An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Lau F, Kuziemsky C, editors. Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet]. Victoria (BC): University of Victoria; 2017 Feb 27.

Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet].

Chapter 10 methods for comparative studies.

Francis Lau and Anne Holbrook .

10.1. Introduction

In eHealth evaluation, comparative studies aim to find out whether group differences in eHealth system adoption make a difference in important outcomes. These groups may differ in their composition, the type of system in use, and the setting where they work over a given time duration. The comparisons are to determine whether significant differences exist for some predefined measures between these groups, while controlling for as many of the conditions as possible such as the composition, system, setting and duration.

According to the typology by Friedman and Wyatt (2006) , comparative studies take on an objective view where events such as the use and effect of an eHealth system can be defined, measured and compared through a set of variables to prove or disprove a hypothesis. For comparative studies, the design options are experimental versus observational and prospective versus retrospective. The quality of eHealth comparative studies depends on such aspects of methodological design as the choice of variables, sample size, sources of bias, confounders, and adherence to quality and reporting guidelines.

In this chapter we focus on experimental studies as one type of comparative study and their methodological considerations that have been reported in the eHealth literature. Also included are three case examples to show how these studies are done.

10.2. Types of Comparative Studies

Experimental studies are one type of comparative study where a sample of participants is identified and assigned to different conditions for a given time duration, then compared for differences. An example is a hospital with two care units where one is assigned a cpoe system to process medication orders electronically while the other continues its usual practice without a cpoe . The participants in the unit assigned to the cpoe are called the intervention group and those assigned to usual practice are the control group. The comparison can be performance or outcome focused, such as the ratio of correct orders processed or the occurrence of adverse drug events in the two groups during the given time period. Experimental studies can take on a randomized or non-randomized design. These are described below.

10.2.1. Randomized Experiments

In a randomized design, the participants are randomly assigned to two or more groups using a known randomization technique such as a random number table. The design is prospective in nature since the groups are assigned concurrently, after which the intervention is applied then measured and compared. Three types of experimental designs seen in eHealth evaluation are described below ( Friedman & Wyatt, 2006 ; Zwarenstein & Treweek, 2009 ).

Randomized controlled trials ( rct s) – In rct s participants are randomly assigned to an intervention or a control group. The randomization can occur at the patient, provider or organization level, which is known as the unit of allocation. For instance, at the patient level one can randomly assign half of the patients to receive emr reminders while the other half do not. At the provider level, one can assign half of the providers to receive the reminders while the other half continues with their usual practice. At the organization level, such as a multisite hospital, one can randomly assign emr reminders to some of the sites but not others. Cluster randomized controlled trials ( crct s) – In crct s, clusters of participants are randomized rather than by individual participant since they are found in naturally occurring groups such as living in the same communities. For instance, clinics in one city may be randomized as a cluster to receive emr reminders while clinics in another city continue their usual practice. Pragmatic trials – Unlike rct s that seek to find out if an intervention such as a cpoe system works under ideal conditions, pragmatic trials are designed to find out if the intervention works under usual conditions. The goal is to make the design and findings relevant to and practical for decision-makers to apply in usual settings. As such, pragmatic trials have few criteria for selecting study participants, flexibility in implementing the intervention, usual practice as the comparator, the same compliance and follow-up intensity as usual practice, and outcomes that are relevant to decision-makers.

10.2.2. Non-randomized Experiments

Non-randomized design is used when it is neither feasible nor ethical to randomize participants into groups for comparison. It is sometimes referred to as a quasi-experimental design. The design can involve the use of prospective or retrospective data from the same or different participants as the control group. Three types of non-randomized designs are described below ( Harris et al., 2006 ).

Intervention group only with pretest and post-test design – This design involves only one group where a pretest or baseline measure is taken as the control period, the intervention is implemented, and a post-test measure is taken as the intervention period for comparison. For example, one can compare the rates of medication errors before and after the implementation of a cpoe system in a hospital. To increase study quality, one can add a second pretest period to decrease the probability that the pretest and post-test difference is due to chance, such as an unusually low medication error rate in the first pretest period. Other ways to increase study quality include adding an unrelated outcome such as patient case-mix that should not be affected, removing the intervention to see if the difference remains, and removing then re-implementing the intervention to see if the differences vary accordingly. Intervention and control groups with post-test design – This design involves two groups where the intervention is implemented in one group and compared with a second group without the intervention, based on a post-test measure from both groups. For example, one can implement a cpoe system in one care unit as the intervention group with a second unit as the control group and compare the post-test medication error rates in both units over six months. To increase study quality, one can add one or more pretest periods to both groups, or implement the intervention to the control group at a later time to measure for similar but delayed effects. Interrupted time series ( its ) design – In its design, multiple measures are taken from one group in equal time intervals, interrupted by the implementation of the intervention. The multiple pretest and post-test measures decrease the probability that the differences detected are due to chance or unrelated effects. An example is to take six consecutive monthly medication error rates as the pretest measures, implement the cpoe system, then take another six consecutive monthly medication error rates as the post-test measures for comparison in error rate differences over 12 months. To increase study quality, one may add a concurrent control group for comparison to be more convinced that the intervention produced the change.

10.3. Methodological Considerations

The quality of comparative studies is dependent on their internal and external validity. Internal validity refers to the extent to which conclusions can be drawn correctly from the study setting, participants, intervention, measures, analysis and interpretations. External validity refers to the extent to which the conclusions can be generalized to other settings. The major factors that influence validity are described below.

10.3.1. Choice of Variables

Variables are specific measurable features that can influence validity. In comparative studies, the choice of dependent and independent variables and whether they are categorical and/or continuous in values can affect the type of questions, study design and analysis to be considered. These are described below ( Friedman & Wyatt, 2006 ).

Dependent variables – This refers to outcomes of interest; they are also known as outcome variables. An example is the rate of medication errors as an outcome in determining whether cpoe can improve patient safety. Independent variables – This refers to variables that can explain the measured values of the dependent variables. For instance, the characteristics of the setting, participants and intervention can influence the effects of cpoe . Categorical variables – This refers to variables with measured values in discrete categories or levels. Examples are the type of providers (e.g., nurses, physicians and pharmacists), the presence or absence of a disease, and pain scale (e.g., 0 to 10 in increments of 1). Categorical variables are analyzed using non-parametric methods such as chi-square and odds ratio. Continuous variables – This refers to variables that can take on infinite values within an interval limited only by the desired precision. Examples are blood pressure, heart rate and body temperature. Continuous variables are analyzed using parametric methods such as t -test, analysis of variance or multiple regression.

10.3.2. Sample Size

Sample size is the number of participants to include in a study. It can refer to patients, providers or organizations depending on how the unit of allocation is defined. There are four parts to calculating sample size. They are described below ( Noordzij et al., 2010 ).

Significance level – This refers to the probability that a positive finding is due to chance alone. It is usually set at 0.05, which means having a less than 5% chance of drawing a false positive conclusion. Power – This refers to the ability to detect the true effect based on a sample from the population. It is usually set at 0.8, which means having at least an 80% chance of drawing a correct conclusion. Effect size – This refers to the minimal clinically relevant difference that can be detected between comparison groups. For continuous variables, the effect is a numerical value such as a 10-kilogram weight difference between two groups. For categorical variables, it is a percentage such as a 10% difference in medication error rates. Variability – This refers to the population variance of the outcome of interest, which is often unknown and is estimated by way of standard deviation ( sd ) from pilot or previous studies for continuous outcome.

