[Course of borderline personality disorder: literature review]

Affiliation.

- 1 EA 4057, laboratoire de psychopathologie et neuropsychologie cliniques, institut de psychologie, université Paris-Descartes, 71, boulevard Édouard-Vaillant, 92774 Boulogne-Billancourt, France. [email protected]

- PMID: 21035627

- DOI: 10.1016/j.encep.2009.12.009

Introduction: Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a serious mental disorder associated with severe emotional, behavioral, cognitive and interpersonal dysfunction, extensive functional impairment and frequent self-destructive behaviour, including deliberate self-harm and suicidal behaviour. For quite some time, BPD has been viewed as a chronic disorder and borderline patients as extremely difficult to treat, doomed to a life of misery. However, those views are changing and there is an increasing recognition that BPD has a far more benign course than previously thought. The purpose of this study is to show how those views changed over time by reviewing longitudinal studies of the course of BPD.

Methods: We have reviewed the literature published from 1968 to March 2009, using the following key words: borderline personality disorder, outcome, follow-up studies with some additional references.

Results: The aim of the longitudinal studies conducted prior to the DSM definition of BPD criteria was to determine whether borderline patients could become psychotic over time, but no such evidence was found even though their functioning was at a relatively low level. The studies conducted after the introduction of BPD in the DSM in 1980 tested the stability and the specificity of BPD diagnosis, concluding that the criteria were relatively stable in the short run since the majority of patients continued to meet them at the follow-up assessments. However, those studies had many methodological drawbacks which limited their generalizability such as small sample sizes, high attrition rates, the absence of comparison groups, etc. Four retrospective studies of the 15-year outcome of borderline patients obtained virtually identical results despite methodological differences, showing that the global functioning of borderline patients improved substantially over time with mean scores of the GAF scale falling within a mild range of impairment. One 27-year retrospective study showed that borderline patients continued to improve as they grew older, only 8% of the cohort still meeting criteria for BPD. Two recent carefully designed prospective studies showed that the majority of BPD patients experienced a substantial reduction in their symptoms far sooner than previously expected. After six years, 75% of patients diagnosed with BPD severe enough to be hospitalized achieve remission by standardized diagnostic criteria and after 10 years, the remission rate raises up to 88%. Recurrences are rare, no more than 6% over six years. The dramatic symptoms (suicidal behaviour, self-mutilation, queasy psychotic thoughts) resolve relatively quickly, but abandonment concerns, feeling of emptiness and vulnerability to dysphonic states is likely to remain in at least half the patients.

Discussion: This contrasts with the natural course of many Axis I disorders, such as mood disorders, where improvement rates may be somewhat higher and more rapid but recurrences are more frequent. The findings of longitudinal studies raise doubts about the validity of the definition in the DSM, which implies that personality disorders must necessarily be chronic. However, it should be noted that even the most encouraging findings do not show full recovery since the majority of patients seem to suffer from some residual symptoms.

Conclusion: These findings have very important clinical implications and borderline patients should be told that they can expect improvement, no matter how intense their current emotional pain. However, we still lack evidence-based findings on mechanisms that lie behind the recovery process in BPD. Future research should explore the mechanisms of recovery in BPD.

Copyright © 2010 L'Encéphale, Paris. Published by Elsevier Masson SAS. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- English Abstract

- Borderline Personality Disorder / diagnosis*

- Borderline Personality Disorder / psychology

- Borderline Personality Disorder / therapy

- Chronic Disease

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- Hospitalization

- Interpersonal Relations

- Longitudinal Studies

- Retrospective Studies

- Self-Injurious Behavior / diagnosis

- Self-Injurious Behavior / psychology

- Self-Injurious Behavior / therapy

- Suicidal Ideation

- Treatment Outcome

- Young Adult

MINI REVIEW article

Personality disorders in people with epilepsy: a review.

- 1 Department of Biomedical and NeuroMotor Sciences, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

- 2 IRCCS Istituto delle Scienze Neurologiche di Bologna, Epilepsy Center (full member of the European Reference Network EpiCARE), Bologna, Italy

- 3 Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Milano Bicocca, Milan, Italy

Epileptologists and psychiatrists have long observed a correlation between epilepsy and personality disorders (PDs) in their clinical practice. We conducted a comprehensive PubMed search looking for evidence on PDs in people with epilepsy (PwE). Out of over 600 results obtained without applying any time restriction, we selected only relevant studies (both analytical and descriptive) limited to English, Italian, French and Spanish languages, with a specific focus on PDs, rather than traits or symptoms, thus narrowing our search down to 23 eligible studies. PDs have been investigated in focal epilepsy (predominantly temporal lobe epilepsy - TLE), juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) and psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES), with heterogeneous methodology. Prevalence rates of PDs in focal epilepsy ranged from 18 to 42% in surgical candidates or post-surgical individuals, with Cluster C personality disorders or related traits and symptoms being most common. In JME, prevalence rates ranged from 8 to 23%, with no strong correlation with any specific PDs subtype. In PNES, prevalence rates ranged from 30 to 60%, with a notable association with Cluster B personality disorders, particularly borderline personality disorder. The presence of a PD in PwE, irrespective of subtype, complicates treatment management. However, substantial gaps of knowledge exist concerning the neurobiological substrate, effects of antiseizure medications and epilepsy surgery on concomitant PDs, all of which are indeed potential paths for future research.

Introduction

Epilepsy is a chronic disease of the brain defined as “an enduring predisposition to generate epileptic seizures, and by the neurobiologic, cognitive, psychological, and social consequences of this condition” ( 1 ). It is a common neurological disease, with a calculated incidence rate of 61.4 per 100,000 person-years and a prevalence of 7.60 per 1,000 population ( 2 ), it affects approximately 46 million people, therefore representing a significant fraction of the worldwide disease burden ( 3 ). Remarkably, nearly half of people with epilepsy (PwE) experience comorbidities, with certain conditions exhibiting a higher prevalence among PwE compared to the general population, often impacting on epilepsy prognosis itself ( 4 ). Psychiatric disorders have garnered particular attention, due to their association with poor seizure outcome, drug-resistance, heightened suicide risk ( 5 – 7 ). While extensive research has been devoted to psychotic, anxiety and mood disorders, limited attention has been directed to the relationship between epilepsy and personality disorders (PDs). This neglect is somewhat surprising given historical observations dating back to the last century, originating from studies involving institutionalized PwE. Several clinical conditions have been described, such as Geschwind syndrome ( 8 ), gliscroid personality or Blumer syndrome ( 9 ). These data were not universally supported or agreed upon ( 10 ) and were related, in particular, to the presence of temporal lobe epilepsies (TLE) with drug-resistant seizures, social isolation, and the use of certain medications, such as phenobarbital or bromine. Subsequent studies showed that other types of epilepsy, such as the Idiopathic Generalized Epilepsies (IGE), showed very different personological characteristics from those described for TLE ( 11 ). Features such as superficiality, tendency to elation, poor compliance and critical traits were noted, often attributed to frontal lobe involvement ( 11 ). However the debate about the existence of personological alterations during epilepsy has waned in subsequent years, partly in connection with the use of medications with less impact on cognitive function and with the improved social integration of PwE, so much so that the Commission on Epilepsy, Risks and Insurance of the International Bureau for Epilepsy regarded the risk for psychological disorders in epilepsy to be negligible, at least when considered as such ( 12 ). Furthermore, the emergence of a revised classification system both for epilepsies and for personality disorders (DSM-5) has provided more rigorous and precise definitions, warranting a reevaluation of the association between epilepsy and PDs. In light of these developments, it is imperative to revisit the nexus between epilepsy and PDs, incorporating contemporary scientific evidence and examining diverse populations.

Our review focuses specifically on PDs in PwE, with the aim to collect and synthesize existing evidence, identify gaps of knowledge and propose potential avenues for future research.

Material and methods

In November 2023 we performed a search on PubMed database using the following terms: “Epilepsy”[Mesh] AND [“personality disorder”(All Fields) OR “paranoid personality disorder” (MeSH) OR “schizoid personality disorder” (Mesh) OR “schizotypal personality disorder” (MeSH) OR “antisocial personality disorder” [MeSH] OR “borderline personality disorder “(MeSH) OR “histrionic personality disorder” (MeSH) OR “narcissistic personality disorder” (All Fields) OR “avoidant personality disorder” (All Fields) OR “dependent personality disorder” (Mesh) OR “obsessive compulsive disorder” (MeSH)].

We selected studies (both descriptive and analytical) written in English, Italian, French and Spanish investigating the prevalence of personality disorders in PwE. Exclusion criteria were reviews, case reports, case series with small populations (i.e. less than 10 patients) and editorial comments. Additionally, studies emphasizing personality traits or symptoms without a formal diagnosis of personality disorder were excluded. Studies focusing on personality traits or symptoms without a diagnosis of personality disorder were excluded. No time restrictions were applied, and the entire selection process was carried out manually without the use of any automated tool.

