An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Gen Intern Med

- v.37(1); 2022 Jan

Methods for Identifying Health Research Gaps, Needs, and Priorities: a Scoping Review

Eunice c. wong.

1 RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA USA

Alicia R. Maher

Aneesa motala.

2 Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, University of Southern California Gehr Family Center for Health Systems Science & Innovation, Los Angeles, USA

Rachel Ross

Olamigoke akinniranye, jody larkin, susanne hempel, associated data.

Well-defined, systematic, and transparent processes to identify health research gaps, needs, and priorities are vital to ensuring that available funds target areas with the greatest potential for impact.

The purpose of this review is to characterize methods conducted or supported by research funding organizations to identify health research gaps, needs, or priorities.

We searched MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and the Web of Science up to September 2019. Eligible studies reported on methods to identify health research gaps, needs, and priorities that had been conducted or supported by research funding organizations. Using a published protocol, we extracted data on the method, criteria, involvement of stakeholders, evaluations, and whether the method had been replicated (i.e., used in other studies).

Among 10,832 citations, 167 studies were eligible for full data extraction. More than half of the studies employed methods to identify both needs and priorities, whereas about a quarter of studies focused singularly on identifying gaps (7%), needs (6%), or priorities (14%) only. The most frequently used methods were the convening of workshops or meetings (37%), quantitative methods (32%), and the James Lind Alliance approach, a multi-stakeholder research needs and priority setting process (28%). The most widely applied criteria were importance to stakeholders (72%), potential value (29%), and feasibility (18%). Stakeholder involvement was most prominent among clinicians (69%), researchers (66%), and patients and the public (59%). Stakeholders were identified through stakeholder organizations (51%) and purposive (26%) and convenience sampling (11%). Only 4% of studies evaluated the effectiveness of the methods and 37% employed methods that were reproducible and used in other studies.

To ensure optimal targeting of funds to meet the greatest areas of need and maximize outcomes, a much more robust evidence base is needed to ascertain the effectiveness of methods used to identify research gaps, needs, and priorities.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-021-07064-1.

Well-defined, systematic, and transparent methods to identify health research gaps, needs, and priorities are vital to ensuring that available funds target areas with the greatest potential for impact. 1 , 2 As defined in the literature, 3 , 4 research gaps are defined as areas or topics in which the ability to draw a conclusion for a given question is prevented by insufficient evidence. Research gaps are not necessarily synonymous with research needs , which are those knowledge gaps that significantly inhibit the decision-making ability of key stakeholders, who are end users of research, such as patients, clinicians, and policy makers. The selection of research priorities is often necessary when all identified research gaps or needs cannot be pursued because of resource constraints. Methods to identify health research gaps, needs, and priorities (from herein referred to as gaps, needs, priorities) can be multi-varied and there does not appear to be general consensus on best practices. 3 , 5

Several published reviews highlight the diverse methods that have been used to identify gaps and priorities. In a review of methods used to identify gaps from systematic reviews, Robinson et al. noted the wide range of organizing principles that were employed in published literature between 2001 and 2009 (e.g., care pathway, decision tree, and patient, intervention, comparison, outcome framework,). 6 In a more recent review spanning 2007 to 2017, Nyanchoka et al. found that the vast majority of studies with a primary focus on the identification of gaps (83%) relied solely on knowledge synthesis methods (e.g., systematic review, scoping review, evidence mapping, literature review). A much smaller proportion (9%) relied exclusively on primary research methods (i.e., quantitative survey, qualitative study). 7

With respect to research priorities, in a review limited to a PubMed database search covering the period from 2001 to 2014, Yoshida documented a wide range of methods to identify priorities including the use of not only knowledge synthesis (i.e., literature reviews) and primary research methods (i.e., surveys) but also multi-stage, structured methods such as Delphi, Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative (CHNRI), James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership (JLA PSP), and Essential National Health Research (ENHR). 2 The CHNRI method, originally developed for the purpose of setting global child health research priorities, typically employs researchers and experts to specify a long list of research questions, the criteria that will be used to prioritize research questions, and the technical scoring of research questions using the defined criteria. 8 During the latter stages, non-expert stakeholders’ input are incorporated by using their ratings of the importance of selected criteria to weight the technical scores. The ENHR method, initially designed for health research priority setting at the national level, involves researchers, decision-makers, health service providers, and communities throughout the entire process of identifying and prioritizing research topics. 9 The JLA PSP method convenes patients, carers, and clinicians to equally and jointly identify questions about healthcare that cannot be answered by existing evidence that are important to all groups (i.e., research needs). 10 The identified research needs are then prioritized by the groups resulting in a final list (often a top 10) of research priorities. Non-clinical researchers are excluded from voting on research needs or priorities but can be involved in other processes (e.g., knowledge synthesis). CHNRI, ENHR, and JLA PSP usually employ a mix of knowledge synthesis and primary research methods to first identify a set of gaps or needs that are then prioritized. Thus, even though CHNRI, ENHR, and JLA PSP have been referred to as priority setting methods, they actually consist of a gaps or needs identification stage that feeds into a research prioritization stage.

Nyanchoka et al.’s review found that the majority of studies focused on the identification of gaps alone (65%), whereas the remaining studies focused either on research priorities alone (17%) or on both gaps and priorities (19%). 7 In an update to Robinson et al.’s review, 6 Carey et al. reviewed the literature between 2010 and 2011 and observed that the studies conducted during this latter period of time focused more on research priorities than gaps and had increased stakeholder involvement, and that none had evaluated the reproducibility of the methods. 11

The increasing development and diversity of formal processes and methods to identify gaps and priorities are indicative of a developing field. 2 , 12 To facilitate more standardized and systematic processes, other important areas warrant further investigation. Prior reviews did not distinguish between the identification of gaps versus research needs. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Evidence-based Practice Center (AHRQ EPC) Program issued a series of method papers related to establishing research needs as part of comparative effectiveness research. 13 – 15 The AHRQ EPC Program defined research needs as “evidence gaps” identified within systematic reviews that are prioritized by stakeholders according to their potential impact on practice or care. 16 Furthermore, Nyanchoka et al. relied on author designations to classify studies as focusing on gaps versus research priorities and noted that definitions of gaps varied across studies, highlighting the need to apply consistent taxonomy when categorizing studies in reviews. 7 Given the rise in the use of stakeholders in both gaps and prioritization exercises, a greater understanding of the range of practices involving stakeholders is also needed. This includes the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders (e.g., consultants versus final decision-makers), the composition of stakeholders (e.g., non-research clinicians, patients, caregivers, policymakers), and the methods used to recruit stakeholders. The lack of consensus of best practices also highlights the importance of learning the extent to which evaluations to determine the effectiveness of gaps, needs, and prioritization exercises have been conducted, and if so, what were the resultant outcomes.

To better inform efforts and organizations that fund health research, we conducted a scoping review of methods used to identify gaps, needs, and priorities that were linked to potential or actual health research funding decision-making. Hence, this scoping review was limited to studies in which the identification of health research gaps, needs, or priorities was supported or conducted by funding organizations to address the following questions 1 : What are the characteristics of methods to identify health research gaps, needs, and priorities? and 2 To what extent have evaluations of the impact of these methods been conducted? Given that scoping reviews may be executed to characterize the ways an area of research has been conducted, 17 , 18 this approach is appropriate for the broad nature of this study’s aims.

