Time Use in Economics

Economics is about scarcity – how to allocate resources in the presence of limits. Time is the scarcest factor at a human’s disposal. However, while economic research has concentrated on our spending on goods and services – or more recently on happiness and individual well-being – it has paid relatively much less attention to how we spend our time. The 51st RLE volume on “Time Use in Economics” illustrates the importance of intensifying this research. Its ten articles shed new light on issues such as the impact of job loss on parental time investment, work hours and childcare decisions, time use and intrahousehold inequality, and most recent changes in work day characteristics.

Research in Labor Economics is a biannual series that publishes new peer-reviewed research on important and policy-relevant topics in labor economics.

Recent volumes:, 50th celebratory volume, workplace productivity and management practices, change at home, in the labor market, and on the job, health and labor markets, about the journal.

Research in Labor Economics is a biannual series which publishes new peer-reviewed research on important and policy-relevant topics in labor economics. The Series which is published by Emerald aims to apply economic theory and econometrics to analyze important policy related questions, often with an international focus.

Over the years RLE has continued to present important new research in labor economics particularly regarding worker well-being. It covers themes such as labor supply, work effort, schooling, on-the-job training, earnings distribution, discrimination, migration, and the effects of government policies.

The articles are of three genres: (1) results from ongoing or completed important research endeavors, (2) critical survey articles, (3) and symposia on policy related topics.

Research in Labor Economics (RLE) was founded in 1977 by Ronald Ehrenberg and JAI Press, and has been published by Elsevier from 1999-2007 and by Emerald since 2008. Solomon Polachek has been editor since 1995.

Beginning in 2007 RLE affiliated with the IZA – Institute of Labor Economics, an independent non-profit research institution running the world's largest network of Fellows and Affilates in the field. At that time publication extended to two volumes per year. Since 2008 Konstantinos Tatsiramos has been serving as the IZA Co-Editor of RLE (following Olivier Bargain who acted in this capacity 2007–2008). Benjamin Elsner will take over this role in 2023.

Since its inception RLE published over 350 articles encompassing a wide range of themes spanning an array of labor economics topics. Authors have ranged from young scholars with much potential to mature leaders in the field, including Nobel Prize and John Bates Clark award winners.

Solomon W. Polachek

Binghamton University

- Orley C. Ashenfelter Princeton University

- Francine D. Blau Cornell University

- Richard Blundell University College London

- Alison L. Booth Australian National University

- David Card University of California, Berkeley

- Ronald G. Ehrenberg Cornell University

- Richard B. Freeman Harvard University

- Reuben Gronau Bank of Israel

- Daniel S. Hamermesh Barnard College

- James J. Heckman University of Chicago

- Edward P. Lazear Stanford University

- Christopher A. Pissarides London School of Economics

- Yoram Weiss Tel Aviv University

- Klaus F. Zimmermann UNU-MERIT, Maastricht University

Benjamin Elsner

University College Dublin

Journal of Labor Research

- Offers a diverse range of topics on employment practices and policies.

- Focuses on new types of employment relationships, and emerging economic and institutional arrangements related to labor issues.

- Provides objective analyses of employee-related issues.

This is a transformative journal , you may have access to funding.

Latest issue

Volume 45, Issue 1

Latest articles

Childcare responsibilities and parental labor market outcomes during the covid-19 pandemic.

- Kairon Shayne D. Garcia

- Benjamin W. Cowan

The incidence and effects of decentralized wage bargaining in Finland

- Antti Kauhanen

- Terhi Maczulskij

- Krista Riukula

Mobile Politicians: Opportunistic Career Moves

- Duha T. Altindag

Exposure to Economic Distress during Pregnancy and Birth Outcomes

- Mevlude Akbulut-Yuksel

- Seyit Mümin Cilasun

- Belgi Turan

Estimating Long-Term Impacts of Wartime Schooling Disruptions on Private Returns to Schooling in Kuwait

- Mohamed Ihsan Ajwad

- Faleh AlRashidi

Journal updates

Call for editor-in-chief.

Springer Science + Business Media is seeking applications and nominations for the position of Editor-in-Chief for the Journal of Labor Research. Click here for more information.

Call for Papers: Multi-Journal Collection on SDG 8

Recent Top Cited Papers

Read the most cited articles recently published in the Journal of Labor Research.

Journal information

- ABS Academic Journal Quality Guide

- Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC) Journal Quality List

- Current Contents/Social & Behavioral Sciences

- Google Scholar

- OCLC WorldCat Discovery Service

- Research Papers in Economics (RePEc)

- Social Science Citation Index

- TD Net Discovery Service

- UGC-CARE List (India)

Rights and permissions

Editorial policies

© Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

- Publications

Research in Labor Economics

Research in Labor Economics (RLE) is a biannual series that publishes new peer-reviewed research applying economic theory and econometrics to policy related topics pertinent to worker well-being, often with an international focus. Typical themes of each volume include labor supply, work effort, schooling, on-the-job training, earnings distribution, discrimination, migration, health, and the effects of government policies.

RLE invites all academics and researchers in the field of labor economics to submit manuscripts that meet its stringent standards for consideration in the series. Manuscripts can be submitted via the IZA website using the Quick Access and following the link "For Authors". Proposals for special issues and symposia are also considered.

Published articles in RLE are indexed in EconLit, Google Scholar, RePEc, and SCOPUS.

Research in Labor Economics is published by Emerald in conjunction with IZA.

Editor: Solomon Polachek , IZA Co-Editor: Benjamin Elsner

Contact: [email protected]

Quick Access

Cookie settings

These necessary cookies are required to activate the core functionality of the website. An opt-out from these technologies is not available.

In order to further improve our offer and our website, we collect anonymous data for statistics and analyses. With the help of these cookies we can, for example, determine the number of visitors and the effect of certain pages on our website and optimize our content.

Research in Labor Economics

- Recent Chapters

All books in this series (34 titles)

Recent chapters in this series (18 titles)

- Blurred Boundaries: A Day in the Life of a Teacher

- Change and Continuity in Americans' Work Day Characteristics, 2019 to 2021

- Changes in Children’s Time Use, India 1998–2019

- Effort at Work and Worker Well-Being

- Marriage Versus Cohabitation: How Specialization and Time Use Differ by Relationship Type

- Parents' Work Hours and Childcare Decisions: Exploiting a Time Windfall

- The Impact of Job Loss on Parental Time Investment

- Time Use and the Geography of Economic Opportunity

- Time Use, Intrahousehold Inequality, and Individual Welfare: Revealed Preference Analysis

- Time-Use and Subjective Well-Being: Is Diversity Really the Spice of Life?

- Agency, Activism, and the Expansion of the Regulatory State *

- Compensating Differentials for Occupational Health and Safety Risks: Implications of Recent Evidence

- Gender Economics: Dead-Ends and New Opportunities

- Productivity and Wages: What Was the Productivity–Wage Link in the Digital Revolution of the Past, and What Might Occur in the AI Revolution of the Future?

- Right-to-Work Laws, Unionization, and Wage Setting

- The Career Evolution of the Sex Gap in Wages: Discrimination Versus Human Capital Investment

- The Effects of Advanced Degrees on the Wage Rates, Hours, Earnings, and Job Satisfaction of Women and Men *

- The Fall and Rise of Immigrant Employment During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Professor Solomon Polachek

- Dr Konstantinos Tatsiramos

We’re listening — tell us what you think

Something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

The Reporter

Program Report: Labor Studies, 2020

The Labor Studies Program is one of the largest and most active in the NBER. Its nearly 190 members produce more than 300 working papers in an average year. The breadth and depth of questions addressed by Labor Studies members is immense. Research touches on macroeconomic topics such as unemployment and productivity; institutional factors such as minimum wage regulations, labor unions, and globalization; and technological developments including robotics, artificial intelligence, and algorithmic decision-making. It also includes core human capital subjects such as educational investment, the demand and supply of skills, and wage determination; industrial organization topics such as imperfect competition, rent sharing, and firm-specific wage policies; and social insurance and welfare programs such as unemployment insurance, universal basic income, and in-kind benefit programs such as SNAP, Medicaid, and housing assistance. Program affiliates also study urgent social questions, including race and gender disparities in market opportunities, neighborhood quality, treatment by the criminal justice system, and many other subject domains.

Reflecting their intellectual diversity, two-thirds of Labor Studies Program members are affiliated with two or more NBER programs or major projects. Though the pandemic has curtailed some program activities, it has simultaneously opened new horizons. The online meeting environment has allowed many nonaffiliated scholars to participate in program meetings. Meanwhile, researchers who prefer to audit rather than participate in program sessions can watch meetings streamed live on NBER’s YouTube channel. In the post-pandemic world, the program will strive to keep these professional and intellectual doors open.

This brief report summarizes a small subset of topics where research by Labor Studies affiliates is burgeoning, including the role of firms in wage determination; the minimum wage; the consequences of advancing technologies for employment and productivity; race and ethnicity in the labor market; and the extent and consequences of racial and ethnic discrimination and segregation. This summary does not do justice to the vast body of recent scholarship by program affiliates, though our hope is that it reveals some important research undercurrents.

Automation, Employment, and Productivity

The role of automation in shaping labor demand, skill requirements, and wage levels has been of intense economic interest for centuries. Even so, this topic has gained further prominence as rapid advances in ubiquitous computing, artificial intelligence, and robotics have imbued machines with the ability to accomplish tasks that require learning, judgment, and dexterity. Labor Studies scholars have taken numerous angles of attack to assess what this has meant for labor markets and to forecast what may lie ahead.