The identified references were screened and provisionally selected for inclusion on the basis of title and abstract, when available. The full texts of articles meeting the inclusion criteria were then assessed.

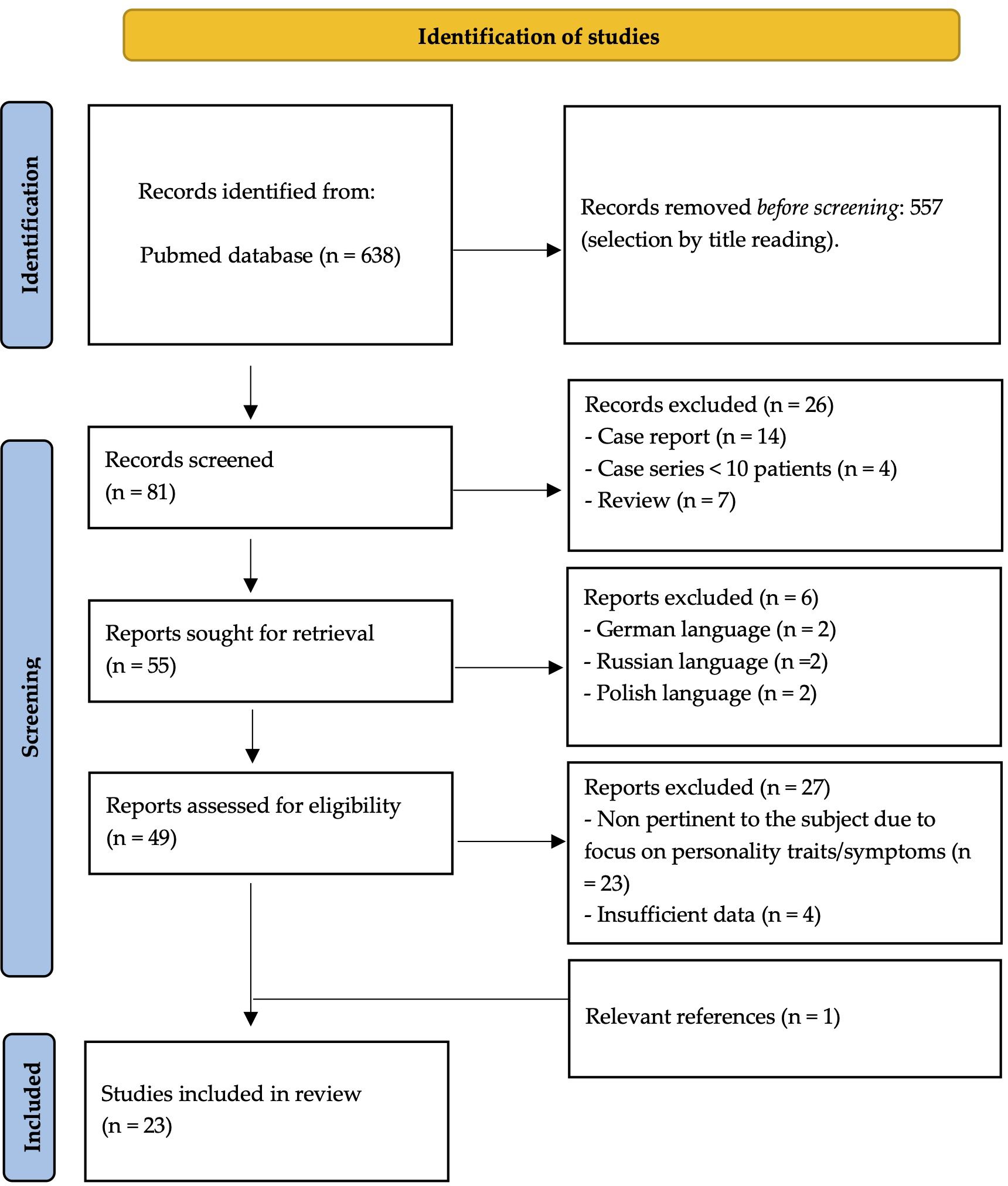

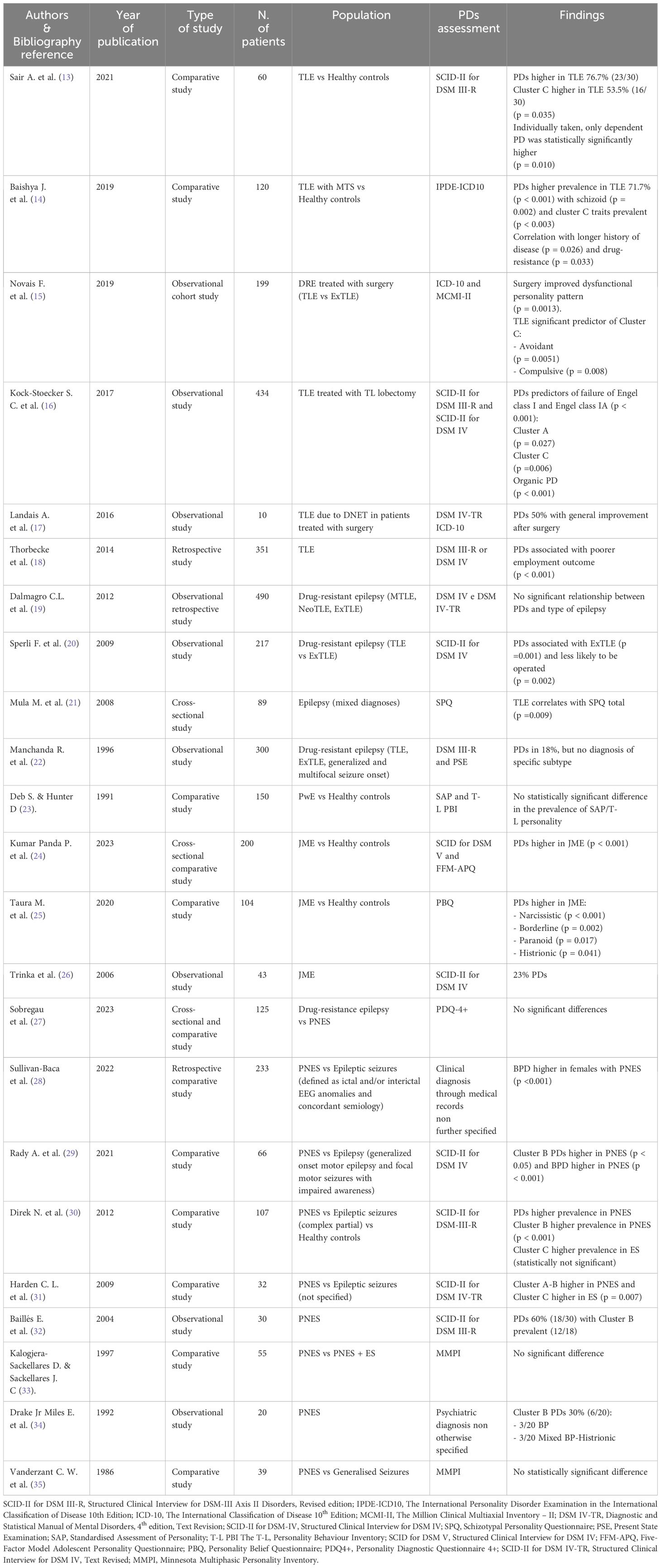

The initial PubMed search yielded a total of 638 articles. Following a multi-step selection process, 23 studies met the inclusion criteria and were considered eligible for analysis (see Figure 1 for further details). The findings of these studies are presented in distinct subchapters, according to the main themes investigated (see Table 1 ).

Figure 1 Detailed multi-step process for source identification.

Table 1 Results.

Personality disorders and focal epilepsy

Among the included studies, eleven investigated the relationship between PDs and focal epilepsy. These studies showed a significant prevalence of PDs within the studied population, with the strongest association observed between TLE and Cluster C PDs ( 13 – 15 ) and, to a lesser extent, between TLE and schizotypal personality ( 21 ).

Several studies investigated PDs in people with focal epilepsy who underwent epilepsy surgery, investigating its impact on both medical conditions. Notably, one study reported a statistically significant improvement in pre-surgical PD symptoms, although details on seizure outcomes were not provided ( 15 ). In another work, surgical resection of the epileptogenic zone led to remarkable improvements in all five patients diagnosed with concomitant PD, with two even being able to discontinue antipsychotic medications. Post-surgical seizure outcomes, assessed using the Engel Surgical Outcome Scale, were also highly favorable, with patients either becoming completely seizure-free or experiencing only rare seizures ( 12 ). Interestingly, a large population- based study in people with TLE revealed that PDs were predictive of surgery failure, defined as significantly lower rates of Engel class I and IA ( 16 ). The authors speculated that complex brain microstructural abnormalities in people with TLE and psychiatric comorbidities might underlie this association, emphasizing the need for further research.

