obstacles and opportunities for growth.

Frequently Asked Questions

An argumentative essay can be written as follows- 1. Choose a Topic 2. Research and Collect Evidences 3. Develop a Clear Thesis Statement 4. Outline Your Essay- Introduction, Body Paragraphs and Conclusion 5. Revise and Edit 6. Format and Cite Sources 7. Final Review

One must choose a clear, concise and specific statement as a claim. It must be debatable and establish your position. Avoid using ambiguous or unclear while making a claim. To strengthen your claim, address potential counterarguments or opposing viewpoints. Additionally, use persuasive language and rhetoric to make your claim more compelling

Starting an argument essay effectively is crucial to engage your readers and establish the context for your argument. Here’s how you can start an argument essay are: 1. Begin With an Engaging Hook 2. Provide Background Information 3. Present Your Thesis Statement 4. Briefly Outline Your Main 5. Establish Your Credibility

The key features of an argumentative essay are: 1. Clear and Specific Thesis Statement 2. Credible Evidence 3. Counterarguments 4. Structured Body Paragraph 5. Logical Flow 6. Use of Persuasive Techniques 7. Formal Language

An argumentative essay typically consists of the following main parts or sections: 1. Introduction 2. Body Paragraphs 3. Counterargument and Rebuttal 4. Conclusion 5. References (if applicable)

The main purpose of an argumentative essay is to persuade the reader to accept or agree with a particular viewpoint or position on a controversial or debatable topic. In other words, the primary goal of an argumentative essay is to convince the audience that the author's argument or thesis statement is valid, logical, and well-supported by evidence and reasoning.

Great article! The topic is simplified well! Keep up the good work

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Industry News

6 Reasons Why There is a Decline in Higher Education Enrollment: Action plan to overcome this crisis

Over the past decade, colleges and universities across the globe have witnessed a concerning trend…

- Reporting Research

Academic Essay Writing Made Simple: 4 types and tips

The pen is mightier than the sword, they say, and nowhere is this more evident…

![critical argumentative essay What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

- AI in Academia

AI vs. AI: How to detect image manipulation and avoid academic misconduct

The scientific community is facing a new frontier of controversy as artificial intelligence (AI) is…

- Publishing News

Unified AI Guidelines Crucial as Academic Writing Embraces Generative Tools

As generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools like ChatGPT are advancing at an accelerating pace, their…

How to Effectively Cite a PDF (APA, MLA, AMA, and Chicago Style)

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

How to Improve Lab Report Writing: Best practices to follow with and without…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

Argumentative Essay Examples to Inspire You (+ Free Formula)

.webp)

Table of contents

Meredith Sell

Have you ever been asked to explain your opinion on a controversial issue?

- Maybe your family got into a discussion about chemical pesticides

- Someone at work argues against investing resources into your project

- Your partner thinks intermittent fasting is the best way to lose weight and you disagree

Proving your point in an argumentative essay can be challenging, unless you are using a proven formula.

Argumentative essay formula & example

In the image below, you can see a recommended structure for argumentative essays. It starts with the topic sentence, which establishes the main idea of the essay. Next, this hypothesis is developed in the development stage. Then, the rebuttal, or the refutal of the main counter argument or arguments. Then, again, development of the rebuttal. This is followed by an example, and ends with a summary. This is a very basic structure, but it gives you a bird-eye-view of how a proper argumentative essay can be built.

Writing an argumentative essay (for a class, a news outlet, or just for fun) can help you improve your understanding of an issue and sharpen your thinking on the matter. Using researched facts and data, you can explain why you or others think the way you do, even while other reasonable people disagree.

Free AI argumentative essay generator > Free AI argumentative essay generator >

What Is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative essay is an explanatory essay that takes a side.

Instead of appealing to emotion and personal experience to change the reader’s mind, an argumentative essay uses logic and well-researched factual information to explain why the thesis in question is the most reasonable opinion on the matter.

Over several paragraphs or pages, the author systematically walks through:

- The opposition (and supporting evidence)

- The chosen thesis (and its supporting evidence)

At the end, the author leaves the decision up to the reader, trusting that the case they’ve made will do the work of changing the reader’s mind. Even if the reader’s opinion doesn’t change, they come away from the essay with a greater understanding of the perspective presented — and perhaps a better understanding of their original opinion.

All of that might make it seem like writing an argumentative essay is way harder than an emotionally-driven persuasive essay — but if you’re like me and much more comfortable spouting facts and figures than making impassioned pleas, you may find that an argumentative essay is easier to write.

Plus, the process of researching an argumentative essay means you can check your assumptions and develop an opinion that’s more based in reality than what you originally thought. I know for sure that my opinions need to be fact checked — don’t yours?

So how exactly do we write the argumentative essay?

How do you start an argumentative essay

First, gain a clear understanding of what exactly an argumentative essay is. To formulate a proper topic sentence, you have to be clear on your topic, and to explore it through research.

Students have difficulty starting an essay because the whole task seems intimidating, and they are afraid of spending too much time on the topic sentence. Experienced writers, however, know that there is no set time to spend on figuring out your topic. It's a real exploration that is based to a large extent on intuition.

6 Steps to Write an Argumentative Essay (Persuasion Formula)

Use this checklist to tackle your essay one step at a time:

1. Research an issue with an arguable question

To start, you need to identify an issue that well-informed people have varying opinions on. Here, it’s helpful to think of one core topic and how it intersects with another (or several other) issues. That intersection is where hot takes and reasonable (or unreasonable) opinions abound.

I find it helpful to stage the issue as a question.

