If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

AP®︎/College Macroeconomics

Course: ap®︎/college macroeconomics > unit 2.

- Unemployment rate primer

- Natural, cyclical, structural, and frictional unemployment rates

- Worked free response question on unemployment

Lesson summary: Unemployment

- Unemployment

- Types of unemployment and the natural rate of unemployment

Lesson overview

Key takeaways, the labor force participation rate (lfpr), limitations of the unemployment rate, three types of unemployment, the natural rate of unemployment, changes in the natural rate of unemployment (nru), key equations, the labor force:, the unemployment rate (ur), common misperceptions.

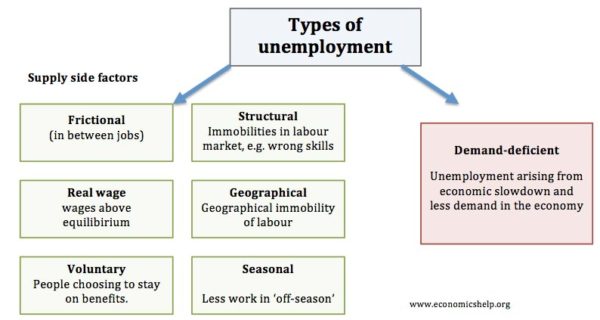

- Not everyone who is out of work is unemployed. In order to be counted as unemployed you have to be out of work, looking for work, and able to accept a job if one is offered to you. If you are out of work and not looking, then you are considered “not in the labor force” rather than unemployed.

- We tend to think of unemployment as an undesirable thing, but a certain amount of unemployment is actually part of a healthy economy. Structural unemployment occurs when new industries are created and old industries become obsolete. For example, when we moved from using horses and buggies to using cars to get around, this put a lot of buggy makers in the structurally unemployed category.

- Frictional unemployment might not seem very fun, but consider what it means to have zero unemployment—nobody ever looks for a job, they just remain in whatever job they are given! In fact, a number of dystopian novels have been written in which everyone in a society is automatically assigned a fixed career (such as the Divergent series). Those societies have zero frictional unemployment, but they are also quite unpleasant if you are unhappy with that career!

- A decrease in the unemployment rate isn’t necessarily a sign of an improving economy. When people stop looking for jobs and drop out of the labor force as discouraged workers, the unemployment rate will decrease even though the true employment situation hasn’t gotten any better. This is why it is important to look at both changes in the unemployment rate and changes in the labor force participation rate. Looking at both changes let’s you get a more complete idea about changes in the employment situation.

Discussion Questions:

- An inventor in Burginville developed a fantastic new dictation machine that perfectly records speech and turns it into a typed document. Unfortunately, that meant that unemployment increased among typists working in offices. Which type of unemployment is this? Explain. Solution, please. This is structural unemployment because typists skills are no longer desired. The changing structure of office work has resulted in people losing their jobs.

- The nation of Fitlandia has 120 , 000 people. Of these, 20 , 000 are children under the age of 16, 72,000 have jobs, 8,000 don’t have jobs and are looking for work, and 20,000 people are retired. Assuming that these are all noninstitutionalized civilians, calculate the labor force participation rate and the unemployment rate. I think I got it. Can I check my work? L F = # Employed + # Unemployed = 72,000 + 8,000 = 80,000 L F P R = L F Eligible Population × 100 % = 80,000 100,000 × 100 % = 80 % U R = # Unemployed # Labor Force × 100 % = 8,000 80,000 × 100 % = 10 %

- Explain why a decrease in the unemployment rate can actually signal a tough job market.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Home — Essay Samples — Economics — Unemployment — Unemployment: Causes, Effects, and Solutions

Unemployment: Causes, Effects, and Solutions

- Categories: Unemployment

About this sample

Words: 685 |

Published: Jan 30, 2024

Words: 685 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

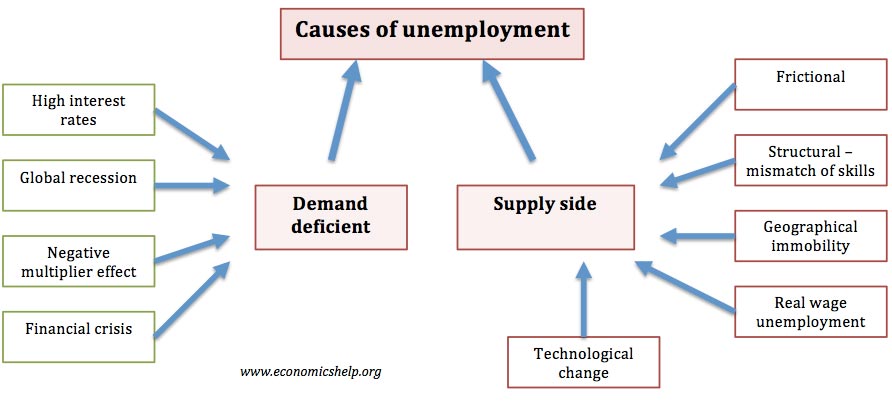

Introduction, causes of unemployment, effects of unemployment, solutions to combat unemployment, a. economic factors.

- Global recession: During economic downturns, companies may reduce employment to cut costs and remain competitive.

- Automation and technological advancements: The use of machines and technology may replace human workers in some industries, leading to job losses.

- Outsourcing of jobs: Companies may choose to outsource jobs to other countries where labor costs are lower, leaving domestic workers unemployed.

B. Societal Factors

- Lack of education and skills: Individuals without proper education and job training may be ill-equipped to meet the demands of a constantly evolving job market.

- Discrimination in hiring processes: Certain groups, such as women, minorities, and older workers, may face barriers in securing employment due to discrimination.

- Dependency on welfare programs: Some individuals may choose to remain on welfare programs due to a lack of incentive to enter the workforce or because they cannot find suitable employment.

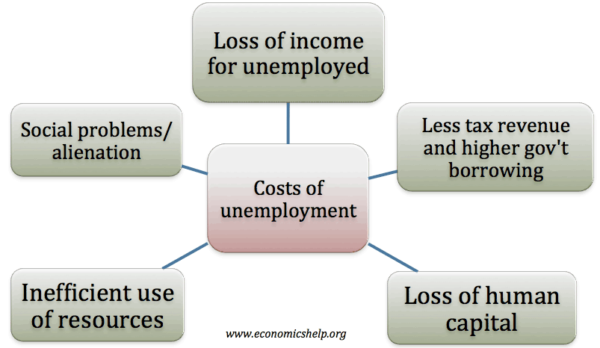

A. Economic Effects

- Reduction in consumer spending: Without a steady income, unemployed individuals may have less money to spend, resulting in a decline in consumer spending.

- Decline in government revenue: With fewer people working, the government may see a decline in tax revenue, which can impact its ability to provide necessary services and promote economic growth.

- Increase in social welfare expenses: The government may need to allocate more funds toward social welfare programs, such as unemployment benefits and food assistance, to support those who are unemployed.

B. Social Effects

- Increase in crime rates: Individuals who are unemployed may resort to criminal activities to make ends meet, leading to a rise in crime rates.

- Mental health issues: Unemployment can cause stress, anxiety, and depression, which can negatively impact an individual's mental health.

- Strained relationships and family instability: Unemployment may cause financial strain and tension within families, leading to relationship problems and instability.

A. Economic Solutions

- Encouraging entrepreneurship and small business development: Providing resources and support for individuals to start their own businesses can lead to job creation and economic growth.

- Promoting vocational training and skill development programs: Ensuring that individuals have access to education and training programs can increase their job readiness and competitiveness in the job market.

- Implementing balanced trade policies: Creating policies that promote fair trade and reduce job outsourcing can protect domestic jobs and promote job growth.

B. Social Solutions

- Addressing educational disparities and providing access to quality education: Providing quality education to disadvantaged communities can improve their job readiness and reduce unemployment rates.

- Combating discrimination in the workplace: Enforcing anti-discrimination laws and promoting diversity and inclusion in the workplace can reduce barriers to employment for certain groups.

- Strengthening social safety net programs: Ensuring that social welfare programs are designed to incentivize work and provide support to those in need can promote economic stability and reduce poverty.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2021, October 8). Employment Situation Summary. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.nr0.htm

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Economics

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1934 words

3 pages / 1230 words

5 pages / 2287 words

3 pages / 1581 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Unemployment

In today's fast-paced and competitive economy, the issue of unemployment remains a pressing concern for individuals and societies alike. The reasons for unemployment are multifaceted and complex, ranging from structural and [...]

Sociological imagination is a concept put forward by the sociologist C. Wright Mills in 1959. It refers to the ability to see the intersection between personal troubles and public issues, and to understand how these two are [...]

Unemployment has become a pervasive issue in societies worldwide, presenting both social and economic challenges. The lack of employment opportunities leads to despair among individuals who are unable to earn a living. This not [...]

The economy is a complex and constantly changing entity that can be difficult to understand, especially for college students who are just beginning to explore the intricacies of macroeconomics. One of the most fundamental [...]

In Malaysia, there are graduates remain unemployed need more concern by the government because it have become a serious case in Malaysia. In year 2015 involving 132,900 graduates from institutions of higher learning all over [...]

It is no secret that entrepreneurs square measure important to making wealth and driving economic process, innovation and employment. With the most recent federal budget saying that it'll support little businesses there has [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

What does the unemployment rate measure?

Subscribe to the hutchins roundup and newsletter, stephanie aaronson stephanie aaronson senior associate director, division of research and statistics - federal reserve board.

February 18, 2021

- 13 min read

This explainer builds off of a May 2020 post, “ Making Sense of the Monthly Jobs Report During the COVID-19 Pandemic .”

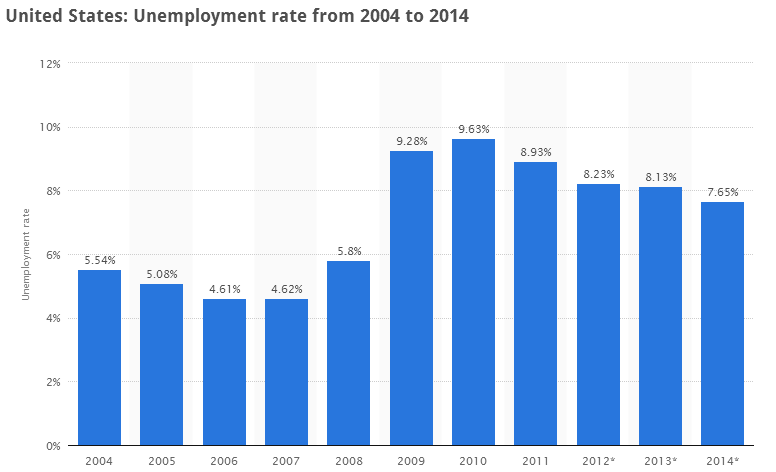

The unemployment rate soared from a 50-year low of 3.5 percent to 14.8 percent in April 2020 at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and then fell faster than many forecasters anticipated, to 6.3 percent in January 2021. But the labor market is far from healthy: for instance, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) counted 4.5 million more people as unemployed in January than were unemployed before the pandemic—and many more people weren’t counted as unemployed because they’d stopped looking for work. Here’s a guide to various measures of the health of the labor market.

