clock This article was published more than 1 year ago

Opinion The Washington Post guide to writing an opinion article

The Washington Post is providing this news free to all readers as a public service.

Follow this story and more by signing up for national breaking news email alerts.

Each month, The Washington Post publishes dozens of op-eds from guest authors. These articles — written by subject-matter experts, politicians, journalists and other people with something interesting to say — provide a diversity of voices and perspectives for our readers.

The information and tips below are meant to demystify our selection and editing process, and to help you sharpen your argument before submitting an op-ed of your own.

- Guides & Resources

How To Write an Op-ed: A Step By Step Guide

There’s a formula that we call the “ABCs” that can be used to write compelling op-eds, columns, or blogs. The same formula can also be used to write almost any document that offers up an argument or gives advice. This is a “news flash lede,” a comment that will make sense in a moment .

The ABC Formula

This formula for writing op-eds is based on our experience and our op-eds that appeared in the New York Times , the Wall Street Journal , and the Washington Post . I first came across a version of this formula while I was at US News and World Report . It was called “FLUCK,” and we have tweaked it a bit since then.

This is probably obvious, but this ABC formula is meant to guide writers rather than restrict them. In other words, these are recommendations, not a rigid set of instructions.

Better yet, think of the formula as a flexible template for making an effective argument in print—one that you personalize with your specific style, topic, and intended audience in mind.

This guide is divided into five parts.

Part I: Introduction: In this section, we give a brief overview of the approach and discuss the importance of writing and opinion.

Part II: The ABCs: Here we cover the important steps in writing for your audience: Attention, Billboard, and Context.

PART III: The ABCS in Example: In this section, we give you different examples of the ABCs in action and how to effectively use them.

PART IV: Pitching: Here we will go over how to effectively pitch ideas and submit ideas to an editor for publication.

PART V: Final tips and FAQs: Here we go over a few more key things to do and answer the most commonly asked questions.

Part I: Introduction To Op-Eds

Op-eds are one of the most powerful tools in communications today. They can make a career. They can break a career.

But there’s often lots of mystery around editorials and op-eds. I mean: What does op-ed even stand for?

Well, let’s start with editorials. Editorials are columns written by a member of a publication’s board or editors, and they are meant to represent the view of the publication. While reporting has the main purpose of informing the public, editorials can serve a large number of purposes. But typically editorials aim to persuade an audience on a controversial issue.

Op-eds, on the other hand, are “opposite the editorial” page columns. They began as a way for an author to present an opinion that opposed the one on the editorial board. Note that an op-ed is different than a letter to the editor, which is when someone writes a note to complain about an article, and that note is published. Think of a letter to the editor as an old, more stodgy form of the comments section of an article.

The New York Times produced the first modern op-ed in 1970, and over time, op-eds became a way for people to simply express their opinions in the media. They tend to be written by experts, observers, or someone passionate about a topic, and as media in general becomes more partisan, op-eds have become more and more common.

How to start . The first step for writing an op-ed is to be sure to: Make. An. Argument.

Many op-eds fail because they just summarize key details. But, wrong or right, op-eds need to advance a strong contention. They need to assert something, and the first step is to write down your argument.

Here are some examples:

- I want to write an op-ed on the plague that are drinks that overflow with ice cubes. This op-ed would argue that restaurants serve drinks with too many ice cubes.

- Superman is clearly better than Batman. In this op-ed, I would convince readers why Superman is a better superhero than Batman.

- My op-ed is on lowering the voting age in America. An op-ed on this topic would list reasons why Congress should pass a law to allow those who are 14 years old like me to be able to vote in elections.

How to write. So you have yourself an argument. It’s now time to write the op-ed. When it comes to writing, this guide assumes a decent command of the English language; we’re not going to cover the basics of nouns and verbs. However, keep in mind a few things:

- Blogs, op-eds, and columns are short. Less than 1,000 words. Usually between 500 and 700 words. Many blogs are just a few hundred words, basically a few graphs and a pull quote often does the job.

- Simplicity, logic, and clarity are your best friends when it comes to writing op-eds and blogs. In other words, write like a middle schooler. Use short sentences and clear words. Paragraphs should be less than four sentences. Please take a look at Strunk and White for more information. I used to work with John Podesta, who has written many great op-eds, and he was rumored to have given his staff a copy of Strunk and White on their first day of employment.

- Love yourself topic sentences. The first sentence of each paragraph needs to be strong, and your topic sentences should give an overall idea of what’s to follow. In other words, a reader should be able to grasp your article’s argument by reading the first sentence of each paragraph.

How to make an argument. This guide is not for reporters or news writers. That’s journalism. This guide is for people who make arguments. So keep in mind the following:

- Evidence . This might be obvious, but you need evidence to support your argument. This means data in the forms of published studies, government statistics, and anything that offers cold facts. Stories are good and can support your argument. But try and go beyond a good anecdote.

- Tone . Check out the bloggers and columnists that are in the publications that you’re aiming for, and try to emulate them when it comes to their argumentative tone . Is their tone critical? Humorous? Breezy? Your tone largely hinges on what type of outlet you are writing for, which brings us to…

- Audience . Almost everything in your article — from what type of language you use to your tone — depends on your audience. A piece for a children’s magazine is going to read differently than, say, an op-ed in the Washington Post. The best way to familiarize yourself with your audience is to read pieces that have already been published in the outlet you are writing for, or hoping to write for. Take note of how the author presents her argument and then adjust yours accordingly.

Sidebar: Advice vs Argument. Offering advice in the form of a how-to article — like what you’re reading right now — is different than putting forth an argument in an actual op-ed piece.

That said, advice pieces, like this one by Lifehacker or this one by Hubspot, follow much of the same ABC formula. For instance, advice pieces will still often begin with an attention-grabbing opener and contextualize their subject matter.

However, instead of trying to make an argument in the body of the article, the advice pieces will typically list five to ten ways of “how to do” something. For example, “How to cook chicken quesadillas” or “How to ask someone out on a date.”

The primary purpose of an advice piece is to inform rather than to convince. In other words, advice pieces describe what you could do, while op-ed pieces show us what we should do.

Part II: Dissecting The ABC Approach

Formula. Six steps make up the ABC method, and yes, that means it should be called the ABCDEF method. Either way, here are the steps:

Attention (sometimes called the lede): Here’s your chance to grab the reader’s attention. The opening of an opinion piece should bring the reader into the article quickly. This is also sometimes referred to as the flash or the lede, and there are two types of flash introductions. They are: Option 1. Narrative flash . A narrative flash is a story that brings readers into the article. It should be some sort of narrative hook that grabs attention and entices the reader to delve further into the piece. A brief and descriptive anecdote often works well as a narrative flash. It simultaneously catches the reader’s attention and hints at the weightier argument and evidence yet to come.

When I first started writing for US News, I wrote a flash lede to introduce an article about paddling school children. Here’s that text:

Ben Line didn’t think the assistant principal had the strength or the gumption. But he was wrong. The 13-year-old alleges that the educator hit him twice with a paddle in January, so hard it left scarlet lines across his buttocks. Ben’s crime? He says he talked back to a teacher in class, calling a math problem “dumb.”

Option 2. News flash . Some pieces — especially those tied to the news — can have a lede without a narrative start. Other pieces, including many op-eds, are simply too short to begin with a narrative flash. In either of these instances, using the news flash as your lede is likely your best bet.

If I were writing a news flash lede for the paddling piece, I might start with something as simple as: Congress again is considering legislation to outlaw paddling.