Protocol and Registration

We employed methods that conform to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews. 19 See Appendix A in the Supplementary Information. The scoping review protocol is registered with the Open Science Framework ( https://osf.io/5zjqx/ ).

Eligibility Criteria

Studies published in English that described methods to identify health research gaps, needs, or priorities that were supported or conducted by funding organizations were eligible for inclusion. We excluded studies that reported only the results of the exercise (e.g., list of priorities) absent of information on the methods used. We also excluded studies involving evidence synthesis (e.g., literature or systematic reviews) that were solely descriptive and did not employ an explicit method to identify research gaps, needs, or priorities.

Information Sources and Search Strategy

We searched the following electronic databases: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. Our database search also included an update of the Nyanchoka et al. scoping review, which entailed executing their database searches for the time period following 2017 (the study’s search end date). 7 Nyanchoka et al. did not include database searches for research needs. The electronic database search and scoping review update were completed in August and September 2019, respectively . The search strategy employed for each of the databases is presented in Appendix B in the Supplementary Information.

Selection of Sources of Evidence and Data Charting Process

Two reviewers screened titles and abstracts and full-text publications. Citations that one or both reviewers considered potentially eligible were retrieved for full-text review. Relevant background articles and scoping and systematic reviews were reference mined to screen for eligible studies. Full-text publications were screened against detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data was extracted by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion by the review team.

Information on study characteristics were extracted from each article including the aims of the exercise (i.e., gaps, needs, priorities, or a combination) and health condition (i.e., physical or psychological). Based on definitions in the literature, 3 – 5 the aims of the exercise were coded according to the activities that were conducted, which may not have always corresponded with the study authors’ labeling of the exercises. For instance, the JLA PSP method is often described as a priority exercise but we categorized it as a needs and priority exercise. Priority exercises can be preceded by exercises to identify gaps or needs, which then feed into the priority exercise such as in JLA PSP; however, standalone priority exercises can also be conducted (e.g., stakeholders prioritize an existing list of emerging diseases).

For each type of exercise, information on the methods were recorded. An initial list of methods was created based on previous reviews. 9 , 12 , 20 During the data extraction process, any methods not included in the initial list were subsequently added. If more than one exercise was reported within an article (e.g., gaps and priorities), information was extracted for each exercise separately. Reviewers extracted the following information: methods employed (e.g., qualitative, quantitative), criteria used (e.g., disease burden, importance to stakeholders), stakeholder involvement (e.g., stakeholder composition, method for identifying stakeholders), and whether an evaluation was conducted on the effectiveness of the exercise (see Appendix C in the Supplementary Information for full data extraction form).

Synthesis of results entailed quantitative descriptives of study characteristics (e.g., proportion of studies by aims of exercise) and characteristics of methods employed across all studies and by each type of study (e.g., gaps, needs, priorities).

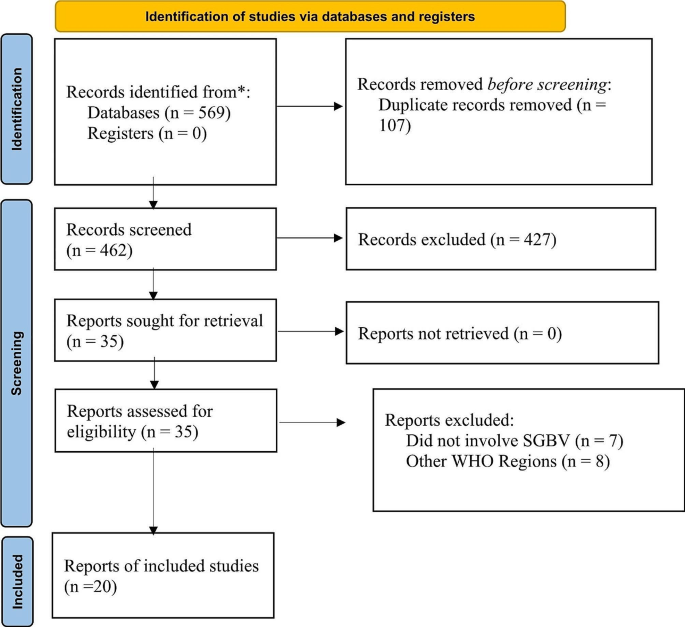

The electronic database search yielded a total of 10,548 titles. Another 284 articles were identified after searching the reference lists of full-text publications, including three systematic reviews 21 – 23 and one scoping review 24 that had met eligibility criteria. Moreover, a total of 99 publications designated as relevant background articles were also reference mined to screen for eligible studies. We conducted full-text screening for 2524 articles, which resulted in 2344 exclusions (440 studies were designated as background articles). A total of 167 exercises related to the identification of gaps, needs, or priorities that were supported or conducted by a research funding organization were described across 180 publications and underwent full data extraction. See Figure Figure1 1 for the flow diagram of our search strategy and reasons for exclusion.

Literature flow

Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

Among the published exercises, the majority of studies (152/167) conducted gaps, need, or prioritization exercises related to physical health, whereas only a small fraction of studies focused on psychological health (12/167) (see Appendix D in the Supplementary Information).

Methods for Identifying Gaps, Needs, and Priorities

As seen in Table Table1, 1 , only about a quarter of studies involved a singular type of exercise with 7% focused on the identification of gaps only (i.e., areas with insufficient information to draw a conclusion for a given question), 6% on needs only (i.e., knowledge gaps that inhibit the decision-making of key stakeholders), and 14% priorities only (i.e., ranked gaps or needs often because of resource constraints). Studies more commonly conducted a combination of multiple types of exercises with more than half focused on the identification of both research needs and priorities, 14% on gaps and priorities, 3% gaps, needs, and priorities, and 3% gaps and needs.

Methods for Identifying Health Research Gaps, Needs, and Priorities

JLA PSP , James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnerships; ENHR , Essential National Health Research; CHNRI , Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative. Numbers in columns may add up to more than the total N or 100% since some studies employed more than one method

Across the 167 studies, the three most frequently used methods were the convening of workshops/meetings/conferences (37%), quantitative methods (32%), and the JLA PSP approach (28%). This was followed by methods involving literature reviews (17%), qualitative methods (17%), consensus methods (13%), and reviews of source materials (15%). Other methods included the CHNRI process (7%), reviews of in-progress data (7%), consultation with (non-researcher) stakeholders (4%), applying a framework tool (4%), ENHR (1%), systematic reviews (1%), and evidence mapping (1%).

The criterion most widely applied across the 167 studies was the importance to stakeholders (72%) (see Table Table2). 2 ). Almost one-third (29%) considered the potential value and 18% feasibility as criteria. Burden of disease (9%), addressing inequities (8%), costs (6%), alignment with organization’s mission (3%), and patient centeredness (2%) were adopted as criteria to a lesser extent.

