Search this site

Around the o menu.

Around the O

Historian examines native american genocide, its legacy, and survivors.

The Beekman Professor of Northwest and Pacific History at the University of Oregon believes that in their description of the conflicts with Native Americans, mainstream political and historical discourses in the United States have often obscured this deadly distinction.

RELATED LINKS

Native American Studies Program

Native American Heritage Month 2020

Many Nations Longhouse

Oregon Historical Society’s program on Surviving Genocide (embedded video with talk by Ostler)

Buy the Book

Department of History

His new book, Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas, is a thorough and unflinching review of the evidence. From his vast survey of tribal histories, Ostler concludes that the massacres evidenced a consciously genocidal impulse.

Published in 2019 and the first in a projected two-volume series, Surviving Genocide earned widespread acclaim in the academic field and notices from the popular press followed. The New York Review of Books concluded last summer the book “sets a bar from which subsequent scholarship and teaching cannot retreat.”

Based on rigorous attention to treaty language, military records, demographic data, and the actual words of participants, Surviving Genocide documents the murderous intentions that lurked beneath the idealized self-imaging of a young American nation.

“In order to have a ‘land of opportunity’ required space to expand,” Ostler notes. “Early American senses of ‘freedom’ fundamentally depended upon the taking of Native lands—which almost inevitably would lead to the taking of Native lives.”

From the beginning, he believes, US leaders understood and embraced this grim calculus. However, they obscured their true aims with a series of self-serving narratives built around the ideal of “civilization.” At first, this was held forth as a precious and necessary gift the colonizers were offering to Indigenous populations. Later, “defending civilization” would be invoked as justification to kill them.

While the United States’ own sense of history was framed from the beginning by this “harmful evasion,” Ostler points out that Native people have seldom been fooled.

“A major theme of my book is something I call ‘Indigenous awareness of genocide,’” he says. “The oratory of resistance leaders like Tecumseh shows they recognized that whites intended to kill them and steal their lands.”

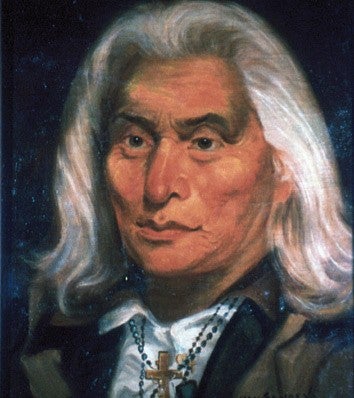

In 1775, the Cherokee chief Tsi’yu-gunsini or “Dragging Canoe” noted:

“Whole Indian Nations have melted away like snowballs in the sun before the white man’s advance. They leave scarcely a name of our people except those wrongly recorded by their destroyers. . .Not being able to point out any further retreat for the miserable Tsalagi (Cherokees), the extinction of the whole race will be proclaimed.”

He was speaking in opposition to a treaty that proposed the Cherokees sell off 20 million acres of homeland—a large portion of present-day Kentucky and Tennessee. This tension exploded with the commencement of independence hostilities in July 1776; some Cherokee leaders sided with the British, and in response the US charged thousands of colonial troops with “the utter extirpation of the Cherokee Nation.”

“During this conflict and others in the so-called Indian Wars, attacking whole communities of Native men, women, and children was planned policy of the US government and army,” Ostler says.

Of course, the intention to commit genocide is not sufficient to ensure its results. Native nations and communities persisted. Like the Cherokees, some that were displaced claimed new homelands, laying the foundations of their perseverance to the present day. And through armed struggle, diplomacy, spiritual fortitude, and cultural stamina, a few eastern tribes overcame tremendous odds and retained portions of their ancestral homelands.

The Potawatomi of Michigan, for example, offer a striking example of political resistance, Ostler says.