Sample Size Equations for Comparing Two Groups with Continuous and Categorical Outcome Variables.

An example of sample size calculation for an rct to examine the effect of cds on improving systolic blood pressure of hypertensive patients is provided in the Appendix. Refer to the Biomath website from Columbia University (n.d.) for a simple Web-based sample size / power calculator.

10.3.3. Sources of Bias

There are five common sources of biases in comparative studies. They are selection, performance, detection, attrition and reporting biases ( Higgins & Green, 2011 ). These biases, and the ways to minimize them, are described below ( Vervloet et al., 2012 ).

Selection or allocation bias – This refers to differences between the composition of comparison groups in terms of the response to the intervention. An example is having sicker or older patients in the control group than those in the intervention group when evaluating the effect of emr reminders. To reduce selection bias, one can apply randomization and concealment when assigning participants to groups and ensure their compositions are comparable at baseline. Performance bias – This refers to differences between groups in the care they received, aside from the intervention being evaluated. An example is the different ways by which reminders are triggered and used within and across groups such as electronic, paper and phone reminders for patients and providers. To reduce performance bias, one may standardize the intervention and blind participants from knowing whether an intervention was received and which intervention was received. Detection or measurement bias – This refers to differences between groups in how outcomes are determined. An example is where outcome assessors pay more attention to outcomes of patients known to be in the intervention group. To reduce detection bias, one may blind assessors from participants when measuring outcomes and ensure the same timing for assessment across groups. Attrition bias – This refers to differences between groups in ways that participants are withdrawn from the study. An example is the low rate of participant response in the intervention group despite having received reminders for follow-up care. To reduce attrition bias, one needs to acknowledge the dropout rate and analyze data according to an intent-to-treat principle (i.e., include data from those who dropped out in the analysis). Reporting bias – This refers to differences between reported and unreported findings. Examples include biases in publication, time lag, citation, language and outcome reporting depending on the nature and direction of the results. To reduce reporting bias, one may make the study protocol available with all pre-specified outcomes and report all expected outcomes in published results.

10.3.4. Confounders

Confounders are factors other than the intervention of interest that can distort the effect because they are associated with both the intervention and the outcome. For instance, in a study to demonstrate whether the adoption of a medication order entry system led to lower medication costs, there can be a number of potential confounders that can affect the outcome. These may include severity of illness of the patients, provider knowledge and experience with the system, and hospital policy on prescribing medications ( Harris et al., 2006 ). Another example is the evaluation of the effect of an antibiotic reminder system on the rate of post-operative deep venous thromboses ( dvt s). The confounders can be general improvements in clinical practice during the study such as prescribing patterns and post-operative care that are not related to the reminders ( Friedman & Wyatt, 2006 ).

To control for confounding effects, one may consider the use of matching, stratification and modelling. Matching involves the selection of similar groups with respect to their composition and behaviours. Stratification involves the division of participants into subgroups by selected variables, such as comorbidity index to control for severity of illness. Modelling involves the use of statistical techniques such as multiple regression to adjust for the effects of specific variables such as age, sex and/or severity of illness ( Higgins & Green, 2011 ).

10.3.5. Guidelines on Quality and Reporting

There are guidelines on the quality and reporting of comparative studies. The grade (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) guidelines provide explicit criteria for rating the quality of studies in randomized trials and observational studies ( Guyatt et al., 2011 ). The extended consort (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) Statements for non-pharmacologic trials ( Boutron, Moher, Altman, Schulz, & Ravaud, 2008 ), pragmatic trials ( Zwarestein et al., 2008 ), and eHealth interventions ( Baker et al., 2010 ) provide reporting guidelines for randomized trials.

The grade guidelines offer a system of rating quality of evidence in systematic reviews and guidelines. In this approach, to support estimates of intervention effects rct s start as high-quality evidence and observational studies as low-quality evidence. For each outcome in a study, five factors may rate down the quality of evidence. The final quality of evidence for each outcome would fall into one of high, moderate, low, and very low quality. These factors are listed below (for more details on the rating system, refer to Guyatt et al., 2011 ).

Design limitations – For rct s they cover the lack of allocation concealment, lack of blinding, large loss to follow-up, trial stopped early or selective outcome reporting. Inconsistency of results – Variations in outcomes due to unexplained heterogeneity. An example is the unexpected variation of effects across subgroups of patients by severity of illness in the use of preventive care reminders. Indirectness of evidence – Reliance on indirect comparisons due to restrictions in study populations, intervention, comparator or outcomes. An example is the 30-day readmission rate as a surrogate outcome for quality of computer-supported emergency care in hospitals. Imprecision of results – Studies with small sample size and few events typically would have wide confidence intervals and are considered of low quality. Publication bias – The selective reporting of results at the individual study level is already covered under design limitations, but is included here for completeness as it is relevant when rating quality of evidence across studies in systematic reviews.

The original consort Statement has 22 checklist items for reporting rct s. For non-pharmacologic trials extensions have been made to 11 items. For pragmatic trials extensions have been made to eight items. These items are listed below. For further details, readers can refer to Boutron and colleagues (2008) and the consort website ( consort , n.d.).

Title and abstract – one item on the means of randomization used. Introduction – one item on background, rationale, and problem addressed by the intervention. Methods – 10 items on participants, interventions, objectives, outcomes, sample size, randomization (sequence generation, allocation concealment, implementation), blinding (masking), and statistical methods. Results – seven items on participant flow, recruitment, baseline data, numbers analyzed, outcomes and estimation, ancillary analyses, adverse events. Discussion – three items on interpretation, generalizability, overall evidence.

The consort Statement for eHealth interventions describes the relevance of the consort recommendations to the design and reporting of eHealth studies with an emphasis on Internet-based interventions for direct use by patients, such as online health information resources, decision aides and phr s. Of particular importance is the need to clearly define the intervention components, their role in the overall care process, target population, implementation process, primary and secondary outcomes, denominators for outcome analyses, and real world potential (for details refer to Baker et al., 2010 ).

10.4. Case Examples

10.4.1. pragmatic rct in vascular risk decision support.

Holbrook and colleagues (2011) conducted a pragmatic rct to examine the effects of a cds intervention on vascular care and outcomes for older adults. The study is summarized below.

