The representation of feedback literature in classroom observation frameworks: an exploratory study

- Open access

- Published: 10 December 2022

- Volume 35 , pages 67–104, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Merle Ruelmann 1 , 2 ,

- Charalambos Y. Charalambous ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0051-6926 3 &

- Anna-Katharina Praetorius ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7581-367X 1

3856 Accesses

2 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Feedback is considered of great relevance for supporting student learning. It is therefore the focus of a significant body of theoretical work and is included in many observation frameworks for measuring teaching quality. However, little is currently known about the extent to which the theoretical and empirical knowledge of feedback from the literature is represented in operationalizations of feedback in observation frameworks. In this exploratory study, we first reviewed the literature and identified nine quality criteria for effective feedback. Using content analysis, we then explored the extent to which 12 widely used observation frameworks for teaching quality reflect these criteria and the similarities and differences in their approaches to capturing feedback quality. Only ten of the 12 frameworks measured feedback. Nine frameworks addressed feedback directly, while one framework only captured feedback indirectly. All frameworks differed in the number of feedback quality criteria they captured, the aspects they focused on for each one, and the detail in which they described them. One criterion (Feed Up) was not captured by any framework. The results show that more clarity is needed about which facets of feedback are integrated into frameworks and why. The study also highlights the importance of finding ways to complement observation frameworks with other measures so that feedback quality is captured in a more comprehensive fashion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Bridging the gap between observation protocols and formative feedback

Promoting Teaching Quality Through Classroom Observation and Feedback: Design of a Program in the German State of Baden-Württemberg

Introduction: rethinking assessment and feedback.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Over the past two decades, there has been a rapid increase in the production of classroom observation frameworks for the assessment of teaching quality. Praetorius and Charalambous ( 2018 ) compared and contrasted 12 well-known frameworks and the ways in which they captured teaching quality in the same three videotaped lessons. Although their analysis found some areas of overlap between the frameworks, it also surfaced significant discrepancies between them, even when the same terms were used to capture specific teaching aspects. In particular, feedback given to students has been evaluated differently in several frameworks that incorporated it as an aspect of teaching quality. This shows that feedback is understood differently across frameworks, highlighting a more significant issue: How well do these frameworks capture core facets of feedback quality, and more importantly, how well do they reflect the existing literature on the topic? At present, little is known about whether, and if so how, the operationalization of feedback by the various observation frameworks relates to the existing literature on feedback. However, this could be a promising approach for facilitating a more informed discussion on the content validity of feedback quality capture. A literature-based comparison of the ways feedback is operationalized may provide insights into how the feedback aspect of teaching quality in classroom observation frameworks can be developed and refined.

In this study, we therefore take a top-down approach to comparing classroom observation frameworks Footnote 1 as a complement to the findings of previous research that used a bottom-up approach (Bell et al., 2019 ; Dobbelaer, 2019 ; Klette & Blikstad-Balas, 2018 ; Praetorius & Charalambous, 2018 ; Schlesinger & Jentsch, 2016 ). The aim is to investigate whether 12 well-known observation frameworks, which already have been shown to differ in the ways they conceptualize, operationalize, and measure teaching quality (Praetorius & Charalambous, 2018 ), reflect the literature on feedback.

The article has three parts. The first part provides a brief overview of feedback theory and research. The criteria Footnote 2 for evaluating feedback quality, derived from the literature, are also presented. The second part of the paper is an empirical analysis of how these criteria are reflected in the 12 observation frameworks. In the final part, we discuss the findings and their implications for the measurement of feedback using classroom observation frameworks designed to capture teaching quality.

2 Feedback literature

2.1 feedback theory and research.

Each student has a personal educational history, individual learning needs, and a unique way of engaging with learning environments and lessons. Feedback is important because it comprises a response to these individual learning processes and offers opportunities for improvement (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ; Shute, 2008 ). Effective feedback helps learners to close the gap between their current learning state and their learning goals (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ; Sadler, 1989 ). Therefore, feedback is considered key to enhancing student learning, and an important aspect of teaching quality (Black & Wiliam, 1998 ; Chappuis & Stiggins, 2017 ; Hattie, 2009 ; Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ; Sadler, 1989 ).

The feedback message itself has often been defined as “information” (e.g., Kluger & DeNisi, 1996 , p. 255; Hattie & Timperley, 2007 , p. 81; Shute, 2008 , p. 154). However, whether this information (or feedback message) actually contributes to learning progress depends on a complex interaction of many factors. The two most important determinants of the impact of feedback are how it is given ( provision ) and how it is used ( use ) (Ruiz-Primo, 2011 ; Ruiz-Primo & Furtak, 2006 , 2007 ; Strijbos & Müller, 2014 ): Teachers or other agents (e.g., students, computers) can provide information on student learning or performance (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ). However, students must actively receive and process (i.e., use ) the information conveyed in accordance with their individual prerequisites (e.g., current knowledge) for it to have an effect (Ilgen et al., 1979 ; Butler & Winnie, 1995 ; Nicol & Macfarlane‐Dick, 2006 ). Moreover, the information conveyed and received is linked to situational factors and the learning context, which can also influence the impact of feedback (Narciss, 2008 ). Therefore, feedback can broadly be viewed as a process or even multiple processes of learners’ making sense of information provided to them within a complex system (Henderson et al., 2019a ). Although there is broad consensus on the importance of feedback for supporting learning, there are many definitions and theoretical models of feedback, and empirical research on different aspects of feedback exists (Henderson et al., 2019b ).

Because feedback is important for student learning and is also a complex construct, the literature on it is extensive and quite diverse. For example, there are many theories which aim to explain the feedback process, but they have different perspectives: In their meta-analysis and feedback intervention theory, Kluger and DeNisi ( 1996 ) focus on the varying effects of feedback provided by analyzing how it shifts learners’ attention (e.g., to the task or to the self). On the other hand, in their conceptual framework for feedback in computer-based learning environments, Narciss and Huth ( 2004 ), highlight the role of task and error analysis and learner characteristics. From yet another angle, in their theoretical synthesis, Butler and Winnie ( 1995 ) consider the feedback process in the light of self-regulated learning. In addition, there are numerous other theoretical models (e.g., Ditton et al., 2014 ; Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ; Heritage, 2010 ; Nicol & Macfarlane‐Dick, 2006 ), literature reviews (e.g., Black & Wiliam, 1998 ; Hattie et al., 2017 ; Mory, 2004 ; Shute, 2008 ), and meta-analyses (e.g., Bangert-Drowns et al., 1991 ; Hattie, 2009 ; Kluger & DeNisi, 1996 ; Wisniewski et al., 2020 ) on feedback.

2.2 Summary of criteria for an effective feedback process

In the present exploratory study, we aim to compare observation frameworks top-down starting from the feedback literature. As highlighted in the previous section, this is a challenging task. On the one hand, the literature on feedback is quite diverse and theoretical models describe important aspects of the feedback process from different angles. Therefore, a comparison of observation frameworks should incorporate more than one article or feedback model. On the other hand, due to the importance of feedback for learning and the great interest in it, there are thousands of publications on the topic. Footnote 3 Covering the full breadth of publications on feedback would require a stand-alone literature review, which is not possible within the scope of this article. Therefore, we decided to limit our search in this initial exploration to the most frequently cited articles on the subject. Due to their high visibility, it can be assumed that the central statements of these articles were of great importance for research discourse on the impact of feedback on learning. Thus, they can be seen as milestones that have shed light on a number of key factors for a successful feedback process. The focus on concrete key criteria that can be derived from frequently cited articles can serve as a first approximation to inform classroom observation frameworks. Moreover, if the examined observation frameworks do not reflect these most central criteria of feedback quality, their coverage of feedback emerging from a broader literature review would be even more limited.