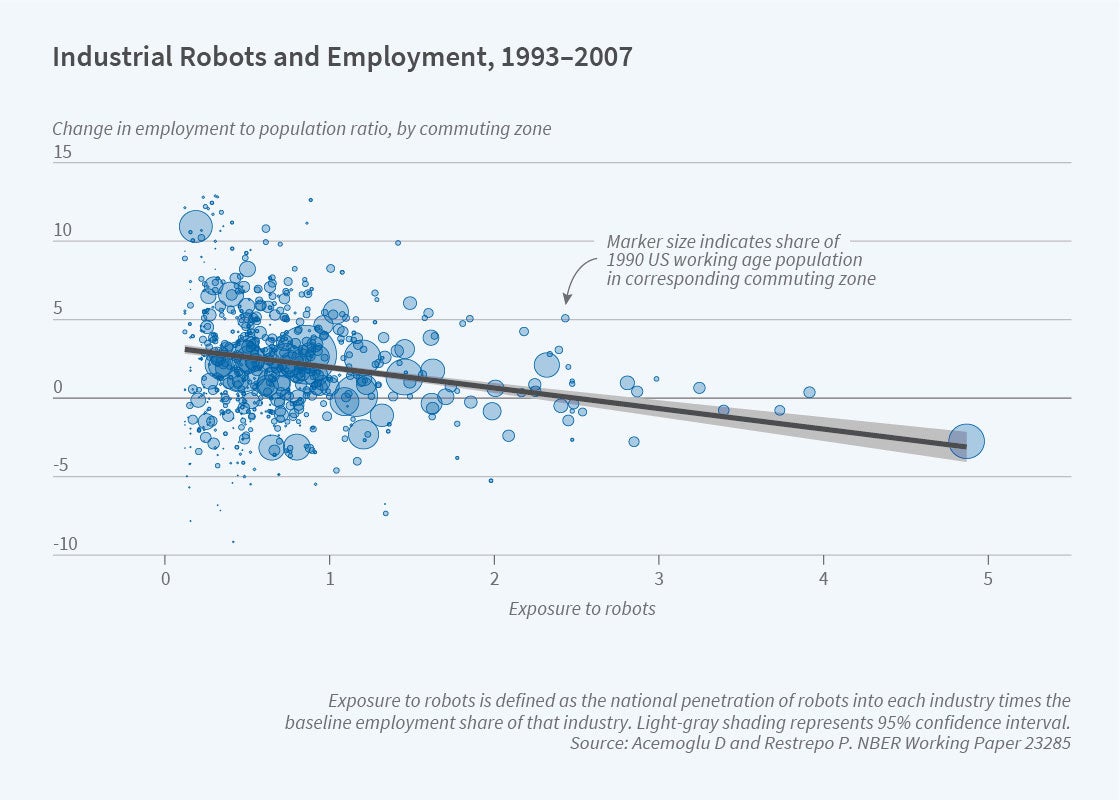

One influential paper in this domain by Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo explores how the expansion of industrial robotics has affected employment and wages in local labor markets — so-called commuting zones. 1 Harnessing data on industrial robot penetration in other industrialized countries to measure the technological frontier, the researchers calculate predicted robot adoption in the United States within local labor markets based on initial industry structures in those locations. A key finding is that local labor markets with greater exposure to robot adoption saw differential falls in employment-to-population rates (and wages, not pictured) in the 1990s and early 2000s. An independent empirical contribution by George Borjas and Richard Freeman reaches a similar conclusion. 2

Brad Hershbein and Lisa B. Kahn explore how recessions may accelerate the process of technological change by studying the evolution of skill requirements posted in job vacancies, using a vast database of vacancy postings scraped from the web by Burning Glass Technologies. 3 They show that skill requirements in job vacancy postings differentially increased in metropolitan statistical areas that were hit hardest by the Great Recession, and these increases persisted through at least the end of 2015, long after the recession was over. They interpret this evidence as consistent with adjustment cost models in which adverse shocks accelerate the process of adaptation to new business processes, in this case, so-called routine-task-replacing technologies and the more-skilled workers who complement them. Consonant with these findings, Alex W. Chernoff and Casey Warman argue that the current COVID-19 pandemic may speed the process of automation. They further present evidence that in a large set of countries, the occupations held disproportionately by women are at greater risk of displacement by automation, implying that the post-pandemic labor market may offer fewer of the positions frequently held by women. 4

Illuminating another facet of the interplay among technological change, demand shifts, and labor market adjustment, Elizabeth U. Cascio and Ayushi Narayan study the impact of the introduction of hydraulic fracturing (fracking) for oil extraction, a technology introduced during the 2000s, on educational investments. 5 Because fracking offers high-paying blue-collar jobs to workers without secondary credentials, it potentially raises the opportunity cost of schooling. As theory would predict — and as many parents would lament — high school dropout rates rose among male teenagers living near shale oil deposits.

What are the long-run implications of advancing automation for skill demands? A theoretical paper by Seth G. Benzell, Laurence J. Kotlikoff, Guillermo LaGarda, and Jeffrey D. Sachs considers how, in an overlapping generation setting, automation can ultimately lead to worker immiseration by reducing capital formation as long-lived, barely depreciating software capital effectively makes high-skill workers redundant. 6 In related work, Anton Korinek and Joseph E. Stiglitz consider the challenges that artificial intelligence may ultimately pose for income distribution and unemployment. 7 David E. Bloom, Mathew McKenna, and Klaus Prettner place this issue in global perspective by observing that the global labor market will need to absorb roughly three-quarters of a billion new workers between 2010 and 2030. 8 With 91 percent of that growth occurring in low- and lower-middle-income countries, they raise the concern that technological advances may create headwinds because the labor-intensive jobs currently prevalent in developing countries may be increasingly subject to automation.

While most of the papers above focus on the economic implications of machines substituting for labor, work by David Deming presents evidence that as automation proceeds, the demand for human capabilities is rising on another margin: social and managerial skills. 9 Deming argues that as information technology has replaced workers in routine codifiable tasks, it has magnified the value of social skills that allow workers to specialize and collaborate more efficiently. In a related vein, Gaetano Basso, Giovanni Peri, and Ahmed Rahman provide evidence that low-education US immigrants have helped blunt the impact of automation on native US workers. 10

In work that appears prescient in light of the current pandemic, Nicholas Bloom, James Liang, John Roberts, and Zhichun Jenny Ying examine another labor market manifestation of advancing information technology: remote work. 11 Partnering with a large Chinese travel agency, the researchers conduct a large field experiment in which travel agents were randomly offered the option to work from home. Among those offered the work-from-home option, both productivity and worker satisfaction rose. Ironically, promotion rates conditional on performance fell among those working from home, suggesting that not being in the office may also have hidden private costs.

This growing body of theory and evidence on labor market consequences of automation highlights an enduring macroeconomic puzzle raised by Robert Solow: “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” 12 Though Solow’s observation dates to 1987, the puzzle has only deepened since that time — particularly with the pronounced slowdown in measured productivity growth in industrialized countries that Chad Syverson documents took place after approximately 2004. 13 If machines are becoming so much cheaper and faster at accomplishing tasks once requiring expensive labor, why isn’t productivity rising more rapidly? Papers by Erik Brynjolfsson, Daniel Rock, and Syverson, 14 among others, confront this puzzle, arguing that these productivity gains are near at hand. Their work makes the case that the productivity benefits of new technologies are masked by substantial unmeasured complementary investments made by technology adopters, such as new business processes and business models, novel products, and new human capital. If this explanation is correct, productivity should surge when the unmeasured investment phase slows and these hidden investments begin yielding measurable returns. Alternatively, Acemoglu and Restrepo offer a more skeptical interpretation of the productivity paradox, arguing that many heavily hyped information technologies are barely cheaper or more productive than the labor-using tasks that they displace. 15 These “so-so” technologies, as these researchers label them, have the dual disadvantage of generating substantial worker displacement without yielding much of a productivity payoff. It is premature to know which view of our productivity predicament is correct.

Discrimination and Segregation in the Labor Market

A large body of recent scholarship by Labor Studies researchers brings new ambition, depth, and nuance to research on race and ethnicity in the labor market. Approximately 50 studies have focused specifically on race, discrimination, or segregation. In two studies, Marianne Bertrand and Esther Duflo 16 and David Neumark 17 review and synthesize the growing set of experimental analyses of discrimination.

A number of important articles have harnessed new data sources and state-of-the-art econometric methods to document new facts about racial and ethnic disparities in the labor market, and differences in economic mobility. A common thread in these studies is the degree of persistence in racial and ethnic gaps in economic and social outcomes. Economic gaps have remained immutable since the mid-20th century and have not been closed through individual or intergenerational economic mobility.

Patrick Bayer and Kerwin Kofi Charles decompose changes in the Black-White earnings gap between 1940 and 2010 into parts attributable to changes in the overall wage structure and to changes in the relative ranks of Blacks and Whites in the earnings distribution. 18 They show that while the median White-Black male earnings gap declined between 1940 and 1970, it has grown substantially in recent decades and was at 1950s levels by the Great Recession. This growth in the gap has been driven by declining labor force participation, and in particular mass incarceration. The position of median Black workers in the White distribution of earnings has hardly improved since 1940, while there have been positional gains for Black workers in the 90th percentile of the earnings distribution.

These conclusions are echoed in Randall Akee, Maggie Jones, and Sonya Porter’s work using US tax records to document persistent differences in income shares across the entire income distribution between White households and Black, Native American, and Hispanic households. 19 These differences are highly persistent. One of the breakthroughs in this paper is that by using the universe of tax returns, they can home in on small groups that previously could not be analyzed easily using survey data, notably Native Americans. Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Jones, and Porter build on this work by computing measures of intergenerational mobility by race and ethnic group. 20 They find that there has been very limited upward economic mobility of Black Americans and Native Americans, resulting in persistent gaps relative to White Americans over generations. On the other hand, Hispanic Americans have higher intergenerational mobility rates, leading to a convergence in the income gap between them and non-Hispanic Whites across generations.

