Services & Products

- Calculate your carbon emissions Offset your carbon emissions

Sweet solutions: the role of bees and Impact Investments in environmental restoration

A pathway to sustainability for uk enterprises, the vital role of reforestation in bird migration, become shareholder, sustainable investments.

- Become a DGB shareholder Invest in our projects

Nature-based solutions

Stakeholders, how it works, project updates, greenzone reforestation project: big steps in cameroon, dgb’s hongera reforestation project: 600 hectares and growing, final validation received for bulindi chimpanzee habitat restoration project.

- Subscribe to our newsletter Download our favourite ebook

Latest Article

- Calculate carbon footprint Calculate environmental footprint CSRD reporting Case studies

- Carbon credits Biodiversity credits Plastic credits Tree planting for business

- DGB on the stock market Public company as a mission Investor relations

- Green bonds investment Impact investing Investing in carbon credits

- Our projects Updates from the projects Project pipeline

- Landowners and farmers Local communities Regulators and policymakers

- What is a carbon project? What we can do for your land How to start a carbon project

- Blog Newsroom Technology

- Events eBooks Podcasts

It looks like you’re browsing from Netherlands. Click here to switch to the Dutch →

Desertification - Sahel case study

- Share this article:

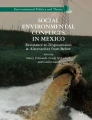

Desertification in the Sahel region is a pressing environmental issue with far-reaching consequences. In this article, we will explore the causes, effects, and potential solutions to combat desertification, using a case study from the Sahel region. By examining the unique challenges faced in this area, we can gain insights into the broader fight against desertification and the importance of sustainable land management practices. The Sahel is a semi-arid zone stretching from the Atlantic Ocean in West Africa to the Red Sea in the East, through northern Senegal, southern Mauritania, the great bend of the Niger River in Mali, Burkina Faso, southern Niger, northeastern Nigeria, south-central Chad, and into Sudan ( Brittanica ).

It is a biogeographical transition between the arid Sahara Desert to the North and the more humid savanna systems on its Southern side.

Desertification in the Sahel has increased over the last number of years. It has been increasingly impacted by desertification, especially during the second half of the twentieth century. The whole Sahel region in Africa has been affected by devastating droughts, bordering the Sahara Desert and the Savannas.

During this period, the Sahara desert area grew by roughly 10% , most of which in the Southward direction into the semi-arid steppes of the Sahel.

Understanding desertification in the Sahel

The Sahel region, stretching across Africa from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea, is characterized by fragile ecosystems and vulnerable communities. The combination of climate change, overgrazing, deforestation , and improper agricultural practices has resulted in extensive land degradation and desertification. The consequences of desertification in the Sahel are severe, including food insecurity, loss of biodiversity, and displacement of communities.

in the region, for around 8 months of the year, the weather is dry. The rainy season only happens for a few short months and only produces around 4-8 inches of water. The population growth over the years has caused illegal farming to take place over the last few years and has resulted in major soil erosion and desertification to take place.

Examining a specific case study in the Sahel region sheds light on the complexities and impacts of desertification. In a particular community, unsustainable farming methods and drought have led to soil erosion and degradation. The once-fertile land has turned into arid, unproductive soil, forcing farmers to abandon their livelihoods and seek alternative means of survival. This case study highlights the urgent need for intervention and sustainable land management practices in the region.

Addressing the challenges

To combat desertification effectively, a multi-faceted approach is necessary. First and foremost, raising awareness about the issue and its consequences is crucial. Governments, NGOs, and local communities must collaborate to implement sustainable land management practices. This involves promoting agroforestry, conservation farming, and reforestation initiatives to restore degraded land and improve soil health. Additionally, supporting alternative income-generating activities and providing access to water resources can help alleviate pressure on the land and reduce vulnerability to drought.

Read more: Preventing desertification: Top 5 success stories

The impact of humans on the Sahel

The impact of humans on the Sahel region is a critical factor contributing to its current challenges and environmental changes. Human activities, including armed violence, climate change, deforestation, and overgrazing, have had significant consequences for both the ecosystem and the local communities. While the area of the Sahel region is already considered to be a dry place, the impact of the human population in the area has really affected how the area continues to evolve. Towns are popping up all over the place, and because of this, more land is being used than ever before. The ground that they are building their lives on quickly began to die and became extremely unhealthy for any type of growth. This has made headlines everywhere and even caught the attention of the United Nations. In 1994, the United Nations declared that June 17th would be known as the World Day to Combat Desertification and Drought. . This was a result of the large-scale droughts and famines that had been taking place and were at their height between 1968 and 1974.

In conclusion, the impact of humans on the Sahel is a multifaceted issue. The region faces a humanitarian crisis alongside security concerns, with climate change and human activities playing significant roles. Desertification caused by climate change, deforestation, and overgrazing has resulted in land degradation, loss of vegetation, and increased vulnerability to droughts and food insecurity. Implementing sustainable land management strategies is essential to mitigate the impact and promote the resilience of the Sahel's ecosystems and communities.

Droughts, grazing, and recharging aquifers

The Sahel’s natural climate cycles make it vulnerable to droughts throughout the year. But, during the second half of the twentieth century, the region also experienced significant increases in human population and resulting in increases in the exploitation of the lands through (cattle) grazing, wood- and bush consumption for firewood, and crop growth where possible.

These anthropogenic processes accelerated during the 1960s when relatively high rainfall amounts were recorded in the region for short periods of time, and grazing and agricultural expansion were promoted by the governments of the Sahel countries, seeing a good opportunity to use the region’s ecosystem for maximizing economic returns.

This resulted in the removal of large parts of the natural vegetation, including shrubs, grasses, and trees, and replacing them with crops and grass types that were suitable for (short-term) grazing.

The world effort for the Sahel:

Natural aquifers, which were previously able to replenish their groundwater stocks during the natural climate cycles, were no longer able to do so, and the regions closest to the Sahara desert were increasingly desertified.

Removing the natural vegetation removed plant roots that bound the soil together, with over-exploitation by grazing eating away much of the grass.

Agricultural activity disrupted the natural system, forcing significant parts of the Sahel region to become dry and barren. Before the particularly bad famine of 1984, desertification was solely put down to climatic causes.

As the Sahel dries, the Sahara advances : and it is estimated to advance with a rate of 60 kilometres the Sahel lost and the Sahara desert gained per year. Human influence is an important factor in the Sahel’s desertification, but not all can be attributed to human behaviour, says Sumant Nigam, a climate scientist at the University of Maryland.

'There is an important anthropogenic influence there, but it is also being met with natural cycles of climate variability that add and subtract in different periods', Nigam said. 'Understanding both is important for both attribution and prediction.' Ecologists have been meeting all over the world to discuss the desertification of the Sahel at length. While many possible solutions have been proposed, a few goals have been established and are being worked on. The Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations has not become involved and is working to create a long-lasting impact on the Sahel Region. However, after the mid-1980s , human-caused contributions were identified and taken seriously by the United Nations and many non-governmental organizations. Severe and long-lasting droughts followed throughout the 1960s-1980s, and impacted the human settlements in the forms of famine and starvation, allowing the Sahara desert to continue to expand southward. As a result, a barren and waterless landscape has emerged, with the northernmost sections of the Sahel transformed into new sections of the Sahara Desert. Even though the levels of drought have decreased since the 1990s, other significant reductions in rainfall have been recorded in the region, including a severe drought in 2012. It is estimated that over 23 million people in the Sahel region are facing severe food insecurity in 2022, and the European Commission projects that the crisis will worsen further amidst rising social security struggles. Now, the goal is to see change take place by 2063, a year that seems far away but is a start in the efforts to rebuild the Sahel Region.

