The Devastating Effects of Nuclear Weapons

What can nuclear weapons do? How do they achieve their destructive purpose? What would a nuclear war — and its aftermath — look like? In the article that follows, excerpted from Richard Wolfson and Ferenc Dalnoki-Veress’s book “ Nuclear Choices for the Twenty-First Century ,” the authors explore these and related questions that reveal the most horrifying realities of nuclear war.

A Bomb Explodes: Short-Term Effects

The most immediate effect of a nuclear explosion is an intense burst of nuclear radiation, primarily gamma rays and neutrons. This direct radiation is produced in the weapon’s nuclear reactions themselves, and lasts well under a second. Lethal direct radiation extends nearly a mile from a 10-kiloton explosion. With most weapons, though, direct radiation is of little significance because other lethal effects generally encompass greater distances. An important exception is the enhanced-radiation weapon, or neutron bomb, which maximizes direct radiation and minimizes other destructive effects.

An exploding nuclear weapon instantly vaporizes itself. What was cold, solid material microseconds earlier becomes a gas hotter than the Sun’s 15-million-degree core. This hot gas radiates its energy in the form of X-rays, which heat the surrounding air. A fireball of superheated air forms and grows rapidly; 10 seconds after a 1-megaton explosion, the fireball is a mile in diameter. The fireball glows visibly from its own heat — so visibly that the early stages of a 1-megaton fireball are many times brighter than the Sun even at a distance of 50 miles. Besides light, the glowing fireball radiates heat.

This thermal flash lasts many seconds and accounts for more than one-third of the weapon’s explosive energy. The intense heat can ignite fires and cause severe burns on exposed flesh as far as 20 miles from a large thermonuclear explosion. Two-thirds of injured Hiroshima survivors showed evidence of such flash burns. You can think of the incendiary effect of thermal flash as analogous to starting a fire using a magnifying glass to concentrate the Sun’s rays. The difference is that rays from a nuclear explosion are so intense that they don’t need concentration to ignite flammable materials.

The intense heat can ignite fires and cause severe burns on exposed flesh as far as 20 miles from a large thermonuclear explosion.

As the rapidly expanding fireball pushes into the surrounding air, it creates a blast wave consisting of an abrupt jump in air pressure. The blast wave moves outward initially at thousands of miles per hour but slows as it spreads. It carries about half the bomb’s explosive energy and is responsible for most of the physical destruction. Normal air pressure is about 15 pounds per square inch (psi). That means every square inch of your body or your house experiences a force of 15 pounds. You don’t usually feel that force, because air pressure is normally exerted equally in all directions, so the 15 pounds pushing a square inch of your body one way is counterbalanced by 15 pounds pushing the other way. What you do feel is overpressure , caused by a greater air pressure on one side of an object.

If you’ve ever tried to open a door against a strong wind, you’ve experienced overpressure. An overpressure of even 1/100 psi could make a door almost impossible to open. That’s because a door has lots of square inches — about 3,000 or more. So 1/100 psi adds up to a lot of pounds. The blast wave of a nuclear explosion may create overpressures of several psi many miles from the explosion site. Think about that! There are about 50,000 square inches in the front wall of a modest house — and that means 50,000 pounds or 25 tons of force even at 1 psi overpressure. Overpressures of 5 psi are enough to destroy most residential buildings. An overpressure of 10 psi collapses most factories and commercial buildings, and 20 psi will level even reinforced concrete structures.

People, remarkably, are relatively immune to overpressure itself. But they aren’t immune to collapsing buildings or to pieces of glass hurtling through the air at hundreds of miles per hour or to having themselves hurled into concrete walls — all of which are direct consequences of a blast wave’s overpressure. Blast effects therefore cause a great many fatalities. Blast effects depend in part on where a weapon is detonated. The most widespread damage to buildings occurs in an air burst , a detonation thousands of feet above the target. The blast wave from an air burst reflects off the ground, which enhances its destructive power. A ground burst , in contrast, digs a huge crater and pulverizes everything in the immediate vicinity, but its blast effects don’t extend as far. Nuclear attacks on cities would probably employ air bursts, whereas ground bursts would be used on hardened military targets such as underground missile silos. As you’ll soon see, the two types of blasts have different implications for radioactive fallout.

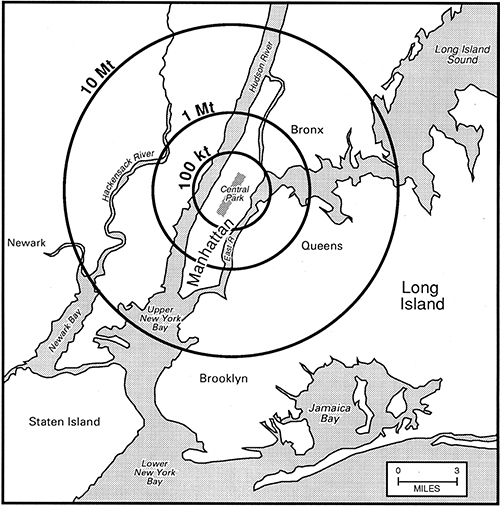

How far do a weapon’s destructive effects extend? That distance — the radius of destruction — depends on the explosive yield. The volume encompassing a given level of destruction depends directly on the weapon’s yield. Because volume is proportional to the radius cubed, that means the destructive radius grows approximately as the cube root of the yield. A 10-fold increase in yield then increases the radius of destruction by a factor of only a little over two. The area of destruction grows faster but still not in direct proportion to the yield. That relatively slow increase in destruction with increasing yield is one reason why multiple smaller weapons are more effective than a single larger one. Twenty 50-kiloton warheads, for example, destroy nearly three times the area leveled by a numerically equivalent 1-megaton weapon.

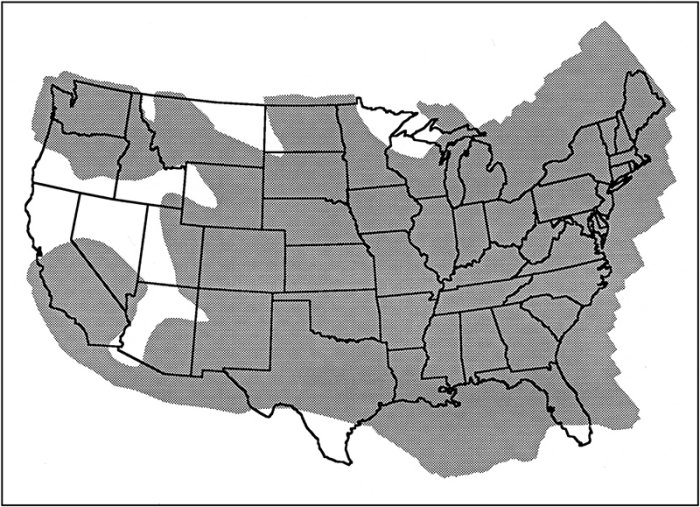

What constitutes the radius of destruction also depends on the level of destruction you want to achieve. Roughly speaking, though, the distance at which overpressure has fallen to about 5 psi is a good definition of destructive radius. Many of the people within this distance would be killed, although some wouldn’t. But some would be killed beyond the 5-psi distance, making the situation roughly equivalent to having everyone within the 5-psi circle killed and everyone outside surviving. The image to the left shows how the destructive zone varies with explosive yield for a hypothetical explosion. This is a simplified picture; a more careful calculation of the effects of nuclear weapons on entire populations requires detailed simulations that include many environmental and geographic variables.

The blast wave is over in a minute or so, but the immediate destruction may not be. Fires started by the thermal flash or by blast effects still rage, and under some circumstances they may coalesce into a single gigantic blaze called a firestorm that can develop its own winds and thus cause the fire to spread. Hot gases rise from the firestorm, replaced by air rushing inward along the surface at hundreds of miles per hour. Winds and fire compound the blast damage, and the fire consumes enough oxygen to suffocate any remaining survivors.

During World War II, bombing of Hamburg with incendiary chemicals resulted in a firestorm that claimed 45,000 lives. The nuclear bombing of Hiroshima resulted in a firestorm; that of Nagasaki did not, likely because of Nagasaki’s rougher terrain. The question of firestorms is important not only to the residents of a target area: Firestorms might also have significant long-term effects on the global climate, as we’ll discuss later.

Both nuclear and conventional weapons produce destructive blast effects, although of vastly different magnitudes. But radioactive fallout is unique to nuclear weapons. Fallout consists primarily of fission products, although neutron capture and other nuclear reactions contribute additional radioactive material. The term fallout generally applies to those isotopes whose half-lives exceed the time scale of the blast and other short-term effects. Although fallout contamination may linger for years and even decades, the dominant lethal effects last from days to weeks, and contemporary civil defense recommendations are for survivors to stay inside for at least 48 hours while the radiation decreases.

The fallout produced in a nuclear explosion depends greatly on the type of weapon, its explosive yield, and where it’s exploded. The neutron bomb, although it produces intense direct radiation, is primarily a fusion device and generates only slight fallout from its fission trigger. Small fission weapons like those used at Hiroshima and Nagasaki produce locally significant fallout. But the fission-fusion-fission design used in today’s thermonuclear weapons introduces the new phenomenon of global fallout . Most of this fallout comes from fission of the U-238 jacket that surrounds the fusion fuel. The global effect of these huge weapons comes partly from the sheer quantity of radioactive material and partly from the fact that the radioactive cloud rises well into the stratosphere, where it may take months or even years to reach the ground. Even though we’ve had no nuclear war since the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, fallout is one weapons effect with which we have experience. Atmospheric nuclear testing before the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty resulted in detectable levels of radioactive fission products across the globe, and some of that radiation is still with us.

