What Is A Research (Scientific) Hypothesis? A plain-language explainer + examples

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

If you’re new to the world of research, or it’s your first time writing a dissertation or thesis, you’re probably noticing that the words “research hypothesis” and “scientific hypothesis” are used quite a bit, and you’re wondering what they mean in a research context .

“Hypothesis” is one of those words that people use loosely, thinking they understand what it means. However, it has a very specific meaning within academic research. So, it’s important to understand the exact meaning before you start hypothesizing.

Research Hypothesis 101

- What is a hypothesis ?

- What is a research hypothesis (scientific hypothesis)?

- Requirements for a research hypothesis

- Definition of a research hypothesis

- The null hypothesis

What is a hypothesis?

Let’s start with the general definition of a hypothesis (not a research hypothesis or scientific hypothesis), according to the Cambridge Dictionary:

Hypothesis: an idea or explanation for something that is based on known facts but has not yet been proved.

In other words, it’s a statement that provides an explanation for why or how something works, based on facts (or some reasonable assumptions), but that has not yet been specifically tested . For example, a hypothesis might look something like this:

Hypothesis: sleep impacts academic performance.

This statement predicts that academic performance will be influenced by the amount and/or quality of sleep a student engages in – sounds reasonable, right? It’s based on reasonable assumptions , underpinned by what we currently know about sleep and health (from the existing literature). So, loosely speaking, we could call it a hypothesis, at least by the dictionary definition.

But that’s not good enough…

Unfortunately, that’s not quite sophisticated enough to describe a research hypothesis (also sometimes called a scientific hypothesis), and it wouldn’t be acceptable in a dissertation, thesis or research paper . In the world of academic research, a statement needs a few more criteria to constitute a true research hypothesis .

What is a research hypothesis?

A research hypothesis (also called a scientific hypothesis) is a statement about the expected outcome of a study (for example, a dissertation or thesis). To constitute a quality hypothesis, the statement needs to have three attributes – specificity , clarity and testability .

Let’s take a look at these more closely.

Need a helping hand?

Hypothesis Essential #1: Specificity & Clarity

A good research hypothesis needs to be extremely clear and articulate about both what’ s being assessed (who or what variables are involved ) and the expected outcome (for example, a difference between groups, a relationship between variables, etc.).

Let’s stick with our sleepy students example and look at how this statement could be more specific and clear.

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

As you can see, the statement is very specific as it identifies the variables involved (sleep hours and test grades), the parties involved (two groups of students), as well as the predicted relationship type (a positive relationship). There’s no ambiguity or uncertainty about who or what is involved in the statement, and the expected outcome is clear.

Contrast that to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – and you can see the difference. “Sleep” and “academic performance” are both comparatively vague , and there’s no indication of what the expected relationship direction is (more sleep or less sleep). As you can see, specificity and clarity are key.

Hypothesis Essential #2: Testability (Provability)

A statement must be testable to qualify as a research hypothesis. In other words, there needs to be a way to prove (or disprove) the statement. If it’s not testable, it’s not a hypothesis – simple as that.

For example, consider the hypothesis we mentioned earlier:

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

We could test this statement by undertaking a quantitative study involving two groups of students, one that gets 8 or more hours of sleep per night for a fixed period, and one that gets less. We could then compare the standardised test results for both groups to see if there’s a statistically significant difference.

Again, if you compare this to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – you can see that it would be quite difficult to test that statement, primarily because it isn’t specific enough. How much sleep? By who? What type of academic performance?

So, remember the mantra – if you can’t test it, it’s not a hypothesis 🙂

Defining A Research Hypothesis

You’re still with us? Great! Let’s recap and pin down a clear definition of a hypothesis.

A research hypothesis (or scientific hypothesis) is a statement about an expected relationship between variables, or explanation of an occurrence, that is clear, specific and testable.

So, when you write up hypotheses for your dissertation or thesis, make sure that they meet all these criteria. If you do, you’ll not only have rock-solid hypotheses but you’ll also ensure a clear focus for your entire research project.

What about the null hypothesis?

You may have also heard the terms null hypothesis , alternative hypothesis, or H-zero thrown around. At a simple level, the null hypothesis is the counter-proposal to the original hypothesis.

For example, if the hypothesis predicts that there is a relationship between two variables (for example, sleep and academic performance), the null hypothesis would predict that there is no relationship between those variables.

At a more technical level, the null hypothesis proposes that no statistical significance exists in a set of given observations and that any differences are due to chance alone.

And there you have it – hypotheses in a nutshell.

If you have any questions, be sure to leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help you. If you need hands-on help developing and testing your hypotheses, consider our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the research journey.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

16 Comments

Very useful information. I benefit more from getting more information in this regard.

Very great insight,educative and informative. Please give meet deep critics on many research data of public international Law like human rights, environment, natural resources, law of the sea etc

In a book I read a distinction is made between null, research, and alternative hypothesis. As far as I understand, alternative and research hypotheses are the same. Can you please elaborate? Best Afshin

This is a self explanatory, easy going site. I will recommend this to my friends and colleagues.

Very good definition. How can I cite your definition in my thesis? Thank you. Is nul hypothesis compulsory in a research?

It’s a counter-proposal to be proven as a rejection

Please what is the difference between alternate hypothesis and research hypothesis?

It is a very good explanation. However, it limits hypotheses to statistically tasteable ideas. What about for qualitative researches or other researches that involve quantitative data that don’t need statistical tests?

In qualitative research, one typically uses propositions, not hypotheses.

could you please elaborate it more

I’ve benefited greatly from these notes, thank you.

This is very helpful

well articulated ideas are presented here, thank you for being reliable sources of information

Excellent. Thanks for being clear and sound about the research methodology and hypothesis (quantitative research)

I have only a simple question regarding the null hypothesis. – Is the null hypothesis (Ho) known as the reversible hypothesis of the alternative hypothesis (H1? – How to test it in academic research?

this is very important note help me much more

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is Research Methodology? Simple Definition (With Examples) - Grad Coach - […] Contrasted to this, a quantitative methodology is typically used when the research aims and objectives are confirmatory in nature. For example,…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Privacy Policy

Home » What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Definition:

Hypothesis is an educated guess or proposed explanation for a phenomenon, based on some initial observations or data. It is a tentative statement that can be tested and potentially proven or disproven through further investigation and experimentation.