Before you go...

As DGB Group, our sole purpose is to rebuild trust and serve the public by making the right information available to everyone. By subscribing to our mailing newsletter, you can get the latest tips and trends from DGB Group's expert team in your inbox. Sign up now and never miss the insights.

Popular Topics

- Carbon offsetting (80)

- Sustainability (68)

- Biodiversity (57)

- Carbon credits (53)

- Carbon markets (49)

- Nature conservation (49)

- Net zero (40)

- Tree planting (40)

- Nature-based solutions (37)

- Carbon emissions (34)

Recommended

Desertification in africa and how desertification can affect people in africa, three desertification examples, preventing desertification: top 5 success stories, featured resource, the power of trees.

Read other articles

Did you know that worker bees can fly up to 8 kilometres a day, wearing out their wings after coveri..

As the global focus on reducing carbon emissions intensifies, many UK companies are stepping up thei..

Each year, millions of birds embark on one of nature’s most incredible phenomena: migration. These l..

Belgium’s leading firms in carbon compensation efforts

This week, we spotlight Belgium, a country home to several companies at the forefront of reducing th..

Let’s get to know you

Let's talk about how we can create value together for your sustainability journey.

Stay Updated

- Trees for Businesses

- Green Bonds

- Investor Portal Login

- ESG Reporting

- Carbon Footprint Analysis

- Carbon Footprint Calculator

- Carbon Credits

- Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive

- Plastic Credits

- Biodiversity Credits

- Monthly Tree Planting

- Carbon Projects for Landowners

- Board of Directors

- Investor Relations

- Investor Events

- Press Releases

- Annual Financial Reports

- Case Studies

- Agriculture

- Biodiversity

- Carbon Offsetting

- Carbon Pricing

- Clean Energy

- Deforestation

- Desertification

- Endangered Species

- Plastic Pollution

- Saving Water

- Sustainability

- Sustainable Development

- Vital Habitats

- Waste Management

- Corporate governance & policies

Case Study: Sahel Desertification

What is desertification: It is the term used to describe the changing of semi arid (dry) areas into desert. It is severe in Sudan, Chad, Senegal and Burkina Faso

What are the causes:

- Overcultivation: the land is continually used for crops and does not have time to recover eventually al the nutrients are depleted (taken out) and the ground eventually turns to dust.

- Overgrazing: In some areas animals have eaten all the vegetation leaving bare soil.

- Deforestation: Cutting down trees leaves soil open to erosion by wind and rain.

- Climate Change: Decrease in rainfall and rise in temperatures causes vegetation to die

What is being done to solve the problem?

Over the past twelve years Oxfam has worked with local villagers in Yatenga (Burkina Faso) training them in the process of BUNDING. This is building lines of stones across a slope to stop water and soil running away. This method preserves the topsoil and has improved farming and food production in the village.

Burkina Faso - desertification

This video shows the Sahel region south of the Sahara is at risk of becoming desert. Elders in a village in Burkina Faso describe how the area has changed from a fertile area to a drought-prone near-desert. The area experiences a dry season which can last up to eight or nine months. During this time rivers dry up and people, animals and crops are jeopardised.

This video showcases the Sahel region

Bringing dry land in the Sahel back to life

Facebook Twitter Print Email

Millions of hectares of farmland are lost to the desert each year in Africa’s Sahel region, but the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) is showing that traditional knowledge, combined with the latest technology, can turn arid ground back into fertile soil.

Those trying to grow crops in the Sahel region are often faced with poor soil, erratic rainfail and long periods of drought. However, the introduction of a state-of-the art heavy digger, the Delfino plough, is proving to be, literally, a breakthrough.

As part of its Action Against Desertification (AAD) programme, the FAO has brought the Delfino to four countries in the Sahel region – Burkina Faso, Niger, Nigeria and Senegal – to cut through impacted, bone-dry soil to a depth of more than half a metre.

The Delfino plough is extremely efficient: one hundred farmers digging irrigation ditches by hand can cover a hectare a day, but when the Delfino is hooked to a tractor, it can cover 15 to 20 hectares in a day.

Once an area is ploughed, the seeds of woody and herbaceous native species are then sown directly, and inoculated seedlings planted. These species are very resilient and work well in degraded land, providing vegetation cover and improving the productivity of previously barren lands.

In Burkina Faso and Niger, the target number of hectares for immediate restoration has already been met and extended thanks to the Delfino plough. In Nigeria and Senegal, it is working to scale up the restoration of degraded land.

Farming seen through a half-moon lens

This technology, whilst impressive, is proving to be successful because it is being used in tandem with traditional farming techniques.

“In the end the Delfino is just a plough. A very good and suitable plough, but a plough all the same,” says Moctar Sacande, Coordinator of FAO’s Action Against Desertification programme. “It is when we use it appropriately and in consultation and cooperation that we see such progress.”

The half-moon is a traditional Sahel planting method which creates contours to stop rainwater runoff, improving water infiltration and keeping the soil moist for longer. This creates favourable micro-climate conditions allowing seeds and seedlings to flourish.

The Delfino creates large half-moon catchments ready for planting seeds and seedlings, boosting rainwater harvesting tenfold and making soil more permeable for planting than the traditional - and backbreaking – method of digging by hand.

“The whole community is involved and has benefitted from fodder crops such as hay as high as their knees within just two years”, says Mr. Sacande. “They can feed their livestock and sell the surplus, and move on to gathering products such as edible fruits, natural oils for soaps, wild honey and plants for traditional medicine”.

Women taking the lead

According to Nora Berrahmouni, who was FAO’s Senior Forestry Officer for the African Regional Office when the Delfino was deployed, the plough will also reduce the burden on women.

“The season for the very hard work of hand-digging the half-moon irrigation dams comes when the men of the community have had to move with the animals. So, the work falls on the women,” says Ms. Berrahmouni.

Because the Delfino plough significantly speeds up the ploughing process and reduces the physical labour needed, it gives women extra time to manage their multitude of other tasks.

The project also aims to boost women’s participation in local land restoration on a bigger scale, offering them leadership roles through the village committees that plan the work of restoring land. Under the AAD programme, each site selected for restoration is encouraged to set up a village committee to manage the resources, so as to take ownership right from the beginning.

“Many women are running the local village committees which organise these activities and they are telling us they feel more empowered and respected,” offers Mr. Sacande.

Respecting local knowledge and traditional skills is another key to success. Communities have long understood that half-moon dams are the best way of harvesting rainwater for the long dry season. The mighty Delfino is just making the job more efficient and less physically demanding.

Millions of hectares lost to the desert, forests under threat

And it is urgent that progress is made. Land loss is a driver of many other problems such as hunger, poverty, unemployment, forced migration, conflict and an increased risk of extreme weather events related to climate change.

In Burkina Faso, for example, a third of the landscape is degraded. This means that over nine million hectares of land, once used for agriculture, is no longer viable for farming.

It is projected that degradation will continue to expand at 360 000 hectares per year. If the situation is not reversed, forests are at risk of being cleared to make way for productive agricultural land.

Africa is currently losing four million hectares of forest every year for this reason, yet has more than 700 million hectares of degraded land viable for restoration. By bringing degraded land back to life, farmers do not have to clear additional forest land to turn into cropland for Africa’s rising population and growing food demands.