Setting – Community-based primary care practices with emr s in one Canadian province. Participants – English-speaking patients 55 years of age or older with diagnosed vascular disease, no cognitive impairment and not living in a nursing home, who had a provider visit in the past 12 months. Intervention – A Web-based individualized vascular tracking and advice cds system for eight top vascular risk factors and two diabetic risk factors, for use by both providers and patients and their families. Providers and staff could update the patient’s profile at any time and the cds algorithm ran nightly to update recommendations and colour highlighting used in the tracker interface. Intervention patients had Web access to the tracker, a print version mailed to them prior to the visit, and telephone support on advice. Design – Pragmatic, one-year, two-arm, multicentre rct , with randomization upon patient consent by phone, using an allocation-concealed online program. Randomization was by patient with stratification by provider using a block size of six. Trained reviewers examined emr data and conducted patient telephone interviews to collect risk factors, vascular history, and vascular events. Providers completed questionnaires on the intervention at study end. Patients had final 12-month lab checks on urine albumin, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and A1c levels. Outcomes – Primary outcome was based on change in process composite score ( pcs ) computed as the sum of frequency-weighted process score for each of the eight main risk factors with a maximum score of 27. The process was considered met if a risk factor had been checked. pcs was measured at baseline and study end with the difference as the individual primary outcome scores. The main secondary outcome was a clinical composite score ( ccs ) based on the same eight risk factors compared in two ways: a comparison of the mean number of clinical variables on target and the percentage of patients with improvement between the two groups. Other secondary outcomes were actual vascular event rates, individual pcs and ccs components, ratings of usability, continuity of care, patient ability to manage vascular risk, and quality of life using the EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire ( eq-5D) . Analysis – 1,100 patients were needed to achieve 90% power in detecting a one-point pcs difference between groups with a standard deviation of five points, two-tailed t -test for mean difference at 5% significance level, and a withdrawal rate of 10%. The pcs , ccs and eq-5D scores were analyzed using a generalized estimating equation accounting for clustering within providers. Descriptive statistics and χ2 tests or exact tests were done with other outcomes. Findings – 1,102 patients and 49 providers enrolled in the study. The intervention group with 545 patients had significant pcs improvement with a difference of 4.70 ( p < .001) on a 27-point scale. The intervention group also had significantly higher odds of rating improvements in their continuity of care (4.178, p < .001) and ability to improve their vascular health (3.07, p < .001). There was no significant change in vascular events, clinical variables and quality of life. Overall the cds intervention led to reduced vascular risks but not to improved clinical outcomes in a one-year follow-up.

10.4.2. Non-randomized Experiment in Antibiotic Prescribing in Primary Care

Mainous, Lambourne, and Nietert (2013) conducted a prospective non-randomized trial to examine the impact of a cds system on antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections ( ari s) in primary care. The study is summarized below.

Setting – A primary care research network in the United States whose members use a common emr and pool data quarterly for quality improvement and research studies. Participants – An intervention group with nine practices across nine states, and a control group with 61 practices. Intervention – Point-of-care cds tool as customizable progress note templates based on existing emr features. cds recommendations reflect Centre for Disease Control and Prevention ( cdc ) guidelines based on a patient’s predominant presenting symptoms and age. cds was used to assist in ari diagnosis, prompt antibiotic use, record diagnosis and treatment decisions, and access printable patient and provider education resources from the cdc . Design – The intervention group received a multi-method intervention to facilitate provider cds adoption that included quarterly audit and feedback, best practice dissemination meetings, academic detailing site visits, performance review and cds training. The control group did not receive information on the intervention, the cds or education. Baseline data collection was for three months with follow-up of 15 months after cds implementation. Outcomes – The outcomes were frequency of inappropriate prescribing during an ari episode, broad-spectrum antibiotic use and diagnostic shift. Inappropriate prescribing was computed by dividing the number of ari episodes with diagnoses in the inappropriate category that had an antibiotic prescription by the total number of ari episodes with diagnosis for which antibiotics are inappropriate. Broad-spectrum antibiotic use was computed by all ari episodes with a broad-spectrum antibiotic prescription by the total number of ari episodes with an antibiotic prescription. Antibiotic drift was computed in two ways: dividing the number of ari episodes with diagnoses where antibiotics are appropriate by the total number of ari episodes with an antibiotic prescription; and dividing the number of ari episodes where antibiotics were inappropriate by the total number of ari episodes. Process measure included frequency of cds template use and whether the outcome measures differed by cds usage. Analysis – Outcomes were measured quarterly for each practice, weighted by the number of ari episodes during the quarter to assign greater weight to practices with greater numbers of relevant episodes and to periods with greater numbers of relevant episodes. Weighted means and 95% ci s were computed separately for adult and pediatric (less than 18 years of age) patients for each time period for both groups. Baseline means in outcome measures were compared between the two groups using weighted independent-sample t -tests. Linear mixed models were used to compare changes over the 18-month period. The models included time, intervention status, and were adjusted for practice characteristics such as specialty, size, region and baseline ari s. Random practice effects were included to account for clustering of repeated measures on practices over time. P -values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. Findings – For adult patients, inappropriate prescribing in ari episodes declined more among the intervention group (-0.6%) than the control group (4.2%)( p = 0.03), and prescribing of broad-spectrum antibiotics declined by 16.6% in the intervention group versus an increase of 1.1% in the control group ( p < 0.0001). For pediatric patients, there was a similar decline of 19.7% in the intervention group versus an increase of 0.9% in the control group ( p < 0.0001). In summary, the cds had a modest effect in reducing inappropriate prescribing for adults, but had a substantial effect in reducing the prescribing of broad-spectrum antibiotics in adult and pediatric patients.

10.4.3. Interrupted Time Series on EHR Impact in Nursing Care

Dowding, Turley, and Garrido (2012) conducted a prospective its study to examine the impact of ehr implementation on nursing care processes and outcomes. The study is summarized below.

Setting – Kaiser Permanente ( kp ) as a large not-for-profit integrated healthcare organization in the United States. Participants – 29 kp hospitals in the northern and southern regions of California. Intervention – An integrated ehr system implemented at all hospitals with cpoe , nursing documentation and risk assessment tools. The nursing component for risk assessment documentation of pressure ulcers and falls was consistent across hospitals and developed by clinical nurses and informaticists by consensus. Design – its design with monthly data on pressure ulcers and quarterly data on fall rates and risk collected over seven years between 2003 and 2009. All data were collected at the unit level for each hospital. Outcomes – Process measures were the proportion of patients with a fall risk assessment done and the proportion with a hospital-acquired pressure ulcer ( hapu ) risk assessment done within 24 hours of admission. Outcome measures were fall and hapu rates as part of the unit-level nursing care process and nursing sensitive outcome data collected routinely for all California hospitals. Fall rate was defined as the number of unplanned descents to the floor per 1,000 patient days, and hapu rate was the percentage of patients with stages i-IV or unstageable ulcer on the day of data collection. Analysis – Fall and hapu risk data were synchronized using the month in which the ehr was implemented at each hospital as time zero and aggregated across hospitals for each time period. Multivariate regression analysis was used to examine the effect of time, region and ehr . Findings – The ehr was associated with significant increase in document rates for hapu risk (2.21; 95% CI 0.67 to 3.75) and non-significant increase for fall risk (0.36; -3.58 to 4.30). The ehr was associated with 13% decrease in hapu rates (-0.76; -1.37 to -0.16) but no change in fall rates (-0.091; -0.29 to 011). Hospital region was a significant predictor of variation for hapu (0.72; 0.30 to 1.14) and fall rates (0.57; 0.41 to 0.72). During the study period, hapu rates decreased significantly (-0.16; -0.20 to -0.13) but not fall rates (0.0052; -0.01 to 0.02). In summary, ehr implementation was associated with a reduction in the number of hapu s but not patient falls, and changes over time and hospital region also affected outcomes.

10.5. Summary

In this chapter we introduced randomized and non-randomized experimental designs as two types of comparative studies used in eHealth evaluation. Randomization is the highest quality design as it reduces bias, but it is not always feasible. The methodological issues addressed include choice of variables, sample size, sources of biases, confounders, and adherence to reporting guidelines. Three case examples were included to show how eHealth comparative studies are done.

- Baker T. B., Gustafson D. H., Shaw B., Hawkins R., Pingree S., Roberts L., Strecher V. Relevance of consort reporting criteria for research on eHealth interventions. Patient Education and Counselling. 2010; 81 (suppl. 7):77–86. [ PMC free article : PMC2993846 ] [ PubMed : 20843621 ]

- Columbia University. (n.d.). Statistics: sample size / power calculation. Biomath (Division of Biomathematics/Biostatistics), Department of Pediatrics. New York: Columbia University Medical Centre. Retrieved from http://www .biomath.info/power/index.htm .

