Advertisement

Language and communication in international students’ adaptation: a bibliometric and content analysis review

- Open access

- Published: 12 July 2022

- Volume 85 , pages 1235–1256, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Michał Wilczewski ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7650-5759 1 &

- Ilan Alon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6927-593X 2 , 3

15k Accesses

13 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This article systematically reviews the literature (313 articles) on language and communication in international students’ cross-cultural adaptation in institutions of higher education for 1994–2021. We used bibliometric analysis to identify the most impactful journals and articles, and the intellectual structure of the field. We used content analysis to synthesize the results within each research stream and suggest future research directions. We established two major research streams: second-language proficiency and interactions in the host country. We found inconclusive results about the role of communication with co-nationals in students’ adaptation, which contradicts the major adaptation theories. New contextualized research and the use of other theories could help explain the contradictory results and develop the existing theories. Our review suggests the need to theoretically refine the interrelationships between the interactional variables and different adaptation domains. Moreover, to create a better fit between the empirical data and the adaptation models, research should test the mediating effects of second-language proficiency and the willingness to communicate with locals. Finally, research should focus on students in non-Anglophone countries and explore the effects of remote communication in online learning on students’ adaptation. We document the intellectual structure of the research on the role of language and communication in international students’ adaptation and suggest a future research agenda.

Similar content being viewed by others

2.4 Discourses of Intercultural Communication and Education

Language Teachers on Study Abroad Programmes: The Characteristics and Strategies of Those Most Likely to Increase Their Intercultural Communicative Competence

English Language Studies: A Critical Appraisal

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One of the consequences of globalization is the changing landscape of international higher education. Over the past two decades, there has been a major increase in the number of international students, that is, those who have crossed borders for the purpose of study (OECD, 2021a ), from 1.9 million in 1997 to over 6.1 million in 2019 (UIS Statistics, 2021 ). Even students who are motivated to develop intercultural competence by studying abroad (Jackson, 2015 ) face several challenges that prevent them from benefitting fully from that experience. Examples of these challenges include language and communication difficulties, cultural and educational obstacles affecting their adaptation, socialization, and learning experiences (Andrade, 2006 ), psychological distress (Smith & Khawaja, 2011 ), or social isolation and immigration and visa extension issues caused by Covid-19 travel restrictions (Hope, 2020 ).

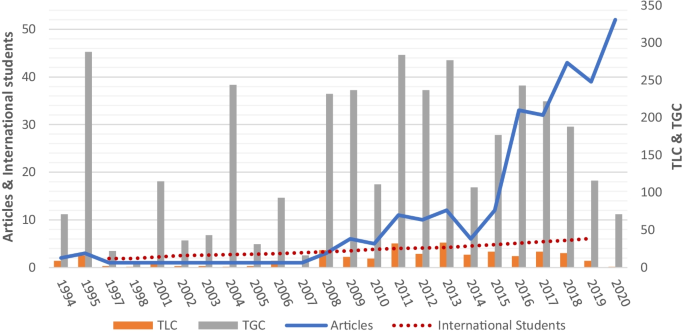

Cross-cultural adaptation theories and empirical research (for reviews, see Andrade, 2006 ; Smith & Khawaja, 2011 ) confirm the critical importance of foreign-language and communication skills and transitioning to the host culture for a successful academic and social life. Improving our understanding of the role of foreign-language proficiency and communication in students’ adaptation is important as the number of international students in higher education worldwide is on the rise. This increase has been accompanied by a growing number of publications on this topic over the last decade (see Fig. 1 ). Previous reviews of the literature have identified foreign-language proficiency and communication as predictors of students’ adaptation and well-being in various countries (Smith & Khawaja, 2011 ). The most recent reviews (Jing et al., 2020 ) list second-language acquisition and cross-cultural adaptation as among the most commonly studied topics in international student research. However, to date, there are no studies specifically examining the role of language and communication in international students’ adaptation (henceforth “language and communication in student adaptation”). This gap is especially important given recent research promoting students’ self-formation (Marginson, 2014 ) and reciprocity between international and domestic students (Volet & Jones, 2012 ). The results challenge the traditional “adjustment to the host culture” paradigm whereby international students are treated as being out of sync with the host country’s norms (Marginson, 2014 ). Thus, this article differs from prior research by offering a systematic and in-depth review of the literature on language and communication in student adaptation using bibliometric co-citation analysis and qualitative content analysis. Our research has a methodological advantage in using various bibliometric tools, which should improve the validity of the results.

Source: HistCite). Note . TLC, total local citations received; TGC, total global citations received; Articles, number of articles published in the field; International Students, number (in millions) of international students worldwide (UIS Statistics, 2021 )

Yearly publication of articles on language and communication in student adaptation (

We focus on several questions:

What are the most impactful journals and articles about the role of language and communication in student adaptation?

What is the thematic structure of the research in the field?

What are the leading research streams investigating language and communication in student adaptation?

What are the effects of language and communication on student adaptation?

What are the future research directions?

After introducing the major concepts related to language and communication in student adaptation and the theoretical underpinnings of the field, we present our methodology. Using bibliometric and content analysis, we track the development of the field and identify the major themes, research streams, and studies that have shaped the state-of-the art and our current knowledge about the role of language and communication in student adaptation. Finally, we suggest avenues for future research.

Defining the concepts and theories related to language and communication in student adaptation

Concepts related to language and communication.

Culture is a socially constructed reality in which language and social practices interact to construct meanings (Burr, 2006 ). In this social constructionist perspective, language is viewed as a form of social action. Intertwined with culture, it allows individuals to communicate their knowledge about the world, as well as the assumptions, opinions, and viewpoints they share with other people (Kramsch, 1998 ). In this sense, people identify themselves and others through the use of language, which allows them to communicate their social and cultural identity (Kramsch, 1998 ).

Intercultural communication refers to the process of constructing shared meaning among individuals with diverse cultural backgrounds (Piller, 2007 ). Based on the research traditions in the language and communication in student adaptation research, we view foreign or second-language proficiency , that is, the skill allowing an individual to manage communication interactions in a second language successfully (Gallagher, 2013 ), as complementary to communication (Benzie, 2010 ).

Cross-cultural adaptation

The term adaptation is used in the literature interchangeably with acculturation , adjustment , assimilation , or integration . Understood as a state, cultural adaptation refers to the degree to which people fit into a new cultural environment (Gudykunst and Hammer, 1988 ), which is reflected in their psychological and emotional response to that environment (Black, 1990 ). In processual terms, adaptation is the process of responding to the new environment and developing the ability to function in it (Kim, 2001 ).

The literature on language and communication in student adaptation distinguishes between psychological, sociocultural, and academic adaptation. Psychological adaptation refers to people’s psychological well-being, reflected in their satisfaction with relationships with host nationals and their functioning in the new environment. Sociocultural adaptation is the individual’s ability to fit into the interactive aspects of the new cultural environment (Searle and Ward, 1990 ). Finally, academic adaptation refers to the ability to function in the new academic environment (Anderson, 1994 ). We will discuss the results of the research on language and communication in student adaptation with reference to these adaptation domains.

Theoretical underpinnings of language and communication in student adaptation

We will outline the major theories used in the research on international students and other sojourners, which has recognized foreign-language skills and interactions in the host country as critical for an individual’s adaptation and successful international experience.

The sojourner adjustment framework (Church, 1982 ) states that host-language proficiency allows one to establish and maintain interactions with host nationals, which contributes to one’s adaptation to the host country. In turn, social connectedness with host nationals protects one from psychological distress and facilitates cultural learning.