What does the unemployment rate measure?

The headline unemployment rate (known as U-3) measures the percentage of people over the age of 16 who aren’t working but are available and actively looking for work.

Where do the data on unemployment come from?

Data on unemployment are collected every month in the Current Population Survey (CPS), a survey of about 60,000 households , conducted by the Census and the BLS every month, which includes roughly 105,000 people ages 16 and older . The questions about unemployment refer to what people were doing during the week that includes the 12th of the month, known as the “reference week”—so the survey to be released on Friday, March 4, 2021 will cover the week of February 8, 2021. The CPS is referred to as the household survey, to distinguish it from the establishment survey, which counts the number of people on employer payrolls. (The latest tally of payrolls showed that as of January 2021, we have recovered 9.9 million of the 22.4 million jobs lost since the beginning of 2020.)

How are individuals in the monthly survey identified as being unemployed ?

Respondents to the survey are first asked whether they worked during the week that includes the 12th of the month. Individuals are counted as employed if they did any work at all as a paid employee, if they worked in their own business, or worked without pay for at least 15 hours in a family business. People are also counted as employed if they were temporarily absent from work as a result of sickness, bad weather, vacation, a strike, or personal reasons. Such workers are classified as employed but absent from work.

Respondents who are not employed then are asked if they have looked for work in the previous four weeks and are available to work. If so, they are counted as unemployed. Respondents who did not work but are on temporary layoff from a job with the expectation that they will be recalled—as many furloughed employees are today—are counted as unemployed whether they looked for a job or not.

What’s the difference between being unemployed and being out of the labor force?

People who are not working and who don’t meet the criteria to be counted as unemployed are said to be out of the labor force. This category includes students, retirees, and those who stay at home to take care of family members. In addition, people who report wanting a job but who have not looked for work in the most recent four weeks are also considered out of the labor force. Between February 2020 and January 2021, 5.5 million people dropped out of the labor force, on net. At the same time, the number of people out of the labor force who said they wanted a job rose by 1.9 million.

Why is it hard to determine if people are unemployed in the COVID-19 pandemic?

While the survey questions are the same as always, the nature of the COVID-19 economy means that people’s behavior, and hence the data, may not follow the same pattern that we usually see when the economy is turning down. For instance, early in the pandemic, the share of workers reporting themselves employed but not at work skyrocketed. While some of this increase was due to a rise in illness or childcare responsibilities, the number of people reporting themselves “not at work for other reasons” rose from around 600,000 prior to the pandemic to over 8 million. In conducting the survey, the BLS has attempted to categorize those employed but absent from work due to “pandemic-related business closures or cutbacks” as unemployed. Despite this effort, an unusually large number of workers in this situation have still been counted as “not being at work for other reasons,” which the BLS views as misclassification . Following its typical procedure, the BLS has categorized individuals reported as “not being at work for other reasons” as employed rather than unemployed. While this classification is in keeping with their standard practice, it has the effect of depressing the unemployment rate relative to a case where these workers are categorized as unemployed. That said, this misclassification is certainly less severe now than it was early in the recession: in January 2021, the number was 1.7 million. In addition, the BLS has publicly stated its estimate of the size of this mismeasurement. In January, the BLS reported that if misclassified workers had been counted as unemployed, the unemployment rate would have been 0.6 percentage points higher, or 6.9 percent. It also noted that this was an upper-bound estimate.

Among those who have lost jobs, the typical behavior would be to transition from employment into unemployment rather than to transition out of the labor force. However, early in the pandemic, with stay-at-home orders in place and nonessential businesses closed in many communities, people who left employment were much less likely to seek work than would typically be the case. In addition, schools closed in many places, which meant that many people who lost their jobs had child-care responsibilities that prevented them from seeking or accepting a new job. Even now, nearly a year into the pandemic, many of these same dynamics are in place. As a result, relative to a typical downturn, we expect the headline unemployment rate to be relatively lower than in a typical recession and the percent of those out of the labor force to be relatively higher, especially the percent of those who say they want a job but aren’t looking.

Indeed, we saw evidence of this in March 2020 , when, relative to the prior trend, an additional 1.2 million people moved from employment to out of the labor force, and the number of people categorized as out of the labor force but wanting a job rose by 500,000. The resulting decline in the labor force participation rate was much larger than would be expected given the rise in the unemployment rate, and it remains unusually low.

Given the limitations of the unemployment rate as a measure of labor market slack, what are some alternatives?

The BLS releases six measures of labor market slack in the monthly jobs report. These include the official unemployment rate (U-3), discussed above, as well as more narrow definitions, called U-1 and U-2, which respectively include only those unemployed at least 15 weeks (the long-term unemployed) or for less than a month (the short-term unemployed). The BLS also publishes broader definitions of slack. The U-6 rate, for instance, counts all those who are technically unemployed plus those are who are working part-time but would prefer full time work, and those “marginally attached to the labor force,” that is, people who say they want either a full-time or part-time job, have not looked for work in the most recent four weeks, but have looked for a job sometime in the past 12 months. When adults classified as “marginally attached” report that they did not recently seek work because they do not believe jobs are available for them, they are classified as “discouraged workers.” The U-4 counts the unemployed and discouraged workers, while U-5 adds in other marginally attached workers. In January, the broadest of these measures, U-6, stood at 11.1 percent, 4.8 percentage points higher than the official unemployment rate.

Given the measurement problems during the pandemic, are there alternatives to the BLS indicators of slack to gauge the health of the labor market?

Some economists have offered their own estimates of labor market slack trying to account for the misclassification and unusual movements in labor force participation during the pandemic. For example, Jason Furman and Wilson Powell III at the Peterson Institute for International Economics calculate what they call the “ realistic unemployment rate .” Their realistic unemployment rate was 8.3 percent in January , two percentage points higher than the official unemployment rate. Furman and Powell’s realistic unemployment rate differs from the official in two ways. First, they estimate the number of workers misclassified as being “not at work for other reasons” and count them as unemployed. Second, they try to estimate the excess decline in labor force participation beyond what would be expected given the rise in unemployment, and add those people to the unemployment rate as well. While this estimate is dependent on the specific modeling assumptions, it is nonetheless a useful attempt to reveal the extent to which we underestimate the true disruption to people’s livelihoods if we fail to account for the unusually large drop in labor force participation.

In a recent speech , Fed Chair Jerome Powell outlined his own method for adjusting the unemployment rate to capture the unusual features of the pandemic labor market. First, like Furman and Powell, he adds to the count of the unemployed an estimate of the misclassified workers. In addition, he adds in the number of people who have left the labor force since last February. This measure does not attempt to account for the fact that more people dropped out of the labor force than usual, and it does not account for structural reasons that individuals may have dropped out of the labor force, such as retirement. At the same time, it also isn’t sensitive to the specific modeling assumptions regarding the behavior of the participation rate. His calculations boost the unemployment rate to close to 10 percent in January .

One shortcoming of both these approaches is that they implicitly or explicitly make an assumption about what share of the individuals who are out of the labor force would be unemployed in a more normal recession. In addition, by counting individuals who are out of the labor force as unemployed, these measures would seem to assume that such individuals will act like the unemployed once the economy recovers. But typically, people who are out of the labor force are less likely to become employed than are those who are unemployed. One measure of the unemployment rate that includes individuals out of the labor force but also accounts for this variation in the propensity to return to work is the Hornstein-Kudlyak-Lange non-employment index , which was 9.3 percent in January.

A simpler measure is the employment-to-population-ratio (EPOP), a ratio of the number of people employed to the number of people in the population. The EPOP , which stood at 61.1 percent on the eve of the pandemic, declined by 9.8 percentage points between February and April—the largest decline since the series began in January 1948. Although the EPOP has recovered somewhat, to 57.5 percent, it still stands at its lowest level since the early 1980s, a time when far fewer women were in the labor force. This large drop is direct evidence of the unprecedented toll that the pandemic has taken on the labor market and people’s livelihoods.

What are “initial claims” for unemployment insurance?

When people first file for unemployment insurance (UI), they are counted as an “initial claim.” So when unemployment increases, initial claims tend to rise. Because initial claims are reported weekly , they are often used as an early indicator of the overall unemployment rate.

What is the relationship between initial claims and the unemployment rate — and why might it be different now?

The number of people receiving UI and the number counted as unemployed do tend to move in the same direction, but there is no formal link between the two. The only criteria for being counted as unemployed (and hence included in the unemployment rate) are that you are without a job and that you have actively searched for work or are on temporary layoff. You don’t need to be collecting unemployment insurance to be counted as unemployed. And some people are eligible to collect partial unemployment insurance benefits if they are working but have been assigned a schedule that is far below their usual weekly hours.

Many people who become unemployed do not apply for UI benefits, either because they are not eligible or because they choose not to apply. So initial claims typically understate the number of people becoming unemployed in a given week. That said, there are people who file an initial claim and are not counted as unemployed in the CPS. This could happen if a person doesn’t meet the CPS criteria for being unemployed—for instance, if they file for UI because their work schedule was reduced, or if the person has a very short spell of unemployment which is not captured in the CPS (for example, a person who becomes unemployed and finds a job in between survey reference weeks).

Furthermore, many people who are unemployed and do file an initial claim do not end up receiving unemployment insurance benefits, either because they are not covered by the program, because they have not accumulated enough working hours to be eligible for benefits, or because they don’t satisfy the job search requirements. In February 2020, before the pandemic, the number of people unemployed was about 5.8 million while the number of people receiving UI benefits averaged only about 1.7 million.

What is the payroll survey? And why is it likely to be less useful than usual?

The payroll (or establishment) survey is a survey of 145,000 businesses—employing about one third of all workers on nonfarm payrolls. The payroll survey tends to have difficulty when the economy is at a turning point, as is the case now. To create the sample to be surveyed, the BLS picks firms from the universe of firms that have unemployment insurance tax accounts. However, new firms do not enter the BLS sample universe right away, and the BLS can have difficulty distinguishing non-response from a firm closure in real time. Since the net contribution of jobs created at new firms and jobs destroyed at closing firms is typically small, the BLS assumes that nonresponding firms have the same change in employment as occurred at firms that responded. It then uses a model, called the net birth-death model, to forecast the residual between that imputation and the actual data. This model tends to overestimate employment growth when the economy is weakening and underestimate it when the economy is improving. And while the model error is typically small, it can, on occasion, be large.

We know about these forecast errors because the BLS revises the data based on more complete information. In most years the benchmark is small, with the level of employment revising up or down by less than 0.2 percentage points. However, strikingly, when the establishment survey data for March 2009—the depths of the Great Recession—were benchmarked, the level of payroll employment was revised down by over 900,000 jobs, or 0.7 percentage points—meaning that employers had shed 75,000 more jobs each month between April 2008 and March 2009 than previously estimated.

