Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

UConn Today

- School and College News

- Arts & Culture

- Community Impact

- Entrepreneurship

- Health & Well-Being

- Research & Discovery

- UConn Health

- University Life

- UConn Voices

- University News

August 7, 2018 | Kenneth Best - UConn Communications

Know Thyself: The Philosophy of Self-Knowledge

Dating back to an ancient Greek inscription, the injunction to 'know thyself' has encouraged people to engage in a search for self-understanding. Philosophy professor Mitchell Green discusses its history and relevance to the present.

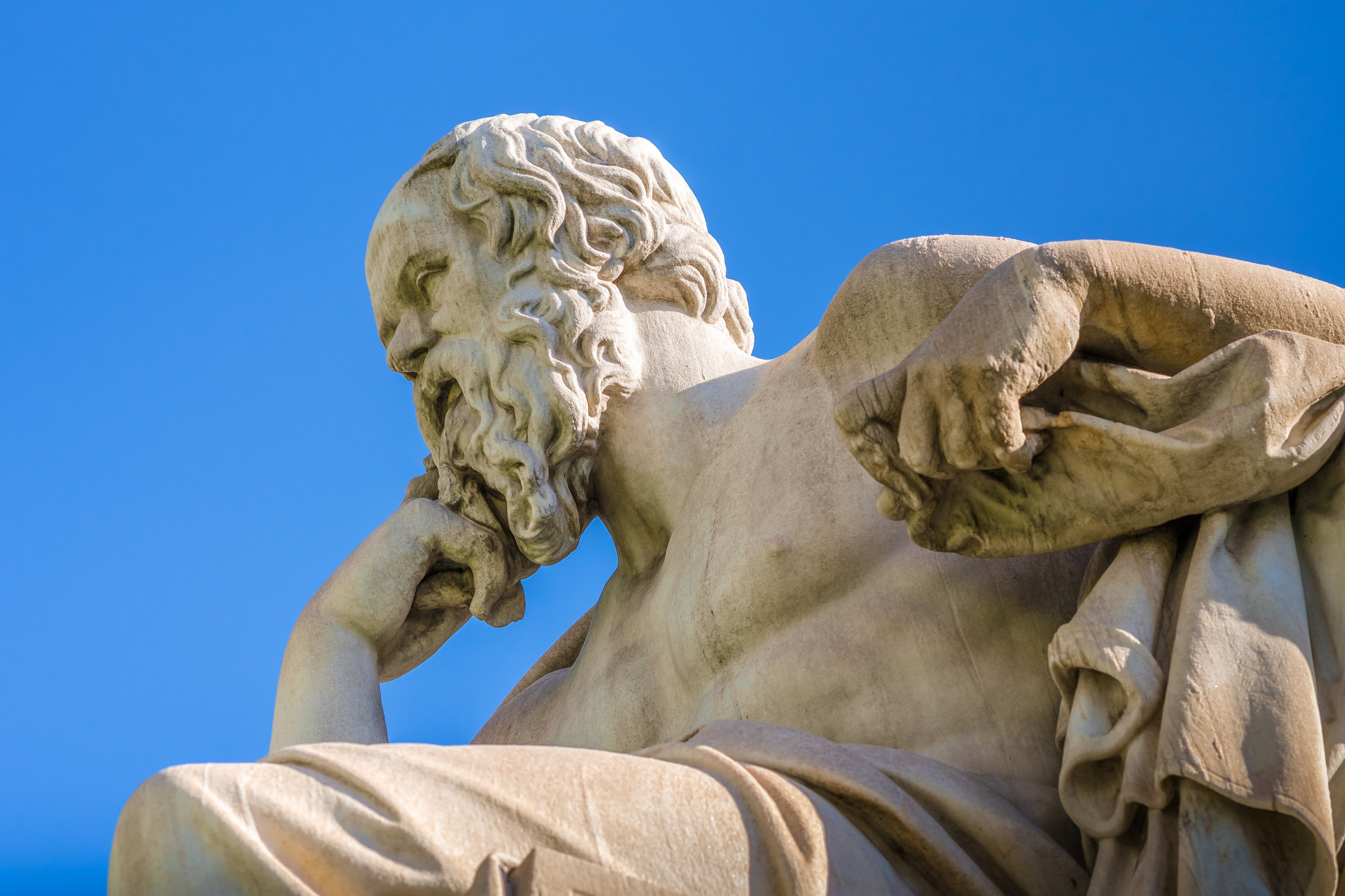

From Socrates to today's undergraduates, philosophy professor Mitchell Green discusses the history and current relevance of the human quest for self-knowledge. (Getty Images)

UConn philosopher Mitchell S. Green leads a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) titled Know Thyself: The Value and Limits of Self-Knowledge on the online learning platform Coursera. The course is based on his 2018 book (published by Routledge) of the same name. He recently spoke with Ken Best of UConn Today about the philosophy and understanding of self-knowledge. This is an edited transcript of their discussion.

Q. ‘Know Thyself’ was carved into stone at the entrance to Apollo’s temple at Delphi in Greece, according to legend. Scholars, philosophers, and civilizations have debated this question for a long time. Why have we not been able to find the answer?

A. I’m not sure that every civilization or even most civilizations have taken the goal to achieve self-knowledge as being among the most important ones. It comes and goes. It did have cachet in the Greece of 300-400 BC. Whether it had similar cachet 200 years later or had something like cultural importance in the heyday of Roman civilization is another question. Of course some philosophers would have enjoined people to engage in a search for self-understanding; some not so much. Likewise, think about the Middle Ages. There’s a case in which we don’t get a whole lot of emphasis on knowing the self, instead the focus was on knowing God. It’s only when Descartes comes on the scene centuries later that we begin to get more of a focus on introspection and understanding ourselves by looking within. Also, the injunction to “know thyself” is not a question, and would have to be modified in some way to pose a question. However, suppose the question is, “Is it possible to know oneself, either in part or fully.” In that case, I’d suggest that we’ve made considerable progress in answering this question over the last two millennia, and in the Know Thyself book, and in the MOOC of the same name, I try to guide readers and students through some of what we have learned.

Q. You point out that the shift Descartes brought about is a turning point in Western philosophy.

A. Right. It’s for various reasons cultural, political, economic, and ideological that the norm of self-knowledge has come and gone with the tides through Western history. Even if we had been constantly enjoined to achieve self-knowledge for the 2,300 years since the time Socrates spoke, just as Sigmund Freud said about civilization – that civilization is constantly being created anew and everyone being born has to work their way up to being civilized being – so, too, the project of achieving self-knowledge is a project for every single new member of our species. No one can be given it at birth. It’s not an achievement you get for free like a high IQ or a prominent chin. Continuing to beat that drum, to remind people of the importance of that, is something we’ll always be doing. I’m doubtful we’ll ever reach a point we can all say: Yup, we’re good on that. We’ve got that covered, we’ve got self-knowledge down. That’s a challenge for each of us, every time somebody is born. I would also say, given the ambient, environmental factors as well as the predilections that we’re born with as part of our cognitive and genetic nature, there are probably pressures that push against self-knowledge as well. For instance, in the book I talk about the cognitive immune system that tends to make us spin information in our own favor. When something goes bad, there’s a certain part of us, hopefully within bounds, that tends to see the glass as half full rather than half empty. That’s probably a good way of getting yourself up off the floor after you’ve been knocked down.

Q. Retirement planners tell us you’re supposed to know yourself well enough to know what your needs are going to be – create art or music, or travel – when you have all of your time to use. At what point should that point of getting to know yourself better begin?

A. I wouldn’t encourage a 9-year-old to engage in a whole lot of self-scrutiny, but I would say even when you’re young some of those indirect, especially self-distancing, types of activities, can be of value. Imagine a 9-year-old gets in a fight on the playground and a teacher asks him: Given what you said to the other kid that provoked the fight, if he had said that to you, how would you feel? That might be intended to provoke an inkling of self-knowledge – if not in the form of introspection, in the form of developing empathetic skills, which I think is part of self-knowledge because it allows me to see myself through another’s eyes. Toward the other end of the lifespan, I’d also say in my experience lots of people who are in, or near, retirement have the idea they’re going to stop working and be really happy. But I find in some cases that this expectation is not realistic because so many people find so much fulfillment, and rightly so, in their work. I would urge people to think about what it is that gives them satisfaction? Granted we sometimes find ourselves spitting nails as we think about the challenges our jobs present to us. But in some ways that frequent grumbling, the kind of hair-pulling stress and so forth, these might be part of what makes life fulfilling. More importantly, long-term projects, whether as part of one’s career or post-career, tend I think to provide more intellectual and emotional sustenance than do the more ephemeral activities such as cruises, safaris, and the like.

