Sapir–Whorf hypothesis (Linguistic Relativity Hypothesis)

Mia Belle Frothingham

Author, Researcher, Science Communicator

BA with minors in Psychology and Biology, MRes University of Edinburgh

Mia Belle Frothingham is a Harvard University graduate with a Bachelor of Arts in Sciences with minors in biology and psychology

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

There are about seven thousand languages heard around the world – they all have different sounds, vocabularies, and structures. As you know, language plays a significant role in our lives.

But one intriguing question is – can it actually affect how we think?

It is widely thought that reality and how one perceives the world is expressed in spoken words and are precisely the same as reality.

That is, perception and expression are understood to be synonymous, and it is assumed that speech is based on thoughts. This idea believes that what one says depends on how the world is encoded and decoded in the mind.

However, many believe the opposite.

In that, what one perceives is dependent on the spoken word. Basically, that thought depends on language, not the other way around.

What Is The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis?

Twentieth-century linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf are known for this very principle and its popularization. Their joint theory, known as the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis or, more commonly, the Theory of Linguistic Relativity, holds great significance in all scopes of communication theories.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis states that the grammatical and verbal structure of a person’s language influences how they perceive the world. It emphasizes that language either determines or influences one’s thoughts.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis states that people experience the world based on the structure of their language, and that linguistic categories shape and limit cognitive processes. It proposes that differences in language affect thought, perception, and behavior, so speakers of different languages think and act differently.

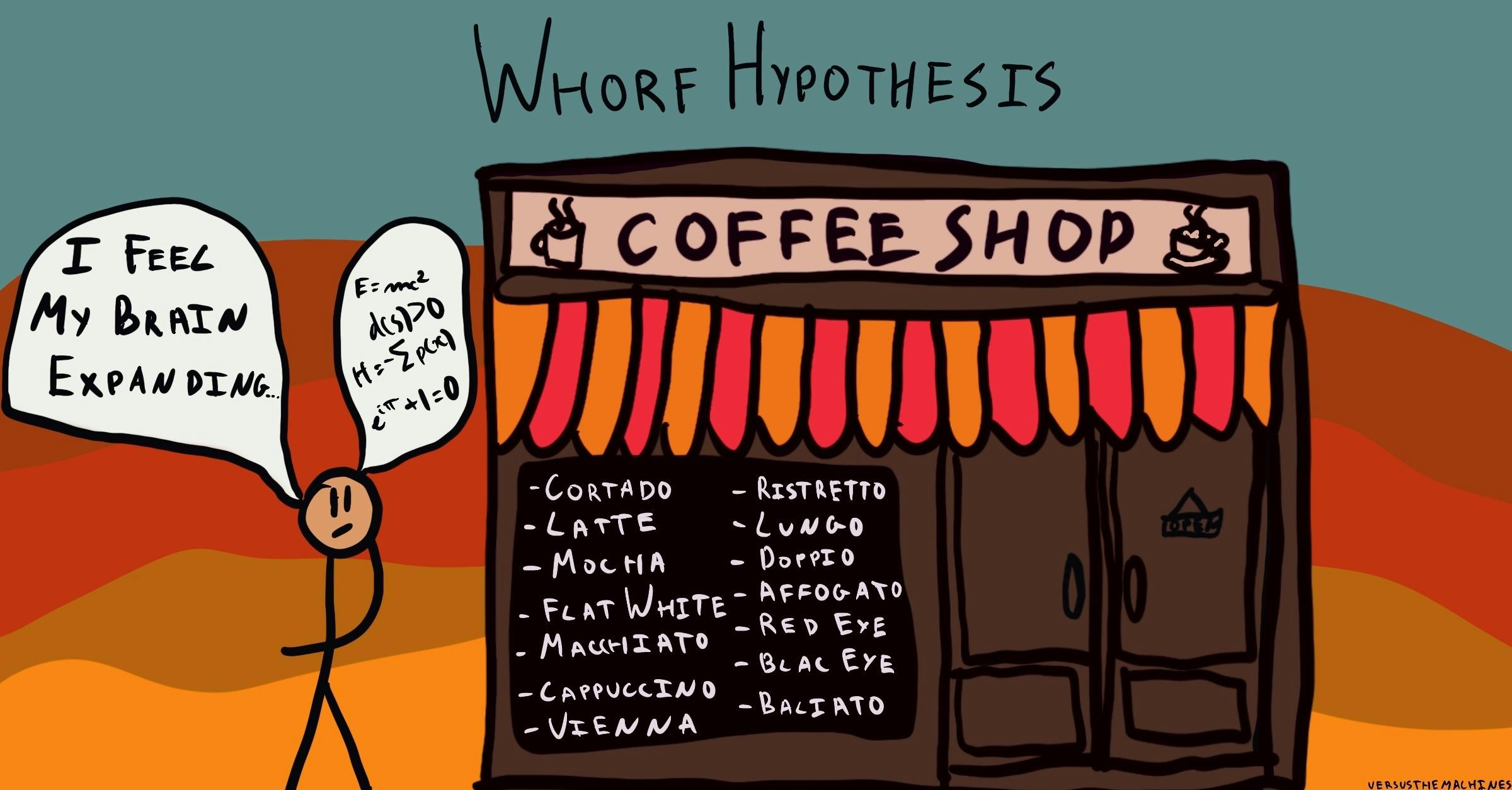

For example, different words mean various things in other languages. Not every word in all languages has an exact one-to-one translation in a foreign language.

Because of these small but crucial differences, using the wrong word within a particular language can have significant consequences.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is sometimes called “linguistic relativity” or the “principle of linguistic relativity.” So while they have slightly different names, they refer to the same basic proposal about the relationship between language and thought.

How Language Influences Culture

Culture is defined by the values, norms, and beliefs of a society. Our culture can be considered a lens through which we undergo the world and develop a shared meaning of what occurs around us.

The language that we create and use is in response to the cultural and societal needs that arose. In other words, there is an apparent relationship between how we talk and how we perceive the world.

One crucial question that many intellectuals have asked is how our society’s language influences its culture.

Linguist and anthropologist Edward Sapir and his then-student Benjamin Whorf were interested in answering this question.

Together, they created the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which states that our thought processes predominantly determine how we look at the world.

Our language restricts our thought processes – our language shapes our reality. Simply, the language that we use shapes the way we think and how we see the world.

Since the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis theorizes that our language use shapes our perspective of the world, people who speak different languages have different views of the world.

In the 1920s, Benjamin Whorf was a Yale University graduate student studying with linguist Edward Sapir, who was considered the father of American linguistic anthropology.

Sapir was responsible for documenting and recording the cultures and languages of many Native American tribes disappearing at an alarming rate. He and his predecessors were well aware of the close relationship between language and culture.

Anthropologists like Sapir need to learn the language of the culture they are studying to understand the worldview of its speakers truly. Whorf believed that the opposite is also true, that language affects culture by influencing how its speakers think.

His hypothesis proposed that the words and structures of a language influence how its speaker behaves and feels about the world and, ultimately, the culture itself.

Simply put, Whorf believed that you see the world differently from another person who speaks another language due to the specific language you speak.

Human beings do not live in the matter-of-fact world alone, nor solitary in the world of social action as traditionally understood, but are very much at the pardon of the certain language which has become the medium of communication and expression for their society.

To a large extent, the real world is unconsciously built on habits in regard to the language of the group. We hear and see and otherwise experience broadly as we do because the language habits of our community predispose choices of interpretation.

Studies & Examples

The lexicon, or vocabulary, is the inventory of the articles a culture speaks about and has classified to understand the world around them and deal with it effectively.

For example, our modern life is dictated for many by the need to travel by some vehicle – cars, buses, trucks, SUVs, trains, etc. We, therefore, have thousands of words to talk about and mention, including types of models, vehicles, parts, or brands.

The most influential aspects of each culture are similarly reflected in the dictionary of its language. Among the societies living on the islands in the Pacific, fish have significant economic and cultural importance.

Therefore, this is reflected in the rich vocabulary that describes all aspects of the fish and the environments that islanders depend on for survival.

For example, there are over 1,000 fish species in Palau, and Palauan fishers knew, even long before biologists existed, details about the anatomy, behavior, growth patterns, and habitat of most of them – far more than modern biologists know today.

Whorf’s studies at Yale involved working with many Native American languages, including Hopi. He discovered that the Hopi language is quite different from English in many ways, especially regarding time.

Western cultures and languages view times as a flowing river that carries us continuously through the present, away from the past, and to the future.

Our grammar and system of verbs reflect this concept with particular tenses for past, present, and future.

We perceive this concept of time as universal in that all humans see it in the same way.