If, as a result of the pandemic, an unusually large number of firms are closing and few are opening, it seems possible that even the dramatic decline in employment that we are likely to see will underestimate the true extent of job loss.

Why might the historical link between unemployment and poverty be a misleading way to look at today’s numbers?

When people become unemployed, they lose an important (and sometimes their only) source of income and are at risk of falling into poverty. Of course, the more generous unemployment insurance is, the less likely it is for someone who loses a job to become poor. But unemployment insurance has typically replaced only about 40 percent of lost wages, on average, over the past 20 years, with a lot of variation in generosity across the states.

The federal response to the pandemic changed that. The CARES Act, for instance, added $600 a week to weekly unemployment insurance benefits through the end of July 2020, preventing many families from falling into poverty, and the December extension provided for an additional $300. And, of course, Congress provided two rounds of one-time payments for most families—$1,200 per adult and $500 per dependent child in the spring of 2020 and another $600 per individual in December, with payments phasing out for higher earners. Estimates suggest that about 13 million people were prevented from falling into poverty by these efforts.

The author thanks Francisca Alba for research assistance and Becca Portman for graphic design.

Labor & Unemployment

Economic Studies

The Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy

David Wessel

May 22, 2024

Joseph Parilla, Glencora Haskins, Mark Muro

May 21, 2024

Robert Maxim

The Reporter

Long-Run Trends and the Natural Rate of Unemployment

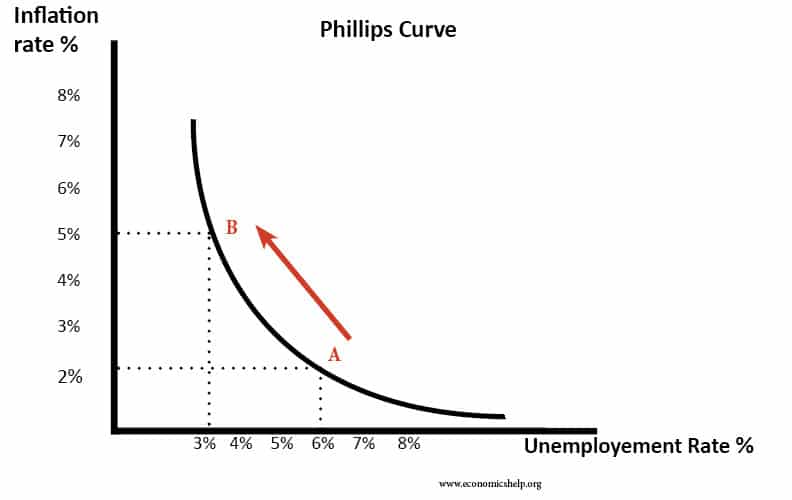

Starting with Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps, academics and policymakers have endeavored to measure a sustainable level of unemployment and the implications that deviations from this level have for inflation of prices and wages. This natural rate of unemployment, u *, is broadly defined as the unemployment rate at which, controlling for supply shocks, inflation remains stable.

Long-run trends in the labor market and changes in inflation expectations make it hard to pin down this natural rate of unemployment. Specifically, the dramatic trend decline in unemployment and the concurrent anchoring of inflation expectations since the 1980s have triggered extensive discussions in policy and academic circles. My recent work focuses on using detailed data on labor market flows and inflation expectations to estimate the natural rate of unemployment.

In this report, I first focus on the drivers of the trend decline in unemployment and review my work that connected this decline to two prominent long-run trends in the economy: the grand gender convergence and the dual aging of workers and firms. Then I summarize my work and discuss a unified framework that I have developed with Richard Crump, Stefano Eusepi, and Marc Giannoni for estimating the natural rate of unemployment. While I mostly focus on the period before the COVID-19 pandemic, I end with a discussion of the effect of the pandemic on the natural rate of unemployment.

Trend Decline in the Unemployment Rate

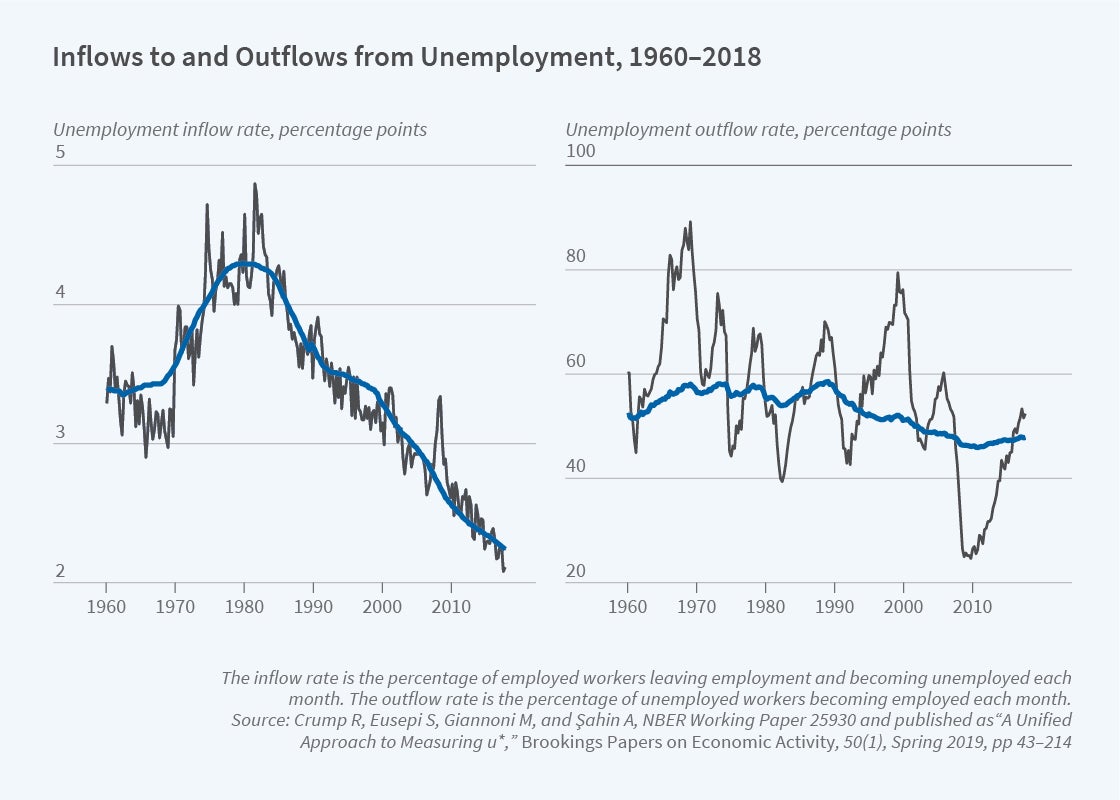

A useful insight from my research with Michael Elsby and Bart Hobijn is that the flow origins of unemployment rate movements provide useful information about the underlying drivers of unemployment fluctuations and trends. 1 The idea is simple: the unemployment rate increases either because more workers become unemployed (inflows increase) or it becomes harder for the unemployed to leave unemployment (outflows decrease). Visual examination of inflow and outflow rates in Figure 1 shows that the inflow rate is characterized by sharp, short-lived spikes during recessions, while the outflow rate from unemployment is strongly procyclical with persistent downswings during recessions. The figure also shows the secular trends in these flow rates, estimated using flow data by detailed demographics with a state-space method that I developed with Crump, Eusepi, and Giannoni. 2 The two flows that shape the evolution of the unemployment rate over time exhibit differential long-run trends. The inflow rate has a striking downward trend declining gradually to 0.02, with half of its level preceding the twin recessions of the early 1980s. In contrast, there is no evident trending behavior in the outflow rate.

This stark decline in the rate at which workers become unemployed caused about a 1 percentage point decline from the 1980s to the 1990s and another 1.5 percentage point decline from the 1990s to 2020 in the long-term trend rate of unemployment. Interestingly, this downward trend continued even after the dramatic job losses of the Great Recession, underscoring the importance of secular trends in the labor market. My research has focused on explaining this declining incidence of unemployment.

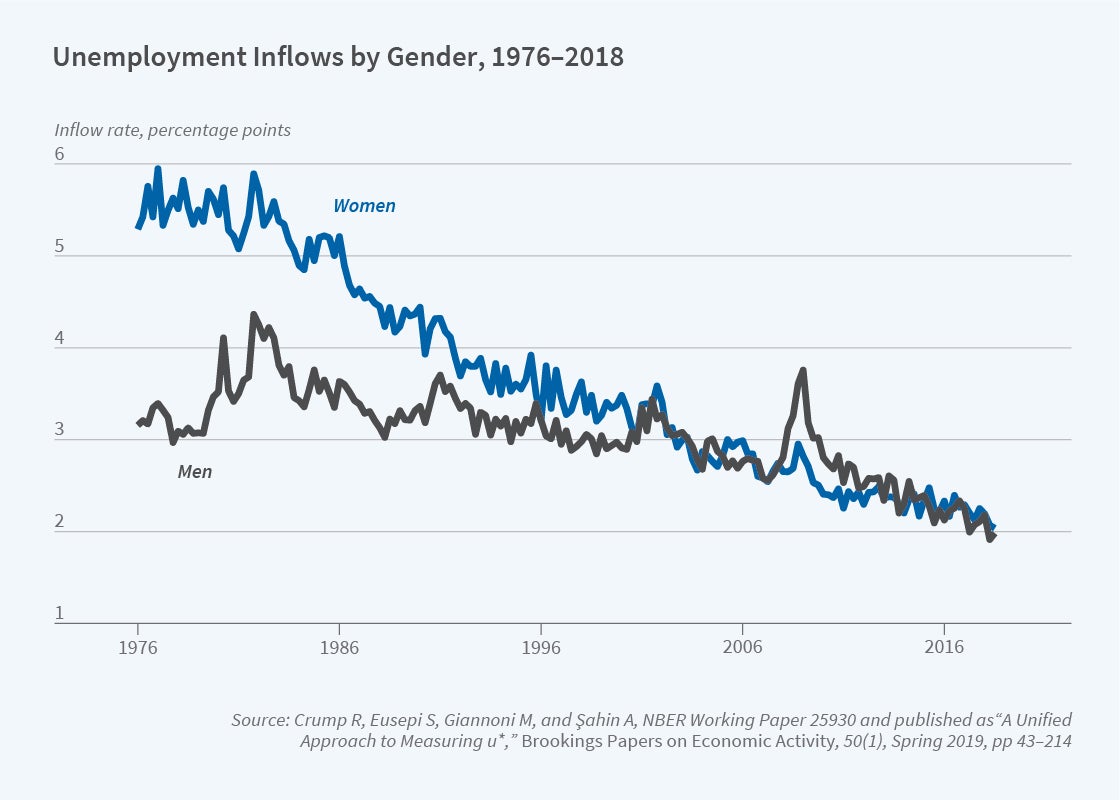

Grand Gender Convergence

The United States experienced grand gender convergence in the 20th century, with female labor force participation, the fraction of all women who are in the labor force, increasing from around 47 percent in 1976 to approximately 60 percent in 2000. 3 The main driver of the rise in the female labor force participation rate was the increase in participation of married women with children. Women started to work longer into their pregnancies and to work sooner after childbirth than their counterparts in the 1960s, likely due to changes in social norms, more widespread availability of maternity leave, which facilitated return to women’s previous jobs, and advances in maternal health and child care. As labor market interruptions declined, women’s labor force attachment gradually increased. Having stretches of uninterrupted employment allowed women to build more stable employment relationships. Stefania Albanesi and I found that this reduced frictional unemployment through a decline in the incidence of job loss and the incidence of unemployment during reentry into the labor force. 4 Figure 2 shows the unemployment inflow rate by gender.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the unemployment inflow rate for women, which had been higher than that for men, converged to men’s rate, driving down the secular trend of unemployment. The importance of gender convergence was relatively minor after 2000. This is when another prominent trend — dual aging — took over.

