Research Question 101 📖

Everything you need to know to write a high-quality research question

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2023

If you’ve landed on this page, you’re probably asking yourself, “ What is a research question? ”. Well, you’ve come to the right place. In this post, we’ll explain what a research question is , how it’s differen t from a research aim, and how to craft a high-quality research question that sets you up for success.

Research Question 101

What is a research question.

- Research questions vs research aims

- The 4 types of research questions

- How to write a research question

- Frequently asked questions

- Examples of research questions

As the name suggests, the research question is the core question (or set of questions) that your study will (attempt to) answer .

In many ways, a research question is akin to a target in archery . Without a clear target, you won’t know where to concentrate your efforts and focus. Essentially, your research question acts as the guiding light throughout your project and informs every choice you make along the way.

Let’s look at some examples:

What impact does social media usage have on the mental health of teenagers in New York?

How does the introduction of a minimum wage affect employment levels in small businesses in outer London?

How does the portrayal of women in 19th-century American literature reflect the societal attitudes of the time?

What are the long-term effects of intermittent fasting on heart health in adults?

As you can see in these examples, research questions are clear, specific questions that can be feasibly answered within a study. These are important attributes and we’ll discuss each of them in more detail a little later . If you’d like to see more examples of research questions, you can find our RQ mega-list here .

Research Questions vs Research Aims

At this point, you might be asking yourself, “ How is a research question different from a research aim? ”. Within any given study, the research aim and research question (or questions) are tightly intertwined , but they are separate things . Let’s unpack that a little.

A research aim is typically broader in nature and outlines what you hope to achieve with your research. It doesn’t ask a specific question but rather gives a summary of what you intend to explore.

The research question, on the other hand, is much more focused . It’s the specific query you’re setting out to answer. It narrows down the research aim into a detailed, researchable question that will guide your study’s methods and analysis.

Let’s look at an example:

Research Aim: To explore the effects of climate change on marine life in Southern Africa.

Research Question: How does ocean acidification caused by climate change affect the reproduction rates of coral reefs?

As you can see, the research aim gives you a general focus , while the research question details exactly what you want to find out.

Need a helping hand?

Types of research questions

Now that we’ve defined what a research question is, let’s look at the different types of research questions that you might come across. Broadly speaking, there are (at least) four different types of research questions – descriptive , comparative , relational , and explanatory .

Descriptive questions ask what is happening. In other words, they seek to describe a phenomena or situation . An example of a descriptive research question could be something like “What types of exercise do high-performing UK executives engage in?”. This would likely be a bit too basic to form an interesting study, but as you can see, the research question is just focused on the what – in other words, it just describes the situation.

Comparative research questions , on the other hand, look to understand the way in which two or more things differ , or how they’re similar. An example of a comparative research question might be something like “How do exercise preferences vary between middle-aged men across three American cities?”. As you can see, this question seeks to compare the differences (or similarities) in behaviour between different groups.

Next up, we’ve got exploratory research questions , which ask why or how is something happening. While the other types of questions we looked at focused on the what, exploratory research questions are interested in the why and how . As an example, an exploratory research question might ask something like “Why have bee populations declined in Germany over the last 5 years?”. As you can, this question is aimed squarely at the why, rather than the what.

Last but not least, we have relational research questions . As the name suggests, these types of research questions seek to explore the relationships between variables . Here, an example could be something like “What is the relationship between X and Y” or “Does A have an impact on B”. As you can see, these types of research questions are interested in understanding how constructs or variables are connected , and perhaps, whether one thing causes another.

Of course, depending on how fine-grained you want to get, you can argue that there are many more types of research questions , but these four categories give you a broad idea of the different flavours that exist out there. It’s also worth pointing out that a research question doesn’t need to fit perfectly into one category – in many cases, a research question might overlap into more than just one category and that’s okay.

The key takeaway here is that research questions can take many different forms , and it’s useful to understand the nature of your research question so that you can align your research methodology accordingly.

How To Write A Research Question

As we alluded earlier, a well-crafted research question needs to possess very specific attributes, including focus , clarity and feasibility . But that’s not all – a rock-solid research question also needs to be rooted and aligned . Let’s look at each of these.

A strong research question typically has a single focus. So, don’t try to cram multiple questions into one research question; rather split them up into separate questions (or even subquestions), each with their own specific focus. As a rule of thumb, narrow beats broad when it comes to research questions.

Clear and specific

A good research question is clear and specific, not vague and broad. State clearly exactly what you want to find out so that any reader can quickly understand what you’re looking to achieve with your study. Along the same vein, try to avoid using bulky language and jargon – aim for clarity.

Unfortunately, even a super tantalising and thought-provoking research question has little value if you cannot feasibly answer it. So, think about the methodological implications of your research question while you’re crafting it. Most importantly, make sure that you know exactly what data you’ll need (primary or secondary) and how you’ll analyse that data.

A good research question (and a research topic, more broadly) should be rooted in a clear research gap and research problem . Without a well-defined research gap, you risk wasting your effort pursuing a question that’s already been adequately answered (and agreed upon) by the research community. A well-argued research gap lays at the heart of a valuable study, so make sure you have your gap clearly articulated and that your research question directly links to it.

As we mentioned earlier, your research aim and research question are (or at least, should be) tightly linked. So, make sure that your research question (or set of questions) aligns with your research aim . If not, you’ll need to revise one of the two to achieve this.

FAQ: Research Questions

Research question faqs, how many research questions should i have, what should i avoid when writing a research question, can a research question be a statement.

Typically, a research question is phrased as a question, not a statement. A question clearly indicates what you’re setting out to discover.

Can a research question be too broad or too narrow?

Yes. A question that’s too broad makes your research unfocused, while a question that’s too narrow limits the scope of your study.

Here’s an example of a research question that’s too broad:

“Why is mental health important?”

Conversely, here’s an example of a research question that’s likely too narrow:

“What is the impact of sleep deprivation on the exam scores of 19-year-old males in London studying maths at The Open University?”

Can I change my research question during the research process?

How do i know if my research question is good.

A good research question is focused, specific, practical, rooted in a research gap, and aligned with the research aim. If your question meets these criteria, it’s likely a strong question.

Is a research question similar to a hypothesis?

Not quite. A hypothesis is a testable statement that predicts an outcome, while a research question is a query that you’re trying to answer through your study. Naturally, there can be linkages between a study’s research questions and hypothesis, but they serve different functions.

How are research questions and research objectives related?

The research question is a focused and specific query that your study aims to answer. It’s the central issue you’re investigating. The research objective, on the other hand, outlines the steps you’ll take to answer your research question. Research objectives are often more action-oriented and can be broken down into smaller tasks that guide your research process. In a sense, they’re something of a roadmap that helps you answer your research question.

Need some inspiration?

If you’d like to see more examples of research questions, check out our research question mega list here . Alternatively, if you’d like 1-on-1 help developing a high-quality research question, consider our private coaching service .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Good Research Question (w/ Examples)

What is a Research Question?