- Boutron I., Moher D., Altman D. G., Schulz K. F., Ravaud P. consort Group. Extending the consort statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: Explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008; 148 (4):295–309. [ PubMed : 18283207 ]

- Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane handbook. London: Author; (n.d.) Retrieved from http://handbook .cochrane.org/

- consort Group. (n.d.). The consort statement . Retrieved from http://www .consort-statement.org/

- Dowding D. W., Turley M., Garrido T. The impact of an electronic health record on nurse sensitive patient outcomes: an interrupted time series analysis. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2012; 19 (4):615–620. [ PMC free article : PMC3384108 ] [ PubMed : 22174327 ]

- Friedman C. P., Wyatt J.C. Evaluation methods in biomedical informatics. 2nd ed. New York: Springer Science + Business Media, Inc; 2006.

- Guyatt G., Oxman A. D., Akl E. A., Kunz R., Vist G., Brozek J. et al. Schunemann H. J. grade guidelines: 1. Introduction – grade evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2011; 64 (4):383–394. [ PubMed : 21195583 ]

- Harris A. D., McGregor J. C., Perencevich E. N., Furuno J. P., Zhu J., Peterson D. E., Finkelstein J. The use and interpretation of quasi-experimental studies in medical informatics. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2006; 13 (1):16–23. [ PMC free article : PMC1380192 ] [ PubMed : 16221933 ]

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Higgins J. P. T., Green S., editors. London: 2011. (Version 5.1.0, updated March 2011) Retrieved from http://handbook .cochrane.org/

- Holbrook A., Pullenayegum E., Thabane L., Troyan S., Foster G., Keshavjee K. et al. Curnew G. Shared electronic vascular risk decision support in primary care. Computerization of medical practices for the enhancement of therapeutic effectiveness (compete III) randomized trial. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011; 171 (19):1736–1744. [ PubMed : 22025430 ]

- Mainous III A. G., Lambourne C. A., Nietert P.J. Impact of a clinical decision support system on antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections in primary care: quasi-experimental trial. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2013; 20 (2):317–324. [ PMC free article : PMC3638170 ] [ PubMed : 22759620 ]

- Noordzij M., Tripepi G., Dekker F. W., Zoccali C., Tanck M. W., Jager K.J. Sample size calculations: basic principles and common pitfalls. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2010; 25 (5):1388–1393. Retrieved from http://ndt .oxfordjournals .org/content/early/2010/01/12/ndt .gfp732.short . [ PubMed : 20067907 ]

- Vervloet M., Linn A. J., van Weert J. C. M., de Bakker D. H., Bouvy M. L., van Dijk L. The effectiveness of interventions using electronic reminders to improve adherence to chronic medication: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2012; 19 (5):696–704. [ PMC free article : PMC3422829 ] [ PubMed : 22534082 ]

- Zwarenstein M., Treweek S., Gagnier J. J., Altman D. G., Tunis S., Haynes B., Oxman A. D., Moher D. for the consort and Pragmatic Trials in Healthcare (Practihc) groups. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the consort statement. British Medical Journal. 2008; 337 :a2390. [ PMC free article : PMC3266844 ] [ PubMed : 19001484 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zwarenstein M., Treweek S. What kind of randomized trials do we need? Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2009; 180 (10):998–1000. [ PMC free article : PMC2679816 ] [ PubMed : 19372438 ]

Appendix. Example of Sample Size Calculation

This is an example of sample size calculation for an rct that examines the effect of a cds system on reducing systolic blood pressure in hypertensive patients. The case is adapted from the example described in the publication by Noordzij et al. (2010) .

(a) Systolic blood pressure as a continuous outcome measured in mmHg

Based on similar studies in the literature with similar patients, the systolic blood pressure values from the comparison groups are expected to be normally distributed with a standard deviation of 20 mmHg. The evaluator wishes to detect a clinically relevant difference of 15 mmHg in systolic blood pressure as an outcome between the intervention group with cds and the control group without cds . Assuming a significance level or alpha of 0.05 for 2-tailed t -test and power of 0.80, the corresponding multipliers 1 are 1.96 and 0.842, respectively. Using the sample size equation for continuous outcome below we can calculate the sample size needed for the above study.

n = 2[(a+b)2σ2]/(μ1-μ2)2 where

n = sample size for each group

μ1 = population mean of systolic blood pressures in intervention group

μ2 = population mean of systolic blood pressures in control group

μ1- μ2 = desired difference in mean systolic blood pressures between groups

σ = population variance

a = multiplier for significance level (or alpha)

b = multiplier for power (or 1-beta)

Providing the values in the equation would give the sample size (n) of 28 samples per group as the result

n = 2[(1.96+0.842)2(202)]/152 or 28 samples per group

(b) Systolic blood pressure as a categorical outcome measured as below or above 140 mmHg (i.e., hypertension yes/no)

In this example a systolic blood pressure from a sample that is above 140 mmHg is considered an event of the patient with hypertension. Based on published literature the proportion of patients in the general population with hypertension is 30%. The evaluator wishes to detect a clinically relevant difference of 10% in systolic blood pressure as an outcome between the intervention group with cds and the control group without cds . This means the expected proportion of patients with hypertension is 20% (p1 = 0.2) in the intervention group and 30% (p2 = 0.3) in the control group. Assuming a significance level or alpha of 0.05 for 2-tailed t -test and power of 0.80 the corresponding multipliers are 1.96 and 0.842, respectively. Using the sample size equation for categorical outcome below, we can calculate the sample size needed for the above study.

n = [(a+b)2(p1q1+p2q2)]/χ2

p1 = proportion of patients with hypertension in intervention group

q1 = proportion of patients without hypertension in intervention group (or 1-p1)

p2 = proportion of patients with hypertension in control group

q2 = proportion of patients without hypertension in control group (or 1-p2)

χ = desired difference in proportion of hypertensive patients between two groups

Providing the values in the equation would give the sample size (n) of 291 samples per group as the result

n = [(1.96+0.842)2((0.2)(0.8)+(0.3)(0.7))]/(0.1)2 or 291 samples per group

From Table 3 on p. 1392 of Noordzij et al. (2010).

This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons License, Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0): see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

- Cite this Page Lau F, Holbrook A. Chapter 10 Methods for Comparative Studies. In: Lau F, Kuziemsky C, editors. Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet]. Victoria (BC): University of Victoria; 2017 Feb 27.

- PDF version of this title (4.5M)

- Disable Glossary Links

In this Page

- Introduction

- Types of Comparative Studies

- Methodological Considerations

- Case Examples

- Example of Sample Size Calculation

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Recent Activity

- Chapter 10 Methods for Comparative Studies - Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An ... Chapter 10 Methods for Comparative Studies - Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

Gen ed writes, writing across the disciplines at harvard college.