Fallout differs greatly depending on whether a weapon is exploded at ground level or high in the atmosphere. In an air burst, the fireball never touches the ground, and radioactivity rises into the stratosphere. This reduces local fallout but enhances global fallout. In a ground burst, the explosion digs a huge crater and entrains tons of soil, rock, and other pulverized material into its rising cloud. Radioactive materials cling to these heavier particles, which drop back the ground in a relatively short time. Rain may wash down particularly large amounts of radioactive material, producing local hot spots of especially intense radioactivity. A hot spot in Albany, New York, thousands of miles from the 1953 Nevada test that produced it, exposed area residents to some 10 times their annual background radiation dose. The exact distribution of fallout depends crucially on wind speed and direction; under some conditions, lethal fallout may extend several hundred miles downwind of an explosion. However, it’s important to recognize that the lethality of fallout quickly decreases as short-lived isotopes decay.

Recommended Response to a Nuclear Explosion

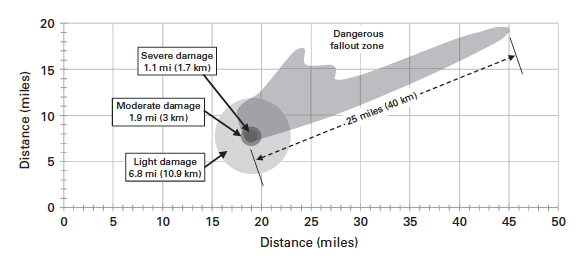

The United States government has recently provided guidance on how to respond to a nuclear detonation. One recommendation is to divide the region of destruction due to blast effects into three separate damage zones. This division provides guidance for first responders in assessing the situation. Outermost is the light damage zone , characterized by “broken windows and easily managed injuries.” Next is the moderate damage zone with “significant building damage, rubble, downed utility lines and some downed poles, overturned automobiles, fires, and serious injuries.” Finally, there’s the severe damage zone , where buildings will be completely collapsed, radiation levels high, and survivors unlikely.

The recommendations also define a dangerous fallout zone spanning different structural damage zones. This is the region where dose rates exceed a whole-body external dose of about 0.1 Sv/hour. First responders must exercise special precautions as they approach the fallout zone in order to limit their own radiation exposure. The dangerous fallout zone can easily stretch 10 to 20 miles (15 to 30 kilometers) from the detonation depending on explosive yield and weather conditions.

Electromagnetic Pulse

A nuclear weapon exploded at very high altitude produces none of the blast or local fallout effects we’ve just described. But intense gamma rays knock electrons out of atoms in the surrounding air, and when the explosion takes place in the rarefied air at high altitude this effect may extend hundreds of miles. As they gyrate in Earth’s magnetic field, the electrons generate an intense pulse of radio waves known as an electromagnetic pulse (EMP).

A single large weapon exploded some 200 miles over the central United States could blanket the entire country with an electromagnetic pulse intense enough to damage computers, communication systems, and other electronic devices. It could also affect satellites used for military communications, reconnaissance, and attack warning. The EMP phenomenon thus has profound implications for a military that depends on sophisticated electronics. In 1962, the United States detonated a 1.4-megaton warhead 250 miles above Johnston Island in the Pacific Ocean. People as far as Australia and New Zealand witnessed the explosion as a red aurora appearing in the night sky. Hawaiians, only 800 miles from the island, experienced a bright flash followed by a green sky and the failure of hundreds of street lights. In total, the Soviet Union and the United States conducted 20 tests of EMP from nuclear detonations. However, it’s unclear how to extrapolate the results to today’s more sensitive and more pervasive electronic equipment.

Since the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963 it has been virtually impossible to study EMP effects directly, although elaborate devices have been developed to mimic the electronic impact of nuclear weapons. Increasingly, crucial electronic systems are “hardened” to minimize the impact of EMP. Nevertheless, the use of EMP in a war could wreak havoc with systems for communication and control of military forces.

Many countries are around the world are developing high-powered microwave weapons which, although not nuclear devices, are designed to produce EMPs. These directed-energy weapons , also called e-bombs , emit large pulses of microwaves to destroy electronics on missiles, to stop cars, to detonate explosives remotely, and to down swarms of drones. Despite these EMP weapons being nonlethal in the sense that there’s no bang or blast wave, an enemy may be unable to distinguish their effects from those of nuclear weapons.

Would the high-altitude detonation of a nuclear weapon to produce EMP or the use of a directed-beam EMP weapon be an act of war warranting nuclear retaliation? With its electronic warning systems in disarray, should the EMPed nation launch a nuclear strike on the chance that it was about to be attacked? How are nuclear decisions to be made in a climate of EMP-crippled communications? These are difficult questions, but military strategists need to have answers.

Nuclear War

So far we’ve examined the effects of single nuclear explosions. But a nuclear war would involve hundreds to thousands of explosions, creating a situation for which we simply have no relevant experience. Despite decades of arms reduction treaties, there are still thousands of nuclear weapons in the world’s arsenals. Detonating only a tiny fraction of these would cause mass casualties.

What would a nuclear war be like? When you think of nuclear war, you probably envision an all-out holocaust in which adversaries unleash their arsenals in an attempt to inflict the most damage. Many people — including your authors — believe that misfortune to be the likely outcome of almost any use of nuclear weapons among the superpowers. But nuclear strategists have explored many scenarios that fall short of the all-out nuclear exchange. What might these limited nuclear wars be like? Could they really remain limited ?

Limited Nuclear War

One form of limited nuclear war would be like a conventional battlefield conflict but using low-yield tactical nuclear weapons. Here’s a hypothetical scenario: After its 2014 annexation of Crimea, Russia attacks a Baltic country with tanks and ground forces while the United States is distracted by a domestic crisis. NATO responds with decisive counterforce, destroying Russian tanks with fighter jets, but this doesn’t quell Russian resolve. Russia responds with even more tanks and by bombing NATO installations, killing several hundred troops. NATO cannot tolerate such aggression and to prevent further Russian advance launches low-yield tactical nuclear weapons with their dial-a-yield positions set to the lowest settings of only 300 tons TNT equivalent. The goal is to signal Russia that it has crossed a line and to deescalate the situation. NATO’s actions are based on fear that if the Russian aggression weren’t stopped the result would be all-out war in northern Europe.

This strategy is actually being discussed in the higher echelons of the Pentagon. The catchy concept is that use of a few low-yield nuclear weapons could show resolve, with the hoped-for outcome that the other party will back down from its aggressive behavior (this concept is known as escalate to deescalate ). The assumption is that the nuclear attack would remain limited, that parties would go back to the negotiating table, and that saner voices would prevail. However, this assumes a chain of events where everything unfolds as expected. It neglects the incontrovertible fact that, as the Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz observed in the 19th century, “Three quarters of the factors on which action in war is based are wrapped in a fog of greater or lesser uncertainty.” Often coined fog of war , this describes the lack of clarity in wartime situations on which decisions must nevertheless be based. In the scenario described, sensors could have been damaged or lines of communication severed that would have reported the low-yield nature of the nuclear weapons. As a result, Russia might feel its homeland threatened and respond with an all-out attack using strategic nuclear weapons, resulting in millions of deaths.

There is every reason to believe that a limited nuclear war wouldn’t remain limited.

There is every reason to believe that a limited nuclear war wouldn’t remain limited. A 1983 war game known as Proud Prophet involved top-secret nuclear war plans and had as participants high-level decision makers including President Reagan’s Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger. The war game followed actual plans but unexpectedly ended in total nuclear annihilation with more than half a billion fatalities in the initial onslaught — not including subsequent deaths from starvation. The exercise revealed that a limited nuclear strike may not achieve the desired results! In this case, that was because the team playing the Soviet Union responded to a limited U.S. nuclear strike with a massive all-out nuclear attack.

What about an attack on North Korea? In 2017, some in the U.S. cabinet advocated for a “bloody nose” strategy in dealing with North Korea’s flagrant violations of international law. This is the notion that in response to a threatening action by North Korea, the U.S. would destroy a significant site to “bloody Pyongyang’s nose.” This might employ a low-yield nuclear attack or a conventional attack. The “bloody nose” strategy relies on the expectation that Pyongyang would be so overwhelmed by U.S. might that they would immediately back down and not retaliate. However, North Korea might see any type of aggression as an attack aimed at overthrowing their regime, and could retaliate with an all-or-nothing response using weapons of mass destruction (including but not necessarily limited to nuclear weapons) as well as their vast conventional force.

In September 2017, during the height of verbal exchanges between President Trump and the North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un, the U.S. flew B-1B Lancer bombers along the North Korean coast, further north of the demilitarized zone than the U.S. had ever done, while still staying over international waters. However, North Korea didn’t respond at all, making analysts wonder whether the bombers were even detected. Uncertainty in North Korea’s ability to discriminate different weapon systems might exacerbate a situation like this one and could lead the North Koreans viewing any intrusion as an “attack on their nation, their way of life and their honor.” This is exactly how the Soviet team in the Proud Prophet war game interpreted it.

