Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published: 18 July 2023

Evidence and reporting standards in N-of-1 medical studies: a systematic review

- Prathiba Natesan Batley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5137-792X 1 ,

- Erica B. McClure 2 ,

- Brandy Brewer 1 ,

- Ateka A. Contractor 3 ,

- Nicholas John Batley 4 ,

- Larry Vernon Hedges 5 &

- Stephanie Chin 1

Translational Psychiatry volume 13 , Article number: 263 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2378 Accesses

2 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

- Scientific community

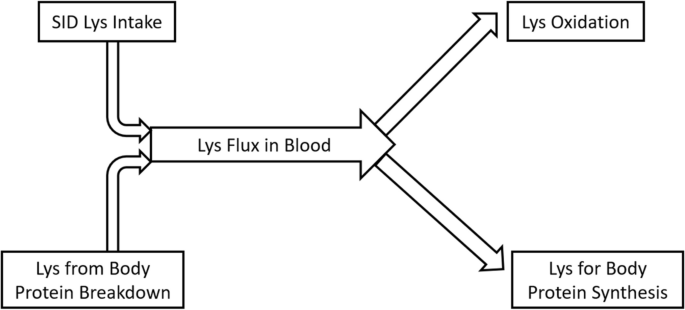

N-of-1 trials, a special case of Single Case Experimental Designs (SCEDs), are prominent in clinical medical research and specifically psychiatry due to the growing significance of precision/personalized medicine. It is imperative that these clinical trials be conducted, and their data analyzed, using the highest standards to guard against threats to validity. This systematic review examined publications of medical N-of-1 trials to examine whether they meet (a) the evidence standards and (b) the criteria for demonstrating evidence of a relation between an independent and an outcome variable per the What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) standards for SCEDs. We also examined the appropriateness of the data analytic techniques in the special context of N-of-1 designs. We searched for empirical journal articles that used N-of-1 design and published between 2013 and 2022 in PubMed and Web of Science. Protocols or methodological papers and studies that did not manipulate a medical condition were excluded. We reviewed 115 articles; 4 (3.48%) articles met all WWC evidence standards. Most (99.1%) failed to report an appropriate design-comparable effect size; neither did they report a confidence/credible interval, and 47.9% reported neither the raw data rendering meta-analysis impossible. Most (83.8%) ignored autocorrelation and did not meet distributional assumptions (65.8%). These methodological problems could lead to significantly inaccurate effect sizes. It is necessary to implement stricter guidelines for the clinical conduct and analyses of medical N-of-1 trials. Reporting neither raw data nor design-comparable effect sizes renders meta-analysis impossible and is antithetical to the spirit of open science.

Similar content being viewed by others

Translating evidence into practice: eligibility criteria fail to eliminate clinically significant differences between real-world and study populations

Individualized therapy trials: navigating patient care, research goals and ethics

Mendelian randomisation for psychiatry: how does it work, and what can it tell us?

Introduction.

N-of-1 studies, which are special cases of single case experimental designs (SCEDs), are important in the medical field, where treatment decisions may be made for an individual patient, or where large-scale trials are not always possible or even appropriate such as when treating rare diseases, comorbid conditions, or concurrent therapies [ 1 ]. In fact, n-of-1 trials have been suggested as a valuable scientific method in precision medicine [ 2 ] and are particularly important in the field of psychiatry. Recently, the British Journal of Psychiatry published a special issue focusing on precision medicine and personalized healthcare in psychiatry. The What Works Clearinghouse (WWC [ 3 , 4 ]) standards for SCEDs noted several requirements to increase rigor pertaining to evidence standards and demonstration of treatment effect between the independent and the outcome variable. It is important to note here that the term outcome variable refers to the dependent variable and not a medical outcome such as morbidity, mortality, etc. The purpose of these standards is to address validity concerns in SCEDs. What is unclear is if these important standards have been adopted in medical research. To this end, we conducted a systematic literature review using the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Literature Reviews and Meta-analyses) guidelines to address the following aims:

To examine whether N-of-1 trials meet WWC evidence standards; namely, independent variables being systematically manipulated, outcome variables measured systematically over time by more than one assessor, interobserver agreement data being collected in each phase for at least 20% of data points per condition, including 3 or more attempts to demonstrate a treatment effect at three different points in time, and having the number of required data points per case/phase,

To examine whether evidence of a treatment effect is examined in N-of-1 trials per WWC standards (namely, immediacy, consistency, changes in level/trend, and effect sizes), and

To examine the data and methodological characteristics of the studies such as phase lengths, inclusion of autocorrelation, appropriateness of the type of analysis for the data type, sensitivity, and subgroup analyses.

Although the SPENT (SPIRIT extension for N-of-1 trials) checklist [ 5 ] has been developed specifically for n-of-1 protocols, we chose the WWC standards because the former focuses on improving the completeness and transparency of N-of-1 protocols, whereas the latter focuses on addressing threats to validity and reporting guidelines to establish evidence of treatment effect between the independent and the outcome variable. Therefore, the latter speaks more to the validity aspects of N-of-1 trials.

Literature search

Inclusion/exclusion criteria.

The review followed the 2020 PRISMA recommendations [ 6 ] (Supplementary Table 1 ) and guidelines from the Cochrane Collaboration for data extraction and synthesis [ 7 ]. Included studies were peer-reviewed, published in medical journals, examined medical outcomes, used SCED/N-of-1, were empirical articles, and in the English language. Only medical conditions listed in International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) [ 8 ] or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [ 9 ] were included in the present study to retain a meaningful scope and align with widely used clinical practices. Online Supplementary Table 1 gives the PRISMA checklist and how they were met for the current study.

Search strategy

The following databases were searched: PubMed and Web of Science. These databases were chosen because these search engines have reproducible search results in different locations and at different times. Exact search terms were: "n-of-1*" OR "N-of-1 trial" OR "N-of-1 design" OR "single case design" OR “single subject design” OR “single case experimental design” AND “drug” OR “therapy” OR “intervention” OR “treatment” in the title, abstract, or keywords. The dates of publication were restricted to between January 1, 2013 and May 3, 2022 for relevance, sufficiency, and feasibility as the WWC Standards for SCEDs were published in 2010 and later in 2013. The search ended on May 3, 2022.

Data management

References and abstracts of articles found from the initial search were downloaded into the reference management software EndNote. Duplicate reference entries were removed. The remaining reference entries were transported to a Google Sheets file by and for independent review by two co-authors (EM and BB) for inclusion criteria. Reliability of electronic search results was established through replication of the electronic search and an inter-rater comparison of the number of identified articles (100% agreement).

Selection process

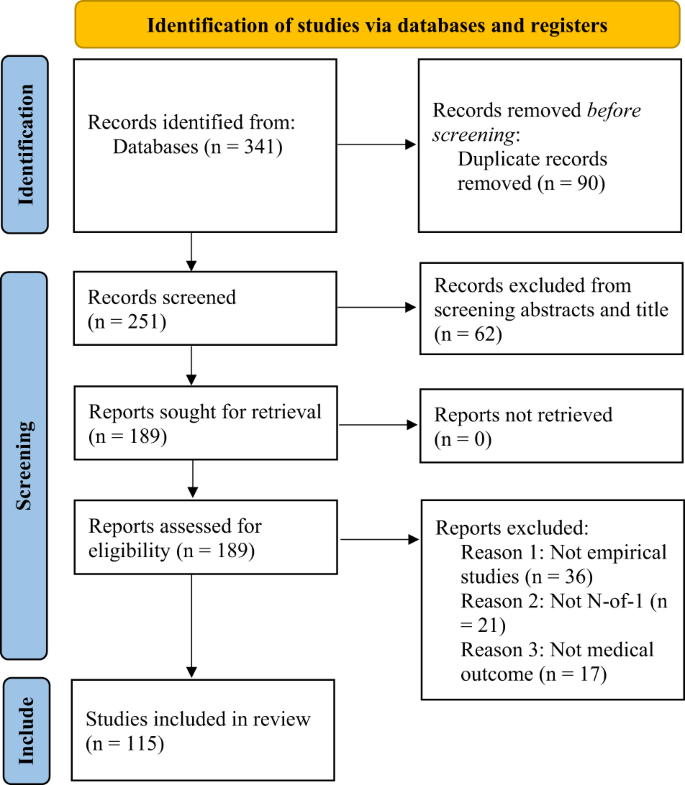

Two co-authors independently (EM and BB) screened 341 articles (title and article abstract review) to determine eligibility of articles for the current review. From this initial screening, 189 articles were identified as potentially eligible and were subjected to a second screening. The two co-authors then independently reviewed the 189 articles (full text) to ensure their eligibility for this review. Articles that were not empirical work (e.g., protocol, commentary), and articles that were not N-of-1 trials or did not have a medical outcome variable were excluded independently leading to a total of 115 articles that met all inclusion criteria (100% agreement).

