- Skip to Main Content

- Media Center

Resource Library

The Demographic Transition: A Contemporary Look at a Classic Model

March 1, 2005

Population Bulletin vol 75. no.1 : An Introduction to Demography

Transitions in world population.

With the spread of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century, dramatic changes began to occur in the populations of industrializing countries. But do the changes that occurred in Western Europe and the United States have relevance for modern countries just entering the industrial age? Students should be able to evaluate and apply models to explain changes in global demographic patterns, and use their assessments to predict future needs.

- To understand the classic demographic transition (DT) model

- To explain assumptions and limitations of the classic DT model

- To construct graphs of contemporary demographic change

- To explain contemporary demographic patterns in the context of the classic DT model

Content Standards AP Human Geography*: Unit II—Population Unit B. Population growth and decline over time and space 4. Regional variations of demographic transitions

Student Activities

Activity 1: Explaining Population Change

- Activity 2: Global Population Patterns and Demographic Transitions

- Activity 3: Can an Old Model Explain New Trends?

Lesson Resources

Transitions in World Population , p. 6 and pp. 7-11 ( PDF: 320KB )

Population: A Lively Introduction, 4th edition ( PDF: 260KB ) [Note: The page numbers provided refer to the pages of the publication, not the pdf file.]

Central Concepts: Demographic transition model; birth rate; death rate; natural increase

Throughout much of history human populations have been characterized by relative stability—high birth rates and high death rates fluctuating around a low growth equilibrium. Dramatic changes followed first the Agricultural Revolution some 8,000 years ago, and later the Industrial Revolution 250 years ago, when improvements in food supply and changes in health and hygiene triggered unprecedented population growth. In the 1930s and 1940s, demographers proposed a model to explain the demographic changes observed in Western Europe between the late 18th and early 20th centuries. This model—the Demographic Transition Model—suggests a shift from high fertility/high mortality to low fertility/low mortality, with an intermediate period of rapid growth during which declining fertility rates lag behind declining mortality rates. This classic model is based on the experience of Western Europe, in particular England and Wales.

Materials Needed

- Reading: Population Handbook, 5th edition ( PDF: 463KB )

- PowerPoint or overhead transparency of The Classic Stages of Demographic Transition ( PPT: 53KB )

- Handout 1. “Data for Graphing” (provided below or Excel: 22KB )

- Graphing paper or graphing software (MS Excel)

- PowerPoint or overhead transparency of “Demographic Transition in Sweden and Mexico” or the data (found in Handout 1) for making this graph ( PPT: 65KB )

Instructions

What is “Demographic Transition”?

Before beginning this activity, assign the readings as homework.

- Explain the classic stages of demographic transition using the PowerPoint slide or overhead transparency listed above.

- Have students construct a graph of birth and death rates in England using either graph paper or graphing software (MS Excel).

- Compare the graph of England’s transition to the classic model.

- What similarities and differences can be observed?

- Discuss social and economic factors that account for the changes in population patterns over the past two centuries. [Encourage students to draw on their knowledge of world history to enrich this discussion.]

- Show a graph of demographic transition in Sweden and Mexico using the PowerPoint or overhead transparency listed above. [See alternative strategy below]

- Compare the transitions in these two countries to the classic model.

- Why are the demographic experiences of these two countries so different?

- Why did Mexico ‘s late start toward transition result in such dramatic growth?

- Is Mexico typical of countries currently undergoing transition?

- Does this mean that the classic model is no longer relevant?

Alternative Strategy: Instructions

Supply the following data and have the students construct the graph for analysis.

Activity 2: Global Population Patterns and Demographic Transitions

- World Population Data Sheet ( PDF: 304KB )

Refer to the current World Population Data Sheet by the Population Reference Bureau to answer the following questions.

How Do Demographic Characteristics Vary Among World Regions?

- Calculate the percentage (to the nearest whole number) of the world’s population expected to be living in less developed countries in 2025 and in 2050.2025: _______________ 2050: _______________

- Subtract the lowest rate from the highest rate for both crude births and deaths and enter in the chart.

- Is the difference between more developed countries and less developed countries greater for the crude birth rate or the crude death rate? Why do you think this is?

Is There Correlation Between Demographic Indicators and Economic Well-Being?

Refer again to the current World Population Data Sheet to complete the chart below:

* GNI PPP refers to gross national income converted to “international” dollars using a purchasing power parity conversion factor. International dollars indicate the amount of goods and services one could buy in the United States with a given amount of money.

- Use the data collected in the chart above to construct three simple scattergrams relating crude birth rate and GNI PPP/capita; crude death rate and GNI PPP/capita; and rate of natural increase and GNI PPP/capita. [Note: Graphs can be constructed either manually on graph paper or electronically using a software program such as MS Excel.]

- In general, what is the relationship between each indicator and GNI PPP/capita? Phrase your response in the form of three generalizations. [for example, “the higher the CBR, the…the GNI PPP/capita”]

- Identify countries that are outliers in each graph. How do you account for each country’s deviation from the general trend? [Note: This may require some research.]

Based on the data collected in the final chart above, speculate in which stage of the classic demographic transition model each of these countries would fall.

- Which characteristics are most helpful in making decisions?

- What additional information would be useful?

- Refer to the World Population Data Sheet to gather more information to support an informed decision.

- How does the model assist in categorizing countries? What are some limitations?

Activity 3: Can an Old Model Explain New Trends?

Introduction

The classic Demographic Transition Model is based on the experience of Western Europe, in particular England and Wales. Critics of the model argue that “demographic transition” is a European phenomenon and not necessarily relevant to the experience of other regions, especially those regions referred to as “less developed” or “developing.”

The underlying premise of the classic Demographic Transition Model is that all countries will eventually pass through all four stages of the transition, just as the countries of Europe did. Because the countries of Europe, as well as the United States, have achieved economic success and enjoy generally high standards of living, completion of the demographic transition has come to be associated with socioeconomic progress.

This raises several questions:

- Can contemporary less developed countries hope to achieve either the demographic transition or the economic progress enjoyed by more developed countries that passed through the transition at a different time and under different circumstances?

- Is the socioeconomic change experienced by industrialized countries a prerequisite or a consequence of demographic transition?

Part One: Does the Classic Demographic Transition Model Provide a Useful Framework for Evaluating Demographic Change in Contemporary Developing Countries?

- Reading: Transitions in World Population , p. 6 and pp. 7-11 ( PDF: 320KB )

- Handout 1. “Data Tables” ( PDF: 11KB )

- Graphing paper or graphing software such as MS Excel

- Internet access for basic research

Assign the reading above before conducting this activity.

- Review the classic Demographic Transition Model. Discuss some criticisms of its relevance to countries only now experiencing demographic change.

- Ask students if the classic model has a place in contemporary population analysis, and explain that they will test the model in this activity.

- Divide the class into four (or more—see note below) groups. Assign each group one of the countries for which data is provided in Handout 1.

- Have students construct a graph showing the trends in birth and death rates and population growth.

- Direct students to use an Internet search engine to locate additional information about population trends in the assigned country.

[Note: Data for additional countries can be found in the U.S. Census Bureau International Data Base ]

Part Two: Is the Demographic Transition Model Useful as a Framework for Evaluating Demographic Change?

- PowerPoint or overhead transparency of “A Model” ( PPT: 39KB )

- When students have completed their graphs and research, have each group report back to the class.

- Now return to the original questions to discuss the classic Demographic Transition Model.

- Is the Demographic Transition Model useful as a framework for evaluating demographic change in regions outside Europe and the United States?

- Is it necessary that all countries share the experiences of Europe and the United States in order to pass through a demographic transition?

- Is the socioeconomic change experienced by industrialized countries a prerequisite or a consequence of demographic transition?

- Are there multiple ways to achieve a similar end?

This lesson plan is part of a teaching package, Making Population Real: New Lesson Plans and Classroom Activities .

* AP and the Advanced Placement Program are registered trademarks of the College Entrance Examination Board, which was not involved in the production of these lesson plans.