A research question is the main question that your study sought or is seeking to answer. A clear research question guides your research paper or thesis and states exactly what you want to find out, giving your work a focus and objective. Learning how to write a hypothesis or research question is the start to composing any thesis, dissertation, or research paper. It is also one of the most important sections of a research proposal .

A good research question not only clarifies the writing in your study; it provides your readers with a clear focus and facilitates their understanding of your research topic, as well as outlining your study’s objectives. Before drafting the paper and receiving research paper editing (and usually before performing your study), you should write a concise statement of what this study intends to accomplish or reveal.

Research Question Writing Tips

Listed below are the important characteristics of a good research question:

A good research question should:

- Be clear and provide specific information so readers can easily understand the purpose.

- Be focused in its scope and narrow enough to be addressed in the space allowed by your paper

- Be relevant and concise and express your main ideas in as few words as possible, like a hypothesis.

- Be precise and complex enough that it does not simply answer a closed “yes or no” question, but requires an analysis of arguments and literature prior to its being considered acceptable.

- Be arguable or testable so that answers to the research question are open to scrutiny and specific questions and counterarguments.

Some of these characteristics might be difficult to understand in the form of a list. Let’s go into more detail about what a research question must do and look at some examples of research questions.

The research question should be specific and focused

Research questions that are too broad are not suitable to be addressed in a single study. One reason for this can be if there are many factors or variables to consider. In addition, a sample data set that is too large or an experimental timeline that is too long may suggest that the research question is not focused enough.

A specific research question means that the collective data and observations come together to either confirm or deny the chosen hypothesis in a clear manner. If a research question is too vague, then the data might end up creating an alternate research problem or hypothesis that you haven’t addressed in your Introduction section .

The research question should be based on the literature

An effective research question should be answerable and verifiable based on prior research because an effective scientific study must be placed in the context of a wider academic consensus. This means that conspiracy or fringe theories are not good research paper topics.

Instead, a good research question must extend, examine, and verify the context of your research field. It should fit naturally within the literature and be searchable by other research authors.

References to the literature can be in different citation styles and must be properly formatted according to the guidelines set forth by the publishing journal, university, or academic institution. This includes in-text citations as well as the Reference section .

The research question should be realistic in time, scope, and budget

There are two main constraints to the research process: timeframe and budget.

A proper research question will include study or experimental procedures that can be executed within a feasible time frame, typically by a graduate doctoral or master’s student or lab technician. Research that requires future technology, expensive resources, or follow-up procedures is problematic.

A researcher’s budget is also a major constraint to performing timely research. Research at many large universities or institutions is publicly funded and is thus accountable to funding restrictions.

The research question should be in-depth

Research papers, dissertations and theses , and academic journal articles are usually dozens if not hundreds of pages in length.

A good research question or thesis statement must be sufficiently complex to warrant such a length, as it must stand up to the scrutiny of peer review and be reproducible by other scientists and researchers.

Research Question Types

Qualitative and quantitative research are the two major types of research, and it is essential to develop research questions for each type of study.

Quantitative Research Questions

Quantitative research questions are specific. A typical research question involves the population to be studied, dependent and independent variables, and the research design.

In addition, quantitative research questions connect the research question and the research design. In addition, it is not possible to answer these questions definitively with a “yes” or “no” response. For example, scientific fields such as biology, physics, and chemistry often deal with “states,” in which different quantities, amounts, or velocities drastically alter the relevance of the research.

As a consequence, quantitative research questions do not contain qualitative, categorical, or ordinal qualifiers such as “is,” “are,” “does,” or “does not.”

Categories of quantitative research questions

Qualitative research questions.

In quantitative research, research questions have the potential to relate to broad research areas as well as more specific areas of study. Qualitative research questions are less directional, more flexible, and adaptable compared with their quantitative counterparts. Thus, studies based on these questions tend to focus on “discovering,” “explaining,” “elucidating,” and “exploring.”

Categories of qualitative research questions

Quantitative and qualitative research question examples.

Good and Bad Research Question Examples

Below are some good (and not-so-good) examples of research questions that researchers can use to guide them in crafting their own research questions.

Research Question Example 1

The first research question is too vague in both its independent and dependent variables. There is no specific information on what “exposure” means. Does this refer to comments, likes, engagement, or just how much time is spent on the social media platform?

Second, there is no useful information on what exactly “affected” means. Does the subject’s behavior change in some measurable way? Or does this term refer to another factor such as the user’s emotions?

Research Question Example 2

In this research question, the first example is too simple and not sufficiently complex, making it difficult to assess whether the study answered the question. The author could really only answer this question with a simple “yes” or “no.” Further, the presence of data would not help answer this question more deeply, which is a sure sign of a poorly constructed research topic.

The second research question is specific, complex, and empirically verifiable. One can measure program effectiveness based on metrics such as attendance or grades. Further, “bullying” is made into an empirical, quantitative measurement in the form of recorded disciplinary actions.

