Writers' Treasure

Effective writing advice for aspiring writers

Creative Writing 101

Creative writing is any form of writing which is written with the creativity of mind: fiction writing, poetry writing, creative nonfiction writing and more. The purpose is to express something, whether it be feelings, thoughts, or emotions.

Rather than only giving information or inciting the reader to make an action beneficial to the writer, creative writing is written to entertain or educate someone, to spread awareness about something or someone, or to express one’s thoughts.

There are two kinds of creative writing: good and bad, effective and ineffective. Bad, ineffective creative writing cannot make any impression on the reader. It won’t achieve its purpose.

So whether you’re a novelist, a poet, a short-story writer, an essayist, a biographer or an aspiring beginner, you want to improve your craft. The question is: how?

When you write great fiction, poetry, or nonfiction, amazing things can happen. Readers can’t put it down. The work you wrote becomes a bestseller. It becomes famous. But you have to reach to that level… first .

The best way to increase your proficiency in creative writing is to write, write compulsively, but it doesn’t mean write whatever you want. There are certain things you should know first… it helps to start with the right foot.

To do exactly that, here we have a beginners’ guide from Writers’ Treasure on the subject:

- An Introduction to Creative Writing

- How to Get Started in Creative Writing in Just Three Steps

- Creative Writing vs. Technical Writing

- Fiction Writing 101: The Elements of Stories

- Poetry Writing: Forms and Terms Galore

- Creative Non-Fiction: What is it?

- Tips and Tricks to Improve Your Creative Writing

- Common Mistakes Made by Creative Writers

For novelists: do you want to write compelling opening chapters?

Are you an aspiring novelist? Will your novel see the light of day? For that, you will need to make the first chapter of your story as compelling as possible. Otherwise, readers won’t even pick up your novel. That chapter can be the make-or-break point that decides whether your novel is published or not. It’s because good editors know how you write from the first three pages… or sometimes even from the opening lines.

To solve this problem, I created a five-part tutorial on Writing Compelling Opening Chapters . It outlines why you need to write a compelling opening chapter, my personal favourite way of beginning it, what should be told and shown in it, general dos and don’ts, and what you need to do after having written it. Check it out for more.

Need more writing tips?

Sometimes you reach that stage when you outgrow the beginner stage of writing but feel that you’re not yet an expert. If I just described you, no worries– Writers’ Treasure’s writing tips are here. Whether you want to make your writing more readable, more irresistible, more professional, we’ve got you covered. So check out our writing tips , and be on your way to fast track your success.

I offer writing, editing and proofreading , as well as website creation services. I’ve been in this field for seven years, and I know the tools of the trade. I’ve seen the directions where the writing industry is going, the changes, the new platforms. Get your work done through me, and get fast and efficient service. Get a quote .

Free updates

Get free updates from Writers’ Treasure and learn more tips and tricks to improve your writing.

Share this:

52 thoughts on “creative writing 101”.

- Pingback: Creative Non-Fiction: What is it? | Writers Treasure

- Pingback: Poetry Writing Forms and Terms | Writers Treasure

- Pingback: Fiction Writing Tips and Elements to focus on | Writers Treasure

- Pingback: Creative Writing vs. Technical Writing | Writers Treasure

- Pingback: How to Get Started in Creative Writing | Writers Treasure

- Pingback: An Introduction to Creative Writing | Writers Treasure

- Pingback: How to Improve Your Creative Writing | Writers Treasure

- Pingback: Common Mistakes Made by Creative Writers | Writers Treasure

- Pingback: To Outline or Not to Outline, That is the Question

- Pingback: How to Create Effective Scenes and Chapters in Your Novel : Writing Forward

- Pingback: Writing Powerful True Short Stories

- Pingback: POV: What it is and how it matters

- Pingback: Creative Writing Skills: Do You Have Them All?

- Pingback: Three great articles check out on the Writers Treasure - Jamie Folsom

- Pingback: Warning: Do You Know that Your Paragraphs are Not Good Enough?

- Pingback: Welcome to Writers Treasure

- Pingback: How to Create Effective Scenes and Chapters in Your Novel

- Pingback: Adding Humour to Creative Write-up: Tips and Tricks

- Pingback: Creative Writing vs. Resume Writing | Resume Matrix

- Pingback: How to Get Started in Creative Writing in Just Three Steps | Blog do Learning

- Pingback: The #1 writing advice: write the truth

- Pingback: Creative writing in 2015: here’s what you need to know

- Pingback: Creative Writing Can Be Practical Writing - Simple Writer

- Pingback: Freedom Friday: Liberating Your Creativity | Renee "Soul Writer" Brooks

- Pingback: Tips to help you become a good copywriter | The Creative Copywriter.

- Pingback: Creative Writing | Shahad Almarzooq

- Pingback: How to be good at creative writing?

- Pingback: Learn creative writing

- Pingback: Creative Writing - Occident Books

- Pingback: How to become an outstanding writer

- Pingback: 5 creative writing tips to help you write great essays! – Essay Writing Tips and Help

- Pingback: Creative Writing Tips | learningland2016

- Pingback: NELTA ELT Forum

- Pingback: Language, Communication and Creativity. – lookinglanguage

- Pingback: Keep Your Kids Learning Even When School Year Is Over | Severna Park Children's Centre, Inc

- Pingback: 10 Free Online Courses on Creative Writing » A guide to free online courses

- Pingback: How to start a successful Blog – Beginner’s Guide for 2016

- Pingback: How to start a successful Blog – Beginner’s Guide for 2017

- Pingback: Best of English classes | Site Title

- Pingback: English Classes,Which Classes Dominate others? – Pressing Times

- Pingback: Creative Writing 101 | Junctionway

- Pingback: How to Write Quality Articles: A New Guide for Online Startups [Part Two: 3 Simple Ways for Finding Ideas] - Suhaib Mohammed

- Pingback: Writing Blogs in the Shower - Say It For You- Say It For You

- Pingback: 5 Ways To Improve Your Health First In The New Year - Sarah Scoop

- Pingback: 10 Hobbies Your Teen Can Get as an Alternative to Digital Devices While on Lockdown | meekscutoff.com

- Pingback: 50+ Easy Fiverr Freelance Jobs Examples to Start Today! | IsuaWealthyPlace

- Pingback: 10 Creative Writing Strategies In The Composition Classroom - Wizpals

- Pingback: 5 Ways to Become the MacGyver of Creative Writing

- Pingback: Balancing Your Life As A Writer And Head Of The Family - ebookomatic.com

- Pingback: EbookoMatic | Ricos Electronic World

- Pingback: 20 Types of Freelance Writing Careers (The Definitive List)

- Pingback: Welcome to Musings & Meanderings: A Journey Through Poetry and Prose - Musings & Meanderings

Comments are closed.

What Is Creative Writing? (Ultimate Guide + 20 Examples)

Creative writing begins with a blank page and the courage to fill it with the stories only you can tell.

I face this intimidating blank page daily–and I have for the better part of 20+ years.

In this guide, you’ll learn all the ins and outs of creative writing with tons of examples.

What Is Creative Writing (Long Description)?

Creative Writing is the art of using words to express ideas and emotions in imaginative ways. It encompasses various forms including novels, poetry, and plays, focusing on narrative craft, character development, and the use of literary tropes.

Table of Contents

Let’s expand on that definition a bit.

Creative writing is an art form that transcends traditional literature boundaries.

It includes professional, journalistic, academic, and technical writing. This type of writing emphasizes narrative craft, character development, and literary tropes. It also explores poetry and poetics traditions.

In essence, creative writing lets you express ideas and emotions uniquely and imaginatively.

It’s about the freedom to invent worlds, characters, and stories. These creations evoke a spectrum of emotions in readers.

Creative writing covers fiction, poetry, and everything in between.

It allows writers to express inner thoughts and feelings. Often, it reflects human experiences through a fabricated lens.

Types of Creative Writing

There are many types of creative writing that we need to explain.

Some of the most common types:

- Short stories

- Screenplays

- Flash fiction

- Creative Nonfiction

Short Stories (The Brief Escape)

Short stories are like narrative treasures.

They are compact but impactful, telling a full story within a limited word count. These tales often focus on a single character or a crucial moment.

Short stories are known for their brevity.

They deliver emotion and insight in a concise yet powerful package. This format is ideal for exploring diverse genres, themes, and characters. It leaves a lasting impression on readers.