Criteria for Identifying Health Research Gaps, Needs, and Priorities

Numbers in columns may add up to more than the total N or 100% since some studies employed more than one criterion

About two-thirds of the studies included researchers (66%) and clinicians (69%) as stakeholders (see Appendix E in the Supplementary Information). Patients and the public were involved in 59% of the studies. A smaller proportion included policy makers (20%), funders (13%), product makers (8%), payers (5%), and purchasers (2%) as stakeholders. Nearly half of the studies (51%) relied on stakeholder organizations to identify stakeholders (see Appendix F in the Supplementary Information). A quarter of studies (26%) used purposive sampling and some convenience sampling (11%). Few (9%) used snowball sampling to identify stakeholders. Only a minor fraction of studies, seven of the 167 (4%), reported some type of effectiveness evaluation. 25 – 31

Our scoping review revealed that approaches to identifying gaps, needs, and priorities are less likely to occur as discrete processes and more often involve a combination of exercises. Approaches encompassing multiple exercises (e.g., gaps and needs) were far more prevalent than singular standalone exercises (e.g., gaps only) (73% vs. 27%). Findings underscore the varying importance placed on gaps, needs, and priorities, which reflect key principles of the Value of Information approach (i.e., not all gaps are important, addressing gaps do not necessarily address needs nor does addressing needs necessarily address priorities). 32

Findings differ from Nyanchoka et al.’s review in which studies involving the identification of gaps only outnumbered studies involving both gaps and priorities. 7 However, Nyanchoka et al. relied on author definitions to categorize exercises, whereas our study made designations based on our review of the activities described in the article and applied definitions drawn from the literature. 3 , 4 Lack of consensus on definitions of gaps and priority setting has been noted in the literature. 33 , 34 To the authors’ knowledge, no prior scoping review has focused on methods related to the identification of “research needs.” Findings underscore the need to develop and apply more consistent taxonomy to this growing field of research.

More than 40% of studies employed methods with a structured protocol including JLA PSP, ENHR, CHRNI, World Café, and the Dialogue model. 10 , 35 – 40 The World Café and Dialogue models particularly value the experiential perspectives of stakeholders. The World Café centers on creating a special environment, often modeled after a café, in which rounds of multi-stakeholder, small group, conversations are facilitated and prefaced with questions designed for the specific purpose of the session. Insights and results are reported and shared back to the entire group with no expectation to achieve consensus, but rather diverse perspectives are encouraged. 36 The Dialogue model is a multi-stakeholder, participatory, priority setting method involving the following phases: exploratory (informal discussions), consultation (separate stakeholder consultations), prioritization (stakeholder ratings), and integration (dialog between stakeholders). 39 Findings may indicate a trend away from non-replicable methods to approaches that afford greater transparency and reproducibility. 41 For instance, of the 17 studies published between 2000 and 2009, none had employed CHNRI and 6% used JLA PSP compared to the 141 studies between 2010 and 2019 in which 8% applied CHNRI and 32% JLA PSP. However, notable variations in implementing CHNRI and JLA PSP have been observed. 41 – 43 Though these protocols help to ensure a more standardized process, which is essential when testing the effectiveness of methods, such evaluations are infrequent but necessary to establish the usefulness of replicable methods.

Convening workshops, meetings, or conferences was the method used by the greatest proportion of studies (37%). The operationalization of even this singular method varied widely in duration (e.g., single vs. multi-day conferences), format (e.g., expert panel presentations, breakout discussion groups), processes (e.g., use of formal/informal consensus methods), and composition of stakeholders. The operationalization of other methods (e.g., quantitative, qualitative) also exhibited great diversity.

The use of explicit criteria to determine gaps, needs, or priorities is a key component of certain structured protocols 40 , 44 and frameworks. 9 , 45 In our scoping review, the criterion applied most frequently across studies (71%) was “importance to stakeholders” followed by potential value (31%) and feasibility (18%). Stakeholder values are being incorporated into the identification of gaps, needs, and exercises across a significant proportion of studies, but how this is operationalized varies widely across studies. For instance, the CHNRI typically employs multiple criteria that are scored by technical experts and these scores are then weighted based on stakeholder ratings of their relative importance. Other studies totaled scores across multiple criteria, whereas JLA PSP asks multiple stakeholders to rank the top ten priorities. The importance of involving stakeholders, especially patients and the public, in priority setting is increasingly viewed as vital to ensuring the needs of end users are met, 46 , 47 particularly in light of evidence demonstrating mismatches between the research interests of patients and researchers and clinicians. 48 – 50 In our review, clinicians (69%) and researchers (66%) were the most widely represented stakeholder groups across studies. Patients and the public (e.g., caregivers) were included as stakeholders in 59% of the studies. Only a small fraction of studies involved exercises in which stakeholders were limited to researchers only. Patients and the public were involved as stakeholders in 12% of studies published between 2000 and 2009 compared to 60% of studies between 2010 and 2019. Findings may reflect a trend away from researchers traditionally serving as one of the sole drivers of determining which research topics should be pursued.

More than half of the studies reported relying on stakeholder organizations to identify participants. Partnering with stakeholder organizations has been noted as one of the primary methods for identifying stakeholders for priority setting exercises. 34 Purposive sampling was the next most frequently used stakeholder identification method. In contrast, convenience sampling (e.g., recommendations by study team) and snowball sampling (e.g., identified stakeholders refer other stakeholders who then refer additional stakeholders) were not as frequently employed, but were documented as common methods in a prior review conducted almost a decade ago. 14 The greater use of stakeholder organizations than convenience or snowball sampling may be partly due to the more recent proliferation of published studies using structured protocols like JLA PSP, which rely heavily on partnerships with stakeholder organizations. Though methods such as snowball sampling may introduce more bias than random sampling, 14 there are no established best practices for stakeholder identification methods. 51 Nearly a quarter of studies provided either unclear or no information on stakeholder identification methods, which has been documented as a barrier to comparing across studies and assessing the validity of research priorities. 34

Determining the effectiveness of gaps, needs, and priority exercises is challenging given that outcome evaluations are rarely conducted. Only seven studies reported conducting an evaluation. 25 – 31 Evaluations varied with respect to their focus on process- (e.g., balanced stakeholder representation, stakeholder satisfaction) versus outcome-related impact (e.g., prioritized topics funded, knowledge production, benefits to health). There is no consensus on what constitutes optimal outcomes, which has been found to vary by discipline. 52

More than 90% of studies involved exercises related to physical health in contrast to a minor portfolio of work being dedicated to psychological health, which may be an indication of the low priority placed on psychological health policy research. Understanding whether funding decisions for physical versus psychological health research are similarly or differentially governed by more systematic, formal processes may be important to the extent that this affects the effective targeting of funds.

