- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, improving undergraduates’ and postgraduates’ academic writing skills with strategy training and feedback.

- Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany

To improve text quality in higher education, training writing strategies (i.e., text structure application, summarization, or language use) and provision of feedback for revising (i.e., informative tutoring feedback or try-again feedback) were tested in combination. The aim was to establish whether first, strategy training affects academic writing skills that promote coherence, second, whether undergraduates and postgraduates benefit differently from feedback for revising, and third, whether training text structure application strategy in combination with informative tutoring feedback was most effective for undergraduates’ text quality. Undergraduate and postgraduate students ( N = 212) participated in the 2-h experimental intervention study in a computer-based learning environment. Participants were divided into three groups and supported by a writing strategy training intervention (i.e., text structure knowledge application, summarization, or language use), which was modeled by a peer student in a learning journal. Afterward participants wrote an abstract of an empirical article. Half of each group received in a computer-based learning environment twice either try-again feedback or informative tutoring feedback while revising their drafts. Writing skills and text quality were assessed by items and ratings. Analyses of covariance revealed that, first, text structure knowledge application strategy affected academic writing skills positively; second, feedback related to writing experience resulted in higher text quality: undergraduates benefited from informative tutoring feedback, postgraduates from try-again feedback; and third, the combination of writing strategy and feedback was not significantly related to improved text quality.

Introduction

The writing performance of freshmen and even graduate students reveals a gap between writing skills learned at school and writing skills required at the college or university level ( Kellogg and Whiteford, 2009 ): writers at school are able to transform their knowledge into a text that they can understand and use for their own benefit. Academic writing requires in addition to that presuming the readers’ understanding of the text written so far to establish a highly coherent text ( Kellogg, 2008 ).

Several studies have shown that to improve writing, it is beneficial to train writing strategies and to support the writing process through feedback ( Graham, 2006 ; Nelson and Schunn, 2009 ; Donker et al., 2014 ). This is also true for higher education ( Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick, 2006 ; MacArthur et al., 2015 ; Wischgoll, 2016 ). Writing strategies can help learners to control and modify their efforts to master the writing task ( Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987 ). Feedback for improving writing provides information about the adequacy of the writing product ( Graham and Perin, 2007 ). On the other hand, feedback that interrupts the writing process might be inhibitive ( Corno and Snow, 1986 ). Feedback that is administered adaptively to the current level of needs, can aim to increase the learner’s efforts to reduce the discrepancy between actual and desired performance ( Hattie and Timperley, 2007 ; Shute, 2008 ).

In terms of writing strategies, research pointed out that writers who use summarization strategies can retrieve information to generate new texts and that writers who use text structure strategies can find and assign information ( Englert, 2009 ; Kellogg and Whiteford, 2009 ). In terms of feedback, research pointed out that feedback should be aligned to writing experience ( Shute, 2008 ). Despite the large body of research on writing strategies ( Graham and Perin, 2007 ; Graham et al., 2013 ) and on feedback ( Hattie and Timperley, 2007 ; Nelson and Schunn, 2009 ), little is known about the specific combination of training to apply text structure knowledge or summarization and feedback with different degree of elaboration in higher education. However, we do know that training to apply text structure knowledge as cognitive writing strategy in combination with training to self-monitor the writing process as metacognitive writing strategy can be beneficial for undergraduates’ writing skills and text quality ( Wischgoll, 2016 ). Furthermore, we know that feedback received from outside the self can induce metacognitive activities ( Butler and Winne, 1995 ). Thus, feedback to monitor the writing process is expected to be another means to foster text quality in combination with training a cognitive writing strategy.

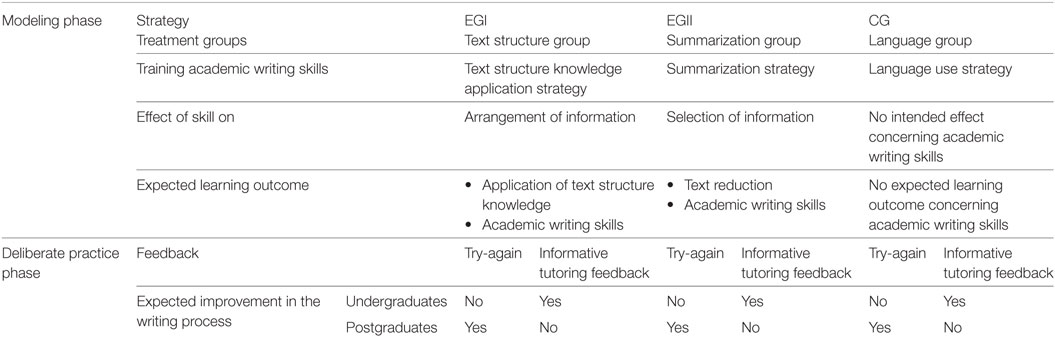

The present study investigated the effects of cognitive writing strategies on academic writing skills and of feedback to foster monitoring the writing process on undergraduates’ and postgraduates’ text quality. The application of academic writing strategies such as summarization strategy and text structure knowledge application strategy help the writer to connect information units to generate a text that is easy to follow. Feedback related to practice aims to support the writer in monitoring the writing process while he or she is applying writing strategies. Accordingly, feedback provided in this study is deemed to be metacognitive in nature. (For an overview please see Table 1 .)

Table 1 . Treatments with expected learning outcome.

Observing and Practicing As Means to Acquire Writing Skills

To train writing skills, Kellogg (2008) recommends both learning by observing and learning by doing. He claims that these two training methods complement each other if they are administered in appropriate proportions.

Learning to write by observing is an often practiced method ( Rosenthal and Zimmerman, 1978 ; Bandura, 1986 , 1997 ; Schunk, 1987 , 1991 ), which can be administered by observing a mastery model or a coping model. Zimmerman and Kitsantas (2002) showed that college students improved strongly by observing a coping model who was struggling to deal with challenges. Furthermore, Braaksma et al. (2004) demonstrated that learners improved through cognitive and metacognitive activities such as observing, evaluating, and reflecting on activities while they were observing the model.

Learning to write by doing follows on from observational learning. To develop writing skills, Kellogg (2008) recommends a combination of observational learning and practice with gradually fading support, such as the model of cognitive apprenticeship ( Collins et al., 1989 ), the sociocognitive model ( Schunk and Zimmerman, 1997 ) and especially for writing development, the Self-Regulated Strategy Development framework ( Graham, 2006 ).

Establishing Coherence Promotes Text Quality

Coherence and cohesion are criteria to estimate text quality ( Witte and Faigley, 1981 ). Coherence refers to the mental representations about the situation presented in the text that readers can form depending on their skills and knowledge and related to surface indicators in the text. It is generated by psychological representations and processes ( Witte and Faigley, 1981 ; Graesser et al., 2004 ). Cohesion as it refers to surface indicators of relations between sentences is a text characteristic ( McNamara et al., 1996 ). Lexical and grammatical relationship supports the reader to find and interpret main ideas and to connect these ideas to higher information units ( Witte and Faigley, 1981 ; Graesser et al., 2004 ). Readers can understand a coherent text that lacks cohesion, as they construct a mental representation for the situation ( Witte and Faigley, 1981 ; Graesser et al., 1994 , 2004 ).

In terms of promoting text quality, writing a text requires the establishment of coherence by relating different information units ( Sanders et al., 1992 ; McNamara et al., 1996 ). Characteristically, the interpretation of the related segments provides more information than is provided by the sum of the information units taken in isolation ( Sanders et al., 1992 ; Sanders and Sanders, 2006 ). Once the information units are related to a coherent text, readers can understand the text’s message ( Van Dijk and Kintsch, 1983 ). The more coherently a text is written, the more easily readers can understand it ( McNamara et al., 1996 ). Therefrom the focus for analyzing text quality in this study is reasoned in coherence.

To establish coherence, Spivey (1990) postulates that academic writing involves strategies of organizing, selecting, and connecting. Training a text structure knowledge application strategy or a summarization strategy seems to be a promising means to achieve this: summarization includes intensively reading, selecting main ideas, and composing sentences to generate a coherent text ( Kellogg and Whiteford, 2009 ). Text structure knowledge fosters systematically reading to find propositions, which facilitate composing a coherent text ( Englert, 2009 ). Furthermore, receiving feedback while revising can facilitate the writing process if it is aligned to writing experience ( Shute, 2008 ) and can, thus, promote text quality in terms of coherence.

Interplay of Cognitive and Metacognitive Support to Become an Academic Writer

Especially in higher education, the interplay of cognitive and metacognitive support is important for mastering complex tasks such as academic writing ( Veenman and Beishuizen, 2004 ; Veenman et al., 2004 ). Research has shown that the combination of cognitive and metacognitive support is a promising means to foster learners’ writing development ( MacArthur et al., 2015 ; Wischgoll, 2016 ). Cognitive support can be administered by modeling writing strategies, enabling the learner to observe when and how a certain activity can be accomplished. Metacognitive support can be administered by giving feedback in the writing process, deliberately accompanying learners while they are monitoring their writing process.