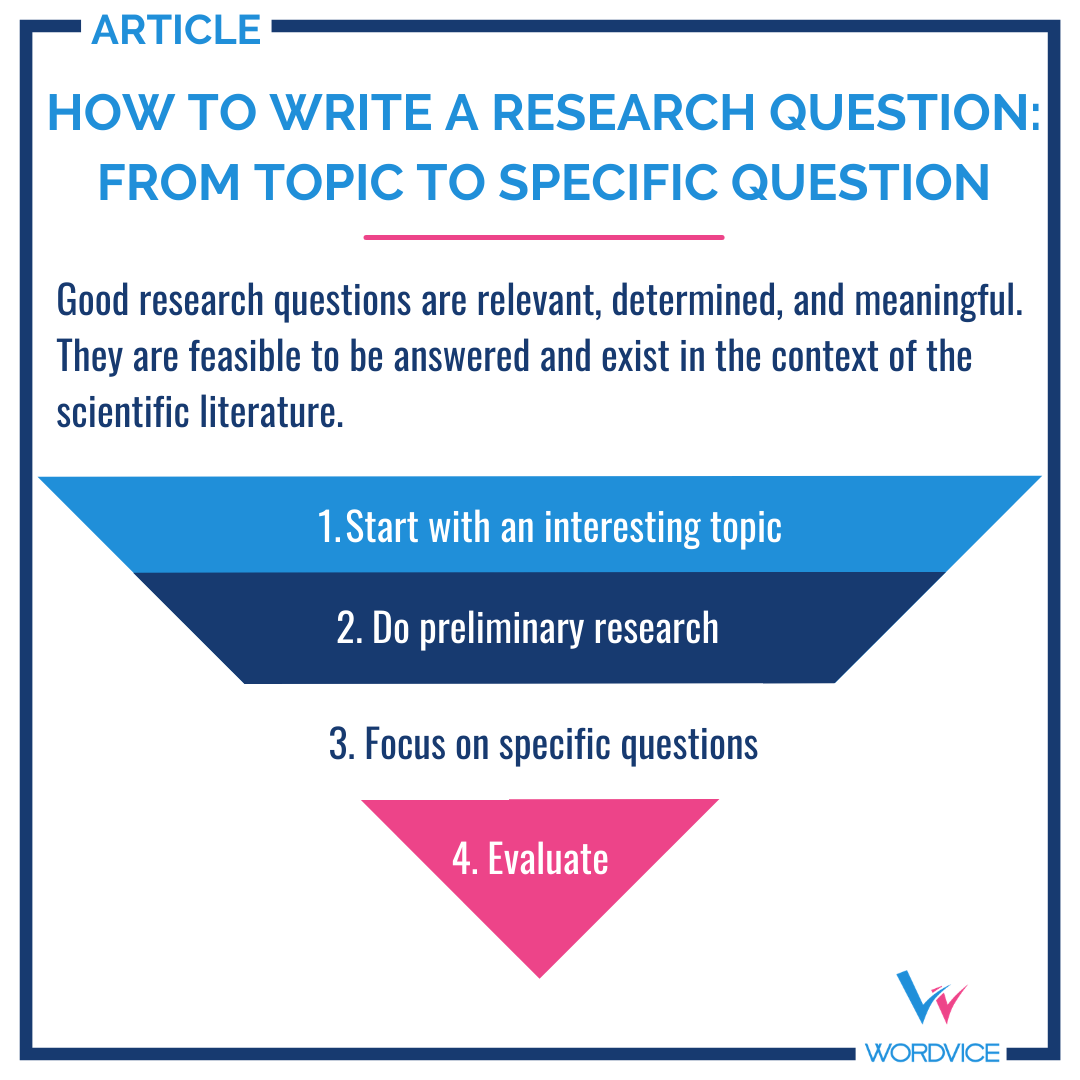

Steps for Writing a Research Question

Good research questions are relevant, focused, and meaningful. It can be difficult to come up with a good research question, but there are a few steps you can follow to make it a bit easier.

1. Start with an interesting and relevant topic

Choose a research topic that is interesting but also relevant and aligned with your own country’s culture or your university’s capabilities. Popular academic topics include healthcare and medical-related research. However, if you are attending an engineering school or humanities program, you should obviously choose a research question that pertains to your specific study and major.

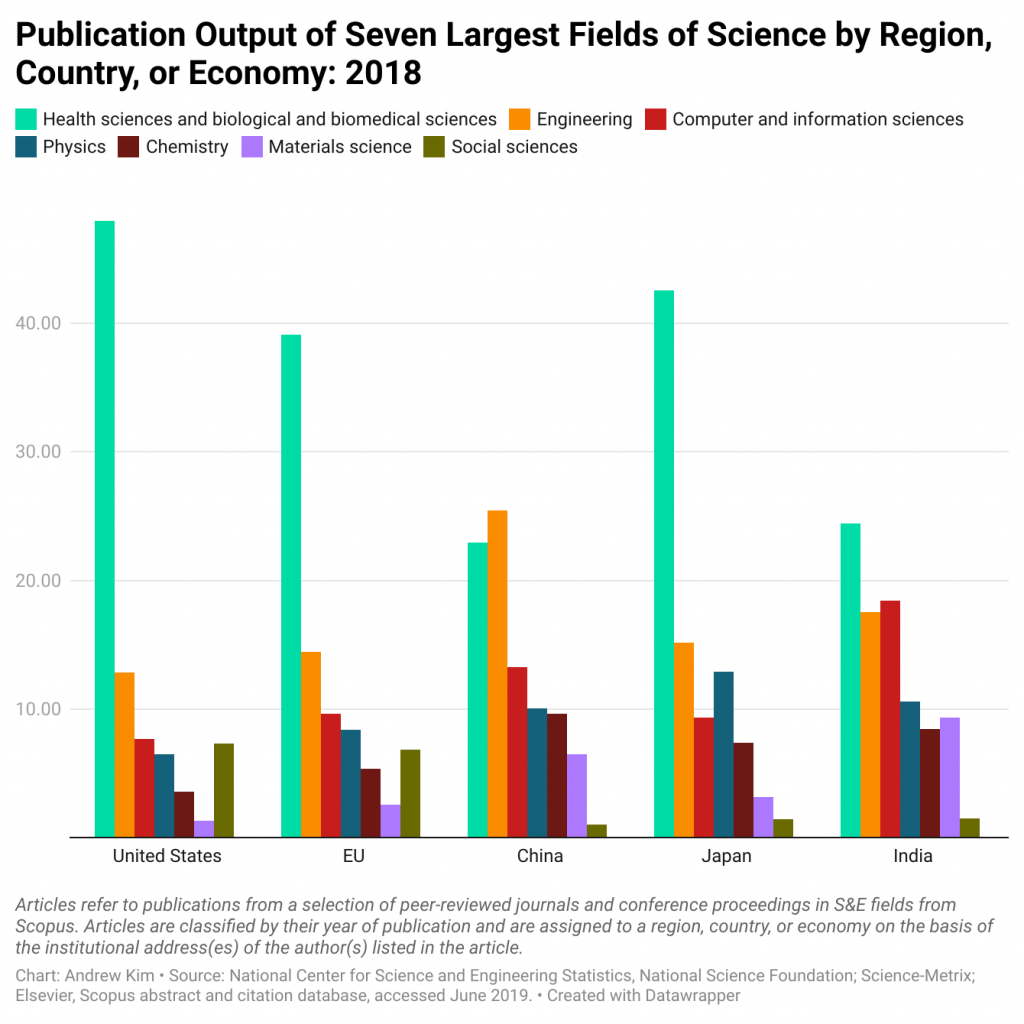

Below is an embedded graph of the most popular research fields of study based on publication output according to region. As you can see, healthcare and the basic sciences receive the most funding and earn the highest number of publications.

2. Do preliminary research

You can begin doing preliminary research once you have chosen a research topic. Two objectives should be accomplished during this first phase of research. First, you should undertake a preliminary review of related literature to discover issues that scholars and peers are currently discussing. With this method, you show that you are informed about the latest developments in the field.

Secondly, identify knowledge gaps or limitations in your topic by conducting a preliminary literature review . It is possible to later use these gaps to focus your research question after a certain amount of fine-tuning.

3. Narrow your research to determine specific research questions

You can focus on a more specific area of study once you have a good handle on the topic you want to explore. Focusing on recent literature or knowledge gaps is one good option.

By identifying study limitations in the literature and overlooked areas of study, an author can carve out a good research question. The same is true for choosing research questions that extend or complement existing literature.

4. Evaluate your research question

Make sure you evaluate the research question by asking the following questions:

Is my research question clear?

The resulting data and observations that your study produces should be clear. For quantitative studies, data must be empirical and measurable. For qualitative, the observations should be clearly delineable across categories.

Is my research question focused and specific?

A strong research question should be specific enough that your methodology or testing procedure produces an objective result, not one left to subjective interpretation. Open-ended research questions or those relating to general topics can create ambiguous connections between the results and the aims of the study.

Is my research question sufficiently complex?

The result of your research should be consequential and substantial (and fall sufficiently within the context of your field) to warrant an academic study. Simply reinforcing or supporting a scientific consensus is superfluous and will likely not be well received by most journal editors.

