The effectiveness of fiscal policy: contributions from institutions and external debts

Journal of Asian Business and Economic Studies

ISSN : 2515-964X

Article publication date: 30 May 2018

Issue publication date: 16 July 2018

The effectiveness of fiscal policy is an interesting field in literature of macroeconomics. The purpose of this paper is to investigate the effects of fiscal policy on economic growth under contributions from the differences in institutions and external debt levels.

Design/methodology/approach

The authors use panel data from 2002 to 2014 from 20 emerging markets and use GMM estimators for unbalanced panel data.

The results show positive growth effects of fiscal policy across emerging markets in the examined periods. Notably, the improvement in institutions promotes higher crowding-in effects of fiscal policy. In addition, this paper finds interesting evidences that the external debt has non-linear effects on economic growth, whereas the heterogeneous effects of fiscal policy on economic growth as positive effects in low indebted level and negative effect in high indebted level may explain the mechanism of this non-linear relationship.

Originality/value

This study proposes the non-linear relationship of fiscal growth effects in emerging economies under the dynamic of debt levels.

- Institutions

- Effectiveness

- Fiscal policy

- External debt

Phuc Canh, N. (2018), "The effectiveness of fiscal policy: contributions from institutions and external debts", Journal of Asian Business and Economic Studies , Vol. 25 No. 1, pp. 50-66. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABES-05-2018-0009

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2018, Nguyen Phuc Canh

Published in the Journal of Asian Business and Economic Studies . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

The field of the effectiveness of fiscal policy has re-highlighted in light of the 2008 global financial crisis with the new contemporary drivers such as external debt ( Ruščáková and Semančíková, 2016 ). Due to the complexity of the fiscal process by which it is not fully captured, different theories provide different answers regarding macroeconomic effects of fiscal policy and arguments about the suitability and real effects of government expenditures on economic growth which are still interesting field of study ( Bouakez et al. , 2014 ). Whereas, the main question in the literature of the fiscal policy’s effectiveness is that whether fiscal policy presents crowding-out and/or crowding-in effects in a country and what its drivers. In fact, many researchers try to find evidences with the parallel existence of both and mixed conclusions (see Ahmed and Miller, 2000 ; Heutel, 2014 ; Şen and Kaya, 2014 ).

The effects of fiscal policy on economic growth are driven by many factors such as the employment in the economy, the transparency of government, the composition of government expenditures, or even the government size (see Kasselaki and Tagkalakis, 2016 ; Hemming et al. , 2002 ). In empirical literature about the determinants of fiscal policy’s effectiveness, there are, in fact, some studies that consider the role of institutional framework such as corruption situation, economic freedom, democracy (see Baldacci et al. , 2004 ; Martinez-Vazquez et al. , 2007 ). Meanwhile, the burdens of external debt on the sustainability of fiscal policy are also concerned. For instance, Amato and Tronzano (2000) find the evidence that the debt maturity and the share of foreign-denominated debt are crucial determinants of exchange rate stability in Italia. Bal and Rath (2014) find that Indian economic growth is impacted by central government debt, total factor productivity growth, and debt-services in the short-run. Recent study, Doğan and Bilgili (2014) find that external borrowing has negative impact on growth both in regime at zero and regime at one, but the public debt has higher negative effects on economic growth and development, thus they conclude a non-linear relationship between economic development and borrowing variables. However, the literature of fiscal policy is lacking of the studies about the effectiveness of fiscal policy under the contributions from the institutions and external debts in a comprehensive work. Therefore, this study is conducted under the motivations from the study of Doğan and Bilgili (2014) by investigating the effectiveness of fiscal policy on economic growth under the relationships with the changes in the institutions and the burdens of external debt in the context of 20 emerging markets including Argentina, Bangladesh, Brazil, Bulgaria, China, Colombia, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Romania, Russia, South Africa, Thailand, Turkey, and Vietnam.

