- Presentation Guru , Public Speaking Resources

Free Presentation Skills Assessment

- October 14, 2021

Jim Harvey , my co-founder of Presentation Guru , and I have been developing a comprehensive questionnaire to help people assess their level of skill when it comes to presentation skills and public speaking. We could not find any questionnaire or tool that enabled people to do so in a simple, but meaningful way.

Jim and I have developed a competency framework that focuses on the critical aspects of presenting, from developing a message to structuring a presentation to delivering that presentation. The questionnaire is based on our competency framework. You can start the questionnaire by clicking on the button below, or first read about the competency framework.

Fit, Focus, Finesse: A Competency Framework

We developed the competency framework around three things that all great speakers do.

- They make sure that the message fits the audience. The message is relevant to, and of value for, the audience on the particular occasion.

- They focus on the most important things related to the message and the audience. The message is structured, logical and to the point.

- They deliver that message with finesse . They make the speech or presentation interesting, engaging and memorable.

Each of the three competencies is broken down into smaller elements related to skill, knowledge, attitude and practice. We believe that each of these elements is an important molecule of excellent public speaking DNA. We then set out positive and negative indicators with regard to each element.

Of course, it rare to come across anyone who possesses all of the skills at the highest level; most of us will have specific strengths and specific areas for improvement. But having a mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive set of competencies gives each of us the chance to build on our strengths and improve our weaknesses.

THE QUESTIONNAIRE

The questionnaire is based on the competencies above. The answers to the questionnaire will allow an assessment of a person’s skills and knowledge against these competencies. Both strengths and specific areas for improvement will be identified. Upon completion of the questionnaire, you will receive a tailored report that details your strengths and areas for development. You will also receive learning resources and ideas for how you can improve, whatever your level of speaking.

We are now in the testing phase. We need people to complete the questionnaire to help us improve it and validate it. You can complete the questionnaire and get your tailored report for free. To do so, click the button below.

Like this article?

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Please enter an answer in digits: twenty − eight =

Testimonials

John delivered a keynote address about the importance of public speaking to 80 senior members of Gore’s Medical Device Europe team at an important sales event. He was informative, engaging and inspirational. Everyone was motivated to improve their public speaking skills. Following his keynote, John has led public speaking workshops for Gore in Barcelona and Munich. He is an outstanding speaker who thinks carefully about the needs of his audience well before he steps on stage.

Karsta Goetze

TA Leader, Gore and Associates

I first got in touch with John while preparing to speak at TED Global about my work on ProtonMail. John helped me to sharpen the presentation and get on point faster, making the talk more focused and impactful. My speech was very well received, has since reached almost 1.8 million people and was successful in explaining a complex subject (email encryption) to a general audience.

CEO, Proton Technologies

John gave the opening keynote on the second day of our unit’s recent offsite in Geneva, addressing an audience of 100+ attendees with a wealth of tips and techniques to deliver powerful, memorable presentations. I applied some of these techniques the very next week in an internal presentation, and I’ve been asked to give that presentation again to senior management, which has NEVER happened before. John is one of the greatest speakers I know and I can recommend his services without reservation.

David Lindelöf

Senior Data Scientist, Expedia Group

After a morning of team building activities using improvisation as the conduit, John came on stage to close the staff event which was organised in Chamonix, France. His energy and presence were immediately felt by all the members of staff. The work put into the preparation of his speech was evident and by sharing some his own stories, he was able to conduct a closing inspirational speech which was relevant, powerful and impactful for all at IRU. The whole team left feeling engaged and motivated to tackle the 2019 objectives ahead. Thank you, John.

Umberto de Pretto

Secretary General, World Road Transport Organization

I was expecting a few speaking tips and tricks and a few fun exercises, but you went above and beyond – and sideways. You taught me to stand tall. You taught me to anchor myself. You taught me to breathe. You taught me to open up. You taught me to look people in the eye. You taught me to tell the truth. You taught me to walk a mile in someone else’s shoes. I got more than I bargained for in the best possible way.

Thuy Khoc-Bilon

World Cancer Day Campaign Manager, Union for International Cancer Control

John gave a brilliant presentation on public speaking during the UN EMERGE programme in Geneva (a two days workshop on leadership development for a group of female staff members working in the UN organizations in Geneva). His talk was inspirational and practical, thanks to the many techniques and tips he shared with the audience. His teaching can dramatically change our public speaking performance and enable us as presenters to have a real and powerful impact. Thank you, John, for your great contribution!

HR Specialist, World Health Organization

John is a genuine communication innovator. His seminars on gamification of public speaking learning and his interactive Rhetoric game at our conference set the tone for change and improvement in our organisation. The quality of his input, the impact he made with his audience and his effortlessly engaging style made it easy to get on board with his core messages and won over some delegates who were extremely skeptical as to the efficacy of games for learning. I simply cannot recommend him highly enough.

Thomas Scott

National Education Director, Association of Speakers Clubs UK

John joined our Global Sales Meeting in Segovia, Spain and we all participated in his "Improv(e) your Work!" session. I say “all” because it really was all interactive, participatory, learning and enjoyable. The session surprised everybody and was a fresh-air activity that brought a lot of self-reflection and insights to improve trust and confidence in each other inside our team. It´s all about communication and a good manner of speaking!"

General Manager Europe, Hayward Industries

Thank you very much for the excellent presentation skills session. The feedback I received was very positive. Everyone enjoyed the good mix of listening to your speech, co-developing a concrete take-away and the personal learning experience. We all feel more devoted to the task ahead, more able to succeed and an elevated team spirit. Delivering this in a short time, both in session and in preparation, is outstanding!

Henning Dehler

CFO European Dairy Supply Chain & Operations, Danone

Thanks to John’s excellent workshop, I have learned many important tips and techniques to become an effective public speaker. John is a fantastic speaker and teacher, with extensive knowledge of the field. His workshop was a great experience and has proven extremely useful for me in my professional and personal life.

Eric Thuillard

Senior Sales Manager, Sunrise Communications

John’s presentation skills training was a terrific investment of my time. I increased my skills in this important area and feel more comfortable when speaking to an audience. John provided the right mix between theory and practice.

Diego Brait

Director of the Jura Region, BKW Energie AG

Be BOLD. Those two words got stuck in my head and in the heads of all those ADP leaders and associates that had the privilege to see John on stage. He was our keynote speaker at our annual convention in Barcelona, and his message still remains! John puts his heart in every word. Few speakers are so credible, humble and yet super strong with large audiences!

Guadalupe Garcia

Senior Director and Talent Partner, ADP International

Evaluating Business Presentations: A Six Point Presenter Skills Assessment Checklist

Posted by Belinda Huckle | On April 18, 2024 | In Presentation Training, Tips & Advice

In this Article...quick links

1. Ability to analyse an audience effectively and tailor the message accordingly

2. ability to develop a clear, well-structured presentation/pitch that is compelling and persuasive, 3. ability to connect with and maintain the engagement of the audience, 4. ability to prepare effective slides that support and strengthen the clarity of the message, 5. ability to appear confident, natural and in control, 6. ability to summarise and close a presentation to achieve the required/desired outcome, effective presentation skills are essential to growth, and follow us on social media for some more great presentation tips:, don’t forget to download our presenter skills assessment form.

For many business people, speaking in front of clients, customers, their bosses or even their own large team is not a skill that comes naturally. So it’s likely that within your organisation, and indeed within your own team, you’ll find varying levels of presenting ability. Without an objective way to assess the presenter skills needed to make a good presentation, convincing someone that presentation coaching could enhance their job performance (benefiting your business), boost their promotion prospects (benefiting their career) and significantly increase their self confidence (benefiting their broader life choices) becomes more challenging.

So, how do you evaluate the presenting skills of your people to find out, objectively, where the skill gaps lie? Well, you work out your presentation skills evaluation criteria and then measure/assess your people against them.

To help you, in this article we’re sharing the six crucial questions we believe you need to ask to not only make a professional assessment of your people’s presenting skills, but to showcase what makes a great presentation. We use them in our six-point Presenter Skills Assessment checklist ( which we’re giving away as a free download at the end of this blog post ). The answers to these questions will allow you to identify the presenter skills strengths and weaknesses (i.e. skills development opportunities) of anyone in your team or organisation, from the Managing Director down. You can then put presenter skills training or coaching in place so that everyone who needs it can learn the skills to deliver business presentations face-to-face, or online with confidence, impact and purpose.

Read on to discover what makes a great presentation and how to evaluate a presenter using our six-point Presenter Skills Assessment criteria so you can make a professional judgement of your people’s presenting skills.

If you ask most people what makes a great presentation, they will likely comment on tangible things like structure, content, delivery and slides. While these are all critical aspects of a great presentation, a more fundamental and crucial part is often overlooked – understanding your audience . So, when you watch people in your organisation or team present, look for clues to see whether they really understand their audience and the particular situation they are currently in, such as:

- Is their content tight, tailored and relevant, or just generic?

- Is the information pitched at the right level?

- Is there a clear ‘What’s In It For Them’?

- Are they using language and terminology that reflects how their audience talk?

- Have they addressed all of the pain points adequately?

- Is the audience focused and engaged, or do they seem distracted?

For your people, getting to know their audience, and more importantly, understanding them, should always be the first step in pulling together a presentation. Comprehending the challenges, existing knowledge and level of detail the audience expects lays the foundation of a winning presentation. From there, the content can be structured to get the presenter’s message across in the most persuasive way, and the delivery tuned to best engage those listening.

Flow and structure are both important elements in a presentation as both impact the effectiveness of the message and are essential components in understanding what makes a good presentation and what makes a good speech. When analysing this aspect of your people’s presentations look for a clear, easy to follow agenda, and related narrative, which is logical and persuasive.

Things to look for include:

- Did the presentation ‘tell a story’ with a clear purpose at the start, defined chapters throughout and a strong close?

- Were transitions smooth between the ‘chapters’ of the presentation?

- Were visual aids, handouts or audience involvement techniques used where needed?

- Were the challenges, solutions and potential risks of any argument defined clearly for the audience?

- Were the benefits and potential ROI quantified/explained thoroughly?

- Did the presentation end with a clear destination/call to action or the next steps?

For the message to stick and the audience to walk away with relevant information they are willing to act on, the presentation should flow seamlessly through each part, building momentum and interest along the way. If not, the information can lose impact and the presentation its direction. Then the audience may not feel equipped, inspired or compelled to implement the takeaways.

Connecting with your audience and keeping them engaged throughout can really be the difference between giving a great presentation and one that falls flat. This is no easy feat but is certainly a skill that can be learned. To do it well, your team need a good understanding of the audience (as mentioned above) to ensure the content is on target. Ask yourself, did they cover what’s relevant and leave out what isn’t?

Delivery is important here too. This includes being able to build a natural rapport with the audience, speaking in a confident, conversational tone, and using expressive vocals, body language and gestures to bring the message to life. On top of this, the slides need to be clear, engaging and add interest to the narrative. Which leads us to point 4…

It’s not uncommon for slides to be used first and foremost as visual prompts for the speaker. While they can be used for this purpose, the first priority of a slide (or any visual aid) should always be to support and strengthen the clarity of the message. For example, in the case of complex topics, slides should be used to visualise data , reinforcing and amplifying your message. This ensures that your slides are used to aid understanding, rather than merely prompting the speaker.