Facilitating the Writing Process through Cognitive Writing Strategy Training

Improving text quality in academic writing can be supported by training a text structure knowledge application strategy or a summarization strategy. The former supports the writer in relating main propositions via a genre-based structure that provides some kind of schema to fill in. The latter supports the writer in relating main propositions by selecting and organizing information units.

Text structure knowledge is closely related to reading comprehension and writing performance ( Hiebert et al., 1983 ). On the one hand, the structure of a text helps readers to easily find what they are looking for; on the other hand, the text structure helps writers to coordinate ideas and intention. Englert (2009) confirmed the importance of text structure knowledge training for writers to organize the writing process. Practice supports writers in using the text structure to find information and in assigning their ideas to the corresponding text sections ( Englert and Thomas, 1987 ). The type of text structure also influences reading and writing performance ( Englert and Hiebert, 1984 ). The empirical research article is a frequently used genre in academic writing, which enables the research community to receive research-relevant information in a concise but elaborated style ( Kintsch and Van Dijk, 1978 ; Swales, 1990 ). As the structure is expected and shared in the scientific community, it helps the main propositions of the empirical research article to be developed and arranged. Hence, the text structure supports the reader in following and understanding a text.

In empirical research articles, information from other texts is typically reproduced, and the selection of this information requires summarization skills. Expert writers select such information from different text sources and use it to invent a new text with derived, new information units ( Spivey, 1990 ). For this purpose, expert writers delete redundant information, generalize connected propositions, and construct topic sentences organize information ( Van Dijk and Kintsch, 1983 ). In a study on paraphrasing expository texts, junior college students were able to delete redundant information but displayed significant deficits in generalization and construction ( Brown and Day, 1983 ). On the other hand, Hidi and Anderson (1986) found that experienced writers when writing summaries selected information in a constructive way, by emphasizing an intended message of the text. Summarizing and developing a main thread makes it easier for readers to follow and to understand their writing ( Graesser et al., 1994 ; Li, 2014 ).

As expert writers are able to use stored writing strategies which novice writers are yet to learn, expert and novice writers revise their texts differently ( Sommers, 1980 ; Hayes, 2004 ; Chanquoy, 2008 ): expert writers detect more problems of a text that are related to content and structure and are able to pay heed to the target audience while revising their text ( Hayes et al., 1987 ). Novice writers detect mainly surface errors and focus primarily on the word and sentence level ( Sommers, 1980 ; Fitzgerald, 1992 ; Cho and MacArthur, 2010 ).

In sum, facilitating writing through training strategies to apply summarization or text structure knowledge should be conducive for less experienced academic writers whereas more experienced writers might already rely on stored writing strategies.

Facilitating the Monitoring of the Writing Process through Feedback

To help writers to improve their texts and to develop their writing skills, besides training writing strategies support can also be provided as feedback aligned to the current level of experience ( Kellogg, 2008 ). Shute (2008) reports several types of feedback that differ in the degree of elaboration, for instance try-again feedback with no elaboration, and informative tutoring feedback with intensive elaboration. Try-again feedback points out that there is a gap between current and desired level of performance and offers him or her a further opportunity to work on the task ( Clariana, 1990 ). Informative tutoring feedback is seen as the most elaborated form of feedback. It encompasses evaluation about the work done so far, points out errors, and offers strategic hints on how to proceed. In this process, the correct answer is usually not provided ( Narciss and Huth, 2004 ).

The type of feedback influences learners differently depending on their writing experience. Hanna (1976) showed that low-ability learners benefited more from elaborated feedback than from feedback that provides information about the correctness of the work produced so far. Similarly, Clariana (1990) found that elaborated feedback produced the highest scores for low-ability students, and try-again feedback the lowest. For high-ability learners, Hanna (1976) found the most benefit from feedback without elaboration, such as verification of the work produced so far. Furthermore, his findings indicate that high-ability learners benefit from working at their own pace; and consequently, feedback should not interrupt the work progress. Hence, feedback for high-ability learners should not be elaborated when it is given during the work process ( Clariana, 1990 ).

The results of the aforementioned studies indicate that high-ability and low-ability as well as novice and experienced learners should be treated in different ways. Whereas low-ability and novice learners benefit from support and explicit guidance during the learning process ( Moreno, 2004 ), high-ability and experienced learners need freedom to work at their own pace ( Hanna, 1976 ). Depending on the level of prior knowledge and experience support might be conducive and not. Hence, support should be demanding but not overdemanding for the learner, and provide guidance that meets the learner’s needs ( Koedinger and Aleven, 2007 ). Support that is effective with unexperienced learners but ineffective with experienced learners is called expertise reversal effect ( Kalyuga et al., 2003 ).

In sum, facilitating writing through feedback should be optimally aligned to writing experience: more experienced writers may need modest feedback while writing, whereas less experienced writers may benefit from feedback that offers some kind of guidance.

Combination of Training a Cognitive Writing Strategy and Receiving Feedback

Several meta-analyses reported about the effectiveness of certain writing activities, such as summarization and monitoring, to improve the acquisition of writing skills and text quality ( Graham and Perin, 2007 ; Kellogg and Whiteford, 2009 ); however, we know little about how the recommended writing activities can be combined effectively for writing development in higher education. In a recent study, Wischgoll (2016) tested the combination of training two writing strategies to improve undergraduates’ text quality. She combined the training of one cognitive writing strategy, i.e., text structure application strategy, with training of another cognitive writing strategy, i.e., summarization strategy, respectively, with training a metacognitive strategy, i.e., self-monitoring strategy. Results revealed that undergraduates benefited from training one cognitive writing strategy and one metacognitive writing strategy in terms of text quality more than those who received training with two cognitive writing strategies. This result indicates that combined training of one cognitive and one metacognitive writing strategy can be effective.

The study described here follows the idea that combining support that induces cognitive writing activities and support that induces metacognitive writing activities results in improved text quality. From the studies mentioned in the sections before, we derive that, first, training writing strategies to apply summarization or text structure knowledge can induce cognitive writing activities; second, providing feedback that supports monitoring the writing process to establish coherence can induce metacognitive writing activities.

The Present Study

The first aim of this study was, first, to analyze whether the training of writing strategies affects academic writing skills; more specifically we analyzed first, whether text structure knowledge application strategy training affects the skill to use genre specific structures to find and assign information, and second, whether summarization strategy training affects the skill to reduce text content while maintaining coherence.

Second, it was assumed that undergraduates benefit from receiving informative tutoring feedback after training to apply text structure knowledge more than from receiving informative tutoring feedback after training summarization or language use; more specifically, that feedback during text revision affects undergraduates’ and postgraduates’ text quality differently. We assumed that undergraduates benefit from informative tutoring feedback because it provides guidance while writing, and that postgraduates benefit from try-again feedback because it does not interrupt the application of already acquired writing skills.

Third, it was assumed that undergraduates benefit more from training to apply text structure knowledge and receiving informative tutoring feedback concerning text quality than undergraduates who trained summarization strategy or language use strategy and received informative tutoring feedback.

We also assessed self-efficacy and motivation to discern whether the intervention was accepted by the participants and whether all treatment groups were equally motivated.

The following hypotheses were tested:

H1a Training the text structure knowledge application strategy or the summarization strategy affects the acquisition of academic writing skills more than training the language use strategy ( cognitive writing strategy hypothesis ).

H1b Training the text structure knowledge application strategy affects the skill of using genre specific structures to find and assign information more than training the summarization strategy or the language use strategy ( text structure strategy hypothesis ).

H1c Training the summarization strategy affects the skill of reducing text content while maintaining coherence more than training the text structure knowledge application strategy or the language use strategy ( summarization strategy hypothesis ).

H2a Undergraduates benefit from receiving informative tutoring feedback more than from receiving try-again feedback in terms of text quality of the abstract. Academic writing skill, coherence skill, text quality of the draft, reducing text while revising, and adding relevant information while revising are assumed to influence the text quality of the abstract ( undergraduates’ hypothesis ).

H2b Undergraduates and postgraduates benefit differently from feedback while revising concerning text quality of the abstract ( level of graduation hypothesis ).

H3 Undergraduates benefit more from receiving informative tutoring feedback after training to apply text structure knowledge concerning text quality of the abstract than from receiving informative tutoring feedback after training the summarization strategy or training the language use strategy. Academic writing skill, coherence skill, text quality of the draft, reducing text while revising, and adding relevant information while revising are assumed to influence the text quality of the abstract ( combination hypothesis ).

Materials and Methods

Participants and design.

Data were analyzed from 212 German-speaking students ( n female = 184, n male = 28). The sample included 179 undergraduate ( n female = 157, n male = 22) and 33 doctoral students (postgraduates; n female = 27, n male = 6) who were majoring in educational sciences ( n = 32), psychology ( n = 74), or teacher education ( n = 96) from the University of Freiburg ( n = 90) and the University of Education of Freiburg ( n = 122) in Germany. The mean age was 24.5 years (SD = 4.5).