Although a speaker of Hopi has very different ideas, their language’s structure both reflects and shapes the way they think about time. Seemingly, the Hopi language has no present, past, or future tense; instead, they divide the world into manifested and unmanifest domains.

The manifested domain consists of the physical universe, including the present, the immediate past, and the future; the unmanifest domain consists of the remote past and the future and the world of dreams, thoughts, desires, and life forces.

Also, there are no words for minutes, minutes, or days of the week. Native Hopi speakers often had great difficulty adapting to life in the English-speaking world when it came to being on time for their job or other affairs.

It is due to the simple fact that this was not how they had been conditioned to behave concerning time in their Hopi world, which followed the phases of the moon and the movements of the sun.

Today, it is widely believed that some aspects of perception are affected by language.

One big problem with the original Sapir-Whorf hypothesis derives from the idea that if a person’s language has no word for a specific concept, then that person would not understand that concept.

Honestly, the idea that a mother tongue can restrict one’s understanding has been largely unaccepted. For example, in German, there is a term that means to take pleasure in another person’s unhappiness.

While there is no translatable equivalent in English, it just would not be accurate to say that English speakers have never experienced or would not be able to comprehend this emotion.

Just because there is no word for this in the English language does not mean English speakers are less equipped to feel or experience the meaning of the word.

Not to mention a “chicken and egg” problem with the theory.

Of course, languages are human creations, very much tools we invented and honed to suit our needs. Merely showing that speakers of diverse languages think differently does not tell us whether it is the language that shapes belief or the other way around.

Supporting Evidence

On the other hand, there is hard evidence that the language-associated habits we acquire play a role in how we view the world. And indeed, this is especially true for languages that attach genders to inanimate objects.

There was a study done that looked at how German and Spanish speakers view different things based on their given gender association in each respective language.

The results demonstrated that in describing things that are referred to as masculine in Spanish, speakers of the language marked them as having more male characteristics like “strong” and “long.” Similarly, these same items, which use feminine phrasings in German, were noted by German speakers as effeminate, like “beautiful” and “elegant.”

The findings imply that speakers of each language have developed preconceived notions of something being feminine or masculine, not due to the objects” characteristics or appearances but because of how they are categorized in their native language.

It is important to remember that the Theory of Linguistic Relativity (Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis) also successfully achieves openness. The theory is shown as a window where we view the cognitive process, not as an absolute.

It is set forth to look at a phenomenon differently than one usually would. Furthermore, the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis is very simple and logically sound. Understandably, one’s atmosphere and culture will affect decoding.

Likewise, in studies done by the authors of the theory, many Native American tribes do not have a word for particular things because they do not exist in their lives. The logical simplism of this idea of relativism provides parsimony.

Truly, the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis makes sense. It can be utilized in describing great numerous misunderstandings in everyday life. When a Pennsylvanian says “yuns,” it does not make any sense to a Californian, but when examined, it is just another word for “you all.”

The Linguistic Relativity Theory addresses this and suggests that it is all relative. This concept of relativity passes outside dialect boundaries and delves into the world of language – from different countries and, consequently, from mind to mind.

Is language reality honestly because of thought, or is it thought which occurs because of language? The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis very transparently presents a view of reality being expressed in language and thus forming in thought.

The principles rehashed in it show a reasonable and even simple idea of how one perceives the world, but the question is still arguable: thought then language or language then thought?

Modern Relevance

Regardless of its age, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, or the Linguistic Relativity Theory, has continued to force itself into linguistic conversations, even including pop culture.

The idea was just recently revisited in the movie “Arrival,” – a science fiction film that engagingly explores the ways in which an alien language can affect and alter human thinking.

And even if some of the most drastic claims of the theory have been debunked or argued against, the idea has continued its relevance, and that does say something about its importance.

Hypotheses, thoughts, and intellectual musings do not need to be totally accurate to remain in the public eye as long as they make us think and question the world – and the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis does precisely that.

The theory does not only make us question linguistic theory and our own language but also our very existence and how our perceptions might shape what exists in this world.

There are generalities that we can expect every person to encounter in their day-to-day life – in relationships, love, work, sadness, and so on. But thinking about the more granular disparities experienced by those in diverse circumstances, linguistic or otherwise, helps us realize that there is more to the story than ours.

And beautifully, at the same time, the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis reiterates the fact that we are more alike than we are different, regardless of the language we speak.

Isn’t it just amazing that linguistic diversity just reveals to us how ingenious and flexible the human mind is – human minds have invented not one cognitive universe but, indeed, seven thousand!

Kay, P., & Kempton, W. (1984). What is the Sapir‐Whorf hypothesis?. American anthropologist, 86(1), 65-79.

Whorf, B. L. (1952). Language, mind, and reality. ETC: A review of general semantics, 167-188.

Whorf, B. L. (1997). The relation of habitual thought and behavior to language. In Sociolinguistics (pp. 443-463). Palgrave, London.

Whorf, B. L. (2012). Language, thought, and reality: Selected writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. MIT press.