Traditional residents of the Great Lakes region, most Potawatomis were displaced farther west following the Treaty of Chicago in 1833. But Leopold Pokagon, leader of the tribe’s Catholic converts, obtained the support of a Michigan Supreme Court justice and negotiated an agreement allowing his community of around 280 people to remain on their traditional homelands. Later in the century, other Potawatomi bands returned to Michigan and established communities. In time, with struggle, these groups also attained land and federal recognition.

The most important part of his book’s title, Ostler insists, is the word “surviving.”

Ostler’s work exemplifies the university’s support for outstanding humanities scholarship. He is one of 10 inaugural Presidential Fellows in Humanistic Study, a fellowship provided by President Michael Schill.

Ostler will use the fellowship for a second volume, which will cover regions of the continent west of the Mississippi River. He can’t predict when he’ll finish it—but notes he’s especially looking forward to the challenge and responsibility of digging into colonialism’s painful history close to home in the Pacific Northwest.

“Here in the Willamette Valley, the University of Oregon is on land that was forcibly taken from the Kalapuya people,” he notes. “Wherever we live in America, I believe any of us is well served to learn the history of the land’s original inhabitants, and to acknowledge the extremes of violence in our own history by calling it what is was: genocide.”

— By Jason Stone, a staff writer for University Communications

Submit Your Story Idea

Subscribe to Around the O

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access Options

- Why Publish with JAH?

- About Journal of American History

- About the Organization of American Historians

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Germs, Genocides, and America's Indigenous Peoples

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Tai S Edwards, Paul Kelton, Germs, Genocides, and America's Indigenous Peoples, Journal of American History , Volume 107, Issue 1, June 2020, Pages 52–76, https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jaaa008

- Permissions Icon Permissions

“Junipero Serra was a nazi not a saint!” “GENOCIDE EQUALS SAINTHOOD?” “NATIVE LIVES MATTER.” These were just a few of the slogans emblazoned on posters and banners during protests opposing the eighteenth-century priest Junípero Serra's canonization in 2015. Accusations that Serra committed genocide also reverberated in the press. Vincent Medina—a Catholic Ohlone Costanoan Esselen Indian and the assistant to the curator at one of California's surviving missions—told the New York Times that canonizing “the leader of the disastrous, genocidal California mission system is a way that the church further legitimized the pain and suffering of Ohlone and countless other California Indians.” The journalist and Pomo descendant Rose Aguilar wrote in the Guardian , “This genocide is just another disgraceful example of Native American history that is forgotten, whitewashed or ignored.” 1

Others—especially the Catholic Church—disputed this characterization of Serra and embraced a familiar refrain among those who object to accusations of genocide. The archbishop of Los Angeles and the Pontifical Commission for Latin America, for example, on a Web site promoting Serra's sainthood, claimed that “during the mission era, most Native Californians who died prematurely did so because of Europeans diseases to which the Indians had no immunity.” Auxiliary Bishop of Los Angeles Edward Clark told the National Catholic Reporter that Spanish missionaries “had no concept of germ theory. How could they know? No one knew. Serra was certainly not culpable.” Gregory Orfalea, a professor of English and a Serra biographer, agreed, writing in a Los Angeles Times op-ed that “what killed most of [California's Indians], in or out of the missions, was disease, lethal germs—which no Spaniard of Serra's time had any clue about.” 2

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Process - a blog for american history

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1945-2314

- Print ISSN 0021-8723

- Copyright © 2024 Organization of American Historians

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

California’s Little-Known Genocide

By: Erin Blakemore

Updated: July 11, 2023 | Original: November 16, 2017

“Gold! Gold from the American River!” Samuel Brannan walked up and down the streets of San Francisco, holding up a bottle of pure gold dust. His triumphant announcement , and the discovery of gold at nearby Sutter’s Mill in 1848, ushered in a new era for California—one in which millions of settlers rushed to the little-known frontier in a wild race for riches.

But though gold spelled prosperity and power for the white settlers who arrived in California in 1849 and after, it meant disaster for the state’s peaceful indigenous population.

