An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

The Effect of COVID-19 on Education

Jacob hoofman.

a Wayne State University School of Medicine, 540 East Canfield, Detroit, MI 48201, USA

Elizabeth Secord

b Department of Pediatrics, Wayne Pediatrics, School of Medicine, Pediatrics Wayne State University, 400 Mack Avenue, Detroit, MI 48201, USA

COVID-19 has changed education for learners of all ages. Preliminary data project educational losses at many levels and verify the increased anxiety and depression associated with the changes, but there are not yet data on long-term outcomes. Guidance from oversight organizations regarding the safety and efficacy of new delivery modalities for education have been quickly forged. It is no surprise that the socioeconomic gaps and gaps for special learners have widened. The medical profession and other professions that teach by incrementally graduated internships are also severely affected and have had to make drastic changes.

- • Virtual learning has become a norm during COVID-19.

- • Children requiring special learning services, those living in poverty, and those speaking English as a second language have lost more from the pandemic educational changes.

- • For children with attention deficit disorder and no comorbidities, virtual learning has sometimes been advantageous.

- • Math learning scores are more likely to be affected than language arts scores by pandemic changes.

- • School meals, access to friends, and organized activities have also been lost with the closing of in-person school.

The transition to an online education during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic may bring about adverse educational changes and adverse health consequences for children and young adult learners in grade school, middle school, high school, college, and professional schools. The effects may differ by age, maturity, and socioeconomic class. At this time, we have few data on outcomes, but many oversight organizations have tried to establish guidelines, expressed concerns, and extrapolated from previous experiences.

General educational losses and disparities

Many researchers are examining how the new environment affects learners’ mental, physical, and social health to help compensate for any losses incurred by this pandemic and to better prepare for future pandemics. There is a paucity of data at this juncture, but some investigators have extrapolated from earlier school shutdowns owing to hurricanes and other natural disasters. 1

Inclement weather closures are estimated in some studies to lower middle school math grades by 0.013 to 0.039 standard deviations and natural disaster closures by up to 0.10 standard deviation decreases in overall achievement scores. 2 The data from inclement weather closures did show a more significant decrease for children dependent on school meals, but generally the data were not stratified by socioeconomic differences. 3 , 4 Math scores are impacted overall more negatively by school absences than English language scores for all school closures. 4 , 5

The Northwest Evaluation Association is a global nonprofit organization that provides research-based assessments and professional development for educators. A team of researchers at Stanford University evaluated Northwest Evaluation Association test scores for students in 17 states and the District of Columbia in the Fall of 2020 and estimated that the average student had lost one-third of a year to a full year's worth of learning in reading, and about three-quarters of a year to more than 1 year in math since schools closed in March 2020. 5

With school shifted from traditional attendance at a school building to attendance via the Internet, families have come under new stressors. It is increasingly clear that families depended on schools for much more than math and reading. Shelter, food, health care, and social well-being are all part of what children and adolescents, as well as their parents or guardians, depend on schools to provide. 5 , 6

Many families have been impacted negatively by the loss of wages, leading to food insecurity and housing insecurity; some of loss this is a consequence of the need for parents to be at home with young children who cannot attend in-person school. 6 There is evidence that this economic instability is leading to an increase in depression and anxiety. 7 In 1 survey, 34.71% of parents reported behavioral problems in their children that they attributed to the pandemic and virtual schooling. 8

Children have been infected with and affected by coronavirus. In the United States, 93,605 students tested positive for COVID-19, and it was reported that 42% were Hispanic/Latino, 32% were non-Hispanic White, and 17% were non-Hispanic Black, emphasizing a disproportionate effect for children of color. 9 COVID infection itself is not the only issue that affects children’s health during the pandemic. School-based health care and school-based meals are lost when school goes virtual and children of lower socioeconomic class are more severely affected by these losses. Although some districts were able to deliver school meals, school-based health care is a primary source of health care for many children and has left some chronic conditions unchecked during the pandemic. 10

Many families report that the stress of the pandemic has led to a poorer diet in children with an increase in the consumption of sweet and fried foods. 11 , 12 Shelter at home orders and online education have led to fewer exercise opportunities. Research carried out by Ammar and colleagues 12 found that daily sitting had increased from 5 to 8 hours a day and binge eating, snacking, and the number of meals were all significantly increased owing to lockdown conditions and stay-at-home initiatives. There is growing evidence in both animal and human models that diets high in sugar and fat can play a detrimental role in cognition and should be of increased concern in light of the pandemic. 13

The family stress elicited by the COVID-19 shutdown is a particular concern because of compiled evidence that adverse life experiences at an early age are associated with an increased likelihood of mental health issues as an adult. 14 There is early evidence that children ages 6 to 18 years of age experienced a significant increase in their expression of “clinginess, irritability, and fear” during the early pandemic school shutdowns. 15 These emotions associated with anxiety may have a negative impact on the family unit, which was already stressed owing to the pandemic.

Another major concern is the length of isolation many children have had to endure since the pandemic began and what effects it might have on their ability to socialize. The school, for many children, is the agent for forming their social connections as well as where early social development occurs. 16 Noting that academic performance is also declining the pandemic may be creating a snowball effect, setting back children without access to resources from which they may never recover, even into adulthood.

Predictions from data analysis of school absenteeism, summer breaks, and natural disaster occurrences are imperfect for the current situation, but all indications are that we should not expect all children and adolescents to be affected equally. 4 , 5 Although some children and adolescents will likely suffer no long-term consequences, COVID-19 is expected to widen the already existing educational gap from socioeconomic differences, and children with learning differences are expected to suffer more losses than neurotypical children. 4 , 5

Special education and the COVID-19 pandemic

Although COVID-19 has affected all levels of education reception and delivery, children with special needs have been more profoundly impacted. Children in the United States who have special needs have legal protection for appropriate education by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. 17 , 18 Collectively, this legislation is meant to allow for appropriate accommodations, services, modifications, and specialized academic instruction to ensure that “every child receives a free appropriate public education . . . in the least restrictive environment.” 17

Children with autism usually have applied behavioral analysis (ABA) as part of their individualized educational plan. ABA therapists for autism use a technique of discrete trial training that shapes and rewards incremental changes toward new behaviors. 19 Discrete trial training involves breaking behaviors into small steps and repetition of rewards for small advances in the steps toward those behaviors. It is an intensive one-on-one therapy that puts a child and therapist in close contact for many hours at a time, often 20 to 40 hours a week. This therapy works best when initiated at a young age in children with autism and is often initiated in the home. 19