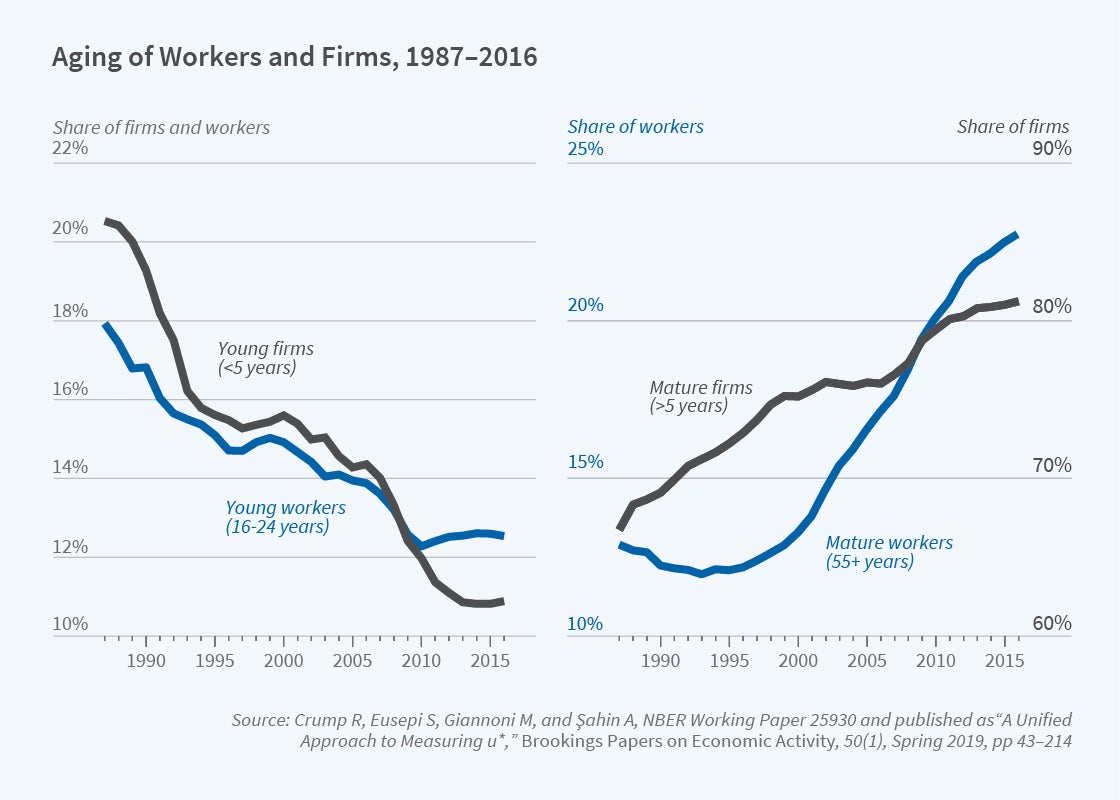

The US economy has been experiencing a striking shift toward older workers and older firms since the mid-1990s. While the change in worker demographics is directly attributable to the drastic increase in births following World War II, the emphasis on aging of firms is relatively new, as data have only recently become available. Benjamin Pugsley and I show that declining births of firms almost fully account for the shift of employment toward older firms. 5 Moreover, in joint work with Fatih Karahan, Pugsley and I find that the origin of the decline in firm entry is the decline in labor supply growth arising from the aging of the baby boom cohort and the flattening out of the female labor force participation rate. 6 We establish a clear link from worker to firm demographics.

The aging pattern is stark. Around 18 percent of the labor force consisted of workers between 16 and 24 years old ( young workers in Figure 3) in 1987. By 2017, the number had declined to 10 percent. The employment share of firms less than five years old also followed a similar pattern, with their share declining from around 20 percent to 10 percent. On the flip side, in 1987, firms 11 or more years old —mature firms — employed about two-thirds of the workers in the economy. By 2017, the number of workers in mature firms had increased to 80 percent. [Figure 3]

Younger workers are four times more likely to become unemployed than prime-age workers. Similarly, firms aged between one and five years old are twice as likely to eliminate jobs as their older counterparts. These patterns suggest that declines in unemployment and job destruction are direct consequences of dual aging. While the shift in worker and firm age composition falls short of accounting for the decline in the inflow rate, aging also affects the economy by affecting age-specific outcomes. Put differently, in economies with older workers and firms, unemployment and job destruction are lower for all workers. Using state-level variation and an instrumental variables approach, Crump, Eusepi, Giannoni and I showed that a 1 percentage point increase in mature firms’ share lowers the job destruction rate by 0.60 percentage points for younger firms. 7

While grand gender convergence was important in accounting for the secular decline in the unemployment rate until 2000, dual aging stands out as an important driver of the decline since then.

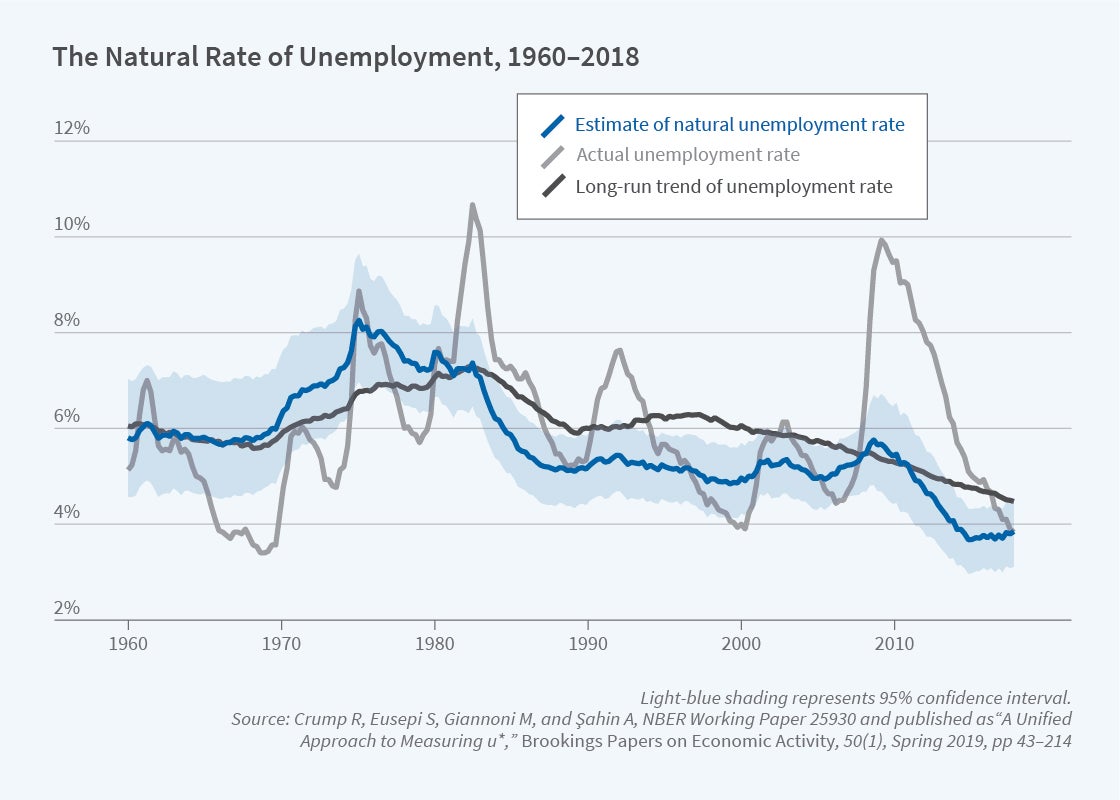

Natural Rate of Unemployment

Grand gender convergence and dual aging together have reduced the overall incidence of unemployment, and consequently the secular trend of unemployment. Concurrently, inflation expectations became better anchored following the Volcker disinflation. 8 Estimating the natural rate of unemployment requires recognizing these prominent changes in the macroeconomy.

Crump, Eusepi, Giannoni and I calculate this in our recent paper. 9 We employ a forward-looking Phillips curve linking inflation to expected inflation and the unemployment gap (the difference between the actual and natural rates of unemployment). We utilize survey-based expectations of inflation at different horizons to provide noisy signals of true inflation expectations and impose that the secular trend of unemployment we derive from the flow dynamics acts as an anchor for the natural rate, while accommodating the possibility of persistent deviations.

Figure 4 shows the evolution of u* since 1960. In the first decade of the sample, the natural rate hovers slightly below 6 percent and starts rising in the early 1970s, easily exceeding 7 percent by the late 1970s before falling to about 7 percent in 1983. The natural rate then declines throughout the 1980s falling consistently below the median of the secular trend of the unemployment rate (black solid line). The period from the 1990s to the Great Recession is characterized by a fairly stable natural rate of unemployment, which remains range-bound between 4.5 and 5.5 percent. Finally, during the prerecession years 2005–06, the natural rate of unemployment begins increasing toward its long-run trend. In the aftermath of the Great Recession, the natural rate of unemployment gradually declines roughly in line with its secular trend. The natural rate toward the end of 2018 was 3.8 percent, with a confidence interval between 3.4 and 4.5 percent, consistent with the unemployment gap being around zero before the pandemic.