What about a limited attack on the United States? Suppose a nuclear adversary decided to cripple the U.S. nuclear retaliatory forces (a virtual impossibility, given nuclear missile submarines, but a scenario considered with deadly seriousness by nuclear planners). Many of the 48 contiguous states have at least one target — a nuclear bomber base, a submarine support base, or intercontinental missile silos — that would warrant destruction in such an attack. The attack, which would require only a tiny fraction of the strategic nuclear weapons in the Russian arsenal, could kill millions of civilians. Those living near targeted bomber and submarine bases would suffer blast and local radiation effects. Intense fallout from ground-burst explosions on missile silos in the Midwest would extend all the way to the Atlantic coast. Fallout would also contaminate a significant fraction of U.S. cropland for up to year and would kill livestock. On the other hand, the U.S. industrial base would remain relatively unscathed, if no further hostilities occurred.

In contrast to attacking military targets, an adversary might seek to cripple the U.S. economy by destroying a vital industry. In one hypothetical attack considered by the congressional Office of Technology Assessment, ten Soviet SS-18 missiles, each with eight 1-megaton warheads, attack United States’ oil refineries. The result is destruction of two-thirds of the U.S. oil-refining capability. And even with some evacuation of major cities in the hypothetical crisis leading to the attack, 5 million Americans are killed.

Each of these “limited” nuclear attack scenarios kills millions of Americans — many, many times the 1.2 million killed in all the wars in our nation’s history. Do we want to entertain limited nuclear war as a realistic possibility? Do we believe nuclear war could be limited to “only” a few million casualties? Do we trust the professional strategic planners who prepare our possible nuclear responses to an adversary’s threats? What level of nuclear preparedness do we need to deter attack?

All-Out Nuclear War

Whether from escalation of a limited nuclear conflict or as an outright full-scale attack, an all-out nuclear war remains possible as long as nuclear nations have hundreds to thousands of weapons aimed at one another. What would be the consequences of all-out nuclear war?

Within individual target cities, conditions described earlier for single explosions would prevail. (Most cities, though, would likely be targeted with multiple weapons.) Government estimates suggest that over half of the United States’ population could be killed by the prompt effects of an all-out nuclear war. For those within the appropriate radii of destruction, it would make little difference whether theirs was an isolated explosion or part of a war. But for the survivors in the less damaged areas, the difference could be dramatic.

Consider the injured. Thermal flash burns extend well beyond the 5-psi radius of destruction. A single nuclear explosion might produce 10,000 cases of severe burns requiring specialized medical treatment; in an all-out war there could be several million such cases. Yet the United States has facilities to treat fewer than 2,000 burn cases — virtually all of them in urban areas that would be leveled by nuclear blasts. Burn victims who might be saved, had their injuries resulted from some isolated cause, would succumb in the aftermath of nuclear war. The same goes for fractures, lacerations, missing limbs, crushed skulls, punctured lungs, and myriad other injuries suffered as a result of nuclear blast. Where would be the doctors, the hospitals, the medicines, the equipment needed for their treatment? Most would lie in ruin, and those that remained would be inadequate to the overwhelming numbers of injured. Again, many would die whom modern medicine could normally save.

A single nuclear explosion might produce 10,000 cases of severe burns requiring specialized medical treatment; in an all-out war there could be several million such cases.

In an all-out war, lethal fallout would cover much of the United States. Survivors could avoid fatal radiation exposure only when sheltered with adequate food, water, and medical supplies. Even then, millions would be exposed to radiation high enough to cause lowered disease resistance and greater incidence of subsequent fatal cancer. Lowered disease resistance could lead to death from everyday infections in a population deprived of adequate medical facilities. And the spread of diseases from contaminated water supplies, nonexistent sanitary facilities, lack of medicines, and the millions of dead could reach epidemic proportions. Small wonder that the international group Physicians for Social Responsibility has called nuclear war “the last epidemic.”

Attempts to contain damage to cities, suburbs, and industries would suffer analogously to the treatment of injured people. Firefighting equipment, water supplies, electric power, heavy equipment, fuel supplies, and emergency communications would be gone. Transportation into and out of stricken cities would be blocked by debris. The scarcity of radiation-monitoring equipment and of personnel trained to operate it would make it difficult to know where emergency crews could safely work. Most of all, there would be no healthy neighboring cities to call on for help; all would be crippled in an all-out war.

Is Nuclear War Survivable?

We’ve noted that more than half the United States’ population might be killed outright in an all-out nuclear war. What about the survivors?

Recent studies have used detailed three-dimensional, block-by-block urban terrain models to study the effects of 10-kiloton detonations on Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles. The results settle an earlier controversy about whether survivors should evacuate or shelter in place: Staying indoors for 48 hours after a nuclear blast is now recommended. That time allows fallout levels to decay by a factor of 100. Furthermore, buildings between a survivor and the blast can block the worst of the fallout, and going deep inside an urban building can lower fallout levels still further. The same shelter-in-place arguments apply to survivors in the non-urban areas blanketed by fallout.

These new studies, however, consider only single detonations as might occur in a terrorist or rogue attack. In considering all-out nuclear war, we have to ask a further question: Then what?

Individuals might survive for a while, but what about longer term, and what about society as a whole? Extreme and cooperative efforts would be needed for long-term survival, but would the shocked and weakened survivors be up to those efforts? How would individuals react to watching their loved ones die of radiation sickness or untreated injuries? Would an “everyone for themselves” attitude prevail, preventing the cooperation necessary to rebuild society? How would residents of undamaged rural areas react to the streams of urban refugees flooding their communities? What governmental structures could function in the postwar climate? How could people know what was happening throughout the country? Would international organizations be able to cope?

Staying indoors for 48 hours after a nuclear blast is now recommended. That time allows fallout levels to decay by a factor of 100.

Some students of nuclear war see postwar society in a race against time. An all-out war would have destroyed much of the nation’s productive capacity and would have killed many of the experts who could help guide social and physical reconstruction. The war also would have destroyed stocks of food and other materials needed for survival.

On the other hand, the remaining supplies would have to support only the much smaller postwar population. The challenge to the survivors would be to establish production of food and other necessities before the supplies left from before the war were exhausted. Could the war-shocked survivors, their social and governmental structure shattered, meet that challenge? That is a very big nuclear question — so big that it’s best left unanswered, since only an all-out nuclear war could decide it definitively.

Climatic Effects

A large-scale nuclear war would pump huge quantities of chemicals and dust into the upper atmosphere. Humanity was well into the nuclear age before scientists took a good look at the possible consequences of this. What they found was not reassuring.

The upper atmosphere includes a layer enhanced in ozone gas, an unusual form of oxygen that vigorously absorbs the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation. In the absence of this ozone layer , more ultraviolet radiation would reach Earth’s surface, with a variety of harmful effects. A nuclear war would produce huge quantities of ozone-consuming chemicals, and studies suggest that even a modest nuclear exchange would result in unprecedented increases in ultraviolet exposure. Marine life might be damaged by the increased ultraviolet radiation, and humans could receive blistering sunburns. More UV radiation would also lead to a greater incidence of fatal skin cancers and to general weakening of the human immune system.

Even more alarming is the fact that soot from the fires of burning cities after a nuclear exchange would be injected high into the atmosphere. A 1983 study by Richard Turco, Carl Sagan, and others (the so-called TTAPS paper) shocked the world with the suggestion that even a modest nuclear exchange — as few as 100 warheads — could trigger drastic global cooling as airborne soot blocked incoming sunlight. In its most extreme form, this nuclear winter hypothesis raised the possibility of extinction of the human species. (This is not the first dust-induced extinction pondered by science. Current thinking holds that the dinosaurs went extinct as a result of climate change brought about by atmospheric dust from an asteroid impact; indeed, that hypothesis helped prompt the nuclear winter research.)

The original nuclear winter study used a computer model that was unsophisticated compared to present-day climate models, and it spurred vigorous controversy among atmospheric scientists. Although not the primary researcher on the publication, Sagan lent his name in order to publicize the work. Two months before Science would publish the paper, he decided to introduce the results in the popular press. This backfired, as Sagan was derided by hawkish physicists like Edward Teller who had a stake in perpetuating the myth that nuclear war could be won and the belief that a missile defense system could protect the United States from nuclear attack. Teller called Sagan an “excellent propagandist” and suggested that the concept of nuclear winter was “highly speculative.” The damage was done, and many considered the nuclear winter phenomenon discredited.

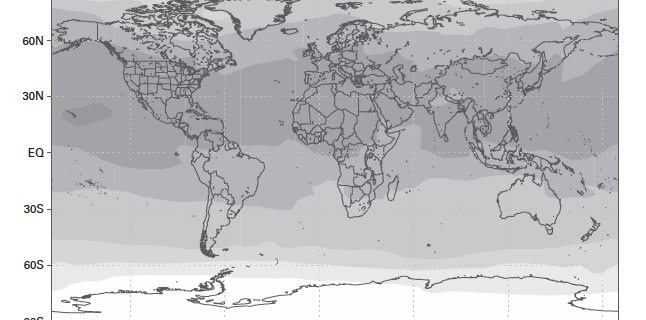

But research on nuclear winter continued. Recent studies with modern climate models show that an all-out nuclear war between the United States and Russia, even with today’s reduced arsenals, could put over 150 million tons of smoke and soot into the upper atmosphere. That’s roughly the equivalent of all the garbage the U.S. produces in a year! The result would be a drop in global temperature of some 8°C (more than the difference between today’s temperature and the depths of the last ice age), and even after a decade the temperature would have recovered only 4°C. In the world’s “breadbasket” agricultural regions, the temperature could remain below freezing for a year or more, and precipitation would drop by 90 percent. The effect on the world’s food supply would be devastating.