In a separate comparative study, PDs were more commonly associated with extratemporal lobe epilepsy (ExTLE) rather than TLE, leading to lower rates of surgical intervention for individuals with this comorbidity. Nevertheless, those who did undergo surgery exhibited similarly successful outcomes ( 20 ). Moreover, people with epilepsy and PDs seem to suffer from an even bleaker stigma, as shown by lower employment rates two years after surgery ( 18 ).

Conversely, three studies did not detect significant differences in PD prevalence among PwE. One uncontrolled study focused only on people with intellectual disability and epilepsy, thus this finding could be attributed to a population selection bias ( 23 ). In the other two studies, discrepancies in results might be attributed to the specific assessment scales utilized – as questioned by the Authors themselves ( 17 ) - or the comparison of PD prevalence across different subtypes of focal epilepsy ( 19 ) that did not yield statistically significant differences.

Personality disorders and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

Three studies on PDs and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) were identified. Two recent comparative studies showed that PDs were significantly more prevalent in JME compared to healthy controls. While one study did not identify specific correlation between PD subtypes and JME ( 24 ), the other reported strong associations between narcissistic, borderline, paranoid and histrionic PDs and JME ( 25 ). These discrepancies may stem from variations in assessment scales used, as the populations examined exhibited otherwise similar characteristics. A third older and purely descriptive study focused on assessing the prevalence of PDs in a medium-size sample of patients with JME, without providing statistical analyses ( 23 ).

Personality disorders and psychogenic non-epileptic seizures

Among the 9 studies investing the association between PDs and psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES), seven were comparative studies comparing people with PNES to various control groups, including those with epilepsy/epileptic seizures alone ( 27 – 31 , 35 ), PwE and PNES ( 33 ), or healthy controls ( 30 ). The remaining two studies were observational uncontrolled studies that gathered data on people with PNES through medical history and hospital charts ( 32 , 34 ). While the evidence from these latter two studies was undoubtedly of lower quality due to the lack of proper statistical analysis and, in one case, insufficient details on the methods used to diagnose PD ( 34 ), we deemed it important to include them as seminal works that highlighted a higher prevalence of Cluster B PDs in people with PNES, a finding largely confirmed by subsequent literature and deemed statistically significant in the majority of our results ( 28 – 31 ). However, three studies presented discordant findings in this regard, potentially influenced by factors such as the assessments tools used. For instance, one study ( 27 ) reported statistically significant high scores in the “extraversion” section of the NEO-Personality Inventory-Revised among patients with PNES. The other two studies assessed PDs by the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), despite criticisms regarding its limitations and inconsistency of results obtained using this tool ( 36 , 37 ).

Regarding gender differences, two studies show a statistically significant higher prevalence of PDs in women with PNES ( 28 , 29 ).

Despite the known higher prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities in PwE, the relationship between epilepsy and PDs has been inadequately investigated in the most recent scientific literature ( 38 ).

Our review demonstrates that the literature available on this topic is extremely heterogeneous in terms of methodology, population size, type of epilepsy investigated and assessment tools used for evaluating the disorder, with many works even failing to differentiate between psychiatric disorders in general and PDs ( 38 – 43 ). This last issue seems particularly relevant as the vast majority of the examined studies tend to combine and investigate various psychiatric conditions together ( 44 ). Conversely, when studies do focus on personality comorbidities, they often center on traits or symptoms rather than formally diagnosed PDs ( 39 – 41 ). Such methodological inconsistencies present a significant barrier to the comprehensive inclusion of pertinent evidence in our analysis, consequently constraining our capacity to derive meaningful insights regarding the relationship between PDs and epilepsy.

Another issue encountered in reviewing the existing literature on this subject is the lack of strong evidence due to the limited scope of studies carried out thus far, as, in spite of the higher prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities in PwE and the impact they seem to have on epilepsy prognosis itself, the number of well-designed case-control studies investigating their correlation remains insufficient ( 24 ). Ideally, to ensure statistical validity and clinical relevance, systematic comparisons should be made among different types of epilepsy and between PWE and healthy controls. Moreover, it seems very interesting to observe that there is relatively little standardized work on the issue of diagnostic tools used to identify PDs in epilepsy. Many studies relied on the MMPI, despite concerns raised by some researchers ( 36 , 37 ). The consequence of it, however, is the vast array of diagnostic tools used subsequently, such as the Bear-Fedio Inventory (BFI), the DSM-IV axis I and axis II, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R PDs (SCID-II), the Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS) and many others, making the different results obtained arduous to analyse in a comprehensive fashion ( 38 ). Moreover, as reiterated by Trimble ( 36 ), the diagnosis made by scales cannot be considered valid tout court for a clinical diagnosis.

On the other hand, the change in the classification of the same disorders in relation to different editions of the DSM, the same different classification of epilepsies, the change in the treatment of them in recent years and, in particular, the increased social integration of individuals with epilepsy do not allow the historically acquired data to be considered valid.

Furthermore, the literature revision is complicated by its heterogeneity, as specific different types of epilepsy were investigated in individual studies, while, on the contrary, some neglected to differentiate between epilepsy and isolated seizures. There is a long-standing and established interest in exploring the relationship between PDs and PNES ( 35 ) and, more recently, a rapidly growing body of evidence on PDs in people with focal epilepsy has emerged ( 19 – 21 ), even applying the recently proposed dimensional approach to personality profile ( 45 ). However, there are only scattered studies on other subtypes of epilepsy, such as JME ( 24 ), and, to our best knowledge, very few works on the correlation between PDs and epilepsy as a whole, most of which also happen to be quite dated ( 36 , 46 – 48 ).

Given these limitations, our study aimed to aggregate and summarize available findings to offer a current perspective on the state of research in this area. By highlighting these constraints, we hope to identify potential research directions for future exploration. The relationship between PDs and focal epilepsy, particularly TLE, is well-established, with prevalence rates ranging from 18 to 42% in surgical candidates or post-surgical individuals ( 49 ). While there is no clear agreement as to what type of PD is the most prevalent, cluster C personality disorders or related traits and symptoms seem to be the most frequent ( 13 – 15 , 31 , 40 , 50 ). However, the correlation between TLE, PDs and surgical treatment remains inconclusive, highlighting the need for future works to delve in this complex relationship, due to its profound impact on patients’ outcome.

In the context of JME, the prevalence and specific types of PDs remain contentious among the limited available studies ( 51 ). Nevertheless, the significance of exploring this relationship is undeniable, given the prevalence of JME. Analysing the correlation between JME and PDs within the broader framework of the idiopathic generalized epilepsies, ideally comparing JME with the other subtypes, could yield robust evidence on their psychiatric and personality profiles.

Our research underscores a strong connection PDs and PNES, particularly in females, with a strong association with cluster B personality disorders, notably borderline personality disorder ( 52 ). Delayed diagnosis of PNES, averaging 7-9 years from the initial clinical episode, leads to unnecessary hospitalizations and inappropriate treatment with antiseizure medications (ASMs) ( 53 ). Regarding the association with PNES, it must, in any case, be considered, that since PNES is a psychiatric disorder, many authors wonder whether we are really facing an association of different pathologies or a single one ( 11 ).

Regarding ASMs in general, our review highlights that the presence of a PD in PwE, regardless of the subtype, complicates treatment management. Clinicians face challenges in maintaining a delicate balance due to the potential for ASMs to worsen or exacerbate underlying PDs, as observed with drugs like perampanel and levetiracetam ( 7 , 54 – 57 ).

This review has methodological limitations. We conducted our research through only one database, potentially excluding relevant evidence available from other online sources. Moreover, few studies were not included for language reasons ( 58 – 61 ). Lastly, we did not offer an analysis of the evidence strength provided by each work as the grand variety of statistical methodology used, population size, type of epilepsy and parameters considered made us opt for a purely descriptive presentation of our findings. However, we do not think that these limits significantly reduce the strength of our results, which allowed us to identify research paths worthy of further investigation.

Conclusions and directions for future research

While the relationship between psychiatric comorbidities and epilepsy has been discussed since time immemorial ( 47 ), our study reveals a notable lack of definitive data on various aspects concerning PDs in PwE. The literature in this domain is limited and methodologically diverse, yet our findings suggest that PDs are a prevalent comorbidity in PwE.

