Policy@Manchester Articles

Expert insight, analysis and comment on key public policy issues

Dark figure of crime: do police-recorded crime statistics serve all areas of Greater Manchester equally?

Unrecorded crime is one of the greatest challenges facing policing today. Ineffective police-recording of crimes can break trust between the Police and public, and lead to failing crime prevention strategies. After facing criticism about crime-data management, Greater Manchester Police (GMP) recently implemented measures aimed at improving its crime-recording system. In this blog, Yongyu Zeng , Angelo Moretti and David Buil-Gil make the case that, whilst welcomed, improvements to crime-reporting systems and processes may still be inaccurate for evidence-based policing in Greater Manchester.

- Police-recorded crime data aggregated at the level of small geographic areas may still be inaccurate for evidence-based policing.

- Targeting police strategies in places where crime may not be frequent, but where residents are more willing to report offences, could result in bias against areas that underreport crime.

- Police forces are therefore recommended to evaluate how their data is influenced by factors other than crime victimisation.

- If police-recorded crime data is used to inform crime occurrence, it is critical to develop statistical techniques to mitigate the inherent bias driven by both ‘recording’ and ‘reporting’ inconsistencies.

Unrecorded crimes – where and unknown to whom?

Police-recorded crime is the number of notifiable crimes reported to and recorded by police forces. These data are used by the police to analyse crime patterns as well as design and evaluate policing strategies. Nevertheless, there is inherent inaccuracy in police-recorded crime data, which is not only dependent on police recording practices but also on victims’ reporting rates. Victims may never discover a crime, or they may be aware of the crime but choose not to report it to police for various reasons. Some crimes do not even have a clear victim, such as drug offences or carrying weapons. Whether victims choose to report a crime to the police is related to their personal circumstances, including their sex, age, ethnicity, education level and employment status. Besides from these individual factors, the area in which one lives in may also affect the likelihood of reporting to the police. Research has shown that, generally, deprived neighbourhoods and areas concentrating a large proportion of immigrants have lower crime reporting rates than middle-class areas.

In fact, the lowest willingness of crime reporting is found among victims who previously committed crimes and live in disadvantaged areas with high crime rates. Closely associated with this is the marked underreporting rate in areas where the citizens’ confidence in policing is low , and where police poorly exercise stop and search practices . In those situations where the crime is indeed reported to police, the incidents could still drop out from the police recording system, and the frequency that this happens vary across police forces . GMP has been under enhanced monitoring as one of the forces who often “ fail victims of crime ”, and several inspections have found gaps in the processes followed to record reported crimes and issues with its crime recording system . While the reform strategy outlined by Chief Constable Watson may solve some of the inaccuracy issues related to ‘reporting’, it is unlikely to fix the inconsistencies in crime ‘reporting’ by victims and witnesses. The bottom line here is that even if all crimes reported to the police are recorded under the new leadership, it is unknown how likely a crime is to be reported to the police in each area.

To pinpoint exactly how inaccuracy affects our understanding of crime patterns in geographic areas, recent research funded by the Manchester Statistical Society showed that maps of police-recorded crime produced at the level of small geographic areas are likely to be affected by unequal crime reporting rates in places. This research, based on a computer-based simulation and the Crime Survey for England and Wales data, assessed the impact of crime data bias on the accuracy of maps of crime obtained from police records. Crime mapping is a geographical analysis technique used to identify crime ‘hot spots’ to inform patrol allocation and crime prevention strategies. Often, the police seek to identify crime hot spots at small geographical areas, such as street segments and dwelling, as it is argued that small area provide a more accurate understanding of crime patterns – ‘smaller is better’. In this experiment, researchers simulated a synthetic dataset of crimes known and unknown to GMP, and found that geographic analyses produced from police records at larger spatial scales, such as neighbourhoods, may show a more valid representation of the geographic distribution of crime than analysis produced for small areas. Findings contradict the ‘smaller is better’ argument. In other words, due to unequal crime reporting rates across places, the inaccuracy of police-recorded crimes is magnified when the data is used to inform crime incidents at small area level.

Policy implications

While it is encouraging to see that the GMP has sought to implement actions to improve crime-recording practices, it is critical to recognise that, even if all reported incidents are logged into police systems, police-recorded crime data is still affected by factors related to victims’ ‘reporting’. The bias caused by the varying levels of reporting in places will be magnified in maps of crime produced at small spatial scales. As a consequence, the police may end up targeting police strategies in places where crime may not be necessarily larger, but where residents are more willing to report offences. On the contrary, the police may fail to identify crime problems in places where crime reporting is lower. Police forces are therefore recommended to take steps to carefully evaluate how their data is influenced by factors other than crime victimisation. If we are to use police-recorded crime data to inform crime occurrence, it is critical to develop statistical techniques to mitigate the inherent bias driven by both ‘recording’ and ‘reporting’ inconsistencies. Police forces, including GMP, should also invest in improving the confidence in the police and the willingness to cooperate with police services especially in those places where underreporting is higher.

Policy@Manchester aims to impact lives globally, nationally and locally through influencing and challenging policymakers with robust research-informed evidence and ideas. Visit our website to find out more, and sign up to our newsletter to keep up to date with our latest news.

About Yongyu Zeng

Yongyu Zeng is a former research associate in criminology at Manchester Metropolitan University. Her research interests cover financial market abuse, financial and organised crime and illicit networks.

About Angelo Moretti

Angelo Moretti is a Lecturer in the Department of Computing and Mathematics at Manchester Metropolitan University. His research interests are in topics related to survey statistics, survey methodology and statistical modelling. In particular, his main expertise is in small area estimation under mixed-effect models.

About David Buil-Gil

David Buil-Gil is a Lecturer in Quantitative Criminology at the University of Manchester, and Academic Lead for Digital Technologies and Crime at the Manchester Centre for Digital Trust and Society. His research interest cover crime data modelling and cybercrime.

Become a contributor

Would you like to write for us on a public policy issue? Get in touch with a member of the team, ask for our editorial guidelines, or access our online training toolkit (UoM login required).

Articles give the views of the author, and are not necessarily those of The University of Manchester.

Policy@Manchester

Unreported crime stats show a fundamental problem can’t be fixed with ‘efficiency’

Teaching Fellow in The School of Applied Social Sciences, Durham University

Disclosure statement

Michael McManus does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Durham University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

A report from Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary has revealed that police in England and Wales fail to record in excess of 800,000 crimes a year. That’s one in five offences ; over one-quarter of all crimes reported to the police.

As a police detective in the 1970s and 1980s, an important part of my role, indeed mission, was to “massage” crime figures, apparently in the interests of effectiveness and efficiency. And while major changes have been pushed through since that time, it seems the same old problem remains.

Back then, high detection and low reporting was an accepted part of the detective’s “craft”. Although the crime report book was available to the uniform department, CID officers strictly monitored what was, and was not recorded in it. Detectives were the guardians of the figures and those figures had to reflect success rather than failure, at all cost.

This occupational culture of manipulated success existed extensively throughout the police at the time. Individual police officers have also been attributed traits such as suspicion, cynicism and machismo . These influenced decisions about whether or not to record allegations of crime from “risky” individuals.

Of course this was not just a culture on the ground. It was an endemic culture which must have received the nod and the wink from the highest officers in the force and officials in the Home Office.

The late 1980s and early 1990s, however, heralded a neo-liberal culture change in policing. Effectiveness and efficiency became the buzzwords as the philosophy of New Public Management took hold. This approach is fundamentally about reducing local autonomy and discretion and handing greater power back to central government.

In the police service, it meant redistributing power away from the autonomous detective through business-like management and accountancy of his/her functions.

Thousands of staff have been shed along the way and citizen volunteers have been increasingly brought in.

But when we hear the details of the report published this week, effectiveness and efficiency are far from the first words that spring to mind. Among the samples included in the report are 37 rape allegations not recorded as a crime. There were 3,842 reported crimes for which offenders were given a caution or a penalty notice, 500 of which should have resulted in a heavier penalty.

