- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- ENGLISH POETRY

- ENGLISH NOVELS

- ENGLISH DRAMAS

- INDIAN ENGLISH LITERATURE

- _Indian English Poetry

- _Indian English Novels

- _ESSAYS IN CRITICISM

- _SHORT STORIES

- _POETS AND AUTHORS

Poem The Education of Nature, Summary and Critical Appreciation

Introduction of the poem.

‘The Education of Nature’ is a part of the collection, he wrote under the title ‘Poems of Imagination’ . This poem has another title, ‘Three Years She Grew in Sun and Shower’ . It was composed in 1799 in the Hartz forest during Wordsworth stay in Germany. It was published in the second edition of ‘Lyrical Ballads’ in 1800. This poem belongs to a group of poems called ‘Lucy Poems’ . It was given the title ‘The Education of Nature’ , in Palgrave's ‘Golden Treasury’ . The poem suggests an underlying influence of Rousseau, the French philosopher, who believed that Nature has the power to educate the mind of man.

This poem successfully depicts the educative impact of imparting perfection and purity that is extended through the effect of Nature on the life and behaviour of a young girl Lucy. Palgrave titled it so partly because the theme of the poem is the influence of Nature on the build - up of human body and mind and partly because Wordsworth was greatly impressed by Rousseau, who regarded Nature as ultimate teacher.

The poem upholds Wordsworth's beliefs that a spirit of joy runs through all objects and creatures of Nature. And also that an all pervading Divine Spirit is present in Nature and it has a will of its own. The poem successfully depicts the educative impact of imparting perfection and purity that is extended through the effect of Nature on life and behaviour of a young girl Lucy.

Nature itself is the chief speaker and gives a detailed description of the beauty and innocence of the little girl Lucy. This girl, as described in this poem, was a young and beautiful girl, very dear to the poet. The identity of Lucy has not been established, i.e., who that child was.

The poet tells only that Lucy was born and grew up in the lap of Nature. She lived through all sorts of weather like a wild plant. She was the loveliest plant.

All that we learn is her perfect and pure portrayal of the brilliance of her childhood. She is so exquisite in every way that Nature can't conceive of her as a separate entity. Nature has a will of her own. It decides herself to take Lucy away from this world, by adopting her as her own child and educate her in her way. She will be both law and impulse to her, i.e., law. It will check her from going astray or doing anything evil and as an impulse; it would inspire her to do noble deeds.

For, Nature wants to be completely bound in closeness and fellowship with the little child, Lucy also becomes Nature's symbol of perfection. According to the poet, placing a child in Nature's care is enough education for him / her. Unfortunately Lucy's life comes to an abrupt and early end. So intense is Nature's love for her that after her death, Nature itself seems to mourn in deep despair for the loss of Lucy's life. Even after death, Lucy's presence fills the hills and valleys with ultimate joy.

The poem presents the perfection of mind and form that Nature can bestow on a mortal, in the person of Lucy. Thus there is an autobiographical element in the poem.

Summary of the Poem:

The poem illustrates very beautifully Wordsworth's conception of Nature. To him, God is everywhere, manifested in the harmony of Nature and he felt deeply the kinship between Nature and the soul of mankind. This poem, i.e., one of the Lucy poems, shows Rousseau's influence, to some extent, on Wordsworth who believed that Nature is our teacher. That's why, he personifies nature in this poem and invests natural objects with a living, thinking and feeling power.

Lucy is Nature's own child, her darling. She grows up in the midst of Nature's magnificence for three years. She lives through all sorts of weather like a wild plant. Nature declares her to be the loveliest flower on earth that was ever grown. She proposes to undertake the responsibility of educating Lucy according to her own way and liking. She will be law and impulse to the girl. She'll let Lucy enjoy her freedom and have her heart's desire. She'll leap with joy like a fawn. But at the same time, she'll also learn to discipline herself. As law, Nature will prevent her from evil and as impulse; she'll inspire Lucy to noble actions. Lucy will have the freedom to roam amidst the rocks and plains; on the earth and in the sky; in the glade and in the bower.

And everywhere she will experience the presence of the all-pervading Divine spirit present in Nature and she will keep watch over Lucy. Lucy will learn sportiveness from the fawn. She would be as sprightly as the fawn playing among the hills and lawns. The inanimate objects of Nature would teach her the special value of silence and tranquility. The floating clouds would lend elegance to her movements, the willow trees would lend her its flexibility. She will not fail to see the beauty even in the agitation of the storm that would mould the young girl's form. She'll learn grace which will mould her maiden's form into a perfect mature woman.

Lucy would learn to love stars in the dark midnight sky. She'll visit many quiet and lovely places and hear the sweet murmur of streams. She'll watch the small beautiful girls that are dancing not according to any rules but spontaneously inspired by their heart joy. This joy will pass into her face. The life - giving feeling of joy will develop her mind and body. This union, born from joy will make her charming graceful woman. Nature will educate Lucy as long as she will live in communion with Nature.

Nature kept her word and educated Lucy the way she promised. But unfortunately Lucy died young. It left the poet alone in the world with the memory of Lucy, with the memories of fields where Lucy had played, with the memories of her unique education by Nature and her spirit which shall never witness in future. Nature would always miss her with a sorrow stricken heart.

Critical Appreciation of the Poem:

Wordsworth had immense belief in nature's inspiring force. He believes that nature is a universal chorus constantly communicating with man. He agreed with Rousseau that a child, allowed to satisfy his natural curiosity and encouraged to follow his own intuitions, would develop into a better being than a child grown up in the artificial atmosphere of educational institutions. And, nature is our great teacher; it exerts an edifying and moral influence on man.

In this poem, Nature acts as a loving mother and an effective teacher to Lucy. Nature has been personified and thus it is written with capital N . She determines to adopt Lucy and make her ‘A lady of my own’.

After having decided to adopt Lucy, this idea is elaborated; Nature reveals the methods to achieve Her objectives in the stanza. The process consists of taking up opposing principles to create the living complexity, marked by the antithesis between ‘law and impulse’, ‘rock and plain’, ‘earth and heaven’, ‘glade and bower’ and ‘kindle and restrain.’

Being law and impulse, Nature checks Lucy from any negative energy, i.e., evils and also inspires her to do positive, i.e., noble deeds. As a guide, she would imbibe the best from her surroundings and the sheer joy of spontaneity would help in developing her natural faculties.

The comparisons and contrasts used by the poet to his thoughts, while describing the Nature, has made the composition beautiful the fawn by frolicking in the lawns, clouds floating calmly in the sky, the graceful willow trees bending, the sparking of stars at midnight, gently murmuring rivulets. There is no contradiction in Nature while doing these comparisons. Every sight and sound has its own effect on the child of Nature.

The poet has emphasized the physical as well as the mental development through intimate association.

The fifth stanza is onomatopoeic in nature because words, in this stanza, have been used in such a manner that their sound suggests the sense. The final stanza, which ends on a sad note of Lucy's death, is not merely a lament over the death of a particular young female. It is a statement on the condition of all human life, in which all the powers of Nature combine in complex ways to create a human being, who is doomed to death by Nature's law.

The poet, we can say, breathes new life into the lyric form. The delicate elegance of the descriptions in this poem are noteworthy. The language is simple with no pretensions to grandeur. The poem has a beautiful blend of sound and sense. In all, the poem reflects Wordsworth's excellence over simple technical skill.

You may like these posts

Social plugin, popular posts.