Because ABA workers were considered essential workers from the early days of the pandemic, organizations providing this service had the responsibility and the freedom to develop safety protocols for delivery of this necessary service and did so in conjunction with certifying boards. 20

Early in the pandemic, there were interruptions in ABA followed by virtual visits, and finally by in-home therapy with COVID-19 isolation precautions. 21 Although the efficacy of virtual visits for ABA therapy would empirically seem to be inferior, there are few outcomes data available. The balance of safety versus efficacy quite early turned to in-home services with interruptions owing to illness and decreased therapist availability owing to the pandemic. 21 An overarching concern for children with autism is the possible loss of a window of opportunity to intervene early. Families of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder report increased stress compared with families of children with other disabilities before the pandemic, and during the pandemic this burden has increased with the added responsibility of monitoring in-home schooling. 20

Early data on virtual schooling children with attention deficit disorder (ADD) and attention deficit with hyperactivity (ADHD) shows that adolescents with ADD/ADHD found the switch to virtual learning more anxiety producing and more challenging than their peers. 22 However, according to a study in Ireland, younger children with ADD/ADHD and no other neurologic or psychiatric diagnoses who were stable on medication tended to report less anxiety with at-home schooling and their parents and caregivers reported improved behavior during the pandemic. 23 An unexpected benefit of shelter in home versus shelter in place may be to identify these stressors in face-to-face school for children with ADD/ADHD. If children with ADD/ADHD had an additional diagnosis of autism or depression, they reported increased anxiety with the school shutdown. 23 , 24

Much of the available literature is anticipatory guidance for in-home schooling of children with disabilities rather than data about schooling during the pandemic. The American Academy of Pediatrics published guidance advising that, because 70% of students with ADHD have other conditions, such as learning differences, oppositional defiant disorder, or depression, they may have very different responses to in home schooling which are a result of the non-ADHD diagnosis, for example, refusal to attempt work for children with oppositional defiant disorder, severe anxiety for those with depression and or anxiety disorders, and anxiety and perseveration for children with autism. 25 Children and families already stressed with learning differences have had substantial challenges during the COVID-19 school closures.

High school, depression, and COVID-19

High schoolers have lost a great deal during this pandemic. What should have been a time of establishing more independence has been hampered by shelter-in-place recommendations. Graduations, proms, athletic events, college visits, and many other social and educational events have been altered or lost and cannot be recaptured.

Adolescents reported higher rates of depression and anxiety associated with the pandemic, and in 1 study 14.4% of teenagers report post-traumatic stress disorder, whereas 40.4% report having depression and anxiety. 26 In another survey adolescent boys reported a significant decrease in life satisfaction from 92% before COVID to 72% during lockdown conditions. For adolescent girls, the decrease in life satisfaction was from 81% before COVID to 62% during the pandemic, with the oldest teenage girls reporting the lowest life satisfaction values during COVID-19 restrictions. 27 During the school shutdown for COVID-19, 21% of boys and 27% of girls reported an increase in family arguments. 26 Combine all of these reports with decreasing access to mental health services owing to pandemic restrictions and it becomes a complicated matter for parents to address their children's mental health needs as well as their educational needs. 28

A study conducted in Norway measured aspects of socialization and mood changes in adolescents during the pandemic. The opportunity for prosocial action was rated on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 6 (very much) based on how well certain phrases applied to them, for example, “I comforted a friend yesterday,” “Yesterday I did my best to care for a friend,” and “Yesterday I sent a message to a friend.” They also ranked mood by rating items on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (very well) as items reflected their mood. 29 They found that adolescents showed an overall decrease in empathic concern and opportunity for prosocial actions, as well as a decrease in mood ratings during the pandemic. 29

A survey of 24,155 residents of Michigan projected an escalation of suicide risk for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender youth as well as those youth questioning their sexual orientation (LGBTQ) associated with increased social isolation. There was also a 66% increase in domestic violence for LGBTQ youth during shelter in place. 30 LGBTQ youth are yet another example of those already at increased risk having disproportionate effects of the pandemic.

Increased social media use during COVID-19, along with traditional forms of education moving to digital platforms, has led to the majority of adolescents spending significantly more time in front of screens. Excessive screen time is well-known to be associated with poor sleep, sedentary habits, mental health problems, and physical health issues. 31 With decreased access to physical activity, especially in crowded inner-city areas, and increased dependence on screen time for schooling, it is more difficult to craft easy solutions to the screen time issue.

During these times, it is more important than ever for pediatricians to check in on the mental health of patients with queries about how school is going, how patients are keeping contact with peers, and how are they processing social issues related to violence. Queries to families about the need for assistance with food insecurity, housing insecurity, and access to mental health services are necessary during this time of public emergency.

Medical school and COVID-19

Although medical school is an adult schooling experience, it affects not only the medical profession and our junior colleagues, but, by extrapolation, all education that requires hands-on experience or interning, and has been included for those reasons.

In the new COVID-19 era, medical schools have been forced to make drastic and quick changes to multiple levels of their curriculum to ensure both student and patient safety during the pandemic. Students entering their clinical rotations have had the most drastic alteration to their experience.

COVID-19 has led to some of the same changes high schools and colleges have adopted, specifically, replacement of large in-person lectures with small group activities small group discussion and virtual lectures. 32 The transition to an online format for medical education has been rapid and impacted both students and faculty. 33 , 34 In a survey by Singh and colleagues, 33 of the 192 students reporting 43.9% found online lectures to be poorer than physical classrooms during the pandemic. In another report by Shahrvini and colleagues, 35 of 104 students surveyed, 74.5% students felt disconnected from their medical school and their peers and 43.3% felt that they were unprepared for their clerkships. Although there are no pre-COVID-19 data for comparison, it is expected that the COVID-19 changes will lead to increased insecurity and feelings of poor preparation for clinical work.

Gross anatomy is a well-established tradition within the medical school curriculum and one that is conducted almost entirely in person and in close quarters around a cadaver. Harmon and colleagues 36 surveyed 67 gross anatomy educators and found that 8% were still holding in-person sessions and 34 ± 43% transitioned to using cadaver images and dissecting videos that could be accessed through the Internet.

