- Media Center

Reinforcement Theory

The basic idea, theory, meet practice.

TDL is an applied research consultancy. In our work, we leverage the insights of diverse fields—from psychology and economics to machine learning and behavioral data science—to sculpt targeted solutions to nuanced problems.

Do you remember back in elementary school, when you received stickers and smiley faces on your worksheets? Or maybe you were occasionally chosen for class monitor. It always made you feel a warm glow, like you were doing something right. On the other hand, the feeling of receiving a timeout or missing recess was dreadful.

These various rewards and punishments are all examples of reinforcement theory at work. Though we can remember examples all the way back from elementary school, reinforcement theory still influences our lives every day.

Put simply, reinforcement theory suggests that a behavior can be strengthened when good events follow it, and reduced when undesirable events follow it. It relies on the idea that behavior is influenced by its consequences. For instance, when action A results in a desirable outcome, one is more likely to do action A; when action B results in an unpleasant outcome, one is less likely to do action B. You’re more likely to study for your spelling test after getting your teacher’s praise; you’re less likely to pull your friend’s hair after getting a stern lecture.

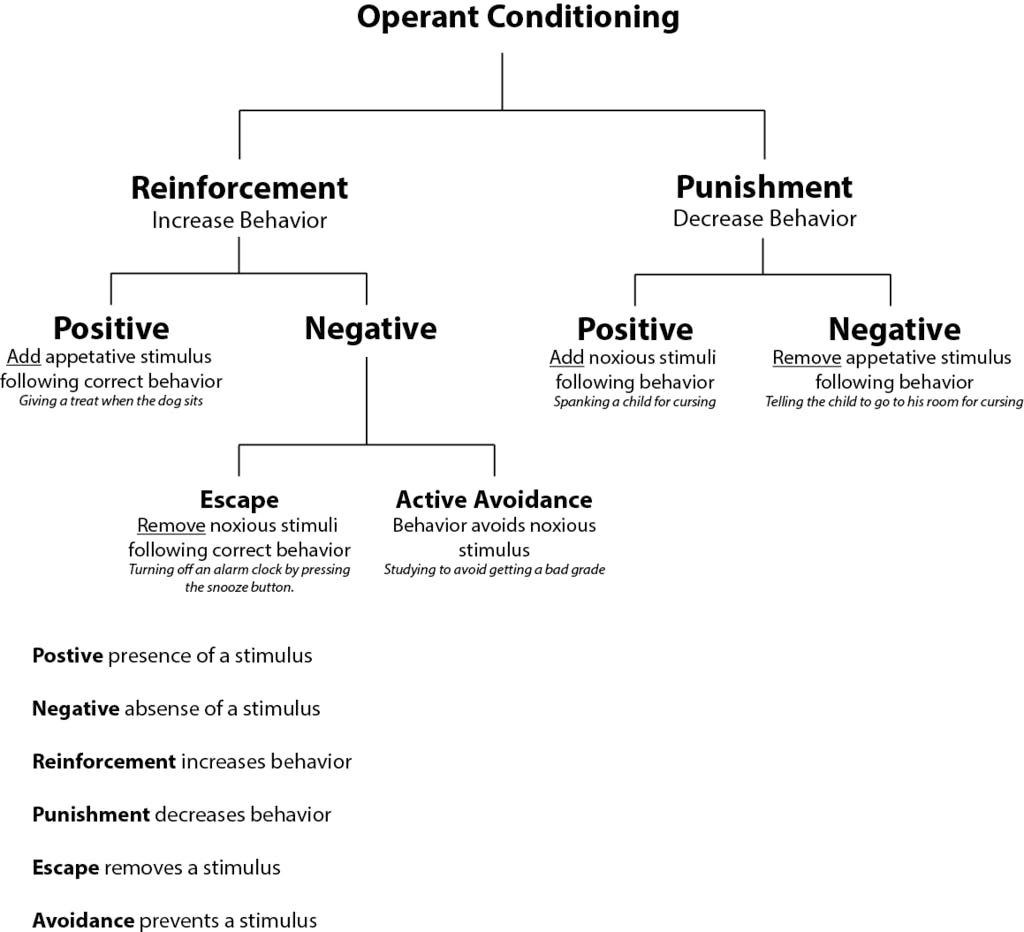

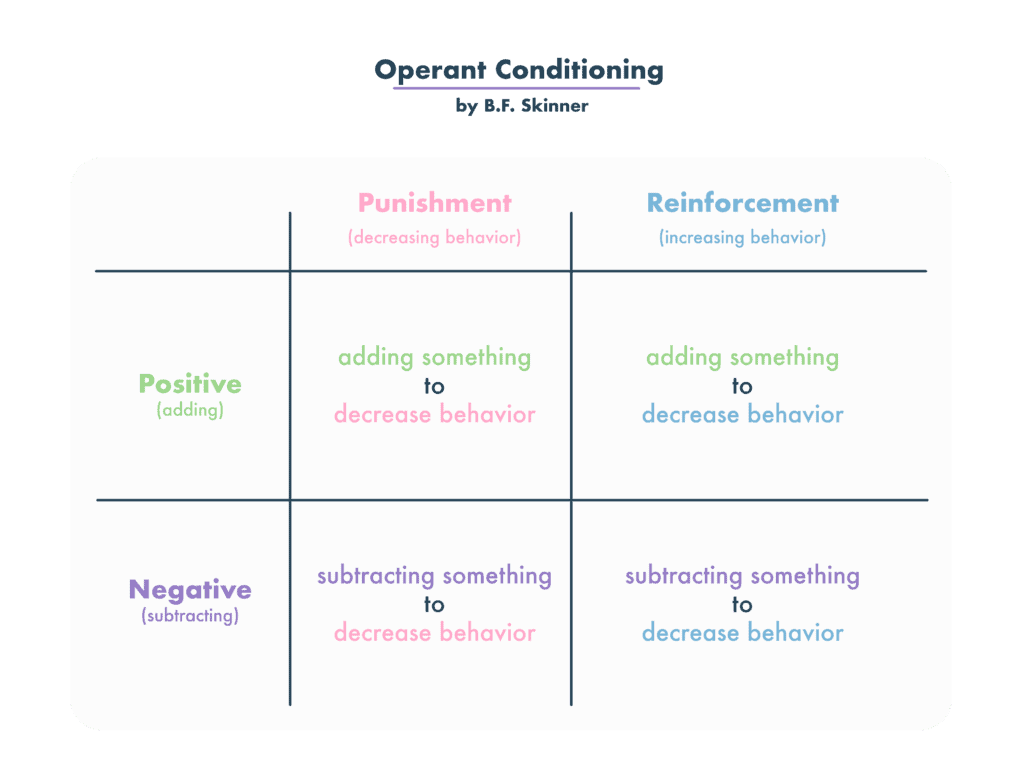

Reinforcement theory is a framework, also known as operant conditioning, detailed in the chart below:

Reinforcement aims to encourage a behavior, whereas punishment aims to reduce a behavior. Both reinforcement and punishment can be positive or negative. A positive stimulus entails adding desirable effects, while negative entails removing undesirable effects of a behavior.

I think, as much as people moan at things like award ceremonies, it gives people role models. It provides real positive reinforcement that you can be who you are and still massively achieve. – Jack Monroe