On top of that, 3,246 incidents had been recorded and then deemed to be “no crimes” even though in around 20% of cases a crime had indeed been committed. The incidents recorded as “no crimes” included 200 reports of rape and 250 of violent crime. More than 800 of the victims were not told of the decision to record their allegation as “no crime”.

This follows a report just last year from MPs that warned police were fixing crime statistics to meet targets.

And now, in the wake of this latest report, some officers and staff have said performance and other pressures are distorting their crime-recording decisions. A number of forces admitted this. Inspectors were told that pressure to hit crime-reduction targets had the effect of limiting the number of crimes recorded.

Chief Superintendent Irene Curtis, president of the Police Superintendents’ Association, said that recorded crime was a measure of demand on police resources rather than police performance. Chief Constable Jeff Farrar, lead for crime recording at the Association of Chief Police Officers, said: “Pressures from workload and target culture, use of professional judgement in the interests of victims, lack of understanding of recording rules or inadequate supervision can all lead to inaccurate crime recording”.

This will all sound familiar to police officers who served in an earlier cultural period. Indeed, in a statement which had inferences of the police institutional culture of that earlier time, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary said the police should immediately institutionalise the presumption that the victim is to be believed.

It has been argued that because police work involves so many tasks, they can’t all be accomplished effectively. The police instead have to manipulate their appearance to seem effective and efficient.

This report from HMIC appears to confirm the problem. Despite attempts to change the face of the police, they continue to manipulate their image as the guardians of the status quo in British society.

- Crime statistics

Want to write?

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 183,700 academics and researchers from 4,959 institutions.

Register now

Why hate crimes are underreported–and what police departments have to do with it

- Search Search

With more high-profile hate crimes grabbing the national spotlight in recent months, why are such crimes still underreported and undercounted?

The answer is complicated. There are a number of problems collecting data on hate crimes, particularly when it comes to more high-profile incidents, says Jack McDevitt , director of the Institute on Race and Justice at Northeastern. In the 1980s and ’90s, police departments were far more reluctant to classify certain crimes as hate crimes, fearing that it would paint the community as hateful, or as harboring hateful people, he says.

“Local police departments said ‘Oh, we don’t want to call this a hate crime because people wouldn’t want to move to this town,’” McDevitt says.

Those concerns still exist today, McDevitt argues, noting that hate crimes have a “severe and profound impact” on the affected communities, in particular communities of color and immigrant communities. Take the Atlanta-area spa shootings, for example, involving the deaths of six Asian women, which generated an outpouring of solidarity for the Asian community and a movement against anti-Asian racism around the country. Such support reflects the deep trauma associated with hate crimes, McDevitt says.

But, even amid apparently clear examples of bias-motivated crimes in mass killings—which McDevitt says may be on the rise—there is still reluctance on the part of authorities to label such incidents as hate crimes and to formally charge perpetrators, McDevitt says.

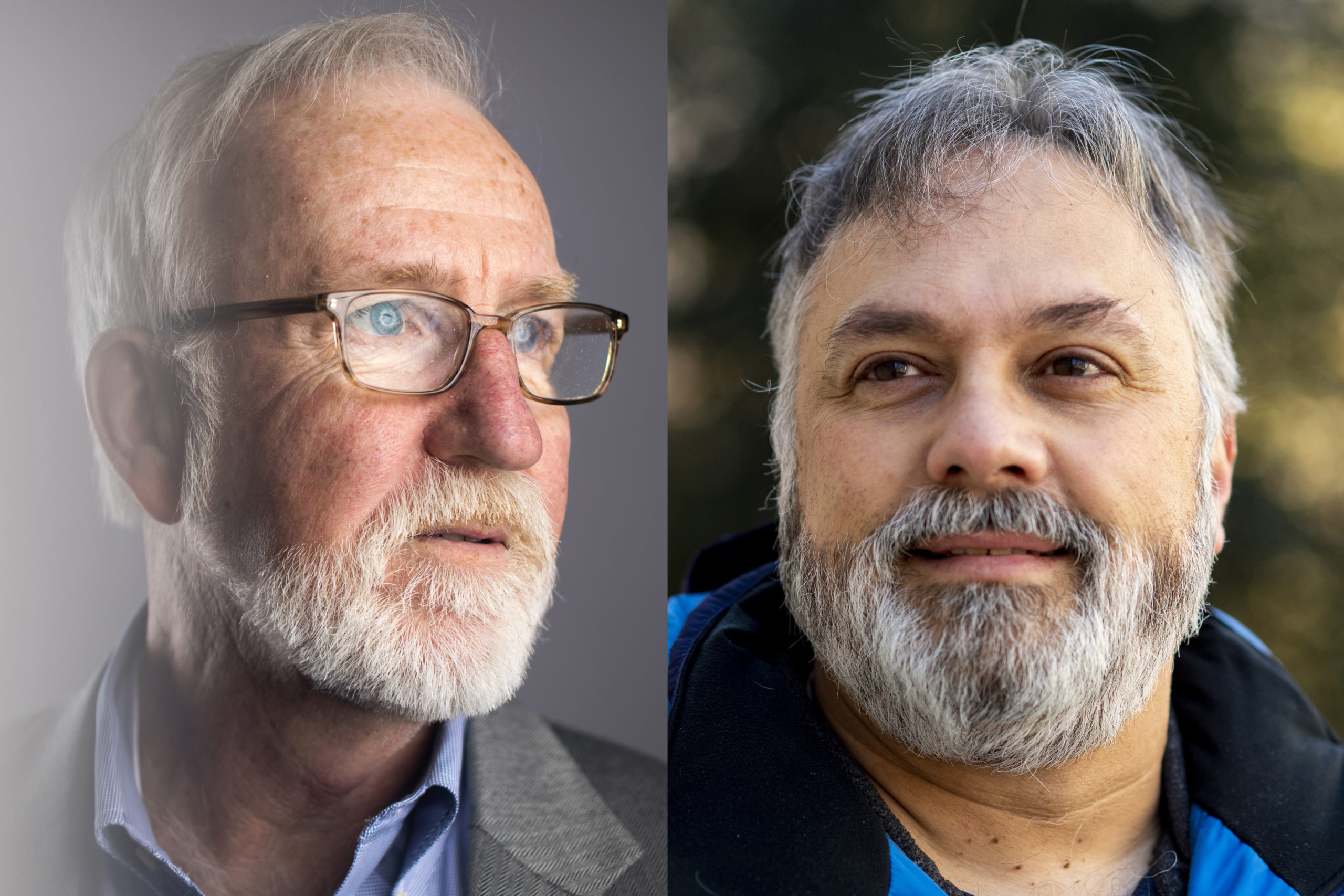

Left, Criminal Justice professor Jack McDevitt. Photo by Adam Glanzman/Northeastern University Right, Carlos Cuevas, professor of criminology and criminal justice and co-director of the violence and justice research lab. Photo by Ruby Wallau/Northeastern University

“There are very few convictions on hate crime charges, and there’s usually a falling off of formal charges” in the criminal legal process, he says.

That’s because prosecutors may decline to pursue hate crime charges because of how they might impact a sentencing outcome. Additionally, proving bias-motivation is difficult , as there are usually numerous motivations underlying criminal conduct, such as “thrill-seeking,” which McDevitt says was at play in roughly 66% of cases of hate crimes analyzed by Northeastern researchers in one study.

Also, many victims do not report their experiences to law enforcement for fear of persecution or reprisal, says Carlos Cuevas , a professor of criminology and criminal justice who co-directs the Violence and Justice Research Lab at Northeastern.

The data collection problems plaguing experts in the field have spurred further efforts to get more information. Cuevas says he and a team of researchers are currently conducting a survey focused primarily on Latinx people, to examine whether they were ever a victim of hate or bias-motivated aggression. This will enable the researchers to get a sense of the frequency of such crimes —and the degree to which they are underreported.