Q. We’re on a college campus with undergraduates trying to learn more about themselves through what they’re studying. They’re making decisions on what they might want to do with the rest of their life, taking classes like philosophy that encourage them to think about this. Is this an optimal time for this to take place?

A. For many students it’s an optimal time. I consider one component of a liberal arts education to be that of cultivation of the self. Learning a lot of stuff is important, but in some ways that’s just filling, which might be inert unless we give it form, or structure. These things can be achieved through cultivation of the self, and if you want to do that you have to have some idea of how you want it to grow and develop, which requires some inkling of what kind of person you think you are and what you think you can be. Those are achievements that students can only attain by trying things and seeing what happens. I am not suggesting that a freshman should come to college and plan in some rigorous and lockstep way to learn about themselves, cultivate themselves, and bring themselves into fruition as some fully formed adult upon graduation. Rather, there is much more messiness; much more unpredictable try things, it doesn’t work, throw it aside, try something else. In spite of all that messiness and ambient chaos, I would also say in the midst of that there is potential for learning about yourself; taking note of what didn’t go well, what can I learn from that? Or that was really cool, I’d like to build on that experience and do more of it. Those are all good ways of both learning about yourself and constructing yourself. Those two things can go hand-in-hand. Self-knowledge, self-realization, and self-scrutiny can happen, albeit in an often messy and unpredictable way for undergraduates. It’s also illusory for us to think at age 22 we can put on our business clothes and go to work and stop with all that frivolous self-examination. I would urge that acquiring knowledge about yourself, understanding yourself is a lifelong task.

Q. There is the idea that you should learn something new every day. A lot of people who go through college come to understand this, while some think after graduation, I’m done with that. Early in the book, you talk about Socrates’ defense of himself when accused of corrupting students by teaching them in saying: I know what I don’t know, which is why I ask questions.

It seems to me the beginning of wisdom of any kind, including knowledge of ourselves, is acknowledgment of the infirmity of our beliefs and the paucity of our knowledge. — Mitchell S. Green

A. That’s very important insight on his part. That’s something I would be inclined to yell from the rooftops, in the sense that one big barrier to achieving anything in the direction of self-knowledge is hubris, thinking that we do know, often confusing our confidence in our opinions with thinking that confidence is an indication of my degree of correctness. We feel sure, and take that surety itself to be evidence of the truth of what we think. Socrates is right to say that’s a cognitive error, that’s fallacious reasoning. We should ask ourselves: Do I know what I take myself to know? It seems to me the beginning of wisdom of any kind, including knowledge of ourselves, is acknowledgment of the infirmity of our beliefs and the paucity of our knowledge; the fact that opinions we have might just be opinions. It’s always astonishing to me the disparity between the confidence with which people express their opinions, on one hand, and the negligible ability they have to back them up, especially those opinions that go beyond just whether they’re hungry or prefer chocolate over vanilla. Those are things over which you can probably have pretty confident opinions. But when it comes to politics or science, history or human psychology, it’s surprising to me just how gullible people are, not because they believe what other people say, so to speak, but rather they believe what they themselves say. They tend to just say: Here is what I think. It seems obvious to me and I’m not willing to even consider skeptical objections to my position.

Q. You also bring into the fold the theory of adaptive unconscious – that we observe and pick up information but we don’t realize it at the time. How much does that feed into people thinking that they know themselves better than they do and know more than they think they do?

A. It’s huge. There’s a chapter in the book on classical psychoanalysis and Freud. I argue that the Freudian legacy is a broken one, in the sense that while his work is incredibly interesting – he made a lot of provocative and ingenious claims interesting – surprisingly few of them have been borne out with empirical evidence. This is a less controversial view than it was in the past. Experimental psychologists in the 1970s and 80s began to ask how many of those Freudian claims about the unconscious can be established in a rigorous, experimental way? The theory of the adaptive unconscious is an attempt to do that; to find out how much of the unconscious mind that Freud posited is real, and what is it like. One of the main findings is that the unconscious mind is not quite as bound up, obsessed with, sexuality and violence as posited by Freud. It’s still a very powerful system, but not necessarily a thing to be kept at bay in the way psychoanalysis would have said. According to Freud, a great deal with the unconscious poses a constant threat to the well-functioning of civilized society, whereas for people like Tim Wilson, Tanya Chartrand, Daniel Gilbert, Joseph LeDoux, Paul Ekman, and many others, we’ve got a view that says that in many ways having an adaptive unconsciousness is a useful thing, an outsourcing of lots of cognition. It allows us to process information, interpret it, without having to consciously, painstakingly, and deliberately calculate things. It’s really good in many ways that we have adaptive unconscious. On the other hand, it tends to predispose us, for example, to things like prejudice. Today there is a discussion about so-called implicit bias, which has taught us that because we grew up watching Hollywood movies where protagonist heroes were white or male, or both; saw stereotypes in advertising that have been promulgated – that experience, even if I have never had a consciously bigoted, racist, or sexist thought in my life, can still cause me to make choices that are biased. That’s a part of the message on the theory of adaptive unconscious we would want to take very seriously and be worried about, because it can affect our choices in ways that we’re not aware of.

Q. With all of this we’ve discussed, what kind of person would know themselves well?

A. Knowing oneself well would, I suspect, be a multi-faceted affair, only one part of which would have to do with introspection as that notion is commonly understood. One of these facets involves acknowledging your limitations, “owning them” as my Department of Philosophy colleague Heather Battaly would put it. Those limitations can be cognitive – my lousy memory that distorts information, my tendency to sugarcoat any bad news I may happen to receive? Take the example of a professor reading student evaluations. It’s easy to forget the negative ones and remember the positive ones – a case of “confirmation bias,” as that term is used in psychology. Knowing that I tend to do that, if that’s what I tend to do, allows me to take a second look, as painful as it might be. Again, am I overly critical of others? Do I tend to look at the glass as overly half full or overly half empty? Those are all limitations of the emotional kind, or at least have an important affective dimension. I suspect a person who knows herself well knows how to spot the characteristic ways in which she “spins” or otherwise distorts positive or negative information, and can then step back from such reactions, rather than taking them as the last word.

I’d also go back to empathy, knowing how to see things from another person’s point of view. It is not guaranteed to, but is often apt to allow me to see myself more effectively, too. If I can to some extent put myself into your shoes, then I also have the chance to be able to see myself through your eyes and that might get me to realize things difficult to see from the first-person perspective. Empathizing with others who know me might, for instance, help to understand why they sometimes find me overbearing, cloying, or quick to judge.

Q. What would someone gain in self-knowledge by listening to someone appraising them and speaking to them about how well they knew them? How does that dynamic help?

A. It can help, but it also can be shocking. Experiments have suggested other people’s assessments of an individual can often be very out of line with that person’s self-assessment. It’s not clear those other person’s assessments are less accurate – in some cases they’re more accurate – as determined by relatively well-established objective psychological assessments. Third-person assessments can be both difficult to swallow – bitter medicine – and also extremely valuable. Because they’re difficult to swallow, I would suggest taking them in small doses. But they can help us to learn about ourselves such things as that we can be unaccountably solicitous, or petty, or prone to one-up others, or thick-skinned. I’ve sometimes found myself thinking while speaking to someone, “If you could hear yourself talking right now, you might come to realize …” Humblebragging is a case in point, in which someone is ostensibly complaining about a problem, but the subtext of what they’re saying might be self-promoting as well.

All this has implications for those of us who teach. At the end of the semester I encourage my graduate assistants to read course evaluations; not to read them all at once, but instead try to take one suggestion from those evaluations that they can work on going into the next semester. I try to do the same. I would not, however, expect there ever to be a point at which one could say, “Ah! Now I fully know myself.” Instead, this is more likely a process that we can pursue, and continue to benefit from, our entire lives.

Recent Articles

May 23, 2024

Announcing the Provost’s 2024 Alumni Faculty Excellence Awards

Read the article

UConn Law Grad Starts Teaching Fellowship

American Urology Association Honors Dr. Peter Albertsen

- Philosophy and Psychology

The Origin of the Famous Saying "Know Thyself"

The Encyclopedia Of Philosophy

What Is “Know Thyself” By Socrates? A Comprehensive Overview

Have you ever heard the phrase “know thyself”?