The Queen’s Rival by Sarojini Naidu, Summary and Critical Appreciation

Poem Poet, Lover, Birdwatcher Summary and Critical Analysis

Summary and Critical Appreciation of Our Casuarina Tree by Toru Dutt

Nissim’s Poem Philosophy, Summary and Critical Analysis

.webp)

Summary and Critical Appreciation of Upagupta by Tagore

- English Dramas

- English History

- English Novels

- English Poetry

- Essays in Criticism

- Indian English Novels

- Indian English Poetry

- Literary Essays

- Shakespeare's Sonnets

- Short Stories

- A Country 1

- A Hot Noon in Malabar 1

- A Prayer for My Daughter 1

- After Apple-Picking 1

- After Reading A Prediction 1

- Among School Children 1

- An Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard 3

- An Introduction 1

- Background Casually 1

- Because I could Not Stop for Death 3

- Boat Ride along the Ganga 1

- Breaded Fish 1

- Break Break Break 1

- Case Study 1

- Channel Firing 1

- Chicago Zen 1

- Church Going 1

- Come into the Garden 1

- Dawn at Puri 1

- Death Be Not Proud 1

- Departmental 1

- Directive 1

- Dockery and Son 1

- Dover Beach 1

- Emily Dickinson 1

- English Dramas 21

- English History 2

- English Novels 13

- English Poetry 82

- Enterprise 2

- Essay on Wordsworth 1

- Essays in Criticism 2

- Fire and Ice 1

- Fire-Hymn 1

- For Love's Record 1

- From The Twenty-Fifth Anniversary of A Republic 1975 1

- Frost at Midnight 2

- G M Hopkins 1

- Ghanashyam 1

- Grandfather 1

- Hayavadana 2

- Heat and Dust 2

- Home Burial 1

- Indian English Literature 1

- Indian English Novels 2

- Indian English Poetry 62

- Indian Poetry 1

- John Donne 3

- Keats’ Sensuousness and Passion for Beauty 1

- Literary Essays 3

- Looking for A Cousin on A Swing 1

- Lord of the Flies 4

- Midnight's Children 1

- Midnight’s Children 1

- Mulk Raj Anand 1

- Musee Des Beaux Arts 1

- My Grandmother’s House 1

- Night of the Scorpion 1

- Nissim Ezekiel 4

- No Second Troy 1

- Ode on A Grecian Urn 4

- Ode to Autumn 1

- Oliver Twist 3

- On Not Being A Philosopher 1

- On Not Being A Philosopher Critical Analysis 1

- Our Casuarina Tree 1

- P B shelley as a revolutionary poet 1

- Percy Bysshe Shelley as a revolutionary poet 1

- Philip Larkin 4

- Philosophy 1

- Pied Beauty 1

- Poem of the Separation 1

- Poet Lover Birdwatcher 1

- Poetry of Departures 1

- Poets and Authors 46

- Porphyria’s Lover 4

- Revolutionary poet Percy Bysshe shelley 1

- Robert Browning 1

- Robert Frost 3

- Robert Lynd 2

- Robert Lynd's On Not Being a Philosopher 1

- Robert Lynd's On Not Being a Philosopher (Summary) 1

- Sailing to Byzantium 1

- Samuel Barclay Beckett 3

- Sarojini Naidu 4

- Section Two from (Relationship) 1

- Self-Portrait 1

- Shakespeare's Sonnets 3

- Short Stories 4

- T S Eliot 2

- The Abandoned British Cemetery at Balasore 1

- The Darkness 1

- The Diamond Necklace 1

- The Education of Nature 1

- The Family Reunion 3

- The Forsaken Merman 1

- The Freaks 1

- The Gift of India 1

- The Gift Outright 1

- The Invitation 1

- The Kabuliwala 1

- The Lady of Shalott 4

- The Lake Isle of Innisfree 1

- The Looking-Glass 1

- The Luncheon 1

- The Merchant of Venice 9

- The Moon Moments 1

- The Old Playhouse 1

- The Onset 1

- The Pleasures of Ignorance 1

- The Power and the Glory 2

- The Queen’s Rival 1

- The Railway Clerk 1

- The Road Not Taken 3

- The Striders 1

- The Sunshine Cat 1

- The Visitor 1

- The Waste Land 8

- The Whorehouse in A Calcutta Street 1

- The Wild Bougainvillea 1

- The World Is Too Much With Us 1

- The World of Nagaraj 1

- Thomas Gray 1

- Thou Art Indeed Just Lord 1

- Tintern Abbey 6

- Total Solar Eclipse 1

- Two Nights of Love and Virginal 1

- Victorian Age 2

- W B Yeats 5

- W H Auden 2

- Waiting for Godot 3

- Walking by the River 1

- William Wordsworth 1

Most Recent

Footer Copyright

Contact form.

Ecological Literacy in Education: Empowering Students to Understand, Appreciate, and Conserve Nature

In an era where environmental challenges are becoming increasingly pressing, fostering ecological literacy among students has never been more crucial. Ecological literacy goes beyond simply understanding the natural world.

It encompasses a deep appreciation for the interconnectedness of ecosystems, the importance of biodiversity, and the urgency of conservation efforts. Integrating ecological literacy into education equips students with the knowledge and mindset necessary to become responsible stewards of the planet.

This article explores the significance of ecological literacy in education and highlights ways to empower students to understand, appreciate, and conserve nature.

Understanding Ecological Literacy

Ecological literacy refers to a comprehensive understanding of ecological concepts, systems, and processes. It goes beyond memorizing facts and terms; it involves grasping the intricate relationships between organisms, their environments, and the impact of human activities on these systems.

An ecologically literate individual can recognize how the health of ecosystems directly affects human well-being, and vice versa. This knowledge forms the foundation for informed decision-making and sustainable practices.

The Benefits of Ecological Literacy

- Informed Decision-Making: Ecologically literate individuals are better equipped to make environmentally conscious decisions in their personal lives and careers. Whether it’s choosing sustainable products, supporting conservation initiatives, or advocating for responsible policies, their decisions are rooted in a profound understanding of ecological dynamics.

- Fostering Environmental Stewardship: Ecological literacy nurtures a sense of responsibility and connection to the natural world. Students who develop an appreciation for the intricate beauty and functionality of ecosystems are more likely to become passionate advocates for environmental protection.

- Addressing Global Challenges: Climate change, habitat loss, and pollution are global challenges that demand collective action. Ecologically literate citizens are crucial for devising innovative solutions, driving policy changes, and influencing societal behaviors to mitigate these issues.

- Interdisciplinary Learning: Ecological literacy naturally integrates various disciplines such as biology, geography, chemistry, and social sciences. This interdisciplinary approach encourages holistic thinking and a broader perspective on complex environmental issues.

Empowering Students: Strategies for Ecological Literacy

Empowering students with ecological literacy involves engaging them in meaningful learning experiences that foster a deep connection to the environment. By implementing a variety of strategies, educators can inspire students to not only understand but also appreciate and conserve nature. Let’s delve into some effective approaches:

- Hands-On Experiences: The power of direct interaction with nature cannot be overstated. Organize field trips to local ecosystems, botanical gardens, or wildlife reserves, where students can observe ecological interactions up close. These outings encourage curiosity and provide real-world context to classroom learning. Whether it’s examining plant adaptations, observing animal behaviors, or studying water quality, these experiences offer valuable insights into ecological systems.

- Curriculum Integration: Ecological literacy shouldn’t be confined to science classes alone. Infuse ecological concepts into various subjects to showcase the interconnectedness of ecosystems with history, literature, art, and even mathematics. For instance, literature classes can explore the depiction of nature in poems and novels, while history classes can examine the environmental impact of key events. This interdisciplinary approach widens students’ perspectives and highlights the relevance of ecological understanding in diverse fields.

- Guest Speakers and Experts: Inviting experts in the field of ecology and environmental conservation can add a dynamic dimension to students’ learning experiences. Guest speakers can share their experiences, research findings, and real-world insights, demonstrating the practical applications of ecological knowledge. Students can interact with professionals who have worked on conservation projects, conducted ecological research, or developed sustainable practices.