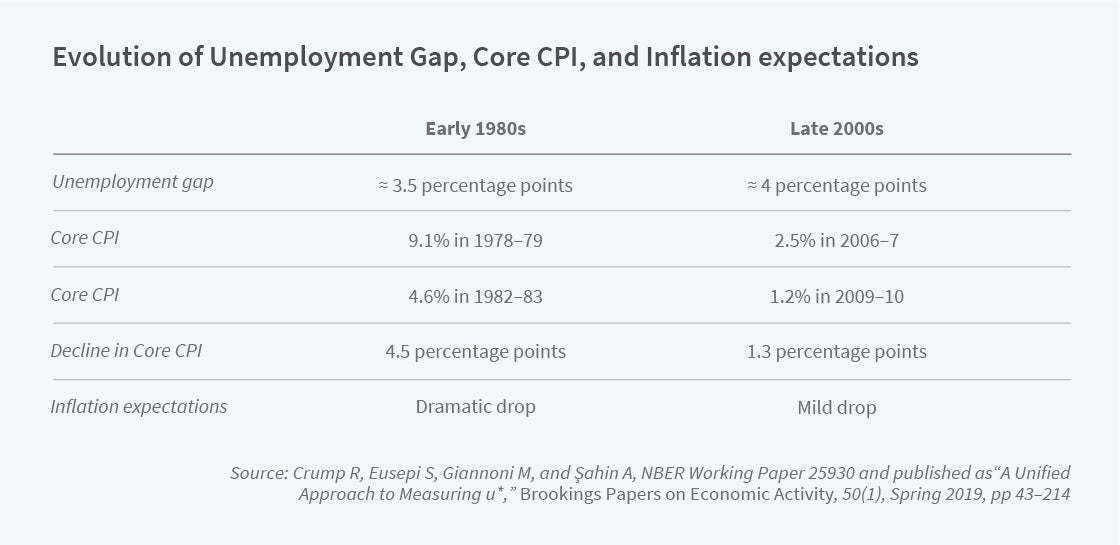

While some recent work argues for a change in the unemployment-inflation trade-off, our work emphasizes the role of inflation expectations. This is illustrated in Table 1, which compares the early 1980s with the late 2000s. In the early 1980s, we estimate an unemployment gap (the difference between the actual and the natural rate of unemployment) of 3.5 percentage points. During this time period, average core CPI inflation fell from 9.1 percent in 1978–79 to 4.6 percent in 1982–83. Following the Great Recession, which displays the largest unemployment gap in the sample, at around 4 percentage points, price inflation declined only modestly, from 2.5 percent in 2006–07 to 1.2 percent in 2009–10. The key determinant is the behavior of inflation expectations, which dropped much more sharply in the early 1980s than in the aftermath of the Great Recession. The comparison of the early 1980s with the Great Recession period demonstrates the importance of accounting for inflation expectations in explaining the behavior of inflation and the unemployment gap.

The longest labor market expansion in postwar US history came to an abrupt end with the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. The unemployment rate jumped from its historically low level of 3.5 percent in February to 14.8 percent in April. This sharp increase was followed by a steep decline; the unemployment rate retreated to 6.9 percent by October. Murat Tasci, Jin Yan, and I show that this was due to the unprecedented rise in unemployment inflows, which was mostly driven by workers on temporary layoffs. 10 Applying the methodology I developed with Crump, Eusepi, and Giannoni, we find that during the pandemic recession, increased from 3.8 percent to a range of 4.0 to 4.5 percent, suggesting that the unemployment gap as of May 2021 stood between 1.3 and 1.8 percentage points.

Researchers

More from nber.

“ Unemployment Dynamics in the OECD ,” Elsby M, Hobijn B, Şahin A. NBER Working Paper 14617, December 2008, and Review of Economics and Statistics 95(2), 2013, pp. 530–548.

“ A Unified Approach to Measuring u * ,” Crump R, Eusepi S, Giannoni M, Şahin A. NBER Working Paper 25930, June 2019, and published in Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 50(1), Spring 2019, pp. 43–214.

“ The Quiet Revolution That Transformed Women’s Employment, Education, and Family ,” Goldin C. NBER Working Paper 11953, January 2006.

“ The Gender Unemployment Gap,” Albanesi S, Şahin A. NBER Working Paper 23743, August 2017, and Review of Economic Dynamics 30, 2018, pp. 47–67.

“ Grown-up Business Cycles ,” Pugsley B, Şahin A. Review of Financial Studies 32(3), 2018, pp. 1102–1147.

“ Demographic Origins of the Startup Deficit ,” Karahan F, Pugsley B, Şahin A. NBER Working Paper 25874, May 2019.

Ibid note 2.

“ Anchored Inflation Expectations ,” Carvalho C, Eusepi S, Moench E, Preston B. 2017, SSRN.

“ Unemployment in the Time of COVID-19: A Flow-Based Approach to Real-Time Unemployment Projections ,” Şahin A, Tasci M, Yan J. NBER Working Paper 28445, February 2021.

NBER periodicals and newsletters may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

© 2023 National Bureau of Economic Research. Periodical content may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

Unemployment Essay

500+ words essay on unemployment.

Unemployment is a serious problem among young people. There are thousands of people who do not have any work to do and cannot find work for themselves. Unemployment refers to the situation where a person wants to work but cannot find employment in the labour market. One of the major reasons that contribute to unemployment is the large population of India and the limited availability of resources. In this essay on unemployment, we will discuss all these issues responsible for unemployment in India and how we can overcome this problem. Students must go through this unemployment essay to get ideas on how to write an effective essay on the topic related to unemployment. Also, they can practice more CBSE essays on different topics to boost their writing skills.

Unemployment is measured by the unemployment rate, defined as the number of people actively looking for a job as a percentage of the labour force. The unemployment rate for the year 2013-14 in rural India was 4.7%, whereas it was 5.5% for urban India. In the short term, unemployment significantly reduces a person’s income and, in the long term, it reduces their ability to save for retirement and other goals. Unemployment is a loss of valuable productive resources to the economy. The impact of job loss in rural and regional areas flows through the local community, damaging businesses.

Reason for Unemployment

An unemployed person is one who is an active member of the labour force and is seeking work but is unable to find any work for himself. There are multiple reasons behind the unemployment of a person. One of them is the slow economic growth, due to which jobs in adequate numbers are not created. Excessive dependence on agriculture and slow growth of non-farm activities also limit employment generation. Unemployment in urban areas is mainly the result of substantial rural migration to urban areas. This has also resulted in a labour workforce in cities. The lack of technology and proper machinery has also contributed to unemployment.

The present educational system is based on theoretical knowledge instead of practical work. Thus, it lacks the development of aptitude and technical qualifications required for various types of work among job seekers. This has created a mismatch between the need and availability of relevant skills and training. This results in unemployment, especially among the youth and educated people with high degrees and qualifications. Apart from it, the lack of investment and infrastructure has led to inadequate employment opportunities in different sectors.

Steps to Eliminate Unemployment

Various strategies and proposals have been implemented to generate employment. Many Employment programmes and policies have been introduced and undertaken to boost self-employment and help unemployed people engage in public works. The Government of India has taken several policy measures to fight the problem of unemployment. Some of the measures are the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), National Skill Development Mission, Swarna Jayanti Shahari Rozgar Yojana (SJSRY), Regional Rural Banks (RRBs).

Despite the measures taken by the government, India remains a country experiencing severe unemployment problems. It can be resolved by imparting education in such a way that youth get the necessary skills so as to get employment easily. Setting up various vocational training and vocational courses for undergraduate and postgraduate students will help in finding employment for youth. The government needs to emphasise these courses at the primary level and make them a compulsory part of the curriculum to make students proficient in their early stages of life. Career counselling should be provided within schools and colleges so that students can choose a better career option based on their interests and ability. Government should create more job opportunities for the youth and graduates.

India is a fast-growing economy. There is an enormous scope for improvement in the unemployment sector. The various measures and steps taken by the government to increase the employment rate have succeeded to a great extent. The widespread skill development programmes have gained popularity across the nation. With better enforcement of the strategies, the employment level can be significantly improved. Although, we have to go a long way before we can say that all the people in India will get employment.

We hope this essay on unemployment must have helped students in boosting their essay-writing skills. Keep learning and visiting the BYJU’S website for more study material.

Frequently Asked Questions on Unemployment Essay

Is unemployment still an existing problem in india.

Yes, unemployment is still a serious issue in our country. Steps need to be taken by the government and also by the youngsters in India to improve this situation.

Is it necessary for schoolchildren to be informed about unemployment?

Students at this young age should definitely be informed about this topic as it will motivate them to study and aim for higher scores in exams.

What points are to be added to an essay topic on Unemployment?

Add details about different age groups of people suffering from this state of employment. You can focus on the fact that poverty is an indirect reason for unemployment and vice-versa. Then, suggest steps that can be taken to bring about an improvement in education and increase the percentage of literacy.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Counselling

- Main navigation

- Main content

Recessions and the Trend in the US Unemployment Rate

- Kurt G. Lunsford

The unemployment rate in the United States falls slowly in expansions, and it may not reach its previous low point before the next recession begins. Based on this feature, I document that the frequent recessions prior to 1983 are associated with an upward trend in the unemployment rate. In contrast, the long expansions beginning in 1983 are associated with a downward trend. I then estimate a two-variable vector autoregression (VAR) that includes the unemployment rate and a recession indicator. Long-horizon forecasts from this VAR conditioned on no future recessions project that the unemployment rate will go to 3.6 percent after a long period with no recessions.

The views authors express in Economic Commentary are theirs and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The series editor is Tasia Hane. This paper and its data are subject to revision; please visit clevelandfed.org for updates.

When it comes to analyzing economic indicators to predict where the US economy is headed, the unemployment rate is arguably the variable familiar to most people. It receives attention from academics, policymakers, business economists, and politicians, but also the public at large. An appealing feature of the unemployment rate is its perceived ease of interpretation. A high or rising unemployment rate is a signal of macroeconomic slack or contraction, and a low or falling unemployment rate is a signal of macroeconomic health or expansion.

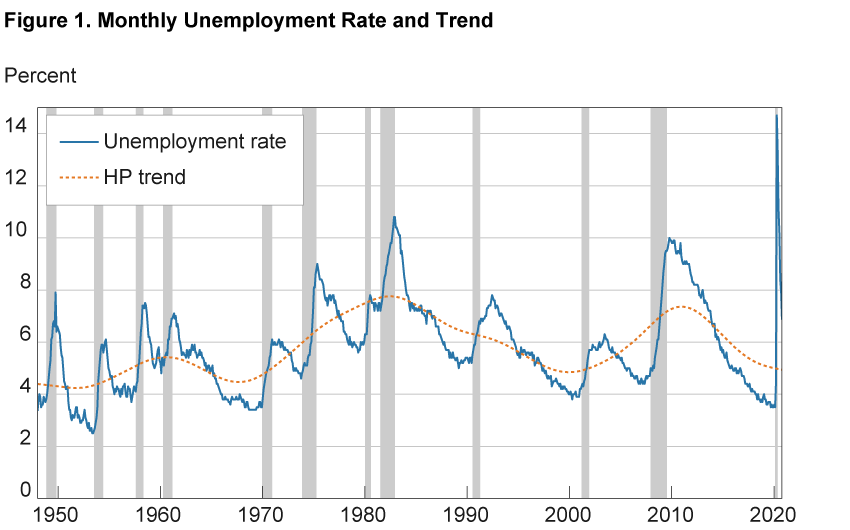

One issue that can confound this simple interpretation is that the unemployment rate may have a slow-moving trend that changes over time. If the trend is not static, then it is hard to know how far the current or forecasted unemployment rates are from the underlying trend. Figure 1 highlights this issue. It shows the monthly unemployment rate from January 1948 to October 2020 along with a line intended to estimate the unemployment rate trend. I compute this line with the statistical technique in Hodrick and Prescott (1997) (HP). 1 The trend line shows substantial variation, falling below 5 percent in the 1960s and 1990s and rising above 7 percent in the 1980s and 2010s. Because of this changing trend, an unemployment rate of 6 percent may be viewed as indicating macroeconomic slack in some periods but macroeconomic health in other periods, making it difficult for economists, policymakers, and the public at large to know where the economy stands. 2

Notes: Trend computed using a Hodrick and Prescott (1997) filter. Gray bars indicate recession periods. Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Unemployment Rate [UNRATE], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ( https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE ), and author’s calculations.