The study was advertised with flyers on which the study was offered as a training course on writing academic articles. The course consisted of one session and was not part of participants’ study program. Researchers and participants were not in a relationship of dependency. All participants were aware of taking part in a research project and volunteered to participate. They could either fulfill part of the study program’s requirement to participate in empirical studies or receive 15 Euro per person for participation. The examiner handed out the financial reward in the laboratory after the experiment. Before beginning the experiment, the participants read a standardized explanation about ethical guidelines and provided written informed consent. Participants who declined to provide the informed consent were offered to withdraw from the experiment and still receive the financial reward. None declined or withdrew from the experiment. All data were anonymously collected and analyzed. All participants provided written informed consent for their collected data to be used anonymously for publications. All participants were informed about their results that they could identify via their personalized code. In addition, from references were offered to help them train their specific academic writing deficits.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the three conditions of our experimental pre–posttest intervention study: all groups were basically instructed about the structure of an empirical article. Following, one experimental group ( N = 71) received a training on how to apply text structure knowledge, the second experimental group ( N = 70) received a training on summarization, the control group ( N = 71) received a training on language use. In addition, half of each group received either informative tutoring feedback or try-again feedback directed at the writing process.

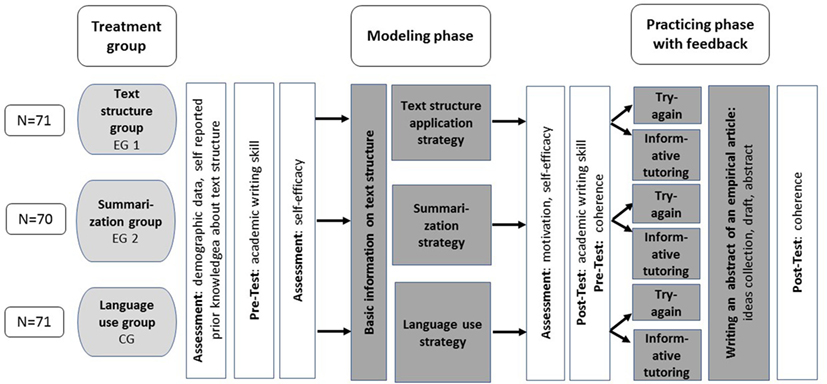

The experiment was conducted in a 2-h session in a university laboratory. Each participant enlisted for one date. In the session, all participants managed their time individually in a computer-based learning environment without interacting with other participants. Via the computer-based learning environment, all instructions were executed in writing, and all participants’ contributions were stored. The participants were randomly assigned to the treatment conditions in nearly equal numbers. Participants were not informed about the nature of their condition. The procedures of the study are presented in Figure 1 .

Figure 1 . Procedures of the study.

The experiment consisted of two phases: modeling phase and deliberate practice phase. Before the modeling phase, demographic data and self-reported prior knowledge about text structure were assessed. The participants were also tested on academic writing skill as well as on self-efficacy. Following the modeling phase, the participants were tested on their current motivation, and retested on self-efficacy and academic writing skill. Before and after the deliberate practice phase, the participants were tested on coherence skill.

In the modeling phase , the participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions of the experimental pre–posttest intervention study. They received basic training on how an empirical article is structured, after which they received writing strategy training according to their condition (i.e., training to apply text structure knowledge application strategy, text summarization strategy, or language use strategy). The training sessions were presented by a peer model in written learning journals, which the participants read at their own pace. The peer model illustrated and exemplified her own writing experience. She demonstrated aspects where she struggled and offered strategies to master the writing process effectively. In this phase, the participants were not allowed to take their own notes for two reasons: (1) control of time consumption and (2) control of elaboration depth.

In the deliberate practice phase , the participants were asked to write an abstract of an empirical research article. To this aim, all participants were presented with a cartoon about advantages and disadvantages of wearing school uniform. To produce the single text sections (theoretical background, research question, methods, results, and implications), the participants received instructions (e.g., ask a critical question that you want to check in your study) and collected their ideas in the computer-based learning environment. Subsequently, for the writing process half of each group was assigned to the try-again feedback condition and half to the informative tutoring feedback condition. After the peer model provided feedback, the text written so far was presented in the computer-based learning environment for revising. Feedback was twice provided by the peer model: first, after the participants collected ideas, and second, after the participants wrote a draft of the abstract.

Learning Journal

All participants read a learning journal that was presented in a computer-based learning environment by a peer model. For each writing strategy (i.e., text structure knowledge application strategy, text summarization strategy, and language use strategy), the peer model described when the strategy is useful and how the strategy can be applied; she then summarized the strategy and offered prompts for each strategy to master the writing challenge as follows.

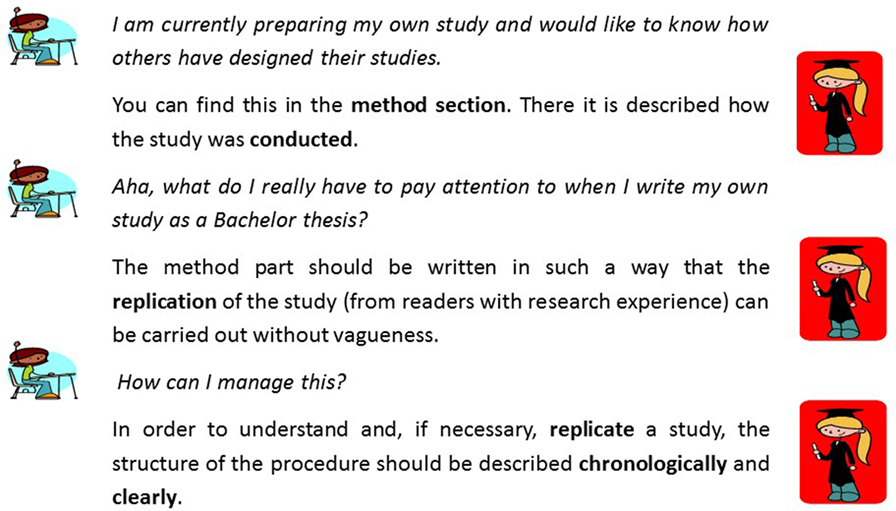

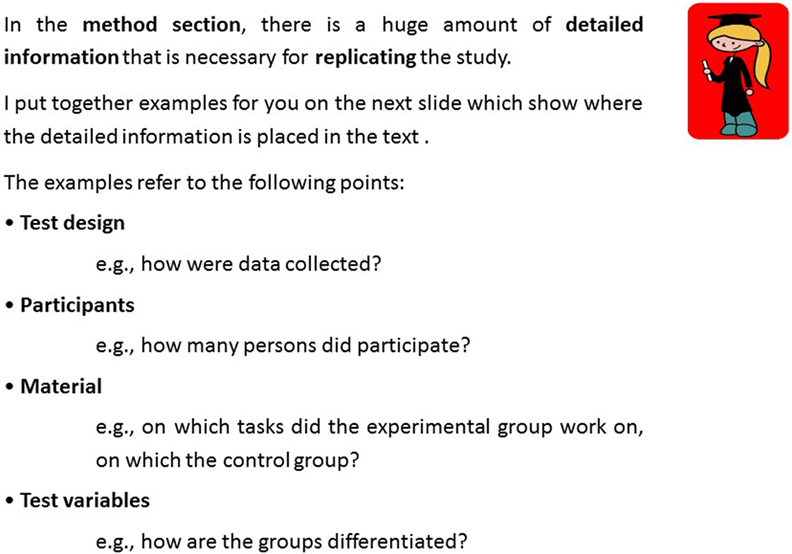

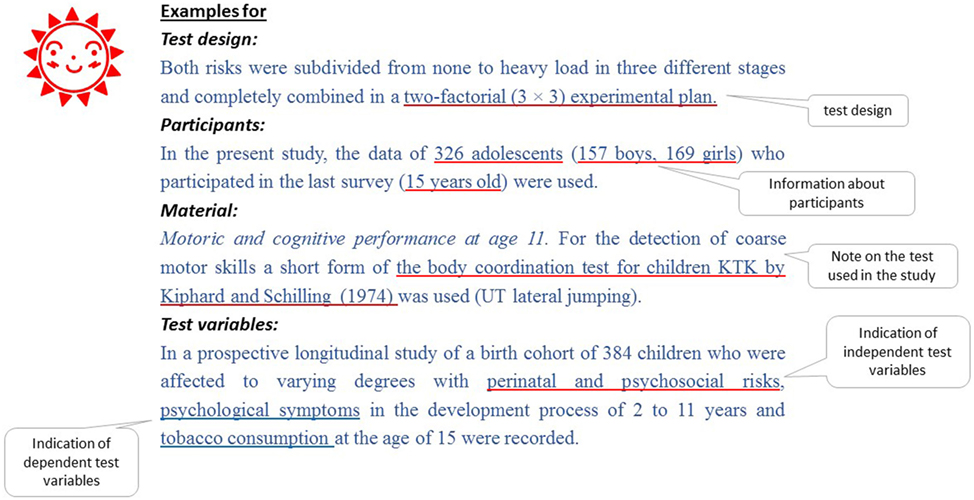

The learning journal text structure knowledge application strategy focused on the use of text structure knowledge: (1) what the text is about, (2) what is already known about the topic, (3) how the research was done (please see exemplarily Figures 2 – 4 ), (4) which research results were found and how the authors reached them, and (5) what these results mean and which conclusions can be drawn.