The main problem we see with people’s slides is that they are bloated with information, hard to read, distracting or unclear in their meaning.

The best slides are visually impactful, with graphics, graphs or images instead of lines and lines of text or bullet points. The last thing you want is your audience to be focused on deciphering the multiple lines of text. Instead your slides should be clear in their message and add reinforcement to the argument or story that is being shared. How true is this of your people’s slides?

Most people find speaking in front of an audience (both small and large) at least a little confronting. However, for some, the nerves and anxiety they feel can distract from their presentation and the impact of their message. If members of your team lack confidence, both in their ideas and in themselves, it will create awkwardness and undermine their credibility and authority. This can crush a presenter and their reputation.

This is something that you will very easily pick up on, but the good news is that it is definitely an area that can be improved through training and practice. Giving your team the tools and training they need to become more confident and influential presenters can deliver amazing results, which is really rewarding for both the individual and the organisation.

No matter how well a presentation goes, the closing statement can still make or break it. It’s a good idea to include a recap on the main points as well as a clear call to action which outlines what is required to achieve the desired outcome.

In assessing your people’s ability to do this, you can ask the following questions:

- Did they summarise the key points clearly and concisely?

- Were the next steps outlined in a way that seems achievable?

- What was the feeling in the room at the close? Were people inspired, motivated, convinced? Or were they flat, disinterested, not persuaded?

Closing a presentation with a well-rounded overview and achievable action plan should leave the audience with a sense that they have gained something out of the presentation and have all that they need to take the next steps to overcome their problem or make something happen.

It’s widely accepted that effective communication is a critical skill in business today. On top of this, if you can develop a team of confident presenters, you and they will experience countless opportunities for growth and success.

Once you’ve identified where the skill gaps lie, you can provide targeted training to address it. Whether it’s feeling confident presenting to your leadership team or answering unfielded questions , understanding their strengths and weaknesses in presenting will only boost their presenting skills. This then creates an ideal environment for collaboration and innovation, as each individual is confident to share their ideas. They can also clearly and persuasively share the key messaging of the business on a wider scale – and they and the business will experience dramatic results.

Tailored Training to Fill Your Presentation Skill Gaps

If you’re looking to build the presentation skills of your team through personalised training or coaching that is tailored to your business, we can help. For nearly 20 years we have been Australia’s Business Presentation Skills Experts , training & coaching thousands of people in an A-Z of global blue-chip organisations. All our programs incorporate personalised feedback, advice and guidance to take business presenters further. To find out more, click on one of the buttons below:

- Work Email Address * Please enter your email address and then click ‘download’ below

Written By Belinda Huckle

Co-Founder & Managing Director

Belinda is the Co-Founder and Managing Director of SecondNature International. With a determination to drive a paradigm shift in the delivery of presentation skills training both In-Person and Online, she is a strong advocate of a more personal and sustainable presentation skills training methodology.

Belinda believes that people don’t have to change who they are to be the presenter they want to be. So she developed a coaching approach that harnesses people’s unique personality to build their own authentic presentation style and personal brand.

She has helped to transform the presentation skills of people around the world in an A-Z of organisations including Amazon, BBC, Brother, BT, CocaCola, DHL, EE, ESRI, IpsosMORI, Heineken, MARS Inc., Moody’s, Moonpig, Nationwide, Pfizer, Publicis Groupe, Roche, Savills, Triumph and Walmart – to name just a few.

A total commitment to quality, service, your people and you.

Presentation Skills Assessment Scale

The presentation skills assessment scale is a tool used to measure an individual's proficiency in giving presentations. the scores are then used to give an overall rating of the speaker's presentation skills. .

2 minutes to complete

Eligibility

General eligibility to complete the Presentation Skills Assessment Scale is being at least 18 years of age, being able to understand and communicate in English, having basic computer skills, and possessing the capability to complete the assessment.

Questions for Presentation Skills Assessment Scale

I have a clear idea of how to plan a presentation

I develop professionally engaging slides

I manage nervousness before hand

I build rapport with the audience

I deliver well paced presentation (e.g pace of speech, amount of information)

I deliver with well-modulated voice

I practice presentation beforehand

I present spontaneously rather than read or memorized

I master the use of technology during presentation

I deal with questions arised during presentation

Forms Similar to Presentation Skills Assessment Scale

- Presentation Skills Evaluation Form

- Presentation Skills Self-Assessment Form

- Presentation Skills Assessment Checklist

- Presentation Skills Questionnaire

- Presentation Skills Rating Scale

Here are some FAQs and additional information on Presentation Skills Assessment Scale

What is the presentation skills assessment scale, the presentation skills assessment scale is an assessment tool that provides feedback on an individual's presentation skills. it is designed to measure an individual's self-awareness of their presentation abilities, as well as their ability to communicate effectively in a professional setting., how is the presentation skills assessment scale scored, the score for the presentation skills assessment scale is based on an individual's performance. the overall score is then calculated by taking into account the weighted scores of each questions, what is the difference between the presentation skills assessment scale and other forms of presentation assessment, the presentation skills assessment scale is unique in that it takes into account an individual's self-awareness and ability to communicate effectively in a professional setting. other forms of assessment often focus only on the technical aspects of presentation, want to use this template, loved by people at home and at work.

What's next? Try out templates like Presentation Skills Assessment Scale

1000+ templates, 50+ categories.

Want to create secure online forms and surveys?

Join blocksurvey..

Linda DeLuca

| Poking brains since 2007

Presentation Skills Self Assessment

This assessment is designed to help you identify areas of strength and opportunity for growth. It is also valuable for selecting the right course of action either on your own or with your coach.

The Quick 10

This is the kick-start 10 item assessment to get you started in identifying areas that you are strong, and areas you want to strengthen with experiential learning, research, and tips and tools from PresentationYOU.

Kick-Start Assessment

Use the following 10 factors of effective presentations (and meetings) to get a sense of your skill level. This will get you started in determining your strengths and areas for learning.

Circle the appropriate skill level for each of the 10 statements. Each statement should have only one level circled.

- Basic Skills – still have much to learn

- Good Skills – improving but can learn more

- Great Skills – ready to begin fine tuning

Add the number of circled items in each column to determine your totals. You should have a number from 1 to 10 for each: Basic , Good , and Great . The total of all three columns will equal 10. The column with the highest number is your overall assessment level. For example if you have: Basic 3 / Good 5 / Great 2, your overall assessment is ‘Good’ presentation skills.

Take Action Toward ‘Great’

Now that you have an idea of your current skill level, it’s time to take action to move you from a good presenter to a great presenter.

Any items in which you did not select Great as your skill level is an opportunity to explore.

- Wander through the tools and tips articles under How to Communicate

Ready to Dig Deeper? Schedule a call

Share this:, take action.

- Schedule a call

Recent Posts

- Progress over Perfect

- Let go of overwhelm

- In the company of greatness.

- Curiosity over judgement.

- GOALS WITHOUT END

- Books by Linda

- Speaker Coaching

- Mentor Coaching

- Remote Worker Workshops

- The Archives

- HOW TO COMMUNICATE

- HOW TO WORK – ANYWHERE

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Presentation Skills

29 Resources

Giving presentations can be a daunting task for even the most experienced public speaker. Assess and develop your presentation skills using practical knowledge and tips, designed to help you prepare for, deliver and evaluate great presentations.

Explore Presentation Skills topics

Get 30% off your first year of Mind Tools

Great teams begin with empowered leaders. Our tools and resources offer the support to let you flourish into leadership. Join today!

Self-Assessment

How Good Are Your Presentation Skills?

Understanding Your Impact

Infographic

10 Common Presentation Mistakes Infographic

Infographic Transcript

Visual Aids Checklist

Ensure That the Visual Aids You Choose to Use in Your Presentations Are Fit for Purpose

Managing Presentation Nerves

How to Calm Your Stage Fright

Creating Effective Presentation Visuals

Connecting People With Your Message

Expert Interviews

The Art of Public Speaking

With Professor Steve Lucas

Even Better Presentations

Great presentations.

Giving Presentations on a Web Conferencing Platform

Presenting With Confidence

With Cordelia Ditton

4 Steps for Conquering Presentation Nerves

Banish Your Stage Fright

How to Guides

Taking Questions After a Presentation

A Process for Answering the Audience

Crafting an Elevator Pitch

Introducing Your Company Quickly and Compellingly

Could You Say a Few Words?

A Four-Step Strategy for Impromptu Speaking

Effective Presentations

Learn How to Present Like a Pro

Better Public Speaking

Becoming a Confident, Compelling Speaker

Speaking to an Audience

Communicate Complex Ideas Successfully

5 Funky Presentation Techniques Infographic

The nervous presenter's survival guide.

Overcoming Seven Common Presentation Fears

How to Deliver Great Presentations

Presenting Like a Pro

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Latest Updates

Starting a New Job

The Role of a Facilitator

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Decision-making mistakes and how to avoid them.

Explore some common decision-making mistakes and how to avoid them with this Skillbook

Using Decision Trees

What decision trees are, and how to use them to weigh up your options

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Fiedler's contingency model.

Matching Leadership Style to a Situation

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

Presentation Guru

The presentation guru presentation skills questionnaire – how do you rate.

Presentation Guru has been developing a presentation skills questionnaire to help people (whatever their experience as presenters) assess their current ability in this life-changing skill.

We built the questionnaire (and the competency framework behind it) because there wasn’t one t hat we believed in available anywhere else in the world. We have built it to help people in every country and culture build their confidence and skills in public speaking.

The questionnaire (now in its Beta testing phase of development) will help you identify your core strengths as a presenter and your FREE, personalised report will give you specific advice on how to build your confidence and practical ability in this life-changing skill, whether you’re just starting out on your journey as a presenter or are a seasoned expert.

The questionnaire has been developed to UK British Psychological Society standard by John Zimmer and Jim Harvey of Presentation Guru, with the expert help of Jane ArthurMcGuire . Jane is a UK-based occupational psychologist, specialising in psychometric test design who helped make the questionnaire accurate and easy to use.

What you need to do

In case you missed it, the questionnaire is absolutely FREE! There is nothing to pay. All you need to do is click on the link below, sign up and off you go.

The questionnaire will only take about 20 minutes to complete. Once you’ve completed it you will receive a written report detailing your strengths, weaknesses and development needs as a public speaker.

Your data is governed and protected by our data protection policy .

On completing the questionnaire

Once you’ve completed the questionnaire and submitted it, you will receive an email with your personalised skills assessment and a development plan with FREE learning resources for your future development. The development needs will be linked to suggested activities, articles and further learning resources relating to that specific competence.

- Latest Posts

+Jim Harvey

Latest posts by jim harvey ( see all ).

- How to get over ‘Impostor Syndrome’ when you’re presenting - 6th January 2024

- Powerpoint Zoom Summary for interactive presentations – everything you need to know - 19th November 2023

- Sharpen your presentation skills while you work – 3 great audiobooks for FREE - 29th October 2023

- Death by PowerPoint? Why not try The Better Deck Deck? - 31st October 2021

- The Presentation Guru Presentation Skills Questionnaire – How Do YOU Rate? - 13th October 2021

Varsha Pandey

30th October 2021 at 7:04 pm

really great information shared here.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Follow The Guru

Join our Mailing List

Join our mailing list to get monthly updates and your FREE copy of A Guide for Everyday Business Presentations

The Only PowerPoint Templates You’ll Ever Need

Anyone who has a story to tell follows the same three-act story structure to...