Hypothesis is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments and the collection and analysis of data. It is an essential element of the scientific method, as it allows researchers to make predictions about the outcome of their experiments and to test those predictions to determine their accuracy.

Types of Hypothesis

Types of Hypothesis are as follows:

Research Hypothesis

A research hypothesis is a statement that predicts a relationship between variables. It is usually formulated as a specific statement that can be tested through research, and it is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is no significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as a starting point for testing the research hypothesis, and if the results of the study reject the null hypothesis, it suggests that there is a significant difference or relationship between variables.

Alternative Hypothesis

An alternative hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is a significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as an alternative to the null hypothesis and is tested against the null hypothesis to determine which statement is more accurate.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the direction of the relationship between variables. For example, a researcher might predict that increasing the amount of exercise will result in a decrease in body weight.

Non-directional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the relationship between variables but does not specify the direction. For example, a researcher might predict that there is a relationship between the amount of exercise and body weight, but they do not specify whether increasing or decreasing exercise will affect body weight.

Statistical Hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis is a statement that assumes a particular statistical model or distribution for the data. It is often used in statistical analysis to test the significance of a particular result.

Composite Hypothesis

A composite hypothesis is a statement that assumes more than one condition or outcome. It can be divided into several sub-hypotheses, each of which represents a different possible outcome.

Empirical Hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is a statement that is based on observed phenomena or data. It is often used in scientific research to develop theories or models that explain the observed phenomena.

Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement that assumes only one outcome or condition. It is often used in scientific research to test a single variable or factor.

Complex Hypothesis

A complex hypothesis is a statement that assumes multiple outcomes or conditions. It is often used in scientific research to test the effects of multiple variables or factors on a particular outcome.

Applications of Hypothesis

Hypotheses are used in various fields to guide research and make predictions about the outcomes of experiments or observations. Here are some examples of how hypotheses are applied in different fields:

- Science : In scientific research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain natural phenomena. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular variable on a natural system, such as the effects of climate change on an ecosystem.

- Medicine : In medical research, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of treatments and therapies for specific conditions. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new drug on a particular disease.

- Psychology : In psychology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of human behavior and cognition. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular stimulus on the brain or behavior.

- Sociology : In sociology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of social phenomena, such as the effects of social structures or institutions on human behavior. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of income inequality on crime rates.

- Business : In business research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain business phenomena, such as consumer behavior or market trends. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new marketing campaign on consumer buying behavior.

- Engineering : In engineering, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of new technologies or designs. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the efficiency of a new solar panel design.

How to write a Hypothesis

Here are the steps to follow when writing a hypothesis:

Identify the Research Question

The first step is to identify the research question that you want to answer through your study. This question should be clear, specific, and focused. It should be something that can be investigated empirically and that has some relevance or significance in the field.

Conduct a Literature Review

Before writing your hypothesis, it’s essential to conduct a thorough literature review to understand what is already known about the topic. This will help you to identify the research gap and formulate a hypothesis that builds on existing knowledge.

Determine the Variables

The next step is to identify the variables involved in the research question. A variable is any characteristic or factor that can vary or change. There are two types of variables: independent and dependent. The independent variable is the one that is manipulated or changed by the researcher, while the dependent variable is the one that is measured or observed as a result of the independent variable.

Formulate the Hypothesis

Based on the research question and the variables involved, you can now formulate your hypothesis. A hypothesis should be a clear and concise statement that predicts the relationship between the variables. It should be testable through empirical research and based on existing theory or evidence.

Write the Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is the opposite of the alternative hypothesis, which is the hypothesis that you are testing. The null hypothesis states that there is no significant difference or relationship between the variables. It is important to write the null hypothesis because it allows you to compare your results with what would be expected by chance.

Refine the Hypothesis

After formulating the hypothesis, it’s important to refine it and make it more precise. This may involve clarifying the variables, specifying the direction of the relationship, or making the hypothesis more testable.

Examples of Hypothesis

Here are a few examples of hypotheses in different fields:

- Psychology : “Increased exposure to violent video games leads to increased aggressive behavior in adolescents.”

- Biology : “Higher levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere will lead to increased plant growth.”

- Sociology : “Individuals who grow up in households with higher socioeconomic status will have higher levels of education and income as adults.”

- Education : “Implementing a new teaching method will result in higher student achievement scores.”

- Marketing : “Customers who receive a personalized email will be more likely to make a purchase than those who receive a generic email.”

- Physics : “An increase in temperature will cause an increase in the volume of a gas, assuming all other variables remain constant.”

- Medicine : “Consuming a diet high in saturated fats will increase the risk of developing heart disease.”

Purpose of Hypothesis

The purpose of a hypothesis is to provide a testable explanation for an observed phenomenon or a prediction of a future outcome based on existing knowledge or theories. A hypothesis is an essential part of the scientific method and helps to guide the research process by providing a clear focus for investigation. It enables scientists to design experiments or studies to gather evidence and data that can support or refute the proposed explanation or prediction.

The formulation of a hypothesis is based on existing knowledge, observations, and theories, and it should be specific, testable, and falsifiable. A specific hypothesis helps to define the research question, which is important in the research process as it guides the selection of an appropriate research design and methodology. Testability of the hypothesis means that it can be proven or disproven through empirical data collection and analysis. Falsifiability means that the hypothesis should be formulated in such a way that it can be proven wrong if it is incorrect.

In addition to guiding the research process, the testing of hypotheses can lead to new discoveries and advancements in scientific knowledge. When a hypothesis is supported by the data, it can be used to develop new theories or models to explain the observed phenomenon. When a hypothesis is not supported by the data, it can help to refine existing theories or prompt the development of new hypotheses to explain the phenomenon.

When to use Hypothesis

Here are some common situations in which hypotheses are used:

- In scientific research , hypotheses are used to guide the design of experiments and to help researchers make predictions about the outcomes of those experiments.