The following is a summary of the key criteria for effective feedback identified by our literature search (for more detailed information about the procedure for the literature search and how the criteria were derived from the selected articles, see Appendix 1 ). We present nine criteria that are relevant to the impact of feedback and sumarize their sub-criteria. As the two most important determinants in the feedback process are the provision of feedback (e.g., by teachers or peers) and the use of feedback by learners, the quality criteria are grouped into Feedback Provision and Feedback Use . This distinction is also consistent with the assumptions of the opportunity-use model, on which several teaching quality frameworks such as TBD (Three Basic Dimensions, see Praetorius et al., 2018 ) are based. According to the opportunity-use model, the effectiveness of learning depends on the quality of a learning opportunity (i.e., feedback provision) and how it is used by students, (i.e., feedback use) (Charalambous & Praetorius, 2020 ; Vieluf et al., 2020 ). Because feedback can also be co-constructed, some criteria can be seen as part of both feedback provision (or opportunities) and feedback use; these are listed in a separate section called Connecting Provision and Use .

2.2.1 Feedback provision

Feedback provision relates to the way feedback messages are constructed and conveyed in the situation in which feedback is given (e.g., task, learning context). The following six criteria for feedback provision were identified:

Information

Since feedback messages can be viewed as information provided to the student, it is self-evident that the nature of the information is itself important. Meta-analyses have compared different types of feedback messages Footnote 4 on the basis of the information they provide. Their findings revealed that feedback enhances learning when it conveys specific, content-related information (Bangert-Drowns et al., 1991 ; Kluger & DeNisi, 1996 ; Shute, 2008 ). Vague, general, or personal feedback (e.g., grades, praise, or pointing out personal attributes such as “You are very good at math!”) contains too little information for learners to act on. In the worst case, such feedback can shift attention away from the task or learning content to the self-level (e.g., triggering actions to protect one’s self-esteem) (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ; Kluger & DeNisi, 1996 ). Too much information, on the other hand, can be overwhelming for learners, dilute the message, or cause cognitive overload (Shute, 2008 ). Thus, information should be conveyed as simply as possible, in manageable units, and should prioritize areas for improvement (Nicol & Macfarlane‐Dick, 2006 ; Shute, 2008 ).

To enhance learning, feedback needs to provide information about the gap between the current state of learning and the target state (Black & Wiliam, 1998 , 2009 ; Sadler, 1989 ). Feed Up , and the next two criteria, Feed Back and Feed Forward , all relate in different ways to this gap.

Feed Up relates to learning goals. Ensuring learning goals are clear (looking up: Where am I going?) is important when tackling the gap between what is already known and the target state. Students are more likely to engage when they understand learning goals, commit to them, and believe in their own success (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ; Kluger & DeNisi, 1996 ). An important requirement for this is that learning goals be well-defined, specific, and challenging (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ; Kluger & DeNisi, 1996 ; Shute, 2008 ). Consequently, goal-related feedback is useful when it provides criteria for success and examples that operationalize goals and point out specific steps to achieve them (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ; Nicol & Macfarlane‐Dick, 2006 ). In relation to task work this can also mean making task requirements clear (Shute, 2008 ). A large body of research has demonstrated that relating current performance to learning goals or success criteria and keeping students informed about how they are progressing is an important factor for effective feedback (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ; Kluger & DeNisi, 1996 ; Shute, 2008 ). Footnote 5 Feedback can also support continuous learning by providing challenging new goals when previous ones have been achieved (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ).

Addressing the gap between current learning and future goals requires the evaluation of learning that has already taken place (looking back: How have I done so far?). This evaluation can be on multiple levels. As noted before (see Information ), personal feedback (self-level) is not effective. The evaluation of learning should target task performance (task-level), by, for example, verifying the correctness of results, or the task process (process-level), by evaluating strategies that students use (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ; Kluger & DeNisi, 1996 ). While task-level feedback increases surface knowledge about the task, research indicates that feedback at the process-level enhances deeper learning (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ). Another dimension of evaluation is its point of reference. Evidence shows that feedback is beneficial when it points out progress in relation to prior performance (self-reference) while avoiding comparisons with other students (norm-reference) (Shute, 2008 ).

Feed Forward

Evidence suggests that feedback fosters learning if it supplements the assessment of current learning ( Feed Back ) with further information on how to achieve learning goals (looking forward: How do I make progress?) (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ; Nicol & Macfarlane‐Dick, 2006 ). Feedback that extends student thinking or points out ways to improve instead of simply judging whether students’ results are correct enhances achievement (Butler & Winne, 1995 ; Shute, 2008 ). Better understanding of concepts, task requirements, or strategies can be supported by conveying additional information (e.g., enriching, rephrasing, extending student thinking) or offering corrective information (e.g., pointing out errors, misconceptions; clarifying wrong assumptions) (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ; Nicol & Macfarlane‐Dick, 2006 ; Shute, 2008 ).

Motivation and Self-regulation

Feedback is beneficial when it fosters positive motivational beliefs and self-regulation skills in students because this enhances their ability to use learning opportunities and the information given through feedback (Nicol & Macfarlane‐Dick, 2006 ). If feedback is too critical or controlling, or poses a threat to students’ self-esteem (e.g., embarrassing or discouraging feedback), it undermines motivation and achievement (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ; Kluger & DeNisi, 1996 ; Shute, 2008 ).

Feedback can also directly convey reassuring or motivating information. Affirming effort and persistence, and focusing on mastery and growth, can promote positive attributions of success (e.g., “I am successful because I work hard.”) as well as positive self-belief (e.g., self-esteem and self-efficacy). Feedback should therefore foster students’ confidence and their control of the learning process (Butler & Winne, 1995 ; Nicol & Macfarlane‐Dick, 2006 ). Inviting students to self-correct and detect their own errors (self-regulation level) also encourages students to take greater responsibility for their learning (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ).

Research results on the timing of feedback (immediate vs. delayed) are inconsistent, in part because they are dependent on learners’ preconditions (see Adaptation ). Nevertheless, some criteria are applicable to all students. Findings show that feedback is more effective when information is provided after students attempt a solution on their own. They need to be cognitively engaged in a task before receiving feedback (Shute, 2008 ). But students should also have the opportunity to alter their work in response to the feedback. Ideally, therefore, feedback should be given formatively when work is still in progress. The information can then be used for improvement and does not serve as a summative evaluation after the work has already been completed (Nicol & Macfarlane‐Dick, 2006 ). Even though feedback is beneficial when provided during work, students should not be interrupted by it (Shute, 2008 ).

Adaptation can be viewed as a criterion that affects all of the other criteria related to feedback provision. A large body of research has shown that feedback can have differential effects depending on student prerequisites (Butler & Winnie, 1995 ). Evidence suggests that learners with low abilities benefit from immediate and more directive or corrective feedback (e.g., through partial solutions or direct instructions) that includes elaboration or scaffolding to further the learning process, especially when completing unfamiliar tasks. Learners with high abilities benefit more from more delayed verification feedback that is provided in a non-directive, facilitative manner (e.g., through hints, cues, prompts) (Shute, 2008 ). Moreover, a learner’s perception of the difficulty of a task is relevant. If a learner believes a task is difficult, more immediate feedback is helpful, while subjectively easy tasks require delayed feedback (Shute, 2008 ; Kluger & DeNisi, 1996 ).

Students’ motivational characteristics and beliefs may also influence the perception and processing of feedback (Butler & Winne, 1995 ; Nicol & Macfarlane‐Dick, 2006 ; Shute, 2008 ). Even though there is little research into how to adapt feedback to motivational prerequisites, some evidence suggests that more immediate feedback is beneficial for learners with low self-efficacy and more goal-directed feedback for students with low learning goal orientation or high-performance orientation (Shute, 2008 ).

2.2.2 Feedback use

While the manner in which feedback is provided is important, its effectiveness also depends substantially on how the information is received by students. The following criterion describes the factors that affect how feedback is processed by students.

Information Processing and Self-regulation

In order for feedback to have a positive effect, students must be willing to use the information provided rather than rejecting it (Kluger & DeNisi, 1996 ; Shute, 2008 ). Students then have to actively process the feedback and internalize it (Nicol & Macfarlane‐Dick, 2006 ). Butler and Winne ( 1995 ) describe the active role of learners in processing feedback: “Feedback is information with which a learner can confirm, add to, overwrite, tune, or restructure” (Butler & Winne, 1995 , p. 275). The information provided promotes learning if it is used to improve the understanding of tasks, concepts, and approaches (task- and process-level) (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ), or to enhance motivation and self-regulation (self-regulation level) (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ; Nicol & Macfarlane‐Dick, 2006 ). Students can also influence the frequency of feedback provided to them by actively seeking it. Students who know when and how to seek feedback from others are more independent learners and have better self-regulation strategies at their disposal (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ). Part of increasing self-regulation is also assessing one’s own work through self-assessment.

