Browse all our research projects by topic We have funded more than 150 external research projects across a range of themes over the last five years

- Share on Twitter

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Facebook

- Share on WhatsApp

- Share by email

- Link Copy link

Please click below to see the research projects we've funded on the following topics.

- Analytics and data

- Children and young people

- Commissioning

- Community and voluntary

- Digital technology

- Efficiency and productivity

- Emergency medicine

- End of life care

- Funding and sustainability

- Improvement science

- Inequalities

- Integrated care

- Long-term conditions

- Mental health

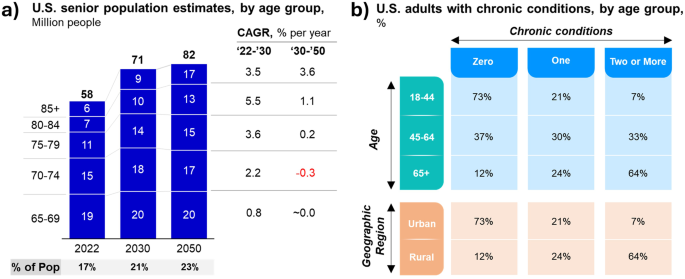

- Older people

- Patient experience

- Patient safety

- Person-centred care

- Primary care

- Public health

- Quality improvement

- Quality of care

- Social care

- Social determinants of health

Share this page:

Health Foundation @HealthFdn

- Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

The Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Quick links

- News and media

- Events and webinars

Hear from us

Receive the latest news and updates from the Health Foundation

- 020 7257 8000

- [email protected]

- The Health Foundation Twitter account

- The Health Foundation LinkedIn account

- The Health Foundation Facebook account

Copyright The Health Foundation 2024. Registered charity number 286967.

- Accessibility

- Anti-slavery statement

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

Research Topics & Ideas: Healthcare

100+ Healthcare Research Topic Ideas To Fast-Track Your Project

Finding and choosing a strong research topic is the critical first step when it comes to crafting a high-quality dissertation, thesis or research project. If you’ve landed on this post, chances are you’re looking for a healthcare-related research topic , but aren’t sure where to start. Here, we’ll explore a variety of healthcare-related research ideas and topic thought-starters across a range of healthcare fields, including allopathic and alternative medicine, dentistry, physical therapy, optometry, pharmacology and public health.

NB – This is just the start…

The topic ideation and evaluation process has multiple steps . In this post, we’ll kickstart the process by sharing some research topic ideas within the healthcare domain. This is the starting point, but to develop a well-defined research topic, you’ll need to identify a clear and convincing research gap , along with a well-justified plan of action to fill that gap.

If you’re new to the oftentimes perplexing world of research, or if this is your first time undertaking a formal academic research project, be sure to check out our free dissertation mini-course. In it, we cover the process of writing a dissertation or thesis from start to end. Be sure to also sign up for our free webinar that explores how to find a high-quality research topic.

Overview: Healthcare Research Topics

- Allopathic medicine

- Alternative /complementary medicine

- Veterinary medicine

- Physical therapy/ rehab

- Optometry and ophthalmology

- Pharmacy and pharmacology

- Public health

- Examples of healthcare-related dissertations

Allopathic (Conventional) Medicine

- The effectiveness of telemedicine in remote elderly patient care

- The impact of stress on the immune system of cancer patients

- The effects of a plant-based diet on chronic diseases such as diabetes

- The use of AI in early cancer diagnosis and treatment

- The role of the gut microbiome in mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety

- The efficacy of mindfulness meditation in reducing chronic pain: A systematic review

- The benefits and drawbacks of electronic health records in a developing country

- The effects of environmental pollution on breast milk quality

- The use of personalized medicine in treating genetic disorders

- The impact of social determinants of health on chronic diseases in Asia

- The role of high-intensity interval training in improving cardiovascular health

- The efficacy of using probiotics for gut health in pregnant women

- The impact of poor sleep on the treatment of chronic illnesses

- The role of inflammation in the development of chronic diseases such as lupus

- The effectiveness of physiotherapy in pain control post-surgery

Topics & Ideas: Alternative Medicine

- The benefits of herbal medicine in treating young asthma patients

- The use of acupuncture in treating infertility in women over 40 years of age

- The effectiveness of homoeopathy in treating mental health disorders: A systematic review

- The role of aromatherapy in reducing stress and anxiety post-surgery

- The impact of mindfulness meditation on reducing high blood pressure

- The use of chiropractic therapy in treating back pain of pregnant women

- The efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine such as Shun-Qi-Tong-Xie (SQTX) in treating digestive disorders in China

- The impact of yoga on physical and mental health in adolescents

- The benefits of hydrotherapy in treating musculoskeletal disorders such as tendinitis

- The role of Reiki in promoting healing and relaxation post birth

- The effectiveness of naturopathy in treating skin conditions such as eczema

- The use of deep tissue massage therapy in reducing chronic pain in amputees

- The impact of tai chi on the treatment of anxiety and depression

- The benefits of reflexology in treating stress, anxiety and chronic fatigue

- The role of acupuncture in the prophylactic management of headaches and migraines

Topics & Ideas: Dentistry

- The impact of sugar consumption on the oral health of infants

- The use of digital dentistry in improving patient care: A systematic review

- The efficacy of orthodontic treatments in correcting bite problems in adults

- The role of dental hygiene in preventing gum disease in patients with dental bridges

- The impact of smoking on oral health and tobacco cessation support from UK dentists

- The benefits of dental implants in restoring missing teeth in adolescents

- The use of lasers in dental procedures such as root canals

- The efficacy of root canal treatment using high-frequency electric pulses in saving infected teeth

- The role of fluoride in promoting remineralization and slowing down demineralization

- The impact of stress-induced reflux on oral health

- The benefits of dental crowns in restoring damaged teeth in elderly patients

- The use of sedation dentistry in managing dental anxiety in children

- The efficacy of teeth whitening treatments in improving dental aesthetics in patients with braces

- The role of orthodontic appliances in improving well-being

- The impact of periodontal disease on overall health and chronic illnesses

Tops & Ideas: Veterinary Medicine

- The impact of nutrition on broiler chicken production

- The role of vaccines in disease prevention in horses

- The importance of parasite control in animal health in piggeries

- The impact of animal behaviour on welfare in the dairy industry

- The effects of environmental pollution on the health of cattle

- The role of veterinary technology such as MRI in animal care

- The importance of pain management in post-surgery health outcomes

- The impact of genetics on animal health and disease in layer chickens

- The effectiveness of alternative therapies in veterinary medicine: A systematic review

- The role of veterinary medicine in public health: A case study of the COVID-19 pandemic

- The impact of climate change on animal health and infectious diseases in animals

- The importance of animal welfare in veterinary medicine and sustainable agriculture

- The effects of the human-animal bond on canine health

- The role of veterinary medicine in conservation efforts: A case study of Rhinoceros poaching in Africa