The cultural learning approach to acculturation (Ward et al., 2001 ) states that learning culture-specific skills allows people to handle sociocultural problems. The theory identifies foreign-language proficiency (including nonverbal communication), communication competence, and awareness of cultural differences as prerequisites for successful intercultural interactions and sociocultural adaptation (Ward et al., 2001 ). According to this approach, greater intercultural contact results in fewer sociocultural difficulties (Ward and Kennedy, 1993 ).

Acculturation theory (Berry, 1997 , 2005 ; Ward et al., 2001 ) identifies four acculturation practices when interacting with host nationals: assimilation (seeking interactions with hosts and not maintaining one’s cultural identity), integration (maintaining one’s home culture and seeking interactions with hosts), separation (maintaining one’s home culture and avoiding interactions with hosts), and marginalization (showing little interest in both maintaining one’s culture and interactions with others) (Berry, 1997 ). Acculturation theory postulates that host-language skills help establish supportive social and interpersonal relationships with host nationals and, thus, improve intercultural communication and sociocultural adjustment (Ward and Kennedy, 1993 ).

The anxiety/uncertainty management (AUM) theory (Gudykunst, 2005 ; Gudykunst and Hammer, 1988 ) states that intercultural adjustment is a function of one’s ability to cope with anxiety and uncertainty caused by interactions with hosts and situational processes. People’s ability to communicate effectively depends on their cognitive resources (e.g., cultural knowledge), which helps them respond to environmental demands and ease their anxiety.

The integrative theory of communication and cross-cultural adaptation (Kim, 2001 ) posits that people’s cultural adaptation is reflected in their functional fitness, meaning, the degree to which they have internalized the host culture’s meanings and communication symbols, their psychological well-being, and the development of a cultural identity (Kim, 2001 ). Communication with host nationals improves cultural adaptation by providing opportunities to learn about the host country’s society and culture, and developing intercultural communication competence that includes the ability to receive and interpret comprehensible messages in the host environment.

The intergroup contact theory (Allport, 1954 ; Pettigrew, 2008 ) states that contact between two distinct groups reduces mutual prejudice under certain conditions: when groups have common goals and equal status in the social interaction, exhibit intergroup cooperation, and have opportunities to become friends. Intercultural contact reduces prejudice toward and stereotypical views of the cultural other and provides opportunities for cultural learning (Allport, 1954 ).

These theories provide the theoretical framework guiding the discussion of the results synthesized through the content analysis of the most impactful articles in the field.

Methodology

Bibliometric and content analysis methods.

We used a mixed-method approach to review the research on language and communication in student adaptation for all of 1994–2021. This timeframe was informed by the data extraction process described in the next section. Specifically, we conducted quantitative bibliometric analyses such as co-citation analysis, keyword co-occurrence analysis, and conceptual thematic mapping, as well as qualitative content analysis to explore the research questions (Bretas & Alon, 2021 ).

Bibliometric methods use bibliographic data to identify the structures of scientific fields (Zupic and Čater, 2015 ). Using these methods, we can create an objective view of the literature by making the search and review process transparent and reproducible (Bretas and Alon, 2021 ). First, we measured the impact of the journals and articles by retrieving data from HistCite concerning the number of articles per journal and citations per article. We analyzed the number of total local citations (TLC) per year, that is, the number of times an article has been cited by other articles in the same literature (313 articles in our sample). We then analyzed the total global citations (TGC) each article received in the entire Web of Science (WoS) database. We also identified the trending articles in HistCite by calculating the total citation score (TLCe) at the end of the year covered in the study (mid-2021). This score rewards articles that received more citations within the last three years (i.e., up to the beginning of 2018). Using this technique, we can determine the emerging topics in the field because it considers not only articles with the highest number of citations received over a fixed period of time, but also those that have been cited most frequently in recent times (Alon et al., 2018 ).

Second, to establish a general conceptual structure of the field, we analyzed the co-occurrence of authors’ keywords using VOS software. Next, based on the authors’ keywords, we plotted a conceptual map using Biblioshiny (a tool for scientific mapping analysis that is part of the R bibliometrix-package) to identify motor, basic, niche, and emerging/declining themes in the field (Bretas and Alon, 2021 ).

Third, to determine specific research streams and map patterns within the field (Alon et al., 2018 ), we used the co-citation mapping techniques in HistCite that analyze and visualize citation linkages between articles (Garfield et al., 2006 ) over time.

Next, we used content analysis to synthesize the results from the 31 most impactful articles in the field. We analyzed the results within each research stream and discussed them in light of the major adaptation theories to suggest future research directions and trends within each research stream (Alon et al., 2018 ). Content analysis allows the researcher to identify the relatively objective characteristics of messages (Neuendorf, 2002 ). Thus, this technique enabled us to verify and refine the results produced by the bibliometric analysis, with the goal of improving their validity.

Data extraction

We extracted the bibliographic data from Clarivate Analytics’ WoS database that includes over 21,000 high-quality, peer-reviewed scholarly journals (as of July 2020 from clarivate.libguides.com). We adopted a two-stage data extraction approach (Alon et al., 2018 ; Bretas and Alon, 2021 ). Table 1 describes the data search and extraction processes.

First, in June 2021, we used keywords that would best cover the researched topic by searching for the following combinations of terms: (a) “international student*” OR “foreign student*” OR “overseas student*” OR “study* abroad” OR “international education”—to cover international students as a specific sojourner group; (b) “language*” and “communicat*”—to cover research on foreign-language proficiency as well as communication issues; and (c) “adapt*” OR “adjust*” OR “integrat*” OR “acculturat*”—to cover the adaptation aspects of the international students’ experience. However, given that cross-cultural adaptation is reflected in an individual’s functional fitness, psychological well-being, and development of a cultural identity (Kim, 2001 ), we included two additional terms in the search: “identit*” OR “satisf*”—to cover the literature on the students’ identity issues and satisfaction in the host country. Finally, based on a frequency analysis of our data extracted in step 2, we added “cultur* shock” in step 3 to cover important studies on culture shock as one of critical aspects of cross-cultural adaptation (Gudykunst, 2005 ; Pettigrew, 2008 ; Ward et al., 2001 ). After refining the search by limiting the data to articles published in English, the extraction process yielded 921 sources in WoS.

In the second stage, we refined the extraction further through a detailed examination of all 921 sources. We carefully read the articles’ abstracts to identify those suitable for further analysis. If the abstracts did not contain one or more of the three major aspects specified in the keyword search (i.e., international student, language and communication, adaptation), we studied the whole article to either include or exclude it. We did not identify any duplicates, but we removed book chapters and reviews of prior literature that were not filtered out by the search in WoS. Moreover, we excluded articles that (a) reported on students’ experiences outside of higher education contexts; (b) dealt with teaching portfolios, authors’ reflective inquiries, or anecdotal studies lacking a method section; (c) focused on the students’ experience outside the host country or on the experience of other stakeholders (e.g., students’ spouses, expatriate academics); (d) used the terms “adaptation,” “integration,” or “identity” in a sense different from cultural adaptation (e.g., adaptation of a syllabus/method/language instruction; integration of research/teaching methods/technology; “professional” but not “cultural” identity); or (e) used language/communication as a dependent rather than an independent variable. This process yielded 313 articles relevant to the topic. From them, we extracted the article’s title, author(s) names and affiliations, journal name, number, volume, page range, date of publication, abstract, and cited references for bibliometric analysis.

In a bibliometric analysis, the article is the unit of analysis. The goal of the analysis is to demonstrate interconnections among articles and research areas by measuring how many times the article is (co)cited by other articles (Bretas & Alon, 2021 ).

