- Short Contribution

- Open access

- Published: 01 March 2018

Enhancing SARA: a new approach in an increasingly complex world

- Steve Burton 1 &

- Mandy McGregor 2

Crime Science volume 7 , Article number: 4 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

38k Accesses

2 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

The research note describes how an enhancement to the SARA (Scan, Analyse, Respond and Assess) problem-solving methodology has been developed by Transport for London for use in dealing with crime and antisocial behaviour, road danger reduction and reliability problems on the transport system in the Capital. The revised methodology highlights the importance of prioritisation, effective allocation of intervention resources and more systematic learning from evaluation.

Introduction

Problem oriented policing (POP), commonly referred to as problem-solving in the UK, was first described by Goldstein ( 1979 , 1990 ) and operationalised by Eck and Spelman ( 1987 ) using the SARA model. SARA is the acronym for Scanning, Analysis, Response and Assessment. It is essentially a rational method to systematically identify and analyse problems, develop specific responses to individual problems and subsequently assess whether the response has been successful (Weisburd et al. 2008 ).

A number of police agencies around the world use this approach, although its implementation has been patchy, has often not been sustained and is particularly vulnerable to changes in the commitment of senior staff and lack of organisational support (Scott and Kirby 2012 ). This short contribution outlines the way in which SARA has been used and further developed by Transport for London (TfL, the strategic transport authority for London) and its policing partners—the Metropolitan Police Service, British Transport Police and City of London Police. Led by TfL, they have been using POP techniques to deal with crime and disorder issues on the network, with some success. TfL’s problem-solving projects have been shortlisted on three occasions for the Goldstein Award, an international award that recognises excellence in POP initiatives, winning twice in 2006 and 2011 (see Goldstein Award Winners 1993–2010 ).

Crime levels on the transport system are derived from a regular and consistent data extract from the Metropolitan Police Service and British Transport Police crime recording systems. In 2006, crime levels on the bus network were causing concern. This was largely driven by a sudden rise in youth crime with a 72 per cent increase from 2005 to 2006: The level rose from around 290 crimes involving one or more suspects aged under 16 years per month in 2005 to around 500 crimes per month in 2006.

Fear of crime was also an issue and there were increasing public and political demands for action. In response TfL, with its policing partners, worked to embed a more structured and systematic approach to problem-solving, allowing them to better identify, manage and evaluate their activities. Since then crime has more than halved on the network (almost 30,000 fewer crimes each year) despite significant increases in passenger journeys (Fig. 1 ). This made a significant contribution to the reduction in crime from 20 crimes per million passenger journeys in 2005/6 to 7.5 in 2016/17.

Crime volumes and rates on major TfL transport networks and passenger levels

Although crime has being falling generally over the last decade, the reduction on London’s public transport network has been comparatively greater than that seen overall in London and in England and Wales (indexed figures can be seen in Fig. 2 ). The reductions on public transport are even more impressive given that there are very few transport-related burglary and vehicle crimes which have been primary drivers of the overall reductions seen in London and England and Wales. TfL attributes this success largely to its problem-solving approach and the implementation of a problem-solving framework and supporting processes.

UK, London and transport crime trends since 2005/6

A need for change

TfL remains fully committed to problem-solving and processes are embedded within its transport policing, enforcement and compliance activities. However, it has become apparent that its approach needs to develop further in response to a number of emerging issues:

broadening of SARA beyond a predominant crime focus to address road danger reduction and road reliability problems;

increasing strategic complexity in the community safety and policing arena for example, the increased focus on safeguarding and vulnerability;

the increasing pace of both social and technological change, for example, sexual crimes such as ‘upskirting’ and ‘airdropping of indecent images’ (see http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/london-tube-sexual-assault-underground-transportation-harassment-a8080756.html );

financial challenges and resource constraints yet growing demands for policing and enforcement action to deal with issues;

greater focus on a range of non-enforcement interventions as part of problem solving responses;

a small upturn in some crime types including passenger aggression and low-level violence when the network is at peak capacity;

increasing focus on evidence-led policing and enforcement, and;

some evidence of cultural fatigue among practitioners with processes which indicated a refresh of the approach might be timely.

Implications

In response, TfL undertook a review of how SARA and its problem-solving activities are being delivered and considered academic reviews and alternative models such as the 5I’s as developed by Ekblom ( 2002 ) and those assessed by Sidebottom and Tilley ( 2011 ). This review resulted in a decision to continue with a SARA-style approach because of its alignment with existing processes and the practitioner base that had already been established around SARA. This has led to a refresh of TfL’s strategic approach to managing problem-solving which builds on SARA and aims to highlight the importance of prioritisation, effective allocation of intervention resources and capturing the learning from problem-solving activities at a strategic and tactical level. Whilst these stages are implicit within the SARA approach, it was felt that a more explicit recognition of their importance as component parts of the process would enhance overall problem-solving efforts undertaken by TfL and its policing partners. The revised approach, which recognises these important additional steps in the problem-solving process, has been given the acronym SPATIAL—Scan, Prioritise, Analyse, Task, Intervene, Assess and Learn as defined in Table 1 below:

SPATIAL adapts the SARA approach to address a number of emerging common issues affecting policing and enforcement agencies over recent years. The financial challenges now facing many organisations mean that limited budgets and constrained resources are inadequate to be able to solve all problems identified. The additional steps in the SPATIAL process help to ensure that there is (a) proper consideration and prioritisation of identified ‘problems’ (b) effective identification and allocation of resources to deal with the problem, considering the impact on other priorities and (c) capture of learning from the assessment of problem-solving efforts so that evidence of what works (including an assessment of process, cost, implementation and impact) can be incorporated in the development of problem-solving action and response plans where appropriate. The relationship between SARA and SPATIAL is shown in Fig. 3 below:

SARA and SPATIAL

In overall terms SPATIAL helps to ensure that TfL and policing partners’ problem-solving activities are developed, coordinated and managed in a more structured way. Within TfL problem-solving is implemented at three broad levels—Strategic, Tactical and Operational. Where problems and activities sit within these broad levels depends on the timescale, geographic spread, level of harm and profile. These can change over time. Operational activities continue to be driven by a problem-solving process based primarily on SARA as they do not demand the same level of resource prioritisation and scale of evaluation, with a SPATIAL approach applied at a strategic level. In reality a number of tactical/operational problem-oriented policing activities will form a subsidiary part of strategic problem-solving plans. Table 2 provides examples of problems at these three levels.

The processes supporting delivery utilise existing well established practices used by TfL and its partners. These include Transtat (the joint TfL/MPS version of the ‘CompStat’ performance management process for transport policing), a strategic tasking meeting (where the ‘P’ in SPATIAL is particularly explored) and an Operations Hub which provides deployment oversight and command and control services for TfL’s on-street resources. Of course, in reality these processes are not always sequential. In many cases there will be feedback loops to allow refocusing of the problem definition and re-assessment of problem-solving plans and interventions.

For strategic and tactical level problems, the SPATIAL framework provides senior officers with greater oversight of problem-solving activity at all stages of the problem-solving process. It helps to ensure that TfL and transport policing resources are focussed on the right priorities, that the resource allocation is appropriate across identified priorities and that there is oversight of the problem-solving approaches being adopted, progress against plans and delivery of agreed outcomes.