Many third- and fourth-year medical students have seen periods of cancellation for clinical rotations and supplementation with online learning, telemedicine, or virtual rounds owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. 37 A study from Shahrvini and colleagues 38 found that an unofficial document from Reddit (a widely used social network platform with a subgroup for medical students and residents) reported that 75% of medical schools had canceled clinical activities for third- and fourth-year students for some part of 2020. In another survey by Harries and colleagues, 39 of the 741 students who responded, 93.7% were not involved in clinical rotations with in-person patient contact. The reactions of students varied, with 75.8% admitting to agreeing with the decision, 34.7% feeling guilty, and 27.0% feeling relieved. 39 In the same survey, 74.7% of students felt that their medical education had been disrupted, 84.1% said they felt increased anxiety, and 83.4% would accept the risk of COVID-19 infection if they were able to return to the clinical setting. 39

Since the start of the pandemic, medical schools have had to find new and innovative ways to continue teaching and exposing students to clinical settings. The use of electronic conferencing services has been critical to continuing education. One approach has been to turn to online applications like Google Hangouts, which come at no cost and offer a wide variety of tools to form an integrative learning environment. 32 , 37 , 40 Schools have also adopted a hybrid model of teaching where lectures can be prerecorded then viewed by the student asynchronously on their own time followed by live virtual lectures where faculty can offer question-and-answer sessions related to the material. By offering this new format, students have been given more flexibility in terms of creating a schedule that suits their needs and may decrease stress. 37

Although these changes can be a hurdle to students and faculty, it might prove to be beneficial for the future of medical training in some ways. Telemedicine is a growing field, and the American Medical Association and other programs have endorsed its value. 41 Telemedicine visits can still be used to take a history, conduct a basic visual physical examination, and build rapport, as well as performing other aspects of the clinical examination during a pandemic, and will continue to be useful for patients unable to attend regular visits at remote locations. Learning effectively now how to communicate professionally and carry out telemedicine visits may better prepare students for a future where telemedicine is an expectation and allow students to learn the limitations as well as the advantages of this modality. 41

Pandemic changes have strongly impacted the process of college applications, medical school applications, and residency applications. 32 For US medical residencies, 72% of applicants will, if the pattern from 2016 to 2019 continues, move between states or countries. 42 This level of movement is increasingly dangerous given the spread of COVID-19 and the lack of currently accepted procedures to carry out such a mass migration safely. The same follows for medical schools and universities.

We need to accept and prepare for the fact that medial students as well as other learners who require in-person training may lack some skills when they enter their profession. These skills will have to be acquired during a later phase of training. We may have less skilled entry-level resident physicians and nurses in our hospitals and in other clinical professions as well.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected and will continue to affect the delivery of knowledge and skills at all levels of education. Although many children and adult learners will likely compensate for this interruption of traditional educational services and adapt to new modalities, some will struggle. The widening of the gap for those whose families cannot absorb the teaching and supervision of education required for in-home education because they lack the time and skills necessary are not addressed currently. The gap for those already at a disadvantage because of socioeconomic class, language, and special needs are most severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic school closures and will have the hardest time compensating. As pediatricians, it is critical that we continue to check in with our young patients about how they are coping and what assistance we can guide them toward in our communities.

Clinics care points

- • Learners and educators at all levels of education have been affected by COVID-19 restrictions with rapid adaptations to virtual learning platforms.

- • The impact of COVID-19 on learners is not evenly distributed and children of racial minorities, those who live in poverty, those requiring special education, and children who speak English as a second language are more negatively affected by the need for remote learning.

- • Math scores are more impacted than language arts scores by previous school closures and thus far by these shutdowns for COVID-19.

- • Anxiety and depression have increased in children and particularly in adolescents as a result of COVID-19 itself and as a consequence of school changes.

- • Pediatricians should regularly screen for unmet needs in their patients during the pandemic, such as food insecurity with the loss of school meals, an inability to adapt to remote learning and increased computer time, and heightened anxiety and depression as results of school changes.

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Mission: Recovering Education in 2021

THE CONTEXT

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused abrupt and profound changes around the world. This is the worst shock to education systems in decades, with the longest school closures combined with looming recession. It will set back progress made on global development goals, particularly those focused on education. The economic crises within countries and globally will likely lead to fiscal austerity, increases in poverty, and fewer resources available for investments in public services from both domestic expenditure and development aid. All of this will lead to a crisis in human development that continues long after disease transmission has ended.

Disruptions to education systems over the past year have already driven substantial losses and inequalities in learning. All the efforts to provide remote instruction are laudable, but this has been a very poor substitute for in-person learning. Even more concerning, many children, particularly girls, may not return to school even when schools reopen. School closures and the resulting disruptions to school participation and learning are projected to amount to losses valued at $10 trillion in terms of affected children’s future earnings. Schools also play a critical role around the world in ensuring the delivery of essential health services and nutritious meals, protection, and psycho-social support. Thus, school closures have also imperilled children’s overall wellbeing and development, not just their learning.

It’s not enough for schools to simply reopen their doors after COVID-19. Students will need tailored and sustained support to help them readjust and catch-up after the pandemic. We must help schools prepare to provide that support and meet the enormous challenges of the months ahead. The time to act is now; the future of an entire generation is at stake.

THE MISSION

Mission objective: To enable all children to return to school and to a supportive learning environment, which also addresses their health and psychosocial well-being and other needs.

Timeframe : By end 2021.

Scope : All countries should reopen schools for complete or partial in-person instruction and keep them open. The Partners - UNESCO , UNICEF , and the World Bank - will join forces to support countries to take all actions possible to plan, prioritize, and ensure that all learners are back in school; that schools take all measures to reopen safely; that students receive effective remedial learning and comprehensive services to help recover learning losses and improve overall welfare; and their teachers are prepared and supported to meet their learning needs.

Three priorities:

1. All children and youth are back in school and receive the tailored services needed to meet their learning, health, psychosocial wellbeing, and other needs.

Challenges : School closures have put children’s learning, nutrition, mental health, and overall development at risk. Closed schools also make screening and delivery for child protection services more difficult. Some students, particularly girls, are at risk of never returning to school.

Areas of action : The Partners will support the design and implementation of school reopening strategies that include comprehensive services to support children’s education, health, psycho-social wellbeing, and other needs.