Behaviorism : The systematic study of external behavior

Operant: Behavior performed by an individual as a response

Reinforcement: Encouragement of a behavior

Punishment: Discouragement of a behavior

Negative: Removing a behavior’s consequences

Positive: Adding consequences to a behavior

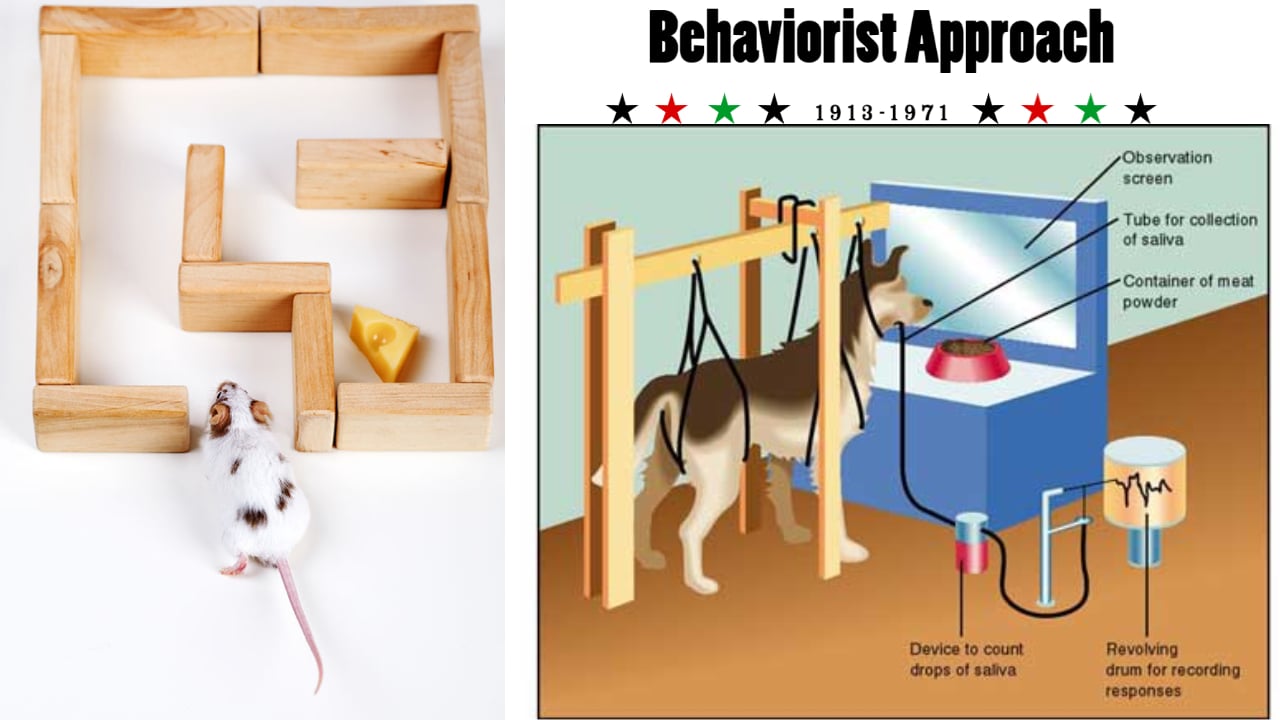

Earlier developments in the field of conditioning focused on simply the association between stimuli and the influence it has on involuntary responses. You likely know Pavlov’s dogs, who started to salivate when they heard the sound of his assistant’s footsteps, long before the food was in front of them. This became known as classical conditioning: a stimulus A and a resulting response, such as food and salivation, becomes associated with a different, neutral stimulus, such as the sound of the assistant approach. B becomes associated with A over time, and as a result, prompts the same response as A. Eventually, the dogs learn that approaching footsteps means food, and salivate over the footsteps.

Classical conditioning was developed during a period of psychology that was primarily concerned about an individual’s internal needs and motivations. Maslow and Herzberg completed related work during this period.

For behaviorists, the psychoanalytical approach was dissatisfying because there were no external, observable phenomena that allowed its techniques to be verified and tested. In the early 1900s, Edward Thorndike concretized the Law of Effect, suggesting that individuals are more likely to perform actions that have satisfying rewards. This marked a significant outward shift in behaviorism; subsequent research began examining the external effects of an action and how they influence choices, as opposed to theorizing how internal responses were influenced by past events. More specifically, Thorndike proposed that if the link between an action and the satisfying effect is strengthened, the action will become more likely in the future.

- F. Skinner further differentiated between the means in which stimulus and action affect behavior, deviating even more from the early studies in classical conditioning. As per Skinner’s framework, Pavlov’s work studied stimuli. In the above example, stimulus B (footsteps) becomes a conditioned stimulus that generates the same involuntary action (salivating). Skinner studied how the action itself is conditioned through its own effects rather than other stimuli. He termed this action “operant” instead of “response” to highlight that the action was not just a response to a stimulus, but a voluntary action that is tangibly linked to its effects. 1 This led to his monumental framework: operant conditioning. Skinner, as well as the behaviorist paradigm, would come to define a key evolutionary step in psychology, as reinforcement theory began to move psychology away from it’s psychoanalytic roots and closer towards the empirical, scientific paradigm that it is today.

The story of reinforcement is the result of trying to understand the interplay between an action and its consequences, specifically how the probabilistic strengthening of this link operates.

Ivan Pavlov

A Russian physiologist known for his early research on classical conditioning. Pavlov did significant research in behaviorism – the systematic study of behaviors – and conditioning. Classical conditioning is notably different from operant conditioning: classical conditioning deals with involuntary behavior, whereas operant conditioning involves modifying voluntary behavior. Nevertheless, Pavlov was a major influence to all behaviorists, including practitioners of operant conditioning, like Skinner.

Edward Thorndike

An American psychologist and pioneer in the field of behaviorism. Thorndike developed a more empirically driven approach in assessing behavior. He formulated the Law of Effect, which stated that an action followed by a desirable effect strengthens the link between that action and the following effect, thereby making the action more likely to recur. While this may seem obvious to us now, Thorndike’s law of effect set the stage for empirical testing of reinforcement to occur.

Burrhus Frederick Skinner

An American psychologist best known for his seminal work on behavior, B.F. Skinner is known as the father of operant conditioning. He believed that people’s behavior is a result of how they have been conditioned by the consequences of their past behavior.

Consequences

Reinforcement theory can be a powerful way to promote positive behavior and is thus important to any team or organization. It is often used to achieve a team’s objectives, such as enhancing productivity or improving communication. Another way to visualize reinforcement theory is as a two-dimensional table, as shown below with examples in each quadrant:

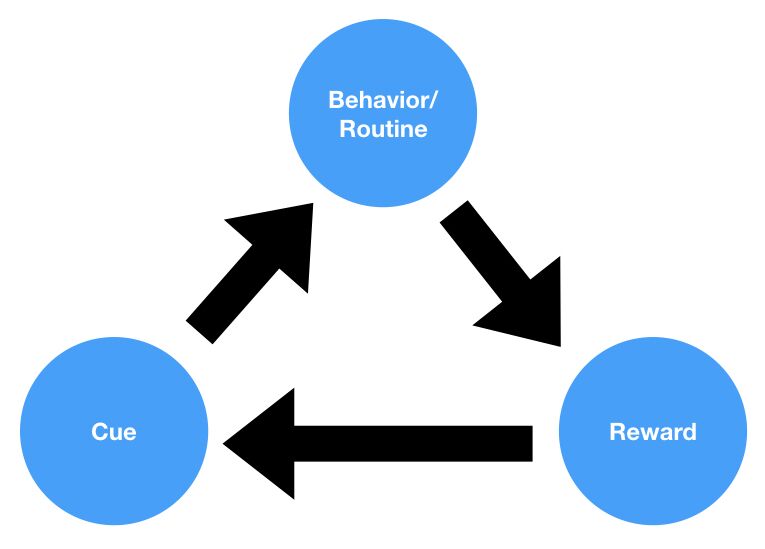

Reinforcement can also act as an enhancer for other behavioral techniques. For example, antecedents, such as warnings or providing information in an attempt to encourage certain behavior, are insubstantial on their own. However, when used in conjunction with reinforcing consequences, they are significantly more effective. 2 Thus when addressing workforce problems, modifying the consequences of actions can serve to enhance verbal suggestions.

Schedules of conditioning:

When building his theory of operant conditioning, Skinner found that his conditioning’s effectiveness was significantly altered by the schedule it was employed in. This led Skinner to develop a key concept in behaviorism, which is now known as schedules of reinforcement. The theory boils down to a simple, practical conclusion: to assure behavioral change, some reinforcement schedules may be better suited than others for a particular problem.

A reinforcement schedule can be continuous, meaning reinforcement will occur every time the target behavior happens. Another option is having reinforcement occur in fixed intervals, which are typically based on a certain period of time elapsing or after the behavior has been performed a certain number of times. Finally, a reinforcement schedule can reinforce behavior at variable intervals. In this case, the time or occurrences of the behavior are not fixed. In essence, an individual is rewarded on a random basis, regardless of behavior.

Controversies

Skinner was averse to examinations of the mind, discussions of goals, and internal motivations. 3 This perspective itself is a major point of disagreement in the psychology community, since it eliminates a whole angle of looking at behavior.

Some academics and studies have taken issue with the perceived efficacy of reinforcement theory. As early as 1994, it has been argued that behavioral therapists are increasingly adopting procedures supported by reinforcement theory that lack tangible empirical evidence of working in a clinical setting. 4 They point out that there have even been instances in which such procedures have had a counterproductive effect, suggesting that these techniques “may actually reduce positive behaviors and increase resistance to change.”