- Bibliometric analysis

Most relevant journals and articles

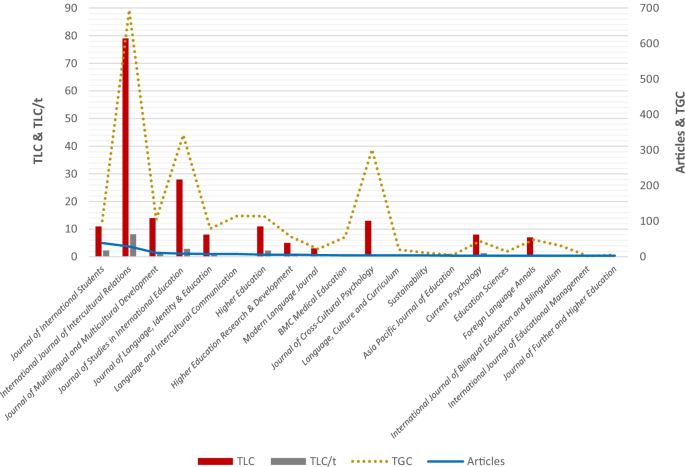

We addressed research question 1 regarding the most impactful journals and articles about the role of language and communication in student adaptation by identifying the most relevant journals and articles. Figure 2 lists the top 20 journals publishing in the field. The five most influential journals in terms of the number of local and global citations are as follows: International Journal of Intercultural Relations (79 and 695 citations, respectively), Journal of Studies in International Education (28 and 343 citations, respectively), Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development (14 and 105 citations, respectively), Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology (13 and 302 citations, respectively), and Higher Education (11 and 114 citations, respectively),

Source: HistCite). Note . TLC, total local citations received; TLC/t, total local citations received per year; TGC, total global citations received; Articles, number of articles published in the field

Top 20 journals publishing on language and communication in student adaptation (

Table 2 lists the 20 most influential and trending articles as measured by, respectively, local citations (TLC) and trending local citations at the end of the period covered (TLCe), that is, mid-2021. The most locally cited article was a qualitative study of Asian students’ experiences in New Zealand by Campbell and Li ( 2008 ) (TLC = 12). That study, which linked host-language proficiency with student satisfaction and effective communication in academic contexts, also received the highest number of global citations per year (TGC/t = 7.86). The most influential article in terms of total local citations per year was a quantitative study by Akhtar and Kröner-Herwig ( 2015 ) (TLC/t = 1.00) who linked students’ host-language proficiency, prior international experience, and age with acculturative stress among students in Germany. Finally, Sam’s ( 2001 ) quantitative study, which found no relationship between host-language and English proficiency and having a local friend on students’ satisfaction with life in Norway, received the most global citations (TGC = 115).

The most trending article (TLCe = 7) was a quantitative study by Duru and Poyrazli ( 2011 ) who considered the role of social connectedness, perceived discrimination, and communication with locals and co-nationals in the sociocultural adaptation of Turkish students in the USA. The second article with the most trending local citations (TLCe = 5) was a qualitative study by Sawir et al. ( 2012 ) who focused on host-language proficiency as a barrier to sociocultural adaptation and communication in the experience of students in Anglophone countries.

Keyword co-occurrence analysis

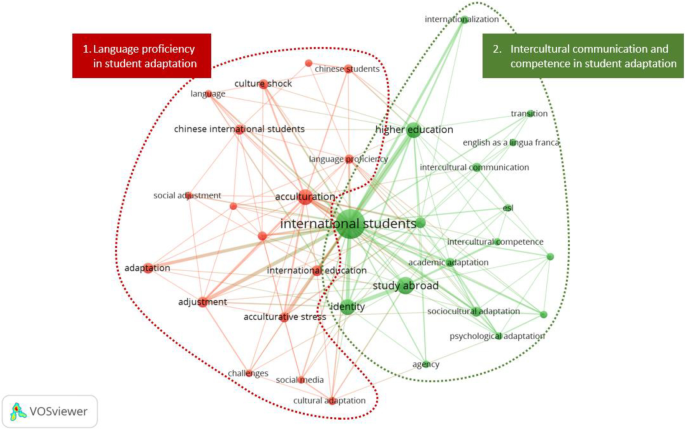

We addressed research question 2 regarding the thematic structure of the research in the field by analyzing the authors’ keyword co-occurrences to establish the thematic structure of the field (Bretas and Alon, 2021 ; Donthu et al., 2020 ). Figure 3 depicts the network of keywords that occurred together in at least five articles between 1994 and 2021. The nodes represent keywords, the edges represent linkages among the keywords, and the proximity of the nodes and the thickness of the edges represent how frequently the keywords co-occurred (Donthu et al., 2020 ). The analysis yielded two even clusters with 17 keywords each. Cluster 1 represents the primary focus on the role of language proficiency in student adaptation. It includes keywords such as “language proficiency,” “adaptation,” “acculturative stress,” “culture shock,” and “challenges.” Cluster 2 represents the focus on the role of intercultural communication and competence in student adaptation. It includes keywords such as “intercultural communication,” “intercultural competence,” “academic/psychological/sociocultural adaptation,” and “transition.”

Source: VOS)

Authors’ keyword co-occurrence analysis (

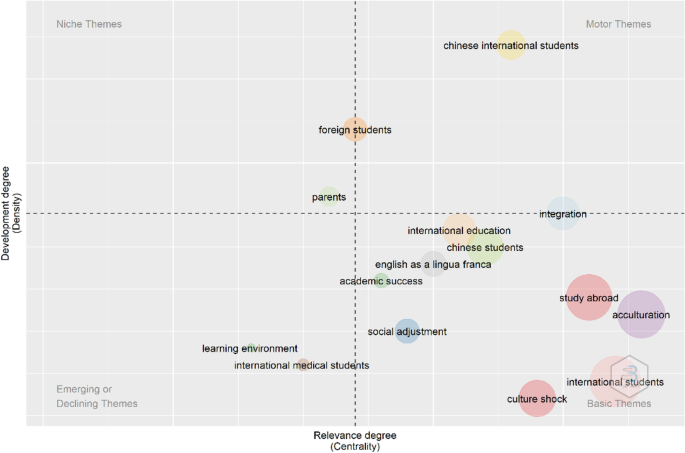

Conceptual thematic map

Based on the authors’ keywords, we plotted a conceptual map (see Fig. 4 ) using two dimensions. The first is density , which indicates the degree of development of the themes as measured by the internal associations among the keywords. The second is centrality , which indicates the relevance of the themes as measured by the external associations among the keywords. The map shows four quadrants: (a) motor themes (high density and centrality), (b) basic themes (low density and high centrality), (c) niche themes (high density and low centrality), and (d) emerging/declining themes (low density and centrality) (Bretas & Alon, 2021 ). The analysis revealed that motor themes in the field are studies of Chinese students’ experiences and student integration. Unsurprisingly, the basic themes encompass most topics related to language in student adaptation. Research examining the perspective of the students’ parents with regard to their children’s overseas experience exemplifies a niche theme. Finally, “international medical students” and “learning environment” unfold as emerging/declining themes. To determine if the theme is emerging or declining, we analyzed bibliometric data on articles relating to medical students’ adaptation and students’ learning environment. We found that out of 19 articles on medical students published in 13 journals (10 medicine/public health-related), 15 (79%) articles were published over the last five years (2016–2021), which clearly suggests an emerging trend. The analysis of authors’ keywords yielded only three occurrences of the keyword “learning environment” in articles published in 2012, 2016, and 2020, which may suggest an emerging trend. To further validate this result, we searched for this keyword in titles and abstracts and identified eight relevant articles published between 2016 and 2020, which supports the emerging trend.