Targets and indicators

2. All children receive support to catch up on lost learning.

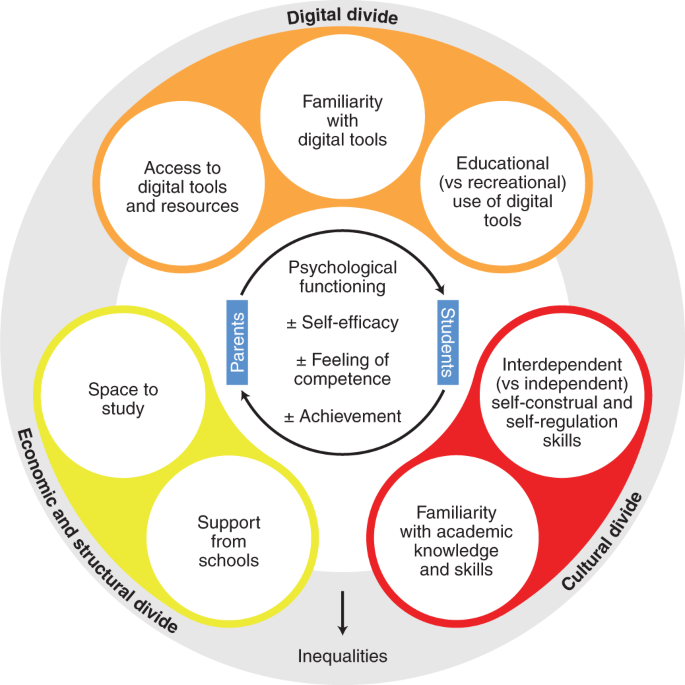

Challenges : Most children have lost substantial instructional time and may not be ready for curricula that were age- and grade- appropriate prior to the pandemic. They will require remedial instruction to get back on track. The pandemic also revealed a stark digital divide that schools can play a role in addressing by ensuring children have digital skills and access.

Areas of action : The Partners will (i) support the design and implementation of large-scale remedial learning at different levels of education, (ii) launch an open-access, adaptable learning assessment tool that measures learning losses and identifies learners’ needs, and (iii) support the design and implementation of digital transformation plans that include components on both infrastructure and ways to use digital technology to accelerate the development of foundational literacy and numeracy skills. Incorporating digital technologies to teach foundational skills could complement teachers’ efforts in the classroom and better prepare children for future digital instruction.

While incorporating remedial education, social-emotional learning, and digital technology into curricula by the end of 2021 will be a challenge for most countries, the Partners agree that these are aspirational targets that they should be supporting countries to achieve this year and beyond as education systems start to recover from the current crisis.

3. All teachers are prepared and supported to address learning losses among their students and to incorporate digital technology into their teaching.

Challenges : Teachers are in an unprecedented situation in which they must make up for substantial loss of instructional time from the previous school year and teach the current year’s curriculum. They must also protect their own health in school. Teachers will need training, coaching, and other means of support to get this done. They will also need to be prioritized for the COVID-19 vaccination, after frontline personnel and high-risk populations. School closures also demonstrated that in addition to digital skills, teachers may also need support to adapt their pedagogy to deliver instruction remotely.

Areas of action : The Partners will advocate for teachers to be prioritized in COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, after frontline personnel and high-risk populations, and provide capacity-development on pedagogies for remedial learning and digital and blended teaching approaches.

Country level actions and global support

UNESCO, UNICEF, and World Bank are joining forces to support countries to achieve the Mission, leveraging their expertise and actions on the ground to support national efforts and domestic funding.

Country Level Action

1. Mobilize team to support countries in achieving the three priorities

The Partners will collaborate and act at the country level to support governments in accelerating actions to advance the three priorities.

2. Advocacy to mobilize domestic resources for the three priorities

The Partners will engage with governments and decision-makers to prioritize education financing and mobilize additional domestic resources.

Global level action

1. Leverage data to inform decision-making

The Partners will join forces to conduct surveys; collect data; and set-up a global, regional, and national real-time data-warehouse. The Partners will collect timely data and analytics that provide access to information on school re-openings, learning losses, drop-outs, and transition from school to work, and will make data available to support decision-making and peer-learning.

2. Promote knowledge sharing and peer-learning in strengthening education recovery

The Partners will join forces in sharing the breadth of international experience and scaling innovations through structured policy dialogue, knowledge sharing, and peer learning actions.

The time to act on these priorities is now. UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank are partnering to help drive that action.

Last Updated: Mar 30, 2021

- (BROCHURE, in English) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (BROCHURE, in French) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (BROCHURE, in Spanish) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (BLOG) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (VIDEO, Arabic) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (VIDEO, French) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (VIDEO, Spanish) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- World Bank Education and COVID-19

- World Bank Blogs on Education

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Footnote leads to exploration of start of for-profit prisons in N.Y.

Should NATO step up role in Russia-Ukraine war?

It’s on Facebook, and it’s complicated

Rubén Rodriguez/Unsplash

Time to fix American education with race-for-space resolve

Harvard Staff Writer

Paul Reville says COVID-19 school closures have turned a spotlight on inequities and other shortcomings

This is part of our Coronavirus Update series in which Harvard specialists in epidemiology, infectious disease, economics, politics, and other disciplines offer insights into what the latest developments in the COVID-19 outbreak may bring.

As former secretary of education for Massachusetts, Paul Reville is keenly aware of the financial and resource disparities between districts, schools, and individual students. The school closings due to coronavirus concerns have turned a spotlight on those problems and how they contribute to educational and income inequality in the nation. The Gazette talked to Reville, the Francis Keppel Professor of Practice of Educational Policy and Administration at Harvard Graduate School of Education , about the effects of the pandemic on schools and how the experience may inspire an overhaul of the American education system.

Paul Reville

GAZETTE: Schools around the country have closed due to the coronavirus pandemic. Do these massive school closures have any precedent in the history of the United States?

REVILLE: We’ve certainly had school closures in particular jurisdictions after a natural disaster, like in New Orleans after the hurricane. But on this scale? No, certainly not in my lifetime. There were substantial closings in many places during the 1918 Spanish Flu, some as long as four months, but not as widespread as those we’re seeing today. We’re in uncharted territory.

GAZETTE: What lessons did school districts around the country learn from school closures in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, and other similar school closings?

REVILLE: I think the lessons we’ve learned are that it’s good [for school districts] to have a backup system, if they can afford it. I was talking recently with folks in a district in New Hampshire where, because of all the snow days they have in the wintertime, they had already developed a backup online learning system. That made the transition, in this period of school closure, a relatively easy one for them to undertake. They moved seamlessly to online instruction.

Most of our big systems don’t have this sort of backup. Now, however, we’re not only going to have to construct a backup to get through this crisis, but we’re going to have to develop new, permanent systems, redesigned to meet the needs which have been so glaringly exposed in this crisis. For example, we have always had large gaps in students’ learning opportunities after school, weekends, and in the summer. Disadvantaged students suffer the consequences of those gaps more than affluent children, who typically have lots of opportunities to fill in those gaps. I’m hoping that we can learn some things through this crisis about online delivery of not only instruction, but an array of opportunities for learning and support. In this way, we can make the most of the crisis to help redesign better systems of education and child development.

GAZETTE: Is that one of the silver linings of this public health crisis?

