Gender equality and education

Gender equality is a global priority at UNESCO. Globally, 122 million girls and 128 million boys are out of school. Women still account for almost two-thirds of all adults unable to read.

UNESCO calls for attention to gender equality throughout the education system in relation to access, content, teaching and learning context and practices, learning outcomes, and life and work opportunities. The UNESCO Strategy for gender equality in and through education (2019-2025) focuses on a system-wide transformation to benefit all learners equally in three key areas: better data to inform action, better legal and policy frameworks to advance rights and better teaching and learning practices to empower.

What you need to know about education and gender equality

"her education, our future" documentary film.

Released on 7 March for 2024 International Women’s Day, “Her Education, Our Future” is a documentary film following the lives of Anee, Fabiana, Mkasi and Tainá – four young women across three continents who struggle to fulfill their right to education.

This documentary film offers a spectacular dive into the transformative power of education and showcases how empowering girls and women through education improves not only their lives, but also those of their families, communities and indeed all of society.

Key figures

of which 122 million are girls and 128 million are boys

of which 56% are women

for every 100 young women

Empowering communities: UNESCO in action

Keeping girls in the picture

Everyone can play a role in supporting girls’ education

UNESCO’s new drive to accelerate action for girls’ and women’s education

2022 GEM Report Gender Report: Deepening the debate on those still left behind

Capacity building tools

- From access to empowerment: operational tools to advance gender equality in and through education

- Communication strategy: UNESCO guidance on communicating on gender equality in and through education

- Communication tools

- Keeping girls in the picture: youth advocacy toolkit

- Keeping girls in the picture: community radio toolkit

Monitoring SDG 4: equity and inclusion in education

Resources from UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring Report.

Related items

- Gender equality

- Policy Advice

- Girls education

- See more add

- High contrast

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

Girls' education, gender equality in education benefits every child..

- Girls' education

- Available in:

Investing in girls’ education transforms communities, countries and the entire world. Girls who receive an education are less likely to marry young and more likely to lead healthy, productive lives. They earn higher incomes, participate in the decisions that most affect them, and build better futures for themselves and their families.

Girls’ education strengthens economies and reduces inequality. It contributes to more stable, resilient societies that give all individuals – including boys and men – the opportunity to fulfil their potential.

But education for girls is about more than access to school. It’s also about girls feeling safe in classrooms and supported in the subjects and careers they choose to pursue – including those in which they are often under-represented.

When we invest in girls’ secondary education

- The lifetime earnings of girls dramatically increase

- National growth rates rise

- Child marriage rates decline

- Child mortality rates fall

- Maternal mortality rates fall

- Child stunting drops

Why are girls out of school?

Despite evidence demonstrating how central girls’ education is to development, gender disparities in education persist.

Around the world, 129 million girls are out of school, including 32 million of primary school age, 30 million of lower-secondary school age, and 67 million of upper-secondary school age. In countries affected by conflict, girls are more than twice as likely to be out of school than girls living in non-affected countries.

Worldwide, 129 million girls are out of school.

Only 49 per cent of countries have achieved gender parity in primary education. At the secondary level, the gap widens: 42 per cent of countries have achieved gender parity in lower secondary education, and 24 per cent in upper secondary education.

The reasons are many. Barriers to girls’ education – like poverty, child marriage and gender-based violence – vary among countries and communities. Poor families often favour boys when investing in education.

In some places, schools do not meet the safety, hygiene or sanitation needs of girls. In others, teaching practices are not gender-responsive and result in gender gaps in learning and skills development.

Gender equality in education

Gender-equitable education systems empower girls and boys and promote the development of life skills – like self-management, communication, negotiation and critical thinking – that young people need to succeed. They close skills gaps that perpetuate pay gaps, and build prosperity for entire countries.

Gender-equitable education systems can contribute to reductions in school-related gender-based violence and harmful practices, including child marriage and female genital mutilation .

Gender-equitable education systems help keep both girls and boys in school, building prosperity for entire countries.

An education free of negative gender norms has direct benefits for boys, too. In many countries, norms around masculinity can fuel disengagement from school, child labour, gang violence and recruitment into armed groups. The need or desire to earn an income also causes boys to drop out of secondary school, as many of them believe the curriculum is not relevant to work opportunities.

UNICEF’s work to promote girls’ education

UNICEF works with communities, Governments and partners to remove barriers to girls’ education and promote gender equality in education – even in the most challenging settings.

Because investing in girls’ secondary education is one of the most transformative development strategies, we prioritize efforts that enable all girls to complete secondary education and develop the knowledge and skills they need for life and work.

This will only be achieved when the most disadvantaged girls are supported to enter and complete pre-primary and primary education. Our work:

- Tackles discriminatory gender norms and harmful practices that deny girls access to school and quality learning.

- Supports Governments to ensure that budgets are gender-responsive and that national education plans and policies prioritize gender equality.

- Helps schools and Governments use assessment data to eliminate gender gaps in learning.

- Promotes social protection measures, including cash transfers, to improve girls’ transition to and retention in secondary school.

- Focuses teacher training and professional development on gender-responsive pedagogies.

- Removes gender stereotypes from learning materials.

- Addresses other obstacles, like distance-related barriers to education, re-entry policies for young mothers, and menstrual hygiene management in schools.

More from UNICEF

1 in 3 adolescent girls from the poorest households has never been to school

Let’s shape tech to be transformative

Gender-responsive digital pedagogies: A guide for educators

Stories of suffering and hope: Afghanistan and Pakistan

Catherine Russell reflects on her first field visit as UNICEF's Executive Director

Where are the girls and why it matters as schools reopen?

School closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic risk reversing the massive gains to girls’ education

Advancing Girls' Education and Gender Equality through Digital Learning

This brief note highlights how UNICEF will advance inclusive and transformative digital technology to enhance girls’ learning and skills development for work and life.

Reimagining Girls' Education: Solutions to Keep Girls Learning in Emergencies

This resource presents an empirical overview of what works to support learning outcomes for girls in emergencies.

e-Toolkit on Gender Equality in Education

This course aims to strengthen the capacity of UNICEF's education staff globally in gender equality applied to education programming.

Fixing the Broken Promise of Education for All

This report draws on national studies to examine why millions of children continue to be denied the fundamental right to primary education.

GirlForce: Skills, Education and Training for Girls Now

This report discusses persistent barriers girls face in the transition from education to the workforce, and how gender gaps in employment outcomes persist despite girls’ gains in education.

UNICEF Gender Action Plan (2022-2025)

This plan specifies how UNICEF will promote gender equality across the organization’s work, in alignment with the UNICEF Strategic Plan.

Global Partnership for Education

This partnership site provides data and programming results for the only global fund solely dedicated to education in developing countries.

United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative

UNGEI promotes girls’ education and gender equality through policy advocacy and support to Governments and other development actors.

- Student Outreach

- Research Support

- Executive Education

- News & Announcements

- Jobs & Opportunities

- Annual Reports

- Faculty Working Papers

- Building State Capability

- Colombia Education Initiative

- Evidence for Policy Design

- Reimagining the Economy

- Social Protection Initiative

- Past Programs

- Speaker Series

- Global Empowerment Meeting (GEM)

- NEUDC 2023 Conference

Closing the Gender Gap in Education

In this section, closing the gender gap in education: does it foretell the closing of the employment, marriage, and motherhood gaps, cid working paper no. 220.