Limitations

By limiting studies to those supported or conducted by funding organizations, we may have excluded global, national, or local priority setting exercises. In addition, our scoping review categorized approaches according to the actual exercises conducted and definitions provided in the scientific literature rather than relying on the terminology employed by studies. This resulted in instances in which the category assigned to an exercise within our scoping review could diverge from the category employed by the study authors. Lastly, this study’s findings are subject to limitations often characteristic of scoping reviews such as publication bias, language bias, lack of quality assessment, and search, inclusion, and extraction biases. 53

Conclusions

The diversity and growing establishment of formal processes and methods to identify health research gaps, needs, and priorities are characteristic of a developing field. Even with the emergence of more structured and systematic approaches, the inconsistent categorization and definition of gaps, needs, and priorities inhibit efforts to evaluate the effectiveness of varied methods and processes, such efforts are rare and sorely needed to build an evidence base to guide best practices. The immense variation occurring within structured protocols, across different combinations of disparate methods, and even within singular methods, further emphasizes the importance of using clearly defined approaches, which are essential to conducting investigations of the effectiveness of these varied approaches. The recent development of reporting guidelines for priority setting for health research may facilitate more consistent and clear documentation of processes and methods, which includes the many facets of involving stakeholders. 34 To ensure optimal targeting of funds to meet the greatest areas of need and maximize outcomes, a much more robust evidence base is needed to ascertain the effectiveness of methods used to identify research gaps, needs, and priorities.

(PDF 1205 kb)

Acknowledgements

This scoping review is part of research that was sponsored by Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury (now Psychological Health Center of Excellence).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The Research Gap (Literature Gap)

Everything you need to know to find a quality research gap

By: Ethar Al-Saraf (PhD) | Expert Reviewed By: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | November 2022

If you’re just starting out in research, chances are you’ve heard about the elusive research gap (also called a literature gap). In this post, we’ll explore the tricky topic of research gaps. We’ll explain what a research gap is, look at the four most common types of research gaps, and unpack how you can go about finding a suitable research gap for your dissertation, thesis or research project.

Overview: Research Gap 101

- What is a research gap

- Four common types of research gaps

- Practical examples

- How to find research gaps

- Recap & key takeaways

What (exactly) is a research gap?

Well, at the simplest level, a research gap is essentially an unanswered question or unresolved problem in a field, which reflects a lack of existing research in that space. Alternatively, a research gap can also exist when there’s already a fair deal of existing research, but where the findings of the studies pull in different directions , making it difficult to draw firm conclusions.

For example, let’s say your research aims to identify the cause (or causes) of a particular disease. Upon reviewing the literature, you may find that there’s a body of research that points toward cigarette smoking as a key factor – but at the same time, a large body of research that finds no link between smoking and the disease. In that case, you may have something of a research gap that warrants further investigation.

Now that we’ve defined what a research gap is – an unanswered question or unresolved problem – let’s look at a few different types of research gaps.

Types of research gaps

While there are many different types of research gaps, the four most common ones we encounter when helping students at Grad Coach are as follows:

- The classic literature gap

- The disagreement gap

- The contextual gap, and

- The methodological gap

Need a helping hand?

1. The Classic Literature Gap

First up is the classic literature gap. This type of research gap emerges when there’s a new concept or phenomenon that hasn’t been studied much, or at all. For example, when a social media platform is launched, there’s an opportunity to explore its impacts on users, how it could be leveraged for marketing, its impact on society, and so on. The same applies for new technologies, new modes of communication, transportation, etc.

Classic literature gaps can present exciting research opportunities , but a drawback you need to be aware of is that with this type of research gap, you’ll be exploring completely new territory . This means you’ll have to draw on adjacent literature (that is, research in adjacent fields) to build your literature review, as there naturally won’t be very many existing studies that directly relate to the topic. While this is manageable, it can be challenging for first-time researchers, so be careful not to bite off more than you can chew.

2. The Disagreement Gap

As the name suggests, the disagreement gap emerges when there are contrasting or contradictory findings in the existing research regarding a specific research question (or set of questions). The hypothetical example we looked at earlier regarding the causes of a disease reflects a disagreement gap.

Importantly, for this type of research gap, there needs to be a relatively balanced set of opposing findings . In other words, a situation where 95% of studies find one result and 5% find the opposite result wouldn’t quite constitute a disagreement in the literature. Of course, it’s hard to quantify exactly how much weight to give to each study, but you’ll need to at least show that the opposing findings aren’t simply a corner-case anomaly .

3. The Contextual Gap

The third type of research gap is the contextual gap. Simply put, a contextual gap exists when there’s already a decent body of existing research on a particular topic, but an absence of research in specific contexts .

For example, there could be a lack of research on:

- A specific population – perhaps a certain age group, gender or ethnicity

- A geographic area – for example, a city, country or region

- A certain time period – perhaps the bulk of the studies took place many years or even decades ago and the landscape has changed.

The contextual gap is a popular option for dissertations and theses, especially for first-time researchers, as it allows you to develop your research on a solid foundation of existing literature and potentially even use existing survey measures.

Importantly, if you’re gonna go this route, you need to ensure that there’s a plausible reason why you’d expect potential differences in the specific context you choose. If there’s no reason to expect different results between existing and new contexts, the research gap wouldn’t be well justified. So, make sure that you can clearly articulate why your chosen context is “different” from existing studies and why that might reasonably result in different findings.

4. The Methodological Gap

Last but not least, we have the methodological gap. As the name suggests, this type of research gap emerges as a result of the research methodology or design of existing studies. With this approach, you’d argue that the methodology of existing studies is lacking in some way , or that they’re missing a certain perspective.

For example, you might argue that the bulk of the existing research has taken a quantitative approach, and therefore there is a lack of rich insight and texture that a qualitative study could provide. Similarly, you might argue that existing studies have primarily taken a cross-sectional approach , and as a result, have only provided a snapshot view of the situation – whereas a longitudinal approach could help uncover how constructs or variables have evolved over time.

Practical Examples

Let’s take a look at some practical examples so that you can see how research gaps are typically expressed in written form. Keep in mind that these are just examples – not actual current gaps (we’ll show you how to find these a little later!).

Context: Healthcare

Despite extensive research on diabetes management, there’s a research gap in terms of understanding the effectiveness of digital health interventions in rural populations (compared to urban ones) within Eastern Europe.

Context: Environmental Science

While a wealth of research exists regarding plastic pollution in oceans, there is significantly less understanding of microplastic accumulation in freshwater ecosystems like rivers and lakes, particularly within Southern Africa.

Context: Education

While empirical research surrounding online learning has grown over the past five years, there remains a lack of comprehensive studies regarding the effectiveness of online learning for students with special educational needs.

As you can see in each of these examples, the author begins by clearly acknowledging the existing research and then proceeds to explain where the current area of lack (i.e., the research gap) exists.

How To Find A Research Gap

Now that you’ve got a clearer picture of the different types of research gaps, the next question is of course, “how do you find these research gaps?” .

Well, we cover the process of how to find original, high-value research gaps in a separate post . But, for now, I’ll share a basic two-step strategy here to help you find potential research gaps.

As a starting point, you should find as many literature reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses as you can, covering your area of interest. Additionally, you should dig into the most recent journal articles to wrap your head around the current state of knowledge. It’s also a good idea to look at recent dissertations and theses (especially doctoral-level ones). Dissertation databases such as ProQuest, EBSCO and Open Access are a goldmine for this sort of thing. Importantly, make sure that you’re looking at recent resources (ideally those published in the last year or two), or the gaps you find might have already been plugged by other researchers.