How to get over ‘Impostor Syndrome’ when you’re presenting

Everybody with a soul feels like an impostor sometimes. Even really confident and experienced...

Presentation Skills Assessment

- Presentation Courses

- Presentation Assessment

This 16 question assessment tool surveys participants’ current level of proficiency in the area of presentation and public speaking skills.

Individual participants’ responses will be used to build a report that provides management with data for identifying gaps, planning training, and targeting coaching activities to improve presentation skills and enhance the organization’s image.

Please note our site uses cookies to improve the user experience and to track site usage. By using our website, you agree to our privacy policy

- Eviction Notice Forms

- Power of Attorney Forms Forms

- Bill of Sale (Purchase Agreement) Forms

- Lease Agreement Forms

- Rental Application Forms

- Living Will Forms Forms

- Recommendation Letters Forms

- Resignation Letters Forms

- Release of Liability Agreement Forms

- Promissory Note Forms

- LLC Operating Agreement Forms

- Deed of Sale Forms

- Consent Form Forms

- Support Affidavit Forms

- Paternity Affidavit Forms

- Marital Affidavit Forms

- Financial Affidavit Forms

- Residential Affidavit Forms

- Affidavit of Identity Forms

- Affidavit of Title Forms

- Employment Affidavit Forms

- Affidavit of Loss Forms

- Gift Affidavit Forms

- Small Estate Affidavit Forms

- Service Affidavit Forms

- Heirship Affidavit Forms

- Survivorship Affidavit Forms

- Desistance Affidavit Forms

- Discrepancy Affidavit Forms

- Guardianship Affidavit Forms

- Undertaking Affidavit Forms

- General Affidavit Forms

- Affidavit of Death Forms

- Evaluation Forms

Presentation Evaluation Form

Sample Oral Presentation Evaluation Forms - 7+ Free Documents in ...

Presentation evaluation form sample - 8+ free documents in word ..., 7+ oral presentation evaluation form samples - free sample ....

Download Presentation Evaluation Form Bundle

What is Presentation Evaluation Form?

A Presentation Evaluation Form is a structured tool designed for assessing and providing feedback on presentations. It systematically captures the effectiveness, content clarity, speaker’s delivery, and overall impact of a presentation. This form serves as a critical resource in educational settings, workplaces, and conferences, enabling presenters to refine their skills based on constructive feedback. Simple to understand yet comprehensive, this form bridges the gap between presenter effort and audience perception, facilitating a pathway for growth and improvement.

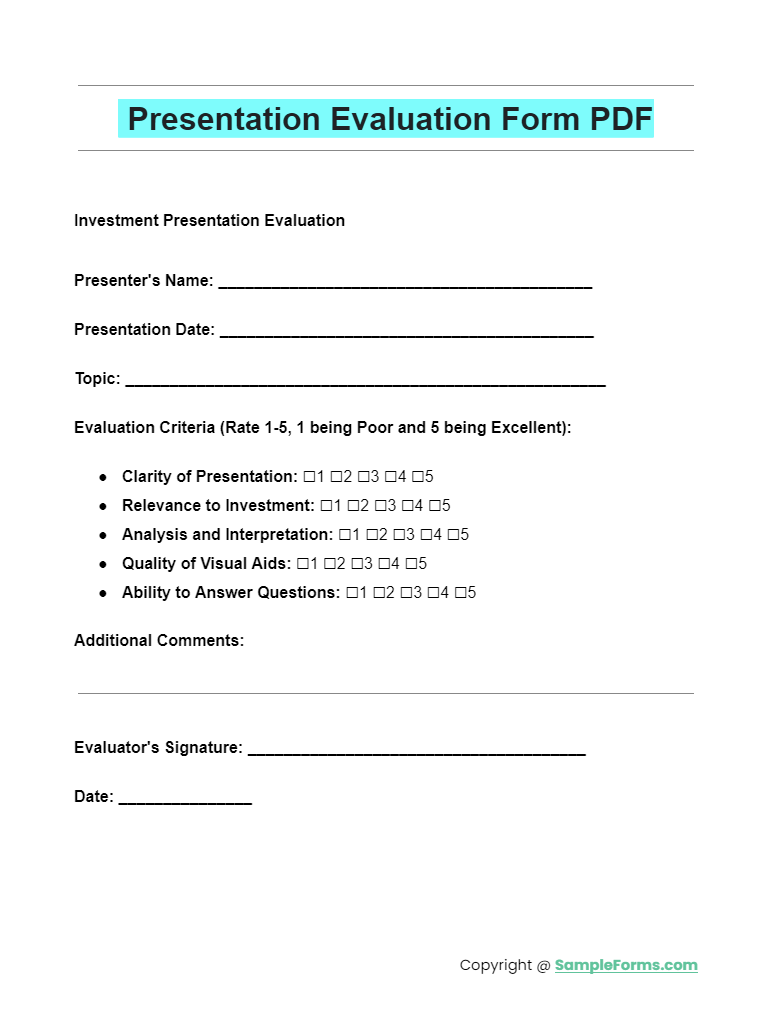

Presentation Evaluation Format

Title: investment presentation evaluation, section 1: presenter information, section 2: evaluation criteria.

- Clarity and Coherence:

- Depth of Content:

- Delivery and Communication:

- Engagement and Interaction:

- Use of Supporting Materials (Data, Charts, Visuals):

Section 3: Overall Rating

- Satisfactory

- Needs Improvement

Section 4: Comments for Improvement

- Open-ended section for specific feedback and suggestions.

Section 5: Evaluator Details

Presentation evaluation form pdf, word, google docs.

PDF Word Google Docs

Explore the essential tool for assessing presentations with our Presentation Evaluation Form PDF. Designed for clarity and effectiveness, this form aids in pinpointing areas of strength and improvement. It seamlessly integrates with the Employee Evaluation Form , ensuring comprehensive feedback and developmental insights for professionals aiming to enhance their presentation skills. You should also take a look at our Peer Evaluation Form

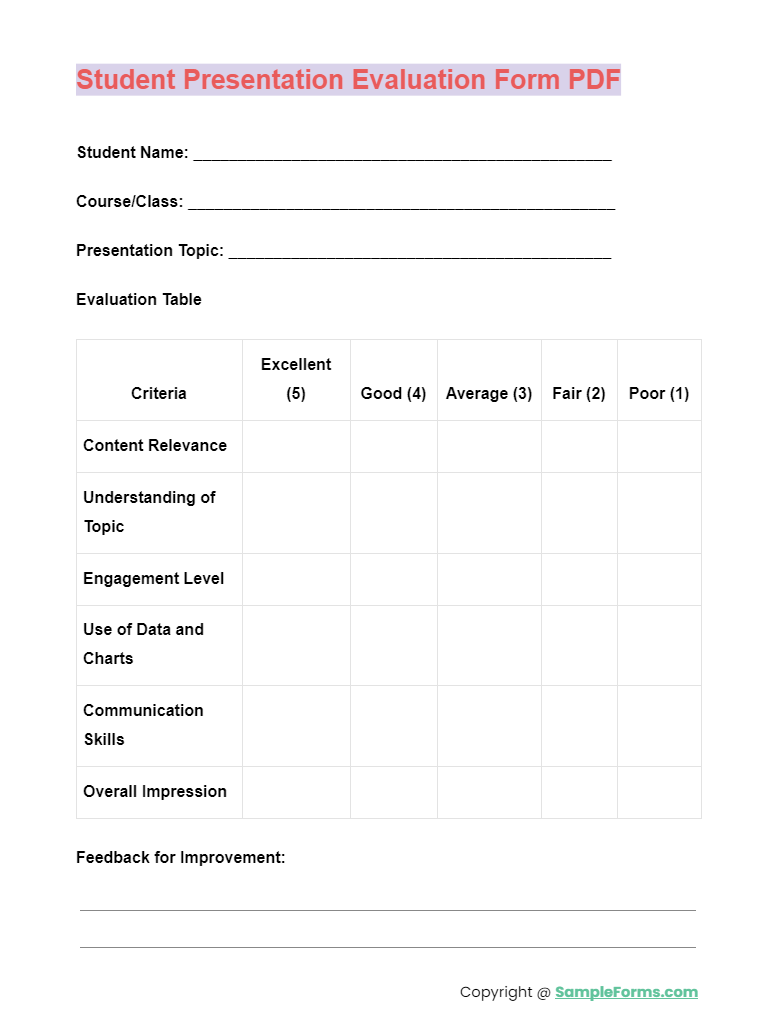

Student Presentation Evaluation Form PDF

Tailored specifically for educational settings, the Student Presentation Evaluation Form PDF facilitates constructive feedback for student presentations. It encourages growth and learning by focusing on content delivery and engagement. This form is a vital part of the Self Evaluation Form process, helping students reflect on their performance and identify self-improvement areas. You should also take a look at our Call Monitoring Evaluation Form

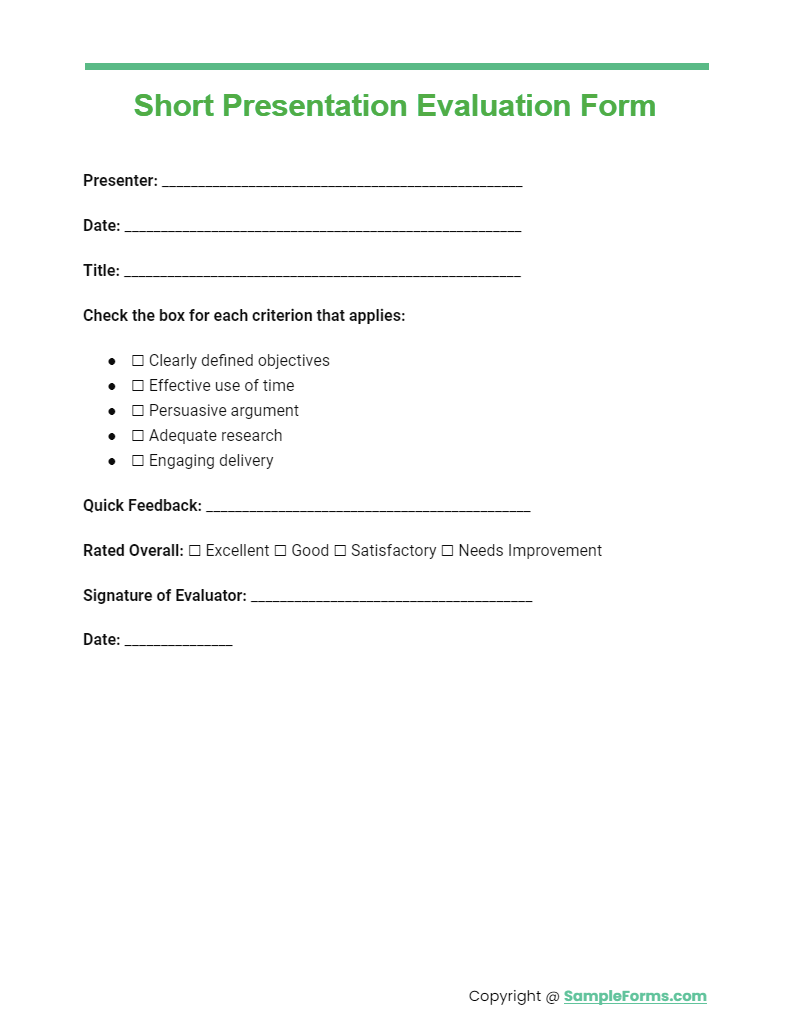

Short Presentation Evaluation Form

Our Short Presentation Evaluation Form is the perfect tool for quick and concise feedback. This streamlined version captures the essence of effective evaluation without overwhelming respondents, making it ideal for busy environments. Incorporate it into your Training Evaluation Form strategy to boost learning outcomes and presentation efficacy. You should also take a look at our Employee Performance Evaluation Form