For example, Dan Pink suggests that having incentive-driven policies is effective when the task at hand is clear cut with straightforward rules, but otherwise it “ dulls thinking and blocks creativity.” In contrast, intrinsic motivation, feeling purposeful, and having autonomy may be better factors in increasing desirable behaviors. Strategies to encourage these behaviors could thus be more effective for complex tasks. 5

Finally, reinforcement theory can inadvertently influence our judgment, such as when we make decisions based on past experiences and discard new or contradicting information in doing so.

Case Studies

Seat belt reminders in cars.

While seat belts in cars have been mandatory since 1960, it was initially difficult to ensure that the mandate was being followed. 6 After years of figuring out the best way to enforce the rule, the seat belt reminder sound found its way into most cars. When the driver and passengers have not buckled up and the car starts moving, the car beeps loudly and relentlessly, until the seat belts are finally clicked. This annoying beeper is a classic example of negative reinforcement: after the target action is performed, the negative stimuli is removed. To avoid this annoyance in the future,we’re encouraged to put on the seat belt as early as possible next time we get in the car.

Examining the effect of positive reinforcement and punishment on cigarette use

When it comes to smoking, our experience with our first cigarette often dictates if we develop a dependence later on. In a 2018 study, researchers surveyed respondents on their feelings, reactions, and symptoms during the first few times they smoked. It was found that if our first cigarette was a positive experience, we tended to get hooked later on. This finding strongly suggests that reinforcement could be a key driver of habitual smoking, as we have come to associate it with positive feelings. On the other hand, they found that an unpleasant first experience, which acts as a positive punishment, did not significantly decrease the smoking frequency later in life. Accordingly, positive initiation experiences could predict cigarette use with some accuracy, whereas negative experiences could not. 7

Related TDL Content

Positive Reinforcement and Negative Reinforcement

Understanding the difference between positive and negative reinforcement is critical in using these behavioral catalysts correctly. To get a deeper dive into each reinforcement aspect of operant conditioning, check out these two guides that focus on positive and negative reinforcement.

Using Behavioral Insights to Stay Motivated at Work

Concepts from reinforcement theory often come into play in the workplace, and being aware of them can help us adopt helpful work habits. This article discusses how reinforcements like acknowledgement, appreciation, and knowing the impact of our work can be used to motivate ourselves and others.

- Skinner, B. F. (1937). Two Types of Conditioned Reflex: A Reply to Konorski and Miller. Journal of General Psychology , Vol. 16, No. 1, 272-279.

- A. (2016, February 1). Reinforcement Theory of Motivation – IResearchNet . Psychology. http://psychology.iresearchnet.com/industrial-organizational-psychology/leadership-and-management/reinforcement-theory-of-motivation/

- Banaji, M. R. (2011). Reinforcement Theory. The Harvard Gazette . Retrieved from https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2011/10/reinforcement-theory/

- Viken, R. & McFall, R. (1994). Paradox Lost: Implications of Contemporary Reinforcement Theory for Behavior Therapy. Current Directions in Psychological Science. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10770581

- Pink, D. (2009). The Puzzle of Motivation. TED Global. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/dan_pink_the_puzzle_of_motivation/transcript

- N.a. (2019). The Seat Belt Reminder – What’s that noise all about? News , IEE. Retrieved from https://www.iee-sensing.com/en/blog/details/2019/09/the-seat-belt-reminder-what-s-that-noise-all-about.html

About the Authors

Dan is a Co-Founder and Managing Director at The Decision Lab. He is a bestselling author of Intention - a book he wrote with Wiley on the mindful application of behavioral science in organizations. Dan has a background in organizational decision making, with a BComm in Decision & Information Systems from McGill University. He has worked on enterprise-level behavioral architecture at TD Securities and BMO Capital Markets, where he advised management on the implementation of systems processing billions of dollars per week. Driven by an appetite for the latest in technology, Dan created a course on business intelligence and lectured at McGill University, and has applied behavioral science to topics such as augmented and virtual reality.

Dr. Sekoul Krastev

Sekoul is a Co-Founder and Managing Director at The Decision Lab. He is a bestselling author of Intention - a book he wrote with Wiley on the mindful application of behavioral science in organizations. A decision scientist with a PhD in Decision Neuroscience from McGill University, Sekoul's work has been featured in peer-reviewed journals and has been presented at conferences around the world. Sekoul previously advised management on innovation and engagement strategy at The Boston Consulting Group as well as on online media strategy at Google. He has a deep interest in the applications of behavioral science to new technology and has published on these topics in places such as the Huffington Post and Strategy & Business.

Mental Models

Automatic Thinking

Human-Computer Interaction

Gestalt principles.

Eager to learn about how behavioral science can help your organization?

Get new behavioral science insights in your inbox every month..

Skinner’s Box Experiment (Behaviorism Study)

We receive rewards and punishments for many behaviors. More importantly, once we experience that reward or punishment, we are likely to perform (or not perform) that behavior again in anticipation of the result.

Psychologists in the late 1800s and early 1900s believed that rewards and punishments were crucial to shaping and encouraging voluntary behavior. But they needed a way to test it. And they needed a name for how rewards and punishments shaped voluntary behaviors. Along came Burrhus Frederic Skinner , the creator of Skinner's Box, and the rest is history.

What Is Skinner's Box?

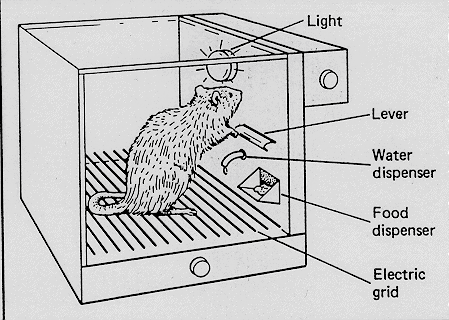

The "Skinner box" is a setup used in animal experiments. An animal is isolated in a box equipped with levers or other devices in this environment. The animal learns that pressing a lever or displaying specific behaviors can lead to rewards or punishments.

This setup was crucial for behavioral psychologist B.F. Skinner developed his theories on operant conditioning. It also aided in understanding the concept of reinforcement schedules.

Here, "schedules" refer to the timing and frequency of rewards or punishments, which play a key role in shaping behavior. Skinner's research showed how different schedules impact how animals learn and respond to stimuli.

Who is B.F. Skinner?

Burrhus Frederic Skinner, also known as B.F. Skinner is considered the “father of Operant Conditioning.” His experiments, conducted in what is known as “Skinner’s box,” are some of the most well-known experiments in psychology. They helped shape the ideas of operant conditioning in behaviorism.

Law of Effect (Thorndike vs. Skinner)

At the time, classical conditioning was the top theory in behaviorism. However, Skinner knew that research showed that voluntary behaviors could be part of the conditioning process. In the late 1800s, a psychologist named Edward Thorndike wrote about “The Law of Effect.” He said, “Responses that produce a satisfying effect in a particular situation become more likely to occur again in that situation, and responses that produce a discomforting effect become less likely to occur again in that situation.”

Thorndike tested out The Law of Effect with a box of his own. The box contained a maze and a lever. He placed a cat inside the box and a fish outside the box. He then recorded how the cats got out of the box and ate the fish.

Thorndike noticed that the cats would explore the maze and eventually found the lever. The level would let them out of the box, leading them to the fish faster. Once discovering this, the cats were more likely to use the lever when they wanted to get fish.

Skinner took this idea and ran with it. We call the box where animal experiments are performed "Skinner's box."

Why Do We Call This Box the "Skinner Box?"

Edward Thorndike used a box to train animals to perform behaviors for rewards. Later, psychologists like Martin Seligman used this apparatus to observe "learned helplessness." So why is this setup called a "Skinner Box?" Skinner not only used Skinner box experiments to show the existence of operant conditioning, but he also showed schedules in which operant conditioning was more or less effective, depending on your goals. And that is why he is called The Father of Operant Conditioning.

How Skinner's Box Worked

Inspired by Thorndike, Skinner created a box to test his theory of Operant Conditioning. (This box is also known as an “operant conditioning chamber.”)

The box was typically very simple. Skinner would place the rats in a Skinner box with neutral stimulants (that produced neither reinforcement nor punishment) and a lever that would dispense food. As the rats started to explore the box, they would stumble upon the level, activate it, and get food. Skinner observed that they were likely to engage in this behavior again, anticipating food. In some boxes, punishments would also be administered. Martin Seligman's learned helplessness experiments are a great example of using punishments to observe or shape an animal's behavior. Skinner usually worked with animals like rats or pigeons. And he took his research beyond what Thorndike did. He looked at how reinforcements and schedules of reinforcement would influence behavior.