In just 20 years, 80 percent of California’s Native Americans were wiped out. And though some died because of the seizure of their land or diseases caught from new settlers, between 9,000 and 16,000 were murdered in cold blood—the victims of a policy of genocide sponsored by the state of California and gleefully assisted by its newest citizens.

California’s genocide is one of the most heinous chapters in the state’s troubled racial history, which also includes forced sterilizations of people of Mexican descent and discrimination and internment of up to 120,000 people of Japanese descent during World War II. But before any of that, one of the new state’s first priorities was to rid itself of its sizable Native American population, and it did so with a vengeance.

California’s native peoples had a long and rich history; hundreds of thousands of Native Americans speaking up to 80 languages populated the area for thousands of years. In 1848, California became the property of the United States as one of the spoils of the Mexican-American War. Then, in 1850, it became a state. For the state and federal government, it was imperative both to make room for new settlers and to lay claim to gold on traditional tribal lands. And settlers themselves—motivated by bigotry and fear of Native peoples—were intent on removing the approximately 150,000 Native Americans who remained.

“Whites are becoming impressed with the belief that it will be absolutely necessary to exterminate the savages before they can labor much longer in the mines with security,” wrote the Daily Alta California in 1849, reflecting the prejudices of the day.

They were assisted by the government, which considered the so-called “Indian Problem” to be one of the biggest threats to its sovereignty. The legal basis for enslaving California’s native people was effectively enshrined into law at the first session of the state legislature, where officials gave white settlers the right to take custody of Native American children. The law also gave white people the right to arrest Native people for minor offenses like loitering or possessing alcohol and made it possible for whites to put Native Americans convicted of crimes to work to pay off the fines they incurred. The law was widely abused and ultimately led to the enslavement of tens of thousands of Native Americans in the name of their “protection.”

This was just the beginning. Peter Hardenman Burnett, the state’s first governor, saw indigenous Californians as lazy, savage and dangerous. Though he acknowledged that white settlers were taking their territory and bringing disease, he felt that it was the inevitable outcome of the meeting of two races.

“That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected,” he told legislators in the second state of the state address in 1851. “While we cannot anticipate this result but with painful regret, the inevitable destiny of the race is beyond the power or wisdom of man to avert.”

Burnett didn’t just refuse to avert such a conflict—he egged it on. He set aside state money to arm local militias against Native Americans. The state, with the help of the U.S. Army, started assembling a massive arsenal. These weapons were then given to local militias, who were tasked with killing native people.

State militias raided tribal outposts, shooting and sometimes scalping Native Americans. Soon, local settlers began to do the killing themselves. Local governments put bounties on Native American heads and paid settlers for stealing the horses of the people they murdered.

“By demonstrating that the state would not punish Indian killers, but instead reward them,” writes historian Benjamin Madley, “militia expeditions helped inspire vigilantes to kill at least 6,460 California Indians between 1846 and 1873.” The U.S Army also joined in the killing, Madley notes, killing at least 1,600 native Californians.

Large massacres wiped out entire tribal populations. In 1850, for example, around 400 Pomo people, including women and children, were slaughtered by the U.S. Cavalry and local volunteers at Clear Lake north of San Francisco. One of the few survivors was a six-year-old girl named Ni’ka, who stayed alive by hiding in the lake and breathing through a reed.

Meanwhile, white settlers and the California government enslaved native people and forced them to labor for ranchers through at least the mid-1860s. Native Americans were then forced onto reservations and their children forced to attend “ Indian assimilation schools .”

An estimated 100,000 Native Americans died during the first two years of the Gold Rush alone; by 1873, only 30,000 indigenous people remained of around 150,000. According to Madley, the state spent a total of about $1.7 million—a staggering sum in its day—to murder up to 16,000 people.

Today, despite all odds, California has the United States’ largest Native American population and is home to 109 federally recognized tribes. But the state’s treatment of native peoples during its founding days—and the role the slaughter of Native Americans played in establishing California’s prosperity—is little known today. California only apologized for the genocide it carried out against its indigenous residents in 2019.