In this paper, we achieve our objectives by implementing following strategy. We first examine the impacts of fiscal policy on economic growth through the modified model of endogenous growth theory by incorporating government expenditure and controlling other common drivers of economic growth including capital, labor, financial development, technology, economic openness (trade and capital flows). Then, the institutional factors including government effectiveness, regulatory quality, and control of corruption are incorporated, respectively, to test the impacts of institutions on economic growth. Next, we use the interaction terms between government expenditure and institutions to examine the effectiveness of fiscal policy under the associations of institutional framework. We then estimate the growth model with the explanatory variables including both external debt level to GNI and its square to examine the non-linear relationship between external debt and economic growth. After that, we divide our data into two sub-samples (the low indebted countries and high indebted countries) to investigate the effectiveness of fiscal policy under two regimes.

By doing this strategy, we believe that this study has significant contributions to both theory and practice. First, this study has contribution to the literature of fiscal policy effectiveness and fiscal indebtedness by adding the effects of government expenditures under the external debt level and the associations with institutional quality. The results find significant evidences that the institutions enhance the effectiveness of fiscal policy. Notable, the external debt level presents the non-linear relationship with economic growth through the mechanism that the fiscal policy has the heterogeneous effects on economic growth: the crowding-in effect in low indebted level and crowding-out effects in high indebted one. Second, this study has significant implications for the authorizers in implementing the long-term sustainable fiscal policy in line with borrowing policy and the solutions for the high indebted countries that face to the dilemma of ineffective fiscal policy.

This paper is structured as following. Section 1 states our motivations of this study. Section 2 briefly presents literature reviews and then our arguments on the effectiveness of fiscal policy under the contributions from institutions and external debt. Methodology and data are provided in Section 3 . Section 4 presents the results and our discussions. The concluding remarks are discussed in Section 5 .

2. Literature reviews

The fiscal policy is considered with a wide range of literature, while the effectiveness of fiscal policy is seen under its’ impacts on the economic growth and the long-term sustainable development. In the literature of fiscal policy effectiveness, it is natural place to start with the Keynesian theory. In Keynesian model, the sticky price and excess capacity are assumed that contraries to the classical economics, so that aggregate demand determines output and government expenditures have a multiplier effect on aggregate demand and output ( Coddington, 1976 ). This view is also called as the crowding-in effects of fiscal policy, where the government should undertake the expenditure in the recession time to cover the lack of private consumption and investment ( Jahan et al. , 2014 ). However, some of extensions in the line of Keynesian model allow for crowding-out effects of fiscal policy, which means the expansion of government expenditure crowds out the private demand and then influences negatively on output, through the changes in interest rates and exchange rate in the case of open economy. With the assumption that the private investment is negative impacted by the increase in interest rate, the expansionary fiscal policy that backed by borrowing leads to the lower private investment due to higher interest rates (see Mundell, 1963 ; Fleming, 1962 ).

The neo-classical views focus on the determination of goods, outputs, and income distributions in markets through both supply and demand sides by adding the assumption of utility maximization of income-constrained individuals and firms under the boundary of factors in production and available information (see Davis, 2006 ). In which, the neo-classical economics raise the rational expectations in comparing to the adaptive expectations in Keynesian economics. This brings forward adjustments in economic factors that occur more progressively so that fiscal policy matters in not only long-term but also short-term period. And the permanent fiscal changes can lead to the crowding-out effects since private sectors expect the persistent changes in interest rates and exchange rates in this case (see Buiter, 1977 ; Arestis, 1979 ; Mundell, 1963 ; Fleming, 1962 ).

In addition to neo-classical economics, the Ricardian view that is based on Ricardian equivalence theorem assumes that the individuals are forward-looking in the current activities, which is also in contrasting with the Keynesian economics view as individuals rely on current income (see Barro, 1989 ; McCallum, 1984 ). In Ricardian view, individuals anticipate a present tax cut as higher government borrowing that turns into the higher taxes in the future so that there is no change in permanent income. This condition in along with the assumptions of no liquidity constraints and perfect financial markets lead to no change in private consumption in general ( Barro, 1974 ). Thus, Ricardian view suggests neither crowding-in nor crowding-out effects of fiscal policy ( Arestis, 2011 ; Şen and Kaya, 2014 ). However, if governments change lump-sum taxes for the fiscal policy, the features of progressive taxes will have impacts on permanent income and then the aggregate demand and output. As a result, the effectiveness of fiscal policy most likely depends on how it is paid in the future and the productivity of government expenditures ( Hemming et al. , 2002 ).