Source: Biblioshiny)

Conceptual thematic map (

Citation mapping: research streams

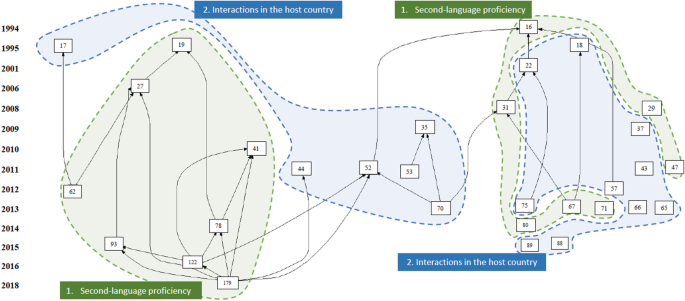

We addressed research question 3 regarding the leading research streams investigating language and communication in student adaptation by using co-citation mapping techniques to reveal how the articles in our dataset are co-cited over time. To produce meaningful results that would not trade depth for breadth in our large dataset (313 articles), we limited the search to articles with TGC ≥ 10 and TLC ≥ 3. These thresholds yielded the 31 articles (10% of the dataset) that are most frequently cited within and outside the dataset, indicating their driving force in the field. We analyzed these 31 articles further because their number corresponds with the suggested range of the most-cited core articles for mapping in HistCite (Garfield et al., 2006 ).

Figure 5 presents the citation mapping of these 31 articles. The vertical axis shows how the articles have been co-cited over time. Each node represents an article, the number in the box represents the location of the article in the entire dataset, and the size of the box indicates the article’s impact in terms of TLCs. The arrows indicate the citing direction between two articles. A closer distance between two nodes/articles indicates their similarity. Ten isolated articles in Fig. 5 have not been co-cited by other articles in the subsample of 31 articles.

Source: HistCite)

Citation mapping of articles on language and communication in student adaptation (

A content analysis of these 31 articles points to two major and quite even streams in the field: (a) “ second-language proficiency ” (16 articles) and (b) “ interactions in the host country ” involving second-language proficiency, communication competence, intercultural communication, and other factors (15 articles). We clustered the articles based on similar conceptualizations of language and communication and their role in student adaptation. As Fig. 5 illustrates, the articles formed distinct but interrelated clusters. The vertical axis indicates that while studies focusing solely on second-language proficiency and host-country interactions have developed relatively concurrently throughout the entire timespan, a particular interest in host-country interactions occurred in the second decade of research within the field (between 2009 and 2013). The ensuing sections present the results of the content analysis of the studies in each research stream, discussing the results in light of the major theories outlined before.

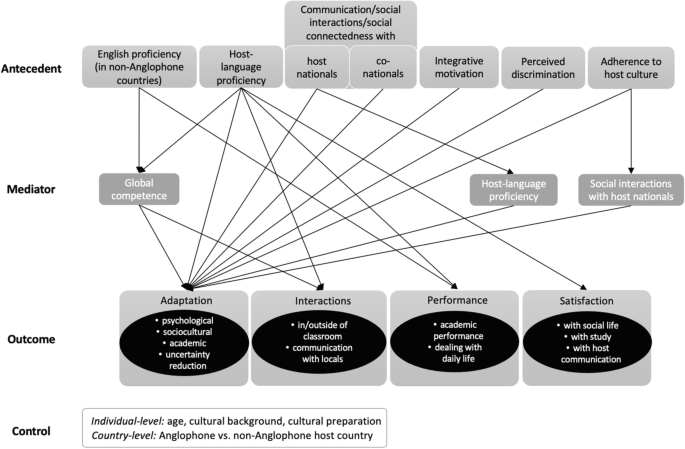

Content analysis

We sought to answer research question 4 regarding the effects of language and communication on student adaptation by synthesizing the literature within the previously established two research streams. The concept map in Fig. 6 illustrates the predictive effects of second-language proficiency and host-country interactions on various adaptation domains. Table 4 in the Appendix presents a detailed description of the synthesis and lists studies reporting these effects, underscoring inconclusive results.

A concept map synthesizing research on language and communication in student adaptation

Second-language proficiency

This research stream focuses on language barriers and the role of foreign-language proficiency in student adaptation. Having host-language proficiency predicts less acculturative stress (Akhtar and Kröner-Herwig, 2015 ), while limited host-language proficiency inhibits communication with locals and academic integration (Cao et al., 2016 ). These results are in line with the acculturation theory (Berry, 1997 , 2005 ; Ward et al., 2001 ) and the communication and cross-cultural adaptation theory (Kim, 2001 ). Cross ( 1995 ) suggested that social skills predict sociocultural rather than psychological (perceived stress, well-being) adaptation (Searle and Ward, 1990 ). Indeed, several qualitative studies have explained that the language barrier affects sociocultural adaptation by preventing students from establishing contacts with host nationals (Wang and Hannes, 2014 ), developing meaningful relationships (Sawir et al., 2012 ), and limiting occasions for cultural learning (Trentman, 2013 ), supporting the acculturation theory (Anderson, 1994 ; Church, 1982 ; Searle and Ward, 1990 ).

Moreover, insufficient host-language proficiency reduces students’ satisfaction by hampering their communication, socialization, and understanding of lectures in academic contexts (Campbell and Li, 2008 ). Similarly, language affects academic adaptation in students who have difficulty communicating with domestic students (Young and Schartner, 2014 ) or when used as a tool in power struggles, limiting students’ opportunities to speak up in class and participate in discussions or decision-making (Shi, 2011 ). Students who have limited host-language proficiency tend to interact with other international students, which exacerbates their separation from domestic students (Sawir et al., 2012 ). These findings again confirm the theories of acculturation (Berry, 1997 ; Ward et al., 2001 ) and communication and cross-cultural adaptation (Kim, 2001 ).

With regard to the acculturation theory (Berry, 1997 ; Ward and Kennedy, 1999 ), we found inconclusive results concerning the impact of foreign-language skills on students’ satisfaction and adaptation. Specifically, some studies (e.g., Sam, 2001 ; Ying and Liese, 1994 ) found this effect to be non-significant when tested in regression models. One explanation for this result might be the indirect effect of language on adaptation. For instance, Yang et al. ( 2006 ) established that host-language proficiency mediated the relationship between contact with host nationals and the psychological and sociocultural adjustment of students in Canada. Swami et al. ( 2010 ) reported that better host-language skills among Asian students in Britain predicted their adaptation partly because they had more contacts with host nationals. In turn, Meng et al. ( 2018 ) found that the relationship between foreign-language proficiency and social and academic adaptation was fully mediated by global competence (understood as “intercultural competence” or “global mindset”) in Chinese students in Belgium.

Interactions in the host country

The second research stream comprises studies taking a broader look at language and communication in student adaptation by considering both individual and social interaction contexts: second-language (host-language and English) proficiency; willingness to communicate in the second language; communication interactions with domestic and international students, host nationals, and co-nationals; social connectedness (i.e., a subjective awareness of being in a close relationship with the social world; Lee and Robbins, 1998 ; and integrative motivation (i.e., a positive affective disposition towards the host community; Yu, 2013 .

Host-language proficiency predicts academic (Hirai et al., 2015 ; Yu, 2013 ), psychological (Hirai et al., 2015 ; Rui and Wang, 2015 ), and sociocultural adaptation (Brown, 2009 ; Duru and Poyrazli, 2011 ), confirming the acculturation theory (Ward et al., 2001 ). However, although some studies (Hirai et al., 2015 ; Yu, 2013 ) confirmed the impact of host-language proficiency on academic adaptation, they found no such impact on sociocultural adaptation. Yu’s ( 2013 ) study reported that sociocultural adaptation depends on academic adaptation rather than on host-language proficiency. Moreover, host-language proficiency increases the students’ knowledge of the host culture, reduces their uncertainty, and promotes intercultural communication (Gallagher, 2013 ; Rui and Wang, 2015 ), supporting the central aspects of the AUM theory (Gudykunst, 2005 ).