But a lot of the reporting issues and discrepancies rest on the shoulders of police departments, which share local data with the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting program, Cuevas says. It’s at that junction that the statistics representing cases of hate crimes get diluted, he says.

“We’ve worked collaboratively with police departments to get a lot of this data,” Cuevas says. “There seems to be a filtering process between a thing actually happening and that thing ending up in the [FBI/Uniform Crime Reporting program] database.”

Police departments will only report bias-motivated crimes to the Uniform Crime Reporting program if there was an investigation by the law enforcement agency upon which there was an “objective” basis to conclude a hate crime took place, according to the U.S. Justice Department.

There’s been a push by the FBI to raise awareness about the need to report hate crimes and support victims in recent months, which comes amid an uptick in the number of high-profile mass shootings involving victims who were singled out because of some aspect of their race, religion, or sexuality . Police departments have also come under increased scrutiny in the wake of the death of George Floyd, who was killed after a former Minneapolis police officer knelt on his neck for over nine minutes.

Floyd’s death was not ruled a hate crime— Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison argued that “systemic racism, not individual racial motivation” was to blame—but it did spark global protests and calls for police reform that highlighted issues of police bias and systemic racism in departments across the U.S.

“ Of course, those in law enforcement who are racist, homophobic, et cetera, will never be fully be supportive of victims from different groups,” McDevitt says.

But it’s not necessarily their support that victims need, he says. “We need law enforcement to protect the victims .”

Also, Cuevas says more hate crimes need to be fully prosecuted. That’s how communities can start to heal, he says.

“My hope would be that if we see the formal justice system show that this is not OK, you may start to get some traction and make some gains around building trust with those communities,” Cuevas says.

For media inquiries , please contact [email protected] .

Editor's Picks

Is gig work compatible with employment status study finds reclassification benefits both workers and platforms, a biological trigger of early puberty is uncovered by northeastern scientists, jfk was inspired by camelot. now this professor thinks we need fantasy once again to protect us in an ai age, how does the us know that forced labor is happening in china a northeastern supply chain expert weighs in, will robotaxis ever go mainstream self-driving companies have made advancements, but technology is still lacking, expert says, featured stories, .ngn-magazine__shapes {fill: var(--wp--custom--color--emphasize, #000) } .ngn-magazine__arrow {fill: var(--wp--custom--color--accent, #cf2b28) } ngn magazine legendary northeastern hockey goalie has boston three wins away from inaugural pwhl title, .ngn-magazine__shapes {fill: var(--wp--custom--color--emphasize, #000) } .ngn-magazine__arrow {fill: var(--wp--custom--color--accent, #cf2b28) } ngn magazine we’re addicted to ‘true crime’ stories. this class investigates why, northeastern’s cassandra mckenzie recognized by city of boston as ‘trailblazer’ for women in construction, more researchers needed to rid the internet of harmful material, uk communications boss says at northeastern conference.

Recent Stories

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

Why crimes aren’t reported: The role of emotional distress and perceptions of police response

2014 research brief on the role of negative emotionality in the reporting of crimes, by Chad Posick and Michael Singleton, Georgia Southern University and the Scholars Strategy Network.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Scholars Strategy Network, The Journalist's Resource May 13, 2014

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/criminal-justice/crime-unreporting-emotional-distress-police-response/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

From the Scholars Strategy Network , written by Chad Posick and Michael Singleton , Georgia Southern University

As is well known, many crimes are not reported to the police. Why does that happen? Researchers have looked at the kinds of people who are more or less likely to report crimes, and they have also sought to explain different rates of reporting for various kinds of crimes. Now another factor — emotional distress — is getting a closer look. Depending on who is affected and the types of harm caused by different crimes, people can have highly varied emotional responses. The emotions of victims can influence whether they will report crimes and also their perceptions of police responses.

Victims and crimes

To make sense of variations in crime reports to the police, existing research highlights the impact of victims’ individual-level characteristics such as race, sex, and marital status, and also points to the influence of varying degrees of harm caused by different types of crime. Some important findings have emerged from this well-established line of research:

- Older, white females who are married are the kind of victims most likely to report crimes. Compared to youth and minorities, older whites are more likely to trust the police and have confidence in their ability to investigate crimes. Lower rates of reporting by youth and minorities happen because these victims have often previously experienced what they perceive to be unfair police enforcement activities, leading them to distrust the police.

- Police are most likely to be called by victims when serious crimes result in injuries. When someone is seriously hurt by a perpetrator, he or she usually reports the crime or someone does on their behalf. Such victims need and want medical and psychological help — often more than do victims of minor crimes. In serious crimes, therefore, the police become first responders, present shortly after victims begin to cope with harmful experiences.

The role of emotions in reporting to the police

Emotions influence the behavior of victims of crime — and also affect the actions of other people around the victims. One behavior that can be affected is whether the victim reports the crime at all. Social psychologists have learned that negative emotions such as fear and anxiety often prompt people to seek help — in ways ranging from talking with loved ones and looking for professional counseling to contacting the police. It is not surprising, therefore, that victims of crime who experience strong emotional reactions — such as anger, depression, fear, and shock — are more likely to report their experience to the police.

Indeed, victims are more likely to contact the police if they experience multiple forms of emotional distress or especially intense responses. That is true regardless of the sex, race, age or marital status of the crime victim, and regardless of such features of the crime as location, time of day and the degree of injury inflicted on the victim.

Satisfaction with the police

If emotional distress makes reports of crimes to the police more likely, does it also influence how victims perceive their treatment by the police? Additional analyses show that emotions do matter — in complex ways.

- Victims who experience emotional distress are less likely than victims who feel less distress to be satisfied with police actions. In short, emotionally distressed victims are more likely to reach out to the police for help, but they often feel that the police response falls short of meeting their needs.

- However, victims who experience emotional distress are more likely than victims in general to find the police response satisfactory if they already have strong confidence in the police. This finding implies that inspiring general citizen confidence in the police can have a positive effect on the image of the police among people who end up falling victim to emotionally distressing crimes and calling on the police for help.

Take-away lessons

Studies by various scholars, including our team as well as other research teams, underline the importance of the emotions surrounding crime episodes and the impact of underlying citizen views about the legitimacy and effectiveness of the police. Citizen views of the criminal justice system are heavily influenced by individuals’ prior interactions with police and other professionals and their perceptions of the credibility and fairness of those professionals. When crimes happen, the emotional reactions of victims will influence how likely the victims are to report crimes and how likely they are to feel that the police are helpful. In short, the seriousness of the crime and the social characteristics and emotional reactions of the victim matter, but so do already ingrained citizen attitudes. Citizens who already had confidence in the police are likely to appreciate their responses when they are victimized by crime and call the police.

Given these research findings, police departments and officers can take clear-cut steps to enhance citizen confidence and reassure crime victims.

- Departments can establish ongoing programs to engage the community. Citizen review boards boost the trustworthiness of the police by increasing citizen familiarity with police practices and making enforcement activities transparent. In addition, regular dialogues between police and citizens (particularly adolescents) can further understanding of police practices and humanize officers in the eyes of the citizens they are charged to protect.

- Police training can promote emotionally intelligent responses to crime victims. When police officers respond to calls by victims who may well be very emotionally distressed, they can improve their interactions with the victims by displaying empathy. Properly trained officers can learn to recognize typical emotional reactions from victims and become more adept at showing they truly care about helping those hurt by crimes recover in mind and body.

Related research: Chad Posick has authored a related study: “Victimization and Reporting to the Police: The Role of Negative Emotionality,” which appeared in Psychology of Violence in April 2013. Posick and Christina Policastro authored “Victim Injury, Emotional Distress and Satisfaction with the Police: Evidence for a Victim-Centered, Emotionally Based Police Response,” which appeared in the Journal of the Institute of Justice & International Studies the same year.

The authors are members of the Scholars Strategy Network , where this post originally appeared.