Demographic Studies

Glossary of Demographic Terms

Data 101 Tutorials on the American Community Survey

Population Handbook

Demographic transition: Why is rapid population growth a temporary phenomenon?

Death rates fall first, then fertility rates, and this leads to a slowdown of population growth..

Population growth is determined by births and deaths. Every country has seen very substantial changes in both: mortality and fertility rates have fallen across the world.

But declining mortality rates and declining fertility rates alone do not explain why populations grow. If these changes happened at the same time, the size of the population would not increase. What is crucial is the timing at which mortality and fertility changes.

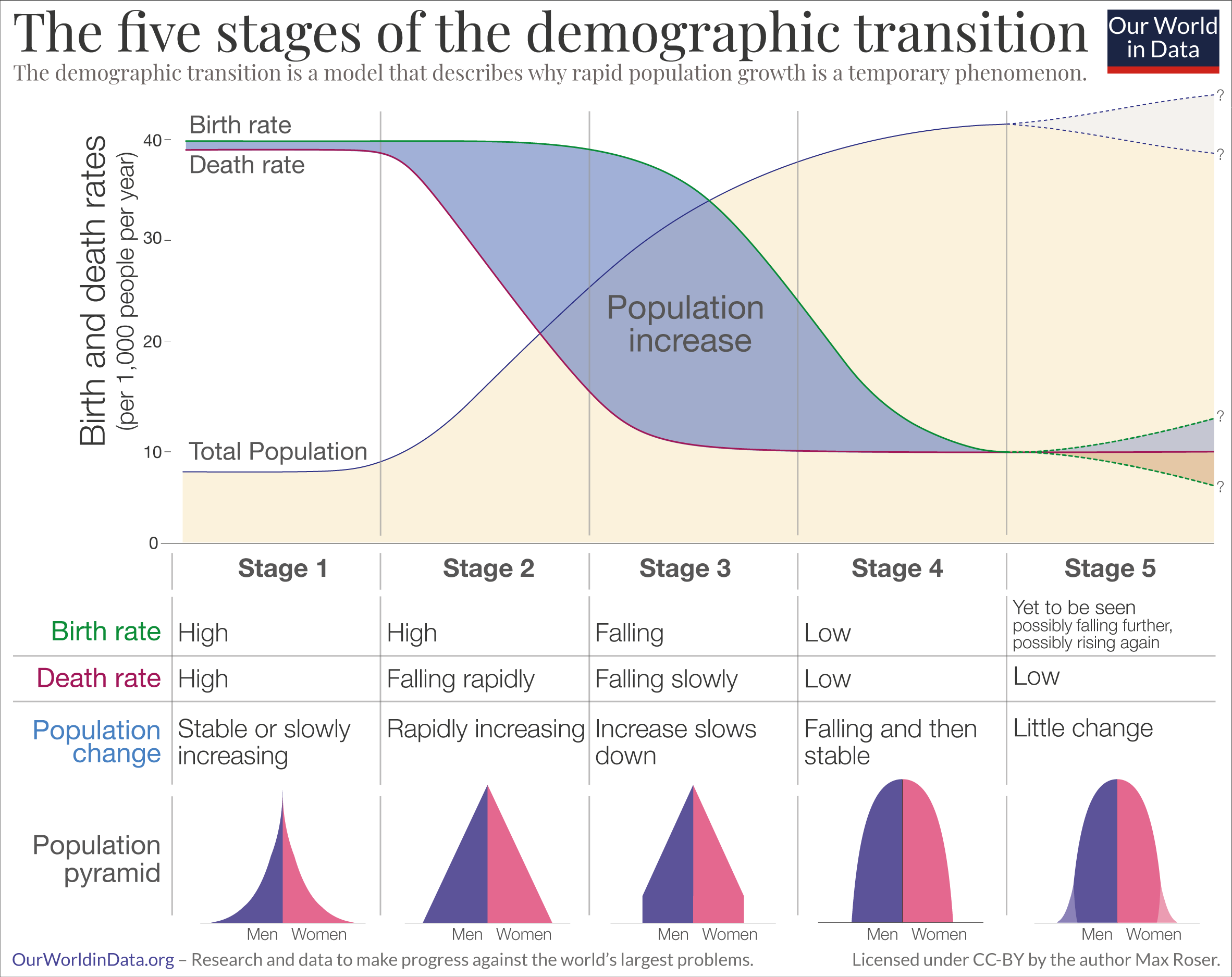

The model that explains why countries go through a period of rapid population growth is called the ‘demographic transition’. It is shown in the schematic figure. It is a beautifully simple model that describes the observed pattern in countries around the world and is one of the great insights of demography. 1

As the graphic below shows, the demographic transition is a sequence of five stages:

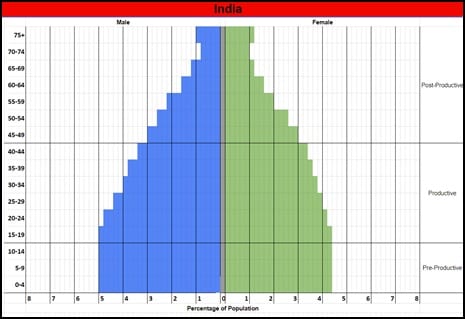

- Stage 1 – high mortality and high birth rates : In the past birth rates were high, but since the mortality rates were also high we observe no or only very small population growth. This describes the reality through most of our history. Societies around the world remained in stage 1 for many millennia as the long-run data on extremely slow population growth makes clear. At this stage the population pyramid is broad at the base as many children are born. But since the mortality rate is high across all ages – and in particular for children – the pyramid gets much narrower towards the top.

- Stage 2 – mortality falls, but birth rates are still high: In the second phase the health of the population slowly starts to improve and the mortality rate starts to fall. Since the health of the population has already improved, but fertility still remains as high as before, this is the stage of the transition at which the size of the population starts to grow rapidly. Historically it is the exceptional time at which the extended family with many (surviving) children is common.

- Stage 3 – mortality is low and birth rates begin to fall: At this stage the birth rate starts to fall and as a consequence the rate at which the population grows begins to decline as well. In our topic page on fertility rates we discuss in detail why fertility rates declined. But to summarize the main points: When the mortality of children is not as high as it once was, parents adapt to the healthier environment and choose to have fewer children; the economy is undergoing structural changes that makes children less economically valuable; and as women gain more power within society and within partnerships they tend on average to have fewer children than before.

- Stage 4 – mortality and birth rates are low: Rapid population growth comes to an end in stage 4. At this stage the birth rate falls to a similar level as the already low mortality rate. The population pyramid is now box shaped; as the mortality rate at young ages is now very low the younger cohorts are now very similar in size and only at an old age the size of cohorts get smaller rapidly.

- Stage 5 – the future of population growth will be determined by what is happening to fertility rates: The demographic transition describes changes over the course of socio-economic modernization. What happens at a very high level of development is not a question we can answer with certainty since only few societies have reached this stage. If fertility rates are rising again at very high levels of development — as the research by demographers Mikko Myrskylä, Hans-Peter Kohler, and Francesco Billari suggests — then population sizes might stabilize or even increase. However if the fertility rate stays below 2 children per woman then we will see a decline of the population size in the long run.

Empirical evidence for the demographic transition

Rapid population growth is a temporary phenomenon.