Even a much smaller nuclear exchange could have catastrophic climate consequences. The research cited above also suggests that a nuclear exchange between India and Pakistan, involving 100 Hiroshima-sized weapons, would shorten growing seasons and threaten annual monsoon rains, jeopardizing the food supply of a billion people. The image below shows the global picture one month after this hypothetical 100-warhead nuclear exchange.

Nuclear weapons have devastating effects. Destructive blast effects extend miles from the detonation point of a typical nuclear weapon, and lethal fallout may blanket communities hundreds of miles downwind of a single nuclear explosion. An all-out nuclear war would leave survivors with few means of recovery, and could lead to a total breakdown of society. Fallout from an all-out war would expose most of the belligerent nations’ surviving populations to radiation levels ranging from harmful to fatal. And the effects of nuclear war would extend well beyond the warring nations, possibly including climate change severe enough to threaten much of the planet’s human population.

Debate about national and global effects of nuclear war continues, and the issues are unlikely to be decided conclusively without the unfortunate experiment of an actual nuclear war. But enough is known about nuclear war’s possible effects that there is near universal agreement on the need to avoid them. As the great science communicator and astronomer Carl Sagan once said, “It’s elementary planetary hygiene to clean the world of these nuclear weapons.” But can we eliminate nuclear weapons? Should we? What risks might such elimination entail? Those are the real issues in the ongoing debates about the future of nuclear weaponry.

Richard Wolfson is Benjamin F. Wissler Professor of Physics at Middlebury College. Ferenc Dalnoki-Veress is Scientist-in-Residence at the Center for Nonproliferation Studies of the Middlebury Institute of International Studies. This article is excerpted from their book “ Nuclear Choices for the Twenty-First Century: A Citizen’s Guide. “

air burst A nuclear explosion detonated at an altitude—typically, thousands of feet—that maximizes blast damage. Because its fireball never touches the ground, an air burst produces less radioactive fallout than a ground burst.

blast wave An abrupt jump in air pressure that propagates outward from a nuclear explosion, damaging or destroying whatever it encounters.

direct radiation Nuclear radiation produced in the actual detonation of a nuclear weapon and constituting the most immediate effect on the surrounding environment.

electromagnetic pulse (EMP) An intense burst of radio waves produced by a high-altitude nuclear explosion, capable of damaging electronic equipment over thousands of miles.

fallout Radioactive material, mostly fission products, released into the environment by nuclear explosions.

fireball A mass of air surrounding a nuclear explosion and heated to luminous temperatures.

firestorm A massive fire formed by coalescence of numerous smaller fires.

ground burst A nuclear explosion detonated at ground level, producing a crater and significant fallout but less widespread damage than an air burst.

nuclear difference Phrase we use to describe the roughly million-fold difference in energy released in nuclear reactions versus chemical reactions.

nuclear winter A substantial reduction in global temperature that might result from soot injected into the atmosphere during a nuclear war.

overpressure Excess air pressure encountered in the blast wave of a nuclear explosion. Overpressure of a few pounds per square inch is sufficient to destroy typical wooden houses.

radius of destruction The distance from a nuclear blast within which destruction is near total, often taken as the zone of 5-pound-per-square-inch overpressure.

thermal flash An intense burst of heat radiation in the seconds following a nuclear explosion. The thermal flash of a large weapon can ignite fires and cause third-degree burns tens of miles from the explosion.

In the 75 years since the first successful test of a plutonium bomb, nuclear weapons have changed the face of warfare. Here, troops in the 11th Airborne division watch an atomic explosion at close range in the Las Vegas desert on November 1, 1951.

- HISTORY & CULTURE

How the advent of nuclear weapons changed the course of history

Many scientists came to regret their role in creating a weapon that can obliterate anyone and anything in its vicinity in seconds.

At 5:30 a.m. on July 16, 1945, a light brighter than the sun radiated over New Mexico. The fireball annihilated everything in the vicinity, then produced a mushroom cloud that billowed more than seven miles high.

In the aftermath, the scientists who had produced the blast laughed and shook hands and passed around celebratory drinks. Then they settled into grim thought about the deadly potential of the weapon they had created. They had just produced the world’s first nuclear explosion. ( Here's what happened that day in the desert. )

The test, code-named “Trinity,” was a triumph; it proved that scientists could harness the power of plutonium fission. It thrust the world into the atomic age, changing warfare and geopolitical relations forever. Less than a month later, the U.S. dropped two nuclear weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan—further proving it was now possible to obliterate large swaths of land and kill masses of people in seconds.

In August 1945, the United States decided to drop its newly developed nuclear weapons on the Japanese cities Hiroshima and Nagasaki in an attempt to end World War II. In this photograph, an unidentified man stands next to a tiled fireplace where a house once stood in Hiroshima on Sept. 7, 1945.

Scientists had been trying to figure out how to produce nuclear fission—a reaction that happens when atomic nuclei are split, producing a massive amount of power—since the phenomenon’s discovery in the 1930s. Nazi Germany was first to try to weaponize such energy, and word of its efforts leaked out of the country along with political dissidents and exiled scientists, many of them German Jews.

In 1941, after emigre physicist Albert Einstein warned President Franklin Delano Roosevelt that Germany might be trying to develop a fission bomb, the United States joined the first nuclear arms race. It launched a secret atomic research project, code-named the Manhattan Project, bringing together the nation’s most eminent physicists with exiled scientists from Germany and other Nazi-occupied countries.

The project was carried out at dozens of sites, from Los Alamos, New Mexico, to Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Although it employed an estimated 600,000 people over the life of the project, its purpose was so secret that many of the people who contributed to it had no sense of how their efforts contributed to the larger, coordinated goal. Researchers pursued two paths toward a nuclear weapon: one that relied on uranium and another, more complex path, that relied on plutonium.

For Hungry Minds

After years of research, the Manhattan Project made history in 1945 when the test of “the gadget,” one of three plutonium bombs produced before the end of the war, succeeded. The U.S. had also developed an untested uranium bomb. Despite the obvious potential of these weapons to end or alter the course of the ongoing World War II, many of the scientists who helped develop nuclear technology opposed its use in warfare. Leo Szilard, a physicist who discovered the nuclear chain reaction, petitioned the administration of Harry S. Truman (who had succeeded Roosevelt as president) not to use it in war. But his pleas, which were accompanied by the signatures of scores of Manhattan Project scientists, went unheard .

On August 6, 1945, a B-29 “superbomber” dropped a uranium bomb over Hiroshima in an attempt to force Japan’s unconditional surrender. Three days later, the U.S. dropped a plutonium bomb, identical to the Trinity test bomb, over Nagasaki. The attacks decimated both cities and killed or wounded at least 200,000 civilians. ( For those who survived, memories of the bomb are impossible to forget. )

Japan surrendered on August 15. Some historians argue the nuclear blasts had an additional purpose: to intimidate the Soviet Union. Without a doubt, the blasts kicked off the Cold War .

You May Also Like

The true history of Einstein's role in developing the atomic bomb

How Chien-Shiung Wu changed the laws of physics

What lies beneath Hitler's war lair? Explorers just found out.

Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had already green-lit a nuclear program in 1943, and a year and a half after the bombings in Japan, the Soviet Union achieved its first nuclear chain reaction. In 1949, the U.S.S.R. tested “First Lightening,” its first nuclear device.

Ironically, the United States leadership believed that building a robust nuclear arsenal would act as a deterrent, helping prevent a third world war by showing that the U.S. could crush the U.S.S.R., should it invade Western Europe. But as the U.S. began investing in thermonuclear weapons with hundreds of times the firepower of the bombs it used to end World War II, the Soviets followed on its heels. In 1961, the Soviet Union tested the “ Tsar Bomba ,” a powerful weapon yielding the equivalent of 50 megatons of TNT and producing a mushroom cloud as high as Mount Everest.

“No matter how many bombs they had or how big their explosions grew, they needed more and bigger,” writes historian Craig Nelson. ”Enough was never enough.”

As additional countries gained nuclear capacity and the Cold War reached a fever pitch in the late 1950s and early 1960s, an anti-nuclear movement grew in response to a variety of nuclear accidents and weapons tests with environmental and human tolls.

Scientists and the public began to push first for a ban on nuclear testing and then for disarmament. Einstein—whose initial warning to Roosevelt had been designed to prevent nuclear war, rather than set it in motion—was among them. In a 1955 manifesto, the physicist and a group of intellectuals pleaded for the world to abandon its nuclear weapons. “Here, then, is the problem which we present to you, stark and dreadful and inescapable,” they wrote . “Shall we put an end to the human race; or shall mankind renounce war?”