- Billboard (also often called the nut graph): The billboard portion of the lede should do two things:

First, the “billboard” section should make an argument that elevates the stakes and begins to introduce general evidence and context for the argument. So start to introduce some general evidence to support your argument in the nut portion of the lede.

For an example of a nut graph for a longer piece on say, sibling-on-sibling rivalry, consider the following: The Smith sisters exemplify a disturbing trend. Research indicates that violence between siblings—defined as the physical, emotional, or sexual abuse of one sibling by another, ranging from mild to highly violent—is likely more common than child abuse by parents. A new report from the University of Michigan Health System indicates the most violent members of American families are indeed the children. Data suggests that three out of 100 children are considered dangerously violent toward a brother or sister, and nine-year-old Kayla Smith is one of those victims: “My sister used to get mad and hit me every once in a while, but now it happens at least twice a week. She just goes crazy sometimes. She’s broken my nose, kicked out two teeth, and dislocated my shoulder.”

Second, the billboard should begin to lay the framework of the piece and flush out important details—with important story components like Who, What, When, Where, How, Why, etc. A good billboard graph often ends with a quote or call to action. Think of it like this: if someone reads only your “billboard” section, she should be able to grasp your argument and the basic details. If you use a narrative flash lede, then the nut paragraph often starts with something like: They are not alone. So in the padding article, for instance, the nut might have been: “Ben is not alone. In fact, 160,000 students are subject to corporal punishment in U.S. schools each year, according to a 2016 social policy report.”

For another example, here’s a history graph from a recent op-ed by John Podesta that ran in the Washington Post :

“To give some context: On Oct. 7, 2016, WikiLeaks began leaking emails from my personal inbox that had been hacked by Russian intelligence operatives. A few days earlier, Stone — a longtime Republican operative and close confidant of then-candidate Donald Trump — had mysteriously predicted that the organization would reveal damaging information about the Clinton campaign. And weeks before that, he’d even tweeted: ‘Trust me, it will soon [be] Podesta’s time in the barrel.’”

If you’re writing an advice piece, then similar advice applies. A how-to guide for Photoshop, for example, might include recent changes to the program and information on the many ways that Photoshop can be used to edit pictures.

- Demonstrate: In this section, you must offer specific details to support your argument. If writing an op-ed, this section can be three or four paragraphs long. If writing a column, this section can be six or ten paragraphs long. Either way, the section should outline the most compelling evidence to support your thesis. For my paddling article, for instance, I offered this argument paragraph: The problem with corporal punishment, Straus stresses, is that it has lasting effects that include increased aggression and social difficulties. Specifically, Straus studied more than 800 mothers over a period from 1988 to 1992 and found that children who were spanked were more rebellious after four years, even after controlling for their initial behaviors. Groups that advocate for children, like the American Academy of Pediatrics and the National Education Association, oppose the practice in schools for those reasons.

While narrative can be vital when capturing a reader’s attention, it’s equally important to offer hard facts in the evidence section. When demonstrating the details of your argument, be sure to present accurate facts from reputable sources. Studies published in established journals are a good source of evidence, for instance, but blogs with unverified claims are not.

Also, when providing supporting details, you should think about using what the Ancient Greeks called ethos, pathos, and logos. To explain, ethos refers to appeals based on your credibility, that you’re someone worth listening to. For example, if you are arguing why steroids should be banned in baseball, you might talk about how you once used steroids and their terrible impact on your health.

Pathos refers to using evidence that plays to the emotions. For example, if you are trying to show why people should evacuate during hurricanes, you might describe a family who lost their seven-year-old child during a hurricane.

Logos refers to logical statements, typically based on facts and statistics. For example, if you are trying to convince the audience why they should join the military when they are young, provide statistics on their income when they retire and the benefits they receive while in the military.

- Equivocate : You should strengthen your argument by including at least one graph that briefly describes—and then discounts—the strongest counterargument to your point. This is often called the “to be sure” paragraph, and it hedges your bets about the clarity of your piece with phrases such as “to be sure” or “in other words.”Here’s an example from a recent op-ed in Bloomberg: Of course, that doesn’t mean that Hispanics simply change while other Americans stay the same. In his 2017 book “The Other Side of Assimilation: How Immigrants Are Changing American Life,” Jimenez recounts how more established American groups change their culture and broaden their horizons based on their personal relationships with more recently arrived immigrant groups. Assimilation isn’t slavish conformity to white norms, but a two-way process where the U.S. is changed by each new group that arrives.

- Forward : This is where you wrap up your piece. It carries greater impact, though, if you can write an ending that has some oomph to it and really looks forward. So try to provide some parting thoughts and, when appropriate to the topic, draw your readers to look toward the future. If you began with a narrative flash lede, it’s optimal whenever possible to find a way to tie back into that introductory story. It allows you to simultaneously finalize the premise of your argument and neatly conclude your article. In an op-ed about gun violence that ran last year, minister Jeff Blattner looks toward the future and seamlessly ties the end of his piece back to his lede with this simple but effective kicker: If we don’t commit ourselves to solving them together—to seeing one another as part of a bigger “us”—we may reap a whirlwind of ever-widening division. Let Pittsburgh, in its grief, show us the way.

An op-ed needs to advance a strong contention. It needs to assert something, and and the first step is write down your argument.

Part III: The ABCs In Example

Now that we have gone over the basic ABC formula, let’s examine a recent blog item and identify the six ABC steps.

Written by E.A. Crunden, the piece appeared in ThinkProgress and is titled, “ Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke is embroiled in more than one scandal .”

- Attention : “A controversial contract benefiting a small company based in his hometown is only the latest possible corruption scandal linked to Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke…” This opening sentence introduces the most recent news on Zinke while also signaling that other scandals might be discussed in the article.

- Billboard : “On Monday, nonprofit watchdog group the Campaign Legal Center (CLC) accused Zinke’s dormant congressional campaign of dodging rules prohibiting individuals from converting political donations into individual revenue.” The second paragraph adds more information about Zinke’s alleged missteps.

- Context : “Zinke’s other ethical close-calls, as the CLC noted, are plentiful.” This provides some background to the main argument and lets the reader know that Zinke has a long history of questionable ethics, which the author expands upon in the following paragraphs.

- Demonstrate : “As a Montana congressman, Zinke took thousands of dollars in campaign contributions from oil and gas companies, many of whom drill on the same public lands he now oversees…” Here the author gives specific evidence of Zinke’s actions that some believe to be unethical. This fortifies the argument. The following few paragraphs continue in this vein.

- Equivocate : “I had absolutely nothing to do with Whitefish Energy receiving a contract in Puerto Rico,” the interior secretary wrote in a statement on Friday.” In this case, the equivocation appears in the form of a counterargument. The writer goes on to dismiss it by presenting additional clarifying evidence to support his point.

- Forward: “Monday’s complaint comes amid a Special Counsel investigation into Zinke’s spending habits, as well as a separate investigation opened by the Interior Department’s inspector general. Audits into Puerto Rico’s canceled contract with Whitefish Energy Holdings are also ongoing.” These final two sentences “zoom out” from the specifics of the article, showing that the main news item (i.e., Zinke’s poor ethics) will continue to be relevant in the future. These forward-looking sentences also circle back neatly to the point of the flash news lede by reiterating that “Monday’s complaint” is yet another in a growing list against Zinke.

Part IV: Pitching

When it comes to op-eds, most outlets want to review a finished article. In other words, you write the op-ed and then shop it around to different editors. In some cases, the outlet might want a pitch — or brief summary— of the op-ed before you write it.