About Reinforcements

Reinforcements are the rewards that satisfy your needs. The fish that cats received outside of Thorndike’s box was positive reinforcement. In Skinner box experiments, pigeons or rats also received food. But positive reinforcements can be anything added after a behavior is performed: money, praise, candy, you name it. Operant conditioning certainly becomes more complicated when it comes to human reinforcements.

Positive vs. Negative Reinforcements

Skinner also looked at negative reinforcements. Whereas positive reinforcements are given to subjects, negative reinforcements are rewards in the form of things taken away from subjects. In some experiments in the Skinner box, he would send an electric current through the box that would shock the rats. If the rats pushed the lever, the shocks would stop. The removal of that terrible pain was a negative reinforcement. The rats still sought the reinforcement but were not gaining anything when the shocks ended. Skinner saw that the rats quickly learned to turn off the shocks by pushing the lever.

About Punishments

Skinner's Box also experimented with positive or negative punishments, in which harmful or unsatisfying things were taken away or given due to "bad behavior." For now, let's focus on the schedules of reinforcement.

Schedules of Reinforcement

We know that not every behavior has the same reinforcement every single time. Think about tipping as a rideshare driver or a barista at a coffee shop. You may have a string of customers who tip you generously after conversing with them. At this point, you’re likely to converse with your next customer. But what happens if they don’t tip you after you have a conversation with them? What happens if you stay silent for one ride and get a big tip?

Psychologists like Skinner wanted to know how quickly someone makes a behavior a habit after receiving reinforcement. Aka, how many trips will it take for you to converse with passengers every time? They also wanted to know how fast a subject would stop conversing with passengers if you stopped getting tips. If the rat pulls the lever and doesn't get food, will they stop pulling the lever altogether?

Skinner attempted to answer these questions by looking at different schedules of reinforcement. He would offer positive reinforcements on different schedules, like offering it every time the behavior was performed (continuous reinforcement) or at random (variable ratio reinforcement.) Based on his experiments, he would measure the following:

- Response rate (how quickly the behavior was performed)

- Extinction rate (how quickly the behavior would stop)

He found that there are multiple schedules of reinforcement, and they all yield different results. These schedules explain why your dog may not be responding to the treats you sometimes give him or why gambling can be so addictive. Not all of these schedules are possible, and that's okay, too.

Continuous Reinforcement

If you reinforce a behavior repeatedly, the response rate is medium, and the extinction rate is fast. The behavior will be performed only when reinforcement is needed. As soon as you stop reinforcing a behavior on this schedule, the behavior will not be performed.

Fixed-Ratio Reinforcement

Let’s say you reinforce the behavior every fourth or fifth time. The response rate is fast, and the extinction rate is medium. The behavior will be performed quickly to reach the reinforcement.

Fixed-Interval Reinforcement

In the above cases, the reinforcement was given immediately after the behavior was performed. But what if the reinforcement was given at a fixed interval, provided that the behavior was performed at some point? Skinner found that the response rate is medium, and the extinction rate is medium.

Variable-Ratio Reinforcement

Here's how gambling becomes so unpredictable and addictive. In gambling, you experience occasional wins, but you often face losses. This uncertainty keeps you hooked, not knowing when the next big win, or dopamine hit, will come. The behavior gets reinforced randomly. When gambling, your response is quick, but it takes a long time to stop wanting to gamble. This randomness is a key reason why gambling is highly addictive.

Variable-Interval Reinforcement

Last, the reinforcement is given out at random intervals, provided that the behavior is performed. Health inspectors or secret shoppers are commonly used examples of variable-interval reinforcement. The reinforcement could be administered five minutes after the behavior is performed or seven hours after the behavior is performed. Skinner found that the response rate for this schedule is fast, and the extinction rate is slow.

Skinner's Box and Pigeon Pilots in World War II

Yes, you read that right. Skinner's work with pigeons and other animals in Skinner's box had real-life effects. After some time training pigeons in his boxes, B.F. Skinner got an idea. Pigeons were easy to train. They can see very well as they fly through the sky. They're also quite calm creatures and don't panic in intense situations. Their skills could be applied to the war that was raging on around him.

B.F. Skinner decided to create a missile that pigeons would operate. That's right. The U.S. military was having trouble accurately targeting missiles, and B.F. Skinner believed pigeons could help. He believed he could train the pigeons to recognize a target and peck when they saw it. As the pigeons pecked, Skinner's specially designed cockpit would navigate appropriately. Pigeons could be pilots in World War II missions, fighting Nazi Germany.

When Skinner proposed this idea to the military, he was met with skepticism. Yet, he received $25,000 to start his work on "Project Pigeon." The device worked! Operant conditioning trained pigeons to navigate missiles appropriately and hit their targets. Unfortunately, there was one problem. The mission killed the pigeons once the missiles were dropped. It would require a lot of pigeons! The military eventually passed on the project, but cockpit prototypes are on display at the American History Museum. Pretty cool, huh?

Examples of Operant Conditioning in Everyday Life

Not every example of operant conditioning has to end in dropping missiles. Nor does it have to happen in a box in a laboratory! You might find that you have used operant conditioning on yourself, a pet, or a child whose behavior changes with rewards and punishments. These operant conditioning examples will look into what this process can do for behavior and personality.

Hot Stove: If you put your hand on a hot stove, you will get burned. More importantly, you are very unlikely to put your hand on that hot stove again. Even though no one has made that stove hot as a punishment, the process still works.

Tips: If you converse with a passenger while driving for Uber, you might get an extra tip at the end of your ride. That's certainly a great reward! You will likely keep conversing with passengers as you drive for Uber. The same type of behavior applies to any service worker who gets tips!

Training a Dog: If your dog sits when you say “sit,” you might treat him. More importantly, they are likely to sit when you say, “sit.” (This is a form of variable-ratio reinforcement. Likely, you only treat your dog 50-90% of the time they sit. If you gave a dog a treat every time they sat, they probably wouldn't have room for breakfast or dinner!)

Operant Conditioning Is Everywhere!

We see operant conditioning training us everywhere, intentionally or unintentionally! Game makers and app developers design their products based on the "rewards" our brains feel when seeing notifications or checking into the app. Schoolteachers use rewards to control their unruly classes. Dog training doesn't always look different from training your child to do chores. We know why this happens, thanks to experiments like the ones performed in Skinner's box.

Related posts:

- Operant Conditioning (Examples + Research)

- Edward Thorndike (Psychologist Biography)

- Schedules of Reinforcement (Examples)

- B.F. Skinner (Psychologist Biography)

- Fixed Ratio Reinforcement Schedule (Examples)

Reference this article:

About The Author

Free Personality Test

Free Memory Test

Free IQ Test

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Operant Conditioning: What It Is, How It Works, and Examples

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Operant conditioning, or instrumental conditioning, is a theory of learning where behavior is influenced by its consequences. Behavior that is reinforced (rewarded) will likely be repeated, and behavior that is punished will occur less frequently.

By the 1920s, John B. Watson had left academic psychology, and other behaviorists were becoming influential, proposing new forms of learning other than classical conditioning . Perhaps the most important of these was Burrhus Frederic Skinner. Although, for obvious reasons, he is more commonly known as B.F. Skinner.

Skinner’s views were slightly less extreme than Watson’s (1913). Skinner believed that we do have such a thing as a mind, but that it is simply more productive to study observable behavior rather than internal mental events.

The work of Skinner was rooted in the view that classical conditioning was far too simplistic to be a complete explanation of complex human behavior. He believed that the best way to understand behavior is to look at the causes of an action and its consequences. He called this approach operant conditioning.

How It Works

Skinner is regarded as the father of Operant Conditioning, but his work was based on Thorndike’s (1898) Law of Effect . According to this principle, behavior that is followed by pleasant consequences is likely to be repeated, and behavior followed by unpleasant consequences is less likely to be repeated.

Skinner introduced a new term into the Law of Effect – Reinforcement. Behavior that is reinforced tends to be repeated (i.e., strengthened); behavior that is not reinforced tends to die out or be extinguished (i.e., weakened).

Skinner (1948) studied operant conditioning by conducting experiments using animals which he placed in a “ Skinner Box ” which was similar to Thorndike’s puzzle box.

A Skinner box, also known as an operant conditioning chamber, is a device used to objectively record an animal’s behavior in a compressed time frame. An animal can be rewarded or punished for engaging in certain behaviors, such as lever pressing (for rats) or key pecking (for pigeons).

Skinner identified three types of responses, or operant, that can follow behavior.

- Neutral operants : responses from the environment that neither increase nor decrease the probability of a behavior being repeated.