- In social science research , hypotheses are used to test theories about human behavior, social relationships, and other phenomena.

- I n business , hypotheses can be used to guide decisions about marketing, product development, and other areas. For example, a hypothesis might be that a new product will sell well in a particular market, and this hypothesis can be tested through market research.

Characteristics of Hypothesis

Here are some common characteristics of a hypothesis:

- Testable : A hypothesis must be able to be tested through observation or experimentation. This means that it must be possible to collect data that will either support or refute the hypothesis.

- Falsifiable : A hypothesis must be able to be proven false if it is not supported by the data. If a hypothesis cannot be falsified, then it is not a scientific hypothesis.

- Clear and concise : A hypothesis should be stated in a clear and concise manner so that it can be easily understood and tested.

- Based on existing knowledge : A hypothesis should be based on existing knowledge and research in the field. It should not be based on personal beliefs or opinions.

- Specific : A hypothesis should be specific in terms of the variables being tested and the predicted outcome. This will help to ensure that the research is focused and well-designed.

- Tentative: A hypothesis is a tentative statement or assumption that requires further testing and evidence to be confirmed or refuted. It is not a final conclusion or assertion.

- Relevant : A hypothesis should be relevant to the research question or problem being studied. It should address a gap in knowledge or provide a new perspective on the issue.

Advantages of Hypothesis

Hypotheses have several advantages in scientific research and experimentation:

- Guides research: A hypothesis provides a clear and specific direction for research. It helps to focus the research question, select appropriate methods and variables, and interpret the results.

- Predictive powe r: A hypothesis makes predictions about the outcome of research, which can be tested through experimentation. This allows researchers to evaluate the validity of the hypothesis and make new discoveries.

- Facilitates communication: A hypothesis provides a common language and framework for scientists to communicate with one another about their research. This helps to facilitate the exchange of ideas and promotes collaboration.

- Efficient use of resources: A hypothesis helps researchers to use their time, resources, and funding efficiently by directing them towards specific research questions and methods that are most likely to yield results.

- Provides a basis for further research: A hypothesis that is supported by data provides a basis for further research and exploration. It can lead to new hypotheses, theories, and discoveries.

- Increases objectivity: A hypothesis can help to increase objectivity in research by providing a clear and specific framework for testing and interpreting results. This can reduce bias and increase the reliability of research findings.

Limitations of Hypothesis

Some Limitations of the Hypothesis are as follows:

- Limited to observable phenomena: Hypotheses are limited to observable phenomena and cannot account for unobservable or intangible factors. This means that some research questions may not be amenable to hypothesis testing.

- May be inaccurate or incomplete: Hypotheses are based on existing knowledge and research, which may be incomplete or inaccurate. This can lead to flawed hypotheses and erroneous conclusions.

- May be biased: Hypotheses may be biased by the researcher’s own beliefs, values, or assumptions. This can lead to selective interpretation of data and a lack of objectivity in research.

- Cannot prove causation: A hypothesis can only show a correlation between variables, but it cannot prove causation. This requires further experimentation and analysis.

- Limited to specific contexts: Hypotheses are limited to specific contexts and may not be generalizable to other situations or populations. This means that results may not be applicable in other contexts or may require further testing.

- May be affected by chance : Hypotheses may be affected by chance or random variation, which can obscure or distort the true relationship between variables.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Background of The Study – Examples and Writing...

Informed Consent in Research – Types, Templates...

Purpose of Research – Objectives and Applications

Appendices – Writing Guide, Types and Examples

Implications in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and...

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Research Hypothesis: What It Is, Types + How to Develop?

A research study starts with a question. Researchers worldwide ask questions and create research hypotheses. The effectiveness of research relies on developing a good research hypothesis. Examples of research hypotheses can guide researchers in writing effective ones.

In this blog, we’ll learn what a research hypothesis is, why it’s important in research, and the different types used in science. We’ll also guide you through creating your research hypothesis and discussing ways to test and evaluate it.

What is a Research Hypothesis?

A hypothesis is like a guess or idea that you suggest to check if it’s true. A research hypothesis is a statement that brings up a question and predicts what might happen.

It’s really important in the scientific method and is used in experiments to figure things out. Essentially, it’s an educated guess about how things are connected in the research.

A research hypothesis usually includes pointing out the independent variable (the thing they’re changing or studying) and the dependent variable (the result they’re measuring or watching). It helps plan how to gather and analyze data to see if there’s evidence to support or deny the expected connection between these variables.

Importance of Hypothesis in Research

Hypotheses are really important in research. They help design studies, allow for practical testing, and add to our scientific knowledge. Their main role is to organize research projects, making them purposeful, focused, and valuable to the scientific community. Let’s look at some key reasons why they matter:

- A research hypothesis helps test theories.

A hypothesis plays a pivotal role in the scientific method by providing a basis for testing existing theories. For example, a hypothesis might test the predictive power of a psychological theory on human behavior.

- It serves as a great platform for investigation activities.

It serves as a launching pad for investigation activities, which offers researchers a clear starting point. A research hypothesis can explore the relationship between exercise and stress reduction.

- Hypothesis guides the research work or study.

A well-formulated hypothesis guides the entire research process. It ensures that the study remains focused and purposeful. For instance, a hypothesis about the impact of social media on interpersonal relationships provides clear guidance for a study.

- Hypothesis sometimes suggests theories.

In some cases, a hypothesis can suggest new theories or modifications to existing ones. For example, a hypothesis testing the effectiveness of a new drug might prompt a reconsideration of current medical theories.

- It helps in knowing the data needs.

A hypothesis clarifies the data requirements for a study, ensuring that researchers collect the necessary information—a hypothesis guiding the collection of demographic data to analyze the influence of age on a particular phenomenon.

- The hypothesis explains social phenomena.

Hypotheses are instrumental in explaining complex social phenomena. For instance, a hypothesis might explore the relationship between economic factors and crime rates in a given community.

- Hypothesis provides a relationship between phenomena for empirical Testing.