- The impact of veterinary research of new vaccines on animal health

Topics & Ideas: Physical Therapy/Rehab

- The efficacy of aquatic therapy in improving joint mobility and strength in polio patients

- The impact of telerehabilitation on patient outcomes in Germany

- The effect of kinesiotaping on reducing knee pain and improving function in individuals with chronic pain

- A comparison of manual therapy and yoga exercise therapy in the management of low back pain

- The use of wearable technology in physical rehabilitation and the impact on patient adherence to a rehabilitation plan

- The impact of mindfulness-based interventions in physical therapy in adolescents

- The effects of resistance training on individuals with Parkinson’s disease

- The role of hydrotherapy in the management of fibromyalgia

- The impact of cognitive-behavioural therapy in physical rehabilitation for individuals with chronic pain

- The use of virtual reality in physical rehabilitation of sports injuries

- The effects of electrical stimulation on muscle function and strength in athletes

- The role of physical therapy in the management of stroke recovery: A systematic review

- The impact of pilates on mental health in individuals with depression

- The use of thermal modalities in physical therapy and its effectiveness in reducing pain and inflammation

- The effect of strength training on balance and gait in elderly patients

Topics & Ideas: Optometry & Opthalmology

- The impact of screen time on the vision and ocular health of children under the age of 5

- The effects of blue light exposure from digital devices on ocular health

- The role of dietary interventions, such as the intake of whole grains, in the management of age-related macular degeneration

- The use of telemedicine in optometry and ophthalmology in the UK

- The impact of myopia control interventions on African American children’s vision

- The use of contact lenses in the management of dry eye syndrome: different treatment options

- The effects of visual rehabilitation in individuals with traumatic brain injury

- The role of low vision rehabilitation in individuals with age-related vision loss: challenges and solutions

- The impact of environmental air pollution on ocular health

- The effectiveness of orthokeratology in myopia control compared to contact lenses

- The role of dietary supplements, such as omega-3 fatty acids, in ocular health

- The effects of ultraviolet radiation exposure from tanning beds on ocular health

- The impact of computer vision syndrome on long-term visual function

- The use of novel diagnostic tools in optometry and ophthalmology in developing countries

- The effects of virtual reality on visual perception and ocular health: an examination of dry eye syndrome and neurologic symptoms

Topics & Ideas: Pharmacy & Pharmacology

- The impact of medication adherence on patient outcomes in cystic fibrosis

- The use of personalized medicine in the management of chronic diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease

- The effects of pharmacogenomics on drug response and toxicity in cancer patients

- The role of pharmacists in the management of chronic pain in primary care

- The impact of drug-drug interactions on patient mental health outcomes

- The use of telepharmacy in healthcare: Present status and future potential

- The effects of herbal and dietary supplements on drug efficacy and toxicity

- The role of pharmacists in the management of type 1 diabetes

- The impact of medication errors on patient outcomes and satisfaction

- The use of technology in medication management in the USA

- The effects of smoking on drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics: A case study of clozapine

- Leveraging the role of pharmacists in preventing and managing opioid use disorder

- The impact of the opioid epidemic on public health in a developing country

- The use of biosimilars in the management of the skin condition psoriasis

- The effects of the Affordable Care Act on medication utilization and patient outcomes in African Americans

Topics & Ideas: Public Health

- The impact of the built environment and urbanisation on physical activity and obesity

- The effects of food insecurity on health outcomes in Zimbabwe

- The role of community-based participatory research in addressing health disparities

- The impact of social determinants of health, such as racism, on population health

- The effects of heat waves on public health

- The role of telehealth in addressing healthcare access and equity in South America

- The impact of gun violence on public health in South Africa

- The effects of chlorofluorocarbons air pollution on respiratory health

- The role of public health interventions in reducing health disparities in the USA

- The impact of the United States Affordable Care Act on access to healthcare and health outcomes

- The effects of water insecurity on health outcomes in the Middle East

- The role of community health workers in addressing healthcare access and equity in low-income countries

- The impact of mass incarceration on public health and behavioural health of a community

- The effects of floods on public health and healthcare systems

- The role of social media in public health communication and behaviour change in adolescents

Examples: Healthcare Dissertation & Theses

While the ideas we’ve presented above are a decent starting point for finding a healthcare-related research topic, they are fairly generic and non-specific. So, it helps to look at actual dissertations and theses to see how this all comes together.

Below, we’ve included a selection of research projects from various healthcare-related degree programs to help refine your thinking. These are actual dissertations and theses, written as part of Master’s and PhD-level programs, so they can provide some useful insight as to what a research topic looks like in practice.

- Improving Follow-Up Care for Homeless Populations in North County San Diego (Sanchez, 2021)

- On the Incentives of Medicare’s Hospital Reimbursement and an Examination of Exchangeability (Elzinga, 2016)

- Managing the healthcare crisis: the career narratives of nurses (Krueger, 2021)

- Methods for preventing central line-associated bloodstream infection in pediatric haematology-oncology patients: A systematic literature review (Balkan, 2020)

- Farms in Healthcare: Enhancing Knowledge, Sharing, and Collaboration (Garramone, 2019)

- When machine learning meets healthcare: towards knowledge incorporation in multimodal healthcare analytics (Yuan, 2020)

- Integrated behavioural healthcare: The future of rural mental health (Fox, 2019)

- Healthcare service use patterns among autistic adults: A systematic review with narrative synthesis (Gilmore, 2021)

- Mindfulness-Based Interventions: Combatting Burnout and Compassionate Fatigue among Mental Health Caregivers (Lundquist, 2022)

- Transgender and gender-diverse people’s perceptions of gender-inclusive healthcare access and associated hope for the future (Wille, 2021)

- Efficient Neural Network Synthesis and Its Application in Smart Healthcare (Hassantabar, 2022)

- The Experience of Female Veterans and Health-Seeking Behaviors (Switzer, 2022)

- Machine learning applications towards risk prediction and cost forecasting in healthcare (Singh, 2022)

- Does Variation in the Nursing Home Inspection Process Explain Disparity in Regulatory Outcomes? (Fox, 2020)

Looking at these titles, you can probably pick up that the research topics here are quite specific and narrowly-focused , compared to the generic ones presented earlier. This is an important thing to keep in mind as you develop your own research topic. That is to say, to create a top-notch research topic, you must be precise and target a specific context with specific variables of interest . In other words, you need to identify a clear, well-justified research gap.

Need more help?

If you’re still feeling a bit unsure about how to find a research topic for your healthcare dissertation or thesis, check out Topic Kickstarter service below.

You Might Also Like:

15 Comments

I need topics that will match the Msc program am running in healthcare research please

Hello Mabel,

I can help you with a good topic, kindly provide your email let’s have a good discussion on this.

Can you provide some research topics and ideas on Immunology?