HISTORY Vault: Native American History

From Comanche warriors to Navajo code talkers, learn more about Indigenous history.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Native American Genocide

How it works

When digging deeper into American history and learning about what happened to Native American Indian populations brings extremely dark and unpleasant facts surrounding America’s foundation to the surface. These facts are often used to help undermine the commonly held belief that America is a great nation founded on moral principles of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It is undeniable that Europeans committed many atrocities against the American Indians. This has led some to raise questions of genocide and ultimately charge Europeans for committing it.

It is made clear that these allegations are extremely far-fetched following a close examination of the term “genocide” along with historical facts concerning both the relationships between Europeans and Indians along with the causes of death for American Indians. While it is undeniable that the coming of European settlers to the Americas brought about death as destruction for native populations, charging European settlers with genocide against Native Americans is misguided.

Although the exact numbers are difficult to determine, it is an accepted fact that the population of American Indians’ has declined immensely with the coming of the Europeans to the Americas; however, this does not mean that Europeans committed genocide in America. Early 20th century scholars have estimated there to have been approximately 1 million Indians living in present day America and Canada prior to the coming of European settlers; however, recently scholars likely favoring the allegations of genocide have labeled these previous estimates as “low-counts” and pushed the numbers up settling on a “middle-ground” estimate of 5 million, which is still a fivefold increase over the early estimates (Taylor 40). These numbers are difficult to determine due to a lack of evidence and are highly speculative; however, there is no denying the massive decline in their population following European settlement and this is a widely accepted fact. The massive decline in the Indian population following European contact has become the primary reason for allegations of genocide to be made. Although historians’ estimates vary greatly, there is much agreement on the causes of death which is important information in assessing the allegations of genocide. Jared Diamond, a UCLA professor states that “diseases introduced with Europeans spread from tribe to tribe far in advance of the Europeans themselves killing an estimated 95% of the pre-Columbian Native American population (Diamond 78). These figures help put things into perspective and show that regardless of how many deaths actually occurred, nearly all of the deaths were unintentional and not caused by genocidal action.

There have been claims made that assert that Europeans were involved in biological warfare and intentionally spread the disease through the distribution of small-pox infected blankets. This is a story often told to try to blame Europeans for causing the disease ultimately making them responsible for genocide; however, these claims are extremely inconclusive and are

Cite this page

Native American Genocide. (2020, Feb 04). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/native-american-genocide/

"Native American Genocide." PapersOwl.com , 4 Feb 2020, https://papersowl.com/examples/native-american-genocide/

PapersOwl.com. (2020). Native American Genocide . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/native-american-genocide/ [Accessed: 28 May. 2024]

"Native American Genocide." PapersOwl.com, Feb 04, 2020. Accessed May 28, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/native-american-genocide/

"Native American Genocide," PapersOwl.com , 04-Feb-2020. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/native-american-genocide/. [Accessed: 28-May-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2020). Native American Genocide . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/native-american-genocide/ [Accessed: 28-May-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Ideological growth of a poison Ivy: Columbia’s journey from scholarship to activism

T he images of the recent protests at Columbia University have grabbed the attention of the American public: students chanting for a Palestinian state, “from the river to the sea”; activists setting up a mass tent encampment on the campus lawn; masked occupiers seizing control of Hamilton Hall.

For some, it was a sign that ancient antisemitism had established itself in the heart of the Ivy League. For others, it was déjà vu of 1968, when mass demonstrations last roiled campus.

Columbia president Minouche Shafik feigned surprise. In a statement to students, she expressed “deep sadness” about the campus chaos.

But to anyone who has observed Columbia in recent decades, the upheaval should not come as a surprise.

Behind the images of campus protests lies a deeper, more troubling story: the ideological capture of the university, which inexorably drove Columbia toward this moment.

Columbia for decades has cultivated the precise conditions that allowed the pro-Hamas protests to flourish. The university built massive departments to advance “postcolonialism,” spent hundreds of millions of dollars on “diversity, equity, and inclusion,” and glorified New Left–style student activism as the telos of university life.