Once you’ve gathered a meaty collection of resources, the section that you really want to focus on is the one titled “ further research opportunities ” or “further research is needed”. In this section, the researchers will explicitly state where more studies are required – in other words, where potential research gaps may exist. You can also look at the “ limitations ” section of the studies, as this will often spur ideas for methodology-based research gaps.

By following this process, you’ll orient yourself with the current state of research , which will lay the foundation for you to identify potential research gaps. You can then start drawing up a shortlist of ideas and evaluating them as candidate topics . But remember, make sure you’re looking at recent articles – there’s no use going down a rabbit hole only to find that someone’s already filled the gap 🙂

Let’s Recap

We’ve covered a lot of ground in this post. Here are the key takeaways:

- A research gap is an unanswered question or unresolved problem in a field, which reflects a lack of existing research in that space.

- The four most common types of research gaps are the classic literature gap, the disagreement gap, the contextual gap and the methodological gap.

- To find potential research gaps, start by reviewing recent journal articles in your area of interest, paying particular attention to the FRIN section .

If you’re keen to learn more about research gaps and research topic ideation in general, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach Blog . Alternatively, if you’re looking for 1-on-1 support with your dissertation, thesis or research project, be sure to check out our private coaching service .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

32 Comments

This post is REALLY more than useful, Thank you very very much

Very helpful specialy, for those who are new for writing a research! So thank you very much!!

I found it very helpful article. Thank you.

Just at the time when I needed it, really helpful.

Very helpful and well-explained. Thank you

VERY HELPFUL

We’re very grateful for your guidance, indeed we have been learning a lot from you , so thank you abundantly once again.

hello brother could you explain to me this question explain the gaps that researchers are coming up with ?

Am just starting to write my research paper. your publication is very helpful. Thanks so much

How to cite the author of this?

your explanation very help me for research paper. thank you

Very important presentation. Thanks.

Best Ideas. Thank you.

I found it’s an excellent blog to get more insights about the Research Gap. I appreciate it!

Kindly explain to me how to generate good research objectives.

This is very helpful, thank you

How to tabulate research gap

Very helpful, thank you.

Thanks a lot for this great insight!

This is really helpful indeed!

This article is really helpfull in discussing how will we be able to define better a research problem of our interest. Thanks so much.

Reading this just in good time as i prepare the proposal for my PhD topic defense.

Very helpful Thanks a lot.

Thank you very much

This was very timely. Kudos

Great one! Thank you all.

Thank you very much.

This is so enlightening. Disagreement gap. Thanks for the insight.

How do I Cite this document please?

Research gap about career choice given me Example bro?

I found this information so relevant as I am embarking on a Masters Degree. Thank you for this eye opener. It make me feel I can work diligently and smart on my research proposal.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 23, Issue Suppl 1

- 34 Methods for identifying and displaying research gaps

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Linda Nyanchoka 1 ,

- Catrin Tudur-Smith 2 ,

- Van Thu Nguyen 1 ,

- Raphaël Porcher Porcher 1

- 1 Centre de Recherche Épidémiologie et Statistique Sorbonne Paris Cité (CRESS-UMR1153) Inserm/Université Paris Descartes, Paris, France

- 2 University of Liverpool, Institute of Translational Medicine, Liverpool, UK

Objectives The current body of research is growing, with over 1 million clinical research papers published from clinical trials alone. This volume of health research demonstrates the importance of conducting knowledge syntheses in providing the evidence base and identifying gaps, which can inform further research, policy-making, and practice. This study aims to describe methods for identifying and displaying research gaps.

Method A scoping review using the Arksey and O’Malley methodological framework was conducted. We searched Medline, Pub Med, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Scopus, Web of Science, PROSPERO register, TRIP, Google Scholar and Google. The following combination of terms were used: ‘identifying gaps in research’, ‘research gaps’,’evidence gaps’, ‘research uncertainties’, ‘research gaps identification’,’research gaps prioritisation’ and ‘methods’. The searches were limited to English, conducted in humans and published in the last 10 years for databases searches and unrestricted for hand and expert suggestion articles.

Results The literature search retrieved 1938 references, of which 139 were included for data synthesis. Of the 139 studies, 91 (65%) aimed to identify gaps, 22 (16%) determine research priorities and 26 (19%) on both identifying gaps and determining research priorities. A total of 13 different definitions of research gaps were identified. The methods for identifying gaps included different study designs, examples included primary research methods (quantitative surveys, interview, and focus groups), secondary research methods (systematic reviews, overview of reviews, scoping reviews, evidence mapping and bibliometric analysis), primary and secondary research methods (James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnerships (JLA PSP) and Global Evidence Mapping (GEM). Some of the examples of methods to determine research priorities included delphi survey, needs assessment, consensus meeting and Interviews.The methods for displaying gaps and determine research priorities mainly varied according to the number of variables being presented.

Conclusions This study provides an overview of different methods used to and/or reported on identifying gaps, determining research priorities and displaying both gaps and research priorities. These study findings can be adapted to inform the development of methodological guidance on ways to advance methods to identify, prioritise and display gaps to inform research and evidence-based decision-making.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2018-111024.34

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Gap – Types, Examples and How to Identify

Research Gap – Types, Examples and How to Identify

Table of Contents

Research Gap

Definition:

Research gap refers to an area or topic within a field of study that has not yet been extensively researched or is yet to be explored. It is a question, problem or issue that has not been addressed or resolved by previous research.

How to Identify Research Gap

Identifying a research gap is an essential step in conducting research that adds value and contributes to the existing body of knowledge. Research gap requires critical thinking, creativity, and a thorough understanding of the existing literature . It is an iterative process that may require revisiting and refining your research questions and ideas multiple times.

Here are some steps that can help you identify a research gap:

- Review existing literature: Conduct a thorough review of the existing literature in your research area. This will help you identify what has already been studied and what gaps still exist.

- Identify a research problem: Identify a specific research problem or question that you want to address.

- Analyze existing research: Analyze the existing research related to your research problem. This will help you identify areas that have not been studied, inconsistencies in the findings, or limitations of the previous research.

- Brainstorm potential research ideas : Based on your analysis, brainstorm potential research ideas that address the identified gaps.

- Consult with experts: Consult with experts in your research area to get their opinions on potential research ideas and to identify any additional gaps that you may have missed.

- Refine research questions: Refine your research questions and hypotheses based on the identified gaps and potential research ideas.

- Develop a research proposal: Develop a research proposal that outlines your research questions, objectives, and methods to address the identified research gap.

Types of Research Gap

There are different types of research gaps that can be identified, and each type is associated with a specific situation or problem. Here are the main types of research gaps and their explanations:

Theoretical Gap

This type of research gap refers to a lack of theoretical understanding or knowledge in a particular area. It can occur when there is a discrepancy between existing theories and empirical evidence or when there is no theory that can explain a particular phenomenon. Identifying theoretical gaps can lead to the development of new theories or the refinement of existing ones.

Empirical Gap

An empirical gap occurs when there is a lack of empirical evidence or data in a particular area. It can happen when there is a lack of research on a specific topic or when existing research is inadequate or inconclusive. Identifying empirical gaps can lead to the development of new research studies to collect data or the refinement of existing research methods to improve the quality of data collected.