Researchers and policymakers often acknowledge the trend in the unemployment rate. Researchers typically remove a time-varying trend from the unemployment rate before studying its business cycle properties. 3 Policymakers on the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) note in their Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy that the maximum level of employment “changes over time.” 4 In fact, the longer-run projections of the unemployment rate in the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections have drifted down since 2012. 5

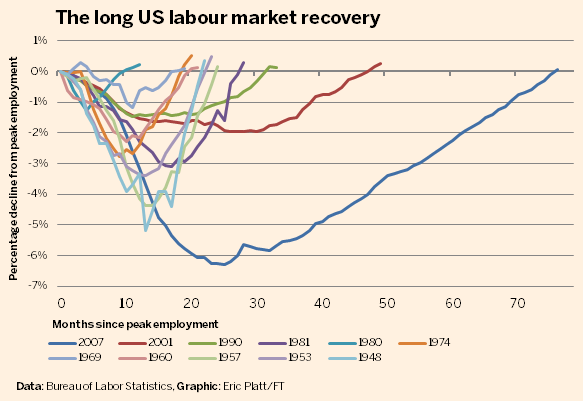

Research has attributed much of the trend in the unemployment rate to demographic changes. 6 In this Commentary , I suggest an additional, previously unrecognized source of the trend: the frequency of recessions. Because the unemployment rate rises quickly in recessions but falls slowly in expansions, it may not fall to its previous low point if a recession cuts an expansion short. 7 Hence, frequent recessions can cause the unemployment rate to trend up over time. Figure 1 shows that this happened in the 1950s and the 1970s. Since 1983, recessions have been less frequent and expansions have been longer, causing the unemployment rate to regularly fall below its previous low point and generating a downward trend in the unemployment rate. 8 In February 2020, the unemployment rate fell to 3.5 percent, its lowest level since 1969.

I also estimate the relationship between recessions and the unemployment rate with a statistical model called a vector autoregression (VAR). I use the VAR to make forecasts of the unemployment rate under the hypothetical scenario that there will be no recessions in the future. I intend for this hypothetical scenario to match the spirit of the FOMC’s longer-run projections of the unemployment rate, which are made “in the absence of further shocks to the economy.” 9 My forecasts project that the unemployment rate will go to 3.6 percent after a long period with no recessions.

Recessions and Unemployment Rate Trends

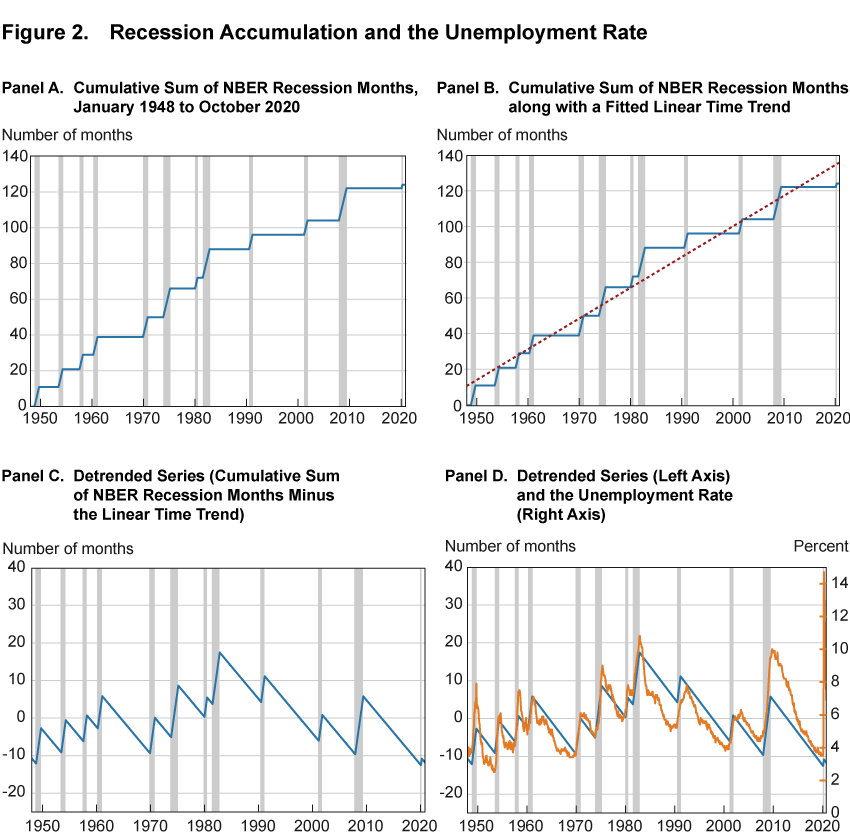

Figure 2 depicts a series of computations that result in a view of the alignment between recessions and the unemployment rate. This view of the alignment (panel D) highlights the intuition that frequent recessions, separated by short expansions, are associated with upward drift in the unemployment rate, while infrequent recessions, separated by long expansions, are associated with downward drift.

Note: Gray bars indicate recession periods. Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Unemployment Rate [UNRATE], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ( https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE ), NBER-based Recession Indicators for the United States from the Period following the Peak through the Trough [USREC], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ( https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/USREC ), and author’s calculations.

Panel A of figure 2 shows the cumulative sum of the National Bureau of Economic Research’s (NBER’s) recession months from January 1948 to October 2020. I define a recession as starting in the month following the NBER peak and ending in the month of an NBER trough. For the current period, the NBER announced a business cycle peak in February 2020 but has not announced a subsequent trough. In figure 2, I treat March and April 2020 as recession months. 10

In panel B of figure 2, I fit a linear time trend to the cumulative sum of the NBER recession months with ordinary least squares. This time trend gives an estimate of how quickly recessions accumulate on average. Then in panel C, I remove the linear time trend from the cumulative sum and show a detrended cumulative sum of NBER recession months. This detrended cumulative sum shows when recessions have accumulated more quickly and less quickly than average.

The detrended cumulative sum in panel C rises at a constant rate in every recessionary month and falls at a constant but slower rate in every expansionary month. This structure implies that this variable may not fall to its previous low point if a recession cuts an expansion short. As a result, frequent recessions, separated by short expansions, can cause this detrended cumulative sum to drift up over time. This upward drift occurs with the four recessions that begin in 1948, 1953, 1957, and 1960 and again with the four recessions that begin in 1970, 1973, 1980, and 1981. In other words, both 1948 to 1960 and 1970 to 1982 are 13-year periods where recessions accumulated more quickly than average. In contrast, recessions accumulated less quickly than average during the long expansions that occur mostly since 1983 and also in the 1960s. During these periods, the detrended cumulative sum falls below its low point from previous expansions, creating downward drifts in the series.

The periods of rapid recession accumulation, 1948 to 1960 and 1970 to 1982, are also periods when the unemployment rate trend rises in figure 1. In contrast, periods when recessions accumulate less quickly than average, the 1960s, 1983 to 2000, and the 2010s, are all periods when the unemployment rate trend falls in figure 1. To make this comparison between the accumulation of recessionary months and the unemployment rate more explicit, panel D shows the detrended cumulative sum of NBER recession months (left axis) along with the unemployment rate (right axis). The two series move closely together and have a correlation of about 0.7, even including the unusually large spike in the unemployment rate in April 2020.

A positive correlation between the frequency of recessionary months and the unemployment rate is not surprising. The NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Committee uses labor market variables when assigning business cycle peaks and troughs. 11 However, what is surprising about panel D is how closely the unemployment rate follows the detrended cumulative sum of recessionary months for such a long time—from 1948 to 2020. 12 This is surprising because the US labor market has been driven by a variety of economic shocks along with changing government policies, labor market regulations, and demographics; yet, the unemployment rate closely tracks the stable and linear structure of the detrended cumulative sum of recessionary months. As with the detrended cumulative sum of recessionary months, the unemployment rate rises quickly in recessions but falls slowly in expansions, and these features cause the unemployment rate to trend up with frequent recessions and trend down with infrequent recessions.

Longer-Run Unemployment Rate Projections

The results in the previous section show that the unemployment rate trend is aligned closely with how quickly recessionary months accumulate. Consequently, the unemployment rate trend may not be easily separated from the business cycle with statistical techniques that estimate slow-moving trends, such as in Hodrick and Prescott (1997), to offer just one example. This is because the unemployment rate’s trend is itself related to business cycles. 13 Instead, I model the unemployment rate and the NBER recession indicator, which has a value of zero in expansion months and a value of one in recession months, together with a statistical tool known as a VAR.

Using this VAR, I can produce longer-run projections of the unemployment rate in the spirit of the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections, which assumes that there will be no shocks to the economy in the future. I do this by producing forecasts of the unemployment rate while imposing that the recession indicator has a value of zero in all future periods. 14

There are two important steps for computing the forecasts. First, I use data from January 1948 to February 2020 to estimate the parameters of the VAR. These parameters establish the statistical relationship between the unemployment rate and the recession indicator, allowing me to predict how the unemployment rate will move in the future under the hypothetical scenario of no future recessions. Second, I choose the initial conditions as a starting point for my forecasts. 15 For example, I need to decide if I want to start my forecasts from a high unemployment rate or a low unemployment rate. Forecasters often use the most recent data as their starting points. However, they may also choose older data to check how accurate their projections would have been in the past.