It’s a famous quote that has been attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates. But what does it really mean?

Is it just a catchy saying, or is there more to it?

In this article, we’ll explore the concept of “know thyself” and why it’s still relevant today.

We’ll delve into the different interpretations of the phrase and how it can be applied to our modern lives.

So, sit back, relax, and let’s discover what Socrates meant when he said “know thyself.”

What Is Know Thyself By Socrates

Socrates was a philosopher who lived in ancient Greece and is widely regarded as one of the most influential thinkers in Western philosophy. One of his most famous teachings is the phrase “know thyself.”

But what does it mean to know oneself? According to Socrates, it means to have a deep understanding of one’s own beliefs, values, and principles. It means to be aware of one’s own strengths and weaknesses, and to be honest with oneself about them.

Socrates believed that self-knowledge was essential for living a good life. He believed that if we don’t know ourselves, we can’t make good decisions or live in accordance with our true nature.

The Origin Of Know Thyself

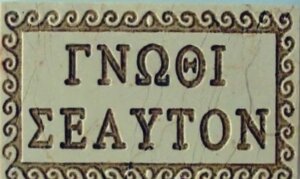

The phrase “know thyself” has its roots in ancient Greece and was inscribed on the forecourt of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, also known as the Oracle of Delphi. Legend has it that the seven sages of ancient Greece, philosophers, statesmen, and law-givers who laid the foundation for Western culture, gathered together in Delphi and encapsulated their wisdom into this command.

The saying was subsequently attributed to a dozen other authors, of which Thales of Miletus most commonly takes the honor. However, it was Socrates and Plato who popularized this phrase and grappled with the mysterious nature of knowledge and identity. Since Greek philosophy laid the foundation for subsequent Western thought, the influence of the Greek command “know thyself” expanded to many other schools of thought, permeating Western philosophical essays and inspirational poetry.

The call to self-knowledge also appears in the East, independently, as far as we can tell, from its Greek emphasis. The Hindu scriptures bring the self into prominence, speaking of its realization as the means to immortality. Along the same vein as Western philosophy, the Hindus claim that man is not naturally born knowing his self and that self-knowledge is a bold and challenging endeavor.

Even farther East, in Imperial China, Confucius draws from the ancient texts of the I-Ching and calls for a system of government based on self-government, which implies self-knowledge. Thus, the call to knowing oneself is universal historically and cannot easily be attributed to a single individual or even a single culture.

Socrates’ Interpretation Of The Phrase

Socrates’ interpretation of the phrase “know thyself” goes beyond just having a general understanding of oneself. He believed that true wisdom comes from recognizing the limits of one’s own knowledge and understanding. In other words, to know oneself means to acknowledge what one does not know.

Socrates argued that people must know themselves before they can claim to know anything else. He believed that ignorance ultimately derived from a lack of self-knowledge, and that by remedying this deficiency, one could gain greater knowledge of oneself and others.

For Socrates, all knowledge must start with the individual and the cultivation of the rational part of their soul. Only then can one acquire knowledge of the world around them, including objects, things, and other people. Socrates believed that knowing oneself was the first step towards wisdom, and that it required courage to persevere, acknowledge failure, and live with the knowledge of one’s own ignorance.

Socrates also believed that knowing oneself meant recognizing one’s true nature as an immortal soul. He argued for the immortality of the soul in his Phaedo dialogue and believed that by knowing oneself as an immortal soul, one could live in accordance with their true nature and make decisions that align with their highest good.

The Importance Of Self-Knowledge

Self-knowledge is important because it allows us to understand our own thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. It provides us with a deeper understanding of our own motivations and desires, which in turn allows us to make better decisions and live more fulfilling lives.

Without self-knowledge, we may be prone to making poor decisions that are not in line with our true nature. We may also struggle to understand why we feel the way we do or why we behave in certain ways. This lack of understanding can lead to feelings of confusion, frustration, and even depression.

Furthermore, self-knowledge is essential for personal growth and self-improvement. By understanding our own strengths and weaknesses, we can work on improving ourselves and becoming the best version of ourselves. We can identify areas where we need to grow and develop new skills or habits that will help us achieve our goals.

In addition, self-knowledge is important for healthy relationships with others. When we know ourselves well, we are better able to communicate our needs and boundaries to others. We are also more empathetic and understanding towards others because we have a greater awareness of our own emotions and experiences.

Applying Know Thyself In Modern Life

In modern life, the concept of “know thyself” is still highly relevant. It means understanding who we are as individuals and what motivates us. It means recognizing our own limitations and knowing when to ask for help.

One way to apply this concept is by practicing self-reflection. This involves taking time to think about our actions, thoughts, and feelings. By doing so, we can gain a deeper understanding of ourselves and our motivations. We can also identify patterns in our behavior that may be holding us back or causing us problems.

Another way to apply “know thyself” is by seeking feedback from others. This can be difficult, as it requires us to be open to criticism and willing to learn from our mistakes. However, it can also be incredibly valuable, as it allows us to see ourselves from a different perspective and identify areas for improvement.

Finally, “know thyself” means being true to ourselves and living in accordance with our values and principles. This may require making difficult decisions or standing up for what we believe in, even if it’s not popular or easy.

Challenges In Achieving Self-Knowledge

Despite the importance of self-knowledge, achieving it is not an easy task. There are several challenges that make it difficult for individuals to truly know themselves.

One challenge is the tendency to deceive ourselves. It’s common for people to have a distorted view of themselves, either by overestimating their abilities or downplaying their flaws. This self-deception can prevent us from seeing ourselves clearly and hinder our ability to make good decisions.

Another challenge is the influence of external factors. Our beliefs and values are often shaped by the society and culture we live in, and it can be difficult to separate our own thoughts and feelings from those that have been imposed on us. This can make it challenging to understand our true selves and what we really want out of life.

Additionally, emotions can cloud our judgment and make it difficult to see ourselves objectively. Fear, anxiety, and other negative emotions can prevent us from confronting our weaknesses and acknowledging our mistakes.

Finally, achieving self-knowledge requires a willingness to be introspective and reflective. It takes effort and courage to examine oneself honestly, and many people may avoid doing so out of fear or discomfort.

Despite these challenges, achieving self-knowledge is possible with practice and dedication. By being honest with ourselves, seeking feedback from others, and engaging in introspection, we can gain a deeper understanding of ourselves and live more fulfilling lives.

Tools And Techniques For Self-Discovery

Knowing oneself is a lifelong journey, and there are many tools and techniques available to help with self-discovery. Here are a few:

1. Self-reflection: Taking the time to reflect on your thoughts, feelings, and actions can help you gain insight into who you are and what you value. Journaling, meditation, and mindfulness practices are all great ways to cultivate self-awareness.

2. Personality assessments: There are many personality assessments available that can help you understand your strengths, weaknesses, and tendencies. These assessments can provide valuable insights into your personality type and how you interact with others.

3. Feedback from others: Sometimes, it can be difficult to see ourselves clearly. Asking for feedback from trusted friends or colleagues can provide a different perspective and help us see ourselves more objectively.

4. Therapy or counseling: Talking to a mental health professional can be a powerful way to gain insight into yourself and your patterns of behavior. A therapist can help you identify areas for growth and provide support as you work through challenges.

5. Mindful self-compassion: Being kind and compassionate toward yourself is an important part of self-discovery. Practicing mindful self-compassion involves treating yourself with the same kindness and care that you would offer to a good friend.

Ultimately, the key to self-discovery is to approach it with curiosity and openness. By being willing to explore our inner selves, we can gain a deeper understanding of who we are and what we want out of life.

Related Posts

Did jesus know about socrates a historical perspective.

Two of the most influential figures in history, one a philosopher and the other a religious leader, have left a lasting impact on the world.…

Read More »

What Did Socrates Discover? A Look Into His Life And Philosophy

In the world of philosophy, few individuals have had as profound an impact as the ancient Greek thinker we know simply as Socrates. Despite never…

How Did Socrates Defend Himself? A Comprehensive Overview

In the world of philosophy, Socrates is a name that is synonymous with wisdom, questioning, and the pursuit of truth. However, he was also a…

Did Socrates Have A Wife? A Look Into The Philosopher’s Personal Life

In ancient Greece, philosophers were revered for their wisdom and intellect. One of the most famous philosophers of all time was Socrates, known for his…

How Did Socrates Think People Should Learn? A Comprehensive Overview

Learning has been a fundamental part of human existence since the beginning of time. From the earliest days of civilization, people have sought to understand…

How To Read Socrates: A Beginner’s Guide

Socrates, the ancient Greek philosopher, is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in Western philosophy. Despite never having written anything down himself,…

About The Author

Bradley Gray

- Corrections

Michel de Montaigne and Socrates on ‘Know Thyself’

‘Know Thyself’ is a popular philosophical dictum. This article explores how Socrates popularized the saying, and how later thinkers like Montaigne interpreted it.