Keywords: crime, violence, safety , policing

About The Author

Scholars Strategy Network

One In Five Of All Crimes Not Recorded By Police

The Home Secretary says her concerns about "utterly unacceptable failings in the way police forces record crime" are confirmed.

By Martin Brunt, Crime Correspondent

Monday 17 November 2014 22:43, UK

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

Police are failing to officially record one in five of the crimes reported to them, a damning report has revealed.

An inspection of all 43 forces showed that 800,000 offences a year were not logged as crimes.

Over a quarter of sexual offences were not recorded, while the figure for crimes of violence against the person was even higher at a third.

Home Secretary Theresa May said: "This investigation ... confirms my concern that there have been utterly unacceptable failings in the way police forces have recorded crime."

The report by Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary posed the question: "To what extent can police-recorded crime information be trusted?"

The HMIC's Chief Inspector, Tom Winsor, said: "Failure to properly record crime is indefensible. This is not about numbers and dry statistics; it's about victims and the protection of the public. Victims of crime are being let down."

In a study of 316 rape reports, the inspectors discovered that 37 rapes were not recorded as crimes.

More from UK

Rebecca Joynes: Teacher found guilty of sexual activity with two schoolboys

Devon: Confirmed cases of disease more than double to 46 after parasite found in drinking water

Border Force to stage more strikes at Heathrow Airport during half term

A review of other police statistics showed that 220 rapes were initially recorded, but then wrongly cancelled as "no-crimes" after further investigation. More than 250 violence allegations were similarly downgraded.

Mr Winsor said: "It is particularly important that in cases as serious as rape, these shortcomings are put right as a matter of the greatest urgency. The police should immediately institutionalise the presumption that the victim is to be believed.

"Offenders who should be being pursued by the police for these crimes are not being brought to justice, and their victims are denied services to which they are entitled."

Mr Winsor said he found no one manipulating figures dishonestly, but there was evidence from some forces that "undue performance pressure" had led to the under-recording of some crimes in the past.

A witness who claimed his colleagues had manipulated statistics failed to provide evidence to support his claims, he added.

The report analysed 1,159 decisions where inspectors felt police were wrong to record no crime. It found half the problems were caused by officers who were poorly supervised, and a fifth by staff who had poor knowledge of the accepted recording system.

The HMIC report made 13 recommendations, including a nine-month deadline for the College of Policing to establish a training scheme for those responsible for crime recording in each force.

Mr Winsor said some of the 43 forces in England and Wales were recording crime well, and others had improved since being criticised in an interim report in May.

The best forces identified in the report are West Midlands, Lincolnshire, Staffordshire, South Wales and North Wales.

The worst are Hampshire, Merseyside, Avon & Somerset, Dyfed-Powys and West Yorkshire.

A Dyfed-Powys Police spokesman said: "The suggestion that 30% of total crime is not recorded is potentially misleading as the sample size was very small, less than 73 incidents.

"But we also recognise the recommendations for improvement highlighted in the report."

Adam Pemberton, assistant chief executive of the Victim Support charity, said: "The sheer number of crimes that have been dismissed by the police is alarming."

Shadow policing minister Jack Dromey said: "Victims of crime must be able to access justice and this report shows, in too many cases, this is just not happening.

"Theresa May needs to get a grip on this and make urgent changes to the way the police record crime."

Chief Constable Jeff Farrar, lead for crime recording at the Association of Chief Police Officers, told Sky News the report was a "wake-up call" for police forces.

Live revision! Join us for our free exam revision livestreams Watch now →

Criminology

Reference Library

Collections

- See what's new

- All Resources

- Student Resources

- Assessment Resources

- Teaching Resources

- CPD Courses

- Livestreams

Study notes, videos, interactive activities and more!

Criminology news, insights and enrichment

Currated collections of free resources

Browse resources by topic

- All Criminology Resources

Resource Selections

Currated lists of resources

Unrecorded crime

Unrecorded crime refers to crimes that are reported to the police but are not recorded and therefore unlikely to be investigated. This happens either because of a lack of evidence or because the police do not believe an offence has taken place.

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

Our subjects

- › Criminology

- › Economics

- › Geography

- › Health & Social Care

- › Psychology

- › Sociology

- › Teaching & learning resources

- › Student revision workshops

- › Online student courses

- › CPD for teachers

- › Livestreams

- › Teaching jobs

Boston House, 214 High Street, Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, LS23 6AD Tel: 01937 848885

- › Contact us

- › Terms of use

- › Privacy & cookies

© 2002-2024 Tutor2u Limited. Company Reg no: 04489574. VAT reg no 816865400.

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

- International edition

Thousands of rape reports inaccurately recorded by police

Exclusive: Most forces audited failed to collect accurate figures, meaning investigations were not carried out

Thousands of reports of rape allegations have been inaccurately recorded by the police over the past three years and in some cases never appeared in official figures, the Guardian can reveal.

An analysis shows the vast majority of police forces audited by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS) have failed to collect accurate rape crime figures, resulting in cases going unrecorded and investigations not being carried out, raising the possibility that perpetrators could go on to reoffend. More than one in 10 audited rape reports were found to be incorrect.

The Guardian found complainants with mental health and addiction issues and victims of trafficking were particularly vulnerable to being struck from the record by a number of police forces.

The Guardian reviewed audits of 34 police forces published between August 2016 and July 2019. Only three of them were found to have accurately recorded complaints of rape, according to the audits carried out by HMICFRS. Of the more than 4,900 audited rape reports, 552 were found to be inaccurate.

As every report of rape is not audited it is not possible to know exactly how many are inaccurate, but more than 150,000 rapes were reported to police in that time which means potentially more than 10,000 cases could be affected by inaccuracies.

The inaccuracies in recording can range from incomplete paperwork to not recording a report of rape as a crime but noting it as an incident. This can lead to no investigation being carried out and the accused going on to reoffend. The data also found that a number of forces failed to improve in subsequent inspections, with some getting worse.

Vera Baird, the victims’ commissioner for England and Wales, said it appeared police were failing to investigate reports.

“Where cases are not being recorded as a crime and are dismissed as an incident, that’s a concern because it may be that if the cases were investigated they could result in a prosecution. We know rape is a serial offence so it should be a very considered decision not to pursue something that looks like a rape as a crime of rape,” said Baird.

A spokesman for the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) said victims should have the confidence to report crimes knowing that they would be investigated and support would be provided.

“The rate of rape reporting to police forces has sharply increased since 2014, and we are working to further improve the accuracy of crime reporting, which is governed by detailed counting rules set out by the Home Office. The accurate recording of crime can be influenced by many factors which may not be clear at the beginning of an investigation,” the spokesman added.

A spokesperson for HMICFRS said although recording of sexual offence crimes by police had improved since 2014 they could not definitively say if there had been an improvement in rape recording.

Inspections of police forces also found that vulnerable women, including those with mental health issues, addiction issues, or those reporting rape in a domestic abuse situation or who had been trafficked into prostitution were particularly at risk of having their cases ignored by police in a number of forces.

In one instance a rape was reported to Greater Manchester police but the case was not recorded as a crime. The victim was in a secure mental health facility and officers did not investigate further after staff from the facility assessed that the victim “lacked the capacity to make an informed complaint”. The police later made direct contact with the victim, recorded the crime and it was under investigation in 2018. However, the force was unable to provide further details about the case based on the available information when contacted by the Guardian.

In North Yorkshire in 2017 a report of a victim with mental health issues was not recorded as a rape as “officers did not properly understand how to deal with her ability to consent”, according to an audit of the police force . She subsequently reported being raped again by the same person. The force has since investigated the case although there was no prosecution.

A spokesman for North Yorkshire police said: “It was not possible to bring about a prosecution due to several factors, including the victim declining to engage with the police, which made gathering enough information for a prosecution extremely challenging. Extensive safeguarding measures have been put in place by the police and other organisations to support the victim.”