2.2.3 Connecting feedback provision and use

We identified one criterion that links the provision and use of feedback.

Co-construction

Theoretical models based on social-constructivist conceptions of learning emphasize that the provision and use of feedback are about communication rather than a transmission of information. The idea is that feedback should be understood as a dialogue during which students get the opportunity to discuss the feedback and negotiate its meaning with others (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ; Nicol & Macfarlane‐Dick, 2006 ). Besides extended interactions with the teacher, peers are also an important source for the co-construction and discussion of feedback. Peer dialogue can motivate and stimulate the construction of knowledge. Moreover, peer assessment can help with understanding and using criteria for success. By assessing the work of peers, students can learn to apply success criteria to their own work (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006 ).

2.3 The present study

This study aims to explore how well classroom observation frameworks for capturing teaching quality reflect the quality criteria for effective feedback found in the feedback literature. The previous sections summarized important publications on the topic of feedback and showed that even though the feedback process is complex (Hattie & Timperley, 2007 ; Henderson et al., 2019b ; Narciss, 2008 ), some key criteria for high-quality feedback practice can be identified. In the following, we apply a top-down approach to the analysis of observation-based frameworks, starting with the nine quality criteria identified (see Sect. 2.2 ), and explore the following research questions:

RQ 1: Which quality criteria for an effective feedback process are represented in well-known classroom observation frameworks?

RQ 2: What are the similarities and differences in how the frameworks capture these quality criteria?

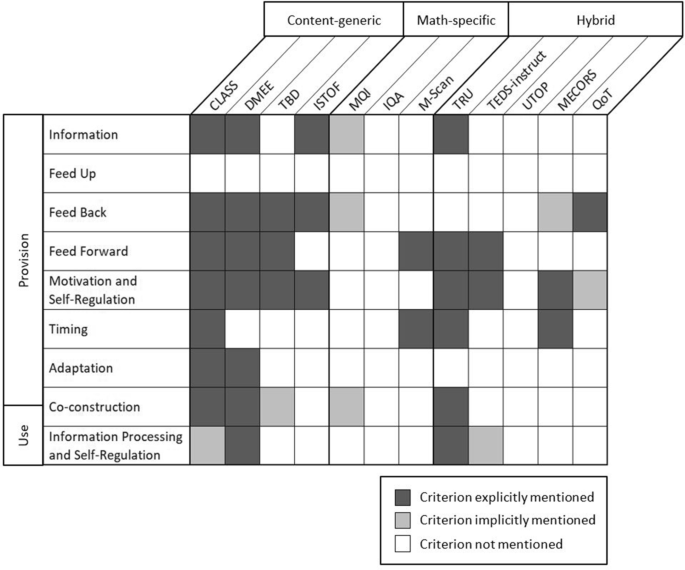

We chose to use the 12 frameworks discussed by Praetorius and Charalambous ( 2018 ) in their synthesis of classroom observation frameworks because they are well-known instruments for studying teaching quality (Charalambous & Praetorius, 2018 ). The sample includes a range of different types of frameworks (see Table 1 ): four content-generic (CLASS, see Pianta & Hamre, 2009 ; DMEE, see Kyriakides et al., 2018 ; TBD, see Praetorius et al., 2018 ; ISTOF, see Muijs et al., 2018 ), three mathematics-specific (MQI, see Charalambous & Litke, 2018 ; IQA, see Boston & Candela, 2018 ; M-Scan, see Walkowiak et al., 2018 ), and five hybrid frameworks (TRU, see Schoenfeld, 2018 ; TEDS-Instruct, see Schlesinger et al., 2018 ; UTOP see Walkington & Marder, 2018 ; and the combination Footnote 6 of MECORS and QoT, see Schaffer et al., 1998 and van de Grift, 2007 ). This allows for a comparison across the different types as well as within each individual type (Charalambous & Praetorius, 2018 ).

3.2 Procedure for content analysis

In order to answer the research questions, a content analysis of the observation frameworks was conducted using MAXQDA 2020 qualitative analytics software. The authors had access to all of the frameworks and corresponding instruments of the original Praetorius and Charalambous ( 2018 ) sample: For each of the 12 frameworks, we used key sources Footnote 7 where the framework and its associated instrument were described. For example, for CLASS we used the descriptions and rubrics for measuring the teaching quality domains in the user guide (Pianta et al., 2012 , pp. 21–110), for DMEE we analyzed the description of the eight effectiveness factors used for teaching quality measurement (Creemers & Kyriakides, 2008 , pp. 103–119), and for UTOP, we analyzed the description of the framework and instrument provided on the webpage (UTeach Institute, 2022 ).

The content analysis of these sources was conducted in a series of steps. First, we identified the sections of each framework that related to measuring feedback. To do this, we scanned each document for the term “feedback” using the search function in MAXQDA. Each continuous part (e.g., a paragraph or table) was marked as a coding unit (coded with the neutral code “coding unit”). For example, in CLASS, the rubric “teacher feedback” (table and annotations) was marked as one coding unit. In addition, there are detailed level descriptions in CLASS that are several pages long. Each paragraph was marked as a separate coding unit in these.

Second, we compared the coding units to the nine quality criteria for an effective feedback process. To perform the content coding in this second step, we developed and used a detailed coding manual (see Table 2 ), informed by our review of the literature (see Sect. 2.2 ). We operationalized the nine quality criteria as content codes by formulating the main idea of each criterion in one sentence and listing the related sub-criteria that describe it in more detail as indicators (see Table 2 , column 2, “Indicators”). A coding unit was coded with a content code when any of the indicators applied. If none of the content codes were applicable for a coding unit, it was coded as “else.”

Before applying the coding manual to the study sample, we tested it on seven other teaching quality observation frameworks, mainly government instruments for school evaluations (e.g., “How good is our school?”, see Education Scotland, 2015 ) and a few instruments from research projects (e.g., TALIS-Video study observation tool, see Bell et al., 2022 ). Footnote 8 During the course of this process, the coding manual was refined by adding coding rules for each content code and wording examples from the test frameworks (see Table 2 , column 3, “Coding Rules,” and column 4, “Wording Examples”). The additional coding rules and examples served to make the content codes more specific. In particular, coding rules evolved as a result of disagreements between coders about the application of the indicators for content codes during the analysis of the test frameworks. These facilitated content coding in critical cases. For example, the coding rules for Feed Forward (Table 2 , line 4) specified in more detail the different ways in which Feed Forward could be represented in a framework, such as through rubrics or items on “using the feedback information itself (hints, prompts that extend the thought process) or discussing next steps with the student”. Giving specific examples of phrases used also provided further, more concrete, guidance for deciding whether an aspect was covered by a framework (e.g., “extend thinking,” “expansion”).

Third, to identify those parts of the sample of observation frameworks that indirectly refer to feedback, we manually searched each document. During this step, we once again identified and marked separate coding units for implicit references to feedback, thus ensuring that we did not exclude any parts of the frameworks that were clearly referring to feedback without explicitly mentioning it (e.g., from TBD: “The teacher does not evaluate students’ answers directly, but asks other students to do it”). All cases were discussed among the authors to reach a consensus on which were included. We excluded those implicit references in the frameworks that could apply to feedback under certain conditions but did not focus on it. For example, the TBD statement “The interactions between teacher and students support conceptual change and conceptual expansion” was not included because interactions could include feedback but do not necessarily have to. Fourth, the implicit coding units were coded with the content codes in the same manner as the explicit coding units had been.

All 12 frameworks were independently coded by two coders, the first author and a trained student assistant. Each coding unit could be coded with any number of the nine content codes as it was likely that larger coding units could include multiple aspects of feedback quality (e.g., tables with many indicators). The interrater reliability between the two coders was assessed using Cohen’s kappa at the coding unit level. The interrater reliability was high (cf. Landis & Koch, 1977 ), both for the coding units that explicitly mentioned feedback (kappa = 0.83), and those which made implicit references (kappa = 0.83). The coders resolved any disagreements that emerged through discussion and reached a consensus.