Methodological Gap

This type of research gap refers to a lack of appropriate research methods or techniques to answer a research question. It can occur when existing methods are inadequate, outdated, or inappropriate for the research question. Identifying methodological gaps can lead to the development of new research methods or the modification of existing ones to better address the research question.

Practical Gap

A practical gap occurs when there is a lack of practical applications or implementation of research findings. It can occur when research findings are not implemented due to financial, political, or social constraints. Identifying practical gaps can lead to the development of strategies for the effective implementation of research findings in practice.

Knowledge Gap

This type of research gap occurs when there is a lack of knowledge or information on a particular topic. It can happen when a new area of research is emerging, or when research is conducted in a different context or population. Identifying knowledge gaps can lead to the development of new research studies or the extension of existing research to fill the gap.

Examples of Research Gap

Here are some examples of research gaps that researchers might identify:

- Theoretical Gap Example : In the field of psychology, there might be a theoretical gap related to the lack of understanding of the relationship between social media use and mental health. Although there is existing research on the topic, there might be a lack of consensus on the mechanisms that link social media use to mental health outcomes.

- Empirical Gap Example : In the field of environmental science, there might be an empirical gap related to the lack of data on the long-term effects of climate change on biodiversity in specific regions. Although there might be some studies on the topic, there might be a lack of data on the long-term effects of climate change on specific species or ecosystems.

- Methodological Gap Example : In the field of education, there might be a methodological gap related to the lack of appropriate research methods to assess the impact of online learning on student outcomes. Although there might be some studies on the topic, existing research methods might not be appropriate to assess the complex relationships between online learning and student outcomes.

- Practical Gap Example: In the field of healthcare, there might be a practical gap related to the lack of effective strategies to implement evidence-based practices in clinical settings. Although there might be existing research on the effectiveness of certain practices, they might not be implemented in practice due to various barriers, such as financial constraints or lack of resources.

- Knowledge Gap Example: In the field of anthropology, there might be a knowledge gap related to the lack of understanding of the cultural practices of indigenous communities in certain regions. Although there might be some research on the topic, there might be a lack of knowledge about specific cultural practices or beliefs that are unique to those communities.

Examples of Research Gap In Literature Review, Thesis, and Research Paper might be:

- Literature review : A literature review on the topic of machine learning and healthcare might identify a research gap in the lack of studies that investigate the use of machine learning for early detection of rare diseases.

- Thesis : A thesis on the topic of cybersecurity might identify a research gap in the lack of studies that investigate the effectiveness of artificial intelligence in detecting and preventing cyber attacks.

- Research paper : A research paper on the topic of natural language processing might identify a research gap in the lack of studies that investigate the use of natural language processing techniques for sentiment analysis in non-English languages.

How to Write Research Gap

By following these steps, you can effectively write about research gaps in your paper and clearly articulate the contribution that your study will make to the existing body of knowledge.

Here are some steps to follow when writing about research gaps in your paper:

- Identify the research question : Before writing about research gaps, you need to identify your research question or problem. This will help you to understand the scope of your research and identify areas where additional research is needed.

- Review the literature: Conduct a thorough review of the literature related to your research question. This will help you to identify the current state of knowledge in the field and the gaps that exist.

- Identify the research gap: Based on your review of the literature, identify the specific research gap that your study will address. This could be a theoretical, empirical, methodological, practical, or knowledge gap.

- Provide evidence: Provide evidence to support your claim that the research gap exists. This could include a summary of the existing literature, a discussion of the limitations of previous studies, or an analysis of the current state of knowledge in the field.

- Explain the importance: Explain why it is important to fill the research gap. This could include a discussion of the potential implications of filling the gap, the significance of the research for the field, or the potential benefits to society.

- State your research objectives: State your research objectives, which should be aligned with the research gap you have identified. This will help you to clearly articulate the purpose of your study and how it will address the research gap.

Importance of Research Gap

The importance of research gaps can be summarized as follows:

- Advancing knowledge: Identifying research gaps is crucial for advancing knowledge in a particular field. By identifying areas where additional research is needed, researchers can fill gaps in the existing body of knowledge and contribute to the development of new theories and practices.

- Guiding research: Research gaps can guide researchers in designing studies that fill those gaps. By identifying research gaps, researchers can develop research questions and objectives that are aligned with the needs of the field and contribute to the development of new knowledge.

- Enhancing research quality: By identifying research gaps, researchers can avoid duplicating previous research and instead focus on developing innovative research that fills gaps in the existing body of knowledge. This can lead to more impactful research and higher-quality research outputs.

- Informing policy and practice: Research gaps can inform policy and practice by highlighting areas where additional research is needed to inform decision-making. By filling research gaps, researchers can provide evidence-based recommendations that have the potential to improve policy and practice in a particular field.

Applications of Research Gap

Here are some potential applications of research gap:

- Informing research priorities: Research gaps can help guide research funding agencies and researchers to prioritize research areas that require more attention and resources.

- Identifying practical implications: Identifying gaps in knowledge can help identify practical applications of research that are still unexplored or underdeveloped.

- Stimulating innovation: Research gaps can encourage innovation and the development of new approaches or methodologies to address unexplored areas.

- Improving policy-making: Research gaps can inform policy-making decisions by highlighting areas where more research is needed to make informed policy decisions.

- Enhancing academic discourse: Research gaps can lead to new and constructive debates and discussions within academic communities, leading to more robust and comprehensive research.

Advantages of Research Gap

Here are some of the advantages of research gap:

- Identifies new research opportunities: Identifying research gaps can help researchers identify areas that require further exploration, which can lead to new research opportunities.

- Improves the quality of research: By identifying gaps in current research, researchers can focus their efforts on addressing unanswered questions, which can improve the overall quality of research.

- Enhances the relevance of research: Research that addresses existing gaps can have significant implications for the development of theories, policies, and practices, and can therefore increase the relevance and impact of research.

- Helps avoid duplication of effort: Identifying existing research can help researchers avoid duplicating efforts, saving time and resources.

- Helps to refine research questions: Research gaps can help researchers refine their research questions, making them more focused and relevant to the needs of the field.

- Promotes collaboration: By identifying areas of research that require further investigation, researchers can collaborate with others to conduct research that addresses these gaps, which can lead to more comprehensive and impactful research outcomes.

Disadvantages of Research Gap

While research gaps can be advantageous, there are also some potential disadvantages that should be considered:

- Difficulty in identifying gaps: Identifying gaps in existing research can be challenging, particularly in fields where there is a large volume of research or where research findings are scattered across different disciplines.

- Lack of funding: Addressing research gaps may require significant resources, and researchers may struggle to secure funding for their work if it is perceived as too risky or uncertain.

- Time-consuming: Conducting research to address gaps can be time-consuming, particularly if the research involves collecting new data or developing new methods.

- Risk of oversimplification: Addressing research gaps may require researchers to simplify complex problems, which can lead to oversimplification and a failure to capture the complexity of the issues.

- Bias : Identifying research gaps can be influenced by researchers’ personal biases or perspectives, which can lead to a skewed understanding of the field.