- Comparative Analysis

What It Is and Why It's Useful

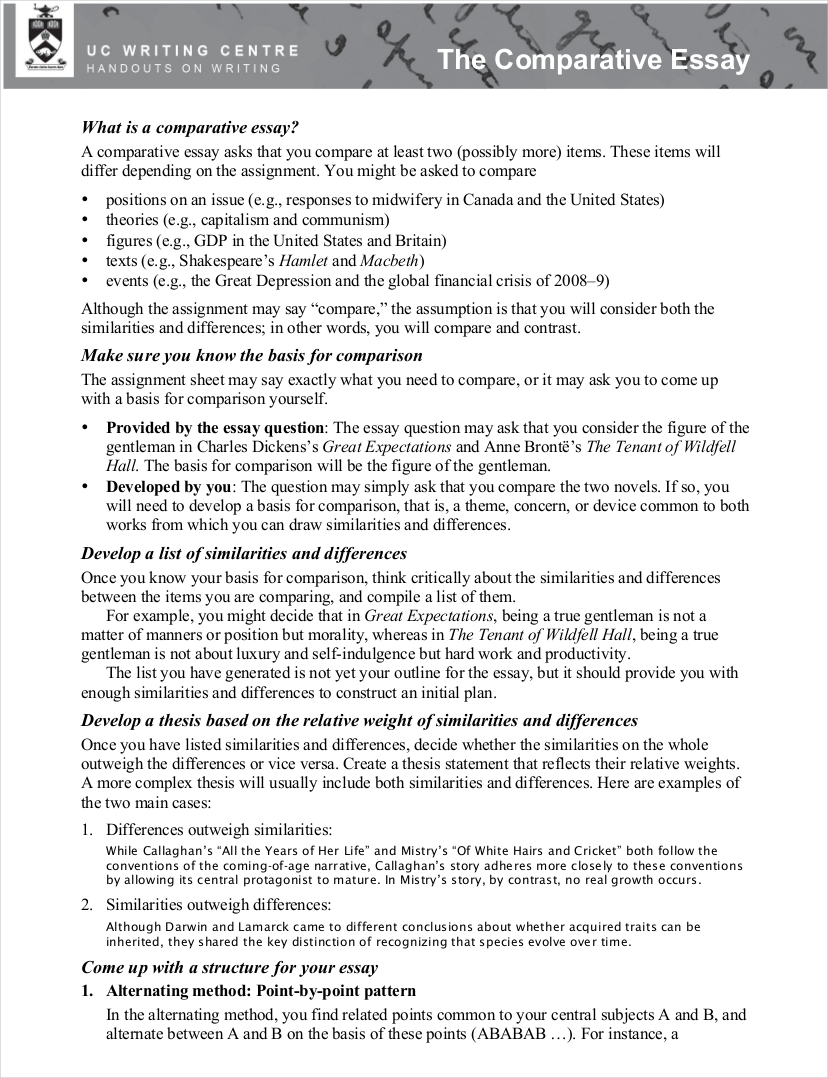

Comparative analysis asks writers to make an argument about the relationship between two or more texts. Beyond that, there's a lot of variation, but three overarching kinds of comparative analysis stand out:

- Coordinate (A ↔ B): In this kind of analysis, two (or more) texts are being read against each other in terms of a shared element, e.g., a memoir and a novel, both by Jesmyn Ward; two sets of data for the same experiment; a few op-ed responses to the same event; two YA books written in Chicago in the 2000s; a film adaption of a play; etc.

- Subordinate (A → B) or (B → A ): Using a theoretical text (as a "lens") to explain a case study or work of art (e.g., how Anthony Jack's The Privileged Poor can help explain divergent experiences among students at elite four-year private colleges who are coming from similar socio-economic backgrounds) or using a work of art or case study (i.e., as a "test" of) a theory's usefulness or limitations (e.g., using coverage of recent incidents of gun violence or legislation un the U.S. to confirm or question the currency of Carol Anderson's The Second ).

- Hybrid [A → (B ↔ C)] or [(B ↔ C) → A] , i.e., using coordinate and subordinate analysis together. For example, using Jack to compare or contrast the experiences of students at elite four-year institutions with students at state universities and/or community colleges; or looking at gun culture in other countries and/or other timeframes to contextualize or generalize Anderson's main points about the role of the Second Amendment in U.S. history.

"In the wild," these three kinds of comparative analysis represent increasingly complex—and scholarly—modes of comparison. Students can of course compare two poems in terms of imagery or two data sets in terms of methods, but in each case the analysis will eventually be richer if the students have had a chance to encounter other people's ideas about how imagery or methods work. At that point, we're getting into a hybrid kind of reading (or even into research essays), especially if we start introducing different approaches to imagery or methods that are themselves being compared along with a couple (or few) poems or data sets.

Why It's Useful

In the context of a particular course, each kind of comparative analysis has its place and can be a useful step up from single-source analysis. Intellectually, comparative analysis helps overcome the "n of 1" problem that can face single-source analysis. That is, a writer drawing broad conclusions about the influence of the Iranian New Wave based on one film is relying entirely—and almost certainly too much—on that film to support those findings. In the context of even just one more film, though, the analysis is suddenly more likely to arrive at one of the best features of any comparative approach: both films will be more richly experienced than they would have been in isolation, and the themes or questions in terms of which they're being explored (here the general question of the influence of the Iranian New Wave) will arrive at conclusions that are less at-risk of oversimplification.

For scholars working in comparative fields or through comparative approaches, these features of comparative analysis animate their work. To borrow from a stock example in Western epistemology, our concept of "green" isn't based on a single encounter with something we intuit or are told is "green." Not at all. Our concept of "green" is derived from a complex set of experiences of what others say is green or what's labeled green or what seems to be something that's neither blue nor yellow but kind of both, etc. Comparative analysis essays offer us the chance to engage with that process—even if only enough to help us see where a more in-depth exploration with a higher and/or more diverse "n" might lead—and in that sense, from the standpoint of the subject matter students are exploring through writing as well the complexity of the genre of writing they're using to explore it—comparative analysis forms a bridge of sorts between single-source analysis and research essays.

Typical learning objectives for single-sources essays: formulate analytical questions and an arguable thesis, establish stakes of an argument, summarize sources accurately, choose evidence effectively, analyze evidence effectively, define key terms, organize argument logically, acknowledge and respond to counterargument, cite sources properly, and present ideas in clear prose.

Common types of comparative analysis essays and related types: two works in the same genre, two works from the same period (but in different places or in different cultures), a work adapted into a different genre or medium, two theories treating the same topic; a theory and a case study or other object, etc.

How to Teach It: Framing + Practice

Framing multi-source writing assignments (comparative analysis, research essays, multi-modal projects) is likely to overlap a great deal with "Why It's Useful" (see above), because the range of reasons why we might use these kinds of writing in academic or non-academic settings is itself the reason why they so often appear later in courses. In many courses, they're the best vehicles for exploring the complex questions that arise once we've been introduced to the course's main themes, core content, leading protagonists, and central debates.

For comparative analysis in particular, it's helpful to frame assignment's process and how it will help students successfully navigate the challenges and pitfalls presented by the genre. Ideally, this will mean students have time to identify what each text seems to be doing, take note of apparent points of connection between different texts, and start to imagine how those points of connection (or the absence thereof)

- complicates or upends their own expectations or assumptions about the texts

- complicates or refutes the expectations or assumptions about the texts presented by a scholar

- confirms and/or nuances expectations and assumptions they themselves hold or scholars have presented

- presents entirely unforeseen ways of understanding the texts

—and all with implications for the texts themselves or for the axes along which the comparative analysis took place. If students know that this is where their ideas will be heading, they'll be ready to develop those ideas and engage with the challenges that comparative analysis presents in terms of structure (See "Tips" and "Common Pitfalls" below for more on these elements of framing).