3.3 Additional analyses of measurement approaches to feedback

Based on our intention to enable an informed discussion about how to capture feedback in a content-valid manner, we decided to conduct two additional in-depth analyses of the 12 observation frameworks. First, we analyzed where feedback quality criteria are located within the frameworks to identify how they integrate feedback into their conceptualizations of teaching quality. Second, previous research has shown that measurement decisions (e.g., how lessons are broken down into observational units and which factors, such as quality or quantity, are used for the assessment of feedback) can influence the measurement of feedback (Luoto et al., 2022 ). Therefore, we decided to investigate this aspect as well and compare the procedures for measuring feedback across frameworks.

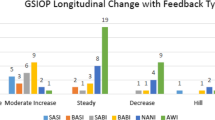

4.1 Differences in how categories of frameworks address feedback

The results of the content coding (see Fig. 1 ) show how the 12 classroom observation frameworks map the nine criteria of high-quality feedback (RQ1) as well as the similarities and differences between the frameworks (RQ2). Looking at the frameworks holistically (columns) reveals that the feedback quality criteria are not consistently considered by the frameworks. All of the content-generic and most of the hybrid frameworks (except for UTOP) explicitly address feedback, which was not the case for most of the mathematics-specific frameworks. Two content-generic frameworks, CLASS and DMEE, capture feedback in the most comprehensive manner, addressing seven and eight of the nine quality criteria, respectively. However, UTOP (hybrid) and IQA (mathematics-specific) do not consider feedback at all when measuring teaching quality.

Coverage of the nine quality criteria by observation frameworks

4.2 Differences in coverage of feedback quality criteria by frameworks

A look at the rows in Fig. 1 reveals differences in the extent to which each individual criterion of high-quality feedback is reflected in each framework. No criterion is captured by all of the frameworks. Fostering student motivation and self-regulation through feedback ( Motivation and Self-regulation ) is the most frequently addressed criterion in the frameworks. Many frameworks, especially the content-generic ones, also consider whether the feedback evaluated the current learning state ( Feed Back ) and how progress could be made ( Feed Forward ). The level of information provided through feedback ( Information ) and the timing of feedback ( Timing ) is addressed by less than half of the frameworks. Aspects such as the feedback being adaptive ( Adaptation ), negotiated with students ( Co-construction ), and in particular, the students’ use of feedback ( Information Processing and Self-regulation ), feature in only a couple of frameworks. The extent to which feedback relates to learning goals and criteria of success ( Feed Up ) is not covered by any framework.

4.3 Detail with which frameworks capture feedback quality criteria

Frameworks also operationalize feedback quality criteria differently and capture them in varying degrees of detail. We describe differences in the depth of the operationalizations across frameworks in descending order of the frequency with which the criteria were picked up by the frameworks.

When assessing Motivation and Self-regulation , the TBD, ISTOF, TEDS, MECORS, and QoT frameworks mainly focus on whether the feedback is offered in a positive manner (e.g., TBD, “Feedback is formulated benevolently, even in response to errors.”; MECORS, “The teacher gives positive academic feedback.”). For this criterion, TRU assesses the promotion of self-regulation through feedback (“Teachers […] prompt students to make active use of feedback to further their learning.”). By comparison, CLASS goes into more detail, measuring whether feedback recognizes students’ effort and persistence, whether it relates to learning rather than performance, and whether it supports self-assessment (e.g., regarding effort and persistence, “The teacher and other students often offer encouragement of students’ efforts that increases involvement and persistence.”).

When capturing Feed Back , TBD, ISTOF, MECORS, and QoT look for feedback assessing the correctness of an answer (e.g., ISTOF, “The teacher makes explicitly clear why an answer is correct or not.”), whereas CLASS and DMEE also capture reasons why mistakes occur (e.g., DMEE, “Following incorrect answers, teachers should […] show why the answer is incorrect.”). QoT focuses on whether students understand the lesson materials and how they arrive at their answers (e.g., “The teacher checks whether pupils have understood the lesson materials.”).

With regards to Feed Forward , the references unanimously stress the importance of feedback that advances students’ thinking (e.g., TBD, “The teacher’s feedback shows students […] how they can improve.”; CLASS, “Feedback expands and extends learning and understanding.”). Most frameworks, however, are vague in their operationalization of this criterion, not specifying directly observable indicators (e.g., TEDS-instruct: “The teacher’s feedback is forward-looking”).

The way Information is presented during feedback is again differently assessed by each framework. DMEE emphasizes that feedback should focus on content and avoid personal criticism (e.g., “Teachers should begin by indicating that the response is not correct but avoid personal criticism.”), while ISTOF and TRU focus on feedback being detailed and not too vague (e.g., ISTOF, “The teacher gives explicit, detailed and constructive feedback.”). CLASS again goes into more detail, covering both aspects.

A closer look into the operationalization of feedback Timing revealed that the coverage of this criterion by the frameworks mostly does not match the aspects of quality derived from the literature. In some frameworks (e.g., CLASS, M-Scan, TRU), timing is partially operationalized as frequency and used as a descriptor of other quality criteria in the sense of “the more the better” (e.g., feedback should be given “often,” “consistently,” “frequently,” “in multiple instances”). Despite the conflicting results for immediate and delayed feedback, MECORS included “immediate academic feedback” as a descriptor for feedback quality.

Adaptation is considered by two frameworks, CLASS and DMEE, but they differ in the level of detail in their assessment. While DMEE includes detailed information about how feedback should be aligned with different learners’ needs (e.g., “Effective teachers are expected to provide encouragement for their efforts more frequently to low-SES and low-achieving students and to praise their success.”), CLASS refers to Adaptation in broader terms (“At the high end, the teacher or peer consistently goes beyond a global ‘Good job!’ and frequently gives specific feedback that is individualized to specific students or contexts of learning.”).

The frameworks also vary in how they measure Co-construction . While DMEE assesses whether the provision of feedback is embedded in ongoing conversations between the teacher and students (e.g., through extensions and hints given by the teacher), TRU also evaluates whether students give feedback to each other (peer assessment). CLASS, once again being finer grained, takes both of these aspects into account (e.g., “There are frequent feedback loops between the teacher and students or among students, which lead students to obtain a deeper understanding of material and concepts.”).

There are also differences in what frameworks emphasize regarding Information Processing and Self-regulation . TRU looks at whether students give themselves feedback through self-assessment (e.g., “Each student consistently reflects on their work and the work of peers.”) while DMEE focuses on whether students use feedback provided by others (e.g., “We also examine […] the way students use the teacher feedback.”).

The criteria Feed Back , Motivation and Self-regulation , Co-construction , and Information Processing and Self-regulation were implicitly mentioned in some frameworks which addressed other criteria explicitly.

4.4 Additional analyses: approaches to feedback measurement in frameworks

To analyze the differences between the frameworks (RQ2) in greater detail, we also compared how different frameworks approached the measurement of feedback.

4.4.1 Mapping feedback within the structure of frameworks

Consistent with the results of bottom-up studies (Praetorius & Charalambous, 2018 ), we found that the frameworks differ in the number of main and sub-categories and their overall conceptualization of teaching quality. Analyzing where the measurement of feedback is located within the structure of each framework revealed interesting differences between them (for details, see Appendix 4 ): CLASS, TBD, ISTOF, TEDS, and QoT have an extra sub-category within their framework just for measuring feedback. Other frameworks, M-Scan, TRU, and MECORS, treat feedback measurement as part of a larger category, assessing it alongside other aspects of teaching quality (e.g., formative assessment or questioning skills). Uniquely, DMEE splits feedback measurement across different teaching quality categories (e.g., questioning techniques and assessment).

Different frameworks also assign feedback to different main categories of teaching quality. Some frameworks consider feedback as part of cognitive activation or instructional support (i.e., CLASS, M-Scan, and QoT), others classify it as (formative) assessment (i.e., DMEE, ISTOF, TRU), still others assign feedback to student support (i.e., TBD and TEDs-Instruct), and in some frameworks feedback is part of a teacher’s ability to pose questions (i.e., DMEE and MECORS). Indirect references to feedback are found in even more different categories and sub-categories of frameworks such as classroom climate, metacognition, and subject-specific categories of teaching quality measurement (e.g., in MQI in the category “Working with students and mathematics”; in TEDs-Instruct in the category “Subject-related quality”).