Coding process

There were 4 coders. Two were experts in statistical methodology and three were experts in SCEDs. One co-author (EM), as the primary coder, conducted data extraction from 115 eligible articles. To obtain inter-reliability estimates, 30 (26.09%) of the included articles were additionally coded by two other co-authors (BB and SC) through random assignment. Before coding the articles included in the review, researchers calibrated coding reliability by using the coding tool to analyze studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Interobserver agreements during calibration were measured at 94.3%. When discussing whether a specific study met an individual indicator, areas of incongruity were discussed until researchers reached consensus. Once reliability above 90% was established, researchers began coding the articles included in the review (coding tool available from first author). Interobserver agreement for all coded articles was measured at 93.1%. Finally, the first author (PNB) recoded all the articles to ensure 100% agreement between the first author and the coding of the other three co-authors.

Risk of bias assessment

as given by the Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews Tool (ROBIS) ( http://www.bristol.ac.uk/population-health-sciences/projects/robis/ ) is in Table 1 . Additionally, the online Supplementary Table 2 gives the risk of bias in not meeting evidence standards, in reporting treatment effect, and in inappropriate data analysis for each study.

Rating evidence

All studies were N-of-1 studies. According to Oxford center for evidence-based medicine (OCEBM, https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/files/levels-of-evidence/cebm-levels-of-evidence-2-1.pdf ) all these studies will be level 3 studies because they manipulate the control arm of a randomized trial (Fig. 1 ).

The number of articles identified, screened, retrieved, assessed, and finally retained. n represents the sample size.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis such as frequency and percentages are reported. Table 2 outlines information on number of studies meeting the WWC [ 3 , 4 ] requirements for meeting evidence standards. Table 3 outlines information on number of studies demonstrating how treatment effect was determined per WWC standards [ 3 , 4 ] (immediacy, changes in level/trend, effect sizes/confidence or credible intervals, consistency, effect sizes), and different methodological characteristics (e.g., type of analysis conducted, whether this was appropriate for the data [if data met the assumptions of the analyses], and whether autocorrelations were included in the models). Additionally, we coded the characteristics of the study such as the number of phases, phase length, type of outcome variable, types of effect sizes, data distribution assumptions met, accounting for carryover effect, intraclass correlation, sensitivity analysis, and subgroup analysis.

As outlined in Table 2 , of the 115 studies, 68 (59.13%) did not identify the type of SCED used. Therefore, we identified these designs. To answer research question 1 about how many studies passed all the WWC criteria: only 4 (3.48%) studies passed all the WWC criteria for meeting evidence standards (see online Supplementary Table 2 ). Specifically, IOA (interobserver agreement) was not collected in each phase for at least 20% of data points per condition for 95.7% of the cases. It is possible that sometimes this is not applicable when the outcome variable is measured using an instrument and not necessarily by observers. However, this was the case for only 3 (2.6%) of the studies. 39.3% of the studies did not include ≥ 3 attempts to demonstrate a treatment effect at three different points in time which is a threat to validity because at least 3 independent demonstrations of treatment effect are required to show that the treatment effect did not happen due to random variation in data. Demonstrating a treatment effect at least 3 times is important in N-of-1 studies because the question of whether the treatment effect is replicable across phases or cases is answered by this demonstration, which has obvious impact on validity. 24.8% of them did not have the number of required data points (3–5) per case/phase. This means that the studies were terribly underpowered. It is impossible to obtain reliable estimates of phase means or worse yet, determine if the treatment effect varied with time.

Regarding research question 2, as outlined in Table 3 , most studies (98.3%) determined change in level between phases to report evidence of treatment effects. Consistency was not investigated by 72.6% of the studies and 38.5% of the studies did not report any effect size. The most reported effect size was an unstandardized mean difference between the phases which ranged from −8 to 100. Further, 60.7% of the studies did not report a confidence/credible interval estimate for effect size. The issue with simply reporting an unstandardized mean difference effect size is that there are no units to understand the metric of the effect size. For instance, an unstandardized mean difference of 3 units would be a significant drop in hemoglobin A1C versus a trivial 3 unit drop in systolic blood pressure.

Regarding question 3, only 6% of the studies determined immediacy which is a requirement for causal evidence in SCEDs. Immediacy informs the researcher as to how immediately a treatment took effect, so it eliminates any other extraneous reason for a change in the outcome variable. Therefore, in the absence of a substantive reason for delay in the treatment influencing the outcome variable, immediacy is paramount. Autocorrelation was not modeled in 83.8% of the studies. Of these, one study reported a statistically impossible autocorrelation value of 2. When not including autocorrelations for autocorrelated data, we are assuming the data are independent of each other and any parametric analysis that is employed would be used on data that violate the basic independence of observation assumption. This could lead to wildly inaccurate estimates. We coded the analysis as not being appropriate for the data if the data type did not meet the distributional assumptions of the type of analysis being conducted (65.8%). Again, this could lead to inaccurate estimates. Meta-analysis can be conducted when authors provide a reliable design-comparable effect size estimate or report the complete dataset which is common practice in SCEDs using a data plot. Only one study (0.9%) included autocorrelation and corrected for small sample size in their computations by reporting a design-comparable effect size, i.e., Hedges’ g [ 10 , 11 ]. 47.9% of the studies did not report raw data to be considered for future meta-analysis. Although several studies included more than one participant, only 15.4% computed and reported intraclass correlation. Intraclass correlation is necessary to be computed because it is the correlation among the scores within the individuals or the ratio of between cluster variance (i.e., the variability between people) to the total variance. That way we know how much of the variance in the outcome variable is due to differences between people and within people. This is also necessary to compute the appropriate effect size.

It is highly concerning that only 4 of the 115 (3.48%) studies met the WWC evidence standards. While it has become the default that the presence or absence of phenomena be accompanied by a measure of its magnitude, it is still unfortunate that this essential practice is not being upheld universally. The most reported mean difference effect size is not scale free and therefore, is difficult to interpret and aggregate across studies in meta-analysis. Other effect sizes were Cohen’s d, rate ratio, incidence ratio, etc. which did not include autocorrelation or correction for small sample size in their computations. These are also not design-comparable because they are within-subject effect sizes that are not computed across participants. Regarding immediacy, there are models developed specifically to determine immediacy and its magnitude that can help strengthen the evidence of effective treatments [ 12 , 13 ]. It would behoove medical N-of-1 researchers to examine these methodologies.

Not including autocorrelation in the statistical model is problematic because we know that SCED data are autocorrelated and not modeling autocorrelation leads to erroneous estimates of effect and inflated Type-I error rates [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Estimating autocorrelations with sufficient accuracy for shorter time-series is still in its fledgling stage, but it certainly cannot be ignored. We should also remember that most SCEDs have shorter time-series and/or fewer individuals which implies that violation of distributional assumptions becomes more serious, and results are more erroneous when these are ignored. This drawback is exacerbated by ignoring autocorrelations. Reporting intraclass correlation is important for understanding how similar the subjects were to each other and reporting adequate information such as the raw data or a design-comparable effect sizes is essential for scientific progress through meta-synthesis.

Given the findings, here are our recommendations for policymakers, gatekeepers of research standards, and editors of journals that are interested in ensuring the most robust level of conduct and analysis of N-of-1 trials.