One of the major themes in the studies on race and ethnicity is discrimination. Economics research has grappled with the topic of racial discrimination at least since Gary Becker’s seminal 1957 treatise on this topic. 21 Research in this area has evolved from viewing discrimination as a specific action or transaction (e.g., a biased hiring decision) to a process that affects skills investment, information acquisition and inference, and self-perception, and even directly influences the productivity of the targets of discrimination.

Economists have historically categorized discrimination into two buckets: taste-based discrimination based upon animus (per Becker) and statistical discrimination based upon rational (Bayesian) information forecasting in the face of uncertainty about productivity (per Kenneth Arrow and Edmund Phelps). Recent research underscores why these categories are incomplete and, in some cases, not entirely coherent. Studying the productivity of cashiers in a French grocery store chain, Dylan Glover, Amanda Pallais, and William Pariente show that non-White cashiers perform on average significantly better than do White workers. 22 Yet when assigned to managers who exhibit greater bias, the productivity of non-White workers — measured by absences and throughput — falls. This work calls into question the canonical assumption that discrimination represents unequal treatment for given expected levels of productivity by showing that prejudice can directly affect productivity.

An equally central assumption in the classic statistical discrimination literature is that employers hold rational expectations about worker capabilities, so that disparate treatment of minority and nonminority workers reflects unbiased but imprecise assessments of expected productivity. Challenging this view, J. Aislinn Bohren, Kareem Haggag, Alex Imas, and Devin G. Pope review evidence that statistical discrimination is often rooted in inaccurate information, such as bad statistics or stereotypes, which may of course emanate from prejudiced information sources. 23 This observation is potentially critical for interpreting and redressing discrimination in practice. An employer that makes otherwise statistically sound decisions based on biased information may generate outcomes that are indistinguishable from animus-based discrimination. Yet the appropriate remedy might be to provide accurate information rather than to redress or punish bias. Consistent with a potential role for misinformation, Amanda Y. Agan and Sonja B. Starr show that employers located in neighborhoods with fewer Black residents appear much likelier to stereotype Black applicants as potentially criminal when they lack criminal record information. 24

Many other studies provide fresh insights on discrimination. Experimental work by Joanna N. Lahey and Douglas R. Oxley shows how discrimination affects not only beliefs of potential employers but also the amount of attention that they devote to applicants from different race, gender, and age groups. 25 In a resume audit study, Patrick M. Kline and Christopher R. Walters develop new tools for detecting the presence of employer discrimination. 26

In an innovative experiment, Samantha Bielen, Wim Marneffe, and Naci H. Mocan experimentally manipulate the apparent race of defendants in recorded criminal trials using virtual reality tools. Law students, economics students, practicing lawyers, and judges who are randomly assigned to watch the trials are more likely to recommend conviction of defendants when they are portrayed in virtual reality as minorities. 27

Benjamin Feigenberg and Conrad Miller reanalyze the classic question of whether there is an equity/efficiency tradeoff in policing activity, specifically in the case of motor vehicle searches. 28 A tradeoff might arise if police are more effective in identifying offenders when permitted to use racial or ethnic profiling to select targets. The obvious cost of that approach is that members of disadvantaged groups — the vast majority of whom are not engaged in illicit conduct — would bear a disproportionate burden of police scrutiny. While models of statistical discrimination imply that this tradeoff exists in theory, Feigenberg and Miller find no such tradeoff in practice, at least in the case of vehicle searches conducted by Texas Highway Patrol troopers. The reason is that search rates by troopers are unrelated to the proportion of searches that detect illicit activity. By implication, the Texas Highway Patrol could equalize search rates across racial groups while increasing search yield without changing the total number of searches conducted.

Three papers look at historical episodes of discrimination in 20th century American history. Lisa D. Cook, Jones, David Rosé, and Trevon D. Logan document racial discrimination in public accommodations during the Jim Crow era. 29 They provide new facts on how the prevalence of nondiscriminatory establishments varied by region; how they were far more likely to be located in redlined neighborhoods within cities; and how their prevalence was positively correlated with measures of material well-being and overall economic activity. Andreas Ferrara and Price V. Fishback show that German immigrants residing in the United States during World War I faced significant anti-German sentiment, particularly in counties with high wartime casualty rates where local newspapers published more anti-German slurs. 30 German immigrants living in these counties were more likely to relocate; those who fled — and the counties that lost them — saw lower incomes for the next several decades.

Anna Aizer, Ryan Boone, Adriana Lleras-Muney, and Jonathan Vogel document beneficial effects of WWII defense production contracts in closing racial wage gaps. 31 In particular, when the federal government awarded wartime production contracts to private firms, Black men in the surrounding metropolitan area were able to move into higher-skilled occupations, generating sizable and enduring earnings benefits. A key figure from their paper is reproduced as Figure 2.

An increasingly prominent topic is whether the use of computerized algorithms for high-stakes decisions — such as which candidates receive interviews, which borrowers are granted loans, which defendants are released on bail — introduces the potential for algorithmic discrimination. Danielle Li, Lindsey R. Raymond, and Peter Bergman argue that machine learning algorithms that perform candidate selection for job interviews tend to reinforce past patterns of hiring by seeking candidates who are similar to those previously hired. 32 The researchers show the downside to this approach by building a resume screening algorithm that values exploration — that is, sampling from diverse pools — as well as past practice. Using personnel data from a large firm, they show that this approach improves the quality of candidates selected for an interview, as measured by eventual hiring rates, while also increasing demographic diversity relative to the firm’s existing practices. A number of other studies develop tools for detecting bias in algorithms 33 , 34 and consider how algorithms can be used more effectively. 35

Minimum Wage

One of the great debates in labor economics has been on the effects of minimum wages on workers and firms. Over the last 10 years, a series of studies by Labor Studies affiliates has advanced this literature considerably. These studies have used new sources of variation in minimum wages from state and local minimum wage laws, new data sources, and new econometric approaches. Studies don’t always reach the same conclusions, likely owing to the different settings, time periods, and methodologies being used. Below we summarize several studies that look at employment and hour margins and that draw disparate conclusions.

Jeffrey Clemens and Michael Wither examine the last increase (at the time of this writing) of the federal minimum wage, which took place over 2008–09. 36 The timing of this increase makes this an especially interesting case since it coincided with the Great Recession, when the labor market may have been more sensitive to wage increases, but it also presents challenges for estimation, as it requires the researchers to carefully control for the business cycle. Using several approaches, including differences in how binding the minimum wage was between states, they estimate that employment fell by 8 percent among workers whose wages before the minimum wage increase were below the new minimum.

Ekaterina Jardim, Mark C. Long, Robert Plotnick, Emma van Inwegen, Jacob Vigdor, and Hilary Wething evaluate a minimum-wage ordinance that raised the minimum wage from $9.47 to $13 in Seattle. 37 They use high-quality administrative data from the state of Washington that, unlike many other employer-employee matched datasets, include hours of work. Looking at workers employed in low-wage jobs prior to the minimum wage increase, matched to a comparison group of similar workers who were not affected by the minimum wage, they find that the ordinance increased wages, reduced hours of employment, reduced turnover, and reduced the rate of new entries in the workforce.

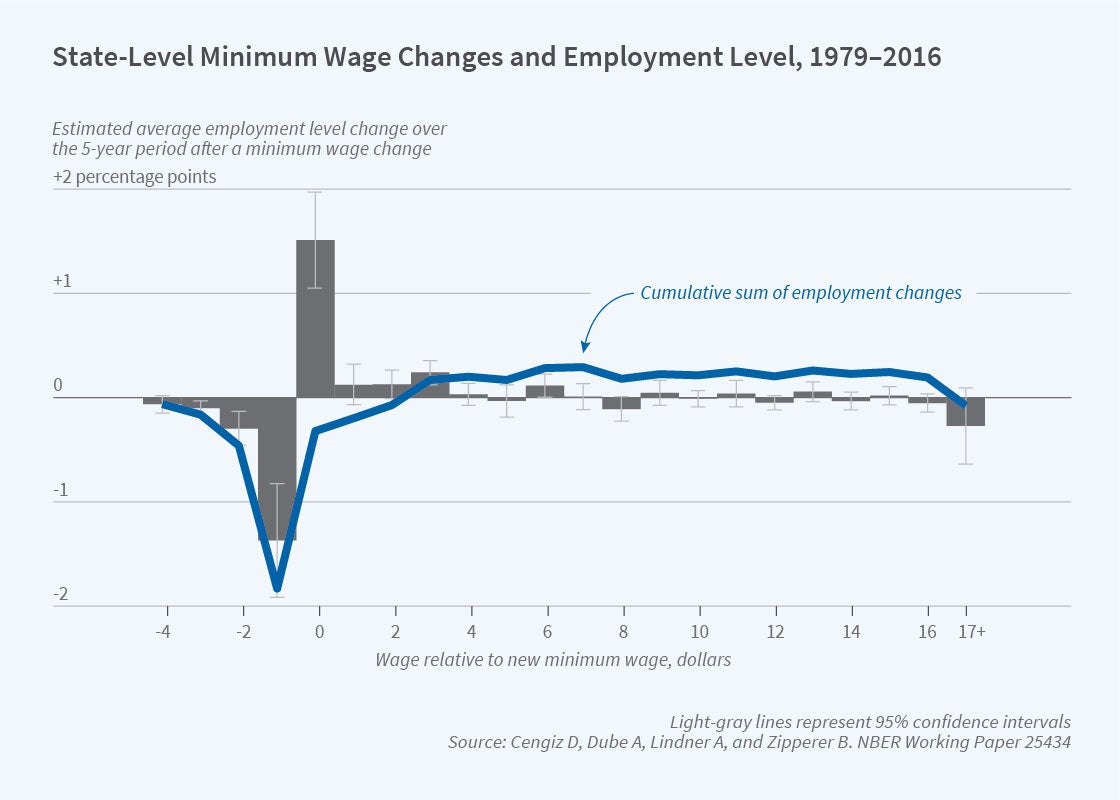

Doruk Cengiz, Arindrajit Dube, Attila Lindner, and Ben Zipperer examine state-level variation in the minimum wage using a bunching estimator approach. 38 They first use a differences-in-differences estimator to estimate the effect of state-level changes in the minimum wage on employment counts in $0.25 buckets around the old and new minimum wage. They then ask whether employment losses below the new minimum wage are offset by employment gains at the new minimum wage and above it (due to spillovers). They find that these are comparable. This result does not mean that no workers lost their jobs, since it remains possible that the minimum wage induced reallocation between firms. 39 However, their conclusion is that in the aggregate there were no significant losses.