Related Articles

Cognitive Psychology

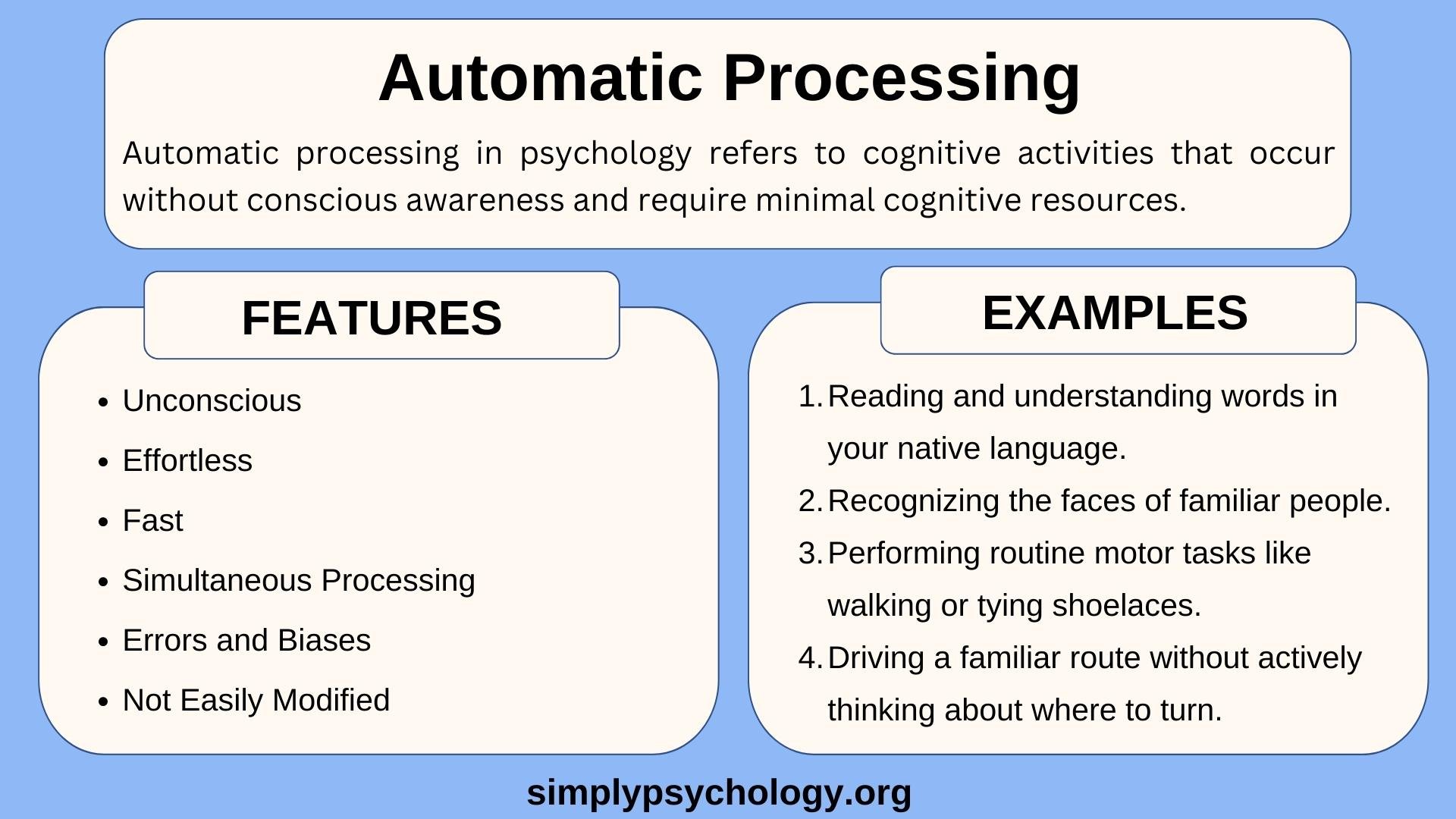

Automatic Processing in Psychology: Definition & Examples

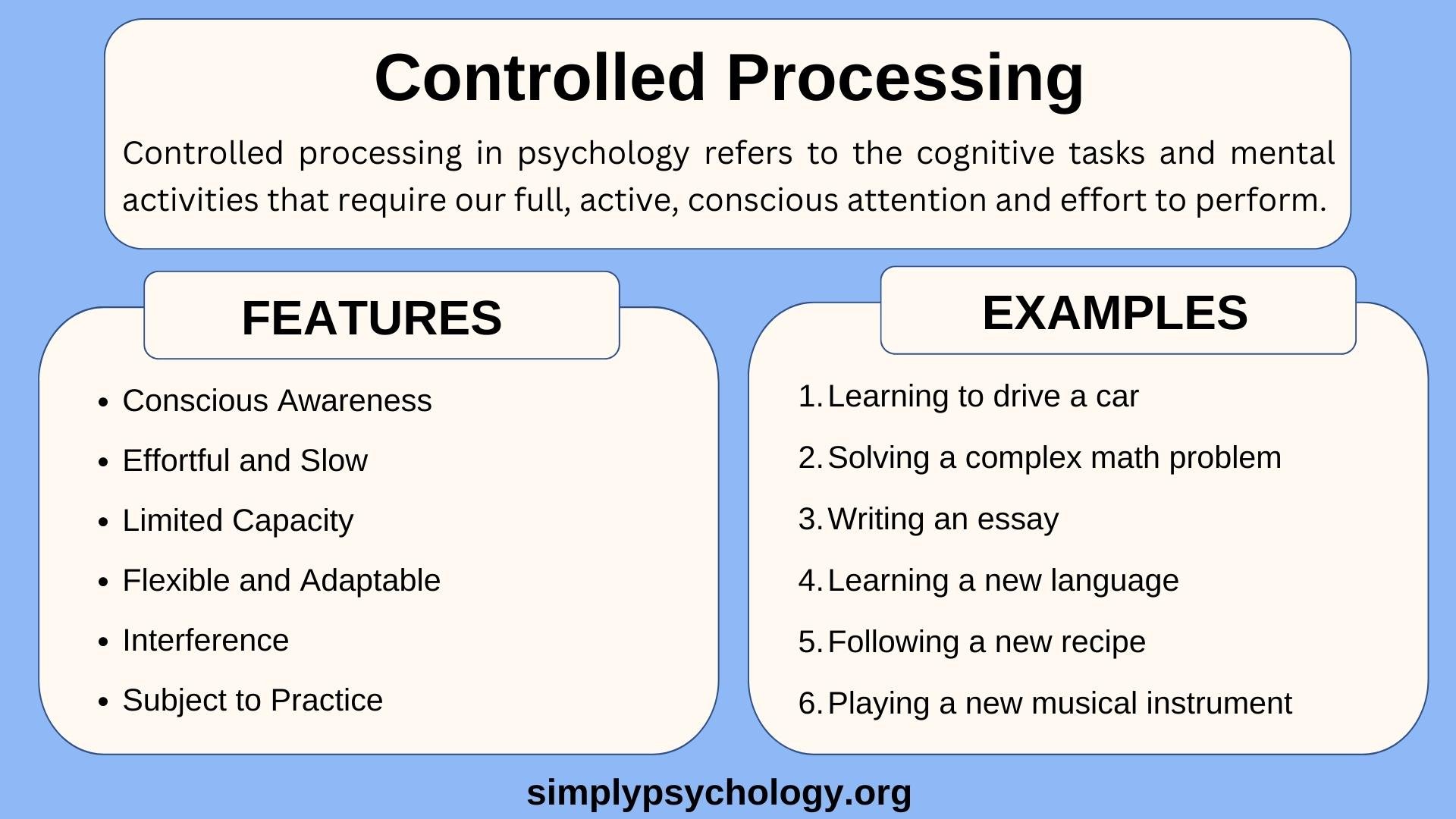

Controlled Processing in Psychology: Definition & Examples

How Ego Depletion Can Drain Your Willpower

What is the Default Mode Network?

Theories of Selective Attention in Psychology

Availability Heuristic and Decision Making

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Back to Entry

- Entry Contents

- Entry Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Supplement to Philosophy of Linguistics

Whorfianism.

Emergentists tend to follow Edward Sapir in taking an interest in interlinguistic and intralinguistic variation. Linguistic anthropologists have explicitly taken up the task of defending a famous claim associated with Sapir that connects linguistic variation to differences in thinking and cognition more generally. The claim is very often referred to as the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis (though this is a largely infelicitous label, as we shall see).

This topic is closely related to various forms of relativism—epistemological, ontological, conceptual, and moral—and its general outlines are discussed elsewhere in this encyclopedia; see the section on language in the Summer 2015 archived version of the entry on relativism (§3.1). Cultural versions of moral relativism suggest that, given how much cultures differ, what is moral for you might depend on the culture you were brought up in. A somewhat analogous view would suggest that, given how much language structures differ, what is thinkable for you might depend on the language you use. (This is actually a kind of conceptual relativism, but it is generally called linguistic relativism, and we will continue that practice.)

Even a brief skim of the vast literature on the topic is not remotely plausible in this article; and the primary literature is in any case more often polemical than enlightening. It certainly holds no general answer to what science has discovered about the influences of language on thought. Here we offer just a limited discussion of the alleged hypothesis and the rhetoric used in discussing it, the vapid and not so vapid forms it takes, and the prospects for actually devising testable scientific hypotheses about the influence of language on thought.

Whorf himself did not offer a hypothesis. He presented his “new principle of linguistic relativity” (Whorf 1956: 214) as a fact discovered by linguistic analysis:

When linguists became able to examine critically and scientifically a large number of languages of widely different patterns, their base of reference was expanded; they experienced an interruption of phenomena hitherto held universal, and a whole new order of significances came into their ken. It was found that the background linguistic system (in other words, the grammar) of each language is not merely a reproducing instrument for voicing ideas but rather is itself the shaper of ideas, the program and guide for the individual’s mental activity, for his analysis of impressions, for his synthesis of his mental stock in trade. Formulation of ideas is not an independent process, strictly rational in the old sense, but is part of a particular grammar, and differs, from slightly to greatly, between different grammars. We dissect nature along lines laid down by our native languages. The categories and types that we isolate from the world of phenomena we do not find there because they stare every observer in the face; on the contrary, the world is presented in a kaleidoscopic flux of impressions which has to be organized by our minds—and this means largely by the linguistic systems in our minds. We cut nature up, organize it into concepts, and ascribe significances as we do, largely because we are parties to an agreement to organize it in this way—an agreement that holds throughout our speech community and is codified in the patterns of our language. The agreement is, of course, an implicit and unstated one, but its terms are absolutely obligatory ; we cannot talk at all except by subscribing to the organization and classification of data which the agreement decrees. (Whorf 1956: 212–214; emphasis in original)

Later, Whorf’s speculations about the “sensuously and operationally different” character of different snow types for “an Eskimo” (Whorf 1956: 216) developed into a familiar journalistic meme about the Inuit having dozens or scores or hundreds of words for snow; but few who repeat that urban legend recall Whorf’s emphasis on its being grammar, rather than lexicon, that cuts up and organizes nature for us.

In an article written in 1937, posthumously published in an academic journal (Whorf 1956: 87–101), Whorf clarifies what is most important about the effects of language on thought and world-view. He distinguishes ‘phenotypes’, which are overt grammatical categories typically indicated by morphemic markers, from what he called ‘cryptotypes’, which are covert grammatical categories, marked only implicitly by distributional patterns in a language that are not immediately apparent. In English, the past tense would be an example of a phenotype (it is marked by the - ed suffix in all regular verbs). Gender in personal names and common nouns would be an example of a cryptotype, not systematically marked by anything. In a cryptotype, “class membership of the word is not apparent until there is a question of using it or referring to it in one of these special types of sentence, and then we find that this word belongs to a class requiring some sort of distinctive treatment, which may even be the negative treatment of excluding that type of sentence” (p. 89).