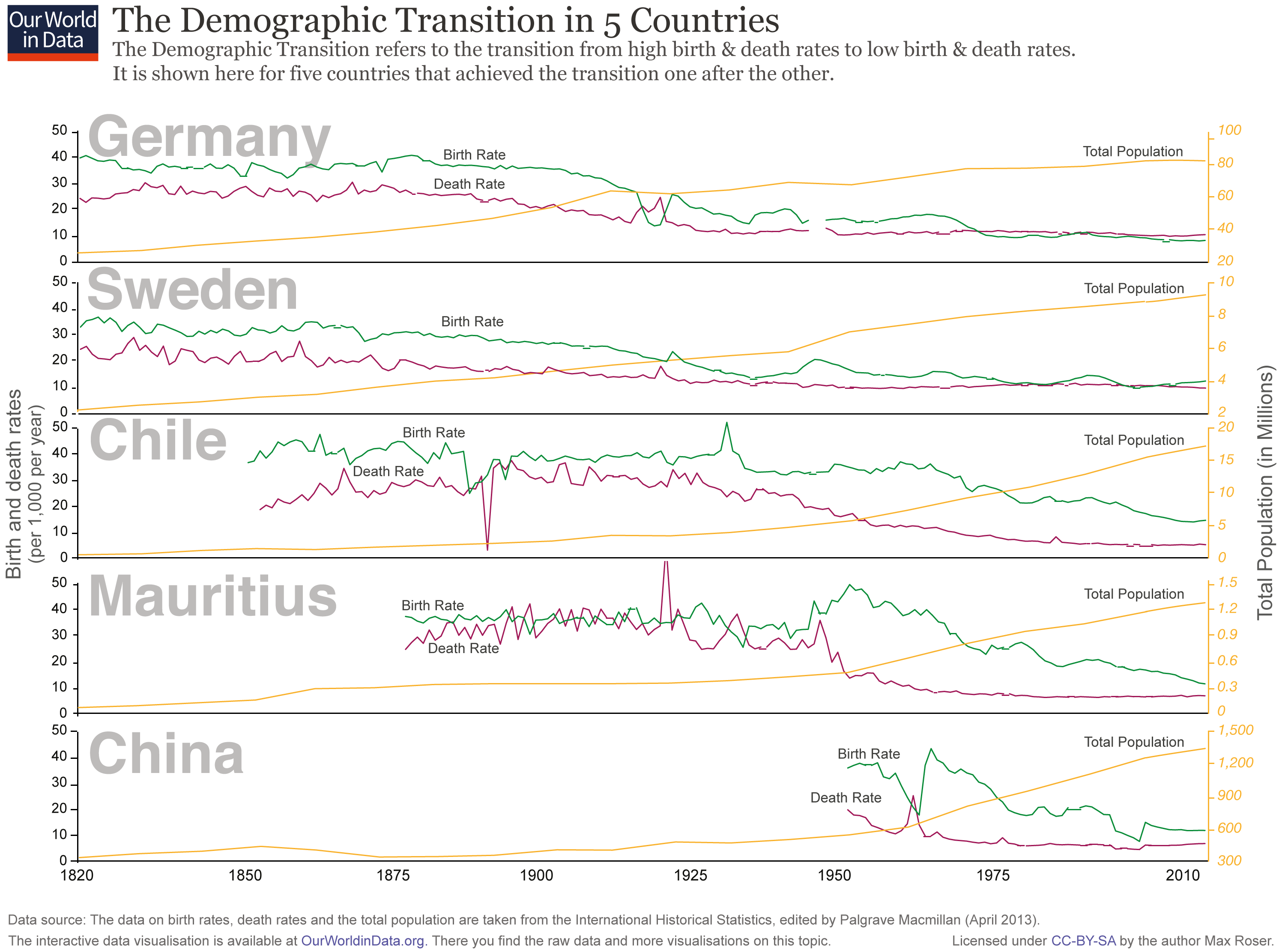

If fertility fell in lockstep with mortality we would not have seen an increase in the population at all. The demographic transition works through the asynchronous timing of the two fundamental demographic changes: The decline in the death rate is followed by the decline in birth rates.

This decline in the death rate followed by a decline in the birth rate is something we observe with great regularity and is largely independent of the culture or religion of the population.

The chart presents the empirical evidence for the demographic transition for five very different countries in Europe, Latin America, Africa, and Asia. In all countries, we observed the pattern described by the demographic transition, first a decline in mortality that starts the population boom and then a decline in fertility which brings the population boom to an end. The population boom is a temporary event.

In the past, the size of the population was stagnant because of high mortality. Now country after country are moving into a world in which the population is stagnant because of low fertility.

England and Wales’s demographic transition

Perhaps the longest available view of the demographic transition comes from data for England and Wales.

In 1981, Anthony Wrigley and Roger Schofield published a major research project analyzing English parish registers—a unique source that allowed them to trace demographic changes for the three centuries prior to state records. 2

According to the researchers, “England is exceptionally fortunate in having several thousand parish registers that begin before 1600”; collectively, with their early start and breadth of coverage, these registers form an excellent resource. As far as we know, there is no comparable data for any other country over such a long period.

The chart shows the birth and death rates in England and Wales over the span of nearly 500 years. It stitches together Wrigley and Schofield’s data for the years from 1541 to 1861 with two other sources up to 2015.

As we can see, a growing gap opens up between the birth and death rate after 1750. During this period the population begins to increase rapidly in size. Around the 1870s, we begin to see the third stage of the demographic transition. As the birth rate starts to follow the death rate’s decline, that gap between the two starts to shrink, slowing down the rate of population growth.

Sweden’s demographic transition

In the next visualization we take a closer look at Sweden’s demographic transition. The country’s long history of population recordkeeping – starting in 1749 with their original statistical office, ‘the Tabellverket’ (Office of Tables) – makes it a particularly interesting case study of the mechanisms driving population change.

Statistics Sweden, the successor of the Tabellverket, has published data on both deaths and births since record keeping began more than 250 years ago. These records suggest that around the year 1800, the Swedish death rate started falling, mainly due to improvements in health and living standards, especially for children. 3

Yet while death rates were falling, birth rates remained at a constant pre-modern level until the 1860s. During this period and up until the first half of the 20th century, there was a sustained gap between the frequency of deaths and the frequency of births. It was because of this gap that the Swedish population increased.

Demographic transitions across the world

Today, different countries find themselves in different stages of the demographic transition. In the chart we see birth rates plotted against death rates: the two variables that determine the demographic transition.

Most high-income countries have reached stage four and have low birth and death rates.

For a history and literature review of the theory’s development, see: Kirk, Dudley. “ Demographic transition theory .” Population studies 50.3 (1996): 361-387.

Wrigley, E. A., Schofield, R. S., & Schofield, R. (1989). The population history of England 1541-1871. Cambridge University Press.

Before 1800 more than 20% of Swedish babies died before they reached their first birthday, and of those who survived, another 20% died before their 10th birthday (see Croix, Lindh, and Malmberg (2009), Demographic change and economic growth in Sweden: 1750–2050 . In Journal of Macroeconomics, 31, 1, 132–148).

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

BibTeX citation

Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license . You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

17.2E: Demographic Transition Theory

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 8491

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Break down the demographic transition model/theory into five recognizable stages based on how countries reach industrialization

Whether you believe that we are headed for environmental disaster and the end of human existence as we know it, or you think people will always adapt to changing circumstances, we can see clear patterns in population growth. Societies develop along a predictable continuum as they evolve from unindustrialized to postindustrial. Demographic transition theory (Caldwell and Caldwell 2006) suggests that future population growth will develop along a predictable four- or five-stage model.

In stage one, pre-industrial society, death rates and birth rates are high and roughly in balance. An example of this stage is the United States in the 1800s. All human populations are believed to have had this balance until the late 18th century, when this balance ended in Western Europe. In fact, growth rates were less than 0.05% at least since the Agricultural Revolution over 10,000 years ago.

Population growth is typically very slow in this stage, because the society is constrained by the available food supply; therefore, unless the society develops new technologies to increase food production (e.g. discovers new sources of food or achieves higher crop yields), any fluctuations in birth rates are soon matched by death rates.

In stage two, that of a developing country, the death rates drop rapidly due to improvements in food supply and sanitation, which increase life spans and reduce disease. Afghanistan is currently in this stage.

The improvements specific to food supply typically include selective breeding and crop rotation and farming techniques. Other improvements generally include access to technology, basic healthcare, and education. For example, numerous improvements in public health reduce mortality, especially childhood mortality. Prior to the mid-20th century, these improvements in public health were primarily in the areas of food handling, water supply, sewage, and personal hygiene. Another variable often cited is the increase in female literacy combined with public health education programs which emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In Europe, the death rate decline started in the late 18th century in northwestern Europe and spread to the south and east over approximately the next 100 years. Without a corresponding fall in birth rates this produces an imbalance, and the countries in this stage experience a large increase in population.

