- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

How D-Day Changed the Course of WWII

By: Roy Wenzl

Updated: March 13, 2024 | Original: April 23, 2018

The D-Day military invasion that helped to end World War II was one the most ambitious and consequential military campaigns in human history. In its strategy and scope—and its enormous stakes for the future of the free world—historians regard it among the greatest military achievements ever.

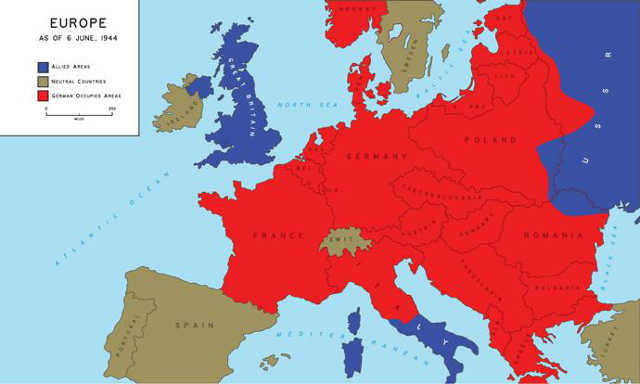

D-Day, code-named Operation Overlord, launched on June 6, 1944, after the commanding Allied general, Dwight D. Eisenhower , ordered the largest invasion force in history—hundreds of thousands of American, British, Canadian and other troops—to ship across across the English Channel and come ashore on the beaches of Normandy , on France’s northern coast. After almost five years of war, nearly all of Western Europe was occupied by German troops or held by fascist governments, like those of Spain and Italy. The Western Allies’ goal: to put an end to the Germany army and, by extension, to topple Adolf Hitler ’s barbarous Nazi regime.

Here’s why D-Day remains an event of great magnitude, and why we owe those fighters so much:

Halting the Nazi Genocidal Machine

German armies during World War II overran most of Europe and North Africa and much of the western Soviet Union . They set up murderous police states everywhere they went, then hunted down and imprisoned millions. With gas chambers and firing squads they killed 6 million Jewish people and millions more Poles, Russians, gays, disabled people and others undesirable to the Nazi regime, which sought to engineer a master Germanic race.

“It’s hard to imagine what the consequences would have been had the Allies lost,” says Timothy Rives, deputy director of the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas. “You could make the argument that they saved the world. A few months after D-Day, General Eisenhower visited a German death camp, and wrote: “We are told the American soldier does not know what he is fighting for. Now, at least, he will know what he is fighting against.”

Invasion Went Beyond the Beaches

The “D” in D-Day means simply “Day,” as in “The day we invade.” (The military had to call it something.) But to those who survived June 6, and the subsequent summer-long incursion, D-Day meant sheer terror. Raymond Hoffman, from Lowell, Massachusetts, gave an oral history interview in 1978 at the Eisenhower Library about the life-and-death fear he survived as a 22-year-old paratrooper in the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division.

On D-Day he parachuted with a hard thud into a Normandy cow pasture only minutes after midnight—and he heard footsteps approaching fast, even before he could unhook himself from his parachute straps.

“Boy, here I am,” he thought. “Five minutes on the ground and I’m about to get it. And I’m flat on my back, and…I got to roll, and I can’t get to my weapon and now… I can’t find my knife! And the footsteps have stopped…and (suddenly) I am looking up into the eyes of a big, brown cow.”

That was worth a grin then. But hours later, “some mysteries in life were removed,” Hoffman said.

In a gunfight with German soldiers, where bullets flew so thick that no one dared raise their heads to look up, he removed “the mystery” he’d pondered for months—about whether fear in combat would compel him to run or to fight.

He fought. And there was no longer any mystery: “You now know what it is like to be fired upon,” he said, “as well as to fire.”

An Effort of Staggering Scale

“I had some fun here one day looking up statistics, of all the stuff the Allies piled up on the beaches of southern England to support the invasion,” says Rives. “They had massive ammo dumps, and supply dumps, and in one of those supply dumps they had piled up 3,500 tons of bath soap—which Eisenhower later sent into France so the soldiers could take baths.

“He had 3 million troops under his command, and what they all devoured in just one day was stupendous,” says Rives. According to historian Rick Atkinson, commanders had “calculated daily combat consumption, from fuel to bullets to chewing gum, at 41.298 pounds per soldier. Sixty million K-rations, enough to feed the invaders for a month, were packed in 500-ton bales.”

Steep Casualties

German machine-gunners mowed down hundreds of Allied soldiers before they ever got off the landing boats onto the Normandy beaches. But Eisenhower overwhelmed them, Rives says, with 160,000 assault troops, 12,000 aircraft and 200,000 sailors manning 7,000 sea vessels.

Their losses were steep: The eight assault divisions now ashore had suffered 12,000 killed, wounded and missing, with thousands more unaccounted for, according to Atkinson. The Americans lost 8,230 of the total.

“Many were felled by 9.6-gram bullets moving at 2,000 to 4,000 feet per second,” Atkinson wrote. “Such specks of steel could destroy a world, cell by cell.”

Three thousand French civilians were killed in the invasion, mostly by Allied bombs or shell fire. By then the French had lost so much in the war that they’d run out of medical supplies. Some injured citizens were reduced to disinfecting their wounds with calvados, the local brandy fermented from apples, according to Atkinson.

But when the Allied soldiers marched inland from the beaches, the French cheered, many of them giving soldiers flowers, many of them sobbing in happiness.

D-Day Strategy

No one thought victory was sure. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had pestered Eisenhower and President Franklin Roosevelt for two years before D-Day, pleading that they avoid Normandy and instead pursue a slower, less dangerous strategy, putting more troops into Italy and southern France.

But the Germans had killed tens of millions of civilians and soldiers in the Soviet Union, and the Soviets desperately wanted the Allies to bleed the Germany army by opening up a second front of battle. Eisenhower thought it disgraceful to avoid Normandy, and thought Normandy was the best military move, not only to win but to shorten the war.

The Allies had long planned the invasion for a narrow window in the lunar cycle that would provide both maximum moonlight to illuminate landing places for gliders—and low tides at dawn to reveal the German’s extensive underwater coastal defenses. Poor weather forced Allied troops to delay the operation a day, cutting into that window. But in a stroke of luck, German forecasters predicted that gale-force winds and rough seas would deter the invasion even longer, so the Nazis redeployed some of their forces away from the coast. German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel even traveled home to celebrate his wife’s birthday, bringing her a pair of Parisian shoes.

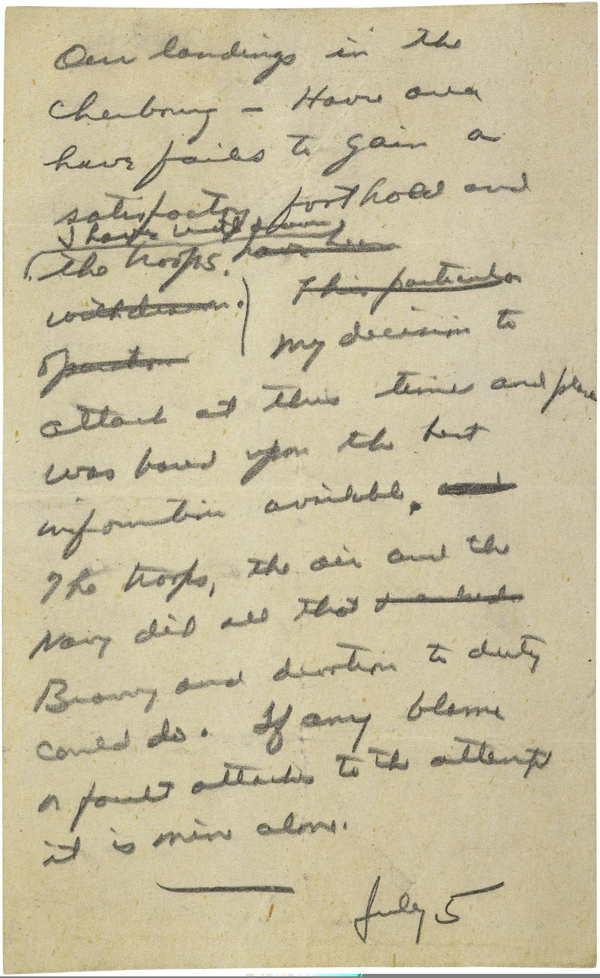

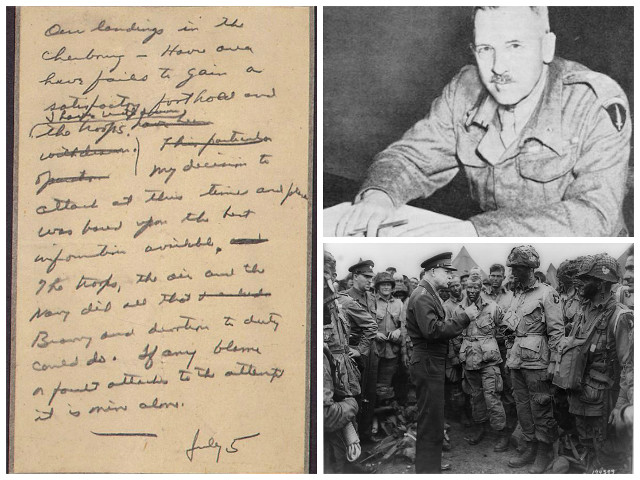

On the night before the invasion, Eisenhower penciled himself an “In case of failure” note, to be published if necessary: “If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone,” he wrote.