REVILLE: In politics we say, “Never lose the opportunity of a crisis.” And in this situation, we don’t simply want to frantically struggle to restore the status quo because the status quo wasn’t operating at an effective level and certainly wasn’t serving all of our children fairly. There are things we can learn in the messiness of adapting through this crisis, which has revealed profound disparities in children’s access to support and opportunities. We should be asking: How do we make our school, education, and child-development systems more individually responsive to the needs of our students? Why not construct a system that meets children where they are and gives them what they need inside and outside of school in order to be successful? Let’s take this opportunity to end the “one size fits all” factory model of education.

GAZETTE: How seriously are students going to be set back by not having formal instruction for at least two months, if not more?

“The best that can come of this is a new paradigm shift in terms of the way in which we look at education, because children’s well-being and success depend on more than just schooling,” Paul Reville said of the current situation. “We need to look holistically, at the entirety of children’s lives.”

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

REVILLE: The first thing to consider is that it’s going to be a variable effect. We tend to regard our school systems uniformly, but actually schools are widely different in their operations and impact on children, just as our students themselves are very different from one another. Children come from very different backgrounds and have very different resources, opportunities, and support outside of school. Now that their entire learning lives, as well as their actual physical lives, are outside of school, those differences and disparities come into vivid view. Some students will be fine during this crisis because they’ll have high-quality learning opportunities, whether it’s formal schooling or informal homeschooling of some kind coupled with various enrichment opportunities. Conversely, other students won’t have access to anything of quality, and as a result will be at an enormous disadvantage. Generally speaking, the most economically challenged in our society will be the most vulnerable in this crisis, and the most advantaged are most likely to survive it without losing too much ground.

GAZETTE: Schools in Massachusetts are closed until May 4. Some people are saying they should remain closed through the end of the school year. What’s your take on this?

REVILLE: That should be a medically based judgment call that will be best made several weeks from now. If there’s evidence to suggest that students and teachers can safely return to school, then I’d say by all means. However, that seems unlikely.

GAZETTE: The digital divide between students has become apparent as schools have increasingly turned to online instruction. What can school systems do to address that gap?

REVILLE: Arguably, this is something that schools should have been doing a long time ago, opening up the whole frontier of out-of-school learning by virtue of making sure that all students have access to the technology and the internet they need in order to be connected in out-of-school hours. Students in certain school districts don’t have those affordances right now because often the school districts don’t have the budget to do this, but federal, state, and local taxpayers are starting to see the imperative for coming together to meet this need.

Twenty-first century learning absolutely requires technology and internet. We can’t leave this to chance or the accident of birth. All of our children should have the technology they need to learn outside of school. Some communities can take it for granted that their children will have such tools. Others who have been unable to afford to level the playing field are now finding ways to step up. Boston, for example, has bought 20,000 Chromebooks and is creating hotspots around the city where children and families can go to get internet access. That’s a great start but, in the long run, I think we can do better than that. At the same time, many communities still need help just to do what Boston has done for its students.

Communities and school districts are going to have to adapt to get students on a level playing field. Otherwise, many students will continue to be at a huge disadvantage. We can see this playing out now as our lower-income and more heterogeneous school districts struggle over whether to proceed with online instruction when not everyone can access it. Shutting down should not be an option. We have to find some middle ground, and that means the state and local school districts are going to have to act urgently and nimbly to fill in the gaps in technology and internet access.

GAZETTE : What can parents can do to help with the homeschooling of their children in the current crisis?

“In this situation, we don’t simply want to frantically struggle to restore the status quo because the status quo wasn’t operating at an effective level and certainly wasn’t serving all of our children fairly.”

More like this

The collective effort

Notes from the new normal

‘If you remain mostly upright, you are doing it well enough’

REVILLE: School districts can be helpful by giving parents guidance about how to constructively use this time. The default in our education system is now homeschooling. Virtually all parents are doing some form of homeschooling, whether they want to or not. And the question is: What resources, support, or capacity do they have to do homeschooling effectively? A lot of parents are struggling with that.

And again, we have widely variable capacity in our families and school systems. Some families have parents home all day, while other parents have to go to work. Some school systems are doing online classes all day long, and the students are fully engaged and have lots of homework, and the parents don’t need to do much. In other cases, there is virtually nothing going on at the school level, and everything falls to the parents. In the meantime, lots of organizations are springing up, offering different kinds of resources such as handbooks and curriculum outlines, while many school systems are coming up with guidance documents to help parents create a positive learning environment in their homes by engaging children in challenging activities so they keep learning.

There are lots of creative things that can be done at home. But the challenge, of course, for parents is that they are contending with working from home, and in other cases, having to leave home to do their jobs. We have to be aware that families are facing myriad challenges right now. If we’re not careful, we risk overloading families. We have to strike a balance between what children need and what families can do, and how you maintain some kind of work-life balance in the home environment. Finally, we must recognize the equity issues in the forced overreliance on homeschooling so that we avoid further disadvantaging the already disadvantaged.

GAZETTE: What has been the biggest surprise for you thus far?

REVILLE: One that’s most striking to me is that because schools are closed, parents and the general public have become more aware than at any time in my memory of the inequities in children’s lives outside of school. Suddenly we see front-page coverage about food deficits, inadequate access to health and mental health, problems with housing stability, and access to educational technology and internet. Those of us in education know these problems have existed forever. What has happened is like a giant tidal wave that came and sucked the water off the ocean floor, revealing all these uncomfortable realities that had been beneath the water from time immemorial. This newfound public awareness of pervasive inequities, I hope, will create a sense of urgency in the public domain. We need to correct for these inequities in order for education to realize its ambitious goals. We need to redesign our systems of child development and education. The most obvious place to start for schools is working on equitable access to educational technology as a way to close the digital-learning gap.

GAZETTE: You’ve talked about some concrete changes that should be considered to level the playing field. But should we be thinking broadly about education in some new way?

REVILLE: The best that can come of this is a new paradigm shift in terms of the way in which we look at education, because children’s well-being and success depend on more than just schooling. We need to look holistically, at the entirety of children’s lives. In order for children to come to school ready to learn, they need a wide array of essential supports and opportunities outside of school. And we haven’t done a very good job of providing these. These education prerequisites go far beyond the purview of school systems, but rather are the responsibility of communities and society at large. In order to learn, children need equal access to health care, food, clean water, stable housing, and out-of-school enrichment opportunities, to name just a few preconditions. We have to reconceptualize the whole job of child development and education, and construct systems that meet children where they are and give them what they need, both inside and outside of school, in order for all of them to have a genuine opportunity to be successful.