Ina Ganguli, Ricardo Hausmann, and Martina Viarengo April 2011

In this paper we examine several dimensions of gender disparity for a sample of 40 countries using micro-level data. We start by documenting the reversal of the gender education gap and ranking countries by the year in which it reversed. Then we turn to an analysis of the state of other gaps facing women: we compare men and women’s labor force participation (the labor force participation gap), married and single women’s labor force participation (the marriage gap), and mothers’ and non-mother’s labor force participation (the motherhood gap). We show that gaps still exist in these spheres in many countries, though there is significant heterogeneity among countries in terms of the size of and the speed at which these gaps are changing. We also show the relationship between the gaps and ask how much the participation gap would be reduced if the gaps in other spheres were eliminated. In general, we show that while there seems to be a relationship between the decline of the education gap and the reduction of the other gaps, the link is rather weak and highly heterogeneous across countries.

Keywords: development, gender gap, education

JEL subject codes: O12, J16, I2

Read our research on: Gun Policy | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

What’s behind the growing gap between men and women in college completion.

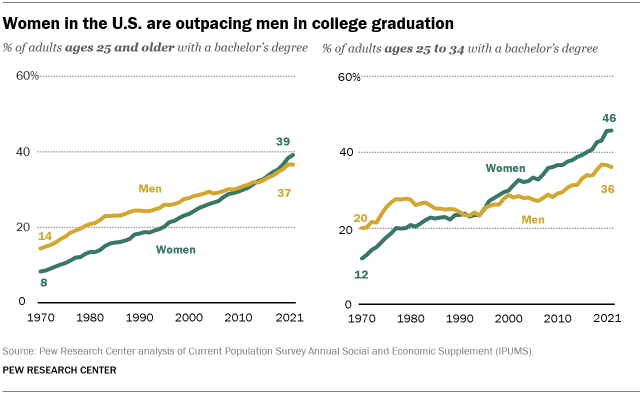

The growing gender gap in higher education – both in enrollment and graduation rates – has been a topic of conversation and debate in recent months. Young women are more likely to be enrolled in college today than young men, and among those ages 25 and older, women are more likely than men to have a four-year college degree. The gap in college completion is even wider among younger adults ages 25 to 34.

Women’s educational gains have occurred alongside their growing labor force participation as well as structural changes in the economy . The implications of the growing gap in educational attainment for men are significant, as research has shown the strong correlation between college completion and lifetime earnings and wealth accumulation .

To explore the factors contributing to the growing gender gap in college completion, we surveyed 9,676 U.S. adults between Oct. 18-24, 2021. Everyone who took part is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Data on rates of college completion came from a Center analysis of Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (IPUMS). The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the data collection for the 2020 ASEC. The response rate for the March 2020 survey was about 10 percentage points lower than in preceding months. Using administrative data, Census Bureau researchers have shown that nonresponding households were less similar to respondents than in earlier years. They also generated entropy balance weights to account for this nonrandom nonresponse. The 2020 ASEC figures presented used these supplementary weights.

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology .

A majority (62%) of U.S. adults ages 25 and older don’t have a four-year college degree, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of Current Population Survey data. But the reasons for not completing a four-year degree differ for men and women, according to a new Center survey of adults who do not have such a degree and are not currently enrolled in college.

Financial considerations are a key reason why many don’t attend or complete college. Among adults who do not have a bachelor’s degree and are not currently enrolled in school, roughly four-in-ten (42%) say a major reason why they have not received a four-year college degree is that they couldn’t afford college. Some 36% say needing to work to help support their family was a major reason they didn’t get their degree.

Overall, about three-in-ten adults who didn’t complete four years of college (29%) say a major reason for this is that they just didn’t want to, 23% say they didn’t need more education for the job or career they wanted, and 20% say they just didn’t consider getting a four-year degree. Relatively few (13%) adults without a bachelor’s degree say a major reason they didn’t pursue this level of education was that they didn’t think they’d get into a four-year college.

Men are more likely than women to point to factors that have more to do with personal choice. Roughly a third (34%) of men without a bachelor’s degree say a major reason they didn’t complete college is that they just didn’t want to. Only one-in-four women say the same. Non-college-educated men are also more likely than their female counterparts to say a major reason they don’t have a four-year degree is that they didn’t need more education for the job or career they wanted (26% of men say this vs. 20% of women).

Women (44%) are more likely than men (39%) to say not being able to afford college is a major reason they don’t have a bachelor’s degree. Men and women are about equally likely to say needing to work to help support their family was a major impediment.

The shares of men and women saying they didn’t consider going to college or they didn’t think they’d get into a four-year school are not significantly different.

The reasons people give for not completing college also differ across racial and ethnic groups. Among those without a bachelor’s degree, Hispanic adults (52%) are more likely than those who are White (39%) or Black (41%) to say a major reason they didn’t graduate from a four-year college is that they couldn’t afford it. Hispanic and Black adults without a four-year degree are more likely than their White counterparts to say needing to work to support their family was a major reason. There aren’t enough Asian adults without a bachelor’s degree in the sample to analyze this group separately.

While a third of White adults without a four-year degree say not wanting to go to school was a major reason they didn’t complete a four-year degree, smaller shares of Black (22%) and Hispanic (23%) adults say the same. White adults are also more likely to say not needing more education for the job or career they wanted is a major reason why they don’t have a bachelor’s degree.

In some instances, the gender gaps in the reasons for not completing college are more pronounced among White adults than among Black or Hispanic adults. About four-in-ten White men who didn’t complete four years of college (39%) say a major reason for this is that they just didn’t want to. This compares with 27% of White women without a degree. Views on this don’t differ significantly by gender for Black or Hispanic adults.

Similarly, while three-in-ten White men without a college degree say a major reason they didn’t complete college is that they didn’t need more education for the job or career they wanted, only 24% of White women say the same. Among Black and Hispanic non-college graduates, roughly similar shares of men and women say this was a major reason.

Among college graduates, men and women have similar views on the value of their degree

Looking at those who have graduated from college, men and women are equally likely to see value in the experience. Overall, 49% of four-year college graduates say their college education was extremely useful in terms of helping them grow personally and intellectually. Roughly equal shares of men (47%) and women (50%) express this view.

Some 44% of college graduates – including 45% of men and 43% of women – say their college education was extremely useful to them in opening doors to job opportunities. A somewhat smaller share of bachelor’s degree holders (38%) say college was extremely useful in helping them develop specific skills and knowledge that could be used in the workplace (38% of men and 40% of women say this).

There are differences by age on each of these items, as younger college graduates are less likely than older ones to see value in their college education. For example, only a third of college graduates younger than 50, compared with 45% of those 50 and older, say their college experience was extremely useful in helping them develop skills and knowledge that could be used in the workplace.

Note: Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology .

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

Fewer young men are in college, especially at 4-year schools

Education of muslim women is limited by economic conditions, not religion, the muslim gender gap in educational attainment is shrinking, higher education, gender & work, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Centre for Education and International Development (CEID), IOE

A forum for staff, students, alumni and guests to write about and around CEID's five thematic areas of engagement.

What do we mean by gender equality in education, and how can we measure it?