“Of all the documents we have from his time in the Army and in his eight years of the presidency, I regard that as our most significant document here,” Rives said of the collection at the Eisenhower Library. “It shows the character of the man who led it all.”

Eisenhower hated war. Years after the war ended, he gave a speech, with a paragraph that can be seen engraved in the marble stone wall surrounding his tomb in Abilene, Kansas.

“Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies in the final sense a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children. This is not a way of life at all in any true sense.”

The Importance of the D-Day Victory

Most battles are quickly forgotten. But all free nations owe their culture and democracy to D-Day, which can be grouped among some of the most epic victories in history. They include George Washington ’s defeat of the British army at Yorktown in 1781, which allowed the American experiment in democracy to survive, and to inspire oppressed people everywhere.

And in 490 and 480 B.C, the small armies and navies of Greece defeated the huge invading forces of the Persian Empire at the battles of Marathon and Salamis. The Greeks saved not only themselves, but their democracy, classic literature, art and architecture, philosophy and much more.

Historians put D-Day in the same category of greatness.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Written by: Edward G. Lengel, The National World War II Museum

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain the causes and effects of the victory of the United States and its allies over the Axis Powers

Suggested Sequencing

Use this narrative with the Dwight Eisenhower, D-Day Statement, 1944 Primary Source to give students a fuller understanding of the campaign. This narrative can also be used with the Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima Narrative and the Phil “Bo” Perabo, Letter Home, 1945 Primary Source to showcase American soldiers’ experiences during WWII.

Allied leaders had debated opening a second front in German-occupied western Europe as early as 1942. Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin’s pressure to launch such a front was unrelenting and reiterated at every Allied conference. Developing the means to launch a successful invasion was far from easy, however. Until 1944, the United States and Great Britain lacked the forces and the means to attack the Germans in France and successfully open a beachhead to invade Normandy. And success was all important. If a large-scale invasion failed, the results would be disastrous, and not just in terms of troops lost. Assembling another invasion might take years.

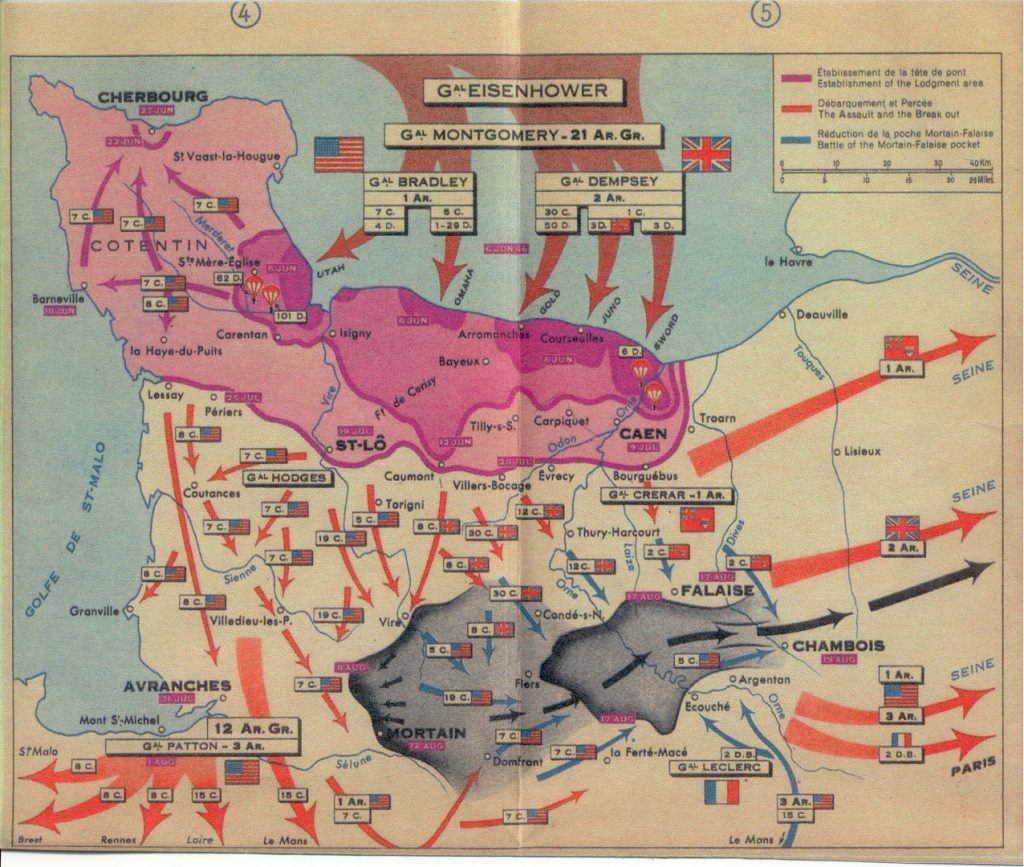

By the spring of 1944, however, the outlines of what came to be called Operation Overlord were complete. Five divisions of American, Canadian, and British troops, supported by three airborne divisions of paratroopers and glider-borne soldiers, were to land on beachheads in Normandy. After securing the landing beaches, establishing a firm perimeter, capturing the port of Cherbourg, establishing portable harbors there for resupply, and assembling armored reinforcements, Allied forces could drive inland to begin the liberation of France.

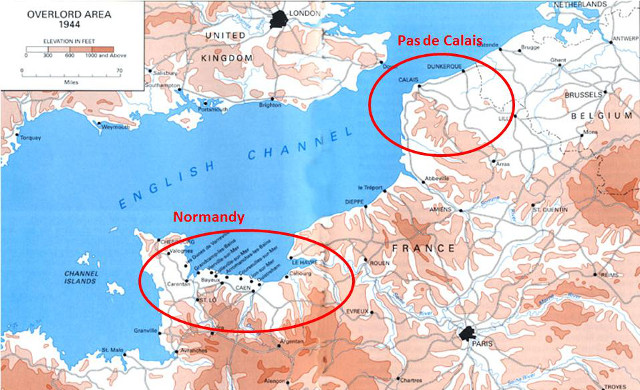

Several moving pieces had to be put in place before the plan could get underway. First, adequate naval support, and especially transport and landing craft, had to be secured – an especially difficult undertaking given the demands of warfare in both Europe and the far-flung Pacific, where amphibious landings on the Japanese-held islands were frequent. Second, American and British air forces had to work in complete coordination with ground forces, not only placing paratroopers and glider-borne forces on target but also preventing German efforts to move reinforcements and especially panzer divisions toward the beaches. Third, Free French forces, some owing allegiance to General Charles De Gaulle and others not, had to be alerted to the invasion and their support coordinated. Finally, an elaborate campaign of deception was established to convince the Germans that the primary Allied invasion would take place not in Normandy but at the heavily defended and more centrally located Pas de Calais, at the narrowest point of the English Channel.

Coordinating these factors, many under the control of disparate personalities who had different ideas about how the invasion should take place, took months. The Allied Supreme Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower, working with British General Bernard Law Montgomery (in command of the invading ground forces) and British commanders of the supporting naval and air forces, finally thought he had his pieces assembled at the beginning of June, but there was one final decision to be made. Because of the tides and other factors, the Allies could land at the beaches of Normandy only on certain dates, but weather reports suggested unsettled weather in early June. In a tense meeting at his headquarters in Bletchley Park, England, Eisenhower elected to gamble on a break in the weather and said “Go” for the invasion on June 6, 1944.