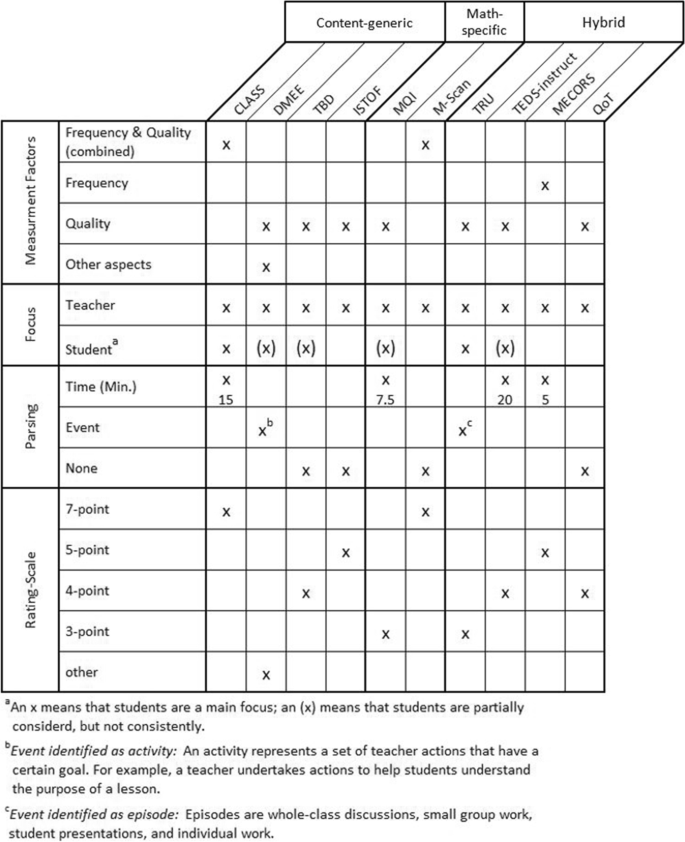

4.4.2 Comparing measurement decisions across frameworks

We found that how feedback is measured is determined by the general measurement methods and procedures within each observation framework. Consistent with Praetorius and Charalambous ( 2018 ), our results reveal differences in these measurement decisions across frameworks (see Fig. 2 ).

Measurement approaches to feedback by observation frameworks

Measurement factors

The analyzed frameworks assess teaching quality and feedback using different sets of factors. For example, some frameworks exclusively assess the quality of feedback criteria (e.g., ISTOF), others only assess their quantity (e.g., MECORS), and some use both quantity and quality for their evaluation of feedback criteria (e.g., CLASS) or measure the feedback criteria using several different factors (e.g., see the five dimensions of DMEE).

Most frameworks focus on teacher behaviors, but some also include student behaviors (e.g., CLASS, TRU).

Some frameworks divide lessons into smaller units of time (e.g., CLASS, MQI, TEDs, MECORS, QoT). For example, CLASS divides lessons into 15–20-min units, while MQI divides lessons into 7.5-min units. Other frameworks divide lessons into meaningful phases or instruction events (e.g., DMEE, TRU). For example, TRU’s analyses are based on episodes like whole class discussions and small group work. Some frameworks do not specify any segments (e.g., TBD, ISTOF, M-Scan).

Rating scales

The observation frameworks studied use various rating scales to evaluate the measurement factors, ranging from 3- to 7-point measures.

5 Discussion

5.1 summary of the results for how observation frameworks cover feedback quality criteria.

The purpose of this study was to investigate how literature on feedback is reflected in classroom observation frameworks for teaching quality, and to initiate a discussion about the validity of these approaches.

Overall, it was found that the 12 classroom observation frameworks in the study sample capture and weight feedback differently. Each framework covers a different selection of the nine quality criteria derived from literature. There is no overlap of criteria considered between some frameworks (e.g., QoT measures feedback through Feed Back and Motivation and Self-regulation , whereas M-Scan addresses Feed Forward and Timing ), and others do not address feedback at all when measuring teaching quality (i.e., IQA, UTOP). Only two frameworks, CLASS and DMEE, address multiple quality criteria (see Sect. 4.2 ). Even when frameworks capture the same criterion, they focus on different facets of it (e.g., for Feed Back some frameworks assess the correctness of students’ answers while others focus on how students arrive at their answers or why mistakes are made) (see Sect. 4.3 ). Moreover, we found differences in the ways in which observation frameworks integrate feedback into their conceptualization of teaching quality and in the underlying decisions made about how to approach feedback measurement (see Sect. 4.4 ). These findings strongly indicate that the literature on feedback is not equally reflected in the 12 observation frameworks studied meaning that results based on these observation frameworks are not directly comparable.

What can we learn from these findings? In the following, we address three core issues that can inform a discussion about valid measurement of feedback using observation frameworks: First, we discuss potential theoretical reasons for differences in capturing feedback as part of teaching quality. Second, we address how well the general measurement decisions of frameworks are appropriate for capturing feedback quality criteria. Third, we reflect on the extent to which observations are suitable for measuring feedback.

5.2 Feedback measurement as part of teaching quality measurement

The top-down analysis presented above shows that the feedback measurement aspects of the frameworks relate to the literature on feedback to varying degrees. Interestingly, none of the nine high-quality criteria is covered by all of the observation frameworks. There is also no framework that captures all nine quality criteria. This raises the question of whether it is possible or necessary for a content-valid measurement to include all identified feedback quality criteria. Obviously, the observation frameworks analyzed capture not only feedback, but other dimensions of teaching quality too. To do this in a useful way, they need to be parsimonious (Schoenfeld et al., 2018 ). Therefore, there may be theoretical reasons behind the prioritization of some criteria over others by a framework.

Each observation framework reflects a particular view of teaching and learning based on theoretical foundations and value decisions (Praetorius & Charalambous, 2018 ; Schoenfeld et al., 2018 ). Thus, as Schoenfeld and colleagues ( 2018 ) argue, “Any framework for assessing instruction embodies a set of values regarding ‘what counts’” (p. 42). Whether the measurement of feedback can be seen as valid must be discussed within this set of framework values. Therefore, an explanation for the differences found in the coverage of quality criteria could be the alignment of feedback operationalization with these values. Two aspects, among others, could play a role in the selection of criteria: First, the specific connections between feedback and the other teaching quality aspects included in a framework, and second, the student outcomes that each framework prioritizes.

Our analysis of where feedback is located in the structure of each observation framework revealed that frameworks assign feedback to various dimensions of teaching quality which results in them relating feedback to other aspects of teaching quality in different ways. As has been suggested by Praetorious and colleagues ( 2020 ), it is important that framework developers clarify and explain these relationships. One reason for excluding a quality criterion from feedback-specific measurements might be because it also applies to other aspects of teaching quality within an observation framework. Thus, some criteria may not only be relevant for feedback quality but address fundamental issues of conceptualizing teaching quality within a framework. Therefore, it might be appropriate to capture these more generally rather than as a single feedback-specific aspect. For example, Charalambous and Praetorius ( 2020 ) argued that differentiation and adaptation may be an underlying dimension of teaching quality that is crucial on a general level, not just for the feedback process. Along the same lines, DMEE integrates differentiation (which is similar to adaptation) not as a dimension of teaching quality alongside others, but as a measurement factor for assessing the dimensions of teaching quality under consideration (see Creemers & Kyriakides, 2008 ).

As mentioned above, a decision about which quality criteria for feedback are included can also depend on which student outcomes are prioritized by an observation framework (Schoenfeld et al., 2018 ). For example, some frameworks may place particular emphasis on the developement of student achievement. Others, based mostly on social-interactive theories, may focus more on the development of self-regulation. Still others may place greater value on affective and motivational outcomes. The values that observation frameworks represent can lead to differences in the extent to which the criterion Motivation and Self-regulation is reflected. For example, frameworks that focus on student motivation may include this criterion in a more comprehensive manner by considering many facets of it. Frameworks that focus mainly on student achievement on the other hand may only want to ensure that the motivational aspect does not interfere with students’ use of the feedback information (e.g., because they feel embarrassed by the feedback provided).

In summary, there can be theoretical reasons for the prioritization of some quality criteria within an observation framework. There may not be just one valid way to conceptualize feedback in observation frameworks but clearer justifications and theory-based arguments for which aspects of feedback quality are included in an observation framework are needed. Moreover, even though there may be theoretical reasons leading to the prioritization of certain quality criteria, it is necessary for scholars to have a discussion about which criteria are indisputably central to capturing feedback. For example, it is difficult to think of reasons why the criteria Feed Back and Feed Forward would not be used for observational feedback measurement. Until a minimum consensus is reached, empirical research using observation frameworks should clearly communicate which quality criteria of feedback are measured. Studies must be transparent about how they investigate feedback to prevent a comparison of dissimilar criteria under the general label of “feedback quality.”

5.3 Fit of an observation framework’s overall measurement decisions with capturing feedback

The present analyses of approaches to measuring feedback are in line with previous bottom-up studies (e.g., Bell et al., 2019 ; Dobbelaer, 2019 ; Klette & Blikstad-Balas, 2018 ; Luoto et al., 2022 ; Praetorius & Charalambous, 2018 ; Schlesinger & Jentsch, 2016 ). The findings show that observation frameworks make differing measurement decisions. Decisions about how feedback is measured ( parsing : what units are observed; measurement factors : which factors are used for the assessment of feedback, such as quality or frequency; focus : whether students or teacher actions are in focus; rating scales : how differentiated are the measures) are primarily driven by each framework’s overall measurement approach which is applied when assessing all aspects of teaching quality within the framework (see also Praetorius & Charalambous, 2018 ).

These different measurement decisions and procedures in each framework might be another reason for the variation in coverage of feedback quality criteria that our analyses revealed. For example, some observation frameworks focus only on teacher actions when assessing teaching quality (e.g., ISTOF), while others focus both on teacher and student actions (e.g., TRU) (see Sect. 4.4.2 ). The integration of the feedback quality criteria Co-construction and Student Use may be predetermined by this general focus of an observation instrument. In fact, only observation frameworks that focus at least a bit on student behaviors covered these criteria. However, the aspects of Co-construction and Student Use are particularly relevant in contexts where feedback is given and received through verbal dialogue (e.g., Ruiz-Primo & Furtak, 2006 , 2007 ; Strijbos & Müller, 2014 ). As classroom observation frameworks focus mainly on verbal interactions because these are observable, the decision to exclude the mentioned criteria would need to be more clearly justified.

Other differences in measurement decisions could also have consequences (e.g., measurement factors, parsing decisions). Luoto et al. ( 2022 ) analyzed potential biases of measurement decisions using the example of the observation framework PLATO. They found that the time parsing in PLATO combined with the assessment of a combination of feedback quantity and quality led to systematic differences in the assessment of the feedback quality of types of lessons: Even though teachers provided the same quality and amount of feedback (in lesson A with organizational formats A and lesson B with organizational formats B), the feedback quality ratings for these lessons differed. Because feedback in lesson B was more equally spread throughout the lesson, the quality of feedback in each of the observed time units was ranked lower (it did not occur frequently enough to be ranked high). Thus, feedback quality overall was also ranked lower. If such biases also exist in other observation frameworks, it would be even harder to compare results between frameworks because they might come to different conclusions about the quality of feedback even when the same feedback criteria are covered. It is therefore important that future research investigate whether such biases also exist in other observation frameworks. Whether these biases are more or less pronounced, depending on the feedback criteria that frameworks cover, could be also investigated.

In general, scholars need to discuss which measurement factors (e.g., quality, quantity, differentiation) are most suitable for measuring feedback. It is especially unclear from the literature how useful it is to measure the frequency of feedback. For example, the successful timing of feedback seems to be dependent on learners’ prerequisites and the subjective difficulty of the task (see Adaptation ). Therefore, researchers should consider whether and how they use frequency to measure feedback quality.

In summary, an important point for a discussion of the valid measurement of feedback is whether the measurement approaches of observation frameworks are appropriate for capturing the various criteria for feedback quality. On a larger scale, consideration could also be given to whether the same parameters can generally be applied to the measurement of all of the aspects of teaching quality within a framework. As the example of feedback shows, construct-specific measurement approaches might be necessary, which we discuss in more detail in the following section.

5.4 Feedback measurement through observation

The present findings also raise questions about the validity of observations as a method for capturing feedback quality: Are all of the feedback quality criteria best measured using observations?

Our findings show that one criterion, Feed Up , is not addressed by any framework. Similarly, Adaptation , Co-construction , and how students use feedback for Information Processing and Self-regulation are only included in a few of the frameworks. The fact that some criteria have less of a presence in frameworks may suggest that they are more difficult to capture through observation. In fact, only feedback that is part of the observable conversation can be captured through classroom observation. However, feedback that serves to clarify learning goals and to assess students’ current learning status ( Feed Up ) could also be given in writing. Written feedback on student products (such as homework or work products that teachers take home for assessment) will in most cases not occur in an observable situation but could still include Feed Up. Teachers might, for example, use visual aids in their written feedback, such as rubrics or lists of success criteria. Research shows that the formative use of rubrics can successfully aid the feedback process and support students’ self-regulated learning and is perceived positively by students (Andrade & Du, 2005 ; Panadero & Jonsson, 2013 ). Moreover, the planning behind verbal feedback eludes observation. Shavelson et al. ( 2008 ) describe formative assessment and feedback provision along a continuum. Feedback can either be given spontaneously, be planned in advance for classroom interaction, or be embedded in the curriculum (e.g., through materials to be used for feedback provision at certain time points). Analyzing preparation tools such as lesson plans in addition to observations could reveal insights about the degree of planning behind observed feedback.

Alternative approaches to measuring how students use feedback, such as student or teacher surveys and classroom artifacts, are probably also needed. Individual processing of feedback ( Information Processing and Self-regulation ) is only accessible via observation in a small fraction of cases since it generally involves mental processes that may not be verbally articulated. Whether students find the feedback they received useful or whether they even understand the information has an impact on the effectiveness of feedback (Brett & Atwater, 2001 ; Harks et al., 2014 ), but is often not observable. Alongside this, the intersection of receiving feedback with learners’ skills and prerequisites also needs to be considered (Kerr, 2017 ; Narciss, 2008 ; Strijbos & Müller, 2014 ). As Hattie and Clarke ( 2018 ) highlight: “More attention needs to be given to whether and how students receive and act upon feedback, as there seems little point in maximizing the amount and nature of feedback given if it is not received or understood” (p. 5).

The validity issues that arise from relying on observation alone when measuring teaching quality have been raised before (Dobbelaer, 2019 ). When it comes to assessing the quality of feedback, future research needs to investigate how different measures can be best combined and how feedback can be measured more holistically with mixed methods designs. In this respect, too, it is important that multi-method frameworks develop clear theory-driven arguments about which feedback criteria are captured using observations and which are measured using other methods. For the comparability of research results, it would be ideal if in the future a minimum consensus could be found among researchers on which feedback criteria should be measured using observations.

5.5 Limitations and suggestions for future research

Some limitations have to be kept in mind when interpreting the results of this exploratory study. The literature review that provided the basis for defining feedback quality criteria was limited to the five most frequently cited articles on the topic. Although these provided important insights into what is necessary for a successful feedback process, there could be a bias in the selection. The most recent publication in the sample is from 2008, so further aspects of feedback quality that are not represented in the nine criteria may have been discussed in more recent literature. A more detailed review could lead to a more refined list of criteria with which the coverage of feedback in the 12 frameworks could be examined. Another aspect that could be underrepresented due to a potential citation bias is the influence of the subject or content in the feedback process. Since content-specific literature addresses a smaller readership, there may exist less frequently cited but still important articles on feedback quality in some subject areas. Future research looking at publications from different subject areas could enable distinctions between content-specific and general feedback quality criteria.