- Technology and Virtual Resources: In a digitally connected world, technology can bridge the gap between classroom learning and real-world ecological scenarios. Utilize virtual simulations, online ecosystem models, and interactive data visualizations to engage students in understanding complex ecological concepts. Online resources can provide interactive experiences, making abstract concepts more tangible and relatable.

- Community Engagement: Collaborate with local environmental organizations, conservation groups, or governmental agencies to involve students in community-driven conservation efforts. Participating in tree planting, beach cleanups, or habitat restoration projects gives students a tangible sense of contributing to the well-being of their community and the planet. This hands-on involvement reinforces the idea that individual actions can collectively make a significant impact.

By embracing these strategies, educators can foster a generation of environmentally conscious and ecologically literate individuals who are well-equipped to face the challenges of an ever-changing world.

To further enhance students’ educational journey, resources like essay writing services can provide support in creating impactful essays, reports, and projects related to ecological literacy.

These services offer students a platform to explore their thoughts, articulate their understanding, and communicate their passion for the environment effectively.

Ecological literacy is not just a subject to be studied; it is a mindset that shapes how individuals perceive and interact with the world around them. By embedding ecological concepts into education, we equip students with the knowledge, empathy, and skills needed to become effective advocates for nature.

As students develop a deeper understanding and appreciation for the intricate web of life, they are empowered to take action, driving positive change for a more sustainable and harmonious future.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from Earth Buddies

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 23 March 2018

The nature and nurture of education

- Pankaj Sah 1 ,

- Michael Fanselow 2 ,

- Gregory J. Quirk 3 ,

- John Hattie 4 ,

- Jason Mattingley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0929-9216 1 &

- Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa 5

npj Science of Learning volume 3 , Article number: 6 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

2 Citations

18 Altmetric

Metrics details

Learning is a life-long endeavour that continues from infancy to old age. We each navigate the learning process in different ways, yielding to our experiences and the circumstances in which we find ourselves. For many people, formal education takes place between the ages of 6–18, where we are educated based on core curricula that are delivered through a schooling system. Many countries have some form of compulsory education for children until they reach adulthood, but the route through the school system can vary greatly. In many first world countries, the choice is between public schools, generally funded by the state, and private schools which are funded through a combination of individual tuition fees, and religious or corporate institutions. School education is generally required by government mandate, and the cost of admission and tuition in public schools is borne by the state. In contrast, entry into a private school is often primarily dependent on socioeconomic status and some form of selection process—either formal testing or religious affiliation.

In many countries, studies have suggested that students attending private schools attain better educational outcomes, and long-term socioeconomic benefits. These data are then used by private schools to encourage attendance in this selective system. Private schools are generally expensive but may provide more individualized programs of study with better student–faculty ratios then those provided by public schools.

The choice parents make in selecting schools for their children, and the differences between public and private schools has been the subject of much debate, that is largely couched in social and economic terms. In a collection of manuscripts published in npj Science of Learning , two groups of researchers have approached this discussion from an interesting new direction—genetics. The Nature versus Nurture question has been greatly debated for many years, because it is not entirely clear which is the greatest influence on human development and behaviour. Although we are all born with a specific set of genes, with no control over our genetic allocation, we now know our life-style choices and different experiences though development and maturity also influence gene expression, and thus exert control over our behaviour via epigenetic modifications. Epigenetic mechanisms regulate the structure and activity of the genome in response to cellular and environmental cues, one such mechanism involves DNA methylation. Thus, biological processes are controlled by a combination of inherited genes and the life-long impact of epigenetic modifications that regulates their expression. Who we are is not simply a result of either nature or nurture but rather is shaped by a combination of these factors. Recent advances in genomic and epigenomic sequencing, have led to a growing interest in using this information to predict biological outcomes, and disease pathogenesis and help guide individuals in lifestyle choices and behaviour.

Two papers 1 , 2 published in npj Science of Learning have worked to address the question of 'Does an individual’s genetic makeup, and epigenetic modification, affect his or her educational attainment?'. Educational attainment is a measure of the highest level of education that an individual has completed at the end of full-time compulsory education. Educational attainment has been shown to strongly correlate with mental and physical health, as well as socioeconomic status, and is one of the strongest predictors of lifetime success, not only economically but also in terms of health and longevity.

In one study, 1 Smith–Woolley and colleagues looked at educational attainment in three groups of students in Britain that attended either: public schools, private schools or selective schools. The researchers found that as previously reported, students in private schools had higher levels of educational attainment than those in public schools. They then examined the genetic differences between students in these groups, and surprisingly, there were differences in genetic markers between them. Interestingly, when differences in genetics were accounted for, educational attainment differences between students attending the different schools disappeared.

In another study, 2 van Dongen and colleagues examine the DNA methylation status of genes in people with different levels of educational attainment. They found differential sites of DNA methylation at specific regions (loci) correlate with educational attainment and the methylation status of these sites are largely influenced by environmental factors such as smoking. These sites of differential methylation were found to be located in and near genes with neuronal, immune and developmental functions. Differential levels of DNA methylation in these regions could impact the expression of these genes during critical periods of childhood development. Together, the two studies point to the role of genetics and epigenetic changes in educational outcome. Two accompanying perspective pieces, one by Nick Martin 3 and the other by Sue Thompson, 4 provide a commentary on the implications of these studies from the genetic 3 and educational 4 viewpoint.

There is a growing interest in genomic and epigenomic sequencing of different populations, with the data generated being incorporated into many different databases. Large-scale projects like the ENCODE (Encyclopedia of DNA Elements) Consortium, which is an international collaboration of research groups funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), and the British 100,000 genomes project, led by Genomics England, are leading the way in trying to understand how these factors influence biological processes. The two studies published in npj Science of Learning raise the question of the use of genomic data to help predict educational outcomes. Just as the management of our health is increasingly being found to be affected by genetic and epigenetic determinants, it may be that individuals progress through the education system based upon these factors as well.

Smith-Woolley, E. et al. Differences in exam performance between pupils attending selective and non-selective schools mirror the genetic differences between them. npj Sci. Learn. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-018-0019-8 (2018).

van Dongen, J. et al. DNA methylation signatures of educational attainment. npj Sci. Learn. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-018-0020-2 (2018).

Martin, N. Getting to the genetic and environmental roots of educational inequality. npj Sci. Learn. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-018-0021-1 (2018).

Thomson, S. Achievement at school and socioeconomic background—an educational perspective. npj Sci. Learn. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-018-0022-0 (2018).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Queensland Brain Institute, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, 4072, Australia

Pankaj Sah & Jason Mattingley

Staglin Center for Brain and Behavioral Health, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Michael Fanselow

School of Medicine, University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, Puerto Rico

Gregory J. Quirk

Graduate School of Education, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia

John Hattie

Applied Educational Research Center, Latin American School of Social Sciences, Harvard Extension School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA

Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

P.S., M.F., G.J.Q., J.H., J.M. and T.T.E. contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Pankaj Sah .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Sah, P., Fanselow, M., Quirk, G.J. et al. The nature and nurture of education. npj Science Learn 3 , 6 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-018-0023-z

Download citation

Received : 07 February 2018

Accepted : 15 February 2018

Published : 23 March 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-018-0023-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

education, community-building and change

Jean-Jacques Rousseau on nature, wholeness and education

Jean-jacques rousseau – wikipedia commons – pd, jean-jacques rousseau on nature, wholeness and education. his novel émile was the most significant book on education after plato’s republic, and his other work had a profound impact on political theory and practice, romanticism and the development of the novel. we explore jean-jacques rousseau’s life and contribution..

contents : introduction · life · nature, wholeness and romanticism · social contract and the general will · on education · on the development of the person · conclusion · further reading and references · links · how to cite this article

Why should those concerned with education study Rousseau? He had an unusual childhood with no formal education. He was a poor teacher. Apparently unable to bring up his own children, he committed them to orphanages soon after birth. At times he found living among people difficult, preferring the solitary life. What can such a man offer educators? The answer is that his work offers great insight. Drawing from a broad spectrum of traditions including botany, music and philosophy, his thinking has influenced subsequent generations of educational thinkers – and permeates the practice of informal educators. His book Émile was the most significant book on education after Plato’s Republic , and his other work had a profound impact on political theory and practice, romanticism and the development of the novel (Wokler 1995: 1).