Discuss the implications and set standards based on guidelines for best practices founded not just on research conduct in one discipline, but on interdisciplinary research conduct. Specifically, the social sciences and education/psychology research analyses of SCEDs are conducted based on the standards set forth by the WWC. The SPENT guidelines [ 5 ] focus on completeness and transparency of N-of-1 protocols. However, there is a need to derive the best practices based on both and combine the wealth of knowledge created in both fields.

WWC lays specific standards for meeting evidence standards and reporting treatment effect because the data are shorter time-series, are autocorrelated, and often have few participants. These must be strictly adhered to, especially in medical research which has high stakes impact for the subjects.

Use common terminology to facilitate interdisciplinary research. A classic example is identifying the type of SCED. This would allow us to set clear expectations for conduct of research following the highest standards.

Support more methodological contributions in medical journals particularly with respect to analyzing N-of-1 data.

Emphasize the imperative nature of reporting effect sizes and confidence/credible intervals when statistically analyzing data; in fact, make this a requirement.

Report enough information to facilitate meta-analysis, for that is the ultimate aim of most research. This can be either in the form of raw data or design-comparable effect sizes.

Encourage investigation of the impact of autocorrelations in estimating effect sizes. Require the inclusion of estimating and reporting autocorrelations.

Support more development of innovative and easy-to-use tools for analysis of N-of-1 analyses.

The limitations include including only English language articles, potentially excluding articles that might not have been part of the databases we searched in, human errors in coding (although we had 4 independent coders) and excluding N-of-1 studies that did not use our search terms in their title, abstract, or keywords.

In sum, N-of-1 studies in the medical field are not currently adhering to important standards that guard validity both in their conduct and in their analysis. Neither do they report adequate information to facilitate meta-analytic work. Editorial and research standards must require increased rigor in this experimental design which is still in its nascent stage.

Data availability

All data used in this article are made available through online supplemental Table 2 . This also contains all the variables used for coding and the references.

Gabler NB, Duan N, Vohra S, Kravitz RL. N-of-1 trials in the medical literature: a systematic review. Med Care. 2011;49:761–8.

McDonald S, McGree J, Nikles J. N-of-1 trials are valuable scientific methods for precision medicine. https://www.nof1sced.org/post/nov_20b .

Kratochwill TR, Hitchcock J, Horner RH, Levin JR, Odom SL, Rindskopf DM, et al. Single-case designs technical documentation. What works clearinghouse. 2010. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED510743.pdf .

Kratochwill TR, Hitchcock JH, Horner RH, Levin JR, Odom SL, Rindskopf DM, et al. Single-case intervention research design standards. Remedial Spec Educ. 2013;34:26–38.

Article Google Scholar

Porcino AJ, Shamseer L, Chan AW, Kravitz RL, Orkin A, Punja S, et al. SPIRIT extension and elaboration for n-of-1 trials: SPENT 2019 checklist. BMJ. 2020;368:m122.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

World Health Organization. ICD-10 International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: Tenth revision, 2nd ed. WHO; 2004. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42980 .

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatry Association; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Hedges LV, Pustejovsky JE, Shadish WR. A standardized mean difference effect size for multiple baseline designs across individuals. Res Synth Methods. 2013;4:324–41.

Hedges LV, Pustejovsky JE, Shadish WR. A standardized mean difference effect size for single case designs. Res Synth Methods. 2012;3:224–39.

Natesan P, Hedges LV. Bayesian unknown change-point models to investigate immediacy in single case designs. Psychol Methods. 2017;22:743.

Natesan Batley P, Minka T, Hedges LV. Investigating immediacy in multiple-phase-change single-case experimental designs using a Bayesian unknown change-points model. Behav Res Methods. 2020;52:1714–28.

Huitema BE. Autocorrelation in applied behavior analysis: a myth. Behavioral assessment.1985; 7:107–118.

Huitema BE. Autocorrelation in applied behavior analysis: a myth. Behav Assess. 1985;7:107–18.

Google Scholar

Huitema BE, McKean JW. Design specification issues in time-series intervention models. Educ Psychol Meas. 2000;60:38–58.

Huitema BE, McKean JW. Irrelevant autocorrelation in least-squares intervention models. Psychol Methods. 1998;3:104.

Huitema BE, McKean JW. A simple and powerful test for autocorrelated errors in OLS intervention models. Psychol Rep. 2000;87:3–20.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Huitema BE, McKean JW, McKnight S. Autocorrelation effects on least-squares intervention analysis of short time series. Educ Psychol Meas. 1999;59:767–86.

Download references

This work was funded by the grant from the Institute of Education Sciences R305D220052 to the first author of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, USA

Prathiba Natesan Batley, Brandy Brewer & Stephanie Chin

Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, 47907, USA

Erica B. McClure

University of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA

Ateka A. Contractor

Batley Consulting LLC, Louisville, KY, USA

Nicholas John Batley

Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA

Larry Vernon Hedges

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

PNB conceptualized the study. EM, BB, SC, and PNB conducted the literature search, coded, and conducted the analyses. PNB, AAC, NJB, and LVH co-wrote the manuscript. EM, BB, and SC assisted with editing and formatting.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Prathiba Natesan Batley .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary table 1, supplementary table 2, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Natesan Batley, P., McClure, E.B., Brewer, B. et al. Evidence and reporting standards in N-of-1 medical studies: a systematic review. Transl Psychiatry 13 , 263 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-023-02562-8

Download citation

Received : 06 October 2022

Revised : 28 June 2023

Accepted : 10 July 2023

Published : 18 July 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-023-02562-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

International Collaborative Network for N-of-1 Trials and Single-Case Designs

Advancing Individualised Science

The International Collaborative Network for N-of-1 Trials and Single-Case Designs (ICN) is a global network of researchers, academics, clinicians, and consumers from around the world who are interested in N-of-1 trials and single-case designs to understand and improve outcomes for individuals and groups.

Get involved! Join the ICN to stay up-to-date about what is happening in the field including methodological developments, collaborative opportunities, training initiatives and more.

Join the ICN

Last updated 1st December 2022

The ICN's vision is a world where personalised clinical studies (for both single and groups of individuals) are an integral part of clinical practice and health research. Read more about the ICN mission and objectives here . To find out more about the strategic priorities of the ICN please click here to read the ICN position paper.

The ICN aims to encourage discussion and collaboration amongst members through the content and features on this website. Members are encouraged to write Blogs and use the Discussion Forum to share new ideas, update others about current projects and events, discuss key research papers and ask questions.

- Mar 1, 2023

N-of-1 trials and single-case experimental designs in physiotherapy for musculoskeletal conditions

- Jun 30, 2022

Single-Case Studies as a Hot Topic in Pain Research: A Conference Review

- Aug 22, 2021

Brave New World of Health Care Consumerism, N-of-1, and Character of Health Type

- Jul 1, 2021

Implementing Single-Case Designs in Complementary and Alternative Medicine Trials

- May 31, 2021

Who Will Benefit from Which Diet: Can N-of-1 Studies Fill a Gap in the Care of Adult PKU?

- Mar 30, 2021

Will the Real Mr. Average Please Stand Up?

- Nov 30, 2020

N-of-1 Trials are Valuable Scientific Methods for Personalised Medicine

- Oct 31, 2020

Creating Evidence from Real World Patient Digital Data

- Jun 30, 2020

N-of-1 Trials in Practice: A Training Program for Complementary Medicine Practitioners

- May 31, 2020

Progress Towards Priorities for the International Collaborative Network for N-of-1 Trials and SCDs

- Jan 30, 2020

Visualization of Individual Data: A Powerful Tool in Personalized Medicine

- Sep 30, 2019

Going Paperless: How Digital Technology Can Shape the Field of N-of-1 Trials

- Aug 30, 2019

N-of-1 Trials in CAM: The New Frontier for Generating Practice-Based Evidence?

- May 31, 2019

The Rare Disease Registry and Analytics Platform: Paving the way forward for N-of-1 trials

- Apr 30, 2019

Is There a Role for N-of-1 Trials in Nutrition Research?