Louise Ellison, a professor of law at the University of Leeds, has researched outcomes for vulnerable complainants reporting rape. She found that cases involving complainants with mental health issues were significantly less likely to be referred to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS).

Ellison said: “People within the system who support victims of rape will tell you quite candidly that there are women who are coming in through their doors on quite a regular basis reporting rape and their cases are never appropriately investigated by the police.

“Their cases go nowhere because they are automatically assumed to be lacking in credibility. People within the system know this but the frustrating thing is that there doesn’t seem to be any real focus on it.”

The latest figures from the police and CPS reveal that the criminal justice system is failing to keep up with the increase in the number of rapes reported.

Recorded rape has more than doubled since 2013-14 to 58,657 cases in 2018-19. However, police are referring fewer cases for prosecution and the CPS is charging, prosecuting and winning fewer cases . The number of cases resulting in a conviction is lower than it was more than a decade ago.

The Guardian reported in September 2018 that senior staff at the CPS had urged prosecutors to take the “weak cases out of the system”, in order to improve its conviction rate for rape.

A review of the treatment of rape cases within the criminal justice system was announced by the government in March 2019. The review covers the response from a moment a crime is reported to the police until conviction or acquittal in court.

“We are conducting an end-to-end review into the criminal justice response to rape,” a government spokesperson said, “which will help us to better understand the decline in cases reaching the courts and improve our overall response.

“We are taking action to restore public confidence in the justice system by recruiting 20,000 more police, creating extra prison places and reviewing sentencing to make sure violent and sexual offenders are properly punished.”

Methodology

The Guardian scraped all the crime data integrity audits from the HMICFRS website to examine how police forces are recording rape. Once the data was collected it was structured and analysed to find how many forces were inaccurately recording rape reports.

- Rape and sexual assault

Most viewed

US Edition Change

- US election 2024

- US Politics

- UK Politics

- News Videos

- Rugby Union

- Sports Videos

- Photography

- Theatre & Dance

- Culture Videos

- Food & Drink

- Health & Families

- Royal Family

- Electric Vehicles

- Lifestyle Videos

- News & Advice

- Simon Calder

- Inspiration

- City Guides

- Sustainable Travel

- Politics Explained

- News Analysis

- Home & Garden

- Fashion & Beauty

- Travel & Outdoors

- Sports & Fitness

- Sustainable Living

- Climate Videos

- Electric vehicles

- Behind The Headlines

- On The Ground

- Decomplicated

- You Ask The Questions

- Binge Watch

- Travel Smart

- Watch on your TV

- Crosswords & Puzzles

- Most Commented

- Newsletters

- Ask Me Anything

- Virtual Events

Thank you for registering

Please refresh the page or navigate to another page on the site to be automatically logged in Please refresh your browser to be logged in

Unreported rapes: the silent shame

Article bookmarked.

Find your bookmarks in your Independent Premium section, under my profile

For free real time breaking news alerts sent straight to your inbox sign up to our breaking news emails

Sign up to our free breaking news emails, thanks for signing up to the breaking news email.

The devastating scale of sexual violence against women in Britain is exposed today by new research which indicates that the vast majority of victims do not report perpetrators to the police.

One in 10 women has been raped, and more than a third subjected to sexual assault, according to a major survey, which also highlights just how frightened women are of not being believed. More than 80 per cent of the 1,600 respondents said they did not report their assault to the police, while 29 per cent said they told nobody – not even a friend or family member – of their ordeal.

Negative social attitudes to rape and sexual assault victims play a big part in the reluctance of women to come forward, the survey by Mumsnet suggests. Nearly three-quarters (70 per cent) of respondents feel the media is unsympathetic to women who report rape, while more than half say the same is true of the legal system and society in general.

The findings come as the social networking site launches a campaign to dispel the myths surrounding sexual violence, which it says stop victims from accessing support and justice. The week-long "We Believe You" campaign is backed by Rape Crisis, Barnardo's and the End Violence Against Women coalition.

Fear of being blamed, because of their clothes or alcohol intake or for staying with an abusive partner, means more than half of the women surveyed in February and March 2012 said they would be too embarrassed or ashamed to report the crime. The stubbornly low conviction rates still put off 68 per cent of victims from going to the police, but perhaps even more surprising is the fact 29 per cent said they did not tell anyone, not even friends or family, about the rape, while 53 per cent said they would be reluctant to do so because of shame or embarrassment. Mumsnet wants to convey that every rape is as serious as the next, despite the contrary and controversial assertion by Justice Minister Ken Clarke last year.

Justine Roberts, co-founder of Mumsnet, said: "It is shocking and unacceptable that this number of women have been raped and sexually assaulted. But the stand-out fact is that so few would report it to officials or even to loved ones, because of the general perception society is unsympathetic. If our campaign can dispel the myths and help women realise how commonplace it is, then some may feel more emboldened to get help."

Of the women who reported being sexually attacked or raped in the survey, almost a quarter said the crime had happened four times or more, and in two-thirds of cases the perpetrator was someone the victim knew.

Home Office figures indicate more than one in five rapes are reported as perpetrated by partners or ex-partners. Yet the belief that rapes happen outside, in dark alley ways, to women scantily dressed, is among the most pervasive, and harmful. It means women raped at home do not identify the experience as rape, or report it.

One Mumsnet user wrote: "It makes people view rapists as monsters (which is true) and therefore the man who lives over the road or the man who works in accounting or your husband's friend couldn't possibly be rapists (which unfortunately isn't true) because they're normal decent human beings."

However, the Government is trying to restrict legal aid access for some domestic violence victims as part of its proposals to cut the annual bill by £350m.

Last week The Independent revealed funding from local authorities to organisations working with domestic violence and sexual abuse victims fell from £7.8m in 2010-11 to £5.4m this year.

A spokeswoman for the Ministry of Justice said: "The Government has ring-fenced nearly £40m over the next three years for specialist local domestic and sexual violence support services."

Case study: 'My life was a pattern of rapes, sorrys and treats'

Mary (not her real name) suffered serious abuse at the hands of her former partner. Now 37, she is happily married and lives in the West Midlands

"I met the man of my dreams when I was 23 and my daughter was two years old. He was handsome, educated and had a gorgeous smile.

Then one night he asked me if I fancied one of his mates. I didn't realise at first what the plan was.

It happened so fast and I was so out of it that after a while and trying to move away from him, I just lay there and let his friend rape me.

The next time he [my boyfriend] raped me was a few months later. Everything hurt, my legs were bruised with finger marks, I was bleeding, he'd torn me with the force.

The months went by, we followed a regular pattern, clubbing, parties, new friends, rape, treats and beatings. He'd always 'make it up to me' with expensive presents and flowers and a million 'sorrys'.

I dropped two stone and my parents were so worried, I'd hardly seen them or any friends. I couldn't tell anyone about my life, I was scared that they would tell me to leave him. I thought that I'd be the one to change him. If I loved him enough that he'd stop hurting me.

One night he started to shout at my daughter because she was crying. Then he lunged towards her in a real rage. I knew we'd die or be seriously injured if we didn't leave.

We lived in the hostel for three long months before we were housed by a housing association.

I remember driving past the refuge a few years ago and seeing it reduced to a pile of rubble. I find the fact that cuts are to be made really worrying. The thought of women and children not having that resource frightens me. What will they do if there are no counsellors to talk to? I found it incredibly hard to talk about my ordeal and even now, I can't say certain things out loud.

One thing I'll take with me from my time with my ex is that he used to say 'First you f*** their body, then you f*** their mind' and he would actively seek out single mothers to 'rescue'. I found out after I'd left that he actually planned to lure women into his web of lies and beatings.

It has taken me a very long time to come to terms with my ordeal, to trust a man again. Even now, there are days when I wait for the bubble to burst and everything in my life to fall apart."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

New to The Independent?

Or if you would prefer:

Want an ad-free experience?