Terms like these might sound benign, but the reality is sinister.

As the protests revealed, postcolonial theory is often an academic cover for antisemitism , DEI is frequently a method for enflaming racial grievances and student activism can become a rationalization for violence and destruction.

The university, founded by royal charter in 1754 and a great American institution for more than two centuries, has lost its way. There will need to be a reckoning before it can return to its former glory.

The first part of that process is understanding what went wrong. To do so, we will attempt to uncover the roots of Columbia’s intifada.

The first element driving the current unrest is ideology.

Columbia has long been a pioneer in the theoretical approaches — postcolonialism, decolonization and Islamism — that have shaped progressive opinion of Third World and Middle Eastern affairs.

These systems of thought apply the basic principle of critical theory — that politics is a conflict between oppressed and oppressor groups — to the colonized populations of geopolitical history.

In practice, white Europeans and Jewish Zionists play the oppressor role, while Third World nations, including the Palestinians, play the oppressed. In these ideologies, violence can be not only justified but essential to the process of “liberation.”

At Columbia, this mindset has become gospel . The university’s academic departments employ some of the world’s most prominent postcolonial scholars.

The university press has published dozens of books on the subject, and the course directory lists at least 46 classes offered since the fall with descriptions including the words “postcolonial” or “postcolonialism.”

Faculty and student adherents of the mindset have long focused on the Middle East. Columbia was the academic home of Edward Said, a founding postcolonial scholar who was among the first to translate Marxism and postmodern principles to the study of the relationships between Western and Islamic societies.

Since Said’s death in 2003, the university has built massive programs to continue his work. These have employed increasingly radical figures.

In 2003, for example, the university hired the controversial historian Rashid Khalidi to lead the university’s Middle East Institute. Khalidi once allegedly served as an unofficial spokesman for the Palestine Liberation Organization, which he denies, and has denounced Israel as an “apartheid system in creation” and a “racist” state.

The historian has long supported the campaign to “boycott, divest, and sanction” Israel and, in 2016, was one of 40 Columbia faculty who signed a BDS petition. Early in his Columbia tenure, Khalidi was dismissed from a New York City teacher-training program for allegedly endorsing violence against Israeli soldiers, a charge he also denied.

But Khalidi is only the tip of the spear.

In 2010, Columbia launched its Center for Palestine Studies, which it describes as “the first such center in an academic institution in the United States.” The center currently has 26 affiliated faculty members and hosts a score of visiting professors.

Their orientation is distinctly anti-Israel. One affiliated professor has claimed that Israeli archaeologists faked or manipulated information to legitimize the State of Israel. Another teaches a class called “Settlers and Natives,” which examines “the question of decolonization” and compares the International Criminal Court’s relationship to the “Israel/Palestine” conflict to that of the Nuremberg Court and the Holocaust.

Columbia further expanded its postcolonial program in 2018. That year, the school opened the Center for the Study of Muslim Societies, which serves as a central organizing point for ideologically aligned professors and activists. The center boasts affiliations with 80 “scholars,” including more than a dozen who focus explicitly on postcolonialism, making it one of the largest such programs in the United States.

This sudden expansion of postcolonial programs was funded, in part, by wealthy individuals and a government from the Middle East — a fact Columbia sometimes has tried to hide.

For example, the university kept its donor list secret as it sought to raise an estimated $4 million to endow a chair for Rashid Khalidi. After an uproar, however, administrators succumbed and quietly released a list of 18 donors, which included the United Arab Emirates, a Palestinian oil magnate who supported anti-Israel policies, and other activists.

During that same period, the university also failed to report $250,000 it received from an unidentified Saudi Arabian donor, violating federal and state law.

While the extent of Arab-state funding is unknown, this much is certain: Columbia’s postcolonial studies programs have steadily pushed BDS, Islamist and anti-Israel narratives on campus, with predictable results.

Today’s campus protests parrot the language of such ideologies. For many Columbia students, it is enough that some Israelis look white to condemn them as colonial “oppressors” and to call for the destruction of the Jewish state.