Like single-source analyses, comparative essays have several moving parts, and giving students practice here means adapting the sample sequence laid out at the " Formative Writing Assignments " page. Three areas that have already been mentioned above are worth noting:

- Gathering evidence : Depending on what your assignment is asking students to compare (or in terms of what), students will benefit greatly from structured opportunities to create inventories or data sets of the motifs, examples, trajectories, etc., shared (or not shared) by the texts they'll be comparing. See the sample exercises below for a basic example of what this might look like.

- Why it Matters: Moving beyond "x is like y but also different" or even "x is more like y than we might think at first" is what moves an essay from being "compare/contrast" to being a comparative analysis . It's also a move that can be hard to make and that will often evolve over the course of an assignment. A great way to get feedback from students about where they're at on this front? Ask them to start considering early on why their argument "matters" to different kinds of imagined audiences (while they're just gathering evidence) and again as they develop their thesis and again as they're drafting their essays. ( Cover letters , for example, are a great place to ask writers to imagine how a reader might be affected by reading an their argument.)

- Structure: Having two texts on stage at the same time can suddenly feel a lot more complicated for any writer who's used to having just one at a time. Giving students a sense of what the most common patterns (AAA / BBB, ABABAB, etc.) are likely to be can help them imagine, even if provisionally, how their argument might unfold over a series of pages. See "Tips" and "Common Pitfalls" below for more information on this front.

Sample Exercises and Links to Other Resources

- Common Pitfalls

- Advice on Timing

- Try to keep students from thinking of a proposed thesis as a commitment. Instead, help them see it as more of a hypothesis that has emerged out of readings and discussion and analytical questions and that they'll now test through an experiment, namely, writing their essay. When students see writing as part of the process of inquiry—rather than just the result—and when that process is committed to acknowledging and adapting itself to evidence, it makes writing assignments more scientific, more ethical, and more authentic.

- Have students create an inventory of touch points between the two texts early in the process.

- Ask students to make the case—early on and at points throughout the process—for the significance of the claim they're making about the relationship between the texts they're comparing.

- For coordinate kinds of comparative analysis, a common pitfall is tied to thesis and evidence. Basically, it's a thesis that tells the reader that there are "similarities and differences" between two texts, without telling the reader why it matters that these two texts have or don't have these particular features in common. This kind of thesis is stuck at the level of description or positivism, and it's not uncommon when a writer is grappling with the complexity that can in fact accompany the "taking inventory" stage of comparative analysis. The solution is to make the "taking inventory" stage part of the process of the assignment. When this stage comes before students have formulated a thesis, that formulation is then able to emerge out of a comparative data set, rather than the data set emerging in terms of their thesis (which can lead to confirmation bias, or frequency illusion, or—just for the sake of streamlining the process of gathering evidence—cherry picking).

- For subordinate kinds of comparative analysis , a common pitfall is tied to how much weight is given to each source. Having students apply a theory (in a "lens" essay) or weigh the pros and cons of a theory against case studies (in a "test a theory") essay can be a great way to help them explore the assumptions, implications, and real-world usefulness of theoretical approaches. The pitfall of these approaches is that they can quickly lead to the same biases we saw here above. Making sure that students know they should engage with counterevidence and counterargument, and that "lens" / "test a theory" approaches often balance each other out in any real-world application of theory is a good way to get out in front of this pitfall.

- For any kind of comparative analysis, a common pitfall is structure. Every comparative analysis asks writers to move back and forth between texts, and that can pose a number of challenges, including: what pattern the back and forth should follow and how to use transitions and other signposting to make sure readers can follow the overarching argument as the back and forth is taking place. Here's some advice from an experienced writing instructor to students about how to think about these considerations:

a quick note on STRUCTURE

Most of us have encountered the question of whether to adopt what we might term the “A→A→A→B→B→B” structure or the “A→B→A→B→A→B” structure. Do we make all of our points about text A before moving on to text B? Or do we go back and forth between A and B as the essay proceeds? As always, the answers to our questions about structure depend on our goals in the essay as a whole. In a “similarities in spite of differences” essay, for instance, readers will need to encounter the differences between A and B before we offer them the similarities (A d →B d →A s →B s ). If, rather than subordinating differences to similarities you are subordinating text A to text B (using A as a point of comparison that reveals B’s originality, say), you may be well served by the “A→A→A→B→B→B” structure.

Ultimately, you need to ask yourself how many “A→B” moves you have in you. Is each one identical? If so, you may wish to make the transition from A to B only once (“A→A→A→B→B→B”), because if each “A→B” move is identical, the “A→B→A→B→A→B” structure will appear to involve nothing more than directionless oscillation and repetition. If each is increasingly complex, however—if each AB pair yields a new and progressively more complex idea about your subject—you may be well served by the “A→B→A→B→A→B” structure, because in this case it will be visible to readers as a progressively developing argument.

As we discussed in "Advice on Timing" at the page on single-source analysis, that timeline itself roughly follows the "Sample Sequence of Formative Assignments for a 'Typical' Essay" outlined under " Formative Writing Assignments, " and it spans about 5–6 steps or 2–4 weeks.

Comparative analysis assignments have a lot of the same DNA as single-source essays, but they potentially bring more reading into play and ask students to engage in more complicated acts of analysis and synthesis during the drafting stages. With that in mind, closer to 4 weeks is probably a good baseline for many single-source analysis assignments. For sections that meet once per week, the timeline will either probably need to expand—ideally—a little past the 4-week side of things, or some of the steps will need to be combined or done asynchronously.

What It Can Build Up To

Comparative analyses can build up to other kinds of writing in a number of ways. For example:

- They can build toward other kinds of comparative analysis, e.g., student can be asked to choose an additional source to complicate their conclusions from a previous analysis, or they can be asked to revisit an analysis using a different axis of comparison, such as race instead of class. (These approaches are akin to moving from a coordinate or subordinate analysis to more of a hybrid approach.)

- They can scaffold up to research essays, which in many instances are an extension of a "hybrid comparative analysis."

- Like single-source analysis, in a course where students will take a "deep dive" into a source or topic for their capstone, they can allow students to "try on" a theoretical approach or genre or time period to see if it's indeed something they want to research more fully.

- DIY Guides for Analytical Writing Assignments

- Types of Assignments

- Unpacking the Elements of Writing Prompts

- Formative Writing Assignments

- Single-Source Analysis

- Research Essays

- Multi-Modal or Creative Projects

- Giving Feedback to Students

Assignment Decoder

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing a Paper: Comparing & Contrasting

A compare and contrast paper discusses the similarities and differences between two or more topics. The paper should contain an introduction with a thesis statement, a body where the comparisons and contrasts are discussed, and a conclusion.

Address Both Similarities and Differences

Because this is a compare and contrast paper, both the similarities and differences should be discussed. This will require analysis on your part, as some topics will appear to be quite similar, and you will have to work to find the differing elements.

Make Sure You Have a Clear Thesis Statement

Just like any other essay, a compare and contrast essay needs a thesis statement. The thesis statement should not only tell your reader what you will do, but it should also address the purpose and importance of comparing and contrasting the material.

Use Clear Transitions

Transitions are important in compare and contrast essays, where you will be moving frequently between different topics or perspectives.

- Examples of transitions and phrases for comparisons: as well, similar to, consistent with, likewise, too

- Examples of transitions and phrases for contrasts: on the other hand, however, although, differs, conversely, rather than.

For more information, check out our transitions page.

Structure Your Paper

Consider how you will present the information. You could present all of the similarities first and then present all of the differences. Or you could go point by point and show the similarity and difference of one point, then the similarity and difference for another point, and so on.