Whorf’s point is the familiar one that linguistic structure is comprised, in part, of distributional patterns in language use that are not explicitly marked. What follows from this, according to Whorf, is not that the existing lexemes in a language (like its words for snow) comprise covert linguistic structure, but that patterns shared by word classes constitute linguistic structure. In ‘Language, mind, and reality’ (1942; published posthumously in Theosophist , a magazine published in India for the followers of the 19th-century spiritualist Helena Blavatsky) he wrote:

Because of the systematic, configurative nature of higher mind, the “patternment” aspect of language always overrides and controls the “lexation”…or name-giving aspect. Hence the meanings of specific words are less important than we fondly fancy. Sentences, not words, are the essence of speech, just as equations and functions, and not bare numbers, are the real meat of mathematics. We are all mistaken in our common belief that any word has an “exact meaning.” We have seen that the higher mind deals in symbols that have no fixed reference to anything, but are like blank checks, to be filled in as required, that stand for “any value” of a given variable, like …the x , y , z of algebra. (Whorf 1942: 258)

Whorf apparently thought that only personal and proper names have an exact meaning or reference (Whorf 1956: 259).

For Whorf, it was an unquestionable fact that language influences thought to some degree:

Actually, thinking is most mysterious, and by far the greatest light upon it that we have is thrown by the study of language. This study shows that the forms of a person’s thoughts are controlled by inexorable laws of pattern of which he is unconscious. These patterns are the unperceived intricate systematizations of his own language—shown readily enough by a candid comparison and contrast with other languages, especially those of a different linguistic family. His thinking itself is in a language—in English, in Sanskrit, in Chinese. [footnote omitted] And every language is a vast pattern-system, different from others, in which are culturally ordained the forms and categories by which the personality not only communicates, but analyzes nature, notices or neglects types of relationship and phenomena, channels his reasoning, and builds the house of his consciousness. (Whorf 1956: 252)

He seems to regard it as necessarily true that language affects thought, given

- the fact that language must be used in order to think, and

- the facts about language structure that linguistic analysis discovers.

He also seems to presume that the only structure and logic that thought has is grammatical structure. These views are not the ones that after Whorf’s death came to be known as ‘the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis’ (a sobriquet due to Hoijer 1954). Nor are they what was called the ‘Whorf thesis’ by Brown and Lenneberg (1954) which was concerned with the relation of obligatory lexical distinctions and thought. Brown and Lenneberg (1954) investigated this question by looking at the relation of color terminology in a language and the classificatory abilities of the speakers of that language. The issue of the relation between obligatory lexical distinctions and thought is at the heart of what is now called ‘the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis’ or ‘the Whorf Hypothesis’ or ‘Whorfianism’.

1. Banal Whorfianism

No one is going to be impressed with a claim that some aspect of your language may affect how you think in some way or other; that is neither a philosophical thesis nor a psychological hypothesis. So it is appropriate to set aside entirely the kind of so-called hypotheses that Steven Pinker presents in The Stuff of Thought (2007: 126–128) as “five banal versions of the Whorfian hypothesis”:

- “Language affects thought because we get much of our knowledge through reading and conversation.”

- “A sentence can frame an event, affecting the way people construe it.”

- “The stock of words in a language reflects the kinds of things its speakers deal with in their lives and hence think about.”

- “[I]f one uses the word language in a loose way to refer to meanings,… then language is thought.”

- “When people think about an entity, among the many attributes they can think about is its name.”

These are just truisms, unrelated to any serious issue about linguistic relativism.

We should also set aside some methodological versions of linguistic relativism discussed in anthropology. It may be excellent advice to a budding anthropologist to be aware of linguistic diversity, and to be on the lookout for ways in which your language may affect your judgment of other cultures; but such advice does not constitute a hypothesis.

2. The so-called Sapir-Whorf hypothesis

The term “Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis” was coined by Harry Hoijer in his contribution (Hoijer 1954) to a conference on the work of Benjamin Lee Whorf in 1953. But anyone looking in Hoijer’s paper for a clear statement of the hypothesis will look in vain. Curiously, despite his stated intent “to review and clarify the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis” (1954: 93), Hoijer did not even attempt to state it. The closest he came was this:

The central idea of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is that language functions, not simply as a device for reporting experience, but also, and more significantly, as a way of defining experience for its speakers.

The claim that “language functions…as a way of defining experience” appears to be offered as a kind of vague metaphysical insight rather than either a statement of linguistic relativism or a testable hypothesis.

And if Hoijer seriously meant that what qualitative experiences a speaker can have are constituted by that speaker’s language, then surely the claim is false. There is no reason to doubt that non-linguistic sentient creatures like cats can experience (for example) pain or heat or hunger, so having a language is not a necessary condition for having experiences. And it is surely not sufficient either: a robot with a sophisticated natural language processing capacity could be designed without the capacity for conscious experience.

In short, it is a mystery what Hoijer meant by his “central idea”.

Vague remarks of the same loosely metaphysical sort have continued to be a feature of the literature down to the present. The statements made in some recent papers, even in respected refereed journals, contain non-sequiturs echoing some of the remarks of Sapir, Whorf, and Hoijer. And they come from both sides of the debate.

3. Anti-Whorfian rhetoric

Lila Gleitman is an Essentialist on the other side of the contemporary debate: she is against linguistic relativism, and against the broadly Whorfian work of Stephen Levinson’s group at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics. In the context of criticizing a particular research design, Li and Gleitman (2002) quote Whorf’s claim that “language is the factor that limits free plasticity and rigidifies channels of development”. But in the claim cited, Whorf seems to be talking about the psychological topic that holds universally of human conceptual development, not claiming that linguistic relativism is true.

Li and Gleitman then claim (p. 266) that such (Whorfian) views “have diminished considerably in academic favor” in part because of “the universalist position of Chomskian linguistics, with its potential for explaining the striking similarity of language learning in children all over the world.” But there is no clear conflict or even a conceptual connection between Whorf’s views about language placing limits on developmental plasticity, and Chomsky’s thesis of an innate universal architecture for syntax. In short, there is no reason why Chomsky’s I-languages could not be innately constrained, but (once acquired) cognitively and developmentally constraining.

For example, the supposedly deep linguistic universal of ‘recursion’ (Hauser et al. 2002) is surely quite independent of whether the inventory of colour-name lexemes in your language influences the speed with which you can discriminate between color chips. And conversely, universal tendencies in color naming across languages (Kay and Regier 2006) do not show that color-naming differences among languages are without effect on categorical perception (Thierry et al. 2009).

4. Strong and weak Whorfianism

One of the first linguists to defend a general form of universalism against linguistic relativism, thus presupposing that they conflict, was Julia Penn (1972). She was also an early popularizer of the distinction between ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ formulations of the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis (and an opponent of the ‘strong’ version).

‘Weak’ versions of Whorfianism state that language influences or defeasibly shapes thought. ‘Strong’ versions state that language determines thought, or fixes it in some way. The weak versions are commonly dismissed as banal (because of course there must be some influence), and the stronger versions as implausible.

The weak versions are considered banal because they are not adequately formulated as testable hypotheses that could conflict with relevant evidence about language and thought.

Why would the strong versions be thought implausible? For a language to make us think in a particular way, it might seem that it must at least temporarily prevent us from thinking in other ways, and thus make some thoughts not only inexpressible but unthinkable. If this were true, then strong Whorfianism would conflict with the Katzian effability claim. There would be thoughts that a person couldn’t think because of the language(s) they speak.

Some are fascinated by the idea that there are inaccessible thoughts; and the notion that learning a new language gives access to entirely new thoughts and concepts seems to be a staple of popular writing about the virtues of learning languages. But many scientists and philosophers intuitively rebel against violations of effability: thinking about concepts that no one has yet named is part of their job description.

The resolution lies in seeing that the language could affect certain aspects of our cognitive functioning without making certain thoughts unthinkable for us .

For example, Greek has separate terms for what we call light blue and dark blue, and no word meaning what ‘blue’ means in English: Greek forces a choice on this distinction. Experiments have shown (Thierry et al. 2009) that native speakers of Greek react faster when categorizing light blue and dark blue color chips—apparently a genuine effect of language on thought. But that does not make English speakers blind to the distinction, or imply that Greek speakers cannot grasp the idea of a hue falling somewhere between green and violet in the spectrum.

There is no general or global ineffability problem. There is, though, a peculiar aspect of strong Whorfian claims, giving them a local analog of ineffability: the content of such a claim cannot be expressed in any language it is true of . This does not make the claims self-undermining (as with the standard objections to relativism); it doesn’t even mean that they are untestable. They are somewhat anomalous, but nothing follows concerning the speakers of the language in question (except that they cannot state the hypothesis using the basic vocabulary and grammar that they ordinarily use).

If there were a true hypothesis about the limits that basic English vocabulary and constructions puts on what English speakers can think, the hypothesis would turn out to be inexpressible in English, using basic vocabulary and the usual repertoire of constructions. That might mean it would be hard for us to discuss it in an article in English unless we used terminological innovations or syntactic workarounds. But that doesn’t imply anything about English speakers’ ability to grasp concepts, or to develop new ways of expressing them by coining new words or elaborated syntax.