In ancient Delphi, the phrase ‘Know Thyself’ was one of several philosophical sayings allegedly carved over the entrance to the Temple of Apollo. These phrases came to be known as the ‘Delphic maxims’. Clearly ‘Know Thyself’ was influential enough in ancient Greek society to feature so prominently at one of its most revered holy sites. It would later be referenced over a thousand years later by Montaigne in his celebrated Essays. So where did the maxim actually come from?

Socrates on “Know Thyself”

While many people assume that Socrates invented ‘Know Thyself’ , the phrase has been attributed to a vast number of ancient Greek thinkers, from Heraclitus to Pythagoras. In fact, historians are unsure of where exactly it came from. Even dating the phrase’s appearance at Delphi is tricky. One temple of Apollo at Delphi burnt down in 548 BC, and was replaced with a new building and facade in the latter half of the sixth century. Many academics date the inscription to this time period. Christopher Moore believes that the most likely period of its appearance at the temple is between 525 and 450 BC, since this is when “Delphi would have been asserting itself as a center of wisdom” (Moore, 2015).

The fact that we’ve struggled to establish the origins of ‘Know Thyself’ has two major consequences for Socrates’ use of the phrase. First, we’ll never be able to say with certainty how Socrates was reinterpreting the earlier Delphic maxim (since we have no idea when or why it appeared!). Second, we do know that the maxim was hugely important within ancient Greek philosophical circles. Its prominent location at Delphi, home of the famous oracle , means we have to take it seriously.

What Is Self-Knowledge? Some Views on Socratic Self-Knowledge

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

Nevertheless, scholars have interpreted Socrates’ interest in self-knowledge in very different ways. Some academics are dismissive of its value altogether, believing that the ancients held true self-knowledge to be impossible. The soul is the self, and the self is always changing, so how is it possible to ever really ‘know’ oneself? Others claim that the saying is peripheral to Socrates’ wider philosophy.

Not everyone agrees. Various scholars have sought to illustrate how important self-knowledge is to Socrates’ philosophical project . Academics such as M. M. McCabe have argued that Socratic self-knowledge involves a deep examination of one’s principles and beliefs. We must judge ourselves honestly and openly in order to see where we might be flawed in our views. ‘Know thyself’ requires “the courage to persevere, to acknowledge failure, to live with the knowledge of one’s own ignorance” (McCabe, 2011). This is where we begin to see how self-knowledge, when done correctly, can become a tool for self-improvement.

Self-Knowledge: What Are We Actually “Knowing”?

We’ve already seen the word ‘self’ several times in this article. But what does it actually mean? As Christopher Moore points out, “the severe challenge in ancient philosophy is to identify the “self” of self-knowledge” (Moore, 2015). Is a self something universal that everyone possesses? And is it therefore an entity which can be discovered? Or is it something that doesn’t preexist an effort to know it i.e., does it need to be constructed rather than found?

According to Socrates, self-knowledge was a continuous practice of discovery. In Plato’s dialogues , for example, Socrates is portrayed as being dismissive of people who are interested in trying to rationalize things like mythology: “I am not yet able, as the Delphic inscription has it, to know myself; so it seems to me ridiculous, when I do not yet know that, to investigate irrelevant things”.

The self, according to Socrates , is best thought of as a ‘selfhood’ consisting of beliefs and desires, which in turn drive our actions. And in order to know what we believe, we first have to know what is true. Then we can reassess our preconceptions on a given topic once we have established the truth. Of course, this is much easier to say than to actually do! Hence why self-knowledge is portrayed as a continuous practice.

Self-Knowledge and the Importance of Conversation

Socrates was well-known for his love of conversation . He enjoyed asking questions of other people, whether they were philosophers or senators or merchants. Being able to answer a question, and also offering a coherent explanation for one’s answer, is an important component of self-knowledge. Socrates liked to test people’s beliefs, and in doing so try to establish truth about a particular topic.

Sometimes we confuse how certain we are of our opinions with whether they are actually true or not. Socrates pursued conversation because it helps to question why we believe certain things. If we don’t have a good answer to why we are fighting against climate change, for instance, then how can we continue to hold this as a principle? As Moore writes, “Being properly a self involves meaning what one says, understanding how it differs from the other things one could say, and taking seriously its consequences for oneself and one’s conversations” (Moore, 2015). We have to be able to account for our views on the world without recourse to circular reasoning and other weak forms of argumentation, since these things won’t help us to establish truth.

Michel de Montaigne and ‘Know Thyself’

The French Renaissance thinker Michel de Montaigne was another man who believed in the importance of conversation. He was also a proponent of self-knowledge. His entire purpose in writing the Essays, his literary magnum opus, was to try and commit a portrait of himself to paper: “I am myself the subject of this book.” In doing so, he ended up spending the last decades of his life writing and rewriting over a thousand pages of his observations on every topic imaginable, from child-rearing to suicide.

In many ways, Socrates would have approved of this continuous process of self-examination – particularly Montaigne’s commitment to honest and open assessment of one’s selfhood. Montaigne shares his bowel habits and sicknesses with his readers, alongside his changing tastes in wine. He commits his aging body to paper alongside his evolving preferences for philosophers and historians. For example, Montaigne goes through a phase of fascination with Skepticism, before moving on to Stoicism and thus adding in more quotes and teachings from Stoic philosophers to balance out his older Skeptic preferences. All of this revision and reflection helps to create a moving literary self-portrait .

Indeed, the Essays were constantly revised and annotated right up until Montaigne’s death. In an essay entitled “On Vanity” he describes this process thus: “Anyone can see that I have set out on a road along which I shall travel without toil and without ceasing as long as the world has ink and paper.” This is one of many quotes which reveals Montaigne’s belief that true self-knowledge is indeed impossible. Montaigne frequently complains about the difficulties of attempting to properly ‘pin down’ his own selfhood, since he finds that his beliefs and attitudes towards various topics are always changing. Every time he reads a new book or experiences a particular event, his perspective on something might well change.

These attempts at self-knowledge don’t entirely align with Socrates’ belief that we should attempt to seek out truth in order to know what we ourselves believe. For one thing, Montaigne is not convinced that finding even objective truth in the world is possible, since books and theories are constantly being published that contradict one another. If this is true, then what can we ever truly know?

Well, Montaigne is content to believe that knowing thyself is still the only worthy philosophical pursuit. Even though it’s not a perfect process, which seems to evade him constantly, he uses the Delphic maxim ‘Know Thyself’ to argue that in a world full of distractions, we must hold on to ourselves above all else.

Self-Knowledge and Socrates’ ‘Know Thyself’ in Modern Society: Following Montaigne’s Example

Of course, Socrates and Montaigne are not the only thinkers to ponder this phrase. Everyone from Ibn Arabi to Jean-Jacques Rousseau to Samuel Coleridge has explored the meaning and importance of ‘Know Thyself’. Self-knowledge is also explored in non-Western cultures too, with similar principles found in Indian philosophical traditions and even Sun Tzu’s The Art of War .

So how can we begin to use self-knowledge in our everyday lives ? Thinking about who we are can help us to establish what we want, and what kind of person we would like to be in the future. This can be useful from a practical standpoint when making decisions about what to study at university, or which career path to follow.

We can also use self-knowledge to improve how we communicate with other people. Rather than simply believing what we think, without any further scrutiny, we should try and look more deeply at why we think that and be open to testing our assumptions. Analyzing our own opinions in this way can help us to defend our opinions and beliefs more convincingly, and perhaps even persuade other people to join our cause.

‘Know thyself’ has likely been treated as a valuable maxim within human society for thousands of years. Its inclusion on the walls of Apollo’s temple at Delphi cemented its reputation as a useful philosophical maxim . Socrates explored it in more detail and came up with his own interpretation, while thousands of years later, Montaigne attempted to put the aphorism into practice with his Essays. We can draw on these two influential figures to interpret ‘Know thyself’ for, well, ourselves and our own sense of selfhood.