Hypotheses establish clear relationships between phenomena, paving the way for empirical testing. An example could be a hypothesis exploring the correlation between sleep patterns and academic performance.

- It helps in knowing the most suitable analysis technique.

A hypothesis guides researchers in selecting the most appropriate analysis techniques for their data. For example, a hypothesis focusing on the effectiveness of a teaching method may lead to the choice of statistical analyses best suited for educational research.

Characteristics of a Good Research Hypothesis

A hypothesis is a specific idea that you can test in a study. It often comes from looking at past research and theories. A good hypothesis usually starts with a research question that you can explore through background research. For it to be effective, consider these key characteristics:

- Clear and Focused Language: A good hypothesis uses clear and focused language to avoid confusion and ensure everyone understands it.

- Related to the Research Topic: The hypothesis should directly relate to the research topic, acting as a bridge between the specific question and the broader study.

- Testable: An effective hypothesis can be tested, meaning its prediction can be checked with real data to support or challenge the proposed relationship.

- Potential for Exploration: A good hypothesis often comes from a research question that invites further exploration. Doing background research helps find gaps and potential areas to investigate.

- Includes Variables: The hypothesis should clearly state both the independent and dependent variables, specifying the factors being studied and the expected outcomes.

- Ethical Considerations: Check if variables can be manipulated without breaking ethical standards. It’s crucial to maintain ethical research practices.

- Predicts Outcomes: The hypothesis should predict the expected relationship and outcome, acting as a roadmap for the study and guiding data collection and analysis.

- Simple and Concise: A good hypothesis avoids unnecessary complexity and is simple and concise, expressing the essence of the proposed relationship clearly.

- Clear and Assumption-Free: The hypothesis should be clear and free from assumptions about the reader’s prior knowledge, ensuring universal understanding.

- Observable and Testable Results: A strong hypothesis implies research that produces observable and testable results, making sure the study’s outcomes can be effectively measured and analyzed.

When you use these characteristics as a checklist, it can help you create a good research hypothesis. It’ll guide improving and strengthening the hypothesis, identifying any weaknesses, and making necessary changes. Crafting a hypothesis with these features helps you conduct a thorough and insightful research study.

Types of Research Hypotheses

The research hypothesis comes in various types, each serving a specific purpose in guiding the scientific investigation. Knowing the differences will make it easier for you to create your own hypothesis. Here’s an overview of the common types:

01. Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis states that there is no connection between two considered variables or that two groups are unrelated. As discussed earlier, a hypothesis is an unproven assumption lacking sufficient supporting data. It serves as the statement researchers aim to disprove. It is testable, verifiable, and can be rejected.

For example, if you’re studying the relationship between Project A and Project B, assuming both projects are of equal standard is your null hypothesis. It needs to be specific for your study.

02. Alternative Hypothesis

The alternative hypothesis is basically another option to the null hypothesis. It involves looking for a significant change or alternative that could lead you to reject the null hypothesis. It’s a different idea compared to the null hypothesis.

When you create a null hypothesis, you’re making an educated guess about whether something is true or if there’s a connection between that thing and another variable. If the null view suggests something is correct, the alternative hypothesis says it’s incorrect.

For instance, if your null hypothesis is “I’m going to be $1000 richer,” the alternative hypothesis would be “I’m not going to get $1000 or be richer.”

03. Directional Hypothesis

The directional hypothesis predicts the direction of the relationship between independent and dependent variables. They specify whether the effect will be positive or negative.

If you increase your study hours, you will experience a positive association with your exam scores. This hypothesis suggests that as you increase the independent variable (study hours), there will also be an increase in the dependent variable (exam scores).

04. Non-directional Hypothesis

The non-directional hypothesis predicts the existence of a relationship between variables but does not specify the direction of the effect. It suggests that there will be a significant difference or relationship, but it does not predict the nature of that difference.

For example, you will find no notable difference in test scores between students who receive the educational intervention and those who do not. However, once you compare the test scores of the two groups, you will notice an important difference.

05. Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis predicts a relationship between one dependent variable and one independent variable without specifying the nature of that relationship. It’s simple and usually used when we don’t know much about how the two things are connected.

For example, if you adopt effective study habits, you will achieve higher exam scores than those with poor study habits.

06. Complex Hypothesis

A complex hypothesis is an idea that specifies a relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. It is a more detailed idea than a simple hypothesis.

While a simple view suggests a straightforward cause-and-effect relationship between two things, a complex hypothesis involves many factors and how they’re connected to each other.

For example, when you increase your study time, you tend to achieve higher exam scores. The connection between your study time and exam performance is affected by various factors, including the quality of your sleep, your motivation levels, and the effectiveness of your study techniques.

If you sleep well, stay highly motivated, and use effective study strategies, you may observe a more robust positive correlation between the time you spend studying and your exam scores, unlike those who may lack these factors.

07. Associative Hypothesis

An associative hypothesis proposes a connection between two things without saying that one causes the other. Basically, it suggests that when one thing changes, the other changes too, but it doesn’t claim that one thing is causing the change in the other.

For example, you will likely notice higher exam scores when you increase your study time. You can recognize an association between your study time and exam scores in this scenario.

Your hypothesis acknowledges a relationship between the two variables—your study time and exam scores—without asserting that increased study time directly causes higher exam scores. You need to consider that other factors, like motivation or learning style, could affect the observed association.

08. Causal Hypothesis

A causal hypothesis proposes a cause-and-effect relationship between two variables. It suggests that changes in one variable directly cause changes in another variable.

For example, when you increase your study time, you experience higher exam scores. This hypothesis suggests a direct cause-and-effect relationship, indicating that the more time you spend studying, the higher your exam scores. It assumes that changes in your study time directly influence changes in your exam performance.

09. Empirical Hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is a statement based on things we can see and measure. It comes from direct observation or experiments and can be tested with real-world evidence. If an experiment proves a theory, it supports the idea and shows it’s not just a guess. This makes the statement more reliable than a wild guess.