- Mar 31, 2019

Evaluation of a Physical Activity Intervention for Individuals with Whiplash Associated Disorders

- Feb 28, 2019

Using N-of-1 Trials to Identify Responders to Melatonin for Sleep Disturbance in Parkinson's Disease

- Jan 31, 2019

Effect of mexiletine on muscle stiffness in nondystrophic myotonia: aggregated N-of-1 trials

- Dec 31, 2018

10 key take-home messages from an expert workshop on single-case methodology

- Nov 30, 2018

Personalised treatments for acute whiplash injuries: A pilot study

ICN Blogs & Interviews with Thought Leaders

An Interview with A/Professor Rumen Manolov, Thought Leader in the Field of Single-Case Designs

An Interview with Professor Patrick Onghena, Thought Leader in the Field of Single-Case Designs

An Interview with Professor Johan Vlaeyen, Thought Leader in the Field of Single-Case Designs

An Interview with Professor Nicholas Schork, Thought Leader in the Field of Single-Case Designs

Case studies, single-subject research, and N of 1 randomized trials: comparisons and contrasts

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Health Care & Epidemiology, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

- PMID: 10088595

- DOI: 10.1097/00002060-199903000-00022

Case studies, single-subject research designs, and N of 1 randomized clinical trials are methods of scientific inquiry applied to an individual or small group of individuals. A case study is a form of descriptive research that seeks to identify explanatory patterns for phenomena and generates hypotheses for future research. Single-subject research designs provide a quasi-experimental approach to investigating causal relationships between independent and dependent variables. They are characterized by repeated measures of an observable and clinically relevant target behavior throughout at least one pretreatment (baseline) and intervention phase. The N of 1 clinical trial is similar to the single-subject research design through its use of repeated measures over time but also borrows principles from the conduct of large, randomized controlled trials. Typically, the N of 1 trial compares a therapeutic procedure with placebo or compares two treatments by administering the two conditions in a predetermined random order. Neither the subject nor the clinician is aware of the treatment condition in any given period of time. All three approaches are relatively easy to integrate into clinical practice and are useful for documenting individualized outcomes and providing evidence in support of rehabilitation interventions.

Publication types

- Double-Blind Method

- Effect Modifier, Epidemiologic

- Guidelines as Topic

- Medical Records*

- Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic / methods*

- Rehabilitation

- Reproducibility of Results

- Research Design / standards*

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

- Health and social care

- Public health

- Health improvement

N-of-1 study: comparative studies

How to use an N-of-1 study to evaluate your digital health product.

This page is part of a collection of guidance on evaluating digital health products .

N-of-1 studies focus on observing changes in individuals (single cases) over time, in comparison to a group-based design in which outcomes are combined for many participants. N-of-1 design (also known as a single-case design study) is used to understand within-person processes, such as changes in an individual’s engagement with your digital product over a period of time.

What to use it for

Similar to group-based designs, an N-of-1 study can be:

- observational (you record what you see)

- experimental (you compare periods when a digital product or features are provided with periods when they are not provided)

This means it can be used during development (formative or iterative evaluation) to find out how to improve your product. It helps you to explore its more nuanced effects and determine, for example, what factors predict higher usage.

An N-of-1 study can also be used to evaluate the effects of your digital product by providing detailed data on how the effect varies for a single person. Because of this, it can be used to inform the design of a comparative study (see Choose evaluation methods: evaluating digital health products ).

Benefits of N-of-1 studies include:

- they can provide more granular data on changes in an outcome than you would get from combining outcome data across participants

- they can identify individuals a product works for and does not work for

- they generally require fewer participants in comparison to more traditional group-based studies

- in an experimental evaluation, each participant acts as their own control, meaning the design is more sensitive to differences in the effects of the intervention

Drawbacks of N-of-1 studies include:

- they often involve intense data collection that might be a burden for some participants

- you might need expert statistical skills to analyse the data

- there is a risk of missing data because of the repetitive nature of collecting the data – this can make the analysis more complex

How to carry out an N-of-1 study

The most rigorous of this type of study is an N-of-1 trial. In a traditional randomised controlled trial ( RCT ), groups of participants are randomly allocated to an intervention or a control condition. In an N-of-1 trial, individuals are assigned to different options in a randomly-determined order, so they are exposed to the intervention and control on different days of the trial period (called multiple crossovers).

Because a participant experiences the intervention and the control over different times, some interventions are not appropriate for assessing in an N-of-1 trial. For example, if the:

- intervention takes more time than a typical treatment period to produce an effect (slow onset effect)

- intervention produces a change that remains for some time after the intervention stops (carry-over effect)

- health condition is progressing rapidly

This means N-of-1 trials are good for interventions that are reversible (where the effect wanes over a short time), but not appropriate for interventions which have a long-lasting effect.

Between the periods, you can introduce a washout period, in which, to allow the effects of the previous intervention to diminish, participants receive no intervention. This can help with some slow-onset and carry-over effects. Piloting your digital intervention can also help you to identify any slow-onset and carry-over effects, and how significant they might be.

The statistical power (see ‘Statistical power’ in Design your evaluation: evaluating digital health products ) of N-of-1 studies depends on the number of observations rather than the number of participants. N-of-1 designs typically use ecological momentary assessment, which involves frequent data collection at different intervention phases.

An N-of-1 study can include just one person, but typically a series of N-of-1 studies are undertaken. These can either be analysed as separate datasets, or in some cases combined statistically to provide an average effect between participants. If a large number of N-of-1 datasets are combined, then it is possible to identify participant characteristics that are associated with the intervention effect (for example, to identify who the intervention works for and who it does not work for).

The data from an N-of-1 study should be treated as a time series: repeated observations of a particular measurement collected over time. It’s important to note that individual responses tend to be more similar when assessments are carried out close together in time (autocorrelation). For example, when responding to a questionnaire about how you are feeling, your responses given yesterday and tomorrow will usually be more similar to each other than your reponses given a week ago or a week in the future.

You will need to analyse the data using models that account for autocorrelation, either as single cases or combined in a multilevel analysis.

Example: evaluating the effect of goal-setting and self-monitoring on increasing walking

See Sniehotta and others (2012): Testing self-regulation interventions to increase walking using factorial randomized N-of-1 trials .

Researchers wanted to investigate the effectiveness of 2 interventions on walking: goal-setting versus self-monitoring.

They used a factorial N-of-1 trial where they assessed how effective goal-setting and self-monitoring features are in increasing walking. This design has similar principles to group-based factorial RCTs . This was a series of 2 × 2 factorial N-of-1 studies where 10 participants were randomised to either a goal-setting condition or a control and also to either a self-monitoring condition or a control.

In the goal-setting condition, participants were prompted to set themselves a goal to achieve a specific number of steps. The goal-setting control included a goal to consume more fruit and vegetables on that day.

For the self-monitoring condition, participants were given 2 pedometers, one with a visible display and one with a sealed (blinded) display, to monitor their steps.

Participants received a text message prompt each morning, telling them which goal and pedometer they needed to use.

The researchers conducted 10 regression analyses, one per participant, to find out for whom goal-setting and self-monitoring were effective. They controlled for autocorrelation. The study did not have the statistical power to detect interaction effects. Read more about interaction effects in factorial RCTs .

Researchers found that most participants increased their number of steps in both the goal-setting and self-monitoring conditions compared to control days. However, individual analyses showed different effects of the interventions:

- 4 participants significantly increased walking – 2 on self-monitoring days and 2 on goal-setting days

- one participant showed a small decrease in their steps throughout the study

This study showed the variability of the effects of these 2 commonly-used ways to increase activity, suggesting that one size does not fit all.

More information and resources

Dallery and others (2013): Single-case experimental designs to evaluate novel technology-based health interventions . This article discusses how N-of-1 studies can be useful for assessing digital technology.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2014): Design and implementation of N-of-1 trials: a user’s guide . A comprehensive guide on how to conduct N-of-1 studies.

Kwasnicka and Naughton (2020): N-of-1 methods: A practical guide to exploring trajectories of behaviour change and designing precision behaviour change interventions . This paper provides a guide to analysing N-of-1 data, including how to account for autocorrelations in N-of-1 studies.

Kwasnicka and others (2018): Challenges and solutions for N-of-1 design studies in health psychology . This article outlines the challenges of doing N-of-1 studies and gives solutions for overcoming them.