For example:

Is it better to legislate the minimum size of chicken enclosures or to outlaw the sale of eggs from chickens who don’t have enough space?

Should snow removal policies focus more on effectively keeping roads clear for traffic or the environmental impacts of snow removal methods?

Once you have your arguable question ready, start researching the basic facts and specific opinions and arguments on the issue. Do your best to stay focused on gathering information that is directly relevant to your topic. Depending on what your essay is for, you may reference academic studies, government reports, or newspaper articles.

Research your opposition and the facts that support their viewpoint as much as you research your own position . You’ll need to address your opposition in your essay, so you’ll want to know their argument from the inside out.

2. Choose a side based on your research

You likely started with an inclination toward one side or the other, but your research should ultimately shape your perspective. So once you’ve completed the research, nail down your opinion and start articulating the what and why of your take.

What: I think it’s better to outlaw selling eggs from chickens whose enclosures are too small.

Why: Because if you regulate the enclosure size directly, egg producers outside of the government’s jurisdiction could ship eggs into your territory and put nearby egg producers out of business by offering better prices because they don’t have the added cost of larger enclosures.

This is an early form of your thesis and the basic logic of your argument. You’ll want to iterate on this a few times and develop a one-sentence statement that sums up the thesis of your essay.

Thesis: Outlawing the sale of eggs from chickens with cramped living spaces is better for business than regulating the size of chicken enclosures.

Now that you’ve articulated your thesis , spell out the counterargument(s) as well. Putting your opposition’s take into words will help you throughout the rest of the essay-writing process. (You can start by choosing the counter argument option with Wordtune Spices .)

Counterargument: Outlawing the sale of eggs from chickens with too small enclosures will immediately drive up egg prices for consumers, making the low-cost protein source harder to afford — especially for low-income consumers.

There may be one main counterargument to articulate, or several. Write them all out and start thinking about how you’ll use evidence to address each of them or show why your argument is still the best option.

3. Organize the evidence — for your side and the opposition

You did all of that research for a reason. Now’s the time to use it.

Hopefully, you kept detailed notes in a document, complete with links and titles of all your source material. Go through your research document and copy the evidence for your argument and your opposition’s into another document.

List the main points of your argument. Then, below each point, paste the evidence that backs them up.

If you’re writing about chicken enclosures, maybe you found evidence that shows the spread of disease among birds kept in close quarters is worse than among birds who have more space. Or maybe you found information that says eggs from free-range chickens are more flavorful or nutritious. Put that information next to the appropriate part of your argument.

Repeat the process with your opposition’s argument: What information did you find that supports your opposition? Paste it beside your opposition’s argument.

You could also put information here that refutes your opposition, but organize it in a way that clearly tells you — at a glance — that the information disproves their point.

Counterargument: Outlawing the sale of eggs from chickens with too small enclosures will immediately drive up egg prices for consumers.

BUT: Sicknesses like avian flu spread more easily through small enclosures and could cause a shortage that would drive up egg prices naturally, so ensuring larger enclosures is still a better policy for consumers over the long term.

As you organize your research and see the evidence all together, start thinking through the best way to order your points.

Will it be better to present your argument all at once or to break it up with opposition claims you can quickly refute? Would some points set up other points well? Does a more complicated point require that the reader understands a simpler point first?

Play around and rearrange your notes to see how your essay might flow one way or another.

4. Freewrite or outline to think through your argument

Is your brain buzzing yet? At this point in the process, it can be helpful to take out a notebook or open a fresh document and dump whatever you’re thinking on the page.

Where should your essay start? What ground-level information do you need to provide your readers before you can dive into the issue?

Use your organized evidence document from step 3 to think through your argument from beginning to end, and determine the structure of your essay.

There are three typical structures for argumentative essays:

- Make your argument and tackle opposition claims one by one, as they come up in relation to the points of your argument - In this approach, the whole essay — from beginning to end — focuses on your argument, but as you make each point, you address the relevant opposition claims individually. This approach works well if your opposition’s views can be quickly explained and refuted and if they directly relate to specific points in your argument.

- Make the bulk of your argument, and then address the opposition all at once in a paragraph (or a few) - This approach puts the opposition in its own section, separate from your main argument. After you’ve made your case, with ample evidence to convince your readers, you write about the opposition, explaining their viewpoint and supporting evidence — and showing readers why the opposition’s argument is unconvincing. Once you’ve addressed the opposition, you write a conclusion that sums up why your argument is the better one.

- Open your essay by talking about the opposition and where it falls short. Build your entire argument to show how it is superior to that opposition - With this structure, you’re showing your readers “a better way” to address the issue. After opening your piece by showing how your opposition’s approaches fail, you launch into your argument, providing readers with ample evidence that backs you up.

As you think through your argument and examine your evidence document, consider which structure will serve your argument best. Sketch out an outline to give yourself a map to follow in the writing process. You could also rearrange your evidence document again to match your outline, so it will be easy to find what you need when you start writing.

5. Write your first draft

You have an outline and an organized document with all your points and evidence lined up and ready. Now you just have to write your essay.

In your first draft, focus on getting your ideas on the page. Your wording may not be perfect (whose is?), but you know what you’re trying to say — so even if you’re overly wordy and taking too much space to say what you need to say, put those words on the page.

Follow your outline, and draw from that evidence document to flesh out each point of your argument. Explain what the evidence means for your argument and your opposition. Connect the dots for your readers so they can follow you, point by point, and understand what you’re trying to say.