Example: Emma discovers an old photo of her smiling grandmother. It’s a rarity. Through flashbacks, Emma learns about her grandmother’s wartime love story. She comes to understand her grandmother’s resilience and the value of joy.

Novels (The Long Journey)

Novels are extensive explorations of character, plot, and setting.

They span thousands of words, giving writers the space to create entire worlds. Novels can weave complex stories across various themes and timelines.

The length of a novel allows for deep narrative and character development.

Readers get an immersive experience.

Example: Across the Divide tells of two siblings separated in childhood. They grow up in different cultures. Their reunion highlights the strength of family bonds, despite distance and differences.

Poetry (The Soul’s Language)

Poetry expresses ideas and emotions through rhythm, sound, and word beauty.

It distills emotions and thoughts into verses. Poetry often uses metaphors, similes, and figurative language to reach the reader’s heart and mind.

Poetry ranges from structured forms, like sonnets, to free verse.

The latter breaks away from traditional formats for more expressive thought.

Example: Whispers of Dawn is a poem collection capturing morning’s quiet moments. “First Light” personifies dawn as a painter. It brings colors of hope and renewal to the world.

Plays (The Dramatic Dialogue)

Plays are meant for performance. They bring characters and conflicts to life through dialogue and action.

This format uniquely explores human relationships and societal issues.

Playwrights face the challenge of conveying setting, emotion, and plot through dialogue and directions.

Example: Echoes of Tomorrow is set in a dystopian future. Memories can be bought and sold. It follows siblings on a quest to retrieve their stolen memories. They learn the cost of living in a world where the past has a price.

Screenplays (Cinema’s Blueprint)

Screenplays outline narratives for films and TV shows.

They require an understanding of visual storytelling, pacing, and dialogue. Screenplays must fit film production constraints.

Example: The Last Light is a screenplay for a sci-fi film. Humanity’s survivors on a dying Earth seek a new planet. The story focuses on spacecraft Argo’s crew as they face mission challenges and internal dynamics.

Memoirs (The Personal Journey)

Memoirs provide insight into an author’s life, focusing on personal experiences and emotional journeys.

They differ from autobiographies by concentrating on specific themes or events.

Memoirs invite readers into the author’s world.

They share lessons learned and hardships overcome.

Example: Under the Mango Tree is a memoir by Maria Gomez. It shares her childhood memories in rural Colombia. The mango tree in their yard symbolizes home, growth, and nostalgia. Maria reflects on her journey to a new life in America.

Flash Fiction (The Quick Twist)

Flash fiction tells stories in under 1,000 words.

It’s about crafting compelling narratives concisely. Each word in flash fiction must count, often leading to a twist.

This format captures life’s vivid moments, delivering quick, impactful insights.

Example: The Last Message features an astronaut’s final Earth message as her spacecraft drifts away. In 500 words, it explores isolation, hope, and the desire to connect against all odds.

Creative Nonfiction (The Factual Tale)

Creative nonfiction combines factual accuracy with creative storytelling.

This genre covers real events, people, and places with a twist. It uses descriptive language and narrative arcs to make true stories engaging.

Creative nonfiction includes biographies, essays, and travelogues.

Example: Echoes of Everest follows the author’s Mount Everest climb. It mixes factual details with personal reflections and the history of past climbers. The narrative captures the climb’s beauty and challenges, offering an immersive experience.

Fantasy (The World Beyond)

Fantasy transports readers to magical and mythical worlds.

It explores themes like good vs. evil and heroism in unreal settings. Fantasy requires careful world-building to create believable yet fantastic realms.

Example: The Crystal of Azmar tells of a young girl destined to save her world from darkness. She learns she’s the last sorceress in a forgotten lineage. Her journey involves mastering powers, forming alliances, and uncovering ancient kingdom myths.

Science Fiction (The Future Imagined)

Science fiction delves into futuristic and scientific themes.

It questions the impact of advancements on society and individuals.

Science fiction ranges from speculative to hard sci-fi, focusing on plausible futures.

Example: When the Stars Whisper is set in a future where humanity communicates with distant galaxies. It centers on a scientist who finds an alien message. This discovery prompts a deep look at humanity’s universe role and interstellar communication.

Watch this great video that explores the question, “What is creative writing?” and “How to get started?”:

What Are the 5 Cs of Creative Writing?

The 5 Cs of creative writing are fundamental pillars.

They guide writers to produce compelling and impactful work. These principles—Clarity, Coherence, Conciseness, Creativity, and Consistency—help craft stories that engage and entertain.

They also resonate deeply with readers. Let’s explore each of these critical components.

Clarity makes your writing understandable and accessible.

It involves choosing the right words and constructing clear sentences. Your narrative should be easy to follow.

In creative writing, clarity means conveying complex ideas in a digestible and enjoyable way.

Coherence ensures your writing flows logically.

It’s crucial for maintaining the reader’s interest. Characters should develop believably, and plots should progress logically. This makes the narrative feel cohesive.

Conciseness

Conciseness is about expressing ideas succinctly.

It’s being economical with words and avoiding redundancy. This principle helps maintain pace and tension, engaging readers throughout the story.

Creativity is the heart of creative writing.

It allows writers to invent new worlds and create memorable characters. Creativity involves originality and imagination. It’s seeing the world in unique ways and sharing that vision.

Consistency

Consistency maintains a uniform tone, style, and voice.

It means being faithful to the world you’ve created. Characters should act true to their development. This builds trust with readers, making your story immersive and believable.

Is Creative Writing Easy?

Creative writing is both rewarding and challenging.

Crafting stories from your imagination involves more than just words on a page. It requires discipline and a deep understanding of language and narrative structure.

Exploring complex characters and themes is also key.

Refining and revising your work is crucial for developing your voice.

The ease of creative writing varies. Some find the freedom of expression liberating.

Others struggle with writer’s block or plot development challenges. However, practice and feedback make creative writing more fulfilling.

What Does a Creative Writer Do?

A creative writer weaves narratives that entertain, enlighten, and inspire.

Writers explore both the world they create and the emotions they wish to evoke. Their tasks are diverse, involving more than just writing.

Creative writers develop ideas, research, and plan their stories.

They create characters and outline plots with attention to detail. Drafting and revising their work is a significant part of their process. They strive for the 5 Cs of compelling writing.

Writers engage with the literary community, seeking feedback and participating in workshops.

They may navigate the publishing world with agents and editors.

Creative writers are storytellers, craftsmen, and artists. They bring narratives to life, enriching our lives and expanding our imaginations.

How to Get Started With Creative Writing?

Embarking on a creative writing journey can feel like standing at the edge of a vast and mysterious forest.

The path is not always clear, but the adventure is calling.

Here’s how to take your first steps into the world of creative writing:

- Find a time of day when your mind is most alert and creative.

- Create a comfortable writing space free from distractions.

- Use prompts to spark your imagination. They can be as simple as a word, a phrase, or an image.

- Try writing for 15-20 minutes on a prompt without editing yourself. Let the ideas flow freely.

- Reading is fuel for your writing. Explore various genres and styles.

- Pay attention to how your favorite authors construct their sentences, develop characters, and build their worlds.

- Don’t pressure yourself to write a novel right away. Begin with short stories or poems.

- Small projects can help you hone your skills and boost your confidence.

- Look for writing groups in your area or online. These communities offer support, feedback, and motivation.

- Participating in workshops or classes can also provide valuable insights into your writing.

- Understand that your first draft is just the beginning. Revising your work is where the real magic happens.

- Be open to feedback and willing to rework your pieces.

- Carry a notebook or digital recorder to jot down ideas, observations, and snippets of conversations.

- These notes can be gold mines for future writing projects.

Final Thoughts: What Is Creative Writing?

Creative writing is an invitation to explore the unknown, to give voice to the silenced, and to celebrate the human spirit in all its forms.

Check out these creative writing tools (that I highly recommend):

Read This Next:

- What Is a Prompt in Writing? (Ultimate Guide + 200 Examples)

- What Is A Personal Account In Writing? (47 Examples)

- How To Write A Fantasy Short Story (Ultimate Guide + Examples)

- How To Write A Fantasy Romance Novel [21 Tips + Examples)

Creative Writing 101

You love to write and have been told you have a way with words. So you’ve decided to give writing a try—creative writing.

Problem is, you’re finding it tougher than it looks.

You may even have a great story idea , but you’re not sure how to turn it into something people will read.

Don’t be discouraged—writing a compelling story can be grueling, even for veterans. Conflicting advice online may confuse you and make you want to quit before you start.