Thank you to create new knowledge on research problem verse research topic

Help on problem statement on teen pregnancy

This post might be useful: https://gradcoach.com/research-problem-statement/

can you provide me with a research topic on healthcare related topics to a qqi level 5 student

Please can someone help me with research topics in public health ?

Hello I have requirement of Health related latest research issue/topics for my social media speeches. If possible pls share health issues , diagnosis, treatment.

I would like a topic thought around first-line support for Gender-Based Violence for survivors or one related to prevention of Gender-Based Violence

Please can I be helped with a master’s research topic in either chemical pathology or hematology or immunology? thanks

Can u please provide me with a research topic on occupational health and safety at the health sector

Good day kindly help provide me with Ph.D. Public health topics on Reproductive and Maternal Health, interventional studies on Health Education

may you assist me with a good easy healthcare administration study topic

May you assist me in finding a research topic on nutrition,physical activity and obesity. On the impact on children

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Qualitative Research – a practical guide for health and social care researchers and practitioners

(0 reviews)

Darshini Ayton, Monash University

Tess Tsindos, Monash University

Danielle Berkovic, Monash University

Copyright Year: 2023

Last Update: 2024

ISBN 13: 9780645755404

Publisher: Monash University

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Table of Contents

- Acknowledgement of Country

- About the authors

- Accessibility statement

- Introduction to research

- Research design

- Data collection

- Data analysis

- Writing qualitative research

- Peer review statement

- Licensing and attribution information

- Version history

Ancillary Material

About the book.

This guide is designed to support health and social care researchers and practitioners to integrate qualitative research into the evidence base of health and social care research. Qualitative research designs are diverse and each design has a different focus that will inform the approach undertaken and the results that are generated. The aim is to move beyond the “what” of qualitative research to the “how”, by (1) outlining key qualitative research designs for health and social care research – descriptive, phenomenology, action research, case study, ethnography, and grounded theory; (2) a decision tool of how to select the appropriate design based on a guiding prompting question, the research question and available resources, time and expertise; (3) an overview of mixed methods research and qualitative research in evaluation studies; (4) a practical guide to data collection and analysis; (5) providing examples of qualitative research to illustrate the scope and opportunities; and (6) tips on communicating qualitative research.

About the Contributors

Associate Professor Darshini Ayton is the Deputy Head of the Health and Social Care Unit at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. She is a transdisciplinary implementation researcher with a focus on improving health and social care for older Australians and operates at the nexus of implementation science, health and social care policies, public health and consumer engagement. She has led qualitative research studies in hospitals, aged care, not-for-profit organisations and for government and utilises a range of data collection methods. Associate Professor Ayton established and is the director of the highly successful Qualitative Research Methods for Public Health short course which has been running since 2014.

Dr Tess Tsindos is a Research Fellow with the Health and Social Care Unit at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. She is a public health researcher and lecturer with strong qualitative and mixed methods research experience conducting research studies in hospital and community health settings, not-for-profit organisations and for government. Prior to working in academia, Dr Tsindos worked in community care for government and not-for-profit organisations for more than 25 years. Dr Tsindos has a strong evaluation background having conducted numerous evaluations for a range of health and social care organisations. Based on this experience she coordinated the Bachelor of Health Science/Public Health Evaluation unit and the Master of Public Health Evaluation unit and developed the Evaluating Public Health Programs short course in 2022. Dr Tsindos is the Unit Coordinator of the Master of Public Health Qualitative Research Methods Unit which was established in 2022.

Dr Danielle Berkovic is a Research Fellow in the School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. She is a public health and consumer-led researcher with strong qualitative and mixed-methods research experience focused on improving health services and clinical guidelines for people with arthritis and other musculoskeletal conditions. She has conducted qualitative research studies in hospitals and community health settings. Dr Berkovic currently provides qualitative input into Australia’s first Living Guideline for the pharmacological management of inflammatory arthritis. Dr Berkovic is passionate about incorporating qualitative research methods into traditionally clinical and quantitative spaces and enjoys teaching clinicians and up-and-coming researchers about the benefits of qualitative research.

Contribute to this Page

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 13, Issue 3

- Application of complexity theory in health and social care research: a scoping review

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4383-8650 Áine Carroll 1 , 2 ,

- Claire Collins 3 ,

- Jane McKenzie 3 ,

- Diarmuid Stokes 4 ,

- Andrew Darley 1

- 1 School of Medicine , University College Dublin , Dublin , Ireland

- 2 Academic Department , National Rehabilitation University Hospital , Dublin , Ireland

- 3 Henley Business School , University of Reading , Reading , UK

- 4 College of Health Sciences , University College Dublin , Dublin , Ireland

- Correspondence to Áine Carroll; aine.carroll{at}ucd.ie

Background Complexity theory has been chosen by many authors as a suitable lens through which to examine health and social care. Despite its potential value, many empirical investigations apply the theory in a tokenistic manner without engaging with its underlying concepts and underpinnings.

Objectives The aim of this scoping review is to synthesise the literature on empirical studies that have centred on the application of complexity theory to understand health and social care provision.

Methods This scoping review considered primary research using complexity theory-informed approaches, published in English between 2012 and 2021. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, Web of Science, PSYCHINFO, the NHS Economic Evaluation Database, and the Health Economic Evaluations Database were searched. In addition, a manual search of the reference lists of relevant articles was conducted. Data extraction was conducted using Covidence software and a data extraction form was created to produce a descriptive summary of the results, addressing the objectives and research question. The review used the revised Arksey and O’Malley framework and adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR).

Results 2021 studies were initially identified with a total of 61 articles included for extraction. Complexity theory in health and social care research is poorly defined and described and was most commonly applied as a theoretical and analytical framework. The full breadth of the health and social care continuum was not represented in the identified articles, with the majority being healthcare focused.

Discussion Complexity theory is being increasingly embraced in health and care research. The heterogeneity of the literature regarding the application of complexity theory made synthesis challenging. However, this scoping review has synthesised the most recent evidence and contributes to translational systems research by providing guidance for future studies.

Conclusion The study of complex health and care systems necessitates methods of interpreting dynamic prcesses which requires qualitative and longitudinal studies with abductive reasoning. The authors provide guidance on conducting complexity-informed primary research that seeks to promote rigor and transparency in the area.

Registration The scoping review protocol was registered at Open Science Framework, and the review protocol was published at BMJ Open ( https://bit.ly/3Ex1Inu ).

- QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

- International health services

- Quality in health care

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-069180

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study builds on previous evidence syntheses and synthesises the literature on empirical studies that have centred on the application of complexity theory to understand health and social care provision.

This review applies the latest guidance for the performance of scoping reviews.

The review covers the years 2012–2021 and includes English language papers only.

The review excluded educational settings.