As the literature on the minimum wage has evolved, researchers have explored new outcomes and more nuanced margins of adjustment to these policies, such as crime, infant and worker health, family income, and job search effort. Labor Studies researchers have examined the role of the minimum wage in economic, social, and health outcomes such as crime, 40 criminal recidivism, 41 infant health, 42 worker health, 43 family income, 44 automation, 45 and job search effort. 46

Imperfect Competition and Labor Market Concentration

A major theme of Labor Studies researchers has been to test, quantify, and explore the implications of imperfect competition in the labor market. Two broad categories of studies on this topic have been to quantify the firm component of a worker’s pay and to test models of monopsony. Less common, but equally valuable, are studies that show direct evidence on imperfect competition, like the anti-competitive behavior found by Alan Krueger and Orley Ashenfelter among major franchisor employers who used “no-poaching of workers agreements.” 47

Since the seminal work of John Abowd, Francis Kramarz, and David N. Margolis in 1994, 48 a growing body of work has sought to measure firm differences in earnings and wages. Evidence that firms pay identical workers different wages is a violation of the law of one price and evidence of imperfect competition in the labor market. Over the last 10 years, there have been numerous studies on firm pay policies, due in part to the availability of large administrative datasets, increased computing power, and more efficient estimation approaches following the influential work of David Card, J ö rg Heining, and Patrick Kline. 49 A recent focus has been on developing new econometric approaches to correct biases that arise due to limited mobility of workers between firms. Some researchers, such as Stéphane Bonhomme, Kerstin Holzheu, Thibaut Lamadon, Elena Manresa, Magne Mogstad, and Bradley Setzler, have argued that the firm component of pay is less important after taking these biases into account, 50 while others find a more important role for firms as well as evidence of positive sorting between high wages and high-wage firms when appropriately correcting estimates for sampling error. 51 Jae Song, David Price, Fatih Guvenen, Bloom, and Till von Wachter find that changes in the allocation of workers across firms had a substantial role in the rise in earnings inequality between 1978 and 2013. 52 Over this period, high-wage workers increasingly sorted into high-wage firms and also increasingly worked with one another. These two trends accounted for two-thirds of the rise in inequality over this period. Notably, the dispersion of firm-specific pay premiums did not increase; rather, workers who earned high wages elsewhere increasingly clustered at firms that paid larger premiums.

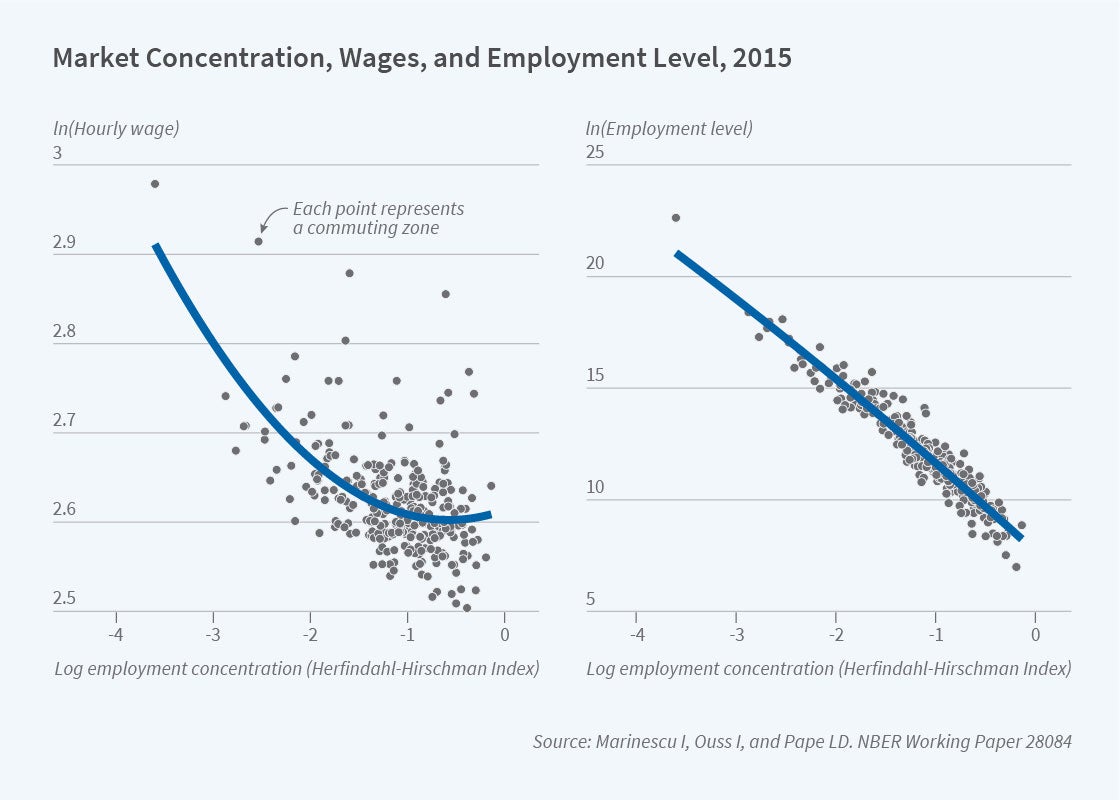

A related literature has sought to test the predictions of monopsonistic competition in the labor market. One class of studies has sought to compute measures of labor market concentration. For example, Ioana Marinescu, Ivan Ouss, and Louis-Daniel Pape calculate labor market concentration measures at the occupation and commuting zone levels in France and find that a 10 percent increase in concentration reduces wages of new hires by 0.9 percent. 53 Their findings accord with other studies that take a similar approach. 54 55 Matthew Kahn and Joseph Tracy note that geographic variation in market power will affect housing rents in a spatial equilibrium model. 56 They find support for this prediction. A second class of monopsony studies seeks to directly estimate a necessary condition of the monopsony model, which is that the labor supply curve facing the firm is upward sloping. Kory Kroft, Yao Luo, Mogstad, and Setzler use the results from procurement auctions as shocks to a firm’s demand curve to effectively trace an upward-sloping labor supply relationship as they observe both employment and average labor earnings increasing following auction wins. 57 Austan Goolsbee and Syverson estimate an upward-sloping labor supply curve in higher education institutions using school-specific labor demand instruments. 58 A third class of studies 59 estimates the negative relationship between wages and separation rates and uses that relationship to quantify the implied elasticity of labor supply facing the firm in a dynamic monopsony model.

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in historic disruptions in labor markets and has drawn new attention to many issues that have been long-standing topics of research in the Labor Studies Program. Assessing the impact of closures of nonessential businesses, of emergency relief programs for workers and firms, of potentially transformative changes in the geography of work, and of many other extraordinary developments over the past year will be an active subject of prospective research. The lessons of this research will guide future policy in response to economic shocks, and will provide new insights on the basic functioning of labor markets.

Researchers

More from nber.

“ Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets ,” Acemoglu D, Restrepo P. NBER Working Paper 23285, March 2017.

“ From Immigrants to Robots: The Changing Locus of Substitutes for Workers ,” Borjas G, Freeman R. NBER Working Paper 25438, January 2019.

“ Do Recessions Accelerate Routine-Biased Technological Change? Evidence from Vacancy Postings ,” Hershbein B, Kahn L. NBER Working Paper 22762, October 2016.

“ COVID-19 and Implications for Automation ,” Chernoff A, Warman C. NBER Working Paper 27249, July 2020.

“ Who Needs a Fracking Education? The Educational Response to Low-Skill Biased Technological Change ,” Cascio E, Narayan A. NBER Working Paper 21359, February 2019.

“ Robots Are Us: Some Economics of Human Replacement ,” Benzell S, Kotlikoff L, LaGarda G, Sachs J. NBER Working Paper 20941, October 2018.

“ Artificial Intelligence and Its Implications for Income Distribution and Unemployment ,” Korinek A, Stiglitz J. NBER Working Paper 24174, December 2017.

“ Demography, Unemployment, Automation, and Digitalization: Implications for the Creation of (Decent) Jobs, 2010–2030 ,” Bloom D, McKenna M, Prettner K. NBER Working Paper 24835, July 2018.

“ The Growing Importance of Social Skills in the Labor Market ,” Deming D. NBER Working Paper 21473, June 2017.

“ Computerization and Immigration: Theory and Evidence from the United States ,” Basso G, Peri G, Rahman A. NBER Working Paper 23935, October 2018.

“ Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment ,” Bloom N, Liang J, Roberts J, Ying Z. NBER Working Paper 18871, March 2013.

Solow, R. “We’d better watch out,” New York Times Book Review, July 12, 1987.

“ Challenges to Mismeasurement Explanations for the US Productivity Slowdown ,” Syverson C. NBER Working Paper 21974, February 2016.

“ The Productivity J-Curve: How Intangibles Complement General Purpose Technologies ,” Brynjolfsson E, Rock D, Syverson C. NBER Working Paper 25148, October 2018.

“ Automation and New Tasks: How Technology Displaces and Reinstates Labor ,” Acemoglu D, Restrepo P. NBER Working Paper 25684, March 2019.

“ Field Experiments on Discrimination ,” Bertrand M, Duflo E. NBER Working Paper 22014, February 2016.

“ Experimental Research on Labor Market Discrimination ,” Neumark D. NBER Working Paper 22022, February 2016.