Editing Your Research Question

Your research question should be fully formulated well before you begin drafting your research paper. However, you can receive English paper editing and proofreading services at any point in the drafting process. Language editors with expertise in your academic field can assist you with the content and language in your Introduction section or other manuscript sections. And if you need further assistance or information regarding paper compositions, in the meantime, check out our academic resources , which provide dozens of articles and videos on a variety of academic writing and publication topics.

How to Develop a Good Research Question? — Types & Examples

Cecilia is living through a tough situation in her research life. Figuring out where to begin, how to start her research study, and how to pose the right question for her research quest, is driving her insane. Well, questions, if not asked correctly, have a tendency to spiral us!

Image Source: https://phdcomics.com/

Questions lead everyone to answers. Research is a quest to find answers. Not the vague questions that Cecilia means to answer, but definitely more focused questions that define your research. Therefore, asking appropriate question becomes an important matter of discussion.

A well begun research process requires a strong research question. It directs the research investigation and provides a clear goal to focus on. Understanding the characteristics of comprising a good research question will generate new ideas and help you discover new methods in research.

In this article, we are aiming to help researchers understand what is a research question and how to write one with examples.

Table of Contents

What Is a Research Question?

A good research question defines your study and helps you seek an answer to your research. Moreover, a clear research question guides the research paper or thesis to define exactly what you want to find out, giving your work its objective. Learning to write a research question is the beginning to any thesis, dissertation , or research paper. Furthermore, the question addresses issues or problems which is answered through analysis and interpretation of data.

Why Is a Research Question Important?

A strong research question guides the design of a study. Moreover, it helps determine the type of research and identify specific objectives. Research questions state the specific issue you are addressing and focus on outcomes of the research for individuals to learn. Therefore, it helps break up the study into easy steps to complete the objectives and answer the initial question.

Types of Research Questions

Research questions can be categorized into different types, depending on the type of research you want to undergo. Furthermore, knowing the type of research will help a researcher determine the best type of research question to use.

1. Qualitative Research Question

Qualitative questions concern broad areas or more specific areas of research. However, unlike quantitative questions, qualitative research questions are adaptable, non-directional and more flexible. Qualitative research question focus on discovering, explaining, elucidating, and exploring.

i. Exploratory Questions

This form of question looks to understand something without influencing the results. The objective of exploratory questions is to learn more about a topic without attributing bias or preconceived notions to it.

Research Question Example: Asking how a chemical is used or perceptions around a certain topic.

ii. Predictive Questions

Predictive research questions are defined as survey questions that automatically predict the best possible response options based on text of the question. Moreover, these questions seek to understand the intent or future outcome surrounding a topic.

Research Question Example: Asking why a consumer behaves in a certain way or chooses a certain option over other.

iii. Interpretive Questions

This type of research question allows the study of people in the natural setting. The questions help understand how a group makes sense of shared experiences with regards to various phenomena. These studies gather feedback on a group’s behavior without affecting the outcome.

Research Question Example: How do you feel about AI assisting publishing process in your research?

2. Quantitative Research Question

Quantitative questions prove or disprove a researcher’s hypothesis through descriptions, comparisons, and relationships. These questions are beneficial when choosing a research topic or when posing follow-up questions that garner more information.

i. Descriptive Questions

It is the most basic type of quantitative research question and it seeks to explain when, where, why, or how something occurred. Moreover, they use data and statistics to describe an event or phenomenon.

Research Question Example: How many generations of genes influence a future generation?

ii. Comparative Questions

Sometimes it’s beneficial to compare one occurrence with another. Therefore, comparative questions are helpful when studying groups with dependent variables.

Example: Do men and women have comparable metabolisms?

iii. Relationship-Based Questions

This type of research question answers influence of one variable on another. Therefore, experimental studies use this type of research questions are majorly.

Example: How is drought condition affect a region’s probability for wildfires.

How to Write a Good Research Question?

1. Select a Topic

The first step towards writing a good research question is to choose a broad topic of research. You could choose a research topic that interests you, because the complete research will progress further from the research question. Therefore, make sure to choose a topic that you are passionate about, to make your research study more enjoyable.

2. Conduct Preliminary Research

After finalizing the topic, read and know about what research studies are conducted in the field so far. Furthermore, this will help you find articles that talk about the topics that are yet to be explored. You could explore the topics that the earlier research has not studied.

3. Consider Your Audience

The most important aspect of writing a good research question is to find out if there is audience interested to know the answer to the question you are proposing. Moreover, determining your audience will assist you in refining your research question, and focus on aspects that relate to defined groups.

4. Generate Potential Questions

The best way to generate potential questions is to ask open ended questions. Questioning broader topics will allow you to narrow down to specific questions. Identifying the gaps in literature could also give you topics to write the research question. Moreover, you could also challenge the existing assumptions or use personal experiences to redefine issues in research.

5. Review Your Questions

Once you have listed few of your questions, evaluate them to find out if they are effective research questions. Moreover while reviewing, go through the finer details of the question and its probable outcome, and find out if the question meets the research question criteria.

6. Construct Your Research Question

There are two frameworks to construct your research question. The first one being PICOT framework , which stands for:

- Population or problem

- Intervention or indicator being studied

- Comparison group

- Outcome of interest

- Time frame of the study.

The second framework is PEO , which stands for:

- Population being studied

- Exposure to preexisting conditions

- Outcome of interest.

Research Question Examples

- How might the discovery of a genetic basis for alcoholism impact triage processes in medical facilities?

- How do ecological systems respond to chronic anthropological disturbance?

- What are demographic consequences of ecological interactions?

- What roles do fungi play in wildfire recovery?

- How do feedbacks reinforce patterns of genetic divergence on the landscape?

- What educational strategies help encourage safe driving in young adults?

- What makes a grocery store easy for shoppers to navigate?

- What genetic factors predict if someone will develop hypothyroidism?

- Does contemporary evolution along the gradients of global change alter ecosystems function?

How did you write your first research question ? What were the steps you followed to create a strong research question? Do write to us or comment below.

Frequently Asked Questions

Research questions guide the focus and direction of a research study. Here are common types of research questions: 1. Qualitative research question: Qualitative questions concern broad areas or more specific areas of research. However, unlike quantitative questions, qualitative research questions are adaptable, non-directional and more flexible. Different types of qualitative research questions are: i. Exploratory questions ii. Predictive questions iii. Interpretive questions 2. Quantitative Research Question: Quantitative questions prove or disprove a researcher’s hypothesis through descriptions, comparisons, and relationships. These questions are beneficial when choosing a research topic or when posing follow-up questions that garner more information. Different types of quantitative research questions are: i. Descriptive questions ii. Comparative questions iii. Relationship-based questions

Qualitative research questions aim to explore the richness and depth of participants' experiences and perspectives. They should guide your research and allow for in-depth exploration of the phenomenon under investigation. After identifying the research topic and the purpose of your research: • Begin with Broad Inquiry: Start with a general research question that captures the main focus of your study. This question should be open-ended and allow for exploration. • Break Down the Main Question: Identify specific aspects or dimensions related to the main research question that you want to investigate. • Formulate Sub-questions: Create sub-questions that delve deeper into each specific aspect or dimension identified in the previous step. • Ensure Open-endedness: Make sure your research questions are open-ended and allow for varied responses and perspectives. Avoid questions that can be answered with a simple "yes" or "no." Encourage participants to share their experiences, opinions, and perceptions in their own words. • Refine and Review: Review your research questions to ensure they align with your research purpose, topic, and objectives. Seek feedback from your research advisor or peers to refine and improve your research questions.

