Race in Popular Culture: “Get Out” (2017) Essay (Movie Review)

Introduction, description of the themes, academic context, works cited.

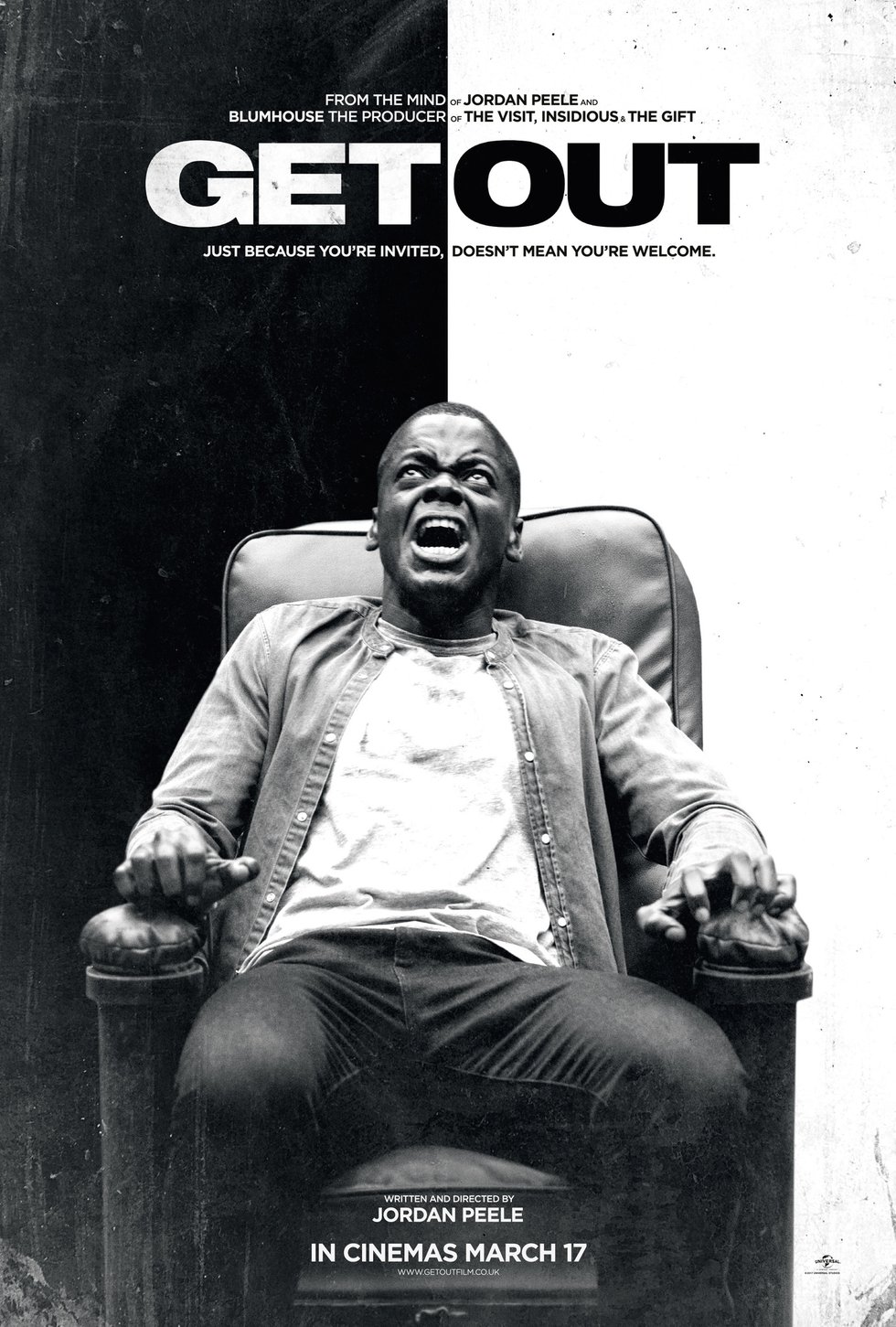

The topic of racism is not new to the American population. The history of this phenomenon has century-long roots, and over time, many opinions and attitudes have developed. This research paper will focus attention on the way popular culture depicts the idea of racial inequality through a content analysis of the movie Get Out . The 2017 film was directed by Jordan Peele and stars Daniel Kaluuya as Chris Washington, a young man who experiences certain changes and specific treatment due to the color of his skin. When a black photographer meets the family of his white girlfriend, he cannot begin to guess how dangerous and strange all the members of the household, including the servants, are. Along with a number of horror scenes, a theme of racism develops, turning the concept into a demon of the 21st century. Modern parties are compared to slave auctions of the past, and a fascination for black skin color proves the power of the white race’s decision-making. As Get Out is a unique example of popular culture, the content analysis of this film shows how crucial the idea of racism is through the prism of human relations and police regulations.

The content analysis of the movie was developed in several stages. First, it was necessary to choose scenes where racism is properly depicted. For example, an early scene shows a young black man talking on a phone and demonstrating mild indignation about the name of the street and the location of this “creepy, confusing-ass suburb” where he feels like “a sore thumb” ( Get Out ). In the end, he is kidnapped by an unknown person in a car. This scene raises the idea that despite evident progress and a lack of obvious racial bias, black people continue to feel uncomfortable in areas where only white people live.

The situation when a police officer asks a passenger for his driver’s license provides evidence that racial prejudice exists in different regions of the United States. A young woman, Rose, expresses concern to her boyfriend about the policeman’s disrespect and tries to change the situation. She tells him that “you don’t have to give him your ID because you haven’t done anything wrong,” and that it is “bullshit” to ask for IDs “anytime there is an incident” ( Get Out ). Although many people, like Rose, have already discarded racial bias, American society still has many racists and other prejudiced people.

During the party, a climax in the discussion of racial issues is shown. In this scene, a white guest begins sharing his opinion about skin color and its role in the modern world. Chris finds it strange to hear that “people want to change. Some people want to be stronger, faster, cooler. Black is in fashion” ( Get Out ). On the one hand, such a phrase could be used to underline whatever benefits black people receive. On the other hand, the desire of a white man to see everything through the eyes of a black man shows his egocentrism and selfishness. In addition, the family focuses on the presidency of Obama as one of the best examples in their lifetime.

Finally, communication between Chris and a black servant, Georgina, was chosen as part of a sampling strategy to discuss black-white relationships. In the movie, the woman shares her thoughts about situations involving “too many white people,” which make her nervous ( Get Out ). At the same time, she underlines that the Armitages have been good to her. Doubtful and uncertain attitudes are evoked in both the character and the audience.

The themes of white-black relationships and the role of the police in racial judgments comprise the two major topics for a thorough discussion. This choice is explained by the necessity to combine human feelings and social norms under which behaviors and relationships are developed. The treatment by police officers or other representatives of the law toward black people varies depending on the decisions of other people. To comprehend better the idea of race and its history, it is important to pay attention to collective and individual thoughts and attitudes.

Racism is always a negative quality, regardless of the population it influences and the outcomes it reaches. However, in discussing racism through the prism of horror movies, its impact is difficult to predict and to understand. In Get Out , racism is not the major topic, but it helps the viewer to gain an understanding of the motives of the characters and the ways they prefer to establish relationships. As stated, the movie depicts the central idea of race in the phrase, used by a white man, that “black is in fashion” ( Get Out ). Notably, black people are not said to be respected or recognized as a race equal to the white race. Although Obama is defined as the best president for the United States, no reasons or additional explanations are given as if this is simply a commonly spoken phrase in the depicted family. Finally, Chris’s desire to know whether Rose’s parents know about the color of his skin shows the fact that sometimes people’s reactions are unpredictable. Any chance to prevent complications or warn about racial differences must be seized.

In addition to everyday human relationships, the attitude of the law toward racism cannot be ignored. The movie contains a short but informative scene with a policeman that demonstrates the potential cruelty and unfairness of people’s judgments. This type of racism may not be obvious, but it cannot be ignored because it also determines black people’s behaviors. In the scene, Rose is driving the car and hits a deer crossing the road. She calls the police and discusses the situation. Even after clarification, the responding policeman asks Chris for his driver’s license, then begins to stutter as he realizes the racial bias evident in his request. At last, he returns the license without looking at it or Chris (see fig. 1). In this situation, Chris has to behave calmly to avoid causing any negative reaction. He follows all instructions and does not find it necessary to disagree or debate, compared to his girlfriend who is eager to protect him and who talks to the officer without restraint.

Both themes in the movie contribute to the discussion about race and inequality. Many black children hear serious lectures from their parents about how to behave with police and how to respond to all official requests. White people are less concerned about the consequences of their communications with police as well as with black people. The level of responsibility, behavioral norms, and respect for each other vary between the representatives of the white and black races, and this paper aims to discuss some aspects of this topic.