By CEID Blogger, on 18 May 2021

By Helen Longlands

Gender equality in education is a matter of social justice, concerned with rights, opportunities and freedoms. Gender equality in education is crucial for sustainable development, for peaceful societies and for individual wellbeing. At local, national and global levels, gender equality in education remains a priority area for governments, civil society and multilateral organisations. The United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals and 2020-2030 Decade of Action commit the global community to achieving quality education (Goal 4) and gender equality (Goal 5) by 2030. The G7 Foreign and Development Ministers, meeting this summer in the UK, have made fresh commitments to supporting gender equality and girls’ education , which build on those they made in 2018 and 2019 . Yet fulfilling these agendas and promises not only depends on galvanising sufficient support and resourcing but also on developing sufficient means of measuring and evaluating progress.

The urgency for gender equality in education has been compounded by the profound impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic, which has exposed, exacerbated and created new forms of intersecting inequalities and injustices associated with gender and education. School closures have resulted in millions more children out of school, many of whom may never return, particularly the poorest and most marginalised girls . While UNESCO estimates that over 11 million girls are at risk of not going back to school once the worst of the pandemic is over, the Malala Fund indicates this figure could be as high as 20 million . Cases of violence against women and children have also risen during the pandemic. A recent review by the Centre for Global Development of studies on low and middle income countries presents evidence of an increase in incidences of various forms of gender-based violence, including intimate partner violence, harassment, and violence against children. Assessment by UN Women connects this rise in violence to Covid-19 measures and consequences, including the closures of schools, suspension of community support systems, and increasing rates of unemployment and alcohol abuse. Meanwhile, heavier burdens of caregiving responsibilities during the pandemic, as well as reduced access to sexual and reproductive health knowledge and resources , limited availability of technology to support learning , and low levels of digital technology skills have gendered dimensions and risk further widening existing gender inequalities and power imbalances associated with education.

The effects of the pandemic add to the challenges of achieving gender equality in education and to the complexities involved in evaluating progress towards it. As we continue to develop and extend response, recovery and sustainability initiatives, to build back better , it is important to have explicit and honest discussions about gender and other intersecting inequalities in education. And it is vital to ensure we have robust and reliable ways of identifying, evaluating and holding people to account for these inequalities and their underlying causes in order to build more just and resilient societies. How we do this, however, is not straightforward and presents many conceptual and practical challenges around understanding, accessing and utilising the information, resources and approaches we need. What do we mean when we talk about gender equality in education, how can we measure progress towards it, and how will we know when we achieve it?

The AGEE project’s theoretical and methodological approach draws on key ideas from the capability approach, including the importance of public debate and democratic deliberation, recognition of how inequalities, opportunities and freedoms connect to the complexities of the physical, political and social environment as well as the distribution of resources, and a focus on both the interpersonal and the individual. We see these ideas as crucial components to identifying, understanding and meaningfully measuring gender inequalities and equality in education in diverse local contexts in ways that capture both unique and more general issues as well as longstanding and emerging concerns.

Thus our aim is to help refocus the policy attention beyond gender parity in education to a more substantive understanding and recognition of what gender equality in education could or should entail within and across different contexts, and provide clarity on the data needed for public policy. Gender parity comprises a simple ratio of girls to boys or women to men in a given aspect of education, such as enrolment, participation, attainment or teacher deployment. Gender parity is a clear and uncomplicated measure, which makes it appealing to policymakers and practitioners, and has led to its widespread use as a measure of gender equality in education in national and global development frameworks. This is seen in many of the targets for SDG4 on education and previously in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (2000-2015). However, gender parity is also an inadequate measure on its own because it is unable to capture more complex forms of gender inequality, the conditions and practices that underpin them, the ways in which they intersect with other forms of inequality and injustice, and the short and longer term consequences for individuals and societies. While it is important to ensure all children can access, attend and complete school, which are all issues that gender parity can monitor, it cannot measure issues such as girls’ or boys’ lived experiences of gender discrimination or violence in and around school, or gender inequalities associated with curricula, learning materials, pedagogic approaches or work practices.

Ongoing consultations and debates with stakeholders at community, national and international level are thus key components of AGEE’s research approach. Through them, we have sought to develop a deeper understanding of local, national and global forms of gender inequality and injustice in education and the ways these interconnect. We have scrutinised whether or not existing measurement techniques document this in order to enhance work on gender equality in policy and practice. Over the past few years, through workshops, interviews, technical meetings, academic papers, conference presentations, seminars and teaching, we have engaged in critical participatory dialogue with a wide range of key national and international stakeholders in education and gender, including representatives from governments, national statistics offices, civil society, international organisations, academics and students. This dialogue has explored and interrogated understandings of and debates around gender, accountability, measurement and data, and collated information on the range of factors, relationships, conditions and available data associated with gender equality in education.

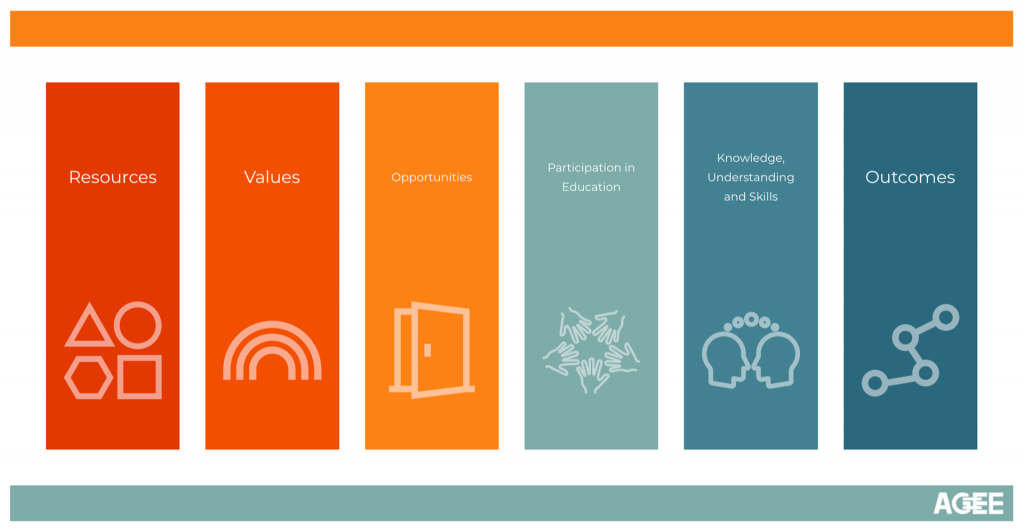

Through this in-depth participatory process, we have developed, adapted and refined the AGEE Framework. The Framework is designed to be robust and comprehensive as well as flexible and adaptable, in order both to capture complex, enduring and widespread forms of inequalities, and to be responsive to local characteristics and changing conditions, including forms of crisis. The AGEE Framework comprises six interconnected domains for monitoring and evaluating gender equality in education: Resources; Values; Opportunities; Participation in Education; Knowledge, Understanding and Skills; and Outcomes. And we have identified a number of indicators and related existing or potential data sources to populate these domains.

If you would like to learn more about the AGEE project and engage with our work to support gender equality in education, please visit our website: www.gendereddata.org , where you can find more information about our research and the AGEE Framework, and join our community of practice.

Join the special event on May 27, 2021 where the AGEE Framework will be presented in detail : The politics of measuring gender equality in education: Perspectives for the G7

Acknowledgements:

Members of the AGEE project team: Elaine Unterhalter (UCL and AGEE PI), Rosie Peppin Vaughan (UCL), Relebohile Moletsane (UKZN), Esme Kadzamira (University of Malawi) and Catherine Jere (UEA).