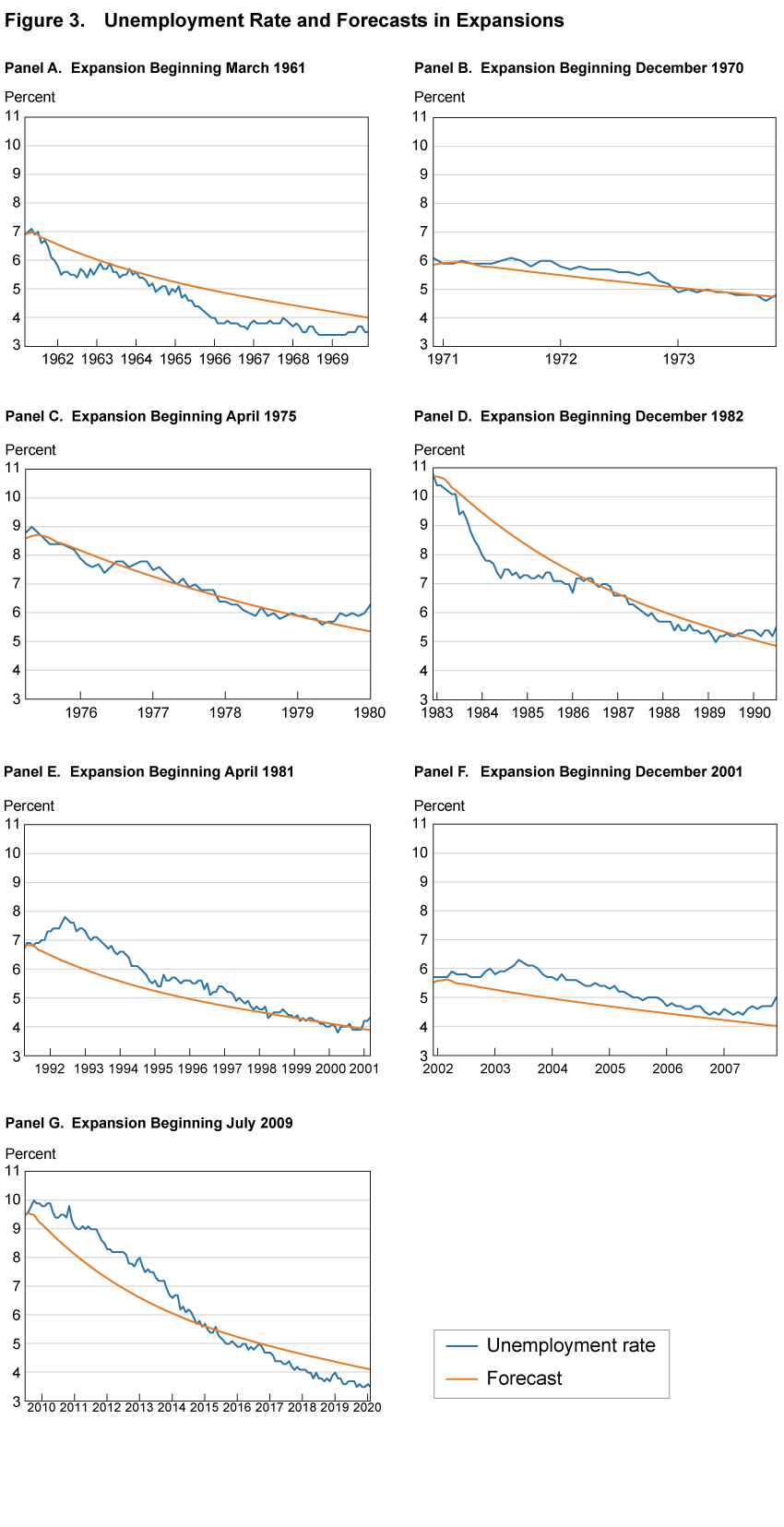

Figure 3 uses this latter approach. Each panel shows the unemployment rate for the 7 most recent NBER expansions. 16 In addition, it shows the forecasts from the VAR under the hypothetical scenario of no recessions. I use the months before each expansion started as the starting point for the forecasts.

Note: Forecasts are computed under the hypothetical scenario of no future recessions. Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Unemployment Rate [UNRATE], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ( https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE ), and author’s calculations.

While these forecasts do not perfectly track the unemployment rate over the course of an expansion, they generally match the downward trend of the unemployment rate in expansions. These forecasts also demonstrate relative accuracy in predicting where the unemployment rate will fall at the end of expansions. For the long expansion from 1991 to early 2001, the forecast predicts almost perfectly where the unemployment rate fell. For the other two longest expansions—1961 through 1969 and 2009 to early 2020—the forecast overpredicts where the unemployment rate fell to by about 0.6 percentage points.

The longest expansion shown in figure 3 (panel G)—July 2009 to February 2020—lasted 10 years and 8 months. In order to compute unemployment rate forecasts in the spirit of the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections, which assumes that there will be no shocks to the economy in the future, I next consider how low the unemployment rate could fall in expansions that last much longer than 10 years and 8 months. Specifically, I produce forecasts by imposing no recessions for 20 years. 17 In addition, I study the importance of the starting points for the forecasts by considering three different starting points. The first two are November 1982 and June 2009. These are the same starting points that I used in panels D and G of figure 3 and they coincide with the ends of the deepest recessions since 1948. The third starting point is February 2020, which is the last month in my estimation sample.

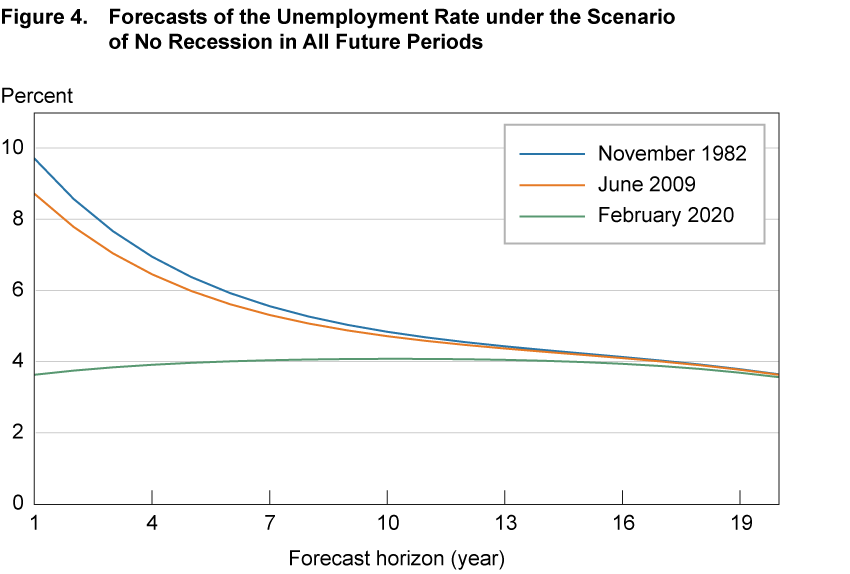

Figure 4 shows the 20-year forecasts. When using the November 1982 and June 2009 starting points, the forecasts start with the unemployment rate at high levels. This is natural as both of these starting points coincide with the end of recessions. In contrast, the forecasts generated with the February 2020 starting point start with a low level of the unemployment rate, a measure which is consistent with the healthy labor market at the start of 2020.

Note: The three lines correspond to three starting points: November 1982, June 2009, and December 2019. Source: Author’s calculations.

The forecasts generated with the November 1982 and June 2009 starting points move down over time. The forecasts generated from the February 2020 starting point rise very slightly before falling again. The forecasts with all three initial conditions become very similar at about 20 years, showing that the starting point does not affect how low the VAR projects the unemployment rate will fall as long as expansions are sufficiently long. For each of the three starting points, the VAR projects that the unemployment rate will be about 3.6 percent after 20 years without a recession. 18 That is, if one were to use this VAR to make a longer-run projection of the unemployment rate in the absence of further shocks to the economy as done in the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections, then one would project 3.6 percent. 19

The value of the projections in figure 4 is that they provide an answer to where the unemployment rate could fall in a hypothetical world in which recessions do not occur, which I approximate with 20-year forecasts with no recessions. Of course, other choices of forecast length are possible. With shorter forecasts, the starting point of the forecast still matters. As shown in figure 4, the forecasts generated with the November 1982 and June 2009 starting points are not all the way down to 3.6 percent until about 20 years. I have also considered longer forecasts; however, I do not show these forecasts here because they also yield unemployment rates at 3.6 percent.

To check the robustness of my results, I drop early portions of my estimation sample and recompute the long-run forecasts under the assumption of no future recessions. Using samples of January 1958 to February 2020, January 1968 to February 2020, and January 1978 to February 2020, I compute the long-run forecasts of the unemployment rate to be 3.6 percent, 3.8 percent, and 3.6 percent, respectively. These values indicate that the early portions of my sample do not have a big impact on the results. Alternatively, if I use January 1948 to June 2009 as my sample, the long-run forecast is 3.9 percent. This sample choice shows that the 2010s, which were part of the longest expansion in US history, have only a small impact on the results. Overall, the findings suggest that how low the unemployment rate can fall in an expansion appears to be quite stable over a variety of sample periods.

Finally, to highlight how the assumption of no future recessions affects the forecast of the unemployment rate, I also compute the 20-year forecast of the unemployment rate without this assumption. This unconditional forecast of the unemployment rate is 5.7 percent, more than 2 percentage points above the forecast that assumes no future recessions. Clearly, when making longer-run projections of the unemployment rate, such as those in the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections, conditioning upon future recessions can make large changes in the projection.

Conclusions

The unemployment rate in the United States falls slowly in expansions, and it may not reach its previous low point before the next recession begins. This feature suggests that the unemployment rate trends up with frequent recessions and trends down when recessions are infrequent. In this Commentary , I show that the US unemployment rate indeed trended up with the rapid accumulation of recessions prior to 1983 and then trended down again with the slow accumulation of recessions after 1983. In addition, I estimate the relationship between recessions and the unemployment rate with a VAR. Long-run forecasts from this VAR under the scenario of no future recessions can be used to produce longer-run projections of the unemployment rate in the spirit of the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections. I find that the unemployment rate moves to 3.6 percent in the absence of future recessions.

- I use a tuning parameter of 106 for the Hodrick and Prescott (1997) filter. This parameter is higher than what academic researchers often use for monthly data. I choose this higher value to highlight the lower frequency variation in the data. Using the filter from Müller and Watson (2015) with frequencies of 12 years or longer produces a similar picture. Return to 1

- For example, Weiner (1993) argues that the natural rate of unemployment was about 6.25 percent in 1993 but about 6.7 percent in 1980. An important point is that Weiner (1993) accounts for inflation in his estimate of the natural rate of unemployment. However, the HP filter in figure 1 does not account for inflation, nor do I throughout this Commentary . Return to 2

- For example, see the handbook chapter of Rogerson and Shimer (2011), which like many other studies, uses the Hodrick and Prescott (1997) filter to separate the trend and cycle components of the unemployment rate. Return to 3

- See https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/FOMC_LongerRunGoals.pdf . Return to 4

- For the April 2012 FOMC meeting, the range of longer-run unemployment rate projections was 4.9 percent to 6.0 percent. For the September 2020 FOMC meeting, this longer-run unemployment rate range had fallen to 3.5 percent to 4.7 percent. Return to 5

- Weiner (1993), also discussed in footnote 2, emphasizes demographic change. See Crump, Eusepi, Giannoni, and Șahin (2019) for more recent analysis and discussion of demographics and the unemployment rate. Return to 6

- Neftçi (1984) and Sichel (1993) have previously documented that the unemployment rate changes asymmetrically over the business cycle, rising quickly in recessions and falling slowly in expansions. This Commentary draws out the implication that this asymmetry can affect the longer-run trend in the unemployment rate. Return to 7

- Consistent with the slower accumulation of recession months, 1983 roughly corresponds to beginning of the “Great Moderation,” a period in US history in which many economic variables became less volatile (Kim and Nelson, 1999; McConnell and Perez-Quirós, 2000; Stock and Watson, 2002). The results in this Commentary link the Great Moderation to theoretical models of unemployment rate asymmetry, such as Dupraz, Nakamura, and Steinsson (2019) and Lepetit (2020), who find that more stable economic environments imply lower average unemployment rates. That is, the general downward trend in the unemployment rate after 1983 is consistent with theoretical models that show that the average unemployment rate can fall with a reduction in economic volatility. Return to 8