Future research should prioritize the identification of significant correlations between PDs and specific types of epilepsy, as well as elucidate how their co-occurrence influence patients’ prognosis. Additionally, it is crucial to investigate the effects of current ASMs on concomitant PDs.

Given the increasing number of patients being considered for epilepsy surgery, it is of the utmost importance to deepen our understanding of the neurological basis and pathological mechanisms that intertwine PDs and epilepsy, given the current scarcity of evidence that may inadvertently hinder optimal treatment decisions for some patients.

Based on our findings and with the aim of enhancing patient care and wellbeing, we advocate for a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach involving neurologists and psychiatrists, which should begin from the early stages of diagnosis and extend to the selection of personalized therapeutic strategies for each patient.

Author contributions

VV: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology. FB: Writing – review & editing. CC: Writing – review & editing. LF: Writing – review & editing. LL: Writing – review & editing. LM: Writing – review & editing. BM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The publication of this article was supported by the “Ricerca Corrente” funding from the Italian Ministry of Health.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Loretta Giuliano for her help in creating our search string for PubMed.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Fisher RS, Acevedo C, Arzimanoglou A, Bogacz A, Cross JH, Elger CE, et al. ILAE official report: a practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia . (2014) 55:475–82. doi: 10.1111/epi.12550

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Beghi E. The epidemiology of epilepsy. Neuroepidemiology . (2020) 54:185–91. doi: 10.1159/000503831

3. Feigin VL, Nichols E, Alam T, Bannick MS, Beghi E, Blake N, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol . (2019) 18:459–80. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30499-X

4. Keezer MR, Sisodiya SM, Sander JW. Comorbidities of epilepsy: current concepts and future perspectives. Lancet Neurol . (2016) 15:106–15. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00225-2

5. Taylor RS, Sander JW, Taylor RJ, Baker GA. Predictors of health-related quality of life and costs in adults with epilepsy: a systematic review. Epilepsia . (2011) 52:2168–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03213.x

6. Ioannou P, Foster DL, Sander JW, Dupont S, Gil-Nagel A, Drogon O’Flaherty E, et al. The burden of epilepsy and unmet need in people with focal seizures. Brain Behav . (2022) 12:e2589. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2589

7. Memon AM, Katwala J, Douille C, Kelley C, Monga V. Exploring the complex relationship between antiepileptic drugs and suicidality: A systematic literature review. Innov Clin Neurosci . (2023) 20:47–51.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

8. Benson DF. The geschwind syndrome. Adv Neurol . (1991) 55:411–21.

9. Blumer D. Evidence supporting the temporal lobe epilepsy personality syndrome. Neurology . (1999) 53:S9–12.

10. Devinsky O, Najjar S. Evidence against the existence of a temporal lobe epilepsy personality syndrome. Neurology . (1999) 53:S13–25.

11. Beghi M, Beghi E, Cornaggia CM, Gobbi G. Idiopathic generalized epilepsies of adolescence. Epilepsia . (2006) 47 Suppl 2:107–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00706.x

12. Cornaggia CM. Epilepsy and risks: a first-step evaluation . Milano: Ghedini editore (1993).

Google Scholar

13. Sair A, Şair YB, Saracoğlu İ, Sevincok L, Akyol A. The relation of major depression, OCD, personality disorders and affective temperaments with Temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res . (2021) 171:106565. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2021.106565

14. Baishya J, Ravish Rajiv K, Chandran A, Unnithan G, Menon RN, Thomas SV, et al. Personality disorders in temporal lobe epilepsy: What do they signify? Acta Neurol Scand . (2020) 142:210–5. doi: 10.1111/ane.13259

15. Novais F, Franco A, Loureiro S, Andrea M, Figueira ML, Pimentel J, et al. Personality patterns of people with medically refractory epilepsy - Does the epileptogenic zone matter? Epilepsy Behav EB . (2019) 97:130–4. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.05.049

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Koch-Stoecker SC, Bien CG, Schulz R, May TW. Psychiatric lifetime diagnoses are associated with a reduced chance of seizure freedom after temporal lobe surgery. Epilepsia . (2017) 58:983–93. doi: 10.1111/epi.13736

17. Landais A, Crespel A, Moulis JL, Coubes P, Gelisse P. Psychiatric comorbidity in temporal DNET and improvement after surgery. Neurochirurgie . (2016) 62:165–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neuchi.2016.02.002

18. Thorbecke R, May TW, Koch-Stoecker S, Ebner A, Bien CG, Specht U. Effects of an inpatient rehabilitation program after temporal lobe epilepsy surgery and other factors on employment 2 years after epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia . (2014) 55:725–33. doi: 10.1111/epi.12573

19. Dalmagro CL, Velasco TR, Bianchin MM, Martins APP, Guarnieri R, Cescato MP, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in refractory focal epilepsy: a study of 490 patients. Epilepsy Behav EB . (2012) 25:593–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.09.026

20. Sperli F, Rentsch D, Despland PA, Foletti G, Jallon P, Picard F, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in patients evaluated for chronic epilepsy: a differential role of the right hemisphere? Eur Neurol . (2009) 61:350–7. doi: 10.1159/000210547

21. Mula M, Cavanna A, Collimedaglia L, Viana M, Barbagli D, Tota G, et al. Clinical correlates of schizotypy in patients with epilepsy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci . (2008) 20:441–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.20.4.441

22. Manchanda R, Schaefer B, McLachlan RS, Blume WT, Wiebe S, Girvin JP, et al. Psychiatric disorders in candidates for surgery for epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry . (1996) 61:82–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.61.1.82

23. Deb S, Hunter D. Psychopathology of people with mental handicap and epilepsy. III: Personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci . (1991) 159:830–4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.6.830

24. Panda PK, Ramachandran A, Tomar A, Elwadhi A, Kumar V, Sharawat IK. Prevalence, nature, and severity of the psychiatric comorbidities and their impact on quality of life in adolescents with Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav EB . (2023) 142:109216. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.109216

25. Taura M, Gama AP, Sousa AVM, Noffs MHS, Alonso NB, Yacubian EM, et al. Dysfunctional personality beliefs and executive performance in patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav EB . (2020) 105:106958. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.106958

26. Trinka E, Kienpointner G, Unterberger I, Luef G, Bauer G, Doering LB, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsia . (2006) 47:2086–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00828.x

27. Sobregrau P, Baillès E, Carreño M, Donaire A, Boget T, Setoain X, et al. Psychiatric and psychological assessment of Spanish patients with drug-resistant epilepsy and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) with no response to previous treatments. Epilepsy Behav EB . (2023) 145:109329. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.109329

28. Sullivan-Baca E, Weitzner DS, Choudhury TK, Fadipe M, Miller BI, Haneef Z. Characterizing differences in psychiatric profiles between male and female veterans with epilepsy and psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Epilepsy Res . (2022) 186:106995. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2022.106995

29. Rady A, Elfatatry A, Molokhia T, Radwan A. Psychiatric comorbidities in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav EB . (2021) 118:107918. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.107918

30. Direk N, Kulaksizoglu IB, Alpay K, Gurses C. Using personality disorders to distinguish between patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures and those with epileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav EB . (2012) 23:138–41. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.11.013

31. Harden CL, Jovine L, Burgut FT, Carey BT, Nikolov BG, Ferrando SJ. A comparison of personality disorder characteristics of patients with nonepileptic psychogenic pseudoseizures with those of patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav EB . (2009) 14:481–3. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.12.012

32. Baillés E, Pintor L, Fernandez-Egea E, Torres X, Matrai S, De Pablo J, et al. Psychiatric disorders, trauma, and MMPI profile in a Spanish sample of nonepileptic seizure patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry . (2004) 26:310–5. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.04.003

33. Kalogjera-Sackellares D, Sackellares JC. Personality profiles of patients with pseudoseizures. Seizure . (1997) 6:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S1059-1311(97)80045-3

34. Drake MEJ, Pakalnis A, Phillips BB. Neuropsychological and psychiatric correlates of intractable pseudoseizures. Seizure . (1992) 1:11–3. doi: 10.1016/1059-1311(92)90048-6

35. Vanderzant CW, Giordani B, Berent S, Dreifuss FE, Sackellares JC. Personality of patients with pseudoseizures. Neurology . (1986) 36:664–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.36.5.664

36. Trimble MR. Personality disturbances in epilepsy. Neurology . (1983) 33:1332–4. doi: 10.1212/WNL.33.10.1332-a

37. Perini GI, Tosin C, Carraro C, Bernasconi G, Canevini MP, Canger R, et al. Interictal mood and personality disorders in temporal lobe epilepsy and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry . (1996) 61:601–5. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.61.6.601