Developing research questions requires careful consideration of the research topic, objectives, and the type of study you intend to conduct. Here are the steps to help you develop effective research questions: 1. Select a Topic 2. Conduct Preliminary Research 3. Consider Your Audience 4. Generate Potential Questions 5. Review Your Questions 6. Construct Your Research Question Based on PICOT or PEO Framework

There are two frameworks to construct your research question. The first one being PICOT framework, which stands for: • Population or problem • Intervention or indicator being studied • Comparison group • Outcome of interest • Time frame of the study The second framework is PEO, which stands for: • Population being studied • Exposure to preexisting conditions • Outcome of interest

A tad helpful

Had trouble coming up with a good research question for my MSc proposal. This is very much helpful.

This is a well elaborated writing on research questions development. I found it very helpful.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Diversity and Inclusion

The Silent Struggle: Confronting gender bias in science funding

In the 1990s, Dr. Katalin Kariko’s pioneering mRNA research seemed destined for obscurity, doomed by…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

Setting Rationale in Research: Cracking the code for excelling at research

Research Problem Statement — Find out how to write an impactful one!

Experimental Research Design — 6 mistakes you should never make!

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research process

- Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

Published on 30 October 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 12 December 2023.

A research question pinpoints exactly what you want to find out in your work. A good research question is essential to guide your research paper , dissertation , or thesis .

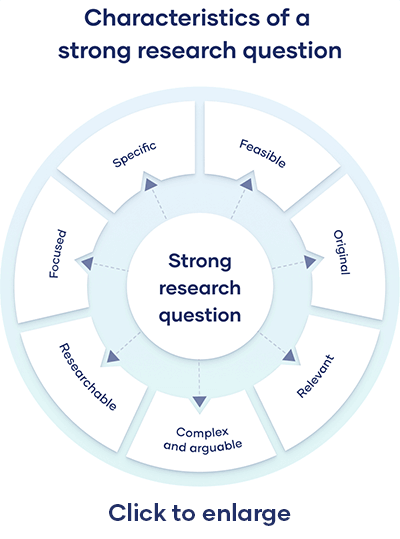

All research questions should be:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis

- Relevant to your field of study and/or society more broadly

Table of contents

How to write a research question, what makes a strong research question, research questions quiz, frequently asked questions.

You can follow these steps to develop a strong research question:

- Choose your topic

- Do some preliminary reading about the current state of the field

- Narrow your focus to a specific niche

- Identify the research problem that you will address

The way you frame your question depends on what your research aims to achieve. The table below shows some examples of how you might formulate questions for different purposes.

Using your research problem to develop your research question

Note that while most research questions can be answered with various types of research , the way you frame your question should help determine your choices.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Research questions anchor your whole project, so it’s important to spend some time refining them. The criteria below can help you evaluate the strength of your research question.

Focused and researchable

Feasible and specific, complex and arguable, relevant and original.

The way you present your research problem in your introduction varies depending on the nature of your research paper . A research paper that presents a sustained argument will usually encapsulate this argument in a thesis statement .

A research paper designed to present the results of empirical research tends to present a research question that it seeks to answer. It may also include a hypothesis – a prediction that will be confirmed or disproved by your research.

As you cannot possibly read every source related to your topic, it’s important to evaluate sources to assess their relevance. Use preliminary evaluation to determine whether a source is worth examining in more depth.

This involves:

- Reading abstracts , prefaces, introductions , and conclusions

- Looking at the table of contents to determine the scope of the work

- Consulting the index for key terms or the names of important scholars

An essay isn’t just a loose collection of facts and ideas. Instead, it should be centered on an overarching argument (summarised in your thesis statement ) that every part of the essay relates to.

The way you structure your essay is crucial to presenting your argument coherently. A well-structured essay helps your reader follow the logic of your ideas and understand your overall point.

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, December 12). Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 6 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/the-research-process/research-question/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, how to write a results section | tips & examples, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

Child Care and Early Education Research Connections

Key questions to ask.

This section outlines key questions to ask in assessing the quality of research and describes internal validity, external validity, and construct validity.

Was the research peer reviewed?

Peer reviewed research studies have already been evaluated by experienced researchers with relevant expertise. Most journal articles, books and government reports have gone through a peer review process. Keep in mind that there are many types of peer reviews. Reports issued by the federal government have been subject to many levels of internal review and approval before being issued. Articles published in professional journals with peer review have been evaluated by researchers that are experts in the field and who can vouch for the soundness of the methodology and the analysis applied. As a result, peer-reviewed research is usually of high quality. A research consumer, however, should still critically evaluate the study's methodology and conclusions.

Can a study's quality be evaluated with the information provided?

Every study should include a description of the population of interest, an explanation of the process used to select and gather data on study subjects, definitions of key variables and concepts, descriptive statistics for main variables, and a description of the analytic techniques. Research consumers should be cautious when drawing conclusions from studies that do not provide sufficient information about these key research components.

Are there any potential threats to the study's validity?

A valid study answers research questions in a scientifically rigorous manner. Threats to a study's validity are found in three areas:

Internal Validity

External validity, construct validity.

Internal Validity refers to whether the outcomes observed in a study are due to the independent variables or experimental manipulations investigated in the study and not to some other factor or set of factors. To determine whether a research study has internal validity, a research consumer should ask whether changes in the outcome could be attributed to alternative explanations that are not explored in the study. For example, a study may show that a new curriculum had a significant positive effect on children's reading comprehension.

The study must rule out alternative explanations for the increase in reading comprehension, such as a new teacher, in order to attribute the increase in reading comprehension to the new curriculum. Studies that specifically explain how alternative explanations were ruled out are more likely to have internal validity. Threats to a study's internal validity can compromise the confidence consumers have in the findings from a study and include:

- The introduction of events while the study is being conducted that may affect the outcome or dependent variable of the study. For example, while studying the effectiveness of children's participation in an early childhood program, the program was closed for an extended period of time due to damage from a hurricane.

- Changes in the dependent variable due to normal developmental processes in study participants. For example, young children's performance on a battery of outcome measures (e.g., reading and math assessments) may decline during the testing or observation period due to fatigue or other factors.

- The circumstances around the testing that is used to assess the dependent variable. For example, preschool children's performance on a standardized test may be questionable if test items are presented to children in unfamiliar ways or in group settings.

- Participants leaving or dropping out of the study before it is completed. This can be especially problematic if those who leave the study are different from those who stay. For example, in a longitudinal study of the effects of a school lunch program on children's academic achievement, the validity of the findings could be problematic if the most disadvantaged children in the program left the study at a higher rate than other children.