Racial biases in human relationships, along with their legal justifications, emerge as serious themes for analysis in the movie Get Out . According to Nierenberg, Peele succeeds in highlighting and satirizing racism in America by “taking certain tropes to their exaggerated sci-fi/horror conclusions,” arguing about “black bodies and who owns them” (500). A slave auction at the party and the desire of a white man to possess the eye of a black man just to see what blacks see introduce the selfish side of the white nation and their compulsion to control everything, even the length of life. Landsberg defines this scene as “an astounding moment, a moment in which a pervasive post-racial discourse coexists with whites stripping African Americans of their civil rights and humanity” (638). Even as the characters express their recognition of the black president and his qualities, they are ready to bargain for his body, physical power, and other distinctive features.

The duty of the police is to make sure that all citizens follow the same rules and behave in accordance with existing laws. However, it is not always easy to prove the correctness of law enforcement actions. Banton says that people have tried “to make bad things better by change of name…to make things disappear by giving them bad names” (21). Although in the scene, such words as “race,” “skin,” or “origin” are not used, these concepts evidently bother all three characters at that moment. Therefore, Peele can easily call Banton’s words into question and prove that bad things never disappear. Boger shows that “black men are at once something to be ridiculed, something to be used for sports or military aims, to be jailed, and to be hated” (150). Even when are no reasons for imprisoning a person, a white man will always try to find another cause to uphold his attempt to control the black body physically or emotionally. Yancy underlines the importance of black resistance to white power in avoiding black people’s disappearance without a trace (1294). Thus, the movie serves as a call to action for black people.

It may be possible that even the creators of the movie Get Out could scarcely predict the impact that the theme of the race could have on this popular culture example. Instead of a cheap and predictable horror movie, the audience receives a captivating story about choices, dependence, and the desire to control everything. Compared to other modern horrors, Get Out reveals the idea that despite their intentions to be united and supportive, people cannot get rid of their racial biases and deeply rooted prejudice. It is possible to hide true intentions by a variety of means, but in the end, a final choice must be made: will the individual be a master or a slave? Racism can exist in different forms, and people are not able to recognize all of them even when confident in their powers and abilities. Black resistance has a long history, and Get Out provides a reminder of causes and outcomes that can be observed in human relationships, police behavior, and political change.

Banton, Michael. “The Concept of Racism”. Race and Racialism , edited by Sami Zubaida, Routledge, 2018, pp. 17-35.

Boger, Jillian. “Manipulations of Stereotypes and Horror Clichés to Criticize Post-Racial White Liberalism in Jordan Peele’s Get Out.” The Graduate Review , vol. 3, no. 1, 2018, pp. 149-158.

Get Out. Directed by Jordan Peele, performances by Daniel Kaluuya, Allison Williams, and Bradley Whitford, Universal Pictures, 2017.

Landsberg, Alison. “Horror Vérité: Politics and History in Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017).” Continuum , vol. 32, no. 5, 2018, pp. 629-642.

Nierenberg, Andrew A. “Get Out.” Psychiatric Annals, vol. 48, no. 11, 2018, p. 500.

Yancy, George. “Moral Forfeiture and Racism: Why We Must Talk about Race.” Educational Philosophy and Theory , vol. 50, no. 13, 2018, 1293-1295.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, July 7). Race in Popular Culture: "Get Out" (2017). https://ivypanda.com/essays/race-in-popular-culture-get-out-film-analysis/

"Race in Popular Culture: "Get Out" (2017)." IvyPanda , 7 July 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/race-in-popular-culture-get-out-film-analysis/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Race in Popular Culture: "Get Out" (2017)'. 7 July.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Race in Popular Culture: "Get Out" (2017)." July 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/race-in-popular-culture-get-out-film-analysis/.

1. IvyPanda . "Race in Popular Culture: "Get Out" (2017)." July 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/race-in-popular-culture-get-out-film-analysis/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Race in Popular Culture: "Get Out" (2017)." July 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/race-in-popular-culture-get-out-film-analysis/.

- First Draft of Policeman of the World Paper

- The United States as a Policeman of the World

- Anti-Black Discrimination in the “Master” Film

- Roberta from "Desperately Seeking Susan" Film

- Ethical Dilemma in “The Reader” Film by S. Daldry

- "Newsies" by Kenny Ortega and the Industrial Revolution

- Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho" Annotation

- "The Cabin in the Woods" Horror Comedy Film

Find anything you save across the site in your account

“Get Out”: Jordan Peele’s Radical Cinematic Vision of the World Through a Black Man’s Eyes

By Richard Brody

In “Get Out,” one of the great films by a first-time director in recent years, Jordan Peele borrows tones and archetypes from horror movies and thrillers, using them as a framework for the most personal of experiences and ideas: what it’s like to be a young black man in the United States today. The film follows a young black photographer, Chris Washington (Daniel Kaluuya), who goes with his girlfriend, Rose Armitage (Allison Williams), who is white, to her family’s suburban home. She hasn’t told her parents that Chris is black; she tells him not to worry, that they’re not racist at all. Her parents, Dean (Bradley Whitford), a neurologist, and Missy (Catherine Keener), a psychiatrist, are warm and welcoming, yet Chris senses that something is amiss. Rose’s brother, Jeremy (Caleb Landry Jones), a medical student, is oddly aggressive. The family’s staff, Georgina (Betty Gabriel) and Walter (Marcus Henderson), middle-aged black people, seem oddly distant, mentally neutralized, remote-controlled. A gathering of family friends thrusts Chris among clueless white people (and one clueless Japanese man) who make grossly insensitive, racially charged remarks that are meant to seem friendly; he meets another young black man, Logan King (Lakeith Stanfield), whose behavior seems whiter than white; and, when he realizes that he needs to get out, it’s too late—the dreadful plot for which Rose’s family is grooming him has already been set into motion.

Peele tells this story by way of clearly delineated, skit-like scenes featuring sharply aphoristic writing and precise (often uproarious) satirical comedy. But, above all, he does so through an ingeniously conceived and realized directorial schema. “Get Out” isn’t an innovation in cinematic form but in the deployment of found forms. He uses familiar devices and situations in order to defamiliarize them; he relies on sketch-like foregrounding of genre characters—nearly stock characters—in order to make commonplace, banal experiences burst forth like new to convey philosophically rich and politically potent ideas about the state of race relations in America. The story itself, with its sense of nefarious purpose hidden beneath a warm welcome, only hints at the depth, the complexity, the subtlety, and the radicalism of his vision.

The depiction of a prosperous suburban white experience is a long-standing cinematic banality, and the depiction of the life and experience of a young black man—particularly one who isn’t a gangster, a criminal, or a street-smart hustler—is a cinematic curiosity and rarity. But Peele does more than depict Chris—he depicts the white world as seen through Chris’s eyes. “Get Out” contains some of the most piercing, painful point-of-view shots in the recent cinema. When Chris arrives at the Armitage estate in the passenger seat of Rose’s car, for instance, he looks out the window and sees Walter, the black groundskeeper, at work; he sees Georgina, the black housemaid, serving the family at an outdoor table, and sees her, later on, through the lens of his camera. At the garden party, the Armitages’ friends are introduced from Chris’s point of view, and Logan, discerned by Chris from afar, appears in his field of vision like a welcome companion with a sense of relief that the image itself captures.

The very pivot of the film—a mind-control scheme to which Chris is being subjected—involves hypnosis, which Missy accomplishes by way of a distracting object, a spoon tinkling in a fancy teacup. It’s the dainty sound made by objects and gestures of genteel dignity and refined luxury. (Chris suffers, in effect, from aspirational hypnosis.) Peele fills the films with other objects, sounds, phrases, and gestures that take on a comically, insidiously outsized significance, from Dean’s greeting of Chris as “my man” and his use of the word “thang” to Jeremy’s mention of Chris’s “genetic makeup” and Georgina’s curious translation of Chris’s word “snitch” to the much whiter-sounding “tattletale.” Through Chris’s eyes and through Peele’s images, seemingly innocuous or merely peculiar things become charged with personal and political meaning: the childlike count of “one Mississippi, two Mississippi,” a wad of cotton, a set of shackles, partygoers holding up numbered paddles like bidders at an auction. The sight of a police officer and his request for I.D., the very notion of genetic qualities, and, for that matter, the very concept of seeing and being seen—or of not being seen—emerge in “Get Out” as essentially racialized experiences, fundamentally different from a white and a black perspective.

This subtle, strange, bitterly comedic emphasis on the totemic and symbolic power of objects, as seen through the eyes of the film’s protagonist, lends Peele’s direction classical reverberations. Even more than a Hitchcockian tone, Peele recaptures and reanimates the spirit of the films of Luis Buñuel, whose surrealistically eroticized Catholic heritage made him a supremely sly Freudian symbolist. In “Get Out,” Peele’s own cinematic historical consciousness, transformed through his own inner architecture of political thought, blasts this classical style into the future.