Although these changes are in the early stages of implementation, it is already clear that they provide the much needed focus around areas such as strategic prioritisation and allocation of TfL, police and other partner resources (including officers and other interventions such as marketing, communications and environmental changes). The new approach also helps to ensure that any lessons learned from the assessment are captured and used to inform evidence-based interventions for similar problems through the use of a bespoke evaluation framework (adaptation of the Maryland scientific methods scale, see Sherman et al. 1998 ) and the implementation of an intranet based library. The adapted approach also resonates with practitioners because it builds on the well-established SARA process but brings additional focus to prioritising issues and optimising resources. More work is required to assess the medium and longer term implications and benefits derived from the new process and this will be undertaken as it becomes more mature.

Eck, J., & Spelman, W. (1987). Problem - solving: problem - oriented policing in newport news . Washington, D.C.: Police Executive Research Forum. https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/abstract.aspx?ID=111964 .

Ekblom, P. (2002). From the source to the mainstream is uphill: The challenge of transferring knowledge of crime prevention through replication, innovation 5 design against crime paper the 5Is framework and anticipation. In N. Tilley (Ed.), Analysis for crime prevention, crime prevention studies (Vol. 13, pp. 131–203).

Goldstein, H. (1979). Improving Policing: A Problem-Oriented Approach. Univ. of Wisconsin Legal Studies Research Paper No. 1336. pp. 236–258. SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2537955 . Accessed 21 Jan 2018.

Goldstein, H. (1990). Problem-oriented policing create space independent publishing platform. ISBN-10: 1514809486.

Goldstein Award Winners (1993–2010), Center for Problem-Oriented Policing. http://www.popcenter.org/library/awards/goldstein/ . Accessed 21 Jan 2018.

Scott, M. S., & Kirby, S. (2012). Implementing POP: leading, structuring and managing a problem-oriented police agency . Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

Google Scholar

Sidebottom, A., & Tilley, N. (2011). Improving problem-oriented policing: the need for a new model. Crime Prevention and Community Safety, 13 (2), 79–101.

Article Google Scholar

Sherman, L., Gottfredson, D., MacKenzie D., Eck, J., Reuter, P. & Bushway, S. (1988). Preventing Crime: What Works, What Doesn’t, What’s Promising. National Institute of Justice Research Brief. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/171676.pdf . Accessed 14 Dec 2017.

Weisburd, D., Telep, C.W., Hinkle, J. C., & Eck, J. E. (2008). The effects of problem oriented policing on crime and disorder. https://www.campbellcollaboration.org/media/k2/attachments/1045_R.pdf . Accessed 21 Jan 2018.

Download references

Authors’ contributions

The article was co-authored by the two named authors. SB developed the original concept and developed the methodology and MM helped refine the ideas for practical implementation and provided additional content to the document. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Ethical approval and consent to participate, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

60 Fordwich Rise, London, SG14 2BN, UK

Steve Burton

Transport for London, London, UK

Mandy McGregor

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Steve Burton .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Burton, S., McGregor, M. Enhancing SARA: a new approach in an increasingly complex world. Crime Sci 7 , 4 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-018-0078-4

Download citation

Received : 18 September 2017

Accepted : 19 February 2018

Published : 01 March 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-018-0078-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Problem solving

- Transport policing

- Problem oriented policing

Crime Science

ISSN: 2193-7680

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Organizations

- Consultants

- Understand Your Team

- Increase Innovation

- Teach Collaboration Skills

- Get Certified

- About FourSight

Our new book, Good Team, Bad Team, is coming June 4!

Collaborate smarter. Solve problems faster.

Bring the FourSight ® assessment and problem-solving tools to your team, classroom, or organization. Find innovative solutions to the challenges that stand between you and your goals.

Help in-person and virtual groups collaborate

Quick assessment that’s easy to apply.

Tools to solve tough challenges

Reveal your team’s problem-solving superpowers and blind spots.

With Foursight, your team members gain a deeper understanding of their individual thinking styles and how they can best contribute to the group’s problem-solving success.

- Increase group effectiveness

- Reduce conflict

- Foster creative problem solving

- Spark innovation

- Support design thinking, lean and agile approaches

First, discover your own approach to problem-solving. Then get tools to do it better.

When you can see on a graph how your approach to solve a complex problem is unique, you can also see how it contributes to and may cause conflict on the team. Use the FourSight Thinking profile to discover your thinking preferences. Then get tools to help you work better, smarter, faster. Together.

.webp?width=122&height=121&name=foursight-clarify_1%20(1).webp)

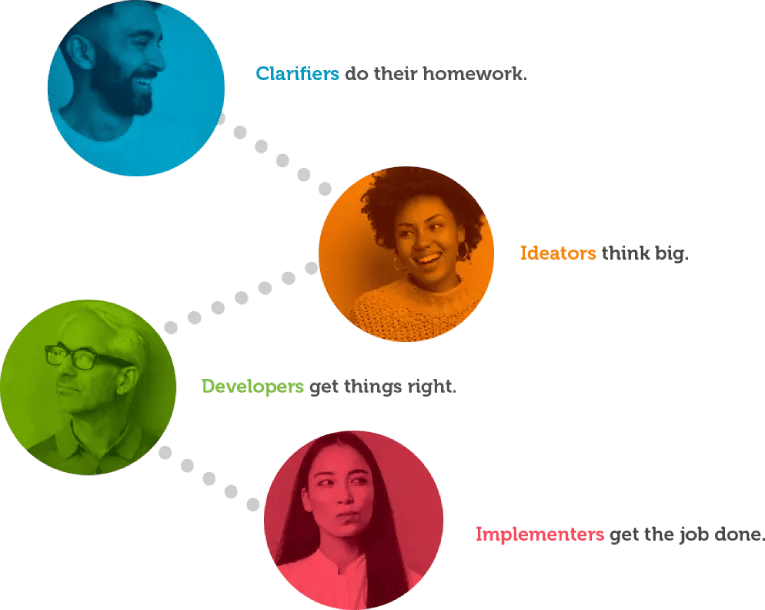

Clarifiers do their homework, but...

Clarifiers may suffer from analysis paralysis..

.webp?width=122&height=122&name=img-0001_1%20(1).webp)

Ideators think big, but...

Ideators sometimes overlook the details..

.webp?width=122&height=122&name=img-0002%20(1).webp)

Developers get things right, but...

Developers can get stuck working out the perfect solutions..

Implementers get the job done, but...

Implementers may leap to action too quickly., bring foursight ® to your team, organization, classroom or practice..

Work better together

Bring FourSight to your team and discover how to work better together to tackle big problems.

Increase innovation

When your organization needs speed, agility and innovation, FourSight can train your teams to deliver.

.webp?width=352&height=480&name=Rounded-Rectangle-1-copy_1%20(1).webp)

Teach collaboration

Teach FourSight in your classroom to set your students up for success in their teams and careers

.webp?width=352&height=480&name=01_1%20(1).webp)

Help clients achieve goals

Become a certified trainer of FourSight to coach clients in creative problem solving and innovation.

If you need more creative solutions, figure out which of the thinking archetypes need to put their heads together.

FourSight creates training tools to help individuals and teams solve problems.

FourSight has created a four-prong method used by businesses and in classrooms to help promote and demystify the creative process.

FourSight is the most efficient way to teach teams to be more innovative.