But you know more than you think. Stories saturate our lives.

We tell and hear stories every day in music, on television, in video games, in books, in movies, even in relationships.

Most stories, regardless the genre, feature a main character who wants something.

There’s a need, a goal, some sort of effort to get that something.

The character begins an adventure, a journey, or a quest, faces obstacles, and is ultimately transformed.

The work of developing such a story will come. But first, let’s look at the basics.

- What is Creative Writing?

It’s prose (fiction or nonfiction) that tells a story.

Journalistic, academic, technical writing relays facts.

Creative writing can also educate, but it’s best when it also entertains and emotionally moves the reader.

It triggers the imagination and appeals to the heart.

- Elements of Creative Writing

Writing a story is much like building a house.

You may have all the right tools and design ideas, but if your foundation isn’t solid, even the most beautiful structure won’t stand.

Most storytelling experts agree, these 7 key elements must exist in a story.

Plot (more on that below) is what happens in a story. Theme is why it happens.

Before you begin writing, determine why you want to tell your story.

- What message do you wish to convey?

- What will it teach the reader?

Resist the urge to explicitly state your theme. Just tell the story, and let it make its own point.

Give your readers credit. Subtly weave your theme into the story and trust them to get it.

They may remember a great plot, but you want them thinking about your theme long after they’ve finished reading.

2. Characters

Every story needs believable characters who feel knowable.

In fiction, your main character is the protagonist, also known as the lead or hero/heroine.

The protagonist must have:

- redeemable flaws

- potentially heroic qualities that emerge in the climax

- a character arc (he must be different, better, stronger by the end)

Resist the temptation to create a perfect lead. Perfect is boring. (Even Indiana Jones suffered a snake phobia.)

You also need an antagonist, the villain , who should be every bit as formidable and compelling as your hero.

Don’t make your bad guy bad just because he’s the bad guy. Make him a worthy foe by giving him motives for his actions.

Villains don’t see themselves as bad. They think they’re right! A fully rounded bad guy is much more realistic and memorable.

Depending on the length of your story , you may also need important orbital cast members.

For each character, ask:

- What do they want?

- What or who is keeping them from getting it?

- What will they do about it?

The more challenges your characters face, the more relatable they are.

Much as in real life, the toughest challenges result in the most transformation.

Setting may include a location, time, or era, but it should also include how things look, smell, taste, feel, and sound.

Thoroughly research details about your setting so it informs your writing, but use those details as seasoning, not the main course. The main course is the story.

But, beware.

Agents and acquisitions editors tell me one of the biggest mistakes beginning writers make is feeling they must begin by describing the setting.

That’s important, don’t get me wrong. But a sure way to put readers to sleep is to promise a thrilling story on the cover—only to start with some variation of:

The house sat in a deep wood surrounded by…

Rather than describing your setting, subtly layer it into the story.

Show readers your setting. Don’t tell them. Description as a separate element slows your story to crawl.

By layering in what things look and feel and sound like you subtly register the setting in the theater of readers’ minds.

While they concentrating on the action, the dialogue , the tension , the drama, and conflict that keep them turning the pages, they’re also getting a look and feel for your setting.

4. Point of View

POV is more than which voice you choose to tell your story: First Person ( I, me ), Second Person ( you, your ), or Third Person ( he, she, or it ).

Determine your perspective (POV) character for each scene—the one who serves as your camera and recorder—by deciding who has the most at stake. Who’s story is this?

The cardinal rule is that you’re limited to one perspective character per scene, but I prefer only one per chapter, and ideally one per novel.

Readers experience everything in your story from this character’s perspective.

For a more in-depth explanation of Voice and POV, read A Writer’s Guide to Point of View .

This is the sequence of events that make up a story —in short, what happens. It either compels your reader to keep turning pages or set the book aside.

A successful story answers:

- What happens? (Plot)

- What does it mean? (Theme: see above)

Writing coaches call various story structures by different names, but they’re all largely similar. All such structures include some variation of:

- An Inciting Incident that changes everything

- A series of Crises that build tension

- A Resolution (or Conclusion)

How effectively you create drama, intrigue, conflict, and tension, determines whether you can grab readers from the start and keep them to the end.

6. Conflict

This is the engine of fiction and crucial to effective nonfiction as well.

Readers crave conflict and what results from it.

If everything in your plot is going well and everyone is agreeing, you’ll quickly bore your reader—the cardinal sin of writing.

If two characters are chatting amiably and the scene feels flat (which it will), inject conflict. Have one say something that makes the other storm out, revealing a deep-seated rift.

Readers will stay with you to find out what it’s all about.

7. Resolution

Whether you’re an Outliner or a Pantser like me (one who writes by the seat of your pants), you must have an idea where your story is going.

How you expect the story to end should inform every scene and chapter. It may change, evolve, and grow as you and your characters do, but never leave it to chance.

Keep your lead character center stage to the very end. Everything he learns through all the complications you plunged him into should, in the end, allow him to rise to the occasion and succeed.

If you get near the end and something’s missing, don’t rush it. Give your ending a few days, even a few weeks if necessary.

Read through everything you’ve written. Take a long walk. Think about it. Sleep on it. Jot notes. Let your subconscious work. Play what-if games. Reach for the heart, and deliver a satisfying ending that resonates .

Give your readers a payoff for their investment by making it unforgettable.

- Creative Writing Examples

- Short Story

- Narrative nonfiction

- Autobiography

- Song lyrics

- Screenwriting

- Playwriting

- Creative Writing Tips

In How to Write a Novel , I cover each step of the writing process:

- Come up with a great story idea .

- Determine whether you’re an Outliner or a Pantser.

- Create an unforgettable main character.

- Expand your idea into a plot.

- Do your research.

- Choose your Voice and Point of View.

- Start in medias res (in the midst of things).

- Intensify your main character’s problems.

- Make the predicament appear hopeless.

- Bring it all to a climax.

- Leave readers wholly satisfied.

- More to Think About

1. Carry a writing pad, electronic or otherwise. I like the famous Moleskine™ notebook .

Ideas can come at any moment. Record ideas for:

- Anything that might expand your story

2. Start small.

Take time to build your craft and hone your skills on smaller projects before you try to write a book .

Journal. Write a newsletter. Start a blog. Write short stories . Submit articles to magazines, newspapers, or e-zines.

Take a night school or online course in journalism or creative writing. Attend a writers conference.

3. Throw perfection to the wind.

Separate your writing from your editing .

Anytime you’re writing a first draft, take off your perfectionist cap. You can return to editor mode to your heart’s content while revising, but for now, just write the story.

Separate these tasks and watch your daily production soar.

- Time to Get to Work

Few pleasures in life compare to getting lost in a great story.

Learn how to write creatively, and the characters you birth have the potential to live in hearts for years.

- 1. Carry a writing pad, electronic or otherwise. I like the famous Moleskine™ notebook.

Are You Making This #1 Amateur Writing Mistake?

Faith-Based Words and Phrases

What You and I Can Learn From Patricia Raybon

Before you go, be sure to grab my FREE guide:

How to Write a Book: Everything You Need to Know in 20 Steps

Just tell me where to send it:

Enter your email to instantly access my ultimate guide:

How to write a novel: a 12-step guide.

- Creativity Techniques

26+ Creative Writing Tips for Young Writers

So you want to be a writer? And not just any writer, you want to be a creative writer. The road to being a legendary storyteller won’t be easy, but with our creative writing tips for kids, you’ll be on the right track! Creative writing isn’t just about writing stories. You could write poems, graphic novels, song lyrics and even movie scripts. But there is one thing you’ll need and that is good creative writing skills.

Here are over 26 tips to improve your creative writing skills :

Read a wide range of books

When it comes to creative writing, reading is essential. Reading allows you to explore the styles of other writers and gain inspiration to improve your own writing. But don’t just limit yourself to reading only popular books or your favourites. Read all sorts of books, everything from fairytales to scary stories. Take a look at comics, short stories, novels and poetry. Just fill your heads with the knowledge and wisdom of other writers and soon you’ll be just like them!

Write about real-life events

The hardest thing about creative writing is connecting emotionally with your audience. By focusing your writing on real-life events, you know that in some way or another your readers will be able to relate. And with creative writing you don’t need to use real names or details – There are certain things you can keep private while writing about the rare details. Using real-life events is also a good way to find inspiration for your stories.