38. Swinkels WAM, Duijsens IJ, Spinhoven P. Personality disorder traits in patients with epilepsy. Seizure . (2003) 12:587–94. doi: 10.1016/S1059-1311(03)00098-0

39. Guo X, Lin W, Zhong R, Han Y, Yu J, Yan K, et al. Factors related to the severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms and their impact on suicide risk in epileptic patients. Epilepsy Behav EB . (2023), 146:109362. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.109362

40. Kilicaslan EE, Türe HS, Kasal Mİ, Çavuş NN, Akyüz DA, Akhan G, et al. Differences in obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions between patients with epilepsy with obsessive-compulsive symptoms and patients with OCD. Epilepsy Behav EB . (2020) 102:106640. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.106640

41. Kim SJ, Lee SA, Ryu HU, Han SH, Lee GH, Jo KD, et al. Factors associated with obsessive-compulsive symptoms in people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav EB . (2020) 102:106723. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.106723

42. Ertekin BA, Kulaksizoğlu IB, Ertekin E, Gürses C, Bebek N, Gökyiğit A, et al. A comparative study of obsessive-compulsive disorder and other psychiatric comorbidities in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy and idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav EB . (2009) 14:634–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.01.016

43. Isaacs KL, Philbeck JW, Barr WB, Devinsky O, Alper K. Obsessive-compulsive symptoms in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav EB . (2004) 5:569–74. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.04.009

44. de Oliveira GNM, Kummer A, Salgado JV, Portela EJ, Sousa-Pereira SR, David AS, et al. Psychiatric disorders in temporal lobe epilepsy: an overview from a tertiary service in Brazil. Seizure . (2010) 19:479–84. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2010.07.004

45. Kustov G, Zhuravlev D, Zinchuk M, Popova S, Tikhonova O, Yakovlev A, et al. Maladaptive personality traits in patients with epilepsy and psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Seizure . (2024) 117:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2024.02.005

46. Jeżowska-Jurczyk K, Kotas R, Jurczyk P, Nowakowska-Kotas M, Budrewicz S, Pokryszko-Dragan A. Mental disorders in patients with epilepsy. Psychiatr Pol . (2020) 54:51–68. doi: 10.12740/PP/93886

47. Trimble MR. Personality disorders and epilepsy. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) . (1988) 44:98–101. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9005-0_20

48. Trimble MR. Psychiatric aspects of epilepsy. Psychiatr Dev . (1987) 5:285–300.

49. Gaitatzis A, Trimble MR, Sander JW. The psychiatric comorbidity of epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand . (2004) 110:207–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2004.00324.x

50. Hamed SA, Elserogy YM, Abd-Elhafeez HA. Psychopathological and peripheral levels of neurobiological correlates of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in patients with epilepsy: a hospital-based study. Epilepsy Behav EB . (2013) 27:409–15. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.01.022

51. Gélisse P, Thomas P, Samuelian JC, Gentin P. Psychiatric disorders in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsia . (2007) 48:1032–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01009_4.x

52. Lacey C, Cook M, Salzberg M. The neurologist, psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, and borderline personality disorder. Epilepsy Behav EB . (2007) 11:492–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.09.010

53. Oto MM. The misdiagnosis of epilepsy: Appraising risks and managing uncertainty. Seizure . (2017) 44:143–6. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2016.11.029

54. Villanueva V, Garcés M, López-González FJ, Rodriguez-Osorio X, Toledo M, Salas-Puig J, et al. Safety, efficacy and outcome-related factors of perampanel over 12 months in a real-world setting: The FYDATA study. Epilepsy Res . (2016) 126:201–10. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2016.08.001

55. Yumnam S, Bhagwat C, Saini L, Sharma A, Shah R. Levetiracetam-associated obsessive-compulsive symptoms in a preschooler. J Clin Psychopharmacol . (2021) 41:495–6. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000001402

56. Fujikawa M, Kishimoto Y, Kakisaka Y, Jin K, Kato K, Iwasaki M, et al. Obsessive-compulsive behavior induced by levetiracetam. J Child Neurol . (2015) 30:942–4. doi: 10.1177/0883073814541471

57. Mbizvo GK, Dixon P, Hutton JL, Marson AG. The adverse effects profile of levetiracetam in epilepsy: a more detailed look. Int J Neurosci . (2014) 124:627–34. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2013.866951

58. Usykina MV, Kornilova SV, Lavrushchik MV. [Cognitive impairment and social functioning in organic personality disorder due to epilepsy]. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S Korsakova . (2021) 121:21–6. doi: 10.17116/jnevro202112106121

59. Dvirskiĭ AE, Shevtsov AG. [Clinical manifestations of epilepsy in hereditary schizophrenia]. Zhurnal Nevropatol Psikhiatrii Im SS Korsakova Mosc Russ 1952 . (1991) 91:28–30.

60. Ekiert H, Jarzebowska E, Nurowska K, Welbel L. [Personality of epileptic patients and their relatives with special regard to traits and symptoms not included in the epileptic character]. Psychiatr Pol . (1967) 1:15–21.

61. Bilikiewicz A, Gromska J. Mental symptoms and character disorders in epilepsy with the “Temporal Syndrome”. Neurol Neurochir Psychiatr Pol . (1964) 14:879–82.

Keywords: epilepsy, personality disorders (PDs), PNES, juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME), temporal lobe epilepsy, epilepsy surgery

Citation: Viola V, Bisulli F, Cornaggia CM, Ferri L, Licchetta L, Muccioli L and Mostacci B (2024) Personality disorders in people with epilepsy: a review. Front. Psychiatry 15:1404856. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1404856

Received: 21 March 2024; Accepted: 24 April 2024; Published: 10 May 2024.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2024 Viola, Bisulli, Cornaggia, Ferri, Licchetta, Muccioli and Mostacci. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Barbara Mostacci, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Personality and psychopathological characteristics in functional movement disorders

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Medicine and Surgery, Kore University of Enna, Enna, Italy

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Medical, Surgical Sciences and Advanced Technologies, GF Ingrassia, University of Catania, Catania, Italy

Roles Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Medical, Surgical Sciences and Advanced Technologies, GF Ingrassia, University of Catania, Catania, Italy, Oasi Research Institute-IRCCS Troina, Troina, Italy

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

- Antonina Luca,

- Tiziana Lo Castro,

- Giovanni Mostile,

- Giulia Donzuso,

- Calogero Edoardo Cicero,

- Alessandra Nicoletti,

- Mario Zappia

- Published: May 10, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303379

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Introduction

Aim of the present study was to assess personality and psychopathological characteristics in patients with functional movement disorders (FMDs) compared to patients with other neurological disorders (OND).

In this cross-sectional study, patients affected by clinically established FMDs and OND who attended the Neurologic Unit of the University-Hospital “Policlinico-San Marco” of Catania from the 1 st of December 2021 to the 1 st of June 2023 were enrolled. Personality characteristics were assessed with the Rorschach test coded according to Exner’s comprehensive system and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-II).

Thirty-one patients with FMDs (27 women; age 40.2±15.5 years; education 11.7±3.2 years; disease duration 2.3±2.5 years) and 24 patients affected by OND (18 women; age 35.8±16.3 years; education 11.9±2.9 years; disease duration 3.4±2.8 years) were enrolled. At the Rorschach, FMDs presented a significantly higher frequency of Popular (P) and sum of all Human content codes (SumH>5) responses and avoidant coping than OND.

FMDs presented “conformity behaviors”, excessive interest in others than usual a maladaptive avoidant style of coping and a difficulty in verbalizing emotional distress. These psychopathological characteristics may favor the occurrence of FMDs.

Citation: Luca A, Lo Castro T, Mostile G, Donzuso G, Cicero CE, Nicoletti A, et al. (2024) Personality and psychopathological characteristics in functional movement disorders. PLoS ONE 19(5): e0303379. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303379

Editor: Simone Varrasi, University of Catania, ITALY

Received: February 6, 2024; Accepted: April 24, 2024; Published: May 10, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 Luca et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: No authors have competing interests

Functional movement disorders (FMDs) are movement disorders that cannot be explained by typical neurological diseases or other medical conditions [ 1 ]. FMDs are a frequent cause of disability and poor quality of life and have a notable economic impact due to loss of employment, inappropriate or unnecessary diagnostic procedures and delayed diagnosis [ 2 ]. From a phenotypical point of view, FMDs can present with any type of movement disorder, including weakness, tremor, dystonia, gait disorders, myoclonus and chorea, often in combinations [ 3 ]. The treatment of FNDs frequently requires a non-pharmacological approach based on both psychotherapy and physiotherapy, meticulously tailored to the patients and requiring a multidisciplinary clinical approach [ 4 , 5 ].