Examples of N-of-1 studies in digital health

Odineal and others (2020): Effect of mobile device-assisted N-of-1 trial participation on analgesic prescribing for chronic pain: randomized controlled trial . The team conducted an N-of-1 trial and used an app to facilitate the running of the study.

Lee and others (2020): “Asking too much?”: A randomised N-of-1 trial exploring patient preferences and measurement reactivity to frequent use of remote multidimensional pain assessments in children and young people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis . An N-of-1 study to explore the most acceptable way to measure pain levels in children and young people.

Related content

Is this page useful.

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. Please fill in this survey .

Nitrate contamination in groundwater and its health risk assessment: a case study of Quanzhou, a typical coastal city in Southeast China

- Original Article

- Published: 13 May 2024

- Volume 83 , article number 331 , ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Zhenghong Li 1 , 2 ,

- Jianfeng Li 1 , 2 ,

- Jin’ou Huang 3 &

- Yasong Li 1 , 2

Nitrate contamination has become an ecological and health issue in Quanzhou, a typical coastal city in Southeast China. Hydrogeological surveys reveal that NO 3 − is a major factor influencing the groundwater quality in Quanzhou City, Fujian Province, China. To protect public health, this study explored the geographical spatial distribution, contamination level, contamination sources, and noncancer risks of nitrates in the plain area of Quanzhou. Key findings are as follows: (1) The groundwater in Quanzhou’s plain area exhibits a high detection rate and over-limit ratio of NO 3 − –N of 99.3% and 57.86%, respectively. This result suggests that the groundwater in the area has been extensively contaminated by nitrates, with relatively severe nitrate contamination occurring in the Quanzhou Taiwanese Investment Zone, Jinjiang City, and Shishi City; (2) NO 3 − has become a major anion in groundwater in Quanzhou’s plain area, leading to significant geochemical changes in some groundwater. 26.4% of the groundwater samples exhibited a hydrochemical type of nitric acid (also referred to as NO 3 − type water), with X(NO 3 − ) ≥ 25%; (3) The primary nitrate contamination in groundwater in Quanzhou originates from the infiltration of domestic and industrial wastewater or landfill leachate; (4) 42.86%, 43.57%, and 67.14% of the samples posed health risks to adult males, adult females, and children, respectively when they were subjected to the prolonged exposure in a high-concentration nitrate environment. Additionally, the noncancer risks of nitrates principally stem from oral exposure for drinking water.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Data availability

The data used to support the fndings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abascal E, Gomez-Coma L, Ortiz I, Ortiz A (2022) Global diagnosis of nitrate pollution in groundwater and review of removal technologies. Sci Total Environ 810:152233

Article CAS Google Scholar

Abu-alnaeem M, Yusoff I, Ng T, Alias Y, Raksmey M (2018) Assessment of groundwater salinity and quality in Gaza coastal aquifer, Gaza Strip, Palestine: an integrated statistical, geostatistical and hydrogeochemical approaches study. Sci Total Environ 615:972–989

Bahadoran Z, Mirmiran P, Ghasemi A, Kabir A, Azizi F, Hadaegh F (2015) Is dietary nitrate/nitrite exposure a risk factor for development of thyroid abnormality? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nitric Oxide 47:65–76

Banyikwa A (2023) Geochemistry and sources of fluoride and nitrate contamination of groundwater in six districts of the Dodoma region in Tanzania. Scient African 21:e01783

Bellettini A, Viero A, Neto A (2019) Hydrochemical and contamination evolution of Rio Bonito aquifer in the carboniferous region, Paraná Basin, Brazil. Environ Earth Sci 78:1–15

Google Scholar

Bian JM, Zhang ZZ, Han Y (2015) Spatial variability and health risk assessment of nitrogen pollution in groundwater in Songnen Plain. J Chongqing Univer 38(4):104–111 ( (in Chinese with English abstract) )

CAS Google Scholar

Bouderbala A (2019) The impact of climate change on groundwater resources in coastal aquifers: case of the alluvial aquifer of Mitidja in Algeria. Environ Earth Sci 78:1–13

Article Google Scholar

Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME) (2014) Canadian environmental quality guidelines

Fujian Provincial Sports Bureau, China (2022) The fifth National Physical Fitness Monitoring Bulletin of Fujian Province. Fujian Province. (in Chinese)

Gallagher T, Gergel S (2017) Landscape indicators of groundwater nitrate concentrations: an approach for trans-border aquifer monitoring. Ecosphere 8(12):e02047. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2047

Gutierrez M, Biagioni R, Alarcon-Herrera M, Rivas-Lucero B (2018) An overview of nitrate sources and operating processes in arid and semiarid aquifer systems. Sci Total Environ 624:1513–1522

Heaton T, Stuart M, Sapiano M, Micallef Sultana M (2012) An isotope study of the sources of nitrate in Malta’s groundwater. J Hydrol 414–415:244–254

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) (2022) Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs 1:132

Jiang WJ, Wang GC, Sheng YZ, Zhao D, Liu CL, Guo YH (2016) Enrichment and sources of nitrogen in groundwater in the Turpan-Hami area, Northwestern China. Expo Health 8:389–400

Kong XK, Zhang ZX, Wang P, Wang YY, Zhang ZJ, Han ZT, Ma LS (2022) Transformation of ammonium nitrogen and response characteristics of nitrifying functional genes in tannery sludge contaminated soil. J Groundwater Sci Eng 10(3):223–232

Lahjouj A, Hmaidi A, Bouhafa K (2020) Spatial and statistical assessment of nitrate contamination in groundwater: Case of Sais Basin, Morocco. J Groundwater Sci Eng 8(2):143–157

Li ZH, Zhang YL, Hu B, Wang LJ, Zhu YC, Li JF (2018) Driving action of human activities on NO 3 – -N pollution in confined groundwater of Togtoh County. Inner Mongolia Acta Geoscientica Sinica 39(3):358–364 ( (in Chinese with English abstract) )

Li Y, Kang FX, Zou AD (2019) Isotope analysis of nitrate pollution sources in groundwater of Dong’e geohydrological unit. J Groundwater Sci Eng 7(2):145–154

Li ZH, Li YS, Hao QC, Li JF, Zhu YC (2021) Characteristics, genesis and treatment measures of NO 3 type groundwater in Xiamen, Fujian Province. Geology in China 48(5): 1441–1452. 6 (in Chinese with English abstract)

Menció A, Mas-Pla J, Otero N, Regàs O, Boy-Roura M, Puig R, Bach J, Domènech C, Zamorano M, Brusi D, Folch A (2016) Nitrate pollution in groundwater; all right…, but nothing else? Sci Total Environ 539:241–251

Ministry of Ecology and Environmental PRC (2013) Chinese population Exposure Parameters Manual: Volume for children. Beijing, China Environmental Press (in Chinese).

Ministry of Ecology and Environmental PRC (2013) Chinese population Exposure Parameters Manual: Adult volume. Beijing, China Environmental Press ( in Chinese )

Monteny G (2001) The EU nitrates directive: a european approach to combat water pollution from agriculture. In Optimizing Nitrogen Management in Food and Energy Production and Environmental Pro tection: Proceedings of the 2nd International Nitrogen Conference on Science and Policy. The Scientific World 1(S2) 927–935

Musaed H, Al-Bassam A, Zaidi F, Alfaifi H, Ibrahim E (2020) Hydrochemical assessment of groundwater in mesozoic sedimentary aquifers in an arid region: a case study from Wadi Nisah in Central Saudi Arabia. Environ Earth Sci 79:1–12

National Health Commission, PRC, Standardization Administration, PRC (2022) Standards for dringing water quality. Beijing (in Chinese)

Panneerselvam B, Muniraj K, Duraisamy K, Pande C, Karuppannan S, Thomas M (2023) An integrated approach to explore the suitability of nitrate-contaminated groundwater for drinking purposes in a semiarid region of India. Environ Geochem Health 45:647–663

Papazotos P, Koumantakis I, Vasileiou E (2019) Hydrogeochemical assessment and suitability of groundwater in a typical Mediterranean coastal area: A case study of the Marathon basin, NE Attica, Greece. HydroResearch 2:49–59

Peixoto F, Cavalcante I, Gomes D (2020) Influence of land use and sanitation issues on water quality of an urban aquifer. Water Resour Manage 34:653–674