In turn, by enabling communication with academics and peers, second-language proficiency promotes academic (Yu and Shen, 2012 ) and sociocultural adaptation, as well as social satisfaction (Perrucci and Hu, 1995 ). It also increases the students’ willingness to communicate in non-academic contexts. This willingness mediates the relationship between second-language proficiency and cross-cultural difficulties among Asian students in England (Gallagher, 2013 ). This finding may explain inconclusive results concerning the relationship between second-language proficiency and cultural adaptation. It appears that second-language proficiency alone is insufficient for successful adaptation. This proficiency should be coupled with the students’ willingness to initiate intercultural communication to cope with communication and cultural difficulties, which is compatible with both the AUM theory and Kim’s ( 2001 ) communication and cross-cultural adaptation theory.

As mentioned before, host-language proficiency facilitates adaptation through social interactions. Research demonstrates that communication with domestic students predicts academic satisfaction (Perrucci and Hu, 1995 ) and academic adaptation (Yu and Shen, 2012 ), confirming Kim’s ( 2001 ) theory. Moreover, the frequency of interaction (Zimmermann, 1995 ) and direct communication with host nationals (Rui and Wang, 2015 ) predict adaptation and reduce uncertainty, supporting the AUM theory. Zhang and Goodson ( 2011 ) found that social interactions with host nationals mediate the relationship between adherence to the host culture and sociocultural adaptation difficulties, confirming the acculturation theory (Berry, 1997 ), the intergroup contact theory (Allport, 1954 ; Pettigrew, 2008 ), and the culture learning approach in acculturation theory (Ward et al., 2001 ).

In line with the intergroup contact theory, social connectedness with host nationals predicts psychological and sociocultural adaptation (e.g., Hirai et al., 2015 ; Zhang and Goodson, 2011 ), confirming the sojourner adjustment framework (Church, 1982 ) and extending the acculturation framework (Ward and Kennedy, 1999 ) that recognizes the relevance of social connectedness for sociocultural adaptation only.

Research on interactions with co-nationals has produced inconclusive results. Some qualitative studies (Pitts, 2009 ) revealed that communication with co-nationals enhances students’ sociocultural adaptation and psychological and functional fitness for interacting with host nationals. Consistent with Kim’s ( 2001 ) theory, such communication may be a source of instrumental and emotional support for students when locals are not interested in contacts with them (Brown, 2009 ). Nonetheless, Pedersen et al. ( 2011 ) found that social interactions with co-nationals may cause psychological adjustment problems (e.g., homesickness), contradicting the acculturation theory (Ward and Kennedy, 1994 ), or increase their uncertainty (Rui and Wang, 2015 ), supporting the AUM theory.

Avenues for future research

We addressed research question 5 regarding future research directions through a content analysis of the 31 most impactful articles in the field. Importantly, all 20 trending articles listed in Table 1 were contained in the set of 31 articles. This outcome confirms the relevance of the results of the content analysis. We used these results as the basis for formulating the research questions we believe should be addressed within each of the two research streams. These questions are listed in Table 3 .

Research has focused primarily on the experience of Asian students in Anglophone countries (16 out of 31 most impactful articles), with Chinese students’ integration being the motor theme. This is not surprising given that Asian students account for 58% of all international students worldwide (OECD, 2021b ). In addition, Anglophone countries have been the top host destinations for the last two decades. The USA, the UK, and Australia hosted 49% of international students in 2000, while the USA, the UK, Canada, and Australia hosted 47% of international students in 2020 (Project Atlas, 2020 ). This fact raises the question of the generalizability of the research results across cultural contexts, especially given the previously identified cultural variation in student adaptation (Fritz et al., 2008 ). Thus, it is important to study the experiences of students in underexplored non-Anglophone host destinations that are currently gaining in popularity, such as China, hosting 9% of international students worldwide in 2019, France, Japan, or Spain (Project Atlas, 2020 ). Furthermore, future research in various non-Anglophone countries could precisely define the role of English as a lingua franca vs. host-language proficiency in international students’ experience.

The inconsistent results concerning the effects of communication with co-nationals on student adaptation (e.g., Pedersen et al., 2011 ; Pitts, 2009 ) indicate that more contextualized research is needed to determine if such communication is a product of or a precursor to adaptation difficulties (Pedersen et al., 2011 ). Given the lack of confirmation of the acculturation theory (Ward and Kennedy, 1994 ) or the communication and cross-cultural adaptation theory (Kim, 2001 ) in this regard, future research could cross-check the formation of students’ social networks with their adaptation trajectories, potentially using other theories such as social network theory to explain the contradictory results of empirical research.

Zhang and Goodson ( 2011 ) showed that social connectedness and social interaction with host nationals predict both psychological and sociocultural adaptation. In contrast, the sojourner adjustment framework (Ward and Kennedy, 1999 ) considered their impact on sociocultural adaptation only. Thus, future research should conceptualize the interrelationships among social interactions in the host country and various adaptation domains (psychological, sociocultural, and academic) more precisely.

Some studies (Brown, 2009 ; Gallagher, 2013 ; Rui and Wang, 2015 ) confirm all of the major adaptation theories in that host-language proficiency increases cultural knowledge and the acquisition of social skills, reduces uncertainty and facilitates intercultural communication. Nevertheless, the impact of language on sociocultural adaptation appears to be a complex issue. Our content analysis indicated that sociocultural adaptation may be impacted by academic adaptation (Yu, 2013 ) or does not occur when students do not engage in meaningful interactions with host nationals (Ortaçtepe, 2013 ). To better capture the positive sociocultural adaptation outcomes, researchers should take into account students’ communication motivations, together with other types of adaptation that may determine sociocultural adaptation.

Next, in view of some research suggesting the mediating role of second-language proficiency (Yang et al., 2006 ), contacts with host nationals (Swami et al., 2010 ), and students’ global competence (Meng et al., 2018 ) in their adaptation, future research should consider other non-language-related factors such as demographic, sociocultural, and personality characteristics in student adaptation models.

Finally, the conceptual map of the field established the experiences of medical students and the learning environment as an emerging research agenda. We expect that future research will focus on the experience of other types of students such as management or tourism students who combine studies with gaining professional experience in their fields. In terms of the learning environment and given the development and growing importance of online learning as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, future research should explore the effects of remote communication, both synchronous and asynchronous, in online learning on students’ adaptation and well-being.

This article offers an objective approach to reviewing the current state of the literature on language and communication in student adaptation by conducting a bibliometric analysis of 313 articles and a content analysis of 31 articles identified as the driving force in the field. Only articles in English were included due to the authors’ inability to read the identified articles in Russian, Spanish, or Chinese. Future research could extend the data search to other languages.

This review found support for the effects of language of communication on student adaptation, confirming major adaptation theories. Nevertheless, it also identified inconsistent results concerning communication with co-nationals and the complex effects of communication with host nationals. Thus, we suggested that future research better captures the adaptation outcomes by conducting contextualized research in various cultural contexts, tracking the formation of students’ social networks, and precisely conceptualizing interrelations among social interactions in the host country and different adaptation domains. Researchers should also consider students’ communication motivations and the mediating role of non-language-related factors in student adaptation models.

Akhtar, M., & Kröner-Herwig, B. (2015). Acculturative stress among international students in context of socio-demographic variables and coping styles. Current Psychology, 34 (4), 803–815. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-015-9303-4

Article Google Scholar

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice . Perseus Books.