Within this coronavirus crisis there is an opportunity to reshape American education. The only precedent in our field was when the Sputnik went up in 1957, and suddenly, Americans became very worried that their educational system wasn’t competitive with that of the Soviet Union. We felt vulnerable, like our defenses were down, like a nation at risk. And we decided to dramatically boost the involvement of the federal government in schooling and to increase and improve our scientific curriculum. We decided to look at education as an important factor in human capital development in this country. Again, in 1983, the report “Nation at Risk” warned of a similar risk: Our education system wasn’t up to the demands of a high-skills/high-knowledge economy.

We tried with our education reforms to build a 21st-century education system, but the results of that movement have been modest. We are still a nation at risk. We need another paradigm shift, where we look at our goals and aspirations for education, which are summed up in phrases like “No Child Left Behind,” “Every Student Succeeds,” and “All Means All,” and figure out how to build a system that has the capacity to deliver on that promise of equity and excellence in education for all of our students, and all means all. We’ve got that opportunity now. I hope we don’t fail to take advantage of it in a misguided rush to restore the status quo.

This interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity.

Share this article

You might like.

Historian traces 19th-century murder case that brought together historical figures, helped shape American thinking on race, violence, incarceration

National security analysts outline stakes ahead of July summit

‘Spermworld’ documentary examines motivations of prospective parents, volunteer donors who connect through private group page

Everything counts!

New study finds step-count and time are equally valid in reducing health risks

Five alumni elected to the Board of Overseers

Six others join Alumni Association board

Glimpse of next-generation internet

Physicists demo first metro-area quantum computer network in Boston

- Arts & Culture

- Civic Engagement

- Economic Development

- Environment

- Human Rights

- Social Services

- Water & Sanitation

- Foundations

- Nonprofits & NGOs

- Social Enterprise

- Collaboration

- Design Thinking

- Impact Investing

- Measurement & Evaluation

- Organizational Development

- Philanthropy & Funding

- Current Issue

- Sponsored Supplements

- Global Editions

- In-Depth Series

- Stanford PACS

- Submission Guidelines

A Better Education for All During—and After—the COVID-19 Pandemic

Research from the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) and its partners shows how to help children learn amid erratic access to schools during a pandemic, and how those solutions may make progress toward the Sustainable Development Goal of ensuring a quality education for all by 2030.

- order reprints

- related stories

By Radhika Bhula & John Floretta Oct. 16, 2020

Five years into the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the world is nowhere near to ensuring a quality education for all by 2030. Impressive gains in enrollment and attendance over recent decades have not translated into corresponding gains in learning. The World Bank’s metric of "learning poverty," which refers to children who cannot read and understand a simple text by age 10, is a staggering 80 percent in low-income countries .

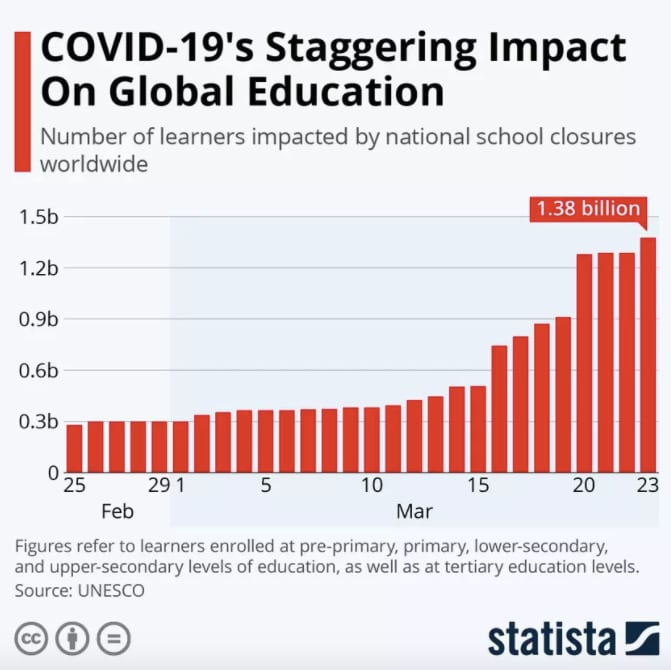

The COVID-19 crisis is exacerbating this learning crisis. As many as 94 percent of children across the world have been out of school due to closures. Learning losses from school shutdowns are further compounded by inequities , particularly for students who were already left behind by education systems. Many countries and schools have shifted to online learning during school closures as a stop-gap measure. However, this is not possible in many places, as less than half of households in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have internet access.

Many education systems around the world are now reopening fully, partially, or in a hybrid format, leaving millions of children to face a radically transformed educational experience. As COVID-19 cases rise and fall during the months ahead, the chaos will likely continue, with schools shutting down and reopening as needed to balance educational needs with protecting the health of students, teachers, and families. Parents, schools, and entire education systems—especially in LMICs—will need to play new roles to support student learning as the situation remains in flux, perhaps permanently. As they adjust to this new reality, research conducted by more than 220 professors affiliated with the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) and innovations from J-PAL's partners provide three insights into supporting immediate and long-term goals for educating children.

1. Support caregivers at home to help children learn while schools are closed . With nearly 1.6 billion children out of school at the peak of the pandemic, many parents or caregivers, especially with young children, have taken on new roles to help with at-home learning. To support them and remote education efforts, many LMICs have used SMS, phone calls, and other widely accessible, affordable, and low-technology methods of information delivery. While such methods are imperfect substitutes for schooling, research suggests they can help engage parents in their child’s education and contribute to learning , perhaps even after schools reopen.

Preliminary results from an ongoing program and randomized evaluation in Botswana show the promise of parental support combined with low-technology curriculum delivery. When the pandemic hit, the NGO Young 1ove was working with Botswana's Ministry of Education to scale up the Teaching at the Right Level approach to primary schools in multiple districts. After collecting student, parent, and teacher phone numbers, the NGO devised two strategies to deliver educational support. The first strategy sent SMS texts to households with a series of numeracy “problems of the week.” The second sent the same texts combined with 20-minute phone calls with Young 1ove staff members, who walked parents and students through the problems. Over four to five weeks, both interventions significantly improved learning . They halved the number of children who could not do basic mathematical operations like subtraction and division. Parents became more engaged with their children's education and had a better understanding of their learning levels. Young 1ove is now evaluating the impact of SMS texts and phone calls that are tailored to students’ numeracy levels.

In another example, the NGO Educate! reoriented its in-school youth skills model to be delivered through radio, SMS, and phone calls in response to school closures in East Africa. To encourage greater participation, Educate! called the students' caregivers to tell them about the program. Their internal analysis indicates that households that received such encouragement calls had a 29 percent increase in youth participation compared to those that did not receive the communication.