Figure 2 . Questions and answers concerning the orientation in the method section presented in the peer model’s learning journal.

Figure 3 . Function of the method section explained in the peer model’s learning journal.

Figure 4 . Examples for detailed information in the method section presented in the peer model’s learning journal.

The learning journal text summarization strategy focused on selecting and assigning text information: (1) how the topic is embedded in the research field, (2) which passages of a text should be selected and how they should be selected, (3) how to reduce information and redundancies, (4) how to choose keywords, and (5) how to write one’s own text.

The learning journal language use strategy focused on the communication in the science community: (1) what is the intention for communicating in a scientific community, (2) how can the writer prevent misunderstandings (i.e., consistency), (3) how can the writer show objectivity, (4) when and how are “I” formulations used, and (5) when and how are “we” formulations used?

All participants received a standardized feedback (i.e., try-again feedback or informative tutoring feedback) provided by the peer model for the first and the second revision, that is, before they transformed their ideas into a text, and before they finalized their abstract. Both types of feedback focused on monitoring the writing process: informative tutoring feedback provided concrete advices, whereas try-again feedback intended to rely on stored writing plans.

The informative tutoring feedback focused on giving concrete advice regarding writing deficits that are typical for beginning academic writers: (1) delete all redundancies from the text; (2) add information that makes the text easier to understand; and (3) revise the text to develop a whole unit by connecting sentences. For the second revision, the participants received an additional prompt to consider the readers’ perspective.

The try-again feedback focused on encouraging the participants to proceed. The participants received twice the prompt “Please revise the text you have written so far.”

Academic Writing Items

To assess academic writing skills we used a short-scale of an earlier study ( Wischgoll, 2016 ). The items were selected to assess writing skills, which support the development of a well-structured and informative text (i.e., text structure knowledge, application of text structure knowledge, and reduction of text content). One item captured the knowledge about the structure of an empirical article; the participants were asked to arrange headings. Five items captured the skill of applying text structure knowledge; for instance, the participants were asked to assign typical phrases to text sections such as methods or discussion and to give reasons for their decision. Four items captured the skill of reducing text content; the participants were asked, for instance, to name four keywords to adequately express the message of a text.

Coherence Items

Six items were developed to assess the writing skill coherence, which involves establishing meaning in a short passage. For instance, participants were asked to delete a superfluous sentence in the text or fill a gap in the text according to the provided annotation, such as an argument or an example.

Two experienced researchers who have been publishing and reviewing research articles for several years assigned all academic writing skill items to one of the contexts (text structure knowledge, application of text structure knowledge, and reduction of text content). The interrater reliability was excellent [ ICC (31) = 0.80] ( Fleiss, 2011 ). Four similarly experienced researchers judged the content validity of the coherence skill items, with an excellent interrater reliability [intraclass correlation coefficient ICC (31) > 0.90] ( Fleiss, 2011 ).

For all writing skill items, participants’ written answers were rated as correct or incorrect. To ensure reliability of the rating system, two raters conducted the rating independently, and a high level of interrater agreement was achieved [intraclass correlation coefficient ICC (31) > 0.80] ( Fleiss, 2011 ). Disagreement was resolved by discussion in all cases.

Overall Text Quality

Overall text quality was measured for the text written so far at three time points: first, the text after the participants had collected ideas as prompted according to each text section; second, the text after they had written their draft; and third, the text after they had revised their draft and finalized their abstract. Each time, the text quality was rated on a 7-point scale (1 = disastrous , 7 = excellent ) adapted from Cho et al. (2006) as an overall quality (see Wischgoll, 2016 ). The measurement was conducted after the experiment was completed. A student project assistant received about 10 h of training on the quality rating scale, which included practicing the judgment and discussing 40 cases. The abstracts were rated independently, with the research assistant and project assistant being unaware of the participants’ experimental condition and identity. A further 40 abstracts, 19% of the whole sample, were selected to calculate the interrater reliability. The intraclass correlation coefficient was ICC (21) > 0.80, which can be categorized as excellent ( Fleiss, 2011 ). Disagreement was resolved by discussion in all cases.

Text Content Improvement

Text content improvement was measured in the final abstract in comparison to the draft. We took into account the aspects reducing text while revising and adding relevant information while revising . (1) Reducing text while revising . We compared the draft and the abstract to find out whether irrelevant and secondary information was omitted while revising. Each text section was rated according to whether or not the text had been reduced and whether or not this decision contributed to the readability of the text. (2) Adding relevant information while revising . We compared the draft and the abstract to find out whether information that fosters the understanding of the text was added. Each text section was rated according to whether or not the text had been extended and whether or not this decision contributed to the readability of the text.

Additional Measures

Self-efficacy.

The self-efficacy scale focusing on academic writing was constructed using eight items according to the guide for constructing self-efficacy scales ( Bandura, 2006 ). The main aspects of academic writing skills, that is, application of text structure knowledge and reduction of text content, were taken into account. Participants were asked to rate how certain they were that, for example, they “can find certain information in an empirical research article” or “can find a precise and concise title for my Bachelor thesis.” For each written description, they rated their confidence from 0% ( cannot do it at all ) to 100% ( highly certain I can do it ) in 10% increments. The scale was administered before the modeling phase (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87) and after the modeling phase (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88). This scale was used to check the responsiveness to the treatment.

The following three reduced subscales of the Questionnaire on Current Motivation ( Vollmeyer and Rheinberg, 2006 ) were used to measure how motivated the participants were to develop their writing skills: challenge (five items; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74), probability of success (two items; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79), and anxiety (three items; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.73). The participants were asked to estimate their current motivation in relation to their academic writing development, rating each written description on a 7-point scale from 1 ( not true ) to 7 ( true ). The scale was administered after the modeling phase to check for differences between the treatment groups with regard to practicing writing.

For all statistical analyses, an alpha level of.05 was used. The effect size measure partial η 2 [0.01 as a small effect, 0.06 as a medium effect, and 0.14 as a large effect ( Cohen, 1988 )] was used. Normal distribution could be assumed for all analyses. To test the hypotheses, analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were calculated. In terms of testing the acquisition of academic writing skill (hypotheses 1a, 1b, and 1c), we controlled prior knowledge (H1a: pretest outcome on academic writing skills , H1b: prior knowledge of text structure knowledge application , H1c: prior knowledge of summarization skills ); in terms of testing text quality (hypotheses 2a and 3), we additionally controlled text quality of the draft and changes in the text ( reducing text while revising and adding relevant information while revising ); in terms of testing the difference between undergraduates’ and postgraduates’ text quality, a two-way ANCOVA with level of graduation and feedback as independent variables was calculated. Planned contrast was calculated with t -tests to gain information about the specific treatment conditions.

Pre-Analysis

Prior knowledge about text structure.

No differences were found across the conditions concerning “knowing the text structure of an empirical article” (item 1), F (2, 209) = 0.64, p = 0.53 and “arranging the headings of the text sections” (item 2), F (2, 209) = 0.18, p = 0.83.

Academic Writing Skills

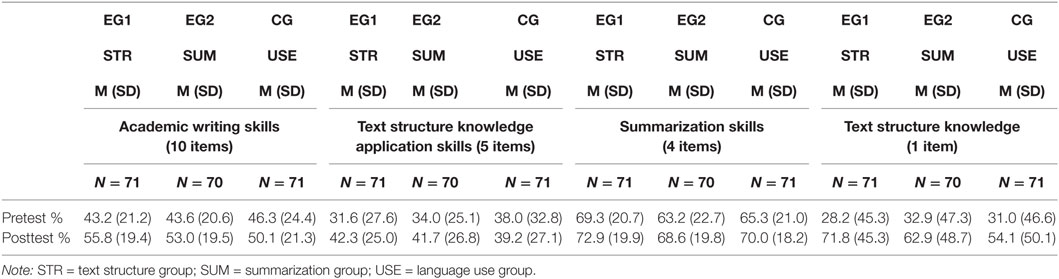

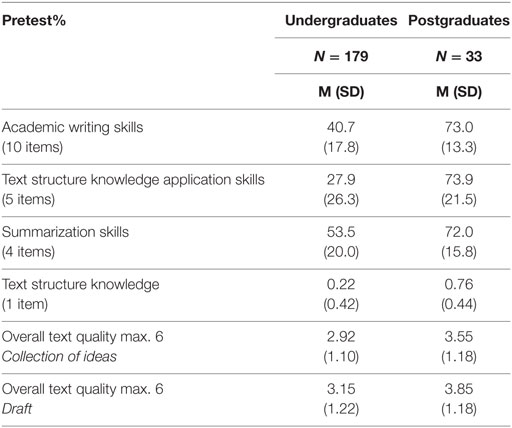

Academic writing skills were differentiated into text structure knowledge application skills and summarization skills. In the pretest, no significant differences were found across the conditions for academic writing skills, F (2, 209) = 0.35, p = 0.70, text structure knowledge application skills, F (2, 209) = 0.53, p = 0.59, and summarization skills, F (2, 209) = 1.38, p = 0.25. Table 2 shows the means and SDs for the pretest and posttest in each condition. The average pretest percentage for academic writing skills in the three conditions ranged from 45.2 to 47.5%, implying that the participants had some, but not a great deal of knowledge about academic writing skills. With respect to the subscales of the pretest, the average scores ranged from 32.1 to 37.2% for text structure knowledge application skills , and from 53.1 to 58.3% for summarization skills . Table 3 shows the means and SDs for undergraduates and postgraduates. These results indicate that the participants had only sparse knowledge about text structure and its application, but quite good knowledge about text summarization.