- Reinforcers : Responses from the environment that increase the probability of a behavior being repeated. Reinforcers can be either positive or negative.

- Punishers : Responses from the environment that decrease the likelihood of a behavior being repeated. Punishment weakens behavior.

We can all think of examples of how our own behavior has been affected by reinforcers and punishers. As a child, you probably tried out a number of behaviors and learned from their consequences.

For example, when you were younger, if you tried smoking at school, and the chief consequence was that you got in with the crowd you always wanted to hang out with, you would have been positively reinforced (i.e., rewarded) and would be likely to repeat the behavior.

If, however, the main consequence was that you were caught, caned, suspended from school, and your parents became involved, you would most certainly have been punished, and you would consequently be much less likely to smoke now.

Positive Reinforcement

Positive reinforcement is a term described by B. F. Skinner in his theory of operant conditioning. In positive reinforcement, a response or behavior is strengthened by rewards, leading to the repetition of desired behavior. The reward is a reinforcing stimulus.

Primary reinforcers are stimuli that are naturally reinforcing because they are not learned and directly satisfy a need, such as food or water.

Secondary reinforcers are stimuli that are reinforced through their association with a primary reinforcer, such as money, school grades. They do not directly satisfy an innate need but may be the means. So a secondary reinforcer can be just as powerful a motivator as a primary reinforcer.

Skinner showed how positive reinforcement worked by placing a hungry rat in his Skinner box. The box contained a lever on the side, and as the rat moved about the box, it would accidentally knock the lever. Immediately it did so that a food pellet would drop into a container next to the lever.

The rats quickly learned to go straight to the lever after being put in the box a few times. The consequence of receiving food, if they pressed the lever, ensured that they would repeat the action again and again.

Positive reinforcement strengthens a behavior by providing a consequence an individual finds rewarding. For example, if your teacher gives you £5 each time you complete your homework (i.e., a reward), you will be more likely to repeat this behavior in the future, thus strengthening the behavior of completing your homework.

The Premack principle is a form of positive reinforcement in operant conditioning. It suggests using a preferred activity (high-probability behavior) as a reward for completing a less preferred one (low-probability behavior).

This method incentivizes the less desirable behavior by associating it with a desirable outcome, thus strengthening the less favored behavior.

Negative Reinforcement

Negative reinforcement is the termination of an unpleasant state following a response.

This is known as negative reinforcement because it is the removal of an adverse stimulus which is ‘rewarding’ to the animal or person. Negative reinforcement strengthens behavior because it stops or removes an unpleasant experience.

For example, if you do not complete your homework, you give your teacher £5. You will complete your homework to avoid paying £5, thus strengthening the behavior of completing your homework.

Skinner showed how negative reinforcement worked by placing a rat in his Skinner box and then subjecting it to an unpleasant electric current which caused it some discomfort. As the rat moved about the box it would accidentally knock the lever.

Immediately, it did so the electric current would be switched off. The rats quickly learned to go straight to the lever after a few times of being put in the box. The consequence of escaping the electric current ensured that they would repeat the action again and again.

In fact, Skinner even taught the rats to avoid the electric current by turning on a light just before the electric current came on. The rats soon learned to press the lever when the light came on because they knew that this would stop the electric current from being switched on.

These two learned responses are known as Escape Learning and Avoidance Learning .

Punishment is the opposite of reinforcement since it is designed to weaken or eliminate a response rather than increase it. It is an aversive event that decreases the behavior that it follows.

Like reinforcement, punishment can work either by directly applying an unpleasant stimulus like a shock after a response or by removing a potentially rewarding stimulus, for instance, deducting someone’s pocket money to punish undesirable behavior.

Note : It is not always easy to distinguish between punishment and negative reinforcement.

They are two distinct methods of punishment used to decrease the likelihood of a specific behavior occurring again, but they involve different types of consequences:

Positive Punishment :

- Positive punishment involves adding an aversive stimulus or something unpleasant immediately following a behavior to decrease the likelihood of that behavior happening in the future.

- It aims to weaken the target behavior by associating it with an undesirable consequence.

- Example : A child receives a scolding (an aversive stimulus) from their parent immediately after hitting their sibling. This is intended to decrease the likelihood of the child hitting their sibling again.

Negative Punishment :

- Negative punishment involves removing a desirable stimulus or something rewarding immediately following a behavior to decrease the likelihood of that behavior happening in the future.

- It aims to weaken the target behavior by taking away something the individual values or enjoys.

- Example : A teenager loses their video game privileges (a desirable stimulus) for not completing their chores. This is intended to decrease the likelihood of the teenager neglecting their chores in the future.

There are many problems with using punishment, such as:

- Punished behavior is not forgotten, it’s suppressed – behavior returns when punishment is no longer present.

- Causes increased aggression – shows that aggression is a way to cope with problems.

- Creates fear that can generalize to undesirable behaviors, e.g., fear of school.

- Does not necessarily guide you toward desired behavior – reinforcement tells you what to do, and punishment only tells you what not to do.

Examples of Operant Conditioning

Positive Reinforcement : Suppose you are a coach and want your team to improve their passing accuracy in soccer. When the players execute accurate passes during training, you praise their technique. This positive feedback encourages them to repeat the correct passing behavior.

Negative Reinforcement : If you notice your team working together effectively and exhibiting excellent team spirit during a tough training session, you might end the training session earlier than planned, which the team perceives as a relief. They understand that teamwork leads to positive outcomes, reinforcing team behavior.

Negative Punishment : If an office worker continually arrives late, their manager might revoke the privilege of flexible working hours. This removal of a positive stimulus encourages the employee to be punctual.

Positive Reinforcement : Training a cat to use a litter box can be achieved by giving it a treat each time it uses it correctly. The cat will associate the behavior with the reward and will likely repeat it.

Negative Punishment : If teenagers stay out past their curfew, their parents might take away their gaming console for a week. This makes the teenager more likely to respect their curfew in the future to avoid losing something they value.

Ineffective Punishment : Your child refuses to finish their vegetables at dinner. You punish them by not allowing dessert, but the child still refuses to eat vegetables next time. The punishment seems ineffective.

Premack Principle Application : You could motivate your child to eat vegetables by offering an activity they love after they finish their meal. For instance, for every vegetable eaten, they get an extra five minutes of video game time. They value video game time, which might encourage them to eat vegetables.

Other Premack Principle Examples :

- A student who dislikes history but loves art might earn extra time in the art studio for each history chapter reviewed.

- For every 10 minutes a person spends on household chores, they can spend 5 minutes on a favorite hobby.

- For each successful day of healthy eating, an individual allows themselves a small piece of dark chocolate at the end of the day.

- A child can choose between taking out the trash or washing the dishes. Giving them the choice makes them more likely to complete the chore willingly.

Skinner’s Pigeon Experiment

B.F. Skinner conducted several experiments with pigeons to demonstrate the principles of operant conditioning.

One of the most famous of these experiments is often colloquially referred to as “ Superstition in the Pigeon .”

This experiment was conducted to explore the effects of non-contingent reinforcement on pigeons, leading to some fascinating observations that can be likened to human superstitions.

Non-contingent reinforcement (NCR) refers to a method in which rewards (or reinforcements) are delivered independently of the individual’s behavior. In other words, the reinforcement is given at set times or intervals, regardless of what the individual is doing.

The Experiment:

- Pigeons were brought to a state of hunger, reduced to 75% of their well-fed weight.

- They were placed in a cage with a food hopper that could be presented for five seconds at a time.

- Instead of the food being given as a result of any specific action by the pigeon, it was presented at regular intervals, regardless of the pigeon’s behavior.

Observation:

- Over time, Skinner observed that the pigeons began to associate whatever random action they were doing when food was delivered with the delivery of the food itself.

- This led the pigeons to repeat these actions, believing (in anthropomorphic terms) that their behavior was causing the food to appear.

- In most cases, pigeons developed different “superstitious” behaviors or rituals. For instance, one pigeon would turn counter-clockwise between food presentations, while another would thrust its head into a cage corner.

- These behaviors did not appear until the food hopper was introduced and presented periodically.

- These behaviors were not initially related to the food delivery but became linked in the pigeon’s mind due to the coincidental timing of the food dispensing.

- The behaviors seemed to be associated with the environment, suggesting the pigeons were responding to certain aspects of their surroundings.

- The rate of reinforcement (how often the food was presented) played a significant role. Shorter intervals between food presentations led to more rapid and defined conditioning.

- Once a behavior was established, the interval between reinforcements could be increased without diminishing the behavior.