All above economic views require assumptions to be presence such as no liquidity constraints, perfect financial markets in Ricardian equivalence. However, these assumptions are usually un-existed thus the significance of theories is questioned in both theory and practice ( Haque and Montiel, 1989 ). Furthermore, there are some cases that the effectiveness of fiscal policy is explained by all of these views. For instance, if government is restricted by the fiscal rules to balance the fiscal budget in the long run, thus individuals may partial adjust their behaviors if they have short-term horizon which presents the presence of both Ricardian and neo-classical views. In the same idea, if the current path of government debt is not sustainable and future tax increases will be required to lower the debt, the Ricardian view may be presence in expansionary fiscal policy seemingly with the Keynesian view which depends on the level of public debt ( Sutherland, 1997 ). Or, if the government expenditure is in line of an upward-trending stochastic process that individuals believe a sharply fall when it approaches a specific “target point,” there will be a non-linear relationship between private consumption and government expenditure ( Bertola and Drazen, 1993 ). Therefore, the argument of a non-linear relationship between fiscal policy and economic growth makes sense in literature. However, the literature needs the explanations for the mechanism and empirical evidences.

Many previous studies have investigated the effects of fiscal policy in many countries, especially in advanced countries such as USA, Japan, European area [1] . Recently, Afonso and Strauch (2007) find that the European fiscal policy makes market swap spreads response in mostly around five basis points or less in 2002. Similarly, the study of Kameda (2014a) finds that an increasing of 26-34 basis points in real ten-year interest rates in responding to a percentage point increase in both the projected/current deficit-to-GDP ratio and projected/current primary-deficit-to-GDP ratios in Japan. Kameda (2014b) documents that the diffusion index of the attitudes of financial institutions have a definite impact on fiscal expansion effects. In particular, the government expenditure has non-Keynesian effects under the demand-enhancing effects if the existence of liquidity-constrained households when banks’ attitude toward lending is tight and the fiscal condition is bad. Bhattarai and Trzeciakiewicz (2017) use a DSGE analysis to examine the fiscal policy in UK. They note the highest GDP multipliers for government consumption and investment in the short-run, whereas capital income tax and public investment have long-run crowding-out effect on GDP. Moreover, they emphasize that the fiscal policy presents decreasing effects in a small open-economy scenario.

Besides the presence of plentiful empirical literature in the effectiveness of fiscal policy, this field of study got much less evidence on the short-term effects in developing countries due to data deficiencies, the structural/institutional factors in the last century (see Hemming et al. , 2002 ). For instance, Haque and Montiel (1989) find that the Ricardian equivalence is not supported in the developing countries due to liquidity constraints. Montiel and Haque (1991) go further by using the Mundell-Fleming model with rational expectations and full employment for 31 developing countries and conclude that the increasing of government expenditures have contractionary short-term and medium-term effects. Previous, Khan and Knight (1981) find positive nominal income elasticities of government expenditures and taxes and they are close to unity in 29 developing countries. Then, other empirical studies such as Easterly et al. (1994) document evidences that fiscal policy has crowding-out effects on private investment through the impacts on interest rates in developing countries. Meanwhile, empirical studies also provide evidences supporting for partial or/and fully existences of the Ricardian equivalence in developing countries such as Masson et al. (1995) , Giavazzi et al. (2000) .