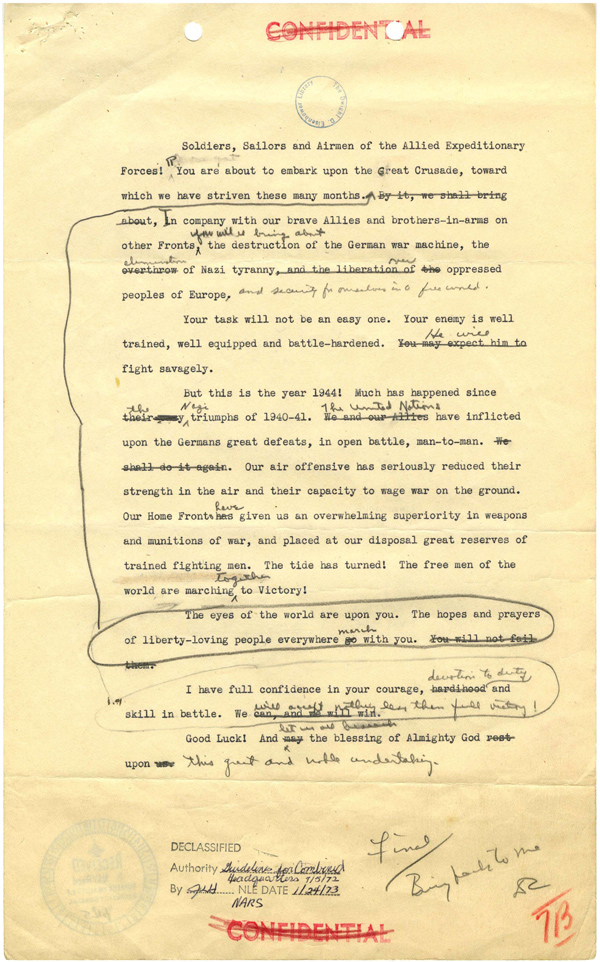

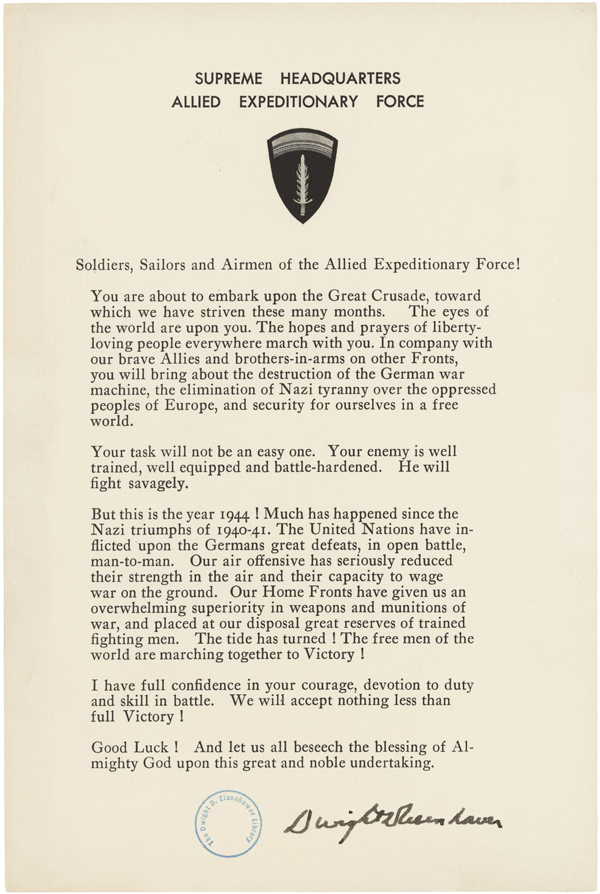

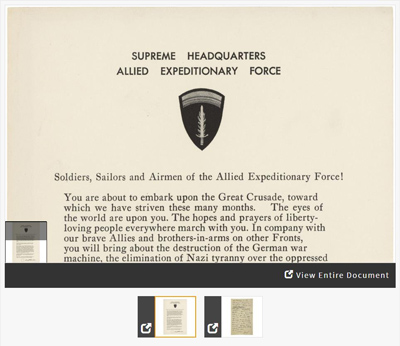

At this critical moment, Eisenhower’s leadership abilities came to the fore. Rather than remaining at headquarters, he made a point of visiting, encouraging, and even joking with the troops assembled to carry out the invasion. He dispatched a message to them declaring, “You are about to embark upon a great crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. . . . I have full confidence in your devotion to duty and skill in battle. We will accept nothing less than full Victory. Good luck! And let us all beseech the blessing of Almighty God upon this great and noble undertaking.” But the general also penned a draft dispatch to be sent in case the invasion failed, taking full responsibility upon himself.

American and British airborne troops carried out the first phase of the invasion by landing around the coastal villages behind German beach defenses on the night of June 5-6. Although badly scattered and forced to work in small, poorly armed groups, they succeeded in their primary mission of seizing – and, where necessary, destroying – important bridges and crossroads to hold back enemy reinforcements. U.S. Army Rangers carried out a heroic and costly assault against German cliffside emplacements at Pointe du Hoc overlooking Omaha Beach, only to discover that the enemy had already dismantled their heavy guns.

The primary invasion took place on five Normandy beaches, code-named (from west to east) Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword. British and Canadian troops landed at the latter three beaches against weaker-than-expected enemy opposition and quickly seized their immediate objectives. At Utah, thanks in part to airborne support inland, the U.S. 4th Division landed successfully and laid the groundwork for the capture of the Cotentin Peninsula and the all-important port of Cherbourg.

At Omaha Beach, however, facing strong tides and mistakes by inexperienced infantry and naval forces, the invasion nearly foundered. Here, troops of the U.S. 29th and 1st Divisions (the famous “Big Red One”) faced a strong defense from well dug-in and determined German infantry that they struggled to overcome. Heavy casualties on the beaches led General Omar Bradley, commanding the U.S. First Army, briefly to consider abandoning the beachhead. But the infantry refused to give up and, with great courage and sacrifice, they finally managed to break the German defenses and establish a defensive perimeter. Fortunately, Allied ground attack aircraft also succeeded in their primary missions of supporting airborne troops inland and inflicting heavy casualties on German armored and infantry forces as they rushed toward the beaches.

Although casualties had been heavy at places like Omaha Beach, overall Allied losses for June 6 totaled 4,900 killed, wounded, and missing – far lower than Eisenhower and his generals had anticipated. The five Allied beachheads were linked together by June 12, and by the end of the month, Cherbourg had been captured. Firmly entrenched and supplied, thanks in part to elaborate and expensive portable harbors codenamed Mulberry that were established on the Normandy beaches (although one was destroyed by a storm on June 19), the Allies had succeeded in forming the long-awaited second front. Although the drive inland proved far more difficult than anticipated, the process of the liberation of Western Europe had begun.

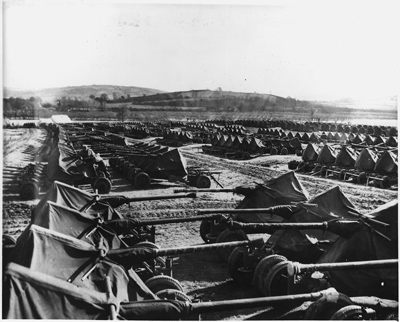

One of the Mulberry harbors established on the D-Day beaches in 1944, which allowed the Allies to secure supplies to liberate France.

Review Questions

The outcome of the events depicted in the photograph resulted in

- the liberation of Western Europe

- the fall of Japan

- the creation of the League of Nations

- the presidential election of Herbert Hoover

2. The Allied leader overseeing D-Day was

- Erwin Rommel

- Dwight Eisenhower

- George Marshall

- Bernard Law Montgomery

3. One of the key concerns in Allied planning for Operation Overlord was

- securing the support of the Soviet Union

- amassing enough naval support to transport and land troops and equipment

- getting the help of the French resistance

- getting the approval of Harry Truman

4. The D-Day invasion marked the

- beginning of the development of an atomic bomb

- fall of Benito Mussolini’s Italy

- surrender of Adolf Hitler to Allied troops

- opening of a second front against Nazi Germany

5. The Normandy invasion in World War II was considered necessary to

- stop the spread of Japanese imperialism

- relieve the pressure on the eastern front

- save Italy from falling to Nazi Germany

- keep the Nazis from developing a nuclear bomb

6. The night before the D-Day landings American and British troops successfully

- surprised and destroyed German army headquarters

- dismantled the bulk of Nazi shore defenses

- captured vital bridges and crossroads

- captured Adolf Hitler

Free Response Questions

- Explain the need for the D-Day invasion in World War II.

- Explain the Allies’ challenges in planning the D-Day invasion in World War II.

AP Practice Questions

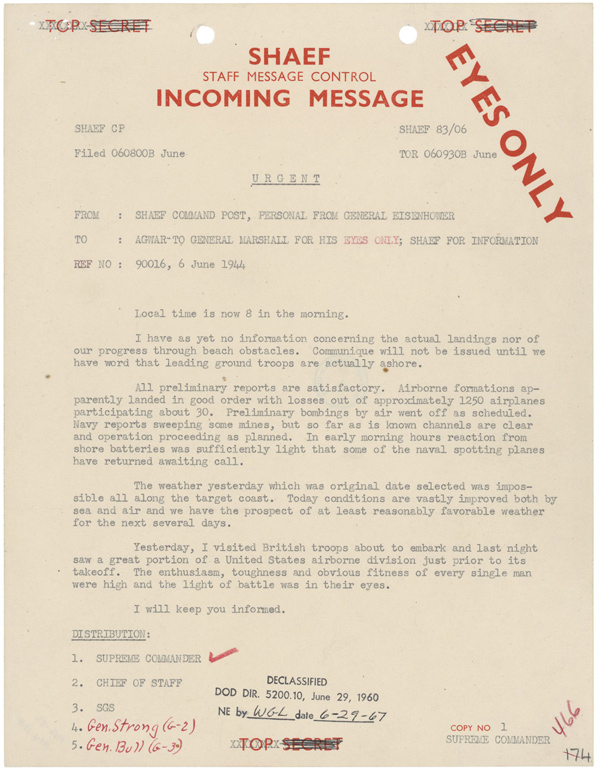

“SUPREME HEADQUARTERS ALLIED EXPEDITIONARY FORCE Soldiers, Sailors, and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force! You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hope and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other Fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world. Your task will not be an easy one. Your enemy is well trained, well equipped and battle-hardened. He will fight savagely.”

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Order of the Day, 1944

1. The sentiments expressed in Eisenhower’s “Order of the Day” most directly led to

- the collapse of fascist regimes in Europe

- the fall of communism in Eastern Europe

- the dropping of the atomic bomb

- the beginning of the Cold War

2. The situation referred to in the excerpt from Eisenhower’s Order of the Day was directly shaped by

- the establishment of a fully integrated American military

- the success of the Treaty of Versailles

- the defeat of Nazi tyranny by the free nations of the world

- the success of the island-hopping campaign in the Pacific Theater of Operation during World War II

3. The sentiments in the excerpt were most directly shaped by

- the Monroe Doctrine

- technological advances in military armaments

- rejection of the collective-security provision in the League of Nations covenant

- the belief that the war was a fight for the survival of democracy

Primary Sources

Baumgarten, Harold. D-Day Survivor: An Autobiography . New York: Pelican, 2006.

Santoro, G. “Omaha the Hard Way: Conversation With Hal Baumgarten.” http://www.historynet.com/omaha-hard-way-conversation-hal-baumgarten.htm

Suggested Resources

Ambrose, Stephen E. D-Day June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II . New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994.