“ Divergent Paths: Structural Change, Economic Rank, and the Evolution of Black-White Earnings Differences, 1940–2014 ,” Bayer P, Charles K. NBER Working Paper 22797, September 2017.

“ Race Matters: Income Shares, Income Inequality, and Income Mobility for All US Races ,” Akee R, Jones M, Porter S. NBER Working Paper 23733, August 2017.

“ Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective ,” Chetty R, Hendren N, Jones M, Porter S. NBER Working Paper 24441, December 2019.

The Economics of Discrimination , Becker G. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957.

“ Discrimination as a Self-Fulfilling Prophecy: Evidence from French Grocery Stores ,” Glover D, Pallais A, Pariente W. NBER Working Paper 22786, October 2016.

“ Inaccurate Statistical Discrimination: An Identification Problem, ” Bohren J, Haggag K, Imas A, Pope D. NBER Working Paper 25935, July 2020.

“ Employer Neighborhoods and Racial Discrimination ,” Agan A, Starr S. NBER Working Paper 28153, November 2020.

“ Discrimination at the Intersection of Age, Race, and Gender: Evidence from a Lab-in-the-Field Experiment ,” Lahey J, Oxley D. NBER Working Paper 25357, December 2018.

“ Reasonable Doubt: Experimental Detection of Job-Level Employment Discrimination ,” Kline P, Walters C. NBER Working Paper 26861, August 2020.

“ Racial Bias and In-Group Bias in Judicial Decisions: Evidence from Virtual Reality Courtrooms ,” Bielen S, Marneffe W, Mocan N. NBER Working Paper 25355, May 2019.

“ Racial Disparities in Motor Vehicle Searches Cannot Be Justified by Efficiency ,” Feigenberg B, Miller C. NBER Working Paper 27761, August 2020.

“ The Green Books and the Geography of Segregation in Public Accommodations ,” Cook L, Jones M, Rosé D, Logan T. NBER Working Paper 26819, March 2020.

“ Discrimination, Migration, and Economic Outcomes: Evidence from World War I ,” Ferrara A, Fishback P. NBER Working Paper 26936, April 2020.

“ Discrimination and Racial Disparities in Labor Market Outcomes: Evidence from WWII ,” Aizer A, Boone R, Lleras-Muney A, Vogel J. NBER Working Paper 27689, August 2020.

“ Hiring as Exploration ,” Li D, Raymond L, Bergman P. NBER Working Paper 27736, August 2020.

“ Racial Bias in Bail Decisions ,” Arnold D, Dobbie W, Yang C. NBER Working Paper 23421, May 2017.

“ Measuring Racial Discrimination in Bail Decisions ,” Arnold D, Dobbie W, Hull P. NBER Working Paper 26999, October 2020.

“ Human Decisions and Machine Predictions ,” Kleinberg J, Lakkaraju H, Leskovec J, Ludwig J, Mullainathan S. NBER Working Paper 23180, February 2017.

“ The Minimum Wage and the Great Recession: Evidence of Effects on the Employment and Income Trajectories of Low-Skilled Workers ,” Clemens J, Wither M. NBER Working Paper 20724, December 2014.

“ Minimum Wage Increases and Individual Employment Trajectories ,” Jardim E, Long M, Plotnick R, van Inwegen E, Vigdor J, Wething H. NBER Working Paper 25182, October 2018.

“ The Effect of Minimum Wages on Low-Wage Jobs: Evidence from the United States Using a Bunching Estimator ,” Cengiz D, Dube A, Lindner A, Zipperer B. NBER Working Paper 25434, January 2019.

“ Survival of the Fittest: The Impact of the Minimum Wage on Firm Exit ,” Luca D, Luca M. NBER Working Paper 25806, May 2019.

“ Do Minimum Wage Increases Reduce Crime? ” Fone Z, Sabia J, Cesur R. NBER Working Paper 25647, November 2020.

“ The Minimum Wage, EITC, and Criminal Recidivism ,” Agan A, Makowsky M. NBER Working Paper 25116, September 2018.

“ Effects of the Minimum Wage on Infant Health, ” Wehby G, Dave D, Kaestner R. NBER Working Paper 22373, March 2018.

“ Do Minimum Wage Increases Influence Worker Health? ” Horn B, Maclean J, Strain M. NBER Working Paper 22578, August 2016.

“ Minimum Wages and the Distribution of Family Incomes ,” Dube A. NBER Working Paper 25240, November 2018.

“ People versus Machines: The Impact of Minimum Wages on Automatable Jobs ,” Lordan G, Neumark D. NBER Working Paper 23667, January 2018.

“ The Minimum Wage and Search Effort ,” Adama C, Meer J, Sloan C. NBER Working Paper 25128, February 2021.

“ Theory and Evidence on Employer Collusion in the Franchise Sector ,” Krueger A, Ashenfelter O. NBER Working Paper 24831, July 2018.

“ High Wage Workers and High Wage Firms ,” Abowd J, Kramarz F, Margolis D. NBER Working Paper 4917, November 1994.

“ Workplace Heterogeneity and the Rise of West German Wage Inequality ,” Card D, Heining J, Kline P. NBER Working Paper 18522, November 2012.

“ How Much Should We Trust Estimates of Firm Effects and Worker Sorting? ” Bonhomme S, Holzheu K, Lamadon T, Manresa E, Mogstad M, Setzler B. NBER Working Paper 27368, August 2020.

“ Leave-out Estimation of Variance Components ,” Kline P, Saggio R, Solvsten M. NBER Working Paper 26244, September 2019.

“ Firming Up Inequality ,” Song J, Price D, Guvenen F, Bloom N, von Wachter T. NBER Working Paper 21199, June 2015.

“ Wages, Hires, and Labor Market Concentration ,” Marinescu I, Ouss I, Pape L. NBER Working Paper 28084, November 2020.

“ Labor Market Concentration ,” Azar J, Marinescu I, Steinbaum M. NBER Working Paper 24147, February 2019.

“ Strong Employers and Weak Employees: How Does Employer Concentration Affect Wages? ” Benmelech E, Bergman N, Kim H. NBER Working Paper 24307, February 2018.

“ Monopsony in Spatial Equilibrium ,” Kahn M, Tracy J. NBER Working Paper 26295, June 2020.

“ Imperfect Competition and Rents in Labor and Product Markets: The Case of the Construction Industry ,” Kroft K, Luo Y, Mogstad M, Setzler B. NBER Working Paper 27325, August 2020.

“ Monopsony Power in Higher Education: A Tale of Two Tracks ,” Goolsbee A, Syverson C. NBER Working Paper 26070, July 2019.

“ Monopsony in Movers: The Elasticity of Labor Supply to Firm Wage Policies ,” Bassier I, Duba A, Naidu S. NBER Working Paper 27755, August 2020.

NBER periodicals and newsletters may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

© 2023 National Bureau of Economic Research. Periodical content may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

- Departments and Units

- Majors and Minors

- LSA Course Guide

- LSA Gateway

Search: {{$root.lsaSearchQuery.q}}, Page {{$root.page}}

- News and Events

- Commencement

- Undergraduates

- Doctoral Program

- Master of Applied Economics

- Research Seminar in Quantitative Economics

- Economics Subfields at Michigan

- Alumni and Friends

- Masters Program

- Academic Resources & Policies

- Commencement & Graduation

- Events for Economics Majors

- Undergraduate Student Groups

- Requirements for the Major and Minor

- Awards & Scholarships

- Email Group

- Featured Alumni

- Transfer Students, Credits, & Study Abroad

- Awards & Fellowships

- Graduate Student Research

- Past Job Market Placements

- Links for Current PhD Students

- PhD Application Process

- Graduate Student Groups

- Joint Programs

- Current Job Market Candidates

- PhD Application FAQs

- Core Coursework

- MAE Application Process

- MAE Student Advising

- Graduate Economics Society

- Program Requirements

- MAE Student Spotlights

- Visiting Scholars

- Faculty Research

- Economic Impact Analyses

- Economic Outlook Conference

- Related Links

- Subscriptions

- Demographics and Long-Term Forecasts

- Economics Research in the Department

- Field Research Seminars

- U-M Community of Economists

- Economics Research at U-M

- Foster Library

- Economics Resource Links

- Microeconomic Theory

- International Economics

- Industrial Organization

- Health Economics

- Behavioral and Experimental Economics

- Macroeconomics

- Public Finance

- Development Economics

- Economics of Education

- Law and Economics

- Econometrics

- Labor Economics

- Economic History

- Economics of Crime and Punishment

- Gift Giving

- The W.S. Woytinsky Lecture

- Econ Mentoring (Formerly EARN)

- Opportunities to Engage

- U-M Resource Links

- Celebrating Jim Adams

- Economics Leadership Council (ELC)

- In Memoriam

Traditionally, labor economics studies how employers and employees respond to changes in wages, profits, prices and working conditions. Over the past two decades, labor economists have expanded the scope of their research to include much of applied economics. The areas of research spanned by our labor economists include crime, economics of the family, education, discrimination, and other traditional labor topics. Over the last few decades, a major divide arose within labor economics with some labor economists emphasizing the value of natural (and actual) experiments, while others estimating models linked to economic theory. At the University of Michigan, we have labor economists doing both kinds of work, and we get along with each other! In fact, we pride ourselves in being diverse in terms of methods we use, and topics we study.

Faculty in the Field

Primary appointment within the economics department.

Primary Appointment outside the Economics Department

School of Information

Ford School of Public Policy & Department of Economics (courtesy)

Institute for Social Research

School of Education & Department of Economics (courtesy)

Recent Graduate Student Placement Locations

Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland

Federal Reserve Bank of Boston

Stanford University

George Washington University

University of Arizona

Vanderbilt University

University of Kentucky

University of Delaware

University of Memphis

American University

College Board (2)

American Institutes for Research

Ford Motor Company

Yale (postdoc)

SOLO World Partners

Mathematica

Urban Institute

US Treasury

Seminars, Reading Groups, Lunches, etc.