Either way, you’ll need a short summary, even just a few sentences that describe your argument. Here is an example of the pitch that I wrote that landed me on the front page of the Washington Post’s Outlook section. Note that this pitch is long, but I was aiming for a more feature-like op-ed.

I wanted to pitch a first-person piece looking at Neurocore, the questionable brain-training program that’s funded by Betsy DeVos.

DeVos just got confirmed as Secretary of Education, and for years, she’s been one of the major investors in Neurocore. Located in Michigan and Florida, the company makes some outlandish promises about brain-based training. The firm has argued, for instance, that its neuro-feedback programs can increase a person’s IQ by up to 12 points.

I was going to take Neurocore’s diagnostic program to get a better sense of the company’s claims. As part of the story, I was also going to discuss the research on neuro-feedback, which is pretty weak. Insurance companies are also skeptical, and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan recently refused to reimburse for Neurocore’s treatments. I’d also discuss some of my research in this area and talk about some of the dangers of spreading myths about learning.

There’s been some recent coverage of Neurocore. But the articles have typically focused on the conflict of interest posed by the company since DeVos herself has refused to disinvest. What’s more, no one appears to have written a first-person piece describing the experience of attending one of their brain training diagnostic sessions.

A few bits of advice:

- Newsy. Whenever possible, build off the news. A good way to drum up interest in your piece is to connect it to current events. People naturally are interested in reading op-eds that are linked to recent news pieces — so, an op-ed on Electoral College reform will be more relevant around election season, for instance. It’s often effective to pitch your piece following a major news event. Even better if you can pitch your op-ed in advance; for example, a piece on voter suppression in the United States might be pitched in advance of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. Here’s an article from McGill University that has some advice on this idea.

- Tailor. Again, in this step of the process, it’s worth considering the audience of the publication. For example, if you’re writing in the business section of a newspaper, you’ll want to frame the article around business. If you are writing for a sports magazine, you’ll want to write about topics like “Who is the greatest golfer of all time, Tiger Woods or Jack Nicklaus?”

Also, websites sometimes have information on pitching their editors. Be sure to follow whatever specific advice they give — this will improve your chances of catching an editor’s eye.

Advice pieces describe what you could do, while op-ed pieces show us what we should do.

Part V: FAQs And Tips

I have lots to say. Can I write a 3,000-word op-ed?

Not really. Most blog articles, op-eds, and columns are short. What’s more, your idea is more likely to gain traction if it’s clear and simple. Take the Bible. It can be broken down to a simple idea: Love one another as you love yourself. Or take the Bill of Rights. It can be shortened to: Individuals have protections.

I want to tell a story. Can I do that?

Maybe. If you do, keep it short and reference the story at the top and maybe again at the bottom. But again, the key to an op-ed is that it makes an argument.

What should do before I hit submit?

We could suggest two things:

- Make sure you cite all your sources. Avoid plagiarism of any kind. If you’re in doubt, provide a citation via a link or include endnotes citing your sources.

- Check your facts. The New York Times op-ed columnist Bret Stephens says it this way: “Sweat the small stuff. Read over each sentence—read it aloud—and ask yourself: Is this true? Can I defend every single word of it? Did I get the facts, quotes, dates, and spellings exactly right? Yes, sometimes those spellings are hard: the president of Turkmenistan is Gurbanguly Malikguliyevich Berdymukhammedov. But, believe me, nothing’s worse than having to run a correction.” For more guidance, see Stephen’s list of tips for aspiring op-ed writers .

- Read it out loud. Before I submit something, I’ll read it out loud. It helps me catch typos and other errors. For more on talking out loud as a tool, see this article that I pulled together some time ago.

What’s the difference between a blog article and an op-ed?

A blog article can be about anything such as “What I had for lunch today” or “Why I love Disney World.” An op-ed typically revolves around something in the news and is meant to be persuasive. It typically runs in a news outlet of some kind.

What if no one takes my op-ed?

Be patient. You might need to offer your op-ed to multiple outlets before someone decides to publish it, and you can always tweak the op-ed to make it more news-y, tying the article to something that happened in the news that day or week.

Also, look for ways to improve the op-ed. You might, for instance, focus on changing the “attention” section to make it more creative and interesting or try to improve the context section.

What is the best way to start writing an op-ed?

Before writing, make sure to create an outline. I will often write out my topic sentences and make sure that I’m making a strong, evidence-based argument. Then I’ll focus on a creative way to open my op-ed.

Don’t worry if you get writer’s block while writing the “attention” step. You can always come back and make it more interesting. Really, the most important step is having an outline.

Should I hyperlink?

Yes, include hyperlinks in your articles to provide your readers with easy access to additional information.

–Ulrich Boser

15 thoughts on “How To Write an Op-ed: A Step By Step Guide”

Thanks for this excellent refresher!

I am writing this with the hope that the leasing of the port of Haifa will not come to fruition,It will give the Chinese a strong foothold in the middle east. No longer will the United States 6th fleet have a home away from home..May i remind those who are in command that NO OTHER COUNTRY in the world has helped Israel more than the US.and it would be a slap in the face of our best friend and cause many , many consequences in the future for the state of Israel. I pray to G-D that those in charge will come to their senses and hopefully cancel the agreement. M A, Modiin

Excellent piece of writing ideas, Thanks a lot for sharing these amazing tricks.

INTERESABTE TODA LA INFORMACION

Gracias, Julio!

Good information

So glad you enjoyed it!

Glad it was helpful. Did I miss something in your comment?

Well done, But it’s needs practice!! Hands on!

Write with is one of the most critical steps of the writing process and is probably relevant to the first point. If you want to get your blood pumping and give it your best, you might want to write with passion, and give it all you got. How do you do this? Make sure that you have the right mindset whenever you are writing.

Create a five-paragraph editorial about a topic that matters to you.

Reading this I realized I should get some more information on this subject. I feel like there’s a gap in my knowledge. Anyway, thanks.

Thank you very much for your really helpful tips. I’m currently writing a lesson plan to help students write better opinion pieces and your hands-on approach, if a bit too detailed for my needs, is truly valuable. I hope my students will see it the same way 😉

Thank you for sharing your expertise. Your advice on incorporating storytelling, providing evidence, and addressing counterarguments is invaluable for ensuring the effectiveness and persuasiveness of op-eds.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

More Insights

5 Questions With Neil Heffernan of ASSISTments

Learn how online math platform ASSISTments is closing achievement gaps, aiding teachers, and benefiting science of learning research.

A Breakthrough In Better, Cheaper, And Faster Education R&D

An unprecedented grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation to OpenStax at Rice University will facilitate the education R&D needed to develop new tools for teaching and learning.

5 Questions With WiKIT’s Natalia I. Kucirkova

Evidence of learning is key to the successful development of new edtech tools and platforms. Prof. Natalia I. Kucirkova of WiKIT discusses efforts to leverage the collective expertise of those in the education community to ensure that children worldwide can use technologies that genuinely enhance their learning.

Stay up-to-date by signing up for our weekly newsletter

What Is an Op-Ed Article? Op-Ed Examples, Guidelines, and More

Have you ever wondered the name of those articles in newspapers or online that seem to be more conversational in style than standard news stories?

These are called op-ed articles, and they are an entirely different style and format of writing that is typically found in the opinion section of a newspaper, magazine, or website.

In this article, I’m going to answer the question what is an op-ed article by digging into exactly what an op-ed article is as well as looking at some op-ed examples, how to write an op-ed, and how (and where) to submit an op-ed.

What Is an Op-Ed Article?