Although the exact mechanisms leading to FMDs are still unclear, it has been emphasized that predisposing vulnerabilities (i.e. personality traits, psychiatric comorbidities, alexithymia…), precipitants (i.e traumatic events, post-traumatic stress disorder…) and perpetuating factors (i.e family and/or financial concerns, lack of social support…) exert a pivotal role in FMDs occurrence [ 6 ]. However, to date, the role of personality traits possibly associated with the occurrence of FMDs still need to be clarified [ 7 , 8 ].

Yet, differently from mood states, personality is an essentially stable internal factor making individual behavior consistent over time. Moreover, personality traits exert a fundamental role on stress vulnerability, coping effectiveness and human interactions [ 9 ]. Hence, the individualization of peculiar personality traits may be useful for a tailored approach during the diagnosis communication and the choice of therapeutic options.

Aim of the present study was to assess personality and psychopathological characteristics in patients with FMDs compared to patients with other neurological disorders (OND) as control group.

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional study was performed according to The Reporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) Statement.

Patients affected by laboratory supported FMDs [ 10 ] who attended the Neurologic Unit of the University-Hospital “Policlinico-San Marco” of Catania from the 1 st of December 2021 to the 1 st of June 2023 were enrolled in the study and compared to patients affected by OND. Patients with cognitive impairment were excluded from the study. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the Ethical Committee of the University Hospital “Policlinico-San Marco” of Catania, Italy. Protocol number: 117/2021/PO. All the enrolled subjects signed the consent to participate.

Instruments

Neuropsychological assessment..

All the enrolled subjects underwent the following comprehensive neuropsychological battery in order to exclude patients with cognitive deficits: global cognition screening test (Mini Mental State Examination, Montreal Cognitive Assessment), episodic memory (Rey’s Auditory Verbal Learning Test), attention (Stroop color-word test), executive functioning (Verbal fluency letter test, Frontal Assessment Battery) and visuo-spatial functioning (Clock drawing test).

The presence of depression and anxiety were evaluated with, respectively, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) and the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI Y1-Y2).

Personality assessment.

Personality characteristics were assessed with the Rorschach test coded according to Exner’s comprehensive system [ 11 ] and administrated by a psychologist with certified expertise (TLC). The Rorschach consists of 10 inkblots, administered and coded in a standardized way. Seven major clusters and their related variables were evaluated: 1) control and stress tolerance, 2) affect, 3) ideation, 4) cognitive mediation, 5) information processing, 6) self-perception, 7) interpersonal perception ( S1 Table ).

The presence of Personality Disorders (PeDs) diagnosed according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders 5 edition (DSM-5) was assessed through the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-II) .

Statistical analysis

Due to the lack of studies assessing personality with the Rorschach test in patients with FMD, the study sample size was calculated considering the prevalence of PeDs assessed with the SCID-II [ 16 ]. Assuming an alpha error level of 0.05 and a power of 80%, to reach a significant difference (p<0.005), the minimum number of participants required was 16 in FMD group and 16 in the OND group, for a total of 32 patients.

Data were analyzed using STATA 16 software packages (StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States). Quantitative variables were described using mean and standard deviation. The Shapiro–Wilk normality test was performed. Differences between means were evaluated with the unpaired t-test in the case of normal distribution and the Mann–Whitney U test for not-normal distribution. Qualitative variables were described using frequency and percentage and compared with the Chi square test. Univariate analysis was performed to assess the associations between demographic and psychological characteristics and FMD, considered as outcome variable. Age and sex considered a priori confounders and variables with p-value< 0.1 at univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. The significance level was set at 0.05 and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) were calculated. A statistical analysis considering FMD phenotypes was finally performed.

Thirty-one patients with FMDs (27 women; age 40.2±15.5 years; education 11.7±3.2 years; disease duration 2.3±2.5 years) and 24 patients affected by OND (18 women; age 35.8±16.3 years; education 11.9±2.9 years; disease duration 3.4±2.8 years) were enrolled. Among FMDs group, the predominant symptom was weakness (w), variously associated with tremor (FMD-wT, n.8; 25.8%) and gait disorders (FMD-wGD, n.23; 74.2%). Considering FMD phenotype, no statistically significant differences were found comparing FMD-wT and FMD-wGD in terms of sex [respectively 7 (87.5%) versus 20 (86.9%) women, p-value 0.968], age (respectively 37.5±14.8 versus 41.2±15.9 years, p-value 0.568) and education (respectively 10.8±3.6 versus 12.0±3.13 years, p-value 0.406).

The OND group was represented by patients with multiple sclerosis (n.19; 79.2%), post-ischemic stroke weakness (n.4; 16.6%) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (n.1; 4.2%).

No significant differences in terms of sex (p-value 0.256), age (p-value 0.308), education (p-value 0.765) and disease duration (p-value 0.553) were found comparing patients with FMDs and patients with OND.

No significant differences in cognitive performances were recorded when comparing the two groups ( Table 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303379.t001

At the Rorschach, FMDs presented a significantly higher frequency of Popular (P) and Sum of all Human content codes (SumH>5) responses than OND (For more details pertaining the variables, see S1 Table and Fig 1 ).

The most frequent (Popular) response is “Two humans interacting” [ 12 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303379.g001

Moreover, the avoidant type of coping was significantly more frequent among FMDs than OND. At multivariate analysis, the associations were confirmed for both P responses (OR 5.78; 95% CI 1.04–31.94; p-value 0.044), SumH>5 (OR 11.74; 95% CI 1.88–73.20; p-value 0.008) and avoidant type of coping (OR 4.6; 95% CI 1.38–15.32; p-value: 0.013) ( Table 2 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303379.t002

Concerning FMD phenotypes, SumY>2 was significantly more frequent in FMDs-wT (n.4, 50%) than FMDs-wGD (n.3, 13%; p-value: 0.031). Moreover, the introvertive and avoidant types of coping, as well as Zd<-3 and An+Xy>1 were more frequent in FMD-wT than FMDs-wGD, although the difference was not statistically significant ( Table 3 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303379.t003

At the SCID-II, no statistically significant differences were recorded comparing the two groups. In particular, 8 (25.8%) patients with FMD and 3 (12.5%) patients with OND fulfilled the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PeDs (p-value 0.336). Out of the 8 FMD patients with PeD, 2 (25%) had obsessive-compulsive PeD, 2 (25%) had borderline PeD, 2 (25%) had avoidant PeD, 1 (12.5%) had dependent PeD and 1 (12.5%) had paranoid PeD. Out of the 3 patients with OND, 1 (33.3%) had obsessive-compulsive PeD, 1 (33.3%) had narcissistic PeD and 1 (33.3%) had paranoid PeD.

The Rorschach test has been previously used to assess personality functioning in patients suffering from neurological disorders, including multiple sclerosis, migraine and epilepsy [ 13 , 14 ]. However, to the best of our knowledge, to date no studies evaluating the personality structure of patients with FMDs applying a Rorschach approach are available.

In the present study, patients with FMDs presented peculiar personality characteristics compared to patients with OND. More in details, patients with FMDs presented a significantly higher percentage of P responses than patients with OND. Remarkably, P responses strictly reflect the individual ability to get involved in popular thinking, “social standards” and conformity. The “conformity” behavior, as part of the social implicit expectations, deeply affects one’s own social attitudes leading to a voluntary behavioral change to imitate peers’ behavior and respond to normative rules [ 15 ]. Interestingly, previous studies have hypothesized that the strict adherence to social compliance and conformity may represent a compensatory strategy to cope the private information insufficiency in case of high-ambiguity situation, thus assuming the “best behavior” [ 16 ].

Similarly, also the SumH variable was significantly higher in patients with FMDs than in patients with OND. Considering that the SumH variable represents the interest of the individual in others, the high percentage of SumH could reflect an “exaggerated” interest in others as the result of a higher than is typical innate drive for social acceptance, fearing of being excluded from the group and social pressures [ 17 ].

Pertaining phenotypes, FMDs-wT presented a significantly higher number of SumY responses than FMDs-wGD, thus reflecting “emotional confusion” and negative feelings stress-related. Moreover, respect to FMDs-wGD, patients with FMDs-wT presented a higher number of anatomy (i.e. liver, bones…) and X-Ray (i.e. X‐ray of a pelvis, ultrasound of a fetus …) responses (An+Xy), classically more frequent among people with an everyday confrontation with body due to job position (i.e. doctors, nurses…) [ 18 ] but also in people suffering from somatizations and body concerns.

When PeDs diagnosed according DSM-5 criteria was assessed, no differences were found between FMDs and OND patients. Our findings are in line with the study performed by Defazio and coll. [ 19 ], which did not find any differences in the frequency of PeDs between patients with FMDs and patients with OND. Nevertheless, as for the study performed by Defazio and coll. [ 19 ], due to the small sample size, it could not be excluded that the non-significant difference recorded between FMDs and OND in PeDs frequency could be the result of a low statistical power.