As you write, be sure to include:

1. Any background information your reader needs in order to understand the issue in question.

2. Evidence for both your argument and the counterargument(s). This shows that you’ve done your homework and builds trust with your reader, while also setting you up to make a more convincing argument. (If you find gaps in your research while you’re writing, Wordtune Spices can source statistics or historical facts on the fly!)

Get Wordtune for free > Get Wordtune for free >

3. A conclusion that sums up your overall argument and evidence — and leaves the reader with an understanding of the issue and its significance. This sort of conclusion brings your essay to a strong ending that doesn’t waste readers’ time, but actually adds value to your case.

6. Revise (with Wordtune)

The hard work is done: you have a first draft. Now, let’s fine tune your writing.

I like to step away from what I’ve written for a day (or at least a night of sleep) before attempting to revise. It helps me approach clunky phrases and rough transitions with fresh eyes. If you don’t have that luxury, just get away from your computer for a few minutes — use the bathroom, do some jumping jacks, eat an apple — and then come back and read through your piece.

As you revise, make sure you …

- Get the facts right. An argument with false evidence falls apart pretty quickly, so check your facts to make yours rock solid.

- Don’t misrepresent the opposition or their evidence. If someone who holds the opposing view reads your essay, they should affirm how you explain their side — even if they disagree with your rebuttal.

- Present a case that builds over the course of your essay, makes sense, and ends on a strong note. One point should naturally lead to the next. Your readers shouldn’t feel like you’re constantly changing subjects. You’re making a variety of points, but your argument should feel like a cohesive whole.

- Paraphrase sources and cite them appropriately. Did you skip citations when writing your first draft? No worries — you can add them now. And check that you don’t overly rely on quotations. (Need help paraphrasing? Wordtune can help. Simply highlight the sentence or phrase you want to adjust and sort through Wordtune’s suggestions.)

- Tighten up overly wordy explanations and sharpen any convoluted ideas. Wordtune makes a great sidekick for this too 😉

Words to start an argumentative essay

The best way to introduce a convincing argument is to provide a strong thesis statement . These are the words I usually use to start an argumentative essay:

- It is indisputable that the world today is facing a multitude of issues

- With the rise of ____, the potential to make a positive difference has never been more accessible

- It is essential that we take action now and tackle these issues head-on

- it is critical to understand the underlying causes of the problems standing before us

- Opponents of this idea claim

- Those who are against these ideas may say

- Some people may disagree with this idea

- Some people may say that ____, however

When refuting an opposing concept, use:

- These researchers have a point in thinking

- To a certain extent they are right

- After seeing this evidence, there is no way one can agree with this idea

- This argument is irrelevant to the topic

Are you convinced by your own argument yet? Ready to brave the next get-together where everyone’s talking like they know something about intermittent fasting , chicken enclosures , or snow removal policies?

Now if someone asks you to explain your evidence-based but controversial opinion, you can hand them your essay and ask them to report back after they’ve read it.

Share This Article:

.webp)

8 Key Elements of a Research Paper Structure + Free Template (2024)

.webp)

How to Craft Your Ideal Thesis Research Topic

How to Craft an Engaging Elevator Pitch that Gets Results

Looking for fresh content, thank you your submission has been received.

- Subject Guides

Academic writing: a practical guide

Criticality in academic writing.

- Academic writing

- The writing process

- Academic writing style

- Structure & cohesion

- Working with evidence

- Referencing

- Assessment & feedback

- Dissertations

- Reflective writing

- Examination writing

- Academic posters

- Feedback on Structure and Organisation

- Feedback on Argument, Analysis, and Critical Thinking

- Feedback on Writing Style and Clarity

- Feedback on Referencing and Research

- Feedback on Presentation and Proofreading

Being critical is at the heart of academic writing, but what is it and how can you incorporate it into your work?

What is criticality?

What is critical thinking.

Have you ever received feedback in a piece of work saying 'be more critical' or 'not enough critical analysis' but found yourself scratching your head, wondering what that means? Dive into this bitesize workshop to discover what it is and how to do it:

Critical Thinking: What it is and how to do it (bitesize workshop)[YouTube]

University-level work requires both descriptive and critical elements. But what's the difference?

Descriptive

Being descriptive shows what you know about a topic and provides the evidence to support your arguments. It uses simpler processes like remembering , understanding and applying . You might summarise previous research, explain concepts or describe processes.

Being critical pulls evidence together to build your arguments; what does it all mean together? It uses more complex processes: analysing , evaluating and creating . You might make comparisons, consider reasons and implications, justify choices or consider strengths and weaknesses.

Bloom's Taxonomy is a useful tool to consider descriptive and critical processes:

Bloom's Taxonomy [YouTube] | Bloom's Taxonomy [Google Doc]

Find out more about critical thinking:

What is critical writing?

Academic writing requires criticality; it's not enough to just describe or summarise evidence, you also need to analyse and evaluate information and use it to build your own arguments. This is where you show your own thoughts based on the evidence available, so critical writing is really important for higher grades.

Explore the key features of critical writing and see it in practice in some examples:

Introduction to critical writing [Google Slides]

While we need criticality in our writing, it's definitely possible to go further than needed. We’re aiming for that Goldilocks ‘just right’ point between not critical enough and too critical. Find out more:

Critical reading

Criticality isn't just for writing, it is also important to read critically. Reading critically helps you:

- evaluative whether sources are suitable for your assignments.

- know what you're looking for when reading.

- find the information you need quickly.

Critical reading [Interactive tutorial] | Critical reading [Google Doc]

Find out more on our dedicated guides:

Using evidence critically

Academic writing integrates evidence from sources to create your own critical arguments.