Following the work of Columbia professor Mahmood Mamdani, they have internalized the argument that Israelis are conducting a campaign akin to the American genocide of the Native Americans, or even that of the Nazis against the Jews. Judging from the rhetoric at the pro-Hamas protests, it appears that at least some of the students were paying attention in class.

The second factor driving Columbia’s intifada is diversity, equity and inclusion.

Columbia has built one of the most substantial DEI bureaucracies in the Ivy League.

Former president Lee Bollinger — the respondent in Grutter v. Bollinger, the landmark 2003 Supreme Court case that established the constitutionality of race-based college admissions — was an ardent supporter of DEI and racial preferences. Bollinger, who retired last year, built DEI into the structure of the university.

He boasted in 2021, “Since 2005, Columbia has proudly invested $185 million to diversify our faculty.”

Following the 2020 George Floyd riots, Bollinger leveraged the political unrest to strengthen left-wing ideologies’ grip on campus, under the guise of a “[c]ommitment to [a]ntiracism.”

Today, each school and center at Columbia has a formal DEI team. Almost all have a chief diversity officer, provide DEI training, “identity-based support,” DEI-based recruitment or retention, external partnerships and “DEI focused fundraising.”

Beginning under Bollinger’s leadership, the university opened the floodgates for ideological and racially discriminatory programs. Columbia has made several such big-money efforts in recent years: an initiative to hire faculty who study racism; funding to bolster the number of “underrepresented faculty candidates” hired in STEM fields and across all disciplines; a program to “ensure equity and enhance diversity in our graduate programs’ applicant pools”; and grants “for faculty projects that engage with issues of structural racism.”

To Bollinger, many of these programs were apparently justified by the belief that Columbia was a racist institution. In 2014, for example, the university under the former president’s leadership published a preliminary report declaring that “slavery was intertwined with the life of the college.”

As the document goes on, however, it becomes clear that slavery was no more “intertwined” with Columbia than it was with any other northern institution. Even The New York Times’ coverage of the report noted that the university itself never appeared to have owned slaves and that most Columbians sided with the Union in the Civil War.

But the purpose of the report was not historical accuracy; it was to stoke anger and guilt.

This is characteristic of Columbia’s DEI efforts. Rather than cultivate scholarship, the university and its diversity bureaucracy have fostered a perpetual sense of grievance. Supposedly marginalized students don’t see themselves as individuals in pursuit of knowledge but as a coalition of the oppressed in pursuit of social justice. DEI is not oriented toward truth; it is oriented toward power.

The final element: student activism.

To the outside observer, Columbia’s campus protests might appear spontaneous, driven by students’ own initiative.

But the university has promoted a mythology of left-wing activism and encouraged students to engage in “ongoing antiracism work and activism at Columbia.”

The myth was established in 1968. That year, New Left activists held demonstrations, occupied the Hamilton Hall building and engaged in a dramatic confrontation with police.

For some observers, such as Allan Bloom, who wrote 1987’s “The Closing of the American Mind,” this was the moment that American universities lost their moral authority and capitulated to the activist mob.

But for Columbia’s current administrators, the campus protests were a symbol of rebellious triumph.

The 1968 students were the heroes, in this view; the real enemies were the police and the defenders of order.

As Bollinger said on the 50th anniversary of the 1968 protests, the decision to call in the police to break up protests was “a serious breach of the ethos of the university,” adding that “you simply do not bring police onto a campus.”

The glorification of student activism is not only embedded in administrative culture; it’s also part of the curriculum.

Consider Fawziah Qadir, a Columbia-affiliated education professor and critical race theorist, who promises on her personal website to “transform education into a tool for liberation.” Qadir teaches a course called “Making Change: Activism, Social Movement” at the university. According to the description, the course teaches “the ways people power has pushed for change in the United States educational landscape” and calls on students to “propose actions” for activist campaigns in the future.