Hi {{indy.fullName}}

- My Independent Premium

- Account details

- Help centre

- Sustainability

- Client Login

- Built Environment

- Energy & Natural Resources

- Financial Services

- Government & Public Sector

- Technology, Media & Communications

Legal Services

- Commercial, Regulatory & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment and Pensions

- Finance and Restructuring

- Real Estate

- Tax & Private Capital

- India Group

Legal Operations

- Contracts Management

- Cyber Incident Services

- Legal Analytics

- Legal Operations & Consulting

- Litigation and Investigations

Business Services

- Claims Management & Adjusting

- Corporate Governance & Compliance

- DWF Chambers

- Regulatory Consulting

- Class Actions

- Economic Crime & Fraud Hub

- Sustainable Business & ESG

- Data Protection and Cyber Security

- News and Insights

- Reports and Publications

- News and Press

- DWF onDemand

- Brave New Law

- DWF Link: Business leaders of the future

- Consumer Duty Hub

- Press Releases

- Cybercrimes are going unreported

ONS Crime data: Cybercrimes are going unreported

Richard Hall, Senior Associate in the Data Protection and Cyber Security team at DWF comments on the ONS bulletin for Crime in England and Wales for the year ending September 2020.

Related Sectors

- Technology, Media & Communications

Related Services

- Breaches and Incident Response

- Data and Cyber Disputes

- Data, Cyber Risk and Compliance

Further Reading

DWF, the global provider of integrated legal and business services, has signed on to the AI Code of Conduct for the insurance claims industry.

In this webinar, DWF's grant funding experts, Sean Caldwell and Claira Rodden, delivered an overview of the key elements of grant funding agreements.

The Competition and Markets Authority ("CMA") is seeking feedback from interested parties on the Public Transport Ticketing Schemes Block Exemption, which exempts certain forms of agreements between transport operators from the prohibition on anticompetitive agreements in the Competition Act 1998. Responses will inform its decision on whether to extend or replace the Block Exemption before its expiry date in February 2026.

'I thought I was going to die' in homophobic attack

- Published 9 October 2020

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

"I shouldn't be scared to walk down the street"

Two years ago, 50-year-old Tommy Barwick was attacked after London's Pride parade. He was left requiring the use of a wheelchair.

"I heard shouting behind me that was homophobic. Then I was hit. I felt my back crack and I fell to the floor. They stamped on my back," said Tommy - and they swore at him as he lay on the ground and told him he "deserved it".

"The pain - it was so awful. I was in and out of consciousness. I thought I was going to die, I really did. I thought I was never going to see my daughter again," he said, recalling the traumatic experience.

This homophobic assault - an attack based on prejudice against LGBT people - was part of a surge in such cases over the past five years.

LGBT people 'still suffering' during lockdown

Homophobic hate crimes increase in London

New figures obtained by the BBC from all 45 police forces in the UK reveal that the number of reported homophobic hate crime cases almost trebled - from 6,655 in 2014-15, the year same sex marriage became legal in England, to 18,465 in 2019-20.

In the past year, there has been a 20% rise in reports to police of homophobic hate crime, according to the data which was obtained through Freedom of Information requests.

Police forces said this increase could reflect a greater confidence in reporting such crimes.

But LGBT charities said they had seen a rise in people experiencing such hate crimes and this could be just the "tip of the iceberg".

'Financially ruined'

Tommy Barwick's attackers were never found

The attack has left Tommy in pain - and it meant losing his livelihood because he was no longer able to run the shop he owned.

"My life was taken from me. I can't play with my daughter like I used to. I don't sleep. I have flashbacks. I have nightmares. I'm financially ruined," he told the BBC.

But his attackers were never found. The police force dealing with his case has apologised for the way that his case was handled, and the BBC has seen the letter.

"I wanted to reiterate my apology for the lack of face-to-face contact with any officer after your attack. It is clear that the service you received left you feeling let down, and this is not acceptable," he was told by the police.

But Tommy doesn't think that's good enough.

"They've told me that they handled my case wrong, and that now they'll train their officers better. But that doesn't help me. I haven't got a lot of trust in them anymore."

A hate crime is a criminal offence that is motivated by "hostility or prejudice" towards someone because of factors such as their race or religion or their sexual orientation.

It means prosecutors can apply to the court to increase the offender's sentence.

Such cases of hate crimes based on sexual orientation seem to have been increasing in many areas.

In West Yorkshire, such crimes rose from 161 in 2014-15 to 1,093 in 2019-20

Merseyside cases rose from 65 to 678 in the same years

Essex from 97 to 533

London's Metropolitan Police saw reports rise from 1,549 to 3,013

Greater Manchester Police saw reports rise from 423 to 1,231

Hertfordshire police recorded 176 such crimes in 2018-19, which rose to 495 in 2019-2020

Northamptonshire police recorded 82 and 177 in same periods

Charlie Graham, a 21-year-old from Sunderland, says homophobic hate crime is just a part of life.

Charlie has been attacked several times over the past three years - and was left beaten and covered in blood after the most recent incident a few months ago.

"I did go downhill after the first two of three times. Like really downhill, to the point where I was in a hole and I didn't want to come out of it," Charlie said about the impacts of the attacks.

"Suicidal thoughts, drinking, not giving a care in the world."

As with Tommy's experience, Charlie's attackers were never found. The police looking into the case apologised.

Even after going through such horrific experiences, Charlie refuses to change any way of life, and said nobody else should have to either.

"I could come up with lots of examples where we are getting it right," said Deputy Chief Constable Julie Cooke, the lead for LGBT at the National Police Chiefs' Council.

"But I absolutely take seriously where we don't. And we need to make sure that we improve and learn from those times when we've not done it right," she said.

"It is hugely underreported. And so please do come forward. And if you're not getting the right response that you would expect, please make sure that you tell us about that."

But Nancy Kelley, chief executive of Stonewall, the LGBT charity, doesn't think the rise is just down to better reporting.

"We are definitely seeing a real increase in people reaching out for help across all of the LGBT organisations," she said.

"So we are very concerned that this is a real rise in people who are being attacked because of who they are and who they love.

"We know that 80% of LGBT people don't report hate crimes. So this is really just the tip of the iceberg.

"One of the key steps to changing this is making it visible, and by standing up and saying that we shouldn't have to experience this kind of hate and abuse."

Follow Ben Hunte on Twitter , external and Instagram , external .

- Published 10 January 2020

- Published 17 May 2020

Ripple effect: The social consequences of the ‘everyday’ hate crime

Hate crime can have a long-lasting and devastating effect on victims, but what about the impact on the wider community? New research by Monash University’s Researcher Chloe Keel, Prof Rebecca Wickes and lecturer Kathryn Benier found that ‘secondary exposure’ to hate crime could actually increase negative sentiments towards migrant groups and lead to more boundaries between sections of the community.

Hate crimes towards specific ethnic, racial or religious groups are increasing in Australia. These kinds of crimes are defined here as “unlawful, violent, destructive or threatening conduct in which the perpetrator is motivated by prejudice towards the victim’s social group”. They tend to occur more often near the home of the victim.

We wanted to know if incidents of hate crime in a local neighbourhood led to empathy for diversity and difference, or hostility? What effect does it have on witnesses and bystanders?

In Victoria, Australia, we have seen some political rhetoric identify particular ethnic, racial or religious migrant groups as unable or unwilling to integrate. It’s unsurprising that hateful incidents are increasing in communities where migrants live and work.

Our new research focused on the nature of hate crime, but also the message that hate events send to others living in the community.

As we know from the broader research, hate crime harms victims, but also those who share the victim’s ‘identity’. It may also be harmful for the broader community: “Yet, few studies focus on the ripple effects of hate. This paper examines how secondary exposure to hate crime in the neighbourhood, through witnessing or hearing about hate crime, influences individual perceptions of ethnic minorities.”