We're not looking for a list of summaries of individual sources; ideally, the important evidence should be integrated into a cohesive whole. What does the evidence mean altogether? Of course, a critical argument also needs some critical analysis of this evidence. What does it all mean in terms of your argument?

Find out more about using evidence to build critical arguments in our guide to working with evidence:

Critical language

Critical writing is going to require critical language. Different terms will give different nuance to your argument. Others will just keep things interesting! In the document below we go through some examples to help you out:

Assignment titles: critical or descriptive?

Assignment titles contain various words that show where you need to be descriptive and where you need to be critical. Explore some of the most common instructional words:

Descriptive instructional words

define : give the precise meaning

examine : look at carefully; consider different aspects

explain : clearly describe how a process works, why a decision was made, or give other information needed to understand the topic

illustrate : explain and describe using examples

outline : give an overview of the key information, leaving out minor details

Critical instructional words

analyse : break down the information into parts, consider how parts work together

discuss : explain a topic, make comparisons, consider strengths & weaknesses, give reasons, consider implications

evaluate : assess something's worth, value or suitability for a purpose - this often leads to making a choice afterwards

justify : show the reasoning behind a choice, argument or standpoint

synthesise : bring together evidence and information to create a cohesive whole, integrate ideas or issues

CC BY-NC-SA Learnhigher

More guidance on breaking down assignment titles:

- << Previous: Structure & cohesion

- Next: Working with evidence >>

- Last Updated: Jun 4, 2024 10:44 AM

- URL: https://subjectguides.york.ac.uk/academic-writing

Library Guides

Essay writing: argument and criticality.

- Argument and criticality

What is an argument?

Essays are generally structured as arguments .

After you analyse the essay question, you read (or re-read) texts from your reading list and texts found through your own research. On the basis of your reading, you develop a general view, or answer, to the essay question, which you then defend with the evidence found in your reading.

The view that you defend in your essay is called a thesis statement .

Thesis statements

What is a thesis statement ?

Your thesis statement states your position on the essay question, which you will defend with one or more arguments in the body of the essay. Your thesis statement is essentially your answer to the essay question, expressed in a single sentence, and will be based on your reading.

Your thesis statement is:

- Is developed through reading. What does the literature say about the issue referred to in the essay question?

- Provided in the introduction

- Usually follows a brief outline of the problem, or issue, addressed by the essay question

- Is specific and relevant to the essay question

Examples of thesis statements

Essay question: ‘Discuss the claim that mass public schooling provides equal access to high quality education.’

Thesis: This essay will argue that while the introduction of mass public schooling was a great advancement in ensuring equal access to education, the influence of socio-economic status on educational attainment has not yet been overcome.

"This essay will argue" → Signposting phrase to introduce your argument

"while mass public schooling was a great advancement in ensuring equal access to education, the influence of socio-economic status on educational attainment has not yet been overcome" → Clearly indicates your position on the issue

Example 2:

Essay question: To what extent is there a 'participation crisis' in UK politics?

Thesis: If we define 'participation' as xyz, it can be argued that there is not in fact a participation crisis in UK politics.

A note on thesis statements :

It can feel scary to commit yourself to a thesis statement because thesis statements seem to speak with tremendous certainty! But..."The influence of socio-economic status on educational attainment has not yet been overcome" simply indicates the general destination that the essay will be moving toward. It does not have to be a highly developed statement of how things are. Try to develop a general, 'working' thesis to give your writing direction. You can make it more precise and nuanced as you work through various drafts of your essay.

Additional help with thesis statements

Effective argumentation

To write an effective argument, you will need to provide the following:

- Thesis statement

- Evidence in the form of literature, data, research findings etc.

- Logic: the thesis statement must be supported logically by the evidence.

- Consideration of counter-arguments

- You can present concessions to counter-arguments, but should reject their key points with your evidence/reasoning.

- Confident whenever possible

- Cautious, qualifying, hedging, when there are uncertainties and limitations

Writing effective arguments

In defending your thesis statement, you will likely have to break it down into separate issues, or aspects, which are dealt with separately.

In discussing these separate aspects, you might develop smaller thesis statements, which are related to your larger thesis statement .

This means that your essay will have a "tree structure".

Essay tree structure

An example of a more developed tree structure:

Thesis: Digital technology will lead to greater social mistrust and dysfunctionality rather than greater social cohesion

The handout below looks at the difference between everyday arguments and arguments in academic writing:

- Academic vs. Everyday Arguments An analysis of the similarities and differences between academic arguments and everyday arguments

Argument structure

- The order and structure of an argument can vary

Claim: We should go to the cinema today.

Argument structure A:

1. Counter arguments/concessions:

It is true that…

Cinema is costly (topic 1)

It is hard to agree on a movie (topic 2)

Tomorrow we have lectures in the morning (topic 3)

2. Rebuttals with evidence:

But

We have saved money by working… (topic 1)

There is a new sci-fi movie that you should like and I’m finding quite intriguing... (topic 2)

We haven’t been out in a while and I need some

inspiration to study more efficiently... (topic 3)

Argument structure B:

1. Counterargument/concession plus rebuttal of topic 1

Cinema is costly, at £10 per ticket, but we have saved money by working…

2. Counterargument/concession plus rebuttal of t opic 2

It is hard to agree on a movie, but there is a new sci-fi movie that you should like and I’m finding quite intriguing..

3. Counterargument/concession plus rebuttal of t opic 3

Tomorrow we have lectures in the morning, but we haven’t been out in a while and I need some inspiration to study more efficiently

Obviously your academic writing will be more complex, will deal with more serious questions, will use evidence and will refer to the relevant academic literature!