Alon, I., Anderson, J., Munim, Z. H., & Ho, A. (2018). A review of the internationalization of Chinese enterprises. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 35 (3), 573–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-018-9597-5

Anderson, L. E. (1994). A new look at an old construct: Cross-cultural adaptation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 18 (3), 293–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(94)90035-3

Andrade, M. S. (2006). International students in English-speaking universities. Journal of Research in International Education, 5 (2), 131–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240906065589

Benzie, H. J. (2010). Graduating as a “native speaker”: International students and English language proficiency in higher education. Higher Education Research and Development, 29 (4), 447–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294361003598824

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 46 (1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x

Berry, J. W. (2005). Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29 (6), 697–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013

Black, J. S. (1990). The relationship of personal characteristics with the adjustment of Japanese expatriate managers. Management International Review, 30 (2), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.2307/40228014

Bretas, V. P. G., & Alon, I. (2021). Franchising research on emerging markets: Bibliometric and content analyses. Journal of Business Research, 133 , 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.067

Brown, L. (2009). Using an ethnographic approach to understand the adjustment journey of international students at a university in England. Advances in Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 3 , 101–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1871-3173(2009)0000003007

Burr, V. (2006). An introduction to social constructionism . Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Campbell, J., & Li, M. (2008). Asian students’ voices: An empirical study of Asian students’ learning experiences at a New Zealand University. Journal of Studies in International Education, 12 (4), 375–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315307299422

Cao, C., Zhu, C., & Meng, Q. (2016). An exploratory study of inter-relationships of acculturative stressors among Chinese students from six European union (EU) countries. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 55 , 8–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2016.08.003

Church, A. T. (1982). Sojourner adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 91 (3), 540–572. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.91.3.540

Cross, S. E. (1995). Self-construals, coping, and stress in cross-cultural adaptation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 26 (6), 673–697. https://doi.org/10.1177/002202219502600610

Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Ranaweera, C., Sigala, M., & Sureka, R. (2020). Journal of Service Theory and Practice at age 30: Past, present and future contributions to service research. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 31 (3), 265–295. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-10-2020-0233

Duru, E., & Poyrazli, S. (2011). Perceived discrimination, social connectedness, and other predictors of adjustment difficulties among Turkish international students. International Journal of Psychology, 46 (6), 446–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2011.585158

Fritz, M. V., Chin, D., & DeMarinis, V. (2008). Stressors, anxiety, acculturation and adjustment among international and North American students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32 (3), 244–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.01.001

Gallagher, H. C. (2013). Willingness to communicate and cross-cultural adaptation: L2 communication and acculturative stress as transaction. Applied Linguistics, 34 (1), 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/ams023

Garfield, E., Paris, S. W., & Stock, W. G. (2006). HistCite™ : A software tool for informetric analysis of citation linkage. Information, 57 (8), 391–400.

Google Scholar

Gudykunst, W. B., & Hammer, M. R. (1988). Strangers and hosts—An uncertainty reduction based theory of intercultural adaptation. In Y. Y. Kim & W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.), Cross-cultural adaptation: Current approaches (Vol. 11, pp. 106–139). Sage.

Gudykunst, W. B. (2005). An anxiety/uncertainty management (AUM) theory of strangers’ intercultural adjustment. In W. B. Gudykunst (Ed.), Theorizing about intercultural communication (pp. 419–457). Sage.

Hirai, R., Frazier, P., & Syed, M. (2015). Psychological and sociocultural adjustment of first-year international students: Trajectories and predictors. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62 (3), 438–452. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000085

Hope, J. (2020). Be aware of how COVID-19 could impact international students. The Successful Registrar, 20 (3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/tsr.30708

Hotta, J., & Ting-Toomey, S. (2013). Intercultural adjustment and friendship dialectics in international students: A qualitative study. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37 (5), 550–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.06.007

Jackson, J. (2015). Becoming interculturally competent: Theory to practice in international education. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 48 , 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.03.012

Jing, X., Ghosh, R., Sun, Z., & Liu, Q. (2020). Mapping global research related to international students: A scientometric review. Higher Education, 80 (3), 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10734-019-00489-Y

Khawaja, N. G., & Stallman, H. M. (2011). Understanding the coping strategies of international students: A qualitative approach. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 21 (2), 203–224. https://doi.org/10.1375/ajgc.21.2.203

Kim, Y. Y. (2001). Becoming intercultural: An integrative theory of communication and cross-cultural adaptation . Sage.

Kramsch, C. (1998). Language and culture . Oxford University Press.

Lee, R. M., & Robbins, S. B. (1998). The relationship between social connectedness and anxiety, self-esteem, and social identity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45 (3), 338–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.45.3.338

Marginson, S. (2014). Student self-formation in international education. Student Self-Formation in International Education, 18 (1), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315313513036

Meng, Q., Zhu, C., & Cao, C. (2018). Chinese international students’ social connectedness, social and academic adaptation: The mediating role of global competence. Higher Education, 75 (1), 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0129-x

Neuendorf, K. A. (2002). The content analysis guidebook (2nd ed.). Sage.

OECD (2021a). Education at a Glance 2021: OECD indicators . Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/b35a14e5-en .

OECD (2021b). What is the profile of internationally mobile students? https://doi.org/10.1787/5A49E448-EN

Ortaçtepe, D. (2013). “This is called free-falling theory not culture shock!”: A narrative inquiry on second language socialization. Journal of Language, Identity and Education, 12 (4), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2013.818469

Pedersen, E. R., Neighbors, C., Larimer, M. E., & Lee, C. M. (2011). Measuring sojourner adjustment among American students studying abroad. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35 (6), 881–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.06.003

Perrucci, R., & Hu, H. (1995). Satisfaction with social and educational experiences among international graduate students. Research in Higher Education, 36 (4), 491–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02207908

Pettigrew, T. F. (2008). Future directions for intergroup contact theory and research. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32 (3), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJINTREL.2007.12.002

Piller, I. (2007). Linguistics and Intercultural Communication. Language and Linguistics Compass, 1 (3), 208–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-818X.2007.00012.x

Pitts, M. J. (2009). Identity and the role of expectations, stress, and talk in short-term student sojourner adjustment: An application of the integrative theory of communication and cross-cultural adaptation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33 (6), 450–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.07.002

Project Atlas . (2020). https://iie.widen.net/s/rfw2c7rrbd/project-atlas-infographics-2020 . Accessed 15 September 2021.

Ruble, R. A., & Zhang, Y. B. (2013). Stereotypes of Chinese international students held by Americans. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37 (2), 202–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2012.12.004

Rui, J. R., & Wang, H. (2015). Social network sites and international students’ cross-cultural adaptation. Computers in Human Behavior, 49 , 400–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.041

Sam, D. L. (2001). Satisfaction with life among international students: An exploratory study. Social Indicators Research, 53 (3), 315–337. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007108614571

Sawir, E., Marginson, S., Forbes-Mewett, H., Nyland, C., & Ramia, G. (2012). International student security and English language proficiency. Journal of Studies in International Education, 16 (5), 434–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315311435418

Searle, W., & Ward, C. (1990). The prediction of psychological and sociocultural adjustment during cross-cultural transitions. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 14 (4), 449–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(90)90030-Z

Shi, X. (2011). Negotiating power and access to second language resources: A study on short-term Chinese MBA students in America. Modern Language Journal, 95 (4), 575–588. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01245.x

Smith, R. A., & Khawaja, N. G. (2011). A review of the acculturation experiences of international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35 (6), 699–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.08.004

Swami, V., Arteche, A., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2010). Sociocultural adjustment among sojourning Malaysian students in Britain: A replication and path analytic extension. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45 (1), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0042-4

Trentman, E. (2013). Imagined communities and language learning during study abroad: Arabic Learners in Egypt. Foreign Language Annals, 46 (4), 545–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12054

UIS Statistics . (2021). http://data.uis.unesco.org/Index.aspx?queryid=172# . Accessed 10 December 2021.