Be imaginative

Be as crazy and wild as you like with your imagination. Create your world, your own monsters , or even your own language! The more imaginative your story, the more exciting it will be to read. Remember that there are no rules on what makes a good idea in creative writing. So don’t be afraid to make stuff up!

Find your writing style

Thes best writers have a particular style about them. When you think of Roald Dahl , you know his books are going to have a sense of humour. While with Dr Seuss , you’re prepared to read some funny new words . Alternatively, when you look at R.L.Stine, you know that he is all about the horror. Think about your own writing style. Do you want to be a horror writer? Maybe someone who always writes in the first person? Will always focus your books on your culture or a particular character?

Stick to a routine

Routine is extremely important to writers. If you just write some stuff here and there, it’s likely that you’ll soon give up on writing altogether! A strict routine means that every day at a certain time you will make time to write about something, anything. Even if you’re bored or can’t think of anything, you’ll still pick up that pencil and write. Soon enough you’ll get into the habit of writing good stuff daily and this is definitely important for anyone who wants to be a professional creative writer!

Know your audience

Writing isn’t just about thinking about your own interests, it’s also about thinking about the interests of your audience. If you want to excite fellow classmates, know what they like. Do they like football , monsters or a particular video game? With that knowledge, you can create the most popular book for your target audience. A book that they can’t stop reading and will recommend to others!

Daily Exercises

To keep your creative writing skills up to scratch it is important to keep practising every day. Even if you have no inspiration. At times when your mind is blank, you should try to use tools like writing prompts , video prompts or other ways of coming up with ideas . You could even take a look at these daily writing exercises as an example. We even created a whole list of over 100 creative writing exercises to try out when you need some inspiration or ideas.

Work together with others

Everyone needs a little help now and then. We recommend joining a writing club or finding other classmates who are also interested in writing to improve your own creative writing skills. Together you can share ideas, tips and even write a story together! A good storytelling game to play in a group is the “ finish the story” game .

Get feedback

Without feedback, you’ll never be able to improve your writing. Feedback, whether good or bad is important to all writers. Good feedback gives you the motivation to carry on. While bad feedback just gives you areas to improve and adapt your writing, so you can be the best! After every piece of writing always try to get feedback from it, whether it is from friends, family, teachers or an online writing community .

Enter writing competitions

The best way to improve your creative writing is by entering all sorts of writing competitions . Whether it’s a poetry competition or short story competition, competitions let you compete against other writers and even help you get useful feedback on your writing. Most competitions even have rules to structure your writing, these rules can help you prepare for the real world of writing and getting your work published. And not only that you might even win some cool prizes!

Keep a notebook

Every writer’s best friend is their notebook. Wherever you go make sure you have a notebook handy to jot down any ideas you get on the go. Inspiration can come from anywhere , so the next time you get an idea instead of forgetting about it, write it down. You never know, this idea could become a best-selling novel in the future.

Research your ideas

So, you got a couple of ideas for short stories. The next step is to research these ideas deeper.

Researching your ideas could involve reading books similar to your ideas or going online to learn more about a particular topic. For example, if you wanted to write a book on dragons, you would want to know everything about them in history to come up with a good, relatable storyline for your book.

Create Writing Goals

How do you know if your writing is improving over time? Simple – Just create writing goals for yourself. Examples of writing goals might include, to write 100 words every day or to write 600 words by the end of next week. Whatever your goals make sure you can measure them easily. That way you’ll know if you met them or not. You might want to take a look at these bullet journal layouts for writers to help you track the progress of your writing.

Follow your passions

Writing can be tedious and many people even give up after writing a few words. The only way you can keep that fire burning is by writing about your true passions. Whatever it is you enjoy doing or love, you could just write about those things. These are the types of things you’ll enjoy researching and already know so much about, making writing a whole lot more fun!

Don’t Settle for the first draft

You finally wrote your first story. But the writing process isn’t complete yet! Now it’s time to read your story and make the all-important edits. Editing your story is more than just fixing spelling or grammar mistakes. It’s also about criticising your own work and looking for areas of improvement. For example, is the conflict strong enough? Is your opening line exciting? How can you improve your ending?

Plan before writing

Never just jump into writing your story. Always plan first! Whether this means listing down the key scenes in your story or using a storyboard template to map out these scenes. You should have an outline of your story somewhere, which you can refer to when actually writing your story. This way you won’t make basic mistakes like not having a climax in your story which builds up to your main conflict or missing crucial characters out.

It’s strange the difference it makes to read your writing out aloud compared to reading it in your head. When reading aloud you tend to notice more mistakes in your sentences or discover paragraphs which make no sense at all. You might even want to read your story aloud to your family or a group of friends to get feedback on how your story sounds.

Pace your story

Pacing is important. You don’t want to just start and then quickly jump into the main conflict because this will take all the excitement away from your conflict. And at the same time, you don’t want to give the solution away too early and this will make your conflict too easy for your characters to solve. The key is to gradually build up to your conflict by describing your characters and the many events that lead up to the main conflict. Then you might want to make the conflict more difficult for your characters by including more than one issue in your story to solve.

Think about themes

Every story has a theme or moral. Some stories are about friendship, others are about the dangers of trusting strangers. And a story can even have more than one theme. The point of a theme is to give something valuable to your readers once they have finished reading your book. In other words, to give them a life lesson, they’ll never forget!

Use dialogue carefully

Dialogue is a tricky thing to get right. Your whole story should not be made up of dialogue unless you’re writing a script. Alternatively, it can be strange to include no dialogue at all in your story. The purpose of dialogue should be to move your story forward. It should also help your readers learn more about a particular character’s personality and their relationship with other characters in your book.

One thing to avoid with dialogue is… small talk! There’s no point in writing dialogue, such as “How’s the weather?”, if your story has nothing to do with the weather. This is because it doesn’t move your story along. For more information check out this guide on how to write dialogue in a story .

Write now, edit later

Writing is a magical process. Don’t lose that magic by focusing on editing your sentences while you’re still writing your story up. Not only could this make your story sound fragmented, but you might also forget some key ideas to include in your story or take away the imagination from your writing. When it comes to creative writing, just write and come back to editing your story later.

Ask yourself questions

Always question your writing. Once done, think about any holes in your story. Is there something the reader won’t understand or needs further describing? What if your character finds another solution to solving the conflict? How about adding a new character or removing a character from your story? There are so many questions to ask and keep asking them until you feel confident about your final piece.

Create a dedicated writing space

Some kids like writing on their beds, others at the kitchen table. While this is good for beginners, going pro with your writing might require having a dedicated writing space. Some of the basics you’ll need is a desk and comfy chair, along with writing materials like pens, pencils and notebooks. But to really create an inspiring place, you could also stick some beautiful pictures, some inspiring quotes from writers and anything else that will keep you motivated and prepared.

Beware of flowery words

Vocabulary is good. It’s always exciting when you learn a new word that you have never heard before. But don’t go around plotting in complicated words into your story, unless it’s necessary to show a character’s personality. Most long words are not natural sounding, meaning your audience will have a hard time relating to your story if it’s full of complicated words from the dictionary like Xenophobia or Xylograph .

Create believable characters

Nobody’s perfect. And why should your story characters be any different? To create believable characters, you’ll need to give them some common flaws as well as some really cool strengths. Your character’s flaws can be used as a setback to why they can’t achieve their goals, while their strengths are the things that will help win over adversity. Just think about your own strengths and weaknesses and use them as inspirations for your storybook characters. You can use the Imagine Forest character creator to plan out your story characters.

Show, don’t tell

You can say that someone is nice or you can show them how that person is nice. Take the following as an example, “Katie was a nice girl.” Now compare that sentence to this, “Katie spent her weekends at the retirement home, singing to the seniors and making them laugh.”. The difference between the two sentences is huge. The first one sounds boring and you don’t really know why Katie is nice. While in the second sentence, you get the sense that Katie is nice from her actions without even using the word nice in the sentence!

Make the conflict impossible

Imagine the following scenario, you are a championship boxer who has won many medals over the year and the conflict is…Well, you got a boxing match coming up. Now that doesn’t sound so exciting! In fact, most readers won’t even care about the boxer winning the match or not!

Now imagine this scenario: You’re a poor kid from New Jersey, you barely have enough money to pay the bills. You never did any professional boxing, but you want to enter a boxing competition, so you can win and use the money to pay your bills.