Op-ed stands for “opposite the editorial page,” and an op-ed article is an article in which the author states their opinion about a given topic, often with a view to persuade the reader toward their way of thinking.

Despite the “op” in “op-ed” not standing for “opinion,” op-eds are often called opinion pieces because, unlike standard news articles, the authors of op-eds are encouraged to give their opinions on a certain topic, as opposed to simply reporting the news.

Op-eds are sometimes written by a ghostwriter, which means somebody writes the op-ed on behalf of someone else (such as a businessperson or politician), then the intended author makes some tweaks, with the final version being attributed—bylined—to the intended author instead of the ghostwriter.

Anonymous Op-Eds

Op-eds can also be anonymous, although for larger publications, such as the New York Times , Wall Street Journal , and Washington Post , an anonymous op-ed is typically only allowed when the writer’s job (or in extreme cases, their life) would be jeopardized if their name or other distinguishing details were disclosed. In cases when an anonymous op-ed is allowed to go ahead, the author’s true identity is known by the publisher.

Whether or not anonymous op-eds should be allowed to be published comes up for frequent scrutiny, the most recent episode of which being in September 2018 after the New York Times published an anonymous opinion piece by a senior official working in the Trump administration. (In October 2020, former chief of staff in the Department of Homeland Security, Miles Taylor, publicly confirmed that he had authored the article.)

Op-Ed Responses

Often, op-ed articles are written in response to something that is happening in the news at a particular time; such as during a climate change summit or election cycle, or they are written as a response to another op-ed, whether the first opinion piece was published in the same newspaper or, for example, somebody decided to write an op-ed in the New York Times in response to an op-ed that appeared in the Wall Street Journal .

While there is no generalized word limit for an op-ed, most published op-eds run under 1,000 words. The New York Times notes that:

Written essays typically run from 800 to 1,200 words, although we sometimes publish essays that are shorter or longer.

Op-Ed Examples

For an article to be an op-ed it must, as noted above, appear in an opinion column. As many people find themselves reading op-eds after clicking a link online, op-ed columns typically also have the words ‘Opinion’ or ‘Guest Essay’ displayed above or close to the column’s headline.

If you’re looking for op-ed examples, look no further than the opinion pages of three of the largest newspapers in the United States, namely the New York Times , Wall Street Journal , and Washington Post opinion pages (for a longer list, see the How (and Where) to Submit an Op-Ed section below).

The Difference Between Op-Eds and Regular Articles

Some columns that look like a good op-ed article example are in fact lifestyle articles that, while not being timely in relation to the news of the day, aren’t defined as op-ed articles because they are purely factual, with no opinion being given.

Articles I have personally written for the New York Times , New York Observer , Quartz , and similar publications had to be meticulously sourced and fact-checked before publication; and my opinion surrounding any of the topics in question was not taken into consideration, unlike for an op-ed.

That’s not to say you can simply make up facts when writing an op-ed. You can’t have your own opinion about the year Queen Elizabeth II was born (1926), the height of the Empire State Building (1,454 ft.), or the length of the Great Wall of China (21,196 km). Depending on what your op-ed is discussing, you can sprinkle your opinion in around facts, but those facts must be deep-rooted in order for your audience to get on board with your argument—and for a reputable source to choose to print your article.

How to Write an Op-Ed

Of course, knowing what an op-ed is and knowing how to write an op-ed are two different things entirely.

Here are my top five tips on how to write an op-ed:

- Get to the point: The moment a reader (or your potential editor) starts reading your op-ed article they need to know what it is about, and why it matters to them.

- Have a clear thesis: Submitting a meandering opinion column is a surefire way to ensure you do not hear back from the editor. Outline your entire op-ed before sitting down to write, and keep a clear thesis in mind.

- Write what you know: While many factors go into the op-ed selection process, having authority in the topic you’re writing about, as well as a persuasive argument, is required above all else.

- Write for the publication you’re pitching: Don’t use technical phrases if it is a non-technical publication. Look into what they have published on your topic in the past. How can you advance this discussion?

- Stick to the rules: Most op-ed sections list their rules for publication. These often include information on how to source your facts, a well as the house style.

How (and Where) to Submit an Op-Ed

It’s easy to submit an op-ed to either a national or local newspaper, or to a trade publication in your field. Assuming you’ve read my advice on how to write an op-ed above, here are the links you’ll need to submit an op-ed to the following newspapers:

- New York Times

- Wall Street Journal

- Washington Post

- Los Angeles Times

- Houston Chronicle

- Chicago Tribune

- San Francisco Chronicle

- Tampa Bay Times

- Dallas Morning News

- Denver Post

- Seattle Times

If you want to submit an op-ed to your local newspaper or a trade publication, look in their opinion columns for information on how to send in your submission, or search for their name alongside the word “submissions” online.

I hope this article on what an op-ed article is will help you on your journey toward writing and submitting your first op-ed to a major newspaper or publication.

If you’re interested in hearing more from me, be sure to subscribe to my free email newsletter , and if you enjoyed this article, please share it on social media, link to it from your website, or bookmark it so you can come back to it often. ∎

Benjamin Spall

You might also like....

Introducing Acne Club

Nature-Deficit Disorder: What It Is, and How to Overcome It

How to Feel Less Anxious About the Coronavirus (COVID-19)

Writing Studio

How to write an op-ed.

These tips are based on an “ On Writing ” panel hosted by the Writing Studio and the Russell G. Hamilton Graduate Leadership Institute on November 20, 2019 that included Professor of Communications Bonnie Dow, Assistant Vice Chancellor of Strategic Communications Ian Morrison, Professor of History Moses Ochonu, and Associate Professor of Earth and Environmental Science Jonathan Gilligan.

Why Write an Op-Ed in Graduate School?

As our panelists pointed out, writing op-eds can be a useful exercise, even an important piece of academic training.

It can be a way for you to take your research, your expertise, and communicate to the public and make an engagement with people who aren’t in the academic world, regardless of where the op-ed is placed.

Writing an op-ed, in other words, is a way of practicing, or putting your effort into saying, “My work matters.”

Know Your Audience

“Really take the time to think about, where am I trying to place this? Who are their readers? How do they want to hear this? What is going to grab their attention?” – Ian Morrison

As an op-ed writer your audience is twofold: you need to think about both the publisher’s attention—for which you will be competing with thousands of other submissions—as well as the reader’s. For this reason, an attention-grabbing first paragraph, if not first sentence, is paramount.

It also helps to think about the role of opinion pages: as a forum for opinion, they create conversations that live beyond the pages of the publication in which they originally appear. In other words, op-eds seek to amplify the discussion.

Really take the time to think about where you are trying to place the op-ed, who the readers are, what and how do they want to hear this, and what is going to grab their attention. At the same time, aim to be interesting and relevant. You need to address issues in the public conversation.

Organization and Style

“Examples and anecdotes engage readers. Opening with an example, an anecdote, or with a startling statistic works really well at the top of an op-ed.” – Bonnie Dow

Short paragraphs—two to three sentences, maybe four—are a must. If you submit traditional academic paragraphs, you risk having them shortened by the publisher in ways you don’t like. You might end up with something that doesn’t make sense to you. So keep your paragraphs short.

Use structure to build to your point. In other words, make the paragraphs do the work of transitions and previews for you. Instead of saying “first,” “second,” or “third” in op-eds, start a new paragraph when you want to say something.

Use short, punchy, declarative sentences. This will help you stick to the word limit and avoid a situation in which the publisher chops up the piece for you. You absolutely want to maintain control of your own message. Be wary of semicolons or colons; if you need the latter, your sentences are probably too long. Use active rather than passive writing.