Pouye A, Cissé Faye S, Diédhiou M, Gaye C, Taylor R (2023) Nitrate contamination of urban groundwater and heavy rainfall: Observations from Dakar. Senegal Vadose Zone Jl 22:e20239

Rahman A, Mondal N, Tiwari K (2021) Anthropogenic nitrate in groundwater and its health risks in the view of background concentration in a semiarid area of Rajasthan. India. Scient Rep 11(1):1–13

Rezende D, Nishi L, Coldebella P, Mantovani D, Soares P, Carlos Valim Junior N, Vieira A, Bergamasco R (2019) Evaluation of the groundwater quality and hydrogeochemistry characterization using multivariate statistics methods: case study of a hydrographic basin in Brazil. Desalin Water Treat 161:203–215

Romanelli A, Soto D, Matiatos I, Martínez D, Esquius S (2020) A biological and nitrate isotopic assessment framework to understand eutrophication in aquatic ecosystems. Sci Total Environ 715:136909

Sheng DR, Wen XH, Feng Q, Wu J, Si JH, Wu M (2019) Groundwater nitrate pollution and human health risk assessment in the Zhangye Basin, Gansu. China J Desert Res 39(5):37–44 ( (in Chinese with English abstract) )

Stuart M, Gooddy D, Bloomfield J, Williams A (2011) A review of the impact of climate change on future nitrate concentrations in groundwater of the UK. Sci Total Environ 409(15):2859–2873

Sun XB, Guo CL, Zhang J, Sun JQ, Cui J, Liu MH (2023) Spatial-temporal difference between nitrate in groundwater and nitrogen in soil based on geostatistical analysis. J Groundwater Sci Eng 11:37–46

Tokazhanov G, Ramazanova E, Hamid S, Bae S, Lee W (2020) Advances in the catalytic reduction of nitrate by metallic catalysts for high efficiency and N 2 selectivity: A review. Chem Eng J 384:123252

United States Environment Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) (2022) Integrated risk information systerm

United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) (2017) Drinking water contaminants–standards and regulations

Verma A, Sharma A, Kumar R, Sharma P (2023) Nitrate contamination in groundwater and associated health risk assessment for Indo-Gangetic Plain. India Groundwater for Sustain Dev 23:100978

Vilmin L, Mogollon J, Beusen A, Bouwman A (2018) Forms and subannual variability of nitrogen and phosphorus loading to global river networks over the 20th century. Global Planet Change 163:67–85

Ward M, Jones R, Brender J, De Kok T, Weyer P, Nolan B, Villanueva C, Van Breda S (2018) Drinking water nitrate and human health: an updated review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(7):1557

WHO (2017) Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality: Fourth Edition Incorporating the First Addendum, fourthed. World Health Organization, Geneva

Yang M, Fei YH, Ju YW, Ma Z, Li HQ (2012) Health risk assessment of groundwater Pollution- a case study of typical city in North China Plain. J Earth Sci 23(3):335–348

Zakaria N, Gibrilla A, Owusu-Nimo O, Adomako D, Anornu G, Fianko J, Gyamfi C (2023) Quantifcation of nitrate contamination sources in groundwater from the Anayari catchment using major ions, stable isotopes, and Bayesian mixing model. Ghana Environ Earth Sci 82:381

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the China Geological Survey project (Nos. DD20190303, DD20221773, DD20230459) and Zhejiang Provincial Geological Special Fund Project (No. 2023010)

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Fujian Provincial Key Laboratory of Water Cycling and Eco-Geological Processes, Xiamen, 361000, China

Zhenghong Li, Jianfeng Li & Yasong Li

Institute of Hydrogeology and Environmental Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Shijiazhuang, 050061, China

Zhejiang Institute of Geosciences, Hangzhou, 310007, China

Jin’ou Huang

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Writing-original draft, Zhenghong Li; Reviewing and editing, Jianfeng Li, Yasong Li; Methodology, Jianfeng Li, Yasong Li, Zhenghong Li, Jin’ou Huang; Investigation, data collection, Zhenghong Li, Jianfeng Li; Figures preparation, Zhenghong Li, Jin’ou Huang; All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jianfeng Li .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Li, Z., Li, J., Huang, J. et al. Nitrate contamination in groundwater and its health risk assessment: a case study of Quanzhou, a typical coastal city in Southeast China. Environ Earth Sci 83 , 331 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-024-11608-z

Download citation

Received : 21 December 2023

Accepted : 18 April 2024

Published : 13 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-024-11608-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Spatial distribution

- NO 3 − type water

- Hydrochemistry

- Risk assessment

- Southeast coast

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 10 May 2024

Importance of multimodal resident education curriculum for general surgeons: perspectives of trainers and trainees

- Jeeyeon Lee 1 na1 ,

- Hyung Jun Kwon 1 na1 ,

- Soo Yeon Park 1 &

- Jin Hyang Jung 1

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 518 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

14 Accesses

Metrics details

Satisfaction should be prioritized to maximize the value of education for trainees. This study was conducted with professors, fellows, and surgical residents in the Department of general surgery (GS) to evaluate the importance of various educational modules to surgical residents.

A questionnaire was administered to professors ( n = 28), fellows ( n = 8), and surgical residents ( n = 14), and the responses of the three groups were compared. Four different categories of educational curricula were considered: instructor-led training, clinical education, self-paced learning, and hands-on training.

The majority of surgeons regarded attending scrubs as the most important educational module in the training of surgical residents. However, while professors identified assisting operators by participating in surgery as the most important, residents assessed the laparoscopic training module with animal models as the most beneficial.

Conclusions

The best educational training course for surgical residents was hands-on training, which would provide them with several opportunities to operate and perform surgical procedures themselves.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Continuous, lifelong medical education should be provided because it is essential to training qualified specialists in every medical field [ 1 ]. Educational periods may be categorized as medical college, postgraduate, and specialist education. The residency training program is the most important part of postgraduate education. However, departments of general surgery (GS) in the United States and South Korea are seeing decreased demand for surgical residencies [ 2 , 3 , 4 ].

The decreasing demand for residencies in GS is critical because it results in a lack of specialists. The reasons for this demand reduction vary and include the fatigue accumulated from emergency surgeries, the deterioration of their quality of life, and the frequent stressful situations caused by handling vital organs [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. Nevertheless, many physicians continue to choose surgical residency and might feel enthusiastic when they succeed in performing surgery, thus saving patients’ lives and improving patients’ odds of survival. Although a majority of surgical applicants apply with this intent, they experience frustration and often regret their decision when faced with the harsh reality of the field. In light of these problems, surgical residency training should pay attention to the mental and physical well-being of residents. In particular, unlike the trainers’ generation, residents of the twenty-first century prioritize work-life balance, technological proficiency, adaptability to pandemic situations, diversity, and inclusion [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ]. These factors have gained even greater emphasis following the coronavirus pandemic. Given that residents in Korea tend to avoid challenging but essential medical care, motivation becomes even more critical for those applying to GS. Educational programs that fail to consider these specific characteristics may lead to decreased achievement and efficiency.

Experts agree that instructors must consider trainees’ satisfaction to maximize educational impact [ 12 , 13 ]. Each qualified specialist’s training involves numerous educational training modules, which should be accessible and tailored to the demands of surgery. Instructors should determine how to increase educational impact by verifying the degree of satisfaction of surgical residents and evaluating the efficacy of the educational curriculum. Educational programs are generally divided into instructor-led training (ILT) and self-paced learning (SPL), and the program should be structured to balance these two areas equally [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ]. Moreover, in the education of doctors, each resident must receive not only theoretical education but also more detailed programs related to clinical and technical skills.

In this study, by evaluating the responses of professors, fellows, and surgical residents in a department of GS regarding trainee satisfaction and the importance of educational training modules, we identified the most appropriate educational curriculum for residents to establish better training courses toward cultivating specialists with higher qualifications.

The educational curricula for surgical residents were organized by the Education Committee of the department of surgery at Kyungpook National University Hospital, Daegu, Republic of Korea. The categories of educational curricula were classified into ILT, clinical education, SPL, hands-on training, and detailed training courses (Table 1 , Supplementary Fig. 1 ). ILT is defined as a training and learning program provided by instructors or teachers, whereas SPL is a student-driven learning design [ 18 , 19 , 20 ].