Labor Lunch, Student Seminar (Thursdays)

Labor Seminar (Wednesday afternoons)

Selected Recent Publications

Bleakley, “Thick-market effects and churning in the labor market: Evidence from US cities,” Journal of Urban Economics , 2012. (Joint with Lin.)

Bound, “Reservoir of foreign talent," Science , 2017. (Joint with Khanna & Morales.)

Bound, “The Declining Labor Market Prospects of Less-Educated Men,” Journal of Economic Perspectives , 2019. (Joint with Binder.)

Brown, “The Effects of Respondents’ Consent to be Recorded on Interview Length and Data Quality in a National Panel Study.” Field Methods , 2015. (Joint with McGonagle & Schoeni.)

Heller, “Predicting and Preventing Gun Violence: Experimental Results from READI Chicago” Quarterly Journal of Economics , 2024. (Joint with Monica Bhatt, Max Kapustin, Marianne Bertrand & Chris Blattman.)

Heller, “Information Frictions and Skill Signaling in the Youth Labor Market” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, forthcoming. (Joint with Judd Kessler.)

McCall, "Employment and Job Search Implications of the Extended Weeks and Working While on Claim Pilot Initiatives," Canadian Public Policy/Analyse de Politiques, 2019. (Joint with Lluis.)

Mueller-Smith, “Criminal Justice Involvement, Self-employment, and Barriers in Recent Public Policy” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 2023. (Joint with Keith Finlay and Brittany Street.)

Mueller-Smith, “Does Welfare Prevent Crime? The Criminal Justice Outcomes of Youth Removed from SSI” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2022. (Joint with Manasi Deshpande.)

Reynoso, “Marriage market and labor market sorting,“ Review of Economic Studies , accepted, 2023. (Joint with Calvo & Lindenlaub.)

Reynoso, “Education Quality and Teaching Practices,” Economic Journal, 2020. (Joint with Bassi & Meghir.)

Reynoso, “The impact of divorce laws on the equilibrium in the marriage market,” Journal of Political Economy, accepted, 2024.

Stephens, “Compulsory Education and the Benefits of Schooling,” American Economic Review , 2014. (Joint with Yang.)

Stephens, “Disability Benefit Take-Up and Local Labor Market Conditions,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 2018. (Joint with Charles & Li.)

Stevenson and Wolfers, “Subjective and Objective Indicators of Racial Progress,” Journal of Legal Studies , 2012.

Zafar, “Gender Differences in Job Search and the Earnings Gap: Evidence from Business Majors” Quarterly Journal of Economics , 2023. (Joint with Patricia Cortes, Jessica Pan, Laura Pilossoph, and Ernesto Reuben.)

Zafar. “Ask and You Shall Receive? Gender Differences in Regrades in College”. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy , 2023 (with Cher Li.)

Office Hours: M-F 8 am - 4:30pm

- Information For

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Faculty and Staff

- More about LSA

- How Do I Apply?

- LSA Magazine

- Student Resources

- Academic Advising

- Global Studies

- LSA Opportunity Hub

- Social Media

- Update Contact Info

- Privacy Statement

- Report Feedback

Let your curiosity lead the way:

Apply Today

- Arts & Sciences

- Graduate Studies in A&S

Topics in Labor Economics I

Economics 583.

Browse Course Material

Course info, instructors.

- Prof. Daron Acemoglu

- Prof. Joshua Angrist

Departments

As taught in.

- Labor Economics

Learning Resource Types

Labor economics i, empirical project .

This project asks you to review, replicate, and extend an empirical paper from our reading list. Please choose a paper not covered in detail in class.

Your essay should have three components, outlined below.

A. Overview

- What question does the study ask and in what context: Why is this of economic interest? What are the most important findings in the paper?

- Describe an ideal research design for the question at hand. Which assumptions support a causal interpretation of the results presented in your chosen paper? Are these assumptions discussed appropriately? Are the econometric techniques used in the study likely to yield estimates with a causal interpretation? Do these techniques appear to have been correctly implemented? Are the results convincing?

- Finally, the bulk of this part should consider where this paper fits in the relevant literature. What were the findings at the time the paper was written? What is this paper’s contribution? What has been done on this topic since this paper was published? Are the paper’s findings still relevant?

B. Replication

- Identify the main findings and use the authors’ data to replicate the published findings if possible. If the data are unavailable, construct comparable estimates using a data set of your choosing. (Choose a data set you’d expect to generate similar results).

- Summarize and compare your replication results to the original results, with original and replication results reported side-by-side in a single table. Highlight any differences. Explain why you think your results differ from the original (if they do).

C. Extension

- Extend the work in some way. Do this either by (a) estimating alternative specifications that may illuminate issues and questions raised by the paper (e.g., specification checks or subsamples of special interest), or (b) collecting new data and producing results for this new sample. Any analysis of new data should include specification and robustness checks of the sort you would hope to see in a published empirical study of this nature.

- The product of this exercise is an essay, much like those you will spend your life writing. Start polishing your writing skills now rather than the summer before you go on the job market. For starters, pick a style guide and master the contents ( The Elements of Style , for example). Once you’ve mastered basic composition, learn how to write about numbers by imitating the good work of others.

You are leaving MIT OpenCourseWare

Labor and Public Economics

Faculty in the Labor and Public Economics group at Yale work on a broad range of research, including the effects of taxes and welfare programs, wage and employment determination, education economics, and the analysis of racial and gender discrimination.

With strong senior and junior faculty, Yale has a diverse and vibrant group in labor and public economics. The faculty in labor economics are active in research on traditional topics such as the development of individual careers and human capital accumulation, as well as newer areas such as the labor market implications of health care reform, financial literacy, and behavioral economics. The faculty in public economics come together from several other sub-fields in the Economics Department. These include macro faculty who do theoretical public finance, environmental faculty who work on policies to address climate change, and health economists who work on health care policy. Several of our labor and development faculty also work on public policy issues.

The Cowles Foundation provides a uniquely supportive environment for work in labor and public economics. In addition to providing direct research support for faculty and graduate students, the Cowles Foundation funds a regular influx of short term and long term academic visitors, postdocs, and doctoral students from other institutions, who contribute to the research atmosphere in labor and public economics.

Seminars and Conferences

The Labor and Public Economics Program hosts two regular seminars. The Labor/Public Economics Workshop hosts top scholars from around the world who present their latest research. The Labor/Public Economics Prospectus Workshop is a more informal workshop designed primarily for graduate students working in labor economics and public finance to present research in progress. Faculty and visitors also use the workshop to present work in its early stages.

Every year, the Labor and Public Economics Program hosts a summer conference to bring together top economists in the field to present new research. Recent research topics have included the origins of the US opioid epidemic, the development of new tools to measure the tolerance of political regimes, the role of inheritances in the determination of wealth inequality, and the fiscal policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic, with a focus on the impact of expanded unemployment benefits on labor markets and household spending.

For more information about the Labor and Public summer conferences, see the Cowles Conferences and Workshops page .

Graduate Teaching and Research

The Department offers a two-semester sequence in Labor Economics (630 and 631). The first semester of the sequence includes topics such as static and dynamic approaches to demand, human capital and wage determination, wage income inequality, unemployment and minimum wages, matching and job turnover, implicit contract theory, and the efficiency wage hypothesis. The second semester covers static and dynamic models of labor supply, firm-specific training, compensating wage differentials, discrimination, household production, bargaining models of household behavior, intergenerational transfers, and mobility.

The Department also offers a two-semester sequence in Public Finance (680 and 681). The sequence covers theories of government provision of public goods, moral hazard, and adverse selection. Empirical methodologies vary from standard reduced-form techniques to structural estimation. Substantive areas include health economics, taxation, social security, and non-health components of government spending.

For detailed field descriptions, please see the Department’s PhD Program Page .

- EMU Library

- Research Guides

Labor Economics

- Articles & Journals

- Statistics & Government

Indexes to Articles

- EconLit This link opens in a new window Premier index to economic literature. From the American Economic Association, it indexes 600+ international economics journals from 1969 - present. Includes every major topic, & most minor topics, in economics research. Citations for collective works, dissertations, & annotations of new books are included. Corresponds to the Index of Economics Articles, & in part corresponds to the Journal of Economic Literature (articles are excluded) as well as the online version, Economic Literature Index.

- ProQuest One Business This link opens in a new window Includes in-depth coverage for 3,040+ publications (2,060+ available full text). Offers the latest business & financial information for researchers at all levels. With ABI/INFORM Global, users can find out about business conditions, management techniques, business trends, management practice/theory, corporate strategy & tactics, & competitive landscape. Search Instruction : ABI/INFORM Quick Guide

Find Full Text Articles

No direct link to full text in the database? Click on the EMU Findtext+ link or button.

Getting full-text articles has detailed instructions.

- Journal of Labor Economics Since 1983, has presented international research that examines issues affecting the economy as well as social and private behavior. Publishes both theoretical and applied research results relating to U.S. and international data. Its contributors investigate various aspects of labor economics, including supply and demand of labor services, personnel economics, distribution of income, unions & collective bargaining, applied and policy issues in labor economics, and labor markets & demographics.

- Labour Economics Publishes research in labor economics, on micro-economic & macro-economic levels, in a mix of theory, empirical testing & policy applications. Recognizes analysis/explanation of institutional arrangements of labor markets & their impact on labor market outcomes. Occasionally publishes review articles & sections on special topics, theoretical developments, comparative policies or subjects of interest to labor economists and labor market students. Special issues publish quality conference papers.

- Journal of Labor Research Outlet for original research on behavior affecting labor market outcomes. Forum for empirical & theoretical research on U.S. & international labor markets, and labor/employment issues. Publishes on issues relating to labor markets & employment relations, including labor demand/supply, personnel economics, unions/collective bargaining, employee participation, dispute resolution, labor market policies, employment relationships and interplay between labor market variables & economic outcomes.