Filed under CEID , Gender , Inequalities

One Response to “What do we mean by gender equality in education, and how can we measure it?”

your blog is very useful and your content ideas is wonderful nice job…

Leave a Reply

Name (required)

Mail (will not be published) (required)

CEID | Twitter | Facebook

Recent Posts

- Demystifying Doctoral Research Fieldwork – “Expecting the Unexpected”

- A Call for Peace with Justice in the Occupied Palestinian Territories and Israel – recognising the pivotal role of education

- The perfect immigration policy? ‘Educate’ children of migrants to pull up the drawbridge

- Learning the history, identity, and education of Tibetans-in-exile through Tibetan Terms

- The Elephant in the (Class)room

Subscribe by Email

Completely spam free, opt out any time.

Please, insert a valid email.

Thank you, your email will be added to the mailing list once you click on the link in the confirmation email.

Spam protection has stopped this request. Please contact site owner for help.

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Gender Disparity in Education: An In-Depth Examination

By GGI Insights | April 13, 2024

Table of contents

This article aims to explore the concept of gender disparity in education, its historical origins, current state globally, contributing factors, impact, case studies, strategies to address it, and future predictions. By examining these aspects, we can comprehensively understand this complex issue and its implications for individuals and societies.

Understanding the Concept of Gender Disparity in Education

Gender disparity in education refers to the unequal access and opportunities for education between males and females. It involves differences in enrollment rates, completion rates, quality of education , and subject choices. This disparity has deep-rooted historical origins and continues to persist today, posing challenges to achieving gender equality and inclusive education.

Gender disparity in education is a multifaceted issue affecting individuals, communities, and societies. It encompasses the differences in enrollment rates and the barriers hindering girls and women from accessing quality education. These barriers include cultural norms, discriminatory practices, lack of funding, and societal expectations.

Definition of Gender Disparity

Gender disparity in education is characterized by the differences in educational opportunities, outcomes, and experiences between males and females. It encompasses disparities in enrollment, dropout, literacy, academic achievement, and access to tertiary education.

Enrollment rates, one aspect of gender disparity, reflect the number of individuals from each gender enrolled in educational institutions. In many parts of the world, girls and women face significant challenges in accessing education, resulting in lower enrollment rates than their male counterparts. This disparity affects individuals' personal development and has broader societal implications, including economic growth and social progress.

More than merch, the 'Ignite Potential' collection is a statement. Wear your passion, knowing 30% fuels quality education initiatives . Shop now, ignite possibility!

Dropout rates, another dimension of gender disparity in education, refer to the number of students who leave school before completing their education. Dropout rates often disproportionately affect girls and women due to factors such as early marriage, pregnancy, financial constraints, and cultural norms prioritizing boys' education over girls'. These factors perpetuate gender disparities and hinder girls' and women's personal and professional growth opportunities. This dropout problem persists across various levels of education , from primary to higher education, affecting females disproportionately due to a range of social and economic barriers.

Literacy rates, a crucial indicator of educational attainment, also reflect gender disparities. In many parts of the world, women have lower literacy rates than men, limiting their access to information, opportunities, and empowerment. Addressing this disparity requires improving access to education and addressing societal attitudes and norms perpetuating gender inequalities.

Academic achievement is another aspect of gender disparity in education. While girls and women have made significant strides in academic performance in recent years, there are still disparities in certain subjects and fields. Stereotypes and biases can influence subject choices, leading to the underrepresentation of girls and women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. Promoting gender equality in education requires challenging these stereotypes and creating inclusive learning environments to encourage girls and women to pursue their interests and talents.

Access to tertiary education, such as universities and colleges, is another area where gender disparities persist. In many parts of the world, women face barriers such as limited opportunities, financial constraints, and societal expectations that discourage them from pursuing higher education. Closing this gap requires addressing systemic barriers and promoting policies that ensure equal access and opportunities for all.

Historical Overview of Gender Disparity in Education

Throughout history, gender disparity in education has been prevalent. Societal norms and cultural beliefs have often reinforced traditional gender roles and restricted females' access to education. For centuries, girls and women have faced barriers such as limited access to schools, discriminatory practices, lack of funding, and societal expectations to prioritize household responsibilities over education.

However, it is important to acknowledge the progress in addressing gender disparity in education over the years. Efforts to promote gender equality and inclusive education have increased access to education for girls and women in many parts of the world. Initiatives such as scholarships, girls' education campaigns, and policy reforms have played a crucial role in narrowing the gender gap in education.

Despite these advancements, challenges persist, particularly in developing countries and marginalized communities. Poverty, conflict, cultural norms, and lack of infrastructure hinder girls' and women's access to education. Addressing these challenges requires a multi-faceted approach that involves collaboration between governments, international organizations, civil society, and local communities.

Achieving gender equality in education goes beyond increasing enrollment rates. It requires addressing the underlying factors perpetuating gender disparities, such as gender-based violence, early marriage, and unequal distribution of resources. Creating safe and inclusive learning environments, promoting gender-sensitive curricula, and empowering girls and women is essential to sustainable change.

In conclusion, gender disparity in education is a complex issue that requires comprehensive and sustained efforts to address. It is not only a matter of equal access to education but also about challenging societal norms, promoting gender equality, and empowering girls and women to reach their full potential. Investing in inclusive education systems can create a more equitable and just society for all.

The Current State of Gender Disparity in Education Globally

Although progress has been made in promoting gender equality in education, significant disparities persist globally.

Gender equality in education is a fundamental human right and key to social and economic development. It is essential for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals set by the United Nations, particularly Goal 4: Quality Education, which aims to ensure inclusive and equitable education for all.

However, despite efforts to bridge the gender gap in education, substantial disparities still need to be addressed.

Gender Disparity in Primary and Secondary Education

Gender disparities in primary and secondary education vary across countries and regions. In some nations, males have a higher enrollment rate, while females face greater barriers to accessing education in others.

These disparities can be attributed to a multitude of factors. Cultural biases play a significant role, as societies may prioritize boys' education over girls. Limited investment in girls' education is another contributing factor, as resources and opportunities are often directed toward male students.

Early marriage is also a major obstacle to girls' education. In some communities, girls are forced into marriage at a young age, preventing them from continuing their studies. This perpetuates a cycle of gender inequality and limits their prospects.

The lack of school infrastructure is another challenge that disproportionately affects girls. Many schools lack proper sanitation facilities, making it difficult for girls to attend school, especially during menstruation. This not only hinders their education but also puts their health at risk. Understanding how AI is changing education can help develop more accessible and inclusive educational tools and platforms, particularly benefiting girls in regions where educational infrastructure is lacking.

Gender-based violence is a pervasive issue affecting girls' education access. In some societies, girls face physical and sexual violence on their way to or at school, creating a hostile and unsafe learning environment. I n addition to addressing safety concerns, promoting affordable education is crucial to ensure that economic barriers do not further widen the gender gap in educational access and opportunities.

Gender Disparity in Higher Education

While enrollment rates have improved for females in higher education, gender disparities still exist. Females often face challenges accessing certain disciplines, such as science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), and are underrepresented in leadership positions within academic institutions.