Moreover, in our sample, FMDs frequently presented an avoidant style of coping, characterized by a maladaptive way in which they deal with problems. Consequently, patients with FMDs may isolated themselves from interpersonally complex situations, applying defensive maneuvers to “protect” themselves by the challenges of everyday life. Indeed, recent studies have reported that FMDs presented more frequently an insecure and avoidant attachment style [ 20 ], characterized by the reluctance to self-disclose and emotional suppression used as a strategy to cope with fear of judgment and rejection.

Summarizing, in the present study patients with FMDs presented a personality dimension characterized by “conformity behaviors” and excessive interest in others than usual and a maladaptive avoidant style of coping. These psychopathological characteristics may favor the occurrence of FMDs that mimic organic movement disorders, probably less stigmatized, misunderstood and victim of harmful social distancing than non-organic ones.

The scoring of the Rorschach inkblot test is undoubtedly complex, time-consuming and painstaking. However, our findings support the usefulness of the Rorschach approach in identifying personality “weaknesses and strengths” that should be considered in the treatment planning. Furthermore, in our study, personality traits were assessed using the multilevel personality assessment framework (SCID-II, Rorschach test, comprehensive neuropsychological battery) that, notably, might explain possible personality-based underpinnings of the development and maintenance of FMD with possible research, clinical and treatment implications.

The present study has some limitation. The enrolment of FMDs mainly characterized by functional weakness may reduce the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, although about 80% of OND were represented by patients with multiple sclerosis, a bias related to the heterogeneity of the OND group could not be ruled out. Furthermore, the small sample size and the large 95% CI recorded did not allow us to exclude that the lack of significant differences recorded in several Rorschach variables could be the result of a low statistical power. However, more patients than those required by the sample size calculation were enrolled. Finally, although the Rorschach test provides valuable insights into personality characteristics, it could be subject to interpretation across different raters. Nevertheless, to reduce possible bias, all the enrolled patients were assessed by the same rater, whose experience in Rorschach administration and coding is certified.

In conclusion, our findings may be useful not only to better understand predisposing factors of FMDs but also to build a “good” therapeutic alliance, necessary to plan a personalized treatment, frequently requiring an integrated multidisciplinary approach [ 21 ]. Indeed, the assessment of personality characteristics may be useful to maximize the adherence, reducing “beliefs” that may represent barriers, enhancing the readiness for change and, ultimately, improving treatment success.

Larger studies including healthy control group matched by age, sex and education are needed to confirm our finding and to define the possible role of personality not only in FMDs occurrence but also in determining its presentation with one clinical phenotype (i.e. tremor, dystonia, gait disorders, parkinsonism, chorea…) rather than another.

Supporting information

S1 checklist. the record statement–checklist of items, extended from the strobe statement, that should be reported in observational studies using routinely collected health data..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303379.s001

S1 Table. Description and interpretation of the Rorschach variables.

Abbreviations: Adj D: Adjusted Difference Score. CDI: Coping Deficit Index; SumY: Sum of diffuse shading determinants; FC: Form-color; CF: Color-form; C: Color; FM: Animal Movement; SumC’: Sum of color; WSumC (Weighted Sum of Color); SumT: Sum of texture determinants; SumV: Sum of vista determinants; Zd: Efficiency index; XA%: Accuracy in perception; X-%; distortion in perception; P: Popular; DEPI: Depression index; HVI: Hypervigilance Index; Fr: Rf: SumH: Sum human; An: Anatomy; Xy: X-ray; GHR: Good human representational responses; PHR: Poor human representational responses.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303379.s002

S1 Dataset.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303379.s003

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

Personality disorder traits are associated with greater loneliness

R ecent developments in mental health research have highlighted the role of social factors in the lives of individuals with personality disorder diagnoses or traits. A growing body of literature has revealed the profound sense of disconnection and unmet social needs characterizing this group, raising questions about the impact of loneliness and perceived social support (PSS) on their path to recovery. Sarah Ikhtabi and colleagues conducted a systematic review to quantify the prevalence and severity of loneliness and PSS deficits. This research was published in BMC Psychiatry .

The researchers followed PRISMA guidelines for methodological rigor and registered the protocol on PROSPERO . Their search strategy encompassed a comprehensive review of four major databases—Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, and Web of Social Science—extended by searches in Google Scholar and the Ethos British Library database to capture dissertations and theses, from database inception to December 13, 2021. Search terms included a broad range of social concepts, loneliness, and various aspects of personality disorder assessments, aiming for an exhaustive coverage of the topic.

For inclusion, studies had to report on the prevalence or severity of loneliness and/or PSS deficits in individuals with personality disorder traits or diagnoses, utilizing validated measures of loneliness or PSS. The review process involved rigorous screening, data extraction, and quality assessment by the research team, with disagreements resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

Methodological quality was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute tools, and evidence certainty was evaluated using the GRADE approach. The narrative synthesis of results emphasized the comparison of loneliness and PSS deficits in people with personality disorders against other groups, paying special attention to high-quality studies while also acknowledging findings from lower-quality research to provide a comprehensive overview.

Ikhtabi and colleagues found a significant correlation between personality disorders and increased levels of loneliness as well as deficits in PSS. Individuals with personality disorders, particularly those identified with traits of Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder and Avoidant Personality Disorder, were found to experience higher levels of loneliness and deficiencies in social support compared to other clinical groups and the general population.

This research also highlights a complex association between narcissistic personality traits and loneliness/PSS, which varies depending on the type of narcissism (vulnerable/covert versus grandiose/overt).

Despite the strong associative evidence presented, the review notes a lack of longitudinal studies that would allow for a more definitive understanding of the causality of these relationships, acknowledging the low certainty of the current evidence base due to methodological limitations.

The review, “ The prevalence and severity of loneliness and deficits in perceived social support among who have received a ‘personality disorder’ diagnosis or have relevant traits: a systematic review ”, was authored by Sarah Ikhtabi, Alexandra Pitman, Lucy Maconick, Eiluned Pearce, Oliver Dale, Sarah Rowe and Sonia Johnson.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul

A systematic review of the factors associated with the course of borderline personality disorder symptoms in adolescence

Gabriele skabeikyte.

Department of Clinical Psychology, Institute of Psychology, Faculty of Philosophy, Vilnius University, Universiteto st. 9, LT-01513 Vilnius, Lithuania

Rasa Barkauskiene

Associated data.

Not applicable.

Research on personality pathology in adolescence has accelerated during the last decade. Among all of the personality disorders, there is strong support for the validity of borderline personality disorder (BPD) diagnosis in adolescence with comparable stability as seen in adulthood. Researchers have put much effort in the analysis of the developmental pathways and etiology of the disorder and currently are relocating their attention to the identification of the possible risk factors associated with the course of BPD symptoms during adolescence. The risk profile provided in previous systematic reviews did not address the possible development and course of BPD features across time. Having this in mind, the purpose of this systematic review is to identify the factors that are associated with the course of BPD symptoms during adolescence.

Electronic databases were systematically searched for prospective longitudinal studies with at least two assessments of BPD as an outcome of the examined risk factors. A total number of 14 articles from the period of almost 40 years were identified as fitting the eligibility criteria.

Conclusions

Factors associated with the course of BPD symptoms include childhood temperament, comorbid psychopathology, and current interpersonal experiences. The current review adds up to the knowledge base about factors that are associated with the persistence or worsening of BPD symptoms in adolescence, describing the factors congruent to different developmental periods.

Adolescence is a sensitive period for various psychological disturbances, including personality pathology [ 1 ]. During normative development, children’s maladaptive personality traits (such as emotional instability, neuroticism) tend to decline with age [ 2 , 3 ]. However, there is a part of adolescents who diverge from the norm and whose personality problems tend to persist or even increase as adolescents enter young adulthood [ 1 ]. During the last decades researchers interested in adolescent personality pathology have mostly explored borderline personality disorder (BPD) which is characterized by turbulent interpersonal relationships, emotional instability, and an unstable sense of self [ 4 ]. Rejecting the hypothesis about adolescents’ difficulties only as a “storm and stress” period, there is strong support for the validity of a personality disorder (PD) diagnosis in adolescence with similar rank order stability in adolescents when compared with these features dynamics in adulthood [ 5 , 6 ].