The second scenario has a bigger mountain to climb. In other words, a much harder challenge to face compared to the character in the first scenario. Giving your characters an almost impossible task or conflict is essential in good story-telling.

Write powerful scenes

Scenes help build a picture in your reader’s mind without even including any actual pictures in your story. Creating powerful scenes involves more than describing the appearance of a setting, it’s also about thinking about the smell, the sounds and what your characters are feeling while they are in a particular setting. By being descriptive with your scenes, your audience can imagine themselves being right there with characters through the hard times and good times!

There’s nothing worse than an ending which leaves the reader feeling underwhelmed. You read all the way through and then it just ends in the most typical, obvious way ever! Strong endings don’t always end on a happy ending. They can end with a sad ending or a cliff-hanger. In fact, most stories actually leave the reader with more questions in their head, as they wonder what happens next. This then gives you the opportunity to create even more books to continue the story and keep your readers hooked for life (or at least for a very long time)!

Over 25 creative writing tips later and you should now be ready to master the art of creative writing! The most important tip for all you creative writers out there is to be imaginative! Without a good imagination, you’ll struggle to wow your audience with your writing skills. Do you have any more creative writing tips to share? Let us know in the comments!

Marty the wizard is the master of Imagine Forest. When he's not reading a ton of books or writing some of his own tales, he loves to be surrounded by the magical creatures that live in Imagine Forest. While living in his tree house he has devoted his time to helping children around the world with their writing skills and creativity.

Related Posts

Comments loading...

VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Feb 14, 2023

10 Types of Creative Writing (with Examples You’ll Love)

A lot falls under the term ‘creative writing’: poetry, short fiction, plays, novels, personal essays, and songs, to name just a few. By virtue of the creativity that characterizes it, creative writing is an extremely versatile art. So instead of defining what creative writing is , it may be easier to understand what it does by looking at examples that demonstrate the sheer range of styles and genres under its vast umbrella.

To that end, we’ve collected a non-exhaustive list of works across multiple formats that have inspired the writers here at Reedsy. With 20 different works to explore, we hope they will inspire you, too.

People have been writing creatively for almost as long as we have been able to hold pens. Just think of long-form epic poems like The Odyssey or, later, the Cantar de Mio Cid — some of the earliest recorded writings of their kind.

Poetry is also a great place to start if you want to dip your own pen into the inkwell of creative writing. It can be as short or long as you want (you don’t have to write an epic of Homeric proportions), encourages you to build your observation skills, and often speaks from a single point of view .

Here are a few examples:

“Ozymandias” by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch far away.

This classic poem by Romantic poet Percy Shelley (also known as Mary Shelley’s husband) is all about legacy. What do we leave behind? How will we be remembered? The great king Ozymandias built himself a massive statue, proclaiming his might, but the irony is that his statue doesn’t survive the ravages of time. By framing this poem as told to him by a “traveller from an antique land,” Shelley effectively turns this into a story. Along with the careful use of juxtaposition to create irony, this poem accomplishes a lot in just a few lines.

“Trying to Raise the Dead” by Dorianne Laux

A direction. An object. My love, it needs a place to rest. Say anything. I’m listening. I’m ready to believe. Even lies, I don’t care.

Poetry is cherished for its ability to evoke strong emotions from the reader using very few words which is exactly what Dorianne Laux does in “ Trying to Raise the Dead .” With vivid imagery that underscores the painful yearning of the narrator, she transports us to a private nighttime scene as the narrator sneaks away from a party to pray to someone they’ve lost. We ache for their loss and how badly they want their lost loved one to acknowledge them in some way. It’s truly a masterclass on how writing can be used to portray emotions.

If you find yourself inspired to try out some poetry — and maybe even get it published — check out these poetry layouts that can elevate your verse!

Song Lyrics

Poetry’s closely related cousin, song lyrics are another great way to flex your creative writing muscles. You not only have to find the perfect rhyme scheme but also match it to the rhythm of the music. This can be a great challenge for an experienced poet or the musically inclined.

To see how music can add something extra to your poetry, check out these two examples:

“Hallelujah” by Leonard Cohen

You say I took the name in vain I don't even know the name But if I did, well, really, what's it to ya? There's a blaze of light in every word It doesn't matter which you heard The holy or the broken Hallelujah

Metaphors are commonplace in almost every kind of creative writing, but will often take center stage in shorter works like poetry and songs. At the slightest mention, they invite the listener to bring their emotional or cultural experience to the piece, allowing the writer to express more with fewer words while also giving it a deeper meaning. If a whole song is couched in metaphor, you might even be able to find multiple meanings to it, like in Leonard Cohen’s “ Hallelujah .” While Cohen’s Biblical references create a song that, on the surface, seems like it’s about a struggle with religion, the ambiguity of the lyrics has allowed it to be seen as a song about a complicated romantic relationship.

“I Will Follow You into the Dark” by Death Cab for Cutie

If Heaven and Hell decide that they both are satisfied Illuminate the no's on their vacancy signs If there's no one beside you when your soul embarks Then I'll follow you into the dark

You can think of song lyrics as poetry set to music. They manage to do many of the same things their literary counterparts do — including tugging on your heartstrings. Death Cab for Cutie’s incredibly popular indie rock ballad is about the singer’s deep devotion to his lover. While some might find the song a bit too dark and macabre, its melancholy tune and poignant lyrics remind us that love can endure beyond death.

Plays and Screenplays

From the short form of poetry, we move into the world of drama — also known as the play. This form is as old as the poem, stretching back to the works of ancient Greek playwrights like Sophocles, who adapted the myths of their day into dramatic form. The stage play (and the more modern screenplay) gives the words on the page a literal human voice, bringing life to a story and its characters entirely through dialogue.

Interested to see what that looks like? Take a look at these examples:

All My Sons by Arthur Miller

“I know you're no worse than most men but I thought you were better. I never saw you as a man. I saw you as my father.”

Arthur Miller acts as a bridge between the classic and the new, creating 20th century tragedies that take place in living rooms and backyard instead of royal courts, so we had to include his breakout hit on this list. Set in the backyard of an all-American family in the summer of 1946, this tragedy manages to communicate family tensions in an unimaginable scale, building up to an intense climax reminiscent of classical drama.

💡 Read more about Arthur Miller and classical influences in our breakdown of Freytag’s pyramid .

“Everything is Fine” by Michael Schur ( The Good Place )

“Well, then this system sucks. What...one in a million gets to live in paradise and everyone else is tortured for eternity? Come on! I mean, I wasn't freaking Gandhi, but I was okay. I was a medium person. I should get to spend eternity in a medium place! Like Cincinnati. Everyone who wasn't perfect but wasn't terrible should get to spend eternity in Cincinnati.”

A screenplay, especially a TV pilot, is like a mini-play, but with the extra job of convincing an audience that they want to watch a hundred more episodes of the show. Blending moral philosophy with comedy, The Good Place is a fun hang-out show set in the afterlife that asks some big questions about what it means to be good.

It follows Eleanor Shellstrop, an incredibly imperfect woman from Arizona who wakes up in ‘The Good Place’ and realizes that there’s been a cosmic mixup. Determined not to lose her place in paradise, she recruits her “soulmate,” a former ethics professor, to teach her philosophy with the hope that she can learn to be a good person and keep up her charade of being an upstanding citizen. The pilot does a superb job of setting up the stakes, the story, and the characters, while smuggling in deep philosophical ideas.

Personal essays

Our first foray into nonfiction on this list is the personal essay. As its name suggests, these stories are in some way autobiographical — concerned with the author’s life and experiences. But don’t be fooled by the realistic component. These essays can take any shape or form, from comics to diary entries to recipes and anything else you can imagine. Typically zeroing in on a single issue, they allow you to explore your life and prove that the personal can be universal.

Here are a couple of fantastic examples:

“On Selling Your First Novel After 11 Years” by Min Jin Lee (Literary Hub)

There was so much to learn and practice, but I began to see the prose in verse and the verse in prose. Patterns surfaced in poems, stories, and plays. There was music in sentences and paragraphs. I could hear the silences in a sentence. All this schooling was like getting x-ray vision and animal-like hearing.

This deeply honest personal essay by Pachinko author Min Jin Lee is an account of her eleven-year struggle to publish her first novel . Like all good writing, it is intensely focused on personal emotional details. While grounded in the specifics of the author's personal journey, it embodies an experience that is absolutely universal: that of difficulty and adversity met by eventual success.