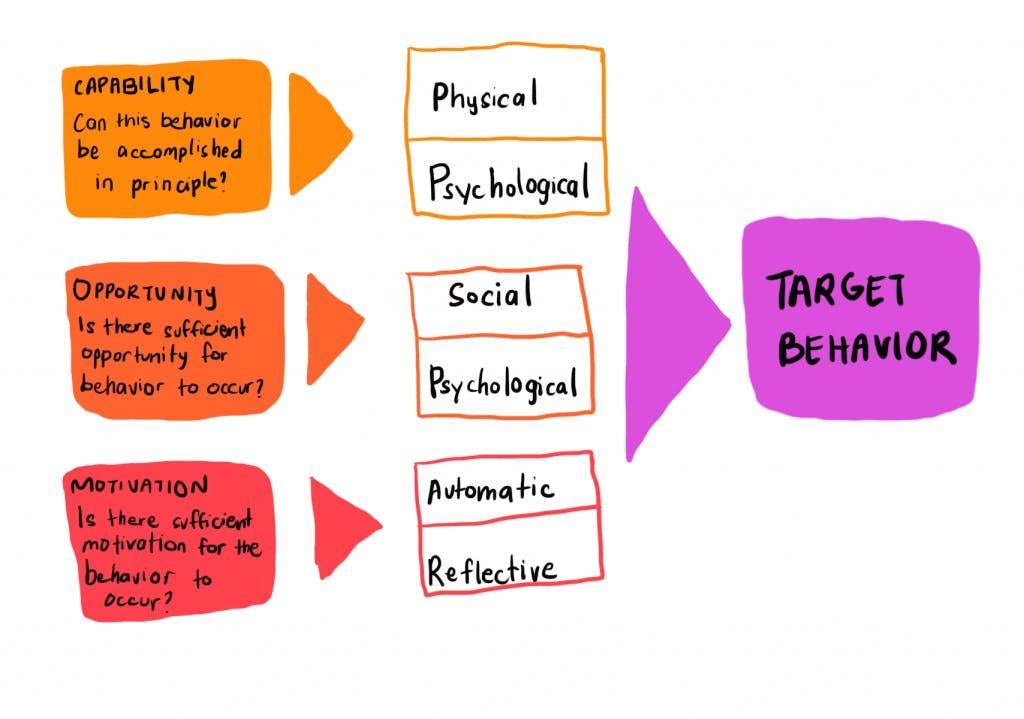

5. Constructing and evaluating Whorfian hypotheses

A number of considerations are relevant to formulating, testing, and evaluating Whorfian hypotheses.

Genuine hypotheses about the effects of language on thought will always have a duality: there will be a linguistic part and a non-linguistic one. The linguistic part will involve a claim that some feature is present in one language but absent in another.

Whorf himself saw that it was only obligatory features of languages that established “mental patterns” or “habitual thought” (Whorf 1956: 139), since if it were optional then the speaker could optionally do it one way or do it the other way. And so this would not be a case of “constraining the conceptual structure”. So we will likewise restrict our attention to obligatory features here.

Examples of relevant obligatory features would include lexical distinctions like the light vs. dark blue forced choice in Greek, or the forced choice between “in (fitting tightly)” vs. “in (fitting loosely)” in Korean. They also include grammatical distinctions like the forced choice in Spanish 2nd-person pronouns between informal/intimate and formal/distant (informal tú vs. formal usted in the singular; informal vosotros vs. formal ustedes in the plural), or the forced choice in Tamil 1st-person plural pronouns between inclusive (“we = me and you and perhaps others”) and exclusive (“we = me and others not including you”).

The non-linguistic part of a Whorfian hypothesis will contrast the psychological effects that habitually using the two languages has on their speakers. For example, one might conjecture that the habitual use of Spanish induces its speakers to be sensitive to the formal and informal character of the speaker’s relationship with their interlocutor while habitually using English does not.

So testing Whorfian hypotheses requires testing two independent hypotheses with the appropriate kinds of data. In consequence, evaluating them requires the expertise of both linguistics and psychology, and is a multidisciplinary enterprise. Clearly, the linguistic hypothesis may hold up where the psychological hypothesis does not, or conversely.

In addition, if linguists discovered that some linguistic feature was optional in two different languages, then even if psychological experiments showed differences between the two populations of speakers, this would not show linguistic determination or influence. The cognitive differences might depend on (say) cultural differences.

A further important consideration concerns the strength of the inducement relationship that a Whorfian hypothesis posits between a speaker’s language and their non-linguistic capacities. The claim that your language shapes or influences your cognition is quite different from the claim that your language makes certain kinds of cognition impossible (or obligatory) for you. The strength of any Whorfian hypothesis will vary depending on the kind of relationship being claimed, and the ease of revisability of that relation.

A testable Whorfian hypothesis will have a schematic form something like this:

- Linguistic part : Feature F is obligatory in L 1 but optional in L 2 .

- Psychological part : Speaking a language with obligatory feature F bears relation R to the cognitive effect C .

The relation R might in principle be causation or determination, but it is important to see that it might merely be correlation, or slight favoring; and the non-linguistic cognitive effect C might be readily suppressible or revisable.

Dan Slobin (1996) presents a view that competes with Whorfian hypotheses as standardly understood. He hypothesizes that when the speakers are using their cognitive abilities in the service of a linguistic ability (speaking, writing, translating, etc.), the language they are planning to use to express their thought will have a temporary online effect on how they express their thought. The claim is that as long as language users are thinking in order to frame their speech or writing or translation in some language, the mandatory features of that language will influence the way they think.

On Slobin’s view, these effects quickly attenuate as soon as the activity of thinking for speaking ends. For example, if a speaker is thinking for writing in Spanish, then Slobin’s hypothesis would predict that given the obligatory formal/informal 2nd-person pronoun distinction they would pay greater attention to the formal/informal character of their social relationships with their audience than if they were writing in English. But this effect is not permanent. As soon as they stop thinking for speaking, the effect of Spanish on their thought ends.

Slobin’s non-Whorfian linguistic relativist hypothesis raises the importance of psychological research on bilinguals or people who currently use two or more languages with a native or near-native facility. This is because one clear way to test Slobin-like hypotheses relative to Whorfian hypotheses would be to find out whether language correlated non-linguistic cognitive differences between speakers hold for bilinguals only when are thinking for speaking in one language, but not when they are thinking for speaking in some other language. If the relevant cognitive differences appeared and disappeared depending on which language speakers were planning to express themselves in, it would go some way to vindicate Slobin-like hypotheses over more traditional Whorfian Hypotheses. Of course, one could alternately accept a broadening of Whorfian hypotheses to include Slobin-like evanescent effects. Either way, attention must be paid to the persistence and revisability of the linguistic effects.

Kousta et al. (2008) shows that “for bilinguals there is intraspeaker relativity in semantic representations and, therefore, [grammatical] gender does not have a conceptual, non-linguistic effect” (843). Grammatical gender is obligatory in the languages in which it occurs and has been claimed by Whorfians to have persistent and enduring non-linguistic effects on representations of objects (Boroditsky et al. 2003). However, Kousta et al. supports the claim that bilinguals’ semantic representations vary depending on which language they are using, and thus have transient effects. This suggests that although some semantic representations of objects may vary from language to language, their non-linguistic cognitive effects are transitory.

Some advocates of Whorfianism have held that if Whorfian hypotheses were true, then meaning would be globally and radically indeterminate. Thus, the truth of Whorfian hypotheses is equated with global linguistic relativism—a well known self-undermining form of relativism. But as we have seen, not all Whorfian hypotheses are global hypotheses: they are about what is induced by particular linguistic features. And the associated non-linguistic perceptual and cognitive differences can be quite small, perhaps insignificant. For example, Thierry et al. (2009) provides evidence that an obligatory lexical distinction between light and dark blue affects Greek speakers’ color perception in the left hemisphere only. And the question of the degree to which this affects sensuous experience is not addressed.

The fact that Whorfian hypotheses need not be global linguistic relativist hypotheses means that they do not conflict with the claim that there are language universals. Structuralists of the first half of the 20th century tended to disfavor the idea of universals: Martin Joos’s characterization of structuralist linguistics as claiming that “languages can differ without limit as to either extent or direction” (Joos 1966, 228) has been much quoted in this connection. If the claim that languages can vary without limit were conjoined with the claim that languages have significant and permanent effects on the concepts and worldview of their speakers, a truly profound global linguistic relativism would result. But neither conjunct should be accepted. Joos’s remark is regarded by nearly all linguists today as overstated (and merely a caricature of the structuralists), and Whorfian hypotheses do not have to take a global or deterministic form.