When Mr. Sacande talks about restoring land in Africa, the passion in his voice is evident. “Restoring degraded land back to productive good health is a huge opportunity for Africa. It brings big social and economic benefits to rural farming communities,” he says. “It’s a bulwark against climate change and it brings technology to enhance traditional knowledge.”

A version of this story first appeared on the FAO website .

- Burkina Faso

- agriculture and food security

- Desertification

- climate action

Advertisement

Persistence and success of the Sahel desertification narrative

- Original Article

- Published: 21 September 2022

- Volume 22 , article number 118 , ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Fabrice Gangneron ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1460-3040 1 ,

- Caroline Pierre 2 ,

- Elodie Robert 3 ,

- Laurent Kergoat 1 ,

- Manuela Grippa 1 ,

- Françoise Guichard 4 ,

- Pierre Hiernaux 1 , 5 &

- Crystele Leauthaud 6

1320 Accesses

3 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The paradigm of Sahelian desertification, whose roots lie in the colonial period, increased in popularity following the droughts of the 1970s and 1980s. This “desertification narrative” was shaped in the international arena by organizations working in the fields of international cooperation, human rights, regional development, economic regulation and environmental questions. This narrative has been deployed to have real-world implications of how risks and responses in the Sahel are understood and prioritised, with particularly tangible implications for civil society and international donor agencies. It is indeed widely used in technical writings, general public media and environmental protection projects, regardless of the fact that the majority of literature in environmental science does not support its underlying rationales. It depicts rural populations as victims and culprits (or villains) partially responsible for the desertification, which in turn justifies external intervention in the Sahelian countries. The desertification narrative has an impact on research and development funding by overemphasizing the role of international development aid to combat desertification, thus favoring research on the subject of Sahelian desertification. Furthermore, we argue that the Sahelian desertification narrative contributes to the political control of rural populations, the latter being stigmatized because of their often-considered excessive use of environmental resources.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction to the Book

Environmental sustainability in post-conflict countries: insights for rural Colombia

An Introduction to Social Environmental Conflicts and Alternatives in Mexico

The Sahel is defined by the ecologist Le Houérou ( 1989 ) as the African land strip limited to the north by the 100-mm isohyet (below these annual accumulations extends the Sahara) and to the south by the 600-mm isohyet.

In French: Comité permanent inter-Etats de lutte contre la sécheresse au Sahel.

The “Special Report on Drought” (UNDRR 2021 ) was also cautious: the Sahel is mentioned for drought risks not to illustrate desertification.

Abdulrashid L (2017) Farmers perceptions of drivers of desertification and their impact on food security in Northern Katsina State. Int J Innov Environ Stud Res 5(2):17–27

Adger WN, Benjaminsen TA, Brown K, Svarstad H (2001) Advancing a political ecology of global environmental discourses. Dev and Change 32(4):681–715. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00222

Article Google Scholar

Almazroui M, Saeed F, Saeed S, Islam NI, Ismail M et al (2021) Projected change in temperature and precipitation over Africa from CMIP6. Earth Syst and Environ 4(3):455–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-020-00161-x

Amogu O, Descroix L, Yéro KS, Le Breton E, Mamadou I et al (2010) Increasing River Flows in the Sahel? Water 2(2):170–199. https://doi.org/10.3390/w2020170

Anchang JY, Prihodko L, Kaptué AT, Ross CW, Ji W et al (2019) Trends in woody and herbaceous vegetation in the Savannas of West Africa. Remote Sens 11(5):576. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11050576

Anyamba A, Tucker CJ (2005) Analysis of Sahélian vegetation dynamics using NOAA-AVHRR data from 1981-2003. J Arid Environ 63(3):596–614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2005.03.007

Assouma MH, Lecomte P, Hiernaux P, Ickowicz A, Corniaux C et al (2018) How to better account for livestock diversity and fodder seasonality in assessing the fodder intake of livestock grazing semi-arid sub-Saharan Africa rangelands. Livest Sci 216:16–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2018.07.002

Aubreville A (1936) Les forêts de la colonie du Niger, bull. com. AOF 19, n°1 pp 1–95

Ballouche A, Taïbi AN (2013) Le « dessèchement » de l’Afrique sahélienne : un leitmotiv du discours d’expert revisité. Autrepart, No 65:47–66. https://doi.org/10.3917/autr.065.0047

Bassett, T J, Zueli, K B (2004) Environmental discourses and the Ivorian Savanna. Ann. of the Assoc. of American Geographers 90, pp 67–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/0004-5608.00184

Batterburry S, Warren A (2001) The African Sahel 25 years after the great drought: assessing progress and moving towards new agendas and approaches. Glob Environ Change 11(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-3780(00)00040-6

Behnke R, Mortimore M (ed) (2016) The end of desertification? Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-16014-1

Benjaminsen TA (1997) Is there a Fuelwood Crisis in Rural Mali? Geoj 43(2):163–174

Benjaminsen TA, Svarstad H (2009) Qu’est-ce que la political ecology ? Nat Sci Et Soc 17:3–11

Benjaminsen TA, Hiernaux P (2019) From desiccation to global climate change: a history of the desertification narrative in the west African Sahel, 1900–2018. Glob Environ 12:206–236. https://doi.org/10.3197/ge.2019.120109

Bernus E (1995) Pasteurs face à la sécheresse: rebondir ou disparaître ? Rev De Geogr De Lyon 70(3–4):255–259

Bichet A, Diedhiou A (2018) West African Sahel has become wetter during the last 30 years, but dry spells are shorter and more frequent. Clim Res 75:155–162. https://doi.org/10.3354/cr01515

Blanc G (2020) L’invention du colonialisme vert. Flammarion, Pour en finir avec le mythe de l’éden africain

Google Scholar

Blanc G (2022) La préservation de la nature est-elle (néo)coloniale ? L’invention des parcs nationaux en Afrique. Rev Int et Strateg (124):17–27. https://doi.org/10.3917/ris.124.0017

Blundo G (2000) Elus locaux et courtiers en développement au Sénégal. Trajectoires politiques, modes de légitimation et stratégies d’alliance. In: Bierschenk T, Chauveau J P, Olivier de Sardan J P Courtiers en développement. Les villages africains en quête de projets. APAD_Karthala pp 71–100

Brandt M, Hiernaux P, Rasmussen K, Mbow C, Kergoat L et al (2016) Assessing woody vegetation trends in Sahelian drylands using MODIS based seasonal metrics. Remote Sens of Environ 183:215–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2016.05.027

Brandt M, Rasmussen K, Hiernaux P, Herrmann S, Tucker CJ et al (2018) Reduction of tree cover in West African woodlands and promotion in semi-arid farmlands. Nat Geosci 11:328–333. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-018-0092-x

Article CAS Google Scholar

Brandt M, Hiernaux P, Rasmussen K et al (2019) Changes in rainfall distribution promote woody foliage production in the Sahel. Commun Biol 2:133. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-019-0383-9

Brundtland G H (1987) Report of the World Commission on environment and development: our common future. UN

Chudeau R (1916) Le climat de l’Afrique occidentale et équatoriale. Annales De Géographie 25(138):429–462

Dardel C, Kergoat L, Hiernaux P, Mougin E, Grippa M et al (2014a) Re-greening Sahel: 30 years of remote sensing data and field observations (Mali, Niger). Remote Sens of Environ 140:350–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2013.09.011

Dardel C, Kergoat L, Hiernaux P, Grippa M, Mougin E et al (2014b) Rain-use-efficiency: what it tells us about the conflicting Sahel greening and Sahelian paradox. Remote Sens 6(4):3446–3474. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs6043446

