Narrative therapy with an emotional approach for people with depression: Improved symptom and cognitive-emotional outcomes

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Counseling, Dankook University, Seoul, Korea.

- 2 Red Cross College of Nursing, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, Korea.

- 3 Department of Nursing, Daegu Health College, Daegu, Korea.

- 4 College of Nursing, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea.

- PMID: 25753316

- DOI: 10.1111/jpm.12200

Accessible summary: Narrative therapy is a useful approach in the treatment of depression that allows that person to 're-author' his/her life stories by focusing on positive interpretations, and such focus on positive emotions is a crucial component of treatment for depression. This paper evaluates narrative therapy with an emotional approach (NTEA) as a therapeutic modality that could be used by nurses for persons with depression. A nurse-administered NTEA intervention for people with depression appears effective in increasing cognitive-emotional outcomes, such as hope, positive emotions and decreasing symptoms of depression. Thus, NTEA can be a useful nursing intervention strategy for people with depression.

Abstract: Narrative therapy, which allows a person to 're-author' his/her life stories by focusing on positive interpretations, and emotion-focused therapy, which enables the person to realize his/her emotions, are useful approaches in the treatment of depression. Narrative therapy with an emotional approach (NTEA) aims to create new positive life narratives that focus on alternative stories instead of negative stories. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of the NTEA programme on people with depression utilizing a quasi-experimental design. A total of 50 patients (experimental 24, control 26) participated in the study. The experimental group completed eight sessions of the NTEA programme. The effects of the programme were measured using a self-awareness scale, the Nowotny Hope Scale, the Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale, and the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale. The two groups were homogeneous. There were significant differences in hope, positive and negative emotions, and depression between the experimental and control group. The results established that NTEA can be a useful nursing intervention strategy for people with depression by focusing on positive experiences and by helping depressed patients develop a positive identity through authoring affirmative life stories.

Keywords: depression; emotional approach; hope; narrative therapy; self-awareness.

© 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Cognition / physiology*

- Depression / therapy*

- Emotions / physiology*

- Middle Aged

- Narrative Therapy / methods*

- Outcome Assessment, Health Care*

Collection: Evidence for the effectiveness of narrative therapy

Evidence for the effectiveness of narrative therapy.

Francoise Karibwendea, Japhet Niyonsengaa, Serge Nyirinkwayac, Innocent Hitayezud, Celestin Sebuhoroa,Gitimbwa Simeon Sebatukuraa, Jeanne Marie Nteteaand Jean Mutabaruka

Background: Narrative Therapy is an efficacious treatment approach widely practiced for various psychological conditions. However, few studies have examined its effectiveness on resilience, a robust determinant of one’s mental health, and there has been no randomized controlled trial in sub-Saharan Africa.

Objective: This study sought to evaluate the efficacy of narrative therapy for the resilience oforphaned and abandoned children in Rwanda.

Method: This study was a‘parallel randomized controlled trial in which participants (n= 72) were recruited from SOS Children’s Village. Half of the participants (n= 36) were randomly allocated to the intervention group and the rest to the delayed narrative therapy group. For the intervention group, children attended ten sessions (55 min each) over 2.5 months. Data were collected using the Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM) and analyzed using mixed ANOVA within SPSS version 28.

Result: The results from ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of time and group for resilience total scores. Of interest, there was a significant time by group interaction effect for resilience. Pairwise comparison analyses within-group showed a significant increase in resilience in the intervention group, and the effect size was relatively large in this group.

Conclusion: Our findings highlight the notable efficacy of narrative therapy for children’s resilience in the intervention group. Therefore, health professionals and organizations working with orphaned and abandoned children will apply narrative therapy to strengthen their resilience and improve mental health.

Link: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/20008066.2022.2152111?needAccess=true&role=button

Carlos A. Chimpén-López, Meritxell Pascheco, Teresa Pretel-Luque, Rebeca Bastón and Daniel Chimpén-Sagrado

We present The Couple’s Tree of Life (CTOL) as a new col- lective narrative methodology to strengthen couple rela- tionships and prevent conflicts. The CTOL, based on the tree of life methodology (Ncube & Denborough, Tree of Life, mainstreaming psychosocial care and support: a man- ual for facilitators, REPSSI, 2007), aims to reinforce the identity and strengths of the couple. We explain the CTOL implementation process and illustrate it step by step with a group of 14 adult heterosexual Caucasian couples who belonged to Protestant churches in Madrid (Spain). As a way to assess its usefulness before applying the CTOL to other groups of couples, we conducted a pre-post evalua- tion using the Dyadic Adjustment Scale of Spanier(1976). We found an improvement in dyadic adjustment, quality, understanding of, and satisfaction with, the relationship. The results, though not generalizable at this stage, suggest that the CTOL could reinforce the couple’s identity while maintaining individual identities. We also discuss the pos- sible applications of couples therapy. Link

The purpose of this study was to explore women’s experiences in a narrative therapy-based group conducted to help participants re-author their stories. Seven women who were either patients or individuals enrolled in Transition Support for Employment at a psychiatric clinic participated in the meetings, one every fortnight. Each session explored a theme based on narrative therapy techniques such as externalization. The participants wrote their reflections during each session, and completed the Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition (BDI-II) during the initial and final sessions. An affinity diagram was developed to classify their written reflections into 22 lower categories (e.g., new understanding of self , forward-looking-understanding of life ) and 4 upper categories (“Insight,” “Sharing with others,” “Changes with understanding of lives,” “Higher motivation”). The relationship among five lower categories comprising “Insight” was explored, and it became apparent that clarification of participants’ own thoughts about social problems functioned as a mediator promoting the process. The largest portion of depressed feelings emerged during the initial session, and four participants had lower scores for BDI-II items such as self-criticism in the final session. The results suggest that the group’s purpose was realized. However, future studies should examine participants’ feelings more closely, especially during the initial session.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jpr.12326

Esther Oi Wah Chow, MSW, RSW, PhD, *, and Sai-Fu Fung, BSocSc, MA, PhD

*Address correspondence to: Esther O. W. Chow, MSW, MNTCW, PhD, RSW, Department of Social and Behavioural Sciences, City University of Hong Kong, Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon, Hong Kong. [email protected]

Background and Objectives: We developed a new group practice using strength- and meaning-based Narrative Therapy (NT) for older Chinese living in Hong Kong (HK), to enhance their life wisdom. This paper reports on the intervention and its short- and longer-term effectiveness. Research Design and Methods A randomized waitlist-controlled trial (RCT) was conducted. A total of 157 older adults were randomly recruited, of whom 75 were randomly assigned to the intervention group which received four two-hour bi-weekly NT sessions using the ‘Tree of Life’ (ToL) metaphor. The others were placed on a waitlist. Perceived wisdom was assessed using the Brief Self-Assessed Wisdom Scale (BSAWS). Assessment occurred at baseline (T0), end of treatment (T1), and four (T2) and eight months later (T3). Over-time effects of NT on wisdom scores were assessed using latent growth curve models with time-invariant covariates for impact. Results The intervention (NT) group showed significant, sustainable over-time within-group improvement in perceived wisdom. Moreover, compared with the control group, the NT group showed significant immediate improvements in perceived wisdom [F(2.726, p = 0.041)], which were maintained at all follow-up points. This effect remained after controlling for age, gender and educational level [TML(11) = 17.306, p = 0.098, RMSEA = 0.079, CFI = 0.960]. No adverse reaction was recorded. Discussion and Implications NT underpinned by a ToL methodology offers a new theory to understand, promote and appreciate perceived wisdom in older Chinese living in HK. It contributes to psychotherapy and professional social work practice for older Chinese.