In stage three, birth rates fall. Mexico’s population is at this stage. Birth rates decrease due to various fertility factors such as access to contraception, increases in wages, urbanization, a reduction in subsistence agriculture, an increase in the status and education of women, a reduction in the value of children’s work, an increase in parental investment in the education of children and other social changes. Population growth begins to level off. The birth rate decline in developed countries started in the late 19th century in northern Europe.

While improvements in contraception do play a role in birth rate decline, it should be noted that contraceptives were not generally available nor widely used in the 19th century and as a result likely did not play a significant role in the decline then.

It is important to note that birth rate decline is caused also by a transition in values; not just because of the availability of contraceptives.

During stage four there are both low birth rates and low death rates. Birth rates may drop to well below replacement level as has happened in countries like Germany, Italy, and Japan, leading to a shrinking population, a threat to many industries that rely on population growth. Sweden is considered to currently be in Stage 4. As the large group born during stage two ages, it creates an economic burden on the shrinking working population. Death rates may remain consistently low or increase slightly due to increases in lifestyle diseases due to low exercise levels and high obesity and an aging population in developed countries. By the late 20th century, birth rates and death rates in developed countries leveled off at lower rates.

Stage 5 (Debated)

Some scholars delineate a separate fifth stage of below-replacement fertility levels. Others hypothesize a different stage five involving an increase in fertility. The United Nations Population Fund (2008) categorizes nations as high-fertility, intermediate-fertility, or low-fertility. The United Nations (UN) anticipates the population growth will triple between 2011 and 2100 in high-fertility countries, which are currently concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa. For countries with intermediate fertility rates (the United States, India, and Mexico all fall into this category), growth is expected to be about 26 percent. And low-fertility countries like China, Australia, and most of Europe will actually see population declines of approximately 20 percent.

Conclusions

As with all models, this is an idealized picture of population change in these countries. The model is a generalization that applies to these countries as a group and may not accurately describe all individual cases. The extent to which it applies to less-developed societies today remains to be seen. Many countries such as China, Brazil and Thailand have passed through the Demographic Transition Model (DTM) very quickly due to fast social and economic change. Some countries, particularly African countries, appear to be stalled in the second stage due to stagnant development and the effect of AIDS.

- Demographic transition theory suggests that populations grow along a predictable five-stage model.

- In stage 1, pre-industrial society, death rates and birth rates are high and roughly in balance, and population growth is typically very slow and constrained by the available food supply.

- In stage 2, that of a developing country, the death rates drop rapidly due to improvements in food supply and sanitation, which increase life spans and reduce disease.

- In stage 3, birth rates fall due to access to contraception, increases in wages, urbanization, increase in the status and education of women, and increase in investment in education. Population growth begins to level off.

- In stage 4, birth rates and death rates are both low. The large group born during stage two ages and creates an economic burden on the shrinking working population.

- In stage 5 (only some theorists acknowledge this stage—others recognize only four), fertility rates transition to either below-replacement or above-replacement.

- demographic transition theory : Describes four stages of population growth, following patterns that connect birth and death rates with stages of industrial development.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

- Curation and Revision. Provided by : Boundless.com. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SPECIFIC ATTRIBUTION

- Introduction to Sociology/Demography. Provided by : Wikibooks. Located at : en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Introduction_to_Sociology/Demography%23Population_Growth_and_Overpopulation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by : Boundless Learning. Located at : www.boundless.com//sociology/definition/replacement-level . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- carrying capacity. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/carrying_capacity . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- fertility rate. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/fertility_rate . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Slums. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Slums . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Demography. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Demography%23Basic_equation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by : Boundless Learning. Located at : www.boundless.com//sociology/definition/natural-increase . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- demography. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/demography . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Net migration. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Net%20migration . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- mortality rate. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/mortality_rate . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Us population. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Us_population . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Introduction to Sociology/Demography. Provided by : Wikibooks. Located at : en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Introduction_to_Sociology/Demography%23Early_Projections_of_Overpopulation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- World population. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/World_population%23Forecasts . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Projections of population growth. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Projections_of_population_growth . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Overpopulation. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Overpopulation%23Mitigation_measures . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Birth rates. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Birth%20rates . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- forecast. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/forecast . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Green Revolution. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Green%20Revolution . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Green Revolution. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Green_Revolution . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Population Growth Forecasts. Located at : www.youtube.com/watch?v=b98JmQ0Cc3k . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright . License Terms : Standard YouTube license

- exponential growth. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/exponential_growth . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Demography and Population. March 15, 2015. Provided by : OpenStax CNX. Located at : http://cnx.org/contents/2cf134f9-f88e-4590-8c33-404ead13ab83@3 . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Boundless. Provided by : Boundless Learning. Located at : www.boundless.com//sociology/...n-catastrophes . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Overpopulation. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Overpopulation . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Introduction to Sociology/Demography. Provided by : Wikibooks. Located at : en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Introdu...hic_Transition . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- OpenStax, Demography and Population. February 19, 2015. Provided by : OpenStax CNX. Located at : https://cnx.org/contents/LPE0-fiO@2/Demography-and-Population . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Demographic transition. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographic_transition#Summary_of_the_theory . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Population Growth Forecasts. Located at : http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b98JmQ0Cc3k . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright . License Terms : Standard YouTube license

- Demographic-TransitionOWID.png. Provided by : Wikimedia. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/F...sitionOWID.png . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Demographic Transition Theories

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2022

- pp 1389–1393

- Cite this reference work entry

- Luoman Bao 3

239 Accesses

Population transition theories ; Fertility transition theories

The theory of the demographic transition describes changes in population trends from high mortality and fertility to low mortality and fertility rates and provides explanations for the transition from economic, social, cultural, and historical perspectives. During the demographic transition, a population changes in size, age structure, and the momentum of growth. The demographic transition theory informs the process of population aging because it discusses two crucial demographic processes, fertility and mortality, that alter the proportion of young and older people in a population. The theory indicates that when a population has completed the demographic transition, the proportion of older people increases and the population grows older.

The demographic transition is “the eternal theme in demography” (Caldwell 1996 , p. 321). Scholars generally believe that, although with forerunners, the...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Angeles L (2010) Demographic transitions: analyzing the effects of mortality on fertility. J Popul Econ 23(1): 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-009-0255-6

Article Google Scholar

Bianchi SM (2014) A demographic perspective on family change. J Fam Theory Rev 6(1):35–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12029

Blue L, Espenshade TJ (2011) Population momentum across the demographic transition. Popul Dev Rev 37(4):721–747. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4002.BONE

Caldwell JC (1976) Toward a restatement of demographic transition theory. Popul Dev Rev 2(3/4):321–366. https://doi.org/10.2307/1971615

Caldwell JC (1996) Demography and social science. Popul Stud 50(3):305–333

Google Scholar

Colby SL, Ortman JM (2015) Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population: 2014 to 2060. Current population reports, P25-1143. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf

Coleman D (2006) Immigration and ethnic change in low-fertility countries: a third demographic transition. Popul Dev Rev 32(3):401–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2006.00131.x

Dyson T (2001) A partial theory of world development: the neglected role of the demographic transition in the shaping of modern society. Int J Popul Geogr 7(2):67–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijpg.215

Dyson T (2011) The role of the demographic transition in the process of urbanization. Popul Dev Rev 37(Suppl):34–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00377.x

Galor O (2012) The demographic transition: causes and consequences. Cliometrica 6(1):1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-011-0062-7

Grieco EM, Trevelyan E, Larsen L, Acosta YD, Gambino C, de la Cruz P, … Walters N (2012) The size, place of birth, and geographic distribution of the foreign-born population in the United States: 1960 to 2010. Population Division working paper, 96. U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2012/demo/POP-twps0096.pdf

He W, Goodkind D, Kowal P (2016) An aging world: 2015, U.S. Census Bureau international population reports. U.S. Government Piblishing Office, Washington, DC