- Changes to or inconsistencies in how the dependent and independent variables were measured. For example, changing the way in which children's math skills are measured at two time points could introduce error if the two measures were developed using different assessment frameworks (i.e., they were developed to assess different math content and processes). Inconsistencies are also introduced when different staff follow different procedures when administering the same measure. For example, when administering an assessment to bilingual children, some staff give children credit for answering correctly in English or Spanish, and other staff only give credit for answering correctly in English.

- Statistical regression or regression to the mean can affect the outcome of a study. It is the movement of test scores (post-test scores) toward the mean (average score), independent of any effect of an independent variable. It is especially a concern when assessing the skills of low performing individuals and comparing their skills to those with average or above average performance. For example, kindergarten children with the weakest reading skills at the start of the school year may show the greatest gains in their skills over the school year (e.g., between fall and spring assessments) independent of the instruction they received from their teachers.

External Validity refers to the extent to which the results of a study can be generalized to other settings (ecological validity), other people (population validity) and over time (historical validity). To assess whether a study has external validity, a research consumer should ask whether the findings apply to individuals whose place and circumstances differ from those of study participants. For example, a research study shows that a new curriculum improved reading comprehension of third-grade children in Iowa. As a research consumer, you want to ask whether this new curriculum may also be effective with third graders in New York or with children in other elementary grades. Studies that randomly select participants from the most diverse and representative populations and that are conducted in natural settings are more likely to have external validity. Threats to a study's external validity come from several sources, including:

- The list of all those in the population who are eligible to be sampled is incomplete or contains duplicates. For example, in a household survey, the list of housing units from which the sample will be drawn may be missing housing units (e.g., one or the two housing units in a duplex home). Or, an address list that will be used to drawn a sample may have some households listed twice.

- Some members of the population or members of certain groups may not be adequately represented in the sample (undercoverage). For example, a survey of adult education that relies on a published list of telephone numbers to select its sample may not get an accurate estimate of the participation of adults in different education programs because young adults who have higher rates of participation are less likely to have landlines and to have numbers published.

- Not all individuals who are sampled agree to participate in the study. When those who participate are different in meaningful ways from those who do not, there is the potential for the findings from the study to be biased (nonresponse bias). That is, the findings may not represent an accurate picture of the total population.

- Selecting samples using non-probability methods (e.g., purposive sample, volunteer samples), which tend to over- or under-represent certain groups in the population. For example, volunteer surveys on controversial topics such as school vouchers and sex education are more likely to overrepresent individuals with strong opinions. And, shopping mall surveys in general only represent the small group of individuals who are shopping at a particular location and at specific times.

- The findings from one study are difficult to replicate across locations, groups, and time. Despite the best efforts, it is extremely difficult to introduce and implement a program (treatment) exactly the same way in different locations. Similarly, it is difficult to conduct a study the same way each time. While researchers have control over many features of their studies, there are factors that are beyond their control (e.g., willingness of potential subjects to participate, scheduling conflicts that could lead to cancellations of data collection activities, data collection being suspended due to natural disasters). For example, the ability to carry out a study of school-age children's reading and math achievement in one school or in one school district may be affected by teachers' willingness to surrender instructional time for students to participate in a series of standardized assessments. In some cases, modifications to the study design (e.g., shorten the assessment, limit sensitive questions on a teacher or parent survey) must be made to accommodate the concerns of school and district leaders.

- Changes in the behaviors and reported attitudes of study participants as a result of being included in a research study (Hawthorne effect). For example, parents participating in a research study on children's early development may change the ways in which they support their child's learning at home.

Construct Validity refers to the degree to which a variable, test, questionnaire or instrument measures the theoretical concept that the researcher hopes to measure. To assess whether a study has construct validity, a research consumer should ask whether the study has adequately measured the key concepts in the study. For example, a study of reading comprehension should present convincing evidence that reading tests do indeed measure reading comprehension. Studies that use measures that have been independently validated in prior studies are more likely to have construct validity.

There are many threats to construct validity. These can arise during: the planning and design stage, assessment or survey administration, and data processing and analysis. Some are attributed to researchers and others to the subjects of the research. Here are some of the more common threats:

- Poorly defined constructs are perhaps the largest threat to construct validity. This applies to constructs that are too narrowly defined as well as those that are defined too broadly.

- Validity can also be affected by the measures a researcher chooses to measure a construct. Measures that include too few items to adequately represent the construct pose a threat as do measures that include items that tap other constructs. For example, a math assessment administered to four- and five-year old children that only includes items that require children to count would not be adequate to represent their math skills. A math assessment administered to this same group of children that was made up mostly of word problems would be tapping both their math and language skills. A valid measure should cover all aspects of the theoretical construct and only aspects of the theoretical construct.

- Assessment items or survey questions that are poorly written are threats to validity. Such items would include double-barreled questions that ask multiple questions within a single item (e.g., are you happily married and do you and your spouse argue?). Other examples of poorly written questions include those that use language that is above the reading level of most respondents, use professional jargon or are written in such a way as to trigger a socially desirable response.

- The validity of an assessment is threatened if there are too many items that are outside the ability of the individual being assessed (e.g., too many very easy items and too many very difficult items). For example, an early literacy assessment that only included passages that children were asked to read and answer questions about would not result in a valid assessment of children's early literacy.

- Threats that are introduced by interviewers and assessment staff. Actions by these individuals that can affect the reliability and thus the validity of the assessment occur when they deviate from the research protocol and when they signal a correct answer to the study participant through their actions. For example, an assessment of young children's English language vocabulary may specify that only responses in English are acceptable. However, when assessing bilingual children, some assessors comply with this rule while others accept responses in English or in the child's home language (e.g., Spanish). Assessors may unintentionally signal to children the correct responses on an assessment by 'staring' at the correct response to a multiple-choice item or by smiling and giving praise only when the child answers correctly.

- Threats to validity can also be introduced by the research participants. These would include participant apprehension or anxiety that could result in poorer performance on an assessment or to incorrect or ambiguous responses to a series of interview items. These threats must be taken seriously and addressed when administering standardized assessments to young children, many of whom will have limited experience with these types of tests. The language used when administering an assessment can also threaten its validity, if subjects do not have the language skills to understand what they are being asked to do and the language skills needed to respond.

- Coding errors - Coding errors that are systematic as compared to those that are random are especially problematic.

- Poor inter-coder or inter-rater reliability - When coding responses to open-ended survey items or assigning scores to behaviors observed during a video interaction, it is important that different coders or raters assign the same code or score for the same response or behavior. That is, the goal is high inter-coder or inter-rater reliability. When inter-coder or inter-rater reliability is poor, it can have an adverse effect on the validity of a measure. For example, the construct validity of an observation measure of the quality of parent-child interactions could be compromised should individual members of a group coding a set of videotaped mother-child interactions apply different standards as to what they deem as intrusive parenting practices.

- Inconsistencies in how data are analyzed and missing data handled - Missing data may be handled in a number of different ways, and the approach that is chosen could prove to be problematic for a construct, especially when the data are not missing at random. For example, if items tapping certain math skills are missing disproportionately, the validity of the measure could be jeopardized if a researcher assigns the mean score for those items or if he simply averages the scores for the non-missing items.