Ibm research study “creating, growing and sustaining efficient innovation teams”, “foursight is my 'go-to' lens for any work relating to teams and collaboration.”, —lesley d, od consultant, “your innovation class was the best training i’ve had in 20+ years at ups.”, alex o, new product development director, “foursight helped us harness the creative power of our organization.”, jim l, president + ceo, “the net payoff of using foursight is increased capacity for solving complex organizational challenges.”, david g, sr. director, global talent management, “simply put, foursight helps teams perform better.”, tim s., od consultant.

Success Stories

With its new course “Innovate Like an Entrepreneur,” UPS delivered innovation skills to marketing teams and focused employees’ problem solving skills on real UPS challenges.

IBM Research Study

Independent research conducted by a legendary inventor at IBM compared team structures and discovered the best way to train and sustain an innovative team.

Estee Lauder

The beauty giant transformed team outcomes with this team challenge program in Australia.

The Fastest Way to Improve Collaboration?

Download the chart "Communicating Across FourSight Preferences" and learn how to leverage the diverse thinkers on your team.

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Self-Assessment • 20 min read

How Good Is Your Problem Solving?

Use a systematic approach..

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Good problem solving skills are fundamentally important if you're going to be successful in your career.

But problems are something that we don't particularly like.

They're time-consuming.

They muscle their way into already packed schedules.

They force us to think about an uncertain future.

And they never seem to go away!

That's why, when faced with problems, most of us try to eliminate them as quickly as possible. But have you ever chosen the easiest or most obvious solution – and then realized that you have entirely missed a much better solution? Or have you found yourself fixing just the symptoms of a problem, only for the situation to get much worse?

To be an effective problem-solver, you need to be systematic and logical in your approach. This quiz helps you assess your current approach to problem solving. By improving this, you'll make better overall decisions. And as you increase your confidence with solving problems, you'll be less likely to rush to the first solution – which may not necessarily be the best one.

Once you've completed the quiz, we'll direct you to tools and resources that can help you make the most of your problem-solving skills.

How Good Are You at Solving Problems?

Instructions.

For each statement, click the button in the column that best describes you. Please answer questions as you actually are (rather than how you think you should be), and don't worry if some questions seem to score in the 'wrong direction'. When you are finished, please click the 'Calculate My Total' button at the bottom of the test.

Answering these questions should have helped you recognize the key steps associated with effective problem solving.

This quiz is based on Dr Min Basadur's Simplexity Thinking problem-solving model. This eight-step process follows the circular pattern shown below, within which current problems are solved and new problems are identified on an ongoing basis. This assessment has not been validated and is intended for illustrative purposes only.

Below, we outline the tools and strategies you can use for each stage of the problem-solving process. Enjoy exploring these stages!

Step 1: Find the Problem (Questions 7, 12)

Some problems are very obvious, however others are not so easily identified. As part of an effective problem-solving process, you need to look actively for problems – even when things seem to be running fine. Proactive problem solving helps you avoid emergencies and allows you to be calm and in control when issues arise.

These techniques can help you do this:

PEST Analysis helps you pick up changes to your environment that you should be paying attention to. Make sure too that you're watching changes in customer needs and market dynamics, and that you're monitoring trends that are relevant to your industry.

Risk Analysis helps you identify significant business risks.

Failure Modes and Effects Analysis helps you identify possible points of failure in your business process, so that you can fix these before problems arise.

After Action Reviews help you scan recent performance to identify things that can be done better in the future.

Where you have several problems to solve, our articles on Prioritization and Pareto Analysis help you think about which ones you should focus on first.

Step 2: Find the Facts (Questions 10, 14)

After identifying a potential problem, you need information. What factors contribute to the problem? Who is involved with it? What solutions have been tried before? What do others think about the problem?

If you move forward to find a solution too quickly, you risk relying on imperfect information that's based on assumptions and limited perspectives, so make sure that you research the problem thoroughly.

Step 3: Define the Problem (Questions 3, 9)

Now that you understand the problem, define it clearly and completely. Writing a clear problem definition forces you to establish specific boundaries for the problem. This keeps the scope from growing too large, and it helps you stay focused on the main issues.

A great tool to use at this stage is CATWOE . With this process, you analyze potential problems by looking at them from six perspectives, those of its Customers; Actors (people within the organization); the Transformation, or business process; the World-view, or top-down view of what's going on; the Owner; and the wider organizational Environment. By looking at a situation from these perspectives, you can open your mind and come to a much sharper and more comprehensive definition of the problem.

Cause and Effect Analysis is another good tool to use here, as it helps you think about the many different factors that can contribute to a problem. This helps you separate the symptoms of a problem from its fundamental causes.

Step 4: Find Ideas (Questions 4, 13)

With a clear problem definition, start generating ideas for a solution. The key here is to be flexible in the way you approach a problem. You want to be able to see it from as many perspectives as possible. Looking for patterns or common elements in different parts of the problem can sometimes help. You can also use metaphors and analogies to help analyze the problem, discover similarities to other issues, and think of solutions based on those similarities.

Traditional brainstorming and reverse brainstorming are very useful here. By taking the time to generate a range of creative solutions to the problem, you'll significantly increase the likelihood that you'll find the best possible solution, not just a semi-adequate one. Where appropriate, involve people with different viewpoints to expand the volume of ideas generated.

Tip: Don't evaluate your ideas until step 5. If you do, this will limit your creativity at too early a stage.

Step 5: Select and Evaluate (Questions 6, 15)

After finding ideas, you'll have many options that must be evaluated. It's tempting at this stage to charge in and start discarding ideas immediately. However, if you do this without first determining the criteria for a good solution, you risk rejecting an alternative that has real potential.

Decide what elements are needed for a realistic and practical solution, and think about the criteria you'll use to choose between potential solutions.

Paired Comparison Analysis , Decision Matrix Analysis and Risk Analysis are useful techniques here, as are many of the specialist resources available within our Decision-Making section . Enjoy exploring these!

Step 6: Plan (Questions 1, 16)

You might think that choosing a solution is the end of a problem-solving process. In fact, it's simply the start of the next phase in problem solving: implementation. This involves lots of planning and preparation. If you haven't already developed a full Risk Analysis in the evaluation phase, do so now. It's important to know what to be prepared for as you begin to roll out your proposed solution.

The type of planning that you need to do depends on the size of the implementation project that you need to set up. For small projects, all you'll often need are Action Plans that outline who will do what, when, and how. Larger projects need more sophisticated approaches – you'll find out more about these in the article What is Project Management? And for projects that affect many other people, you'll need to think about Change Management as well.

Here, it can be useful to conduct an Impact Analysis to help you identify potential resistance as well as alert you to problems you may not have anticipated. Force Field Analysis will also help you uncover the various pressures for and against your proposed solution. Once you've done the detailed planning, it can also be useful at this stage to make a final Go/No-Go Decision , making sure that it's actually worth going ahead with the selected option.

Step 7: Sell the Idea (Questions 5, 8)

As part of the planning process, you must convince other stakeholders that your solution is the best one. You'll likely meet with resistance, so before you try to “sell” your idea, make sure you've considered all the consequences.

As you begin communicating your plan, listen to what people say, and make changes as necessary. The better the overall solution meets everyone's needs, the greater its positive impact will be! For more tips on selling your idea, read our article on Creating a Value Proposition and use our Sell Your Idea Skillbook.

Step 8: Act (Questions 2, 11)

Finally, once you've convinced your key stakeholders that your proposed solution is worth running with, you can move on to the implementation stage. This is the exciting and rewarding part of problem solving, which makes the whole process seem worthwhile.