Mustafa Kemal Yöntem, Ömer Özer, Yeliz Kan

The purpose of this study was to adapt the Tree of Life application, which was developed based on narrative approach and used for trauma interventions frequently, into career counseling and evaluate its effectiveness on secondary schoolers’ career decision-making self-efficacy. Within the scope of the study, the effectiveness of career counseling program based on narrative therapy was investigated. This study is a quasi-experimental research which was carried out in Turkey. In this research, a 2X2 quasi-experimental design with pre-test and post-test measurements was used. First, two groups were formed, one as experimental and one as a control group. The career story development program based on the narrative therapy which was developed by the researchers was applied on the participants in the experimental group. All of the participants in the study were seventh grade students in the secondary school and 14 years old. The experiment group had 13 participants (6 male, 7 female), and the control group consisted of 12 participants (5 male, 7 female). Demographic Form and Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy (CDMSES) Scale were used as the data collection tools. In order to examine the research questions, Mann Whitney U-test was conducted between the pre-test and post-test scores of the experimental and control groups. According to the findings, while there was no significant difference between the pre-test scores for all sub-dimensions and total scores of the experimental group and the control group (p>, 05), significant differences were observed in the post-test scores in favor of the experimental group (p <, 05).

Effat Ghavibazou, Simin Hosseinian and Abbas Abdollahi The current study was designed as quasi‐experimental with a pretest and post‐test evaluating the efficacy of narrative therapy on communication patterns for women experiencing low marital satisfaction. Thirty women experiencing low marital satisfaction were chosen using convenience sampling and were randomly assigned to an intervention and waiting list group. The intervention group was treated individually by narrative therapy in eight 45‐minute sessions. Results from repeated measurement ANOVA revealed significant differences between and within the groups and interaction between and within groups. Independent and paired t‐test results showed significant improvement in the intervention group in their marital satisfaction, male‐demand/female‐withdraw, and total demand/withdraw with maintenance at eight weeks follow‐up. Results included increased marital satisfaction, reduced male‐demand/female‐withdraw, and reduced total demand/withdraw. Thus, results show that narrative therapy is effective in increasing the marital satisfaction indicators of male‐demand/female‐withdraw, total demand/withdraw, and marital satisfaction. Link.

Esther Oi Wah Chow and Doris Yuen Hung Fok

Chow, E. O. W., & Fok, D. Y. H. (2020). Recipe of Life: A Relational Narrative Approach in Therapy With Persons Living With Chronic Pain. Research on Social Work Practice , 30 (3), 320-329.

This paper reports on the use of a culturally resonant adaptation to a narrative therapy methodology with older adults in Hong Kong diagnosed with chronic pain. The metaphor of ‘spiritual seasoning of life’ was applied throughout six group-based sessions that followed narrative therapy maps. Three themes illuminating significant life enhancements were generated from subsequent participant interviews: Rediscovery of Personal Capabilities, Validation of Preferred Identity and Fusion of Spiritual Seasoning of Life. The authors conclude that narrative therapy was shown to be an applicable and effective approach for people living with chronic pain.

De-Hui Ruth Zhou, Yu-Lung Marcus Chiu, Tak-Lam William Lo, Wai-Fan Alison Lo, Siu-Sing Wong, Chi Hoi Tom Leung, Chui-Kam Yu, Yuk Sing Geoffrey Chang & Kwok-Leung Luk

Journal of Mental Health, published online 15 Jul 2020

DOI: 10.1080/09638237.2020.1793123

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09638237.2020.1793123?journalCode=ijmh20

Situated in the Hong Kong context, this study utilises a methodology commonly associated with evidence-based practice to determine the helpfulness of collective narrative therapy groups for family members of someone living with schizophrenia. Until now, local programs to support family members have largely focussed on imparting skills and knowledge in caregiving. By way of an alternative, this article provides in replicable detail an account of steps taken to engage with creative metaphors and culturally-specific adaptations to narrative practice that centre the skills and knowledge family members already have. The authors conclude that the practice implications of their study point to the helpfulness of a narrative stance for eliciting stories about existing knowledge, the significance of attending to the uniqueness of culture and context, and the benefits of exploring preferred identity stories for family members with caring responsibilities.

Esther OW Chow

Chow, E. O. (2018). Narrative Group Intervention to reconstruct Meaning of Life among Stroke Survivors: A Randomized Clinical Trial Study. Neuropsychiatry , 08(04). doi:10.4172/neuropsychiatry.1000450

This study evaluated a narrative therapy meaning-making approach in relation to stroke survival. Following a series of conversations that focussed on deconstructing dominant life stories, externalising problem-saturated experience, and re-authoring identity, participants reported sustained improvements across a range of outcome measures. Stroke knowledge, mastery, self-esteem, hope, meaning in life, and life satisfaction were all demonstrated to have increased, whereas experiences of depression had decreased. The authors conclude that the indicated effects for self-concepts and improved meaning in life were sufficiently encouraging to suggest narrative therapy may be a viable option for facilitating stroke recovery.

Sarah Penwarden (2018) [ PhD thesis, University of Waikato ]

A key concern for therapists is how therapeutic change occurs, and what particular elements of therapy lead towards change. This project investigated how one approach in narrative therapy—rescued speech poetry—might enhance another therapeutic approach, re-membering conversations. Re-membering conversations nurture connections between a bereaved person and a loved person who has died. These conversations actively weave the stories of the lost loved one back into the life of the bereaved person, so that the loved one’s values and legacies continue to resound. This research explored how a literary approach—rescued speech poetry—potentially enhanced the nearness and contribution of a loved one, through capturing stories in a poetic form.

Marie-Nathalie Beaudoin, Meredith Moersch and Benjamin S. Evare

Journal of Systemic Therapies, Vol. 35, No. 3, 2016, pp. 42–59

This article examines the effectiveness of narrative therapy in boosting 8- to 10-year-old children’s social and emotional skills in school. Data were collected from 353 children over two years, and two research assistants independently coded 813 stories. Children’s personal accounts of their attempts at solving conflicts in their daily lives were collected before and after a series of narrative conversations, and compared to stories collected during the same time interval with a control group. The control data included a set of stories from waitlisted participants and those from students assigned to only a control group. The results of the study show that children receiving narrative therapy intervention showed a significant improvement in self-awareness, self-management, social awareness/empathy, and responsible decision making when compared to their own first stories and the stories from children in the control group. Improvement in relationship skills was present in both cohorts but was significant only for the second year. There was no significant gender difference. Narrative therapy practices such as externalizing and re-authoring can significantly contribute to the development of children’s social and emotional skills. Implications of these results are discussed for all forms of therapeutic interventions, regardless of theoretical orientation.

M. Seo, H. S. Kang, Y. J. Lee, S. M. Chae. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing Volume 22, Issue 6, pages 379–389, August 2015 : http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/resolve/doi?DOI=10.1111/jpm.12200

Narrative therapy, which allows a person to ‘re-author’ his/her life stories by focusing on positive interpretations, and emotion-focused therapy, which enables the person to realize his/her emotions, are useful approaches in the treatment of depression. Narrative therapy with an emotional approach (NTEA) aims to create new positive life narratives that focus on alternative stories instead of negative stories. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of the NTEA programme on people with depression utilizing a quasi-experimental design. A total of 50 patients (experimental 24, control 26) participated in the study. The experimental group completed eight sessions of the NTEA programme. The effects of the programme were measured using a self-awareness scale, the Nowotny Hope Scale, the Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale, and the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale. The two groups were homogeneous. There were significant differences in hope, positive and negative emotions, and depression between the experimental and control group. The results established that NTEA can be a useful nursing intervention strategy for people with depression by focusing on positive experiences and by helping depressed patients develop a positive identity through authoring affirmative life stories.

Erbes CR, Stillman JR, Wieling E, Bera W, Leskela J. J Trauma Stress. 2014 Dec;27(6):730-3. doi: 10.1002/jts.21966 . Epub 2014 Nov 10.