Kirk D (1996) Demographic transition theory. Popul Stud 50(3):361–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/0032472031000149536

Lam D (2011) How the world survived the population bomb: lessons from 50 years of extraordinary demographic history. Demography 48(4):1231–1262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-011-0070-z

Lesthaeghe R (2010) The unfolding story of the second demographic transition. Popul Dev Rev 36(2): 211–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00328.x

Lesthaeghe R (2014) The second demographic transition: a concise overview of its development. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111(51):18112–18115. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1420441111

Murtin F (2013) Long-term determinants of the demographic transition, 1870–2000. Rev Econ Stat 95(2):617–631. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00302

Rowland DT (2003) Demographic methods and concepts. Oxford University Press, New York

Thornton A, Binstock G, Yount KM, Abbasi-Shavazi MJ, Ghimire D, Xie Y (2012) International fertility change: new data and insights from the developmental idealism framework. Demography 49(2):677–698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0097-9

Weeks JR (2016) Population: an introduction to concepts and issues, 12th edn. Cengage Learning, Boston

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Sociology, California State University, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Luoman Bao .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Population Division, Department of Economics and Social Affairs, United Nations, New York, NY, USA

Department of Population Health Sciences, Department of Sociology, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA

Matthew E. Dupre

Section Editor information

The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong, China

Yuying Tong

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Bao, L. (2021). Demographic Transition Theories. In: Gu, D., Dupre, M.E. (eds) Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22009-9_655

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22009-9_655

Published : 24 May 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-22008-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-22009-9

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- History & Overview

- Meet Our Team

- Program FAQs

- Social Studies

- Language Arts

- Distance Learning

- Population Pyramids

- World Population “dot” Video

- Student Video Contest

- Lower Elementary (K-2)

- Upper Elementary (3-5)

- Middle School (6-8)

- High School (9-12)

- Browse all Resources

- Content Focus by Grade

- Standards Matches by State

- Infographics

- Articles, Factsheets & Book Lists

- Population Background Info

- Upcoming Online Workshops

- On-Demand Webinar Library

- Online Graduate Course

- Request an Online or In-person Workshop

- About Teachers Workshops

- About Online Teacher Workshops

- Pre-Service Workshops for University Classes

- In-Service Workshops for Teachers

- Workshops for Nonformal Educators

- Where We’ve Worked

- About the Network

- Trainer Spotlight

- Trainers Network FAQ

- Becoming a Trainer

- Annual Leadership Institutes

- Application

Classroom Activities for Teaching About Population Growth: Webinar Recap

Free easy-to-use lesson plans for virtual, blended, or in-person classrooms.

By Lindsey Bailey | October 16, 2020

Why populations grow is one of the most foundational questions when considering environmental and social issues, and earlier this month, we held a webinar to support educators in teaching this important demographic concept. A fantastic group of 74 teachers joined us, and we had the opportunity to share lesson plans and tools that can be used in both face-to-face and virtual classrooms. In case you missed it, here’s a quick recap of what we covered (with links to all the shared materials!).

Three Lesson Plans (with Virtual Adaptations) for Teaching Why Populations Grow

In this post, we’ll summarize the easy-to-use lessons that we shared for teaching about why populations grow and will explain how to adapt the lessons for a virtual classroom. Digital adaptations are made using Google Sheets and Google Slides and we will provide links for you to copy, use, and share with your own students. We also recorded the webinar, and encourage you to check it out – watch the webinar now !

A Visual Demonstration of the Relationship Between Birth and Death Rates

The lesson Stork and the Grim Reaper is a powerful visual, showing how birth rates and death rates interact to influence the rate of population growth. The lesson is a demonstration using two bowls of water. One bowl should be transparent (a glass or plastic Tupperware container works well) and represents planet Earth; the water inside this bowl represents our global population (it can be helpful to use blue food coloring to make the water more visible). The second bowl should be opaque so students do not see, or focus on, the water in it.

To prepare the demonstration, you will need two student volunteers, one to represent the global birth rate and one to represent the global death rate. Give the student representing birth rate the “Stork” necklace and a 1 cup measure, and the student representing the death rate the “Grim Reaper” necklace a ⅓ cup measure. (Currently, the global death rate is approximately one-third of the global birth rate.)

To start the demonstration, have the Stork add one scooper (1 cup) of water to the bowl representing our planet, symbolizing people being born, or added, to our global population. Then, have the Grim Reaper remove a scooper (1/3 cup) from the same bowl, representing people dying. The Stork and the Grim Reaper continue in turn while students observe what happens to the blue water that represents population. Students will see that because the birth rate is so much higher than the death rate (the scooper is so much larger) the water continues to rise.

Since this lesson is a demonstration, it can be done easily through a live video share in a virtual setting. To extend the lesson, try finding the birth and death rate equivalents for different countries around the world and comparing countries based on their rate of growth (or lack of growth).

Analyzing the Impact of Age-Structure Using Population Pyramids

Population Pyramids are a foundational tool for investigating population age-structures and therefore, growth patterns. In Power of the Pyramids , students are tasked with creating population pyramids for an assigned country, using provided age-sex data. The lesson provides data for six different countries – China, India, Guatemala, U.S., Nigeria, and Germany – and we recommend having pairs of students graph different countries.

Once all the graphs are completed, have each group share out, and save lots of time for analysis and discussion! Students will notice that the graphs look very different: some triangular, some more rectangular, and one (Germany) an inverse triangle. Using critical thinking, students can discuss which countries are experiencing the fastest and slowest rates of population growth, based on their pyramid shape. HINT! Countries with more triangular shaped pyramids are growing the fastest since the majority of the population is either currently in, or almost in, their reproductive years, and younger cohorts are larger than those above them on the pyramid.

To do this population pyramid lesson digitally , have students use our Google Sheet to complete their graphing. Each tab of the Sheet has data for a different country, and students use the “paint bucket” tool to fill in bars on a pre-made graph template. Once graphing is complete, students can flip between completed country graphs to see the diversity of shapes and discuss implications.

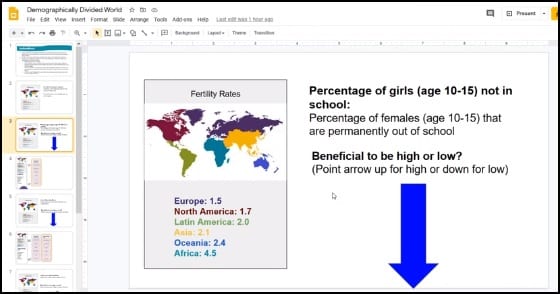

Investigating How Societal Factors Impact Fertility Rates

There are many social and economic factors that impact fertility rates around the world. The lesson Demographically Divided World explores these factors and asks students to consider the validity of the Demographic Transition Model (DTM) and how it applies to certain countries.

After reviewing the map overlays of fertility and life expectancy data found on the interactive site www.worldpopulationhistory.org , six students take on the role of regional representatives to share statistics on factors that impact fertility rates. Standing at the front of the classroom, each regional representative shares their region’s total fertility rate with the class. Next, representatives read statistics for four factors that impact fertility: percent of girls not in school, infant mortality rate, adolescent fertility rate, and percent of female contraceptive use. For each factor, the following sequence is repeated: regional representatives read their statistic to the class, the class discusses how and why the factor impacts fertility rates, students determine whether a higher number or lower is more ideal for lowering fertility rates, then regional representatives line up in order of least ideal to most ideal. Students take note of the orders of the regions, brainstorm other factors that influence fertility, and discuss variations in fertility within each region.

For the remainder of the lesson, students analyze the Demographic Transition Model, first learning about the model by using a data visualization from Gapminder.org and then researching an assigned country to determine where it falls within the DTM.