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

- Artificial Intelligence

Market Research

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

- Market Research Questions

Try Qualtrics for free

Market research questions: what to ask and how.

9 min read Whether you’re looking for customer feedback, product suggestions or brand perception in the market, the right market research questions can help you get the best insights. Learn how you can use them correctly and where to begin.

What is market research?

Market research (also called marketing research) is the action or activity of gathering information about market needs and preferences. This helps companies understand their target market — how the audience feels and behaves.

For example, this could be an online questionnaire , shared by email, which has a set of questions that ask an audience about their views. For an audience of target customers, your questions may explore their reaction to a new product that can be used as feedback into the design.

Why do market research?

When you have tangible insights on the audience’s needs, you can then take steps to meet those needs and solve problems. This mitigates the risk of an experience gap – which is what your audience expects you deliver versus what you actually deliver.

In doing this work, you can gain:

- Improved purchase levels – Sales will improve if your product or service is ticking all the right buttons for your customers.

- Improved decision making – You can avoid the risk of losing capital or time by using what your research tells you and acting with insights.

- Real connection with your target market – If you’re investing in understanding your target audience, your product and service will more likely to make an impact.

- Understand new opportunities – it might be that your research indicates a new area for your product to play within, or you find potential for a new service that wasn’t considered before.

Get started with our free survey maker

Who do you ask your questions to?

Who to target in your market research is crucial to getting the right insights and data back. If you don’t have a firm idea on who your target audiences are, then here are some questions that you can ask before you begin writing your market research questions:

- Who is our customer currently and who do we want to attract in the future?

- How do they behave with your brand?

- What do they say, do and think?

- What are their pain points, needs and wants?

- Where do they live? What is the size of our market?

- Why do they use us? Why do they use other brands?

We’ve put together some questions below (Market research questions for your demographics) if you wanted to reach out to your market for this.

With the answers, you can help you segment your customer market, understand key consumer trends , create customer personas and discover the right way to target them.

Market research goals

Give yourself the right direction to work towards.There are different kinds of market research that can happen, but to choose the right market research questions, figure out your market research goals first.

Set a SMART goal that thinks about what you want to achieve and keeps you on track. SMART stands for Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Timely. For example, a good SMART business goal would be to increase website sales for a top product by 10% over a period of 6 months.

You may need to review some strategic business information, like customer personas and historical sales data, which can give you the foundation of knowledge (the ‘baseline’) to grow from. This, combined with your business objectives, will help you form the right SMART targets tailored to your teams.

Types of market research questions

Now that you have your SMART target, you can look at which type of market research questions will help you reach your goal. They can be split into these types:

- For demographics

- For customers

- For product

Market research questions for your demographics

Demographic information about your customers is data about gender, age, ethnicity, annual income, education and marital status. It also gives key information about their shopping habits.

Here are some questions you can ask in your market research survey:

- What is your age / gender / ethnicity / marital status?

- What is the highest level of education you have achieved?

- What is your monthly income range?

- What methods of shopping do you use?

- What amount do you spend on [product/brand/shopping] each month?

- How regular do you shop for [product/brand]?

Learn more about the demographic survey questions that yield valuable insights .

Market research questions for your customer

These questions are aimed at your customer to understand the voice of the customer — the customer marketing landscape is not an one-way dialogue for engaging prospects and your customer’s feedback is needed for the development of your products or services.

- How did we do / would you rate us?

- Why did you decide to use [product or service]?

- How does that fit your needs?

- Would you recommend us to your friends?

- Would you buy from us again?

- What could we do better?

- Why did you decide to shop elsewhere?

- In your opinion, why should customers choose us?

- How would you rate our customer experience?

Learn more about why the voice of the customer matters or try running a customer experience survey.

Market research questions for your product

These questions will help you understand how your customers perceive your product, their reactions to it and whether changes need to be made in the development cycle.

- What does our [product or service] do that you like or dislike?

- What do you think about [feature or benefit]?

- How does the product help you solve your problems?

- Which of these features will be the most valuable / useful for you?

- Is our product competitive with other similar products out there? How?

- How does the product score on [cost / service / ease of use, etc.]?

- What changes will customers likely want in the future that technology can provide?

There are also a set of questions you can ask to find out if your product pricing is set at the right mark:

- Does the product value justify the price it’s marketed at?

- Is the pricing set at the right mark?

- How much would you pay for this product?

- Is this similar to what competitors are charging?

- Do you believe the price is fair?

- Do you believe the pricing is right based on the amount of usage you’d get?

Have you tried a pricing and value research survey to see how much your target customers would be willing to pay?

Market research questions for your brand

How does the impact of your products, services and experiences impact your brand’s image? You can find out using these questions:

- What do you think about our brand?

- Have you seen any reviews about us online? What do they say?

- Have you heard about our brand from friends or family? What do they say?

- How likely are you to recommend our brand to a friend?

- Have you read the testimonials on our own channels? Did they have an impact on your decision to purchase? How?

- When you think of our brand, what do you think/ feel / want?

- How did you hear about us?

- Do you feel confident you know what our brand stands for?

- Are you aware of our [channel] account?

Learn more about brand perception surveys and how to carry them out successfully.

How to use market research questions in a survey

For the best research questionnaires, tailoring your market research questions to the goal you want will help you focus the direction of the data received.

You can get started now on your own market research questionnaire, using one of our free survey templates, when you sign up to a free Qualtrics account.

Drag-and-drop interface that requires no coding is easy-to-use, and supported by our award-winning support team.

With Qualtrics, you can distribute, and analyse surveys to find customer, employee, brand, product, and marketing research insights.

More than 11,000 brands and 99 of the top 100 business schools use Qualtrics solutions because of the freedom and power it gives them.

Get started with our free survey maker tool

Related resources

Market intelligence 10 min read, marketing insights 11 min read, ethnographic research 11 min read, qualitative vs quantitative research 13 min read, qualitative research questions 11 min read, qualitative research design 12 min read, primary vs secondary research 14 min read, request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

Eight questions to ask when interpreting academic studies: A primer for media

Scholarly research is a great source for rigorous, unbiased information, but making judgments about its quality can be difficult. Here are some important questions to ask when reading studies.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Justin Feldman and John Wihbey, The Journalist's Resource March 26, 2015

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/home/interpreting-academic-studies-primer-media/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

Reading scholarly studies can help journalists integrate rigorous, unbiased sources of information into their reporting. These studies are typically carried out by professors and professional researchers — at universities, think tanks and government institutions — and are published through a peer-review process in which those familiar with the study area ensure that there are no major flaws.

Even for people who carry out research, however, interpreting scientific (and social science) studies and making judgments about their quality can be difficult tasks. In a now-famous article, Stanford professor John Ioannidis argues that “ most published research findings are false ” due to inherent limitations in how researchers design studies. (Health and medical studies can be particularly attractive to media, but be aware that there is a long history of faulty findings .) Occasionally, too, studies can be the product of outright fraud: A 1998 study falsely linking vaccines and autism is now perhaps the canonical example, as it spurred widespread and long-lasting societal damage . Journalists should also always examine the funding sources behind the study, which are frequently declared at the study’s conclusion.