Superstitious Behavior:

The pigeons began to act as if their behaviors had a direct effect on the presentation of food, even though there was no such connection. This is likened to human superstitions, where rituals are believed to change outcomes, even if they have no real effect.

For example, a card player might have rituals to change their luck, or a bowler might make gestures believing they can influence a ball already in motion.

Conclusion:

This experiment demonstrates that behaviors can be conditioned even without a direct cause-and-effect relationship. Just like humans, pigeons can develop “superstitious” behaviors based on coincidental occurrences.

This study not only sheds light on the intricacies of operant conditioning but also draws parallels between animal and human behaviors in the face of random reinforcements.

Schedules of Reinforcement

Imagine a rat in a “Skinner box.” In operant conditioning, if no food pellet is delivered immediately after the lever is pressed then after several attempts the rat stops pressing the lever (how long would someone continue to go to work if their employer stopped paying them?). The behavior has been extinguished.

Behaviorists discovered that different patterns (or schedules) of reinforcement had different effects on the speed of learning and extinction. Ferster and Skinner (1957) devised different ways of delivering reinforcement and found that this had effects on

1. The Response Rate – The rate at which the rat pressed the lever (i.e., how hard the rat worked).

2. The Extinction Rate – The rate at which lever pressing dies out (i.e., how soon the rat gave up).

Skinner found that the type of reinforcement which produces the slowest rate of extinction (i.e., people will go on repeating the behavior for the longest time without reinforcement) is variable-ratio reinforcement. The type of reinforcement which has the quickest rate of extinction is continuous reinforcement.

(A) Continuous Reinforcement

An animal/human is positively reinforced every time a specific behavior occurs, e.g., every time a lever is pressed a pellet is delivered, and then food delivery is shut off.

- Response rate is SLOW

- Extinction rate is FAST

(B) Fixed Ratio Reinforcement

Behavior is reinforced only after the behavior occurs a specified number of times. e.g., one reinforcement is given after every so many correct responses, e.g., after every 5th response. For example, a child receives a star for every five words spelled correctly.

- Response rate is FAST

- Extinction rate is MEDIUM

(C) Fixed Interval Reinforcement

One reinforcement is given after a fixed time interval providing at least one correct response has been made. An example is being paid by the hour. Another example would be every 15 minutes (half hour, hour, etc.) a pellet is delivered (providing at least one lever press has been made) then food delivery is shut off.

- Response rate is MEDIUM

(D) Variable Ratio Reinforcement

behavior is reinforced after an unpredictable number of times. For examples gambling or fishing.

- Extinction rate is SLOW (very hard to extinguish because of unpredictability)

(E) Variable Interval Reinforcement

Providing one correct response has been made, reinforcement is given after an unpredictable amount of time has passed, e.g., on average every 5 minutes. An example is a self-employed person being paid at unpredictable times.

- Extinction rate is SLOW

Applications In Psychology

1. behavior modification therapy.

Behavior modification is a set of therapeutic techniques based on operant conditioning (Skinner, 1938, 1953). The main principle comprises changing environmental events that are related to a person’s behavior. For example, the reinforcement of desired behaviors and ignoring or punishing undesired ones.

This is not as simple as it sounds — always reinforcing desired behavior, for example, is basically bribery.

There are different types of positive reinforcements. Primary reinforcement is when a reward strengths a behavior by itself. Secondary reinforcement is when something strengthens a behavior because it leads to a primary reinforcer.

Examples of behavior modification therapy include token economy and behavior shaping.

Token Economy

Token economy is a system in which targeted behaviors are reinforced with tokens (secondary reinforcers) and later exchanged for rewards (primary reinforcers).

Tokens can be in the form of fake money, buttons, poker chips, stickers, etc. While the rewards can range anywhere from snacks to privileges or activities. For example, teachers use token economy at primary school by giving young children stickers to reward good behavior.

Token economy has been found to be very effective in managing psychiatric patients . However, the patients can become over-reliant on the tokens, making it difficult for them to adjust to society once they leave prison, hospital, etc.

Staff implementing a token economy program have a lot of power. It is important that staff do not favor or ignore certain individuals if the program is to work. Therefore, staff need to be trained to give tokens fairly and consistently even when there are shift changes such as in prisons or in a psychiatric hospital.

Behavior Shaping

A further important contribution made by Skinner (1951) is the notion of behavior shaping through successive approximation.

Skinner argues that the principles of operant conditioning can be used to produce extremely complex behavior if rewards and punishments are delivered in such a way as to encourage move an organism closer and closer to the desired behavior each time.

In shaping, the form of an existing response is gradually changed across successive trials towards a desired target behavior by rewarding exact segments of behavior.

To do this, the conditions (or contingencies) required to receive the reward should shift each time the organism moves a step closer to the desired behavior.

According to Skinner, most animal and human behavior (including language) can be explained as a product of this type of successive approximation.

2. Educational Applications

In the conventional learning situation, operant conditioning applies largely to issues of class and student management, rather than to learning content. It is very relevant to shaping skill performance.

A simple way to shape behavior is to provide feedback on learner performance, e.g., compliments, approval, encouragement, and affirmation.

A variable-ratio produces the highest response rate for students learning a new task, whereby initial reinforcement (e.g., praise) occurs at frequent intervals, and as the performance improves reinforcement occurs less frequently, until eventually only exceptional outcomes are reinforced.

For example, if a teacher wanted to encourage students to answer questions in class they should praise them for every attempt (regardless of whether their answer is correct). Gradually the teacher will only praise the students when their answer is correct, and over time only exceptional answers will be praised.

Unwanted behaviors, such as tardiness and dominating class discussion can be extinguished through being ignored by the teacher (rather than being reinforced by having attention drawn to them). This is not an easy task, as the teacher may appear insincere if he/she thinks too much about the way to behave.

Knowledge of success is also important as it motivates future learning. However, it is important to vary the type of reinforcement given so that the behavior is maintained.

This is not an easy task, as the teacher may appear insincere if he/she thinks too much about the way to behave.

Operant Conditioning vs. Classical Conditioning

Learning type.

While both types of conditioning involve learning, classical conditioning is passive (automatic response to stimuli), while operant conditioning is active (behavior is influenced by consequences).

- Classical conditioning links an involuntary response with a stimulus. It happens passively on the part of the learner, without rewards or punishments. An example is a dog salivating at the sound of a bell associated with food.

- Operant conditioning connects voluntary behavior with a consequence. Operant conditioning requires the learner to actively participate and perform some type of action to be rewarded or punished. It’s active, with the learner’s behavior influenced by rewards or punishments. An example is a dog sitting on command to get a treat.

Learning Process

Classical conditioning involves learning through associating stimuli resulting in involuntary responses, while operant conditioning focuses on learning through consequences, shaping voluntary behaviors.

Over time, the person responds to the neutral stimulus as if it were the unconditioned stimulus, even when presented alone. The response is involuntary and automatic.

An example is a dog salivating (response) at the sound of a bell (neutral stimulus) after it has been repeatedly paired with food (unconditioned stimulus).

Behavior followed by pleasant consequences (rewards) is more likely to be repeated, while behavior followed by unpleasant consequences (punishments) is less likely to be repeated.

For instance, if a child gets praised (pleasant consequence) for cleaning their room (behavior), they’re more likely to clean their room in the future.

Conversely, if they get scolded (unpleasant consequence) for not doing their homework, they’re more likely to complete it next time to avoid the scolding.

Timing of Stimulus & Response

The timing of the response relative to the stimulus differs between classical and operant conditioning:

Classical Conditioning (response after the stimulus) : In this form of conditioning, the response occurs after the stimulus. The behavior (response) is determined by what precedes it (stimulus).

For example, in Pavlov’s classic experiment, the dogs started to salivate (response) after they heard the bell (stimulus) because they associated it with food.

The anticipated consequence influences the behavior or what follows it. It is a more active form of learning, where behaviors are reinforced or punished, thus influencing their likelihood of repetition.

For example, a child might behave well (behavior) in anticipation of a reward (consequence), or avoid a certain behavior to prevent a potential punishment.

Looking at Skinner’s classic studies on pigeons’ / rat’s behavior we can identify some of the major assumptions of the behaviorist approach .

• Psychology should be seen as a science , to be studied in a scientific manner. Skinner’s study of behavior in rats was conducted under carefully controlled laboratory conditions . • Behaviorism is primarily concerned with observable behavior, as opposed to internal events like thinking and emotion. Note that Skinner did not say that the rats learned to press a lever because they wanted food. He instead concentrated on describing the easily observed behavior that the rats acquired. • The major influence on human behavior is learning from our environment. In the Skinner study, because food followed a particular behavior the rats learned to repeat that behavior, e.g., operant conditioning. • There is little difference between the learning that takes place in humans and that in other animals. Therefore research (e.g., operant conditioning) can be carried out on animals (Rats / Pigeons) as well as on humans. Skinner proposed that the way humans learn behavior is much the same as the way the rats learned to press a lever.