The first, third, and fourth parts of the lesson are already easily done in a virtual format, since they are completed using web based tools or independent research. To complete Part 2 of the lesson (where students are regional representatives), share this Google Slide deck with your students, along with the Region Cards. The six regional representatives will read statistics from their cards, and the class can discuss the statistics just as they would in person. Rather than lining up in the classroom from most to least ideal in terms of lowering fertility, a volunteer will slide the region tiles on the Slides into the correct order for each factor. To review the concept of the DTM, try this interactive tool using a Google Slide where students slide DTM characteristics into columns for the appropriate DTM stage.

More Resources for Teaching About Population Growth

Here at PopEd we’ve been focusing on why populations grow for the past two months and have been sharing lots of helpful lesson plans, tools, and resources. To find everything we’ve shared so far, follow us on Facebook , Twitter , or Instagram and search the hashtag #PopEdWhyPopulationsGrow. Let us help make teaching this important topic easier, more fun, and engaging despite this new virtual world!

About Population Education

Population Education provides K-12 teachers with innovative, hands-on lesson plans and professional development to teach about human population growth and its effects on the environment and human well-being. PopEd is a program of Population Connection. Learn More About PopEd .

Privacy Overview

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

THE SECOND DEMOGRAPHIC TRANSITION THEORY: A Review and Appraisal

Batool zaidi.

PhD candidate, Sociology Department, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

S. Philip Morgan

Alan Feduccia Professor, Sociology Department and Director, Carolina Population Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

References to the second demographic transition (SDT) concept/theoretical framework have increased dramatically in the last two decades. The SDT predicts unilinear change toward very low fertility and a diversity of union and family types. The primary driver of these changes is a powerful, inevitable and irreversible shift in attitudes and norms in the direction of greater individual freedom and self-actualization. First, we describe the origin of this framework and its evolution over time. Second, we review the empirical fit of the framework to major changes in demographic and family behavior in the U.S., the West, and beyond. As has been the case for other unilinear, developmental theories of demographic/family change, the SDT failed to predict many contemporary patterns of change/difference. Finally, we review previous critiques and identify fundamental weaknesses of this perspective, and provide brief comparisons to selected alternative approaches.

I. INTRODUCTION

The demographic transition, i.e., the transition from high to low death and birth rates, absorbed demographers’ attention for much of the second half of the 20 th Century. This empirical and theoretical attention produced an impressive set of mechanisms that together provide a compelling explanation for the decline in vital rates (see Casterline 2003 ; Bongaarts and Watkins 1996 ). However, for understanding fertility changes within already low-fertility populations, the demographic transition literature offers little. Building on and against this classical tradition, the framework of a “second demographic transition” (SDT) has become a population researcher’s “go-to” concept/theoretical framework for studying family/fertility change in contemporary Europe as well as the Western world more broadly (see for example Bianchi 2014 ; Sobotka 2008 ; McLanahan 2004 ). It is now also being proposed for understanding family change in Asian and Latin American countries ( Esteve et al 2012 ; Esteve et al 2012b ; McDonald 2009 ; Atoh et al 2004 ).

The second demographic transition entails “sustained sub-replacement fertility, a multitude of living arrangements other than marriage, the disconnection between marriage and procreation, and no stationary population” ( Lesthaeghe and Surkyn 2008 , pp.82; Lesthaeghe 2010 , pp. 211; Lesthaeghe 2014 , pp 18112). The primary driver of these trends is the cultural shift toward postmodern attitudes and norms (i.e., those stressing individuality and self-actualization) ( van de Kaa 2001 ). At the macro level the SDT provides a view of how societies evolve over time, stressing the role of ideational change in bringing about a package of demographic/family behaviors. At the individual level, the SDT framework offers individuals’ value orientations as the principal determinants of persons’ fertility and family behavior.

Originally proposed in 1986 by two European demographers, Ron Lesthaeghe and Dirk van de Kaa, the SDT framework/theory/concept (used in multiple ways in the literature) gained considerable traction in the 1990s ( Billari and Liefbroer 2004 ). By the turn of the century it had become “the theory of the decade…that launched a thousand research projects” ( Coleman 2004 , pp. 11). Figure 1 (right axis) shows the increase in peer-reviewed articles in the social science journals that mention “second demographic transition” in their text. Google Scholar data (left axis), that includes books and reports, provide many more citations and shows a similar, dramatic, upward climb.

Citations to the Second Demographic Transition (SDT): Peer-reviewed publications and Google Scholar cites

This review’s next section focuses on the content and scope of the SDT, and how they have evolved over time. The subsequent section assesses the fit of empirical evidence with the SDT. The final section reviews criticisms aimed at the SDT and briefly discusses some alternative approaches. We conclude with an appraisal that raises concerns about this widely used perspective. Specifically, the SDT clings to a problematic developmental perspective and as an inevitable result is inconsistent with important features of family and fertility in developed country contexts.

II. THE SECOND DEMOGRAPHIC TRANSITION

A. original statements.

Lesthaeghe and van de Kaa coined the term ‘second transition’ in 1986 ; the phrase appeared in the title of the introductory chapter of a special volume (published in Dutch) on the demographic situation in low fertility countries ( Lesthaeghe and van de Kaa 1986 ). Initially, Lesthaeghe and van de Kaa offered the second transition as a possible phenomenon (SDT was followed by a question mark in the title of the chapter). A year later, the Population Reference Bureau commissioned van de Kaa to write a bulletin on the demographic situation in Europe and van de Kaa titled this piece Europe’s Second Demographic Transition ( van de Kaa 1987 ). This bulletin became the seminal and most cited work on SDT; according to Google (accessed on 7.21.16) it has been cited 2270 times.

Examining demographic change in 30 European countries, van de Kaa (1987 , pp.5) argued that “the principal demographic feature of this second transition is the decline in fertility from somewhat above the ‘replacement’ level of 2.1 births per woman…to a level well below replacement.” The driving force behind this transition was ideational change -- a dramatic shift from altruistic to individualistic norms and attitudes ( van de Kaa, 1987 , pp. 5; van de Kaa 2002 , pp.5)

According to van de Kaa (1987) , the second demographic transition began in Europe after World War II. He argued that the war led to an increase in premarital intercourse and the age at first sexual intercourse declined in the postwar period. However, social attitudes were slower to change and marriage was still required for legitimacy and acceptability of sexual relations. As a result the age at marriage declined during this period. The improvement in socio-economic conditions after the war made children more affordable and thus fertility rates also increased up until the 1960s (pp.10).

Van de Kaa (1987 , pp. 10–11) proposed that early marriages loosened the temporal link between marriage and childbearing, as young married couples waited to have children until they were financially ready. Advances in contraceptive technology, with the introduction of the pill and IUD, further weakened the link between the two. The rise in divorce and separation along with the decoupling of sexual relationships and procreation led to a decline in marriage rates and an increase in cohabitation. After initially persisting, the pressure to marry by the time of first birth gave way as well (i.e., nonmarital fertility rose). Marriage (and consensual unions) no longer primarily reflected the desire for children and fertility rates declined well below replacement levels.

This is the “standard” sequence of events during the SDT ( van de Kaa 1987 , pp.11). van de Kaa (1987) acknowledged that changes in family formation in all 30 countries would not evolve according to this ‘standard’ sequence, but they would all experience the four basic features of the transition to below replacement fertility, and could be grouped according to where they were in the sequence (see Table 1 , column 1). Three of these features were related to changes in family formation and structure, and one captures the shift in contraceptive use (from preventive to self-fulfilling). Van de Kaa (1987 , pp.9) argued that while the timing and speed of the sequence of this second transition could differ substantially, there was still evidence of “logical ordering”.

Key aspects/phases of the SDT and recent elaborations

Lesthaeghe’s (1995) chapter “The Second Demographic Transition in Western Countries: An Interpretation”, which is the second most cited work on the SDT, with 1188 citations (Google scholar as of 07.21.16), built on van de Kaa’s description by further codifying the features of SDT and their sequence into three phases (see Table 1 , column 2). In a more recent statement, Lesthaeghe (2010 , cited 547 times, Google Scholar 8/1/2016) elaborates the SDT in response to conflicting empirical evidence and a set of criticisms by his peers. We return to this evidence and criticism below, but Lesthaeghe (2010) acknowledged different rates of social and demographic change and some variation in developmental paths. He also allowed for some heterogeneity in the end stage. However, he does so without removing the SDT’s fundamental developmental character – a feature we critique in our concluding appraisal.