The urgent issue went unresolved. Then, in 1962, reports of a Soviet arms build-up in Cuba led to the Cuban Missile Crisis, a tense standoff between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. that many feared would end in nuclear catastrophe.

In response to activists’ concerns, the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. (and later Russia) signed a partial test ban treaty in 1963, followed by a nuclear nonproliferation treaty in 1968, and a variety of additional agreements designed to limit the number of nuclear weapons.

Nevertheless, in early 2020 there were an estimated 13,410 nuclear weapons in the world—down from a peak of around 70,300 in 1986— according to the Federation of American Scientists. The FAS reports that 91 percent of all nuclear warheads are owned by Russia and the U.S. The other nuclear nations are France, China, the United Kingdom, Israel, Pakistan, India, and North Korea. Iran is suspected of attempting to build its own nuclear weapon.

Despite the dangers of nuclear proliferation, only two nuclear weapons—the ones dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki—have been deployed in a war. Still, writes the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs, "The dangers from such weapons arise from their very existence.”

Seventy-five years after the Trinity test, humanity has thus far survived the nuclear age. But in a world with thousands of nuclear weapons, constantly changing political alliances, and continued geopolitical strife, the concerns raised by the scientists who birthed the technology that makes nuclear war possible remain.

Related Topics

- NUCLEAR WEAPONS

- WORLD WAR II

- NAZI GERMANY

80 years after Pearl Harbor, here's how the attack changed history

Pearl Harbor was the only WWII attack on the U.S., right? Wrong.

Hidden details from the Battle of the Bulge come to light

That time the British tried to blow up an island

‘A ball of blinding light’: Atomic bomb survivors share their stories

- Paid Content

- Environment

- Photography

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History Magazine

- History & Culture

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Nuclear Weapons

By Bastian Herre, Pablo Rosado, Max Roser and Joe Hasell

This page was first published in August 2013 and last revised in February 2024.

The world’s nuclear powers have more than 12,000 nuclear warheads. These weapons can kill millions directly and, through their impact on agriculture, likely have the potential to kill billions .

Nuclear weapons killed between 110,000 and 210,000 people when the United States used them against the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. 1 They have come close to being used again more than a dozen times since.

This is why countries have worked to limit the proliferation and number of nuclear weapons.

On this page, you can find writing, visualizations, and data on how many states have nuclear weapons, how many warheads they possess, how many oppose them, and how this has changed over time.

For an overview of the risks of nuclear weapons – and how they can be reduced – you can read the following essay:

Nuclear weapons: Why reducing the risk of nuclear war should be a key concern of our generation

The consequences of nuclear war would be devastating. Much more should – and can – be done to reduce the risk that humanity will ever fight such a war

Related topics

Biological and Chemical Weapons

Which countries have pursued, possessed, or used biological and chemical weapons? Which countries have sought to eliminate them?

War and Peace

How common are armed conflict and peace between and within countries? How is this changing over time? Explore research and data on war and peace.

Military Personnel and Spending

How large are countries’ militaries? How much do they spend on their armed forces? Explore global data on military personnel and spending.

See all interactive charts on nuclear weapons ↓

Few countries possess nuclear weapons, but some have large arsenals

Nine countries currently have nuclear weapons: Russia, the United States, China, France, the United Kingdom, Pakistan, India, Israel, and North Korea.

These nuclear powers differ a lot in how many nuclear warheads they have. The chart shows that while most have dozens or a few hundred warheads, Russia and the United States have thousands of them.

The chart also shows that the warheads differ in how — and how quickly — they can be used: some are designed for strategic use away from the battlefield, such as against arms industries or infrastructure, while others are for nonstrategic, tactical use on the battlefield.

And while some warheads are not deployed, or even retired and queued for dismantlement, a substantial share of them is deployed on ballistic missiles or bomber bases and can be used quickly.

A lof of countries have given up obtaining nuclear weapons

The number of countries that possess nuclear weapons has never been higher. Only one country — South Africa — entirely dismantled its arsenal .

But, as the chart shows, many more states considered or pursued nuclear weapons, and almost all of them stopped.

In the late 1970s, more than a dozen countries considered or worked to acquire them. Recently, only Syria has considered nuclear weapons and only Iran has pursued building them .

The number of nuclear weapons has declined substantially since the end of the Cold War

After increasing for almost half a century after their creation in the 1940s, nuclear arsenals reached over 60,000 warheads in 1986.

Since then we have seen a reversal of this trend, as the chart shows. The nuclear powers reduced their arsenals a lot in the following decades, and the number of warheads fell below 20,000 in the 2010s.

The decline has slowed since then, and the total stockpile still consists of more than 10,000 warheads. Some countries have also been expanding their arsenals.

The destructiveness of nuclear arsenals has declined

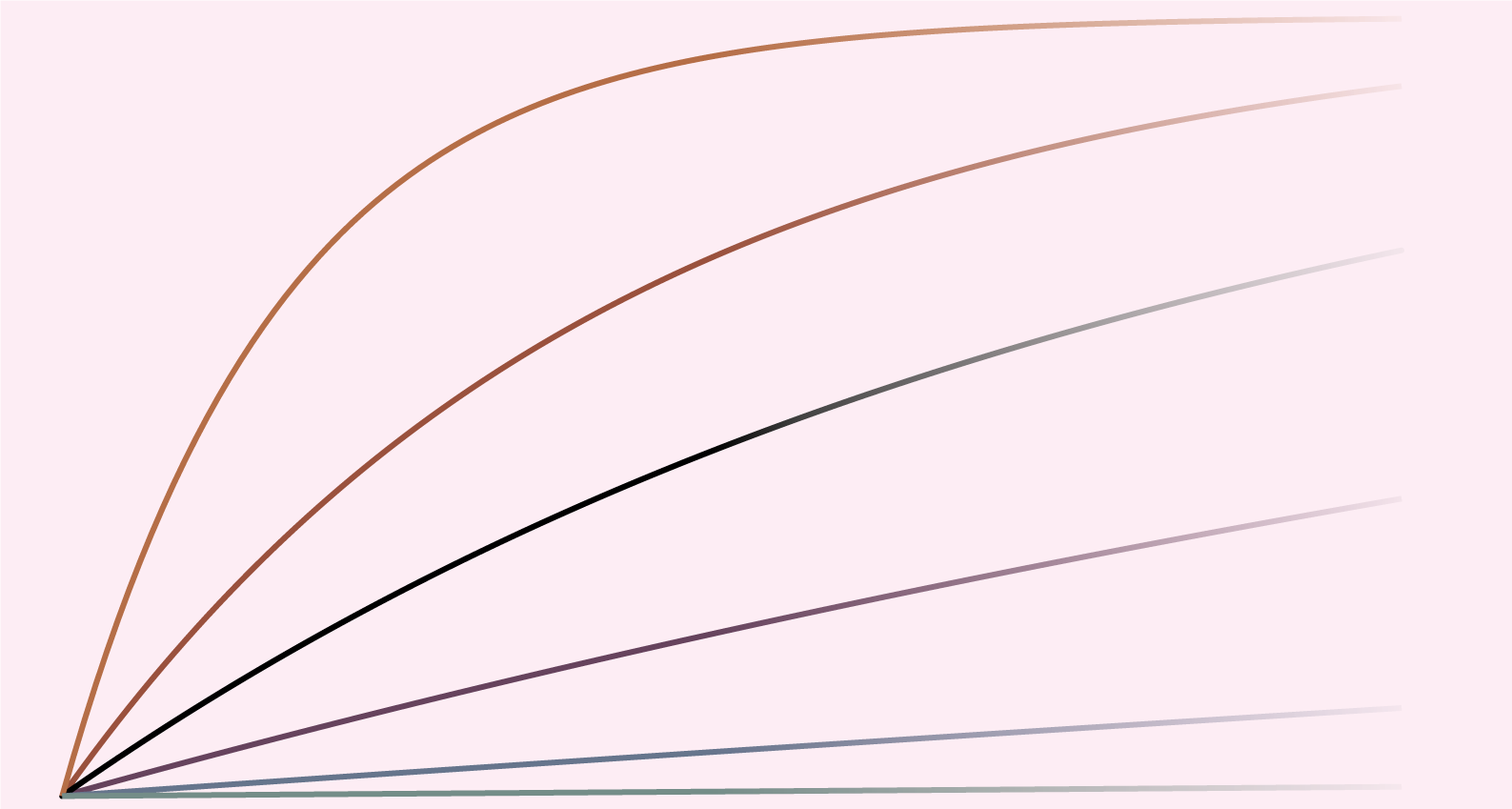

A simple count of the number of warheads, as shown in the previous chart, does not consider that these weapons differ in their explosive power. It also does not consider that not all of them can be used at once.

The data shown in the following chart attempts to take this into account. It considers the destructiveness and deployment of nuclear warheads to arrive at an estimate of the explosive power of nuclear weapons deliverable in a first strike.

We see that the United States rapidly developed much more powerful warheads in the 1950s. The Soviet Union increased the destructiveness of its weapons more slowly but ultimately reached similar levels.

The destructive potential of first-strike warheads peaked at more than 15,000 Mt in the early 1980s. This amounts to more than a million Hiroshima bombs. At this peak, first-strike weapons could destroy more than 40% of the total urban land worldwide.

However, the destructiveness of first strikes has been steadily declining for decades, for both the United States and the Soviet Union/Russia.