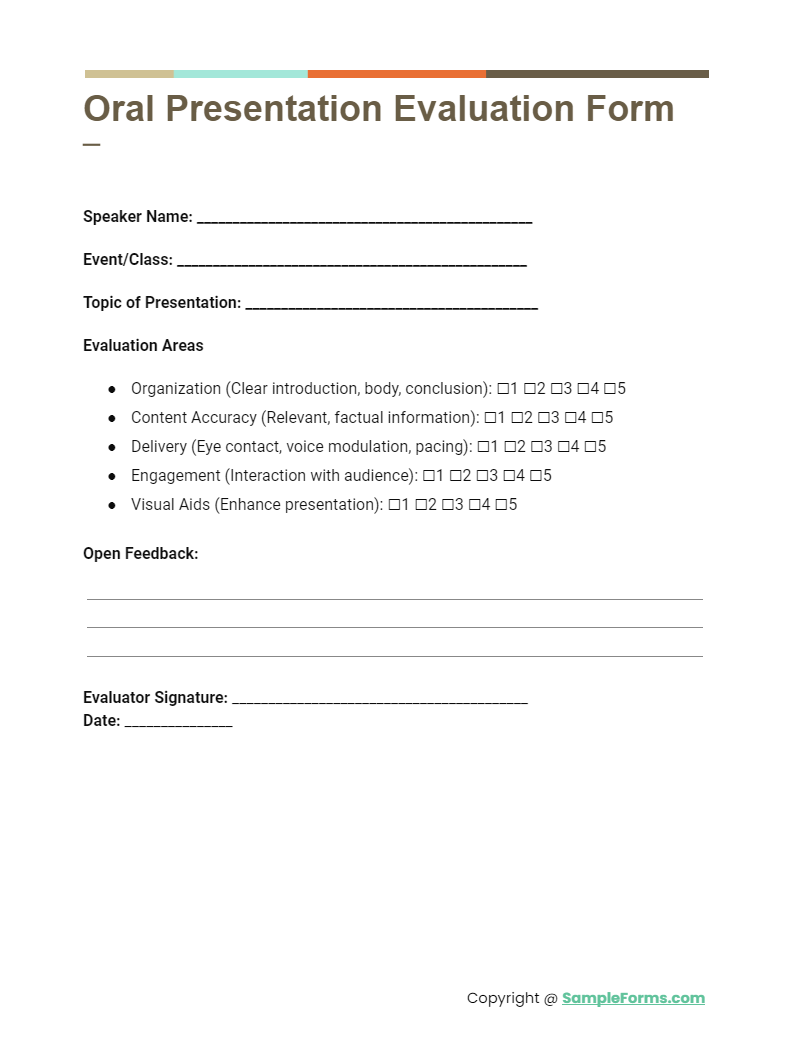

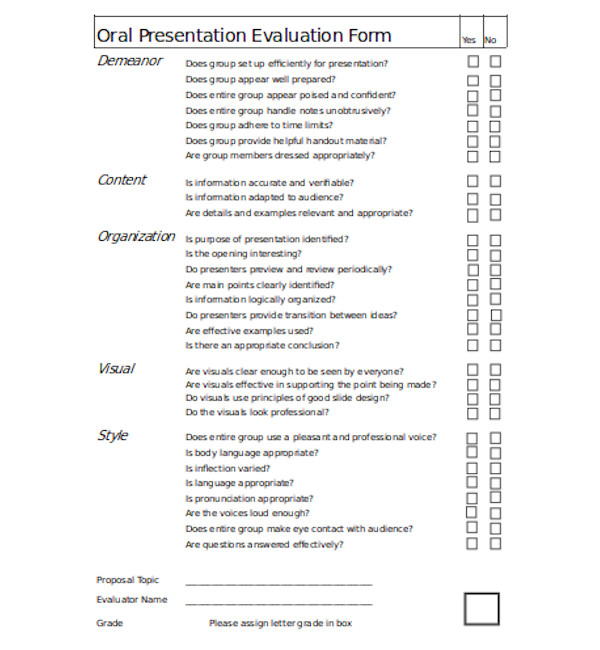

Oral Presentation Evaluation Form

The Oral Presentation Evaluation Form focuses on the delivery and content of spoken presentations. It’s designed to provide speakers with clear, actionable feedback on their verbal communication skills, engaging the audience, and conveying their message effectively. This form complements the Employee Self Evaluation Form , promoting self-awareness and improvement in public speaking skills. You should also take a look at our Interview Evaluation Form

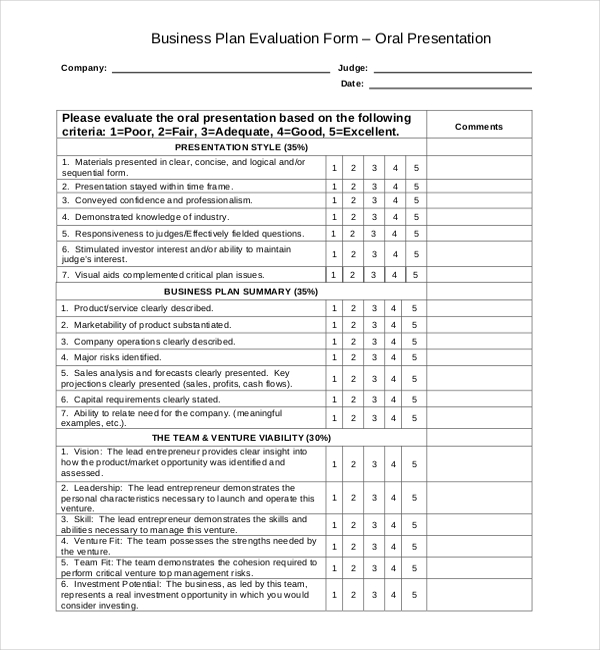

More Presentation Evaluation Form Samples Business Plan Presentation Evaluation Form

nebusinessplancompetition.com

This form is used to evaluate the oral presentation. The audience has to explain whether the materials presented were clear, logical or sequential. The form is also used to explain whether the time frame of the presentation was appropriate. They have to evaluate whether the presentation conveyed professionalism and demonstrated knowledge of the industry.

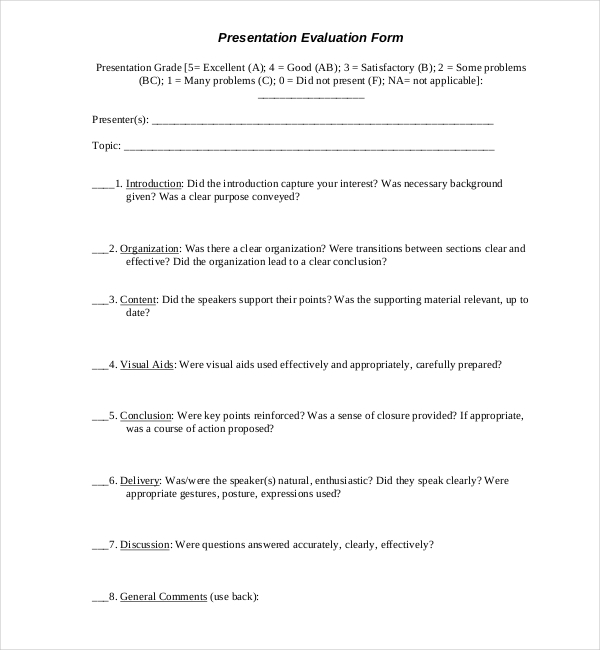

Group Presentation Evaluation Form

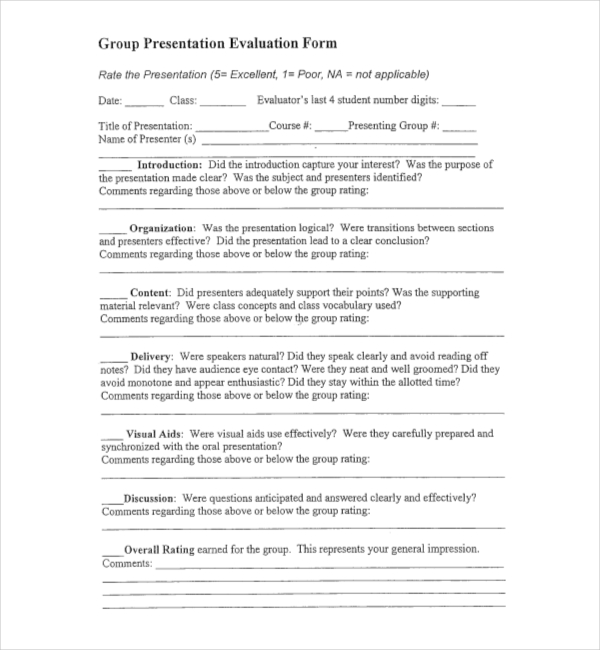

homepages.stmartin.edu

This form is used to explain whether the introduction was capturing their interest. They have to further explain whether the purpose of the presentation clear and logical. They have to explain whether the presentation resulted in a clear conclusion. They have to explain whether the speakers were natural and clear and whether they made eye contact.

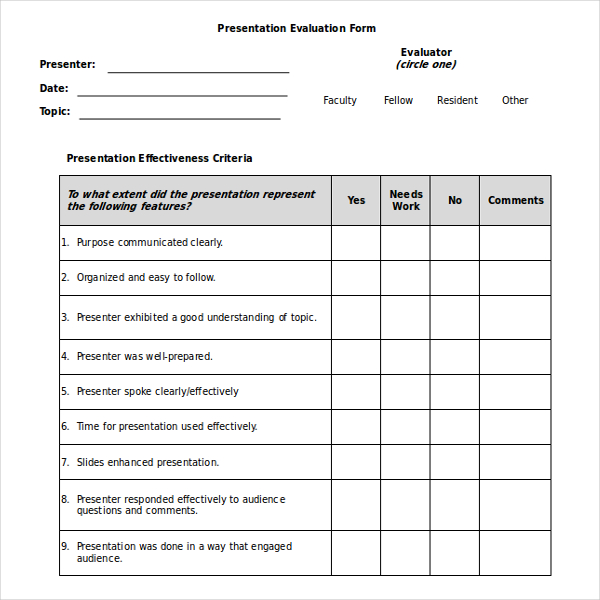

Formal Presentation Evaluation Form

This form is used by audience of the presentation to explain whether the purpose was communicated clearly. They have to further explain whether it was well organized and the presenter had understanding of the topic. The form is used to explain whether the presenter was well-prepared and spoke clearly.