Table 2 . Means and SDs of academic writing skills, text structure knowledge application skills, and summarization skills in the strategy treatment groups.

Table 3 . Means and SDs of academic writing skills, text structure knowledge application skills, summarization skills, and overall text quality of undergraduates and postgraduates.

Significant differences in the pretest were found between undergraduates and postgraduates for academic writing skills, t (210) = −12.12, p < 0.001, r = 0.85, text structure application skills, t (210) = −10.88, p < 0.001, r = 0.55, and summarization skills, t (210) = −5.87, p < 0.001, r = 0.63. As postgraduates outperformed undergraduates, the results confirm the expectations about the difference in writing experience between novice and experienced writers.

Coherence Skill

In the pretest, no significant differences were found across the conditions, F (2, 209) = 0.41, p = 0.67. The results showed a significant difference between postgraduates and undergraduates, F (1, 210) = 26.77, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.11 , with the postgraduates (M = 0.62, SD = 0.22) outperforming the undergraduates (M = 0.41, SD = 0.22). See Table 4 for means and SDs.

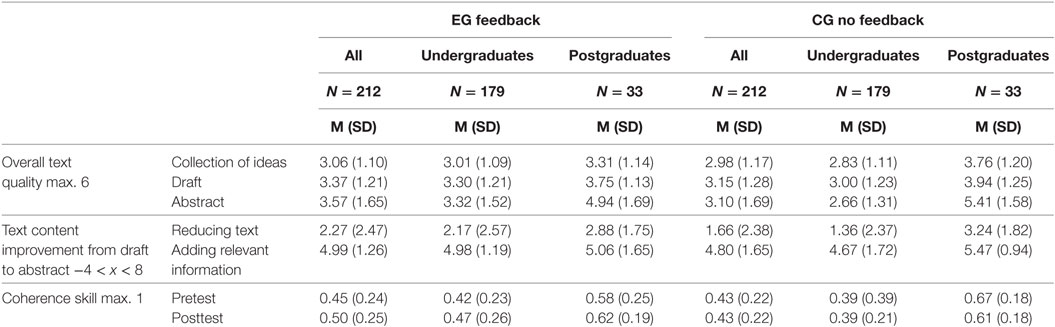

Table 4 . Means and SDs of text quality measured at three time points, reducing text and adding relevant information while revising text, and coherence in the feedback groups.

Text Quality

In the collection of ideas, postgraduates significantly outperformed the undergraduates in text quality, t (210) = −2.83, p = 0.007, r = 0.40 and in the draft, t (210) = −3.13, p = 0.003, r = 0.42. Table 3 shows the means and SDs for undergraduates and postgraduates.

A MANCOVA was calculated to assess whether there was a difference in motivation between the treatment groups. Using Pillai’s trace, no significant effect of interest, probability of success, and anxiety, V = 0.033, F (6, 416) = 1.17, p = 0.32, was found.

A dependent t -test was calculated to assess the responsiveness to the treatment; a strong, significant effect was found [ t (211) = −9.03, p < 0.001, r = 0.53]. The participants experienced significantly higher self-efficacy after the treatment (M post = 64.79, SD post = 11.63) than before (M pre = 59.58, SD pre = 12.39). This was true for each treatment group: language use group (i.e., control group) [M pre = 60.46, SD pre = 12.55; M post = 63.80, SD post = 13.07; t (70) = −3.70, p < 0.001, r = 0.40], summarization group [M pre = 59.91, SD pre = 12.48; M post = 65.84, SD post = 9.68; t (69) = −6.36, p = 0.001, r = 0.61], and text structure group [M pre = 58.38, SD pre = 12.22; M post = 64.73, SD post = 11.94; t (70) = −5.68, p < 0.001, r = 0.56]. It also applied when looking at the results separately for undergraduates and postgraduates, M pre = 70.27, SD pre = 8.47; M post = 72.09, SD post = 8.86; t (32) = −2.29, p = 0.029, r = 0.37.

Main Analyses

Hypothesis 1a, strategy hypothesis , proposed that training the text structure knowledge application strategy or the summarization strategy affects the acquisition of academic writing skills more than training the language use strategy. An ANCOVA was calculated using pretest outcome on academic writing skills as control variable.

The results show a significant difference between the treatment groups concerning the acquisition of academic writing skills, F (2, 208) = 5.13, p = 0.007, η p 2 = 0.05 . The academic writing skills in the pretest were significantly related to final academic writing skills, F (1, 208) = 232.20, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.53 . Planned contrasts revealed that acquisition of academic writing skills was significantly lower in the language use group (i.e., control group) than in the group that received text structure knowledge application strategy training, t (208) = 3.16, p = 0.002, η p 2 = 0.05 , and the group that received summarization strategy training, t (208) = 2.02, p = 0.045, η p 2 = 0.02 .

Hypothesis 1b, text structure strategy hypothesis , proposed that training the text structure knowledge application strategy affects the skill of using genre specific structures to find and assign information more than training the summarization strategy or the language use strategy. An ANCOVA was calculated using pretest outcome on prior knowledge of text structure knowledge application as control variable.

The results do not show a significant difference between the three groups concerning the acquisition of text structure knowledge application skills, F (2, 208) = 2.47, p = 0.09. Planned contrasts revealed that acquisition of text structure knowledge application skills was significantly higher in the group that received training to apply text structure application knowledge than in the group that received training to apply language use, t (208) = 2.16, p = 0.03, η g r o u p 2 = 0.02 . No significant differences were found between the group that received summarization training and the group that received training in applying text structure knowledge, t (208) = 1.53, p = 0.13. The third variable, prior knowledge of text structure knowledge application [ F (1, 208) = 178.75, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.46 ], was significantly related to acquisition of text structure knowledge application skills.

Hypothesis 1c, summarization strategy hypothesis , proposed that training the summarization strategy affects the skill of reducing text content while maintaining coherence more than training the text structure knowledge application strategy or the language use strategy. An ANCOVA was calculated using pretest outcome on prior knowledge of summarization skills as control variable.

The results do not show a significant difference between the three groups concerning the acquisition of summarization skills, F (2, 208) = 0.13, p = 0.88. Planned contrasts revealed that acquisition of summarization skills was not significantly higher in the group that received summarization strategy training than in the group that received training to apply language use, t (208) = −0.13, p = 0.89. No significant differences were found between the group that received text structure knowledge application strategy training and the group that received summarization strategy training, t (208) = 0.36, p = 0.72. The prior knowledge of summarization skills [ F (1, 208) = 85.04, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.29 ] was significantly related to acquisition of summarization skills.

Hypothesis 2a, undergraduates’ hypothesis , proposed that undergraduates benefit from receiving informative tutoring feedback more than from receiving try-again feedback in terms of text quality of the abstract. Furthermore, it was assumed that academic writing skill, coherence skill, text quality of the draft, reducing text while revising, and adding relevant information while revising influence the text quality of the abstract. An ANCOVA with text quality of the abstract as dependent variable was conducted. Academic writing skill, coherence skill, text quality of the draft, reducing text while revising , and adding relevant information while revising were considered as third variables. See Tables 2 – 4 for means and SDs.

The results show a significant difference between undergraduates who received informative tutoring feedback and undergraduates who received try-again feedback concerning the text quality of the abstract, F (1, 172) = 8.980, p = 0.003, η p 2 = 0.05 . The third variables coherence skill [ F (1, 172) = 2.054, p = 0.154], reducing text while revising [ F (1, 172) = 2.289, p = 0.132], and adding relevant information while revising [ F (1, 172) = 1.215, p = 0.272] were not significantly related to the text quality of the abstract. However, academic writing skills [ F (1, 172) = 8.359, p = 0.004, η p 2 = 0.05 ] and text quality of the draft [ F (1, 172) = 26.984, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.14 ] were significantly related to the text quality of the abstract.