John Lucy, a conscientious and conservative researcher of Whorfian hypotheses, has remarked:

We still know little about the connections between particular language patterns and mental life—let alone how they operate or how significant they are…a mere handful of empirical studies address the linguistic relativity proposal directly and nearly all are conceptually flawed. (Lucy 1996, 37)

Although further empirical studies on Whorfian hypotheses have been completed since Lucy published his 1996 review article, it is hard to find any that have satisfied the criteria of:

- adequately utilizing both the relevant linguistic and psychological research,

- focusing on obligatory rather than optional linguistic features,

- stating hypotheses in a clear testable way, and

- ruling out relevant competing Slobin-like hypotheses.

There is much important work yet to be done on testing the range of Whorfian hypotheses and other forms of linguistic conceptual relativism, and on understanding the significance of any Whorfian hypotheses that turn out to be well supported.

Copyright © 2024 by Barbara C. Scholz Francis Jeffry Pelletier < francisp @ ualberta . ca > Geoffrey K. Pullum < pullum @ gmail . com > Ryan Nefdt < ryan . nefdt @ uct . ac . za >

- Accessibility

Support SEP

Mirror sites.

View this site from another server:

- Info about mirror sites

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is copyright © 2024 by The Metaphysics Research Lab , Department of Philosophy, Stanford University

Library of Congress Catalog Data: ISSN 1095-5054

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis: How Language Influences How We Express Ourselves

Rachael is a New York-based writer and freelance writer for Verywell Mind, where she leverages her decades of personal experience with and research on mental illness—particularly ADHD and depression—to help readers better understand how their mind works and how to manage their mental health.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/RachaelGreenProfilePicture1-a3b8368ef3bb47ccbac92c5cc088e24d.jpg)

Thomas Barwick / Getty Images

What to Know About the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

Real-world examples of linguistic relativity, linguistic relativity in psychology.

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, also known as linguistic relativity, refers to the idea that the language a person speaks can influence their worldview, thought, and even how they experience and understand the world.

While more extreme versions of the hypothesis have largely been discredited, a growing body of research has demonstrated that language can meaningfully shape how we understand the world around us and even ourselves.

Keep reading to learn more about linguistic relativity, including some real-world examples of how it shapes thoughts, emotions, and behavior.

The hypothesis is named after anthropologist and linguist Edward Sapir and his student, Benjamin Lee Whorf. While the hypothesis is named after them both, the two never actually formally co-authored a coherent hypothesis together.

This Hypothesis Aims to Figure Out How Language and Culture Are Connected

Sapir was interested in charting the difference in language and cultural worldviews, including how language and culture influence each other. Whorf took this work on how language and culture shape each other a step further to explore how different languages might shape thought and behavior.

Since then, the concept has evolved into multiple variations, some more credible than others.

Linguistic Determinism Is an Extreme Version of the Hypothesis

Linguistic determinism, for example, is a more extreme version suggesting that a person’s perception and thought are limited to the language they speak. An early example of linguistic determinism comes from Whorf himself who argued that the Hopi people in Arizona don’t conjugate verbs into past, present, and future tenses as English speakers do and that their words for units of time (like “day” or “hour”) were verbs rather than nouns.

From this, he concluded that the Hopi don’t view time as a physical object that can be counted out in minutes and hours the way English speakers do. Instead, Whorf argued, the Hopi view time as a formless process.

This was then taken by others to mean that the Hopi don’t have any concept of time—an extreme view that has since been repeatedly disproven.

There is some evidence for a more nuanced version of linguistic relativity, which suggests that the structure and vocabulary of the language you speak can influence how you understand the world around you. To understand this better, it helps to look at real-world examples of the effects language can have on thought and behavior.

Different Languages Express Colors Differently

Color is one of the most common examples of linguistic relativity. Most known languages have somewhere between two and twelve color terms, and the way colors are categorized varies widely. In English, for example, there are distinct categories for blue and green .

Blue and Green

But in Korean, there is one word that encompasses both. This doesn’t mean Korean speakers can’t see blue, it just means blue is understood as a variant of green rather than a distinct color category all its own.

In Russian, meanwhile, the colors that English speakers would lump under the umbrella term of “blue” are further subdivided into two distinct color categories, “siniy” and “goluboy.” They roughly correspond to light blue and dark blue in English. But to Russian speakers, they are as distinct as orange and brown .

In one study comparing English and Russian speakers, participants were shown a color square and then asked to choose which of the two color squares below it was the closest in shade to the first square.

The test specifically focused on varying shades of blue ranging from “siniy” to “goluboy.” Russian speakers were not only faster at selecting the matching color square but were more accurate in their selections.

The Way Location Is Expressed Varies Across Languages

This same variation occurs in other areas of language. For example, in Guugu Ymithirr, a language spoken by Aboriginal Australians, spatial orientation is always described in absolute terms of cardinal directions. While an English speaker would say the laptop is “in front of” you, a Guugu Ymithirr speaker would say it was north, south, west, or east of you.

As a result, Aboriginal Australians have to be constantly attuned to cardinal directions because their language requires it (just as Russian speakers develop a more instinctive ability to discern between shades of what English speakers call blue because their language requires it).

So when you ask a Guugu Ymithirr speaker to tell you which way south is, they can point in the right direction without a moment’s hesitation. Meanwhile, most English speakers would struggle to accurately identify South without the help of a compass or taking a moment to recall grade school lessons about how to find it.

The concept of these cardinal directions exists in English, but English speakers aren’t required to think about or use them on a daily basis so it’s not as intuitive or ingrained in how they orient themselves in space.

Just as with other aspects of thought and perception, the vocabulary and grammatical structure we have for thinking about or talking about what we feel doesn’t create our feelings, but it does shape how we understand them and, to an extent, how we experience them.

Words Help Us Put a Name to Our Emotions

For example, the ability to detect displeasure from a person’s face is universal. But in a language that has the words “angry” and “sad,” you can further distinguish what kind of displeasure you observe in their facial expression. This doesn’t mean humans never experienced anger or sadness before words for them emerged. But they may have struggled to understand or explain the subtle differences between different dimensions of displeasure.

In one study of English speakers, toddlers were shown a picture of a person with an angry facial expression. Then, they were given a set of pictures of people displaying different expressions including happy, sad, surprised, scared, disgusted, or angry. Researchers asked them to put all the pictures that matched the first angry face picture into a box.

The two-year-olds in the experiment tended to place all faces except happy faces into the box. But four-year-olds were more selective, often leaving out sad or fearful faces as well as happy faces. This suggests that as our vocabulary for talking about emotions expands, so does our ability to understand and distinguish those emotions.

But some research suggests the influence is not limited to just developing a wider vocabulary for categorizing emotions. Language may “also help constitute emotion by cohering sensations into specific perceptions of ‘anger,’ ‘disgust,’ ‘fear,’ etc.,” said Dr. Harold Hong, a board-certified psychiatrist at New Waters Recovery in North Carolina.

As our vocabulary for talking about emotions expands, so does our ability to understand and distinguish those emotions.

Words for emotions, like words for colors, are an attempt to categorize a spectrum of sensations into a handful of distinct categories. And, like color, there’s no objective or hard rule on where the boundaries between emotions should be which can lead to variation across languages in how emotions are categorized.

Emotions Are Categorized Differently in Different Languages

Just as different languages categorize color a little differently, researchers have also found differences in how emotions are categorized. In German, for example, there’s an emotion called “gemütlichkeit.”

While it’s usually translated as “cozy” or “ friendly ” in English, there really isn’t a direct translation. It refers to a particular kind of peace and sense of belonging that a person feels when surrounded by the people they love or feel connected to in a place they feel comfortable and free to be who they are.

Harold Hong, MD, Psychiatrist

The lack of a word for an emotion in a language does not mean that its speakers don't experience that emotion.

You may have felt gemütlichkeit when staying up with your friends to joke and play games at a sleepover. You may feel it when you visit home for the holidays and spend your time eating, laughing, and reminiscing with your family in the house you grew up in.

In Japanese, the word “amae” is just as difficult to translate into English. Usually, it’s translated as "spoiled child" or "presumed indulgence," as in making a request and assuming it will be indulged. But both of those have strong negative connotations in English and amae is a positive emotion .

Instead of being spoiled or coddled, it’s referring to that particular kind of trust and assurance that comes with being nurtured by someone and knowing that you can ask for what you want without worrying whether the other person might feel resentful or burdened by your request.

You might have felt amae when your car broke down and you immediately called your mom to pick you up, without having to worry for even a second whether or not she would drop everything to help you.

Regardless of which languages you speak, though, you’re capable of feeling both of these emotions. “The lack of a word for an emotion in a language does not mean that its speakers don't experience that emotion,” Dr. Hong explained.