For example, if you increase the dosage of a certain medication, you might observe a quicker recovery time for patients. Imagine you’re in charge of a clinical trial. In this trial, patients are given varying dosages of the medication, and you measure and compare their recovery times. This allows you to directly see the effects of different dosages on how fast patients recover.

This way, you can create a research hypothesis: “Increasing the dosage of a certain medication will lead to a faster recovery time for patients.”

10. Statistical Hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis is a statement or assumption about a population parameter that is the subject of an investigation. It serves as the basis for statistical analysis and testing. It is often tested using statistical methods to draw inferences about the larger population.

In a hypothesis test, statistical evidence is collected to either reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis or fail to reject the null hypothesis due to insufficient evidence.

For example, let’s say you’re testing a new medicine. Your hypothesis could be that the medicine doesn’t really help patients get better. So, you collect data and use statistics to see if your guess is right or if the medicine actually makes a difference.

If the data strongly shows that the medicine does help, you say your guess was wrong, and the medicine does make a difference. But if the proof isn’t strong enough, you can stick with your original guess because you didn’t get enough evidence to change your mind.

How to Develop a Research Hypotheses?

Step 1: identify your research problem or topic..

Define the area of interest or the problem you want to investigate. Make sure it’s clear and well-defined.

Start by asking a question about your chosen topic. Consider the limitations of your research and create a straightforward problem related to your topic. Once you’ve done that, you can develop and test a hypothesis with evidence.

Step 2: Conduct a literature review

Review existing literature related to your research problem. This will help you understand the current state of knowledge in the field, identify gaps, and build a foundation for your hypothesis. Consider the following questions:

- What existing research has been conducted on your chosen topic?

- Are there any gaps or unanswered questions in the current literature?

- How will the existing literature contribute to the foundation of your research?

Step 3: Formulate your research question

Based on your literature review, create a specific and concise research question that addresses your identified problem. Your research question should be clear, focused, and relevant to your field of study.

Step 4: Identify variables

Determine the key variables involved in your research question. Variables are the factors or phenomena that you will study and manipulate to test your hypothesis.

- Independent Variable: The variable you manipulate or control.

- Dependent Variable: The variable you measure to observe the effect of the independent variable.

Step 5: State the Null hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a statement that there is no significant difference or effect. It serves as a baseline for comparison with the alternative hypothesis.

Step 6: Select appropriate methods for testing the hypothesis

Choose research methods that align with your study objectives, such as experiments, surveys, or observational studies. The selected methods enable you to test your research hypothesis effectively.

Creating a research hypothesis usually takes more than one try. Expect to make changes as you collect data. It’s normal to test and say no to a few hypotheses before you find the right answer to your research question.

Testing and Evaluating Hypotheses

Testing hypotheses is a really important part of research. It’s like the practical side of things. Here, real-world evidence will help you determine how different things are connected. Let’s explore the main steps in hypothesis testing:

- State your research hypothesis.

Before testing, clearly articulate your research hypothesis. This involves framing both a null hypothesis, suggesting no significant effect or relationship, and an alternative hypothesis, proposing the expected outcome.

- Collect data strategically.

Plan how you will gather information in a way that fits your study. Make sure your data collection method matches the things you’re studying.

Whether through surveys, observations, or experiments, this step demands precision and adherence to the established methodology. The quality of data collected directly influences the credibility of study outcomes.

- Perform an appropriate statistical test.

Choose a statistical test that aligns with the nature of your data and the hypotheses being tested. Whether it’s a t-test, chi-square test, ANOVA, or regression analysis, selecting the right statistical tool is paramount for accurate and reliable results.

- Decide if your idea was right or wrong.

Following the statistical analysis, evaluate the results in the context of your null hypothesis. You need to decide if you should reject your null hypothesis or not.

- Share what you found.

When discussing what you found in your research, be clear and organized. Say whether your idea was supported or not, and talk about what your results mean. Also, mention any limits to your study and suggest ideas for future research.

The Role of QuestionPro to Develop a Good Research Hypothesis

QuestionPro is a survey and research platform that provides tools for creating, distributing, and analyzing surveys. It plays a crucial role in the research process, especially when you’re in the initial stages of hypothesis development. Here’s how QuestionPro can help you to develop a good research hypothesis:

- Survey design and data collection: You can use the platform to create targeted questions that help you gather relevant data.

- Exploratory research: Through surveys and feedback mechanisms on QuestionPro, you can conduct exploratory research to understand the landscape of a particular subject.

- Literature review and background research: QuestionPro surveys can collect sample population opinions, experiences, and preferences. This data and a thorough literature evaluation can help you generate a well-grounded hypothesis by improving your research knowledge.

- Identifying variables: Using targeted survey questions, you can identify relevant variables related to their research topic.

- Testing assumptions: You can use surveys to informally test certain assumptions or hypotheses before formalizing a research hypothesis.

- Data analysis tools: QuestionPro provides tools for analyzing survey data. You can use these tools to identify the collected data’s patterns, correlations, or trends.

- Refining your hypotheses: As you collect data through QuestionPro, you can adjust your hypotheses based on the real-world responses you receive.

A research hypothesis is like a guide for researchers in science. It’s a well-thought-out idea that has been thoroughly tested. This idea is crucial as researchers can explore different fields, such as medicine, social sciences, and natural sciences. The research hypothesis links theories to real-world evidence and gives researchers a clear path to explore and make discoveries.

QuestionPro Research Suite is a helpful tool for researchers. It makes creating surveys, collecting data, and analyzing information easily. It supports all kinds of research, from exploring new ideas to forming hypotheses. With a focus on using data, it helps researchers do their best work.