Hypothesis 2b, level of graduation hypothesis , proposed that undergraduates and postgraduates benefit differently from receiving feedback while revising the texts they have written so far. A two-way ANCOVA with level of graduation and feedback as independent variables was conducted. See Tables 2 – 4 for means and SDs.

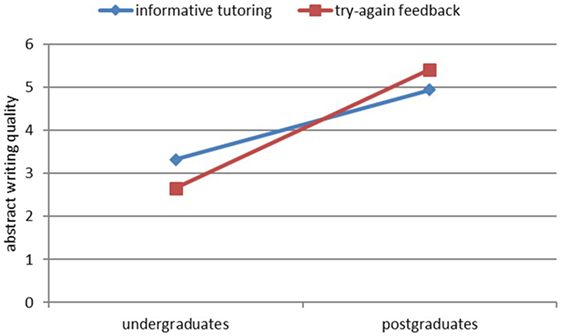

The main effect of feedback for revising was not significant, F (1, 208) = 0.11, p = 0.74. The main effect of level of graduation emerged as significant, F (1, 208) = 62.58, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.23 . The interaction between feedback for revising and level of graduation was significant, F (1, 208) = 4.22, p = 0.041, η p 2 = 0.02 . The findings are presented in Figure 5 .

Figure 5 . Interaction between level of graduation and feedback for revising.

Hypothesis 3, combination hypothesis , proposed that undergraduates benefit more from receiving informative tutoring feedback after training to apply text structure knowledge concerning text quality of the abstract than from receiving informative tutoring feedback after training summarization or training language use. Furthermore, it was assumed that academic writing skill, coherence skill, text quality of the draft, reducing text while revising, and adding relevant information while revising influence the text quality of the abstract. An ANCOVA with text quality of the abstract as dependent variable was conducted. Academic writing skill, coherence skill, text quality of the draft, reducing text while revising , and adding relevant information while revising were considered as third variables. See Tables 2 – 4 for means and SDs.

The results show no significant difference between the three treatment groups concerning the text quality of the abstract, F (2, 82) = 2.550, p = 0.084. Planned contrasts revealed no significant differences between the group that received informative tutoring feedback after training to apply text structure knowledge compared to the group that received informative tutoring feedback after training summarization, t (82) = −0.685, p = 0.495. However, planned contrasts revealed that text quality of the abstract was significantly lower in the group that received training to apply text structure knowledge compared to the control group that received language use, t (82) = −2.221, p = 0.029, η p 2 = 0.06 . The third variables coherence skill [ F (1, 82) = 0.679, p = 0.412], reducing text while revising [ F (2, 82) = 0.326, p = 0.570], and adding relevant information while revising [ F (2, 82) = 0.259, p = 0.612] were not significantly related to the text quality of the abstract. However, academic writing skills [ F (2, 82) = 4.135, p = 0.045, η p 2 = 0.05 ] and text quality of the draft [ F (2, 82) = 12.523, p = 0.001, η p 2 = 0.13 ] were significantly related to the text quality of the abstract.

This study investigated the effects of training the cognitive writing strategies summarization and application of text structure knowledge on academic writing skills, and of feedback for text revision to foster undergraduates’ and postgraduates’ text quality. Furthermore, it was tested whether training to apply text structure knowledge and receiving feedback for revising fosters undergraduates’ text quality significantly.

Concerning the cognitive writing strategy hypothesis , it was found that the groups that received cognitive strategy writing training outperformed the control group in terms of the acquisition of academic writing skills. This effect was found for the group that received the text structure knowledge application strategy training in the zone of desired effects ( Hattie and Timperley, 2007 ). Furthermore, the finding underlines the importance of prior knowledge in the form of writing experience, as the pretest outcome on academic writing skills explained over 50% of the variance.

More specifically, first, concerning the text structure strategy hypothesis , the group that received training on how to apply text structure knowledge significantly outperformed the control group in terms of using genre specific structures to find and assign information; however, contrary to the assumption, no differences were found between the group that received summarization training and the group that received a text structure knowledge application strategy training. Furthermore, the importance of prior knowledge was confirmed, as it explained around 50% of the variance. Second, concerning the summarization strategy hypothesis , the group that received training on how to summarize a text did not outperform either the control group or the group that received the text structure knowledge application strategy. The importance was confirmed as the pretest outcome on summarization skills explained nearly 30% of the variance. All groups already had high summarization values in the pretest, which increased further in the posttest.

Concerning the undergraduates’ hypothesis , the results confirm the findings by Hanna (1976) and Clariana (1990) that novice writers benefit from feedback that offers guidance through a challenging task, as it revealed that the undergraduates benefit from receiving informative tutoring feedback more than from receiving try-again feedback concerning text quality of the abstract. Furthermore, the result pointed out that deleting text and adding relevant information were not related to text quality. This result is in line with findings by Brown and Day (1983) and Hidi and Anderson (1986) who could show that the low text quality of beginning academic writers can be explained by deleting text. However, the finding underlines the importance of text revising and prior knowledge of academic writing skills for text quality of the abstract, as both together explained nearly 20% of variance.

Concerning the level of graduation hypothesis , the result is in line with the findings of Hanna (1976) and Clariana (1990) . Indeed, we extend their findings, as we found an expertise reversal effect ( Kalyuga et al., 1998 , 2003 ; Kalyuga, 2007 ). According to this effect, there is an interaction between the level of writing experience and the effectiveness of different instructional methods. In this sense, feedback that is effective for undergraduates can lose its effectiveness and even have negative consequences for postgraduates and vice versa . The text quality of the abstracts drafted by undergraduates who received informative tutoring feedback was higher than that of the undergraduates who received try-again feedback. On the other hand, the text quality of the abstracts drafted by postgraduates who received try-again feedback was higher than that of the postgraduates who received informative tutoring feedback. This insight confirms the assumption that support needs to be tailored to the individual learner’s writing experience and skills: undergraduates need support in monitoring the writing process to control and regulate developing coherent texts, whereas postgraduates can rely on stored writing plans and writing experience while revising their texts repeatedly. As a consequence, support for postgraduates might begin with elaborated feedback after writing ( Shute, 2008 ), which is individually aligned and administered ( Zimmerman and Kitsantas, 2002 ), whereas for undergraduates, elaborated feedback with guidance is already helpful while writing. In both cases, administered feedback should be aligned to the writer’s current prerequisites and needs to ensure that the writer is able to apply the feedback.

Concerning the combination hypothesis , the results did show no differences between the three groups. However, in contrast to the group that received a training to apply text structure knowledge text quality of the control group that received a language use strategy training was significantly higher. This result is unexpected. Whereas the combination of training to apply a text structure application strategy and training a self-monitoring strategy was proved as a promising means to foster undergraduates’ text quality ( Wischgoll, 2016 ), the combination of training a text structure application strategy and providing feedback while revising was it not. Rather, the results indicate, first, that feedback for revising is not beneficial for text quality in combination with a cognitive writing strategy such as summarization strategy or text structure application strategy, and second, that feedback for revising might be promising if it is administered in combination with a less complex writing strategy such as language use strategy.

In sum, the results confirm that undergraduates and postgraduates need support in academic writing. According to the findings of this study, support in text structure knowledge application, summarization, and revision should be aligned to the writing experience.

Hence, undergraduates should be prepared to know and apply the text structure of relevant genres. Although most postgraduates in this study were aware of the text structure, they should be encouraged to check their writing in terms of correct application of the text structure. Although both undergraduates and postgraduates reached high values in text summarization skills, the reduction of information in the revision process did not significantly contribute to the text quality. The question arises of what the reasons may be for the lacking efficacy of summarization skills on text quality and how summarization should be trained to be effective for improving text quality.

Generally, first, the results confirm the notion that revision contributes to improving text quality. MacArthur (2012) could define revision as a problem-solving process in which writers detect discrepancies between current and intended level of text quality and consider alternatives. In this study, it became apparent that undergraduates and postgraduates did benefit from feedback that was tailored to their needs in the revision process. Specifically, undergraduates benefited from informative tutoring feedback in terms of higher text quality. The reason for this might be that informative tutoring feedback offered guidance to draw attention on discrepancies between actual and intended level of text quality. Furthermore, from the improved text quality one could conclude that feedback encouraged considering alternatives. Hence, one can see feedback as a suitable means to improve text quality.

Second, the results revealed that feedback that accompanies the writer deliberately while revising does not complement training a certain writing strategy such as text structure knowledge application or summarization strategy in terms of improving text quality. This finding is in contrast to Wischgoll (2016) who could show that training one cognitive and one metacognitive writing strategy results in improved text quality, and thus, confirmed that cognitive and metacognitive strategy training complement each other ( Veenman and Beishuizen, 2004 ). However, results revealed that feedback did correspond well with training the language use strategy. One can reason that applying strategies recently learnt and reply to feedback while revising might be overwhelming for beginning academic writers. Writing trainings that are sequenced in this way—training a cognitive writing strategy and receiving feedback while text revision—might lack a phase of consolidation. Thus, one can conclude that feedback should be administered in writing trainings independently to strategy trainings or only in combination with strategies, which are less complex such as the language use strategy.