Include Analysis

It is tempting to just provide summary for this type of paper, but analysis will show the importance of the comparisons and contrasts. For instance, if you are comparing two articles on the topic of the nursing shortage, help us understand what this will achieve. Did you find consensus between the articles that will support a certain action step for people in the field? Did you find discrepancies between the two that point to the need for further investigation?

Make Analogous Comparisons

When drawing comparisons or making contrasts, be sure you are dealing with similar aspects of each item. To use an old cliché, are you comparing apples to apples?

- Example of poor comparisons: Kubista studied the effects of a later start time on high school students, but Cook used a mixed methods approach. (This example does not compare similar items. It is not a clear contrast because the sentence does not discuss the same element of the articles. It is like comparing apples to oranges.)

- Example of analogous comparisons: Cook used a mixed methods approach, whereas Kubista used only quantitative methods. (Here, methods are clearly being compared, allowing the reader to understand the distinction.

Related Webinar

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Developing Arguments

- Next Page: Avoiding Logical Fallacies

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

What is comparative analysis? A complete guide

Last updated

18 April 2023

Reviewed by

Jean Kaluza

Comparative analysis is a valuable tool for acquiring deep insights into your organization’s processes, products, and services so you can continuously improve them.

Similarly, if you want to streamline, price appropriately, and ultimately be a market leader, you’ll likely need to draw on comparative analyses quite often.

When faced with multiple options or solutions to a given problem, a thorough comparative analysis can help you compare and contrast your options and make a clear, informed decision.

If you want to get up to speed on conducting a comparative analysis or need a refresher, here’s your guide.

Make comparative analysis less tedious

Dovetail streamlines comparative analysis to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- What exactly is comparative analysis?

A comparative analysis is a side-by-side comparison that systematically compares two or more things to pinpoint their similarities and differences. The focus of the investigation might be conceptual—a particular problem, idea, or theory—or perhaps something more tangible, like two different data sets.

For instance, you could use comparative analysis to investigate how your product features measure up to the competition.

After a successful comparative analysis, you should be able to identify strengths and weaknesses and clearly understand which product is more effective.

You could also use comparative analysis to examine different methods of producing that product and determine which way is most efficient and profitable.

The potential applications for using comparative analysis in everyday business are almost unlimited. That said, a comparative analysis is most commonly used to examine

Emerging trends and opportunities (new technologies, marketing)

Competitor strategies

Financial health

Effects of trends on a target audience

- Why is comparative analysis so important?

Comparative analysis can help narrow your focus so your business pursues the most meaningful opportunities rather than attempting dozens of improvements simultaneously.

A comparative approach also helps frame up data to illuminate interrelationships. For example, comparative research might reveal nuanced relationships or critical contexts behind specific processes or dependencies that wouldn’t be well-understood without the research.

For instance, if your business compares the cost of producing several existing products relative to which ones have historically sold well, that should provide helpful information once you’re ready to look at developing new products or features.

- Comparative vs. competitive analysis—what’s the difference?

Comparative analysis is generally divided into three subtypes, using quantitative or qualitative data and then extending the findings to a larger group. These include

Pattern analysis —identifying patterns or recurrences of trends and behavior across large data sets.

Data filtering —analyzing large data sets to extract an underlying subset of information. It may involve rearranging, excluding, and apportioning comparative data to fit different criteria.

Decision tree —flowcharting to visually map and assess potential outcomes, costs, and consequences.

In contrast, competitive analysis is a type of comparative analysis in which you deeply research one or more of your industry competitors. In this case, you’re using qualitative research to explore what the competition is up to across one or more dimensions.

For example

Service delivery —metrics like the Net Promoter Scores indicate customer satisfaction levels.

Market position — the share of the market that the competition has captured.

Brand reputation —how well-known or recognized your competitors are within their target market.

- Tips for optimizing your comparative analysis

Conduct original research

Thorough, independent research is a significant asset when doing comparative analysis. It provides evidence to support your findings and may present a perspective or angle not considered previously.

Make analysis routine

To get the maximum benefit from comparative research, make it a regular practice, and establish a cadence you can realistically stick to. Some business areas you could plan to analyze regularly include:

Profitability

Competition

Experiment with controlled and uncontrolled variables

In addition to simply comparing and contrasting, explore how different variables might affect your outcomes.

For example, a controllable variable would be offering a seasonal feature like a shopping bot to assist in holiday shopping or raising or lowering the selling price of a product.

Uncontrollable variables include weather, changing regulations, the current political climate, or global pandemics.

Put equal effort into each point of comparison

Most people enter into comparative research with a particular idea or hypothesis already in mind to validate. For instance, you might try to prove the worthwhileness of launching a new service. So, you may be disappointed if your analysis results don’t support your plan.

However, in any comparative analysis, try to maintain an unbiased approach by spending equal time debating the merits and drawbacks of any decision. Ultimately, this will be a practical, more long-term sustainable approach for your business than focusing only on the evidence that favors pursuing your argument or strategy.

Writing a comparative analysis in five steps

To put together a coherent, insightful analysis that goes beyond a list of pros and cons or similarities and differences, try organizing the information into these five components:

1. Frame of reference

Here is where you provide context. First, what driving idea or problem is your research anchored in? Then, for added substance, cite existing research or insights from a subject matter expert, such as a thought leader in marketing, startup growth, or investment

2. Grounds for comparison Why have you chosen to examine the two things you’re analyzing instead of focusing on two entirely different things? What are you hoping to accomplish?

3. Thesis What argument or choice are you advocating for? What will be the before and after effects of going with either decision? What do you anticipate happening with and without this approach?

For example, “If we release an AI feature for our shopping cart, we will have an edge over the rest of the market before the holiday season.” The finished comparative analysis will weigh all the pros and cons of choosing to build the new expensive AI feature including variables like how “intelligent” it will be, what it “pushes” customers to use, how much it takes off the plates of customer service etc.

Ultimately, you will gauge whether building an AI feature is the right plan for your e-commerce shop.

4. Organize the scheme Typically, there are two ways to organize a comparative analysis report. First, you can discuss everything about comparison point “A” and then go into everything about aspect “B.” Or, you alternate back and forth between points “A” and “B,” sometimes referred to as point-by-point analysis.

Using the AI feature as an example again, you could cover all the pros and cons of building the AI feature, then discuss the benefits and drawbacks of building and maintaining the feature. Or you could compare and contrast each aspect of the AI feature, one at a time. For example, a side-by-side comparison of the AI feature to shopping without it, then proceeding to another point of differentiation.

5. Connect the dots Tie it all together in a way that either confirms or disproves your hypothesis.

For instance, “Building the AI bot would allow our customer service team to save 12% on returns in Q3 while offering optimizations and savings in future strategies. However, it would also increase the product development budget by 43% in both Q1 and Q2. Our budget for product development won’t increase again until series 3 of funding is reached, so despite its potential, we will hold off building the bot until funding is secured and more opportunities and benefits can be proved effective.”

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 12 May 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 18 May 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

How to Do Comparative Analysis in Research ( Examples )

Comparative analysis is a method that is widely used in social science . It is a method of comparing two or more items with an idea of uncovering and discovering new ideas about them. It often compares and contrasts social structures and processes around the world to grasp general patterns. Comparative analysis tries to understand the study and explain every element of data that comparing.