Daoust G, Selby J (2022) Understanding the politics of climate security policy discourse: The Case of the Lake Chad Basin. Geopolitics. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2021.2014821

Davis DK (2005) Indigenous knowledge and desertification debate: problematizing expert knowledge in North Africa? Geoforum 36:509–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2004.08.003

Davis DK (2016) The arid lands. History Power, Knowledge, MIT Press Cambridge, MA. https://doi.org/10.1080/2325548X.2019.1546033

De Gironcourt G (1912) Le sommet de la boucle du Niger : géographie physique et botanique Bulletin de la société de géographie (25):153–172

Descroix L, Guichard F, Grippa M, Lambert LA, Panthou G et al (2018) Evolution of surface hydrology in the Sahelo-Sudanian strip: an updated review. Water 10(6):748. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10060748

Dia A H, Becerra S, Gangneron F (2008) Crises climatiques, ruptures politiques et transformation de l’action publique environnementale au Mali. VertigO 8(1). https://doi.org/10.4000/vertigo.1468

Duval C (2010) Ferricrete, forests, and temporal scale in the production of colonial science in Africa, chap. 6 in: G Goldman M J, Nadasdy P, Turner M D (2010) Knowing Nature. Conversations at the Intersection of Political Ecology and Science Studies. University of Chicago press, pp 113–127

Fairhead J, Leach M (1996) Misreading the African landscape: society and ecology in a forest-savanna mosaic. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139164023

Favreau G, Cappelaere B, Massuel S, Leblanc M, Boucher M et al (2009) Land clearing, climate variability, and water resources increase in semiarid southwest Niger: A review. Water Resour Res 45:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007WR006785

Folke C, Biggs R, Norström AV, Reyers B, Rockström J (2016) Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecology and Soc 21(3):41. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08748-210341

Forsyth (2003) Critical political ecology: the politics of environmental science. Routledge, London

Gal L, Grippa M, Hiernaux P, Peugeot C, Mougin E et al (2016) (2016) Changes in lakes water volume and runoff over ungauged Sahelian watersheds. J of Hydrol 540:1176–1188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2016.07.035

Gal L, Grippa M, Hiernaux P, Pons L, Kergoat L (2017) The paradoxical evolution of runoff in the pastoral Sahel. Analysis of the hydrological changes over the Agoufou watershed (Mali) using the KINEROS-2 model. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 21:4591–4613. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-21-4591

Galle S, Grippa M, Peugeot C, Bouzou Moussa I, Cappelaere B et al (2018) A critical zone observatory in West Africa monitoring a region in transition, Vadose Zone J., Special issue on “hydrology Observatories”, pp 1–24 https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2018.03.0062

Gangneron F (2013) Ressources pastorales et territorialité chez les agro-éleveurs sahéliens du Gourma des buttes. VertigO 13(3). https://doi.org/10.4000/vertigo.14427

Gangneron F, Robert E (2015) Droits au sol et gestion de la fertilité. Deux perspectives différentes : Djougou (Bénin) et Niakhar (Sénégal). In: Sultan B, Lalou R, Sanni A M, Oumarou A, Soumare M A (ed) Les sociétés rurales face aux changements climatiques et environnementaux en Afrique de l’Ouest, chap. 12, IRD Editions

Gardelle J, Hiernaux P, Kergoat L, Grippa M (2010) Less rain, more water in ponds: a remote sensing study of the dynamic of waters from 1950 to present in pastoral Sahel (Gourma region, Mali). Hydrol And Earth Syst Sci (14)309-324. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-14-309-2010

Goldman MJ, Nadasdy P, Turner MD (2010) Knowing Nature. University of Chicago press, Conversations at the Intersection of Political Ecology and Science Studies

Greve AM, Lampietti J, Falloux F (1995) National environmental action plans in Sub-Saharan Africa. In towards environmentally sustainable development in Sub-Saharan Africa, Paper 6. World Bank, Washington

Guichard F, Kergoat L, Hourdin F, Léauthaud C, Barbier J et al (2015) Le réchauffement climatique observe. In: Sultan B, Lalou R, Sanni A M, Oumarou A, Soumare M A (ed) Les sociétés rurales face aux changements climatiques et environnementaux en Afrique de l’Ouest, chap. 1, IRD Editions, pp 249–267

Harroy JP (1944) Afrique terre qui meure. La dégradation des sols africains sous l'influence de la colonisation. Marcel Hayez, Bruxelles, p 556

Hiernaux P, Adamou K, Moumouni O, Turner M D, Tong X et al (2019) Expanding network of field hedges in density populated landscapes in the Sahel. For Ecol Manag (440)178–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.03.016

Hiernaux P, Ayantunde AA, Adamou K, Mougin E, Gérard B et al (2009) Trends in productivity of crops, fallows and rangelands in Southwest Niger: Impact of land use, management and climate changes. J of Hydrol 375(1–2):65–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.01.032

Hiernaux P, Kalilou AA, Kergoat L, Brandt M, Mougin E et al (2022) Woody plant decline in the Sahel of western Niger (1996–2017): is it driven by climate of land use changes? J of Arid Environ 200:104719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2022.104719

Hubert H (1917) progression du dessèchement de l’Afrique Occidentale. Bulletin du comité historique et scientifique de l’Afrique Occidentale, pp 401–467

IPCC (2020) Summary for policymakers. In: Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Pörtner H-O, Roberts D, Skea J, Shukla PR, Calvo Buendia E, Slade R, Connors S, van Diemen R, Ferrat M, Haughey E, Luz S, Neogi S, Pathak M, Petzold J, Portugal Pereira J, Vyas P, Huntley E, Kissick K, Belkacemi M, Malley J (eds) Climate change and land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems Geneva, Switzerland: The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

Kaptué AT, Prihodko L, Hanan NP (2015) On Regreening and Degradation in Sahelian Watersheds. PNAS 112(39):12133–12138. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1509645112

Kergoat L, Grippa M, Hiernaux P, Ramarohetra J, Gardelle J et al (2015) Evolutions paradoxales des mares en Sahel non cultivé : diagnostic, causes et conséquences. In: Sultan B, Lalou R, Sanni A M, Oumarou A, Soumare M A (ed) les sociétés rurales face aux changements climatiques et environnementaux en Afrique de l’Ouest, chap. 9, IRD Editions, pp 193–208

Lahache MJ (1907) le dessèchement de l’Afrique française est-il démontré ? Bulletin De La Société De Géographie Et D’études Coloniales De Marseille 31:149–185

Lavigne Delville P (2017) la fabrique de l’action publique des pays sous régime d’aide. Anthropol. et dev, n°45. https://doi.org/10.4000/anthropodev.529 , pp 33–64

Leach M, Mearns R (1996) Environmental change and policy: challenging received wisdom in Africa. In: Leach M, Mearns R (eds) The lie of the land: challenging received wisdom in African environment. The Int. African Institute, London, pp 1–33

Lebel T, Ali A (2009) Recent trends in the Central and Western Sahel rainfall regime (1990–2007). J of Hydrol 375(1–2):52–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2008.11.030

Le Houérou HN (1989) The grazing land ecosystems of African Sahel. Springer-Varlag, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-74457-0

Magrin G, Mugelé R (2020) La boucle de l’Anthropocène au Sahel : nature et sociétés face aux grands projets environnementaux (Grande Muraille Verte, sauvegarde du lac Tchad). Belgeo 3. https://doi.org/10.4000/belgeo.42872