Content and Accuracy

“If you’re looking for places to have an impact, look at all the media that you can engage with. The op-ed is one specific thing, and it is one specific writing style, and one specific medium.” –Jonathan Gilligan

Think about your goals and your narrative. Ask yourself, does it fit with other op-eds I’ve read? Can I accomplish my goals using this structure of writing? Remember: don’t under-qualify things. Factual accuracy is incredibly important. If you write an op-ed and you oversimplify, your words are out there permanently.

Avoid giving the wrong impression of too much certainty that comes from blunting nuance or veering close to misrepresentation (even if there is wiggle-room for justification). That’s part of the struggle: strive for simplicity, be punchy, but make sure that you are willing to stand behind exactly what you said the way you said it with your reputation as a scholar.

And remember: Always proofread, proofread, proofread!

- TechBar Support

How to Write an Impactful Op-Ed

by The Writing Workshop | Feb 8, 2024 | Persuasive Writing

What is an op-ed?

An op-ed goes by many names—an editorial, opinion piece, commentary, page op, etc.—but it is, in essence, a piece of writing within the public view that expresses an informed opinion focused on a specific topic or problem. Op-eds are fairly new as a writing style, first coming to prominence in the early 1900s as a way to attract the public back to print news in the age of radio. Today, they serve a similar niche; newspapers face a budget crisis as readership is at an all-time low, and op-eds offer a low-cost solution to providing daily content that engages readers in a way that more traditional journalism simply can’t.

The modern op-ed writer is not restricted by occupation either; professors, politicians, researchers, and professionals use them to take control of the narrative on a given topic rather than entrusting social media and search algorithms to do the job. There is also a rising trend in the sciences to compliment research with op-eds to address limitations in their work that can lead to pervasive misinterpretations.

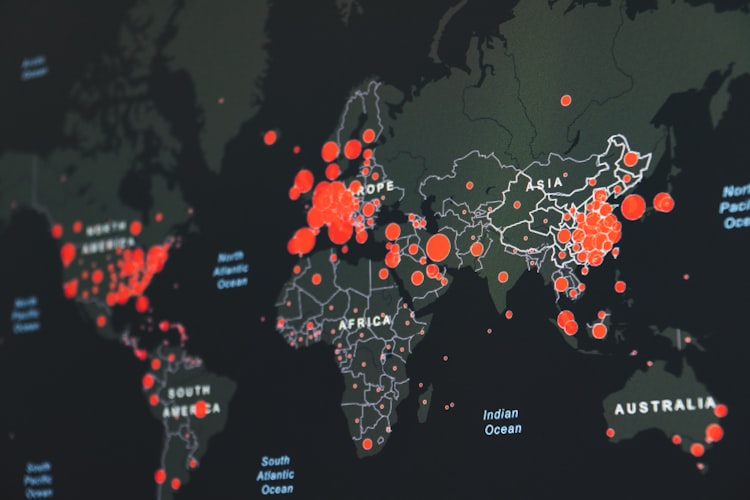

For example, in early 2023, Cochrane, an influential organization that collects databases and reviews research, published an ambiguously worded review of RCT studies on masking and hand washing that led to gross misinterpretations of the study’s conclusions, even by one of its authors . Researchers and epidemiologists, including the editor in chief at Cochrane , were quick to point out that the study did not come to a conclusion due to a lack of evidence alongside glaring inadequacies in the review . Given the mistrust in science that has permeated from Covid-19 misinformation, academics continue to dispel the significance of the article months after its original publication .

Why does this matter? Well, just like in research writing, where you are one piece of a larger puzzle contributing to the cannon of knowledge on a given topic, op-ed writing is about making a small yet meaningful contribution to this cannon using persuasion. Unfortunately, many of the tools used to purvey a greater understanding can also be used to distort and mislead. While there is certainly something to be said of the severity and degree to which misinformation impacts the public in a digital age (in an op-ed, perhaps?), it is just an amplification of the truth’s dependence on the status quo; your job as an op-ed writer is to add nuance to widely held assumptions by offering alternative opinions, evidence, and interpretations.

So where do you begin? Well for one, you need some expertise on the topic you are writing about; persuading your audience to believe something you don’t understand yourself would be both unethical and a poor reflection of your abilities. You will also need to understand who you are writing to and what they care about, so let’s start there!

Identifying your audience

Good writing always has an audience, but writing to a large group of folks, each with their own unique needs and beliefs, can often be difficult. Your job in an op-ed is to speak to the aligned values and attitudes of your audience.

- Do you speak to what is most important to your audience?

- Is there a clear benefit to reading your piece?

- Do you present information in a way that is new and interesting to the audience?

- Does your audience have biases or preconceptions about the issue? Can you manage them?

- How do you want your audience to react to this piece?

- Is the language appropriate?

Successful op-eds also capitalize on what the audience may know (or not) about the topic.

- What does your audience already know about the topic?

- Is there a varying level of knowledge or familiarity with your topic?

- Does your audience “know” because they trust that someone does?

- What is new to your audience?

- Do you present new information in a way that is easy to understand?

- Why does your audience not know this information?

All writers struggle to understand their audiences, but for op-eds, it’s a little easier. Given the popularity of op-eds in most US newspapers, you can look to what other writers do in their pieces to engage readers—just remember that the point of an op-ed is to challenge a prominent belief or interpretation, and if you write only to those who share your views, you will lose the hearts and minds of those open to a critical dialogue on the topic.

For more on understanding your reader’s unique needs, check out our post below!

Choosing a role

Everyone from professional journalists to professors and politicians—including the president—writes op-eds. There are plenty of reasons someone would be compelled to write an op-ed, but we think it’s useful to divide them into three distinct roles, listed below, that a policy professional will find themselves in at one time or another.

The Witness

The Witness offers a firsthand account of the problem, whether they experienced it themselves or witnessed it in action. Witnesses focus on the material and human costs, but the true power of their opinion lies in their testimony, often speaking truth to power and serving up a distinctly human-centered narrative of what’s going on. Witnesses should focus on creating a strong narrative that is representative of the problem and conveys the cost of ignoring it.

The Practitioner

The Practitioner occupies an important space between witness and expert. The practitioner experiences the problem secondhand—through aid or non-profit work, for example—but uses their insider knowledge to further educate their audience on its root causes, often moving from problem identification to a solutions-focused narrative. Practitioners are challenged to create short, effective narratives followed by evidence-based arguments to contextualize their observations; they should lean into their role and the credibility it provides but be cautious in appealing to themselves as an authority in place of evidence.

The Expert can be both a witness and/or practitioner (a practicing epidemiologist, for example), but their power lies in their extensive knowledge of the problem and the landscape in which it occurs. While it may seem easy for the experts, they are plagued with the “curse of knowledge” and challenged to write about complex ideas in way that an average reader will understand. Experts should lean into their extensive knowledge but be careful in presenting too many contingencies, caveats, and abstractions. Experts tend to jump around in their op-eds, which can often disorient a reader, so having a second set of eyes that represents their intended audience will always be helpful.

Once you’ve identified where you fall within this spectrum, it’s time to begin developing your argument.

The nuts and bolts of an op-ed

Structurally, an op-ed can be somewhat free-form, and there will be a lot of variation between different schools of writers (i.e. researchers, academics, journalists, activists, etc.), but a deductive structure is always a great starting point, even if you alter it after your essentials are in place. To start, focus on creating adequate context for your argument in the first paragraph—making sure to provide your reader with the essentials—and then move on to crafting a strong connection between that background information and your argument in the second paragraph. From there, go point by point, keeping in mind that journalists use line breaks more often than academic writers, dividing each piece of evidence along with its analysis into individual paragraphs rather than adjoining them to their topic sentence. For more on deductive structure, read our post below!