Atkinson, Rick. The Guns at Last Light: The War in Western Europe, 19441945 . New York: Henry Holt, 2013.

Beevor, Antony. D-Day: The Battle for Normandy . New York: Viking, 2009.

Caddick-Adams, Peter. Sand and Steel: The D-Day Invasion and the Liberation of France . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Chambers, John Whiteclay, ed. The Oxford Companion to American Military History . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1999.

D’Este, Carlo. Decision in Normandy . New York: Harper, 1994.

Hastings, Max. Overlord: D-Day and the Battle for Normandy . New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984.

Holland, James. Normandy ’44: D-Day and the Epic 77-Day Battle for France . New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2019.

Keegan, John. Six Armies in Normandy: From D-Day to the Liberation of Paris . New York: Viking, 1983.

Kershaw, Alex. The Bedford Boys: One American Town’s Ultimate D-Day Sacrifice . New York: Da Capo Press, 2003.

Kershaw, Alex. The First Wave: The D-Day Warriors Who Led the Way to Victory in World War II . New York: Dutton Caliber, 2019.

McManus, John C. The Dead and Those About to Die: D-Day: The Big Red One at Omaha Beach . New York: Dutton Caliber, 2014.

Ryan, Cornelius. The Longest Day: June 6, 1944 . Reprint. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994

Weinberg, Gerhard L. A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Related Content

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

In our resource history is presented through a series of narratives, primary sources, and point-counterpoint debates that invites students to participate in the ongoing conversation about the American experiment.

Educator Resources

General Dwight D. Eisenhower was appointed the Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force during World War II. As leader of all Allied troops in Europe, he led "Operation Overlord," the amphibious invasion of Normandy across the English Channel. Eisenhower faced uncertainty about the operation, but D-Day was a military success, though at a huge cost of military and civilian lives lost, beginning the liberation of Nazi-occupied France. Read more...

Primary Sources

Links go to DocsTeach , the online tool for teaching with documents from the National Archives.

Ordnance Depot in England, "Ready and Waiting for D-Day"

General Dwight D. Eisenhower Giving the Order of the Day

American Soldiers Landing off the Coast of France

"In Case of Failure" Message Drafted by General Dwight Eisenhower in Case the D-Day Invasion Failed

Draft of Eisenhower's Order of the Day

General Eisenhower's Order of the Day

Cable from General Dwight D. Eisenhower to General George C. Marshall Regarding D-Day Landings

Sketch of a D-Day Platoon Leader's Dress

Teaching Activities

The Night Before D-Day on DocsTeach asks students to analyze two documents written by General Dwight Eisenhower before the invasion of Normandy on D-Day: his "In Case of Failure" message and his Order of the Day. Students will compare and contrast these documents to gain a better understanding of the mindset of Allied leaders on the eve of the invasion.

The World War II page on DocsTeach includes other primary sources and document-based teaching activities related to World War II. It includes topics such as D-Day, women in the war, Code Talkers, propaganda posters, the homefront, the Holocaust, Pearl Harbor, the atomic bomb, war crimes and trials, and more.

Additional Background Information

During World War II, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill jointly planned strategies for the cooperation and eventual success of the Allied armed forces.

Roosevelt and Churchill agreed early in the war that Germany must be stopped first if success was to be attained in the Pacific. They were repeatedly urged by Stalin to open a "second front" that would alleviate the enormous pressure that Germany's military was exerting on Russia. Large amounts of Soviet territory had been seized by the Germans, and the Soviet population had suffered terrible casualties from the relentless drive towards Moscow. Roosevelt and Churchill promised to invade Europe, but they could not deliver on their promise until many hurdles were overcome.

Almost immediately after France had fallen to the Nazis in 1940, the Allies had planned an assault across the English Channel on the German occupying forces. Initially, though, the United States had far too few soldiers in England for the Allies to mount a successful cross-channel operation.

So in July 1942, Churchill and Roosevelt decided on the goal of occupying North Africa as a springboard to a European invasion from the south. Invading Europe from more than one point would also make it harder for Hitler to resupply and reinforce his divisions. In November, American and British forces under the command of U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower landed at three ports in French Morocco and Algeria. This surprise seizure of Casablanca, Oran, and Algiers came less than a week after the decisive British victory at El Alamein. The stage was set for the expulsion of the Germans from Tunisia in May 1943, the Allied invasion of Sicily and Italy later that summer, and the main assault on France the following year.

At the Quebec Conference in August 1943, Churchill and Roosevelt reaffirmed their plan for a cross-channel assault into occupied France, which was code-named Overlord. Although Churchill acceded begrudgingly to the operation, historians note that the British still harbored persistent doubts about whether Overlord would succeed.

The decision to mount the invasion was cemented at the Tehran Conference held in November and December 1943. Joseph Stalin, on his first trip outside the Soviet Union since 1912, pressed Roosevelt and Churchill for details about the plan, particularly the identity of the Supreme Commander of Overlord. Churchill and Roosevelt told Stalin that the invasion "would be possible" by August 1, 1944, but that no decision had yet been made to name a Supreme Commander. To this latter point, Stalin pointedly rejoined, "Then nothing will come of these operations. Who carries the moral and technical responsibility for this operation?" Churchill and Roosevelt acknowledged the need to name the commander without further delay.

General Eisenhower was named Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force shortly after the conference ended. When in February 1944 he was ordered to invade the continent, planning for Overlord had been under way for about a year. By May 1944, hundreds of thousands of Allied troops from the United States, Great Britain, France, Canada, and other nations were amassed in southern England and intensively trained for the complicated amphibious action against Normandy. While awaiting deployment orders, they prepared for the assault by practicing with live ammunition.

In addition to the troops, supplies, ships, and planes were also gathered and stockpiled. The largest armada in history, made up of more than 4,000 American, British, and Canadian ships, lay in wait. More than 1,200 planes stood ready to deliver seasoned airborne troops behind enemy lines, to counter German ground resistance as best they could, and to dominate the skies over the impending battle theater. Countless details about weather, topography, and the German forces in France had to be learned before Overlord could be launched in 1944.

Against a tense backdrop of uncertain weather forecasts, disagreements in strategy, and related timing dilemmas predicated on the need for optimal tidal conditions, Eisenhower decided before dawn on June 5 to proceed with Operation Overlord. But his uncertainty about success in the face of a highly-defended and well-prepared enemy led him to consider what would happen if the invasion of Normandy failed. If the Allies did not secure a strong foothold on D-Day, they would be ordered into a full retreat. Later that day, he scribbled a note intended for release, accepting responsibility for the decision to launch the invasion and full blame, should Overlord fail.

However, Eisenhower's determination that the invasion of Normandy would bring a quick end to the war is obvious in his "order of the day," a message printed and given to the 175,000-member expeditionary force on the eve of the invasion. He had spent weeks carefully drafting the order, which would be distributed to all of the soldiers, sailors and airmen who were to participate. In it, he stated his "full confidence in [their] courage, devotion to duty and skill in battle."

Gen. Eisenhower went to visit Allied troops just before they set off to participate in the assault of occupied France on D-Day. He left his headquarters in Portsmouth, England, and first visited the British 50th Infantry Division and then the U.S. 101st Airborne at Newbury; the latter was predicted to suffer 80 percent casualties. After traveling 90 minutes through the ceaseless flow of troop carriers and trucks, his party arrived unannounced to avoid disrupting the embarkation in progress. The stars on the running board of his automobile had been covered, but the troops recognized "Ike," and word quickly spread of his presence. According to his grandson David Eisenhower, who wrote about the occasion in Eisenhower: At War 1943-1945 , the general

...wandered through the formless groups of soldiers, stepping over packs and guns. The faces of the men had been blackened with charcoal and cocoa to protect against glare and to serve as camouflage. He stopped at intervals to talk to the thick clusters of soldiers gathering around him. He asked their names and homes. "Texas, sir!" one replied. "Don't worry, sir, the 101st is on the job and everything will be taken care of in fine shape." Laughter and applause. Another soldier invited Eisenhower down to his ranch after the war. "Where are you from, soldier?" "Missouri, sir." "And you, soldier?" "Texas, sir." Cheers, and the roll call of the states went on, "like a roll of battle honors," one observer wrote, as it unfolded, affirming an "awareness that the General and the men were associated in a great enterprise.

At half past midnight, as Eisenhower returned to his headquarters at Portsmouth, the first C-47s were arriving at their drop zones, commencing the start of "The Longest Day." During the invasion's initial hours, Eisenhower lacked adequate information about its progress. After the broadcast of his communiqué to the French people announcing their liberation, SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) switchboards were overwhelmed with messages from citizens and political officials. SHAEF communications personnel fell 12 hours behind in transcribing radio traffic. In addition, an Army decoding machine broke down.

According to his secretary-chauffeur Kay Summersby, as recounted in David Eisenhower’s book, "Eisenhower spent most of the day in his trailer drinking endless cups of coffee, 'waiting for the reports to come.' Few did, and so Eisenhower gained only sketchy details for most of the day about the British beaches, UTAH and the crisis at OMAHA, where for several hours the fate of the invasion hung in the balance."

During the early hours of the D-day Normandy invasion, Eisenhower had sent a message to his superior, Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall, in Washington, DC. The statement reflects his lack of information about how well the landings were going, even though they were well under way at that moment. Eisenhower reported that preliminary reports were all "satisfactory." At that time, he had received no official information that the "leading ground troops are actually ashore." The incomplete and unofficial reports, however, were encouraging.