Magrin G, Lemoalle J (2015) Les projets de transfert d’eau vers le lac Tchad : des utopies initiales aux défis contemporains. In: Magrin G, Lemoalle J, Pourtier R, Déby Itno I, Fabius L et al. Atlas du lac Tchad, numéro spécial 183, pp 156–158

Mainguet M (1994) Desertification. Natural Background and Human Mismanagement. Springer study edition

Mahé G, Paturel J-E (2009) 1896–2006 Sahelian annual rainfall variability and runoff increase of Sahelian rivers. CR Geosci 341(7):538–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crte.2009.05.002

Mangin M (1924) Une mission forestière en Afrique Occidentale Française. La Géographie 42:449–483

Marty A (1993) LA gestion de terroirs et les éleveurs : un outil d’exclusion ou de négociation ? Tiers-Monde 34(134):327–344. https://doi.org/10.3406/tiers.1993.4756

Marteau R, Sultan B, Moron V, Alhassane A, Baron C et al (2011) The onset of the rainy season and farmers’ sowing strategy for pearl millet cultivation in Southwest Niger. Agric and for Meteorol 151:1356–1369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2011.05.018

Massazza G, Bacci M, Descroix L, Ibrahim MH, Fiorillo E et al (2021) Recent changes in hydroclimatic patterns over medium Niger River basins at the Origin of the 2020 Flood in Niamey (Niger). Water 13(12):1659. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13121659

McCann JC (1999) Climate and causation in African history. The Int J Afr Stud 32(2/3):261–279. https://doi.org/10.2307/220342

Mirzabaev A, Wu J, Evans J, García-Oliva F, Hussein IAG et al (2019) Desertification. In: Shukla PR, Calvo Buendia E, Slade R, Connors S, van Diemen R, Ferrat M, Haughey E, Luz S, Neogi S, Pathak M, Petzold J, Portugal Pereira J, Vyas P, Huntley E, Kissick K, Belkacemi M, Malley J (eds) Climate change and land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems, pp 149–343

Jones B (1938) Desiccation and the West African Colonies, The Geogr. J. 91 pp 401–423

Mugelé R (2018) La Grande Muraille Verte : géographie d’une utopie environnementale au Sahel. Thèse de doctorat de géographie, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, 322 p

Nguyen CC (2015) Thèse de doctorat, Université de Toulouse

Nicholson SE (2013) The West African Sahel: a review of recent studies on the rainfall regime and its interannual variability. Inter Sch Res Not. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/453521

Nicholson SE (2005) On the question of the “recovery” of the rains in the West African Sahel. J Arid Environ 63(3):615–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2005.03.004

Olivier de Sardan J P, Bierschenk T (1993) Les courtiers locaux du développement. Bulletin de l’APAD, n°5

Olsson L, Eklundh L, Ardö J (2005) A recent greening of the Sahel-trends, patterns and potential causes. J of Arid Environ 63(3):556–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2005.03.008

One Planet Summit (2021) Des engagements pour agir en faveur de la biodiversité. Paris. https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2021/01/12/one-planet-summit-des-engagements-pour-agir-en-faveur-de-la-biodiversite . Accessed 5 July 2022

Olwig MF, Rasmussen LV (2015) West African waterworlds: narratives of absence versus narratives of excess. In: K. Hastrup and F. Hastrup (eds) Waterworlds: anthropology in fluid environments. Berghahn Books, pp 110–128

Ozer P, Hountondji YC, Niang AJ, Karimoune S, Laminou Manzo O et al (2010) Désertification au Sahel : Historique et perspectives. Bsglg 54:69–84

Panthou G, Vischel T, Lebel T (2014) Recent trends in the regime of extreme rainfall in the Central Sahel. Int J of Climatol 34:3998–4006. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.3984

Pham-Duc B, Sylvestre F, Papa F, Frappart F, Bouchez C et al (2020) The Lake Chad hydrology under current climate change. Sci Rep 10:5498. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62417-w

Prince SD, Wessels KJ, Tucker CJ, Nicholson SE (2007) Desertification in the Sahel: a reinterpretation of a reinterpretation. Glob Change Biol 13(7):1308–1313. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01356.x

Petit O, Romagny R (2009) La reconnaissance de l’eau comme patrimoine commun : quels enjeux pour l’analyse économique ? Mondes En Développement, No 145:29–54. https://doi.org/10.3917/med.145.0029

Rangé C, Magnani S, Ancey V (2020) Pastoralisme et insécurité en Afrique de l’Ouest. Du narratif réifiant à la dépossession politique. Rev Int Des Études Du Dev (243)115–150. https://doi.org/10.3917/ried.243.0115

Reenberg A (2012) Insistent dryland narratives: portraits of knowledge about human-environmental interactions in Sahelian Environment Policy Documents. J of Appl Ecol 20:97–111

Reynolds, JF, Smith, MS (2002) Global desertification. do humans cause deserts?. Berlin: Dahlem University Press

Riegel J (2015) La circulation des normes de l’UICN au Sénégal au prisme des praticiens et du politique. Thèse de doctorat.

Robert E, Gangneron F (2015) Un “SIG à dires d’acteurs” : décryptage des vulnérabilités environnementales des agro-éleveurs et pasteurs au Bénin, Cybergéo. Eur J Geogr. https://doi.org/10.4000/cybergeo.27285

Roehrig R, Bouniol D, Guichard F, Hourdin F, Redelsperger J-L (2013) The present and future of the West African monsoon: a process-oriented assessment of CMIP5 simulations along the AMMA transect. J Clim 26:6471–6505. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00505.1

Sayre NF (2017) The politics of scales. University of Chicago press, Chicago, A history of range science

Book Google Scholar

Scoones I (2018) Review of the end of desertification? Disputing environmental change in the drylands by Roy H. Behnke and Michael Mortimore. Springer-Verlag, Berlin (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13570-018-0133-5

Scoones I, Toulmin C (2021) The Sahelian Great Green Wall: start with local solutions. Pastres. https://pastres.org/2021/01/29/the-sahelian-great-green-wall-start-with-local-solutions/ . Accessed 5 July 2022

Sighomnou D, Descroix L, Genthon P, Mahé G, Bouzou Moussa I et al (2013) (2013) La crue de 2012 à Niamey : un paroxysme du paradoxe du Sahel ? Sécheresse 24:3–13

Slegers MFW, Stroosnijder L (2008) Beyond the desertification narrative: a framework for agriculture drought in semi-arid East Africa. AMBIO: A J Hum Environ 31(5):372–380. https://doi.org/10.1579/07-A-385.1

Sougueh C (2021) La grande muraille verte, vecteur de développement durable au Sahel, The conversat. https://theconversation.com/la-grande-muraille-verte-vecteur-de-developpement-durable-au-sahel-154195 . Accessed 04 Sep 2022

Stebbing EP (1935) The encroaching Sahara: the threat to the West African Colonies. The Geogr J 85:506–524

Stebbing EP (1937) The threat of Sahara. J of the R African Soc 37:3–35

Swift J (1996) Desertification: narrative, winners & losers. In: Leach M and Mearns R. The lie of the land: challenging received wisdom on the African environment. James Currey Ltd, Oxford. pp 73–90

Taylor CM, Belušić D, Guichard F, Parker DJ, Vischel T et al (2017) Frequency of extreme Sahelian storms tripled since 1982 in satellite observations. Nat 544(7651):475–478. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature22069

Thomas N, Nigam S (2018) Twentieth-century climate change over Africa: seasonal hydroclimate trends and Sahara desert expansion. J Clim 31(9):3349–3370. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-17-0187.1