Every op-ed should have a clear purpose that can be intuited in the first few paragraphs. However, the central claim of an op-ed often differs from an academic thesis in that it requires some action on your reader’s part. You may want them to consider, reconsider, deny, approve, march, vote, or a whole host of other activities, but your argument should always move toward a call to action. Aside from being persuasive, your piece should also:

Those writing for monthly publications will have a little more flexibility here, but your central claim should have some degree of relation to what is going on right now . Maybe it’s that the problem has finally reached its tipping point, or that some event has made it front and center in the public eye, but whatever it is, it should activate existing knowledge in your audience. Regularly reading the news will be essential to your success in the op-ed space as readers are simply uninterested in rehashing the issues of the past or predictions of the future unless they are pertinent today.

Start with a leading sentence

Traditional journalists often write a setting sentence to start their feature pieces (i.e. “John Doe sits on his front porch looking at his latest bill from the doctor.”), but you have much more flexibility in an op-ed. The goal in your leading sentence should be to entice your audience into reading your piece while providing them with a general sense of the topic or problem. Check out a few examples below (UChicago students have unlimited access to the New York Times via the library page).

- The air pollution in Emma Lockridge’s community in Detroit was often so bad, she had to wear a surgical mask inside her house.

- Tyler Parish thinks of himself as “the last dinosaur.”

- What comes to mind when you think of a mom-and-pop small business: A hardware store? A diner? A family-run clothing store or small-scale supermarket?

Get to the point

Timing is everything in an op-ed. If you present your case for change too early, the reader might not have the background knowledge they need to understand or support it; however, if you wait too long, they may lose interest. Depending on your topic, your point—one main argument per piece being the standard—may come sooner or later, but it should always be clearly stated by the halfway mark.

In this recent piece by Peter Coy on commercial real estate in the New York Times , notice how quickly the author presents his point. He uses the first paragraph to contextualize new information that will be familiar to the audience while attaching the issue to the larger concern of a potential banking crisis, then uses the second paragraph to present his argument (skepticism in the Fed’s approach to inflation as it pertains to commercial real estate). The New York Times has covered domestic inflation on a daily basis, so Coy is both capitalizing on this existing knowledge while encouraging the reader to further invest by presenting nuance and evidence for it. While this piece is heavier on the jargon than we would recommend, it is to be expected when targeting a more specific group.

In contrast, this piece on antitrust law by the editorial board of the Washington Post uses the first few paragraphs to explain a more complex issue that the reader may not be familiar with given the current direction of the FTC. Their main claim—that this is a classic example of antitrust enforcement—comes later because readers may not understand how Google’s ad stack functions nor the alleged monopolistic behavior within that space.

Create a realistic call to action

While a policy maker, organization, or politician may be the one who implements change, be sure to include your audience in the call to action as they will be essential in pushing your decision-maker to action. For example, you might want a senator to support a bill that you think will institute change; in this case, you should think of the voters in their district and how you can make the value of your argument resonate with them through a boycott, petition, or other activist work.

Adding counterpoints to increase credibility

Sometimes it helps to present an argument against your own, which can earn credibility from a skeptical audience or consideration from one that is potentially hostile. A counterpoint assures readers that you’ve considered both sides and wrestled with discordant data or situations that don’t neatly fit the narrative thus far. Basic and fair counterpoints rhetorically position you to make your strongest case before the close. Avoid choosing a weak or widely discredited claim as a counterpoint—often referred to as a “strawman” argument—and instead focus on summarizing the most prominent or pervasive criticism of your main point.

The rebuttal, on the other hand, refutes the counterpoint while introducing a subclaim that directly addresses it. In the case that a previous claim already addresses the counterpoint, do not repeat it verbatim; instead, expand on that point’s scope with additional analysis or evidence to accommodate the counterpoint.

Sign posting language will be a useful tool in writing a compelling and concise counterargument, so make use of language like:

- Some might argue that . . . However . . .

- While it can be said that . . .

- There is a widely held belief that . . . but . . .

Counterarguments (the counterpoint plus the rebuttal) should come at the end of your piece, right before the conclusion. If your piece contains a call to action, make sure to set yourself up for success in your counterargument (a good sign post to add in this case is “that is why . . .”).

Counterarguments can also be the focus of an op-ed when a belief about a given topic has become fallacious or dangerous to public discourse—a phenomena all too common in our current age. Politicians will often use these longform critiques to respond to opponents during election cycles, but in light of controversial bills and rulings within the United States, many have stepped up to the soapbox to dispel common myths and misinformation about a whole host of issues.

We think a recent op-ed on the value of the humanities in higher education by Professor John Keck did this exceptionally. Notice how he uses his first paragraph to build context through timeliness, capitalizing on the recent comments surrounding Texas’s HCR 64, an immigration bill, and their unwarranted criticism of higher education. As he progresses through his critique, he gradually reorients his reader to his home state and the work that he does there, navigating his role of the expert while utilizing the tools of the practitioner to give his narrative a distinctly human focus.

Using a behavioral framework to better persuade your audience

Knowing your target audience’s priorities, values, and concerns will help you craft an argument that is most likely to resonate with them. To better analyze how a given policy narrative might strike our potential readers, we can use insights from social-psychological theories like the Moral Foundations Theory, which was developed by Jonathan Haidt and colleagues to explain how individuals’ moral values are shaped by their cultural, social, and evolutionary contexts. Moral Foundations Theory won’t reveal exactly how your audience will react to your argument for change, but no theory can. At the Writing Workshop, we like to think of these social-psychological theories as additional tools in your kit to help you make quicker and better informed decisions about the arguments, evidence, and language you use within your piece rather than empirical frameworks you can apply with certainty.

If you are interested in acquiring other tools to help you become more persuasive, we recommend checking out the work of Paul Slovic and Daniel Kahneman as well. For further reading on Moral Foundations Theory, check out our post below:

Share this:

Filter articles by:.

- Academic Writing

- Persuasive Writing

- Policy Narratives

- Policy Writing

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

How to write an op-ed or column

Tip sheet on formulating, researching, writing and editing news opinion articles.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by The Journalist's Resource, The Journalist's Resource January 28, 2013

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/home/how-to-write-an-op-ed-or-column/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

The following is reprinted courtesy of Jeffrey Seglin , lecturer in public policy and director of the Harvard Kennedy School Communications Program :

An op-ed piece derives its name from originally having appeared opposite the editorial page in a newspaper. Today, the term is used more widely to represent a column that represents the strong, informed and focused opinion of the writer on an issue of relevance to a targeted audience.

Distinguishing characteristics of an op-ed or column

Partly, a column is defined by where it appears, but it shares some common characteristics:

- Typically, it is short, between 750 and 800 words.

- It has a clearly defined point.

- It has a clearly defined point of view.

- It represents clarity of thinking.

- It contains the strong, distinctive voice of the writer.

Questions to ask yourself when writing an op-ed or column

- Do I have a clear point to make? If so, what is it?

- Who cares? (Writing with a particular audience in mind can inform how you execute your column. Who is it that you are trying to convince? Why are you targeting that specific reader?)

- Is there substance to my argument?

Topic and theme

Every successful op-ed piece or column must have a clearly defined topic and theme.

- The topic is the person, place, issue, incident or thing that is the primary focus of the column. The topic is usually stated in the first paragraph.