Bibliography

M.M. McCabe, “It goes deep with me”: Plato’s Charmides on knowledge, self-knowledge and integrity” in Philosophy, Ethics and a Common Humanity, ed. by C. Cordner (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011), pp. 161-180

Michel de Montaigne, Les Essais, ed. by Jean Balsamo, Michel Magnien & Catherine Magnien-Simonen (Paris: Gallimard, 2007)

Christopher Moore, Socrates and Self-Knowledge (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015)

Plato, Phaedrus, trans. by Christopher Rowe (London: Penguin, 2005)

Where Was Ancient Greece Located?

By Rachel Ashcroft MSc Comparative Literature, PhD Renaissance Philosophy Rachel is a contributing writer and journalist with an academic background in European languages, literature and philosophy. She has an MA in French and Italian and an MSc in Comparative Literature from the University of Edinburgh. Rachel completed a PhD in Renaissance conceptions of time at Durham University. Now living back in Edinburgh, she regularly publishes articles and book reviews related to her specialty for a range of publications including The Economist.

Frequently Read Together

5 Quotes by Socrates Explained

Heraclitus of Ephesus: The Philosopher of Change (Bio & Quotes)

Oracle of Delphi: Why Was It So Important To Ancient Greeks?

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Self-Consciousness

Human beings are conscious not only of the world around them but also of themselves: their activities, their bodies, and their mental lives. They are, that is, self-conscious (or, equivalently, self-aware). Self-consciousness can be understood as an awareness of oneself. But a self-conscious subject is not just aware of something that merely happens to be themselves, as one is if one sees an old photograph without realising that it is of oneself. Rather a self-conscious subject is aware of themselves as themselves ; it is manifest to them that they themselves are the object of awareness. Self-consciousness is a form of consciousness that is paradigmatically expressed in English by the words “I”, “me”, and “my”, terms that each of us uses to refer to ourselves as such .

A central topic throughout the history of philosophy—and increasingly so since the seventeenth century—the phenomena surrounding self-consciousness prompt a variety of fundamental philosophical and scientific questions, including its relation to consciousness; its semantic and epistemic features; its realisation in both conceptual and non-conceptual representation; and its connection to our conception of an objective world populated with others like ourselves.

1.1 Ancient and Medieval Discussions of Self-Consciousness

1.2 early modern discussions of self-consciousness, 1.3 kantian and post-kantian discussions of self-consciousness, 1.4 early twentieth century discussions of self-consciousness.

- Supplement: Scepticism About Essential Indexicality and Agency

- Supplement: Evans on First Person Thought

- Supplement: The Scope of Immunity to Error Through Misidentification

3.1 Consciousness of the Self

3.2 pre-reflective self-consciousness, 3.3 the sense of ownership, 4.1 self-consciousness and personhood, 4.2 self-consciousness and rationality, 4.3 self-consciousness and consciousness, 4.4 self-consciousness and intersubjectivity, 5.1 mirror recognition, 5.2 episodic memory, 5.3 metacognition, other internet resources, related entries, 1. self-consciousness in the history of philosophy.

A familiar feature of ancient Greek philosophy and culture is the Delphic maxim “Know Thyself”. But what is it that one knows if one knows oneself? In Sophocles’ Oedipus , Oedipus knows a number of things about himself, for example that he was prophesied to kill Laius. But although he knew this about himself, it is only later in the play that he comes to know that it is he himself of whom it is true. That is, he moves from thinking that the son of Laius and Jocasta was prophesied to kill Laius, to thinking that he himself was so prophesied. It is only this latter knowledge that we would call an expression of self-consciousness and that, we may presume, is the object of the Delphic maxim. During the course of the drama Oedipus comes to know himself, with tragic consequences. But just what this self-consciousness amounts to, and how it might be connected to other aspects of the mind, most notably consciousness itself, is less clear. It has, perhaps unsurprisingly, been the topic of considerable discussion since the Greeks. During the early modern period self-consciousness became central to a number of philosophical issues and, with Kant and the post-Kantians, came to be seen as one of the most important topics in epistemology and the philosophy of mind.

Although it is occasionally suggested that a concern with self-consciousness is a peculiarly modern phenomenon, originating with Descartes (Brinkmann 2005), it is in fact the topic of lively ancient and medieval debates, many of which prefigure early modern and contemporary concerns (Sorabji 2006). Aristotle, for example, claims that a person must, while perceiving any thing, also perceive their own existence ( De Sensu 7.448a), a claim suggestive of the view that consciousness entails self-consciousness. Furthermore, according to Aristotle, since the intellect takes on the form of that which is thought (Kahn 1992), it “is thinkable just as the thought-objects are” ( De Anima 3.4.430), an assertion that was interpreted by Aristotle’s medieval commentators as the view that self-awareness depends on an awareness of extra-mental things (Cory 2014: ch. 1; Owens 1988).

By contrast, the Platonic tradition, principally through the influence of Augustine, writing in the fourth and fifth centuries, is associated with the view that the mind “gains the knowledge of [itself] through itself” ( On the Trinity 9.3; Matthews 1992; Cary 2000) by being present to itself. Thus, on this view, self-awareness requires no awareness of outer things. In a similar vein, in the eleventh century, Avicenna argues, by way of his Flying Man thought experiment, that a newly created person floating in a void, with all senses disabled, would nevertheless be self-aware. Thus the self that one cognises cannot be a bodily thing of which one is aware through the senses (Kaukua & Kukkonen 2007; Black 2008; Kaukua 2015). On such views, and in contrast to the Aristotelian picture, basic self-awareness is neither sensory in nature nor dependent on the awareness of other things. This latter claim was accepted by Aquinas, writing in the thirteenth century, who can be seen as synthesising aspects of the Platonic and Aristotelian traditions (Cory 2014). For not only does Aquinas claim that there is a form of self-awareness—awareness that one exists—for which, “the mere presence of the mind suffices”, there is another form—awareness of one’s essence—that, as Aristotle had claimed, is dependent on cognising other things and so for which “the mere presence of the mind does not suffice” ( Summa 1, 87, 1; Kenny 1993: ch. 10).

This ancient and medieval debate concerning whether the mere presence of the mind is sufficient for self-awareness is related to another concerning whether self-awareness is itself sensory in character or, put another way, whether the self is or is not perceptible. Aquinas has sometimes been interpreted as offering a positive answer to this question, sometimes a negative answer (see Pasnau 2002: ch. 11, and Cory 2014: ch. 4, for differing views). These issues were also discussed in various Indian (Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist) debates (Albahari 2006; Siderits, Thompson, & Zahavi 2013; Ganeri 2012a,b), with a variety of perspectives represented. For example, in the writing of the eleventh century Jain writer Prabhācandra, there appears an argument very much like Avicenna’s Flying Man argument for the possibility of self-awareness without awareness of the body (Ganeri 2012a: ch. 2), whereas various thinkers of the Advaita Vendānta school argue that there is no self-awareness without embodiment (Ram-Prasad 2013). There were, therefore, wide-ranging debates in the ancient and medieval period not only about the nature of self-consciousness, but also about its relation to other aspects of the mind, most notably sensory perception and awareness of the body.

Central to the early modern discussion of self-consciousness are Descartes’ assertions, in the second of his Meditations , that “ I am , I exist , is necessarily true whenever it is put forward by me or conceived in my mind” (Descartes 1641: 80), and, in both his Discourse and Principles , that “I think, therefore I am”, or “ cogito ergo sum ” (Descartes 1637: 36, and Descartes 1644: 162; see the discussion of Reflection in the entry on seventeenth century theories of consciousness ). The cogito , which was anticipated by Augustine ( On the Trinity 10.10; Pasnau 2002: ch. 11), embodies two elements of self-awareness—awareness that one is thinking and awareness that one exists—that play a foundational role in Descartes’ epistemological project. As such, it is crucial for Descartes that the cogito is something of which we can be absolutely certain. But whilst most commentators are happy to agree that both “I am thinking” and “I exist” are indubitable, there is a great deal of debate over the grounds for such certainty and over the form of the cogito itself (Hintikka 1962; Wilson 1978: ch. 2, §2; B. Williams 1978: ch. 3; Markie 1992). Of particular concern is the question whether these two propositions are known by inference or non-inferentially, e.g., by intuition, an issue that echoes the medieval debates concerning whether one can be said to perceive oneself.