Discrimination plays a significant role in perpetuating gender disparities in higher education. Women may face biases and stereotypes that discourage them from pursuing certain fields of study or hinder their career advancement. Socio-cultural norms also contribute to these disparities, as traditional gender roles may limit women's educational opportunities.

The lack of role models is another factor that affects women's participation in higher education. When women do not see other women succeeding in their chosen fields, it can be discouraging and make them question their abilities and potential.

Additionally, limited financial resources pose a significant barrier for women seeking higher education. Higher tuition fees, lack of scholarships, and limited access to financial support often make it difficult for women to pursue advanced degrees.

Addressing gender disparity in education requires a multi-faceted approach. It involves challenging cultural norms and biases, increasing investment in girls' education, promoting gender-responsive school environments, and providing targeted support and resources for girls and women in their pursuit of education.

By ensuring equal access to education for all, regardless of gender, we can empower individuals, communities, and societies to thrive and contribute to a more equitable and sustainable world.

Factors Contributing to Gender Disparity in Education

The causes of gender disparity in education vary across regions and contexts. Understanding these contributing factors is crucial for developing effective strategies to address the issue.

Gender disparity in education is a complex issue influenced by various factors. Let's explore some additional details to gain a deeper understanding of this important topic.

Socioeconomic Factors

Socioeconomic factors, such as poverty, play a significant role in perpetuating gender disparities in education. Limited financial resources often result in families prioritizing the education of male children over females. This preference stems from the belief that investing in a son's education will yield better returns for the family.

However, it is crucial to recognize that girls from disadvantaged backgrounds face additional hurdles. They contend with limited financial resources and lack access to clean water, sanitation facilities, and electricity. These challenges make it even more difficult for girls to pursue education.

Early marriages are prevalent in many societies, especially among impoverished communities. Girls are often forced into marriage at a young age, disrupting their educational journey. Additionally, socioeconomic pressures compel girls to engage in income-generating activities, limiting their access to education.

Cultural and Religious Factors

Cultural and religious norms and beliefs heavily influence gender disparities in education. Societal expectations, traditional gender roles, and gender stereotypes restrict educational opportunities for girls. In many cultures, girls are expected to prioritize household chores and caregiving responsibilities over their education.

Early marriage practices, often rooted in cultural and religious traditions, significantly hinder girls' education. When girls are married off at a young age, their educational aspirations are curtailed, perpetuating the cycle of gender inequality. Expanding access to vocational training can offer an alternative path for girls who may not pursue traditional academic routes, providing them with valuable skills for the job market.

Gender-based violence remains pervasive, hindering girls' access to education. Fear of violence and harassment on the way to school or within educational institutions deters girls from pursuing their studies.

Policy and Institutional Factors

The lack of appropriate policies, gender-responsive education systems, and institutions negatively impacts gender equality in education. Insufficient funding for education, especially in developing countries, leads to inadequate resources and infrastructure, disproportionately affecting girls' access to quality education.

The absence of targeted interventions addressing gender disparities in education perpetuates the problem. Without specific measures to empower girls and ensure their equal participation in education, the gender gap continues to widen.

Discriminatory practices within educational institutions also contribute to the gender gap in education. Gender bias in curricula, textbooks, and classroom interactions can reinforce stereotypes and limit girls' educational opportunities. It is essential to create inclusive learning environments that challenge gender norms and promote equal opportunities for all students.

By understanding the multifaceted nature of the factors contributing to gender disparity in education, we can work towards implementing comprehensive strategies that address these challenges. Achieving gender equality in education is a matter of human rights and a social and economic development catalyst.

The Impact of Gender Disparity in Education

Gender disparity in education has far-reaching consequences for individuals, communities, and societies. It hinders social and economic development, perpetuates inequality, and limits individuals' opportunities.

When discussing the impact of gender disparity in education, it is crucial to consider its effects on economic development. The exclusion of females from educational opportunities results in a significant loss of human capital. Societies are wasting their potential and talent by denying girls access to education. This hampers economic growth and perpetuates a cycle of poverty and inequality.

Investing in girls' education has proven to yield positive economic outcomes. Providing girls with equal educational opportunities reduces poverty, improved labor force participation, and increased productivity. Educated women are more likely to secure higher-paying jobs, contribute to the economy through entrepreneurship, and become financially independent.

However, the impact of gender disparity in education extends beyond economic development. It also has profound effects on social development. Unequal access to education perpetuates gender norms and stereotypes, limiting opportunities for girls and women to contribute to society and participate fully in decision-making processes.

When girls are denied education, it reinforces the notion that their role is confined to domestic responsibilities and diminishes their potential to become leaders, innovators, and agents of change. This perpetuates a cycle of gender inequality and restricts the overall progress of society.

On the other hand, when girls receive an education, it has a transformative effect on society. Educated females are more likely to have healthier families, make informed choices regarding reproduction, and contribute to community development. They become empowered individuals who can challenge societal norms and advocate for gender equality.

Educated women are more likely to raise educated children. By breaking the cycle of illiteracy and ignorance, they create a ripple effect that benefits future generations. This improves the overall well-being of families and strengthens the social fabric of communities.

In conclusion, gender disparity in education has wide-ranging economic and social development impacts. By investing in girls' education and ensuring equal access to educational opportunities, societies can break the cycle of inequality, empower women, and foster sustainable development for all.

Case Studies of Gender Disparity in Education

Examining specific case studies helps shed light on the diverse challenges and experiences related to gender disparity in education.

Gender disparity in education is a complex issue affecting developing and developed countries. While the nature of the problem may vary, the impact is significant and requires attention.

Gender Disparity in Education in Developing Countries

In many developing countries, gender disparities in education are pronounced. Poverty, cultural norms, limited resources, and societal biases contribute to these disparities.

For example, in some rural areas of Sub-Saharan Africa, girls face multiple barriers to education. These barriers include long distances to schools, lack of proper sanitation facilities, early marriage, and cultural beliefs prioritizing boys' education over girls'. These challenges perpetuate a cycle of gender inequality and hinder progress toward achieving universal education.

Efforts to address this issue include targeted interventions, scholarships, public awareness campaigns, and infrastructure improvements. Non-governmental organizations, international agencies, and governments collaborate to provide scholarships to girls, build schools closer to communities, and promote the importance of education for all children regardless of gender.

Public awareness campaigns aim to challenge cultural norms and address societal biases perpetuating gender disparities in education. These campaigns highlight the benefits of educating girls, such as improved health outcomes, reduced poverty rates, and increased economic growth.

Gender Disparity in Education in Developed Countries

While gender disparities in education are less prevalent in developed countries, challenges still exist. Females sometimes face barriers in accessing certain disciplines or pursuing leadership roles within educational institutions.

For instance, women are underrepresented in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). This underrepresentation can be attributed to various factors, including stereotypes, lack of female role models, and unconscious biases. These barriers limit women's opportunities to pursue careers in STEM fields and contribute to a gender gap in these industries.

Promoting gender-inclusive curricula, equal opportunities for career advancement, and dismantling institutional biases are vital for addressing this disparity. Educational institutions are implementing initiatives encouraging girls' participation in STEM, such as mentorship programs, outreach activities, and scholarship opportunities. Additionally, organizations and companies are working towards creating inclusive workplaces that value diversity and provide equal opportunities for career growth.