“A Cyclist on the English Landscape” by Roff Smith (New York Times)

These images, though, aren’t meant to be about me. They’re meant to represent a cyclist on the landscape, anybody — you, perhaps.

Roff Smith’s gorgeous photo essay for the NYT is a testament to the power of creatively combining visuals with text. Here, photographs of Smith atop a bike are far from simply ornamental. They’re integral to the ruminative mood of the essay, as essential as the writing. Though Smith places his work at the crosscurrents of various aesthetic influences (such as the painter Edward Hopper), what stands out the most in this taciturn, thoughtful piece of writing is his use of the second person to address the reader directly. Suddenly, the writer steps out of the body of the essay and makes eye contact with the reader. The reader is now part of the story as a second character, finally entering the picture.

Short Fiction

The short story is the happy medium of fiction writing. These bite-sized narratives can be devoured in a single sitting and still leave you reeling. Sometimes viewed as a stepping stone to novel writing, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Short story writing is an art all its own. The limited length means every word counts and there’s no better way to see that than with these two examples:

“An MFA Story” by Paul Dalla Rosa (Electric Literature)

At Starbucks, I remembered a reading Zhen had given, a reading organized by the program’s faculty. I had not wanted to go but did. In the bar, he read, "I wrote this in a Starbucks in Shanghai. On the bank of the Huangpu." It wasn’t an aside or introduction. It was two lines of the poem. I was in a Starbucks and I wasn’t writing any poems. I wasn’t writing anything.

This short story is a delightfully metafictional tale about the struggles of being a writer in New York. From paying the bills to facing criticism in a writing workshop and envying more productive writers, Paul Dalla Rosa’s story is a clever satire of the tribulations involved in the writing profession, and all the contradictions embodied by systemic creativity (as famously laid out in Mark McGurl’s The Program Era ). What’s more, this story is an excellent example of something that often happens in creative writing: a writer casting light on the private thoughts or moments of doubt we don’t admit to or openly talk about.

“Flowering Walrus” by Scott Skinner (Reedsy)

I tell him they’d been there a month at least, and he looks concerned. He has my tongue on a tissue paper and is gripping its sides with his pointer and thumb. My tongue has never spent much time outside of my mouth, and I imagine it as a walrus basking in the rays of the dental light. My walrus is not well.

A winner of Reedsy’s weekly Prompts writing contest, ‘ Flowering Walrus ’ is a story that balances the trivial and the serious well. In the pauses between its excellent, natural dialogue , the story manages to scatter the fear and sadness of bad medical news, as the protagonist hides his worries from his wife and daughter. Rich in subtext, these silences grow and resonate with the readers.

Want to give short story writing a go? Give our free course a go!

FREE COURSE

How to Craft a Killer Short Story

From pacing to character development, master the elements of short fiction.

Perhaps the thing that first comes to mind when talking about creative writing, novels are a form of fiction that many people know and love but writers sometimes find intimidating. The good news is that novels are nothing but one word put after another, like any other piece of writing, but expanded and put into a flowing narrative. Piece of cake, right?

To get an idea of the format’s breadth of scope, take a look at these two (very different) satirical novels:

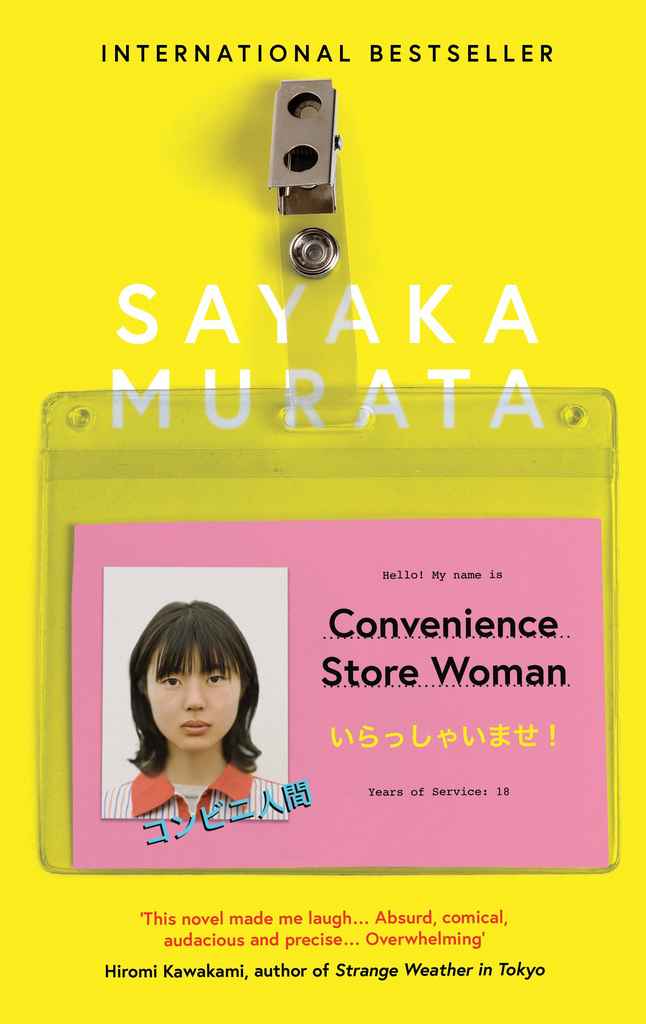

Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata

I wished I was back in the convenience store where I was valued as a working member of staff and things weren’t as complicated as this. Once we donned our uniforms, we were all equals regardless of gender, age, or nationality — all simply store workers.

Keiko, a thirty-six-year-old convenience store employee, finds comfort and happiness in the strict, uneventful routine of the shop’s daily operations. A funny, satirical, but simultaneously unnerving examination of the social structures we take for granted, Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman is deeply original and lingers with the reader long after they’ve put it down.

Erasure by Percival Everett

The hard, gritty truth of the matter is that I hardly ever think about race. Those times when I did think about it a lot I did so because of my guilt for not thinking about it.

Erasure is a truly accomplished satire of the publishing industry’s tendency to essentialize African American authors and their writing. Everett’s protagonist is a writer whose work doesn’t fit with what publishers expect from him — work that describes the “African American experience” — so he writes a parody novel about life in the ghetto. The publishers go crazy for it and, to the protagonist’s horror, it becomes the next big thing. This sophisticated novel is both ironic and tender, leaving its readers with much food for thought.

Creative Nonfiction

Creative nonfiction is pretty broad: it applies to anything that does not claim to be fictional (although the rise of autofiction has definitely blurred the boundaries between fiction and nonfiction). It encompasses everything from personal essays and memoirs to humor writing, and they range in length from blog posts to full-length books. The defining characteristic of this massive genre is that it takes the world or the author’s experience and turns it into a narrative that a reader can follow along with.

Here, we want to focus on novel-length works that dig deep into their respective topics. While very different, these two examples truly show the breadth and depth of possibility of creative nonfiction:

Men We Reaped by Jesmyn Ward

Men’s bodies litter my family history. The pain of the women they left behind pulls them from the beyond, makes them appear as ghosts. In death, they transcend the circumstances of this place that I love and hate all at once and become supernatural.

Writer Jesmyn Ward recounts the deaths of five men from her rural Mississippi community in as many years. In her award-winning memoir , she delves into the lives of the friends and family she lost and tries to find some sense among the tragedy. Working backwards across five years, she questions why this had to happen over and over again, and slowly unveils the long history of racism and poverty that rules rural Black communities. Moving and emotionally raw, Men We Reaped is an indictment of a cruel system and the story of a woman's grief and rage as she tries to navigate it.

Cork Dork by Bianca Bosker

He believed that wine could reshape someone’s life. That’s why he preferred buying bottles to splurging on sweaters. Sweaters were things. Bottles of wine, said Morgan, “are ways that my humanity will be changed.”

In this work of immersive journalism , Bianca Bosker leaves behind her life as a tech journalist to explore the world of wine. Becoming a “cork dork” takes her everywhere from New York’s most refined restaurants to science labs while she learns what it takes to be a sommelier and a true wine obsessive. This funny and entertaining trip through the past and present of wine-making and tasting is sure to leave you better informed and wishing you, too, could leave your life behind for one devoted to wine.