Spoiler alert: the macabre plot of “Get Out” involves some weird science that’s meant to create black bodies without blackness, black minds devoid of black consciousness. I confess: I expected that, because Chris is a photographer, the movie would offer a photographic resolution to Chris’s drama—something akin to the way that, in the dénouement of “Rear Window,” Jimmy Stewart uses flashbulbs on his camera to blind his assailant, Raymond Burr. What Peele offers instead is something much wilder, something ingenious. At the time of dramatic crisis, Chris is denied the tools of his art; he has no camera on hand, and, what’s more, he’s being force-fed an audiovisual diet—through a nineteen-fifties-style television console—that is the very essence and tool of his captivity and his subjection. The Armitages aren’t creating slaves; they’re doing something that’s in a way even worse. Slaves are, at the very least, conscious of their situation and can, at least theoretically, if the opportunity arises, revolt. What the Armitages are creating is inwardly whitened black people—black people cut off from their history and their self-consciousness and, therefore, deprived of the power to rebel and to free themselves.

Peele’s furious, comically precise lampooning targets two intersecting strains of racism. The Armitages’ friends see Chris’s blackness; they don’t see Chris, but they at least perceive that blackness as a fact, a phenomenon, albeit one that they have no idea how to deal with. The impeccably liberal Armitages, by contrast, are color-blind; in their cosmopolitan embrace, they affirm, with the best of intentions, that there’s no difference between blacks and whites, thus, in effect, denying that blackness—the distinctive black experience—is real. Rose even brings the matter directly into the film, asking Chris, “With all that ‘my man’ stuff, how are they different from that cop?”—the cop who had requested Chris’s I.D. when they hit (or, rather, were hit by) a deer, with Rose behind the wheel. That is the question: How are white liberals such as the Armitages different from racist oppressors who assert their power over blacks in terms of their presumptions of black people’s inferiority? Peele, boldly and insightfully, offers an answer: the cop sees differences, albeit the wrong ones; the Armitages see no differences. But the actual differences between white and black Americans aren’t, of course, biological or qualitative but political, psychological, experiential. The reality of the black experience, in “Get Out,” is revealed to be historical consciousness.

For all the talk of “Get Out” being slotted into the genre of a horror comedy, the horror elements are strongly—and, clearly, intentionally—underplayed. The biggest jump moment is utterly innocuous, a middle-of-the-night apparition that’s in no way physically menacing—but gives a hint of the menace looming beneath the family’s placid surfaces. There’s violence and blood, but Peele deliberately hides the worst of it with sharp editing and canny framings; he’s interested not in the physical horror but in moral ones, and in the moral clarity that comes from common wisdom infused with tradition. Chris, a photographer who moves in artistic circles, is himself a sort of black liberal, overcoming his doubts about the weekend as he tries to persuade his best friend, Rod (Lil Rel Howery, in a scintillating comedic performance), a T.S.A. officer, that no harm can come of the visit. Rod’s suspicions, which he delivers with sharp common sense, no-nonsense vigor (and acts on by way of his professional skills), cut closer to the truth of his and Chris’s shared experience than does Chris’s cultivated sophistication. The revelation of the racialized world surrounding Chris comes off as his personal discovery of it as well. In its own way, the experience that Peele dramatizes is as cautionary as it is self-cautionary.

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Daniel Zalewski

By Anthony Lane

By Zadie Smith

Get Out: The Horror of White Women

by Sophie Hall

December 8, 2020

Get Out was one of the biggest successes of 2017. With a budget of $4.5 million, the film grossed over $200 million worldwide, won director/screenwriter Jordan Peele an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, and became one of the most influential films of the decade. Get Out deftly weaves various genres, but settling on one has caused mild controversy, as when it was nominated for Best Musical or Comedy at the 2018 Golden Globes, Peele disagreed and stated, “…it [ Get Out ] was a social thriller.” However, I feel that Get Out ’s genre is undoubtedly horror due to one key factor—the character of Rose Armitage and how she uses her race as a weapon.

Get Out follows the story of Chris Washington, a twenty-six-year-old aspiring photographer. He is in a relationship with Rose, a WASP-y but seemingly woke white women of a similar age. One weekend, Rose invites Chris to meet her parents at their remote country home—“Do your parents know I'm Black?” Chris asks awkwardly. “No,” Rose lies. “Should they?”

Indeed they should—it is later revealed that Rose becomes romantically involved specifically with Black men (and sometimes women) in order to take them to her father, a neurosurgeon so that he can transplant the brains of his (mainly white) friends and family into their bodies, as Black skin is deemed more desirable.

Throughout the film, we see Rose using her race as a way to ensnare and manipulate Chris. Firstly, we see Rose using her white privilege as a way to trap Chris. In the film’s first act, Chris and Rose encounter a police officer on their way to her parent’s house. The officer asks to see Chris’s license (even though he wasn’t driving the car) and Rose calls the officer out on his 'bullshit.'

However, what initially appears to be Rose standing up against institutionalized racism in the police force is chilling in hindsight; she was doing it so that Chris’ details were not recorded for when he later goes missing. The fact that she was able to do this was due to her white privilege—Chris, a Black man, alone, would not able to convince the officer to let him go otherwise.

Another way in which Rose uses her white skin to her advantage is by falsely displaying herself as an ally. On their first night at her parent’s house, Rose rants about her parent’s apparent lack of cultural awareness around Chris, sounding even more appalled than he does, who experiences it firsthand. On the DVD commentary, Jordan Peele said that “I think the scene is pivotal in our not suspecting her… the fact that she’s more turned up about this than he is.”

Later, in the scene where Chris decides to stay at the Armitage’s home because of his love of Rose, she deceives him further by suggesting that they should in fact leave. Rose’s deception is revealed in a killing blow at the end of Act II, where she iconically reveals that she has Chris’ car keys, preventing him from leaving and exposing her part in the plan.

Chris is then physically restrained by Rose’s brother and put into the 'sunken place' by Rose’s mother. However, the unique thing about Rose’s villainous reveal was not the fact that she was a ‘bad guy’, but the way it was executed.

Instead of telling Chris that she despised him or was revolted by them being together, she calmly says, ‘You were one of my favorites’ as if consoling him. It’s not just a shocking plot twist, it’s an emotional gut punch.

For The Guardian , journalist Lanre Bakare writes: “The villains here aren’t southern rednecks or neo-Nazi skinheads, or the so-called 'alt-right.' They’re middle-class white liberals… It [ Get Out ] exposes a liberal ignorance and hubris that has been allowed to fester. It’s an attitude, an arrogance which in the film leads to a horrific final solution, but in reality, leads to a complacency that is just as dangerous.”

And that ‘complacency’ is just what makes Rose so horrifying—she is just as racist as a so-called ‘neo-Nazi skinhead,' but she doesn’t realize this because of her so-called liberal ideals. The Armitage family wants Black bodies not to erase them but to inhabit them for their more admirable traits. In a weird way, Rose doesn’t see herself as racist—she thinks she’s paying him a compliment by having chosen him in the first place.

This attitude is a deliberate reflection by Jordan Peele on contemporary America. In the aftermath of Trump winning the 2016 election against Hillary Clinton, widespread marches erupted across America (and the world) which focused on Trump’s history of sexual assault and misconduct.

However, the marches at large failed to address the fact that 53% of white American women voted for Trump, a shocking comparison to the 94% of Black women who voted for Clinton. White women contributed greatly to Trump being elected, but the white women who went on the marches against Trump only considered the effect on their rights and not the additional impact on the rights of Black women and women of color.

Another way in which Rose uses her white privilege as a source of horror was in her phone conversation with Chris’ friend Rod. He was concerned and suspicious of Chris’ sudden disappearance and was enquiring about his whereabouts. Rose initially acts innocent and tries to draw sympathy from Rod, saying she’s ‘so confused’ by the situation.

However, when Rod doesn't fall for Rose’s ploy, she changes tactics; she states that the reason Rod called was because of his alleged sexual attraction to her, asserting that she knows ‘you [Rod] think about fucking me.’ Rod hastily hangs up, adding that Rose is a ‘genius.’ And Rod is telling the truth; Rose is not only weaponizing her whiteness but her white femininity.