B. The (first) demographic transition

For some readers, a discussion of the second demographic transition (SDT) begs for a description of, and links to, the first. As noted at the outset, the (first) demographic transition (DT) refers to the decline of fertility and mortality from high levels to low levels, with an intervening period of rapid population growth caused by an earlier and more rapid decline in mortality (than fertility). According to early statements of the demographic transition theory, the driver of these changes was industrialization (and associated social and economic development, i.e., modernization) that both increased children’s likelihood of survival and increased their cost to parents. These changes, in turn, increased motivation for reduced family size but did not undermine the universal expectation of marriage and parenthood. This description of change was based on patterns in the West but the scope of the theory was assumed to be global. Demographers posited that this demographic transition was inevitable, unilinear and irreversible ( Casterline 2003 ).

The massive, two-decade long European Fertility Project (Coale and Watkins 1986) assessed the fit of European historical data to this theory. While not discrediting the distal influences of industrialization, on a decadal time scale the fertility decline took on a pattern best described as “social contagion”, a change driven by new ideas and new options as opposed to individual decision-makers changing assessment of the “costs” of children ( Cleland and Wilson 1987 ). In other words, the decline of fertility in Europe showed a pattern suggesting “contagion” or “diffusion” – the best predictor of fertility decline for European provinces was the fertility behavior of neighboring provinces – rather than structural changes.

Lesthaeghe contributed greatly to the European fertility project through his early empirical work, The Decline of Belgian fertility, 1800–1970 ( Lesthaeghe 1977 ), and his analyses of the European Project’s multi-nation provincial data ( Lesthaeghe and Wilson 1986 ). He argued that new modes of thinking were fundamental to the speed and timing of fertility decline. These new modes of thinking involved the social acceptability and multiple advantages of controlling fertility. Subsequent fertility declines among developing countries in the post WWII period were of similar character (see Cleland and Wilson 1987 ; Bongaarts and Watkins 1996 ). The role of new ideas legitimating small family size and family planning are now central to the DT.

Why is the second demographic transition (SDT) not just a continuation of the first? Given the findings of the European Fertility Project on the role of “new modes of thinking” one possible narrative would stress continuity in the mechanisms producing change. But instead the proponents of SDT argue that the focal phenomenon changed – it was no longer smaller family size; it became fertility postponement and increased voluntary childlessness ( Lesthaeghe 2010 , pp. 216; van de Kaa 2001 , pp.302; van de Kaa 2002 , pp.10). The watershed between the first and the second demographic transitions is the shift in norms, from altruistic to individualistic ( van de Kaa 2002 , pp.5; Lesthaeghe 1995 , pp.19*; Lesthaeghe 2014 , pp.18112). New motivations underlying family formation behavior distinguished the second transition from the first. Greater female emancipation and individual autonomy were more central to SDT than they were to the first transition ( Lesthaeghe 1995 pp.18).

C. Theoretical motivations

Van de Kaa and Lesthaeghe mention three arguments that convinced them that the SDT was truly different from the DT, a discontinuity anchored in an irreversible shift in motivation and sentiment. We discuss these in turn.

Shift from king-child to king-couple

Van de Kaa and Lesthaeghe were heavily influenced by Aries’ claim that motivational shifts lead to fertility decline in the West over the twentieth century ( Aries 1980 ). Aries argued that even if the phenomenon of fertility decline experienced by the western world during the 1960s was not new, as pointed out by historians, the motivations behind it were; the resumption of fertility decline in the post-war period reflected a different outlook on life. To explain, Aries pointed out that “society has always controlled nature and domesticated sexuality” ( 1980 pp. 646). As early as the 16 th century, Europeans practiced fertility control in the form of delayed marriages. Malthus (1888) captured this view by claiming that the “passion between the sexes” was too great for married couples to practice fertility control via abstinence (and Malthus viewed other means as immoral). People did not think to control the frequency of intercourse to influence pregnancy; “automatic unplanned behavior” and surrender to impulses/destiny was the norm. Consistent with this Malthusian claim, marriage timing was the only mechanism of fertility control available ( Aries 1980 , pp.646).

Change occurred when couples began to plan their families using foresight and organization. For Aries (1980 , pp.646), this “revolution in sensibility” was perhaps as important as the French or Industrial Revolutions. He argued that this “planned parenthood” occurred before the availability of modern contraceptive technology, it relied on behavioral and sex-proximal methods (especially withdrawal and abstinence), and was in part successful because of a culture of self-control or non-coital, premarital eroticism.

Aries (1980) claimed that this is when affection became centered on children and the family, and families became more inward looking, organizing themselves in terms of children and their futures (note that he does not explain why this change took place). This led to a child-oriented society and to greater investment in children; these changes encouraged small families. During this period, birth control and lower fertility were the consequence of wanting one’s children to be upwardly mobile.

In response to the persistence of the child’s status as “king” during the Baby Boom period of rising fertility, Aries argued that younger women began to revolt against the burdens of motherhood. This was aided by the revolution in contraceptive technology – ‘the era of the pill began’ – and triggered a shift from “trustful modernity” to rebellion by the late 1960s (1980, pp.648). The post-baby boom resumption of declining birth rates was categorically different from that of the 1930s. According to Aries, the vast majority of couples did not now limit family size in order to move up the social ladder, but instead to free themselves from family obligations (1980, pp.648). And the availability of advanced contraceptive technology alone could not explain its wide acceptability and uptake.

Aries rejected alternative explanations and believed that the refusal to have an undesired child (by resorting to abortion) was a critical new phenomenon. It reflected the end of the “child-king” days, the child was no longer essential in couples’ plans; instead a child was just one of the components that might allow adults to blossom as individuals (pp.649). The couple and their relationship was now “king” and might make room for a child.

The proponents of SDT coined this the transition from the “king-child with parents” to a “king-couple with child” ( van de Kaa 1987 , pp. 11; van de Kaa 2002 , pp.5;). The justification of the SDT as a distinct transition rests heavily on this historical interpretation. Since the SDT is not solely about changes in birth rates, its proponents incorporated other theories of social change in their explanatory framework. Lesthaeghe (1995) argued that the SDT reflects and builds on not just Aries’ motivational shift theory, but several other irreversible revolutions in the Western world: the sexual revolutions proposed by Shorter (1971) , Westoff’s (1977) contraceptive revolution, as well as Sauvy’s (1960) characterization of the first transition as altruistic (and the second as individualistic). The shift to “king couple” or the rising importance of the adult dyad led to an increase in the minimal standards of union/marriage quality ( Lesthaeghe 1995 ).

The Maslowian drift and rise of individualism

Inglehart’s claims of a shift from materialist to post-materialist values also played a critical role in the elaboration of the SDT ( van de Kaa 1987 ; Lesthaeghe 1995 ; Lesthaeghe 2010 ). This value shift embodies the “Maslowian drift” that both proponents place at the heart of the second demographic transition – a shift toward higher-order needs of self-actualization and individual autonomy to motivate behavior once more basic needs like survival and safety have been satisfied ( Lesthaeghe 1995 ). The demographic changes since 1960 cannot be divorced from Inglehart’s (1990) ‘silent revolution’ that is argued to have taken place in Western nations as a result of the post-war economic affluence and security ( Lesthaeghe 1995 ; 2011 ). In recent statement of the theory, Lesthaeghe (2010 , pp.216) linked the Maslowian drift with a set of other transitions, the contraceptive revolution, the sexual revolution and the gender revolution, all fitting within a framework of rejection of authority and overhaul of normative structures.