Narrative therapy is a postmodern, collaborative therapy approach based on the elaboration of personal narratives for lived experiences. Many aspects of narrative therapy suggest it may have great potential for helping people who are negatively affected by traumatic experiences, including those diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The potential notwithstanding, narrative therapy is relatively untested in any population, and has yet to receive empirical support for treatment among survivors of trauma. A pilot investigation of the use of narrative therapy with 14 veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD (11 treatment completers) is described. Participants completed structured diagnostic interviews and self-report assessments of symptoms prior to and following 11 to 12 sessions of narrative therapy. After treatment, 3 of 11 treatment completers no longer met criteria for PTSD and 7 of 11 had clinically significant decreases in PTSD symptoms as measured by the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale. Pre- to posttreatment effect sizes on outcomes ranged from 0.57 to 0.88. These preliminary results, in conjunction with low rates of treatment dropout (21.4%) and a high level of reported satisfaction with the treatment, suggest that further study of narrative therapy is warranted as a potential alternative to existing treatments for PTSD.

Majid Yoosefi Looyeh, Khosrow Kamali, Amin Ghasemi, Phuangphet Tonawanik The Arts in Psychotherapy, 2014, 41: 1: 16-20 DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2013.11.005

This study applied group narrative therapy to treating symptoms of social phobia among 10–11 year old boys. The treatment group received fourteen 90-min sessions of narrative therapy twice a week. Group narrative therapy was effective in reducing symptoms of social phobia at home and school as reported by parents and teachers.

Lopes, Rodrigo T.: Gonçalves, Miguel M.; Machado, Paulo; Sinai, Dana; Bento, Tiago & Salgado, João. Psychotherapy Research . Nov 2014, Vol. 24 Issue 6, p.662-674.

Systematic studies of the efficacy of Narrative Therapy (NT) for depression are sparse. Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of individual NT for moderate depression in adults compared to Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT). Method: Sixty-three depressed clients were assigned to either NT or CBT. The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and Outcome Questionnaire-45.2 (OQ-45.2) were used as outcome measures. Results: We found a significant symptomatic reduction in both treatments. Group differences favoring CBT were found on the BDI-II, but not on the OQ-45.2. Conclusions: Pre- to post-treatment effect sizes for completers in both groups were superior to benchmarked waiting-list control groups.

Lambie, I., Murray, C., Krynen, A., Price, M., & Johnston, E. (2013). The Evaluation of Undercover Anti-Bullying Teams. (Report). Auckland: Ministry of Education, Te Tāhuhu o Te Mātauranga.

https://www.dulwichcentre.com.au/UABT-Final-Report.pdf

Bullying is a significant societal problem in schools, having serious implications for both victims and perpetrators. While there have been many interventions developed to try and combat bullying in schools, many of these interventions are not formally evaluated. The current study evaluated an anti-bullying intervention that adopts a restorative approach that uses peer-led Undercover Anti-bullying Teams (UABTs) to combat bullying in the classroom. To evaluate this approach, the current study implemented the use of a pre- test/post-test experimental design in additional to qualitative interview data. The results suggest that following the intervention, there was a significant reduction in victimisation and a significant increase in students’ perceptions of personal support from other students in the class. Additionally, a number of themes emerged to suggest feelings of “inclusion” and “social support” were helpful to reduce distress for victims, and to help them feel more confident in the classroom. Additionally, the central elements of “autonomy” and “teamwork” that are inherent in the UABT intervention were helpful for team members in supporting the bullying victim and reducing bullying in the classroom.

Cashin, A, Browne, G, Bradbury, J & Mulder, AM 2013 Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Nursing, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 32-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12020

The aim of this pilot study was to be the first step toward empirically determining whether narrative therapy is effective in helping young people with autism who present with emotional and behavioral problems. Autism is increasingly being recognized in young people with average and above intelligence. Because of the nature of autism, these young people have difficulty navigating the challenges of school and adolescence. Narrative therapy can help them with their current difficulties and also help them develop skills to address future challenges. Narrative therapy involves working with a person to examine and edit the stories the person tells himself or herself about the world. It is designed to promote social adaptation while working on specific problems of living. This pilot intervention study used a convenience sample of 10 young people with autism (10–16 years) to evaluate the effectiveness of five 1 hr sessions of narrative therapy conducted over 10 weeks. The study used the parent-rated Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) as the primary outcome measure. Secondary outcome measures were the Kessler-10 Scale of Psychological Distress (K-10), the Beck Hopelessness Scale, and a stress biomarker, the salivary cortisol to dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) ratio.

Significant improvement in psychological distress identified through the K-10 was demonstrated. Significant improvement was identified on the Emotional Symptoms Scale of the SDQ. The cortisol:DHEA ratio was responsive and a power analysis indicated that further study is indicated with a larger sample. Narrative therapy has merit as an intervention with young people with autism. Further research is indicated.

Mala German Educational & Child Psychology . Dec2013, Vol. 30 Issue 4, p75-99

This paper evaluates the use of the ‘Tree of Life’ (ToL) intervention with a class of 29 Year 5 pupils (aged 9 and 10-years-old) in a primary school in North London. This was an exploratory study to see if ToL could be adapted to a mainstream education setting and could be used as a whole class intervention. This paper examines the effectiveness of ToL in enhancing the pupils’ self-esteem and in developing their understanding of their own culture and that of their peers. Findings from semi-structured interviews, preand post-intervention, were used to explore the pupils’ baseline knowledge of their own family and cultural background and in their understanding of key concepts such as ‘culture’, ‘ethnicity’, and ‘racism.’ Qualitative analysis was applied to identify key themes emerging from these interviews. Results from quantitative analysis found a significant improvement in the pupil’s self-concept post-intervention. The pupils also reported positive improvements in cultural understanding of themselves and other class members whilst some reported a reduction in racist behaviour. This paper concludes with a discussion of the limitations of the study and advocates that EPs become more involved in utilising strength-based interventions in developing cultural understanding and community cohesion.

Looyeh MY, Kamali K, Shafieian R

Family Research and Development Centre, Faculty of Education, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. [email protected] This study explored the effectiveness of group narrative therapy for improving the school behavior of a small sample of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Fourteen clinics referred 9- to 11-year-old girls with a clinical diagnosis of ADHD were randomly assigned to treatment and wait-list control groups. Posttreatment ratings by teachers showed that narrative therapy had a significant effect on reducing ADHD symptoms 1 week after completion of treatment and sustained after 30 days. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2012 Oct;26(5):404-10. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2012.01.001. Epub 2012 Mar 28. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22999036

Elaine Hannen, Kevin Woods

Educational Psychology in Practice 01/2012; 28(2):187-214. DOI:10.1080/02667363.2012.669362 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02667363.2012.669362?journalCode=cepp20#preview The National Institute for Clinical Excellence identifies educational psychologists as appropriate specialists to deliver interventions to promote the emotional well-being of children and families. A role for practitioner educational psychologists in providing specific therapeutic interventions has also been proposed by commentators. The present study reports an evaluative case study of a narrative therapy intervention with a young person who self-harms. The analysis of data suggests that the narrative therapy intervention was effectively implemented and resulted in attributable gains in emotional well-being, resilience and behaviour for the young person. The authors discuss the role of the educational psychologist in delivering specific therapeutic interventions within a local authority context and school-based setting. Consideration is also made of the development of the evidence base for the effectiveness of narrative therapy intervention with young people who self-harm.

Everett McGuinty, MA, David Armstrong, PhD, John Nelson, MA, and Stephanie Sheeler, BA Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing ISSN 1073-6077 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2011.00305.x/abstract Author contact: [email protected] The intent of this article is to explore the efficacy of both the literal and concrete externalization aspects within narrative therapy, and the implementation of interactive metaphors as a combined psychotherapeutic approach for decreasing anxiety with people who present with high-functioning autism. The purpose of this exploratory article is to propose the use of externalizing metaphors as a treatment modality as a potentially useful way to engage clients. Specifically, a three-step process of change is described, which allows for concretizing affective states and experiences, and makes use of visual strengths of people presenting with an autism spectrum disorder. A selective review was conducted of significant works regarding the process of change in narrative therapy, with particular emphasis on metaphors. Works were selected based on their relevance to the current paper and included both published works (searched via Psyc-INFO) and materials from narrative training sessions. Further research is needed to address the testable hypotheses resulting from the current model. This line of research would not only establish best practices in a population for which there is no broadly accepted treatment paradigm, but would also contribute to the larger fields of abnormal psychology, emotion regulation, and cognitive psychology by further elucidating the complex ways these systems interact.