This action stage is an end, but it's also a beginning: once you've completed your implementation, it's time to move into the next cycle of problem solving by returning to the scanning stage. By doing this, you'll continue improving your organization as you move into the future.

Problem solving is an exceptionally important workplace skill.

Being a competent and confident problem solver will create many opportunities for you. By using a well-developed model like Simplexity Thinking for solving problems, you can approach the process systematically, and be comfortable that the decisions you make are solid.

Given the unpredictable nature of problems, it's very reassuring to know that, by following a structured plan, you've done everything you can to resolve the problem to the best of your ability.

This assessment has not been validated and is intended for illustrative purposes only. It is just one of many Mind Tool quizzes that can help you to evaluate your abilities in a wide range of important career skills.

If you want to reproduce this quiz, you can purchase downloadable copies in our Store .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

4 logical fallacies.

Avoid Common Types of Faulty Reasoning

Problem Solving

Add comment

Comments (2)

Afkar Hashmi

😇 This tool is very useful for me.

over 1 year

Very impactful

Gain essential management and leadership skills

Busy schedule? No problem. Learn anytime, anywhere.

Subscribe to unlimited access to meticulously researched, evidence-based resources.

Join today and take advantage of our 30% offer, available until May 31st .

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Latest Updates

Winning Body Language

Business Stripped Bare

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Nine ways to get the best from x (twitter).

Growing Your Business Quickly and Safely on Social Media

Managing Your Emotions at Work

Controlling Your Feelings... Before They Control You

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Key task analysis.

Focus on Your Development

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Decision Making

Member Podcast

- Creating Environments Conducive to Social Interaction

- Thinking Ethically: A Framework for Moral Decision Making

- Developing a Positive Climate with Trust and Respect

- Developing Self-Esteem, Confidence, Resiliency, and Mindset

- Developing Ability to Consider Different Perspectives

- Developing Tools and Techniques Useful in Social Problem-Solving

- Leadership Problem-Solving Model

- A Problem-Solving Model for Improving Student Achievement

Six-Step Problem-Solving Model

- Hurson’s Productive Thinking Model: Solving Problems Creatively

- The Power of Storytelling and Play

- Creative Documentation & Assessment

- Materials for Use in Creating “Third Party” Solution Scenarios

- Resources for Connecting Schools to Communities

- Resources for Enabling Students

weblink: http://www.yale.edu/bestpractices/resources/docs/problemsolvingmodel.pdf

This six-step model is designed for the workplace, but is easily adaptable to other settings such as schools and families. It emphasizes the cyclical , continuous nature of the problem-solving process . The model describes in detail the following steps:

Step One: Define the Problem

Step Two: Determine the Root Cause(s) of the Problem

Step Three: Develop Alternative Solutions

Step Four: Select a Solution

Step Five: Implement the Solution

Step Six: Evaluate the Outcome

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Assessment in the context of problem-based learning

Cees p. m. van der vleuten.

1 School of Health Professions Education, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, P.O. Box 616, 6200 MD Maastricht, The Netherlands

Lambert W. T. Schuwirth

2 Prideaux Centre for Research in Health Professions Education, College of Medicine and Public Health, Flinders University, Sturt Road, Bedford Park, SA 5042 Australia

Arguably, constructive alignment has been the major challenge for assessment in the context of problem-based learning (PBL). PBL focuses on promoting abilities such as clinical reasoning, team skills and metacognition. PBL also aims to foster self-directed learning and deep learning as opposed to rote learning. This has incentivized researchers in assessment to find possible solutions. Originally, these solutions were sought in developing the right instruments to measure these PBL-related skills. The search for these instruments has been accelerated by the emergence of competency-based education. With competency-based education assessment moved away from purely standardized testing, relying more heavily on professional judgment of complex skills. Valuable lessons have been learned that are directly relevant for assessment in PBL. Later, solutions were sought in the development of new assessment strategies, initially again with individual instruments such as progress testing, but later through a more holistic approach to the assessment program as a whole. Programmatic assessment is such an integral approach to assessment. It focuses on optimizing learning through assessment, while at the same gathering rich information that can be used for rigorous decision-making about learner progression. Programmatic assessment comes very close to achieving the desired constructive alignment with PBL, but its wide adoption—just like PBL—will take many years ahead of us.

Introduction

Since its inception, problem-based learning (PBL) has conquered the world (Donner and Bickley 1993 ). Its history is described in a number of publications (Schmidt 2012 ; Servant-Miklos 2019 ). What started in the mid-sixties at McMaster University as a radical break from lecture-based education (Barrows and Tamblyn 1980 ), turned out to be a successful didactic strategy which has since been increasingly copied by other schools. Originally, PBL had a high ideological identity. This meant that it was defined as a process with defined steps which had to be adhered to when practicing ‘true PBL’. Only later did it become clear that PBL aligned with insights and theories from educational and cognitive psychological research (Norman and Schmidt 1992 ; Dolmans et al. 2005 ; Neville 2009 ). PBL emphasized the need for problem-solving to train clinical reasoning (Norman 1988 ) and for long it had been assumed that the method itself would teach students to become generic clinical reasoners. This assumption fueled a long line of research on what constitutes (clinical) reasoning expertise (Schmidt and Rikers 2007 ). Through this, PBL became more scientifically grounded over the years.

Nowadays, the original ideological approach to PBL has calmed down and it can have many different manifestations. So, when schools claim to be using PBL it is not always clear what that exactly entails.

In our view that are some essential characteristics:

- The use of engaging tasks or problems as a starting point for learning

- Self-directed and self-regulated learning

- Working in groups of learners tackling these tasks

- The role of the teachers as a facilitator of this process

Many of these characteristics can be explained also by current insights from further educational theory. The use of meaningful tasks is an example of a whole task approach as is promoted by educational design theories (Merrienboer and Kirschner 2007 ). Collaborative learning theories underpin the use and the conditions for effective group learning (Johnson et al. 2007 ), while giving autonomy to learners in their learning process resonates with theories of motivation and self-determination (Deci and Ryan 2008 ). The widespread use of PBL is undoubtedly promoted by the scientific underpinning of the approach.

This leaves the question how to design assessment of learner achievements in the context of PBL? Constructive alignment has been suggested as a concept that expresses the extent to which the intended goals of the training program align with the overt and unexpected goals of the the assessment as espoused and experienced by all stakeholders (learners, staff and organization) (Biggs 1996 ). If there is a mismatch between the two, the assessment impact typically overrides the intended learning approach.

The dominant educational practice in assessment is a summative, modular approach, particularly assessing the more cognitive aspects. Learners typically progress from module to module, passing or failing standardized tests along the way. Unfortunately, many PBL schools use this approach as well, which logically leads to constructive misalignment in many cases.

To better understand this constructive misalignment, we find it helpful to identify two major frictions around assessment in a PBL context. The first is that PBL is assumed to promote more than purely the development of knowledge and skills. Such other abilities related not only to clinical reasoning and clinical decision-making, but also to more domain independent abilities such as communication, collaboration professionalism, etcetera. Despite the ongoing challenges in clearly defining these domain independent abilities they are generally seen as important and incorporated visibly in all the major competency frameworks (Anonymous 2000 ; Frank and Danoff 2007 ; GMC 2013 ). The perceived friction between what was generally assessed and what was aspired by PBL education approaches has led to many attempts to design more appropriate methods of assessment.