So, if your layperson’s idea of psychology has always been of people in laboratories wearing white coats and watching hapless rats try to negotiate mazes in order to get to their dinner, then you are probably thinking of behavioral psychology.

Behaviorism and its offshoots tend to be among the most scientific of the psychological perspectives . The emphasis of behavioral psychology is on how we learn to behave in certain ways.

We are all constantly learning new behaviors and how to modify our existing behavior. behavioral psychology is the psychological approach that focuses on how this learning takes place.

Critical Evaluation

Operant conditioning can be used to explain a wide variety of behaviors, from the process of learning, to addiction and language acquisition . It also has practical applications (such as token economy) which can be applied in classrooms, prisons and psychiatric hospitals.

Researchers have found innovative ways to apply operant conditioning principles to promote health and habit change in humans.

In a recent study, operant conditioning using virtual reality (VR) helped stroke patients use their weakened limb more often during rehabilitation. Patients shifted their weight in VR games by maneuvering a virtual object. When they increased weight on their weakened side, they received rewards like stars. This positive reinforcement conditioned greater paretic limb use (Kumar et al., 2019).

Another study utilized operant conditioning to assist smoking cessation. Participants earned vouchers exchangeable for goods and services for reducing smoking. This reward system reinforced decreasing cigarette use. Many participants achieved long-term abstinence (Dallery et al., 2017).

Through repeated reinforcement, operant conditioning can facilitate forming exercise and eating habits. A person trying to exercise more might earn TV time for every 10 minutes spent working out. An individual aiming to eat healthier may allow themselves a daily dark chocolate square for sticking to nutritious meals. Providing consistent rewards for desired actions can instill new habits (Michie et al., 2009).

Apps like Habitica apply operant conditioning by gamifying habit tracking. Users earn points and collect rewards in a fantasy game for completing real-life habits. This virtual reinforcement helps ingrain positive behaviors (Eckerstorfer et al., 2019).

Operant conditioning also shows promise for managing ADHD and OCD. Rewarding concentration and focus in ADHD children, for example, can strengthen their attention skills (Rosén et al., 2018). Similarly, reinforcing OCD patients for resisting compulsions may diminish obsessive behaviors (Twohig et al., 2018).

However, operant conditioning fails to take into account the role of inherited and cognitive factors in learning, and thus is an incomplete explanation of the learning process in humans and animals.

For example, Kohler (1924) found that primates often seem to solve problems in a flash of insight rather than be trial and error learning. Also, social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) suggests that humans can learn automatically through observation rather than through personal experience.

The use of animal research in operant conditioning studies also raises the issue of extrapolation. Some psychologists argue we cannot generalize from studies on animals to humans as their anatomy and physiology are different from humans, and they cannot think about their experiences and invoke reason, patience, memory or self-comfort.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who discovered operant conditioning.

Operant conditioning was discovered by B.F. Skinner, an American psychologist, in the mid-20th century. Skinner is often regarded as the father of operant conditioning, and his work extensively dealt with the mechanism of reward and punishment for behaviors, with the concept being that behaviors followed by positive outcomes are reinforced, while those followed by negative outcomes are discouraged.

How does operant conditioning differ from classical conditioning?

Operant conditioning differs from classical conditioning, focusing on how voluntary behavior is shaped and maintained by consequences, such as rewards and punishments.

In operant conditioning, a behavior is strengthened or weakened based on the consequences that follow it. In contrast, classical conditioning involves the association of a neutral stimulus with a natural response, creating a new learned response.

While both types of conditioning involve learning and behavior modification, operant conditioning emphasizes the role of reinforcement and punishment in shaping voluntary behavior.

How does operant conditioning relate to social learning theory?

Operant conditioning is a core component of social learning theory , which emphasizes the importance of observational learning and modeling in acquiring and modifying behavior.

Social learning theory suggests that individuals can learn new behaviors by observing others and the consequences of their actions, which is similar to the reinforcement and punishment processes in operant conditioning.

By observing and imitating models, individuals can acquire new skills and behaviors and modify their own behavior based on the outcomes they observe in others.

Overall, both operant conditioning and social learning theory highlight the importance of environmental factors in shaping behavior and learning.

What are the downsides of operant conditioning?

The downsides of using operant conditioning on individuals include the potential for unintended negative consequences, particularly with the use of punishment. Punishment may lead to increased aggression or avoidance behaviors.

Additionally, some behaviors may be difficult to shape or modify using operant conditioning techniques, particularly when they are highly ingrained or tied to complex internal states.

Furthermore, individuals may resist changing their behaviors to meet the expectations of others, particularly if they perceive the demands or consequences of the reinforcement or punishment to be undesirable or unjust.

What is an application of bf skinner’s operant conditioning theory?

An application of B.F. Skinner’s operant conditioning theory is seen in education and classroom management. Teachers use positive reinforcement (rewards) to encourage good behavior and academic achievement, and negative reinforcement or punishment to discourage disruptive behavior.

For example, a student may earn extra recess time (positive reinforcement) for completing homework on time, or lose the privilege to use class computers (negative punishment) for misbehavior.

Further Reading

- Ivan Pavlov Classical Conditioning Learning and behavior PowerPoint

- Ayllon, T., & Michael, J. (1959). The psychiatric nurse as a behavioral engineer. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 2(4), 323-334.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Dallery, J., Meredith, S., & Glenn, I. M. (2017). A deposit contract method to deliver abstinence reinforcement for cigarette smoking. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 50 (2), 234–248.

- Eckerstorfer, L., Tanzer, N. K., Vogrincic-Haselbacher, C., Kedia, G., Brohmer, H., Dinslaken, I., & Corbasson, R. (2019). Key elements of mHealth interventions to successfully increase physical activity: Meta-regression. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 7 (11), e12100.

- Ferster, C. B., & Skinner, B. F. (1957). Schedules of reinforcement . New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Kohler, W. (1924). The mentality of apes. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Kumar, D., Sinha, N., Dutta, A., & Lahiri, U. (2019). Virtual reality-based balance training system augmented with operant conditioning paradigm. Biomedical Engineering Online , 18 (1), 1-23.

- Michie, S., Abraham, C., Whittington, C., McAteer, J., & Gupta, S. (2009). Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: A meta-regression. Health Psychology, 28 (6), 690–701.

- Rosén, E., Westerlund, J., Rolseth, V., Johnson R. M., Viken Fusen, A., Årmann, E., Ommundsen, R., Lunde, L.-K., Ulleberg, P., Daae Zachrisson, H., & Jahnsen, H. (2018). Effects of QbTest-guided ADHD treatment: A randomized controlled trial. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27 (4), 447–459.

- Skinner, B. F. (1948). ‘Superstition’in the pigeon. Journal of experimental psychology , 38 (2), 168.

- Schunk, D. (2016). Learning theories: An educational perspective . Pearson.

- Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis . New York: Appleton-Century.

- Skinner, B. F. (1948). Superstition” in the pigeon . Journal of Experimental Psychology, 38 , 168-172.

- Skinner, B. F. (1951). How to teach animals . Freeman.

- Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior . Macmillan.

- Thorndike, E. L. (1898). Animal intelligence: An experimental study of the associative processes in animals. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 2(4), i-109.

- Twohig, M. P., Whittal, M. L., Cox, J. M., & Gunter, R. (2010). An initial investigation into the processes of change in ACT, CT, and ERP for OCD. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 6 (2), 67–83.

- Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it . Psychological Review, 20 , 158–177.

Related Articles

Soft Determinism In Psychology

Branches of Psychology

Social Action Theory (Weber): Definition & Examples

Adult Attachment , Personality , Psychology , Relationships

Attachment Styles and How They Affect Adult Relationships

Learning Theories , Psychology

Behaviorism In Psychology

Personality , Psychology

Big Five Personality Traits: The 5-Factor Model of Personality

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, reinforcement theory: a practical tool.

Leadership & Organization Development Journal

ISSN : 0143-7739

Article publication date: 1 February 1991

A “process” theory of motivation is explored, namely reinforcement theory. Reinforcement theory is defined and the four primary strategies for implementing it – positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, punishment and extinction – are described. The advantages and disadvantages of each strategy and the ways of scheduling these are outlined, together with a discussion of current research and practical implications of the theory.