Critical thinking and writing

Your essay needs to demonstrate some degree of analysis and critical thinking. The more you progress in higher education, the more you are expected to use and apply knowledge. This is reflected in critical writing , whereby you move from mere description to analysis and evaluation .

Critical thinking entails:

- Being objective

- Looking for weaknesses in arguments

- Checking arguments are logical

- Checking arguments are accurate

- Looking at an idea or data from different perspectives

It also involves asking questions about your own work as well as the work of others such as:

- Is this true?

- How reliable is this information?

- Can I support the arguments and claims I am making?

If you have ever been told that your writing is ‘too descriptive’ and not ‘critical’ enough then consider the differences between analytical writing and descriptive writing:

- Descriptive writing summarises, reports, lists and outlines information, theories and sources.

- Critical writing looks for links between sources, identifies issues, challenges established ideas and considers alternatives.

Check the guide on Critical Thinking and Writing for more information on writing critically.

- << Previous: Research

- Next: Structure >>

- Last Updated: Dec 12, 2023 2:36 PM

- URL: https://libguides.westminster.ac.uk/essaywriting

CONNECT WITH US

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, 3 strong argumentative essay examples, analyzed.

General Education

Need to defend your opinion on an issue? Argumentative essays are one of the most popular types of essays you’ll write in school. They combine persuasive arguments with fact-based research, and, when done well, can be powerful tools for making someone agree with your point of view. If you’re struggling to write an argumentative essay or just want to learn more about them, seeing examples can be a big help.

After giving an overview of this type of essay, we provide three argumentative essay examples. After each essay, we explain in-depth how the essay was structured, what worked, and where the essay could be improved. We end with tips for making your own argumentative essay as strong as possible.

What Is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative essay is an essay that uses evidence and facts to support the claim it’s making. Its purpose is to persuade the reader to agree with the argument being made.

A good argumentative essay will use facts and evidence to support the argument, rather than just the author’s thoughts and opinions. For example, say you wanted to write an argumentative essay stating that Charleston, SC is a great destination for families. You couldn’t just say that it’s a great place because you took your family there and enjoyed it. For it to be an argumentative essay, you need to have facts and data to support your argument, such as the number of child-friendly attractions in Charleston, special deals you can get with kids, and surveys of people who visited Charleston as a family and enjoyed it. The first argument is based entirely on feelings, whereas the second is based on evidence that can be proven.

The standard five paragraph format is common, but not required, for argumentative essays. These essays typically follow one of two formats: the Toulmin model or the Rogerian model.

- The Toulmin model is the most common. It begins with an introduction, follows with a thesis/claim, and gives data and evidence to support that claim. This style of essay also includes rebuttals of counterarguments.

- The Rogerian model analyzes two sides of an argument and reaches a conclusion after weighing the strengths and weaknesses of each.

3 Good Argumentative Essay Examples + Analysis

Below are three examples of argumentative essays, written by yours truly in my school days, as well as analysis of what each did well and where it could be improved.

Argumentative Essay Example 1

Proponents of this idea state that it will save local cities and towns money because libraries are expensive to maintain. They also believe it will encourage more people to read because they won’t have to travel to a library to get a book; they can simply click on what they want to read and read it from wherever they are. They could also access more materials because libraries won’t have to buy physical copies of books; they can simply rent out as many digital copies as they need.

However, it would be a serious mistake to replace libraries with tablets. First, digital books and resources are associated with less learning and more problems than print resources. A study done on tablet vs book reading found that people read 20-30% slower on tablets, retain 20% less information, and understand 10% less of what they read compared to people who read the same information in print. Additionally, staring too long at a screen has been shown to cause numerous health problems, including blurred vision, dizziness, dry eyes, headaches, and eye strain, at much higher instances than reading print does. People who use tablets and mobile devices excessively also have a higher incidence of more serious health issues such as fibromyalgia, shoulder and back pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, and muscle strain. I know that whenever I read from my e-reader for too long, my eyes begin to feel tired and my neck hurts. We should not add to these problems by giving people, especially young people, more reasons to look at screens.

Second, it is incredibly narrow-minded to assume that the only service libraries offer is book lending. Libraries have a multitude of benefits, and many are only available if the library has a physical location. Some of these benefits include acting as a quiet study space, giving people a way to converse with their neighbors, holding classes on a variety of topics, providing jobs, answering patron questions, and keeping the community connected. One neighborhood found that, after a local library instituted community events such as play times for toddlers and parents, job fairs for teenagers, and meeting spaces for senior citizens, over a third of residents reported feeling more connected to their community. Similarly, a Pew survey conducted in 2015 found that nearly two-thirds of American adults feel that closing their local library would have a major impact on their community. People see libraries as a way to connect with others and get their questions answered, benefits tablets can’t offer nearly as well or as easily.

While replacing libraries with tablets may seem like a simple solution, it would encourage people to spend even more time looking at digital screens, despite the myriad issues surrounding them. It would also end access to many of the benefits of libraries that people have come to rely on. In many areas, libraries are such an important part of the community network that they could never be replaced by a simple object.

The author begins by giving an overview of the counter-argument, then the thesis appears as the first sentence in the third paragraph. The essay then spends the rest of the paper dismantling the counter argument and showing why readers should believe the other side.

What this essay does well:

- Although it’s a bit unusual to have the thesis appear fairly far into the essay, it works because, once the thesis is stated, the rest of the essay focuses on supporting it since the counter-argument has already been discussed earlier in the paper.