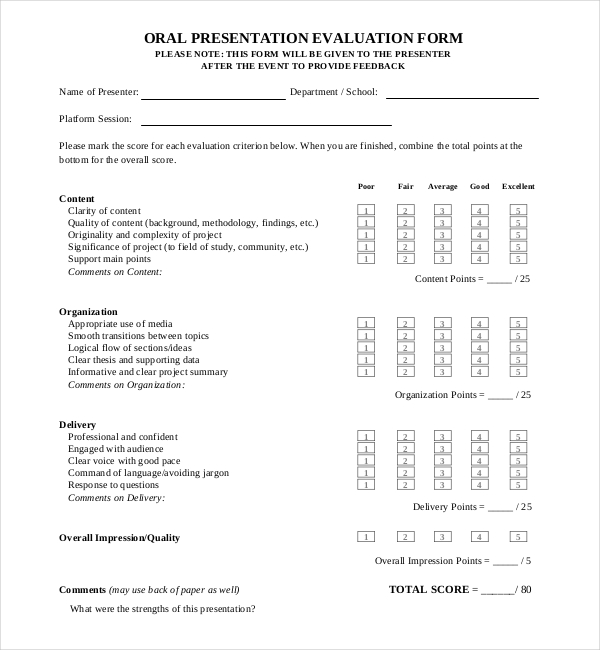

This form is used to evaluate the presentation and circling the suitable rating level. One can also use the provided space to include comments that support ratings. The aim of evaluating the presentation is to know strengths and find areas of required improvement.

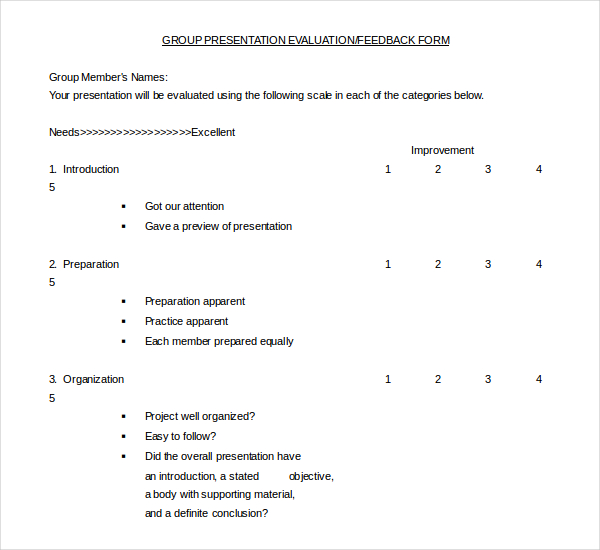

Sample Group Presentation Evaluation Form

scc.spokane.edu

This form is used by students for evaluating other student’s presentation that follow a technical format. It is criteria based form which has points assigned for several criteria. This form is used by students to grade the contributions of all other members of their group who participated in a project.

Presentation Evaluation Form Sample Download

english.wisc.edu

It is vital to evaluate a presentation prior to presenting it to the audience out there. Therefore, the best thing to do after one is done making the presentation is to contact review team in the organization. He/she should have the presentation reviewed prior to the actual presentation day.

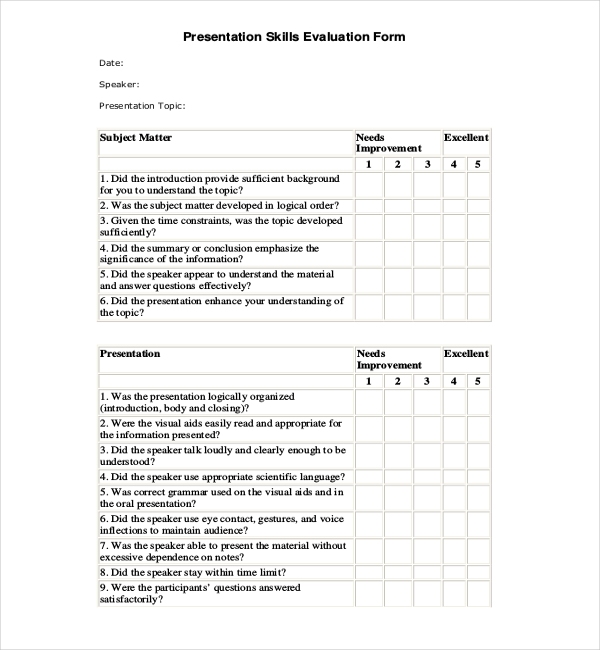

Presentation Skills Evaluation Form

samba.fsv.cuni.cz

There is sample of presentation skills Evaluation forms that one can use to conduct the evaluation. They can finally end up with the proper data as necessary. As opposed to creating a form from scratch, one can simply browse through the templates accessible. They have to explain whether the time and slides effectively used.

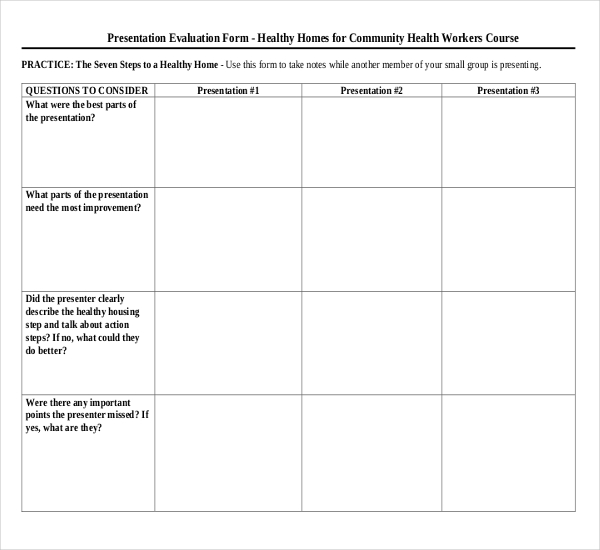

Presentation Evaluation Form Community Health Workers Course

This form is used to explain the best parts and worst parts of the presentation. The user has to explain whether the presenter described the healthy housing and action steps. They have to explain whether the presenter has missed any points and the ways presenter can improve.

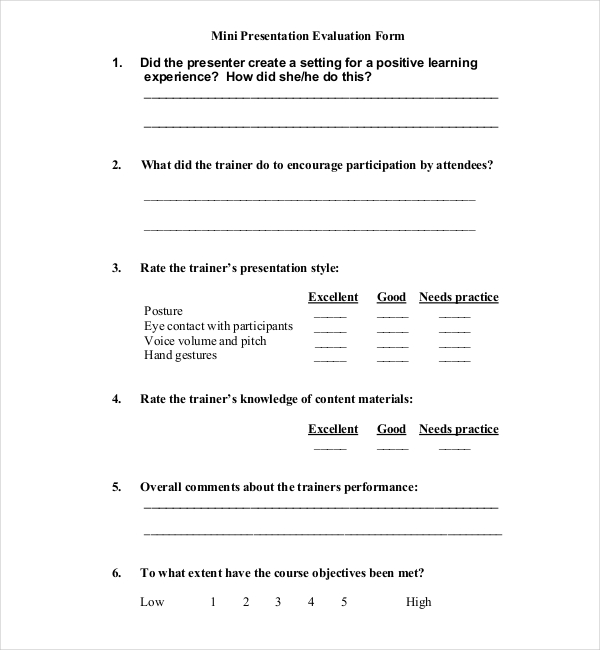

Mini Presentation Evaluation Form

This form is used to explain whether the presenter created a setting for positive learning experience and the way they did. They have to further explain the way the presenter encouraged participation. They have to rate the trainer’s presentation style, knowledge, eye contact, voice and hand gestures.

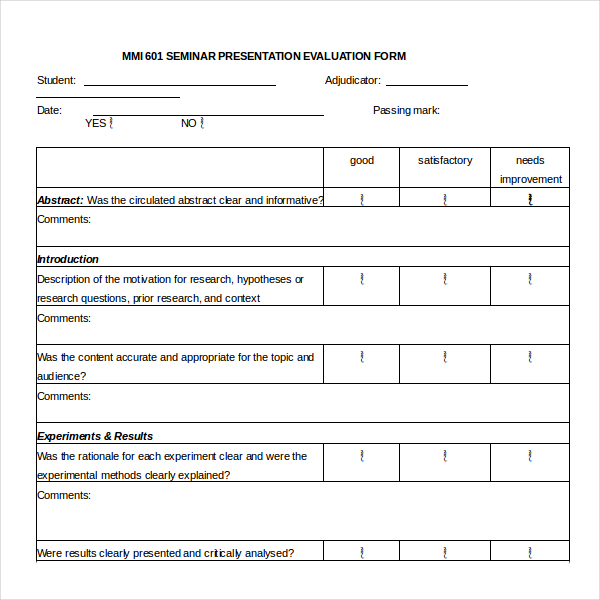

Seminar Presentation Evaluation Form

mmi.med.ualberta.ca

This form is used to give constructive feedback to the students who are presenting any of their seminars. The evaluation results will be used to enhance the effectiveness of the speaker. The speaker will discuss the evaluations with the graduate student’s adviser. This form can be used to add comments.

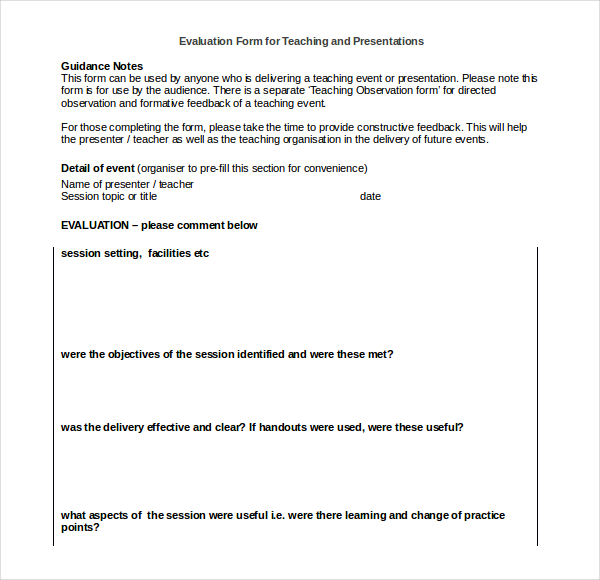

Evaluation Form for Teaching and Presentations

jrcptb.org.uk

This form is used by anyone who is providing a teaching presentation. This form is for use of the audience. There is a different Teaching Observation assessment for formative feedback and direct observation of a teaching event. They are asked to provide constructive feedback to help the presenter and the teaching organization in future events.

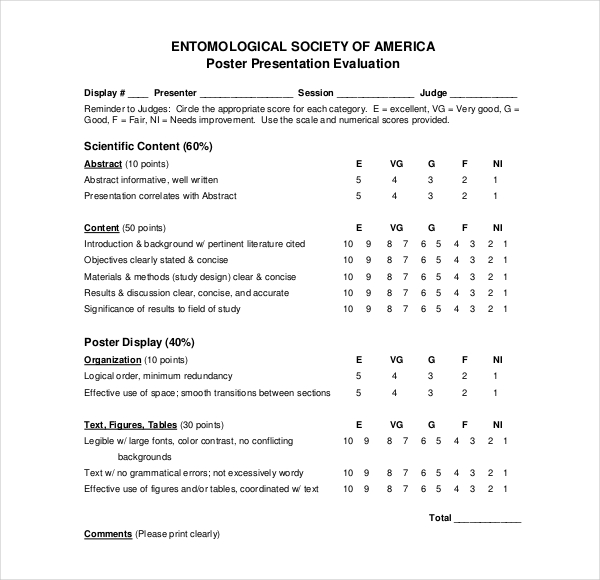

Poster Presentation Evaluation Form

This form involves inspection of the poster with the evaluation of the content and visual presentation. It is also used to discuss the plan to present poster to a reviewer. The questions asked in this process, needs to be anticipated by them. They also add comments, if necessary.