Volet, S., & Jones, C. (2012). Cultural transitions in higher education: Individual adaptation, transformation and engagement. Advances in Motivation and Achievement, 17 , 241–284. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0749-7423(2012)0000017012

Wang, Q., & Hannes, K. (2014). Academic and socio-cultural adjustment among Asian international students in the Flemish community of Belgium: A photovoice project. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 39 (1), 66–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.09.013

Ward, C., Bochner, S., & Furnham, A. (2001). The psychology of culture shock (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Ward, C., & Kennedy, A. (1993). Where’s the “culture” in cross-cultural transition? Comparative studies of sojourner adjustment. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 24 (2), 221–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022193242006

Ward, C., & Kennedy, A. (1994). Acculturation strategies, psychological adjustment, and sociocultural competence during cross-cultural transitions. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 18 (3), 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(94)90036-1

Ward, C., & Kennedy, A. (1999). The measurement of sociocultural adaptation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 23 (4), 659–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-1767(99)00014-0

Yang, R. P. J., Noels, K. A., & Saumure, K. D. (2006). Multiple routes to cross-cultural adaptation for international students: Mapping the paths between self-construals, English language confidence, and adjustment. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30 (4), 487–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.11.010

Ying, Y., & Liese, L. H. (1994). Initial adjustment of Taiwanese students to the United States: The impact of postarrival variables. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 25 (4), 466–477. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022194254003

Young, T. J., & Schartner, A. (2014). The effects of cross-cultural communication education on international students’ adjustment and adaptation. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 35 (6), 547–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2014.884099

Yu, B. (2013). Asian international students at an Australian university: Mapping the paths between integrative motivation, competence in L2 communication, cross-cultural adaptation and persistence with structural equation modelling. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 34 (7), 727–742. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.796957

Yu, B., & Shen, H. (2012). Predicting roles of linguistic confidence, integrative motivation and second language proficiency on cross-cultural adaptation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36 (1), 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.12.002

Zhang, J., & Goodson, P. (2011). Acculturation and psychosocial adjustment of Chinese international students: Examining mediation and moderation effects. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35 (5), 614–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.11.004

Zimmermann, S. (1995). Perceptions of intercultural communication competence and international student adaptation to an American campus. Communication Education, 44 (4), 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634529509379022

Zupic, I., & Čater, T. (2015). Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organizational Research Methods, 18 (3), 429–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114562629

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

This research is supported by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange grant “Exploring international students’ experiences across European and non-European contexts” [grant number PPN/BEK/2019/1/00448/U/00001] to Michał Wilczewski.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Applied Linguistics, University of Warsaw, Dobra 55, 00-312, Warsaw, Poland

Michał Wilczewski

Department of Economics and Business Administration, University of Ariel, 40700, Ariel, Israel

School of Business and Law, University of Agder, Gimlemoen 25, 4630, Kristiansand, Norway

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Both authors contributed to the study conception and design. Michał Wilczewski had the idea for the article, performed the literature search and data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Ilan Alon critically revised the work, suggested developments and revisions, and edited the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Michał Wilczewski .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Wilczewski, M., Alon, I. Language and communication in international students’ adaptation: a bibliometric and content analysis review. High Educ 85 , 1235–1256 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00888-8

Download citation

Accepted : 14 June 2022

Published : 12 July 2022

Issue Date : June 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00888-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Literature review

- Intercultural communication

- International student

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Internationalizing “International Communication”

Reviewed publication:.

Book Review on Internationalizing “International Communication ”, edited by Chin-Chuan Lee The University of Michigan Press, 2015, vi+332 pp.

The term international and global are interchangeably used in international communication. International often refers to the exchange of information and ideas between and among nations, regardless of economic standing, whereas global is intrinsically hegemonic, implying a one-way flow of power from the powerful to the powerless. The book Internationalizing “International Communication ” is believed to have opened up a different approach to studying communication in a cosmopolitan ecology across countries. Chin-Chuan Lee, the book’s editor, reflects critically on the field’s history and thoughtfully proposes, “scholars of international communication need the cultural confidence and epistemological autonomy to make their mark on global or cosmopolitan theory, which necessarily will entail borrowing, recasting, or reconceptualizing Western theories—the more the better, whatever help us elucidate and analyze rich local experiences and connect them to broader processes, whatever broaden our horizons and expand our repertoire, as long as we are not beholden to any purported final arbiter of universal truth” (p. 16).

In Chapter One, Lee challenges the implied universality of Americentric concepts and methodologies in communication research. Even in an increasingly globalized world where information moves freely across borders, these ideas retain the international designation as a method to signal that nation-states remain powerful actors in the production and distribution of media content. While Lee is careful not to dismiss any theory purely because of its origins, he does allow a broader range of intellectual traditions to participate in the discussion. This book is a bold step in that direction.

The subsequent fourteen chapters accept Lee’s invitation, resulting in a chorus of voices rarely heard in academic settings. Elihu Katz, for example, spends most of Chapter Two debating what it means to internationalize intercultural communication. He talks about his role in the launch of broadcast television in Israel, as well as the lessons he gained from the experience which he labelled as international communication research. He thinks that the international communication preceded national communication, rather than vice versa.

In Chapter Three, Tsan-Kuo Chang examines the theoretical implications of cultural imperialism, concluding that it “no longer fits the world of interconnected and interdependent nations in a global network society” (p. 61). According to the author, at a time when the field of international communication studies has expanded significantly in recent decades, the production and accumulation of knowledge have been less impressive. In fact, without keeping up with the times, the field has been regurgitating old ideas and obsolete perspectives.

In Chapter Four, Jan Servaes presents Thailand as a counterexample of a democratic nation with a non-Western media system, offering historical context for Western bias in previous four theories of the press. He talks about the importance of “internationalization” in journalism and media education, mentioning that professional journalism education is based on local or national parameters. According to him, apart from creating appropriate political and economic environments for an independent media system, it is crucial to educate journalists to the highest ethical and professional standards.

In Chapter Five, Paolo Mancini revisits research he co-authored in 2004 to assess how professional journalism has altered in the wake of polarized politics and social media activism. Even though journalists perceive there is a dominant model of journalism whose practices and principles are spreading over the world, and even if they claim to adopt and apply this normative framework, they behave in a completely different way in their daily activities. At the very least, there is a mismatch between journalism theory and practice.

Michael Curtin in Chapter Six argues that film studies have become sufficiently internationalized, with media capitals such as Mumbai competing with Hollywood for a slice of global markets while their products are consumed locally in unexpected ways, noting the Chinese film industry’s recent move from Hong Kong to Beijing as an inward turn. In Chapter Seven, Jaap van Ginneken takes a somewhat different approach, utilizing data from IMDb (an online database of information related to films) to illustrate that major Hollywood studios continue to dominate the film industry, owing in part to their commercial character. Even with blockbuster films like Avatar, he agrees with Curtin that audiences can discover their meaning.

Colin Sparks returns to the concept of cultural imperialism in Chapter Eight. Before proposing a narrower scope that captures how modern nation-states exploit media in fights over intellectual property, airwave regulation, and internet control, he points out the challenges with presuming a united national culture or single reading of literature. Silvio Waisbord warns against adopting an area studies approach and separating dialogues along narrow geopolitical lines, as media studies shift away from their Western concentration (e.g., East Asian media studies). Instead, he promotes a cosmopolitan viewpoint that places “local research in the context of global debates and trends, and engaging in conversations that transcend local interests and phenomena” (p. 187).