Third, the study took into account writing performance of undergraduates and postgraduates. Results revealed that depending on the level of writing experience writers benefited from different kinds of elaborated feedback. This finding can be explained by Kellogg’s ( Kellogg, 2008 ) model of cognitive development of writing skill. He distinguished advanced writers into knowledge transformers and knowledge crafters. Whereas knowledge crafters already can rely on stored writing plans and writing experience, knowledge transformers have still to develop and consolidate these skills. Consequently, support has to be tailored according to writing experience. Thus, results confirmed that writing experience is a crucial indicator for aligning writing support.

The conclusion might be derived that undergraduates benefit from support during text revision as they lack the writing experience to be able to rely on stored writing plans. Feedback that provides orientation in terms of juggling processes of planning, translating, and reviewing helps novice writers to master the demands of writing. On the other hand, if postgraduates receive feedback while writing, they might be “disrupted” in applying these stored writing plans. Thus, postgraduates might benefit from individually tailored feedback after finishing the text to their satisfaction.

Fourth, the results confirm Kellogg’s ( Kellogg, 2008 ) notion that observation and practicing is a promising means to improve academic writing skills and text quality. Results pointed out that by observation undergraduates’ academic writing skills increased and by practicing writing and revising text quality improved effectively; that furthermore, the instructional design used in this study is suitable for higher education as learners improved efficiently in an even short-time intervention. The learning environment did allow each individual learner to process in his or her own pace. Observation was operationalized by reading learning journals and practicing by writing and revising the own text; thus, learners could emphasize their learning and writing process according to the individual needs. Therefrom one can derive that e-learning courses that offer support to develop single aspects of academic writing such as text structure knowledge or language use might be an attractive proposition for beginning academic writers.

Limitations

The presented research is limited by several aspects. First, writing is a complex process and training can only apply single aspects at a time. Further strategies in combination with experience-related feedback might also affect writing skills and text quality. Second, academic writing skill, coherence skill are multifaceted and in some ways related, which makes the assessment challenging. To meet these requirements, the instruments need further refinement respectively further instruments need to be developed. Third, as the participants were primarily female and the group of postgraduates was small, the generalizability of the results is limited.

Future Directions

Future research concerning postgraduates’ writing should focus on analyzing the gaps while composing a more complex text such as the theoretical background of an article. This would enable the requirements for supporting academic writing development on a more elaborated level to be determined. Future research concerning undergraduates’ needs should focus on the effectiveness of implementing basic writing courses that impart and train academic writing skills in the curriculum.

Furthermore, research on combining writing strategies and feedback aligned to writing experience is still needed. Indeed, fostering postgraduates’ text quality should be analyzed in more detail. This could be accomplished by contrasting case studies or by including a greater number of postgraduate participants. Establishing coherence of an academic text comprises the same challenges in all genres; thus, the studies could also be designed in a multidisciplinary manner.

Combination studies on academic writing could also include peer support instead of general feedback aligned to writing experience. Peer tutoring ( Slavin, 1990 ; Topping, 1996 , 2005 ) in higher education might be beneficial for postgraduates: they might feel less inhibited to discuss writing-related problems with their peers, who are more in tune with the current challenges in becoming an academic writer. Moreover, co-constructive discussions can promote the writing process. On the other hand, peer mentoring ( Topping, 2005 ) might be supportive for undergraduates. From a more experienced peer, undergraduates can receive consolidated support on how to master basic challenges in academic writing such as structuring the text and revising the text. Furthermore, metacognitive regulation in mentoring and tutoring ( De Backer et al., 2016 ) should also be considered as a crucial factor that contributes to improving writing skills.

The study showed that even short-time practice can promote text quality. In addition, in terms of writing development, the notion of Kellogg and colleagues ( Kellogg and Raulerson, 2007 ; Kellogg, 2008 ; Kellogg and Whiteford, 2009 ) that expertise in writing develops with practice was supported. The results imply that writing strategies such as text structure knowledge application strategy should be trained to achieve skills that promote coherence, and that feedback should be aligned to writing experience to improve text quality.

Ethics Statement

All participants volunteered and provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the German Psychological Society (DGPs) ethical guidelines (2004, CIII) as well as APA ethical standards. According to the German Psychological Society’s ethical commission, approval from an institutional research board only needs to be obtained, if funding is subject to ethical approval by an Institutional Review Board. This research was reviewed and approved by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Germany (BMBF), which did not require additional Institutional Review Board approval. All data were collected and analyzed anonymously.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the project “Learning the Science of Education (LeScEd).” LeScEd is a project of the Competence Network Empirical Research on Education and Teaching (KeBU) of the University of Freiburg and the University of Education, Freiburg. LeScEd is part of the BMBF Funding Initiative “Modeling and Measuring Competencies in Higher Education” (grant number 01PK11009B). The article processing charge was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Albert-Ludwigs-University Freiburg in the funding programme Open Access Publishing. The author would like to thank the student project assistants E. Ryschka, N. Lobmüller, and A. Prinz for their dedicated contribution.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Google Scholar

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control . New York: Freeman.

Bandura, A. (2006). “Guide for creating self-efficacy scales,” in Self-efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents , eds F. Pajares and T. Urdan (Greenwich, CT: IAP), 307–337.

Bereiter, C., and Scardamalia, M. (1987). The Psychology of Written Composition . Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Braaksma, M. A., Rijlaarsdam, G., Van den Bergh, H., and van Hout-Wolters, B. H. M. (2004). Observational learning and its effects on the orchestration of writing processes. Cogn. Instr. 22, 1–36. doi: 10.2307/3233849

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Brown, A. L., and Day, J. D. (1983). Macrorules for summarizing texts: the development of expertise. J. Verbal. Learn. Verbal. Behav. 22, 1–14. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(83)80002-4

Butler, D. L., and Winne, P. H. (1995). Feedback and self-regulated learning: a theoretical synthesis. Rev. Educ. Res. 65, 245–281. doi:10.3102/00346543065003245

Chanquoy, L. (2008). “Revision processes,” in The SAGE Handbook of Writing Development , eds R. Beard, D. Myhill, J. Riley, and M. Nystrand (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE), 80–97.

Cho, K., and MacArthur, C. (2010). Student revision with peer and expert reviewing. Learn. Instr. 20, 328–338. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.08.006

Cho, K., Schunn, C. D., and Charney, D. (2006). Commenting on writing typology and perceived helpfulness of comments from novice peer reviewers and subject matter experts. Writ. Commun. 23, 260–294. doi:10.1177/0741088306289261

Clariana, R. B. (1990). A comparison of answer until correct feedback and knowledge of correct response feedback under two conditions of contextualization. J. Comput. Based Instr. 17, 125–129.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences . Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Collins, A., Brown, J. S., and Newman, S. E. (1989). Cognitive apprenticeship: teaching the crafts of reading, writing, and mathematics. Know. Learn. Instr. 18, 32–42.

Corno, L., and Snow, R. E. (1986). “Adapting teaching to individual differences among learners,” in Handbook of Research on Teaching , ed. M. C. Wittrock (New York: Macmillan), 605–629.

De Backer, L., Van Keer, H., and Valcke, M. (2016). Eliciting reciprocal peer-tutoring groups’ metacognitive regulation through structuring and problematizing scaffolds. J. Exp. Educ. 84, 804–828. doi:10.1080/00220973.2015.1134419

Donker, A., de Boer, H., Kostons, D., van Ewijk, C. D., and Van der Werf, M. (2014). Effectiveness of learning strategy instruction on academic performance: a meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 11, 1–26. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2013.11.002

Englert, C. S. (2009). Connecting the dots in a research program to develop, implement, and evaluate strategic literacy interventions for struggling readers and writers. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 24, 104–120. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5826.2009.00284.x

Englert, C. S., and Hiebert, E. H. (1984). Children’s developing awareness of text structures in expository materials. J. Educ. Psychol. 76, 65–74. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.76.1.65

Englert, C. S., and Thomas, C. C. (1987). Sensitivity to text structure in reading and writing: a comparison between learning disabled and non-learning disabled students. Learn. Disabil. Q. 10, 93–105. doi:10.2307/1510216

Fitzgerald, J. (1992). Knowledge in Writing. Illustration from Revision Studies . New York: Springer.

Fleiss, J. L. (2011). Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments , Vol. 73. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Graesser, A. C., McNamara, D. S., Louwerse, M. M., and Cai, Z. (2004). Coh-Metrix: analysis of text on cohesion and language. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 36, 193–202. doi:10.3758/BF03195564

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Graesser, A. C., Singer, M., and Trabasso, T. (1994). Constructing inferences during narrative text comprehension. Psychol. Rev. 101, 371–395. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.101.3.371

Graham, S. (2006). “Strategy instruction and the teaching of writing: a meta-analysis,” in Handbook of Writing Research , eds C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, and J. Fitzgerald (New York: Guilford Press), 187–207.