- The theme is the big, overarching idea of the column. What’s your point in writing about the chosen topic and why is it important? The theme may appear early in the piece or it may appear later when it may also serve as a turning point into a deeper level of argument.

While columns and op-ed pieces allow writers to include their own voice and express an opinion, to be successful the columns must be grounded in solid research. Research involves acquiring facts, quotations, citations or data from sources and personal observation. Research also allows a reader to include sensory data (touch, taste, smell, sound or sight) into a column. There are two basic methods of research:

- Field research: going to the scene, interviews, legwork; primary materials, observations, and knowledge.

- Library, academic, or internet research: using secondary materials, including graphs, charts, and scholarly articles.

Openings and endings

The first line of an op-ed is crucial. The opening “hook” may grab the reader’s attention with a strong claim, a surprising fact, a metaphor, a mystery, or a counter-intuitive observation that entices the reader into reading more. The opening also briefly lays the foundation for your argument.

Similarly, every good column or op-ed piece needs a strong ending that fulfills some basic requirements. It:

- Echoes or answers introduction.

- Has been foreshadowed by preceding thematic statements.

- Is the last and often most memorable detail.

- Contains a final epiphany or calls the reader to action.

There are two basic types of endings. An “open ending” suggests rather than states a conclusion, while a “closed ending” states rather than suggests a conclusion. The closed ending in which the point of the piece is resolved is by far the most commonly used.

Having a strong voice is critical to a successful column or op-ed piece. Columns are most typically conversational in tone, so you can imagine yourself have a conversation with your reader as you write (a short, focused conversation). But the range of voice used in columns can be wide: contemplative, conversational, descriptive, experienced, informative, informed, introspective, observant, plaintive, reportorial, self-effacing, sophisticated or humorous, among many other possibilities.

Sometimes what voice you use is driven by the publication for which you are writing. A good method of developing your voice is to get in the practice of reading your column or op-ed out loud. Doing so gives you a clear sense of how your piece might sound – what your voice may come off as – to your intended reader.

Revision checklist

Below are some things to remember as you revise your op-ed or column before you submit it for publication. You should always check:

- Coherence and unity.

- Simplicity.

- Voice and tone. Most are conversational; some require an authoritative voice.

- Direct quotations and paraphrasing for accuracy.

- That you properly credit all sources (though formal citations are not necessary).

- The consistency of your opinion throughout your op-ed or column.

Further resources

Below are links to some online resources related to op-ed and column writing:

- The Op-Ed Project is a terrific resource for anyone looking to strengthen their op-ed writing. It provides tips on op-ed writing, suggestions about basic op-ed structure, guidelines on how to pitch op-ed pieces to publications, and information about top outlets that publish op-eds. Started as an effort to increase the number of women op-ed writers, The Op-Ed Project also regularly runs daylong seminars around the country.

- “How to Write an Op-Ed Article,” which was prepared by David Jarmul, Duke’s associate vice president for news and communications, provides great guidelines on how to write a successful op-ed.

- “How to Write Op-Ed Columns,” which was prepared by The Earth Institute at Columbia University, is another useful guide to writing op-eds. It contains a useful list of op-ed guidelines for top-circulation newspapers in the U.S.

- “And Now a Word from Op-Ed,” offers some advice on how to think about and write op-eds from the Op-Ed editor of The New York Times .

Author Jeffrey Seglin is a lecturer in public policy and director of the Harvard Kennedy School Communications Program .

Tags: training

About The Author

The Journalist's Resource

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Tips for Aspiring Op-Ed Writers

By Bret Stephens

- Aug. 25, 2017

As a summertime service for readers of the editorial pages who may wish someday to write for them, here’s a list of things I’ve learned over the years as an editor, op-ed writer and columnist.

1) A wise editor once observed that the easiest decision a reader can make is to stop reading. This means that every sentence has to count in grabbing the reader’s attention, starting with the first. Get to the point: Why does your topic matter? Why should it matter today ? And why should the reader care what you, of all people, have to say about it?

2) The ideal reader of an op-ed is the ordinary subscriber — a person of normal intelligence who will be happy to learn something from you, provided he can readily understand what you’re saying. It is for a broad community of people that you must write, not the handful of fellow experts you seek to impress with high-flown jargon, the intellectual rival you want to put down with a devastating aside or the V.I.P. you aim to flatter with an oleaginous adjective.

3) The purpose of an op-ed is to offer an opinion. It is not a news analysis or a weighing up of alternative views. It requires a clear thesis, backed by rigorously marshaled evidence, in the service of a persuasive argument. Harry Truman once quipped that he wished he could hire only one-handed economists — just to get away from their “on the one hand, on the other” advice. Op-ed pages are for one-handed writers.

4) Authority matters. Readers will look to authors who have standing, either because they have expertise in their field or unique experience of a subject. If you can offer neither on a given topic you should not write about it, however passionate your views may be. Opinion editors are often keen on writers who can provide standing-with-surprise: the well-known environmentalist who supports nuclear power; the right-wing politician who favors transgender rights; the African-American scholar who opposes affirmative action.

5) Younger writers with no particular expertise or name recognition are likelier to get published by following an 80-20 rule: 80 percent new information; 20 percent opinion.

6) An op-ed should never be written in the style of a newspaper column. A columnist is a generalist, often with an idiosyncratic style, who performs for his readers. An op-ed contributor is a specialist who seeks only to inform them.

7) Avoid the passive voice. Write declarative sentences. Delete useless or weasel words such as “apparently,” “understandable” or “indeed.” Project a tone of confidence, which is the middle course between diffidence and bombast.

8) Be proleptic , a word that comes from the Greek for “anticipation.” That is, get the better of the major objection to your argument by raising and answering it in advance. Always offer the other side’s strongest case, not the straw man. Doing so will sharpen your own case and earn the respect of your reader.

9) Sweat the small stuff. Read over each sentence — read it aloud — and ask yourself: Is this true? Can I defend every single word of it? Did I get the facts, quotes, dates and spellings exactly right? Yes, sometimes those spellings are hard: the president of Turkmenistan is Gurbanguly Malikguliyevich Berdymukhammedov. But, believe me, nothing’s worse than having to run a correction.

10) You’re not Proust. Keep your sentences short and your paragraphs tight.

11) A newspaper has a running conversation with its readers. Before pitching an op-ed you should know when the paper last covered that topic, and how your piece will advance the discussion.

12) Kill the clichés. If you want to give the reader an outside the box perspective on how to solve a problem from hell by reimagining the policy toolbox to include stakeholder voices — well, stop right there. Editors notice these sorts of expressions the way French chefs notice slices of Velveeta cheese: repulsive in themselves, and indicative of the mental slop that lies beneath.

13) If you find writing easy, you’re doing it wrong. One useful tip for aspiring writers comes from the film “A River Runs Through It,” in which the character played by Tom Skerritt, a Presbyterian minister with a literary bent, receives essays from his children and instructs them to make each successive draft “half as long.” If you want to write a successful 700-word op-ed, start with a longer draft, then cut and cut again. “The art of writing,” believed the minister, “lay in thrift.”

14) The editor is always right. She’s especially right when she axes the sentences or paragraphs of which you’re most proud. Treat your editor with respect by not second-guessing her judgment, belaboring her with requests for publication decisions or submitting sloppy work in the expectation that she will whip it into shape.

15) I’d wish you luck, but good writing depends on conscious choices, not luck. Make good choices.

I invite you to follow me on Facebook .

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook and Twitter (@NYTopinion) , and sign up for the Opinion Today newsletter .