Eisenhower's comments concerning the weather speak to the one crucial factor of the invasion over which he held no control. Meteorologists were challenged to accurately predict a highly unstable and severe weather pattern. As he indicated in the message to Marshall, "The weather yesterday which was [the] original date selected was impossible all along the target coast." Eisenhower therefore was forced to make his decision to proceed with a June 6 invasion in the predawn blackness of June 5, while horizontal sheets of rain and gale force winds shuddered through the tent camp. The forecast that the storm would abate proved accurate, as he noted in his message.

Eisenhower's pride and confidence in the battle-tempered men he had met the preceding night—men he was about to send into combat—is also evident in his message. He closed on a confident note, describing the steely readiness of the men he sent to battle, recalling the resoluteness in their faces that he termed "the light of battle...in their eyes." This vivid and stirring memory doubtless heartened him throughout the day until conclusive word reached him that the massive campaign had indeed succeeded.

When the attack began, Allied troops confronted formidable obstacles. Germany had thousands of soldiers dug into bunkers – defended by artillery, mines, tangled barbed wire, machine guns, and other hazards to prevent landing craft from coming ashore.

The cost of military and civilian lives lost on D-Day was high. Allied casualties have been estimated at 10,000 killed, wounded, or missing – over 6,000 of those Americans. But by the end of the day, 155,000 Allied troops were ashore and in control of 80 square miles of the French coast. D-Day was a military success, opening Europe to the Allies and a German surrender less than a year later.

This text was adapted from an article written by David Traill, a teacher at South Fork High School in Stuart, FL, and the article: Schamel, Wynell B. and Richard A. Blondo. "D-day Message from General Eisenhower to General Marshall." Social Education 58, 4 (April/May 1994): 230-232.

Additional Resources

D-day video footage.

View a playlist of videos on D-Day and the Normandy Invasion from the holdings of the National Archives on YouTube .

D-Day Daily Situation Maps

These maps show troop dispositions and the location of the front line. View the maps on YouTube or in the National Archives online catalog .

More WWII Primary Sources

- "D-Day and the Normandy Invasion" Google Cultural Institute Exhibit

- Normandy Invasion and D-Day on DocsTeach

- D-Day in the National Archives online catalog

- WWII on DocsTeach

- WWII from the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum

- Online Documents from the The Harry S. Truman Library and Museum

WWII Research

- Records Relating to D-Day

Finding Information on Personal Participation in World War II (PDF), a helpful starting point

Albert H. Small Normandy Institute

Participants in this institute research a soldier from their hometown who fought in Normandy, and write a biography using primary sources from the holdings of the National Archives. Their visit to Washington, DC, includes a day dedicated to researching the soldiers' unit records at the National Archives at College Park, MD. The fifteen student-teacher teams also travel to France to explore historical sites in Normandy. Learn more at www.ahsni.com .

- X (formerly Twitter)

Why D-Day Matters

While the invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, usually termed D-Day, did not end the war in Europe—that would take eleven more months—success on that day created a path to victory for the Allies. The stakes were so great, the impact so monumental, that this single day stands out in history.

Toward Which We Have Striven

The planning of d-day.

The largest land, sea, and air invasion ever attempted was years in the making. World War II in Europe began with the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany in September 1939. Britain and France declared war in response but could do little to help the Poles. In the spring of 1940, German leader Adolf Hitler staged successful invasions of Denmark, Norway, Belgium, Holland, and other nations. German armies then moved into France, rapidly breaking through border defenses and pinning much of the British and French armies against the English Channel. While Britain was able to evacuate many of those forces from the area around Dunkirk, it left Nazi Germany dominant on the continent of Europe.

Almost immediately, British leaders began envisioning ways to get back across the Channel in an amphibious assault, eventually code-named Operation Overlord. Understanding the threat such an invasion would pose, Hitler began to build formidable defenses along the entire Channel coast, which he called his “Atlantic Wall.”

In 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, formerly a partner. Also, by the end of that year, the United States entered the war after Japan (an ally of Germany) attacked the American base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The entry of the U.S. into the Alliance meant the scope of the planned cross-Channel invasion would grow. Soon American forces began arriving in England to train for the invasion.

At the Tehran Conference in November 1943, Allied leaders decided the cross-Channel invasion would occur in the spring of 1944 with American general Dwight Eisenhower as Supreme Allied Commander of the multinational operation. Forces from twelve Allied nations (most occupied by Nazi Germany) would take part. The invasion had to be the most intricately planned military operation in history. Such questions as where and when to land; how many soldiers, tanks, ships, and planes would be needed; what equipment each man had to carry; and the essential question of how to keep this a secret from the enemy were debated and planned. The final plan called for some 156,000 men to land on five beaches on the coast of Normandy: the Americans at Utah and Omaha in the west, and the British and Canadians at Gold, Juno, and Sword. They would be bolstered by parachute and glider landings and supported by some 5,000 ships and 11,000 airplanes.

Planners set the date of June 5, 1944, for the landings, but a storm that day meant it would be too cloudy to bombard German coastal defenses and too windy for men to disembark from landing craft. British meteorologist James Stagg advised General Eisenhower of a temporary break in the weather, clearer skies, and lighter winds, which would potentially allow the invasion to commence twenty-four hours later. With his assault, naval, and air commanders all saying “go,” Eisenhower gave the order.

Victorious Allies

The Eyes of the World Are Upon You

June 6, 1944.

In the early hours of June 6, under the cover of darkness, American and British paratroopers dropped into Normandy from more than 1,200 aircraft. Once daylight appeared, gliders brought in additional paratroopers. American airborne forces of the 82nd and 101st worked valiantly to achieve their inland objectives, including the capture of Sainte-Mere Eglise and securing key approaches to the Allied beachhead.

The largest naval bombardment ever seen began at 5:30 AM, lasting only forty minutes. American battleships supported by cruisers and destroyers and the British Royal Navy with a similar group of ships shelled gun emplacements and defensive positions around their designated beaches.

The sunrise on June 6 brought with it wave after wave of landing vessels, carrying the more than 150,000 American, British, Canadian, and French ground troops who stormed some fifty miles of coastline in Northern France, beaches fiercely defended by the Germans.

Strong currents pushed the Americans 2,000 yards south of Utah Beach, forcing them to march that distance back to the intended landing areas to seize German fortifications. They still secured Utah by day’s end.

The Germans were aware of the importance of the sector designated Omaha Beach, which the Allies would need to connect and secure the beachheads together, and made certain it was heavily defended. Fortifications and elevated terrain meant the American landing on Omaha would be the bloodiest that day.

The British secured Gold Beach with the help of artillery, tanks, and air support. Assuming Allied landing craft could not make it past the offshore rocks, the Germans did not defend Juno Beach as heavily. Canadian forces pushed the Germans out and secured Juno’s beachhead by mid-afternoon. Tasked with securing Sword Beach, the British were three miles from their intended objective at Caen by day’s end. Nightfall on D-Day found Allied forces past the German defenses on all five beachheads. Hitler’s vaunted Atlantic Wall lasted less than twenty-four hours.

Listen to the Historic Broadcast

A Dispatch from

Fifty years after D-Day, in 1994, Bruce Campbell bought an old cabin on Long Island. As Campbell began cleaning out the basement, he came across boxes containing what looked like movie film. He’d discovered 16 Amertapes and various parts of a Recordgraph machine.

Marching Together to Victory

Beyond overlord.

Many Allied soldiers would follow the D-Day forces into France, with the goal of breaking out of Normandy and pushing the Germans east. Allied forces found themselves bogged down in the infamous hedgerows of Normandy, walls of impenetrable vegetation that provided ideal defensive positions for the Germans and limited the Allies’ ability to move as quickly as hoped.

Frustrated with the failure of the British in the Caen sector to achieve a breakout, General Omar Bradley planned an American offensive, Operation Cobra, near Saint-Lô. If successful, the U.S. forces would be out of the dreaded hedgerows and able to maneuver rapidly. Cobra commenced on July 25 with a massive air assault against German positions. It worked, and soon the American mechanized army was on the move.

The success of Cobra is considered the end of the Normandy campaign and signaled the collapse of German defenses throughout most of France. Hastened by American landings on France’s Mediterranean coast beginning August 15 (Operation Dragoon), Allied forces by August 25 had liberated Paris. Soviet offenses from the east placed additional pressure on the Germans. Ultimate victory, the defeat of Nazi Germany, would only come after fierce fighting that lasted until the following May.

Frequently Asked Questions About D-Day

What does the d in d-day stand for.

D, which merely stands for day, is the designation used to indicate the start date of any American military operation. Military planners used plus and minus signs to designate days occurring before or after; two days before an operation commenced was indicated as D-2, three days after was D+3. An operation began on D Day and at H-Hour. While all American operations had a D-Day, the invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, is the best-known and goes down in history as such.

Why invade at Normandy?

There was enormous thought on both sides as to where the cross-Channel attack would take place. The most obvious location was in the Calais area, where the Channel is narrowest. But it was deemed too obvious. Attacking at Normandy increased the distance to travel and lengthened supply lines, but the element of surprise was considered worth the extra difficulty and risk.

What is the difference between Operation Overlord and Operation Neptune?

Operation Overlord was the code-name for the overall invasion of Normandy. Operation Neptune was the code-name for the seaborne landings and naval aspects.

How many men were killed on D-Day?

4,415: 2,502 Americans and 1,913 Allies from seven nations.