Lynette P. Vromans & Robert D. Schweitzer (2010)

Psychotherapy Research , 19 March 2010, doi: 10.1080/10503301003591792 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20306354

This study investigated depressive symptom and interpersonal relatedness outcomes from eight sessions of manualized narrative therapy for 47 adults with major depressive disorder. Post-therapy, depressive symptom improvement (d=1.36) and proportions of clients achieving reliable improvement (74%), movement to the functional population (61%), and clinically significant improvement (53%) were comparable to benchmark research outcomes. Post-therapy interpersonal relatedness improvement (d=.62) was less substantial than for symptoms. Three-month follow-up found maintenance of symptom, but not interpersonal gains. Benchmarking and clinical significance analyses mitigated repeated measure design limitations, providing empirical evidence to support narrative therapy for adults with major depressive disorder.

Sommayeh Sadat MacKean *, Hossein Eskandari, Ahmad Borjali , Delaram Ghodsi

* Msc in General Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Allameh Tabatabaii University, Tehran, Iran – Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Allameh Tabatabaii University, Tehran, Iran. Tel: +98- 912- 1868311 , [email protected]

This study was carried out according to importance of body image in overweight women, and in order to compare the effect of diet therapy and narrative therapy on the body image improvement. Materials and Methods: This was a quasi experimental-interventional study. 30 overweight women were selected through randomized sampling method within women who referred to professional clinic of nutrition and diet therapy and they randomly divided to two interventions and one control group. Group 1 only received diet therapy (for 5weeks), group 2 received narrative therapy in addition to diet therapy and control group received no intervention.

Narrative therapy was a group therapy that consisted of 12 sessions and each session last 50 minutes that performed twice a week. Control group received no intervention. Weight of subjects was measured with light cloths by a Seca balance scale to the nearest 0.5 kg and their height was measured by stadio-meter to 0.5 cm. Body Mass Index was calculated by dividing weight (in kg) to squared height (in m2). Data of Body Image were gathered through Multidimensional Body-Self Relation Questionnaire. Data were analyzed by covariance analysis, Tukey and paired t test using SPSS 16 software.

Results: The mean of body image at the beginning of the study in the control group, was 135.20 and it was134.60 after the intervention. In group 1, at the beginning of the study the mean was 148.1 and after the intervention was 147.50. In group 2, at the beginning of the study the mean was 150.80 and after the intervention the result was 163.90. Data analysis showed that at the end of the study diet therapy had no significant effect on developing of body image (P>0.05). But narrative therapy was more effective than diet therapy in developing of body image in overweight women (P<0.001). Conclusion: According to effect of narrative therapy on body image development, this method is more suitable than the other methods which have greater results in weight loss. Pajoohandeh Journal. 2010; 15 (5) :225-232 http://pajoohande.sbmu.ac.ir/browse.php?a_code=A-10-1-655&sid=1&slc_lang=en

Jennifer Poolea, Paula Gardner, Margaret C. Flower & Carolynne Cooper Social Work With Groups, Volume 32, Issue 4, 2009 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01609510902895086#.Uk-lShBKiSo In this article, the authors report on a qualitative study that explored the use of narrative therapy with a diverse group of older adults dealing with mental health and substance misuse issues. Narrative therapy supports individuals to critically assess their lives and develop alternative and empowering life stories that aim to keep the problem in its place. Although the literature suggests this is a promising intervention for individuals, there is a lack of research on narrative therapy and group work. Aiming to address this gap, the authors developed and researched a narrative therapy group for older adults coping with mental health and substance misuse issues in Toronto, Canada. Taking an ethnographic approach, field notes and interviews provided rich data on how, when, and for whom, such a group could be beneficial. Findings contribute to the literature on group work, older adults, and narrative therapy.

Karen Young and Scot Cooper (2008) Journal of Systemic Therapies, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2008, pp. 67–83

Link to full article.

In this article, we will report on the Narrative Therapy Re-Visiting Project. Narrative ways of thinking shape research in ways that strive to center the voice of the therapy participant. We will present qualitative research findings that bring to the forefront the personal thoughts of the participants about what was meaningful and useful in therapeutic conversations. This contribution moves away from solely interpreted understandings of professionals and toward co-composed understandings between professionals and therapy participants. In a follow-up meeting, persons who have come to us for single session therapy/consultation, return to re-visit videotape of the earlier session.

All of the sessions took place in a walk-in clinic and in single session consultations; therefore the feedback is about narrative practice in a single session encounter. The authors systematically document the participants’ accounts and descriptions of meaningful moments and experiences of the therapeutic process using qualitative methodology and attempt to discern from them themes and implications for therapeutic practice.

Lynette Vromans (2008) [PhD thesis, Queensland University of Technology]

The research aim, to investigate the process and outcome of narrative therapy, comprised theoretical and empirical objectives. The first objective was to articulate a theoretical synthesis of narrative theory, research, and practice. The process of narrative reflexivity was identified as a theoretical construct linking narrative theory with narrative research and practice. The second objective was to substantiate this synthesis empirically by examining narrative therapy processes, specifically narrative reflexivity and the therapeutic alliance, and their relation to therapy outcomes. The third objective was to support the proposed synthesis of theory, research, and practice and provide quantitative evidence for the utility of narrative therapy, by evaluating depressive symptom and inter-personal relatedness outcomes through analyses of statistical significance, clinical significance, and benchmarking …

To support this theoretical synthesis, a process-outcome trial evaluated eight-sessions of narrative therapy for 47 adults with major depressive disorder. Dependent process variables were narrative reflexivity (assessed at Sessions 1 and 8) and therapeutic alliance (assessed at Sessions 1, 3, and 8). Primary dependent outcome variables were depressive symptoms and inter-personal relatedness. Primary analyses assessed therapy outcome at pre-therapy, post-therapy, and three-month follow-up and utilized a benchmarking strategy to the evaluate pre-therapy to post-therapy and post-therapy to follow-up gains, effect size and pre-therapy to post-therapy clinical significance … The clinical trial provided empirical support for the utility of narrative therapy in improving depressive symptoms and inter-personal relatedness from pre-therapy to post-therapy: the magnitude of change indicating large effect sizes (d = 1.10 to 1.36) for depressive symptoms and medium effect sizes (d = .52 to .62) for inter-personal relatedness.

Therapy was effective in reducing depressive symptoms in clients with moderate and severe pre-therapy depressive symptom severity. Improvements in depressive symptoms, but not inter-personal relatedness, were maintained three-months following therapy. The reduction in depressive symptoms and the proportion of clients who achieved clinically significant improvement (53%) in depressive symptoms at post-therapy were comparable to improvements from standard psychotherapies, reported in benchmark research. This research has implications for assisting our understanding of narrative approaches, refining strategies that will facilitate recovery from psychological disorder and providing clinicians with a broader evidence base for narrative practice … This thesis was awarded the Outstanding Doctoral Thesis award across the Queensland University of Technology Faculty of Health. Read the complete thesis here .

Read examiner comments here: Examiner number 1 (pdf, 47 KB), Examiner number 2 (pdf, 15 KB).

Lewis Mehl-Madrona, MD, PhD

The Permanente Journal/ Fall 2007/ Volume 11 No. 4

Narrative approaches to psychotherapy are becoming more prevalent throughout the world. We wondered if a narrative-oriented psychotherapy group on a locked, inpatient unit, where most of the patients were present involuntarily, could be useful. The goal would be to help involuntary patients develop a coherent story about how they got to the hospital and what happened that led to their being admitted and link that to a story about what they would do after discharge that would prevent their returning to hospital in the next year.