Second-hand knowledge more likely

An individual’s knowledge of hate crime is likely second-hand. In our research, we make a clear distinction between witnessing a hate crime on one hand, and hearing about a hate crime after the event through second-hand sources.

These indirect reports about crime where one lives can often be exaggerated and unreliable – but can also affect individual perceptions and actions. Secondary exposure to hate crime (as witness or bystander) sends a message beyond the target group, reaching others living in the area.

We found in communities where ethnic minorities are targeted, the blame appears to be attributed to them. Hearing about hate crime can cause trepidation, and is directly related to “anticipating” social rejection if they approach someone who’s different to them.

Additionally, people who reported second-hand information about hate crime were more likely to foster negative beliefs about migrants, and tended to try to exclude new migrants from their communities. They would also be reluctant to move into a neighbourhood where new migrants lived.

Media fuelled the fire

In Melbourne, the racialised crime discourse leading up to the 2018 Victorian state election with inflammatory media attention on so-called ‘African gangs’ saw a rise in hostility towards African-Australians.

Messages of exclusion – such as violence or threats towards a certain group – are overwhelmingly harmful for both the direct and indirect targets of hate crime, yet they can sometimes lead to positive community actions.

Monash University and the Centre for Multicultural Youth’s report Don’t Drag Me Into This found South Sudanese Australians were subject to increased racial abuse in public settings.

More recently, during the COVID-19 pandemic, there’s been a rise in anti-Asian sentiment. A report by researchers at the Australian National University found more than eight in 10 Asian-Australians experienced discrimination in 2020 .

This rise in ‘everyday’ hate crime has serious consequences for social cohesion and inclusion in suburbs. It can socially isolate victims and their broader social group, because victims report feelings of marginalisation and often withdraw, while simultaneously creating stronger bonds within the targeted social group.

Hate crime occurring in neighbourhoods where people live has the potential to damage social processes that allow the locals to create a space that welcomes diversity.

In the places people live, we think this positivity towards diversity, attachment to the place in which one lives, and social cohesion in the suburbs protect against hate, and reduce incidents of hate crime.

Entrenching the social boundaries

Social boundaries in neighbourhoods appear to be further entrenched by witnessing hate crimes, we found. Residents are more likely to express anger towards ethnic minorities. This could lead to other barriers between neighbours that do not explicitly seek to exclude migrants, but may increase a sense of defensiveness between groups.

Pre-existing political orientations are important in understanding this relationship, as political affiliation with progressive parties increases positive sentiments, attitudes and actions towards migrants.

People are more likely to believe local crime stories that align with their existing understandings of the world, particularly when they don’t have reliable facts.

Those who want to limit migration are likely primed to feel more hostile towards migrants when hearing about hate crime. Our paper shows that those who witness hate crime express greater anger towards ethnic minorities.

For those with a political leaning in favour of migration, rumours and tales of ethnically, racially and religiously-motivated hate crime might not lead to harmful views and exclusionary actions. Yet those who want to limit migration are likely primed to feel more hostile towards migrants when hearing about hate crime.

Our paper shows that those who witness hate crime express greater anger towards ethnic minorities. Those who rely on second-hand information about hate crime in the community are more likely to anticipate rejection on the basis of their ethnicity, hold negative attitudes towards ethnic migrants, and intend to take actions to exclude new migrants from their communities when compared with those who don’t have such information.

We write that these findings “have implications for community cohesion in multi-ethnic neighbourhoods”.

Large-scale crime events involving ethnicity or religion are different. They can evoke empathy for the victims, and encourage positive community action to stand up against hate.

The Christchurch mosque massacre in New Zealand led to international condemnation, and the image of Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern comforting a Muslim woman while wearing a headscarf was seen worldwide as a symbol of unity.

So, through prominent incidents of hate we see international mobilisation for peace, compassion and unity.

Giving rise to negative sentiments

But this is not the case with more localised incidents. Largely, the message generates negative emotions about migrant groups, which could lead to fragmented social relations and more boundaries between groups in the community.

Interventions in the hate crimes can also be affected – if residents with secondary knowledge of hate crime either spread negativity about diversity, or endorse exclusion of new migrants, they’re unlikely to step in as bystanders, thereby not reducing the number of hate-fuelled incidents in the future.

About the authors

This article is republished with permission from the Monash Lens, under a creative commons licence; the original can be read here .

Picture © Wachiwit /Shutterstock.com

You must be registered and logged in to post a comment

Please log in or register, search our website..

Please wait...

Privacy Overview

Are you OK with cookies?

We use small files called ‘cookies’ on ccrc.gov.uk. Some are essential to make the site work, some help us to understand how we can improve your experience, and some are set by third parties. You can choose to turn off the non-essential cookies. Which cookies are you happy for us to use?

Choose which cookies we use

Marketing cookies, google analytics.

We use Google Analytics to measure how you use the website so we can improve it based on user needs. We do not allow Google Analytics to use or share the data about how you use this site.

Google Analytics 4

Third-party cookies, video streaming.

We have no control over cookies set by third parties. You can turn them off, but not through us.

Social Media

If you share a link to a page, the service you share it on (for example, Facebook) may set a cookie.

Essential cookies

These cookies will always need to be on because they make our site work.

Logged in users

- About the Criminal Cases Review Commission

- Facts and figures

- Our powers and practices

- Casework policies

- Annual Reports and other publications

Case studies

- Board minutes

- Victims of crime

Hear stories direct from the people that have won their appeals with us and more.

Overturning miscarriages of justice – Winston Trew

Making legal history with post office cases, stockwell six and discredited policing, asylum, immigration and victims of human trafficking, ahmed mohammed sexual assault case uncovered new dna.

- Find Flashcards

- Why It Works

- Tutors & resellers

- Content partnerships

- Teachers & professors

- Employee training

Brainscape's Knowledge Genome TM

Entrance exams, professional certifications.

- Foreign Languages

- Medical & Nursing

Humanities & Social Studies

Mathematics, health & fitness, business & finance, technology & engineering, food & beverage, random knowledge, see full index.

Criminology Unit 1 > 1.3 Consequences of unreported crime > Flashcards

1.3 Consequences of unreported crime Flashcards

How many consequences of crime are there?

What are the 8 possible consequences of crime?

- Ripple Effect

- Decriminalisation

- Police Prioritisation

- Unrecorded Crime

- Cultural Change

- Legal Change

- Procedural Change

What is the Ripple Effect?

This is when the impact of crime spreads beyond the immediate victim and further affects their family/friends, or the wider community.

What is one example of the Ripple Effect?

Domestic abusers were often abused or witnessed abuse during their childhood, therefore affecting their actions and behaviours in the future because the abuse they endured was not reported and therefore saw it as acceptable.

How do cultural differences affect crime?

In some cultures, some crimes may be seen as accepted, therefore making the crime under-reported and not recognised.

What happened to Kristy Bamu?

- Was brutally beaten and killed by his sister because she believed that he was possessed by ‘bad spirits’ and wanted to protect the other children within the flat.

- Kristy suffered from 130 injuries.

What is a negative impact of the Kristy Bamu case?

- Traumatised family and fear the idea of witchcraft.

What is a positive impact of the Kristy Bamu case?

- Raises awareness when reported.

What is decriminalisation?

When the public lack concern for a crime, it tends to become decriminalised (not seen as a crime) within the community.

What types of crimes tend to be decriminalised?

Victimless crimes such as:

- Prostitution

- Underage drinking

What are some reasons for the decriminalisation of cannabis in Britain?

- Less harmful than alcohol or cigarettes

- Can earn lots of money of taxes are placed on it

- THC and CBD can reduce cancer growth

- Other medical benefits

What are some reasons against the decriminalisation of cannabis in Britain?

- Young people perceive it as a ‘safe’ drug

- Becomes ‘normalised’ and can affect mental health

- Can trigger schizophrenia in people who have genetic symptoms

- Can be a ‘gateway’ drug

What is police prioritisation?

When the police choose to prioritise certain crimes over others, causing other crimes to not be prioritised and not investigated.