What This Means For You

“While having the words to describe emotions can help us better understand and regulate them, it is possible to experience and express those emotions without specific labels for them.” Without the words for these feelings, you can still feel them but you just might not be able to identify them as readily or clearly as someone who does have those words.

Rhee S. Lexicalization patterns in color naming in Korean . In: Raffaelli I, Katunar D, Kerovec B, eds. Studies in Functional and Structural Linguistics. Vol 78. John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2019:109-128. Doi:10.1075/sfsl.78.06rhe

Winawer J, Witthoft N, Frank MC, Wu L, Wade AR, Boroditsky L. Russian blues reveal effects of language on color discrimination . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(19):7780-7785. 10.1073/pnas.0701644104

Lindquist KA, MacCormack JK, Shablack H. The role of language in emotion: predictions from psychological constructionism . Front Psychol. 2015;6. Doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00444

By Rachael Green Rachael is a New York-based writer and freelance writer for Verywell Mind, where she leverages her decades of personal experience with and research on mental illness—particularly ADHD and depression—to help readers better understand how their mind works and how to manage their mental health.

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Linguistic Theory

DrAfter123/Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is the linguistic theory that the semantic structure of a language shapes or limits the ways in which a speaker forms conceptions of the world. It came about in 1929. The theory is named after the American anthropological linguist Edward Sapir (1884–1939) and his student Benjamin Whorf (1897–1941). It is also known as the theory of linguistic relativity, linguistic relativism, linguistic determinism, Whorfian hypothesis , and Whorfianism .

History of the Theory

The idea that a person's native language determines how he or she thinks was popular among behaviorists of the 1930s and on until cognitive psychology theories came about, beginning in the 1950s and increasing in influence in the 1960s. (Behaviorism taught that behavior is a result of external conditioning and doesn't take feelings, emotions, and thoughts into account as affecting behavior. Cognitive psychology studies mental processes such as creative thinking, problem-solving, and attention.)

Author Lera Boroditsky gave some background on ideas about the connections between languages and thought:

"The question of whether languages shape the way we think goes back centuries; Charlemagne proclaimed that 'to have a second language is to have a second soul.' But the idea went out of favor with scientists when Noam Chomsky 's theories of language gained popularity in the 1960s and '70s. Dr. Chomsky proposed that there is a universal grammar for all human languages—essentially, that languages don't really differ from one another in significant ways...." ("Lost in Translation." "The Wall Street Journal," July 30, 2010)

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis was taught in courses through the early 1970s and had become widely accepted as truth, but then it fell out of favor. By the 1990s, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis was left for dead, author Steven Pinker wrote. "The cognitive revolution in psychology, which made the study of pure thought possible, and a number of studies showing meager effects of language on concepts, appeared to kill the concept in the 1990s... But recently it has been resurrected, and 'neo-Whorfianism' is now an active research topic in psycholinguistics ." ("The Stuff of Thought. "Viking, 2007)

Neo-Whorfianism is essentially a weaker version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis and says that language influences a speaker's view of the world but does not inescapably determine it.

The Theory's Flaws

One big problem with the original Sapir-Whorf hypothesis stems from the idea that if a person's language has no word for a particular concept, then that person would not be able to understand that concept, which is untrue. Language doesn't necessarily control humans' ability to reason or have an emotional response to something or some idea. For example, take the German word sturmfrei , which essentially is the feeling when you have the whole house to yourself because your parents or roommates are away. Just because English doesn't have a single word for the idea doesn't mean that Americans can't understand the concept.

There's also the "chicken and egg" problem with the theory. "Languages, of course, are human creations, tools we invent and hone to suit our needs," Boroditsky continued. "Simply showing that speakers of different languages think differently doesn't tell us whether it's language that shapes thought or the other way around."

- Definition and Discussion of Chomskyan Linguistics

- Generative Grammar: Definition and Examples

- Cognitive Grammar

- Universal Grammar (UG)

- Linguistic Performance

- What Is a Natural Language?

- Linguistic Competence: Definition and Examples

- Transformational Grammar (TG) Definition and Examples

- What Is Linguistic Functionalism?

- 24 Words Worth Borrowing From Other Languages

- The Theory of Poverty of the Stimulus in Language Development

- Definition and Examples of Case Grammar

- The Definition and Usage of Optimality Theory

- An Introduction to Semantics

- Construction Grammar

- 10 Types of Grammar (and Counting)

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.1: Linguistic Relativity- The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 75159

- Manon Allard-Kropp

- University of Missouri–St. Louis

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

After completing this module, students will be able to:

1. Define the concept of linguistic relativity

2. Differentiate linguistic relativity and linguistic determinism

3. Define the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis (against more pop-culture takes on it) and situate it in a broader theoretical context/history

4. Provide examples of linguistic relativity through examples related to time, space, metaphors, etc.

In this part, we will look at language(s) and worldviews at the intersection of language & thoughts and language & cognition (i.e., the mental system with which we process the world around us, and with which we learn to function and make sense of it). Our main question, which we will not entirely answer but which we will examine in depth, is a chicken and egg one: does thought determine language, or does language inform thought?

We will talk about the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis; look at examples that support the notion of linguistic relativity (pronouns, kinship terms, grammatical tenses, and what they tell us about culture and worldview); and then we will more specifically look into how metaphors are a structural component of worldview, if not cognition itself; and we will wrap up with memes. (Can we analyze memes through an ethnolinguistic, relativist lens? We will try!)

3.1 Linguistic Relativity: The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

In the 1920s, Benjamin Whorf was a graduate student studying with linguist Edward Sapir at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Sapir, considered the father of American linguistic anthropology, was responsible for documenting and recording the languages and cultures of many Native American tribes, which were disappearing at an alarming rate. This was due primarily to the deliberate efforts of the United States government to force Native Americans to assimilate into the Euro-American culture. Sapir and his predecessors were well aware of the close relationship between culture and language because each culture is reflected in and influences its language. Anthropologists need to learn the language of the culture they are studying in order to understand the world view of its speakers. Whorf believed that the reverse is also true, that a language affects culture as well, by actually influencing how its speakers think. His hypothesis proposes that the words and the structures of a language influence how its speakers think about the world, how they behave, and ultimately the culture itself. (See our definition of culture in Part 1 of this document.) Simply stated, Whorf believed that human beings see the world the way they do because the specific languages they speak influence them to do so.

He developed this idea through both his work with Sapir and his work as a chemical engineer for the Hartford Insurance Company investigating the causes of fires. One of his cases while working for the insurance company was a fire at a business where there were a number of gasoline drums. Those that contained gasoline were surrounded by signs warning employees to be cautious around them and to avoid smoking near them. The workers were always careful around those drums. On the other hand, empty gasoline drums were stored in another area, but employees were more careless there. Someone tossed a cigarette or lighted match into one of the “empty” drums, it went up in flames, and started a fire that burned the business to the ground. Whorf theorized that the meaning of the word empty implied to the worker that “nothing” was there to be cautious about so the worker behaved accordingly. Unfortunately, an “empty” gasoline drum may still contain fumes, which are more flammable than the liquid itself.

Whorf ’s studies at Yale involved working with Native American languages, including Hopi. The Hopi language is quite different from English, in many ways. For example, let’s look at how the Hopi language deals with time. Western languages (and cultures) view time as a flowing river in which we are being carried continuously away from a past, through the present, and into a future. Our verb systems reflect that concept with specific tenses for past, present, and future. We think of this concept of time as universal, that all humans see it the same way. A Hopi speaker has very different ideas and the structure of their language both reflects and shapes the way they think about time. The Hopi language has no present, past, or future tense. Instead, it divides the world into what Whorf called the manifested and unmanifest domains. The manifested domain deals with the physical universe, including the present, the immediate past and future; the verb system uses the same basic structure for all of them. The unmanifest domain involves the remote past and the future, as well as the world of desires, thought, and life forces. The set of verb forms dealing with this domain are consistent for all of these areas, and are different from the manifested ones. Also, there are no words for hours, minutes, or days of the week. Native Hopi speakers often had great difficulty adapting to life in the English speaking world when it came to being “on time” for work or other events. It is simply not how they had been conditioned to behave with respect to time in their Hopi world, which followed the phases of the moon and the movements of the sun.

In a book about the Abenaki who lived in Vermont in the mid-1800s, Trudy Ann Parker described their concept of time, which very much resembled that of the Hopi and many of the other Native American tribes. “They called one full day a sleep, and a year was called a winter. Each month was referred to as a moon and always began with a new moon. An Indian day wasn’t divided into minutes or hours. It had four time periods—sunrise, noon, sunset, and midnight. Each season was determined by the budding or leafing of plants, the spawning of fish, or the rutting time for animals. Most Indians thought the white race had been running around like scared rabbits ever since the invention of the clock.”