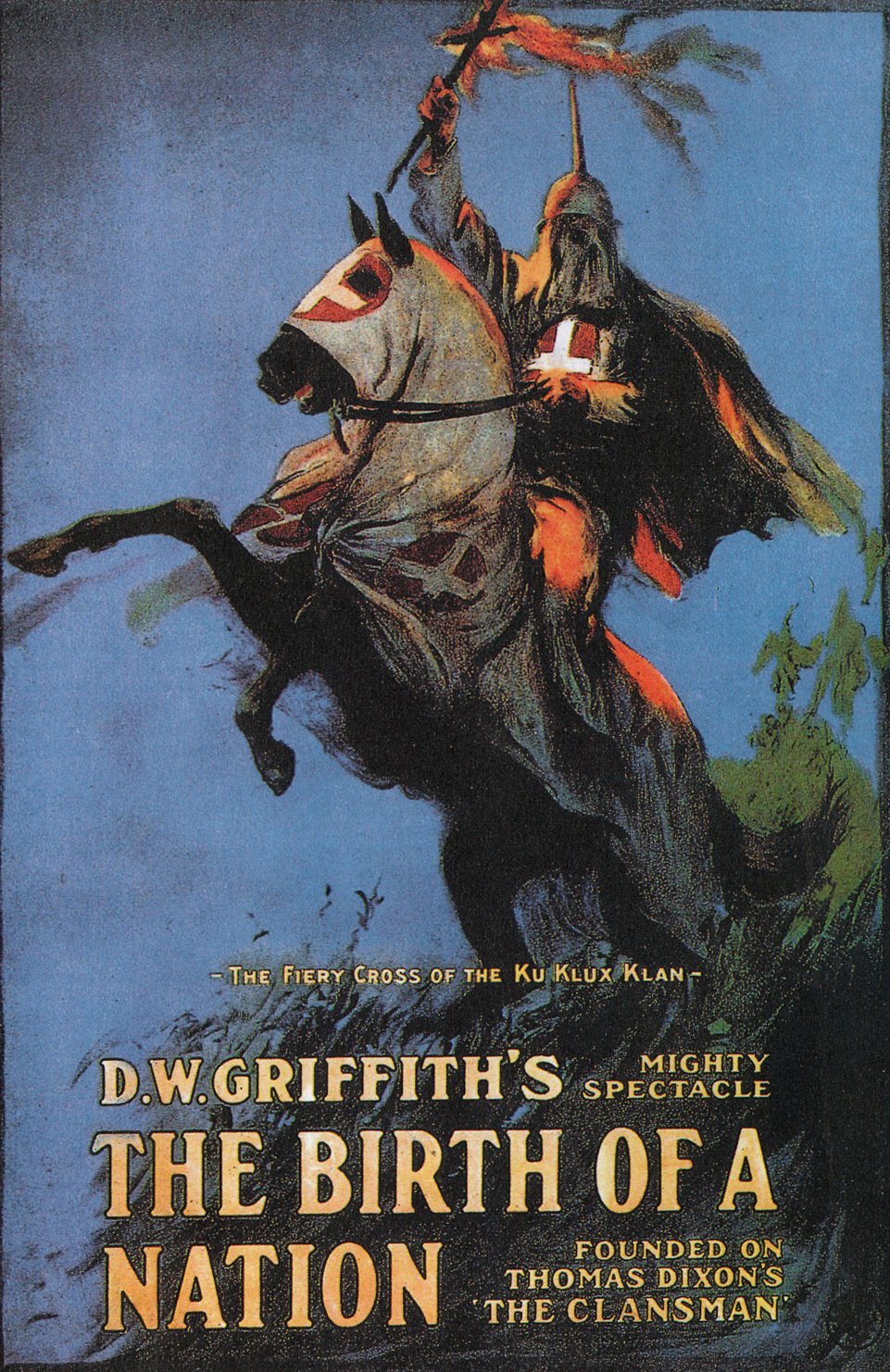

The fear of Black men attacking white women has been ingrained in the American subconscious for over a century. The film The Birth of A Nation helped to create this fear—in Ava DuVernay’s documentary 13th , writer/educator Jelani Cobb notes: “There’s a famous scene where a woman throws herself off a cliff rather than be raped by a black male criminal. In the film you see black people being a threat to white women.” Despite this, The Birth of A Nation was (and still is) considered to be one of the greatest films of all time, and until recently was still being taught in film schools across America.

The idea of Black men being a threat to white women was still being peddled by American society well into the 21st century, with one of the recent prominent examples being the Bush vs. Dukakis presidential election in 2003. Dukakis wanted criminals to have weekend releases and to combat this, Bush’s campaign used Willie Horton, a Black man convicted of raping a white woman as a fear-mongering tactic against Dukakis.

Again in 13th, Harvard professor Khalil G. Muhammed states: “Bush won the election by creating fear around black men as criminal, without saying that's what he was doing... It went to a primitive fear, a primitive American fear because Willie Horton was metaphorically the black male rapist that had been a staple of the white imagination since the time just after slavery.”

Rose not only uses this American fear against Rod but also against Chris. In the film’s final act, Chris manages to escape the Armitage home and the fate of all of Rose’s previous exes. Rose pursues him with a shotgun but is ultimately mortally injured by Walter, a Black gardener whose mind was occupied by Rose’s grandfather.

As Rose lays on the road dying, Chris goes to her and begins to strangle her. He cannot bring himself to finish the job, however, but it doesn’t matter—flashing lights fill the screen, and Rose, thinking it’s the police, theatrically cries for help.

In the theatrical ending, it turns out to be Rod coming to Chris’ rescue, not the police coming to Rose’s, much to the audience's delight. However, Jordan Peele originally had a much bleaker idea in mind and shot an alternate ending, one that did indeed have the police arriving and Chris ultimately put in prison.

In the podcast Another Round, Peele notes that “The ending in that era was meant to say, ‘Look, you think race isn’t an issue?’ Well, in the end, we all know how this movie would end right here.” And it’s true, hence why Rose immediately started to cry for help when she saw the lights.

Although a fictional film, we know that the image of Chris, a Black man, crouching over a wounded white woman, would’ve been a life sentence for the character. Even though she would’ve died in both endings, Rose could’ve still won in the alternate ending due to her race.

Catherine Keener’s character Missy Armitage also uses her whiteness as horror in Get Out . In the aforementioned podcast, Peele explains, “The idea of getting hypnotized or being in a psychiatrist’s chair which is partially playing off of the stereotype and generalization that the Black community hasn’t exactly embraced therapy as a means to get to your inner turmoil…religion is where it goes.” Missy’s character using a therapeutic technique to manipulate Chris was a deliberate ploy by Peeleto to create anxiety in the Black audience and more specifically have that anxiety being sourced by a white character.

Even though the other two members of the Armitage family, Dean and Jeremy, can physically antagonize Chris—Dean, the father, would be the one to perform the operation on Chris and Jeremy, the son, is his physical opponent,—neither affect Chris’ psychology or character development in the way that Missy and Rose do.

In John Truby’s novel The Anatomy of Story , the writer proposes, “Create an opponent… who is exceptionally good at attacking your hero’s weaknesses.” Both Missy and Rose do exactly this—Missy introduces a weakness of Chris, the fact that he left his mother to die, and brings it to the fore. This leads Chris to decide to stay with Rose later in the movie, as he tries to right the wrongs he made in the past for her. Missy exposed Chris’ weakness and Rose exploited it. The actions of the two women are what help drive the narrative forward.

Another way in which Peele made Rose a source of horror in Get Out was altering the ‘final girl' trope. Like most final girls, Rose is white, young, intelligent, and spends the majority of the film in an isolated house. However, instead of being the one to escape the monster and live to tell the tale, she is the monster and is ultimately the one who is defeated by the film’s true hero.

Furthermore, in their video essay on ‘Final Girls’, The Take surmises, "The flip side to the ‘final girl’ after all is the ‘black guy dies first’ trope. While audiences are expected to be terrified for the white girl, the deaths of black characters are regarded as just part of the show.” The fact that Rose is the film's baddie is subversive, but the way that Peele wrote for Chris, a Black man, to be the one to defeat her, is a delicious spin on audience expectations of the horror genre.

This new take on the 'Final Girl’ seems to have ushered in a new generation of women in horror—since Get Out’ s 2017 release, we have since seen Suspiria , Midsommar , and Us (also by Peele), where the final girls are either the villains or go to dark lengths in order to achieve their goals. Final girls are no longer enduring horror—they are inflicting it.

Rose Armitage is one of the scariest on-screen villains in recent years, but not because she has fangs or wields a chainsaw—it is because we know someone like a Rose in real life. Rose is the most dangerous character in Get Out because she is the most real. Even though her malevolence is overwhelming, Jordan Peele does not want audiences to cower from her, but rather face her head-on.

Get your copy of the Get Out 4K Blu-ray by clicking here.

Get your copy of the Birth of a Nation DVD by clicking here.

If you want to learn more about race and the film, order the book Critical Race Theory and Jordan Peele's Get Out.

65 Get Out (2017)

The horrors of black life in america in get out.

By Paige Mcguire

The film Get Out by Jordan Peele gives us a unique insight into the horrors of black mens life in America. His thriller, although it is somewhat dramatized shows how real and scary it is to be a man or woman of color. Throughout the film, we see multiple systemic racist issues and stereotypes. I plan on giving you an overview of the film and go into depth on a couple of scenes from the film and describe the issues they show relating to discrimination in film, as well as real life. Lastly, I will talk about Jordan Peele’s alternative ending as well as a short review of the film and how it changes the way we look at horror.