Yet, it has still been more than 2,500 Mt, with the potential to directly destroy almost 7% of the total urban land worldwide.

Nuclear weapons tests have almost stopped

The nuclear weapons states frequently tested their warheads in the past, but tests now have almost ended.

The chart shows that they peaked in 1962 at 178 tests, mostly conducted by the United States and the Soviet Union. These tests harmed the environment and people, especially indigenous communities.

Tests decreased later during the Cold War and have been nearly absent in the last two decades. The only country that has recently tested nuclear weapons is North Korea.

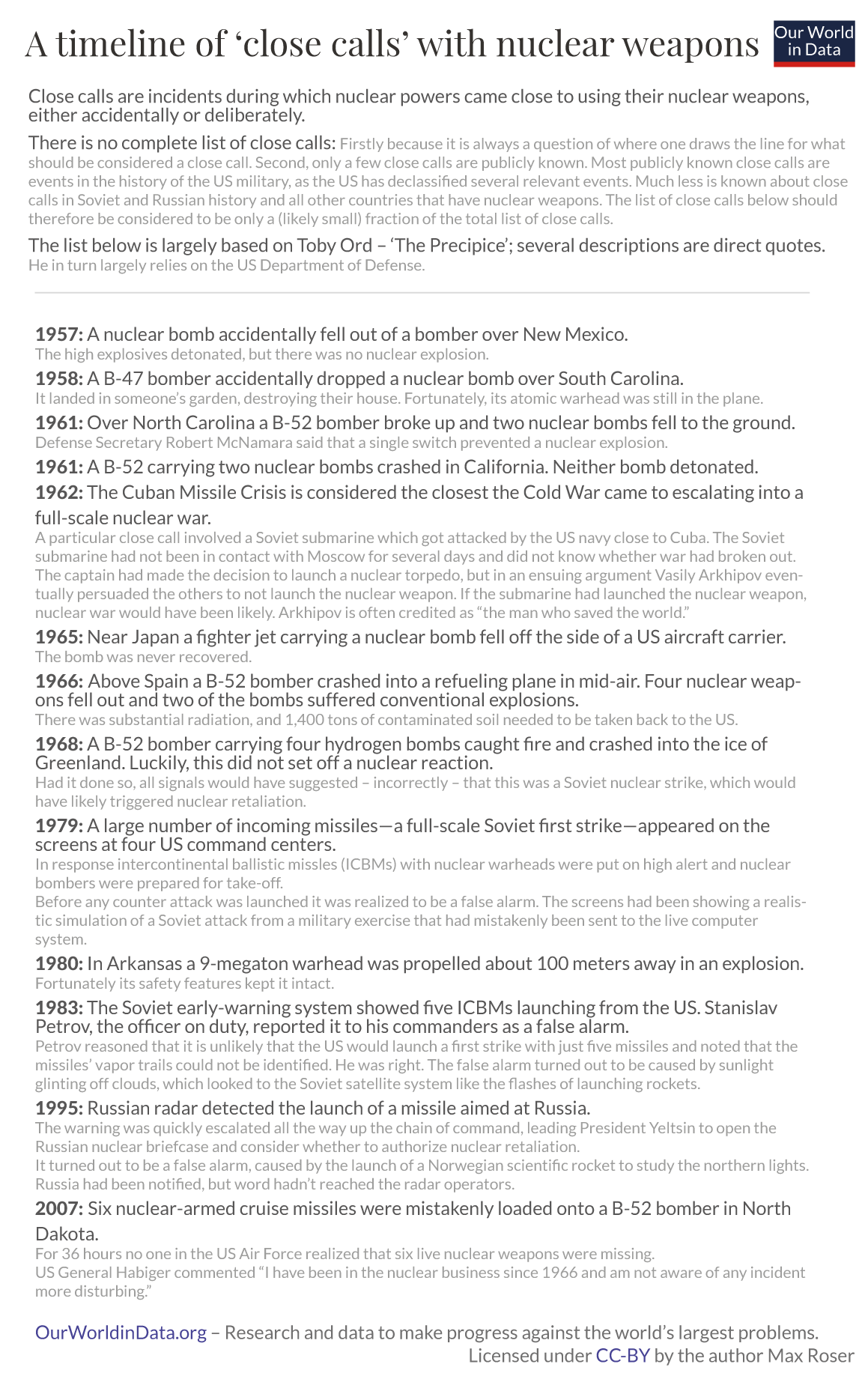

Nuclear weapons have come close to being used a dozen times since World War II

After killing between 110,000 and 210,000 people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, nuclear weapons have come close to being used more than a dozen times again. 1

The chart below shows a timeline of such close calls. 2 We can see that some of them have been accidental, while others have been deliberate.

You can learn more in our article on the risks of nuclear weapons.

Many countries want to limit or abolish nuclear weapons

Countries have sought to reduce the threat posed by nuclear weapons through international cooperation.

Most countries have approved the Partial and Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaties, which seek an end to nuclear weapons tests.

The same goes for the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, whose objective is to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons.

Recently, dozens of countries have approved the Nuclear Prohibition Treaty, whose aim is to end the development and existence of nuclear weapons altogether.

Interactive charts on nuclear weapons

You can find the stories of six survivors — Masakazu Fujii, Wilhelm Kleinsorge, Hatsuyo Nakamura, Terufumi Sasaki, Toshiko Sasaki, and Kiyoshi Tanimoto — in John Hersey’s article Hiroshima .

This list is largely based on Toby Ord’s 2020 book The Precipice. His list can be found in Chapter 4 and Appendix C of his book.

Ord in turn relies mostly on a document from the US Department of Defense from 1981: Narrative Summaries of Accidents Involving US Nuclear Weapons (1950–1980).

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

BibTeX citation

Humanitarian impacts and risks of use of nuclear weapons

10th review conference of the parties to the treaty on the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons.

I. Introduction

1. On 2 March 2020, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) convened a full-day expert meeting on the humanitarian impacts and risks of the use of nuclear weapons. Based on existing and emerging expert research, the meeting aimed to take stock of the humanitarian and environmental consequences of the use and testing of nuclear weapons, as well as the drivers of nuclear risk.

2. In addition to scientific experts from inter alia Sciences Po, Columbia University, Rutgers University, the Federation of American Scientists, Chatham House, the Gender and Radiation Impact Project and the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research, representatives from approximately 45 states and a range of UN agencies and civil society organizations took part in the meeting. This paper provides a summary of the discussions and is published by the ICRC and the IFRC. It does not necessarily represent the views of the participants.

II. The catastrophic humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons

3. The horrific devastation and suffering witnessed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 by Japanese Red Cross and ICRC medical staff, as they attempted to help tens of thousands of dying and wounded people, have left an enduring mark on the entire International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and have driven its advocacy of the prohibition and elimination of nuclear weapons over the last 75 years. [1] A few weeks after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, the ICRC and other organizations began documenting the effects of the nuclear explosions on human health, the environment and medical infrastructure. [2]

4. Evidence of the immediate and longer-term impacts of the use and testing of nuclear weapons has been the subject of scientific investigation ever since. In a major 1987 report, the World Health Organization (WHO) summarized existing research into the impacts on health and health services of nuclear detonations. The report noted inter alia that the blast wave, thermal wave, radiation and radioactive fallout generated by nuclear explosions have devastating short- and long-term effects on the human body, and that existing health services are not equipped to alleviate these effects in any significant way. [3] Since then, the body of evidence of the immediate and longer-term humanitarian impacts of nuclear weapons use and testing, and of the preparedness and capacity of national and international organizations and health systems to provide assistance to the victims of such events, has been growing steadily. [4]

5. In 2013 and 2014, three international conferences were organized by the governments of Norway, Mexico and Austria to comprehensively assess existing knowledge of the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons. [5] The evidence presented at the three conferences demonstrated inter alia the following:

- A nuclear weapon detonation in or near a populated area would – as a result of the blast wave, intense heat, and radiation and radioactive fallout – cause massive death and destruction, trigger large-scale displacement [6] and cause long-term harm to human health and well-being, as well as long-term damage to the environment, infrastructure, socioeconomic development and social order. [7]

- Modern environmental modelling techniques demonstrates that even a “small-scale” use of some 100 nuclear weapons against urban targets would, in addition to spreading radiation around the world, lead to a cooling of the atmosphere, shorter growing seasons, food shortages and a global famine. [8]

- The effects of a nuclear weapon detonation, notably the radioactive fallout carried downwind, cannot be contained within national borders. [9]

- The scale of destruction and contamination after a nuclear detonation in or near a populated area could cause profound social and political disruption as it would take several decades to reconstruct infrastructure and regenerate economic activities, trade, communications, health-care facilities and schools. [10]

- No state or international body could address, in an appropriate manner, the immediate humanitarian emergency nor the long-term consequences of a nuclear weapon detonation in a populated area, nor provide appropriate assistance to those affected. Owing to the massive suffering and destruction caused by a nuclear detonation, it would probably not be possible to establish such capacities, even if attempted, although coordinated preparedness may, nevertheless, be useful in mitigating the effects of an event involving the explosion of an improvised nuclear device. [11]

- Notably, owing to the long-lasting effects of exposure to ionizing radiation, the use or testing of nuclear weapons has, in several parts of the world, left a legacy of serious health and environmental consequences [12] that disproportionally affect women and children. [13]

6. The immediate and longer-term humanitarian and environmental consequences of nuclear weapons use and testing continue to be subject to scientific scrutiny, with emerging evidence and analysis inter alia of the sex- and age-differentiated impacts of ionizing radiation on human health, [14] the long-term impacts of nuclear weapons testing on the environment, [15] including on mortality and infant mortality rates, [16] the consequences of a nuclear war on the global climate, [17] food security, [18] ocean acidification, [19] as well as evidence and analysis of regional preparedness and response measures to nuclear testing. [20] While there are some aspects of these impacts that are not fully understood and require further study (see paragraph 17), these scientific studies reveal new and compelling evidence of long-term harm to human health and the environment from the use and testing of nuclear weapons.