It is crucial to recognize that gender disparities in education are not limited to developing countries. By addressing these disparities globally, we can create a more inclusive and equitable educational system that benefits individuals, communities, and societies.

Strategies to Address Gender Disparity in Education

Addressing gender disparity in education requires comprehensive strategies at various levels, including policy, institutional, and community-based interventions.

Gender disparity in education is a global issue affecting millions of girls and women worldwide. While progress has been made in recent years, there is still a long way to go in achieving gender equality in education. Governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and local communities must work together to implement effective strategies to bridge this gap.

Government Policies and Interventions

Governments are crucial in reducing gender disparities by implementing policies promoting equal education access. This includes eliminating discriminatory laws, increasing funding for girls' education, and adopting gender-responsive education systems.

One example of a government policy that has successfully addressed gender disparity in education is the "Girls' Education Initiative" implemented by the government of a developing country. This initiative focused on providing scholarships for girls from low-income families, ensuring they access quality education. Additionally, the government also implemented a gender-responsive curriculum that aims to challenge traditional gender roles and stereotypes.

Governments can also collaborate with international organizations and donors to secure additional funding for girls' education. This funding can be used to build schools in rural areas, provide educational materials, and train teachers on gender-responsive teaching methods.

Role of Non-Governmental Organizations

Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations contribute significantly to addressing gender disparities in education. They provide support through initiatives like girl child scholarships, mentorship programs, awareness campaigns, and advocating for policy reforms.

One notable NGO that has significantly addressed gender disparity in education is "Education for All.” This organization provides scholarships to girls from marginalized communities, ensuring they receive a quality education. In addition to financial support, Education for All also provides mentorship programs, where girls are paired with successful women who serve as role models and provide guidance.

NGOs also play a crucial role in raising awareness about the importance of girls' education. They organize campaigns and events to highlight the benefits of educating girls for the individual and the entire community. NGOs can help change mindsets and break down barriers that prevent girls from accessing education by engaging with local communities.

Community-Based Initiatives

Engaging local communities is essential for tackling gender disparities in education. Initiatives such as parent-teacher associations, community awareness programs, and empowering local leaders can help change cultural norms and promote equal educational opportunities.

In many communities, traditional gender roles and stereotypes are deeply ingrained, making it difficult for girls to access education. However, community-based initiatives can challenge these norms and create an environment where girls are encouraged to pursue their education.

One successful community-based initiative is the establishment of parent-teacher associations in rural areas. These associations bring together parents, teachers, and community leaders to discuss and address girls' challenges in accessing education. Parents can voice their concerns through these associations and work with teachers and community leaders to find solutions.

Community awareness programs can change mindsets and attitudes toward girls' education. These programs can include workshops, seminars, and awareness campaigns that highlight the benefits of educating girls and the negative consequences of gender disparities in education.

Empowering local leaders, especially women leaders, is also an effective strategy to address gender disparity in education. When women hold positions of power and influence in the community, they can advocate for girls' education and work towards dismantling barriers preventing them from accessing education.

The Future of Gender Disparity in Education

It is vital to anticipate future trends and challenges in addressing gender disparity in education.

Predicted Trends and Challenges

Rapid technological advancements, changing job markets, and evolving societal norms present opportunities and challenges in promoting gender equality in education.

Economic disparities, conflicts, climate change, and global health crises can exacerbate gender disparities and hinder educational progress.

Potential Solutions and Innovations

To overcome future challenges, innovative solutions are required. This includes leveraging technology to expand educational access, promoting STEM education for girls, strengthening partnerships between various stakeholders, and integrating gender equality into education policies and curricula.

Investment in scalable and sustainable interventions, supported by research and data-driven approaches, can drive progress toward achieving gender parity in education.

Examining gender disparity in education reveals the complex web of factors influencing females' access to and quality of education. It is an issue that requires continuous attention and concerted efforts from governments, NGOs, communities, and individuals.

By addressing the root causes, promoting gender-responsive policies, and ensuring equal opportunities for all, societies can unlock the full potential of individuals, foster social and economic development, and pave the way for a more inclusive and equitable future.

Popular Insights:

Shop with purpose at impact mart your purchase empowers positive change. thanks for being the difference.

Customer Onboarding: Proven Techniques for Seamless Client Integration

Customer journey: optimizing interactions for lasting customer loyalty, email open rates: enhancing the readership of your marketing emails, revenue: the fundamental pillar of business viability and growth, marketing strategies: craft dynamic approaches for business expansion, startup school: accelerating your path to entrepreneurial success, ecommerce marketing strategy: data-driven tactics for enhanced loyalty, hubspot crm review: a comprehensive look into what makes hubspot great, hubspot growth suite: catalyzing your company growth with integration, hubspot service hub: taking superb customer service to the next level.

Publications

- Journal Articles

- Books: Books, Chapters, Reviews

- Working Papers

- Gender Achievement Gaps in U.S. School Districts

Sean F. Reardon

Demetra Kalogrides

Anne Podolsky

Rosalía C. Zárate

In the first systematic study of gender achievement gaps in U.S. school districts, we estimate male-female test score gaps in math and English Language Arts (ELA) for nearly 10,000 school districts in the U.S. We use state accountability test data from third through eighth grade students in the 2008-09 through 2014-15 school years. The average school district in our sample has no gender achievement gap in math, but a gap of roughly 0.23 standard deviations in ELA that favors girls. Both math and ELA gender achievement gaps vary among school districts and are positively correlated – some districts have more male-favoring gaps and some more female-favoring gaps. We find that math gaps tend to favor males more in socioeconomically advantaged school districts and in districts with larger gender disparities in adult socioeconomic status. These two variables explain about one fifth of the variation in the math gaps. However, we find little or no association between the ELA gender gap and either socioeconomic variable, and we explain virtually none of the geographic variation in ELA gaps.

To download a data file with the gender achievement gap estimates produced in this paper, please click here to sign the data use agreement. Upon signing, you will be redirected to the Stanford Education Data Archive where you can download the data file from this paper.

Primary Research Area:

- Poverty and Inequality

Topic Areas:

- Educational Equity

- Stanford Education Data Archive

APA Citation

Media mentions, you are here.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

The Gender Gap Is Taking Us to Unexpected Places

By Thomas B. Edsall

Mr. Edsall contributes a weekly column from Washington, D.C., on politics, demographics and inequality.

In one of the most revealing studies in recent years, a 2016 survey of 137,456 full-time, first-year students at 184 colleges and universities in the United States, the U.C.L.A. Higher Education Research Institute found “the largest-ever gender gap in terms of political leanings: 41.1 percent of women, an all-time high, identified themselves as liberal or far left, compared to 28.9 percent of men.”

The institute has conducted freshmen surveys every year since 1966. In the early days, until 1980, men were consistently more liberal than women. In the early and mid-1980s, the share of liberals among male and female students was roughly equal, but since 1987, women have been more liberal than men in the first year of college.

While liberal and left identification among female students reached a high in 2016, male students remained far below their 1971 high, which was 44 percent.

Along parallel lines, a Knight Foundation survey in 2017 of 3,014 college students asked: “If you had to choose, which do you think is more important, a diverse and inclusive society or protecting free speech rights.”

Male students preferred protecting free speech over an inclusive and diverse society by a decisive 61 to 39. Female students took the opposite position, favoring an inclusive, diverse society over free speech by 64 to 35.