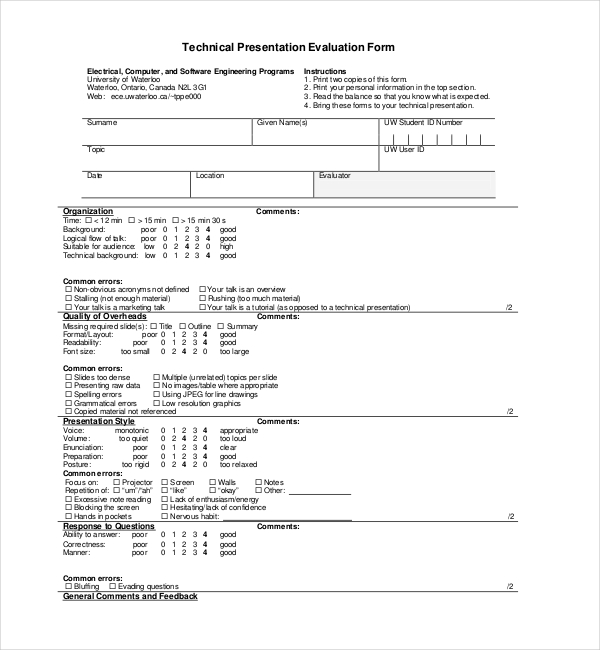

Technical Presentation Evaluation Form

uwaterloo.ca

This form is used to explain whether the introduction, preparation, content, objectives and presentation style was appropriate. It is also used to explain whether it was visually appealing, the project was well presented and the conclusion ended with a summary. One is also asked to explain whether the team was well connected with each other. One can also add overall rating of the project and add comments and grade.

msatterw.public.iastate.edu

10 Uses of Presentation Evaluation Form

- Feedback Collection: Gathers constructive feedback from the audience or evaluators.

- Speaker Improvement: Identifies strengths and areas for improvement for the presenter.

- Content Assessment: Evaluates the relevance and quality of presentation content.

- Delivery Analysis: Reviews the effectiveness of the presenter’s delivery style.

- Engagement Measurement: Gauges audience engagement and interaction.

- Visual Aid Evaluation: Assesses the impact and appropriateness of visual aids used.

- Performance Benchmarking: Sets benchmarks for future presentations.

- Training Needs Identification: Identifies training and development needs for presenters.

- Peer Review: Facilitates peer feedback and collaborative improvement.

- Confidence Building: Helps presenters gain confidence through structured feedback.

How do you write a Presentation Evaluation?

Writing a presentation evaluation begins with understanding the objectives of the presentation. Incorporate elements from the Seminar Evaluation Form to assess the relevance and delivery of content. The evaluation should include:

- An Introduction that outlines the context and purpose of the presentation, setting the stage for the feedback.

- Criteria Assessment , where each aspect of the presentation, such as content clarity, audience engagement, and visual aid effectiveness, is evaluated. For instance, using a Resume Evaluation Form might inspire the assessment of organizational skills and preparedness.

- Overall Impression and Conclusion , which summarize the presentation’s strengths and areas for improvement, providing actionable suggestions for development. This mirrors the approach in a Proposal Evaluation Form , focusing on the impact and feasibility of the content presented.

How do you Evaluate Presentation Performance?

To evaluate presentation performance effectively, consider both the content and the presenter’s delivery skills. Similar to the structured feedback provided in a Speaker Evaluation Form , the evaluation should encompass:

- Content Quality , assessing the accuracy, relevance, and organization of the information presented.

- Delivery Skills , including the presenter’s ability to communicate clearly, maintain eye contact, and engage with the audience.

- The use of Visual Aids and their contribution to the presentation’s overall impact.

- Audience Response , gauging the level of engagement and feedback received, which can be compared to insights gained from an Activity Evaluation Form .

What are 3 examples of Evaluation Forms?

Various evaluation forms can be employed to cater to different assessment needs:

- A Chef Evaluation Form is essential for culinary presentations, focusing on creativity, presentation, and technique.

- The Trainee Evaluation Form offers a comprehensive review of a trainee’s performance, including their learning progress and application of skills.

- For technology-based presentations, a Website Evaluation Form can assess the design, functionality, and user experience of digital projects.

What are the Evaluation Methods for Presentation?

Combining qualitative and quantitative methods enriches the evaluation process. Direct observation allows for real-time analysis of the presentation, while feedback surveys, akin to those outlined in a Performance Evaluation Form , gather audience impressions. Self-assessment encourages presenters to reflect on their performance, utilizing insights similar to those from a Vendor Evaluation Form . Lastly, peer reviews provide an unbiased feedback loop, essential for comprehensive evaluations. Incorporating specific forms and methods, from the Program Evaluation Form to the Basketball Evaluation Form , and even niche-focused ones like the Restaurant Employee Evaluation Form , ensures a detailed and effective presentation evaluation process. This approach not only supports the presenter’s development but also enhances the overall quality of presentations across various fields and contexts. You should also take a look at our Internship Evaluation Form .

10 Tips for Presentation Evaluation Forms

- Be Clear: Define evaluation criteria clearly and concisely.

- Stay Objective: Ensure feedback is objective and based on observable facts.

- Use Rating Scales: Incorporate rating scales for quantifiable feedback.

- Encourage Specifics: Ask for specific examples to support feedback.

- Focus on Constructive Feedback: Emphasize areas for improvement and suggestions.

- Keep It Anonymous: Anonymous feedback can elicit more honest responses.

- Be Comprehensive: Cover content, delivery, visuals, and engagement.

- Follow Up: Use the feedback for discussion and development planning.

- Customize Forms: Tailor forms to the specific presentation type and audience.

- Digital Options: Consider digital forms for ease of collection and analysis.

Can you fail a Pre Employment Physical for being Overweight?

No, being overweight alone typically does not cause failure in a pre-employment physical unless it directly affects job-specific tasks. It’s essential to focus on overall health and ability, similar to assessments in a Mentee Evaluation Form . You should also take a look at our Teacher Evaluation Form

What is usually Included in an Annual Physical Exam?

An annual physical exam typically includes checking vital signs, blood tests, assessments of your organ health, lifestyle discussions, and preventative screenings, mirroring the comprehensive approach of a Sensory Evaluation Form . You should also take a look at our Oral Presentation Evaluation Form

What do you wear to Pre Employment Paperwork?

For pre-employment paperwork, wear business casual attire unless specified otherwise. It shows professionalism, akin to preparing for a Driver Evaluation Form , emphasizing readiness and respect for the process. You should also take a look at our Food Evaluation Form

What does a Pre-employment Physical Consist of?

A pre-employment physical consists of tests measuring physical fitness for the job, including hearing, vision, strength, and possibly drug screening, akin to the tailored approach of a Workshop Evaluation Form . You should also take a look at our Functional Capacity Evaluation Form

Where can I get a Pre Employment Physical Form?

Pre-employment physical forms can be obtained from the hiring organization’s HR department or downloaded from their website, much like how one might access a Sales Evaluation Form for performance review. You should also take a look at our Bid Evaluation Form .

How to get a Pre-employment Physical?

To get a pre-employment physical, contact your prospective employer for the form and details, then schedule an appointment with a healthcare provider who understands the requirements, similar to the process for a Candidate Evaluation Form . You should also take a look at our Customer Service Evaluation Form .

In conclusion, a Presentation Evaluation Form is pivotal for both personal and professional development. Through detailed samples, forms, and letters, this guide empowers users to harness the full benefits of feedback. Whether in debates, presentations, or any public speaking scenario, the Debate Evaluation Form aspect underscores its versatility and significance. Embrace this tool to unlock a new horizon of effective communication and presentation finesse.

Related Posts

Free 8+ sample functional capacity evaluation forms in pdf | ms word, free 9+ sample self evaluation forms in pdf | ms word, free 11+ sample peer evaluation forms in pdf | ms word | excel, free 10+ employee performance evaluation forms in pdf | ms word | excel, free 5+ varieties of sports evaluation forms in pdf, free 8+ sample course evaluation forms in pdf | ms word | excel, free 8+ website evaluation forms in pdf | ms word, free 9+ sample marketing evaluation forms in pdf | ms word, free 11+ internship evaluation forms in pdf | excel | ms word, free 14+ retreat evaluation forms in pdf, free 9+ training evaluation forms in pdf | ms word, free 9+ conference evaluation forms in ms word | pdf | excel, free 3+ construction employee evaluation forms in pdf | ms word, free 20+ sample training evaluation forms in pdf | ms word | excel, free 21+ training evaluation forms in ms word, 7+ seminar evaluation form samples - free sample, example ..., sample conference evaluation form - 10+ free documents in word ..., evaluation form examples, student evaluation form samples - 9+ free documents in word, pdf.

Advertisement

Rubric formats for the formative assessment of oral presentation skills acquisition in secondary education

- Development Article

- Open access

- Published: 20 July 2021

- Volume 69 , pages 2663–2682, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Rob J. Nadolski ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6585-0888 1 ,

- Hans G. K. Hummel 1 ,

- Ellen Rusman 1 &

- Kevin Ackermans 1

10k Accesses

4 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Acquiring complex oral presentation skills is cognitively demanding for students and demands intensive teacher guidance. The aim of this study was twofold: (a) to identify and apply design guidelines in developing an effective formative assessment method for oral presentation skills during classroom practice, and (b) to develop and compare two analytic rubric formats as part of that assessment method. Participants were first-year secondary school students in the Netherlands ( n = 158) that acquired oral presentation skills with the support of either a formative assessment method with analytic rubrics offered through a dedicated online tool (experimental groups), or a method using more conventional (rating scales) rubrics (control group). One experimental group was provided text-based and the other was provided video-enhanced rubrics. No prior research is known about analytic video-enhanced rubrics, but, based on research on complex skill development and multimedia learning, we expected this format to best capture the (non-verbal aspects of) oral presentation performance. Significant positive differences on oral presentation performance were found between the experimental groups and the control group. However, no significant differences were found between both experimental groups. This study shows that a well-designed formative assessment method, using analytic rubric formats, outperforms formative assessment using more conventional rubric formats. It also shows that higher costs of developing video-enhanced analytic rubrics cannot be justified by significant more performance gains. Future studies should address the generalizability of such formative assessment methods for other contexts, and for complex skills other than oral presentation, and should lead to more profound understanding of video-enhanced rubrics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Viewbrics: A Technology-Enhanced Formative Assessment Method to Mirror and Master Complex Skills with Video-Enhanced Rubrics and Peer Feedback in Secondary Education

Students’ and Teachers’ Perceptions of the Usability and Usefulness of the First Viewbrics-Prototype: A Methodology and Online Tool to Formatively Assess Complex Generic Skills with Video-Enhanced Rubrics (VER) in Dutch Secondary Education

The Dilemmas of Formulating Theory-Informed Design Guidelines for a Video Enhanced Rubric

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Both practitioners and scholars agree that students should be able to present orally (e.g., Morreale & Pearson, 2008 ; Smith & Sodano, 2011 ). Oral presentation involves the development and delivery of messages to the public with attention to vocal variety, articulation, and non-verbal signals, and with the aim to inform, self-express, relate to and persuade listeners (Baccarini & Bonfanti, 2015 ; De Grez et al., 2009a ; Quianthy, 1990 ). The current study is restricted to informative presentations (as opposed to persuasive presentations), as these are most common in secondary education. Oral presentation skills are complex generic skills of increasing importance for both society and education (Voogt & Roblin, 2012 ). However, secondary education seems to be in lack of instructional design guidelines for supporting oral presentation skills acquisition. Many secondary schools in the Netherlands are struggling with how to teach and assess students’ oral presentation skills, lack clear performance criteria for oral presentations, and fall short in offering adequate formative assessment methods that support the effective acquisition of oral presentation skills (Sluijsmans et al., 2013 ).