- Potential for disagreement: Identifying research gaps can be subjective, and different researchers may have different views on what constitutes a gap in the field, leading to disagreements and debate.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

ARTICLE/RESEARCH: A Taxonomy of Research Gaps: Identifying and Defining the Seven Research Gaps

2017, Journal of Research Methods and Strategies

One of the most prevailing issues in the craft of research is to develop a research agenda and build the research on the development of the research gap. Most research of any endeavor is attributed to the development of the research gap, which is a primary basis in the investigation of any problem, phenomenon or scientific question. Given this accepted tenet of engagement in research, surprising in the research fraternity, we do not train researchers on how to systematically identify research gaps as basis for the investigation. This is has continued to be a common problem with novice researchers. Unfailingly, very little theory and research has been developed on identifying research gaps as a basis for a line in inquiry. The purpose of this research is threefold. First, the proposed theoretical framework builds on the five-point theoretical model of Robinson, Saldanhea, and McKoy (2011) on research gaps. Second, this study builds on the six-point theoretical model of Müller-Bloch and Franz (2014) on research gaps. Lastly, the purpose of this research is to develop and propose a theoretical model that is an amalgamation of the two preceding models and re-conceptualizes the research gap concepts and their characteristics. Thus, this researcher proposes a seven-point theoretical model. This article discusses the characteristics of each research and the situation in which its application is warranted in the literature review The significance of this article is twofold. First, this research provides theoretical significance by developing a theoretical model on research gaps. Second, this research attempts to build a solid taxonomy on the different characteristics of research gaps and establish a foundation. The implication for researchers is that research gaps should be structured and characterized based on their functionality. Thus, this provides researchers with a basic framework for identifying them in the literature investigation.

Related Papers

ISSAH BAAKO

Various researchers have established the need for researchers to position their research problem in the research gap of the study area. This does not only indicate the relevance of the study but it demonstrates the significant contribution it would make in the field of study. The purpose of this paper is to conduct a systematic literature review on the concept of research gaps and provoke a discussion on the contemporary literature on types of research gaps. The paper discusses the various approaches for researchers to identify, align and position research problems, research design, and methodology in the research gaps to achieve relevance in their findings and study. A systematic review of the current literature on research gaps might assist beginning researchers in the justification of research problems. Given the acceptable tenet of developing a research agenda, design, and development on a research gap, many early career researchers especially (post)graduate students have difficulties in systematically identifying research gaps as a basis for conducting research work. The significance of this paper is twofold. First, it provides a systematic review of literature on the identification of research gaps to undertake research that would challenge assumptions and underlying existing theories in a significant way. Second, it provides a theoretical discussion on the importance of developing research problems on research gaps to structure their study.

Kayode Oyediran

Problem in a research as well as human body calls for perfect diagnosis of illness. This is important to avoid treating the symptoms instead of the actual disease. A research problem could be identified through professional or/and academic efforts. This poses a lot of problems to students, both at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels, as this determines the title of their articles or research works. Many of them have to submit many topics to their supervisors before one could be reframed and approved. At times, students appealed to their supervisors to provide them with researchable topics. This to the supervisor(s) almost writing the dissertations/theses for them. The argument of this paper is to let students understand "problem identification" using an analogy from the Holy Bible. The study employed a conversation analysis methodology, which is empirically grounded, exploratory in process and inferential. This involves using every conversation between two or more parties to explore facts/lesson. It was recommended that seasoned lecturers should explain to students how to identify research problems using what are familiar to them to make them understand this important aspect of research.

Sid Ahmed KHETTAB

A research gap is generally any problem a scientific article, an academic book or a thesis may contain. In the previous article [https://discourse.clevious.com/2019/12/how-to-come-up-with-research-idea.html], based on Dr. Anthony Miles' article on research gaps, I summarized the 7 research gaps into three main categories: theoretical problems, reasoning problems, and empirical problems.

Research to Action: The Global Guide to Research Impact

Steven E Wallis, PhD

The basics of research are seemingly clear. Read a lot of articles, see what’s missing, and conduct research to fill the gap in the literature. Wait a minute. What is that? “See what’s missing?” How can we see something that is not there? In this post, we will show you how to “see the invisible;” How to identify the missing pieces in any study, literature review, or program analysis. With these straight-forward techniques, you will be able to better target your research in a more cost-effective way to fill those knowledge gaps to develop more effective theories, plans, and evaluations.

UNICAF University - Zambia

Ivan Steenkamp

Azeez T Fatimo

Researchers and academia often have difficulties identifying the research gap in literature in various fields of study. Hence, exploring research gap is one of the most arduous tasks for researchers especially those at the preliminary stage. The explicit identification of research gap is an inevitable step in developing a research agenda including decision about funding and the design of informative studies. Thus, to identify the research gap, the researcher needs to prune down his area of interest as identifying research gaps requires a lot of reading and analyzing of materials from various literatures. Hence, this study explores literatures regarding the method of identifying research gaps in management sciences. This was done by extensively examining various literatures on the method of identifying research gaps from previous researchers. However, the study made use of content analysis to identify research gaps in some articles. This study revealed that researchers are focused on a single type of research gap, leaving other research gaps unexplored. Also, there are some methods of research identification that has remained understandable by researchers as there are little or no knowledge about them. Hence, the study recommended among others that the various research identification methods be explored by researchers who intend to engage in studies in this field of management sciences.

Omini Akpang

This section contains the four Thematic Gap Analyses and the Cross-Cutting Gap Analysis. Each of the chapters has a lead author (s) as noted on the front page of the chapter. This follows the way that the team has divided-up the responsibilities for each Thematic Area, with a disciplinary specialist (s) taking the lead on each area. The chapters have, however, been reviewed and commented by others in the project team so the analysis and suggested actions and conclusions have the general support of the full project team.

In this second part of The Reason to Replicate Research, I develop with more details and explanations the Reasoning Gaps idea I briefly discussed in the article “How to Come Up with Research Question Easily Like a Pro”. (https://discourse.clevious.com/2019/12/how-to-come-up-with-research-idea.html) And just like in Part I (https://discourse.clevious.com/2020/01/the-empirical-gap-to-replicate-research.html), I will try to pivot the explanation around an example and show why they are important to fill.

David Nicholas

RELATED PAPERS

Psychologie a její kontexty

Andrea Beláňová

New Cellular and Molecular Biotechnology Journal

Clinical and Research Journal in Internal Medicine

Mirza Zaka Pratama

Cláudio Parisi

Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics

Jérôme Blanc

masitoh siregar

priyanka kalita

Journal of Adolescence

Jessica Toste

Vestnik Tomskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Filologiya

Valery Solovyev

Tetsuya Sado

Andrea D' Agostino

Foraging assemblages : papers presented at the ninth International Conference on the Mesolithic in Europe, Belgrade 2015, volume 2

Koen Deforce

Encounters at borders and across borders. Hymnos 2024: The yearbook of the Finnish Society for Hymnology and Liturgy

Per Kristian Aschim

Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology

simon peraza

Gaceta de M�xico

Eduardo Ruiz

Bart Cambre

Cirugía Española

José Luis Aguayo-Albasini

Cerdas Sifa Pendidikan

ely yuliawan

Revista da Faculdade de Educação

JOSIANE MAGALHAES

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Open access

- Published: 21 May 2024

Injuries and /or trauma due to sexual gender-based violence among survivors in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic scoping review of research evidence

- Desmond Kuupiel 1 , 2 ,

- Monsurat A. Lateef 1 ,

- Patience Adzordor 3 , 4 ,

- Gugu G. Mchunu 1 &

- Julian D. Pillay 1

Archives of Public Health volume 82 , Article number: 78 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

152 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) is a prevalent issue in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), causing injuries and trauma with severe consequences for survivors. This scoping review aimed to explore the range of research evidence on injuries and trauma resulting from SGBV among survivors in SSA and identify research gaps.