Are you interested in learning more about QuestionPro Research Suite? Take advantage of QuestionPro’s free trial to get an initial look at its capabilities and realize the full potential of your research efforts.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

How Can I Help You? — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Jun 5, 2024

Why Multilingual 360 Feedback Surveys Provide Better Insights

Jun 3, 2024

Raked Weighting: A Key Tool for Accurate Survey Results

May 31, 2024

Top 8 Data Trends to Understand the Future of Data

May 30, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

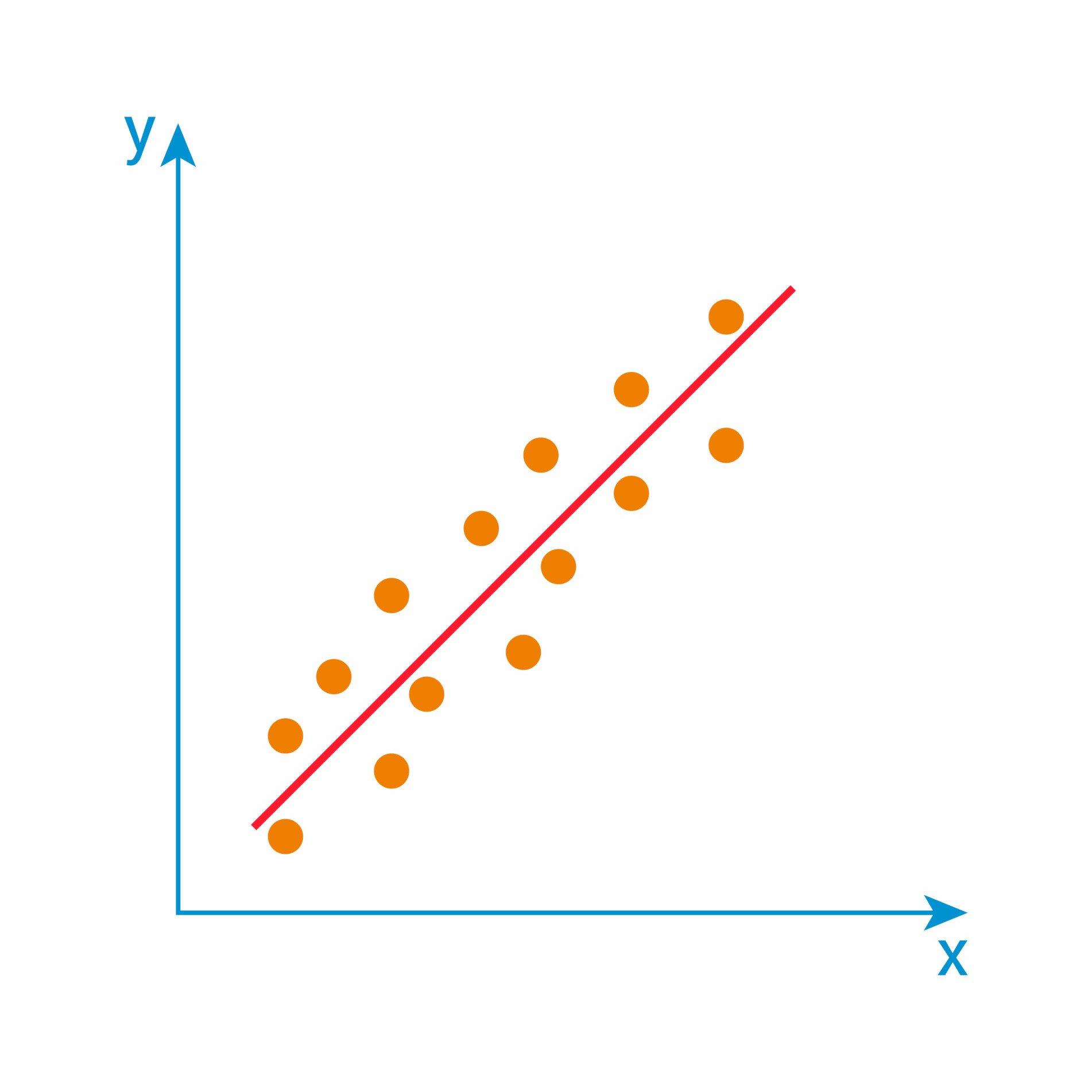

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

How to Write a Research Hypothesis

- Research Process

- Peer Review

Since grade school, we've all been familiar with hypotheses. The hypothesis is an essential step of the scientific method. But what makes an effective research hypothesis, how do you create one, and what types of hypotheses are there? We answer these questions and more.

Updated on April 27, 2022

What is a research hypothesis?

General hypothesis.

Since grade school, we've all been familiar with the term “hypothesis.” A hypothesis is a fact-based guess or prediction that has not been proven. It is an essential step of the scientific method. The hypothesis of a study is a drive for experimentation to either prove the hypothesis or dispute it.

Research Hypothesis

A research hypothesis is more specific than a general hypothesis. It is an educated, expected prediction of the outcome of a study that is testable.

What makes an effective research hypothesis?

A good research hypothesis is a clear statement of the relationship between a dependent variable(s) and independent variable(s) relevant to the study that can be disproven.

Research hypothesis checklist

Once you've written a possible hypothesis, make sure it checks the following boxes:

- It must be testable: You need a means to prove your hypothesis. If you can't test it, it's not a hypothesis.

- It must include a dependent and independent variable: At least one independent variable ( cause ) and one dependent variable ( effect ) must be included.

- The language must be easy to understand: Be as clear and concise as possible. Nothing should be left to interpretation.

- It must be relevant to your research topic: You probably shouldn't be talking about cats and dogs if your research topic is outer space. Stay relevant to your topic.

How to create an effective research hypothesis

Pose it as a question first.

Start your research hypothesis from a journalistic approach. Ask one of the five W's: Who, what, when, where, or why.

A possible initial question could be: Why is the sky blue?

Do the preliminary research

Once you have a question in mind, read research around your topic. Collect research from academic journals.

If you're looking for information about the sky and why it is blue, research information about the atmosphere, weather, space, the sun, etc.

Write a draft hypothesis

Once you're comfortable with your subject and have preliminary knowledge, create a working hypothesis. Don't stress much over this. Your first hypothesis is not permanent. Look at it as a draft.

Your first draft of a hypothesis could be: Certain molecules in the Earth's atmosphere are responsive to the sky being the color blue.

Make your working draft perfect

Take your working hypothesis and make it perfect. Narrow it down to include only the information listed in the “Research hypothesis checklist” above.

Now that you've written your working hypothesis, narrow it down. Your new hypothesis could be: Light from the sun hitting oxygen molecules in the sky makes the color of the sky appear blue.