Illustrated Narratives (Comics, graphic novels)

Once relegated to the “funny pages”, the past forty years of comics history have proven it to be a serious medium. Comics have transformed from the early days of Jack Kirby’s superheroes into a medium where almost every genre is represented. Humorous one-shots in the Sunday papers stand alongside illustrated memoirs, horror, fantasy, and just about anything else you can imagine. This type of visual storytelling lets the writer and artist get creative with perspective, tone, and so much more. For two very different, though equally entertaining, examples, check these out:

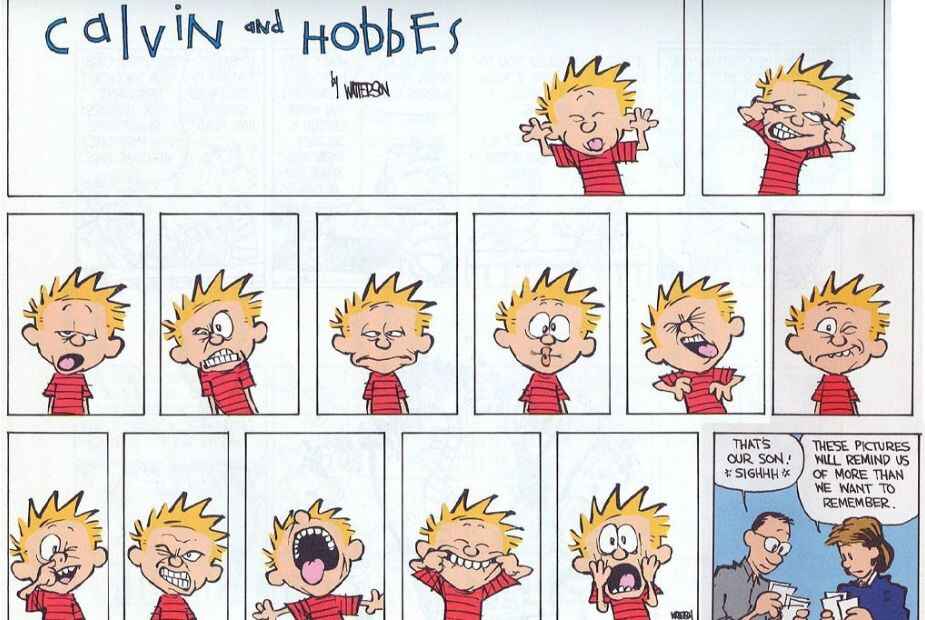

Calvin & Hobbes by Bill Watterson

"Life is like topography, Hobbes. There are summits of happiness and success, flat stretches of boring routine and valleys of frustration and failure."

This beloved comic strip follows Calvin, a rambunctious six-year-old boy, and his stuffed tiger/imaginary friend, Hobbes. They get into all kinds of hijinks at school and at home, and muse on the world in the way only a six-year-old and an anthropomorphic tiger can. As laugh-out-loud funny as it is, Calvin & Hobbes ’ popularity persists as much for its whimsy as its use of humor to comment on life, childhood, adulthood, and everything in between.

From Hell by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell

"I shall tell you where we are. We're in the most extreme and utter region of the human mind. A dim, subconscious underworld. A radiant abyss where men meet themselves. Hell, Netley. We're in Hell."

Comics aren't just the realm of superheroes and one-joke strips, as Alan Moore proves in this serialized graphic novel released between 1989 and 1998. A meticulously researched alternative history of Victorian London’s Ripper killings, this macabre story pulls no punches. Fact and fiction blend into a world where the Royal Family is involved in a dark conspiracy and Freemasons lurk on the sidelines. It’s a surreal mad-cap adventure that’s unsettling in the best way possible.

Video Games and RPGs

Probably the least expected entry on this list, we thought that video games and RPGs also deserved a mention — and some well-earned recognition for the intricate storytelling that goes into creating them.

Essentially gamified adventure stories, without attention to plot, characters, and a narrative arc, these games would lose a lot of their charm, so let’s look at two examples where the creative writing really shines through:

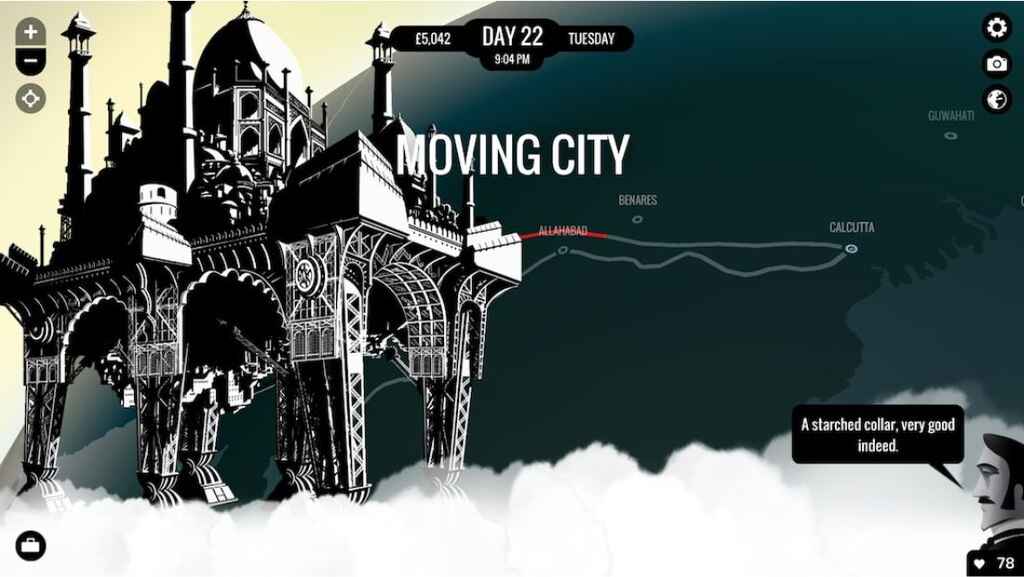

80 Days by inkle studios

"It was a triumph of invention over nature, and will almost certainly disappear into the dust once more in the next fifty years."

Named Time Magazine ’s game of the year in 2014, this narrative adventure is based on Around the World in 80 Days by Jules Verne. The player is cast as the novel’s narrator, Passpartout, and tasked with circumnavigating the globe in service of their employer, Phileas Fogg. Set in an alternate steampunk Victorian era, the game uses its globe-trotting to comment on the colonialist fantasies inherent in the original novel and its time period. On a storytelling level, the choose-your-own-adventure style means no two players’ journeys will be the same. This innovative approach to a classic novel shows the potential of video games as a storytelling medium, truly making the player part of the story.

What Remains of Edith Finch by Giant Sparrow

"If we lived forever, maybe we'd have time to understand things. But as it is, I think the best we can do is try to open our eyes, and appreciate how strange and brief all of this is."

This video game casts the player as 17-year-old Edith Finch. Returning to her family’s home on an island in the Pacific northwest, Edith explores the vast house and tries to figure out why she’s the only one of her family left alive. The story of each family member is revealed as you make your way through the house, slowly unpacking the tragic fate of the Finches. Eerie and immersive, this first-person exploration game uses the medium to tell a series of truly unique tales.

Fun and breezy on the surface, humor is often recognized as one of the trickiest forms of creative writing. After all, while you can see the artistic value in a piece of prose that you don’t necessarily enjoy, if a joke isn’t funny, you could say that it’s objectively failed.

With that said, it’s far from an impossible task, and many have succeeded in bringing smiles to their readers’ faces through their writing. Here are two examples:

‘How You Hope Your Extended Family Will React When You Explain Your Job to Them’ by Mike Lacher (McSweeney’s Internet Tendency)

“Is it true you don’t have desks?” your grandmother will ask. You will nod again and crack open a can of Country Time Lemonade. “My stars,” she will say, “it must be so wonderful to not have a traditional office and instead share a bistro-esque coworking space.”

Satire and parody make up a whole subgenre of creative writing, and websites like McSweeney’s Internet Tendency and The Onion consistently hit the mark with their parodies of magazine publishing and news media. This particular example finds humor in the divide between traditional family expectations and contemporary, ‘trendy’ work cultures. Playing on the inherent silliness of today’s tech-forward middle-class jobs, this witty piece imagines a scenario where the writer’s family fully understands what they do — and are enthralled to hear more. “‘Now is it true,’ your uncle will whisper, ‘that you’ve got a potential investment from one of the founders of I Can Haz Cheezburger?’”

‘Not a Foodie’ by Hilary Fitzgerald Campbell (Electric Literature)

I’m not a foodie, I never have been, and I know, in my heart, I never will be.