In Get Out we get a really interesting perspective into a black man named Chris’s life and his relationship with a white woman named Rose. In the beginning of the film, Chris and Rose are on their way to Rose’s parents’ house in the country for the weekend. They have a brief interruption when a deer runs out in front of them and clips their car. The police came to check out the scene and make sure everything was okay. However, they also asked Chris for his license and assumed he was suspicious due to the color of his skin. Fast forward, Chris and Rose make it to Rose’s parents’ estate. Their house is huge and comes with a pretty large amount of land.

Everyone in the family, including Chris, gather for a welcome lunch. This is when Chris begins to initially become uncomfortable. Chris is starting to realize all of the help Rose’s family has around the house is of color. Rose’s dad does his best to explain to Chris that it is not “like that” they had just been with the family helping with the grandparents before they both passed. The next day Rose’s family hosts a huge friends and family get-together. This is probably one of the most important scenes of the whole movie, which we will get into more later. In this portion of the film everyone is coming up to introduce themselves to Chris with that however there are many subtle and not so subtle hints of racism. Chris finally sees someone at the gathering who is of color and approaches him in hopes of finding a friend. This scene turns dark when Chris notices the man seems off and isn’t acting like how a man Brookelyn would usually act. Chris snaps a picture of the man which sends him into a frenzy. The man tried to attack Chris, and screamed at him to “get out”.

After everything had calmed down with the man Chris still seemed unhappy. He and Rose go on a walk to cool down and talk while the rest of the people gather for “bingo”, or so Chris thought. Chris is able to convince Rose to leave because he isn’t comfortable. The two head back to the house to pack as everyone leaves the gathering. As Chris and Rose attempt to leave the house, things become tense. Rose can’t find the keys. This scene is where Rose reveals her true colors of actually trying to trap Chris. The family knocks Chris out using hypnosis which is previously used in the film. The entire time Rose and her family were trapping black men and women so they could brainwash them and use their bodies to live longer and healthier lives via a special brain transplant. They thought of African-Americans as the most prime human inhabitants; they would be stronger, faster, and live longer in a black person’s body. Chris is able to fight against them and free himself. With the price of having to kill pretty much every person in his way. His friend from TSA shows up cause he knew something was fishy and was able to save him from the situation.

Now that you have gotten the basic overview of the film I want to investigate a couple of scenes from the film and explain their importance. Starting off with the first scene where Chris is getting introduced at the gathering (43 min). This scene was where I felt as the viewer you started to see major examples of systemic racism. It seemed like every person who met Chris had something to say that could be taken offensively. In this scene they mostly used medium close-ups, showing primarily the upper half of the body. The cuts were pretty back and forth cutting from one person’s point of view in the conversation to the others. I feel like this kind of editing really adds to the scene in the fact that you can see one another’s reactions. This is important because some racist discussions occur. A couple examples are a man who said that “Black is in fashion” and a woman asked Rose in front of Chris if the sex was better. These are stereotypes that have been supported by film and other media for years and years. In fact Chapter 4 of Controversial Cinema: The films that outraged America , it brings up the fact that for many years black men and women were portrayed as more violent as well as more sexual. Equality in film is still something we’re working on today in general, and we are getting there but I think it’s important to see how much film and media have influenced us and given us a specific way that we view others. If the media is telling us to view black men as more sexual and aggressive it creates a stereotype in real life.

The second scene that I felt was really worth mentioning was when Chris and Rose go off to talk while the family plays “bingo” (59 min). The reason I say “bingo” is because they say they’re playing bingo, however when the camera begins to zoom out and pan across everyone sitting and playing you find out kind of a scary truth. In the beginning of the scene it starts off with a very tight close-up on Rose’s father, and it starts to zoom out from his face showing his gestures. Well obviously when you play bingo there is talking sometimes even yelling but no, it was dead silent. During this time Chris and Rose are off on a walk having an uncomfortable conversation. Chris feels like something is wrong, he’s not comfortable and would like to leave. The cameramen cut back and forth between these two scenes. AS the cut back to the bingo scene each time more and more of the actual scene is revealed. They are panning outward to show what they are actually doing, which is bidding on who gets to have Chris. A blind art critic ends up winning the bid, which means he will be getting to have Chris’s body to brain transfer into. There was a sort of foreshadowing earlier in the film when this man said that Chris had a great eye, this man quite literally wanted Chris’s eyes.

Now, this bidding and purchasing of people is not a new subject or idea to any of us. We should all be aware of slavery and the purchasing of African-Americans in history. That’s why I feel like it was an extra shock to see this is in this film, set in 2017. The hopes would be that stuff like slavery would not be happening anymore but I feel like Jordan Peele had a specific idea when writing this film to inform others of the struggles of African-Americans of every day and to realize that. Yes, this may be a very eccentric way of explaining it but people want the power of black people, and this is still a problem even if it’s not something on the news every day.

In fact, Jordan Peele had an alternative ending to this film that I felt like I truly needed to include. So, in the actual ending of Get Out Chris escapes the house and Rose comes after him. Chris ends up sparing her because he did love her at one point and couldn’t bring himself to do it. He sees a police car roll up, he puts up his hands and is greeted by his friend from TSA. Chris makes it out a free man. Peele revealed later that he decided to have a happier ending because at the time when the film was filmed was when Obama was still in the presidency and he had seen hope for the country. With that being said 2017 was the first year of Donald Trump’s presidency. Situations in the film like police brutality or racism via a policeman have since been more popular. So I think it’s important to include the alternate ending because Peele felt it was more realistic. So, in the alternate ending Chris makes it out of the house and Rose is coming after him. Chris instead of sparing Rose chokes her to death. A car rolls up, Chris puts his hands up and is greeted by the police. The police arrest him, and take him to jail. Now, Chris had basically been abducted, almost murdered, hypnotized, and more. Yet he was still sent to jail, this was because the house went up in flames. There had been no evidence.

In the world we live in I truly believe along with Peele that this would have been the actual outcome of the situation. Unfortunately, our system is corrupt, and this is the type of outcome many black men and women face every day. We have seen situations like this many times this year with people like George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks, Stephon Clark, and many many more. Awful things happen to people of color every day, and I truly believe that that was Peele’s goal to get this across to people. On Rotten Tomatoes, critic Jake Wilson made a remark saying “This brilliantly provocative first feature from comic turned writer-director Jordan Peele proves that the best way to get satire to a mass audience is to call it horror.” Honestly, I really agree with this statement. People don’t want to hear about bad stuff going on in the world especially if it doesn’t apply to them or their race. However, people go to see a thriller to see bad stuff happen, to be on their toes. This method of getting people to sit down to watch a thriller and have it show real problems is entirely the smartest thing I have ever seen.

In conclusion, the film Get Out really makes you think about the life of African-Americans from a new perspective. As a white person, I will never know truly what it’s like or the pressures that arise from being a person of color in society. All I can do is inform myself, and fight for change to be made. I think Jordan Peele is changing the way we see horror. More often than not a horror film is made up of characters and situations that realistically would never happen. Get Out shows problems from real-life situations at an extreme level but it forces people to sit down and actually, truly understand something larger than themselves.

Get Out (2017). (2017). Retrieved November 18, 2020, from https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/get_out

Phillips, K. R. (2008). Chapter 4: Race and Ethnicity: Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing. In Controversial cinema: The films that outraged America (pp. 86-126). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Difference, Power, and Discrimination in Film and Media: Student Essays Copyright © by Students at Linn-Benton Community College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Awards Shows

Get Out is a horror film about benevolent racism. It's spine-chilling.

Jordan Peele's directorial debut shares DNA with other classics of horror in the best way possible.

by Alissa Wilkinson

The premise of Get Out has been done before: A young black man ( Daniel Kaluuya ) goes home with his white girlfriend ( Allison Williams ) to meet her parents. You can pretty much fill in the blanks from there.

Except, gloriously, you can’t. Get Out — written and directed by Jordan Peele , half of the celebrated comedy duo Key and Peele — makes the incredibly smart move to cast this story about racism not as a drama or comedy, but as a horror film.

Racism is scary, of course. But Get Out isn’t about the blatantly, obviously scary kind of racism — burning crosses and lynchings and snarling hate. Instead, it’s interested in showing how racist behavior that tries to be aggressively unscary is just as horrifying, and in making us feel that horror, in a visceral, bodily way. In the tradition of the best social thrillers, Get Out takes a topic that is often approached cerebrally — casual racism — and turns it into something you feel in your tummy. And it does it with a wicked sense of humor.