Write a null hypothesis

Your null hypothesis should be the opposite of your research hypothesis. It should be able to be disproven by your research.

In this example, your null hypothesis would be: Light from the sun hitting oxygen molecules in the sky does not make the color of the sky appear blue.

Why is it important to have a clear, testable hypothesis?

One of the main reasons a manuscript can be rejected from a journal is because of a weak hypothesis. “Poor hypothesis, study design, methodology, and improper use of statistics are other reasons for rejection of a manuscript,” says Dr. Ish Kumar Dhammi and Dr. Rehan-Ul-Haq in Indian Journal of Orthopaedics.

According to Dr. James M. Provenzale in American Journal of Roentgenology , “The clear declaration of a research question (or hypothesis) in the Introduction is critical for reviewers to understand the intent of the research study. It is best to clearly state the study goal in plain language (for example, “We set out to determine whether condition x produces condition y.”) An insufficient problem statement is one of the more common reasons for manuscript rejection.”

Characteristics that make a hypothesis weak include:

- Unclear variables

- Unoriginality

- Too general

- Too specific

A weak hypothesis leads to weak research and methods . The goal of a paper is to prove or disprove a hypothesis - or to prove or disprove a null hypothesis. If the hypothesis is not a dependent variable of what is being studied, the paper's methods should come into question.

A strong hypothesis is essential to the scientific method. A hypothesis states an assumed relationship between at least two variables and the experiment then proves or disproves that relationship with statistical significance. Without a proven and reproducible relationship, the paper feeds into the reproducibility crisis. Learn more about writing for reproducibility .

In a study published in The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India by Dr. Suvarna Satish Khadilkar, she reviewed 400 rejected manuscripts to see why they were rejected. Her studies revealed that poor methodology was a top reason for the submission having a final disposition of rejection.

Aside from publication chances, Dr. Gareth Dyke believes a clear hypothesis helps efficiency.

“Developing a clear and testable hypothesis for your research project means that you will not waste time, energy, and money with your work,” said Dyke. “Refining a hypothesis that is both meaningful, interesting, attainable, and testable is the goal of all effective research.”

Types of research hypotheses

There can be overlap in these types of hypotheses.

Simple hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a hypothesis at its most basic form. It shows the relationship of one independent and one independent variable.

Example: Drinking soda (independent variable) every day leads to obesity (dependent variable).

Complex hypothesis

A complex hypothesis shows the relationship of two or more independent and dependent variables.

Example: Drinking soda (independent variable) every day leads to obesity (dependent variable) and heart disease (dependent variable).

Directional hypothesis

A directional hypothesis guesses which way the results of an experiment will go. It uses words like increase, decrease, higher, lower, positive, negative, more, or less. It is also frequently used in statistics.

Example: Humans exposed to radiation have a higher risk of cancer than humans not exposed to radiation.

Non-directional hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis says there will be an effect on the dependent variable, but it does not say which direction.

Associative hypothesis

An associative hypothesis says that when one variable changes, so does the other variable.

Alternative hypothesis

An alternative hypothesis states that the variables have a relationship.

- The opposite of a null hypothesis

Example: An apple a day keeps the doctor away.

Null hypothesis

A null hypothesis states that there is no relationship between the two variables. It is posed as the opposite of what the alternative hypothesis states.

Researchers use a null hypothesis to work to be able to reject it. A null hypothesis:

- Can never be proven

- Can only be rejected

- Is the opposite of an alternative hypothesis

Example: An apple a day does not keep the doctor away.

Logical hypothesis

A logical hypothesis is a suggested explanation while using limited evidence.

Example: Bats can navigate in the dark better than tigers.

In this hypothesis, the researcher knows that tigers cannot see in the dark, and bats mostly live in darkness.

Empirical hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is also called a “working hypothesis.” It uses the trial and error method and changes around the independent variables.

- An apple a day keeps the doctor away.

- Two apples a day keep the doctor away.

- Three apples a day keep the doctor away.

In this case, the research changes the hypothesis as the researcher learns more about his/her research.

Statistical hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis is a look of a part of a population or statistical model. This type of hypothesis is especially useful if you are making a statement about a large population. Instead of having to test the entire population of Illinois, you could just use a smaller sample of people who live there.

Example: 70% of people who live in Illinois are iron deficient.

Causal hypothesis

A causal hypothesis states that the independent variable will have an effect on the dependent variable.

Example: Using tobacco products causes cancer.

Final thoughts

Make sure your research is error-free before you send it to your preferred journal . Check our our English Editing services to avoid your chances of desk rejection.

Jonny Rhein, BA

See our "Privacy Policy"

- Manuscript Preparation

What is and How to Write a Good Hypothesis in Research?

- 4 minute read

- 323.5K views

Table of Contents

One of the most important aspects of conducting research is constructing a strong hypothesis. But what makes a hypothesis in research effective? In this article, we’ll look at the difference between a hypothesis and a research question, as well as the elements of a good hypothesis in research. We’ll also include some examples of effective hypotheses, and what pitfalls to avoid.

What is a Hypothesis in Research?

Simply put, a hypothesis is a research question that also includes the predicted or expected result of the research. Without a hypothesis, there can be no basis for a scientific or research experiment. As such, it is critical that you carefully construct your hypothesis by being deliberate and thorough, even before you set pen to paper. Unless your hypothesis is clearly and carefully constructed, any flaw can have an adverse, and even grave, effect on the quality of your experiment and its subsequent results.

Research Question vs Hypothesis

It’s easy to confuse research questions with hypotheses, and vice versa. While they’re both critical to the Scientific Method, they have very specific differences. Primarily, a research question, just like a hypothesis, is focused and concise. But a hypothesis includes a prediction based on the proposed research, and is designed to forecast the relationship of and between two (or more) variables. Research questions are open-ended, and invite debate and discussion, while hypotheses are closed, e.g. “The relationship between A and B will be C.”