Majorities of both male and female college students in the Knight survey support the view that the First Amendment should not be used to protect hate speech, but the men were more equivocal, at 56 to 43, than women, at 71 to 29.

The data on college students reflects trends in the electorate at large. The Pew Research Center provided The Times with survey data showing that among all voters, Democrats are 56 percent female and 42 percent male, while Republicans are 52 percent male and 48 percent female, for a combined gender gap of 18 points. Pew found identical gender splits among voters who identify as liberal and those who identify as conservative.

“Significant gender differences in party identification have been evident since the early 1980s,” according to the Rutgers Center for American Women and Politics , which provides data on the partisanship of men and women from 1952 to the present day.

It’s clear from all this that the political engagement of women is having a major impact on the social order, often in ways that are not fully understood.

Take the argument made in the 2018 paper “ The Suffragist Peace ” by Joslyn N. Barnhart of the University of California-Santa Barbara, Allan Dafoe at the Center for the Governance of AI , Elizabeth N. Saunders of Georgetown and Robert F. Trager of U.C.L.A.:

Preferences for conflict and cooperation are systematically different for men and women. At each stage of the escalatory ladder, women prefer more peaceful options. They are less apt to approve of the use of force and the striking of hard bargains internationally, and more apt to approve of substantial concessions to preserve peace. They impose higher audience costs because they are more approving of leaders who simply remain out of conflicts, but they are also more willing to see their leaders back down than engage in wars.

The increasing incorporation of women into “political decision-making over the last century,” Barnhart and her co-authors write, raises “the question of whether these changes have had effects on the conflict behavior of nations.”

Their answer: “We find that the evidence is consistent with the view that the increasing enfranchisement of women, not merely the rise of democracy itself, is the cause of the democratic peace.”

Put another way, “the divergent preferences of the sexes translate into a pacifying effect when women’s influence on national politics grows” and “suffrage plays a direct and important role in generating more peaceful interstate relations by altering the political calculus of democratic leaders.”

Barnhart added by email:

The important thing to remember here is that with any trait, we are talking about averages and distributions and not categorical distinctions. Some men will have lesser preference for the use of force than some women and vice versa. The distribution of traits among the two genders overlaps. So we shouldn’t expect perfect partisan distinction.

Other consequential shifts emerged as women’s views began to change and they became more involved in politics.

Dennis Chong , a political scientist at the University of Southern California, wrote by email that “a gender gap in political tolerance, with women being somewhat more willing to censor controversial and potentially harmful ideas, goes back to the earliest survey research on the subject in the 1950s.”

There are a number of possible explanations, Chong said, including “stronger religious and moral attitudes among women; lesser political involvement resulting in weaker support for democratic norms; social psychological factors such as intolerance of ambiguity and uncertainty which translate to intolerance for political and social nonconformity; and greater susceptibility to feelings of threats posed by unconventional ideas and groups.”

Studies using moral foundations theory , Chong continued, have

found broad value differences between men and women. Women score higher on values defined by care, fairness, benevolence, and protecting the welfare of others, reflecting greater empathy and preference for cooperative social relations. In today’s debates over free speech and cancel culture, these social psychological and value differences between men and women are in line with surveys showing that women are more likely than men to regard hate speech as a form of violence rather than expression, to support laws against divisive hate speech, and to be skeptical that the right to free speech protects the disadvantaged more than the majority.

In addition, Chong said, “Women are also more likely than men to believe that colleges ought to protect students from exposure to controversial speakers whose ideas may create an inhospitable learning environment.”

Steven Pinker , a professor of psychology at Harvard, writes in his book “ The Better Angels of Our Nature ,” that “the most fundamental empirical generalization about violence” is that

it is mainly committed by men. From the time they are boys, males play more violently than females, fantasize more about violence, consume more violent entertainment, commit the lion’s share of violent crimes, take more delight in punishment and revenge, take more foolish risks in aggressive attacks, vote for more warlike policies and leaders, and plan and carry out almost all the wars and genocides.

Pinker continues:

Feminization need not consist of women literally wielding more power in decisions on whether to go to war. It can also consist in a society moving away from a culture of manly honor, with its approval of violent retaliation for insults, toughening of boys through physical punishment, and veneration of martial glory.

In an email, Pinker wrote:

We’re seeing two sets of forces that can pull in opposite directions. One set comprises the common interests of men on the one hand and women on the other. Men tend to be more obsessed with status and dominance and are more willing to take risks to compete for them; women are more likely to prize health and safety and to reduce conflict. The ultimate (evolutionary) explanation is that for much of human prehistory and history successful men and coalitions of men potentially could multiply their mates and offspring, who had some chance of surviving even if they were killed, whereas women’s lifetime reproduction was always capped by the required investment in pregnancy and nursing, and motherless children did not survive.

“ Mapping the Moral Domain ,” a 2011 paper by Jesse Graham , a professor of management at the University of Utah, and five colleagues, found key differences between the values of men and women, especially in the case of the emphasis women place on preventing harm , especially harm to the marginalized and those least equipped to protect themselves.

I asked Jonathan Haidt , a social psychologist at N.Y.U.’s Stern School of Business, about the changing political role of women. He emailed back:

In general, when looking at sex differences in outcomes, it is helpful to remember that differences between men and women on values and cognitive abilities are generally small, while differences between men and women in the activities that interest them, and in their relational styles (especially involving conflict) are often large.

When the academic world opened up to women in the 1970s and 1980s, Haidt continued, “women flooded into some areas but showed less interest in others. In my experience, having entered in the 1990s, the academic culture of predominantly female fields is very different from those that are predominantly male.”

Haidt noted:

Boys and men enjoy direct status competition and confrontation, so the central drama of male-culture disciplines is ‘“Hey, Jones says his theory is better than Smith’s; let’s all gather around and watch them fight it out, in a colloquium or in dueling journal articles.” In fact, I’d say that many of the norms and institutions of the Anglo-American university were originally designed to harness male status-seeking and turn it into scholarly progress.

Women are just as competitive as men, Haidt wrote, “but they do it differently.”

He cited a 2013 paper, “ The development of human female competition: allies and adversaries ,” by Joyce Benenson , of Harvard’s department of human evolutionary biology. In it, Benenson writes:

From early childhood onwards, girls compete using strategies that minimize the risk of retaliation and reduce the strength of other girls. Girls’ competitive strategies include avoiding direct interference with another girl’s goals, disguising competition, competing overtly only from a position of high status in the community, enforcing equality within the female community and socially excluding other girls.

In summary, Benenson wrote:

From early childhood through old age, human females’ reproductive success depends on provisioning, protecting and nurturing first younger siblings, then their own children and grandchildren. To safeguard their health over a lifetime, girls use competitive strategies that reduce the probability of physical retaliation, including avoiding direct interference with another girl’s goals and disguising their striving for physical resources, alliances and status.

In a November 2021 paper, “ Self-Protection as an Adaptive Female Strategy ,” Benenson, Christine E. Webb and Richard W. Wrangham , all of the department of human evolutionary biology, report that they

found consistent support for females’ responding with greater self-protectiveness than males. Females mount stronger immune responses to many pathogens; experience a lower threshold to detect, and lesser tolerance of, pain; awaken more frequently at night; express greater concern about physically dangerous stimuli; exert more effort to avoid social conflicts; exhibit a personality style more focused on life’s dangers; react to threats with greater fear, disgust and sadness; and develop more threat-based clinical conditions than males.