- Review of Labour Economics and Industrial Relations Provides a forum for analysis and debate on issues concerning labor economics and industrial relations. Publishes high quality contributions that combine economic theory and statistical methodology in order to analyze behavior, institutions and policies relevant to the labor market.

- Demography Scientific literature & general-interest info for demographers, with a disciplinary emphasis on social sciences, biology, epidemiology, geography, history, public health, & statistics. Focuses on original research, with accompanying review articles. Recent topics: affirmative action, fertility, population, contraceptives, role of women, chronic diseases, & population trends. Authors make data sets available for three years after publication. Review from: 2009 Magazines for Libraries: Kahl, Chad

- Labour and Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work Australian publication covers industrial relations, industrial sociology, labor economics, labor law, labor history, organization studies, labor process studies, political economy, management, public policy, and administration. Review from Ulrich's Periodicals Online: 2009.

- Labor Studies Journal Multidisciplinary; publishes research on work, workers, labor organizations, labor studies, and worker education (U.S. & worldwide). Covers qualitative & quantitative research methods. For the general audience: union, university, & community-based labor educators, and labor activists/scholars from social sciences & humanities. Official journal of United Association for Labor Education (UALE). Publishes UALE conference papers. Review from Magazines for Libraries:(Jan 12, 2009) by Huwe, Terence K.

- Monthly Labor Review (MLR) E-journal; excellent usability, with some abstracts & article excerpts readable at the top level. Full-text in PDF. Articles link to related Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) programs/data. "The Editor's Desk," a review of new BLS data & research, updates Monday-Friday. Informative and neutral, covers current labor statistics, book reviews, publications received, and a section called "Labor Month in Review." Review from Magazines for Libraries:(Jan 12, 2009; ISSN: 1937-4658)by Terrence K. Huwe.

- National Bureau of Economic Research Working Papers NBER Working Papers have not undergone the review accorded official NBER publications; in particular, they have not been submitted for approval by the Board of directors. They are intended to make results of NBER research available to other economists in preliminary form to encourage discussion and suggestions for revision before final publication.

- Population Studies Peer-reviewed journal on demography; published 3x/year. Aims to cover research that is contemporary & historical; qualitative & quantitative; on developed & developing countries; and analytical & reviewing. Typically includes 5 - 7 research articles, review essays and/or research notes, & 4 - 6 book reviews. Recent topics: marriage, childbirth, sterility, labor, mortality, suicide, household income, and health. Review from Magazines for Libraries (Jan 12, 2009; ISSN: 0032-4728) Kahl, Chad

Find Journals by Title

Find Journals & Other Periodicals by Title

Search here for journal, magazine or newspaper titles. If you're looking for articles on a topic, use the databases .

Examples: Newsweek , Journal of Educational Psychology .

- Economics by Amy Fyn Last Updated May 7, 2024 58 views this year

- Business by Amy Fyn Last Updated May 7, 2024 133 views this year

- Next: Books >>

Ask a Librarian

Use 24/7 live chat below or:

In-person Help Summer 2024 Mon-Thur, 11am - 3pm

Email or phone replies

Appointments with librarians

Access Library and Research Help tutorials

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 11:53 AM

- URL: https://guides.emich.edu/labor

UCL Department of Economics

ECON0062 - Topics in Labour Economics

This course provides an overview of key topics in the field of labour economics. More specifically, the course:

- teaches the key elements of labour economics

- uses labour economics to say something about how real world phenomena related to the labour market work

- shows how models in labour economics derived from first order principles can inform empirical analysis and policy

- is strongly empirically motivated, but also stresses the links between theoretical and empirical research

- touches at commonly used empirical methods to obtain causal effects (difference-in-differences, instrumental variables, regression discontinuity)

- covers key papers (often written 15-20 years ago) in conjunction with related (unpublished) papers at the current research frontier

Course outline:

- Lecture 1: Human Capital and Wages

- Lecture 2: The Sources of Wage Growth

- Lecture 3: The Structure of Wages and Inequality of Earnings I

- Lecture 4: Inequality: Supply, Demand, Institutions, and Polarisation

- Lecture 5: Discrimination and Symmetric Employer Learning

- Lecture 6: Asymmetric Information and Labour Markets

- Lecture 7: Self-Selection and the Roy Model

- Lecture 8: Monopsony in the Labour Market and Minimum Wages

- Lecture 9: The Effect of Migration on Wages and Employment

- Lecture 10: Social Interactions, Networks, and Neighbourhood Effects

Widget Placeholder http://mediacentral.ucl.ac.uk/Player/8323

"I feel the course provided me with a far more sophisticated understanding of macroeconomic policy and a wealth of useful technical econometrics skills"

Widget Placeholder https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=68J5HqGhI00

UCL Graduate Prospectus

Still have questions? Follow the link below to a list of frequently asked questions.

Economics Handbook for MSc Students

If you have any questions please refer to the Frequently Asked Questions section of this website.

For further information please see the UCL pages for current students , or contact: [email protected]

FOCUS AREAS

Major research initiative, labor market issues, research topics.

- Employment Relationships

- Globalization

- Immigration

- International Labor Comparisons

- Job Security & Unemployment Dynamics

- Occupational Regulation & Licensing

- Retirement & Pensions

- Wages, Health Insurance & Benefits

- Work & Family Balance

Jobs are changing, and the future of work will challenge many long-held assumptions about employment. Upjohn Institute research explores evolving struggles over wages, inequality, immigration and regulations and emerging trends of gig work, automation and offshoring.

Latest Research Highlights

Research details declining working class, increasing inequality over four decades, pandemic restrictions and shutdowns don't have lasting effect on jobs, new research finds, forewarning michigan’s announced mass layoffs under the warn act.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Is College Worth It?

1. labor market and economic trends for young adults, table of contents.

- Labor force trends and economic outcomes for young adults

- Economic outcomes for young men

- Economic outcomes for young women

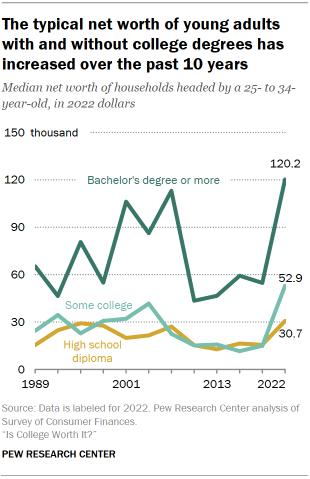

- Wealth trends for households headed by a young adult

- The importance of a four-year college degree

- Getting a high-paying job without a college degree

- Do Americans think their education prepared them for the workplace?

- Is college worth the cost?

- Acknowledgments

- The American Trends Panel survey methodology

- Current Population Survey methodology

- Survey of Consumer Finances methodology

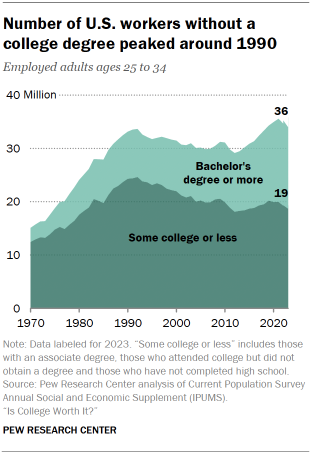

A majority of the nation’s 36 million workers ages 25 to 34 have not completed a four-year college degree. In 2023, there were 19 million young workers who had some college or less education, including those who had not finished high school.

The overall number of employed young adults has grown over the decades as more young women joined the workforce. The number of employed young adults without a college degree peaked around 1990 at 25 million and then started to fall, as more young people began finishing college .

This chapter looks at the following key labor market and economic trends separately for young men and young women by their level of education:

Labor force participation

- Individual earnings

Household income

- Net worth 1

When looking at how young adults are doing in the job market, it generally makes the most sense to analyze men and women separately. They tend to work in different occupations and have different career patterns, and their educational paths have diverged in recent decades.

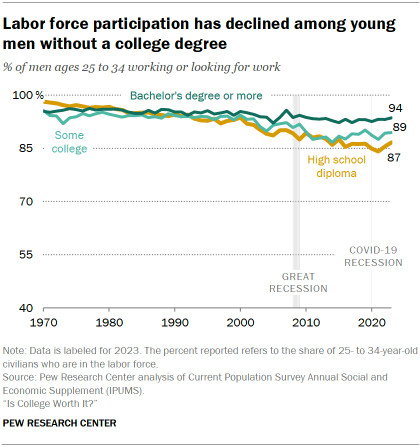

In 1970, almost all young men whose highest educational attainment was a high school diploma (98%) were in the labor force, meaning they were working or looking for work. By 2013, only 88% of high school-educated young men were in the labor force. Today, that share is 87%.

Similarly, 96% of young men whose highest attainment was some college education were in the labor force in 1970. Today, the share is 89%.

By comparison, labor force participation among young men with at least a bachelor’s degree has remained relatively stable these past few decades. Today, 94% of young men with at least a bachelor’s degree are in the labor force.

The long-running decline in the labor force participation of young men without a bachelor’s degree may be due to several factors, including declining wages , the types of jobs available to this group becoming less desirable, rising incarceration rates and the opioid epidemic . 2

Looking at labor force and earnings trends over the past several decades, it’s important to keep in mind broader forces shaping the national job market.

The Great Recession officially ended in June 2009, but the national job market recovered slowly . At the beginning of the Great Recession in the fourth quarter of 2007, the national unemployment rate was 4.6%. Unemployment peaked at 10.4% in the first quarter of 2010. It was not until the fourth quarter of 2016 that unemployment finally returned to its prerecession level (4.5%).

Studies suggest that things started to look up for less-skilled workers around 2014. Among men with less education, hourly earnings began rising in 2014 after a decade of stagnation. Wage growth for low-wage workers also picked up in 2014. The tightening labor markets in the last five years of the expansion after the Great Recession improved the labor market prospects of “vulnerable workers” considerably.