The Foundation’s necrology database is the most authoritative accounting of D-Day fallen anywhere in the world, but we know there are others. Precise record-keeping was not the priority in the heat of battle and dates were recorded incorrectly or not at all. When evidence suggests an individual was killed on June 6, 1944, our research team determines eligibility for inclusion on the Memorial wall.

Were women involved in the D-Day invasion? What about African Americans and Native Americans?

Women being ineligible for combat in 1944, no women landed on D-Day; although war correspondent Martha Gellhorn reportedly snuck onto a troop transport to cover the invasion. However, within two or three days American nurses were serving in Normandy; and the brave civilian women who acted within the French Resistance deserve recognition too.

African Americans were certainly present on D-Day, despite the racial segregation of the period. Most notable were the men of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion, which landed elements on both Utah and Omaha Beach. African Americans also acted with the quartermaster corps, as truck or bulldozer drivers, and as medics. Five African Americans are known to have given their lives on D-Day.

It is difficult to say how many Native Americans served on D-Day, because they were not always identified as such in records. But we know that members of the Comanche Tribe served as code talkers, using their native language as code unbreakable to the enemy. According to the Charles Shay Indian Memorial on Omaha Beach, about 175 American Indians invaded Omaha Beach. “Some were medics, others fought as seamen, scouts, snipers, radio operators, machine gunners, artillery gunners, combat engineers, or forward observers.”

Who were the “Bedford Boys?”

The term popularized by author Alex Kershaw’s 2003 book usually refers to soldiers from the community of Bedford, Virginia, serving in Company A, 116th Regiment who participated in the Normandy Invasion. Nineteen of those soldiers died on Omaha Beach and a twentieth Bedford native from Company F also died that day.

Why is the Memorial in Bedford?

The loss of the “Bedford Boys” is widely thought to be the highest per capita sacrifice made by any American community on D-Day. For that reason, Congress warranted the Memorial’s establishment in Bedford, Virginia, recognizing Bedford as emblematic of American homefront communities. Additionally, it is worth noting that approximately 100 other Bedford residents died during WWII in other battles and other theaters.

Is the Memorial part of the National Park Service? Does it receive government funding?

Though warranted by the United States Congress, the Memorial is not a National Park Service site. The National D-Day Memorial Foundation operates and maintains the site, with the educational mission of preserving the lessons and legacy of D-Day. The Memorial is not state or federally funded and relies on donor support. Visit our Ways to Support Us page to learn how you can support the Memorial.

Who designed and built the Memorial?

Byron Dickson – Architect

Coleman-Adams Construction – General Contractor

Jim Brothers, Matthew Kirby, Richard Pumphrey – Sculptors

Can my relative be recognized at the Memorial?

Only the names of those who died between 12:00 AM and 11:59 PM on June 6, 1944, while participating in the invasion of Normandy, are recorded on the Memorial wall. Families can honor loved ones with Memorial bricks or by purchasing a cherry tree or bench located on-site. Biographical information about Normandy veterans can be submitted to our Participant Program for inclusion in the research archive.

What is a Gold Star Family?

Gold Star Families are those American families who have lost a loved one in military service to our nation. The blue and gold star banner tradition began in World War I. A blue star indicates an active service member. A gold star denotes a service member who gave his or her life for their country.

On the west side of the Memorial grounds is a Gold Star Families Memorial Monument, a moving tribute to those families. Created by the late Hershel “Woody” Williams, the longest-surviving Medal of Honor recipient from WWII, Williams personally chose the National D-Day Memorial as the site of the first such monument in Virginia.

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University website

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Remembering D-Day: 10 Important Facts to Know

The Normandy Invasion (June 6, 1944) was the supreme joint effort of the Western Allies in Europe in World War II and remains today one of the best known campaigns of the war.

Code named Operation Overlord, it was a battle marked by its courage, meticulous planning and logistics, and audacious amphibious approach. It was also in many ways inevitable. Following Germany’s conquest of France in 1940 and declaration of war on the United States in 1941, a confrontation somewhere on the shores of Northern Europe became a waiting game, with only the date and location left to be answered.

On D-Day, over 125,000 British, American, and Canadian soldiers supported by more than five thousand ships and thirteen thousand aircraft landed in Normandy on five separate beaches in order to carve out a sixty-mile wide bridgehead. This foothold would be the launching point from which the liberation of France and Western Europe would proceed. Opposed by German units in strong defensive positions, the Allies suffered more than twelve thousand casualties on the first day of the invasion.

To commemorate the battle, Origins offers ten of the most important things to know about the invasion.

1. The Stage is Set

Map of World War II Europe. Axis Powers in red and Allies in blue.

In spring 1944, the Allied war effort had Axis forces retreating on all fronts. On the Eastern Front, Soviet forces had gained an undisputed advantage over the German Army and were advancing into Poland. The Western Allies (mainly Britain and the United States) continued their offensive in Italy, capturing Rome on June 4, while also pummeling Germany with a strategic air bombing campaign. In the Pacific, the British had just defeated a Japanese offensive in India while American forces continued a steady drive towards Japan through a series of island-hopping offensives. The long-awaited offensive to liberate Western Europe seemed imminent.

2. The Invasion was a Compromise

Churchill and Roosevelt meet in 1943 at Casablanca with their military brass to discuss military strategy including the policy of "Germany first"

The Allied effort in World War II is generally seen as the finest example of coalition warfare . Yet, the Allies rarely agreed outright, particularly in regards to D-Day. The Americans, despite lacking capability to do so, argued for an invasion in 1943. The British advocated operations in the Mediterranean and the Balkans to erode German military strength. The Soviets simply wanted a sizeable second front against the Nazis to relieve pressure on their forces. The resulting plan was a compromise that left all parties only partly satisfied, but met the strategic needs of every participant.

3. Geography Determined Where the Allies C ould Land; Allied Leaders Chose Where They W ould

The two possible landing spots for Overlord

An invasion of Europe required specific geographic features to ensure a reasonable expectation of success. The landing spot had to be within range of Allied fighters flying from England, possess large beaches for vehicular traffic, and be close to a port to supply future offensives. Only two possible landing sites fit the bill: the area known as the Pas de Calais region and the Normandy beaches. Serious planning began in 1943 with the appointment of British General Frederick Morgan as the head of a planning staff. General Morgan’s team decided on Normandy because of its lighter defenses and increased distance from German reinforcements. And they opted for one major assault designed to secure a lodgment as opposed to various smaller landings designed to deceive the Germans.

4. Allied Intelligence Successes and Failures

Allied soldiers hold aloft a dummy tank to deceive Germans

The Allies staged a massive deception campaign prior to Overlord called Operation Fortitude. Designed to confuse German intelligence, Fortitude involved the creation of fictitious formations, dummy equipment, phantom radio traffic, falsified press releases, and controlled leaks of information to known German agents. The operation was so successful German units stayed in defensive positions for weeks after D-Day awaiting the “real” invasion. Allied intelligence, however, was not infallible. The inability of intelligence analysts to identify reinforced German formations in Normandy or adequately assess the defensive strength of the hedgerow terrain behind the beaches resulted in a tougher fight for the Allies.

5. Success was Not Assured

(Top right) Lieutenant-General Frederick Morgan was the head of the planning staff for the invasion. (Bottom right) General Dwight Eisenhower gives his famous “Full victory—nothing else” speech to paratroopers just before the invasion. (Left) Eisenhower was not always so confident as seen in this letter he drafted should the operation fail.

In hindsight, the overwhelming success of the Normandy landings blinds contemporary observers to the very real fear among some Allied leaders that the invasion could fail. General Dwight Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, went so far as to draft a letter (right) to be read in the event of defeat. In it he accepted full responsibility for the failed attack despite the fact the plan was in its advanced stages when he assumed command. During the invasion, the commander of U.S. forces, General Omar Bradley, considered cancelling further landings on Omaha Beach when the success of operations ashore appeared in doubt.

6. The Pre-invasion Bombardment from Air and Naval Forces was Ineffective

The H.M.S. Warspite of Britain's Royal Navy off the coast of Normandy, bombarding possible enemy locations

Operation Neptune—the amphibious assault portion of Overlord—called for a brief but intense air and sea bombardment to precede the landings to weaken the beach defenses. Weather caused aircraft to miss targets, but more importantly the brevity of the bombardment determined it would fail. Ignoring advice from amphibious assault experts from the Pacific Theater, Allied planners opted for a short bombardment over an extended one in order to maximize surprise. The attack was far too short to do any real damage, leaving the troops in the initial waves to fight generally unaffected German defenses.

7. But Allied Air Superiority Ultimately Proved a Decisive Element in Victory

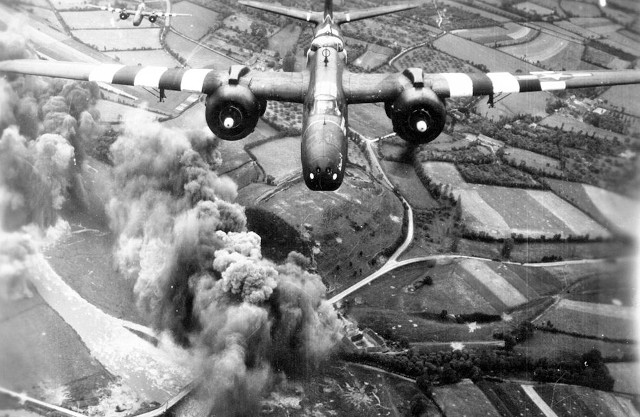

An A-20 bomber from the 416th Bomb Group of the U.S. completing its bombing run, June 1944

Prior to the invasion, Allied bombers isolated Normandy by targeting transportation hubs that could be used to move German reinforcements to the region. During the invasion, air transport units deployed over twenty thousand paratroopers, helping secure the flanks of the beachhead. Allied aircraft cleared the air and ensured the ground and naval forces proceeded unmolested from German air attacks. Following the invasion, Allied air power proved essential in delaying German reinforcements.