Pushback against economic explanations

This SDT ideational reorientation occurred during peak years of economic growth. Both SDT proponents ( van de Kaa 1987 , 1994 ; Lesthaeghe 1995 ; Lesthaeghe 2014 ) acknowledge that SDT does not negate economic explanations of family change, such as those offered by Becker (1973 , 1974 , 1991 ) and Easterlin (1973 , 1976) . They acknowledged that the shifts in the quality-quantity tradeoff with respect to children as a useful concept in explaining the first demographic transition. Moreover, they credit rising female labor force participation as having an important role in the SDT. However, the economic models for fertility change allow for the reversal of trends experienced in the post-War period, and this is where the economic theories are at odds with one of the central tenants for the SDT – the irreversibility of changes in family and fertility (weakening of traditional family systems and below replacement fertility) ( Lesthaeghe 1995 , Lesthaeghe (2010 , pp.). In the language of classical economics, tastes and preferences have irreversibly changed.

SDT treats ideational change primarily “as exogenous influences that add stability to trends over and beyond economic fluctuations” ( Lesthaeghe 2014 , pp. 18113). So Lesthaeghe (1995 , 2010) emphasizes, that although compatible, the economic models are incomplete without the cultural/ideational explanations that SDT theory offers. He uses the strong empirical link between cohabitation and secularization to highlight this point, arguing that this link cannot be accounted for by Becker’s structural economic theory or Easterlin’s theory of labor market conditions ( Lesthaeghe 1995 ). Secularization is a manifestation of individual autonomy. Economic theories are incomplete without the Maslowian shift to higher order needs.

In summary, for the SDT, ideational change, as seen through the increase in individual autonomy, secularization, female emancipation, and post-materialism, is the central explanation, without which all other explanations are incomplete.

D. Expanding the SDT substantive and geographic scope

Initially the SDT was proposed as an explanation for below-replacement fertility and union formation changes in Europe. Early on the theory’s scope expanded to include mortality and migration patterns, but fertility/family change remained the primary focus. Specifically, SDT’s proponents ( van de Kaa 1994 , 1999 ) incorporated mortality and migration in a discussion of the unexpected and dramatic improvements in life expectancy (at birth as well as at advanced ages), and the initiation of guest worker schemes in Western European countries. Both van de Kaa and Lesthaeghe have argued that the role of migration changed. In the first transition (DT) emigration acted as a safety valve in maintaining equilibrium; in the second transition (SDT) immigration played a key role in maintaining national-level demographic homeostasis. “Replacement migration” is to the second demographic transition what replacement fertility was to the first transition ( Lesthaeghe 2010 , 2014 ). These changes in migration patterns contributed to an important divide in Europe’s population development halfway through the 20 th century ( van de Kaa 2002 ).

On the other hand, changes in mortality during the second transition (SDT) were not uniquely different from those that took place during the first transition. That it is to say that life expectancy continued to improve throughout the two transitions. However, according to SDT proponents, similar to fertility, mortality changes in the second transition were, and continue to be, strongly influenced by ideational and normative changes. That is, individuals took on greater responsibility for their health and adopted preventive measures that reflect value systems stressing self-fulfillment and individual freedom ( van de Kaa 2002 pp.22, 2004 pp.6). These SDT insights into the causes of migration and mortality change have not had the impact of those focusing on family and fertility.

The geographic scope of SDT has also expanded. Lesthaeghe (1995) aggressively extended the geographic reach of the SDT theory to all OECD countries ( Lesthaeghe 1995 ). SDT went from explaining changes in Europe to changes in industrialized nations more broadly, which meant the addition of the US, Canada, and Australia, New Zealand and Japan. In his more recent work Lesthaeghe (2010) claims that the SDT may have explanatory value for understanding worldwide family and fertility changes, given that the countries under consideration are “wealthy enough to have undergone the Maslowian drift” (pp. 234). Several East Asian countries, which have industrialized and urbanized, qualify for being considered as a testing ground for the SDT. But Lesthaeghe (2010) cautions that even in countries that meet this criteria, additional features are required for the identification of the SDT: below replacement fertility is linked to postponement; rising age at marriage conditional on female autonomy and partner choice; rise in prevalence and acceptance of premarital cohabitation; a link between demographic change and value orientation (pp234). He accounts for the fact that not all four of these features were present in all European countries before they entered the SDT by stating that the demographic characteristics of the SDT do not have to occur simultaneously but instead are likely to be lagged (2010, pp.234).

We should note, that the more recent works of van de Kaa and Lesthaeghe have diverged somewhat. Works by van de Kaa do not typically refer to the SDT as a theory or even a theoretical framework. Only a few years after his original piece on the SDT ( van de Kaa 1987 ), van de Kaa (1994) broadened the historical description to include two other dimensions of the social system in addition to culture/ideational change – structure and technology. Later he proposed treating the ideational change framework of the SDT as an anchored narrative or social history, with sub-narratives where necessary to explain variations ( van de Kaa 1996 ). He does, however, still support the validity of the SDT as a new demographic regime or “revolution” ( van de Kaa 2010 , pp.5).

Lesthaeghe’s work on the other hand has often used the term “SDT theory” or theoretical framework ( Lesthaeghe and Surkyn 2008 ; Lesthaeghe 2010 , 2011 , 2014 ). He is also much more vested in the ideational change explanation, with much of his work focusing on the contribution of the ideational change theory to understanding post WWII demographic change ( Lesthaeghe 1998 ), and establishing the links between the spread of post-materialist values and that change ( Surkyn and Lesthaeghe 2004 ). Much of the following discussion in this review focuses on Lesthaeghe’s highly visible and expansive use of the SDT, as opposed to van de Kaa’s historical and more circumscribed descriptive work.

III. EMPIRICAL ADEQUACY OF THE SDT

Lesthaeghe (e.g., 2010) has elaborated the SDT in response to emerging and (according to the SDT) unexpected demographic realities. This is an expected step in “the wheel of science” (or paradigmatic science) that re-establishes an acceptable fit between data and theory. Below we describe the fit of SDT predictions with observed changes, and we note elaborations of SDT (if any) to this evidence.

A. Union and family formation

Changes in union formation are at the heart of the second demographic transition. The SDT-related value changes are predicted to cause: mean age at marriage to increase, first marriage rates to decline, divorce rates to rise, cohabitation to become increasingly common and accepted, and the proportion of non-marital births to increase.

Broadly speaking, recent change in union formation are consistent with SDT expectations (see Cherlin 2012 : 585–586) as well as with what Cherlin (2004) called the “deinstitutionalization of marriage”. Age at marriage has increased worldwide ( Ortega 2014 ); Asian countries like Japan, Korea and Taiwan are now some of the latest-marrying countries in the world ( Raymo et al 2015 ) and even African nations are experiencing a rapid increase in age at marriage (Shapiro and Gebreselassie 2014). Further, there is no Western country where the proportions never-marrying have not increased from their levels in the early 20 th century ( van de Kaa 2002 ; Cherlin 2014 ). The decline in rates of first marriage rates has been even more dramatic in East Asian countries with economic growth matching Western nations, although variations by socioeconomic class remain ( Raymo et al 2015 ). In China age at marriage increased dramatically in the 1970s, but, has experienced relatively little marriage change (albeit in the expected direction) since. Marriage remains nearly universal and within a narrow age range ( Raymo et al 2015 ).

But when one looks more closely at the data questions arise. First, although marriage rates did decline in most industrialized countries after the middle of the 20 th century, these trends show a modest reversal in the vanguard nations of the SDT (Sweden and Denmark) as early as the 1990s ( van de Kaa 1994 ). Second, the mean age at marriage in low and middle-income countries is currently reaching the level that wealthier countries had reached in the 1970s ( Cherlin 2014 ), with several countries in Africa experiencing age at marriage nearly as high as that in contemporary Europe. Perhaps postmodern values are diffusing to new settings spawning an earlier start of the SDT ( Lesthaeghe 2010 : 244–45), in a way analogous to what Thornton calls “developmental idealism” (2001). Or more likely, high/rising ages at marriage are a response to greater economic crises and uncertainty (Shapiro and Gebreselassie 2014) or women’s dissatisfaction with the conflicts of rapidly changing economic participation and persistent traditional gender roles ( Frejka et al 2010 ; Jones and Yeung 2014 ).