7. There is a particular need for continued and scaled-up efforts to research and understand the humanitarian and environmental consequences of nuclear weapons testing. Communities in former nuclear testing areas – including the Marshall Islands, [21] Kazakhstan, [22] Algeria [23] and the United States [24] – continue to be affected today by the impacts of ionizing radiation released from nuclear tests that occurred decades ago. Many communities report that they do not have sufficient information about their own history of exposure, the current risks of living in a radioactively contaminated area and the intergenerational risks associated with radiation exposure. [25] A lack of transparency and a failure to take the perspectives, lifestyles and needs of communities into account are barriers that need to be overcome in future research efforts.

8. Moreover, while it has been established that women and children are disproportionally affected by ionizing radiation, little is known about the effects of ionizing radiation on reproductive health. Possible questions for further research in this area include: Why is biological sex a factor in radiation harm? Why are the biological sex differences in radiation harm greatest in young children? Is the percentage of reproductive tissue and how it reacts to radiation a contributing factor? [26]

III. The risk of the use of nuclear weapons

9. Evidence of the foreseeable impacts of a nuclear detonation is an integral part of a nuclear weapons risk assessment. Although nuclear weapons have not been used in armed conflict since 1945, there has been a disturbingly high number of close calls in which nuclear weapons were nearly used inadvertently as a result of miscalculation or error. [27] During the three conferences on the humanitarian impacts of nuclear weapons in 2013 and 2014, it was demonstrated that the risks of a nuclear weapon detonation, whether by accident, miscalculation or design, stem notably from:

- the vulnerability of nuclear weapon command-and-control networks to human error and cyberattacks

- the maintaining of nuclear arsenals on high levels of alert, with thousands of weapons ready to be launched within minutes

- the dangers of access to nuclear weapons and related materials by non-state actors.

10. The conferences furthermore observed that international and regional tensions between nuclear-armed states, coupled with existing military doctrines and security policies that give a prominent role to nuclear weapons, increase the risk of nuclear weapons being used, and concluded that, given the catastrophic consequences of a nuclear weapon detonation, the risk of nuclear weapons being used is unacceptable, even if the probability of such an event were considered low. [28]

11. Since the three conferences on the humanitarian impacts of nuclear weapons, the risk that nuclear weapons may be used has increased. While there are different ways to conceptualize nuclear risks and the sources of these risks, the increased probability of nuclear weapons being used is driven by the following interconnected developments:

- After decades of significant cuts in the global nuclear arsenal, the trend towards nuclear reductions is now being replaced by a process of modernization and development of new nuclear weapons with novel, “more usable” capabilities. [29]

- Nuclear weapons are acquiring a more important role in the military doctrines and security strategies of nuclear-armed states, marked, most notably, by a return to considerations of “nuclear warfighting” and an expansion of the circumstances in which the use of nuclear weapons may be considered. [30]

- Broader technological developments, new missile technologies, increased activities and reliance on infrastructure in space, as well as the integration of digital technologies in nuclear command, control and communications, increases complexity in decision-making processes, thereby heightening the risk of misinterpretations and misunderstandings that could trigger the use of nuclear weapons. [31]

- The erosion of the nuclear arms control legal framework – indicated, for example, by the abrogation of the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty – reduces transparency and predictability in policy and decision-making processes, making it more difficult to read the adversary’s intent. [32]

- Broader geopolitical developments, with increasingly tense relationships and the possibility of conflict across several contexts between nuclear-armed and nuclear-allied states, increases the risk of escalation. [33]

12. It is possible to conceptualize the increasing risk of nuclear weapons being used according to the following four risk-of-use scenarios:

a) doctrinal use of nuclear weapons, i.e. the use of nuclear weapons as outlined and envisaged in declared policies, doctrines, strategies and concepts

b) escalatory use, i.e. the use of nuclear weapons in an ongoing situation of tension or conflict

c) unauthorized use, i.e. the non-sanctioned use of nuclear weapons by a non-state actor

d) accidental use, i.e. the use of nuclear weapons through error, including technical malfunction and human error. [34]

13. When assessing the risks arising from technological developments, it is important to consider these technologies both individually and in combination. New technologies may interrelate and depend on each other, thus affecting decision-making systems in unpredictable ways. For example, increased reliance on digital technologies in decision-making processes may create new sources of error that may be difficult to detect, potentially leading to a misplaced overconfidence in the ability of these technologies to deliver accurate information. The introduction and use of new technologies may also lead a state to misinterpret or misunderstand the behaviour of another state, thereby increasing the likelihood of unnecessary escalation. [35]

14. It is important to note that offering an objective and meaningful quantification of these risks may not be possible and engaging in such quantification may create a sense of overconfidence. Objective probability estimates are based on experience and exclude new and unprecedented paths to nuclear catastrophe. Using the language of risk may therefore create a false sense of controllability and manageability by creating an illusion that all the possible paths to disaster have been anticipated and accounted for. The concepts of “luck” and “vulnerability” may better capture our inability to control and manage the possible use of nuclear weapons and therefore provide a more accurate understanding of the dangers posed by these weapons. [36]

IV. Conclusions

15. Research into the various immediate and long-term impacts of nuclear weapons use and testing is important in itself because it informs us of the unique characteristics of these weapons. Such research also provides a crucial basis for humanitarian preparedness and response, and is important in upholding the rights of the individuals and communities affected. The evidence of the humanitarian impacts of nuclear weapons is essential to assess the legality of their use under international humanitarian law (IHL) and it gives a fact-based entry point for discussions about nuclear disarmament and nuclear non-proliferation, more broadly.

16. The evidence of harm caused by the use and testing of nuclear weapons takes on a renewed importance in a world in which the risk of nuclear weapons being used is increasing. From a humanitarian perspective, any measure to reduce the risk of nuclear weapons being used is to be welcomed. Indeed, preventing the use of nuclear weapons is of the utmost urgency. At the same time, nuclear risk reduction cannot become a substitute for the implementation of states’ legally binding obligations to achieve nuclear disarmament, notably those under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. [37] The only way to guarantee that nuclear weapons are never used again is by prohibiting and eliminating them.

17. Although much is already known about the humanitarian and environmental impacts of nuclear weapons, there is a need for more research in certain areas. In particular, we need to understand more about the long-term humanitarian and environmental effects of nuclear weapons testing, as well as the sex- and age-differentiated and, potentially, intergenerational consequences of ionizing radiation.

[1] Linh Schroeder, “The ICRC and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement: Working Towards a Nuclear-Free World since 1945”, 2017: https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2018.1450623 , all web addresses accessed 8 July 2020; Jakob Kellenberger, “Bringing the era of nuclear weapons to an end”,statement by the President of the ICRC to the Geneva Diplomatic Corps, Geneva, 20 April 2010: https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/resources/documents/statement/nuclear-weapons-statement-200410.htm .

[2] ICRC, “ICRC report on the effects of the atomic bomb at Hiroshima”, 2016: https://international-review.icrc.org/articles/icrc-report-effects-atomic-bomb-hiroshima .

[3] WHO, Effects of Nuclear War on Health and Health Services, 1987: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/39199 .

[4] John Borrie and Tim Caughley, An Illusion of Safety: Challenges of Nuclear Weapon Detonations for United Nations Humanitarian Coordination and Response, UNIDIR, 2014, pp. 8–15 for a contextual overview of research into the humanitarian consequences and capacities to respond to nuclear detonations: https://unidir.org/publication/illusion-safety-challenges-nuclear-weapon-detonations-united-nations-humanitarian .

[5] Alexander Kmentt, “The Humanitarian Consequences and Risks of Nuclear Weapons: Taking stock of the main findings and substantive conclusions”, presentation to the ICRC and IFRC expert meeting in Geneva on 2 March 2020 with an overview of the evidence presented at the three conferences; ILPI, “Evidence of Catastrophe: A summary of the facts presented at the three conferences on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons”, ILPI, 2015.

[6] Simon Bagshaw, Population Displacement: Displacement in the Aftermath of Nuclear Weapon Detonation Events, ILPI-UNIDIR, 2014: https://unidir.org/publication/population-displacement-displacement-aftermath-nuclear-weapon-detonation-events .

[7] Article 36, “Economic impact of a nuclear weapon detonation”, 2015: http://www.article36.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Economic-impact.pdf .

[8] Alan Robock et al., “Global Famine after a Regional Nuclear War: Overview of Recent Research”, 2014, presentation to the Vienna Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons: https://www.bmeia.gv.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Zentrale/Aussenpolitik/Abruestung/HINW14/Presentations/HINW14_S1_Presentation_Michael_Mills.pdf .