Give one example of an issue that is being prioritised by the police.

Hate crime.

Why are the police prioritising hate crimes?

- Could impact Britain’s future as a tolerant country.

- Children are being verbally abused.

- Some people fear leaving their house.

- Some politicians are creating ‘hostile environments’.

- Prejudice in media can be mirrored within the general public.

What is a positive of police prioritisation?

Victims of the prioritised crime feel more comfortable reporting the crime.

What is a negative of police prioritisation?

Victims of other crimes may feel as if nothing will be done for them if they report the crime.

What is unrecorded crime?

This is where a crime is reported, however, the police do not actually record the incident.

What are some reasons as to why crime can go unrecorded?

- Lack of evidence

- Lack of resources

- Low profile crimes

- Might not be considered a crime by law

- Lack of public concern

- Police officer bias

- The crime may not be as significant as another crime

Criminology Unit 1 (6 decks)

- 1.1 Analysis of different types of crime

- 1.2 Reasons behind reporting crimes

- 1.3 Consequences of unreported crime

- 1.4 Media representation of crime

- 1.5 Impact of media on public view of crime

- 1.6 Methods of collecting statistics of crime

- Corporate Training

- Teachers & Schools

- Android App

- Help Center

- Law Education

- All Subjects A-Z

- All Certified Classes

- Earn Money!

Will Trump Testify At Hush Money Trial? Here’s Why Some Lawyers Think It’s Unlikely.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Former President Donald Trump’s lawyers are expected to start presenting their defense in his criminal trial next week after prosecutors rest their case, but it still remains to be seen whether the ex-president will take the stand and testify himself—though Trump has wavered on the issue, and legal experts largely believe it would be an unwise move.

Former President Donald Trump returns to the courtroom after a short break during his hush money ... [+] trial on May 14 in New York City.

The defense is expected to start presenting its case next week, after prosecutors said Tuesday that ex-Trump attorney Michael Cohen , who will take the stand for a third day on Thursday, will be their final witness.

Trump’s attorneys aren’t expected to call many witnesses—if any—with attorney Todd Blanche telling the judge Tuesday they have one expert witness they may call, but that’s the only one they have set as of now.

Blanche said Tuesday it’s still unclear if Trump will testify, answering “no” when Judge Juan Merchan asked if the attorney had any “indication” of whether Trump would testify or if any “determination” had been made on the issue.

Trump publicly committed to testifying when the trial first got underway, telling reporters, “All I can do is tell the truth. And the truth is that there’s no case” just before the trial began.

Trump became more noncommittal in an April 26 interview with Newsmax, where he said only that he would testify “if it’s necessary”—and the ex-president has not committed to testifying since, though he did falsely claim a gag order against him barred him from taking the stand, which Merchan swiftly clarified was not the case.

Trump spokesperson Steven Cheung has not yet responded to a request for comment.

Get Forbes Breaking News Text Alerts: We’re launching text message alerts so you'll always know the biggest stories shaping the day’s headlines. Text “Alerts” to (201) 335-0739 or sign up here .

It’s common for defendants not to testify in criminal trials, with many defense attorneys believing the risk of a defendant harming their own case outweighs the benefits. When the trial began last month, Merchan reminded jurors Trump has a right not to testify, and if he chooses not to take the witness stand, they can’t hold it against him.

Should Trump Testify?

While it’s still up in the air whether Trump will testify, legal experts suggest doing so would hurt the ex-president’s case. “It would be suicide for” Trump to testify, left-leaning attorney Norm Eisen said on CNN Tuesday, arguing there’s “no way” his lawyers would allow him to take the stand. Trump’s former attorney Tim Parlatore said the same on CNN Tuesday, telling Kaitlan Collins that he “personally would suggest that he probably should not” testify. Both Eisen and Parlatore suggested doing so would hurt Trump’s case, with Parlatore arguing it would “significantly increase” Trump’s chances of conviction because “if the jury disbelieves him on anything, however small, that’s something they’re gonna hold against him and be much more likely to convict.” If Trump is convicted, Eisen suggested taking the stand could also lead to a more severe punishment, arguing that if Merchan believes Trump may have lied under oath, “it virtually ensures a sentence of incarceration.” While legal experts suggest Trump’s lawyers are near certain to prefer their client stay off the stand, however, they also note the ex-president has a history of not listening to his attorneys.

What To Watch For

Any decision on whether Trump will take the stand is likely to be made at the last minute, legal experts have noted, with Parlatore saying the decision will be made “down to the wire” based on whether it’s “worth taking the risk,” and former federal prosecutor Joyce Vance noting in April it’s “unlikely” Trump’s lawyers will decide “until the moment is close at hand.” If Trump’s lawyers don’t take very long to present their defense—whether or not Trump testifies—it’s possible the case could go to the jury as soon as next week. The prosecution is likely to rest its case Thursday or on Monday—the court will be off on Friday for Trump’s son Barron Trump’s graduation—depending on how long Cohen’s testimony runs.

Surprising Fact

While this case marks Trump’s first criminal trial, the ex-president has recently taken the stand at several of his recent civil trials, testifying about defamation allegations brought against him by writer E. Jean Carroll and the fraud allegations brought against him and his company. Neither testimony appeared to help his case, as he was found liable in both cases and ordered to pay $88.3 million and $454.2 million, respectively. In his order finding Trump and his co-defendants liable in the fraud case , Judge Arthur Engoron argued Trump “severely compromised his credibility” when testifying, noting the ex-president “rarely responded to the questions asked, and he frequently interjected long, irrelevant speeches on issues far beyond the scope of the trial.”

Key Background

Trump faces 34 felony charges of falsifying business records in his Manhattan trial, which is one of four criminal cases that’s been brought against the ex-president. The charges stem from a $130,000 payment Cohen made to adult film star Stormy Daniels in the days before the 2016 election in order to cover up her allegations of having an affair with Trump. Trump then allegedly reimbursed Cohen for the payment—paying him $420,000 after adding in other expenses and enough money to cover taxes—which were paid through a series of reimbursement checks throughout 2017. Prosecutors allege those reimbursements were handled through the Trump Organization and falsely labeled as being for legal services, which Trump has denied, as his lawyers have claimed the payments were correctly labeled and tried to distance Trump from the reimbursement scheme. Trump has pleaded not guilty to the charges against him—as well as in his other three cases—decrying the case as a politically motivated “witch hunt” designed to hurt his campaign. The trial, which has been ongoing since mid-April, has included multiple witnesses tying Trump to the hush money scheme, with Cohen directly testifying that Trump approved the Daniels payment and was involved with the reimbursement scheme. As the criminal defendant, Trump has been required to be present in the courtroom every day of the trial—though media reports suggest he has regularly dozed off during the proceedings.

Further Reading

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Join The Conversation

One Community. Many Voices. Create a free account to share your thoughts.

Forbes Community Guidelines

Our community is about connecting people through open and thoughtful conversations. We want our readers to share their views and exchange ideas and facts in a safe space.

In order to do so, please follow the posting rules in our site's Terms of Service. We've summarized some of those key rules below. Simply put, keep it civil.

Your post will be rejected if we notice that it seems to contain:

- False or intentionally out-of-context or misleading information

- Insults, profanity, incoherent, obscene or inflammatory language or threats of any kind

- Attacks on the identity of other commenters or the article's author

- Content that otherwise violates our site's terms.

User accounts will be blocked if we notice or believe that users are engaged in:

- Continuous attempts to re-post comments that have been previously moderated/rejected

- Racist, sexist, homophobic or other discriminatory comments

- Attempts or tactics that put the site security at risk

- Actions that otherwise violate our site's terms.

So, how can you be a power user?

- Stay on topic and share your insights

- Feel free to be clear and thoughtful to get your point across

- ‘Like’ or ‘Dislike’ to show your point of view.

- Protect your community.

- Use the report tool to alert us when someone breaks the rules.