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 1778) was born in Geneva (June 28) but became famous as a ‘French’ political philosopher and educationalist. Rousseau was brought up first by his father (Issac) and an aunt (his mother died a few days after his birth), and later and by an uncle. He had happy memories of his childhood – although it had some odd features such as not being allowed to play with children his own age. His father taught him to read and helped him to appreciate the countryside. He increasingly turned to the latter for solace.

At the age of 13 he was apprenticed to an engraver. However, at 16 (in 1728) he left this trade to travel, but quickly become secretary and companion to Madame Louise de Warens. This relationship was unusual. Twelve years his senior she was in turns a mother figure, a friend and a lover. Under her patronage he developed a taste for music. He set himself up as a music teacher in Chambéry (1732) and began a period of intense self education. In 1740 he worked as a tutor to the two sons of M. de Mably in Lyon. It was not a very successful experience (nor were his other episodes of tutoring). In 1742 he moved to Paris. There he became a close friend of David Diderot, who was to commission him to write articles on music for the French Encyclopédie. Through the sponsorship of a number of society women he became the personal secretary to the French ambassador to Venice – a position from which he was quickly fired for not having the ability to put up with a boss whom he viewed as stupid and arrogant.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau returned to Paris in 1745 and earned a living as a music teacher and copyist. In the hotel where he was living (near the Sorbonne) he met Thérèse Lavasseur who worked as a seamstress. She was also, by a number of accounts, an odd figure. She was made fun of by many of those around here, and it was Rousseau’s defence of her that led to friendship. He believed she had a ‘pure and innocent heart’. They were soon living together (and they were to stay together, never officially married, until he died). She couldn’t read well, nor write, or add up – and Rousseau tried unsuccessfully over the years to teach her. According to his Confessions , Thérèse bore five children – all of whom were given to foundling homes (the first in 1746) (1996: 333). Voltaire later scurrilously claimed that Rousseau had dumped them on the doorstep of the orphanage. In fact the picture was rather more complex. Rousseau had argued the children would get a better upbringing in such an institution than he could offer. They would not have to put up with the deviousness of ‘high society’. Furthermore, he claimed he lacked the money to bring them up properly. There was also the question of his and Thérèse’s capacity to cope with child-rearing. Last, there is also some question as to whether all or any of the children were his (for example, Thérèse had an affair with James Boswell whilst he stayed with Rousseau). What we do know is that in later life Rousseau sought to justify his actions concerning the children (see, for example 1996: 345-346); declaring his sorrow about the way he had acted.

Diderot encouraged Rousseau to write and in 1750 he won first prize in an essay competition organized by the Académie de Dijon – Discours sur les sciences et les arts . ‘Why should we build our own happiness on the opinions of others, when we can find it in our own hearts?’ (1750: 29). In this essay we see a familiar theme: that humans are by nature good – and it is society’s institutions that corrupt them (Smith and Smith 1994: 184). The essay earned him considerable fame and he reacted against it. He seems to have fallen out with a number of his friends and the (high-society) people with whom he was expected to mix. This was a period of reappraisal. On a visit to Geneva Jean-Jacques Rousseau reconverted to Calvinism (and gained Genevan citizenship). There was also a fairly public infatuation with Mme d’Houderot that with his other erratic behaviour, led some of his friends to consider him insane.

Rousseau’s mental health was a matter of some concern for the rest of his life. There were significant periods when he found it difficult to be in the company of others, when he believed himself to be the focus of hostility and duplicity (a feeling probably compounded by the fact that there was some truth in this). He frequently acted ‘oddly’ with sudden changes of mood. These ‘oscillations’ led to situations where he falsely accused others and behaved with scant respect for their humanity. There was something about what, and the way, he wrote and how he acted with others that contributed to his being on the receiving end of strong, and sometimes malicious, attacks by people like Voltaire. The ‘oscillations’ could also open up ‘another universe’ in which he could see the world in a different, and illuminating, way (see Grimsley 1969).

At around the time of the publication of his famous very influential discourses on inequality and political economy in Encyclopedie (1755), Rousseau also began to fall out with Diderot and the Encyclopedists. The Duke and Duchess of Luxembourg offered him (and Thérèse) a house on their estate at Montmorency (to the north of Paris).

During the next four years in the relative seclusion of Montmorency, Rousseau produced three major works: The New Heloise (1761), probably the most widely read novel of his day); The Social Contract (April 1762), one of the most influential books on political theory; and Émile (May 1762), a classic statement of education. The ‘heretical’ discussion of religion in Émile caused Rousseau problems with the Church in France. The book was burned in a number of places. Within a month Rousseau had to leave France for Switzerland – but was unable to go to Geneva after his citizenship was revoked as a result of the furore over the book. He ended up in Berne. In 1766 Jean-Jacques Rousseau went to England (first to Chiswick then Wootton Hall near Ashbourne in Derbyshire, and later to Hume’s house in Buckingham Street , London) at the invitation of David Hume. True to form he fell out with Hume, accusing him of disloyalty (not fairly!) and displaying all the symptoms of paranoia. In 1767 he returned to France under a false name (Renou), although he had to wait until to 1770 to return officially. A condition of his return was his agreement not to publish his work. He continued writing, completing his Confessions and beginning private readings of it in 1770. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was banned from doing this by the police in 1771 following complaints by former friends such as Diderot and Madame d’Epinay – who featured in the work. The book was eventually published after his death in 1782.

Rousseau returned to copying music to make a living, working in the morning and walking and ‘botanizing’ in the afternoon. He continued to have mental health problems. His next major work was Rousseau juge de Jean-Jacques, Dialogues , completed in 1776. In the next two years, before his death in 1778, Rousseau wrote the ten, classic, meditations of Reveries of the Solitary Walker . The book opens: ‘So now I am alone in the world, with no brother, neighbour or friend, nor any company left me but my own. The most sociable and loving of men has with unanimous accord been cast out by all the rest’ (1979: 27). He appears to have come upon a period of some calm and serenity (France 1979: 9). At this time ‘he found respite only in solitude, the study of botany, and a romantically lyrical communion with nature’ (Wokler 1995: 15).

In 1778 he was in Ermenonville, just north of Paris, staying with the Marquis de Giradin. On July 2, following his usual early morning walk Jean-Jacques Rousseau died of apoplexy (a haemorrhage – some of his former friends claimed he committed suicide). He was buried on the estate (on a small picturesque island – Ile des Peupliers ). Later, in 1794, his remains were moved to the Panthéon in Paris (formerly the Church of Sainte Geneviève. The Pantheon was used to house the bodies of key figures of the French Revolution.) His remains were placed close by those of Voltaire, who had died in the same year as him.

Nature, wholeness and romanticism

Rousseau argued that we are inherently good, but we become corrupted by the evils of society. We are born good – and that is our natural state. In later life he wished to live a simple life, to be close to nature and to enjoy what it gives us – a concern said to have been fostered by his father. Through attending to nature we are more likely to live a life of virtue. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was interested in people being natural.

We are born capable of sensation and from birth are affected in diverse ways by the objects around us. As soon as we become conscious of our sensations we are inclined to seek or to avoid the objects which produce them: at first, because they are agreeable or disagreeable to us, later because we discover that they suit or do not suit us, and ultimately because of the judgements we pass on them by reference to the idea of happiness of perfection we get from reason. These inclinations extend and strengthen with the growth of sensibility and intelligence, but under the pressure of habit they are changed to some extent with our opinions. The inclinations before this change are what I call our nature. In my view everything ought to be in conformity with these original inclinations. ( Émile , Book 1 – translation by Boyd 1956: 13; see also, 1911 edition p. 7).