Sonja Berthold (June 2006)

Funded by Relationships Australia Northern Territory

This is an independent evaluation of a narrative therapy/collective narrative practice project conducted in two Aboriginal communities in Arnhem Land – Yirrkala & Gunyangara. The project aimed to:

- reduce suicidal thinking/behaviour/injury, self-harm and death by suicide

- enhance resilience, respect, resourcefulness, interconnectedness, and mental health of individuals, families, and communities and to reduce prevalence of risk conditions

- increase support available to individuals, families, and communities who have been affected by suicidal behaviours.

The project was conducted in partnership between Dulwich Centre and Relationships Australia Northern Territory. For more information about the project, read: ‘Linking stories and initiatives: A narrative approach to working with the skills and knowledge of communities’ by David Denborough, Carolyn Koolmatrie, Djapirri Mununggirritj, Djuwalpi Marika, Wayne Dhurrkay, & Margaret Yunupingu.

The independent evaluation found:

Did this project work? Yes, this project worked because it:

- reminded people of their strength and of their dreams

- increased the self-esteem and confidence of individual and groups, and reinforced their ability to deal with suicide and suicidal thinking

- created an opportunity for these communities to forge links with another Indigenous community, a link which strengthens and comforts both

- provided an audience for the stories and passed on the responses

- people see that their knowledge and experience is of value to others

- the community came together to celebrate their strengths and abilities

- ensured that local workers were linked into and supporting this process

- left a resource that is still being used.

What was done well?

- Good, thorough consultation with resulted in changes

- Professional and respectful approach

- Project tried to link in outside workers to help the project continue

- The narrative approach was very successful and well accepted

- Connected very strongly with key leaders in each community

- Delivered relevant, interesting, and useful training

- Provided learning opportunity for Yolgnu people through ensuring local people were involved in the narrative approach

- The team were flexible and able to respond to what was needed and have maintained a connection with the communities

- Made sure that they left a resource for the community to use.

To read the entire evaluation, click here (pdf, 307 KB).

Mim Weber, Kierrynn Davis, & Lisa McPhie (2006) Australian Social Work, 59 (4), 391–405. doi: 10.1080/03124070600985970

This paper reports on a study conducted with seven women who identified themselves as experiencing depression as well as an eating disorder and who live in a rural region of northern New South Wales. Self-referred, the women participated in a weekly group for 10 weeks, with a mixture of topics, conducted within a narrative therapy framework. A comparison of pre- and post-group tests demonstrated a reduction in depression scores and eating disorder risk. All women reported a change in daily practices, together with less self-criticism. These findings were supported by a post-group evaluation survey that revealed that externalisation of, and disengagement from, the eating disorder strongly assisted the women to make changes in their daily practices. Although preliminary and short-term, the outcomes of the present study indicate that group work conducted within a narrative therapy framework may result in positive changes for women entangled with depression and an eating disorder.

Margaret L. Keeling, L. Reece Nielson Contemporary Family Therapy , September 2005, Volume 27, Issue 3, pp 435-452

International and minority populations tend to underutilize mental health services, including marriage and family therapy. Models of marriage and family therapy developed in the West may reflect Western values and norms inappropriate for diverse cultural contexts. This article presents an exploratory, qualitative study of a narrative therapy approach with Asian Indian women. This study adds to the small body of narrative-based empirical studies, and has a unique focus on intercultural applications and the experience of participants. Participant experience was examined along four phenomenological dimensions. Findings indicate the suitability of narrative interventions and nontraditional treatment delivery for this population.

Evril Silver, Alison Williams, Fiona Worthington, and Nicola Phillips (1998) Journal of Family Therapy, 20, 413–422.

This is a retrospective audit of the therapy outcome of 108 children with soiling and their families. Fifty-four children were treated by externalizing and 54 comparison children and families were treated by the usual methods in the same clinic. The results from the externalizing group were better and compared favourably with standards derived from previous studies of soiling. Externalizing was rated as much more helpful by parents at follow-up.

David Besa, California Graduate School of Family Psychology (1994) Research on Social Work Practice, 4 (3), 309–325. doi: 10.1177/104973159400400303

This study assessed the effectiveness of Narrative Therapy in reducing parent/child conflicts. Parents measured their child’s progress by counting the frequency of specific behaviours during baseline and intervention phases. The practitioner-researcher used single-case methodology with a treatment package strategy, and the results were evaluated using three multiple baseline designs. Six families were treated using several Narrative Therapy techniques including externalisation, relative influence questioning, identifying unique outcomes and unique accounts, bringing forth unique re-descriptions, facilitating unique circulation, and assigning between-session tasks. Compared to baseline rates, five of six families showed improvements in parent/child conflict, ranging from an 88% to a 98% decrease in conflict. Improvements occurred only when Narrative Therapy was applied and were not observed in its absence.

Fred W. Seymour & David Epston (1989) Australian & New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 10 (3).

Childhood stealing is a distressing problem for families and may have wider community costs since childhood stealers often become adult criminals. This paper describes a therapeutic ‘map’ that emphasises direct engagement of the child, along with his/her family, in regarding the child from ‘stealer’ to ‘honest person’. Analysis of therapy with 45 children revealed a high level of family engagement and initial behaviour change. Furthermore, a follow-up telephone call made 6–12 months after completion of therapy sessions revealed that 80% of the children had not been stealing at all or had substantially reduced rates of stealing. This community practice, which was in part researched by Seymour and Epston, has recently been written up in some detail in ‘ Community approaches – real and virtual – to stealing ’ (pdf, 68 KB) [Epston, D., & Seymour, F. (2008). In Epston, D., Down under and up over: Travels with narrative therapy , Warrington, England: AFT Publishing Limited, pp. 139–156.]

Report by Linzi Rabinowitz. Researchers: Linzi Rabinowitz and Rebecca Goldberg

Hero Books are a psychosocial support intervention developed by Jonathan Morgan (REPSSI) which are informed by narrative therapy ideas. This study presents preliminary evidence to support the contention that the mainstreaming of PSS (psychosocial support) in the South African school curriculum by means of the Hero Book is likely to produce two significant outcomes:

- learners who have undergone the Hero Book process are more likely to perform better in the learning areas of Life Orientation and Language (Home Language and first additional Language) than learners whose educators did not use Hero Books as measured by the same learning outcomes and assessment standards

- learners whose educators used the Hero Book methodology to pursue academic outcomes are more likely to exhibit an improvement in their psychosocial wellbeing than learners whose educators do not use the Hero Book methodology.

A mix of quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis supports these findings. While none of the findings are conclusive, and the study admittedly has limitations, the strongest quantitative finding is this one: 77% of learner’s academic performance as measured by an average mark for all three learning areas (Home Language, First Additional Language, and Life Orientation) improved overall for the Hero book group, as opposed to 55% in the control groups. This finding suggests that the hero book intervention might be pursued purely on its potential as a methodology to enhance academic learning outcomes, and where any improvements in the psychosocial wellbeing of learners is an added bonus of the intervention. The sample size consisted of four control groups and four intervention groups across two research sites, the Western Cape and KwaZulu Natal. There was a total of 172 learners in the control groups and 113 in the intervention groups. For full report, contact Jonathan Morgan: [email protected]

Social media

Subscribe to email news, acknowledgements.

- Open access

- Published: 12 September 2022

Paper 2: a systematic review of narrative therapy treatment outcomes for eating disorders—bridging the divide between practice-based evidence and evidence-based practice

- Janet Conti 1 , 2 ,

- Lauren Heywood 1 ,

- Phillipa Hay 2 , 3 ,

- Rebecca Makaju Shrestha 1 &

- Tania Perich 1 , 2

Journal of Eating Disorders volume 10 , Article number: 138 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

6894 Accesses

2 Citations

30 Altmetric

Metrics details

Narrative therapy has been proposed to have practice-based evidence however little is known about its research evidence-base in the treatment of eating disorders. The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the outcome literature of narrative therapy for eating disorders.