Villere, M.F. and Hartman, S.S. (1991), "Reinforcement Theory: A Practical Tool", Leadership & Organization Development Journal , Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 27-31. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437739110138039

Copyright © 1991, MCB UP Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Search site

What is reinforcement theory in behavioral science, what is reinforcement theory.

Reinforcement theory is a concept in behavioral psychology that suggests that behavior is driven by its consequences. Initially developed by psychologist B.F. Skinner, reinforcement theory states that rewarded behaviors are likely to be repeated, while punished behaviors are likely to cease. The theory underlines the importance of consequences as motivating factors in decision-making and action, focusing on observable behavior rather than internal mental states.

Reinforcement can be either positive or negative, and both types play a crucial role in shaping behavior. Positive reinforcement involves the addition of a rewarding stimulus to increase the likelihood of a behavior, while negative reinforcement involves the removal of an adverse stimulus to encourage behavior. On the other hand, punishment, which can also be positive (adding an adverse stimulus) or negative (removing a pleasant stimulus), aims to reduce or eliminate undesirable behavior.

Examples of Reinforcement Theory

In education, reinforcement theory is often applied to motivate learning and improve student behavior. For instance, positive reinforcement can take the form of praise, good grades, or rewards for completing homework or behaving appropriately in class. Negative reinforcement might involve removing an undesirable task when the student demonstrates good behavior.

Workplace Behavior

Reinforcement theory is frequently used in the workplace to encourage productive behavior and discourage counterproductive behavior. For instance, an employee might receive a bonus (positive reinforcement) for meeting a sales target or be allowed to leave early (negative reinforcement) after completing a challenging task. Conversely, reprimands or pay deductions can be used as punishment to discourage poor performance or unprofessional conduct.

Behavioral Therapy

In psychology, reinforcement theory is applied in behavioral therapies, such as Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) used to treat conditions like autism. Positive behaviors might be reinforced through praise or rewards, while harmful behaviors might be discouraged through time-outs or removal of privileges.

Significance of Reinforcement Theory

Reinforcement theory is a fundamental concept in behavioral psychology, with wide-ranging applications. It offers a practical framework for understanding how behavior can be shaped and modified over time, which is particularly valuable in fields like education, therapy, and management. By focusing on the consequences of behavior, reinforcement theory provides concrete strategies for encouraging desirable behavior and discouraging undesirable behavior, influencing everything from classroom dynamics to organizational culture.

Controversies and Criticisms of Reinforcement Theory

While reinforcement theory has had a significant impact on behavioral psychology, it has faced criticism. Some critics argue that the theory oversimplifies human behavior by focusing solely on observable behaviors and ignoring internal mental processes. Others suggest that extrinsic rewards and punishments can undermine intrinsic motivation, leading to a decrease in interest or engagement once the reinforcement is removed. Additionally, critics note that the effectiveness of reinforcement can vary greatly among individuals due to factors such as personality, cultural context, and past experiences.

Related Behavioral Science Terms

Belief perseverance, crystallized intelligence, extraneous variable, representative sample, factor analysis, egocentrism, stimulus generalization, reciprocal determinism, divergent thinking, convergent thinking, social environment, decision making, related articles.

Default Nudges: Fake Behavior Change

Here’s Why the Loop is Stupid

How behavioral science can be used to build the perfect brand

The Death Of Behavioral Economics

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

11.3: Introduction to Reinforcement Theory

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 47761

- Lumen Learning

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

What you’ll learn to do: explain reinforcement theory

In this section, you will learn about reinforcement theory, the counterpoint to goal-setting theory. Reinforcement theory is a behavioristic approach that says reinforcement conditions behavior.

Contributors and Attributions

- Introduction to Reinforcement Theory. Authored by : David J. Thompson and Lumen Learning.. License : CC BY: Attribution

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

A Review of B. F. Skinner's 'Reinforcement Theory of Motivation'

B. F. Skinner in his book Beyond Freedom and Dignity said that thinkers should make fundamental changes in human behavior, and they couldn't bring these changes only with the help of physics or biology. He believes that we only acquire the technology of behavior. Centuries ago people were seeing themselves as a person who could feel himself better any other creatures in the world. But in today " s world he is not able to understand himself. Although science have emerged vastly; but we are not able to compare anything like a science of human behavior with any other science in the world. As behaviorist B.F. Skinner brought up the Reinforcement Theory. The Reinforcement Theory is one of the oldest theories of motivation which describe behavior and how we act. This theory can called as " behaviorism " or " operant conditioning " that is taught in the today " s world of psychology. In this article we are looking at B. F. Skinner Reinforcement Theory of Motivation and we go through all details in this theory. This is a review paper based on the theorist Skinner.

RELATED PAPERS

Ezat Asgarani

Journal of the Association of Asphalt Paving …

Dr. Javed Bari

jefferson ribeiro soares

Gastroenterología y Hepatología

Javier Padillo

FEMS microbiology ecology

Taina Pennanen

Kiekberg deel 11

Jan Nillesen

Physical review. E, Statistical, nonlinear, and soft matter physics

Lukas Vlcek

Genética na Escola

Nelio Bizzo

Case Reports in Internal Medicine

Margarita Goula

Malaysian journal of nutrition

Siti Fatimah

Advanced Materials

Arvind Kumar

Manfred Strecker

BMC musculoskeletal disorders

Helle Terkildsen Maindal

Journal of Perinatal Medicine

Gloria Limón

Transportation research procedia

Thodsapon Hunsanon

Edgar Martinez

Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour

Josef Krems

Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials

Amos Sharoni

Piston: Journal of Technical Engineering

SILVIANA SIMBOLON

The Angle orthodontist

Christopher Hughes

Oguzhan Ozen

Solar Physics

Oddbjørn Engvold

Jasa Seminar Pengembangan Diri Pembelajaran

Agus Piranhamas

International Conference on Education, Information and Management

Giuliano Giova

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Find Study Materials for

- Business Studies

- Combined Science

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- English Literature

- Environmental Science

- Human Geography

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Social Studies

- Browse all subjects

- Read our Magazine

Create Study Materials

Have you ever questioned why a short break after every 20 minutes of studying can motivate you to study harder and longer? Let this explanation of reinforcement theory help you answer these questions from a psychological and scientific approach!

Explore our app and discover over 50 million learning materials for free.

- Reinforcement Theory

- Explanations

- StudySmarter AI

- Textbook Solutions

- Business Case Studies

- Business Development

- Business Operations

- Change Management

- Corporate Finance

- Financial Performance

- Boundary Spanning

- Contract of Employment

- Departmentalization

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Costs

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Rewards

- Employee Training and Development

- Employment Policy

- Expectancy Theory

- Flexible Work Arrangements

- HR Policies

- Hackman and Oldham Model

- Herzberg Two Factor Theory

- Human Resource Flow

- Human Resource Management

- Human Resource Objectives

- Improving Employer - Employee Relations

- Incentives for Employees

- Internal and External Communication

- Intrinsic Motivation

- Job Characteristics Model

- Job Satisfaction

- Labour Productivity

- Labour Turnover

- Maslow Theory

- Matrix Organizational Structure

- Methods of Recruitment

- Motivating & Engaging Employees

- Motivation in the Workplace

- Organisation Design

- Organizational Justice

- Organizational Strategy

- Organizational Structure Types

- Pay Structure

- Performance Evaluation

- Performance Feedback

- Recruitment And Selection

- Retention Rate

- Self-Efficacy Theory

- Taylor Motivation Theory

- Team Structure

- Termination

- Training Methods

- Work-Life Balance

- Influences On Business

- Intermediate Accounting

- Introduction to Business

- Managerial Economics

- Nature of Business

- Operational Management

- Organizational Behavior

- Organizational Communication

- Strategic Analysis

- Strategic Direction

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Nie wieder prokastinieren mit unseren Lernerinnerungen.

Reinforcement Theory Definition

What does reinforcement theory mean? In fact, the reinforcement theory definition is simple and intuitive.

- Reinforcement theory states that an individual's behavior is shaped by the behavior's consequences.

Essentially, the relationship between a behavior and its consequences in reinforcement theory is a cause-effect one.

For example, you choose to work hard today because you know hard work can get you more money in the future. Likewise, if you can make more money, you will likely desire to work harder.

Reinforcement Theory of Motivation

In 1957, B. F. Skinner, an American psychologist at Harvard University, proposed the reinforcement theory of motivation. 1

Behavior which is reinforced tends to be repeated; behavior which is not reinforced tends to die out or be extinguished. 1

- B. F. Skinner