Under these conditions, it’s hard to blame Columbia students for taking the protests to excess. They were recruited, taught, and trained to do precisely what they’ve done.

The real scandal is that the university has long since relinquished its role as the responsible authority . There should be no sympathy for president Shafik and other administrators, who have perpetuated a colossal double standard: teaching students how to conduct a radical left-wing protest, and then arresting them as soon as they did exactly what their university had encouraged them to do.

In any conflict, people naturally want to pick a side. Sometimes, however, no one is worthy of support.

Columbia’s intifada is one such conflict. The students are obviously in the wrong, promoting antisemitism, destroying property and using violent methods to achieve dubious political aims.

The faculty are a disaster: Their ideologies are anathema to scholarly detachment and their re-enactments of 1968 are childish and nihilistic. And the administration is complicit in the entire drama.

Bollinger established the conditions for this disaster, and Shafik did nothing to change them — she saw the light only after it was blinding her.

We don’t have to choose a side, but this does not mean that those of us on the outside have no influence. In recent years, Columbia has received approximately $1 billion in annual federal funding — meaning the American taxpayer is funding the Ivy League intifada.

Congress could change this dynamic tomorrow. Rather than subsidize left-wing activism and pseudo-scholarship, congressional representatives could strip funding from Columbia and other Ivy League universities, impose severe restrictions on discriminatory DEI departments and restrict all future support for left-wing ideological programs such as “decolonization” and “post-colonial theory.”

The faster that Congress can change the structural conditions that underpin these institutions, the better. Rather than boycott, divest and sanction Israel, Congress should boycott, divest and sanction the Ivy League.

Now, there’s an activist campaign the American public could easily support.

Christopher F. Rufo is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, and a contributing editor of City Journal, from which this essay is adapted .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This essay begins with the premise that the issue of genocide in American Indian history is far too complex to yield a simple yes-or-no answer. The relevant history, after all, is a long one (more than five hundred years) involving hundreds of indigenous nations and several European and neo-European empires and imperial nation-states.

On a cool May day in 1758, a 10-year girl with red hair and freckles was caring for her neighbor's children in rural western Pennsylvania. In a few moments, Mary Campbell's life changed ...

Historian Frank Chalk's and sociologist Kurt Jonassohn's 1990 edited collection The History and Sociology of Genocide included essays on Native Americans in colonial New England and in the nineteenth-century U.S. while arguing that Indians suffered genocide, primarily through famine, massacres, and "criminal neglect." That same year ...

The destruction of Native American peoples, cultures, and languages has been characterized as genocide.Debates are ongoing as to whether the entire process and which specific periods or events meet the definitions of genocide or not. Many of these definitions focus on intent, while others focus on outcomes. Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term "genocide", considered the displacement of Native ...

Extract. In his powerful book Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas, Jeffrey Ostler makes a landmark contribution to both Native American and United States history.The first part of an ambitious two-volume chronicle, Surviving Genocide analyzes colonial and federal Indian policy in the eastern United States "from the 1750s to ...

Historian Examines Native American Genocide, its Legacy, and Survivors. January 20, 2021 - 12:09am. Jeffrey Ostler has spent the better part of three decades researching and teaching the thorny legacies of the American frontier. His conclusion: the wars the US government waged against Native Americans from the 1600s to the 1900s differed in a ...

REVIEW ESSAY The Haunting Question of Genocide in the Americas Native America and the Question of Genocide. By Alex Alvarez. Lanham md: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014. ix + 203 pp. Illustrations, notes, index. $40.00. ... frus- various assaults on Native American culture) trating, and for me, ultimately unconvincing that constitute the powerful ...

Arguments for defining what had happened to Native Americans increasingly found their way into American historiography following the collapse of Yugoslavia and the terrible slaughter that occurred there. Alvarez takes a topical approach, discussing disease, wars and massacres, exile (deportation), assimilation (cultural genocide), and yes ...