The importance of different categories of resident education was assessed on the basis of a cross-sectional questionnaire proffered via e-mails or text messages. Professors, fellows, and surgical residents responded to the survey. Academic faculty and clinical specialists comprised the group of professors. Fellows were defined as specialists who had completed their residency within the immediately preceding two years. The training system for medical residents in Korea consists of a three-year format, and accordingly, surgical residents consisted of first-year, second-year, and third-year residents following the curriculum of the Korean Surgical Society. All the professors and fellows, who have successfully completed their residency and obtained specialist qualifications, were regarded as educators. And only residents in their first to third years of training were considered as trainees.

The questionnaire comprised nine items, including the level of the surgeons; their self-estimated daily working hours; and the time they estimated to have devoted to the education of residents in a week, excluding routine jobs (Supplementary Table 1 ). The top three important education curricula among the 15 training courses constituting the educational curricula were further classified into the four categories.

Each complete response collected from professors, fellows, and residents was analyzed and presented in the form of bar graphs for convenient comparison.

Sociodemographic characteristics

In total, 50 surgeons responded to the questionnaires. Six of the respondents repeated their submissions because of incomplete forms. The mean ages of the groups of professors ( n = 28), fellows ( n = 8), and residents ( n = 14) were 47.3 years (SD, ± 15.1), 33.3 years (SD, ± 2.3), and 31.0 years (SD, ± 3.3), respectively.

Professors specialized in breast/thyroid (n = 7, 25.0%), colorectal ( n = 6, 21.4%), upper gastrointestinal ( n = 5, 17.9%), vascular ( n = 4, 14.3%), hepato-bilio-pancreatic ( n = 3, 10.7%), pediatric ( n = 1, 3.6%), trauma (n = 1, 3.6%), and critical care ( n = 1, 3.6%) surgeries. Fellows majored in vascular ( n = 3, 37.5%), colorectal ( n = 2, 25.0%), upper gastrointestinal ( n = 1, 12.5%), breast/thyroid ( n = 1, 12.5%), and critical care ( n = 1, 12.5%) surgeries. Fourteen residents from the first year ( n = 2, 14.3%), second year ( n = 4, 28.6%), and third year ( n = 8, 57.1%) participated (Supplementary Table 3 ).

Self-estimated daily working time and time devoted to the education of residents in a week.

Professors responded that they worked 8 h ( n = 8, 28.6%), 10 h ( n = 13, 46.4%), and more than 12 h ( n = 7, 25.0%) per day. However, a majority of fellows ( n = 6, 75.0%) and residents ( n = 12, 85.7%) responded that they worked for more than 12 h per day. Professors and residents spent approximately 2 h per week on the education of surgical residents, excluding routine jobs (Supplementary Table 2 ).

Most helpful educational category for the training of surgical residents.

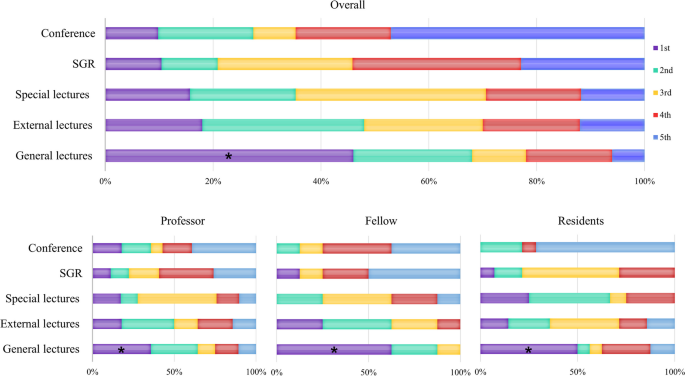

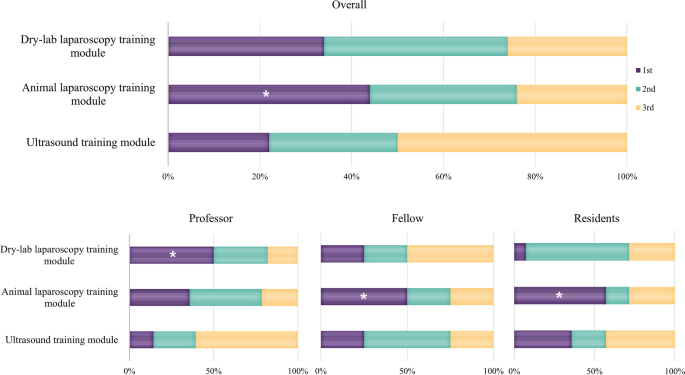

Of the four different educational categories, clinical education was regarded as the most helpful educational course for surgical residents by all groups. A marginal majority of professors (by a slight margin) regarded the ILT course as the most helpful to education. While fellows selected clinical education and SPL as the most and least helpful courses, surgical residents identified hands-on training and SPL as the most and least helpful courses, respectively (Fig. 1 ).

Importance ratings of four major educational categories for surgical residency training indicate that clinical education was considered the most important (*) curriculum overall. However, each group, including professors, fellows, and residents, judged different curricula to be the most important

Top three important educational curricula for surgical residents

The identification of the three most important curricula among the 15 training courses covered in the four categories was performed by way of a featured survey question. As shown in Table 2 , each group selected attending scrubs as the most important program among the three most important courses.

Importance of training courses in the ILT category for the training of surgical residents

All the surgeons selected general lectures by professors as the most important curriculum in the ILT category for the training of surgical residents. Notably, fellows and residents considered this curriculum the most important course to a greater extent than professors did. By contrast, professors and residents considered residents’ participation in regular in-hospital conferences the least important in resident training, whereas fellows considered the Surgical Grand Rounds as less important than other curricula (Fig. 2 ).

Importance ratings of instructor-led training (ILT) courses for surgical residency training indicate that general lectures were considered the most important (*) part of the curriculum overall. All groups consistently judged general lectures to be the most important educational program

Importance of the training course in the clinical education category of surgical residents’ training.

All groups responded that attending scrubs was the most important training method in clinical education. While the professor and resident groups ranked attending inpatient and outpatient clinics as second and third in importance, respectively, the fellow group rated the clinics with a similar degree of importance in clinical education (Fig. 3 ).

Importance ratings of courses within the clinical education category for surgical resident training indicate that attending scrubs are considered the most important, both overall and by each group

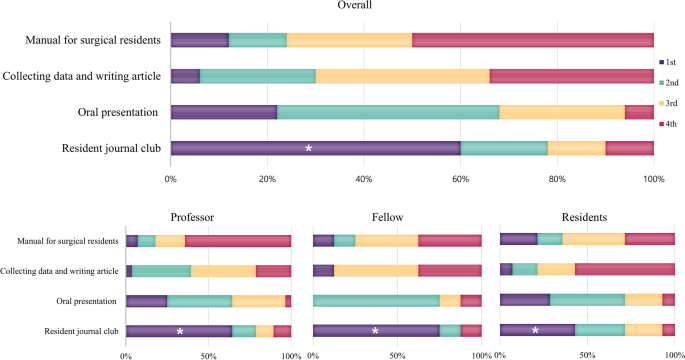

Importance of the training course in the SPL category for the training of surgical residents

All groups considered the regular journal club the most important training course in the SPL category. While the professor and fellow groups considered the manual for surgical residents less important than other curricula, residents regarded it as the third-most important course. Surgical residents considered collecting data and writing articles the least important (Fig. 4 ).

Importance ratings of self-paced learning (SPL) courses for surgical residency training indicate that resident journal club was considered the most important (*) part of the curriculum overall. And all groups consistently judged resident journal club to be the most important educational program

Importance of the training course in the hands-on training category for surgical residents’ training

In the hands-on category, the dry-lab laparoscopy training module within the hospital was deemed by professors as the most important training course for surgical residents, whereas the laparoscopic training module in the professional education center with animal models was perceived as most important by fellows and residents (Fig. 5 ).