Tiffen M, Mortimore M (2002) Questioning desertification in dryland sub-saharan Africa. Nat Res Forum 26(3):218–233

Toulmin C, Brock K (2016) Desertification in the Sahel: local practice meets global narrative, in Behnke R and Mortimore M (ed.) The end of desertification? Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-16014-1_2

Trichon V, Hiernaux P, Walcker R, Mougin E (2018) The persistent decline of patterned woody vegetation: the tiger bush in the context of the regional Sahel greening trend. Glob Change Biol 24(6):2633–2648. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14059

Turner MD (1999) No space for participation: pastoralist narratives and etiology of park-herder conflict in southeastern Niger. Land Degrad Dev 10:345–363. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-145X(199907/08)10:4<345::AID-LDR358>3.0.CO;2-8

Turner MD (2004) Political ecology and moral dimension of « resources conflicts »: the case of farmer-herder conflicts in the Sahel. Political Geogr (23)863–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2004.05.009

Turner MD, Ayantunde AA, Patterson KP, Patterson ED (2011) Livelihood transitions and the changing nature of farmer-herder conflict in Sahelian West Africa. The J of Dev Stud 47(2):183–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220381003599352

UNCCD (1994) Convention des Nations unies sur la lutte contre la désertification dans les pays gravement touchés par la sécheresse et/ou la désertification, en particulier en Afrique (texte final de la convention), AG/ONU, 65 p.

UNCCD (2020) The Great Green Wall implementation status and way ahead to 2030

UNCOD (United Nations Conference on Desertification) (1978) Round up, Plan of Action and Resolutions, August 29 – September 9, 1977, New York, http://www.ciesin.org/docs/002-478/002-478.html . Accessed 20 June 2022

UNDRR (2021) Global assessment report on disaster risk reduction. Special report on drought 2021

Yeo NR (2018) Diagnostic environnemental de la mise en œuvre du programme Grande Muraille Verte au Sénégal. Mémoire Master 2, AgroParisTech, Montpellier, 119 p

Zakinet D (2015) Des pasteurs transhumants entre alliances et conflits au Tchad. Afr Contemp (255)127–143. https://doi.org/10.3917/afco.255.0127

Zhang W, Brandt M, Guichard F, Tian Q, Pierre C et al (2017) Using long-term daily satellite-based rainfall data (1983–2015) to analyze spatio-temporal changes in the sahelian rainfall regime. J Hydrolog 550:427–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2017.05.033

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work is dedicated to Françoise Guichard, who passed away in late 2020. She was an inspiring scientist, colleague and friend. She is deeply missed.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

GET, Université de Toulouse, CNRS, IRD, UPS, Toulouse, France

Fabrice Gangneron, Laurent Kergoat, Manuela Grippa & Pierre Hiernaux

iEES-Paris, Sorbonne Univ., UPMC Univ., CNRS, IRD, INRA, UPD, UPEC, Paris, France

Caroline Pierre

LETG, CNRS, Nantes Université, Nantes, France

Elodie Robert

CNRM, CNRS, Météo-France, Toulouse, France

Françoise Guichard

Pastoralisme Conseil, Caylus, France

Pierre Hiernaux

G-EAU, AgroParisTech, Cirad, IRD, INRAE, L’Institut Agro Montpellier, Univ Montpellier, Montpellier, France

Crystele Leauthaud

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Fabrice Gangneron .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Chandni Singh

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Gangneron, F., Pierre, C., Robert, E. et al. Persistence and success of the Sahel desertification narrative. Reg Environ Change 22 , 118 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-022-01969-1

Download citation

Received : 30 September 2020

Accepted : 20 August 2022

Published : 21 September 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-022-01969-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Desertification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

We Are Water

- Donate Donate

Get news and insights

The Sahel, desertification beyond drought

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share by WhatsApp

- Agriculture

- Climate and environment

The periodic crises in the African “Hunger Belt” have provided a more accurate and effective vision of the relationship between desertification and human activities. Regardless of the droughts, poor resource exploitation practices have been determinants of land degradation. The African Great Green Wall project gives hope to the Sahel, one of the most vulnerable areas to the current climate crisis.

©Sahara-NASA

Between 1984 and 1985, international media brought to the world’s attention the existence of what was called the “Hunger Belt”. A massive drought had affected the Sahel, the large 5,400-km strip that crosses Africa from west to east, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea. The land was left without water and without a blade of grass, and the inhabitants of this vast area of four million km², mostly shepherds, saw all their livestock die. A great famine broke out, the media repercussions of which changed the way in which the international community related climate to desertification. Scientists and economists pointed out that inadequate human actions were the main cause of desertification and that droughts only triggered its effects.

It was not the first time that the Sahel had been ravaged by a drought. Since systematic records started being kept, at the beginning of the 20 th century, the area has experienced alternating climatic periods of abundant and scarce rainfall. The first recorded drought took place in 1915, causing a great migration towards more fertile areas in the south. During the 1960s, there was a period of abundant rainfall that filled the water wells and caused the return of shepherds and farmers, largely driven by the governments of the countries of the strip, some of them recently decolonized.

But then droughts returned with greater force. Between the years 1968 and 1974 , grazing became impossible and the lack of water triggered a large-scale famine that led to the first mobilization of external aid and the creation of the International Fund for Agricultural Development by United Nations. The soil of the Sahel had degraded to such an extent that, in 1977, the first United Nations Conference on Desertification was organized in Nairobi, Kenya. In 1994, the United Nations declared the 17th June as the World Day to Combat Desertification and Drought , and the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) was established in 1996. The UNCCD defined desertification as “land degradation in arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas resulting from various factors including climatic variations and human activities.”

© Jon Evans

A significant aspect of this definition is the separation of two concepts, “climatic variations” and “human activities”, which until then had been unclear for public opinion and many experts, who had traditionally considered desertification as a direct effect of droughts.

The terrible crisis of 1984 brought to light the bad practices carried out in the area until then: the increase of grazing and agriculture, promoted by governments and the farmers themselves in rainy periods, had caused a systematic over-exploitation of the land well above its average capacity to provide water and pasture. The short-term vision of governments and communities, seeking to maximize economic returns in the shortest possible time, had led to a severe degradation of the soil.

Between the desert and the savannah

The term Sahel comes from the Arab word sā ḥ il, which means “edge or coast”. A geographically and climatically correct meaning for an area bordered to the north by the Sahara Desert and to the south by the savannahs and jungles of the Gulf of Guinea and Central Africa. From the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea, the Sahel extends through northern Senegal, southern Mauritania, the central areas of Mali and Niger, northern Burkina Faso, southern Algeria, northern Nigeria, the central strip of Chad and Sudan, virtually all Eritrea and northern Ethiopia.

Sahelmap ©Flockedereisbaer

Annual rainfall ranges from 100–200 mm in the north of the strip up to 600 mm in the south, where climatologists place the beginning of the tropical forests. The Sahel lands are grasslands and savannahs, with scrub areas to the north, alternating areas of trees, mainly acacias, in the south.

There is no accurate data on the population of the Sahel, where there is one of the world’s highest rates of statistical invisibility and uncontrolled migratory movements caused by droughts, armed conflicts and Boko Haram’s terrorism that affect some of its regions. According to United Nations forecasts, the Sahel’s current population is around 75 million and will almost triple by 2050 reaching nearly 200 million. In 2016, those under the age of 24 were between 60% and 70% of the population, and these figures tend to be maintained over the next 20 years. The lack of prospects forces this young population to exert a considerable migratory pressure in southern areas, a pressure that spreads to European countries.