As a field, genocide studies includes scholarship from nearly all corners of the globe and from diverse eras of history. The events in American West and Native American history represent only a small, yet promising portion of this field of study. A peculiarity of genocide studies is the controversy over what academic research should . 2. Israel ...

and stages, it is difficult to deny that Native Americans experienced genocide. The sheer population loss alone is more than enough evidence; most scholars agree that there was a 95 percent decrease in the population of Native Americans in North America between the arrival of Columbus in 1492 and the end of the 19th century (Plous 2002).

Paul R. Bartrop, ''Episodes from the Genocide of the Native Americans: A Review Essay''. Genocide Studies and Prevention 2, 2 (August 2007): 183-190. 2007 Genocide Studies and Prevention. doi: 10.3138/gsp/006. expansion in North America saw attempts at clearing the land of indigenous populations; of forcibly assimilating these ...

The book, recently released in paperback, meticulously narrates the systematic and brutal campaigns of slaughter and enslavement during which California's indigenous population plunged from as many as 150,000 people to around 30,000. This is a rarely examined part of California's history that was "hidden in plain sight," as Madley said.

native boarding school, seemed to believe that Native peoples were equal to white Americans. Native peoples simply had to be trained in the ways of "civilization" (i.e., white Americans) while abandoning their old ways. Indeed, some schools were even opened at the behest of Native leaders. In 1877, Chief Red Cloud, a

The genocide of Indigenous peoples, colonial genocide, or settler genocide is the intentional elimination of Indigenous peoples as a part of the process of colonialism.. According to certain genocide experts, including Raphael Lemkin - the individual who coined the modern concept of genocide - colonization is intrinsically genocidal. Other scholars view genocide as associated with but ...

An American Genocide was the first book to fully document the U.S. government-sanctioned California Genocide. [1] The book was published by Yale University Press [2] and is used by Yale University. [1] The 692 page book [2] was published on 27 June 2017. [1] It was written by Benjamin Madley, a professor of history at the University of ...

Brendan Lindsay's Murder State: California's Native American Genocide, 1846-1873 (2012) and Benjamin Madley's An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe (2016) removed any doubt that genocide took place in that state's history. Lindsay dove deeply into the greed and fear that drove the commission of mass ...

In just 20 years, 80 percent of California's Native Americans were wiped out. And though some died because of the seizure of their land or diseases caught from new settlers, between 9,000 and ...

Essay On Native American Genocide. Decent Essays. 551 Words. 3 Pages. Open Document. Whether or not the death of Native Americans was a product of genocide has been a widely debated topic. The argument could be for or against the label of "genocide". However, based off of the definition of "genocide", textbook readings, and articles I ...

The act of mutilating enemies is not unusual in world history, and Native Americans sometimes scalped non-Indians, but an examination of bounty programs can serve five functions in reexamining the American genocide debate. First, they indicate sustained, institutionalized killing and its intentional support by.

By the 1800s, 95 percent of the Native Americans have been killed and this genocide had taken the length of 100 years. In 1830, a year after Andrew Jackson was elected president in 1829 the United States Congress had passed the Indian Removal Act. The act had ordered the Native Americans to be relocated in the west.

Native American Genocide. When digging deeper into American history and learning about what happened to Native American Indian populations brings extremely dark and unpleasant facts surrounding America's foundation to the surface. These facts are often used to help undermine the commonly held belief that America is a great nation founded on ...

According to a survey conducted between 2016 and 2018, "36% of Americans almost certainly believe that the United States is guilty of committing genocide against Native Americans." Indigenous author Michelle A. Stanley writes that "Indigenous genocide is largely denied, erased, relegated to the distant past, or presented as inevitable".

Following the work of Columbia professor Mahmood Mamdani, they have internalized the argument that Israelis are conducting a campaign akin to the American genocide of the Native Americans, or even ...

Essay On Native American Genocide. The American government's treatment of Native Americans in the 19th century should be considered genocide. Genocide is the deliberate killing of a large group of people, especially those of a particular ethnic group or nation. And what American governments were doing is literary killing innocent Native ...