Before journalists write about research and speak with authors, they should be able to both interpret a study’s results generally and understand the appropriate degree of skepticism that a given study’s findings warrant. This requires data literacy , some familiarity with statistical terms and a basic knowledge of hypothesis testing and construction of theories .

Journalists should also be well aware that most academic research contains careful qualifications about findings. The common complaint from scientists and social scientists is that news media tend to pump up findings and hype studies through catchy headlines, distorting public understanding. But landmark studies sometimes do no more than tighten the margin of error around a given measurement — not inherently flashy, but intriguing to an audience if explained with rich context and clear presentation.

Here are some important questions to ask when reading a scientific study:

1. What are the researchers’ hypotheses?

A hypothesis is a research question that a study seeks to answer. Sometimes researchers state their hypotheses explicitly, but more often their research questions are implicit. Hypotheses are testable assertions usually involving the relationship between two variables. In a study of smoking and lung cancer, the hypothesis might be that smokers develop lung cancer at a higher rate than non-smokers over a five-year period.

It is also important to note that there are formal definitions of null and alternative hypotheses for use with statistical analysis.

2. What are the independent and dependent variables?

Independent variables are factors that influence particular outcomes. Dependent variables are measures of the outcomes themselves. In the study assessing the relationship between smoking and lung cancer, smoking is the independent variable because the researcher assumes it predicts lung cancer, the dependent variable. (Some fields use related terms such as “exposure” and “outcome.”)

Pay particular attention to how the researchers define all of the variables — there can be quite a bit of nuance in the definitions. Also look at the methods by which the researchers measure the variables. Generally speaking, a variable measured using a subject’s response to a survey question is less trustworthy than one measured through more objective means — reviewing laboratory findings in their medical records, for example.

3. What is the unit of analysis?

For most studies involving human subjects, the individual person is the unit of analysis. However, studies are sometimes interested in a different level of analysis that makes comparisons between classrooms, hospitals, schools or states, for example, rather than between individuals.

4. How well does the study design address causation?

Most studies identify correlations or associations between variables, but typically the ultimate goal is to determine causation . Certain study designs are more useful than others for the purpose of determining causation.

At the most basic level, studies can be placed into one of two categories: experimental and observational . In experimental studies, the researchers decide who is exposed to the independent variable and who is not. In observational studies, the researchers do not have any control over who is exposed to the independent variable — instead they make comparisons between groups that are already different from one another. In nearly all cases, experimental studies provide stronger evidence than observational studies.

Here are descriptions of some of the most common study designs, presented along with their respective values for inferring causation:

- Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), also known as clinical trials, are experimental studies that are considered the “gold standard” in research. Out of all study designs, they have the most value for determining causation although they do have limitations. In an RCT, researchers randomly divide subjects into at least two groups: One that receives a treatment, and the other — the control group — that receives either no treatment or a simulated version of the treatment called a placebo . The independent variable in these experiments is whether or not the subject receives the real treatment. Ideally an RCT should be double-blind — the participants should not know to which treatment group they have been assigned, nor should the study staff know. This arrangement helps to avoid bias. Researchers commonly use RCTs to meet regulatory requirements, such as evaluating pharmaceuticals for the Food and Drug Administration. Due to issues of cost, logistics and ethics, RCTs are fairly uncommon for other purposes. Example: “ Short-Term Soy Isoflavone Intervention in Patients with Localized Prostate Cancer ”

- Longitudinal studies , like RCTs, follow the same subjects over a given time period. Unlike in RCTs, they are observational. Researchers do not assign the independent variable in longitudinal studies — they instead observe what happens in the real world. A longitudinal study might compare the risk for heart disease among one group of people who are exposed to high levels of air pollution to the risk of heart disease among another group exposed to low levels of air pollution. The problem is that, because there is no random assignment, the groups may differ from one another in other important ways and, as a result, we cannot completely isolate the effects of air pollution. These differences result in confounding and other forms of bias. For that reason, longitudinal studies have less validity for inferring causation than RCTs and other experimental study designs. Longitudinal studies have more validity than other kinds of observational studies, however. Example: “ Mood after Moderate and Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Prospective Cohort Study ”

- Case-control studies are technically a type of longitudinal study, but they are unique enough to discuss separately. Common in public health and medical research, case-control studies begin with a group of people who have already developed a particular disease and compare them to a similar but disease-free group recruited by the researchers. These studies are more likely to suffer from bias than other longitudinal studies for two reasons. First, they are always retrospective , meaning they collect data about independent variables years after the exposures of interest occurred — sometimes even after the subject has died. Second, the group of disease-free people is very likely to differ from the group that developed the disease, creating a substantial risk for confounding. Example: “ Risk Factors for Preeclampsia in Women from Colombia ”.

- Cross-sectional studies are a kind of observational study that measure both dependent and independent variables at a single point in time. Although researchers may administer the same cross-sectional survey every few years, they do not follow the same subjects over time. An important part of determining causation is establishing that the independent variable occurred for a given subject before the dependent variable occurred. But because they do not measure the variables over time, cross-sectional studies cannot determine that a hypothesized cause precedes its effect, so the design is limited to making inferences about correlations rather than causation. Example : “ Physical Predictors of Cognitive Performance in Healthy Older Adults ”

- Ecological studies are observational studies that are similar to cross-sectional studies except that they measure at least one variable on the group-level rather that the subject-level. For example, an ecological study may look at the relationship between individuals’ meat consumption and their incidence of colon cancer. But rather than using individual-level data, the study relies on national cancer rates and national averages for meat consumption. While it might seem that higher meat consumption is linked to a higher risk of cancer, there is no way to know if the individuals eating more meat within a country are the same people who are more likely to develop cancer. This means that ecological studies are not only inadequate for inferring causation, they are also inadequate for establishing a correlation. As a consequence, they should be regarded with strong skepticism. Example: “ A Multi-country Ecological Study of Cancer Incidence Rates in 2008 with Respect to Various Risk-Modifying Factors ”

- Systematic reviews are surveys of existing studies on a given topic. Investigators specify inclusion and exclusion criteria to weed out studies that are either irrelevant to their research question or poorly designed. Using keywords, they systematically search research databases, present the findings of the studies they include and draw conclusions based on their consideration of the findings. Assuming that the review includes only well-designed studies, systematic reviews are more useful for inferring causation than any single well-designed study. Example: “ Enablers and Barriers to Large-Scale Uptake of Improved Solid Fuel Stoves. ” For a sense of how systematic reviews are interpreted and used by researchers in the field, see “How to Read a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis and Apply the Results to Patient Care,” published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA.)

- Meta-analyses are similar to systematic reviews but use the original data from all included studies to create a new analysis. As a result, a meta-analysis is able to draw conclusions that are more meaningful than a systematic review. Again, a meta-analysis is more useful for inferring causation than any single study, assuming that all studies are well-designed. Example: “ Occupational Exposure to Asbestos and Ovarian Cancer ”

5. What are the study’s results?

There are several aspects involved in understanding a study’s results: