- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

What is the Purpose of a Literature Review?

4-minute read

- 23rd October 2023

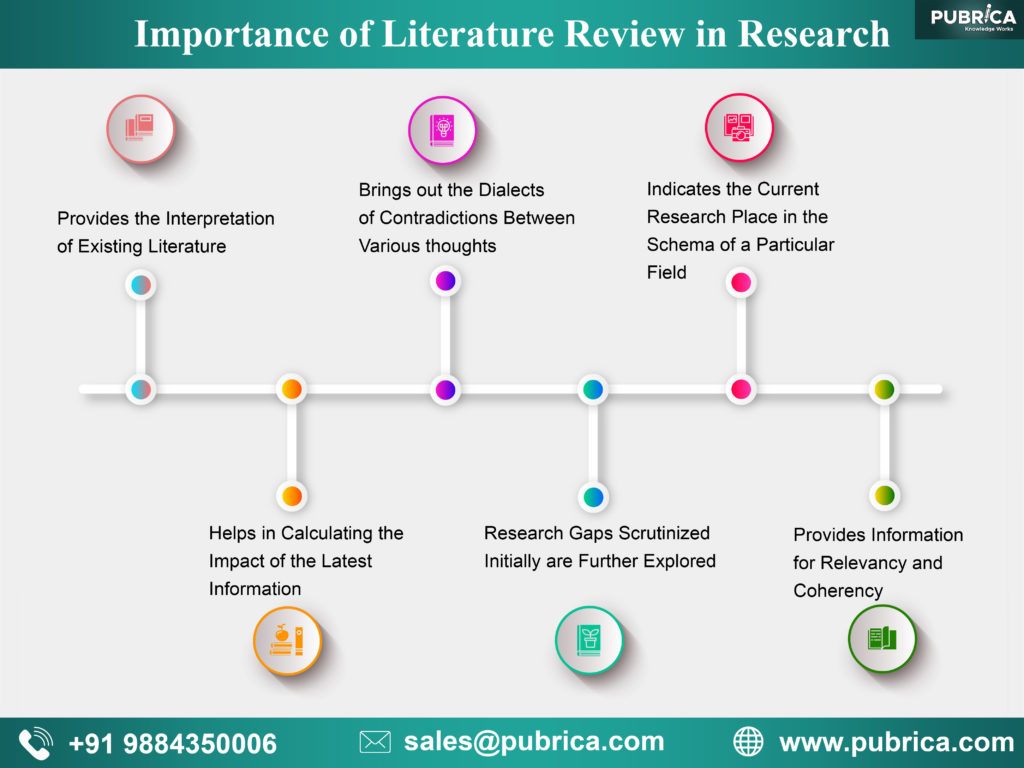

If you’re writing a research paper or dissertation , then you’ll most likely need to include a comprehensive literature review . In this post, we’ll review the purpose of literature reviews, why they are so significant, and the specific elements to include in one. Literature reviews can:

1. Provide a foundation for current research.

2. Define key concepts and theories.

3. Demonstrate critical evaluation.

4. Show how research and methodologies have evolved.

5. Identify gaps in existing research.

6. Support your argument.

Keep reading to enter the exciting world of literature reviews!

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review is a critical summary and evaluation of the existing research (e.g., academic journal articles and books) on a specific topic. It is typically included as a separate section or chapter of a research paper or dissertation, serving as a contextual framework for a study. Literature reviews can vary in length depending on the subject and nature of the study, with most being about equal length to other sections or chapters included in the paper. Essentially, the literature review highlights previous studies in the context of your research and summarizes your insights in a structured, organized format. Next, let’s look at the overall purpose of a literature review.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Literature reviews are considered an integral part of research across most academic subjects and fields. The primary purpose of a literature review in your study is to:

Provide a Foundation for Current Research

Since the literature review provides a comprehensive evaluation of the existing research, it serves as a solid foundation for your current study. It’s a way to contextualize your work and show how your research fits into the broader landscape of your specific area of study.

Define Key Concepts and Theories

The literature review highlights the central theories and concepts that have arisen from previous research on your chosen topic. It gives your readers a more thorough understanding of the background of your study and why your research is particularly significant .

Demonstrate Critical Evaluation

A comprehensive literature review shows your ability to critically analyze and evaluate a broad range of source material. And since you’re considering and acknowledging the contribution of key scholars alongside your own, it establishes your own credibility and knowledge.

Show How Research and Methodologies Have Evolved

Another purpose of literature reviews is to provide a historical perspective and demonstrate how research and methodologies have changed over time, especially as data collection methods and technology have advanced. And studying past methodologies allows you, as the researcher, to understand what did and did not work and apply that knowledge to your own research.

Identify Gaps in Existing Research

Besides discussing current research and methodologies, the literature review should also address areas that are lacking in the existing literature. This helps further demonstrate the relevance of your own research by explaining why your study is necessary to fill the gaps.

Support Your Argument

A good literature review should provide evidence that supports your research questions and hypothesis. For example, your study may show that your research supports existing theories or builds on them in some way. Referencing previous related studies shows your work is grounded in established research and will ultimately be a contribution to the field.

Literature Review Editing Services

Ensure your literature review is polished and ready for submission by having it professionally proofread and edited by our expert team. Our literature review editing services will help your research stand out and make an impact. Not convinced yet? Send in your free sample today and see for yourself!

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Conducting a literature review: why do a literature review, why do a literature review.

- How To Find "The Literature"

- Found it -- Now What?

Besides the obvious reason for students -- because it is assigned! -- a literature review helps you explore the research that has come before you, to see how your research question has (or has not) already been addressed.

You identify:

- core research in the field

- experts in the subject area

- methodology you may want to use (or avoid)

- gaps in knowledge -- or where your research would fit in

It Also Helps You:

- Publish and share your findings

- Justify requests for grants and other funding

- Identify best practices to inform practice

- Set wider context for a program evaluation

- Compile information to support community organizing

Great brief overview, from NCSU

Want To Know More?

- Next: How To Find "The Literature" >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 1:10 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/litreview

- Library Homepage

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide: Literature Reviews?

- Literature Reviews?

- Strategies to Finding Sources

- Keeping up with Research!

- Evaluating Sources & Literature Reviews

- Organizing for Writing

- Writing Literature Review

- Other Academic Writings

What is a Literature Review?

So, what is a literature review .

"A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available or a set of summaries." - Quote from Taylor, D. (n.d)."The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting it".

- Citation: "The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting it"

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Each field has a particular way to do reviews for academic research literature. In the social sciences and humanities the most common are:

- Narrative Reviews: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific research topic and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weaknesses, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section that summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Book review essays/ Historiographical review essays : A type of literature review typical in History and related fields, e.g., Latin American studies. For example, the Latin American Research Review explains that the purpose of this type of review is to “(1) to familiarize readers with the subject, approach, arguments, and conclusions found in a group of books whose common focus is a historical period; a country or region within Latin America; or a practice, development, or issue of interest to specialists and others; (2) to locate these books within current scholarship, critical methodologies, and approaches; and (3) to probe the relation of these new books to previous work on the subject, especially canonical texts. Unlike individual book reviews, the cluster reviews found in LARR seek to address the state of the field or discipline and not solely the works at issue.” - LARR

What are the Goals of Creating a Literature Review?

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

- Baumeister, R.F. & Leary, M.R. (1997). "Writing narrative literature reviews," Review of General Psychology , 1(3), 311-320.

When do you need to write a Literature Review?

- When writing a prospectus or a thesis/dissertation

- When writing a research paper

- When writing a grant proposal

In all these cases you need to dedicate a chapter in these works to showcase what has been written about your research topic and to point out how your own research will shed new light into a body of scholarship.

Where I can find examples of Literature Reviews?

Note: In the humanities, even if they don't use the term "literature review", they may have a dedicated chapter that reviewed the "critical bibliography" or they incorporated that review in the introduction or first chapter of the dissertation, book, or article.

- UCSB electronic theses and dissertations In partnership with the Graduate Division, the UC Santa Barbara Library is making available theses and dissertations produced by UCSB students. Currently included in ADRL are theses and dissertations that were originally filed electronically, starting in 2011. In future phases of ADRL, all theses and dissertations created by UCSB students may be digitized and made available.

Where to Find Standalone Literature Reviews

Literature reviews are also written as standalone articles as a way to survey a particular research topic in-depth. This type of literature review looks at a topic from a historical perspective to see how the understanding of the topic has changed over time.

- Find e-Journals for Standalone Literature Reviews The best way to get familiar with and to learn how to write literature reviews is by reading them. You can use our Journal Search option to find journals that specialize in publishing literature reviews from major disciplines like anthropology, sociology, etc. Usually these titles are called, "Annual Review of [discipline name] OR [Discipline name] Review. This option works best if you know the title of the publication you are looking for. Below are some examples of these journals! more... less... Journal Search can be found by hovering over the link for Research on the library website.

Social Sciences

- Annual Review of Anthropology

- Annual Review of Political Science

- Annual Review of Sociology

- Ethnic Studies Review

Hard science and health sciences:

- Annual Review of Biomedical Data Science

- Annual Review of Materials Science

- Systematic Review From journal site: "The journal Systematic Reviews encompasses all aspects of the design, conduct, and reporting of systematic reviews" in the health sciences.

- << Previous: Overview

- Next: Strategies to Finding Sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 5, 2024 11:44 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucsb.edu/litreview

What Is A Literature Review?

A plain-language explainer (with examples).

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) & Kerryn Warren (PhD) | June 2020 (Updated May 2023)

If you’re faced with writing a dissertation or thesis, chances are you’ve encountered the term “literature review” . If you’re on this page, you’re probably not 100% what the literature review is all about. The good news is that you’ve come to the right place.

Literature Review 101

- What (exactly) is a literature review

- What’s the purpose of the literature review chapter

- How to find high-quality resources

- How to structure your literature review chapter

- Example of an actual literature review

What is a literature review?

The word “literature review” can refer to two related things that are part of the broader literature review process. The first is the task of reviewing the literature – i.e. sourcing and reading through the existing research relating to your research topic. The second is the actual chapter that you write up in your dissertation, thesis or research project. Let’s look at each of them:

Reviewing the literature

The first step of any literature review is to hunt down and read through the existing research that’s relevant to your research topic. To do this, you’ll use a combination of tools (we’ll discuss some of these later) to find journal articles, books, ebooks, research reports, dissertations, theses and any other credible sources of information that relate to your topic. You’ll then summarise and catalogue these for easy reference when you write up your literature review chapter.

The literature review chapter

The second step of the literature review is to write the actual literature review chapter (this is usually the second chapter in a typical dissertation or thesis structure ). At the simplest level, the literature review chapter is an overview of the key literature that’s relevant to your research topic. This chapter should provide a smooth-flowing discussion of what research has already been done, what is known, what is unknown and what is contested in relation to your research topic. So, you can think of it as an integrated review of the state of knowledge around your research topic.

What’s the purpose of a literature review?

The literature review chapter has a few important functions within your dissertation, thesis or research project. Let’s take a look at these:

Purpose #1 – Demonstrate your topic knowledge

The first function of the literature review chapter is, quite simply, to show the reader (or marker) that you know what you’re talking about . In other words, a good literature review chapter demonstrates that you’ve read the relevant existing research and understand what’s going on – who’s said what, what’s agreed upon, disagreed upon and so on. This needs to be more than just a summary of who said what – it needs to integrate the existing research to show how it all fits together and what’s missing (which leads us to purpose #2, next).

Purpose #2 – Reveal the research gap that you’ll fill

The second function of the literature review chapter is to show what’s currently missing from the existing research, to lay the foundation for your own research topic. In other words, your literature review chapter needs to show that there are currently “missing pieces” in terms of the bigger puzzle, and that your study will fill one of those research gaps . By doing this, you are showing that your research topic is original and will help contribute to the body of knowledge. In other words, the literature review helps justify your research topic.

Purpose #3 – Lay the foundation for your conceptual framework

The third function of the literature review is to form the basis for a conceptual framework . Not every research topic will necessarily have a conceptual framework, but if your topic does require one, it needs to be rooted in your literature review.

For example, let’s say your research aims to identify the drivers of a certain outcome – the factors which contribute to burnout in office workers. In this case, you’d likely develop a conceptual framework which details the potential factors (e.g. long hours, excessive stress, etc), as well as the outcome (burnout). Those factors would need to emerge from the literature review chapter – they can’t just come from your gut!

So, in this case, the literature review chapter would uncover each of the potential factors (based on previous studies about burnout), which would then be modelled into a framework.

Purpose #4 – To inform your methodology

The fourth function of the literature review is to inform the choice of methodology for your own research. As we’ve discussed on the Grad Coach blog , your choice of methodology will be heavily influenced by your research aims, objectives and questions . Given that you’ll be reviewing studies covering a topic close to yours, it makes sense that you could learn a lot from their (well-considered) methodologies.

So, when you’re reviewing the literature, you’ll need to pay close attention to the research design , methodology and methods used in similar studies, and use these to inform your methodology. Quite often, you’ll be able to “borrow” from previous studies . This is especially true for quantitative studies , as you can use previously tried and tested measures and scales.

How do I find articles for my literature review?

Finding quality journal articles is essential to crafting a rock-solid literature review. As you probably already know, not all research is created equally, and so you need to make sure that your literature review is built on credible research .

We could write an entire post on how to find quality literature (actually, we have ), but a good starting point is Google Scholar . Google Scholar is essentially the academic equivalent of Google, using Google’s powerful search capabilities to find relevant journal articles and reports. It certainly doesn’t cover every possible resource, but it’s a very useful way to get started on your literature review journey, as it will very quickly give you a good indication of what the most popular pieces of research are in your field.

One downside of Google Scholar is that it’s merely a search engine – that is, it lists the articles, but oftentimes it doesn’t host the articles . So you’ll often hit a paywall when clicking through to journal websites.

Thankfully, your university should provide you with access to their library, so you can find the article titles using Google Scholar and then search for them by name in your university’s online library. Your university may also provide you with access to ResearchGate , which is another great source for existing research.

Remember, the correct search keywords will be super important to get the right information from the start. So, pay close attention to the keywords used in the journal articles you read and use those keywords to search for more articles. If you can’t find a spoon in the kitchen, you haven’t looked in the right drawer.

Need a helping hand?

How should I structure my literature review?

Unfortunately, there’s no generic universal answer for this one. The structure of your literature review will depend largely on your topic area and your research aims and objectives.

You could potentially structure your literature review chapter according to theme, group, variables , chronologically or per concepts in your field of research. We explain the main approaches to structuring your literature review here . You can also download a copy of our free literature review template to help you establish an initial structure.

In general, it’s also a good idea to start wide (i.e. the big-picture-level) and then narrow down, ending your literature review close to your research questions . However, there’s no universal one “right way” to structure your literature review. The most important thing is not to discuss your sources one after the other like a list – as we touched on earlier, your literature review needs to synthesise the research , not summarise it .

Ultimately, you need to craft your literature review so that it conveys the most important information effectively – it needs to tell a logical story in a digestible way. It’s no use starting off with highly technical terms and then only explaining what these terms mean later. Always assume your reader is not a subject matter expert and hold their hand through a journe y of the literature while keeping the functions of the literature review chapter (which we discussed earlier) front of mind.

Example of a literature review

In the video below, we walk you through a high-quality literature review from a dissertation that earned full distinction. This will give you a clearer view of what a strong literature review looks like in practice and hopefully provide some inspiration for your own.

Wrapping Up

In this post, we’ve (hopefully) answered the question, “ what is a literature review? “. We’ve also considered the purpose and functions of the literature review, as well as how to find literature and how to structure the literature review chapter. If you’re keen to learn more, check out the literature review section of the Grad Coach blog , as well as our detailed video post covering how to write a literature review .

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

16 Comments

Thanks for this review. It narrates what’s not been taught as tutors are always in a early to finish their classes.

Thanks for the kind words, Becky. Good luck with your literature review 🙂

This website is amazing, it really helps break everything down. Thank you, I would have been lost without it.

This is review is amazing. I benefited from it a lot and hope others visiting this website will benefit too.

Timothy T. Chol [email protected]

Thank you very much for the guiding in literature review I learn and benefited a lot this make my journey smooth I’ll recommend this site to my friends

This was so useful. Thank you so much.

Hi, Concept was explained nicely by both of you. Thanks a lot for sharing it. It will surely help research scholars to start their Research Journey.

The review is really helpful to me especially during this period of covid-19 pandemic when most universities in my country only offer online classes. Great stuff

Great Brief Explanation, thanks

So helpful to me as a student

GradCoach is a fantastic site with brilliant and modern minds behind it.. I spent weeks decoding the substantial academic Jargon and grounding my initial steps on the research process, which could be shortened to a couple of days through the Gradcoach. Thanks again!

This is an amazing talk. I paved way for myself as a researcher. Thank you GradCoach!

Well-presented overview of the literature!

This was brilliant. So clear. Thank you

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can use boolean operators to help narrow down your search:

Read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

To identify the most important publications on your topic, take note of recurring citations. If the same authors, books or articles keep appearing in your reading, make sure to seek them out.

You probably won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on the topic – you’ll have to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your questions.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models and methods? Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- How does the publication contribute to your understanding of the topic? What are its key insights and arguments?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible, and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can find out how many times an article has been cited on Google Scholar – a high citation count means the article has been influential in the field, and should certainly be included in your literature review.

The scope of your review will depend on your topic and discipline: in the sciences you usually only review recent literature, but in the humanities you might take a long historical perspective (for example, to trace how a concept has changed in meaning over time).

Remember that you can use our template to summarise and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using!

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It’s important to keep track of your sources with references to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography, where you compile full reference information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

You can use our free APA Reference Generator for quick, correct, consistent citations.

To begin organising your literature review’s argument and structure, you need to understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly-visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat – this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organising the body of a literature review. You should have a rough idea of your strategy before you start writing.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarising sources in order.

Try to analyse patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organise your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text, your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

If you are writing the literature review as part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate your central problem or research question and give a brief summary of the scholarly context. You can emphasise the timeliness of the topic (“many recent studies have focused on the problem of x”) or highlight a gap in the literature (“while there has been much research on x, few researchers have taken y into consideration”).

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, make sure to follow these tips:

- Summarise and synthesise: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole.

- Analyse and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole.

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources.

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transitions and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts.

In the conclusion, you should summarise the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasise their significance.

If the literature review is part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate how your research addresses gaps and contributes new knowledge, or discuss how you have drawn on existing theories and methods to build a framework for your research. This can lead directly into your methodology section.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, June 07). What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 21 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

Brazil’s plummeting graduate enrolments hint at declining interest in academic science careers

Career News 21 MAY 24

How religious scientists balance work and faith

Career Feature 20 MAY 24

How to set up your new lab space

Career Column 20 MAY 24

Guidelines for academics aim to lessen ethical pitfalls in generative-AI use

Nature Index 22 MAY 24

Pay researchers to spot errors in published papers

World View 21 MAY 24

Who will make AlphaFold3 open source? Scientists race to crack AI model

News 23 MAY 24

Egypt is building a $1-billion mega-museum. Will it bring Egyptology home?

News Feature 22 MAY 24

Full Professorship (W3) in “Organic Environmental Geochemistry (f/m/d)

The Institute of Earth Sciences within the Faculty of Chemistry and Earth Sciences at Heidelberg University invites applications for a FULL PROFE...

Heidelberg, Brandenburg (DE)

Universität Heidelberg

Postdoc: deep learning for super-resolution microscopy

The Ries lab is looking for a PostDoc with background in machine learning.

Vienna, Austria

University of Vienna

Postdoc: development of a novel MINFLUX microscope

The Ries lab is developing super-resolution microscopy methods for structural cell biology. In this project we will develop a fast, simple, and robust

Postdoctoral scholarship in Structural biology of neurodegeneration

A 2-year fellowship in multidisciplinary project combining molecular, structural and cell biology approaches to understand neurodegenerative disease

Umeå, Sweden

Umeå University

Group Leader (Microbes and Food Safety)

Full or Part Time We are looking for a dynamic, proactive individual to lead a research programme contributing to our goals of reducing foodborne i...

Norwich, Norfolk

Quadram Institute Bioscience

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Libraries | Research Guides

Literature reviews, what is a literature review, learning more about how to do a literature review.

- Planning the Review

- The Research Question

- Choosing Where to Search

- Organizing the Review

- Writing the Review

A literature review is a review and synthesis of existing research on a topic or research question. A literature review is meant to analyze the scholarly literature, make connections across writings and identify strengths, weaknesses, trends, and missing conversations. A literature review should address different aspects of a topic as it relates to your research question. A literature review goes beyond a description or summary of the literature you have read.

- Sage Research Methods Core Collection This link opens in a new window SAGE Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. SAGE Research Methods is the ultimate methods library with more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher. – Publisher

- Next: Planning the Review >>

- Last Updated: May 2, 2024 10:39 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/literaturereviews

- Research Process

Literature Review in Research Writing

- 4 minute read

- 424.4K views

Table of Contents

Research on research? If you find this idea rather peculiar, know that nowadays, with the huge amount of information produced daily all around the world, it is becoming more and more difficult to keep up to date with all of it. In addition to the sheer amount of research, there is also its origin. We are witnessing the economic and intellectual emergence of countries like China, Brazil, Turkey, and United Arab Emirates, for example, that are producing scholarly literature in their own languages. So, apart from the effort of gathering information, there must also be translators prepared to unify all of it in a single language to be the object of the literature survey. At Elsevier, our team of translators is ready to support researchers by delivering high-quality scientific translations , in several languages, to serve their research – no matter the topic.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a study – or, more accurately, a survey – involving scholarly material, with the aim to discuss published information about a specific topic or research question. Therefore, to write a literature review, it is compulsory that you are a real expert in the object of study. The results and findings will be published and made available to the public, namely scientists working in the same area of research.

How to Write a Literature Review

First of all, don’t forget that writing a literature review is a great responsibility. It’s a document that is expected to be highly reliable, especially concerning its sources and findings. You have to feel intellectually comfortable in the area of study and highly proficient in the target language; misconceptions and errors do not have a place in a document as important as a literature review. In fact, you might want to consider text editing services, like those offered at Elsevier, to make sure your literature is following the highest standards of text quality. You want to make sure your literature review is memorable by its novelty and quality rather than language errors.

Writing a literature review requires expertise but also organization. We cannot teach you about your topic of research, but we can provide a few steps to guide you through conducting a literature review:

- Choose your topic or research question: It should not be too comprehensive or too limited. You have to complete your task within a feasible time frame.

- Set the scope: Define boundaries concerning the number of sources, time frame to be covered, geographical area, etc.

- Decide which databases you will use for your searches: In order to search the best viable sources for your literature review, use highly regarded, comprehensive databases to get a big picture of the literature related to your topic.

- Search, search, and search: Now you’ll start to investigate the research on your topic. It’s critical that you keep track of all the sources. Start by looking at research abstracts in detail to see if their respective studies relate to or are useful for your own work. Next, search for bibliographies and references that can help you broaden your list of resources. Choose the most relevant literature and remember to keep notes of their bibliographic references to be used later on.

- Review all the literature, appraising carefully it’s content: After reading the study’s abstract, pay attention to the rest of the content of the articles you deem the “most relevant.” Identify methodologies, the most important questions they address, if they are well-designed and executed, and if they are cited enough, etc.

If it’s the first time you’ve published a literature review, note that it is important to follow a special structure. Just like in a thesis, for example, it is expected that you have an introduction – giving the general idea of the central topic and organizational pattern – a body – which contains the actual discussion of the sources – and finally the conclusion or recommendations – where you bring forward whatever you have drawn from the reviewed literature. The conclusion may even suggest there are no agreeable findings and that the discussion should be continued.

Why are literature reviews important?

Literature reviews constantly feed new research, that constantly feeds literature reviews…and we could go on and on. The fact is, one acts like a force over the other and this is what makes science, as a global discipline, constantly develop and evolve. As a scientist, writing a literature review can be very beneficial to your career, and set you apart from the expert elite in your field of interest. But it also can be an overwhelming task, so don’t hesitate in contacting Elsevier for text editing services, either for profound edition or just a last revision. We guarantee the very highest standards. You can also save time by letting us suggest and make the necessary amendments to your manuscript, so that it fits the structural pattern of a literature review. Who knows how many worldwide researchers you will impact with your next perfectly written literature review.

Know more: How to Find a Gap in Research .

Language Editing Services by Elsevier Author Services:

What is a Research Gap

- Manuscript Preparation

Types of Scientific Articles

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Writing a good review article

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Literature Reviews

- Getting started

What is a literature review?

Why conduct a literature review, stages of a literature review, lit reviews: an overview (video), check out these books.

- Types of reviews

- 1. Define your research question

- 2. Plan your search

- 3. Search the literature

- 4. Organize your results

- 5. Synthesize your findings

- 6. Write the review

- Artificial intelligence (AI) tools

- Thompson Writing Studio This link opens in a new window

- Need to write a systematic review? This link opens in a new window

Contact a Librarian

Ask a Librarian

Definition: A literature review is a systematic examination and synthesis of existing scholarly research on a specific topic or subject.

Purpose: It serves to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of knowledge within a particular field.

Analysis: Involves critically evaluating and summarizing key findings, methodologies, and debates found in academic literature.

Identifying Gaps: Aims to pinpoint areas where there is a lack of research or unresolved questions, highlighting opportunities for further investigation.

Contextualization: Enables researchers to understand how their work fits into the broader academic conversation and contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

tl;dr A literature review critically examines and synthesizes existing scholarly research and publications on a specific topic to provide a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge in the field.

What is a literature review NOT?

❌ An annotated bibliography

❌ Original research

❌ A summary

❌ Something to be conducted at the end of your research

❌ An opinion piece

❌ A chronological compilation of studies

The reason for conducting a literature review is to:

Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students

While this 9-minute video from NCSU is geared toward graduate students, it is useful for anyone conducting a literature review.

Writing the literature review: A practical guide

Available 3rd floor of Perkins

Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences

Available online!

So, you have to write a literature review: A guided workbook for engineers

Telling a research story: Writing a literature review

The literature review: Six steps to success

Systematic approaches to a successful literature review

Request from Duke Medical Center Library

Doing a systematic review: A student's guide

- Next: Types of reviews >>

- Last Updated: May 17, 2024 8:42 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.duke.edu/litreviews

Services for...

- Faculty & Instructors

- Graduate Students

- Undergraduate Students

- International Students

- Patrons with Disabilities

- Harmful Language Statement

- Re-use & Attribution / Privacy

- Support the Libraries

- Become Involved |

- Give to the Library |

- Staff Directory |

- UNF Library

- Thomas G. Carpenter Library

Conducting a Literature Review

Benefits of conducting a literature review.

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Summary of the Process

- Additional Resources

- Literature Review Tutorial by American University Library

- The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It by University of Toronto

- Write a Literature Review by UC Santa Cruz University Library

While there might be many reasons for conducting a literature review, following are four key outcomes of doing the review.

Assessment of the current state of research on a topic . This is probably the most obvious value of the literature review. Once a researcher has determined an area to work with for a research project, a search of relevant information sources will help determine what is already known about the topic and how extensively the topic has already been researched.

Identification of the experts on a particular topic . One of the additional benefits derived from doing the literature review is that it will quickly reveal which researchers have written the most on a particular topic and are, therefore, probably the experts on the topic. Someone who has written twenty articles on a topic or on related topics is more than likely more knowledgeable than someone who has written a single article. This same writer will likely turn up as a reference in most of the other articles written on the same topic. From the number of articles written by the author and the number of times the writer has been cited by other authors, a researcher will be able to assume that the particular author is an expert in the area and, thus, a key resource for consultation in the current research to be undertaken.

Identification of key questions about a topic that need further research . In many cases a researcher may discover new angles that need further exploration by reviewing what has already been written on a topic. For example, research may suggest that listening to music while studying might lead to better retention of ideas, but the research might not have assessed whether a particular style of music is more beneficial than another. A researcher who is interested in pursuing this topic would then do well to follow up existing studies with a new study, based on previous research, that tries to identify which styles of music are most beneficial to retention.

Determination of methodologies used in past studies of the same or similar topics. It is often useful to review the types of studies that previous researchers have launched as a means of determining what approaches might be of most benefit in further developing a topic. By the same token, a review of previously conducted studies might lend itself to researchers determining a new angle for approaching research.

Upon completion of the literature review, a researcher should have a solid foundation of knowledge in the area and a good feel for the direction any new research should take. Should any additional questions arise during the course of the research, the researcher will know which experts to consult in order to quickly clear up those questions.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2022 8:54 AM

- URL: https://libguides.unf.edu/litreview

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 5. The Literature Review

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys prior research published in books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have used in researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within existing scholarship about the topic.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014.

Importance of a Good Literature Review

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in the social sciences, a literature review usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

Given this, the purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011; Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Doing a Literature Review." PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (January 2006): 127-132; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012.

Types of Literature Reviews

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally among scholars that become part of the body of epistemological traditions within the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

NOTE : Most often the literature review will incorporate some combination of types. For example, a review that examines literature supporting or refuting an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem related to the research problem will also need to include writing supported by sources that establish the history of these arguments in the literature.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Thinking About Your Literature Review

The structure of a literature review should include the following in support of understanding the research problem :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Validity -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Basic Stages of Writing 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.