- This essay includes numerous facts and cites studies to support its case. By having specific data to rely on, the author’s argument is stronger and readers will be more inclined to agree with it.

- For every argument the other side makes, the author makes sure to refute it and follow up with why her opinion is the stronger one. In order to make a strong argument, it’s important to dismantle the other side, which this essay does this by making the author's view appear stronger.

- This is a shorter paper, and if it needed to be expanded to meet length requirements, it could include more examples and go more into depth with them, such as by explaining specific cases where people benefited from local libraries.

- Additionally, while the paper uses lots of data, the author also mentions their own experience with using tablets. This should be removed since argumentative essays focus on facts and data to support an argument, not the author’s own opinion or experiences. Replacing that with more data on health issues associated with screen time would strengthen the essay.

- Some of the points made aren't completely accurate , particularly the one about digital books being cheaper. It actually often costs a library more money to rent out numerous digital copies of a book compared to buying a single physical copy. Make sure in your own essay you thoroughly research each of the points and rebuttals you make, otherwise you'll look like you don't know the issue that well.

Argumentative Essay Example 2

There are multiple drugs available to treat malaria, and many of them work well and save lives, but malaria eradication programs that focus too much on them and not enough on prevention haven’t seen long-term success in Sub-Saharan Africa. A major program to combat malaria was WHO’s Global Malaria Eradication Programme. Started in 1955, it had a goal of eliminating malaria in Africa within the next ten years. Based upon previously successful programs in Brazil and the United States, the program focused mainly on vector control. This included widely distributing chloroquine and spraying large amounts of DDT. More than one billion dollars was spent trying to abolish malaria. However, the program suffered from many problems and in 1969, WHO was forced to admit that the program had not succeeded in eradicating malaria. The number of people in Sub-Saharan Africa who contracted malaria as well as the number of malaria deaths had actually increased over 10% during the time the program was active.

One of the major reasons for the failure of the project was that it set uniform strategies and policies. By failing to consider variations between governments, geography, and infrastructure, the program was not nearly as successful as it could have been. Sub-Saharan Africa has neither the money nor the infrastructure to support such an elaborate program, and it couldn’t be run the way it was meant to. Most African countries don't have the resources to send all their people to doctors and get shots, nor can they afford to clear wetlands or other malaria prone areas. The continent’s spending per person for eradicating malaria was just a quarter of what Brazil spent. Sub-Saharan Africa simply can’t rely on a plan that requires more money, infrastructure, and expertise than they have to spare.

Additionally, the widespread use of chloroquine has created drug resistant parasites which are now plaguing Sub-Saharan Africa. Because chloroquine was used widely but inconsistently, mosquitoes developed resistance, and chloroquine is now nearly completely ineffective in Sub-Saharan Africa, with over 95% of mosquitoes resistant to it. As a result, newer, more expensive drugs need to be used to prevent and treat malaria, which further drives up the cost of malaria treatment for a region that can ill afford it.

Instead of developing plans to treat malaria after the infection has incurred, programs should focus on preventing infection from occurring in the first place. Not only is this plan cheaper and more effective, reducing the number of people who contract malaria also reduces loss of work/school days which can further bring down the productivity of the region.

One of the cheapest and most effective ways of preventing malaria is to implement insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs). These nets provide a protective barrier around the person or people using them. While untreated bed nets are still helpful, those treated with insecticides are much more useful because they stop mosquitoes from biting people through the nets, and they help reduce mosquito populations in a community, thus helping people who don’t even own bed nets. Bed nets are also very effective because most mosquito bites occur while the person is sleeping, so bed nets would be able to drastically reduce the number of transmissions during the night. In fact, transmission of malaria can be reduced by as much as 90% in areas where the use of ITNs is widespread. Because money is so scarce in Sub-Saharan Africa, the low cost is a great benefit and a major reason why the program is so successful. Bed nets cost roughly 2 USD to make, last several years, and can protect two adults. Studies have shown that, for every 100-1000 more nets are being used, one less child dies of malaria. With an estimated 300 million people in Africa not being protected by mosquito nets, there’s the potential to save three million lives by spending just a few dollars per person.

Reducing the number of people who contract malaria would also reduce poverty levels in Africa significantly, thus improving other aspects of society like education levels and the economy. Vector control is more effective than treatment strategies because it means fewer people are getting sick. When fewer people get sick, the working population is stronger as a whole because people are not put out of work from malaria, nor are they caring for sick relatives. Malaria-afflicted families can typically only harvest 40% of the crops that healthy families can harvest. Additionally, a family with members who have malaria spends roughly a quarter of its income treatment, not including the loss of work they also must deal with due to the illness. It’s estimated that malaria costs Africa 12 billion USD in lost income every year. A strong working population creates a stronger economy, which Sub-Saharan Africa is in desperate need of.

This essay begins with an introduction, which ends with the thesis (that malaria eradication plans in Sub-Saharan Africa should focus on prevention rather than treatment). The first part of the essay lays out why the counter argument (treatment rather than prevention) is not as effective, and the second part of the essay focuses on why prevention of malaria is the better path to take.

- The thesis appears early, is stated clearly, and is supported throughout the rest of the essay. This makes the argument clear for readers to understand and follow throughout the essay.

- There’s lots of solid research in this essay, including specific programs that were conducted and how successful they were, as well as specific data mentioned throughout. This evidence helps strengthen the author’s argument.

- The author makes a case for using expanding bed net use over waiting until malaria occurs and beginning treatment, but not much of a plan is given for how the bed nets would be distributed or how to ensure they’re being used properly. By going more into detail of what she believes should be done, the author would be making a stronger argument.