The second friction lies in the contradiction of requiring the learners to self-regulate their learning on the one hand, but at the same time they have to successfully pas set of teacher-led assessments or tests. Again, the concept of self-regulation of learning in the educational setting is not undisputed. For example, the ability of students to successfully self assess and subsequently direct their own learning is seriously doubted (Eva et al. 2004 ). Yet, there seems to be more agreement that after graduation doctors should be able to be lifelong learners and for this require having developed self-assessment and self-regulated learning ability. This conceptual friction has led to a quest of assessment strategies that better fit to PBL.

In this paper, we will discuss each of these frictions in more detail and some of the assessment developments that arose from this search for better constructive alignment. In doing so, we will also discuss other major developments in education and in assessment that are not related to PBL itself, but which have a major impact on how to deal with constructive alignment in PBL.

The quest for instrumentation

Clearly, PBL is aimed at promoting clinical reasoning, which logically led to the desire to develop instruments for the assessment of clinical reasoning, and subsequently to a vast amount of research and development in this area. A comprehensive overview on the developments on assessment of clinical reasoning is from Schuwirth et al. ( 2019 ).

Within the assessment literature, this started in the sixties with the use of paper simulations of patient problems (McGuire and Babbott 1967 ; McCarthy and Gonnella 1967 ). They were called Patient Management Problems (PMPs). A patient’s initial complaint was presented, and the learner had to navigate their way through the problem to arrive at the solutions. Each action taken was scored and these scores were considered to be an indication of a person’s clinical reasoning ability.

Several, counterintuitive, measurement problems with the method were found. First, experts did not agree on the optimal pathway through the simulation and assigned different credits to each decision. In other words, when different experts were presented with the same problem, they suggested different solution pathways.

Second, it was discovered that the scores of individual learners across patient problems was very low, in the order of 0.1–0.2. It became clear that clinical reasoning could not be measured as a generic and knowledge-independent trait. This was a first indication of what later has been called the problem of content specificity (Eva 2003 ). Content specificity was subsequently found to be innate to almost all assessment measurement. In order to arrive at a reproducible score in all assessment measurements, considerable sampling needs to be done across sources of variance; aspects that have a possible impact on the score such as content (problems, cases, items, orals, stations, etc.), assessors, (Van der Vleuten and Schuwirth 2005 ). The corollary of this that given that assessment time is limited, there is a need to be efficient with sampling. One of the developments were assessment methods with short scenarios or vignettes which were less complex, such as key-feature approach testing (Page et al. 1995 ) and or extended-matching items (Case and Swanson 1993 ). However, these instruments seemed to focus mainly on the outcome of the clinical reasoning process, the clinical decision making. The assessment of the reasoning process itself still remained a Holy Grail. Therefore, the search continued and some more specific clinical reasoning instruments were developed later, based on insights from the clinical expertise literature. One example is the Script Concordance Test (SCT) in which an ill-defined patient scenario unfolds itself and the learner has to indicate probabilities of their hypothesis of the problem (Lubarsky et al. 2011 ). Another format was an oral that also mimicked the PBL learning process, the so-called Triple Jump Exercise (Westmorland and Parsons 1995 ). It started with the presentation of a case in an oral setting (jump 1), some time for self-study on the case by the learner (jump 2) and a report of the finding in a next oral session (jump 3). The method was quite original but never has gained much popularity.

One of the currently proposed reasons why clinical decision making was easier to assess than clinical reasoning is an ontological difference: clinical decision making is a process that typically leads to one or a few defensibly correct answers whereas clinical reasoning is a process that is more unpredictable or complex and there can lead to multiple good answers depending on the situation (Durning et al. 2010 ). Both aspects are probably equally important for any competent clinician but the fundamental difference has fundamental implications for their assessment. If good clinical decision-making predictably leads to correct answers, it can typically be tested with structured and standardised assessments. That is why the key feature approach to assessment and extended matching items have been found to be valid (Case and Swanson 1993 ; Bordage et al. 1995 ). When the required outcome is unpredictable and there are multiple good answers depending on the situation the assessment cannot be predefined and has to happen in the here and now. One example of this challenge is illustrated by the concerns around script concordance tests, where the stimulus—what the question asks—is divergent in nature but the scoring is convergent and hence does not sit well with the complexity of clinical reasoning (Lineberry et al. 2013 ). This has led to a renewed interest in researching the role of human judgment in the assessment of clinical reasoning (Govaerts et al. 2012 ; Govaerts et al. 2011 ; Gingerich et al. 2014 ). Still, the common mechanism for assessing clinical decision making and clinical reasoning is to use authentic but efficient clinical tasks, usually in the form of patient scenario’s, as a stimulus for obtaining responses.

There can be many variations to do this in an assessment practice. Schuwirth et al. conclude: “Finally, because there are so many ways to assess clinical reasoning, and no single measure is the best measure, the choice is really yours.” (Schuwirth et al. 2019 , p. 413) and will depend on your resources, the appeal of the approach and the potential learning value of the method of choice. Many modern approaches to clinical decision-making use patient scenarios in efficient question formats (Case and Swanson 2002 ). By using efficient methods for clinical reasoning and decision-making part of the alignment friction may be alleviated.

However, PBL was also assumed to promote other abilities than knowledge and skills, such as collaboration, communication and regulated learning ability and professionalism. Therefore, initiatives were undertaken to develop instruments for the assessment of these abilities. At McMaster University, where PBL started, initially tutor-based assessment of the learners was used. Actually, during the first years these were the only assessments. Later, other, more standardized assessments were added for various reasons. One of those was that the tutor evaluations did not predict licensing exam performance (Keane et al. 1996 ). One can question whether this inability to predict performance on a licensing exam is an indication that the assumption of good self-regulated learning being sufficient to predict the development of competence is incorrect or whether the early implementation of purely human judgement-based assessment was still immature. Since that time, much has been learned about using human judgement in assessment, partly from the literature on heuristics and biases (Plous 1993 ) and from naturalistic decision-making (Gigerenzer and Goldstein 1996 ) and in the context of assessment of medical competence (Govaerts et al. 2011 , 2013a ; Gingerich 2015 ). At Maastricht University for instance, the second university to adopt PBL, the assessment of professional behavior received a prominent place (Van Luijk et al. 2000 ; Van Mook et al. 2009 ). These assessments were based on a judgement and narrative feedback from the tutor and peers combined with a self-assessment on behavior pertaining to group work around the task, in relation to others in the group and to oneself. Essentially, these were early examples of the use of professional judgment to assess more complex abilities. A salient distinction between both developments is that in the initial years at McMaster the tutor evaluations were used as the predictor for medical competence as a whole, whereas the Maastricht development entailed a much closer alignment between purpose of assessment and process. Yet, the downside of this was a persistence of the compartmentalisation of the assessment of competence.