- See the notes to table 1 of https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20200916.pdf . Return to 9

- See https://www.nber.org/research/data/us-business-cycle-expansions-and-contractions for a list NBER peaks and troughs. Return to 10

- The NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Committee also uses gross domestic product, gross domestic income, personal consumption expenditures, and personal income less transfers when assigning business cycle peaks and troughs. For an example of the Business Cycle Dating Committee’s reasoning, see https://www.nber.org/news/business-cycle-dating-committee-announcement-june-8-2020 . Return to 11

- Consistent with this finding, Hall and Kudlyak (2020) document that the pace of reduction of the unemployment rate in expansions has been roughly stable for 70 years. Additionally, figure 2 implies that the pace of unemployment rate increases in recessions has also been roughly stable for 70 years. Return to 12

- Separating trends and business cycles is challenging for a wide variety of economic indicators. For example, Coibion, Gorodnichenko, and Ulate (2018) show that the Congressional Budget Office has historically made large changes to its measure of potential output around recessions. Return to 13

- I use the conditional forecasting approach in Doan, Litterman, and Sims (1983). I provide details of the VAR and the conditional forecasting exercise in a supplemental appendix. Return to 14

- Mathematically, these initial conditions are the values of the right-hand side variables in the VAR that are needed to produce the forecasts. See the supplemental appendix for additional details. Return to 15

- I exclude the expansion that began in August 1980 because this expansion lasted only one year. Return to 16

- I choose 20 years because that is the horizon at which forecasts appear to converge for all of the initial conditions in figure 4. If I only use a 15-year forecast horizon, the November 1982 and June 2009 initial conditions yield forecasts of the unemployment that fall to 3.8 percent, but it does not fall all the way to 3.6 percent as shown in figure 4. If I use horizons of 25 or 30 years, then the unemployment rate falls to 3.6 percent for all the initial conditions shown in figure 4, but it does not fall further. Return to 17

- This finding uses a VAR with 6 lags and is sensitive to the number of lags included in the VAR. I have checked lag lengths from 1 to 13 and found that the 20-year unemployment rate projection varies from a low of about 2.9 percent (with 13 lags) to a high of about 3.7 percent (with 1 lag). Hence, the results that I provide are conservative in the sense that different lag choices may yield materially lower unemployment rate projections, but none yields materially higher unemployment rate projections. Return to 18

- This long-run projection of 3.6 percent is very similar to Hall and Kudlyak’s (2020) steady-state unemployment rate of 3.5 percent. Hence, my results provide empirical support for Hall and Kudlyak’s choice of a steady state. In contrast, my long-run projection is materially above the steady-state of Dupraz, Nakamura, and Steinsson (2019), which is 4.6 percent. In addition, the conditional forecasts that I produce can provide data moments that may help researchers estimate labor market congestion functions as in Section 5.3 of Hall and Kudlyak (2020). Return to 19

- Coibion, Olivier, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, and Mauricio Ulate. 2018. “The Cyclical Sensitivity in Estimates of Potential Output.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity , Fall: 343–411. https://www.doi.org/10.1353/eca.2018.0020 .

- Crump, Richard K., Stefano Eusepi, Marc Giannoni, and Ayşegül Șahin. 2019. “A Unified Approach to Measuring u*.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity , Spring: 143–214. https://www.doi.org/10.1353/eca.2019.0002 .

- Doan, Thomas, Robert Litterman, and Christopher A. Sims. 1983. “Forecasting and Conditional Projection Using Realistic Prior Distributions.” NBER Working Paper, No. 1202. https://www.doi.org/10.3386/w1202 .

- Dupraz, Stéphane, Emi Nakamura, and Jón Steinsson. 2019. “A Plucking Model of Business Cycles.” NBER Working Paper, No. 26351. https://www.doi.org/10.3386/w26351 .

- Hall, Robert E., and Marianna Kudlyak. 2020. “Why Has the US Economy Recovered So Consistently from Every Recession in the Past 70 Years?” NBER Working Paper No. 27234. https://www.doi.org/10.3386/w27234 .

- Hodrick, Robert J., and Edward C. Prescott. 1997. “Postwar US Business Cycles: An Empirical Investigation.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking , 29(1): 1–16. https://www.doi.org/10.2307/2953682 .

- Kim, Chang-Jin, and Charles R. Nelson. 1999. “Has the US Economy Become More Stable? A Bayesian Approach Based on a Markov

- Switching Model of the Business Cycle.” Review of Economics and Statistics , 81(4): 608–616. https://www.doi.org/10.1162/003465399558472 .

- Lepetit, Antoine, 2020. “Asymmetric Unemployment Fluctuations and Monetary Policy Trade-Offs.” Review of Economic Dynamic s, 36: 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2019.07.005 .

- McConnell, Margaret M., and Gabriel Perez-Quirós. 2000. “Output Fluctuations in the United States: What Has Changed since the Early 1980s?” American Economic Review , 90(5): 1464–1476. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.5.1464 .

- Müller, Ulrich K. and Mark W. Watson, 2015. “Low-Frequency Econometrics.” NBER Working Paper, No. 21564. https://www.doi.org/10.3386/w21564 .

- Neftçi, Salih N. 1984. “Are Economic Time Series Asymmetric over the Business Cycle?” Journal of Political Economy , 92(2): 307–328. https://www.doi.org/10.1086/261226 .

- Rogerson, Richard, and Robert Shimer. 2011. “Search in Macroeconomic Models of the Labor Market.” Handbook of Labor Economics , Volume 4a, Chapter 7, 619-700. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/S0169-7218(11)00413-8 .

- Sichel, Daniel E. 1993. “Business Cycle Asymmetry: A Deeper Look.” Economic Inquiry , 31(2): 224–236. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.1993.tb00879.x .

- Stock, James H., and Mark W. Watson. 2002. “Has the Business Cycle Changed and Why?” NBER Macroeconomics Annual , 17: 159–218. https://www.doi.org/10.1086/ma.17.3585284 .

- Weiner, Stuart E. 1993. “New Estimates of the Natural Rate of Unemployment.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review , Fourth Quarter: 53–63. https://ideas.repec.org/a/fip/fedker/y1993iqivp53-69nv.78no.4.html .

Suggested Citation

Lunsford, Kurt G. 2021. “Recessions and the Trend in the US Unemployment Rate.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary 2021-01. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-ec-202101

Essay on Unemployment Rate

Introduction

The essay is focused on examining the issue of unemployment among people in various societies and countries around the world, the reasons for unemployment, types of unemployment, ways to overcome the issue of unemployment and examine the costs associated with unemployment. Unemployment is a major social issue among people in the economic market today, there are several reasons for unemployment in economics depending on the type of unemployment available, these can be directed to government, employer, supply of labor, among others. The types of unemployment can be directed to frictional unemployment, structural unemployment, cyclical unemployment, and seasonal unemployment. There is a need to solve the unemployment problem in the social economies, this can be done in several ways including enhancing political stability, promoting education, controlling the growth of population, among others. The issue of unemployment in the social economies has several costs ranging from loss of income among individuals, low standard of living among unemployed people, low production, and economic growth, among other costs.

Unemployment and reasons for unemployment

Unemployment is a major problem in various countries around the world, this is a situation whereby people do not have any work that can generate income and are actively searching for a job (Hauser & Burrows, 2018). Individuals in this situation are mostly employable and are actively searching for jobs. This can also include people who are working in jobs that are below their qualifications, experience, and satisfaction. The situation where there is a high level of unemployment will result in several economic distress and problems. The situation of unemployment hinders people to engage in productive work to facilitate development in the country. This will result in a decrease in economic productivity and development (Hauser & Burrows, 2018).

The two categories of unemployment are voluntary and involuntary unemployment, the situation where one moves out from a job to search for another is known as voluntary unemployment, and a situation where a person is laid off and now looking for a job is known as involuntary unemployment. Wolcott et al., (2020) in 2020, the coronavirus pandemic affected Singapore and the world, causing a high level of involuntary unemployment. There are several reasons for unemployment, inadequate job opportunities in a country can cause unemployment in the country. The slow economic development issue can result in unemployment, especially when the population growth is increasing.

The high growth of the population can result in unemployment challenges when the country is not developing and when fewer job opportunities are in the country. Also, people who depend on agriculture production work can become unemployed when the season is not favorable for plant growth. A decrease in industrialization and investment can account for unemployment in several countries that are not developing, the situation where there are few industries and investments are not available will have a severe influence on the employment of people in a developing country. Improper economic planning can also result in unemployment challenges, situations, where there is a gap between supply and demand of labor, which will result in unemployment.

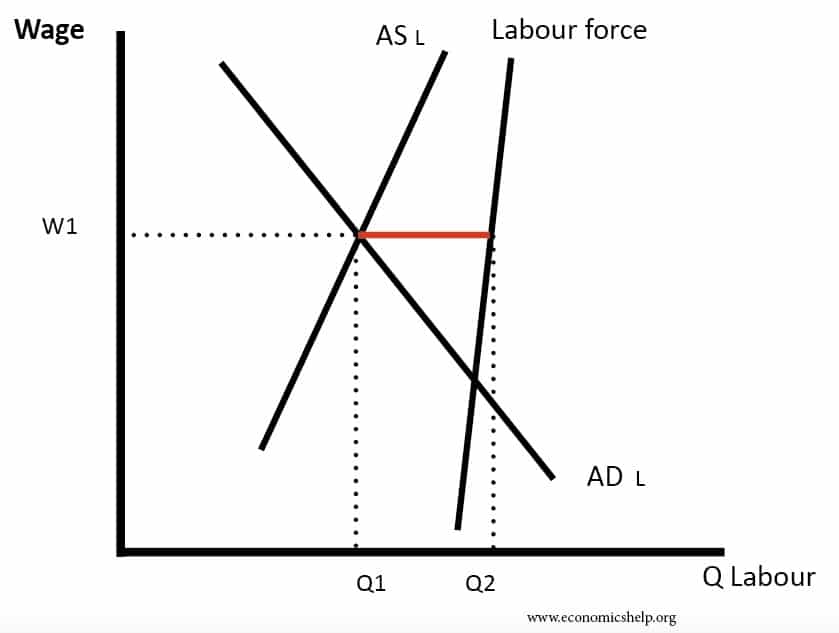

Various types of unemployment

Hauser & Burrows, (2018) Types of unemployment can include frictional, cyclical, structural, institutional, and seasonal unemployment. These types of unemployment are based on voluntary and involuntary unemployment. Frictional unemployment is a situation where a person voluntarily moves from one job to another in a country. The time spent to get another job can be linked to unemployment, it may take some time before the person gets another job. Some people move to another location to search for a new job which can take some time before getting the desired job. When fresh graduate students’ transit to search for a job, the time spent before getting a job is also linked to frictional unemployment. The time can be very short or longer depending on the availability of the job the applicant is seeking (Hwang, 2019).