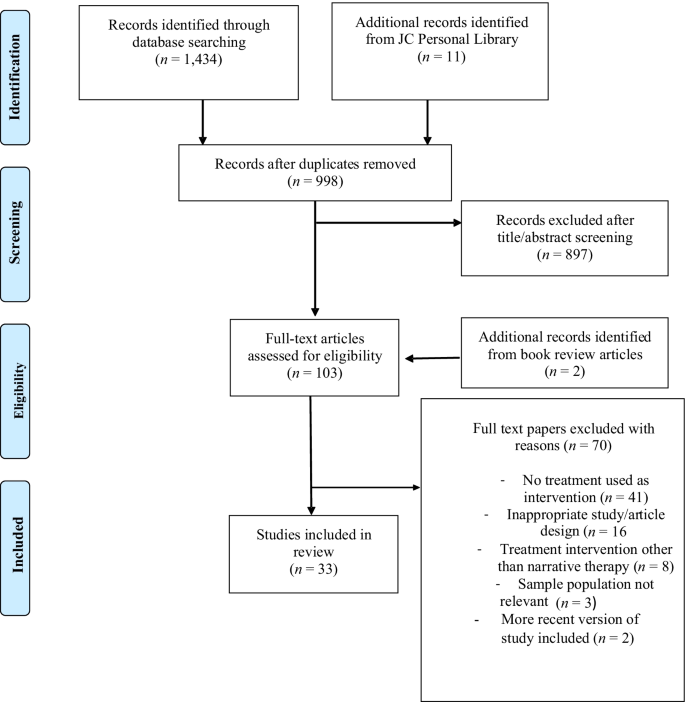

Treatment outcome data were extracted from 33 eligible included studies following systematic search of five data bases. The study is reported according to Preferred Reporting items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.

Of the identified 33 studies, 3 reported positive outcomes using psychometric instruments, albeit some were outdated. Otherwise, reported outcomes were based on therapy transcript material and therapist reports. The most commonly reported treatment outcome was in relation to shifts in identity narratives and improved personal agency with a trend towards under-reporting shifts in ED symptoms. Some improvements were reported in interpersonal and occupational engagement, reduced ED symptoms, and improved quality of life, however, there was an absence of standardized measures to support these reports.

Conclusions

This systematic review found limited support for narrative therapy in the treatment of eating disorders through practice-based evidence in clinician reports and transcripts of therapy sessions. Less is known about systematic treatment outcomes of narrative therapy. There is a need to fill this gap to understand the effectiveness of narrative therapy in the treatment of EDs through systematic (1) Deliveries of this intervention; and (2) Reporting of outcomes. In doing so, the research arm of narrative therapy evidence base will become more comprehensively known.

Plain English summary

Narrative therapy has been proposed as a promising intervention for the treatment of eating disorders. However, the treatment outcomes of narrative therapy for eating disorders are under-researched. This systematic review of the literature has demonstrated limited support for narrative therapy through practice-based evidence in clinician reports and transcripts of therapy sessions. These reports demonstrated how narrative therapy was associated with identity shifts, some symptom reduction, reduced hospitalisations, improved agency over the problem and improvements in quality of life. There is a need for future research to systematically report treatment outcomes. This will fill a gap in research evidence-base for narrative therapy in the treatment of eating disorders.

Eating disorders (EDs) such as anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge eating disorder (BED) and other specified feeding and eating disorders [ 1 ] are prevalent in the community and have implications for physical, psychological and social wellbeing. Around 8.4% of women and 2.2% of men are diagnosed in their lifetimes [ 2 ] and, due to the nature of these conditions, EDs may be difficult to treat and often involve complex, ongoing care and multiple forms of treatment in both inpatient and outpatient settings [ 3 ].

Despite the prevalence and potential to run a chronic course that is associated with adverse impacts on quality of life [ 4 ], the effectiveness of the current evidence-based ED treatments is incomplete. Cochrane and other systematic reviews have shown that family therapies for AN, including Family-Based Therapy [ 5 ] and psychosocial treatments for BN, including cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy [ 6 ] to be most efficacious treatments for these eating disorders, respectively. For example, systematic reviews have found that CBT for BN had moderate to large treatment outcome effects that were maintained over time [ 7 ] and benefits have been reported for adult AN [ 8 ]. There is less data to support the long term benefits of psychological therapies in the treatment of BED, however moderate support has been found for CBT and guided self-help [ 9 ]. Futhermore, a range of rates of relapse in EDs have been reported, as wide as from 9 to 52% [ 10 ], and definitions of relapse and remission rates may vary greatly within the literature.

There has also been increased research into the perspectives of those with a lived experience that goes some way in understanding how and why first line ED treatment do not work for all [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. This has led many to suggest that there may be some sub-types of EDs, ‘severe and enduring’ in nature, that may require more specialised and targeted treatment over a longer period of time [ 14 ]. Others have suggested that treatments need to expand beyond a primary focus on eating behaviour change, for example to the rebuilding of identity outside the ED identity [ 12 ]. Furthermore, expanding the range of ED treatments that may be tailored to the experiencing person may go some way in preventing EDs running a chronic course and reduce the current rates of treatment attrition [ 12 , 15 , 16 ].

For those with severe and enduring EDs, there have been three randomised controlled trials to assess the effectiveness of treatment interventions [ 3 ]. Authors noted that although inpatient programs were found to be potentially effective in the shorter term, no evidence was found for longer term treatment gains for this group [ 3 ]. Types of treatments and settings may not necessarily be more effective than others, with insufficient evidence being found on one review for the superiority of either inpatient or outpatient settings [ 17 ].

Qualitative research of women who have recovered from eating disorders have noted that women experienced a fragmented sense of self when recovering, including rebuilding a more durable sense of identity with reclaiming relationships and self-acceptance also featuring as important [ 18 ]. Narrative therapy is a form of therapy developed by Michael White and David Epston [ 19 , 20 , 21 ] that provides an alternative therapeutic intervention that positions the person as the expert of their life and the problem (including an ED) as external to them. Focusing on identity and its performance, narrative therapy is a process-orientated therapy that focuses on externalizing and unpacking the meaning of problem stories to find and reconstruct hidden identity narratives that have been obscured by the dominant problem narrative [ 19 ]. This form of therapy is based on the philosophies of post-structuralism and social constructivism [ 21 ] and therefore understands that the language used in therapy matters in how identity narratives are constructed. In narrative therapy, therapists prioritise the language used by the person, including the metaphors to depicted their lived ED experience [ 20 , 22 ], and proposes that language shapes identity narratives whose meaning are performed in a person’s life [ 19 , 23 ].

In sum, narrative therapy may hold specific benefits in that it may address elements less considered in other therapies, such as the narrative metaphor to understand identity negotiation and its performance, which may fit the needs and preferences for the treatment of EDs as noted by those with a lived experience [ 12 ]. Narrative therapists have proposed that narrative therapy has “practice-based evidence” [ 24 ] for its effectiveness, however, to our knowledge there is no systematic review evaluating the research evidence for its efficacy in the treatment of EDs.

The current study

The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the literature to assess the reported therapeutic outcomes of narrative therapy in the treatment of ED. This review aims to determine the efficacy of narrative therapy interventions in the treatment of ED and to assess symptom measures and other reported treatment outcomes. A further aim of this review is to describe the range of treatment outcome variables, which have used in the systematically reviewed studies.

This systematic review was carried out as per the guidelines set by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [ 25 ].

The protocol is registered with PROSPERO and is available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020175507 .

Identification and selection of studies

The databases searched included PsychINFO, MEDLINE, EMBASE, SocIndex and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (grey literature) between 1979 and 4th July 2021. Key words used were (anorexi* OR anore*) OR (bulimi* or bulim*) OR (eat* or eating) OR (binge eat*) AND (intervention* OR treatment* OR therapy OR counsel*) AND (narrative).