Many researchers agree that the acquisition and assessment of presentation skills should depart from a socio-cognitive perspective (Bandura, 1986 ) with emphasis on observation, practice, and feedback. Students practice new presentation skills by observing other presentations as modeling examples, then practice their own presentation, after which the feedback is addressed by adjusting their presentations towards the required levels. Evidently, delivering effective oral presentations requires much preparation, rehearsal, and practice, interspersed with good feedback, preferably from oral presentation experts. However, large class sizes in secondary schools of the Netherlands offer only limited opportunities for teacher-student interaction, and offer even fewer practice opportunities. Based on research on complex skill development and multimedia learning, it can be expected that video-enhanced analytic rubric formats best capture and guide oral presentation performance, since much non-verbal behavior cannot be captured in text (Van Gog et al., 2014 ; Van Merriënboer & Kirschner, 2013 ).

Formative assessment of complex skills

To support complex skills acquisition under limited teacher guidance, we will need more effective formative assessment methods (Boud & Molloy, 2013 ) based on proven instructional design guidelines. During skills acquisition students will perceive specific feedback as more adequate than non-specific feedback (Shute, 2008 ). Adequate feedback should inform students about (i) their task-performance, (ii) their progress towards intended learning goals, and (iii) what they should do to further progress towards those goals (Hattie & Timperly, 2007 ; Narciss, 2008 ). Students receiving specific feedback on criteria and performance levels will become equipped to improve oral presentation skills (De Grez et al., 2009a ; Ritchie, 2016 ). Analytic rubrics are therefore promising formats to provide specific feedback on oral presentations, because they can demonstrate the relations between subskills and explain the open-endedness of ideal presentations (through textual descriptions and their graphical design).

Ritchie ( 2016 ) showed that adding structure and self-assessment to peer- and teacher-assessments resulted in better oral presentation performance. Students were required to use analytic rubrics for self-assessment when following their (project-based) classroom education. In this way, they had ample opportunity for observing and reflecting on (good) oral presentations attributes, which was shown to foster acquisition of their oral presentation skills.

Analytic rubrics incorporate performance criteria to inform teachers and students when preparing oral presentation. Such rubrics support mental model formation, and enable adequate feedback provision by teachers, peers, and self (Brookhart & Chen, 2015 ; Jonsson & Svingby, 2007 ; Panadero & Jonsson, 2013 ). Such research is inconclusive about what are most effective formats and delivery media, but most studies dealt with analytic text-based rubrics delivered on paper. However, digital video-enhanced analytic rubrics are expected to be more effective for acquiring oral presentation skills, since many behavioral aspects refer to non-verbal actions and processes that can only be captured on video (e.g., body posture or use of voice during a presentation).

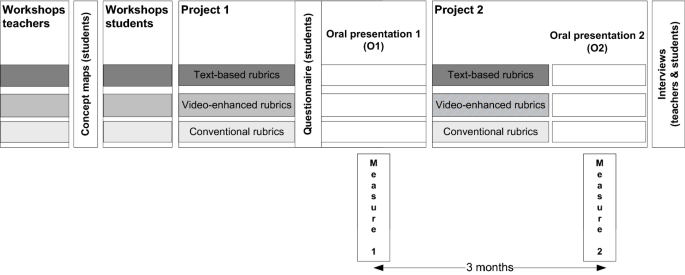

This study is situated within the Viewbrics project where video-modelling examples are integrated with analytic text-based rubrics (Ackermans et al., 2019a ). Video-modelling examples contain question prompts that illustrate behavior associated with (sub)skills performance levels in context, and are presented by young actors the target group can identify with. The question prompts require students to link behavior to performance levels, and build a coherent picture of the (sub)skills and levels. To the best of authors’ knowledge, there exist no previous studies on such video-enhanced analytic rubrics. The Viewbrics tool has been incrementally developed and validated with teachers and students to structure the formative assessment method in classroom settings (Rusman et al., 2019 ).

The purpose of our study is twofold. On the one hand, it investigates whether the application of evidence-based design guidelines results in a more effective formative assessment method in classroom. On the other hand, it investigates (within that method) whether video-enhanced analytic rubrics are more effective than text-based analytic rubrics.

Research questions

The twofold purpose of this study is stated by two research questions: (1) To what extent do analytic rubrics within formative assessment lead to better oral presentation performance? (the design-based part of this study); and (2) To what extent do video-enhanced analytic rubrics lead to better oral presentation performance (growth) than text-based analytic rubrics? (the experimental part of this study). We hypothesize that all students will improve their oral presentation performance in time, but that students in the experimental groups (receiving analytic rubrics designed according to proven design guidelines) will outperform a control group (receiving conventional rubrics) (Hypothesis 1). Furthermore, we expect the experimental group using video-enhanced rubrics to achieve more performance growth than the experimental group using text-based rubrics (Hypothesis 2).

After this introduction, the second section describes previous research on design guidelines that were applied to develop the analytic rubrics in the present study. The actual design, development and validation of these rubrics is described in “ Development of analytic rubrics tool ” section. “ Method ” section describes the experimental method of this study, whereas “ Results ” section reports its results. Finally, in the concluding “ Conclusions and discussion ” section, main findings and limitations of the study are discussed, and suggestions for future research are provided.

Previous research and design guidelines for formative assessment with analytic rubrics

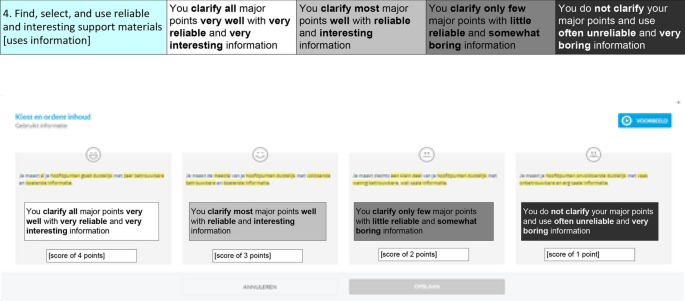

Analytic rubrics are inextricably linked with assessment, either summative (for final grading of learning products) or formative (for scaffolding learning processes). They provide textual descriptions of skills’ mastery levels with performance indicators that describe concrete behavior for all constituent subskills at each mastery level (Allen & Tanner, 2006 ; Reddy, 2011 ; Sluijsmans et al., 2013 ) (see Figs. 1 and 2 in “ Development of analytic rubrics tool ” section for an example). Such performance indicators specify aspects of variation in the complexity of a (sub)skill (e.g., presenting for a small, homogeneous group as compared to presenting for a large heterogeneous group) and related mastery levels (Van Merriënboer & Kirschner, 2013 ). Analytic rubrics explicate criteria and expectations, can be used to check students’ progress, monitor learning, and diagnose learning problems, either by teachers, students themselves or by their peers (Rusman & Dirkx, 2017 ).

Subskills for oral presentation assessment

Specification of performance levels for criterium 4

Several motives for deploying analytic rubrics in education are distinguished. A review study by Panadero and Jonsson ( 2013 ) identified following motives: increasing transparency, reducing anxiety, aiding the feedback process, improving student self-efficacy, and supporting student self-regulation. Analytic rubrics also improve reliability among teachers when rating their students (Jonsson & Svingby, 2007 ). Evidence has shown that analytic rubrics can be utilized to enhance student performance and learning when they were used for formative assessment purposes in combination with metacognitive activities, like reflection and goal-setting, but research shows mixed results about their learning effectiveness (Panadero & Jonsson, 2013 ).

It remains unclear what is exactly needed to make their feedback effective (Reddy & Andrade, 2010 ; Reitmeier & Vrchota, 2009 ). Apparently, transparency of assessment criteria and learning goals (i.e., make expectations and criteria explicit) is not enough to establish effectiveness (Wöllenschläger et al., 2016 ). Several researchers stressed the importance of how and which feedback to provide with rubrics (Bower et al., 2011 ; De Grez et al., 2009b ; Kerby & Romine, 2009 ). We now continue this section by reviewing design guidelines for analytic rubrics we encountered in literature, and then specifically address what literature mentions about the added value of video-enhanced rubrics.

Design guidelines for analytic rubrics

Effective formative assessment methods for oral presentation and analytic rubrics should be based on proven instructional design guidelines (Van Ginkel et al., 2015 ). Table 1 presents an overview of (seventeen) guidelines on analytic rubrics we encountered in literature. Guidelines 1–4 inform us how to use rubrics for formative assessment; Guidelines 5–17 inform us how to use rubrics for instruction, with Guidelines 5–9 on a rather generic, meso level and Guidelines 10–17 on a more specific, micro level. We will now shortly describe them in relation to oral presentation skills.

Guideline 1: use analytic rubrics instead of rating scale rubrics if rubrics are meant for learning

Conventional rating-scale rubrics are easy to generate and use as they contain scores for each performance criterium (e.g., by a 5-point Likert scale). However, since each performance level is not clearly described or operationalized, rating can suffer from rater-subjectivity, and rating scales do not provide students with unambiguous feedback (Suskie, 2009 ). Analytic rubrics can address those shortcomings as they contain brief textual performance descriptions on all subskills, criteria, and performance levels of complex skills like presentation, but are harder to develop and score (Bargainnier, 2004 ; Brookhart, 2004 ; Schreiber et al., 2012 ).

Guideline 2: use self-assessment via rubrics for formative purposes

Analytic rubrics can encourage self-assessment and -reflection (Falchikov & Boud, 1989 ; Reitmeier & Vrchota, 2009 ), which appears essential when practicing presentations and reflecting on other presentations (Van Ginkel et al., 2017 ). The usefulness of self-assessment for oral presentation was demonstrated by Ritchie’s study ( 2016 ), but was absent in a study by De Grez et al. ( 2009b ) that used the same rubric.

Guideline 3: use peer-assessment via rubrics for formative purposes

Peer-feedback is more (readily) available than teacher-feedback, and can be beneficial for students’ confidence and learning (Cho & Cho, 2011 ; Murillo-Zamorano & Montanero, 2018 ), also for oral presentation (Topping, 2009 ). Students positively value peer-assessment if the circumstances guarantee serious feedback (De Grez et al., 2010 ; Lim et al., 2013 ). It can be assumed that using analytic rubrics positively influences the quality of peer-assessment.