[9] Matthew McKinzie et al., “Calculating the Effects of a Nuclear Explosion at a European Military Base”, 2014, presentation to the Vienna Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons: https://www.bmeia.gv.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Zentrale/Aussenpolitik/Abruestung/HINW14/Presentations/HINW14_S1_Presentation_NRDC_ZAMG.pdf .

[10] Neil Buhne, “Social and economic impacts: Structural restoration of lives and livelihoods in and around affected areas”, 2013, presentation to the Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons, Oslo: https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/ud/vedlegg/hum/hum_buhne.pdf .

[11] Dominique Loye and Robin Coupland, “Who will assist the victims of use of nuclear, radiological, biological or chemical weapons – and how?”, 2007: https://international-review.icrc.org/articles/who-will-assist-victims-use-nuclear-radiological-biological-or-chemical-weapons-and-how ; ICRC, “Humanitarian assistance in response to the use of nuclear weapons”, 2013: https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/2013/4132-3-nuclear-weapons-humanitarian-assistance-2013.pdf ; John Borrie and Tim Caughley, An Illusion of Safety: Challenges of Nuclear Weapon Detonations for United Nations Humanitarian Coordination and Response, UNIDIR, 2014: https://www.unidir.org/files/publications/pdfs/an-illusion-of-safety-en-611.pdf .

[12] John Borrie, A Harmful Legacy: The Lingering Humanitarian Impacts of Nuclear Weapons Testing, ILPI-UNIDIR, 2014: https://unidir.org/publication/harmful-legacy-lingering-humanitarian-impacts-nuclear-weapons-testing ; Roman Vakulchuk and Kristian Gjerde, Semipalatinks nuclear testing: the humanitarian consequences, Norwegian Institute of International Affairs, 2014: http://large.stanford.edu/courses/2014/ph241/powell2/docs/vakulchuk.pdf .

[13] Anne Guro Dimmen, Gendered Impacts: The Humanitarian Impacts of Nuclear Weapons from a Gender Perspective, ILPI-UNIDIR, 2014: https://unidir.org/publication/gendered-impacts-humanitarian-impacts-nuclear-weapons-gender-perspective .

[14] Mary Olson, “Disproportionate impact of radiation and radiation regulation”, Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 2019: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03080188.2019.1603864 , presented to the ICRC and IFRC expert meeting in Geneva on 2 March 2020. (In November 2022, Olson corrected an error in one of her visualizations of the degree of difference in cancer outcomes from the exposure of young girls and adult males, respectively: A Correction — Gender + Radiation Impact Project )

[15] Maveric K.I.L. Abella et al., “Background gamma radiation and soil activity measurements in the northern Marshall Islands”,

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), 2019: https://www.pnas.org/content/pnas/116/31/15425.full.pdf ; Emlyn W. Hughes et al., “Radiation maps of ocean sediment from the Castle Bravo crater”, PNAS, 2019: https://www.pnas.org/content/pnas/116/31/15420.full.pdf ; Carlisle E. W. Topping et al., “In situ measurement of cesium-137 contamination in fruits from the northern Marshall Islands”, PNAS, 2019: https://www.pnas.org/content/pnas/116/31/15414.full.pdf ; R. Giles Harrison et al., “Precipitation Modification by Ionization”, Physical Review Letters, 2020: https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.198701 .

[16] Kathleen M. Tucker and Robert Alvarez, “Trinity: “The most significant hazard of the entire Manhattan Project””, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 2019: https://thebulletin.org/2019/07/trinity-the-most-significant-hazard-of-the-entire-manhattan-project/ ; Keith Meyers, “Some Unintended Fallout from Defense Policy: Measuring the Effect of Atmospheric Nuclear Testing on American Mortality Patterns”, 2019: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59262540b3db2b0d0d6d7d2b/t/5c81809a419202f922f0cfa4/1551990940274/Fallo%20utMortDraft_3-5-2019.pdf .

[17] Alan Robock et al., “How an India-Pakistan nuclear war could start–and have global consequences”, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 2019: http://climate.envsci.rutgers.edu/pdf/IndiaPakistanBullAtomSci.pdf .

[18] Jonas Jägermeyr et al., “A regional nuclear conflict would compromise global food security”, PNAS, 2020: http://climate.envsci.rutgers.edu/pdf/JagermeyrPNAS.pdf .

[19] Nicole S. Lovenduski et al., “The Potential Impact of Nuclear Conflict on Ocean Acidification”, Geophysical Research Letters, 2020: https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2019GL086246 .

[20] Beyza Unal, Patricia Lewis and Sasan Aghlani, “The Humanitarian Impacts of Nuclear Testing: Regional Responses and Mitigation Measures”, Chatham House, 2017: https://www.chathamhouse.org/publication/humanitarian-impacts-nuclear-testing-regional-responses-and-mitigation-measures .

[21] Susanne Rust, “How the U.S. betrayed the Marshall Islands, kindling the next nuclear disaster”, Los Angeles Times, 2019: https://www.latimes.com/projects/marshall-islands-nuclear-testing-sea-level-rise/ .

[22] Wudan Yan, “The nuclear sins of the Soviet Union live on in Kazakhstan”, Nature, 2019: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-01034-8 .

[23] Johnny Magaleno, “Algerians suffering from French atomic legacy, 55 years after nuke tests”, Al Jazeera, 2015: http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2015/3/1/algerians-suffering-from-french-atomic-legacy-55-years-after-nuclear-tests.html .

[24] Lilly Adams, “The human cost of nuclear weapons is not only a “feminine” concern”, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 2019: https://thebulletin.org/2019/11/the-human-cost-of-nuclear-weapons-is-not-only-a-feminine-concern .

[25] Masaki Koyanagi, presentation to the Second International Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons, 2014: https://www.reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Disarmament-fora/nayarit-2014/statements/Hibakusha-Koyanagi.pdf , giving the perspective of a third-generation hibakusha. The Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF) is currently carrying out a research programme on the children of atomic-bomb survivors.

[26] Mary Olson, presentation to the ICRC and IFRC expert meeting in Geneva on 2 March 2020.

[27] Patricia Lewis et al., “Too Close for Comfort: Cases of Near Nuclear Use and Options for Policy”, Chatham House, 2014: https://www.chathamhouse.org/publications/papers/view/199200 .

[28] Alexander Kmentt, “The Humanitarian Consequences and Risks of Nuclear Weapons: Taking stock of the main findings and substantive conclusions”, presentation to the ICRC and IFRC expert meeting in Geneva on 2 March 2020. The point was also made in the statement, “Never again: Nagasaki must be the last atomic bombing”, International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, 2017: https://www.icrc.org/en/document/never-again-nagasaki-must-be-last-atomic-bombing .

[29] Matt Korda, “The Key Drivers of Nuclear Risk”, presentation to the ICRC and IFRC expert meeting in Geneva on 2 March 2020; Wilfred Wan, presentation to the ICRC and IFRC expert meeting in Geneva on 2 March 2020. For an overview of nuclear modernization programmes, see Benjamin Zala, “How the next nuclear arms race will be different from the last one”, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 2019: https://thebulletin.org/2019/01/how-the-next-nuclear-arms-race-will-be-different-from-the-last-one/ ; Nuclear Notebook: https://thebulletin.org/nuclear-risk/nuclear-weapons/nuclear-notebook/ for updated public information about nuclear weapons programmes.

[30] Ibid. For a discussion about the risk implications of changing doctrines, see Ankit Panda, “Multipolarity, Great Power Competition, and Nuclear Risk Reduction”, chapter three in Wilfred Wan (ed.), Nuclear Risk Reduction: Closing Pathways to Use, 2020: https://unidir.org/publication/nuclear-risk-reduction-closing-pathways-use .

[31] Ibid. Yasmin Afina, presentation to the ICRC and IFRC expert meeting in Geneva on 2 March 2020; For the risk implications of digital technology in nuclear command, see Beyza Unal and Patricia Lewis, “Cybersecurity of Nuclear Weapons Systems: Threats, Vulnerabilities and Consequences”, Chatham House, 2018: https://www.chathamhouse.org/publication/cybersecurity-nuclear-weapons-systems-threats-vulnerabilities-and-consequences . For the risk implications of technological developments, see John Borrie, “Nuclear risk and the technological domain: a three-step approach”, chapter four in Wilfred Wan (ed.), Nuclear Risk Reduction: Closing Pathways to Use, 2020: https://unidir.org/publication/nuclear-risk-reduction-closing-pathways-use .

[32] Ibid. For a discussion about the risk implications of the evaporation of arms control, see Ankit Panda, “Multipolarity, Great Power Competition, and Nuclear Risk Reduction”, chapter three in Wilfred Wan (ed.), Nuclear Risk Reduction: Closing Pathways to Use, 2020: https://unidir.org/publication/nuclear-risk-reduction-closing-pathways-use .

[34] Wilfred Wan, presentation to the ICRC and IFRC expert meeting in Geneva on 2 March 2020; Wilfred Wan (ed.), Nuclear Risk Reduction: Closing Pathways to Use, 2020, chapter one: https://unidir.org/publication/nuclear-risk-reduction-closing-pathways-use .