The inclusion criteria were papers that met the following criteria: (a) published in English, (b) focused on the content of narrative therapy interventions (including specific details of said content); (c) included a sample of individuals in treatment for any ED, with the exception of books that describe narrative therapy interventions and case studies that use illustrative examples. Articles were excluded if they were (a) review papers, (b) not published in English, (c) if full text was unavailable, or (d) did not describe therapy outcomes. Therapy outcomes included scales measuring symptom severity and those described in case studies.

Study selection

One reviewer (LH) ran the identified search terms across all electronic databases, including grey literature. Another reviewer (JC) identified relevant articles from their personal library of narrative therapy resources. All texts were then combined and duplicates removed. The title and abstract of each paper were individually evaluated by two reviewers (LH and JC) for their adherence to inclusion criteria and any discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer (PH). The full text of publications were obtained if they met criteria and any unavailable full texts were excluded. The first reviewer (LH) assessed eligibility of full-text references for inclusion, with assistance from the second reviewer (JC) regarding any uncertainties.

Articles included were assessed at (i) Title screening, (ii) Abstract screening and (iii) Full text screening. Title, and abstract screening was independently undertaken by two reviewers (LH and JC). A third reviewer (PH) resolved any discrepancies. Full text screening was undertaken initially independently by two reviewers (LH and JC) and any discrepancies were resolved between them through discussion.

Articles that were selected for data extraction post full text screening included (i) An eating disorder (ii) Narrative therapy as a treatment of an eating disorder (iii) Full text available in English. Articles were excluded during full text screening included those that (i) Severely lacked any qualitative case study or quantitative data and; (ii) Theoretical papers. Data extraction was completed by LH.

Quality assessment

All included publications were assessed independently by two reviewers (LH and JC) as outlined in paper 1 [ 26 ] using independent quality appraisal assessment tools adapted from the Downs & Black Checklist [ 27 ] and the Joanna Briggs Institute’s Checklist for Text and Opinion [ 28 ].

The preliminary search from the combined databases yielded the results outlined in paper 1 [ 26 ] with 1434 results and an additional 11 articles from JC’s library. The same process was followed as outlined in flowchart for the search results in paper 1 [ 26 ] resulting in the same 33 texts included for this systematic review (Fig. 1 ). Fourteen of the 33 (42%) papers consisted of case study designs ( n = 1), 10 (30%) case studies of between two to four clients, and six (18%) of the papers reported on five or more client cases. Three studies did not report the number of clients from which their data was obtained. Additional study characteristics are reported in paper 1 [ 26 ].

Flow chart of search strategy

Quality appraisal findings–outcome quality ratings

Table S1 and Table S2 (see Additional file 1 ) display the quality appraisal ratings for each of the included references. In relation to outcome data, seven (21%) articles clearly described the main outcomes of the intervention. Treatment outcomes were not reported in 8 (24%) papers and were unclear in 17 (52%) papers. The main findings were clearly reported in 14 (42%) papers and were unclear or not reported in the remaining papers. Overall, the quality ratings for the reporting of treatment outcomes indicated that these were insufficiently reported in the papers.

Synthesis of narrative therapy outcomes

Three papers included quantitative outcome measures and two studies reporting ethics approval. All but one of the 32 papers reported qualitative outcomes, including participant experiences, therapy transcripts and therapist reflections (see Table S3 for data extraction summary, Additional file 1 ).

Quantitative outcomes

Of the three studies reporting quantitative outcomes, one was a group narrative therapy intervention for seven participants with the dual presentations of eating concerns and depression [ 29 ]. The authors outlined that after a 10 week intervention, participants reported a reduction in ED symptoms as measured by the Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI) [ 30 ] and depressive symptoms as measured by the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS) [ 31 ]. They also reported results of a post-treatment survey that through externalisation and disengagement from the ED, participants reported a change in everyday living practices and less self-criticism.

A larger study with 645 participants in Israel reported that an intervention that integrated narrative therapy with motivational interviewing found that the dropout rate was < 10% during the first two months of treatment [ 32 ]. They also reported remission rates using the ED Global Clinical Score [ 33 ] of an average outcome score based on (i) Weight maintenance at least 15% ideal body weight; (ii) Menstruation in women for at least 12 months; (iii) Absence of purging behaviours; (iv) Normalization of eating habits; and (v) Social adjustment based on resumption of school or work. Reported remission rates at the end of treatment [15 months to 4 years]/4 year follow up were 69%/68% (AN) and 81%/83% (BN) respectively. Remission was defined as fully recovered or much improved, where much improved was defined as partial remission with infrequent occurrence of symptoms and return to social and occupational functioning.

A final study reported outcomes for a case study where a 28 year old woman had 10 sessions of narrative therapy over 12 weeks and reported a significant decrease on one of the scales of the EDI-3 (ascetism) [ 34 ] in addition to other qualitative therapist reported improvements.

Qualitative outcomes

There were a range of qualitative outcomes that were cited by the papers as being reported by individuals who experienced narrative therapy for eating problems and some therapist reflections on what they learnt from those with a lived experience. This highlighted to two-way nature of the therapeutic relationship as highlighted by Michael White [ 35 ].

Client outcomes

A range of client outcomes were reported by authors of the included papers. Outcomes most frequently cited related to identity shifts and turning points over the course of therapy. Seventeen of the 33 papers outlined a range of ways that persons with a lived ED experience reclaimed and strengthened a sense of identity outside of the dominant ED identity [ 29 , 36 , 37 , 38 ], including remembering who I am [ 39 ]; visualization of future without ED [ 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 ], improved confidence and self-esteem [ 48 ], self-expression [ 49 ], alongside reclaiming identity from abuse narratives [ 50 , 51 ], and thickening preferred identity through values [ 52 ].

A number of narrative therapy practices were identified as key in the reclaiming of identities hidden by the problem saturated ED identity. A frequently cited practice was externalisation of the problem [ 29 , 45 , 47 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 ] with the use of the person’s language forms or experience-near naming [ 45 ], including metaphor and personification of the problem [ 53 , 54 ]. Other narrative practices that were associated with revealing identities concealed by the ED identity included: the tree of life metaphor [ 46 ] and the deconstruction of dominant discourses (or dismantling of taken-for-granted assumptions) that supported problematic identities [ 42 , 47 , 49 , 55 , 57 ].

Other outcomes reported included: reconnecting individuals with a sense of hope [ 36 , 42 , 46 , 58 , 59 ] and improvements in self-care and self-compassion [ 36 , 39 , 40 , 44 , 50 , 51 ]. Furthermore, narrative therapy was also noted as facilitating individuals in the claiming of their voice [ 40 , 58 ], including through their own speaking positions [ 60 ], and increased assertiveness [ 59 , 61 ].

An increased sense of personal agency, including over the ED, was also noted as an outcome of the narrative therapy therapeutic process [ 29 , 36 , 38 , 41 , 43 , 58 , 61 , 62 ] with two papers talking about how narrative therapy outcomes included increased readiness to change [ 58 , 63 ]. Nine papers outlined a range of ways that individuals' eating practices were reported to have changed including reduced ED symptoms [ 29 , 36 , 40 , 61 ], reduced hospital admissions [ 51 , 59 ]; reduced fear about gaining weight [ 62 ], and discernment of body sensations related to eating [ 36 ] Three articles also reported improvements in associated mood and anxiety symptoms were evident over the course of the narrative therapy intervention [ 48 , 51 , 56 ].

Other treatment outcomes that were reported as having positive impacts on individuals’ relationships included emotional closeness [ 64 ], negotiating clearer boundaries in relationships [ 53 , 65 ], connection with family and friends [ 39 , 43 , 51 , 56 , 59 , 61 ] and others in the treatment [ 46 ]. Four papers also reported that the individuals resumed work and/or study after the narrative therapy treatment intervention [ 51 , 56 , 61 , 65 ].

Therapist reflections–two way impacts of therapeutic intervention

Authors also outlined a range of ways that they were changed through their work as narrative therapists with those with a lived ED experience. This included a connection with their own creativity [ 39 ] and a recognition of the power imbued in professional contexts and the impacts of these on clients [ 60 ] and how therapy can also take the stance as political action to address injustices in society. Therapeutic letter writing was also seen as an opportunity for further reflection by both clients and therapists and also an opportunity for therapists to be open to being corrected by the client [ 64 ].