Health and care systems around the globe are struggling to cope with the imbalance between increasing demands and system constraints. These challenges have been amplified with the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic. Traditional approaches to tackling these challenges have typically taken a positivistic approach using mechanistic linear reductionist methods more suited to physical systems than complex adaptive human systems and have failed to produce the necessary system transformation. These positivist views have been challenged as simplistic by various key complexity philosophers and scientists over the years. 1–5 Complexity theory and science have received increasing academic and health system attention in recent years as appreciation has grown that, to address increasingly complex and systemic issues, there is a need for collaborative, cross-sectoral, multidisciplinary working. However, how best to study complex social systems is unclear. What is acknowledged is that complex systems share certain characteristics; they consist of elements that interact dynamically in a non-linear manner with feedback loops in systems that are open and operate in conditions far from equilibrium. Each complex system has a history, which influences the behaviour of the system which is determined by the nature of the interactions between the elements. These interactions are adaptive and dynamic with unpredictable outcomes. 1 2 6 Preiser and colleagues in 2018 completed an evidence synthesis of prominent authors’ classifications of complex adaptive systems (CAS) features and characteristics and proposed a typology of six organising principles to inform practical implications and methods for studying and understanding complex systems. 6 These are the following: (1) it is constituted relationally; (2) it has adaptive capacities; (3) patterns of behaviour are a consequence of dynamic processes; (4) it is radically open; (5) it is determined contextually and (6) novel qualities emerge through complex causality. While there is an absence of a unifying theory of complexity, it is generally accepted that engaging with complex systems requires an entanglement of theories and methods.

While the increasing adoption of complexity-informed methods to empirically investigate health and social care settings is welcome, the literature to date has been critiqued for engaging with complexity in name only and lacking the required appreciation and engagement with the logic that underpins it. A scoping review performed by Thompson and colleagues in 2016 investigated complexity theory in health services research and found that, although complexity theory in healthcare was potentially useful, conceptual vagueness and variable theoretical application impeded its practical application. 7 In 2017, Rusoja and colleagues performed a systematic literature review examining health-related systems thinking and complexity ideas. 8 Similar to Thompson and colleagues, they also found that the literature was largely theoretical, suggesting the need for additional research involving practical application. These reviews are now somewhat outdated given the dynamic ever-changing flux of healthcare in the time that has passed since the reviews were published. In addition, these reviews focused on healthcare provision while omitting social care which is an integral component of the continuum of integrated care. Furthermore, the authors did not seek to characterise the components of complexity which were being used nor the theoretical underpinning of the research reviewed. Theory is important to research in that good theory informs the performance of high-quality research (qualitative or quantitative) about important issues that advance knowledge in the phenomenon of interest 9 and the Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance on the development and evaluation of complex interventions recommended that interventions should be developed systematically ‘using the best available evidence and appropriate theory’ 10 (p2). They also suggest that qualitative and mixed-methods approaches may be required to answer questions beyond effectiveness. When theory is used inappropriately, the benefit of using theory to inform high-quality research is negatively impacted. If used correctly, complexity theory offers a potentially useful perspective for the conceptualisation and resolution of problems in healthcare. Therefore, we identified a gap in the evidence regarding how complexity theory has been applied in health and social care research which warranted further examination and synthesis of the evidence to date. Evidence to date suggests limited description, features and attributes which may suggest a lack of appreciation of the underlying principles of a complex system when studying phenomena, which will be explored in this review.

The aim of this review is to map and describe the available research which has used complexity theory in health and social care settings. The authors seek to additionally expand on the previous evidence by providing a comprehensive understanding of the literature to date and offer guidance on how to apply complexity theory to research in health and social care in the future.

Ethical approval was not required, and this manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study and no important aspects of the study have been omitted.

Guided by Munn and colleagues, 11 the authors determined that a scoping review was the most appropriate approach to systematically explore how complexity theory has been applied in health and social care research. The scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) statement. 12 The initial exploratory search of the literature highlighted significant gaps in current knowledge regarding how and why complexity theory has been applied in health and social care settings. In accordance with best practice for scoping reviews, an a priori protocol was developed and published. 13 The framework for scoping reviews developed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and refinements made by subsequent authors 11 14–16 guided the methodology for the current review. This framework consists of six stages: specifying the research question; identifying relevant studies; study selection; charting the data and reporting the results; collating, summarising and reporting the findings; and consultation exercise.

Stage 1: specifying the research question

Following an initial search of the literature (MEDLINE, CINAHL) and consultation with authors of previously published systematic reviews in the area, 7 8 17 18 the scoping review research question was developed: ‘How has complexity theory been applied in health and social care research?’. The scoping review had the following objectives:

To map definitions and descriptions of complexity theory used in research regarding health and social care.

To describe the purpose of studies using the lens of complexity theory and phenomena of interest.

To investigate the methodologies used and the extent to which complexity theory has been employed in health and social care research.

To consider the settings and professions examined in these studies.

To assess the implications and outcomes of the application of complexity theory in health and social care research.

To identify gaps in the evidence base and make recommendations for future research.

To determine guidance for future researchers when applying complexity theory in research regarding health and social care.

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

Relevant studies were identified according to the inclusion criteria and the Population, Concept and Context (PCC). 16

Population: Health and social care professionals.

Concept: Application of complexity theory in empirical research in health and/or social care.

Context: Health and social care settings.

Building on the evidence produced in the previous evidence syntheses, this scoping review considered qualitative and quantitative primary research using complexity theory–informed approaches, published in the English language between the years 2012 and 2021.

The following types of publications were excluded from the review: retrospective reviews, secondary analysis research, conference abstracts, book reviews, commentaries or editorial articles, opinion papers, letters and non-English articles.

Acknowledging that the review focused on the application of complexity theory regarding the provision of health and social care rather than the experience of receiving care, publications containing patient-only samples were excluded from the screening process.

An initial exploratory search strategy was developed in MEDLINE by three of the authors, including a university librarian experienced in the conduct of systematic reviews, using Medical Subjects Headings and text words ( online supplemental file 1 ). The search was adapted for each subsequent database and any additional key terms were added to all other database search strategies before conducting the searches within all included databases: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, Web of Science, PSYCHINFO, The NHS Economic Evaluation Database and The Health Economic Evaluations Database. In addition, a manual search of the reference lists of relevant articles was conducted. No quality appraisal was performed as the authors sought to describe, not evaluate, the available evidence on the topic.

Supplemental material

Stage 3: source of evidence selection.

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the authors independently screened titles, abstracts and full-text papers using the systematic review software tool, Covidence. 19 Each stage involved two reviewers who were independent and blinded to the fellow reviewer decision outcomes to reduce potential bias. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion and a third reviewer was not required. To ensure consistent application of the screening criteria, a pilot test of the screening process was undertaken by the two reviewers using a small, random sample (n=25) of the identified articles based on their titles and abstracts. Relevant articles were retrieved from each database separately and imported into the bibliographic manager, and EndNote and the Bramer method were used for deduplication. 20

Stage 4: data extraction

Data extraction was conducted using the Covidence software. The data extraction form ( Table 1 ) was tested on a small sample of studies (n=10) by two reviewers to ensure consistency and was modified to include further criteria to answer the research question and objections. The results of the data extraction were compared and discussed. No discrepancies occurred during this stage and did not require a third reviewer.