The lexicon , or vocabulary, of a language is an inventory of the items a culture talks about and has categorized in order to make sense of the world and deal with it effectively. For example, modern life is dictated for many by the need to travel by some kind of vehicle—cars, trucks, SUVs, trains, buses, etc. We therefore have thousands of words to talk about them, including types of vehicles, models, brands, or parts.

The most important aspects of each culture are similarly reflected in the lexicon of its language. Among the societies living in the islands of Oceania in the Pacific, fish have great economic and cultural importance. This is reflected in the rich vocabulary that describes all aspects of the fish and the environments that islanders depend on for survival. For example, in Palau there are about 1,000 fish species and Palauan fishermen knew, long before biologists existed, details about the anatomy, behavior, growth patterns, and habitat of most of them—in many cases far more than modern biologists know even today. Much of fish behavior is related to the tides and the phases of the moon. Throughout Oceania, the names given to certain days of the lunar months reflect the likelihood of successful fishing. For example, in the Caroline Islands, the name for the night before the new moon is otolol , which means “to swarm.” The name indicates that the best fishing days cluster around the new moon. In Hawai`i and Tahiti two sets of days have names containing the particle `ole or `ore ; one occurs in the first quarter of the moon and the other in the third quarter. The same name is given to the prevailing wind during those phases. The words mean “nothing,” because those days were considered bad for fishing as well as planting.

Parts of Whorf ’s hypothesis, known as linguistic relativity , were controversial from the beginning, and still are among some linguists. Yet Whorf ’s ideas now form the basis for an entire sub-field of cultural anthropology: cognitive or psychological anthropology. A number of studies have been done that support Whorf ’s ideas. Linguist George Lakoff ’s work looks at the pervasive existence of metaphors in everyday speech that can be said to predispose a speaker’s world view and attitudes on a variety of human experiences. A metaphor is an expression in which one kind of thing is understood and experienced in terms of another entirely unrelated thing; the metaphors in a language can reveal aspects of the culture of its speakers. Take, for example, the concept of an argument. In logic and philosophy, an argument is a discussion involving differing points of view, or a debate. But the conceptual metaphor in American culture can be stated as ARGUMENT IS WAR. This metaphor is reflected in many expressions of the everyday language of American speakers: I won the argument. He shot down every point I made. They attacked every argument we made. Your point is right on target . I had a fight with my boyfriend last night. In other words, we use words appropriate for discussing war when we talk about arguments, which are certainly not real war. But we actually think of arguments as a verbal battle that often involve anger, and even violence, which then structures how we argue.

To illustrate that this concept of argument is not universal, Lakoff suggests imagining a culture where an argument is not something to be won or lost, with no strategies for attacking or defending, but rather as a dance where the dancers’ goal is to perform in an artful, pleasing way. No anger or violence would occur or even be relevant to speakers of this language, because the metaphor for that culture would be ARGUMENT IS DANCE.

3.1 Adapted from Perspectives , Language ( Linda Light, 2017 )

You can either watch the video, How Language Shapes the Way We Think, by linguist Lera Boroditsky, or read the script below.

Watch the video: How Language Shapes the Way We Think ( Boroditsky, 2018)

There are about 7,000 languages spoken around the world—and they all have different sounds, vocabularies, and structures. But do they shape the way we think? Cognitive scientist Lera Boroditsky shares examples of language—from an Aboriginal community in Australia that uses cardinal directions instead of left and right to the multiple words for blue in Russian—that suggest the answer is a resounding yes. “The beauty of linguistic diversity is that it reveals to us just how ingenious and how flexible the human mind is,” Boroditsky says. “Human minds have invented not one cognitive universe, but 7,000.”

Video transcript:

So, I’ll be speaking to you using language ... because I can. This is one these magical abilities that we humans have. We can transmit really complicated thoughts to one another. So what I’m doing right now is, I’m making sounds with my mouth as I’m exhaling. I’m making tones and hisses and puffs, and those are creating air vibrations in the air. Those air vibrations are traveling to you, they’re hitting your eardrums, and then your brain takes those vibrations from your eardrums and transforms them into thoughts. I hope.

I hope that’s happening. So because of this ability, we humans are able to transmit our ideas across vast reaches of space and time. We’re able to transmit knowledge across minds. I can put a bizarre new idea in your mind right now. I could say, “Imagine a jellyfish waltzing in a library while thinking about quantum mechanics.”

Now, if everything has gone relatively well in your life so far, you probably haven’t had that thought before.

But now I’ve just made you think it, through language.

Now of course, there isn’t just one language in the world, there are about 7,000 languages spoken around the world. And all the languages differ from one another in all kinds of ways. Some languages have different sounds, they have different vocabularies, and they also have different structures—very importantly, different structures. That begs the question: Does the language we speak shape the way we think? Now, this is an ancient question. People have been speculating about this question forever. Charlemagne, Holy Roman emperor, said, “To have a second language is to have a second soul”—strong statement that language crafts reality. But on the other hand, Shakespeare has Juliet say, “What’s in a name? A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” Well, that suggests that maybe language doesn’t craft reality.

These arguments have gone back and forth for thousands of years. But until recently, there hasn’t been any data to help us decide either way. Recently, in my lab and other labs around the world, we’ve started doing research, and now we have actual scientific data to weigh in on this question.

So let me tell you about some of my favorite examples. I’ll start with an example from an Aboriginal community in Australia that I had a chance to work with. These are the Kuuk Thaayorre people. They live in Pormpuraaw at the very west edge of Cape York. What’s cool about Kuuk Thaayorre is, in Kuuk Thaayorre, they don’t use words like “left” and “right,” and instead, everything is in cardinal directions: north, south, east, and west. And when I say everything, I really mean everything. You would say something like, “Oh, there’s an ant on your southwest leg.” Or, “Move your cup to the north-northeast a little bit.” In fact, the way that you say “hello” in Kuuk Thaayorre is you say, “Which way are you going?” And the answer should be, “North-northeast in the far distance. How about you?”

So imagine as you’re walking around your day, every person you greet, you have to report your heading direction.

But that would actually get you oriented pretty fast, right? Because you literally couldn’t get past “hello,” if you didn’t know which way you were going. In fact, people who speak languages like this stay oriented really well. They stay oriented better than we used to think humans could. We used to think that humans were worse than other creatures because of some biological excuse: “Oh, we don’t have magnets in our beaks or in our scales.” No; if your language and your culture trains you to do it, actually, you can do it. There are humans around the world who stay oriented really well.

And just to get us in agreement about how different this is from the way we do it, I want you all to close your eyes for a second and point southeast.

Keep your eyes closed. Point. OK, so you can open your eyes. I see you guys pointing there, there, there, there, there ... I don’t know which way it is myself—

You have not been a lot of help.

So let’s just say the accuracy in this room was not very high. This is a big difference in cognitive ability across languages, right? Where one group—very distinguished group like you guys—doesn’t know which way is which, but in another group, I could ask a five-year-old and they would know.

There are also really big differences in how people think about time. So here I have pictures of my grandfather at different ages. And if I ask an English speaker to organize time, they might lay it out this way, from left to right. This has to do with writing direction. If you were a speaker of Hebrew or Arabic, you might do it going in the opposite direction, from right to left.

But how would the Kuuk Thaayorre, this Aboriginal group I just told you about, do it? They don’t use words like “left” and “right.” Let me give you hint. When we sat people facing south, they organized time from left to right. When we sat them facing north, they organized time from right to left. When we sat them facing east, time came towards the body. What’s the pattern? East to west, right? So for them, time doesn’t actually get locked on the body at all, it gets locked on the landscape. So for me, if I’m facing this way, then time goes this way, and if I’m facing this way, then time goes this way. I’m facing this way, time goes this way— very egocentric of me to have the direction of time chase me around every time I turn my body. For the Kuuk Thaayorre, time is locked on the landscape. It’s a dramatically different way of thinking about time.

Here’s another really smart human trait. Suppose I ask you how many penguins are there. Well, I bet I know how you’d solve that problem if you solved it. You went, “One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight.” You counted them. You named each one with a number, and the last number you said was the number of penguins. This is a little trick that you’re taught to use as kids. You learn the number list and you learn how to apply it. A little linguistic trick. Well, some languages don’t do this, because some languages don’t have exact number words. They’re languages that don’t have a word like “seven” or a word like “eight.” In fact, people who speak these languages don’t count, and they have trouble keeping track of exact quantities. So, for example, if I ask you to match this number of penguins to the same number of ducks, you would be able to do that by counting. But folks who don’t have that linguistic trait can’t do that.