Narrative therapy outcomes to date are predominantly reported in the form of case studies with transcripts from therapy sessions and therapist reflections to exemplify some of the reported shifts in the context of therapy sessions. Three studies reported outcomes using standardized measures, including the EDI and DASS, with the largest study that included integrated narrative therapy with MI [ 32 ] measuring clinical outcome using the ED Global Clinical Score [ 33 ] that is currently outdated and infrequently used in current ED literature. These studies reported significant improvement in ED symptoms as measured by these instruments; however two of the studies had sample sizes of seven [ 29 ] and one respectively [ 34 ].

Given that identity shifts in the recovering of lost identities are a focus of narrative therapy, the most frequently cited treatment outcomes were stated on these terms. Examples of identity shifts were most frequently linked to the practice of externalisation of the problem with the use of the person’s own experience-near terms. Deconstruction or the unpacking of taken for granted assumptions supporting the ED identity was also cited as a narrative practice that facilitated the finding lost identities. Identity shifts, and addressing these in treatment, has been found to be an important component of ED treatment experiences and/or inadequately addressed in ED treatment interventions from the perspectives of those with a lived ED experience [ 12 ]. Narrative therapy has scope to comprehensively engage individuals (and their families) in finding hidden identity narratives that have been obscured by problem-saturated narratives or the ED identity. The papers included in this systematic review provided a range of exemplars of how narrative therapy practices engaged individuals in finding and strengthening hidden identity narratives.

Identity shifts in narrative therapy are understood as significant because they are not merely descriptive but also performative. For example, in the words of Jerome Bruner [ 23 ] “In the end, we become the autobiographical narratives by which we “tell about” our lives” (p. 694). Michael White & David Epston [ 21 ] have termed this enactment of identity narratives as performance of the meaning. Performing new meanings was noted in the therapy transcripts and therapist reports and included the areas of improved social and occupational functioning, some improvements in ED symptoms, and a reduction in need for hospital admissions. There was significant variability across the studies in the meaning performances that were reported. This may reflect the spirit of narrative therapy that is, the person is the expert of their life and the expert of what outcomes are significant to them. Nevertheless, the absence of consistency in the reporting of outcomes, including ED symptoms, means that the effectiveness of narrative therapy based on the research evidence is largely inconclusive.

The paucity of high quality quantitative research into narrative therapy is not unique to the treatment of EDs. Some of the broader challenges in researching the effectiveness of narrative therapy arise in the context of divergent philosophical paradigms. Psychotherapy research has traditionally assumed positivist epistemologies that require manualisation and replication of therapies [ 66 ]. These traditional research paradigms may be perceived to be at variance with the focus of narrative therapy on personal narratives, social and relational processes with a prioritization of the language and personal agency of the person with a lived experience [ 66 , 67 ]. Nevertheless, narrative therapy research is gradually bridging the divide between positivist and social/relational approaches for example, in outcome research in depression [ 68 ] and post-traumatic stress disorder [ 69 ]. However, studies that focus on both outcomes and therapeutic process have continued to be predominantly exploratory [ 67 ].

Evidence-based practice has three arms: the research evidence and evidence from the clinician and the client’s experiences [ 70 ]. This review has found that there is limited support for narrative therapy for EDs from the practice-based evidence of clinician reports and therapy transcripts. However, in the absence of research that systematically analyses treatment outcomes, including in relation to ED symptoms, it is difficult if not impossible to know whether the narrative therapy intervention widely reported in a case study form will be translate to a broader group of individuals who experience EDs.

Implications

This systematic review highlights how the outcomes of narrative therapy for EDs are currently under-reported and incomplete. However, this does not mean that narrative therapy interventions are ineffective in the treatment of EDs. Rather, it means that [ 1 ] there is an absence of systematic collection and analysis of treatment outcomes in terms of symptom improvement and quality of life, including social, relational and occupational engagement; and [ 2 ] further research is needed to document these and other outcomes that narrative therapists are witnesses to in their therapeutic practices.

In the absence of systematic reporting of outcomes, including relation to ED symptom reduction and improved quality of life, it is not possible at this point to conclude that narrative therapy is effective in the treatment of EDs. Narrative therapy continues to be positioned as having a “fringe role” [ 71 ] (p.77), including in the treatment of EDs. Being unrecognised as an “evidence-based practice” for eating disorders continues to limit narrative therapy practice in the treatment of EDs. This has implications for the breadth of treatment choices available to those with a lived ED experience.

There is a need for narrative therapists and researchers to engage in more systematic outcome research to substantiate what clinicians witness in the therapy room. Greater engagement is needed with the available tools being used to measure the outcome and effectiveness of treatments for EDs. If the existing tools are insufficient to measure the identity shifts and meaning performances that are central to narrative therapy, then new and more comprehensive tools need to be developed the prioritise the voice and personal agency for the experiencing person. Further research is also needed into ways that identity shifts mediate other changes, such as ED symptom reduction. Greater clarity is also needed as to the essential versus desirable components of narrative therapy and how outcome variables might be aligned and mapped onto these therapeutic components. Exploring outcomes through mixed methods design would provide scope to research narrative therapy outcomes in terms of both ED symptom reduction whilst also privileging the voice of the experiencing person in defining what recovery means to them. Given the understanding in narrative therapy that identity is constituted in socio-cultural discourses, identity shifts pre-, post, and within- therapy sessions would be well suited to analysis through critical discourse [ 72 ] and discursive [ 73 ] qualitative methodologies.

Study strengths and limitations

In addition to the study’s strengths and limitations outlined in paper 1 [ 26 ], few of the papers in this review systematically reported on treatment outcome data, including ED symptoms. The majority of articles consisted of a clinician’s overall description of a treatment process with one to five clients. These papers included exemplar transcripts; however, this data was not analysed with qualitative methods. Likewise, very few of the papers used standardized medical or psychological measurements and when these were included, they tended to be outdated.

These omissions from papers on narrative therapy for EDs may be because narrative therapists position the experiencing person, rather than the therapist or researcher, as the expert on their life. This includes what therapeutic shifts are meaningful to the person and what constitutes recovery. Therefore the papers included these types of descriptions of outcomes of narrative therapy. This can be seen as both a strength of the papers and a limitation. A strength in that the papers gave voice to the person with a lived experience to determine what was significant for them in terms of treatment and shifts through therapy. A weakness in that there was an absence of consistency in the reporting of outcomes and an inability to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of narrative therapy in symptom reduction and improvements in quality of life.

Furthermore, there were no papers that reported a control group to compare outcomes between narrative therapy and another therapy or a control group. Because of the characteristics of the papers that met the study selection criteria, the quality assessment was based on text and opinion, and therefore descriptive. There was insufficient data in the papers to do a more comprehensive systematic review of treatment outcomes. Given the few papers that met selection criteria, we included all papers. This led to a bias towards greater inclusion of lower quality case studies by therapists that included their impressions of treatment outcome and selected exemplar transcripts to illustrate these.

Concluding remarks

There are presently insufficient reports in the current literature to be able to make any conclusions or recommendations about the effectiveness of narrative therapy in the treatment of EDs. There is a need for researchers and practitioners to creatively engage in bridging the epistemological gap between positivist psychotherapy research and the practice-based evidence of clinicians who engage clients with narrative therapy. Consideration needs to be given to ways that narrative therapy interventions for EDs may be delivered, and their outcomes systematically measured, with a focus on social and emotional processes and without losing the spirit of narrative therapy where the person is positioned as not the problem and the expert of their life. This research has scope to be influential, not only in systematically researching outcomes for narrative therapy, but more broadly in the field of EDs where the experiencing person is at the centre of discerning what outcomes are significant for them and why, rather than this being decided primarily by researchers.

Abbreviations

Anorexia nervosa

Bulimia nervosa