- How It Works

- All Projects

- Top-Rated Pages

- Scholarship essay writing

- Book report writing

- Admission essay writing

- Dissertation writing

- Essay editing

- MBA essay writing

- Write my essay

- Free sample essays

- Writing blog

Op Ed Essay Made Easy: Example And Topics From Experts

Do you have an op ed essay task but no idea how to go about it? You are not alone because a lot of people get stuck even before starting. Whether the trouble is in picking good op ed essay ideas or do not understand the right format to use, we are here to help.

This post is a comprehensive guide on how to write an op ed essay. Keep reading to find out more about the best op ed essay format and useful writing tips. To cap it all, we have listed the best 60 op ed topics for essay.

Table Of Contents

Op-Ed Essay Definition

How to write a good op ed essay, op ed essay example, writing an op ed essay: a step-by-step guide, top op ed essay writing tips, interesting op ed essay ideas.

Before looking at how to write a good op ed essay, it is crucial to start by answering the question, “What is it?” Traditionally, it is an opinion piece, mainly used in print media, appearing opposite the editorial page (hence the name “op-ed). These are essays done by authors who are not affiliated with the publisher and are used to provide an opinion to provoke discussion and thought among the readers.

Op-ed essays are slightly longer than the common letter to the editor and have become very common in both print and digital media. Because they offer expert opinions, it is important to start by learning how they are done by reading other top op ed essay examples in specific areas. However, most people still find using op ed examples essay not be enough and opt to seek essay writing help.

When writing an op ed essay, perhaps the most important thing is getting the right topic because it shapes the opinion that you will work on. Try to dig deeper into the topic and answer the question, “What is the latest trend about it?”

Like a standard essay, it is crucial to start your work by developing a good essay structure. Here is the most preferred op ed essay format, but you can also develop a different one.

A news hook. Thesis. Argument. 1 st point. 2 nd point. 3 rd point. Address counterarguments Op ed essay conclusion.

This Op ed is based on the article “Trump, and Great Business Ideas for America”. This is an economic review posted by Shiller Robert in the New York Times. The article mainly discuss the ideas that the new president elect of the United States of America, Donald Trump has on the nation. In essence, the people are hopeful that he will transform the nation’s economy since is a leader who has been in business and management for various years. Economists consider that this is an experiment that will prove whether the skills and techniques of a manager can be vital in enhancing the economy of a nation. Therefore, because of his success in business the Americans are expected that the economy will substantially improve. For Donald Trump, it is vital to be keen on the steps that he will take since people are expecting too much from him especially regarding economy.

Classical School

School of thoughts plays a vital role in the today’s economy. In essence, there are several ways in which the school of thoughts is applied mainly to enhance and solve economic challenges. Therefore, it is imperative to inform the members of the public the need to apply economic school of thoughts to enhance the economy. One of the major commonly use economic school of thoughts is the classical tool. The classical school of thought is regarded as the first economic school of thought that was developed by a Scottish economist Adam Smith. Hunt asserts that the main argument of the school is that the best way to enhance economy is to leave the markets alone (2). In this case, it means that the government had a minimal role to play. This means that the classical economic thought advocated for a free market that involves minimal or no rules. Thus, regarding explaining the value of the classical school, the determining factors were cost of production and scarcity. Concerning macro economy, there are self-re adjustment terms that allow the economy to automatically return to full employment.

Neoclassical School of Economics

This is a school of thought that emerged mainly as an improvement of the classical theory of economics. The school is also currently referred to as the marginal revolution. However, as an advancement of the classical school the theory left various aspects. Some of the most common aspects that were dropped include the value theory and the distribution of wealth in the society. As a result, neoclassical approach focuses on the strategies that promote effective allocation of scarce resources in the various markets. In that connection, there is a great emphasis on how various participants in the market such as the customers and producers utilize the function of utility and production. To achieve success in such markets, they must consider factors such as budgets and constraints. This is the main reason the neoclassical theory introduced the mechanism of maximizing utility and it challenge of cost minimization.

In addition to the above, the neoclassical school of thought can be defined as the theory that emphasizes the efficacy of the products and how it affects the market in terms of supply and demand. In essence, it is clear that the markets are based on the customers due to their control of the market forces such as price and demand. This is mainly because the goal of the consumer is utility maximization whereas the role of the goal of the business is to enhance profits. In that connection, there is a great emphasis on how various participants in the market such as the customers and producers utilize the function of utility and production.

The Theorist That Supports the Human Behavior School of Thought

Landreth and Colander confirm that Elton Mayo is the theorist who best supports this school of thought. Various principles are emphasized by the school of thought (10). One of the most important policies is employee motivation. By accepting diversity, managers demonstrate his management skill of motivating the employees to enhance their performance. The second principle of behavioral school of thought is leadership. This can be explained by the fact that managers can enable to adapt to internal changes swiftly. As well, the other principle of the theory is employee development. The management styled established by managers should ensure that employee development supports the people-focused strategy.

In conclusion, it is elemental to note that the economic school of thoughts may vary in one way or another. However, all these schools of thoughts such as the classical thought and the behavioral schools should be employed to enhance economic growth and development. There are various assumptions that are made in the neoclassical school of thought. One of the major assumption is that the decisions that are made are usually rational due to the availability of completed information about the product and service. The second assumption is that customers compare the available products and services in the market with the primary objective of making effective deceived based on utility. The third and most crucial assumption of the neoclassical economic school is that the primary objective of business is to maximize on profit making. On the contrary, customer’s main objective is to have improved satisfaction while using the service or product. Therefore, as the new president elect of the United States of America takes office he must ensure that the right polices are implemented to enhance economy. Otherwise, improving US economy might be a great challenge to overcome.

After developing the preferred structure for your essay, it is time to write a high-quality piece to impress readers. It might be a great idea to closely check another top op-ed essay example to learn how different components are put through.

- Develop a News Hook

Because an op ed essay is designed for the media, it is crucial to target a trending topic in the local, national, or global headlines. The first few sentences should also grab the reader’s attention, making him/her want to read more. During the just-concluded presidential elections, some topics revolving around the violence on the capitol, the American voting system, and the policy shift between outgoing President Trump and incoming President Joe Biden, would have been excellent.

- Tune Your Op Ed Essay to Match the Targeted Audience

If you read a high-rated op ed essay sample, one of the most notable things is the focus on a specific audience. For example, local print media might be targeted at providing insights on how wearing face masks affect the spread of COVID-19. So, it will be a great idea to try and understand the audience.

- Understand the Targeted Publication

As we have mentioned, op ed essays are written pieces of opinion, but they must follow the rules and guidelines of the targeted media. This means that although you might have a lengthy piece, it has to be cut to size to fit the recommended number of words for the respective media. Other attributes include a sense of style, level, image size and font.

- Back-Up Your Arguments with Facts

While it is true that you are writing a personal opinion, it is paramount to ensure it is based on facts. Once you bring out key arguments, try to incorporate data and statistics to reinforce them. Go ahead and use historical facts to bolster the case. Counterarguments can also help you to sound more professional and avoid bias.

- Use the O p Ed Essay Conclusion to Call Readers to Action

After articulating all the points in your essay, you should not leave readers hanging. Well, if you were discussing a very serious issue, be it the COVID-19 vaccine or the danger of the latest video games, the conclusion should be used to call readers to action. For example, you can ask people to go and get the vaccine, select non-violent games, speak against school bullying, or other actions.

The following op ed essay writing tips will come in handy to help you to stay focused, sharpen your skills, and craft top-notch work.