- The introduction of the essay does a good job of laying out the seriousness of the problem, but the conclusion is short and abrupt. Expanding it into its own paragraph would give the author a final way to convince readers of her side of the argument.

Argumentative Essay Example 3

There are many ways payments could work. They could be in the form of a free-market approach, where athletes are able to earn whatever the market is willing to pay them, it could be a set amount of money per athlete, or student athletes could earn income from endorsements, autographs, and control of their likeness, similar to the way top Olympians earn money.

Proponents of the idea believe that, because college athletes are the ones who are training, participating in games, and bringing in audiences, they should receive some sort of compensation for their work. If there were no college athletes, the NCAA wouldn’t exist, college coaches wouldn’t receive there (sometimes very high) salaries, and brands like Nike couldn’t profit from college sports. In fact, the NCAA brings in roughly $1 billion in revenue a year, but college athletes don’t receive any of that money in the form of a paycheck. Additionally, people who believe college athletes should be paid state that paying college athletes will actually encourage them to remain in college longer and not turn pro as quickly, either by giving them a way to begin earning money in college or requiring them to sign a contract stating they’ll stay at the university for a certain number of years while making an agreed-upon salary.

Supporters of this idea point to Zion Williamson, the Duke basketball superstar, who, during his freshman year, sustained a serious knee injury. Many argued that, even if he enjoyed playing for Duke, it wasn’t worth risking another injury and ending his professional career before it even began for a program that wasn’t paying him. Williamson seems to have agreed with them and declared his eligibility for the NCAA draft later that year. If he was being paid, he may have stayed at Duke longer. In fact, roughly a third of student athletes surveyed stated that receiving a salary while in college would make them “strongly consider” remaining collegiate athletes longer before turning pro.

Paying athletes could also stop the recruitment scandals that have plagued the NCAA. In 2018, the NCAA stripped the University of Louisville's men's basketball team of its 2013 national championship title because it was discovered coaches were using sex workers to entice recruits to join the team. There have been dozens of other recruitment scandals where college athletes and recruits have been bribed with anything from having their grades changed, to getting free cars, to being straight out bribed. By paying college athletes and putting their salaries out in the open, the NCAA could end the illegal and underhanded ways some schools and coaches try to entice athletes to join.

People who argue against the idea of paying college athletes believe the practice could be disastrous for college sports. By paying athletes, they argue, they’d turn college sports into a bidding war, where only the richest schools could afford top athletes, and the majority of schools would be shut out from developing a talented team (though some argue this already happens because the best players often go to the most established college sports programs, who typically pay their coaches millions of dollars per year). It could also ruin the tight camaraderie of many college teams if players become jealous that certain teammates are making more money than they are.

They also argue that paying college athletes actually means only a small fraction would make significant money. Out of the 350 Division I athletic departments, fewer than a dozen earn any money. Nearly all the money the NCAA makes comes from men’s football and basketball, so paying college athletes would make a small group of men--who likely will be signed to pro teams and begin making millions immediately out of college--rich at the expense of other players.

Those against paying college athletes also believe that the athletes are receiving enough benefits already. The top athletes already receive scholarships that are worth tens of thousands per year, they receive free food/housing/textbooks, have access to top medical care if they are injured, receive top coaching, get travel perks and free gear, and can use their time in college as a way to capture the attention of professional recruiters. No other college students receive anywhere near as much from their schools.

People on this side also point out that, while the NCAA brings in a massive amount of money each year, it is still a non-profit organization. How? Because over 95% of those profits are redistributed to its members’ institutions in the form of scholarships, grants, conferences, support for Division II and Division III teams, and educational programs. Taking away a significant part of that revenue would hurt smaller programs that rely on that money to keep running.

While both sides have good points, it’s clear that the negatives of paying college athletes far outweigh the positives. College athletes spend a significant amount of time and energy playing for their school, but they are compensated for it by the scholarships and perks they receive. Adding a salary to that would result in a college athletic system where only a small handful of athletes (those likely to become millionaires in the professional leagues) are paid by a handful of schools who enter bidding wars to recruit them, while the majority of student athletics and college athletic programs suffer or even shut down for lack of money. Continuing to offer the current level of benefits to student athletes makes it possible for as many people to benefit from and enjoy college sports as possible.

This argumentative essay follows the Rogerian model. It discusses each side, first laying out multiple reasons people believe student athletes should be paid, then discussing reasons why the athletes shouldn’t be paid. It ends by stating that college athletes shouldn’t be paid by arguing that paying them would destroy college athletics programs and cause them to have many of the issues professional sports leagues have.

- Both sides of the argument are well developed, with multiple reasons why people agree with each side. It allows readers to get a full view of the argument and its nuances.

- Certain statements on both sides are directly rebuffed in order to show where the strengths and weaknesses of each side lie and give a more complete and sophisticated look at the argument.

- Using the Rogerian model can be tricky because oftentimes you don’t explicitly state your argument until the end of the paper. Here, the thesis doesn’t appear until the first sentence of the final paragraph. That doesn’t give readers a lot of time to be convinced that your argument is the right one, compared to a paper where the thesis is stated in the beginning and then supported throughout the paper. This paper could be strengthened if the final paragraph was expanded to more fully explain why the author supports the view, or if the paper had made it clearer that paying athletes was the weaker argument throughout.

3 Tips for Writing a Good Argumentative Essay

Now that you’ve seen examples of what good argumentative essay samples look like, follow these three tips when crafting your own essay.