- View inline

Data extraction form for included studies

Stage 5: Collating, summarising and reporting the results

Using the information contained in the data extraction form, this step involved a descriptive and numerical summary of the information within the identified publications as they related to the objectives of the review. Full-text publications were referred to if further information was needed from a particular study. The terminology used to describe complex systems was extracted and synthesised using the features and attributes in the Preiser framework. 6 Research purpose(s) were extracted verbatim based on the verbs used in the purpose statement as described in the abstract and/or main body and the authors documented where more than one research purpose was mentioned. The implications were analysed regarding their relevance to practice, policy and research, whereas outcomes pertained to direct impact on the phenomena or tools developed as a result of the research which applied complexity theory.

Stage 6: Patient and public involvement

The hospital patient forum, a platform for dialogue and exchange of information relevant to patients regarding the hospital, participated in the design and interpretation of the results of the scoping review.

A total of 2021 articles were identified. Of these, 676 were duplicates. The titles and abstracts of 1345 articles were screened and 1108 did not meet the inclusion criteria and were therefore excluded. The remaining 237 articles were full-text screened. Full-text screening of the final 237 resulted in the final inclusion of 61 articles. There were 9 systematic reviews identified which were subsequently hand-searched for further relevant articles. The PRISMA flow chart is shown below in Figure 1 .

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow chart.

Descriptive summary

The key characteristics of the included studies are described in online supplemental file 2 .

Year of publication

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the year of publication of the papers considered.

Year of publication.

The most publications were in 2018, 2019 and 2020 (eight publications). The fewest were in 2015 (2) followed by 2021 (3). The trendline is quite flat.

Journal of publication

As shown in Figure 3 , there were 43 different journals in which papers were published across a broad range of journal types. The most common journals for publication were Social Science and Medicine (n=7) and BMC Health Service Research (n=4). All other journals published between 1 and 2 papers.

Journal of publication.

Geographical location of study

Of the 61 publications, 17 studies were set in the USA and 11 in Canada and 8 in the UK. The complete geographical locations for the studies are shown in Figure 4 .

Geographical location of study.

Ethical considerations

Complexity studies present distinct ethical challenges for researchers, as unpredictability means research will be performed and decisions taken based on an imperfect understanding. Therefore, researchers need to be open and honest about the uncertainty and reflect critically on the decision-making processes. 21 In our scoping review, studies only reported standard research ethics committee approval procedures.

Objective 1: definitions and descriptions of complexity theory

36 papers (59%) provided a definition of complexity theory. In 23 (38%), no definition or description was given. 2 papers provided descriptions of complexity and 3 provided a definition of CAS. There was great variability in the definitions used.

Characteristics and features

Many different terms were used to describe complex systems. 10 papers used the term characteristics, 9 used concepts, 8 used the term principles and 20 papers were unclear. No papers cited Preiser’s typology. 6 The terms were mapped against the Preiser framework ( Table 2 ) with synonyms grouped against the most aligned principle.

Terms mapped against the features and attributes in the Preiser framework

The most reported terms were self-organisation (n=23), non-linearity (n=22) and emergence (n=18). The least reported features were radically open (n=3) and contextually determined (n=5).

Objective 2: research purpose and phenomenon of interest

Guided by Thompson and colleagues’ synthesis, the articles were analysed for their purpose and the phenomenon investigated. The majority of studies mentioned two or more research purposes (47.5%) across a variety of health and social care phenomena. These research purposes included assess, build, determine, develop, discuss, draw, elucidate, gain, generate, increase, inform, outline, present and unravel. The most common research phenomena with multiple purposes were working environment/context, implementation and change. Following studies with two or more research purposes, the most common research purposes sought to explore (9.8%) and describe (9.8%) the phenomenon. Research purposes aimed at exploring a wide variety of phenomena featured investigations of the role of physician assistants within a CAS, 22 the impact of workplace huddles in clinical practice, 23 the adoption of leadership at a microlevel through the influential acts of organising, 24 responses to intimate partner violence 25 and the naming or classification of physical assaults within relationship in the context of emergency departments. 26

Studies that sought to describe phenomena related to working environment/context included the processes and development of a dementia network, 27 decision-making processes within an intensive care setting [30] and the context of telenursing as a CAS [20]. Other studies sought to describe the clinical implications of non-linear dynamics within intimate partner violence, 28 physician leadership within healthcare organisations 29 and regional sustainability in healthcare improvement. 30

Thus, studies with two or more research purposes represent the most common application of complexity theory in health and social care research. Our analysis shows that the most common phenomena studied were implementation and working environment/context within health and social care respectively with 16 studies each within the identified articles.

Objective 3: research methodologies and application of complexity theory

28 studies (46%) had a qualitative research design. 17 studies (28%) were case studies and 9 studies (15%) used mixed methods. The most common application of complexity theory (52.5%) was as a theoretical framework to understand a phenomenon and conduct data analysis. A further 10 studies used complexity theory exclusively for the purpose of data analysis, whereas 8 studies primarily applied the theory as a theoretical framework. Where complexity theory was used as a theoretical underpinning, it was used to describe the setting or context they were studying as a CAS, to focus on a particular characteristic of complexity or to formulate research questions.

Complexity theory was frequently adopted in qualitative methods of inquiry. Qualitative methods or mixed-method studies (included a qualitative component) were based on case studies or studies which used grounded theory as an analytical method, content analysis and thematic analysis. These studies focused on particular characteristics of complexity theory to interpret their findings or as the foundation of a coding framework. However, some authors defined the exact characteristics of complexity that they were focusing on in their analysis, 29 31–41 whereas other studies broadly described conducting analysis with the lens of complexity theory 26 42–44 or not clearly stated. 45–47

A number of studies featured interventions or programmes that were founded on or informed by complexity theory. 48–50 Two studies featured an assessment framework or tool. 51 52 Tang and colleagues 53 applied complexity as a theoretical framework and data analysis, as well as to develop a model of policy implementation. In a similar fashion, Sawyer and colleagues 49 applied complexity in the development of a logic framework in the context of obesity prevention. One study used complexity theory to develop a conceptual model to help in the design and conduct of community-based health promotion evaluation. 54

Objective 4: settings, disciplines and professions

Of the 61 publications, 10 studies were hospital-based, 10 were based in a health system and 9 in a primary care setting. 2 studies were based in a rehabilitation setting.

A variety of disciplines and professions were reflected in the literature reviewed. We used the term multidisciplinary team (MDT) to describe a range of health service workers, both professionals and non-professionals described in the studies when more than two types of professionals were stated. Where patients were specifically mentioned as part of the MDT, we included that as a separate category, and also where non-traditional MDT members were specifically mentioned.