8. The Normandy Campaign was a Race to Reinforce the Area

Reinforcing Omaha Beach with men and equipment

The beach landings are what we think of when we imagine Overlord, but it was the question of reinforcements that won the engagement. Whichever side could gain a substantial advantage in force ratios would shift the balance in their favor. Allied efforts were limited by the size of the lodgment, the rate at which troops could be brought across the beaches, and poor weather conditions. German reinforcements, dispersed across France and the Low Countries to counter possible Allied landings, had to combat competing strategic demands and increasingly aggressive attacks from Allied air power. Allied efforts won out, and the bridgehead slowly expanded.

9. The Invasion Did Not Decide the War, But It Did Shape the Post-war World

Soviet Army photographer Yevgeny Khaldei in Berlin, Germany, May 1945 with the Brandenburg Gate in the background

Despite the remarkable achievement that was the D-Day landings, it is important to remember that they did not constitute the decisive blow against Nazi Germany; that success belongs to the Soviet Union. Raging since June 1941, the Eastern Front witnessed the most massive military confrontation in history. At the cost of more than twenty million casualties (military and civilian), the Soviet Union swallowed the Wehrmacht, occupying the majority of its military might, and inflicting almost eighty percent of all combat deaths. However, had the Normandy Invasion failed, the Soviets may have advanced deeper than they did into Germany and central Europe, moving the Iron Curtain farther west and changing the face of the Cold War.

10. D-Day is the Most Heavily Commemorated Battle in the World

From left to right: U.S. President Barack Obama, Britain’s Prince Charles, Britain’s Prime Minister Gordon Brown, Canada’s Prime Minister Stephen Harper, and France’s President Nicolas Sarkozy at the 65th anniversary ceremony (2009)

In its enduring allure and grandeur, the Normandy invasion enjoys the most prolific commemoration of any battle in the world. In addition to year-round tourist traffic, annual celebrations commemorating the invasions draw thousands of visitors. Heads of state from the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Canada, and Germany have attended in order to reflect on the feat of arms that was D-Day. Various militaries also participate, often staging commemorative parachute jumps. All this is in addition to the cemeteries in Normandy that serve as the final resting spot for thousands of American, British, Canadian, and German soldiers.

Read more from Origins on war & the military here .

D-Day: The Role in World War II Research Paper

D-day is an important historical event that happened on June 6, 1944. During World War II, allied armies suffered significant losses, and D-day, also known as the Normandy landings, or Operation Overlord, resulted in terrible human losses. This invasion became one of the hugest amphibious military actions and demanded profound planning (History.com Editors, 2019). It is essential to examine facts about D-day to understand the scale of its significance in terms of World War II.

The preparations for this military operation were extensive and witty. Several months before D-day, the Allies made German soldiers think that Pas-de-Calais was the main aim, not Normandy (History.com Editors, 2019). Many techniques were used to conduct such a deception, including false weapons. Moreover, the operation was delayed by one day because of poor weather conditions. Indeed, after the meteorologist predicted weather improvement, General Dwight Eisenhower approved the process. He motivated his soldiers with vital speeches, which became legendary. More than five thousand ships and eleven thousand aircraft were mobilized during D-day (History.com Editors, 2019). About 156,000 allied troops conquered the Normandy territories by the end of June 6, 1944. Next week the Allies stormed countryside areas, facing German opposition.

By the end of 1944, Paris was released after the Allies approached the Seine River. German armies left France, which signalized the victory (History.com Editors, 2019). Indeed, the critical fact was a significant mental crash during the Normandy invasion. It prevented Adolf Hitler from creating his Eastern Front against the Soviet armies. The Allies decided to eliminate Nazi Germany; Adolf Hitler committed suicide a week before the decision, on April 30, 1945 (History.com Editors, 2019). D-Day became a significant event that influenced the pace of World War II. Undoubtedly, many people died and suffered severe injuries during the event; however, it became an essential part of history.

History.com Editors. (2019). D-Day . History.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, April 8). D-Day: The Role in World War II. https://ivypanda.com/essays/d-day-the-role-in-world-war-ii/

"D-Day: The Role in World War II." IvyPanda , 8 Apr. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/d-day-the-role-in-world-war-ii/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'D-Day: The Role in World War II'. 8 April.

IvyPanda . 2023. "D-Day: The Role in World War II." April 8, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/d-day-the-role-in-world-war-ii/.

1. IvyPanda . "D-Day: The Role in World War II." April 8, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/d-day-the-role-in-world-war-ii/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "D-Day: The Role in World War II." April 8, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/d-day-the-role-in-world-war-ii/.

- Intelligence, War and International Relations

- The Events and Importance of the Battle of Carentan

- Crowdfunding Project on Kickstarter

- The Second World War Choices Made in 1940

- The World War II Propaganda Techniques

- What Role Did India Play in the Second World War?

- Could the US Prevent the Start of World War II?

- World War Two and Its Ramifications

European journal of American studies

Home Issues 7-2 The Many Meanings of D-Day

The Many Meanings of D-Day

This essay investigates what D-Day has symbolized for Americans and how and why its meaning has changed over the past six decades. While the commemoration functions differently in U.S. domestic and foreign policies, in both cases it has been used to mark new beginnings. Ronald Reagan launched his “morning again in America” 1984 re-election campaign from the Pointe du Hoc, and the international commemorations on the Normandy beaches since 1990 have been occasions to display the changing face of Europe and the realignment of allies.

Index terms

Keywords: .

1 For Americans, June 6, 1944 “D-Day” has come to symbolize World War II, with commemorations at home and abroad. How did this date come to assume such significance and how have the commemorations changed over the 65 years since the Normandy landings? How does D-Day function in U.S. cultural memory and in domestic politics and foreign policy? This paper will look at some of the major trends in D-Day remembrances, particularly in international commemorations and D-Day’s meaning in U.S. and Allied foreign policy. Although war commemorations are ostensibly directed at reflecting on the hallowed past, the D-Day observances, particularly since the 1980s, have also marked new beginnings in both domestic and foreign policy.

2 As the invasion was taking place in June 1944, there was, of course, a great deal of coverage in the U.S. media. The events in Normandy, however, shared the June headlines with other simultaneous developments on the European front including the fall of Rome. 1

1. Early Years

3 The very first anniversary of the D-Day landings was marked on June 6, 1945 by a holiday for the Allied forces. In his message to the troops announcing the holiday General Eisenhower stated that “formal ceremonies would be avoided.” 2

4 By the time the invasion’s fifth anniversary rolled around in 1949 the day was marked by a “colorful but modest memorial service” at the beach. The U.S. was represented at the event by the military attaché and the naval attaché of the U.S. Embassy in Paris. A French naval guard, a local bugle corps and an honor guard from an American Legion Post in Paris all took part. A pair of young girls from the surrounding villages placed wreaths on the beach, and a U.S. Air Force Flying Fortresses passed over, firing rockets and dropping flowers. 3

5 The anniversaries of the early 1950s reflected the tenor of the times, evoking both the economic and military Cold War projects of the U.S. in Europe: the Marshall Plan and NATO. Barry Bingham, head of the Marshall Plan Mission in France, used the occasion of the 1950 D-Day commemoration ceremony to praise France’s postwar recovery efforts. 4 Held in the middle of the Korean War, the 1952 D-Day commemoration at Utah Beach proved an opportunity for General Matthew D. Ridgway, Supreme Commander Allied Forces in Europe and a D-Day veteran, to speak of U.S. purpose in the Cold War against “a new and more fearful totalitarianism.” He warned the Communist powers not to “underestimate our resolve to live as free men in our own territories….We will gather the strength we have pledged to one another and set it before our people and our lands as a protective shield until reason backed by strength halts further aggression….” Referring to both his status as a D-Day participant and his current role as military commander of NATO, Ridgway pledged: “The last time I came here, I came as one of thousands to wage war. This time I come to wage peace.” 5

6 The tenth anniversary of the D-Day landings found President Dwight Eisenhower, who as Commander of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) had led the Normandy invasion, strolling through a wheat field in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. 6 Eisenhower sent a statement to be read at the Utah Beach commemoration ceremony by the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. who was the President’s personal representative at the anniversary events. In contrast to the bellicose remarks of General Ridgway a few years earlier, Eisenhower in 1954 expressed “profound regret” that all of “the members of the Grand Alliance have not maintained in time of peace the spirit of that wartime union.” Eisenhower used this anniversary occasion to recall “my pleasant association with the outstanding Soviet Soldier, Marshall Zhukov, and the victorious meeting at the Elbe of the armies of the West and of the East.” 7 A decade later, in preparation for the twentieth anniversary of the D-Day landings, Eisenhower, no longer president, returned to the Normandy beaches in 1963 to film a D-Day TV special for CBS. 8