Highlighting what she sees as an unbearable social obsession with food , in this comic Hilary Fitzgerald Campbell takes a hilarious stand against the importance of food. From the writer’s courageous thesis (“I think there are more exciting things to talk about, and focus on in life, than what’s for dinner”) to the amusing appearance of family members and the narrator’s partner, ‘Not a Foodie’ demonstrates that even a seemingly mundane pet peeve can be approached creatively — and even reveal something profound about life.

We hope this list inspires you with your own writing. If there’s one thing you take away from this post, let it be that there is no limit to what you can write about or how you can write about it.

In the next part of this guide, we'll drill down into the fascinating world of creative nonfiction.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

We made a writing app for you

Yes, you! Write. Format. Export for ebook and print. 100% free, always.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

How to Develop Your Creative Writing Process

by Melissa Donovan | Feb 7, 2023 | Creative Writing | 45 comments

What steps do you take in your creative writing process?

Writing experts often want us to believe that there is only one worthwhile creative writing process. It usually goes something like this:

- Rough draft

- Revise (repeat, repeat, repeat, repeat)

- Edit, proof, and polish

This is a good system — it absolutely works. But does it work for everyone?

Examining the Creative Writing Process

I’ve been thinking a lot about the creative writing process. Lately I’ve found myself working on all types of projects: web pages, blog posts, a science-fiction series, and of course, books on the craft of writing .

I’ve thought about the steps I take to get a project completed and realized that the writing process I use varies from project to project and depends on the level of difficulty, the length and scope of the project, and even my state of mind. If I’m feeling inspired, a blog post will come flying out of my head. If I’m tired, hungry, or unmotivated, or if the project is complicated, then it’s a struggle, and I have to work a little harder. Brainstorming and outlining can help. A lot.

It occurred to me that I don’t have one creative writing process. I have several. And I always use the one that’s best suited for a particular project.

A Process for Every Project

I once wrote a novel with no plan whatsoever. I started with nothing more than a couple of characters. Thirty days and fifty thousand words later, I had completed the draft of a novel (thanks, NaNoWriMo!).

But usually, I need more structure than that. Whether I’m working on a blog post, a page of web copy, a nonfiction book, or a novel, I find that starting with a plan saves a lot of time and reduces the number of revisions that I have to work through later. It’s also more likely to result in a project getting completed and published.

But every plan is different. Sometimes I’ll jot down a quick list of points I want to make in a blog post. This can take just a minute or two, and it makes the writing flow fast and easy. Other times, I’ll spend weeks — even months — working out the intricate details of a story with everything from character sketches to outlines and heaps of research. On the other hand, when I wrote a book of creative writing prompts , I had a rough target for how many prompts I wanted to generate, and I did a little research, but I didn’t create an outline.

I’ve tried lots of different processes, and I continue to develop my processes over time. I also remain cognizant that whatever’s working for me right now might not work in five or ten years. I will keep revising and tweaking my process, depending on my goals.

Finding the Best Process

I’ve written a novel with no process, and I’ve written a novel by going through every step imaginable: brainstorming, character sketches, research, summarizing, outlines, and then multiple drafts, revisions, and edits.

These experiences were vastly different. I can’t say that one was more enjoyable than the other. But it’s probably worth noting that the book I wrote with no process is still sitting on my hard drive somewhere whereas the one I wrote with a methodical yet creative writing process got completed, polished, and published.

In fact, I have found that using a process generates better results if my goal is to complete and publish a project.

But not every piece of writing is destined for public consumption. Sometimes I write just for fun. No plan, no process, no pressure. I just let the words flow. Every once in a while, these projects find their way to completion and get sent out into the world.

It is only by experimenting with a variety of processes that you will find the creative writing process that works best for you. And you’ll also have to decide what “best” means. Is it the process that’s most enjoyable? Or is it the process that leads you to publication? Only you know the answer to that.

I encourage you to try different writing processes. Write a blog post on the fly. Make an outline for a novel. Do some in-depth research for an epic poem. Try the process at the top of this page, and then do some research to find other processes that you can experiment with. Keep trying new things, and when you find whatever helps you achieve your goals, stick with it, but remain open to new methods that you can bring into your process.

What’s Your Creative Writing Process?

Creative writing processes are good. The reason our predecessors developed these processes and shared them, along with a host of other writing tips, was to help us be more productive and produce better writing. Techniques and strategies can be helpful, but it’s our responsibility to know what works for us as individuals and as creative writers and to know what will cause us to infinitely spin our wheels.

What’s your creative writing process? Do you have one? Do you ever get stuck in the writing process? How do you get unstuck?

45 Comments

Hi Melissa: I do a lot of research on the topic I’ve chosen to write about. As I do the research I take notes on a word perfect document. When I have a whole lot of information written down–in a jumble–I usually leave it and go do something else. Then I sit down and start to work with the information I’ve gathered and just start writing. The first draft I come up with is usually pretty bad, and then I revise and revise until I have something beautiful that I feel is fit to share with the rest of the world. That’s when I hit the “publish” button 🙂 I’m trying to implement Parkinson’s Law to focus my thinking a little more as I write so that I can get the articles out a bit faster.

My favorite pre-writing process would have to be getting a nice big whiteboard and charting characters and plots down. I find that it really helps me anchor on to specific traits of a character, especially if the persona happens to be a dynamic one. Such charting helps me out dramatically in creating an evolving storyline by not allowing me to forget key twists and other storyline-intensive elements =)

That being said, my favorite pre-charting process is going out the on nights leading to it for a few rounds of beer with good friends!

Hi Melissa – I’m like you – I do different things depending on what I’m writing. With the novel I’m working on now – alot of stuff I write won’t even go into it.

Some of the stuff the gurus recommend are the kind of things I’d do if I was writing an essay – but nothing else.

I don’t know if I have a set process. I start with morning pages and journaling. then whatever comes streaming from that gets written. As I go about my day I have a notebook that stays with me whereever I go and I am constantly writing in it, notes, ideas, themes, Sentances that begin with “I wonder…” and then then next monring the notebook is with me during quiet time and these thoughts are often carried right in to the process all over again. So…if that is a process, I guess…I never really thought about it. As I have said before, a lot of my writing also takes place in my jacuzzi..so…

I guess my process is that when its falling out of my head I try and catch it.

This will be the first year that I attempt NaNO so I will need to be more organized. This is good for thinking ahead. One of the reasons I started blogging in the first place was to get in the discipline of writing every day. That was the first step. Just creating the habit. This will be a good next step.

These days, I feel so scattered, I feel like I’m not getting anything done at all! (grin)

Melissa, I am really organized but my writing process has never followed the guidelines. I’ve tried them on for size and find that they don’t fit. Even in school, I never did outlines and drafts so I suppose I trained myself against the system! I always do research first and gather all of my notes, clips in one location. As for the writing process itself I let it rip, then go back and fine tune. It has worked for me thus far but I’m always open to trying new techniques on for size, hey if they fit I’m all on board!

@Marelisa, that doesn’t surprise me. Your posts are comprehensive, detailed, and extremely informative. I can tell you care a lot about your topic and about your writing. That’s one of the reasons I enjoy your blog; your passion is palpable.

@Joey, I love the planning stage too. In fact, sometimes I get stuck there and never make it out. Ooh, and white boards. Yes. Those are good. Usually I just use drawing paper though. When I do NaNo, I’m going to try to do less planning. In fact, I’m going to plan in October and just write in November. I’m hoping this new strategy will result in winning my word count goal!

@Cath, I sort of pick and choose which tips from the gurus I use.

@Wendi, you write in the jacuzzi? That’s cool. Or hot. I guess it’s hot. Your process sounds really natural. I started blogging for the exact same reason — to write every day. I’m excited to hear you’re doing NaNo too. That will be fun, and we can offer each other moral support!

@Deb (Punctuality), it sounds like you have a lot going on! I get into that mode sometimes, where I’m so overwhelmed, I can’t get anything done. It’s really frustrating. Sometimes I have to shut down for a day to get my bearings and that’s the only way I can get back on track.

@Karen, that’s probably why your writing flows so well, because you just let it do its thing. I remember learning to do outlines back in 6th grade but it didn’t stick. Later, in college, we’d have to do them as assignments, so I didn’t have a choice. I realized that they sped up the writing process. Now I do them for some (but not all) projects. But I will say this: I actually enjoy outlining (weird?).

Melissa, I’m not a real writer but I do love reading how you, who are, go about the business of putting words to paper. As always, a great post. Thanks.