We often compare and contrast in our daily life. So it is usual to compare and contrast the culture and human society. We often heard that ‘our culture is quite good than theirs’ or ‘their lifestyle is better than us’. In social science, the social scientist compares primitive, barbarian, civilized, and modern societies. They use this to understand and discover the evolutionary changes that happen to society and its people. It is not only used to understand the evolutionary processes but also to identify the differences, changes, and connections between societies.

Most social scientists are involved in comparative analysis. Macfarlane has thought that “On account of history, the examinations are typically on schedule, in that of other sociologies, transcendently in space. The historian always takes their society and compares it with the past society, and analyzes how far they differ from each other.

The comparative method of social research is a product of 19 th -century sociology and social anthropology. Sociologists like Emile Durkheim, Herbert Spencer Max Weber used comparative analysis in their works. For example, Max Weber compares the protestant of Europe with Catholics and also compared it with other religions like Islam, Hinduism, and Confucianism.

To do a systematic comparison we need to follow different elements of the method.

1. Methods of comparison The comparison method

In social science, we can do comparisons in different ways. It is merely different based on the topic, the field of study. Like Emile Durkheim compare societies as organic solidarity and mechanical solidarity. The famous sociologist Emile Durkheim provides us with three different approaches to the comparative method. Which are;

- The first approach is to identify and select one particular society in a fixed period. And by doing that, we can identify and determine the relationship, connections and differences exist in that particular society alone. We can find their religious practices, traditions, law, norms etc.

- The second approach is to consider and draw various societies which have common or similar characteristics that may vary in some ways. It may be we can select societies at a specific period, or we can select societies in the different periods which have common characteristics but vary in some ways. For example, we can take European and American societies (which are universally similar characteristics) in the 20 th century. And we can compare and contrast their society in terms of law, custom, tradition, etc.

- The third approach he envisaged is to take different societies of different times that may share some similar characteristics or maybe show revolutionary changes. For example, we can compare modern and primitive societies which show us revolutionary social changes.

2 . The unit of comparison

We cannot compare every aspect of society. As we know there are so many things that we cannot compare. The very success of the compare method is the unit or the element that we select to compare. We are only able to compare things that have some attributes in common. For example, we can compare the existing family system in America with the existing family system in Europe. But we are not able to compare the food habits in china with the divorce rate in America. It is not possible. So, the next thing you to remember is to consider the unit of comparison. You have to select it with utmost care.

3. The motive of comparison

As another method of study, a comparative analysis is one among them for the social scientist. The researcher or the person who does the comparative method must know for what grounds they taking the comparative method. They have to consider the strength, limitations, weaknesses, etc. He must have to know how to do the analysis.

Steps of the comparative method

1. Setting up of a unit of comparison

As mentioned earlier, the first step is to consider and determine the unit of comparison for your study. You must consider all the dimensions of your unit. This is where you put the two things you need to compare and to properly analyze and compare it. It is not an easy step, we have to systematically and scientifically do this with proper methods and techniques. You have to build your objectives, variables and make some assumptions or ask yourself about what you need to study or make a hypothesis for your analysis.

The best casings of reference are built from explicit sources instead of your musings or perceptions. To do that you can select some attributes in the society like marriage, law, customs, norms, etc. by doing this you can easily compare and contrast the two societies that you selected for your study. You can set some questions like, is the marriage practices of Catholics are different from Protestants? Did men and women get an equal voice in their mate choice? You can set as many questions that you wanted. Because that will explore the truth about that particular topic. A comparative analysis must have these attributes to study. A social scientist who wishes to compare must develop those research questions that pop up in your mind. A study without those is not going to be a fruitful one.

2. Grounds of comparison

The grounds of comparison should be understandable for the reader. You must acknowledge why you selected these units for your comparison. For example, it is quite natural that a person who asks why you choose this what about another one? What is the reason behind choosing this particular society? If a social scientist chooses primitive Asian society and primitive Australian society for comparison, he must acknowledge the grounds of comparison to the readers. The comparison of your work must be self-explanatory without any complications.

If you choose two particular societies for your comparative analysis you must convey to the reader what are you intended to choose this and the reason for choosing that society in your analysis.

3 . Report or thesis

The main element of the comparative analysis is the thesis or the report. The report is the most important one that it must contain all your frame of reference. It must include all your research questions, objectives of your topic, the characteristics of your two units of comparison, variables in your study, and last but not least the finding and conclusion must be written down. The findings must be self-explanatory because the reader must understand to what extent did they connect and what are their differences. For example, in Emile Durkheim’s Theory of Division of Labour, he classified organic solidarity and Mechanical solidarity . In which he means primitive society as Mechanical solidarity and modern society as Organic Solidarity. Like that you have to mention what are your findings in the thesis.

4. Relationship and linking one to another

Your paper must link each point in the argument. Without that the reader does not understand the logical and rational advance in your analysis. In a comparative analysis, you need to compare the ‘x’ and ‘y’ in your paper. (x and y mean the two-unit or things in your comparison). To do that you can use likewise, similarly, on the contrary, etc. For example, if we do a comparison between primitive society and modern society we can say that; ‘in the primitive society the division of labour is based on gender and age on the contrary (or the other hand), in modern society, the division of labour is based on skill and knowledge of a person.

Demerits of comparison

Comparative analysis is not always successful. It has some limitations. The broad utilization of comparative analysis can undoubtedly cause the feeling that this technique is a solidly settled, smooth, and unproblematic method of investigation, which because of its undeniable intelligent status can produce dependable information once some specialized preconditions are met acceptably.

Perhaps the most fundamental issue here respects the independence of the unit picked for comparison. As different types of substances are gotten to be analyzed, there is frequently a fundamental and implicit supposition about their independence and a quiet propensity to disregard the mutual influences and common impacts among the units.

One more basic issue with broad ramifications concerns the decision of the units being analyzed. The primary concern is that a long way from being a guiltless as well as basic assignment, the decision of comparison units is a basic and precarious issue. The issue with this sort of comparison is that in such investigations the depictions of the cases picked for examination with the principle one will in general turn out to be unreasonably streamlined, shallow, and stylised with contorted contentions and ends as entailment.

However, a comparative analysis is as yet a strategy with exceptional benefits, essentially due to its capacity to cause us to perceive the restriction of our psyche and check against the weaknesses and hurtful results of localism and provincialism. We may anyway have something to gain from history specialists’ faltering in utilizing comparison and from their regard for the uniqueness of settings and accounts of people groups. All of the above, by doing the comparison we discover the truths the underlying and undiscovered connection, differences that exist in society.

Also Read: How to write a Sociology Analysis? Explained with Examples

Sociology Group

We believe in sharing knowledge with everyone and making a positive change in society through our work and contributions. If you are interested in joining us, please check our 'About' page for more information

Causal Comparative Research: Methods And Examples

Ritu was in charge of marketing a new protein drink about to be launched. The client wanted a causal-comparative study…

Ritu was in charge of marketing a new protein drink about to be launched. The client wanted a causal-comparative study highlighting the drink’s benefits. They demanded that comparative analysis be made the main campaign design strategy. After carefully analyzing the project requirements, Ritu decided to follow a causal-comparative research design. She realized that causal-comparative research emphasizing physical development in different groups of people would lay a good foundation to establish the product.

What Is Causal Comparative Research?

Examples of causal comparative research variables.

Causal-comparative research is a method used to identify the cause–effect relationship between a dependent and independent variable. This relationship is usually a suggested relationship because we can’t control an independent variable completely. Unlike correlation research, this doesn’t rely on relationships. In a causal-comparative research design, the researcher compares two groups to find out whether the independent variable affected the outcome or the dependent variable.