One philosopher who accepts the former, intuition-based, account is Locke, who claims that

we have an intuitive Knowledge of our own Existence , and an internal infallible Perception that we are. In every Act of Sensation, Reasoning, or Thinking, we are conscious to ourselves of our own Being. (1700: IV.ix.3)

A similar claim can be found in Berkeley’s Three Dialogues (1713: 231–234; Stoneham 2002: §6.4). Further, Locke makes self-consciousness partly definitive of the very concept of a person, a person being “a thinking intelligent Being, that has reason and reflection, and can consider it self as it self, the same thinking thing in different times and places” (1700: II. xxvii.9; Ayers 1991: vol.II, ch.23; Thiel 2011: ch. 4), and self-consciousness also plays an important role in his theory of personal identity (see §4.1 ).

If Descartes, Locke, and Berkeley can be interpreted as accepting the view that there is an inner perception of the self, on this question Hume stands in stark contrast notoriously writing that whilst

there are some philosophers, who imagine we are every moment intimately conscious of what we call our self […] For my part when I enter most intimately into what I call myself , I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. I never can catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe anything but the perception. (Hume 1739–40: bk.1, ch.4, §6; Pitson 2002: ch. 1; Thiel 2011: ch. 12; cf. Lichtenberg’s famous remark that one should not say “I think” but rather, “it thinks”, discussed in Zöller 1992 and Burge 1998)

Hume’s view that there is no impression, or perception, of oneself is crucial to his case for the understanding of our idea of ourselves as nothing more than a “heap or collection of different perceptions” (1739–40: bk.1, ch.4, §6; Penelhum 2000; G. Strawson 2011a), since lacking an impression of the owner of these perceptions we must, in accordance with his empiricist account of concept acquisition, lack an idea of such. It is clear, then, that in the early modern period issues of self-consciousness play an important role in a variety of philosophical questions regarding persons and their minds.

Hume’s denial that there is an inner perception of the self as the owner of experience is one that is echoed in Kant’s discussion in both the Transcendental Deduction and the Paralogisms, where he writes that there is no intuition of the self “through which it is given as object” (Kant 1781/1787: B408; Brook 1994; Ameriks 1982 [2000]). Kant’s account of self-consciousness and its significance is complex, a central element of the Transcendental Deduction being the claim that a form of self-awareness—transcendental apperception—is required to account for the unity of conscious experience over time. In Kant’s words, “the ‘I think’ must be able to accompany all my representations” (Kant 1781/1787: B132; Keller 1998; Kitcher 2011; see the entry on Kant’s view of the mind and consciousness of self ). Thus, while Kant denies that there is an inner awareness of the self as an object that owns its experiences, we must nevertheless be aware of those experiences as things that are, both individually and collectively, our own. The representation of the self in this “I think” is then, according to Kant, purely formal, exhausted by its function in unifying experience.

The Kantian account of self-awareness and its relation to the capacity for objective thought set the agenda for a great deal of post-Kantian philosophy. On the nature of self-awareness, for example, in an unpublished manuscript Schopenhauer concurs with Kant, asserting that, “that the subject should become an object for itself is the most monstrous contradiction ever thought of” (quoted in Janaway 1989: 120). Further, a philosophical tradition stemming from Kant’s work has tried to identify the necessary conditions of the possibility of self-consciousness, with P.F. Strawson (1959, 1966), Evans (1980, 1982), and Cassam (1997), for example, exploring the relation between the capacity for self-conscious thought and the possession of a conception of oneself as an embodied agent located within an objective world (see §4.3 ). Another, related tradition has argued that an awareness of subjects other than oneself is a necessary condition of self-consciousness (see §4.4 ). Historical variations on such a view can be found in Fichte (1794–1795; Wood 2006), Hegel (1807; Pippin 2010), and, from a somewhat different perspective, Mead (1934; Aboulafia 1986).

Fichte offers the most influential account of self-consciousness in the post-Kantian tradition. On the reading of the “Heidelberg School”, Fichte claims that previous accounts of self-consciousness given by Descartes, Locke, and even Kant are “reflective”, regarding the self as taking itself not as subject but as object (Henrich 1967; Tugendhat 1979: ch. 3; Frank 2004; Zahavi 2007). But this reflective form of self-awareness, Fichte argues, presupposes a more primitive form since it is necessary for the reflecting self to be aware that the reflected self is in fact itself . Consequently, according to Fichte, we must possess an immediate acquaintance with ourselves, “the self exists and posits its own existence by virtue of merely existing” (Fichte 1794–1795: 97). Once more, this debate echoes ancient discussions concerning the nature and role of self-consciousness.

In the early twentieth century, Frege suggests a form of self-acquaintance, claiming that “everyone is presented to himself in a special and primitive way” (Frege 1918–1919: 333). In a similar vein, in early work Russell (1910) favours the idea that we are acquainted with ourselves, but by the 1920s (1921: 141) he seems to endorse a view more in line with Hume’s sceptical account. The same can be said of the Wittgenstein of the Tractatus , who famously likens the self to the eye which sees but does not see itself (Wittgenstein 1921: 5.6–5.641; O’Brien 1996; Sullivan 1996). Husserl’s philosophical development seems to have taken the opposite trajectory to that of Russell, with his (1900/1901, Investigation V, §8) denial of the inner awareness of a “pure ego” being subsequently revised into something resembling Kantian transcendental apperception (Husserl 1913: §57; Carr 1999: ch. 3; Zahavi 2005: ch. 2). Continuing with the phenomenological tradition, Sartre (1937; Priest 2000) takes Husserl’s later view to task, arguing against the view that we are continually aware of a transcendent ego, yet in favour of the picture of consciousness as involving a “pre-reflective” awareness of itself reminiscent of the Heidelberg School view (Wider 1997: ch. 3; Miguens, Preyer, & Morando 2016). Questions about the nature of self-consciousness and, in particular, over whether there is an immediate, or intuitive, consciousness of the self, were as lively as ever well into the twentieth century.

2. Self-Consciousness in Thought

One natural way to think of self-consciousness is in terms of a subject’s capacity to entertain conscious thought about herself. Self-conscious thoughts are thoughts about oneself. But it is commonly pointed out that thinking about what merely happens to be oneself is insufficient for self-consciousness, rather one must think of oneself as oneself . If one is capable of self-conscious thought, that is, one must be able to think in such a way that it is manifest to one that it is oneself about whom one is thinking.

It is widely recognised that the paradigmatic linguistic expression of self-consciousness in English is the first-person pronoun “I”; a term with which one might be said to refer to oneself as oneself (Sainsbury 2011). Plausibly, every utterance of a sentence containing “I” is expressive of a self-conscious “I-thought”, that is a thought containing the first-person concept. Thus, discussions of self-consciousness are often closely associated with accounts of the semantics of the indexical term “I” and the nature of its counterpart first-person concept (e.g., Anscombe 1975; Perry 1979; Nozick 1981: ch. 1, §2; Evans 1982: ch. 7; Mellor 1989; O’Brien 1995a; Castañeda 1999; de Gaynesford 2006; Recanati 2007; Rödl 2007: ch. 1; Bermúdez 2016).

As Castañeda (1966; cf. Anscombe 1975) points out, there is an ambiguity in certain ascriptions of belief containing “he” or “she”. I may say “Jane believes that she is F ” without implying that Jane realises that it is herself that she believes to be F . That is, there is a reading of “Jane believes that she is F ” that does not imply self-consciousness on Jane’s part. But, in some cases, we do intend to attribute self-consciousness with that same form of words. To resolve this ambiguity, Castañeda introduces “she*” for self-conscious attributions. I will use the more natural indirect reflexive “she herself”. Thus, “Jane believes that she is F ” does not imply that Jane self-consciously believes that she is F , whilst “Jane believes that she herself is F ” does. Before the dreadful revelation, Oedipus believed that he was prophesied to kill his father, but did not believe that he himself was so prophesied.