In several Latin American countries , researchers are evaluating the impact of sending SMS texts to parents on how to support their young children who have transitioned to distance-learning programs. Similar efforts to support parents and evaluate the effects are underway in Peru . Both will contribute to a better understanding of how to help caregivers support their child’s education using affordable and accessible technology.

Other governments and organizations in areas where internet access is limited are also experimenting with radio and TV to support parents and augment student learning. The Côte d’Ivoire government created a radio program on math and French for children in grades one to five. It involved hundreds of short lessons. The Indian NGO Pratham collaborated with the Bihar state government and a television channel to produce 10 hours of learning programming per week, creating more than 100 episodes to date. Past randomized evaluations of such “edutainment” programs from other sectors in Nigeria , Rwanda , and Uganda suggest the potential of delivering content and influencing behavior through mass media, though context is important, and more rigorous research is needed to understand the impact of such programs on learning.

2. As schools reopen, educators should use low-stakes assessments to identify learning gaps. As of September 1, schools in more than 75 countries were open to some degree. Many governments need to be prepared for the vast majority of children to be significantly behind in their educations as they return—a factor exacerbated by the low pre-pandemic learning levels, particularly in LMICs . Rather than jumping straight into grade-level curriculum, primary schools in LMICs should quickly assess learning levels to understand what children know (or don’t) and devise strategic responses. They can do so by using simple tools to frequently assess students, rather than focusing solely on high-stakes exams, which may significantly influence a child’s future by, for example, determining grade promotion.

Orally administered assessments—such as ASER , ICAN , and Uwezo —are simple, fast, inexpensive, and effective. The ASER math tool, for example, has just four elements: single-digit number recognition, double-digit number recognition, two-digit subtraction, and simple division. A similar tool exists for assessing foundational reading abilities. Tests like these don’t affect a child’s grades or promotion, help teachers to get frequent and clear views into learning levels, and can enable schools to devise plans to help children master the basics.

3. Tailor children's instruction to help them master foundational skills once learning gaps are identified. Given low learning levels before the pandemic and recent learning loss due to school disruptions, it is important to focus on basic skills as schools reopen to ensure children maintain and build a foundation for a lifetime of learning. Decades of research from Chile, India, Kenya, Ghana, and the United States shows that tailoring instruction to children’s’ education levels increases learning. For example, the Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) approach, pioneered by Indian NGO Pratham and evaluated in partnership with J-PAL researchers through six randomized evaluations over the last 20 years, focuses on foundational literacy and numeracy skills through interactive activities for a portion of the day rather than solely on the curriculum. It involves regular assessments of students' progress and is reaching more than 60 million children in India and several African countries .

Toward Universal Quality Education

As countries rebuild and reinvent themselves in response to COVID-19, there is an opportunity to accelerate the thinking on how to best support quality education for all. In the months and years ahead, coalitions of evidence-to-policy organizations, implementation partners, researchers, donors, and governments should build on their experiences to develop education-for-all strategies that use expansive research from J-PAL and similar organizations. In the long term, evidence-informed decisions and programs that account for country-specific conditions have the potential to improve pedagogy, support teachers, motivate students, improve school governance, and address many other aspects of the learning experience. Perhaps one positive outcome of the pandemic is that it will push us to overcome the many remaining global educational challenges sooner than any of us expect. We hope that we do.

Support SSIR ’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges. Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today .

Read more stories by Radhika Bhula & John Floretta .

SSIR.org and/or its third-party tools use cookies, which are necessary to its functioning and to our better understanding of user needs. By closing this banner, scrolling this page, clicking a link or continuing to otherwise browse this site, you agree to the use of cookies.

How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

Premedical programs: what to know.

Sarah Wood May 21, 2024

How Geography Affects College Admissions

Cole Claybourn May 21, 2024

Q&A: College Alumni Engagement

LaMont Jones, Jr. May 20, 2024

10 Destination West Coast College Towns

Cole Claybourn May 16, 2024

Scholarships for Lesser-Known Sports

Sarah Wood May 15, 2024

Should Students Submit Test Scores?

Sarah Wood May 13, 2024

Poll: Antisemitism a Problem on Campus

Lauren Camera May 13, 2024

Federal vs. Private Parent Student Loans

Erika Giovanetti May 9, 2024

14 Colleges With Great Food Options

Sarah Wood May 8, 2024

Colleges With Religious Affiliations

Anayat Durrani May 8, 2024

COVID-19 and education: The lingering effects of unfinished learning

As this most disrupted of school years draws to a close, it is time to take stock of the impact of the pandemic on student learning and well-being. Although the 2020–21 academic year ended on a high note—with rising vaccination rates, outdoor in-person graduations, and access to at least some in-person learning for 98 percent of students—it was as a whole perhaps one of the most challenging for educators and students in our nation’s history. 1 “Burbio’s K-12 school opening tracker,” Burbio, accessed May 31, 2021, cai.burbio.com. By the end of the school year, only 2 percent of students were in virtual-only districts. Many students, however, chose to keep learning virtually in districts that were offering hybrid or fully in-person learning.

Our analysis shows that the impact of the pandemic on K–12 student learning was significant, leaving students on average five months behind in mathematics and four months behind in reading by the end of the school year. The pandemic widened preexisting opportunity and achievement gaps, hitting historically disadvantaged students hardest. In math, students in majority Black schools ended the year with six months of unfinished learning, students in low-income schools with seven. High schoolers have become more likely to drop out of school, and high school seniors, especially those from low-income families, are less likely to go on to postsecondary education. And the crisis had an impact on not just academics but also the broader health and well-being of students, with more than 35 percent of parents very or extremely concerned about their children’s mental health.

The fallout from the pandemic threatens to depress this generation’s prospects and constrict their opportunities far into adulthood. The ripple effects may undermine their chances of attending college and ultimately finding a fulfilling job that enables them to support a family. Our analysis suggests that, unless steps are taken to address unfinished learning, today’s students may earn $49,000 to $61,000 less over their lifetime owing to the impact of the pandemic on their schooling. The impact on the US economy could amount to $128 billion to $188 billion every year as this cohort enters the workforce.

Federal funds are in place to help states and districts respond, though funding is only part of the answer. The deep-rooted challenges in our school systems predate the pandemic and have resisted many reform efforts. States and districts have a critical role to play in marshaling that funding into sustainable programs that improve student outcomes. They can ensure rigorous implementation of evidence-based initiatives, while also piloting and tracking the impact of innovative new approaches. Although it is too early to fully assess the effectiveness of postpandemic solutions to unfinished learning, the scope of action is already clear. The immediate imperative is to not only reopen schools and recover unfinished learning but also reimagine education systems for the long term. Across all of these priorities it will be critical to take a holistic approach, listening to students and parents and designing programs that meet academic and nonacademic needs alike.