Get Out is about a black man who stumbles into a very white, very weird world

After dating for about five months, Chris (Kaluuya) and Rose (Williams) are headed upstate to hang out with her aggressively white parents, neurosurgeon Dean ( Bradley Whitford ) and therapist/hypnotist mother Missy ( Catherine Keener ). Chris is a little worried about Rose’s family’s reaction to him — she hasn’t told them that her boyfriend is black — but they’re very nice to him, even if Dean’s pointedly enthusiastic comments about the achievements of Olympian Jesse Owens and loving Obama come off as a bit clueless.

The estate is tended by a groundskeeper named Walter ( Marcus Henderson ) and a housekeeper named Georgina ( Betty Gabriel ), both of whom are black. Dean apologizes to Chris about the optics of two black servants at a white family’s estate seeming a bit regressive. Rose’s brother Jeremy ( Caleb Landry Jones ) also turns up, to get drunk and tell embarrassing stories about his sister. Things settle into a normal family routine. Everyone’s excited for an upcoming annual party to which all the family friends are invited.

Then things start to get weird. Chris, a habitual smoker, can’t sleep the first night and steps outside to have a cigarette. He sees some odd activity on the premises, and when he comes inside, he has a strange encounter with Missy. When he wakes up the next morning in a cold sweat, things still seem … off. Later, when he tries to call his buddy Rod ( Lil Rel Howery ), a TSA agent, he discovers his cellphone has been randomly unplugged and now has no power. And at the party, the only other black guy, Logan ( Lakeith Stanfield ), is acting really weird.

The less you know about where Get Out goes from there, the better. The element of surprise is what makes the movie fun to watch, and the cathartic third act had the audience I saw the film with hollering at the screen and applauding.

Get Out draws on the visceral experience of being objectified or colonized by another consciousness

From the beginning of the film, Peele’s directorial vision is clear: creepy, funny, totally contemporary and aware of what it’s doing. The movie vacillates between shots that belong to comedy — conventional over-the-shoulder shots that let you feel like you’re in on the conversational joke — and shots that belong to horror — empty patches of screen that make you feel like someone could jump out at any moment. It’s a remarkably assured and confident debut from Peele, and perfectly cast.

It’s clear that Peele is drawing on a long tradition of social thrillers and horror films. In fact, he recently curated a series of them at the Brooklyn Academy of Music to coincide with the release of Get Out , and the films he picked are revealing. Among them are Night of the Living Dead, Funny Games, The Silence of the Lambs, The Shining, and the film I couldn’t stop thinking about while watching this one: Rosemary’s Baby .

Most of these films draw on a very particular terror: the feeling of having your personal space or your own body invaded by some other consciousness, usually one with malicious intent. That can take the shape of home invasion ( Funny Games ), or slowly going nuts ( The Shining ), or zombification ( Night of the Living Dead ), or being literally consumed by someone else ( The Silence of the Lambs ).

Rosemary’s Baby holds a particularly visceral spot in horror film history for women , as it draws on the complicated feeling of having another being in your body during pregnancy, as well as being seen as an object, a body to be remarked upon and talked about. (That’s hardly a phenomenon experienced only by pregnant women, of course.)

The feeling of being turned into an object to be feared, desired, or operated upon is also part of Get Out , though in this case it’s positioned in terms of the black body, particularly the body of a black man. Nice white people talk to him and about him in ways that make it clear he’s not like them — whether it’s about his “frame” and “genetic makeup” or about black skin “being in fashion” or asking Rose if it’s true that “it” is better. (We know what that person means, and so do Rose and Chris.)

Chris endures it all with a smile that seems born of years of having to put up with this kind of thing, and we’re allowed in on the joke. These clueless white people are trying to be cool in front of Chris, whom they just sort of think must be cool because he’s black, and he’s indulged it. He wears the same expression when he and Rose talk to a cop after they accidentally hit a deer on their way up north, and the policeman who responds to their call insists on seeing Chris’s ID — something Rose soundly rebuffs in words that would get Chris hauled away in the back of the cop car (though her act takes on a different meaning later in the movie).

Get Out is a movie about double consciousness, and it pulls off its goal with skill

In the film’s final act, the racism subtext becomes text in a big way, which reveals what Get Out was after all along. The film taps into the phenomenon of double consciousness , which W.E.B. Du Bois wrote about in an essay that appeared in his 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk .

In the essay, Du Bois identified the feeling of having an identity that’s been splintered into several parts — of “always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tale of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.” He continues:

One ever feels his two-ness, — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder. The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife — this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost. He does not wish to Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa. He wouldn't bleach his Negro blood in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of opportunity closed roughly in his face.

Since Du Bois, the idea has been adapted by women, especially black feminists writing about living in patriarchal societies. Chris’s experience embodies a 2017 version of Du Bois’s, both in how he experiences his two-ness among the folks upstate and how he relates to Walter and Georgina.

(The film itself seems a bit doubly conscious, though in a different way; it both embodies and winks at some of the tropes common to horror films, which obviously signal that everything isn’t going to be hunky-dory at Rose’s parents’ house. After all, it’s titled Get Out . You kind of know what’s coming.)

The experience of being observed matters here, and the manner in which one is observed and becomes the object of desire — a sort of fetish object — is at the center of Get Out , even though it doesn’t call attention to the idea specifically.

The deft way this is handled in the script — and the multiple ways the theme is layered into the film, including several repeated visual symbols and motifs — makes Get Out a great candidate to join the classics of social horror, since it’s unusual to see any movie pull off this approach with respect to the topic of race.

I’m white, and have no idea what it’s like to be a black American, and I never really can understand it instinctively, no matter how much I try to empathize. But my female body thrilled sickeningly with recognition when I saw Rosemary’s Baby , and I felt an echo of that same sensation watching Get Out . Which makes me wonder if — just maybe — a great, funny, well-made horror movie like Get Out can, while not totally bridging the gap between my experience and someone else’s, at least help us understand each other a little better.

Get Out opens in theaters on February 24.

Most Popular

Why are whole-body deodorants suddenly everywhere, if trump wins, what would hold him back, take a mental break with the newest vox crossword, what the death of iran’s president could mean for its future, the known unknowns about ozempic, explained, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Awards Shows

No, the director of Zone of Interest did not disavow his Jewish identity at the Oscars

I’m an expert in the end of the world. The Oscar-winning Oppenheimer made me cry in terror.

7 winners and 0 losers from the surprisingly delightful 2024 Oscars

The profound weirdness of Robert Downey Jr.’s Oscar win — and the category he won

What does winning an Oscar even mean anyway?

No one wants an Oscar as badly as Bradley Cooper

Bridgerton’s third season is more diverse — and even shallower — than ever

The misleading, wasteful way we measure gas mileage, explained

The Republican Party's man inside the Supreme Court

Why Trump's running mate could be the most important VP pick of our time

Rent control for child care?

Introducing Vox’s next chapter

Pioneering the Future of AI-Enhanced Storytelling

Breaking structure creates tremendous shock value-while maintaining the integrity of the message.

Jordan Peele’s directorial debut Get Out succeeds on many levels. On the surface, the literal interpretation of this imperative commands us to high-tail it out of there and escape the horrors of an upstate New York estate. Underneath, the psychological implications of the narrative implore us to get out of our heads and stop focusing on keeping the peace to avoid further conflict. The former fulfills the prerequisites of a great horror film, the latter guarantees a long and lasting impression.

Achieving a 99% rating on Rotten Tomatoes is rare, yet predictable. Get Out grabs this honor not through style nor shock factor, but rather through an efficient and sophisticated narrative structure–a repeatable approach brought about by a solid Storyform.

A comprehensive and functioning storyform guarantees critical acclaim and widespread Audience approval.

How then does one explain the success of Get Out given that its director purposefully broke the storyform to assuage racial tension?

Deliver 98% of the message, and the Audience will finish the rest for you.

A Brilliant Combination of Both Objective and Subjective Views

Get Out tells the story of photographer Chris Washington (Daniel Kaluuya) and his weekend spent meeting the mother and father of his girlfriend, Rose Armitage (Allison Williams) at her parent’s estate in upstate New York. Strange encounters with groundskeeper Walter (Marcus Henderson) and maid Georgina (Betty Gabriel) unlock an elaborate scheme of therapeutic hypnosis and brain surgery designed to prolong the lives of weak white people. Manipulating black victims into the “sunken place” to prepare them for transfer centralizes conflict in the Psychology Domain for the Objective Story Throughline with an emphasis, or Objective Story Concern in Conceptualizing .

Dark and foreboding Psychological Dramas like What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? , Sunset Boulevard and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf share this common source of conflict in Psychology and Conceptualizing, placing Get Out in good company.

While the Armitage family works to balance the intellectual superiority of white people with the physical advantages of the black community, Chris holds himself back–participating in the modern tradition of African-Americans to blame a lack of agency on a system that just isn’t fair. Agreeing to produce a State I.D. when it isn’t warranted, merely for the sake of keeping the peace? Chris, like so many men and women in his position, fails to take action because of a Problem with Equity .