2.1 The Essential Indexical

First-personal language and thought is commonly taken to be sui generis , irreducible to language or thought not containing the first-person pronoun or corresponding concept (Castañeda 1966, 1967; Perry 1977, 1979, 2001). Arguments for this view have typically appealed to the essential role seemingly played by the first-person in explanations of action. This point is supported by a number of well-known examples. Consider Perry’s case of the messy shopper,

I once followed a trail of sugar on a supermarket floor, pushing my cart down the aisle on one side of a tall counter and back the aisle on the other, seeking the shopper with the torn sack to tell him he was making a mess. With each trip around the counter, the trail became thicker. But I seemed unable to catch up. Finally it dawned on me. I was the shopper I was trying to catch. (Perry 1979: 33)

As Perry points out, he knew all along that the shopper with the torn sack was making a mess. He may also have believed that the oldest philosopher in the shop (in fact himself) was making a mess, yet failed to check his own cart since he falsely believed that Quine was at the Deli Counter. Indeed, it seems that for any non-indexical term a that denotes Perry, it is possible for Perry to fail to believe anything naturally expressed by the sentence “I am a ”. If so, it is possible for Perry to rationally believe that a is making a mess without believing anything that he would express as “I am making a mess”. It was only when Perry came to believe that he himself was making a mess that he stopped the chase. Indeed, it would seem that only the first-personal content can provide an adequate explanation of Perry’s behaviour when he stops. If Perry had come to believe that John Perry is making a mess then, unless he also believed that he himself was John Perry, he would not have stopped. The first-personal content is “self-locating”, thereby enabling action, whereas the non-first-personal content is not. To use Kaplan’s (1977) example, if I believe that my pants are on fire, pure self-interest will surely motivate me do something about it. If, however, I believe that Smith’s pants are on fire, pure self-interest will only so motivate me if I also believe that I am Smith.

On this widely accepted picture, then, first-personal thought and language is irreducible to non-first-personal thought and language, and is essential to the explanation of action (Kaplan 1977: 533; D. Lewis 1979; McGinn 1983: ch. 6; Recanati 2007: ch. 34; Musholt 2015: ch. 1; Prosser 2015; García-Carpintero & Torre 2016). Importantly, on Perry’s view, what is irreducible is the first-personal way of thinking about ourselves, not the facts or states of affairs that make such thoughts true. So, whilst my belief “I am F ” is not equivalent to any non-first-personal belief, it is true if and only if Smith is F , this being the same fact that makes true the non-first-personal “Smith is F ”. Thus, whilst first-person representations are special, a special class of first-person facts are nowhere to be found (for views that do accept the existence of first-personal facts, see McGinn 1983; Baker 2013; also see Nagel 1986).

Perry (1977, 1979) argues that terms such as “I” which are, as he puts it, “essentially indexical”, pose a problem for the traditional Fregean view of belief as a two-place relation between a subject and a proposition (cf. Spencer 2007). Fregean senses are, according to Perry, descriptive and as Perry has argued no description is equivalent to an essential indexical. Consequently, no Fregean proposition can be the thing believed when one believes first-personally. Essential indexicality, if somehow forced into the Fregean mould, means that we must implausibly accept that there are incommunicable senses that only the speaker (or thinker) is in a position to grasp (see García-Carpintero & Torre 2016); cf.Evans 1981; Longworth 2013). D. Lewis goes further than this, arguing, partly on the basis of his much discussed Two Gods example (1979), in which each God knows all the propositions true at their world yet fails to know which of the two Gods he himself is, that the objects of belief are not propositions at all but rather properties (or centred worlds). That is, since they already know all the true propositions, there is no true proposition the Gods would come to believe when they come to realise which God they are. Essential indexicality forces us away from the model of propositions as the objects of belief. Further, Lewis claims that not just the explicitly indexical cases, but all belief is in this way self-locating or, in his terminology, de se . On this account, every belief involves the self-ascription of a property and so, arguably, is an instance of self-consciousness (for discussion, Gennaro 1996: ch. 8; Stalnaker 2008: ch. 3; Feit 2008; Cappelen & Dever 2013: ch. 5; Magidor 2015).

Arguments such as Perry’s might be challenged on the grounds that it is not possible to rationally doubt that one is the subject of these conscious states , where that formulation involves an “introspective demonstrative” picking out one’s current conscious states. This, it might be claimed, constitutes a reduction of first-person content (cf. Peacocke 1983: ch. 5, although his goal is not reductive). Even if it is true, however, that one cannot doubt that one is the subject of these conscious states, it is not clear that this poses a significant challenge to Perry’s argument for the essential indexicality of the first-person. For one thing, the content itself contains a demonstrative, so indexical, element. Second, it has been argued that our capacity to refer to our own experiences itself depends on our capacity to refer to ourselves as ourselves (P.F. Strawson 1959: 97; Evans 1982: 253). That is, to think of these conscious states is to think of them as these conscious states of mine . If to demonstratively think of one’s conscious state is, necessarily, to think of it as one’s own conscious state, then the purported reduction of first-person thought to thought not containing the first-person will fail.

Cappelen and Dever (2013) present a sustained attack on the constellation of philosophical claims surrounding the “essential indexical”, including its purported relation to action, and both Perry’s and Lewis’s arguments for it (for an alternative objections to Perry and Lewis, see Millikan 1990; Magidor 2015). A central element in their critique is the claim that cases, such as Perry’s shopper, that are often thought to show the special connection between self-consciousness (I-thoughts) and the capacity for action really only show that action explanation contexts do not allow for substitution salva veritate , but rather are opaque (Cappelen & Dever 2013: ch. 3). Just as, if I am at the airport waiting for Jones, I will only signal that man if I believe him to be Jones, so if I am looking for the shopper with the torn sack I will only stop when I believe that I am that shopper. On their view, despite the popularity of the view to the contrary, the capacity for self-consciousness does not possess any philosophically deep relation to the capacity for action. See the supplement: Scepticism About Essential Indexicality and Agency .

2.2 First-Person Reference

Because of its connection with the first-person pronoun, it is often taken as platitudinous to say that self-conscious thought is closely associated with the capacity to refer to oneself as oneself . When I think self-consciously, I cannot fail to refer to myself. More than this, it has often been claimed that for a central class of first-person thoughts, there is no possibility of misidentifying myself: not only can I not fail to pick myself out, I cannot take another person to be me. But first-person reference, and indexicality more generally, has sometimes been thought to pose a challenge to theories of reference, requiring special treatment. Indeed, some have argued that the platitude itself should be rejected.

Terms whose function it is to refer can, on occasion, fail in that function. A use of the term “Vulcan” to refer to the planet orbiting between Mercury and the sun, fails to refer to anything for the reason that there is nothing for it to refer to. If I see the head of one dachshund protruding from behind a tree and the rear end of another protruding from the other side of the tree, and utter “that dog is huge”, my use of “that dog” has arguably failed to refer due to there being too many objects. It would seem that, by contrast, the term “I” cannot fail to refer either by there being too few or too many objects. “I” is guaranteed to refer.

As an indexical, the referent of “I” varies with the context of utterance (see the entry on indexicals ). That is, “I” refers to different people depending on who utters it. Following Kaplan (1977), it is common to think of the meaning of such terms as determining a function from context to referent. In the case of “I”, a natural proposal is the “Self-Reference Rule” (SRR), that the referent of a token of “I” is the person that produces it (Kaplan 1977: 491; Campbell 1994: ch. 3). “I” is thus, unlike “this” or “that”, a pure indexical, seemingly requiring no overt demonstration or manifestation of intention (Kaplan 1977: 489–91). SRR captures the plausible thought that “I” is guaranteed against reference failure. Since every token of “I” has been produced, the fact that “I” refers to its producer means that there is no chance of its failing to pick out some entity. This account of “I”, then, treats it as not only expressive of self-consciousness, but also guaranteed to refer to the utterer.

SRR is Kaplan’s specification of the character of “I”, which is fixed independently of the context of any particular utterance. This character is to be distinguished from the content of a tokening of “I”, which it has only in a context. On Kaplan’s account, the content of an utterance of “I am F ” will be a singular proposition composed of the person that produced it and F ness (Recanati 1993; for an account that attributes to the utterance both singular content, and the “reflexive content” the speaker of this token is F , see Perry 2001; for an alternative “Neo-Fregean” account in terms of object-dependent de re senses, see Evans 1981; cf. McDowell 1977; and Evans 1982: ch. 1).