Importance rating of courses within the hands-on training category for the training of surgical residents. While the professor group judged that dry lab laparoscopy training module was the most important (*), the fellow and resident groups judged the animal laparoscopy training module to be more important

This study revealed that trainers and trainees differ in their criteria for evaluating the importance of educational components, with surgical residents particularly interested in hands-on training. Halsted emphasized the significance of clinical and practical training in the education of American surgeons [ 21 ]. Similarly, current GS professors and residents place a high value on practical and technical education. However, stringent ethical standards present challenges for residents practicing directly on cadavers or patients [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. Consequently, professors typically offer thorough theoretical training before introducing practical skills to mitigate potential complications. The contemporary environment is causing divergent approaches between trainers and trainees. If an education system that closely simulates human conditions is developed, and a system where trainees can freely receive education within ethical boundaries is established, it could become the most efficient approach to education.

A series of educational courses must be provided to medical students, interns, residents, and fellows to ensure medical specialists’ optimal training. Although these training courses may be delivered at various levels depending on the knowledge and needs of trainees, instructors have predominantly solely developed the ILT curriculum. However, the actual effectiveness of training courses may differ from the instructors’ expectations; furthermore, considering the satisfaction of the trainees while planning the courses could improve the learning experience [ 12 , 13 , 27 ].

When designing curricula, it is crucial to consider that surgical residents apply for residencies because they are interested in surgery and are aspired to be surgeons. Some professors focus on teaching academic theory, while others contend that mastering the art of thesis writing is the most critical aspect of education. Nonetheless, the most basic desire of surgeons must be considered. In our current study, we found that the opinions of professors, fellows, and residents regarding the most important training courses for surgical residents were similar.

While the group of professors believed that watching many standardized surgeries is the most important training course needed by surgical residents to participate and assist in surgeries, residents considered having practical operating experience as the most important. Therefore, residents regarded the laparoscopic training module in the professional institute with animal models as the most important curriculum in the training of surgical residents. The responses from the group of fellows, who had completed their residency within the past two years, revealed a trend that intermediates between the views of professors and residents. Given their transitioning status from learners to educators, their opinions are considered very important. In fact, these opinions represented a compromise between the perspectives of professors and residents in their roles as educators.

Each of the different learning methodologies of ILT and SPL has advantages and disadvantages [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. ILT offers detailed materials and immediate feedback but is limited by structured schedules and instructor variability. SPL allows flexibility in timing and location with the use of open-source materials, enabling repeated review of content, though it lacks the immediate feedback of ILT and may require more time for comprehension. Ultimately, trainees benefit most from actively engaging with the educational material and their learning process.

Although this study focused on resident education, only 14 residents were actually included which is a limitation of this study. However, unfortunately, this is the real-world situation in South Korea. Many doctors are avoiding essential medical services, such as internal medicine, GS, obstetrics and gynecology, and pediatrics. Instead, a majority prefer departments like plastic surgery, ophthalmology, and dermatology, which focus on cosmetic procedures or enhancing the quality of life. This is the reason why, despite being a fairly large-scale national university hospital, the number of residents was small. This situation underlines the importance of further improving the quality of education.

The responses in this study can help standardize the appropriate educational programs for surgical residents in GS departments. Based on these research findings, the authors' institution has decided to enhance technical education with theoretical support. It is currently developing and implementing education on ultrasound and biopsy techniques, laparoscopic bowel anastomosis, and robotic surgery. We established close cooperation with other departments so that in addition to surgical skills training, we could directly experience and learn other departments' techniques (intubation, ventilator manipulation, CPR, and so on.). Various colleagues and companies are supporting this training, viewing it as an investment in the future generation of surgeons. As demonstrated in the authors' study, it is necessary to verify and evaluate the educational programs of each institution for their rationality and efficiency. This approach will contribute to the training of better surgeons by enabling residents to engage more actively in the curriculum.

The educational impact of training materials and methods can be maximized when surgical residents engage in the preferred training resources that provide them with satisfaction. Therefore, the best educational training course for surgical residents would include providing them with many opportunities to operate and perform surgical procedures themselves. Although written materials and theories remain important, the effect of education is enhanced when the surgical residents’ satisfaction is increased through the provision of practical learning opportunities.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, JHJ, upon reasonable request.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Optimizing Graduate Medical Trainee (Resident) Hours and Work Schedule to Improve Patient Safety. Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Edited by Ulmer C, Miller Wolman D, Johns MME. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2009.

Kling SM, Raman S, Taylor GA, Philp MM, Poggio JL, Dauer ED, Oresanya LB, Ross HM, Kuo LE. Trends in general surgery resident experience with colorectal surgery: an analysis of the accreditation council for graduate medical education case logs. J Surg Educ. 2022;79(3):632–42.

Article Google Scholar

Ahn JS, Cho S, Park WJ. Changes in the health indicators of hospital medical residents during the four-year training period in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2022;37(25):e202.

Are C, Stoddard H, Carpenter LA, O’Holleran B, Thompson JS. Trends in the match rate and composition of candidates matching into categorical general surgery residency positions in the United States. Am J Surg. 2017;213(1):187–94.

Tracy TF Jr. Surgical fatigue-what dreams may come: comment on “surgeon fatigue.” Arch Surg. 2012;147(5):435–6.

Kiernan M, Civetta J, Bartus C, Walsh S. 24 hours on-call and acute fatigue no longer worsen resident mood under the 80-hour work week regulations. Curr Surg. 2006;63(3):237–41.

McCormick F, Kadzielski J, Landrigan CP, Evans B, Herndon JH, Rubash HE. Surgeon fatigue: a prospective analysis of the incidence, risk, and intervals of predicted fatigue-related impairment in residents. Arch Surg. 2012;147(5):430–5.

Malangoni MA, Biester TW, Jones AT, Klingensmith ME, Lewis FR Jr. Operative experience of surgery residents: trends and challenges. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(6):783–8.

Jarman BT, Cogbill TH, Mathiason MA, O’Heron CT, Foley EF, Martin RF, Weigelt JA, Brasel KJ, Webb TP. Factors correlated with surgery resident choice to practice general surgery in a rural area. J Surg Educ. 2009;66(6):319–24.

Cyr-Taro AE, Kotwall CA, Menon RP, Hamann MS, Nakayama DK. Employment and satisfaction trends among general surgery residents from a community hospital. J Surg Educ. 2008;65(1):43–9.

Rasmussen JM, Najarian MM, Ties JS, Borgert AJ, Kallies KJ, Jarman BT. Career satisfaction, gender bias, and work-life balance: a contemporary assessment of general surgeons. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(1):119–25.

Hou J, He Y, Zhao X, Thai J, Fan M, Feng Y, Huang L. The effects of job satisfaction and psychological resilience on job performance among residents of the standardized residency training: a nationwide study in China. Psychol Health Med. 2020;25(9):1106–18.

Waltz LA, Muñoz L, Weber Johnson H, Rodriguez T. Exploring job satisfaction and workplace engagement in millennial nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28(3):673–81.

Chen BY, Kern DE, Kearns RM, Thomas PA, Hughes MT, Tackett S. From modules to MOOCs: application of the six-step approach to online curriculum development for medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94(5):678–85.

Vestergaard LD, Løfgren B, Jessen CL, Petersen CB, Wolff A, Nielsen HV, Krarup NH. A comparison of pediatric basic life support self-led and instructor-led training among nurses. Eur J Emerg Med. 2017;24(1):60–6.

Bylow H, Karlsson T, Claesson A, Lepp M, Lindqvist J, Herlitz J. Supplementary dataset to self-learning training compared with instructor-led training in basic life support. Data Brief. 2019;25:104064.

Bylow H, Karlsson T, Claesson A, Lepp M, Lindqvist J, Herlitz J. Self-learning training versus instructor-led training for basic life support: a cluster randomised trial. Resuscitation. 2019;139:122–32.

Hildebrandt GH, Belmont MA. Self-paced versus instructor-paced preclinical training in operative dentistry: a case study. J Dent Educ. 2018;82(11):1178–84.

Dhaliwal N, Simpson F, Kim-Sing A. Self-paced online learning modules for pharmacy practice educators: Development and preliminary evaluation. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2018;10(7):964–74.