Guideline 4: provide rubrics for usage by self, peers, and teachers as students appreciate rubrics

Students appreciate analytic rubrics because they support them in their learning, in their planning, in producing higher quality work, in focusing efforts, and in reducing anxiety about assignments (Reddy & Andrade, 2010 ), aspects of importance for oral presentation. While students positively perceive the use of peer-grading, the inclusion of teacher-grades is still needed (Mulder et al., 2014 ) and most valued by students (Ritchie, 2016 ).

Guidelines 5–9

Heitink et al. ( 2016 ) carried out a review study identifying five relevant prerequisites for effective classroom instruction on a meso-level when using analytic rubrics (for oral presentations): train teachers and students in using these rubrics, decide on a policy of their use in instruction, while taking school- and classroom contexts into account, and follow a constructivist learning approach. In the next section, it is described how these guidelines were applied to the design of this study’s classroom instruction.

Guidelines 10–17

Van Ginkel et al. ( 2015 ) review study presents a comprehensive overview of effective factors for oral presentation instruction in higher education on a micro-level. Although our research context is within secondary education, the findings from the aforementioned study seem very applicable as they were rooted in firmly researched and well-documented Instructional Design approaches. Their guidelines pertain to (a) instruction, (b) learning, and (c) assessment in the learning environment (Biggs, 2003 ). The next section describes how guidelines were applied to the design of this study’s online Viewbrics tool.

- Video-enhanced rubrics

Early analytic rubrics for oral presentations were all text-based descriptions. This study assumes that such analytic rubrics may fall short when used for learning to give oral presentations, since much of the required performance refers to motoric activities, time-consecutive operations and processes that can hardly be captured in text (e.g., body posture or use of voice during a presentation). Text-based rubrics also have a limited capacity to convey contextualized and more ‘tacit’ behavioral aspects (O’Donnevan et al., 2004 ), since ‘tacit knowledge’ (or ‘knowing how’) is interwoven with practical activities, operations, and behavior in the physical world (Westera, 2011 ). Finally, text leaves more space for personal interpretation (of performance indicators) than video, which negatively influences mental model formation and feedback consistency (Lew et al., 2010 ).

We can therefore expect video-enhanced rubrics to overcome such restrictions, as they can integrate modelling examples with analytic text-based explanations. The video-modelling examples and its embedded question prompts can illustrate behavior associated with performance levels in context, and contain information in different modalities (moving images, sound). Video-enhanced rubrics foster learning from active observation of video-modelling examples (De Grez et al., 2014 ; Rohbanfard & Proteau, 2013 ), especially when combined with textual performance indicators. Looking at effects of video-modelling examples, Van Gog et al. ( 2014 ) found an increased task performance when the video-modelling example of an expert was also shown. De Grez et al. ( 2014 ) found comparable results for learning to give oral presentations. Teachers in training assessing their own performance with video-modelling examples appeared to overrate their performance less than without examples (Baecher et al., 2013 ). Research on mastering complex skills indicates that both modelling examples (in a variety of application contexts) and frequent feedback positively influence the learning process and skills' acquisition (Van Merriënboer & Kirschner, 2013 ). Video-modelling examples not only capture the ‘know-how’ (procedural knowledge), but also elicit the ‘know-why’ (strategic/decisive knowledge).

Development of analytic rubrics tool

This section describes how design guidelines from previous research were applied in the actual development of the rubrics in the Viewbrics tool for our study, and then presents the subskills and levels for oral presentation skills as were defined.

Application of design guidelines

The previous section already mentioned that analytic rubrics should be restricted to formative assessment (Guidelines 2 and 3), and that there are good reasons to assume that a combination of teacher-, peer-, and self-assessment will improve oral presentations (Guidelines 1 and 4). Teachers and students were trained in rubric-usage (Guidelines 5 and 7), whereas students were motivated for using rubrics (Guideline 7). As participating schools were already using analytic rubrics, one might assume their positive initial attitude. Although the policy towards using analytic rubrics might not have been generally known at the work floor, the participating teachers in our study were knowledgeable (Guideline 6). We carefully considered the school context, as (a representative set of) secondary schools in the Netherlands were part of the Viewbrics team (Guideline 8). The formative assessment method was embedded within project-based education (Guideline 9).

Within this study and on the micro-level of design, the learning objectives for the first presentation were clearly specified by lower performance levels, whereas advice on students' second presentation focused on improving specific subskills, that had been performed with insufficient quality during the first presentation (Guideline 10). Students carried out two consecutive projects of increasing complexity (Project 1, Project 2) with authentic tasks, amongst which the oral presentations (Guideline 11). Students were provided with opportunities to observe peer-models to increase their self-efficacy beliefs and oral presentation competence. In our study, only students that received video-enhanced rubrics could observe videos with peer-models before their first presentation (Guideline 12). Students were allowed enough opportunities to rehearse their oral presentations, to increase their presentation competence, and to decrease their communication apprehension. Within our study, only two oral presentations could be provided feedback, but students could rehearse as often as they wanted outside the classroom (Guideline 13). We ensured that feedback in the rubrics was of high quality, i.e., explicit, contextual, adequately timed, and of suitable intensity for improving students’ oral presentation competence. Both experimental groups in the study used digital analytic rubrics within the Viewbrics tool (both teacher-, peer-, and self-feedback). The control group received feedback by a more conventional rubric (rating scale), and could therefore not use the formative assessment and reflection functions (Guideline 14). The setup of the study implied that all peers play a major role during formative assessment in both experimental groups, because they formatively assessed each oral presentation using the Viewbrics tool (Guideline 15). The control group received feedback from their teacher. Both experimental groups used the Viewbrics tool to facilitate self-assessment (Guideline 16). The control group did not receive analytic progress data to inform their self-assessment. Specific goal-setting within self-assessment has been shown to positively stimulate oral presentation performance, to improve self-efficacy and reduce presentation anxiety (De Grez et al., 2009a ; Luchetti et al., 2003 ), so the Viewbrics tool was developed to support both specific goal-setting and self-reflection (Guideline 17).

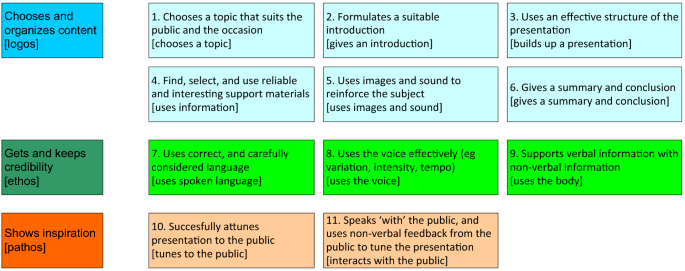

Subskills and levels for oral presentation

Reddy and Andrade ( 2010 ) stress that rubrics should be tailored to the specific learning objectives and target groups. Oral presentations in secondary education (our study context) involve generating and delivering informative messages with attention to vocal variety, articulation, and non-verbal signals. In this context, message composition and message delivery are considered important (Quianthy, 1990 ). Strong arguments (‘logos’) have to be presented in a credible (‘ethos’) and exciting (‘pathos’) way (Baccarini & Bonfanti, 2015 ). Public speaking experts agree that there is not one right way to do an oral presentation (Schneider et al., 2017 ). There is agreement that all presenters need much practice, commitment, and creativity. Effective presenters do not rigorously and obsessively apply communication rules and techniques, as their audience may then perceive the performance as too technical or artificial. But all presentations should demonstrate sufficient mastery of elementary (sub)skills in an integrated manner. Therefore, such skills should also be practiced as a whole (including knowledge and attitudes), making the attainment of a skill performance level more than the sum of its constituent (sub)skills (Van Merriënboer & Kirschner, 2013 ). A validated instrument for assessing oral presentation performance is needed to help teachers assess and support students while practicing.

When we started developing rubrics with the Viewbrics tool (late 2016), there were no studies or validated measuring instruments for oral presentation performance in secondary education, although several schools used locally developed, non-validated assessment forms (i.e., conventional rubrics). For instance, Schreiber et al. ( 2012 ) had developed an analytic rubric for public speaking skills assessment in higher education, aimed at faculty members and students across disciplines. They identified eleven (sub)skills of public speaking, that could be subsumed under three factors (‘topic adaptation’, ‘speech presentation’ and ‘nonverbal delivery’, similar to logos-ethos-pathos).

Such previous work holds much value, but still had to be adapted and elaborated in the context of the current study. This study elaborated and evaluated eleven subskills that can be identified within the natural flow of an oral presentation and its distinctive features (See Fig. 1 for an overview of subskills, and Fig. 2 for a specification of performance levels for a specific subskill).

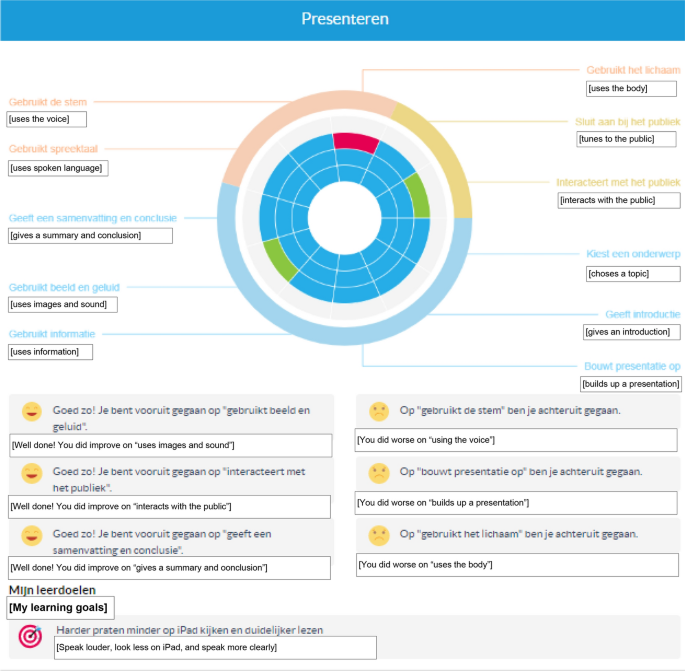

Between brackets are names of subskills as they appear in the dashboard of the Viewbrics tool (Fig. 3 ).

Visualization of oral presentation progress and feedback in the Viewbrics tool

The upper part of Fig. 2 shows the scoring levels for first-year secondary school students for criterium 4 of the oral presentation assessment (four values, from more expert (4 points) to more novice (1 point), from right to left), an example of the conventional rating-scale rubrics. The lower part shows the corresponding screenshot from the Viewbrics tool, representing a text-based analytic rubric example. A video-enhanced analytic rubric example for this subskill provides a peer modelling the required behavior on expert level, with question prompts on selecting reliable and interesting materials. Performance levels were inspired by previous research (Ritchie, 2016 ; Schneider et al., 2017 ; Schreiber et al., 2012 ), but also based upon current secondary school practices in the Netherlands, and developed and tested with secondary school teachers and their students.

All eleven subskills are to be scored on similar four-point Likert scales, and have similar weights in determining total average scores. Two pilot studies tested the usability, validity and reliability of the assessment tool (Rusman et al., 2019 ). Based on this input, the final rubrics were improved and embedded in a prototype of the online Viewbrics tool, and used for this study. The formative assessment method consisted of six steps: (1) study the rubric; (2) practice and conduct an oral presentation; (3) conduct a self-assessment; (4) consult feedback from teacher and peers; (5) Reflect on feedback; and (6) select personal learning goal(s) for the next oral presentation.