Because this study was exploratory, the investigation was restricted to the 12 classroom observation frameworks discussed in Praetorius and Charalambous ( 2018 ), and one therefore needs to be cautious with generalizations across the set of frameworks investigated. Researchers could expand this approach by exploring how other frameworks of measuring feedback and teaching quality relate to existing research and theories of feedback. For example, future research could investigate more frameworks specific to other subject areas (e.g., language arts). This way, finer grained conclusions about differences between frameworks specific to different subject areas and their measurement approaches could be drawn. Moreover, because we focused on teaching quality in general, we did not consider any feedback-specific measurement instruments. It would be an interesting question for future research to see how observation frameworks that measure teaching quality in general differ from instruments that focus on just one aspect, feedback assessment.

6 Conclusion

This study highlights the importance of classroom observation frameworks being more closely linked to and informed by the literature on feedback. It also demonstrates the need for a finer grained, improved understanding of the theoretical relationship between feedback quality and teaching quality within observation frameworks, and calls for more transparency. More concerted efforts to understand the benefits and limitations of classroom observation frameworks for capturing the quality and use of feedback are needed, alongside ideas for how they can be complemented by other measurement approaches.

Data availability

The classroom observation frameworks that were analyzed in this study are mostly publicly available but some have restricted access or are not public because they are under license. A list of the sources and their availability can be found in Appendix 2 .

Classroom observation frameworks encompass theoretical assumptions about teaching quality and are associated with instruments used to measure teaching quality in the light of those assumptions. We consider the theoretical foundations and measurements to be interrelated. Thus, for the purpose of this article, we use classroom observation frameworks as an umbrella term that covers both the theoretical assumptions and the associated instruments used to measure teaching quality (e.g., rubrics, procedures).

We understand a criterion as a group of several, interrelated sub-criteria that form a unit due to their similarity.

Searching for “feedback” on SCOPUS, for example, brings up more than 730,000 results (as of October 2022).

For a summary of different types of feedback messages, see Shute ( 2008 , p. 160).

Hattie and Timperley ( 2007 ) mention this as part of both Feed Up and Feed Back. We assigned the aspect of evaluating performance in relation to a goal to Feed Up.

About MECORS and QoT: While QoT focusses on teaching quality in general, MECORS assesses mathematics-specific aspects. Thus, together they form a hybrid framework (cf. Lindorff & Sammons, 2018 ). Here, we have considered them separately for a more fine-grained analysis.

A summary of the key sources that were used, and their availability, can be found in Appendix 2 .

All test frameworks are listed in Appendix 3 .

Andrade, H., & Du, Y. (2005). Student perspectives on rubric-referenced assessment. Practical Assessment Research and Evaluation, 10 (3), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.7275/g367-ye94

Article Google Scholar

Bangert-Drowns, R. L., Kulik, C.-L.C., Kulik, J. A., & Morgan, M. (1991). The instructional effect of feedback in test-like events. Review of Educational Research, 61 (2), 213–238. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170535

Bell, C. A., Dobbelaer, M. J., Klette, K., & Visscher, A. (2019). Qualities of classroom observation systems. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 30 (1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2018.1539014

Bell, C. A., Qi, Y., Witherspoon, M. W., Howell, H., & Torres, M. B. (2022). The TALIS video study observation system. OECD. Retrieved November 28, 2022, from https://www.oecd.org/education/school/TALIS_Video_Study_Observation_System.pdf

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: Principles Policy & Practice, 5 (1), 7–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969595980050102

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21 (1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5

Boston, M. D., & Candela, A. G. (2018). The instructional quality assessment as a tool for reflecting on instructional practice. ZDM Mathematics Education, 50 (3), 427–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-018-0916-6

Brett, J. F., & Atwater, L. E. (2001). 360° feedback: Accuracy, reactions, and perceptions of usefulness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86 (5), 930–942. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.86.5.930

Butler, D. L., & Winne, P. H. (1995). Feedback and self-regulated learning: A theoretical synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 65 (3), 245–281. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170684

Chappuis, J., & Stiggins, R. (2017). Introduction to student-involved assessment for learning (7 th ed.). Pearson

Charalambous, C. Y., & Litke, E. (2018). Studying instructional quality by using a content-specific lens: The case of the mathematical quality of instruction framework. ZDM Mathematics Education, 50 (3), 445–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-018-0913-9

Charalambous, C. Y., & Praetorius, A.-K. (2018). Studying mathematics instruction through different lenses: Setting the ground for understanding instructional quality more comprehensively. ZDM Mathematics Education, 50 (3), 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-018-0914-8

Charalambous, C. Y., & Praetorius, A.-K. (2020). Creating a forum for researching teaching and its quality more synergistically. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 67 , 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2020.100894

Creemers, B. P. M., & Kyriakides, L. (2008). The dynamics of educational effectiveness: A contribution to policy, practice, and theory in contemporary schools . Routledge.

Google Scholar

Ditton, H., & Müller, A. (Eds.). (2014). Feedback und Rückmeldungen : Theoretische Grundlagen , empirische Befunde , praktische Anwendungsfelder [Feedback and responses: Theoretical foundations, empirical findings, practical applications]. Waxmann

Dobbelaer, M. J. (2019). The quality and qualities of classroom observation systems. Ipskamp . https://doi.org/10.3990/19789036547161

Education Scotland. (2015). How good is our school? (4 th ed.). Education Scotland Foghlam Alba. Retrieved November 28, 2022, from https://education.gov.scot/improvement/Documents/Frameworks_SelfEvaluation/FRWK2_NIHeditHGIOS/FRWK2_HGIOS4.pdf

Harks, B., Rakoczy, K., Hattie, J., Besser, M., & Klieme, E. (2014). The effects of feedback on achievement, interest and self-evaluation: The role of feedback’s perceived usefulness. Educational Psychology, 34 (3), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2013.785384

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement . Routledge.

Hattie, J., & Clarke, S. (2018). Visible learning: Feedback . Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429485480

Hattie, J., Gan, M., & Brooks, C. (2017). Instruction based on feedback. In R. E. Mayer & P. A. Alexander (Eds.), Educational psychology handbook series. Handbook of research on learning and instruction (pp. 290–324). Routledge

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77 (1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Henderson, M., Ajjawi, R., Boud, D., & Molloy, E. (2019a). Identifying feedback that has impact. In M. Henderson, R. Ajjawi, D. Boud, & E. Molloy (Eds.), The impact of feedback in higher education: Improving assessment outcomes for learners (pp. 15–34). Palgrave Macmillan.

Henderson, M., Ajjawi, R., Boud, D., & Molloy, E. (2019b). Why focus on feedback impact? In M. Henderson, R. Ajjawi, D. Boud, & E. Molloy (Eds.), The impact of feedback in higher education: Improving assessment outcomes for learners (pp. 3–14). Palgrave Macmillan.

Heritage, M. (2010). Formative assessment: Making it happen in the classroom . SAGE Publications.

Book Google Scholar

Ilgen, D. R., Fisher, C. D., & Taylor, M. S. (1979). Consequences of individual feedback on behavior in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 64 (4), 349–371. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.64.4.349

Kerr, K. (2017). Exploring student perceptions of verbal feedback. Research Papers in Education, 32 (4), 444–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2017.1319589

Klette, K., & Blikstad-Balas, M. (2018). Observation manuals as lenses to classroom teaching: Pitfalls and possibilities. European Educational Research Journal, 17 (1), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904117703228

Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119 (2), 254–284.

Kyriakides, L., Creemers, B. P. M., & Panayiotou, A. (2018). Using educational effectiveness research to promote quality of teaching: The contribution of the dynamic model. ZDM Mathematics Education, 50 (3), 381–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-018-0919-3

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33 (1), 159–174. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310

Lindorff, A., & Sammons, P. (2018). Going beyond structured observations: Looking at classroom practice through a mixed method lens. ZDM Mathematics Education, 50 (3), 521–534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-018-0915-7

Luoto, J., Klette, K., & Blikstad-Balas, M. (2022). Possible biases in observation systems when applied across contexts: Conceptualizing, operationalizing, and sequencing instructional quality . Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-022-09394-y

Mory, E. H. (2004). Feedback research revisited. In D. H. Jonassen (Ed.) Handbook of research on educational communications and technology, (pp. 745–783). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410609519-40

Muijs, D., Reynolds, D., Sammons, P., Kyriakides, L., Creemers, B. P. M., & Teddlie, C. (2018). Assessing individual lessons using a generic teacher observation instrument: How useful is the international system for teacher observation and feedback (ISTOF)? ZDM Mathematics Education, 50 (3), 395–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-018-0921-9

Narciss, S. (2008). Feedback strategies for interactive learning tasks. In J. M. Spector (Ed.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (3 rd ed., pp. 125–143). Routledge.