Personality disturbance does not simply manifest in adulthood, thus, research exploring the developmental precursors in young people with elevated personality disturbance create an opportunity to understand specific vulnerabilities and prodromal features, which may later turn into the emergence of a clinical disorder [ 7 – 9 ]. This notion is especially significant in adolescence when personality disorder is emerging and can be diagnosed in its early stage, but borderline symptoms are still flexible, making this developmental period an advantageous stage to intervene [ 10 ]. Furthermore, unrecognized borderline pathology during this developmental period has the potential to derail developmental achievements and disrupt the transition to adulthood [ 11 – 14 ].

Research on personality disorders in adolescence have started to accelerate during the last decade. While much effort has been put into the analysis of the etiology of BPD, scientists offer two important research directions: firstly, research must include repeated assessment of BPD during developmentally sensitive windows that may capture the course of the disorder in periods of peak prevalence [ 15 ]. Secondly, Chanen et al. (2017) offered that public health research priorities should be allocated in a way that the data would build up a knowledge base which would help to understand the risk factors for the persistence or worsening of problems, rather than the onset of the disorder itself [ 10 ].

Existing systematic reviews mainly focus on the examination of risk factors associated with the emergence or current mean levels of BPD symptoms and identify factors crossing multiple domains (e.g. social, family, maltreatment, child characteristics) [ 15 – 18 ]. However, they are lacking data about the course of already existing symptoms and factors that might contribute to the increases or decreases in BPD symptoms during adolescence. Moreover, most of the studies include adolescent as well as adult samples in their analysis which does not allow to capture risk factors specifically relevant to adolescence [ 15 – 17 ]. Based on the shortcomings arising from previous reviews, the purpose of the current systematic review is to identify the factors that are associated with the course of borderline personality disorder symptoms during adolescence.

This systematic review was conducted using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The protocol was registered with PROSPERO in April of 2019 (registration no. CRD42019130158).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To identify studies for inclusion, the following electronic databases were systematically searched: MEDline, PubMed, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, socINDEX, Proquest and Scopus. Search terms from which all possible variations were searched are listed in Table 1 . Studies were limited to peer-reviewed articles written in English language and published from January of 1980 until March of 2020.

Search terms used in the electronic database search

Research methodology was based on the lacking theoretical aspects and limitations from the previous reviews: 1) Only prospective based longitudinal studies with a minimum of two time point intervals were included since previous reviews mostly evaluated the predictors of the mean levels of BPD, but failed to capture the actual change of BPD symptoms across time. 2) Research studies that describe only aspects of borderline personality disorder (e.g. self-harm, identity), but do not cover the entity of symptoms characterizing the clinical disorder were excluded as well as intervention studies. Studies that longitudinally assessed borderline personality symptoms as a dependent variable without the analysis of associated factors were excluded. Studies were included if they examined borderline personality symptoms or features as an outcome of the study. 3) In accordance with recent data indicating the importance of the extended developmental period from puberty to emerging adulthood for the early recognition of BPD [ 11 ], the study participants were adolescents aged 10 to 18 years old or adolescents as part of a ‘youth’ sample (e.g. 15–25 years old). Children under age 10 and adults older than 18 years of age, except for those who were part of the youth sample described previously, were excluded.

Selection of articles

Search results were transferred to a web-based tool “Covidence” which is designed for primary screening and data extraction (Cochrane, 2015). A total of 618 articles were identified through a database search. First of all, 375 duplicates were found and removed, leaving 243 articles for screening by title and abstract. Out of all studies, 189 did not meet the eligibility criteria for the analysis. After a full-text analysis by two reviewers, 40 studies were excluded on the basis of inappropriate study design, outcomes, measurement methods, or population. At each step, disagreements were resolved through a discussion and if necessary, a third reviewer helped to find a solution. A total of 14 studies, which provided longitudinal data about BPD symptoms and related features across adolescence, were included in the final analysis. Search results were summarized in a PRISMA chart (Fig. 1 ).

PRISMA diagram showing study selection process

At the next step, the quality of the selected studies was assessed using the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (National Health Institute, 2014). Two reviewers conducted independent assessments and overall quality ratings were categorized through a discussion as ‘good’, ‘fair’ “or ‘poor’ ( see Table 2 ). Out of all studies, nine of them were rated as ‘good’ and five – ‘fair’. No studies were rated as poor, indicating an overall sufficient quality of the selected articles.

Summary of risk of bias within studies

Y yes, N no, CD cannot determine, NR not reported, NA not applicable

Description of studies

A total of 14 studies were identified as appropriate for inclusion in further analysis. Key ideas from the articles were extracted and categorized by two reviewers. The following categories were described: study details (authors, year, country), study design, population (clinical or community), sample characteristics (sex, age range, sample size), sociodemographic data and outcome assessment methods. The main characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 3 .

Characteristics of included studies

1 self-report instrument; 2 clinical interview; NR not reported

Out of all studies, ten of them were conducted in the U.S., two in Canada, one in Finland, and one in Germany. Six studies were based on the same study population, however, they analysed different aspects of the topic. Duration of the studies ranged from one to ten years, and population in the studies ranged from 113 to 2344 participants at baseline assessment. In seven studies females formed a full sample, two study samples were formed of 70–80% females, while in five other studies participants were more equally distributed by gender, with girls constituting 52–58% of the sample. Participants’ age ranged from 10 to 24 years of age. Twelve studies were based on community samples and two on (in) outpatient samples. Outcomes of the studies mostly were measured by self-rating scales of borderline personality disorder symptoms, except three studies that included structured clinical interviews for the assessment of BPD symptoms. All of the methods used in the studies were based on the DSM-IV or ICD-10 symptom-oriented approach towards personality disorders.

Main results of the current review

The results revealed a large heterogeneity of the studies in terms of the reported analyses of BPD symptoms, course, domains of the associated factors, and their timing as predictors. First, in line with the previous research on normative personality development [ 2 , 5 ], authors of the majority of the studies (10 of 14) report data about the general decreasing trajectory of BPD symptoms during adolescence which was seen both in the community and in the clinical samples. However, there is a part of youth who deviate from the normative developmental trajectory and fall into the persisting BPD symptoms group in the clinical sample (76% of adolescents) [ 23 ] and into the elevated/rising (24% of adolescents; 74% girls) or intermediate/stable BPD symptoms groups (42% of adolescents; 54% girls) in the community sample [ 25 ]. Second, as the purpose of this review suggests, only factors that were longitudinally associated with increases or decreases in the mean levels of BPD symptoms as an outcome, will be included. Presented studies will further be categorized based on the domain of the associated factors that were examined. The detailed classification of the analysed factors is presented in Table 4 .

The classification of the analysed factors based on the factor domain and study sample

a community sample; b clinical sample;

NR not reported

Child characteristics

The most examined domain of the factors associated with the course of BPD symptoms during adolescence was child characteristics. To start with, temperament dimensions, such as high levels of emotionality, activity and low levels of sociability and shyness in middle childhood were predictive of higher elevations as well as increases in average levels of BPD features through adolescence [ 28 ]. In contrast, negative affectivity assessed in early and middle adolescence was only predictive of higher mean levels of BPD [ 6 ], but not anymore of the change in these features over time [ 21 ]. Moreover, the data further suggest that the link between negative affectivity in early adolescence and increases in the mean levels of BPD features from middle adolescence is not a direct one, but rather mediated by decreases in self-control skills [ 24 ].

Among other child-related factors, the authors also have evaluated the role of stressful life events (suspension from school, death of a parent, changes in peer acceptance, etc.) at ages 12–17 in the clinical sample, but did not found statistically significant associations [ 23 ]. In the community sample, general academic functioning measured by the standardized assessment procedure at age 8 was not statistically predictive of changes in BPD features during adolescence [ 25 ].

Adolescent psychopathology as a predictor of BPD symptom changes was analysed in eight of the fourteen studies. Within the community samples, it was found that childhood psychopathology, such as inattention, oppositional behaviour, and hyperactivity/impulsivity predicted the change to the new onset status of BPD in adolescence [ 29 ]. In line with previous findings, impulsivity and oppositional defiant disorder severity assessed in adolescence were also associated with higher average levels of BPD symptoms throughout adolescence [ 21 ]. Furthermore, it was identified that alcohol use disorder (AUD), drug use disorder (DUD), major depressive disorder (MDD) symptoms [ 20 ], anxiety symptoms, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms and somatization [ 25 ] statistically significantly predicted the changes in BPD features during adolescence. Specifically, higher average levels and increases in AUD, DUD, and MDD symptoms were associated with a slower decline of BPD symptoms through adolescence [ 20 ]. Adolescent-reported symptoms of ADHD and somatization also predicted the elevated or rising symptom trajectory, while parent-reported anxiety levels predicted stable intermediate levels of BPD features [ 25 ]. Moreover, individual social and physical aggression trajectories from childhood through adolescence were not significantly related to the BPD symptoms change from age 14 to 18 [ 22 ].