Another development in education, competency-based medical education (CBME), proposed a more integrative view on competence, in which all types of abilities were expected to interact with each other. So for assessment, this required a more integrative view. In the CBME literaturea ‘competency’ is generally defined the integration of knowledge, skills and attitudes to fulfil a complex professional task (Albanese et al. 2008 ), which instigated a major orientation shift in educational thinking. CBME challenged education to define the outcomes of education as: “What is it that learners after completing the training program are able to do?” Different organizations developed competency frameworks (Anonymous 2000 ; Frank and Danoff 2007 ; GMC 2013 ). These frameworks were constructed with wide stakeholder input and were strongly influenced by the expected needs of future healthcare. Competency frameworks have had a profound impact on structuring curricula, but they also influenced the assessment developments and their research. The commonality across these frameworks that they emphasize complex abilities, such as communication, collaboration, professionalism, health advocacy, systems-based practice, etcetera, more strongly. These abilities are important because they were found predictive for success and failure in the labor market (Papadakis et al. 2005 ; Semeijn et al. 2006 ; Van Mook et al. 2012 ). Complex abilities cannot be easily defined, though and neither can they be easily trained in a short course ending with an exam. These competencies usually require vertical learning lines in a curriculum and develop longitudinally. Through its increase in popularity CBME challenged the traditional measurement perspective of assessment and stimulated developers and researchers to start ‘assessing the unmeasurable’. it is generally help that these complex abilities cannot be measured at one point in time but can only be assessed through professional judgments of habitual performance in more or less authentic educational or clinical settings. This means that they can hardly be captured in a simple checklist and when tried, the assessment is trivialized (Van der Vleuten et al. 2010 ). Thus, the assessment literature moved towards the top of Miller’s pyramid (Miller 1990 ): the assessment of performance using unstandardized measures that strongly rely on more subjective sources of information (Kogan et al. 2009 ). This did not negate that every student is entitled to a fair and equitable outcome of the assessment, but not to exactly the same process to reach at outcome. This conceptual shift in thinking was essential in addressing the friction between self-regulation and self-direction of learning in PBL in the traditional standardised assessment.

Another major consequence of the attention to CBME is the issue of longitudinality. Looking at growth across time is a fundamental challenge for our classical approach of a modularised assessment system. What originally were early and perhaps marginal attempts in PBL schools to assess complex abilities gained considerable attention through the shift towards CBME.

We are still in the midst of understanding the consequences of these developments. One of the obvious implications is that in workplace-based assessment the observation and scoring have to happen simultaneously. This is different to, for instance, written examinations where a whole series of subjective judgements (what is the curriculum, what is the blueprint what topics to questions, what items to produce, what standards to set?) precedes the collection of performance data (which can be even done by a computer program). This requirement of real-time observation and scoring required considerably more assessment literacy from the assessor and could not simply be solved by more elaborate rubrics (Popham 2009 ; Valentine and Schuwirth 2019 ).

What is further evident, is that more attention is given to assessment from an education perspective, rather than from the dominant discourse around psychometrics in standardized assessment technology, i.e. in the first three layers of the pyramid (Schuwirth and Ash 2013 ). The learner and the utility of assessment to inform learning became more central (Kogan et al. 2017 ). Watling and Ginsburg posited that we are on a discovery journey on understanding the right “alchemy” between assessment and learning (Watling and Ginsburg 2019 ). Some of the recent insights include that medicine is a relatively poor feedback environment (Watling et al. 2013b ) in which it differs substantially and surprisingly from other high-performance domains. Feedback itself has been extensively studied (Van de Ridder et al. 2015 ; Bing-You et al. 2017 ). A fundamental finding is that feedback must stem from a credible source (Watling et al. 2012 ), and it must be logical, coherent and plausible as well as constructive. Logically, poorly given feedback will have limited—or even negative—impact. Another finding showed that in highly summative settings, learners are less inclined to engage with feedback (Harrison et al. 2016 ). Perhaps the most important implication is that scores and grades have considerable limitations as information conveyers. Qualitative and narrative information have much more meaning than scores, particularly when complex abilities are being assessed (Ginsburg et al. 2013 ). For instance, Ginsburg et al. showed more measurement information to be found in narrative data than in quantitative data (Ginsburg et al. 2017 ) and that residents were well able to read between the lines even when the feedback was generally positively framed (Ginsburg et al. 2015 ). The ample attention to feedback and learning has produced concrete and helpful suggestions around what to do in assessment, what not to do and what we don’t yet know (Lefroy et al. 2015 ). In recent years, the attention has shifted from a process of giving feedback to the importance of trusted social relationships (Ramani et al. 2019 ). Ideally, feedback is a dialogue either in action, based on direct observation of a clinical event, or on action, over a longer period of time (Van der Vleuten and Verhoeven 2013 ).

The same holds for self-directed learning; self-directed learning requires educational scaffolding, for example through an ongoing dialogue with a trusted person. The literature on mentoring is shows early positive effects (Driessen and Overeem 2013 ).

In all, CBME has forced the assessment literature into exploring and developing better work-based assessment and to rethink our strategies around assessment and learning (Govaerts et al. 2013b ). It clearly is about the right alchemy. Assessment should have an obvious learning function through providing the learner with meaningful feedback. Feedback use is to be scaffolded with feedback follow-up or through dialogues with entrusted persons with a growth mindset. The culture of a clinical setting or a department is over overriding importance as it conveys the strongest messages to the learner about what is expected and what is sanctioned (Watling et al. 2013a ; Ramani et al. 2017 ). Creating an assessment culture with a growth mindset in which assessment information is used to promote better learning and growth and development. Although these concepts seem to be reasonably developed in the literature, the actual practical implementation is not always easy. At the coalface, there are still fundamental conceptions of so-called naïve beliefs that contravene the literature (Vosniadou 1994 ); the non-domain specific abilities are labelled ‘soft’ skills and are deemed more peripheral aspects of medical competence and often too hard to assess, and the notion of lifelong learning seems to be at odds with the notion of licensing and credentialling at a certain point in time.

Nevertheless, the interplay between learning, assessment of complex abilities and self-directed learning are elements which are central to the CBME movement and also pivotal for assessment in PBL.

The quest for assessment strategies

PBL seeks to foster a deep learning strategy, focused on conceptual understanding. Assessment strategies to promote such learning strategies haves been on the agenda since the beginning of PBL. Probably, the Triple Jump Exercise mentioned earlier is an example of an approach to promote deeper understanding by mimicking the PBL learning cycle.

Another alternative assessment strategy that has a long history in PBL is progress testing (Schuwirth and van der Vleuten 2012 ). A progress test is a comprehensive written test—often with vignette based items—that represents the end objectives of the curriculum, comparable to a final examination, so in fact contains relevant questions out of the whole domain of functional medical knowledge. That test is administered to all the learners from all years in a program, but of course with different standards per year class. The test is repeated a number of times per year, each with new questions but with the same content blueprint. The results on the individual tests are combined to produce growth curves and performance predictions. This form of testing started in 1977 in Maastricht. The main purpose was to avoid test-directed studying. It is very difficult to specifically prepare for a progress test since anything might be asked. But, if a learner studies regularly in the PBL system most likely sufficient growth will occur automatically. Therefore, there is no need to cram or to memorize; actually it is a counter-productive preparation strategy (Van Til 1998 ). Due to its longitudinal nature—and especially in context where several medical schools collaborate and jointly produce progress tests, such as Germany, the UK, Italy and Brazil, the progress test, provides a wealth of information for individual students about their own learning and for schools to compare their performance with other schools

Longitudinal assessment is also assumed to be a better predictor of future performance. From a PBL philosophy of educating lifelong learners, this is important. Progress test predicts for instance performance on licensing examinations (Norman et al. 2010 ). When the University of McMaster adopted progress testing it was a valuable addition to existing tutor evaluations. This kind knowledge testing without the side effect of test-directed studying and that is predictive for licensure performance fitted their PBL approach hand-in-glove. From a strategic perspective, the interesting question is what in existing assessment programs may be replaced with progress testing. There are schools that rely exclusively on progress testing in the cognitive domain (Ricketts et al. 2009 ) and it is easily conceivable how many resources would be saved if no other knowledge exams were needed. Progress testing as a strategy of assessment has gained a definite place in the context of PBL. It reinforces many of the intentions of PBL and has proved itself practically and empirically.