As Ronald Grimsley has written, ‘From the outset Rousseau had drawn inspiration from his own heart and found philosophical truth in the depth of his own being’ (1973: 135). His later writings, especially Reveries of the Solitary Walker , show both his isolation and alienation, and some paths into happiness. ‘Everything is in constant flux on this earth, he writes (1979: 88):

But if there is a state where the soul can find a resting-place secure enough to establish itself and concentrate its entire being there, with no need to remember the past or reach into the future, where time is nothing to it, where the present runs on indefinitely but this duration goes unnoticed, with no sign of the passing of time, and no other feeling of deprivation or enjoyment, pleasure or pain, desire or fear than the simple feeling of existence, a feeling that fills our soul entirely, as long as this state lasts, we can call ourselves happy, not with a poor, incomplete and relative happiness such as we find in the pleasures of life, but with a sufficient, complete and perfect happiness which leaves no emptiness to be filled in the soul. Such is the state which I often experienced on the Island Of Saint-Pierre in my solitary reveries, whether I lay in a boat and drifted where the water carried me, or sat by the shores of the stormy lake, or elsewhere, on the banks of a lovely river or a stream murmuring over the stones. (Rousseau 1979: 88 – 89)

Rousseau’s is sometimes described as a romantic vision. ‘Romanticism’ is not an easy term to define – it is best approached as an overlapping set of ideas and values.

The ‘Romantic’ is said to favour the concrete over the abstract, variety over uniformity, the infinite over the finite,; nature over culture, convention and artifice; the organic over the mechanical; freedom over constraint, rules and limitations. In human terms it prefers the unique individual to the average person, the free creative genius to the prudent person of good sense, the particular community or nation to humanity at large. Mentally, the Romantics prefer feeling to thought, more specifically emotion to calculation; imagination to literal common sense, intuition to intellect. (Quinton 1996: 778)

In many respects Rousseau’s vision could be labelled as ‘green’. But with this comes a classic tension between the individual and society, solitude and association – and this is central to his work.

Social contract and the general will

Chapter 1 of his classic work on political theory The Social Contract (published in 1762) begins famously, ‘Man was born free, and he is everywhere in chains’. It is an expression of his belief that we corrupted by society. The social contract he explores in the book involves people recognizing a collective ‘general will’. This general will is supposed to represent the common good or public interest – and it is something that each individual has a hand in making. All citizens should participate – and should be committed to the general good – even if it means acting against their private or personal interests. For example, we might support a political party that proposes to tax us heavily (as we have a large income) because we can see the benefit that this taxation can bring to all. To this extend, Rousseau believed that the good individual, or citizen, should not put their private ambitions first.

This way of living, he argued, can promote liberty and equality – and it arises out of, and fosters, a spirit of fraternity. The cry of ‘liberty, equality and fraternity’ is familiar to us today through the French Revolution (1789 – 1799) – and the impact of the thinking and experiences of that time have had on political movements in many different parts of the world since. Just how the ‘general will’ comes about is unclear – and this has profound implications. If we are to put the general will over the individual or ‘particular’ will then there needs to be safeguards against the exploitation of individuals and minorities. Rousseau’s belief in liberty, equality and fraternity, and his emphasis on education (see below) may go some way in counteracting the dangers of the general will, but others have hijacked the notion so that the majority rules the minority – or indeed a minority a majority – it just depends who has the power to define or interpret the general will.

On education

The focus of Émile is upon the individual tuition of a boy/young man in line with the principles of ‘natural education’. This focus tends to be what is taken up by later commentators, yet Rousseau’s concern with the individual is balanced in some of his other writing with the need for public or national education. In A Discourse on Political Economy and Considerations for the Government of Poland we get a picture of public education undertaken in the interests of the community as a whole.

From the first moment of life, men ought to begin learning to deserve to live; and, as at the instant of birth we partake of the rights of citizenship, that instant ought to be the beginning of the exercise of our duty. If there are laws for the age of maturity, there ought to be laws for infancy, teaching obedience to others: and as the reason of each man is not left to be the sole arbiter of his duties, government ought the less indiscriminately to abandon to the intelligence and prejudices of fathers the education of their children, as that education is of still greater importance to the State than to the fathers: for, according to the course of nature, the death of the father often deprives him of the final fruits of education; but his country sooner or later perceives its effects. Families dissolve but the State remains. (Rousseau 1755: 148-9)

‘Make the citizen good by training’, Jean-Jacques Rousseau writes, ‘and everything else will follow’.

In Émile Rousseau drew on thinkers that had preceded him – for example, John Locke on teaching – but he was able to pull together strands into a coherent and comprehensive system – and by using the medium of the novel he was able to dramatize his ideas and reach a very wide audience. He made, it can be argued, the first comprehensive attempt to describe a system of education according to what he saw as ‘nature’ (Stewart and McCann 1967:28). It certainly stresses wholeness and harmony, and a concern for the person of the learner. Central to this was the idea that it was possible to preserve the ‘original perfect nature’ of the child, ‘by means of the careful control of his education and environment, based on an analysis of the different physical and psychological stages through which he passed from birth to maturity’ (ibid.). This was a fundamental point. Rousseau argued that the momentum for learning was provided by the growth of the person (nature) – and that what the educator needed to do was to facilitate opportunities for learning.

The focus on the environment, on the need to develop opportunities for new experiences and reflection, and on the dynamic provided by each person’s development remain very powerful ideas.

We’ll quickly list some of the key elements that we still see in his writing:

- a view of children as very different to adults – as innocent, vulnerable, slow to mature – and entitled to freedom and happiness (Darling 1994: 6). In other words, children are naturally good.

- the idea that people develop through various stages – and that different forms of education may be appropriate to each.

- a guiding principle that what is to be learned should be determined by an understanding of the person’s nature at each stage of their development.

- an appreciation that individuals vary within stages – and that education must as a result be individualized. ‘Every mind has its own form’

- each and every child has some fundamental impulse to activity. Restlessness in time being replaced by curiosity; mental activity being a direct development of bodily activity.

- the power of the environment in determining the success of educational encounters. It was crucial – as Dewey also recognized – that educators attend to the environment. The more they were able to control it – the more effective would be the education.

- the controlling function of the educator – The child, Rousseau argues, should remain in complete ignorance of those ideas which are beyond his/her grasp. (This he sees as a fundamental principle).

- the importance of developing ideas for ourselves, to make sense of the world in our own way. People must be encouraged to reason their way through to their own conclusions – they should not rely on the authority of the teacher. Thus, instead of being taught other people’s ideas, Émile is encouraged to draw his own conclusions from his own experience. What we know today as ‘discovery learning’ One example, Rousseau gives is of Émile breaking a window – only to find he gets cold because it is left unrepaired.

- a concern for both public and individual education.

We could go on – all we want to do is to establish what a far reaching gift Rousseau gave. We may well disagree with various aspects of his scheme – but there can be no denying his impact then – and now. It may well be, as Darling (1994: 17) has argued, that the history of child-centred educational theory is a series of footnotes to Rousseau.

On the development of the person

Rousseau believed it was possible to preserve the original nature of the child by careful control of his education and environment based on an analysis of the different physical and psychological stages through which he passed from birth to maturity (Stewart and McCann 1967). As we have seen he thought that momentum for learning was provided by growth of the person (nature).