Narciss, S., & Huth, K. (2004). How to design informative tutoring feedback for multimedia learning. In H. M. Niegemann, D. Leutner, & R. Brunken (Eds.), Instructional design for multimedia learning (pp. 181–195). Waxmann.

Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31 (2), 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572090

Panadero, E., & Jonsson, A. (2013). The use of scoring rubrics for formative assessment purposes revisited: A review. Educational Research Review, 9 , 129–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.01.002

Pianta, R. C., & Hamre, B. K. (2009). Conceptualization, measurement, and improvement of classroom processes: Standardized observation can leverage capacity. Educational Researcher, 38 (2), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X09332374

Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B. K., & Mintz, S. (2012). Classroom assessment scoring system (CLASS): Upper elementary manual . Teachstone.

Praetorius, A.-K., & Charalambous, C. Y. (2018). Classroom observation frameworks for studying instructional quality: Looking back and looking forward. ZDM Mathematics Education, 50 (3), 535–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-018-0946-0

Praetorius, A.-K., Grünkorn, J., & Klieme, E. (2020). Towards developing a theory of generic teaching quality: Origin, current status, and necessary next steps regarding the three basic dimensions model. Zeitschrift Für Pädagogik Beiheft, 66 (1), 15–36. https://doi.org/10.3262/ZPB2001015

Praetorius, A.-K., Klieme, E., Herbert, B., & Pinger, P. (2018). Generic dimensions of teaching quality: The German framework of three basic dimensions. ZDM Mathematics Education, 50 (3), 407–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-018-0918-4

Ruiz-Primo, M. A. (2011). Informal formative assessment: The role of instructional dialogues in assessing students’ learning. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 37 (1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2011.04.003

Ruiz-Primo, M. A., & Furtak, E. M. (2006). Informal formative assessment and scientific inquiry: Exploring teachers’ practices and student learning. Educational Assessment, 11 (3–4), 205–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/10627197.2006.9652991

Ruiz-Primo, M. A., & Furtak, E. M. (2007). Exploring teachers’ informal formative assessment practices and students’ understanding in the context of scientific inquiry. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 44 (1), 57–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20163

Sadler, D. R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science, 18 (2), 119–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00117714

Schaffer, E. C., Muijs, R. D., Kitson, C., & Reynolds, D. (1998). Mathematics enhancement classroom observation record . Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Educational Effectiveness and Improvement Centre.

Schlesinger, L., & Jentsch, A. (2016). Theoretical and methodological challenges in measuring instructional quality in mathematics education using classroom observations. ZDM Mathematics Education, 48 (1–2), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-016-0765-0

Schlesinger, L., Jentsch, A., Kaiser, G., König, J., & Blömeke, S. (2018). Subject-specific characteristics of instructional quality in mathematics education. ZDM Mathematics Education, 50 (3), 475–490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-018-0917-5

Schoenfeld, A. H. (2018). Video analyses for research and professional development: The teaching for robust understanding (TRU) framework. ZDM Mathematics Education, 50 (3), 491–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-017-0908-y

Schoenfeld, A. H., Floden, R., El Chidiac, F., Gillingham, D., Fink, H., Hu, S., Sayavedra, A., Weltman, A., & Zarkh, A. (2018). On classroom observations. Journal for STEM Education Research, 1 (1–2), 34–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41979-018-0001-7

Shavelson, R. J., Young, D. B., Ayala, C. C., Brandon, P. R., Furtak, E. M., Ruiz-Primo, M. A., Tomita, M. K., & Yin, Y. (2008). On the impact of curriculum-embedded formative assessment on learning: A collaboration between curriculum and assessment developers. Applied Measurement in Education, 21 (4), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/08957340802347647

Shute, V. J. (2008). Focus on formative feedback. Review of Educational Research, 78 (1), 153–189. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654307313795

Strijbos, J.-W., & Müller, A. (2014). Personale Faktoren im Feedbackprozess [Personal factors in the feedback process]. In H. Ditton & A. Müller (Eds.), Feedback und Rückmeldungen: Theoretische Grundlagen, empirische Befunde, praktische Anwendungsfelder [Feedback and responses: Theoretical foundations, empirical findings, practical applications] (pp. 83–134). Waxmann.

UTeach Institute (2022). UTeach observation protocol for mathematics and science. Retrieved November 28, 2022, from https://pd.uteach.utexas.edu/utop

van de Grift, W. (2007). Quality of teaching in four European countries: A review of the literature and application of an assessment instrument. Educational Research, 49 (2), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131880701369651

Vieluf, S., Praetorius, A.-K., Rakoczy, K., Kleinknecht, M., & Pietsch, M. (2020). Angebots-Nutzungs-Modelle der Wirkweise des Unterrichts: Ein kritischer Vergleich verschiedener Modellvarianten [Opportunity-use models of effective teaching: A critical comparison of different models]. Zeitschrift Für Pädagogik, 62 (1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.3262/ZPB2001063

Walkington, C., & Marder, M. (2018). Using the UTeach observation protocol (UTOP) to understand the quality of mathematics instruction. ZDM Mathematics Education, 50 (3), 507–519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-018-0923-7

Walkowiak, T. A., Berry, R. Q., Pinter, H. H., & Jacobson, E. D. (2018). Utilizing the M-Scan to measure standards-based mathematics teaching practices: Affordances and limitations. ZDM Mathematics Education, 50 (3), 461–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-018-0931-7

Wisniewski, B., Zierer, K., & Hattie, J. (2020). The power of feedback revisited: A meta-analysis of educational feedback research. Frontiers in Psychology, 10 , 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03087

Download references

Open access funding provided by University of Zurich

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Education, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Merle Ruelmann & Anna-Katharina Praetorius

Institute for School and Diversity, University of Teacher Education, Lucerne, Switzerland

Merle Ruelmann

Department of Education, University of Cyprus, Nicosia, Cyprus

Charalambos Y. Charalambous

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Merle Ruelmann .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

1.1 Appendix 1A Procedure of literature review

To identify influential publications, we searched both SCOPUS and ERIC for articles including the terms “feedback” in their title and “learn*,” “teach*,” “instruct*,” “student*,” or “class*” in either title, abstract, or keywords. Only results in the subject areas social science, educational science, psychology, and mathematics were considered so as to exclude feedback in the medical or other contexts. In the second step, the results were sorted by the highest number of citations and selected by reviewing the abstract. Articles that were not related to the field of learning and instruction were excluded. Special issue articles on feedback in the context of language acquisition were also excluded. The search results on SCOPUS and ERIC yielded five publications that clearly had a higher number of citations than the others. We selected these articles as a basis for our summary (see Table 3 ). We did not consider other articles from the list for two reasons: First, there was a remarkable drop in citations from the 5th to the 6th article on the list (900 citations less). Second, an additional analysis of a few other articles from the list did not contribute to the generation of new criteria for high-quality feedback but rather pointed to the same criteria that we had already identified on basis of the first five most cited publications

1.2 Appendix 1B Procedure of summarizing quality criteria

Our goal in summarizing the articles was to generate a list of distinct criteria for effective feedback. The list should indicate whether an observation frameworks has covered a certain aspect that is important for the impact of feedback. When reading the articles, we found that they deal with feedback in different ways. For example, Shute ( 2008 ) provides very detailed guidelines on what needs to be considered when feedback is given. These would yield numerous fine-grained criteria. Hattie and Timperley ( 2007 ), on the other hand, summarize previous findings on the effectiveness of feedback and formulate a series of broader assumptions, which would lead to fewer but largely overlapping criteria. Butler and Winnie (1995) focus on one specific aspect of the feedback process, the cognitive processing by learners and the benefits of feedback for self-regulated learning, to highlight a new perspective on feedback and integrate findings from two disparate research traditions. Therefore, the article provides insights on detailed, interrelated sub-criteria for aspects of feedback use.