A wider assessment strategy, is programmatic assessment. Programmatic assessment looks strategically to the assessment program as a whole (Schuwirth and Van der Vleuten 2011 ; Van der Vleuten et al. 2012 ). The ground rules in programmatic assessment are:

- Every (part of an) assessment is but a data-point

- Every data-point is optimized for learning by giving meaningful feedback to the learner

- Pass/fail decisions are not given on a single data-point

- There is a mix of methods of assessment

- The choice of method depends on the educational justification for using that method

- The distinction between summative and formative is replaced by a continuum of stakes

- Stake and decision-making learner progress are proportionally related to the stakes

- Assessment information is triangulated across data-points towards a competency framework

- High-stakes decisions (promotion, graduation) are made in competence committees

- Intermediate decisions are made with the purpose of informing the learner on their progress

- Learners have a recurrent learning meetings with (faculty) mentors using a self-analysis of all assessment data

Programmatic assessment requires an integral design of assessment in a program. Deliberate choices are made for methods of assessment, each chosen to maximally align with the intended learning goals. Learning tasks themselves may also be considered as contributing assessment tasks. For example, writing a critical appraisal on a clinical problem as part of an EBM track can be a data-point. From a conceptual point the assessment aligns maximally with the educational objectives. Any individual data point is never used to make high-stakes decisions (Van der Vleuten and Schuwirth 2005 ). That way, by taking out the summative “sting” out of each individual assessment, learners may concentrate on a learning orientation rather than trying to game of summative assessment. Self-directed learning is promoted through regular data-driven self-assessment and planning of learning, reinforced and supported by a trusted person that follows the learner in time (usually across years of training). Data points need to be rich in nature. When quantitative, the richness lies usually in feedback reports on subdomains and comparative information is given to a refence group. When qualitative, the richness lies in the quality of the narrative being provided. The use of professional judgment (by faculty, coworkers, peers or patients) and direct observation are strongly promoted and supported by capacity building processes in programmatic assessment. Decision-making becomes robust by triangulating and aggregating information across data-points. Since the information across data points is a combination of quantitative and qualitative data, decision making cannot be algorithmic or statistical, and human judgment is indispensable. Any high-stakes decision is rendered robust by using independent decision committees that arrive at their decisions by using rich information and reaching consensus (Hauer et al. 2016 ), when needed through iterative consultative processes. Procedural strategies derived from qualitative research are used to build the trustworthiness of the competence committee decision (Driessen et al. 2005 ; Van der Vleuten et al. 2010 ). For example, the committee will elaborately deliberate and motivate when there is doubt about the decision to be made. Programmatic assessment has been implemented in a number of undergraduate (Dannefer and Henson 2007 ; Wilkinson et al. 2011 ; Heeneman et al. 2015 ; Bok et al. 2013 ; Jamieson et al. 2017 ) and postgraduate settings (Chan and Sherbino 2015 ; Hauff et al. 2014 ). Its practical proof of concept has been produced, and there is considerable research ongoing on programmatic assessment [see Van der Vleuten et al. (in press) for a summary]. However, it will take many more years to fully scientifically underpin this integrative and knowledge of doodle approach to assessment. The biggest challenge is securing sufficient buy-in from faculty and students. Programmatic assessment requires a different mindset from the people involved. It is an escape from the traditional summative assessment paradigm. The process of moving towards programmatic assessment from traditional assessment practice as a deep conceptual mind shift bears striking similarities to the challenges PBL faced when it sought to supplement or replace traditional lecture-based curricula. As such, one could argue there is even a constructive alignment with respect to the change process.

Assessment in the context of PBL is driven by the need for constructive alignment between intentions of PBL and assessment. The classic summative paradigm with end-of-unit examinations does not really fit well to PBL. Although an initial search for instruments relevant for PBL may have produced some promising developments, it has become clear that no single instrument can unveil the whole picture. This has been a general conclusion in the assessment literature for any given training program (Van der Vleuten et al. 2010 ). Constructive alignment is best achieved through an integrative approach to assessment (Norcini et al. 2018 ; Eva et al. 2016 ) and for this to be attained a breach with the traditional summative approach is required. Programmatic assessment is such an example. In essence, it is similar to the idea of progress testing, but it incorporates all competencies and the assessment program as a whole. Like with all innovations, it will take time before it will be adopted more widely in the various PBL training programs. This is not unexpected as PBL itself took many years before wide-scale adoption occurred and many years of research to better understand it. This will also be the case with a more holistic view on assessment where assessment not only drives learning but learning drives assessment. Just like in PBL we will see many different manifestations or “hybrids” in system wide approaches to assessment. However, slowly and many years after the start of PBL, assessment has an answer to the needs of PBL.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Cees P. M. van der Vleuten, Phone: +31433885725, Email: [email protected] .

Lambert W. T. Schuwirth, Phone: +61 8 7221 8807 .

- Albanese MA, et al. Defining characteristics of educational competencies. Medical Education. 2008; 42 (3):248–255. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anonymous (2000). ACGME outcome project. Retrieved 30 October 2003, from http://www.acgme.org/Outcome/ .

- Barrows HS, Tamblyn R. Problem-based learning: An approach to medical education. New York: Springer; 1980. [ Google Scholar ]

- Biggs JB. Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education. 1996; 32 (3):347–364. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bing-You R, et al. Feedback for learners in medical education: What is known? A scoping review. Academic Medicine. 2017; 92 (9):1346–1354. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bok HG, et al. Programmatic assessment of competency-based workplace learning: When theory meets practice. BMC Medical Education. 2013; 13 (1):123. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bordage G, et al. Content validation of key features on a national examination of clinical decision-making skills. Academic Medicine. 1995; 70 (4):276–281. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Case SM, Swanson DB. Extended-macthing items: A practical alternative to free response questions. Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 1993; 5 (2):107–115. [ Google Scholar ]

- Case SM, Swanson DB. Constructing written test questions for the basic and clinical sciences. Philadelphia: National Board of Medical Examiners; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chan T, Sherbino J. The McMaster modular assessment program (McMAP): A theoretically grounded work-based assessment system for an emergency medicine residency program. Academic Medicine. 2015; 90 (7):900–905. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dannefer EF, Henson LC. The portfolio approach to competency-based assessment at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine. Academic Medicine. 2007; 82 (5):493–502. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne. 2008; 49 (3):182. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dolmans DH, et al. Problem-based learning: Future challenges for educational practice and research. Medical Education. 2005; 39 (7):732–741. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Donner RS, Bickley H. Problem-based learning in American medical education: An overview. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association. 1993; 81 (3):294. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Driessen EW, Overeem K. Mentoring. In: Walsh K, editor. Oxford textbook of medical education. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 265–284. [ Google Scholar ]

- Driessen E, et al. The use of qualitative research criteria for portfolio assessment as an alternative to reliability evaluation: A case study. Medical Education. 2005; 39 (2):214–220. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Durning SJ, et al. Perspective: Redefining context in the clinical encounter: Implications for research and training in medical education. Academic Medicine. 2010; 85 (5):894–901. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eva KW. On the generality of specificity. Medical Education. 2003; 37 (7):587–588. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eva KW, et al. How can i know what i don’t know? Poor self assessment in a well-defined domain. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2004; 9 (3):211–224. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eva KW, et al. Towards a program of assessment for health professionals: From training into practice. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2016; 21 (4):897–913. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frank JR, Danoff D. The CanMEDS initiative: Implementing an outcomes-based framework of physician competencies. Medical Teacher. 2007; 29 (7):642–647. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gigerenzer G, Goldstein DG. Reasoning the fast and frugal way: Models of bounded rationality. Psychological Review. 1996; 103 (4):650. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gingerich, A. (2015). Questioning the rater idiosyncrasy explanation for error variance by searching for multiple signals within the noise . Maastricht University.