In Chapter Ten, Chin-Chuan Lee revisits Lerner’s (1958) and Rogers’ (2003) seminal views that encouraged him to pursue a career in international communication. Lee evaluates their strengths and flaws and proposes a Weberian approach ( Weber, 1930 , 1951 , 1978a , 1978b ) as an alternative to imposing Western-based theories on the rest of the world, with the specific/local dialectical interaction with the general/global. He also mentions that international communication is a creative fusion of local perspectives and global visions and that applying theories to explain our experiences should gain over appropriating our experiences to fit the theories.

The final four chapters provide insights into how Weber’s strategy would work in reality. Judy Polumbaum revisits her research in modern China in Chapter Eleven, looking at it through the lenses of Bourdieu and Johnson’s (1993) “fields of cultural production” and Giddens’ (1984) “theory of structuration”. In what appears to be a tightly regulated media environment, she reveals increasing tensions between the state and capital. She offered two additional guiding concepts for international communication research: circumstances and serendipity and proposed a third optional but highly recommended principle: whimsy.

Longxi Zhang investigates the historic and complicated relationship between East and West in Chapter Twelve, going to Marco Polo. He concludes that translation can still be applicable to challenge ethnocentrism and bridge cultural divides. He opines that translation across languages can provide a model because it most clearly poses communication questions.

Rodney Benson emphasizes the limitations and biases of significant ideas in current media studies, such as Habermas’ “public sphere” (1992) , Bourdieu and Johnson’s “fields” ( 1993 ), Castells’ “network society” (1996) , and Latour’s “actor-network theory” (2005) in Chapter Thirteen. They do not exhaust the possibilities for internationalizing media studies, but simply propose a spectrum of possible solutions, on which or against which future theorizing—both Western and non-Western—might build fruitfully. Therefore, in the digital age, he also highlights their potential to create greater understanding and collaboration between Western and non-Western researchers.

In Chapter Fourteen, Peter Dahlgren criticizes media studies as an excessively complacent and self-absorbed field. He sees cosmopolitanism as the most promising road ahead, yet one that necessitates civic engagement and acceptance of various research techniques. For international communication research, Dahlgren highlights the importance of the normative and cultural frameworks of civic international communication actors and comments that these can be refracted at least in part through the prism of cosmopolitanism.

The book ends with Arvind Rajagopal’s critical account of the meteoric rise of communication technology in India. He looks at how technology has exacerbated societal divisions and made violence more obvious, casting doubt on the Cold War-era premise that more access to visual media will inevitably lead to a transparent, rational society.

I found “Local Experiences, Cosmopolitan Theories”, by Chin-Chuan Lee, as the most informative and provocative chapter in the book. In this wonderful chapter, Lee concisely reviews the attempts in recent decades to internationalize media studies, exposing the inadequacy of those models, with an appropriate critique of uber-enthusiastic unipolarists like Francis Fukuyama. He also argues for a new way not just to examine the works of media, but to understand how communication and media impact the lives of media consumers across countries characterized by evolving digital ecology: cosmopolitanism. Lee states that “If international communication scholars are truly serious about achieving the goals of mutual understanding through cultural dialogue, it is imperative that we listen humbly to symphonic music whose harmonious unity has themes and variations and is made of a cacophony of instrumental sounds” (p.218).

International communication can transcend national and cultural boundaries in the acquisition of knowledge about cultural values, behavioral patterns, and interaction rules that enable effective transcultural interaction. As a result, transcultural communication must take the context into account. Transcultural perspectives add a significant new dimension to research by transcending, transgressing, and transforming borders across languages, communities, and cultures, which reflects the spirit of international communication. As a result, I believe that transcultural communication is a step in the right direction toward strengthening international communication.

Overall, this volume covers a diverse spectrum of viewpoints on what it takes to internationalize media and communication studies. At the same time, each author emphasizes the critical significance of controlling information overload, encouraging visual literacy, and engaging in fruitful debates over global, national, and local issues. Unfortunately, after fifteen chapters, the messages start to sound the same. In addition, several chapters of the book focus on Asia, for the book grew out of a conference held in Hong Kong. Nonetheless, I would have loved to see additional research from the world’s other underrepresented regions.

Ultimately, Internationalizing “International Communication” is a good starting point for a long-overdue discourse in media studies and other social science and humanities departments. I strongly recommend this volume for graduate or advanced undergraduate international communication courses, genuinely hoping that future academics adopt the suggested modifications in how such research is performed and received.

Bourdieu, P., & Johnson, R. (1993). The field of cultural production: Essays on art and literature . Columbia University Press. Search in Google Scholar

Castells, M. (1996). The rise of the network society . Blackwell. Search in Google Scholar

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration . University of California Press. Search in Google Scholar

Habermas, J. (1992). Further reflections on the public sphere. In C. Calhoun (Ed.), Habermas and the public sphere (pp. 421–461). MIT Press. Search in Google Scholar

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-theory . Oxford University Press. 10.1093/oso/9780199256044.001.0001 Search in Google Scholar

Lerner, D. (1958). The passing of traditional society: Modernizing the Middle East . Free Press. Search in Google Scholar

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press. Search in Google Scholar

Weber, M. (1930). The Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism . HarperCollins. Search in Google Scholar

Weber, M. (1951). The religion of China: Confucianism and taoism (E. Matthews, Trans.). Free Press. Search in Google Scholar

Weber, M. (1978a). Economy and society . University of California Press. 10.4159/9780674240827 Search in Google Scholar

Weber, M. (1978b). The logic of historical explanation (H. H. Gerth, Trans.). In W. G. Runciman (Eds.), Weber: Selections in translation (pp. 111–131). Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511810831.012 Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Kriti Bhuju, published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- X / Twitter

Supplementary Materials

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

Journal and Issue

Articles in the same issue.

- Search Menu

Advance Articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Why Submit?

- About Human Communication Research

- About International Communication Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Editor-in-Chief

Yariv Tsfati & Steven R. Wilson

Editorial board

Celebrating 50 years of Theory in Human Communication Research

To mark the journal's 50th anniversary, HCR has released a special issue reflecting on 50 years of theory in Human Communication Research , and where research can continue from here.

Read the latest content from Human Communication Research.

Highly cited articles

A selection of highly cited articles from recent years has been made free to read online.

Access articles

Email alerts

Stay up to date on the latest communications research with content alerts delivered to your email.

Publish your paper

Submit your paper to Human Communication Research .

Latest articles

Latest posts on x from hcr, latest posts on x from ica, international communication association, connect with ica.

Stay up to date with the latest news and content from ICA:

- Twitter: @icahdq

- Facebook: International Communication Association

Become an ICA Member

Join your peers, over 4,000 members globally, in seeking excellence in the communication field. Become a part ofthe ICA community today!

ICA Conferences

ICA holds a large annual conference and smaller regional conferences throughout the year.

Related Titles

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-2958

- Copyright © 2024 International Communication Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Conflict Studies

- Development

- Environment

- Foreign Policy

- Human Rights

- International Law

- Organization

- International Relations Theory

- Political Communication

- Political Economy

- Political Geography

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Sexuality and Gender

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Security Studies

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

A history of international communication studies.

- Elizabeth C. Hanson Elizabeth C. Hanson Department of Political Science, University of Connecticut

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.63

- Published in print: 01 March 2010

- Published online: 22 December 2017

- This version: 28 February 2020

- Previous version