The COVID-19 pandemic interrupted the tight labor market, but the COVID-19 recession and recovery were quite different from the Great Recession in their job market impact. The more recent recession was arguably more severe, as the national unemployment rate reached 12.9% in the second quarter of 2020. But it was short – officially lasting two months, compared with the 18-month Great Recession – and the labor market bounced back much quicker. Unemployment was 3.3% before the COVID-19 recession; three years later, unemployment had once again returned to that level.

Full-time, full-year employment

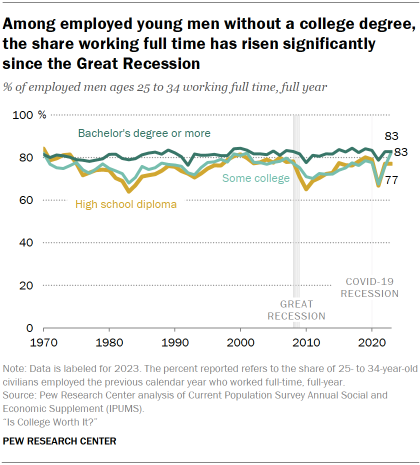

Since the Great Recession of 2007-09, young men without a four-year college degree have seen a significant increase in the average number of hours they work.

- Today, 77% of young workers with a high school education work full time, full year, compared with 69% in 2011.

- 83% of young workers with some college education work full time, full year, compared with 70% in 2011.

The share of young men with a college degree who work full time, year-round has remained fairly steady in recent decades – at about 80% – and hasn’t fluctuated with good or bad economic cycles.

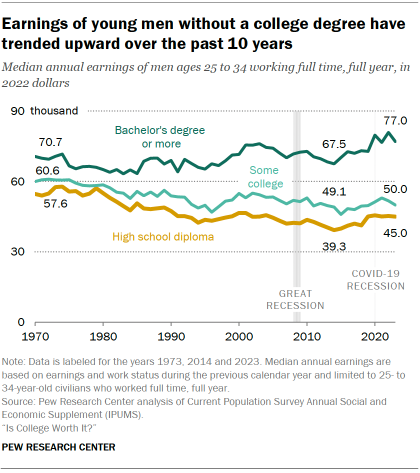

Annual earnings

Annual earnings for young men without a college degree were on a mostly downward path from 1973 until roughly 10 years ago (with the exception of a bump in the late 1990s). 3

Earnings have been increasing modestly over the past decade for these groups.

- Young men with a high school education who are working full time, full year have median earnings of $45,000 today, up from $39,300 in 2014. (All figures are in 2022 dollars.)

- The median earnings of young men with some college education who are working full time, full year are $50,000 today, similar to their median earnings in 2014 ($49,100).

It’s important to note that median annual earnings for both groups of noncollege men remain below their 1973 levels.

Median earnings for young men with a four-year college degree have increased over the past 10 years, from $67,500 in 2014 to $77,000 today.

Unlike young men without a college degree, the earnings of college-educated young men are now above what they were in the early 1970s. The gap in median earnings between young men with and without a college degree grew significantly from the late 1970s to 2014. In 1973, the typical young man with a degree earned 23% more than his high school-educated counterpart. By 2014, it was 72% more. Today, that gap stands at 71%. 4

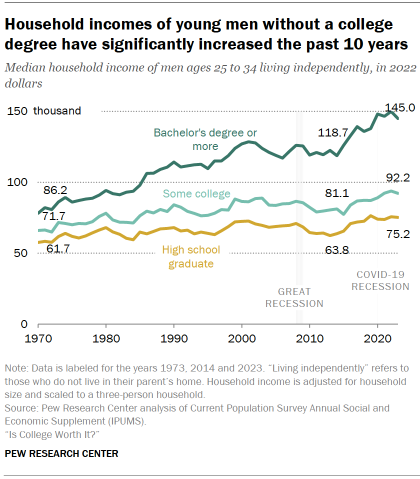

Household income has also trended up for young men in the past 10 years, regardless of educational attainment.

This measure takes into account the contributions of everyone in the household. For this analysis, we excluded young men who are living in their parents’ home (about 20% of 25- to 34-year-old men in 2023).

- The median household income of young men with a high school education is $75,200 today, up from $63,800 in 2014. This is slightly lower than the highpoint reached around 2019.

- The median household income of young men with some college education is $92,200 today, up from $81,100 in 2014. This is close to the 2022 peak of $93,800.

The median household income of young men with at least a bachelor’s degree has also increased from a low point of $118,700 in 2014 after the Great Recession to $145,000 today.

The gap in household income between young men with and without a college degree grew significantly between 1980 and 2014. In 1980, the median household income of young men with at least a bachelor’s degree was about 38% more than that of high school graduates. By 2014, that gap had widened to 86%.

Over the past 10 years, the income gap has fluctuated. In 2023, the typical college graduate’s household income was 93% more than that of the typical high school graduate.

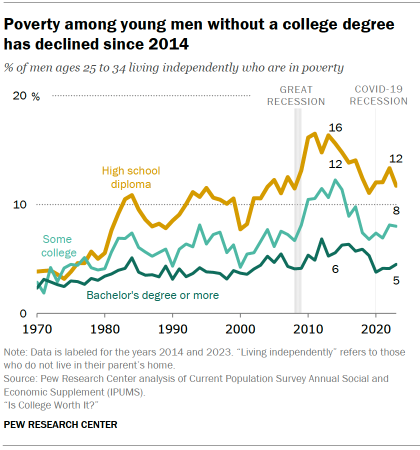

The 2001 recession and Great Recession resulted in a large increase in poverty among young men without a college degree.

- In 2000, among young men living independently of their parents, 8% of those with a high school education were in poverty. Poverty peaked for this group at 17% around 2011 and has since declined to 12% in 2023.

- Among young men with some college education, poverty peaked at 12% around 2014, up from 4% in 2000. Poverty has fallen for this group since 2014 and stands at 8% as of 2023.

- Young men with a four-year college degree also experienced a slight uptick in poverty during the 2001 recession and Great Recession. In 2014, 6% of young college graduates were in poverty, up from 4% in 2000. Poverty among college graduates stands at 5% in 2023.

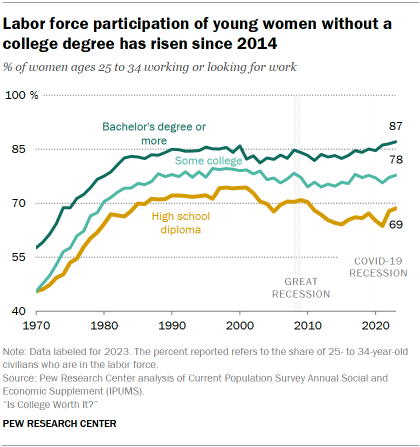

Labor force trends for young women are very different than for young men. There are occupational and educational differences between young women and men, and their earnings have followed different patterns.

Unlike the long-running decline for noncollege young men, young women without a college degree saw their labor force participation increase steadily from 1970 to about 1990.

By 2000, about three-quarters of young women with a high school diploma and 79% of those with some college education were in the labor force.

Labor force participation has also trended upward for college-educated young women and has consistently been higher than for those with less education.

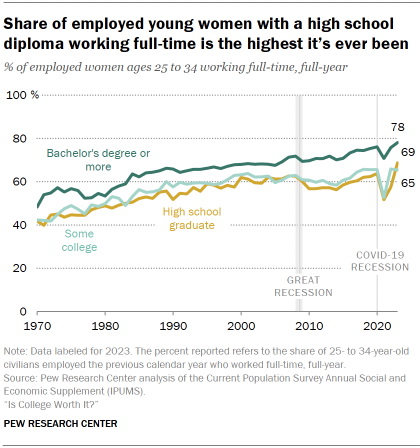

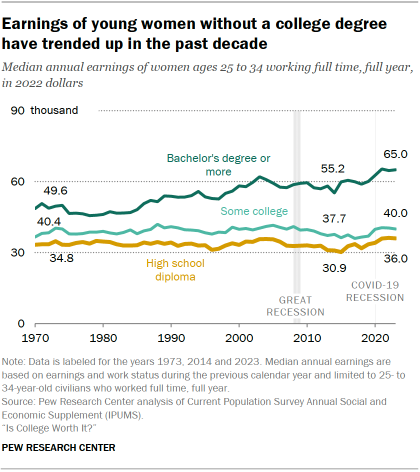

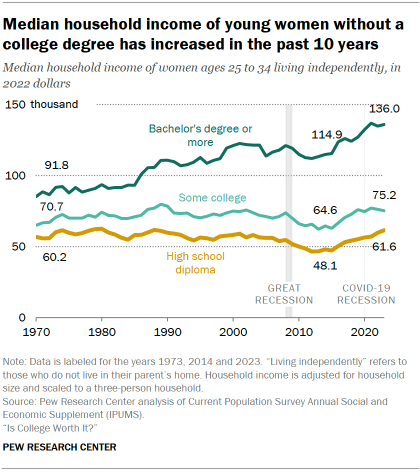

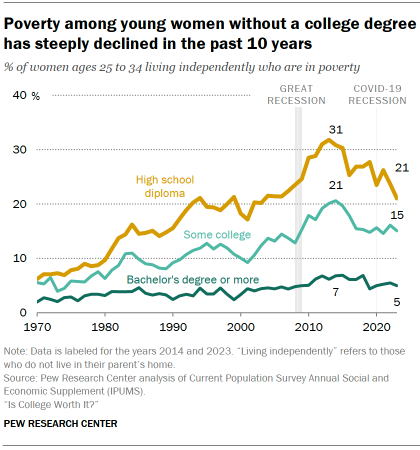

After rising for decades, labor force participation for young women without a college degree fell during the 2001 recession and the Great Recession. Their labor force participation has increased slightly since 2014.