In Émile, Rousseau divides development into five stages (a book is devoted to each). Education in the first two stages seeks to the senses: only when Émile is about 12 does the tutor begin to work to develop his mind. Later, in Book 5, Rousseau examines the education of Sophie (whom Émile is to marry). Here he sets out what he sees as the essential differences that flow from sex. ‘The man should be strong and active; the woman should be weak and passive’ (Everyman edn: 322). From this difference comes a contrasting education. They are not to be brought up in ignorance and kept to housework: Nature means them to think, to will, to love to cultivate their minds as well as their persons; she puts these weapons in their hands to make up for their lack of strength and to enable them to direct the strength of men. They should learn many things, but only such things as suitable’ (Everyman edn.: 327). The stages below are those associated with males.

Stage 1: Infancy (birth to two years). The first stage is infancy, from birth to about two years. (Book I). Infancy finishes with the weaning of the child. He sets a number of maxims, the spirit of which is to give children ‘more real liberty and less power, to let them do more for themselves and demand less of others; so that by teaching them from the first to confine their wishes within the limits of their powers they will scarcely feel the want of whatever is not in their power’ (Everyman edn: 35).

The only habit the child should be allowed to acquire is to contract none… Prepare in good time form the reign of freedom and the exercise of his powers, by allowing his body its natural habits and accustoming him always to be his own master and follow the dictates of his will as soon as he has a will of his own. (Émile, Book 1 – translation by Boyd 1956: 23; Everyman edn: 30)

Stage 2: ‘The age of Nature’ (two to 12). The second stage, from two to ten or twelve, is ‘the age of Nature’. During this time, the child receives only a ‘negative education’: no moral instruction, no verbal learning. He sets out the most important rule of education: ‘Do not save time, but lose it… The mind should be left undisturbed till its faculties have developed’ (Everyman edn.: 57; Boyd: 41). The purpose of education at this stage is to develop physical qualities and particularly senses, but not minds. In the latter part of Book II, Rousseau describes the cultivation of each of Émile’s five senses in turn.

Stage 3: Pre-adolescence (12-15). Émile in Stage 3 is like the ‘noble savage’ Rousseau describes in The Social Contract. ‘About twelve or thirteen the child’s strength increases far more rapidly than his needs’ (Everyman edn.: 128). The urge for activity now takes a mental form; there is greater capacity for sustained attention (Boyd 1956: 69). The educator has to respond accordingly.

Our real teachers are experience and emotion, and man will never learn what befits a man except under its own conditions. A child knows he must become a man; all the ideas he may have as to man’s estate are so many opportunities for his instruction, but he should remain in complete ignorance of those ideas which are beyond his grasp. My whole book is one continued argument in support of this fundamental principle of education. (Everyman edn: 141; Boyd: 81)

The only book Émile is allowed is Robinson Crusoe – an expression of the solitary, self-sufficient man that Rousseau seeks to form (Boyd 1956: 69).

Stage 4: Puberty (15-20). Rousseau believes that by the time Émile is fifteen, his reason will be well developed, and he will then be able to deal with he sees as the dangerous emotions of adolescence, and with moral issues and religion. The second paragraph of the book contains the famous lines: ‘We are born, so to speak, twice over; born into existence, and born into life; born a human being, and born a man’ (Everyman edn: 172). As before, he is still wanting to hold back societal pressures and influences so that the ‘natural inclinations’ of the person may emerge without undue corruption. There is to be a gradual entry into community life (Boyd 1956: 95). Most of Book IV deals with Émile’s moral development. (It also contains the the statement of Rousseau’s’ his own religious principles, written as ‘The creed of a Savoyard priest’, which caused him so much trouble with the religious authorities of the day).

Stage 5: Adulthood (20-25). In Book V, the adult Émile is introduced to his ideal partner, Sophie. He learns about love, and is ready to return to society, proof, Rousseau hopes, after such a lengthy preparation, against its corrupting influences. The final task of the tutor is to ‘instruct the the young couple in their marital rights and duties’ (Boyd 1956: 130).

Sophie . This last book includes a substantial section concerning the education of woman. Rousseau subscribes to a view that sex differences go deep (and are complementary) – and that education must take account of this. ‘The man should be strong and active; the woman should be weak and passive; he one must have both the power and the will; it is enough that the other should offer little resistance’ (Everyman edn: 322). Sophie’s training for womanhood upto the age of ten involves physical training for grace; the dressing of dolls leading to drawing, writing, counting and reading; and the prevention of idleness and indocility. After the age of ten there is a concern with adornment and the arts of pleasing; religion; and the training of reason. ‘She has been trained careful rather than strictly, and her taste has been followed rather than thwarted’ (Everyman edn: 356). Rousseau then goes on to sum her qualities as a result of this schooling (356-362).

Rousseau’s gift to later generations is extraordinarily rich – and problematic. Émile was the most influential work on education after Plato’s Republic, The Confessions were the most important work of autobiography since that of St Augustine (Wokler 1995: 1); The Reveries played a significant role in the development of romantic naturalism; and The Social Contract has provided radicals and revolutionaries with key themes since it was published. Yet Rousseau can be presented at the same time as deeply individualist, and as controlling and pandering to popularist totalitarianism. In psychology he looked to stage theory and essentialist notions concerning the sexes (both of which continue to plague us) yet did bring out the significance of difference and of the impact of the environment. In life he was difficult he was difficult to be around, and had problems relating to others, yet he gave glimpses of a rare connectedness.

Further reading and references

Books by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Here we have listed the main texts:

Rousseau, J-J. (1750) A Discourse: Has the restoration of the arts and sciences had a purifying effect upon morals? Available in a single volume with The Social Contract , London: Dent Everyman. The essay that first established Rousseau.

Rousseau, J-J (1755) A Discourse on Inequality . Translated with an introduction by M. Cranston (1984 edn.), London: Penguin. Also available as an Everyman Book in a single volume with The Social Contract . Said to be one of the most revolutionary documents to have come out of eighteenth-century Europe. Seeks to show how the growth of civilization corrupts man’s natural happiness and freedom by creating artificial inequalities of wealth, power and social privilege. Rousseau contends that primitive man is equal to his fellows because he can be independent of them, but as societies become more sophisticated, the strongest and most intelligent members of the community gain an unnatural advantage over their weaker brethren, and the constitutions set up to rectify these imbalances through peace and justice in fact do nothing but perpetuate them.

Rousseau, J-J (1755) A Discourse on Political Economy . Available as part of The Social Contract and Discourses , London: Everyman/Dent.

Rousseau, J-J. (1761) La Nouvelle Heloise (The New Heloise: Julie, or the New Eloise : Letters of Two Lovers, Inhabitants of a Small Town at the Foot of the Alps) , Pennsylvania University Press. Story based on the relationship between Abelard and Heloise.

Rousseau, J-J. (1762) Émile , London: Dent (1911 edn.) Also available in edition translated and annotated by Allan Bloom (1991 edn.), London: Penguin. Rousseau’s exploration of education took the form of a novel concerning the tutoring of a young boy.

Rousseau, J-J (1762) The Social Contract , London: Penguin. (1953 edn.) Translated and introduced by Maurice Cranston. Also first published in 1762. (also published by Dent Everyman along with the Discourses).

Rousseau, J-J. (1782) Rousseau juge de Jean-Jacques, Dialogues (Rousseau, judge of Jean-Jacques, dialogues / edited by Roger D. Masters and Christopher Kelly ; tran slated by Judith R. Bush, Christopher Kelly, and Roger D. Masters) (1990 edn) , Hanover : Published for Dartmouth College by University Press of New England. Conversation between a seeker of truth about Jean-Jacques (Rousseau) and the ‘Frenchman’ – someone who had been a victim of the various ‘slanders’ made about J-J.

Rousseau, J-J (1782) The Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1953 edn.), London: Penguin. Extraordinary reading. ‘By writing his Confessions Rousseau not only wanted to know himself and alleviate his guilt, he sought also to recapture the happiness of the past, to saviour again those brief but precious occasions when he felt that he had been truly himself and had lived as nature had wanted’ (Grimsley 1973: 137)

Rousseau, J-J (1782) Reveries of the Solitary Walker . Translated with an introduction by P. France, London: Penguin. Unfinished series of reflections combining argument with anecdote and description. ‘As he wanders around Paris, gazing at plants and day-dreaming, Rousseau looks back over his life in order to justify his actions and to elaborate on his view of a well-structured society fit for the noble and solitary natural man’ This edition includes an introduction, notes and a brief chronology.