These differences manifest in a number of behaviors and characteristics, Benenson, Webb and Wrangham argue:

We found that females exhibited stronger self-protective reactions than males to important biological and social threats; a personality style more geared to threats; stronger emotional responses to threat; and more threat-related clinical conditions suggestive of heightened self-protectiveness. That females expressed more effective mechanisms for self-protection is consistent with females’ lower mortality and greater investment in child care compared with males.” In addition, “females more than males exhibit a lower threshold for detecting many sensory stimuli; remain closer to home; overestimate the speed of incoming stimuli; discuss threats and vulnerabilities more frequently; find punishment more aversive; demonstrate higher effortful control and experience deeper empathy; express greater concern over friends’ and romantic partners' loyalty; and seek more frequent help.

In an email, Benenson added another dimension to the discussion of sex roles in organizational politics:

From an early age, women clearly dislike group hierarchies of same-sex individuals more than men do. Thus, while boys and men are more willing to compete directly with both higher and lower status individuals, girls and women prefer to interact with same-sex individuals of similar status. This does not mean however that girls and women don’t care about status as much as boys and men do. For both sexes, high status increases the probability that one lives longer and so do one’s children. The result of these two somewhat conflicting motives is that girls and women seek high status but disguise this quest by avoiding direct contests. This gender difference likely impacts how women seek to shape organizational culture.

The strategies Benenson and her colleagues describe, Haidt pointed out,

lead to a different kind of conflict. There is a greater emphasis on what someone said which hurt someone else, even if unintentionally. There is a greater tendency to respond to an offense by mobilizing social resources to ostracize the alleged offender.

In “ Feminist and Anti-Feminist Identification in the 21st Century United States ,” Laurel Elder , Steven Greene and Mary-Kate Lizotte , political scientists at Hartwick College, North Carolina State University and Augusta University, analyzed the responses of those who identified themselves as feminists or anti-feminists in 1992 and 2016.

Based on surveys conducted by American National Election Studies, Elder, Greene and Lizotte found that the total number of voters saying that they were feminists grew from 28 percent to 34 percent over that period. The growth was larger among women, 29 percent to 50 percent, than among men, 18 percent to 25 percent.

Some of the biggest gains were among the young, 18-to-24-year-olds, doubling from 21 percent to 42 percent. Most striking is the data revealing the antithetical trends between women with college degrees, whose self-identification as feminist rose from 34 percent to 61 percent, in contrast to men with college degrees, whose self-identification as feminist fell from 37 percent to 35 percent.

Anti-feminist identity, the authors found,

is not just a mirror image of feminist identity but its own distinctive social identity. A striking difference between feminist and anti-feminist identification is that while gender is a huge driver in feminist identification in 2016, there is essentially no gender gap among anti-feminists. Indeed, bivariate analysis shows that 16 percent of women and 17 percent of men identify as anti-feminists.

In addition, Elder, Greene and Lizotte wrote, “while young people were more likely to identify as feminists than older generations in 2016, young people, particularly young women, also have a higher level of anti-feminist identification compared to older groups.”

The other patterns of anti-feminist identification, according to the authors, are “more the mirror image of feminist identification” with “Republicans being more likely to identify as anti-feminists compared to Democrats, and stay-at-home parents/homemakers, those who identify as born again, and those who attend church frequently being more anti-feminist.”

To provoke further discussion, I will end with the argumentative economist Tyler Cowen , of George Mason University and “ Marginal Revolution .” In December 2019, Cowen wrote a column for Bloomberg, “ Women Dominated the Decade ,” subtitled “The 2010s were pretty thrilling if you liked music, books, TV or movies by or about women.”

Cowen, who acknowledges describing “feminization in not entirely glowing terms ” — indeed one would have to say hostile terms — is also, in other contexts, unequivocally enthusiastic about “what I see as the No. 1. trend of the decade: the increasing influence of women.”

“I had the best of both worlds,” Cowen writes, “namely to grow up in the ‘tougher’ society, but live most of my life in the more feminized society.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here's our email: [email protected] .

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram .

Because of an editing error, an earlier version of this article misstated the percentage of women in a Knight Foundation survey who said the First Amendment should not be used to protect hate speech. It was 71 percent, not 7 percent.

How we handle corrections

Thomas B. Edsall has been a contributor to the Times Opinion section since 2011. His column on strategic and demographic trends in American politics appears every Wednesday. He previously covered politics for The Washington Post. @ edsall

Essays on Gender Gaps in STEM

This dissertation explores the issue of under-representation of women in STEM fields in high school and the early years of college. One of the major contributors to the persisting gender earnings gap is male-domination in the STEM workforce. Women are under-represented in STEM occupations since they are less likely than men to take advanced STEM courses in high school and to choose STEM majors in college. While the gender STEM gap does not exist at early ages according to most studies, it has been shown that girls start to lag behind boys in Math tests after middle school.

In Chapter 1, I investigate the STEM gender gap in the context of teacher-student gender matching. Using a fixed-effects regression model, and Chilean administrative education data on SIMCE and PSU exams and college application, I explore whether high school girls perform better in Language and Math when they have female teachers, and whether a female Math teacher impacts girls’ preference towards STEM programs when enrolling in college. I find that female teachers improve girls’ overall performance in high school Math exams for all school types, and college entrance exam Math scores for public school girls. However, they negatively affect girls’ probability of choosing STEM majors when enrolling in college. They negatively affect boys’ high school and college entrance exam Language performance and private school boys’ college entrance exam Math performance, but positively affect boys’ college STEM preference. The presence of female Math teachers in high school has negative effects on both boys’ and girls’ college entrance exam Science scores. There is significant heterogeneity in these effects between public, voucher and private schools. The negative preference effect is significant only for

high-performing girls.

Chapter 2 uses restricted NCES data (HSLS:2009 and ELS:2002) and difference-in-difference methodology to explore whether the $4.35 billion federal Race to the Top (RTT) program of 2009 had impacts on overall educational and enrollment outcomes, and gender gaps in these outcomes for high school students in the US. Besides the major objective of making students better prepared for college and future careers, a significant aspect of the RTT program was its emphasis on reducing barriers to women’s entry and success in STEM fields in higher education and the STEM workforce. I find that the program was not successful in fulfilling the major objectives of improving students’ educational outcomes, reducing achievement gaps or improving women’s representation and performance in STEM fields. It prompted students to take fewer and easier courses in high school and increased gender gaps in 12th grade GPA and SAT Math score. While there was a modest reduction in the gender gap in first year college GPA, there were neither any improvements in boys’ or girls’ college STEM credits and grades, nor

any reduction in gender gaps in these outcomes.

In Chapter 3, I use the same restricted NCES data as in Chapter 2, data on state policy obtained from Howell and Magazinnik (2017) and difference-in-difference methodology to explore whether states’ adoption of “college and career ready” common K-12 standards affected the overall educational and enrollment outcomes of high school students in the US and gender gaps in these outcomes. I use the 2009 Race to the Top (RTT) program as a source of exogenous variation, since one of the major policies promoted by the program was the adoption of higher K-12 standards across the US. I find that the tougher standards led to students taking relatively more non-STEM oriented, and thus arguably “easier” courses and increased gender gaps in STEM coursetaking.