- Gingerich A, et al. More consensus than idiosyncrasy: Categorizing social judgments to examine variability in Mini-CEX ratings. Academic Medicine. 2014; 89 (11):1510–1519. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ginsburg S, et al. Do in-training evaluation reports deserve their bad reputations? A study of the reliability and predictive ability of ITER scores and narrative comments. Academic Medicine. 2013; 88 (10):1539–1544. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ginsburg S, et al. Reading between the lines: Faculty interpretations of narrative evaluation comments. Medical Education. 2015; 49 (3):296–306. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ginsburg S, et al. The hidden value of narrative comments for assessment: A quantitative reliability analysis of qualitative data. Academic Medicine. 2017; 92 (11):1617–1621. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- General Medical Council. (2013). Good medical practice. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/good-medical-practice---english-1215_pdf-51527435.pdf . Accessed 13 Sept 2019.

- Govaerts MJB, Van der Vleuten CPM. Validity in work-based assessment: Expanding our horizons. Medical Education. 2013; 47 (12):1164–1174. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Govaerts MJ, et al. Workplace-based assessment: Effects of rater expertise. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2011; 16 (2):151–165. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Govaerts MJ, et al. Workplace-based assessment: Raters’ performance theories and constructs. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2012; 18 (3):375–396. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Govaerts M, et al. Workplace-based assessment: Raters’ performance theories and constructs. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2013; 18 (3):375–396. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Harrison CJ, et al. Factors influencing students’ receptivity to formative feedback emerging from different assessment cultures. Perspectives on medical education. 2016; 5 (5):276–284. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hauer KE, et al. Ensuring resident competence: A narrative review of the literature on group decision making to inform the work of clinical competency committees. Journal of graduate medical education. 2016; 8 (2):156–164. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hauff SR, et al. Programmatic assessment of level 1 milestones in incoming interns. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2014; 21 (6):694–698. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Heeneman S, et al. The impact of programmatic assessment on student learning: Theory versus practice. Medical Education. 2015; 49 (5):487–498. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jamieson J, et al. Designing programmes of assessment: A participatory approach. Medical Teacher. 2017; 39 (11):1182–1188. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson DW, et al. The state of cooperative learning in postsecondary and professional settings. Educational Psychology Review. 2007; 19 :15–29. [ Google Scholar ]

- Keane D, et al. Introducing progress testing in a traditional problem based curriculum. Academic Medicine. 1996; 71 (9):1002–1007. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kogan JR, et al. Guidelines: The do’s, don’ts and don’t knows of direct observation of clinical skills in medical education. Perspectives on Medical Education. 2017; 6 :1–20. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kogan JR, et al. Tools for direct observation and assessment of clinical skills of medical trainees: A systematic review. JAMA. 2009; 302 (12):1316–1326. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lefroy J, et al. Guidelines: The do’s, don’ts and don’t knows of feedback for clinical education. Perspectives on medical education. 2015; 4 (6):284–299. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lineberry M, et al. Threats to validity in the use and interpretation of script concordance test scores. Medical Education. 2013; 47 (12):1175–1183. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lubarsky S, et al. Script concordance testing: A review of published validity evidence. Medical Education. 2011; 45 (4):329–338. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McCarthy WH, Gonnella JS. The simulated patient management problem: A technique for evaluating and teaching clinical competence. Medical Education. 1967; 1 (5):348–352. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McGuire CH, Babbott D. Simulation technique in the measurement of problem-solving skills 1. Journal of Educational Measurement. 1967; 4 (1):1–10. [ Google Scholar ]

- Merrienboer J, Kirschner P. Ten steps to complex learning. A systematic approach to four-component instructional design. New York/London: Routledge; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Academic Medicine. 1990; 65 (9):S63–s67. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Neville AJ. Problem-based learning and medical education forty years on. Medical Principles and Practice. 2009; 18 (1):1–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Norcini J, et al. 2018 consensus framework for good assessment. Medical Teacher. 2018; 40 (11):1102–1109. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Norman GR. Problem-solving skills, solving problems and problem-based learning. Medical Education. 1988; 22 :270–286. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Norman GR, Schmidt HG. The psychological basis of problem-based learning: A review of the evidence. Academic Medicine. 1992; 67 (9):557–565. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Norman G, et al. Assessment steers learning down the right road: Impact of progress testing on licensing examination performance. Medical Teacher. 2010; 32 (6):496–499. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Page G, et al. Developing key-feature problems and examinations to assess clinical decision-making skills. Academic Medicine. 1995; 70 (3):194–201. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Papadakis MA, et al. Disciplinary action by medical boards and prior behavior in medical school. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005; 353 (25):2673–2682. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Plous S. The psychology of judgment and decision making. New York: Mcgraw-Hill Book Company; 1993. [ Google Scholar ]

- Popham WJ. Assessment literacy for teachers: Faddish or fundamental? Theory into Practice. 2009; 48 (1):4–11. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ramani S, et al. “It’s just not the culture”: A qualitative study exploring residents’ perceptions of the impact of institutional culture on feedback. Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 2017; 29 (2):153–161. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ramani S, et al. Twelve tips to promote a feedback culture with a growth mind-set: Swinging the feedback pendulum from recipes to relationships. Medical Teacher. 2019; 41 :1–7. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ricketts C, et al. Standard setting for progress tests: Combining external and internal standards. Medical Education. 2009; 43 (6):589–593. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schmidt HG. A brief history of problem-based learning. One-day, one-problem. Berlin: Springer; 2012. pp. 21–40. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schmidt HG, Rikers RM. How expertise develops in medicine: Knowledge encapsulation and illness script formation. Medical Education. 2007; 41 (12):1133–1139. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schuwirth L, Ash J. Assessing tomorrow’s learners: In competency-based education only a radically different holistic method of assessment will work. Six things we could forget. Medical Teacher. 2013; 35 (7):555–559. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schuwirth LWT, Van der Vleuten CPM. Programmatic assessment: From assessment of learning to assessment for learning. Medical Teacher. 2011; 33 (6):478–485. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schuwirth LW, van der Vleuten CP. The use of progress testing. Perspectives on Medical Education. 2012; 1 (1):24–30. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schuwirth L, et al. Assessing clinical reasoning. In: Higgs J, Jensen G, Loftus S, Christensen N, et al., editors. Clinical reasoning in the health professions. Edingburgh: Elsevier; 2019. pp. 407–415. [ Google Scholar ]

- Semeijn JH, et al. Competence indicators in academic education and early labour market success of graduates in health sciences. Journal of education and work. 2006; 19 (4):383–413. [ Google Scholar ]

- Servant-Miklos, V. F. C. (2019). A Revolution in its own right: How maastricht university reinvented problem- based learning. Health Professions Education . 10.1016/j.hpe.2018.12.005.