Many of these are available as e-texts (see below).

Books on Jean-Jacques Rousseau. There is a large number of books to choose from (especially you are fluent in French!) Listed here you will find those books we have found most useful in putting together this page:

Boyd, W. (1956) Émile for Today. The Émile of Jean Jaques Rousseau selected, translated and interpreted by William Boyd , London: Heinemann. Boyd does a good job in cutting down the book to its central elements for educators – and provides a very helpful epilogue on natural education and national education.

Cranston, M. (1983) Jean-Jacques , (1991) The Noble Savage , (1997) The Solitary Self. Jean-Jacques Rousseau in exile and adversity, Chicago: University of Chicago Press (also Allan Lane). The standard English language treatment of Rousseau in three volumes. Wonderful stuff.

Grimsley, R. (1969) Jean-Jacques Rousseau: A study in self-awareness , 2e, Cardiff: University of Wales Press. Provides some good insights into Rousseau’s character and psychology.

Grimsley, R. (1973) The Philosophy of Rousseau , Oxford: Oxford University Press. Useful summary and overview of Rousseau’s thinking. Chapters on society; nature; the psychological and moral development of the individual; religion; political theory; aesthetic ideas; and the problem of personal existence.

Mason, J. H. (1979) The Indispensable Rousseau , London: .Good overview of Rousseau plus a good selection of extracts from his work.

Masters, R. D. (1968) The Political Philosophy of Rousseau , Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. Detailed study of Rousseau’s political and educational thinking as they form a systematic doctrine.

Wokler, R. (1996) Rousseau, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Published in the ‘Past Masters’ series, this book provides an good overview of Rousseau’s work and contribution.

See, also, P. D. Jimack’s helpful introduction to The Social Contract and Discourses , London: Everyman.

For a brief introduction to his life see:

Smith, L. . and Smith, J. K. (1994) Lives in Education. A narrative of people and ideas 2e, New York: St Martins Press.

Hampson, N. (1990) The Enlightenment , London: Penguin. Good overview of key themes and contexts – and how these informed romanticism and later revolutionary crises.

Other references

Barry, B. (1967) “The Public Interest”, in Quinton, A. (ed.) Political Philosophy , Oxford: Oxford University Press

Bloom, A. (1991) ‘Introduction’ to Rousseau, J-J. (1762) Émile , London: Penguin.

Darling, J. (1994) Child-Centred Education and its Critics , London: Paul Chapman.

Dent, N.J.H. (1988) Rousseau: An Introduction to his Psychological, Social and Political Theory , Oxford: Basil Blackwell

Melzer, A.M. (1990) The Natural Goodness of Man: On the Sytem of Rousseau’s Thought , Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Miller, J. (1984) Rousseau: Dreamer of Democracy , London: Yale University Press

Quinton, A. (1996) ‘Philosophical romanticism’ in T. Honderich (ed.) The Oxford Companion to Philosophy , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Soëtard, , M. (1995) ‘Jean-Jacques Rousseau’ in Z. Morsy (ed.) Thinkers on Education Volume 4 , Paris: UNESCO.

Stewart, W. A. C. and McCann, W. P. (1967) The Educational Innovators. Volume 1 1750–1880 , London: Macmillan.

Why not visit:

Rousseau Association – has useful articles plus a range of links. Includes page devote to Rousseau and education.

The Jean-Jacques Rousseau Museum

Project Gutenberg – download Jean-Jacques Rouseau’s Confessions.. and Emile

EpistemeLinks – full listing of full electronic texts

Acknowledgement : The picture of Jean-Jacques Rousseau is, we believe, in the public domain @ wikipedia commons http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rousseau.jpg

How to cite this article : Michele Erina Doyle and Mark K. Smith (2007-2013) ‘Jean-Jacques Rousseau on education’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education, http://www.infed.org/thinkers/et-rous.htm . Last update: January 07, 2013

© Michele Erina Doyle and Mark K. Smith 1997, 2002, 2007, 2013

Last Updated on April 24, 2024 by infed.org

Advertisement

Effects of Nature (Greenspace) on Cognitive Functioning in School Children and Adolescents: a Systematic Review

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 19 March 2022

- Volume 34 , pages 1217–1254, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Dianne A. Vella-Brodrick 1 &

- Krystyna Gilowska 1

20k Accesses

31 Citations

59 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

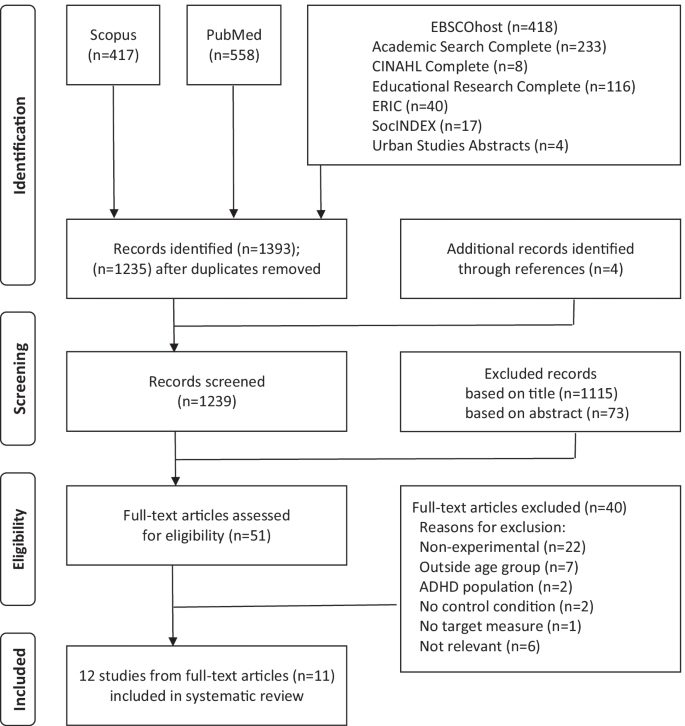

There is growing interest in understanding the extent to which natural environments can influence learning particularly in school contexts. Nature has the potential to relieve cognitive overload, reduce stress and increase wellbeing—all factors that are conducive to learning. This paper provides a PRISMA-guided systematic review of the literature examining the effects of nature interventions on the cognitive functioning of young people aged 5 to 18 years. Examples of nature interventions include outdoor learning, green playgrounds, walks in nature, plants in classrooms and nature views from classroom windows. These can vary in duration and level of interaction (passive or active). Experimental and quasi-experimental studies with comparison groups that employed standardized cognitive measures were selected, yielding 12 studies from 11 papers. Included studies were rated as being of high (n = 10) or moderate quality (n = 2) and most involved short-term nature interventions. Results provide substantial support for cognitive benefits of nature interventions regarding selective attention, sustained attention and working memory. Underlying mechanisms for the benefits were also explored, including enhanced wellbeing, cognitive restoration and stress reduction—all likely to be contributors to the nature-cognition relationship. The cognitive effects of nature interventions were also examined according to age and school level with some differences evident. Findings from this systematic review show promise that providing young people with opportunities to connect with nature, particularly in educational settings, can be conducive to enhanced cognitive functioning. Schools are well placed to provide much needed ‘green’ educational settings and experiences to assist with relieving cognitive overload and stress and to optimize wellbeing and learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Short-Term Exposure to Nature and Benefits for Students’ Cognitive Performance: a Review

How Education Can Be Leveraged to Foster Adolescents’ Nature Connection

Do Experiences with Nature Promote Learning? Converging Evidence of a Cause-And-Effect Relationship

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The pressure of modern-day westernized living involving technology, high-rise buildings, traffic congestion and pollution is taking a toll on society. These lifestyle changes have led to reduced opportunities for interacting with nature (Hartig et al., 2014 ) and a fast-paced lifestyle that can be psychologically draining. Subsequently health and well-being are compromised as evidenced by escalating rates of mental illness (Blake et al., 2018 ; Michaelson et al., 2020 ; Vancampfort et al., 2018 ). In an attempt to reduce fatigue and improve well-being, research attention has turned to the potential healing effects of nature (Capaldi et al, 2015 ; Diaz et al., 2015; Hartig et al., 2014 ).