What have we learned about unfinished learning?

As the 2020–21 school year began, just 40 percent of K–12 students were in districts that offered any in-person instruction. By the end of the year, more than 98 percent of students had access to some form of in-person learning, from the traditional five days a week to hybrid models. In the interim, districts oscillated among virtual, hybrid, and in-person learning as they balanced the need to keep students and staff safe with the need to provide an effective learning environment. Students faced multiple schedule changes, were assigned new teachers midyear, and struggled with glitchy internet connections and Zoom fatigue. This was a uniquely challenging year for teachers and students, and it is no surprise that it has left its mark—on student learning, and on student well-being.

As we analyze the cost of the pandemic, we use the term “unfinished learning” to capture the reality that students were not given the opportunity this year to complete all the learning they would have completed in a typical year. Some students who have disengaged from school altogether may have slipped backward, losing knowledge or skills they once had. The majority simply learned less than they would have in a typical year, but this is nonetheless important. Students who move on to the next grade unprepared are missing key building blocks of knowledge that are necessary for success, while students who repeat a year are much less likely to complete high school and move on to college. And it’s not just academic knowledge these students may miss out on. They are at risk of finishing school without the skills, behaviors, and mindsets to succeed in college or in the workforce. An accurate assessment of the depth and extent of unfinished learning will best enable districts and states to support students in catching up on the learning they missed and moving past the pandemic and into a successful future.

Students testing in 2021 were about ten points behind in math and nine points behind in reading, compared with matched students in previous years.

Unfinished learning is real—and inequitable

To assess student learning through the pandemic, we analyzed Curriculum Associates’ i-Ready in-school assessment results of more than 1.6 million elementary school students across more than 40 states. 2 The Curriculum Associates in-school sample consisted of 1.6 million K–6 students in mathematics and 1.5 million in reading. The math sample came from all 50 states, but 23 states accounted for 90 percent of the sample. The reading sample came from 46 states, with 21 states accounting for 90 percent of the sample. Florida accounted for 29 percent of the math and 30 percent of the reading sample. In general, states that had reopened schools are overweighted given the in-school nature of the assessment. We compared students’ performance in the spring of 2021 with the performance of similar students prior to the pandemic. 3 Specifically, we compared spring 2021 results to those of historically matched students in the springs of 2019, 2018, and 2017. Students testing in 2021 were about ten points behind in math and nine points behind in reading, compared with matched students in previous years.

To get a sense of the magnitude of these gaps, we translated these differences in scores to a more intuitive measure—months of learning. Although there is no perfect way to make this translation, we can get a sense of how far students are behind by comparing the levels students attained this spring with the growth in learning that usually occurs from one grade level to the next. We found that this cohort of students is five months behind in math and four months behind in reading, compared with where we would expect them to be based on historical data. 4 The conversion into months of learning compares students’ achievement in the spring of one grade level with their performance in the spring of the next grade level, treating this spring-to-spring difference in historical scores as a “year” of learning. It assumes a ten-month school year with a two-month summer vacation. Actual school schedules vary significantly, and i-Ready’s typical growth numbers for a “year” of learning are based on 30 weeks of actual instruction between the fall and the spring rather than on a spring-to-spring calendar-year comparison.

Unfinished learning did not vary significantly across elementary grades. Despite reports that remote learning was more challenging for early elementary students, 5 Marva Hinton, “Why teaching kindergarten online is so very, very hard,” Edutopia, October 21, 2020, edutopia.org. our results suggest the impact was just as meaningful for older elementary students. 6 While our analysis only includes results from students who tested in-school in the spring, many of these students were learning remotely for meaningful portions of the fall and the winter. We can hypothesize that perhaps younger elementary students received more help from parents and older siblings, and that older elementary students were more likely to be struggling alone.

It is also worth remembering that our numbers capture the “average” progress by grade level. Especially in early reading, this average can conceal a wide range of outcomes. Another way of cutting the data looks instead at which students have dropped further behind grade levels. A recent report suggests that more first and second graders have ended this year two or more grade levels below expectations than in any previous year. 7 Academic achievement at the end of the 2020–2021 school year , Curriculum Associates, June 2021, curriculumassociates.com. Given the major strides children at this age typically make in mastering reading, and the critical importance of early reading for later academic success, this is of particular concern.

While all types of students experienced unfinished learning, some groups were disproportionately affected. Students of color and low-income students suffered most. Students in majority-Black schools ended the school year six months behind in both math and reading, while students in majority-white schools ended up just four months behind in math and three months behind in reading. 8 To respect students’ privacy, we cannot isolate the race or income of individual students in our sample, but we can look at school-level demographics. Students in predominantly low-income schools and in urban locations also lost more learning during the pandemic than their peers in high-income rural and suburban schools (Exhibit 1).

In fall 2020, we projected that students could lose as much as five to ten months of learning in mathematics, and about half of that in reading, by the end of the school year. Spring assessment results came in toward the lower end of these projections, suggesting that districts and states were able to improve the quality of remote and hybrid learning through the 2020–21 school year and bring more students back into classrooms.

Indeed, if we look at the data over time, some interesting patterns emerge. 9 The composition of the fall student sample was different from that of the spring sample, because more students returned to in-person assessments in the spring. Some of the increase in unfinished learning from fall to spring could be because the spring assessment included previously virtual students, who may have struggled more during the school year. Even so, the spring data are the best reflection of unfinished learning at the end of the school year. Taking math as an example, as schools closed their buildings in the spring of 2020, students fell behind rapidly, learning almost no new math content over the final few months of the 2019–20 school year. Over the summer, we assume that they experienced the typical “summer slide” in which students lose some of the academic knowledge and skills they had learned the year before. Then they resumed learning through the 2020–21 school year, but at a slower pace than usual, resulting in five months of unfinished learning by the end of the year (Exhibit 2). 10 These lines simplify the pattern of typical learning through the year. In a typical year, students learn more in the fall and less in the spring, and only learn during periods of instruction (the chart includes the well-documented learning loss that happens during the summer, but does not include shorter holidays when students are not in school receiving instruction).

In reading, however, the story is somewhat different. As schools closed their buildings in March 2020, students continued to progress in reading, albeit at a slower pace. During the summer, we assume that students’ reading level stayed roughly flat, as in previous years. The pace of learning increased slightly over the 2020–21 school year, but the difference was not as great as it was in math, resulting in four months of unfinished learning by the end of the school year (Exhibit 3). Put another way, the initial shock in reading was less severe, but the improvements to remote and hybrid learning seem to have had less impact in reading than they did in math.