A hypothesis is generally used if your research topic is fairly well established, and you are relatively certain about the relationship between the variables that will be presented in your research. Since a hypothesis is ideally suited for experimental studies, it will, by its very existence, affect the design of your experiment. The research question is typically used for new topics that have not yet been researched extensively. Here, the relationship between different variables is less known. There is no prediction made, but there may be variables explored. The research question can be casual in nature, simply trying to understand if a relationship even exists, descriptive or comparative.

How to Write Hypothesis in Research

Writing an effective hypothesis starts before you even begin to type. Like any task, preparation is key, so you start first by conducting research yourself, and reading all you can about the topic that you plan to research. From there, you’ll gain the knowledge you need to understand where your focus within the topic will lie.

Remember that a hypothesis is a prediction of the relationship that exists between two or more variables. Your job is to write a hypothesis, and design the research, to “prove” whether or not your prediction is correct. A common pitfall is to use judgments that are subjective and inappropriate for the construction of a hypothesis. It’s important to keep the focus and language of your hypothesis objective.

An effective hypothesis in research is clearly and concisely written, and any terms or definitions clarified and defined. Specific language must also be used to avoid any generalities or assumptions.

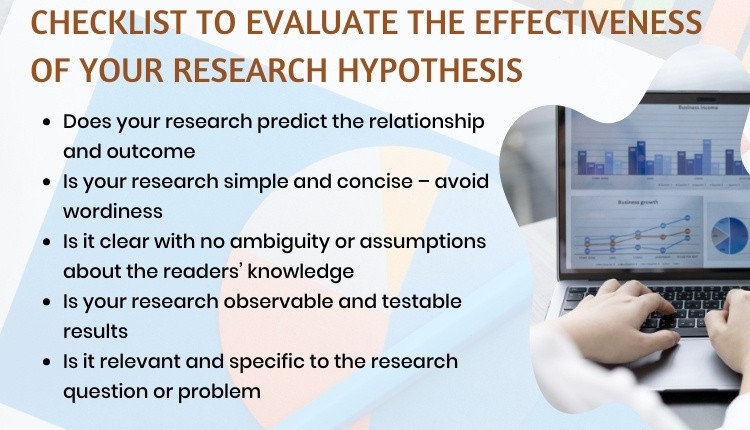

Use the following points as a checklist to evaluate the effectiveness of your research hypothesis:

- Predicts the relationship and outcome

- Simple and concise – avoid wordiness

- Clear with no ambiguity or assumptions about the readers’ knowledge

- Observable and testable results

- Relevant and specific to the research question or problem

Research Hypothesis Example

Perhaps the best way to evaluate whether or not your hypothesis is effective is to compare it to those of your colleagues in the field. There is no need to reinvent the wheel when it comes to writing a powerful research hypothesis. As you’re reading and preparing your hypothesis, you’ll also read other hypotheses. These can help guide you on what works, and what doesn’t, when it comes to writing a strong research hypothesis.

Here are a few generic examples to get you started.

Eating an apple each day, after the age of 60, will result in a reduction of frequency of physician visits.

Budget airlines are more likely to receive more customer complaints. A budget airline is defined as an airline that offers lower fares and fewer amenities than a traditional full-service airline. (Note that the term “budget airline” is included in the hypothesis.

Workplaces that offer flexible working hours report higher levels of employee job satisfaction than workplaces with fixed hours.

Each of the above examples are specific, observable and measurable, and the statement of prediction can be verified or shown to be false by utilizing standard experimental practices. It should be noted, however, that often your hypothesis will change as your research progresses.

Language Editing Plus

Elsevier’s Language Editing Plus service can help ensure that your research hypothesis is well-designed, and articulates your research and conclusions. Our most comprehensive editing package, you can count on a thorough language review by native-English speakers who are PhDs or PhD candidates. We’ll check for effective logic and flow of your manuscript, as well as document formatting for your chosen journal, reference checks, and much more.

- Research Process

Systematic Literature Review or Literature Review?

What is a Problem Statement? [with examples]

You may also like.

Page-Turner Articles are More Than Just Good Arguments: Be Mindful of Tone and Structure!

A Must-see for Researchers! How to Ensure Inclusivity in Your Scientific Writing

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

How to Develop a Good Research Hypothesis

The story of a research study begins by asking a question. Researchers all around the globe are asking curious questions and formulating research hypothesis. However, whether the research study provides an effective conclusion depends on how well one develops a good research hypothesis. Research hypothesis examples could help researchers get an idea as to how to write a good research hypothesis.

This blog will help you understand what is a research hypothesis, its characteristics and, how to formulate a research hypothesis

Table of Contents

What is Hypothesis?

Hypothesis is an assumption or an idea proposed for the sake of argument so that it can be tested. It is a precise, testable statement of what the researchers predict will be outcome of the study. Hypothesis usually involves proposing a relationship between two variables: the independent variable (what the researchers change) and the dependent variable (what the research measures).

What is a Research Hypothesis?

Research hypothesis is a statement that introduces a research question and proposes an expected result. It is an integral part of the scientific method that forms the basis of scientific experiments. Therefore, you need to be careful and thorough when building your research hypothesis. A minor flaw in the construction of your hypothesis could have an adverse effect on your experiment. In research, there is a convention that the hypothesis is written in two forms, the null hypothesis, and the alternative hypothesis (called the experimental hypothesis when the method of investigation is an experiment).

Characteristics of a Good Research Hypothesis

As the hypothesis is specific, there is a testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. You may consider drawing hypothesis from previously published research based on the theory.

A good research hypothesis involves more effort than just a guess. In particular, your hypothesis may begin with a question that could be further explored through background research.

To help you formulate a promising research hypothesis, you should ask yourself the following questions:

- Is the language clear and focused?

- What is the relationship between your hypothesis and your research topic?

- Is your hypothesis testable? If yes, then how?

- What are the possible explanations that you might want to explore?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate your variables without hampering the ethical standards?

- Does your research predict the relationship and outcome?

- Is your research simple and concise (avoids wordiness)?

- Is it clear with no ambiguity or assumptions about the readers’ knowledge

- Is your research observable and testable results?

- Is it relevant and specific to the research question or problem?