Nature or natural environments are broadly defined as including living plants and animals, geological processes and weather. Nature exposure typically involves connecting with ‘green’ and ‘blue’ spaces including park land, forests, plants, the ocean and other natural waterways such as rivers and lakes. These can vary substantially in exposure time (from minutes to weeks and even years), as well as the extent to which nature is the core of the activity rather than simply in the background (Norwood et al., 2019 ). For example, nature interventions can include going for a walk amidst nature for 30 min, right through to creating a school garden which can last months or years. Multiple theories have been presented to explain the relationship between nature and different aspects of health. The Biophilia hypothesis (Urlich, 1983) posits that individuals are innately driven to affiliate with nature for survival and psychological restoration. When a connection with nature occurs, there is an opportunity for cognitive capacities to be relieved and well-being to be strengthened. The Attention Restoration Theory (ART; Kaplan, 1995 ) asserts that elements of the natural environment elicit a soft fascination from individuals that can release the need for relentless goal-directed attentional processes often associated with immersion in built environments and subsequently provides cognitive restoration. The Stress Reduction Theory (Ulrich, 1983 ; Ulrich et al., 1991 ) focuses on physiological responses to demonstrate that a reduction in stress induced by the natural environment can, in turn, enhance cognition. These theoretical perspectives offer a common theme of restoration through enhancing well-being by reducing mental fatigue or stress and are consistent with Wilson’s concept of ‘biophilia’ ( 1984 ). This suggests that exposure to nature can be helpful in learning environments where cognitive functioning is fundamental. It is the broad aim of this paper to undertake a systematic review of high-quality studies examining the effects of nature (greenspace) on the cognitive functioning of school children and adolescents. This will include a broad range of passive and active nature interventions, of varying duration, that are common in school settings. This will provide insights into whether specific theoretical perspectives are most relevant for particular types of interventions (e.g., short term or active).

There has been a keen interest in exploring the extent to which children and young people connect with nature, value nature and benefit from nature (e.g., Barrable & Booth, 2020 ; Roberts et al. ( 2020 ). This in part stems from concern about the rising rate of children growing up in urban environments and missing out on time spent outdoors in the natural environment (Weeland et al., 2019 ). Children have been identified as a population group with specific risks and needs relating to attention, self-regulation as well as physical and cognitive development (Roberts et al., 2020 ). The role of nature in assisting young people with these issues has preliminary empirical support, albeit with more diverse samples (Hartig et al, 2014 ) such as with older adults for memory enhancement (Astell-Burt & Feng, 2020 ). This has prompted interest in understanding how nature exposure can influence children’s cognitive development and learning particularly in school environments. For example, consistent with ART, it is plausible that exposure to nature can help children to replenish depleted cognitive resources resulting from information overload. An attraction to nature can trigger ‘soft’ (effortless) fascination, relieve fatigue and aid psychological replenishing. In support of this, van den Berg et al. ( 2016 ) found that university students and staff who viewed 40 images of natural and built scenes and rated these on complexity and restorative quality (fascination, beauty, relaxation and positive affect) recorded longer viewing times for the nature scenes—consistent with greater fascination with nature—and rated them as more restorative than built scenes.

Most of the empirical studies on nature are correlational designs. For example, Flouri (2019) examined the relationship between neighborhood greenspace and spatial working memory for 4,758 children aged 11 years living in urban areas of England. They found that less neighborhood greenspace (measured by satellite imagery) was related to poorer spatial working memory for these children. A study by Li et al., ( 2019 ) examined the relationship between tree cover density proximal to schools and academic performance for 624 high school students. They found that tree cover density in school surroundings was positively associated with academic performance (measured using Illinois Report Cards, American College Test scores and graduation rates). A study including 101 public high schools in Michigan examined whether nature exposure—nature views from school buildings, vegetation levels on campus and the potential for students to access this vegetation—was positively related to academic performance (e.g., Educational Assessment Program test and graduation rates) and inversely related to antisocial behaviors (Matsuoka, 2010 ). They found that landscapes of mowed grass and parking lots were associated with poorer student performance, whereas landscapes composed primarily of trees and shrubs were correlated with favorable academic performance. With few exceptions (e.g., Markevych et al., 2019 ), the majority of studies have found a positive relationship between nature exposure and cognitive functioning for children. In addition, learning in greenspace or viewing nature from a classroom has also been associated with reduced heart rate and cortisol levels (Dettweiler et al., 2017 ; Li & Sullivan, 2016 ). These favorable findings also extend to longitudinal studies whereby greater exposure to residential surrounding greenspace over one’s life, particularly in childhood, was associated with enhanced cognitive functioning and brain density (e.g., Dadvand et al., 2015 ).

A limitation of correlational studies is that causal relationships cannot be established, nor do they enable a clear understanding of the factors that influence the beneficial effects of nature on cognitive functioning. Kuo et al. ( 2019 ) examined some of these influential factors for enhancing cognitive functioning in learning environments and identified improved self-discipline, heightened motivation, enjoyment and engagement, as well as increased physical activity and fitness. They also noted some indirect effects of nature on learners such as the calm, quiet and safe contexts often associated with nature, which then facilitate warmer and cooperative social interactions and self-directed creative play. They also proposed the notion of a synergistic effect of the numerous processes underlying the nature-learning connection. For example, nature can simultaneously increase concentration, engagement and self-discipline to enhance learning. Although Kuo et al., ( 2019 ) provide (limited) empirical support for each of these processes, they note concerns relating to the poor-quality studies and over-generalization of results in this field.

The interest of this systematic review lies in the population of school children and since this group spans a long time period, it is important to examine how nature affects children at all stages of their development. Neighborhood greenness can play an important role in cognitive development starting from the very early stages of life (Dadvand et al., 2018 ; Liao et al., 2019 ) and continuing through to later stages of childhood (Flouri, et al., 2019 ; Lee, et al., 2019 ). Dadvand et al. ( 2018 ) reported long-term exposure to greenness early in child development to be associated with beneficial structural changes in the brain. Liao et al. ( 2019 ) observed that exposure to neighborhood greenspace is associated with better early childhood neurodevelopment for those up to 2 years of age including prenatals. Mason et.al. (2021) examined the impact of short-term (from 10 to 90 min) passive nature exposure on cognitive functioning in primary, secondary and tertiary students. They found that 12 out of 14 studies reported restorative effects of greenspace for attention and working memory for all education sectors. The authors suggest that different mechanisms may be involved in long-term nature exposures, and hence, this distinction warrants further investigation.

Some researchers have examined age differences in the relationship between greenspace and cognitive functioning. For example, Lee, et al., (2019) included 6–18 year old children in their study and found that both the younger and older groups showed inverse relationship with greenness and attention problems, indicating that nature may benefit children throughout their development. In a longitudinal study, Reuben et al. ( 2019 ) observed associations between greenspace exposure and cognitive performance across all ages. Children were assessed on fluid and crystalized intellectual performance at ages 5, 12 and 18. After adjusting for socioeconomic status, greenspace exposure predicted longitudinal benefits for fluid cognitive ability among 5 year-old children. These findings add to the body of research on the importance of nature in early brain development.