Of the 61 studies, 22 (34%) involved MDTs. Six (9%) involved nurses and 4 (6%) MDTs including patients. In 2 papers, there were no participants as the study involved documentary analysis and in 2, the participants were not specified.

Objective 5: Implications and outcomes of applying complexity theory

The most frequent implication was exclusively practice-related (44%). A full breakdown of imications and utcomes is provided in online supplemental file 2 . A significant proportion of studies had multiple implications. 21% of the studies contained implications for both practice and research, while 11.5% had implications in all three dimensions. Implications encompassed changes in clinical practice delivery such as huddles, 23 recommendations for motivational interviewing 45 and social work practice guidelines for dealing with families with complex needs. 55 From a policy perspective, recommendations included complexity-informed processes for the implementation of local drugs policy 35 and complexity-compatible policies regarding integrated healthcare. 37 Implications for future research were typically in relation to the phenomenon being investigated and reflection on their own methodological limitations, for example, Gear and colleagues 25 note the need for more diversity in the samples regarding intimate partner violence in a primary care setting while another study promoted the use of social network analysis and ethnographic approaches to explore the shifts in interactions following the implementation of a simulation tool within a healthcare CAS. 34 One study was unclear in their implications, while one study did not explicitly state any implications in the discussion of their findings.

Some studies contained pragmatic outcomes as a result of applying complexity theory. Reed and colleagues 43 developed 12 ‘Simple Rules’ intended to provide actionable guidance to support evidence translation and improvement in complex systems. Hodiamont et al 39 created a conceptual framework that can be used as a basis for the development of a classification of complexity in palliative care, with an understanding of the variance in patients according to their care needs. One study developed seven action recommendations to promote community resilience and population health. 56 Albers Mohrman et al 30 provided organising principles to facilitate change within a CAS, while Sawyer et al 49 developed a logic framework intended to inform sustainable systems change from a whole-systems approach. To identify the extent to which the identified publications were used in subsequent research, we assessed the number of citations of the 61 papers included in our review. As of 1 October 2022, the most cited papers were O’Sullivan et al (41) (219), Ssengooba et al (68) (171) and Tsasis et al (34) (151). Review objectives 6 and 7 will be addressed in the Discussion section.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first scoping review to synthesise the literature on the application of complexity theory in health and social care research. Although earlier reviews examining complexity in healthcare literature are available, 7 8 the current review has identified that in the time since their publication, subsequent research has remained largely theoretical, with little progress in terms of the practical application of complexity theory. In addition, although research has occurred within what is described as health systems, none of the final papers had a social care context. Adult social care refers to services that provide support to people with physical disabilities, learning disabilities or physical and mental illnesses. Over a third of publications failed to provide a clear definition of complexity or provide the theoretical context for the research. What was meant by a complex system was ambiguous, heterogeneous and often ill-defined. The limited description, features and attributes used in many papers suggest a lack of appreciation for the principles of a complex system which the current authors believe is a basic requirement before appropriate methods and approaches can be selected for studying phenomena in a complex system. However, we acknowledge that as there is no unifying theory or agreed-upon definition of complexity, 57 58 it is unclear how many features and attributes of a complex system need to be considered when contemplating appropriate approaches, which may explain the lack of detail in the identified studies. Many studies referred to primary studies or discussion papers in the definition or description of complexity theory without citing the founding key theorists. This may be due to the complexities within the theory itself and later authors in the area present accessible literature to help researchers understand its underlying logic. Nonetheless, we would argue that an explicit explanation regarding the researchers’ understanding of and approach to complexity is vital to orientate the reader and highlight whether meaningful engagement with the phenomenon of interest has occurred.

Regarding methodologies employed, our findings indicate that since the Thompson and Rusoja reviews, empirical research has remained primarily qualitative and case study orientated, with most publications in the USA and Canada. Most studies applied complexity as both a theoretical framework and for data analysis. Several studies used complexity theory within qualitative research to analyse and code their data. The review also identified several case studies in which authors sought to understand a setting or service using a complexity-informed lens. This may be because the case study approach seeks to capture the richness of a phenomenon rather than simple cause and effect. To perform research into complex systems in which power law distributions are in operation, there is a need to interpret the processes of dynamicity and that requires qualitative and longitudinal studies. 59 There is also value in an abductive logic of inquiry, which allows for the weaving and entanglement of previous evidence into the greater understanding of the whole complex adaptive system. 60

Health and social care systems deal with many interconnected and entangled issues that require researchers in the field to take a participatory, inclusive, integrated and multidisciplinary approach to research and that requires theoretical and methodological pluralism. Researchers should embrace a rich tapestry of approaches to develop a deep understanding of the complex health and care systems in which we work and go forth with epistemic humility. In the application of complexity theory, there is great variance regarding the detail of how it is used. Some authors explicitly state the characteristics they focus on during data analysis, whereas other studies broadly stated they used the lens of complexity, and some did not clearly state what characteristics they used.

Complexity in health and social care empirical research remains predominantly hospital or health system focused and does not encompass the full continuum of care at this point. However, it does tend to be applied in contexts where multidisciplinary teams are involved, which has implications for managing the complexity of the context.

As nearly half of the studies contained implications for practice, it can be inferred that complexity theory has been empirically applied with the intention of improving health or social care practice. Limited evidence was found within the studies regarding how the knowledge from empirical findings was used to inform or improve the setting or phenomena being studied. However, a number of studies produced pragmatic tools or guides that were informed by complexity theory and for future engagement using a complexity lens. The heterogeneity of empirical studies is perhaps not unsurprising as it is still early days in the application of complexity theory to health and social care. Given Ashby’s law of requisite variety as operationalised in the Ashby space as described by Boisot and McKelvey, 59 this makes it hard to initially establish any consistency in the domain. We therefore propose guidance that could provide more comparability in evidence-based studies going forward.

Guidance for reporting complexity in health and social care research

As there is currently no definitive procedure for reporting such studies, we propose the following items for inclusion. These are not intended to be a rigid checklist but rather flexible guidance to be interpreted and adapted to support the reporting of theoretically and methodologically divergent research.

Provide a clear definition of complexity with an explanation of the theoretical underpinnings of your research so the reader can understand your ontological and epistemological stance. 61 62

Explain why complexity theory is relevant to the phenomenon being studied.

Identify the principles and characteristics of complexity theory that were explored.

Explicitly state how complexity is applied regarding the various stages of the research process, that is, theoretical underpinning, data collection and data analysis.

Describe the outcome or impact of the study in terms of direct change in health and social care setting, practice, policy or research.

Discuss ethical components of applying complexity theory and reflexivity to the specific phenomenon.

Include a statement on what the research is to inform or improve from the outset.