7 In between the tenth and twentieth anniversaries, U.S. domestic interest in the Normandy landings had been stoked by Cornelius Ryan’s 1959 best-seller The Longest Day and the 1962 Hollywood epic that Darryl F. Zanuck produced based on Ryan’s book. The film was also notable for giving separate attention to the contributions of the British and Canadian forces as well as those of the French Resistance. The German actions in Normandy were depicted without demonization. Leading German actors (speaking German) gave voice to the professional military’s criticism of Hitler’s leadership. This empathetic portrayal was an indication perhaps of West Germany’s position in the NATO alliance. Clocking in at 178 minutes and shot in black and white for a documentary feel, The Longest Day boasted a cast that was a Who’s-who of British and American male stars of the era: John Wayne, Henry Fonda, Robert Mitchum, Richard Burton, Peter Lawford, Sean Connery, Richard Beymer, Red Buttons, Eddie Albert, and teen heart-throbs Fabian, Paul Anka, Tommy Sands and Sal Mineo. This display of bold-face names served to undercut the film’s intended documentary effect as their presence constantly reminded the viewers that they were watching a Hollywood production. Critics pointed out that Zanuck’s attention to period detail in weapons, equipment and language did not carry through to a realistic depiction of combat death and casualties—a charge that could not be laid against Steven Spielberg for Saving Private Ryan a 1998 Hollywood D-Day block-buster . 9

8 In spite of this heightened public interest in D-Day, U.S. President Lyndon Johnson, absorbed in both his ambitious domestic agenda—including trying to secure passage of the Civil Rights Act-- and the Vietnam War, did not travel to Normandy for the twentieth anniversary. Instead he sent General Omar N. Bradley, one of the commanders of the 1944 landings. 10

9 For the twenty-fifth anniversary in 1969 President Richard Nixon, focused on Vietnam, issued a boilerplate proclamation, calling the Allied landings in 1944 “‘a historical landmark in the history of freedom.’” 11 When the time came for the thirtieth anniversary of D-Day in 1974, Nixon again was too preoccupied to travel to Normandy. Congress had already begun impeachment hearings against him on charges of obstruction of justice, abuse of power and contempt of Congress arising from the Watergate affair. Nixon would resign in August 1974, and Presidential attention for the rest of the 1970s was directed at the aftermath of Vietnam and at new crisis like those involving the U.S. economy, energy, and the seizing of the U.S. Embassy in Teheran. The moment for actively reinvigorating the memory of World War II had not yet arrived.

10 As the G-7 leaders 12 gathered in Paris for their meetings at Versailles in early June 1982, President Ronald Reagan made D-Day the focus of his radio broadcast to U.S. audiences on June 5. He also prepared taped remarks on D-Day for broadcast on French television. 13 Although the President himself did not travel to the landing sites in 1982, U.S. First Lady Nancy Reagan paid a three-hour visit to Normandy to mark the thirty-eighth anniversary of D-Day. 14 Accompanied by the Defense and Army attachés of the U.S. Embassy in Paris, she laid a wreath at the memorial statue in the U.S. cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer and made some brief remarks to a small crowd: “If my husband were here today, he would tell you how deeply he feels the responsibilities of peace and freedom. He would tell you how we can best insure that other young men on other beaches and other fields will not have to die. And I think he would tell you of his ideas for nuclear peace.” 15

2. “Morning Again in America”

11 Two years later on the fortieth anniversary of D-Day in June 1984 her husband President Ronald Reagan would get the chance to personally address those gathered to commemorate the Normandy invasion. But this time the crowd was no longer small. Speaking at the Ranger Monument at Pointe du Hoc at 1:20 p.m. (timed to coincide with the morning TV programs on the U.S. East Coast and designed as part of Reagan’s re-election campaign) President Reagan delivered his now-famous “boys of Pointe du Hoc” address to a television audience of millions as well as to the veterans and Allied leaders gathered on the Normandy coast. In remarks carefully crafted by Peggy Noonan, Reagan first paid tribute to the Ranger veterans, recreating dramatically their heroic deeds in scaling the cliffs: “They climbed, shot back, and held their footing. Soon, one by one, the Rangers pulled themselves over the top, and in seizing the firm land at the top of these cliffs, they began to seize back the continent of Europe. Two hundred and twenty-five came here. After two days of fighting, only ninety could still bear arms.” He went on to pay tribute to the Allies, mentioning by name “the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, Poland's 24th Lancers, the Royal Scots Fusiliers, the Screaming Eagles, the Yeomen of England's armored divisions, the forces of Free France, the Coast Guard's ‘Matchbox Fleet’ and you, the American Rangers.” Not leaving out Germany and Italy, Reagan spoke of the reconciliation with former enemies “all of whom had suffered so greatly. The United States did its part, creating the Marshall plan to help rebuild our allies and our former enemies. The Marshall plan led to the Atlantic alliance -- a great alliance that serves to this day as our shield for freedom, for prosperity, and for peace.” Toward the Russians, Reagan presented two faces. 16 First, he lamented: “Some liberated countries were lost. The great sadness of this loss echoes down to our own time in the streets of Warsaw, Prague, and East Berlin. Soviet troops that came to the center of this continent did not leave when peace came. They're still there, uninvited, unwanted, unyielding, almost 40 years after the war.” Then he added: “It's fitting to remember here the great losses also suffered by the Russian people during World War II: 20 million perished…. We look for some sign from the Soviet Union that they are willing to move forward, that they share our desire and love for peace, and that they will give up the ways of conquest.” After his remarks he unveiled two memorial plaques honoring the Rangers. 17

12 The Pointe du Hoc speech served as the opening salvo in Reagan’s “morning again in America” re-election campaign. Using snippets from this speech in a popular television advertisement, the campaign transformed a look back at a forty-year-old battle into a new beginning for the nation. 18

13 A few hours after the Pointe du Hoc speech Reagan gave another address on Omaha Beach, this time paying special tribute to the efforts of the French Resistance, directing his remarks at President Mitterrand, who had participated in the Resistance. “Your valiant struggle for France did so much to cripple the enemy and spur the advance of the armies of liberation. The French Forces of the Interior will forever personify courage and national spirit.” Reminding Americans and Europeans of the importance of postwar efforts like NATO, he concluded: “Our alliance, forged in the crucible of war, tempered and shaped by the realities of the postwar world, has succeeded. In Europe, the threat has been contained, the peace has been kept.” 19

14 Later that same day President Reagan joined President Mitterrand and other Allied leaders (Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, Queen Beatrix of The Netherlands, King Olav V of Norway, King Baudouin I of Belgium, Grand Duke Jean of Luxembourg, and Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau of Canada) at Utah Beach. Mitterrand’s remarks stressed reconciliation with Germany: “‘the adversaries of yesterday are reconciled and are building the Europe of freedom.’” 20 Chancellor Helmut Kohl had not been invited to the ceremonies, but the day’s events and speeches buttressed a NATO alliance that included (West) Germany.

15 This emphasis on the continuing importance of the NATO alliance was far from accidental. There are been widespread protests in Europe in 1984 over the installation of U.S. Cruise and Pershing missiles in accordance with a 1979 NATO decision. The “family portrait” of the assembled Allies on Utah Beach and the tribute to their absent member Germany sent a signal to publics on both sides of the Atlantic about the continuing commitment to joint defense of “the Europe of freedom.” The 1984 celebrations set a new standard for D-Day commemorations and established a pattern that would be followed (with variations) for the next twenty-five years. By looking at these variations in subsequent years we can monitor changes in transatlantic relations.

3. A New Europe

16 By the time of the fiftieth anniversary of D-Day the map of Europe had shifted once again. The Warsaw Pact had dissolved; Germany had reunited; Czechoslovakia had split; the Soviet Union was no more. In June 1994 leaders of all the countries that had participated in the invasion gathered at Normandy: Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, the UK and the U.S. and this year for the first time leaders of Poland and the Czech Republic and Slovakia—a visible symbol of the changed faced of Europe since 1989 and yet another new beginning for the continent. In addition the year marked a generational shift, with the U.S. represented in Normandy by President Clinton who had been born after the end of World War II.

- 22 Jeffrey Birnbaum, “Reporter’s Notebook: Clinton, Facing Comparison with Reagan’s D-Day Speech Rise (...)

17 Clinton, of course, had a hard act to follow given the iconic status that Reagan’s “boys of Pointe du Hoc” speech had attained over the past decade. He also had the disadvantage of never having served in the military and of having famously avoided serving in the Vietnam War. In a new wrinkle to D-Day celebrations, Clinton, along with Queen Elizabeth and other Allied leaders, sailed from Portsmouth, England to the French coast in a “massive flotilla” accompanied by Lancaster bombers to recreate and commemorate the 1944 invasion. 21 In France Clinton participated in four ceremonies marking the anniversary of the landings. In his address at the American cemetery he turned his seeming disadvantage of lack of WWII experience into an advantage as he stressed the ties between generations: “‘We are the children of your sacrifice,’” he told the veterans of D-Day. “‘The flame of your youth became freedom's lamp, and we see its light reflected in your faces still, and in the faces of your children and grandchildren…. We commit ourselves, as you did, to keep that lamp burning for those who will follow. You completed your mission here. But the mission of freedom goes on; the battle continues. The `longest day' is not yet over.’” 22

18 D-Day anniversaries were not only occasions for major political gatherings and speeches, but had also become important tourist attractions and income generators for Western Europe, especially France, with Normandy hotels and guest houses fully booked for early June. In 1994 France alone hosted more than 350 events commemorating the D-Day landings. Many specialized tours were designed for veterans and their families. The QE2 even offered a cruise to Cherbourg featuring 1940s big bands, Vera Lynn and Bob Hope. 23 Across the Channel, thousands of veterans and their families were also welcomed at anniversary events in England. 24