#1: Make Your Thesis Crystal Clear

The thesis is the key to your argumentative essay; if it isn’t clear or readers can’t find it easily, your entire essay will be weak as a result. Always make sure that your thesis statement is easy to find. The typical spot for it is the final sentence of the introduction paragraph, but if it doesn’t fit in that spot for your essay, try to at least put it as the first or last sentence of a different paragraph so it stands out more.

Also make sure that your thesis makes clear what side of the argument you’re on. After you’ve written it, it’s a great idea to show your thesis to a couple different people--classmates are great for this. Just by reading your thesis they should be able to understand what point you’ll be trying to make with the rest of your essay.

#2: Show Why the Other Side Is Weak

When writing your essay, you may be tempted to ignore the other side of the argument and just focus on your side, but don’t do this. The best argumentative essays really tear apart the other side to show why readers shouldn’t believe it. Before you begin writing your essay, research what the other side believes, and what their strongest points are. Then, in your essay, be sure to mention each of these and use evidence to explain why they’re incorrect/weak arguments. That’ll make your essay much more effective than if you only focused on your side of the argument.

#3: Use Evidence to Support Your Side

Remember, an essay can’t be an argumentative essay if it doesn’t support its argument with evidence. For every point you make, make sure you have facts to back it up. Some examples are previous studies done on the topic, surveys of large groups of people, data points, etc. There should be lots of numbers in your argumentative essay that support your side of the argument. This will make your essay much stronger compared to only relying on your own opinions to support your argument.

Summary: Argumentative Essay Sample

Argumentative essays are persuasive essays that use facts and evidence to support their side of the argument. Most argumentative essays follow either the Toulmin model or the Rogerian model. By reading good argumentative essay examples, you can learn how to develop your essay and provide enough support to make readers agree with your opinion. When writing your essay, remember to always make your thesis clear, show where the other side is weak, and back up your opinion with data and evidence.

What's Next?

Do you need to write an argumentative essay as well? Check out our guide on the best argumentative essay topics for ideas!

You'll probably also need to write research papers for school. We've got you covered with 113 potential topics for research papers.

Your college admissions essay may end up being one of the most important essays you write. Follow our step-by-step guide on writing a personal statement to have an essay that'll impress colleges.

Christine graduated from Michigan State University with degrees in Environmental Biology and Geography and received her Master's from Duke University. In high school she scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT and was named a National Merit Finalist. She has taught English and biology in several countries.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

BibGuru Blog

Be more productive in school

- Citation Styles

How to write an argumentative essay

The argumentative essay is a staple in university courses, and writing this style of essay is a key skill for students across multiple disciplines. Here’s what you need to know to write an effective and compelling argumentative essay.

What is an argumentative essay?

An argumentative essay takes a stance on an issue and presents an argument to defend that stance with the intent of persuading the reader to agree. It generally requires extensive research into a topic so that you have a deep grasp of its subtleties and nuances, are able to take a position on the issue, and can make a detailed and logical case for one side or the other.

It’s not enough to merely have an opinion on an issue—you have to present points to justify your opinion, often using data and other supporting evidence.

When you are assigned an argumentative essay, you will typically be asked to take a position, usually in response to a question, and mount an argument for it. The question can be two-sided or open-ended, as in the examples provided below.

Examples of argumentative essay prompts:

Two-sided Question

Should completing a certain number of volunteer hours be a requirement to graduate from high school? Support your argument with evidence.

Open-ended Question

What is the most significant impact that social media has had on this generation of young people?

Once again, it’s important to remember that you’re not just conveying facts or information in an argumentative essay. In the course of researching your topic, you should develop a stance on the issue. Your essay will then express that stance and attempt to persuade the reader of its legitimacy and correctness through discussion, assessment, and evaluation.

The main types of argumentative essays

Although you are advancing a particular viewpoint, your argumentative essay must flow from a position of objectivity. Your argument should evolve thoughtfully and rationally from evidence and logic rather than emotion.

There are two main models that provide a good starting point for crafting your essay: the Toulmin model and the Rogerian model.

The Toulmin Model

This model is commonly used in academic essays. It mounts an argument through the following four steps:

- Make a claim.

- Present the evidence, or grounds, for the claim.

- Explain how the grounds support the claim.

- Address potential objections to the claim, demonstrating that you’ve given thought to the opposing side and identified its limitations and deficiencies.

As an example of how to put the Toulmin model into practice, here’s how you might structure an argument about the impact of devoting public funding to building low-income housing.

- Make your claim that low-income housing effectively solves several social issues that drain a city’s resources, providing a significant return on investment.

- Cite data that shows how an increase in low-income housing is related to a reduction in crime rates, homelessness, etc.

- Explain how this data proves the beneficial impact of funding low-income housing.

- Preemptively counter objections to your claim and use data to demonstrate whether these objections are valid or not.

The Rogerian Model

This model is also frequently used within academia, and it also builds an argument using four steps, although in a slightly different fashion:

- Acknowledge the merits of the opposing position and what might compel people to agree with it.

- Draw attention to the problems with this position.

- Lay out your own position and identify how it resolves those problems.

- Proffer some middle ground between the two viewpoints and make the case that proponents of the opposing position might benefit from adopting at least some elements of your view.

The persuasiveness of this model owes to the fact that it offers a balanced view of the issue and attempts to find a compromise. For this reason, it works especially well for topics that are polarizing and where it’s important to demonstrate that you’re arguing in good faith.

To illustrate, here’s how you could argue that smartphones should be permitted in classrooms.

- Concede that smartphones can be a distraction for students.