Limitations

The authors adapted their inclusion criteria to include articles from the past 10 years (2012–2021) due to project and time resources. Inclusion of previous years may have facilitated a fuller historical understanding. Health and social care educational settings were excluded and probably merit its own review in the future. Additionally, the search string and screening criteria focused on health and social care professionals and managers as the population in the study. Further evidence synthesis could be conducted in the future regarding patients and how complexity theory has been used to understand their experience. Additionally, future evidence synthesis could include publications that feature studies that include secondary analysis, as it was not the scope of the current study but may yield further insights into the application of complexity theory.

Complexity theory has been increasingly adopted to conduct research in the areas of health and social care. Despite ample application in the context, huge divergence exists in the evidence base regarding how it can be applied and what constitutes its application. For the field to progress and establish transparency in empirical findings, the output of this current review are principles that should be considered and applied, where necessary, in the conduct of research methodologies which involve the various versions of complexity theory. This scoping review builds on the growing field of ‘translational systems research’ 63 that seeks to translate the theoretical concepts of CAS science into practical applications. Although the guidance offered in the current review is based on the synthesis of studies in health and social care, the principles may be applied to other fields, such as business, technology or educational phenomenon. The principles resulting from this scoping review are intended to support the rigorous application of complexity theory in empirical research and contribute to future transparent evidence going forward. The authors believe that the findings and guidance detailed in this review will be of benefit to health and social care professionals, managers and researchers in their commitment to developing services for the people they intend to care for.

- Boulton JG ,

- Lichtenstein BM

- Prigogine I

- Preiser R ,

- De Vos A , et al

- Thompson DS ,

- Kustra E , et al

- Sievers J , et al

- Van de Ven AH

- Macintyre S , et al

- Peters MDJ ,

- Stern C , et al

- Tricco AC ,

- Zarin W , et al

- Carroll A ,

- Colquhoun H ,

- Godfrey C ,

- McInerney P , et al

- Tricco AC , et al

- Brainard J ,

- Churruca K ,

- Ellis LA , et al

- Kellermeyer L ,

- Bramer WM ,

- Giustini D ,

- de Jonge GB , et al

- Woermann M ,

- Burrows KE ,

- Abelson J ,

- Miller PA , et al

- Provost SM ,

- Lanham HJ ,

- Leykum LK , et al

- Ker J , et al

- Koziol-Mclain J

- Boustani MA ,

- Munger S , et al

- Ferrer RL , et al

- Albers Mohrman S ,

- (Rami) Shani AB

- Caffrey L ,

- Mertens F ,

- Helewaut F , et al

- Leykum LK ,

- McPherson E , et al

- Escrig-Pinol A ,

- Corazzini KN ,

- Blodgett MB , et al

- Grudniewicz A ,

- Tenbensel T ,

- Evans JM , et al

- Livingstone C

- Hodiamont F ,

- Leidl R , et al

- Trenholm S ,

- Fitzgerald K ,

- Price D , et al

- Doyle C , et al

- van Roode T ,

- Marcellus L

- Lawn S , et al

- Lévesque MC ,

- Jacquemin G , et al

- Sanford S ,

- Sider D , et al

- Colón-Emeric CS ,

- Corazzini K ,

- McConnell ES , et al

- den Hertog K ,

- Verhoeff AP , et al

- Kottke TE ,

- Huebsch JA ,

- Mcginnis P , et al

- Ferreira DMC ,

- Andersson Gäre B ,

- Greenhalgh T , et al

- O’Sullivan TL ,

- Kuziemsky CE ,

- Toal-Sullivan D , et al

- de Vos A , et al

- Shani AB (Rami ),

- Coghlan D ,

- Alexander BN

- O’Cathain A ,

- Duncan E , et al

- Rousseau N , et al

- Buckle Henning P ,

- Ciemins EL ,

- Kersten D , et al

- Björkman A ,

- Salzmann-Erikson M

- Stevenson J

- McDonald J , et al

- Amo-Adjei J ,

- Doku D , et al

- Augustinsson S ,

- Petersson P

- Barasa EW ,

- Molyneux S ,

- English M , et al

- Lindberg C ,

- Schneider M

- Bishai DM , et al

- McKechnie AC ,

- Johnson KA ,

- Baker MJ , et al

- de Bock BA ,

- Willems DL ,

- Weinstein HC

- Langer A , et al

- Ghazzawi A ,

- Kuziemsky C ,

- O’Sullivan T

- González MG ,

- Dozier AM , et al

- Filipovic J

- Ssengooba F ,

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data.

This web only file has been produced by the BMJ Publishing Group from an electronic file supplied by the author(s) and has not been edited for content.

- Data supplement 1

- Data supplement 2

Twitter @AinemCarroll, @adarleyresearch

Contributors AC was responsible for study conceptualisation, study design, data collection, data analysis/synthesis and writing manuscript. AD was responsible for study design, data collection, data analysis/synthesis and writing manuscript. DS was responsible for study design and data collection. CC and JM were responsible for study conceptualisation and reviewing manuscript. AC is responsible for the overall content as guarantor. The guarantor accepts full responsibility for the finished work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Map disclaimer The inclusion of any map (including the depiction of any boundaries therein), or of any geographic or locational reference, does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. Any such expression remains solely that of the relevant source and is not endorsed by BMJ. Maps are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient and public involvement Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Request new password

- Create a new account

Making Sense of Research in Nursing, Health and Social Care

Student resources, 6. approaches to and design of research in health and social care.

Reflective Exercise

Looking at the papers below, consider

- What is the research approach or design used?

- Does the design enable the researchers to answer the research hypothesis/aims/questions?

SUGGESTED SAGE ONLINE JOURNALS FOR USE

Qualitative design

Bartlett, R. (2012). Modifying the diary interview method to research the lives of people with dementia. Qualitative Health Research , 22 (12), 1717–26. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1049732312462240

Quantitative design

Bainbridge, D. and Seow, H. (2017). Palliative care experience in the last 3 months of life: a quantitative comparison of care provided in residential, hospice, hospitals and the home form the perspectives of bereaved care givers. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine , 1–8. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1049909117713497

ADDITIONAL MATERIALS

Further suggested resources to look at.

Journal of Mixed Methods Research : http://journals.sagepub.com/home/mmr

- Member Organisations

- Research, Implementation and Impact

- Social Care and Social Work

- Social Care - Kent, Surrey & Sussex Region

- Starting Well: Children's Mental Health

- Primary and Community Health Services

- Living Well with Dementia

- Co-production

- Public Health

- Digital Innovation

- Economics of Health and Social Care

- Implementation

- Public and Community Involvement

- What is PCIE?

- Getting Involved

- Support for researchers

- Introduction

- An overview of ARC KSS

- Who can help you with PCIE?

- Terminology and PCIE

- Why and When to do PCIE

- Why involve members of the public in research?

- Why do members of the public want to get involved in research?

- When to get members of the public involved?