The Great Green Wall, a great hope

In 2007, the Heads of State and Government of Burkina Faso, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sudan and Chad, with the support of the African Union, decided to launch a project to combat desertification in the Sahel and provide a dignified life with a future to its inhabitants: the Great Green Wall of Africa. The initiative reflects the spirit of the Kenyan ecologist Wangari Maathai, who was the first African woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004. Maathai created the Green Belt Movement, an initiative that planted more than 30 million trees in her country.

The Great Green Wall aims to become a 15 km wide and 8,000 km long plant barrier along the Sahel. The realization of climate change and the last famine of 2010 have provided strength to this initiative that aims to repair the endemic governance errors in the area and the erroneous approach often taken when facing the desertification problem. Based on its dimensions, it surpasses any collective work carried out by mankind and some define it as the eighth world wonder: nothing less than covering 100 million hectares of semi-desert with a green mantle.

©World Bank Photo Collection

The project met with some criticism from ecologists, who considered that the solution was not to “plant trees”, as the project had mainly focused on, but rather to opt for the natural regeneration of the land and identify the flora of each area to protect it. This work necessarily requires the participation of the inhabitants who need to be trained for the process to be sustainable and for the restored areas to be maintained.

There was also criticism from different economists who pointed out that the implementation pace was not realistic and that the attainment of the high investment needed had not been taken into consideration. The achievement of the project was linked to the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which implied a regeneration pace of 5 million hectares per year.

In view of this reality, the African Union proposed a less ambitious but more realistic date: the one set out in the 2063 Agenda. But many point out that it is still necessary to work at a rate of two million hectares per year, much higher than the estimated, which will probably be less than 200,000 hectares per year.

Common commitment, a reference value

The project has collected all criticisms and has restructured itself to attain its goals. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) is currently committed to ensuring that lasting impacts are generated in the areas of action, and the project already gathers more than 20 African countries and various civil institutions and research centers. An added value of the proposed model is that it can be exported anywhere with dry conditions and fragile ecosystems, such as areas of Fiji and Haiti, countries that have started similar projects.

Regardless of its realism, the African Great Green Wall has as its main value to have brought together governments and communities in a common commitment to combat desertification and move forward in the fight against poverty. It has also allowed the creation of an international observatory that reveals the misery of the lack of access to water and education, and the need for an efficient management of the territory and its resources to combat desertification and remove millions of people from climatic vulnerability. The fight against desertification is a challenge that affects all the inhabitants of the planet. We need to follow what is happening in the Sahel, in India, in China and in the other menaced areas, such as the ones in the Mediterranean Arch, the south of Africa, Central America and large Andean areas. Life of future generations on Earth depends on what we learn from it.

Related insights

The power of a small reservoir

The inside of India is drying out

Awaiting the monsoon of life

Desertification is not far. It is already here

Sign up to receive news about the water crisis and We Are Water projects.

" * " indicates required fields

Desertification, Adaptation and Resilience in the Sahel: Lessons from Long Term Monitoring of Agro-ecosystems

The desertification paradigm has a long history in the Sahel, from colonial to modern times. Despite scientific challenge, it continued to be influential after independence, revived by the dramatic droughts of the 1970s and 1980s, and was institutionalized at local, national and international levels. Collaborative efforts were made to improve scientific knowledge on the functioning, environmental impact and monitoring of selected agricultural systems over the long term, and to assess trends in the ecosystems, beyond their short term variability. Two case studies are developed here: the pastoral system of the arid to semi-arid Gourma in Mali, and the mixed farming system of the semi-arid Fakara in Niger. The pastoral landscapes are resilient to droughts, except on shallow soils, and to grazing, following a non-equilibrium model. The impact of cropping on the landscape is larger and longer lasting. It also induces locally high grazing pressure that pushes rangeland resilience to its limits. By spatial transfer of organic matter and mineral, farmers’ livestock create patches of higher fertility that locally enhance the system’s resilience. The agro-pastoral ecosystem remains non-equilibrial provided that inputs do not increase stocking rates disproportionately. Remote sensing confirms the overall re-greening of the Sahel after the drought of the 1980s, contrary to the paradigm of desertification. Ways forward are proposed to adapt the pastoral and mixed farming economies and their regional integration to the context of human and livestock population growth and expanding croplands.

Habitat type

- Agricultural landscape

Related papers

- Envisioning the future and learning from the past: Adapting to a changing environment in northern Mali

- Ecosystem-Based Adaptation for Food Security in the AIMS SIDS: Integrating External and Local Knowledge

- The role of carbon plantations in mitigating climate change: potentials and costs

Nature based approach

- Ecosystem-based adaptation

- Nature-based agricultural systems

- A socio-eco-efficiency analysis of integrated and non-integrated crop-livestock-forestry systems in the Brazilian Cerrado based on LCA

- Ocean conservation boosts climate change mitigation and adaptation

- Climate risk adaptation by smallholder farmers: the roles of trees and agroforestry

Nature based target

- Working on the boundaries – How do science use and interpret the nature-based solution concept?

- Agroforestry Can Enhance Food Security While Meeting Other Sustainable Development Goals

- Ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction in mountains

- Find Flashcards

- Make Flashcards

- Why It Works

- Tutors & resellers

- Content partnerships

- Teachers & professors

- Employee training

- Get Started

Brainscape's Knowledge Genome TM

Entrance exams, professional certifications.

- Foreign Languages

- Medical & Nursing

Humanities & Social Studies

Mathematics, health & fitness, business & finance, technology & engineering, food & beverage, random knowledge, see full index.

GCSE Geography Theme 2 > CASE STUDY 9 : DESERTIFICATION CASE STUDY - SAHEL > Flashcards

CASE STUDY 9 : DESERTIFICATION CASE STUDY - SAHEL Flashcards

OVER CULTIVATION (DEFINITION)

OCCURS WHEN CROPS ARE GROWN ON THE SAME PIECE OF LAND YEAR AFTER YEAR AND THE NUTRIENTS RUN OUT AND THE CROPS DIE LEAVING THE SOIL BARE

OVER 350,OOO STARVED IN NIGER IN 2010 DUE TO DROUGHT AND DESERTFICATION

2,500KM (SQUARED) OF LAND LOST EACH YEAR TO DESERTIFICATION IN NIGER

INLAND AND MADE UP OF COUNTRIES SUCH AS CHAD, SUDAN, AND NIGER

SOUTH OF SAHARA DESERT = VERY HOT AND DRY

ALSO NORTH OF THE CONGO RIVER BASIN = ECOSYSTEM IS A RAINFOREST

OVER GRAZING (DEFINITION)

WHEN LIVESTOCK IS ALLOWED TO EAT TOO MUCH VEGETATION. THIS CAUSES THE SOIL TO BECOME BARE AND VULNERABLE TO RAIN AND WIND EROSION.

AFFORESTATON ( ESTABLISHMENT OF FOREST) WITH ACACIA

RAINWATER HARVESTING

BUILDING ROCK BUNDS TO PREVENT SOIL EROSION AND MAINTAIN MOISTURE

INTERNATIONAL GREEN WALL

PROVIDE A WALL OF VEGETATION PLANTED IN A LONG LINE ACROSS THE SAHEL TO PROVIDE A BARRIER AGAINST THE ADVANCE OF THE SAHARA DESERT.

DIFFICULT TO DO AS ALL COUNTRIES OF THE SAHEL HAVE TO AGREE TO DO THIS

DESERTIFICATION (DEFINITION)

THE PROCESS OF BECOMING MORE DESERT LIKE

DESERTIFICATION IS ENCOURAGED WHEN THE TOPSOIL IS REMOVED BY EROSION. ANYTHING THAT REMOVES VEGETATION FROM THE SOIL LEAVES IT VULNERABLE TO EROSION

AFFORESTATION

ESTABLISHMENT OF FOREST

CREATES HABITAT FOR ANIMALS LONG PERIOD OF TIME FOR GROWTH

HAND MADE ROCK DAMS TO PREVENT SOIL EROSION AND MAINTAIN MOISTURE

+ SIDE = CHEAP

=-VE SIDE = LOOKS AWFUL

HUMAN CAUSES

MORE GOATS ARE KEPT FOR FOOD AND MILK = OVERGRAZING KILLS VEGETATION

LOCAL PEOPLE ARE MORE SETTLED (LESS NOMADIC) = SAME AREAS CLOSE TO VILLAGE ARE GRAZED

GCSE Geography Theme 2 (12 decks)

- Geography Theme 2 - Weather/Climate

- Geograhy Theme 2 - Ecosystems

- Geography Theme 2 - Drought

- Geography Theme 2 - Rivers

- Georgraphy Theme 2 - Coastal Processes and landforms

- CASE STUDY 10 : FLOODING CASE STUDY - BANGLADESH

- CASE STUDY 7 : EXTREME WEATHER EVENT CASE STUDY - TYPHOON HAIYAN, PHILIPPINES

- Geography Theme 2 - The hydrological cycle

- CASE STUDY 9 : DESERTIFICATION CASE STUDY - SAHEL

- CASE STUDY 8 : ECOSYSTEMS CASE STUDY - AMAZON RAIN FOREST

- CASE STUDY 11 : FLOODING (LOCAL SCALE) CASE STUDY - HOE STREAM

- CASE STUDY 12 : COASTS CASE STUDY - BARTON ON SEA : DORSET/HAMPSHIRE COAST LINE

- Corporate Training

- Teachers & Schools

- Android App

- Help Center

- Law Education

- All Subjects A-Z

- All Certified Classes

- Earn Money!

Case Study: Sahel Desertification

This video showcases desertification in the Sahel region of the Sahara.

To read the case study about the desertification of the Sahel region visit Revision World .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Desertification in the Sahel region is a pressing environmental issue with far-reaching consequences. In this article, we will explore the causes, effects, and potential solutions to combat desertification, using a case study from the Sahel region.

Case Study: Sahel Desertification. What is desertification: It is the term used to describe the changing of semi arid (dry) areas into desert. It is severe in Sudan, Chad, Senegal and Burkina Faso ... Burkina Faso - desertification. This video shows the Sahel region south of the Sahara is at risk of becoming desert. Elders in a village in ...

The Sahel. Location of the two case studies, the Gourma region in Mali and the Dantiandou district (Fakara) in Niger, in the Sahel delineated by the 600 and 100 mm rainfall isohyets, south of the Sahara. ... Prince, S. D., Wessels, K. J., Tucker, C. J., & Nicholson, S. E. (2007). Desertification in the Sahel: A reinterpretation of a ...

23 January 2022 Humanitarian Aid. Millions of hectares of farmland are lost to the desert each year in Africa's Sahel region, but the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) is showing that traditional knowledge, combined with the latest technology, can turn arid ground back into fertile soil. Those trying to grow crops in the Sahel region ...

A case study of the Tin Adjar watershed in Mali (Kergoat et al. 2015) showed that this small watershed experienced strong erosion and that the area of "rocky outcrops and hardpan" increased by 12% from 1954 to 2007. The area of eroded loam soils also increased significantly. ... The Sahel desertification narrative is not recent and has ...

Between 1984 and 1985, international media brought to the world's attention the existence of what was called the "Hunger Belt". A massive drought had affected the Sahel, the large 5,400-km strip that crosses Africa from west to east, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea. The land was left without water and without a blade of grass, and ...

The Great Green Wall project of the Sahara and Sahel is led by the African Union. The project's purpose is to prevent desertification by planting a wall of trees stretching across the entire Sahel. This is an essential project that can have a great deal on desertification. The project has made some significant progress recently.

The desertification paradigm has a long history in the Sahel, from colonial to modern times. ... Fig. 6.1 The Sahel. Location of the two case studies, the Gourma region in Mali and the. Dantiandou ...

Case study was performed in the Lower San Gong River, Xin Jiang, China as a typical case to study.The degree of the desertification and the relationship between the devastation and the ...

The desertification paradigm has a long history in the Sahel, from colonial to modern times. Despite scientific challenge, it continued to be influential after independence, revived by the dramatic droughts ... systems over the long term, and to assess trends in the ecosystems, beyond their short term variability. Two case studies are developed ...

It has been common practise in remote sensing studies for the Sahel to aggregate data from various Sahelian sites in order to obtain an average relation between rainfall, NPP and Rain Use Efficiency, and to assume these relations to be linear. ... New evidence of desertification from case studies in Northern Burkina Faso. Geografiska Annaler ...

1. PREFACE - THE LEAST DEVELOPED COUNTRIES IN THE SOUTHERN SAHARA DESERT SUFFER FROM DESERTIFICATION. The Sahel region, in a narrow sense, refers to an area along the southern ridges of the Sahara Desert with an average annual rainfall of between 200 and 600 mm (the area extends roughly 400 km north to south and roughly 4000 km east to west) and includes parts of the following six countries ...

Desertification has become one of the most pronounced ecological disasters, affecting arid and semi-arid areas of Nigeria. This phenomenon is more pronounced in the northern region, particularly the eleven frontline states of Nigeria, sharing borders with the Niger Republic. This has been attributed to a range of natural and anthropogenic factors. Rampant felling of trees for fuelwood ...

Case studies of desertification step took place in 73% of the area and by The extent of land degradation was studied in four whole area had become seriously degraded; areas with differing soils and land use; the Kolel, areas with very sparse vegetation (class the Menegou, the Oursi and the Boukouma areas bare surfaces (class 1) remained.

The Sahel is a transition zone between the Sahara Desert in the north and the savannahs in the south. Reasons for desertification. long lasting decline in precipitation over the last 50 years - this is because of the enhanced GHG effect (changes in the grounds surfaces reflective properties and global warming) reasons for desertification.

gal (see Figure 2). The historical impactof drought. 100,000 people were killed by drought in theSahel in 1973; 25% all cattle died or were slaughtered; herds in Mauritania were reduced by 80%; 200,000 people in Niger were entirely dependent on food aid in 1974; ve yearsof drought;in 1991,4.28 million people in the Sahel were facing starvation af.

A. PROVIDE A WALL OF VEGETATION PLANTED IN A LONG LINE ACROSS THE SAHEL TO PROVIDE A BARRIER AGAINST THE ADVANCE OF THE SAHARA DESERT. DIFFICULT TO DO AS ALL COUNTRIES OF THE SAHEL HAVE TO AGREE TO DO THIS. 9. Q. DESERTIFICATION (DEFINITION) A. THE PROCESS OF BECOMING MORE DESERT LIKE. DESERTIFICATION IS ENCOURAGED WHEN THE TOPSOIL IS REMOVED ...

This video showcases desertification in the Sahel region of the Sahara. To read the case study about the desertification of the Sahel region visit Revision World . Revision Videos hierarchy navigation