Graham, S., Gillespie, A., and McKeown, D. (2013). Writing: importance, development, and instruction. Read. Writ. 26, 1–15. doi:10.1007/s11145-012-9395-2

Graham, S., and Perin, D. (2007). A meta-analysis of writing instruction for adolescent students. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 445–476. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.445

Hanna, G. S. (1976). Effects of total and partial feedback in multiple-choice testing upon learning. J. Educ. Res. 69, 202–205. doi:10.1080/00220671.1976.10884873

Hattie, J., and Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 77, 81–112. doi:10.3102/003465430298487

Hayes, J. R. (2004). “What triggers revision?” in Revision: Cognitive and Instructional Processes , Vol. 13, eds L. Allal, L. Chanquoy, and P. Largy (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers), 9–20.

Hayes, J. R., Flower, L., Schriver, K. A., Stratman, J. F., and Carey, L. (1987). “Cognitive processes in revision,” in Reading, Writing, and Language Processing: Advances in Psycholinguistics , Vol. 2, ed. S. Rosenberg (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 176–241.

Hidi, S., and Anderson, V. (1986). Producing written summaries: task demands, cognitive operations, and implications for instruction. Rev. Educ. Res. 56, 473–493. doi:10.3102/00346543056004473

Hiebert, E. H., Englert, C. S., and Brennan, S. (1983). Awareness of text structure in recognition and production of expository discourse. J. Literacy Res. 15, 63–79. doi:10.1080/10862968309547497

Kalyuga, S. (2007). Expertise reversal effect and its implications for learner-tailored instruction. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 19, 509–539. doi:10.1007/s10648-007-9054-3

Kalyuga, S., Ayres, P., Chandler, P., and Sweller, J. (2003). The expertise reversal effect. Educ. Psychol. 38, 23–31. doi:10.1207/S15326985EP3801_4

Kalyuga, S., Chandler, P., and Sweller, J. (1998). Levels of expertise and instructional design. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 40, 1–17. doi:10.1518/001872098779480587

Kellogg, R. T. (2008). Training writing skills: a cognitive developmental perspective. J. Writ. Res. 1, 1–26. doi:10.17239/jowr-2008.01.01.1

Kellogg, R. T., and Raulerson, B. A. (2007). Improving the writing skills of college students. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 14, 237–242. doi:10.3758/BF03194058

Kellogg, R. T., and Whiteford, A. P. (2009). Training advanced writing skills: the case for deliberate practice. Educ. Psychol. 44, 250–266. doi:10.1080/00461520903213600

Kintsch, W., and Van Dijk, T. A. (1978). Toward a model of text comprehension and production. Psychol. Rev. 85, 363–394. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.85.5.363

Koedinger, K. R., and Aleven, V. (2007). Exploring the assistance dilemma in experiments with cognitive tutors. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 19, 239–264. doi:10.1007/s10648-007-9049-0

Li, J. (2014). Examining genre effects on test takers’ summary writing performance. Assess. Writ. 22, 75–90. doi:10.1016/j.asw.2014.08.003

MacArthur, C. A. (2012). “Evaluation and revision,” in Past, Present, and Future Contributions of Cognitive Writing Research to Cognitive Psychology , ed. V. W. Berninger (New York, NY: Psychology Press), 461–483.

MacArthur, C. A., Philippakos, Z. A., and Ianetta, M. (2015). Self-regulated strategy instruction in college developmental writing. J. Educ. Psychol. 107, 855–867. doi:10.1037/edu0000011

McNamara, D. S., Kintsch, E., Songer, N. B., and Kintsch, W. (1996). Are good texts always better? Interactions of text coherence, background knowledge, and levels of understanding in learning from text. Cogn. Instr. 14, 1–43. doi:10.1207/s1532690xci1401_1

Moreno, R. (2004). Decreasing cognitive load for novice students: effects of explanatory versus corrective feedback in discovery-based multimedia. Instr. Sci. 32, 99–113. doi:10.1023/B:TRUC.0000021811.66966.1d

Narciss, S., and Huth, K. (2004). “How to design informative tutoring feedback for multimedia learning,” in Instructional Design for Multimedia Learning , eds H. M. Niegermann, D. Leutner, and R. Brunken (Munster: Waxmann), 181–195.

Nelson, M. M., and Schunn, C. D. (2009). The nature of feedback: how different types of peer feedback affect writing performance. Instr. Sci. 37, 375–401. doi:10.1007/s11251-008-9053-x

Nicol, D. J., and Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Stud. Higher Educ. 31, 199–218. doi:10.1080/03075070600572090

Rosenthal, T. L., and Zimmerman, B. J. (1978). Social Learning and Cognition . New York: Academic Press.

Sanders, T., and Sanders, J. (2006). “Text and text analysis,” in Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics , 2nd Edn, ed. K. Brown (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 597–621.

Sanders, T., Spooren, W., and Noordman, L. (1992). Toward a taxonomy of coherence relations. Discourse Process. 15, 1–35. doi:10.1080/01638539209544800

Schunk, D. H. (1987). Peer models and children’s behavioral change. Rev. Educ. Res. 57, 149–174. doi:10.3102/00346543057002149

Schunk, D. H. (1991). Learning Theories: An Educational Perspective . New York: Merrill.

Schunk, D. H., and Zimmerman, B. J. (1997). Social origins of self-regulatory competence. Educ. Psychol. 32, 195–208. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep3204_1

Shute, V. J. (2008). Focus on formative feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 78, 153–189. doi:10.3102/003465430731379

Slavin, R. E. (1990). Cooperative Learning: Theory, Research, and Practice . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Sommers, N. (1980). Revision strategies of student writers and experienced adult writers. Coll. Compos. Commun. 31, 378–388. doi:10.2307/356588

Spivey, N. N. (1990). Transforming texts constructive processes in reading and writing. Writ. Commun. 7, 256–287. doi:10.1177/0741088390007002004

Swales, J. (1990). Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings . Cambridge: University Press.

Topping, K. J. (1996). The effectiveness of peer tutoring in further and higher education: a typology and review of the literature. Higher Educ. 32, 321–345. doi:10.1007/BF00138870

Topping, K. J. (2005). Trends in peer learning. Educ. Psychol. 25, 631–645. doi:10.1080/01443410500345172

Van Dijk, T. A., and Kintsch, W. (1983). Strategies of Discourse Comprehension . New York: Academic Press.

Veenman, M. V., and Beishuizen, J. J. (2004). Intellectual and metacognitive skills of novices while studying texts under conditions of text difficulty and time constraint. Learn. Instr. 14, 621–640. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2004.09.004

Veenman, M. V., Wilhelm, P., and Beishuizen, J. J. (2004). The relation between intellectual and metacognitive skills from a developmental perspective. Learn. Instr. 14, 89–109. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2003.10.004

Vollmeyer, R., and Rheinberg, F. (2006). Motivational effects on self-regulated learning with different tasks. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 18, 239–253. doi:10.1007/s10648-006-9017-0

Wischgoll, A. (2016). Combined training of one cognitive and one metacognitive strategy improves academic writing skills. Front. Psychol. 7:187. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00187

Witte, S. P., and Faigley, L. (1981). Coherence, cohesion, and writing quality. Coll. Compos. Commun. 32, 189–204. doi:10.2307/356693

Zimmerman, B. J., and Kitsantas, A. (2002). Acquiring writing revision and self-regulatory skill through observation and emulation. J. Educ. Psychol. 94, 660. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.94.4.660

Keywords: coherence, feedback, higher education, text quality, writing strategies

Citation: Wischgoll A (2017) Improving Undergraduates’ and Postgraduates’ Academic Writing Skills with Strategy Training and Feedback. Front. Educ. 2:33. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00033

Received: 01 March 2017; Accepted: 26 June 2017; Published: 21 July 2017

Reviewed by:

Copyright: © 2017 Wischgoll. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anke Wischgoll, anke.wischgoll@psychologie.uni-freiburg.de

The Process of Research Writing

(19 reviews)

Steven D. Krause, Eastern Michigan University

Copyright Year: 2007

Publisher: Steven D. Krause

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Kevin Kennedy, Adjunct Professor, Bridgewater State University on 12/2/22

I think this book would make an excellent supplement to other class material in a class focused on writing and research. It helps a lot with the "why"s of research and gives a high-level overview. read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 3 see less

I think this book would make an excellent supplement to other class material in a class focused on writing and research. It helps a lot with the "why"s of research and gives a high-level overview.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

The book is accurate, and talks a lot about different ways to view academic writing

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

This would be quite relevant for a student early on the college journey who is starting to complete research-based projects.

Clarity rating: 4

The text is clear and concise, though that conciseness sometimes leads to less content than I'd like

Consistency rating: 5

The book is consistent throughout

Modularity rating: 4