- How to do PCIE

- Communication and Accessibility

- Planning for involvement and engagement

- How to recruit members of the public

- Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI)

- Approaches – different options for undertaking PCIE

- Facilitating meetings and Group dynamics

- Impact and Evaluation

- Examples/Case Studies

- Appendix/Useful tools

- Learning and Development

- Learning and Development Finder

- Researchers Journeys

- Research Week

- Previous Research Weeks

- Resource Library

Your Health and Social Care Research Quick Guide

This guide is designed for those in practice to navigate the world of research.

In this section

Produced by Dr Diana Ramsey , ARC KSS Darzi Fellow (2021-2022) with insights and support from people working to deliver research in the Health and Social Care region, the Your Health and Social Care Research Quick Guide is a resource to help those working in health or social care to start or develop their research journey.

Packed with information, links and personal stories from people working across Kent, Surrey and Sussex, this guide has been designed to answer any questions you might have in regards to getting involved in research, building networks, research training and resources.

Whatever your research experience, this guide is for you.

View guide here

Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up here

You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking the link in the footer of our emails. For information about our privacy practices, please visit this page . We use e-shot as our marketing platform. Learn more about e-shot's privacy practices here .

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- 10 Research Question Examples to Guide Your Research Project

10 Research Question Examples to Guide your Research Project

Published on October 30, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on October 19, 2023.

The research question is one of the most important parts of your research paper , thesis or dissertation . It’s important to spend some time assessing and refining your question before you get started.

The exact form of your question will depend on a few things, such as the length of your project, the type of research you’re conducting, the topic , and the research problem . However, all research questions should be focused, specific, and relevant to a timely social or scholarly issue.

Once you’ve read our guide on how to write a research question , you can use these examples to craft your own.

Note that the design of your research question can depend on what method you are pursuing. Here are a few options for qualitative, quantitative, and statistical research questions.

Other interesting articles

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, October 19). 10 Research Question Examples to Guide your Research Project. Scribbr. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-question-examples/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to choose a dissertation topic | 8 steps to follow, evaluating sources | methods & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Frontiers in Psychiatry

- Public Mental Health

- Research Topics

Burnout in the Health, Social Care and Beyond: Integrating Individuals and Systems

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

Occupational burnout is a complex combination of emotional, cognitive, and behavioural factors that represents a mismatch between personal and professional responsibilities that results from a prolonged exposure to occupational stressors. Burnout contributes to poor mental wellbeing, which can lead ...

Keywords : Burnout, Healthcare, Societal Cost, Organizational Burnout

Important Note : All contributions to this Research Topic must be within the scope of the section and journal to which they are submitted, as defined in their mission statements. Frontiers reserves the right to guide an out-of-scope manuscript to a more suitable section or journal at any stage of peer review.

Topic Editors

Topic coordinators, recent articles, submission deadlines.

Submission closed.

Participating Journals

Total views.

- Demographics

No records found

total views article views downloads topic views

Top countries

Top referring sites, about frontiers research topics.

With their unique mixes of varied contributions from Original Research to Review Articles, Research Topics unify the most influential researchers, the latest key findings and historical advances in a hot research area! Find out more on how to host your own Frontiers Research Topic or contribute to one as an author.

Internet Explorer is no longer supported by Microsoft. To browse the NIHR site please use a modern, secure browser like Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, or Microsoft Edge.

Suggest a research topic

This video is not supported by your browser.

Video transcript

Providing the most effective health and social care is a huge challenge. There are so many products and procedures in use, with more being developed all the time, but often there is little good evidence about what works and what doesn’t.

We commission and fund projects looking at the usefulness of new and existing tests, treatments and devices and at new and existing ways of doing things. We also look at how to improve public health to see what really works in practice.

To make good decisions about what research to fund we need a complete and balanced picture about which questions most urgently need answering. We ask patients, carers, clinicians, health care workers, service managers and researchers. Whoever you are, we need your voice too. Use the form below, with help from the examples, to make your research suggestions.

Your idea will be seen by our research funding programmes and, if suitable, taken to one of our decision-making committees that prioritises research for funding .

We receive a large number of valuable research suggestions each year. Not all of these can be funded. However, our research funding programmes work closely with patients, members of the public, users of social care services and carers as well as health and social care experts, to ensure our research will answer the most pressing questions. To find out if your question has reached a committee please contact [email protected]

Example: Birthplace

What should we test .

Where’s the best or safest place to have a baby?

Who is it for?

Pregnant women.

Help us understand what difference the evidence could make to patients and the public, the NHS or social care.

Although women are offered a choice where to have their baby; in hospital, in a birthing centre or at home, it doesn’t seem clear which is the best or safest. It is important to find this out because it would help women and healthcare professionals make an informed choice. It could also help to reduce the costs.

Example: Peanut allergy

What should we test.

Does oral immunotherapy help children with peanut allergy?

Children with peanut allergy.

Peanut allergy is very common in the UK and can be life threatening. Patients live in fear of accidentally eating peanuts, are restricted on their food choices and must carry epipens at all times. Due to lack of treatment, the only option is to avoid peanuts and many have accidental reactions. A treatment would be life changing for these patients.

Example: Street lighting, accidents and crime

Does reduced street lighting lead to more accidents and crime?

The general public.

Local Authorities are reducing levels of street lighting by using dimmer lights or turning lights off at a set time, often midnight. Some members of the public & media think that this could lead to increases in crime or road casualties. Research is needed to see if this is actually happening and to find out if there are other effects on public health and wellbeing.

Example: Chondroitin supplements

Does Chondroitin work for osteoarthritis in the hand?

Patients who have painful osteoarthritis in their hands.

A friend of mine takes chondroitin for osteoarthritis in her hands and says it helps with the pain and swelling. I have asked my doctor if I can get it on prescription, but she said that it isn’t a prescription drug. I have looked it up on the internet and there are some sites that says it works for some people. It is easy to get hold of online as a remedy for arthritis. Arthritis is a painful disease which affects a lot of people, and if it’s in your hands it really affects what you are able to do. I think we should test chondroitin properly to see if it helps in hand osteoarthritis and if it does, it should be made available on prescription.

The NIHR funds a wide range of research – see if the area you are interested in has been funded

A question which can be researched needs to be specific – tell us what existing product or procedure needs to be evaluated.

Is there a particular group for this test? Eg: Pregnant women, children with allergies, older men, the general public?

Is it about quality of life and/or length of life? Will it save time and/or money?

Providing contact information is optional, but enables our staff to clarify details of your research suggestion, should they need to.

If you selected 'Other' in the box above, please can you tell us a little more

Use of your personal information

By completing this form you are agreeing to your details being added to our databases.

Your personal information is held and used in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation 2016 (GDPR) and the Data Protection Act (2018). The Department of Health and Social Care, NIHR is the Data Controller under GDPR. Under GDPR, we have a legal duty to protect any information we collect from you.