Intuitively plausible as it is, SRR is open to a number of potential counterexamples. Suppose, for example, that you are away from work due to illness and I leave a note on your door reading “I am not here now”. Plausibly, whilst it was me that produced this token of “I”, it nevertheless refers to you . Or consider a situation in which I walk into a petrol station, point to my car, and say “I’m empty”. In this case, it might be suggested, my use of “I” refers to my car rather than myself (for these and related cases, see Vision 1985; Q. Smith 1989; Sidelle 1991; Nunberg 1993, 1995). If so, SRR cannot specify the character of “I” and so, arguably, some tokens of “I” fail to express the self-conscious thoughts of those that produce them. In light of such cases, a variety of alternatives to SRR have been proposed. Q. Smith (1989) suggests that “I” is lexically ambiguous; Predelli (1998a,b, 2002) offers an intention-based reference rule for “I”; Corazza, Fish, and Gorvett (2002) offer a convention-based account; and Cohen (2013) argues that the cases can be handled by a conservative modification of Kaplan’s original proposal (also see, Romdenh-Romluc 2002, 2008; Corazza 2004: ch. 5; Dodd & Sweeney 2010; Michaelson 2014).

Although she didn’t have Kaplan’s formulation of SRR in mind, an earlier criticism of such a rule can be found in the work of Anscombe (1975) who argues that the rule cannot be complete as an account of the meaning of “I” (for discussion see O’Brien 1994). Anscombe considers a world in which each person has two names, one of which (ranging from “B” to “Z”) is printed on their chest, the other (in every case “A”) is printed on the inside of their wrist. Each person uses “B” to “Z” when attributing actions to others, but “A” when describing their own actions (Anscombe 1975: 49). Anscombe argues that such a situation is compatible with the possibility that the people in question lack self-consciousness. Whilst B uses “A” to refer to B, C uses “A” to refer to C, and so on, there is no guarantee that they are thinking of themselves as themselves , for they may be reporting what are in fact their own actions without thinking of those actions as things that they themselves are performing. They may treat themselves, that is, just as the treat any other. This is despite the fact that, in this scenario, “A” complies with SRR.

Can the Self-Reference Rule be reformulated in such a way as to entail self-consciousness on the part of those who use terms that comply with it? According to Anscombe it can, but any such reformulation will presuppose a prior grasp of self-conscious reference to oneself. For example, if we say, employing the indirect reflexive, that “I” is a term that a person uses to refer to she herself , we have travelled in a tight circle since “she herself” can be understood only in terms of “I” (Anscombe 1975; Castañeda 1966; for discussion, see Bermúdez 1998: ch. 1). This can be seen clearly in the first-person formulation of such a rule: “I” is a term that I use to refer to myself . For here the “myself” must itself be understood as an expression of self-consciousness, i.e., we should really say that “I” is a term that I use to refer to myself as myself .

In response to Anscombe’s argument, it has been argued that SRR is not intended to explain the connection between self-consciousness and the first-person (O’Brien 1994, 1995a; Garrett 1998: ch. 7; cf. Campbell 1994: §4.2; Peacocke 2008: §3.1). On this view, all that the example of “A” users shows is that self-consciousness has not been fully accounted for by SRR, not that SRR fails as an account of the character of “I”. Kaplan himself, however, does appear to be more ambitious than this, claiming that the “particular and primitive way” in which each of us is presented to ourselves is simply that each “is presented to himself under the character of "I"” (Kaplan 1977: 533). This claim, it would seem, is indeed open to Anscombe’s challenge.

Anscombe’s (1975) paper is perhaps most notable for her claim that “I” is not a referring expression at all. Assuming that if “I” refers it must be understood on the model of either a proper name, a demonstrative, or an abbreviation of a definite description, Anscombe argues that each of these kinds of referring expression requires what she calls a “conception” by means of which it reaches its referent. This conception must explain the seemingly guaranteed reference of “I”: the apparent fact that no token of “I” can fail to pick out an object. However, she argues, no satisfactory conception can be specified for “I” since either it fails to deliver up guaranteed reference, or it succeeds but only by delivering an immaterial soul. Since we have independent reason to believe that there are no immaterial souls, it follows that “I” cannot be understood on the model of a proper name, demonstrative or definite description, so is not a referring expression (see Kenny 1979 and Malcolm 1979 for positive appraisals of Anscombe’s position. Criticisms can be found in White 1979; Hamilton 1991; Brandom 1994: 552–561; Glock & Hacker 1996; McDowell 1998; Harcourt 2000).

That “I” does not function as either a name or an abbreviated definite description is widely accepted. The more contentious aspect of Anscombe’s case for the view that there is no appropriate conception for “I” is her claim that “I” does not function like a demonstrative. Her argument for this claim is highly reminiscent of Avicenna’s Flying Man argument (see §1.1 ), with which she was surely familiar. We can, she tells us, imagine a subject in a sensory deprivation tank who has been anaesthetised and is suffering from amnesia. Such a subject would, claims Anscombe, be able to think I-thoughts, perhaps wondering, “How did I get into this mess?”. Since such a subject can think self-consciously in the absence of any presented referent, it follows that “I” cannot mean something like “this person”, since demonstratives require the demonstrated object to be presented to conscious awareness. Treating “I” on a demonstrative model, then, fails (cf. Campbell 1994: §4.2; O’Brien 1995b; see Morgan 2015 for a defence of a demonstrative account).

According to Evans (1982: ch. 7), the problem with Anscombe’s argument is that it fails to appreciate that “I” can be modelled on “here” rather than “this”. According to Evans’ account, the similarity between what he calls “I”-Ideas and “here”-Ideas shows up in their functional role (for an alternative broadly functional account, see Mellor 1989; for an argument that, far from being amenable to a functional analysis, self-consciousness poses a threat to the coherence of functionalism, see Bealer 1997). Once we see how both “I”-Ideas and “here”-Ideas stand at the centre of distinctive networks of inputs (ways of gaining information about ourselves and our locations respectively) and outputs (including the explanation of action), we can see how to model “I” on “here”, thus escaping Anscombe’s argument. For further discussion, see the supplement: Evans on First Person Thought .

2.3 Immunity to Error Through Misidentification

In The Blue and Brown Books , Wittgenstein distinguishes between two uses of the term “I” which he calls the “use as subject” and the “use as object” (1958: 66–70; Garrett 1998: ch. 8; cf. James’ distinction between the I , or pure ego, and the me , or empirical self (1890: vol. 1, ch. X)). As Wittgenstein describes the difference, there is a certain kind of error in thought that is possible when “I” is used as object but not when “I” is used as subject. Wittgenstein notes that if I find myself in a tangle of bodies, I may wrongly take another’s visibly broken arm to be my own, mistakenly judging “I have a broken arm”. Upon seeing a broken arm, then, it can make sense to wonder whether or not it is mine. If, however, I feel a pain in the arm, and on that basis judge “I have a pain”, then it makes no sense at all for me to wonder whether the pain of which I am aware is mine. That is, it is not possible for me to be aware, in the ordinary way, of a pain in an arm but mistakenly judge it to be my own arm that hurts. On this picture, self-ascriptions of pain, at least when based on the usual introspective grounds, involve the use of “I” as subject and so are immune to this sort of error of misidentification.

Immunity to this sort of error should not be conflated with another sort of epistemic security that is often discussed under the heading of self-knowledge (see entry on self-knowledge ). Some philosophers have held that, for a range of mental states, one cannot be mistaken about whether one is in them. Thus, for example, if one sincerely judges that one has a pain, or that one believes that P, then it cannot turn out that one is not in pain, or that one does not so believe. That the kind of immunity to error described by Wittgenstein differs from this sort of epistemic security follows from the fact that one may be sceptical of the latter while accepting the former. That is, one may reject the claim that sincere judgements that one has a pain cannot be mistaken (perhaps it is possible to mistake a sensation of coldness for one of pain), whilst nevertheless maintaining that if one is introspectively aware of a pain, then that pain must be one’s own. Immunity to errors of this sort has been taken, by a number of philosophers, to be importantly connected to self-consciousness.

Under the influence of Shoemaker (1968) this phenomenon has become known as immunity to error through misidentification relative to the first-person pronoun, or IEM. On Shoemaker’s formulation, an error of misidentification occurs when one knows some particular thing, a , to be F and judges that b is F on the grounds that one mistakenly believes that a is identical to b . To this it is important to add that IEM is not a feature that judgements possess in virtue of their content alone but only relative to certain grounds (perception, testimony, introspection , memory , etc.). Thus, the judgement that I am jealous of a might be IEM when grounded in introspection, but not when grounded in the overheard testimony of my analyst. For I may have misinterpreted my analyst’s words, wrongly taking his use of “Smith” in “Smith is Jealous of a ” to refer to me (“Smith” after all is a common name). IEM is always relative, then, to the grounds on which a judgement is based. Which grounds might give rise to first-person judgements that are IEM is a contested matter, see the supplement: The Scope of Immunity to Error Through Misidentification .