The Dramatica theory of story defines a Motivation of Equity as a balance, fairness, or stability . This effort to maintain balance because “shit isn’t fair” holds people back from solving personal problems. Sometimes–as Chris later learns–a little inequity is needed to move things forward. This drive towards Equity also reduces capable and productive members of society to sniveling and affable slaves, happy to keep peace with their masters at any cost–even if it means forgetting their true selves (a Story Cost of Memory ).

The genius of Get Out lies in the connection between Chris’s issues and the issues suffered by the rest of the cast at the hands of the Armitage family. Both the Main Character Problem and Objective Story Problem share a similar focus on Equity.

The Meaningful Character Arc

When first introduced to the subtle racism of Rose’s family, Chris steps back and adapts–changing himself and accepting what he sees rather than doing anything to improve the situation. This mindset, that balance must be maintained, defines the nature of problems found in a Main Character Throughline of in Mind and sets a Main Character Approach of Be-er .

The Dramatica theory of story singles out two key story points to define the Character Arc of the Main Character: the Main Character Resolve and the Main Character Growth . The Resolve compares the end of the narrative to the beginning and asks Did the Main Character abandon an old paradigm, or did they remain steadfast to their original approach? The Growth determines the direction of movement–either away from their initial perspective or towards a new approach.

In Get Out , Chris exemplifies all the qualities of a Main Character with a Changed Resolve and a Growth of Stop . Chris is his own worst enemy–he needs to Stop thinking that his failure to act the night of his mother’s death resulted in some horrible karmic fate.

Chris’ initial therapy session with Mrs. Armitage explains the source of this justification and his Main Character Issue with Falsehood :

You said 'you knew something was wrong.' What did you do?

I just sat there. Watching TV.

You didn't call someone? Your Aunt or the police?

I don't know. I thought if I did, it would make it real.

This lie, or Falsehood, Chris told himself led to his mother’s death and generated the guilt he feels in regards to her passing.

The Solution for Chris is to remove this idea of “life isn’t fair” from the conversation with others and instead, use it to get out from under his justifications. He Changes by accepting that sometimes, accidents happen. Exiting the car to retrieve the fallen Georgina confirms this shift.

Unfortunately, by removing it from the broader perspective he allows justice and Equity to overwhelm the balance of conflict in the Objective Story Throughline. His actions–from bocce ball to stranglehold–fight fire with fire, confirming white America’s concept of the modern black man and the hidden racism underneath.

He rises to meet his fate on that windy road–

–only to find his best friend Rod (LilRel Howery) behind the flashing blue and red lights–

–not local authorities, as was originally shot and written .

The result is a defective Storyform and a strange cognitive dissonance that accompanies events incongruent with the story’s established purpose.

The Alternate Ending of Get Out

During an interview on the BuzzFeed podcast Another Round, writer-director Jordan Peele explained the original ending for the film:

There is an alternate ending in which the cops come at the end. He gets locked up and taken away for slaughtering an entire family of white people and you know he’s never going to get out if he doesn’t get shot there on the spot.

This original ending fulfills the promise and intent of the narrative established in the Storyform throughout the rest of the film. Regardless of the social implications, the original intent behind the story flows concludes accurately with this alternate ending.

“we’re in this post racial world, apparently...we’ve got Obama so racism is over, let’s not talk about it. That’s what the movie was meant to address...if you don’t already know...racism isn’t over...the ending in that era was to say, look ‘You think race isn’t an issue? Well at the end, we all know this is how this movie would end right here.’”

Especially since everything that came before it was meant to support and argue that particular point-of-view. The idea that “racism is over” aligns with the Objective Story Problem of Equity –everyone thinks there is peace, when really, there isn’t–and that’s a problem.

This observation was Peele’s original intent for writing the story, and it shows with the progression of events and justifications present in each Throughline.

The Storyform contains the message of the Author’s original Intent. This dissonance between the original ending and the socially acceptable ending perfectly illustrates the mechanism underlying a functioning narrative.

Plot Progressions and Meaning

Unlike other paradigms of story structure, the order of events in the Dramatica theory of story holds a specific meaning. In Snyder’s Save the Cat! series, beats, and sequences often fall out of place and line up in a different order depending on the film. Variations of the Hero’s Journey tend to play fast and loose with order as well. With Dramatica, order is everything .

Dialing in the Storypoints presented within the first 90 minutes–yet, leaving out these last few minutes–one is presented with two possible storyforms for Get Out :

- SUCCESS : Conceiving - Being - Becoming - Conceptualizing

- FAILURE : Conceptualizing - Conceiving - Being - Becoming

Note: These Plot Progression are based on the Subtxt Narrative Engine March 2021, revision C. They differ significantly from the Progressions found in the original Dramatica application. While unknown to me when I had originally written this article (2017), the Progression predicted by Subtxt in 2021c synced up perfectly with my original thinking.

The Plot Progression of Get Out follows the second sequence–and aligns with Peele’s original intent. The first Act finds Chris trying to fit in with Rose's family, while Mr. and Mrs. Armitage set the stage for roping the young man into their diabolical scheme ( Objective Story Transit 1 of Conceptualizing ). The second Act finds best friend and TSA agent Rod coming up with ideas about white people hypnotizing black men to use as sex slaves, while Chris starts to get the idea that there is something strange going on with cellphone ( Objective Story Transit 2 of Conceiving ).

Andre Hayworth’s plea for Chris to “Get Out!” breaks the narrative in half and sets the pace for the downhill run.

Chris plays along as best he can as he tries to find a way out, while the Armitages keep up their charade of just being normal, friendly people--all the while closing in on him ( Objective Story Transit 3 of Being ). And finally, the fourth Act finds Chris transforming into the violent black man everyone assumes him to be, locking in the final Objective Story Transit 4 of Becoming .

Peele originally wrote a Story Outcome of Failure . And this narrative structure explains why we fully expect the doors to open and local authorities to emerge with guns drawn. Everything that led up to this moment required this ending to make sense of the narrative.

Seeing the bloodied and battered bodies of hopeless white people at the hands of a brutal and savage black person confirms what white America has always known–“Well, that’s just the way they are.” A mis -Understanding that finds its place within the storyform under the Story Consequence .

The alternate ending, available on both the DVD and iTunes Extras, extends this Understanding to Chris himself. Facing a Rod still intent on putting the pieces together, Chris tell him to back off–he understands that he’ll never get justice, but he doesn’t care–

–he beat them and more importantly, he beat the inner demons within himself.

The Story of Virtue

The narrative concept of the Story Judgment asks Did the efforts to resolve the story's inequity (centered in the Main Character) result in a relief of angst? Did they overcome their issues? If they did, the Story Judgment is said to be Good ; if not, the Story Judgment is Bad . In both the original and alternate endings, Chris overcame his problems by stopping the car and retrieving Georgina.

When you combine a Story Outcome of Failure with a Story Judgment of Good, you create a Virtuous Ending story. This ending is what Peele initially set out to create–yet failed to follow through with in the final film.

Considering the Audience’s Reception of a Story

The fourth and final stage of communicating story from Author to Audience receives little attention from Dramatica or Narrative First. No less important than the first three, this stage known as [ Story Reception ][54] finds extensive coverage in numerous other sources too exhaustive to list.

Still, some subtle and sophisticated techniques of Reception find genesis within the first three stages of Storyforming , StoryEncoding , and Storyweaving –namely, the breaking of the storyform.

[Director] Peele noticed people were getting more upset and angrier with the deaths of black men like Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, and he wanted to position the ending with Chris as a hero rather than a victim.

Peele plays against the expected Story Outcome of Failure by allowing Rod to put the pieces together and arrive at a Story Outcome of Success . In this way, the director works against Audience expectation by breaking the intended message. By sharing the same storymind Peele created throughout the entire message, the Audience expects Chris to land in jail–

–and applauds with exultation and applause when the film introduces a little inequity into their cinematic experience.

Giving Them What They Deserve

Understanding the key story points of a narrative makes it possible for an Author to play against Audience expectation and deliver something quite remarkable. By manipulating the Audience into expecting one outcome and providing another, writer/director Peele breaks structure to his–and our–advantage.

In some ways, this Inequity coincides with the storyform by giving us a clue as to how to put the pieces together towards a new concept of relating to one another. Instead of only showing us the current state of affairs and yet another account of a small and personal triumph, Peele offers us a vision of a way out...

..the triumph of the unimaginable.

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero .

- University Statistics

- University Leadership

- Events & Venues

- University Strategic Plan

- Bethlehem & the Lehigh Valley

- Maps & Directions

- Diversity, Inclusion & Equity

- COVID-19 Information Center

- Undergraduate Studies

- Majors & Undergraduate Programs

- Graduate Studies

- Interdisciplinary Studies

- Entrepreneurship and Innovation

- Creative Inquiry

- Continuing Education

- Provost & Academic Affairs

- International

- University Catalog

- Summer Programs

Our Colleges:

- College of Arts and Sciences

- College of Business

- College of Education

- College of Health

- P.C. Rossin College of Engineering and Applied Science

- Research Centers & Institutes

- Student Research Experience

- Office of Research

- Graduate Education & Life

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Apply to Lehigh

- Visits & Tours

- Tuition, Aid & Affording College

- Admission Statistics

- Majors & Programs

- Academics at Lehigh

- Student Life at Lehigh

- Student Profiles

- Success After Graduation

- Lehigh Launch

- Contact Us & Admissions Counselors

Information for:

- Transfer Students

- International Students

- School Counselors

- Graduate Admissions

Student Life

- Clubs & Organizations

- Housing & Dining

- Student Health & Campus Safety

- Arts & Athletics

- Advocacy Centers

- Student Support & Transition to College

- Prospective Student Athletes

- Radio & TV Broadcasts

- Camps & Clinics

- Venues & Directions

- Campus Athletics

- GO Beyond: The Campaign for Future Makers

- Ways to Give

- Students, Faculty & Staff

The Monster is Us: Jordan Peele’s 'Get Out' Exposes Society’s Horrors

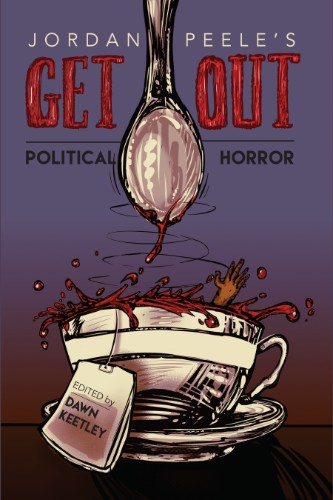

New essay collection edited by Dawn Keetley explores how the film ‘Get Out’ revolutionizes the horror tradition while unmasking the politics of race in the early 21st century United States.

Lori Friedman

- Dawn Keetley

As a horror film, Jordan Peele’s 2017 film Get Out certainly broke new ground. Yet, the film is firmly rooted in what Dawn Keetley refers to as “...the longstanding tradition of the political horror film” which is “...driven by very human monsters.”

Keetley, a scholar who specializes in Film, Television, and gothic and horror among other areas, edited a recently published collection of 16 essays about the critically-acclaimed film. The book, “ Jordan Peele’s Get Out: Political Horror ,” is the first scholarly publication to examine the film, which grossed $255 million worldwide, was nominated for four Academy Awards and won the award for Best Original Screenplay.

In the film, Chris Washington, a young Black man living in Brooklyn, gets lured into a fatal scheme by his White girlfriend, Rose Armitage, and her monied, liberal family while visiting them in upstate New York: “The off-putting family visit immerses Chris in a world of microaggressions that get progressively more unnerving, even sinister, culminating in the terrifying moment when he realizes he has been seduced into a deadly trap. Knocked unconscious, Chris wakes up in the family’s basement strapped to a chair and watching a video that tells him he will be undergoing an operation, the Coagula procedure, that will transplant a white man’s brain into his head,” writes Keetley.

Keetley places Get Out in the political horror tradition while noting its contribution to the genre: “Since I’m an avid horror film fan, it was particularly important to me to take up Get Out within the horror tradition―something Peele himself certainly did and has spoken about,” says Keetley. “As much as Get Out emerged from horror films of the past, it also grew from the politics of the present, and so the second major aim of this collection was to read Get Out within the racial politics of its historical moment, although this moment was also, of course, rooted in the racial politics of the past—in slavery, Reconstruction and Jim Crow.”

She writes that in interviews about Get Out, Peele “...has self-consciously chosen to designate it a ‘social thriller’―a film, as Peele describes it, in which the ‘monster’ is society itself.” She notes how he has explicitly cited the influence of three films in particular: Night of the Living Dead, Rosemary’s Baby and The Stepford Wives . Peele draws on these films to: “...unequivocally indict white people in the same way that The Stepford Wives controversially indicted men,” writes Keetley.

In her introduction, Keetley also explores such topics as how Get Out utilizes the tradition of body horror to address the ongoing legacy of U.S. slavery; how blackface imagery is used in the film to “...expose the false allyship of progressive whites”; and, how the horror trope of the brain transplant is used to illustrate the persistence of racism. Keetley writes: “Racial identity and racism, Get Out proposes, are not easily dislodged―remaining mired in flesh and blood, entrenched in the very substance of the brain.”

The Politics of Horror

The collection is grouped into two sections ― Part I: The Politics of Horror and Part II: The Horror of Politics. The topics in the first section range from the appearance of zombies in Get Out to how it fits into horror’s “minority vocabulary” to the movie’s place in the Female Gothic tradition.

“What most surprised me about the essays in this collection as they came in was how diverse the readings of Get Out were,” says Keetley. “Contributors took up similar scenes and read them in different ways, in different contexts. Editing these essays gave me a vastly renewed appreciation of Peele’s genius in creating this film—a film that has so many layers, so many resonant details. Each scene, each object in a shot, has meaning, often multiple meanings.”

In “A Peaceful Place Denied,” Robin R. Means Coleman , professor and vice president and associate provost for diversity at Texas A&M and Novotny Lawrence , associate professor at Iowa State University, trace the history of “Whitopia” in the horror genre, a term they attribute to Rich Benjamin and define as communities that “remain willfully less multicultural.”

“Within the horror genre, films advanced storylines of White preservation through segregation as Whites and even White monsters fled to Whitopias (e.g. A Nightmare on Elm Street , 1984), thereby freeing themselves from the dangers of the urban,” write Means Coleman and Lawrence. “All this racialized spatial angst finds its origins in D. W. Griffith’s 1915 horror film (yes, it is a horror film) The Birth of a Nation . Nation has fueled White racism for over a century by depicting northern Blacks (portrayed by Whites in blackface) as trampling upon and destroying Whites’ Southern homeland and cultural traditions.”

Means Coleman and Lawrence detail a “cinematic intervention” in the 1970s “that cut against stereotyped notions of Black communities as monstrous” with the advent of Black Exploitation (Blaxploitation) films centering Black heroes and experiences. They also recount the dominant narrative of the 1980s when, as explained by scholar Adilifu Nama, “...the urban became Reagan-era political shorthand for all manner of social ills that people of color were held accountable for, such as crime, illegal drugs, poverty and fractured families.”

The opening scene of Get Out , they write, sets the stage for an inversion of the notion of White suburbia as an oasis in contrast to threatening Black urban environments. “ Get Out begins with Andre Haworth, outside his Black urban home of Brooklyn, talking to a friend on his mobile phone while walking through an unspecified neighborhood, or perhaps more appropriately, any Whitopia, USA.”

When Andre is grabbed, drugged and thrown into the trunk of a car by a masked man, the reversal is clear, they write: “The scene is disturbing as it brings the threat posed to Black urbanites to fruition, instantly constructing the well-manicured, sterile Whitopia as monstrous.”

The Horror of Politics

Topics in “The Horror of Politics” section include the construction of Black male identity in the White imagination and how historical slave resistance informs the film. An essay by a recent Lehigh graduate student Cayla McNally called “Scientific Racism and the Politics of Looking” traces the dark history of racism in science and medicine, arguing that the latter’s “dispassionate prejudice” has been “a mainstay of white supremacy since the founding of the United States.” Chris, though, is able to level his own gaze, through his camera lens, at the scientific system that wants to co-opt his body in the name of science.

In his essay “Staying Woke in Sunken Places, Or the Wages of Double Consciousness,” Mikal J. Gaines , assistant professor of English at Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, finds an “ideological affinity” between certain themes in Get Out and W.E.B. Du Bois’s theory of “double consciousness.”

Gaines writes: “Du Bois sought to articulate how being black in America brings about an internal cracking open of the self, a split that ironically renders it impossible to separate questions of subjectivity (one’s internal sense of being in relation to the rest of the world) from those of identity (externally imposed and systematically enforced categories of difference.)”

As part of the Coagula trap, Rose’s mother Missy Armitage hypnotizes Chris, imprisoning his consciousness in a psychic no-man’s land dubbed “the sunken place.” “The visualization of ‘the sunken place’ in particular shares an intellectual and conceptual kinship with Du Bois’s hypothesis,” writes Gaines. The sunken place “literalizes the paralysis that accompanies being forced to occupy a splintered sense of self as a principle condition of life.”

While Get Out , as Keetley notes, “emerged from the politics of the present,” the film transcends it to wrestle with larger questions. As Peele himself has said: “The best and scariest monsters in the world are human beings and what we are capable of especially when we get together.”

Related Stories

Nursing Home Industry May Obscure Some of its Profits, Lehigh Researcher Finds

Andrew Olenski, assistant professor of economics, publishes finding in a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper.

Research Promotes Equitable Reclassification for Multilingual Learners with Disabilities