The review employed the Arksey and O’Malley methodological framework, conducting extensive literature searches across multiple electronic databases using keywords, Boolean operators, medical subject heading terms and manual searches of reference lists. It included studies focusing on injuries and trauma from SGBV, regardless of gender or age, published between 2012 and 2023, and involved an SSA countries. Two authors independently screened articles, performed data extraction and quality appraisal, with discrepancies resolved through discussions or a third author. Descriptive analysis and narrative synthesis were used to report the findings.

After screening 569 potentially eligible articles, 20 studies were included for data extraction and analysis. Of the 20 included studies, most were cross-sectional studies ( n = 15; 75%) from South Africa ( n = 11; 55%), and involved women ( n = 15; 75%). The included studies reported significant burden of injuries and trauma resulting from SGBV, affecting various populations, including sexually abused children, married women, visually impaired women, refugees, and female students. Factors associated with injuries and trauma included the duration of abuse, severity of injuries sustained, marital status, family dynamics, and timing of incidents. SGBV had a significant impact on mental health, leading to post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, suicidal ideations, and psychological trauma. Survivors faced challenges in accessing healthcare and support services, particularly in rural areas, with traditional healers sometimes providing the only mental health care available. Disparities were observed between urban and rural areas in the prevalence and patterns of SGBV, with rural women experiencing more repeated sexual assaults and non-genital injuries.

This scoping review highlights the need for targeted interventions to address SGBV and its consequences, improve access to healthcare and support services, and enhance mental health support for survivors. Further research is required to fill existing gaps and develop evidence-based strategies to mitigate the impact of SGBV on survivors in SSA.

Peer Review reports

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that injuries are a growing global public health problem [ 1 ]. In 2021, unintentional and violence-related injuries were estimated to cause over 4 million deaths worldwide, accounting for nearly 8% of all deaths [ 1 ]. Additionally, injuries are responsible for approximately 10% of all years lived with disability each year [ 1 ]. While injuries can result from various causes such as road traffic accidents, falls, drowning, burns, poisoning, and acts of violence, including sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) [ 1 , 2 ], SGBV remains a neglected cause of injuries that silently affects the lives of many, especially women [ 3 , 4 ]. Injuries due to SGBV refer to physical harm or trauma resulting from acts of violence perpetrated based on an individual’s sex or gender. These injuries can encompass a range of physical harm, including but not limited to bruises, cuts, fractures, internal injuries, and sexual trauma (psychological or emotional) [ 5 ].

Sexual and gender-based violence is a pervasive issue [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ] with alarming rates globally, particularly in the WHO Africa and South-East Asia regions with 33% each compared to 20% in the Western Pacific, 22% in high-income countries and Europe, and 31% in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean region [ 8 ]. However, this statistic includes only physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner alone and does not include other forms of violence [ 8 ]. Sexual and gender-based violence encompasses various acts such as sexual assault, rape, intimate partner violence, and harmful traditional practices, all of which have severe physical and psychological consequences for women [ 9 , 11 , 12 ]. The sub-Saharan Africa region has witnessed numerous cases of SGBV perpetrated against vulnerable populations, such as women, children, refugees, and individuals with disabilities, with devastating impacts on their well-being and overall quality of life [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ].

Understanding the extent and nature of injuries and trauma resulting from SGBV among survivors is crucial in formulating effective interventions, policies, and support systems. Research evidence plays a fundamental role in shaping responses to this pressing public health concern, guiding the development of targeted interventions and preventive measures. However, the available research on injuries and trauma related to SGBV in sub-Saharan Africa remains scattered and diverse, necessitating a comprehensive and systematic review to consolidate and analyse existing knowledge.

A scoping review study would support a valuable research approach to systematically map and describe the existing evidence on injuries and trauma related to SGBV against women in sub-Saharan Africa. In so doing, the scoping review would provide a broader overview of the literature to identify knowledge gaps, key concepts, and various study designs employed in the field, and inform more specific research questions that can be unpacked by way of a systematic review and /or meta-analysis quantitative studies or meta-synthesis of qualitative studies [ 33 , 34 ]. To our knowledge, current literature shows no evidence of any previous scoping review that has focused on injuries and trauma due SGBV. This study, therefore, conducted a systematic scoping review to explore the scope of research evidence regarding injuries and trauma stemming from SGBV among survivors in sub-Saharan Africa. This research sheds light on the prevalence, patterns, and factors associated with injuries and trauma resulting from SGBV in the region and their impact on survivors.

To achieve the objective of this scoping review, we utilised the Arksey and O’Malley methodological framework [ 35 ] as a guiding framework for mapping and examining the literature on injuries and trauma associated with SGBV in the context of sub-Saharan Africa. This framework comprises several key steps, including identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, study selection, data charting and collation, and summarizing and reporting the results [ 33 , 34 ].

Identifying the research question

The primary research question guiding this scoping review is as follows: What is the scope of research evidence regarding injuries and trauma resulting from sexual and gender-based violence among survivors in sub-Saharan Africa in the last decade? To ensure the appropriateness and relevance of this question, we employed the Population, Concept, and Context (PCC) framework [ 36 ] as part of the study eligibility criteria, which is detailed in Table 1 . To comprehensively address the research objective, the scoping review explored the following sub-questions:

Literature searches

The purpose of our search was to identify relevant peer-reviewed papers that address the review questions. To accomplish this, a comprehensive search was conducted across several electronic databases, including PubMed, EBSCOhost (CINAHL, PsycInfo, and Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition), SCOPUS, and Web of Science for original articles published within between 2012 and 2023. Additionally, a search using the Google Scholar search engine was performed to identify additional literature of relevance. For the database searches, we developed a search strategy in collaboration with an information scientist, ensuring the inclusion of relevant keywords such as “survivor,” “gender-based violence,” “sexual violence,” “injuries,” and “trauma.” We employed Boolean operators (AND/OR) and Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms to refine the search string (Please refer to Supplementary File 1 for the detailed search strategy). Adjustments were made to the syntax based on the specific requirements of each database. The information scientist also played a role in conducting website searches. In addition to electronic searches, we manually explored the reference lists of included sources to identify any additional relevant literature. At this stage, no search filters based on language or publication type were applied, however, the search results will be limited to publications from 2012 to 2023. This date limitation was to enable as captured recent and relevant studies to understand the current trend. All search results were imported into an EndNote Library X20 for efficient citation management.

Articles selection process