However, the economic development in emerging market economies, which is a new definition of the development level of economies and nearly relating to the developing countries definition, boosts their roles in the world economy. In addition, the better fulfill of data have re-highlighted the interesting in investigating the effectiveness of fiscal policy by adding more methods and conditions into model for this group. For example, Cuadra et al. (2010) note that emerging market economies typically exhibit a pro-cyclical fiscal policy, where governments increase (decrease) expenditures in economic expansions (recessions) and rise (reduce) tax rates in bad (good) times. This situation is in line with the characteristic of counter-cyclical default risk in their business cycle. They also note that the incomplete markets and sovereign default risk premium have important roles in explaining the pro-cyclicality of public expenditures and tax rates in these economies. Therefore, the assumptions of Ricardian view are not existed that propose for the Keynesian or neo-classical views of fiscal policy.

No surprising that the debate on the role and the effectiveness of fiscal policy are continuous argued broadly in both literature and practice. Recently, Arestis (2011) notices that the “New Consensus in Macroeconomics,” recent developments in macroeconomics and macroeconomic policy, downgrades fiscal policy’s roles in contrasting with monetary policy due to its ineffective. Through a careful literature review and discussion at recent developments on the fiscal policy literature, he then concludes that fiscal policy does still have significant roles in economic policy through its impact on allocation, distribution and stabilization. However, researchers and authorizers have to careful consider the assumptions in economic theories of fiscal policy’s effectiveness as Ricardian and non-Ricardian economic existences, liquidity-constraints, and the endogenization of labor supply and capital accumulation. Meanwhile, other features of the economy should be considered in study the effectiveness of fiscal policy such as the institutional framework and the debt burden.

The dependence of fiscal policy’s effectiveness on institutional aspects is discussed under the literature with two main strands including the inside and outside lags of effects and the political economy considerations ( Hemming et al. , 2002 ). First, the fiscal policy has inside and outside lags, where the inside lags present the needed time to see that fiscal policy should changes, the outside lags are the function of the political process and the fiscal management that is the time for fiscal measures take effects on aggregate demand ( Blinder and Solow, 1974 ). Due to the long time to design, approval, and implementation, the inside lag may be longer, while the outside lag is more variable depending on the institutional environment. Second, the fiscal policy is impacted by the political considerations such as the fiscal illusion of public and policy-makers, the favor of transferring current fiscal burden to future generations, the limitation of government due to the debt accumulation, the delay of fiscal consolidations due to the political conflicts, and the function of current budget institutions that leads to high spending.

The institution is defined as the social rules of the game ( North, 1990 ), which includes “humanly devised,” “the rules of the game” to set “constraints” on human behavior, and the economic incentives (see North, 1981 ; Acemoglu and Robinson, 2008 ). The better institutions reduce asymmetric information problem, transaction cost, and risk, while they improve the market efficiency, especially efficiency of asset allocation ( Cohen et al. , 1983 ; Ho and Michaely, 1988 ; Williamson, 1981 ). Therefore, the better institutions should have positive associations with the effectiveness of fiscal policy since the lower asymmetric information problem, transaction cost, and higher market efficiency reduce both the inside and outside lags that then increase the efficiency of fiscal policy, especially the short-term effects.

The empirical literature in the field of fiscal policy had considered the role of institutional framework in some manners such as politics, democracy, economic freedom, and corruption in recent decades. Nelson and Singh (1998) , for instance, argue that a democratic political system permits active in a voluntary way, at the same time it creates competitive market forces conditions for economic growth. They also emphasize that the ineffective democracy regimes in developing countries detriments the growth. Lockwood et al. (2001) add that the political pressures determine the path of government spending, taxations and borrowing in Greece in the period 1960-1972, which means the fiscal policy may not follow a long-term efficiency for the country. Martinez-Vazquez et al. (2007) notice that the elimination of corruption is not usually an economic objective for the development, but the frustration with the lack of effectiveness of traditional economic theories and the recognition of the important roles of institutions and good governance practices have led the more attention to the corruption. Precisely, Dimakou (2015) finds that corruption constrains the fiscal capacity in taxations and increases the inflationary reliance.

However, no comprehensive study has considered the fiscal policy’s effectiveness under the institutional framework. More interesting, it lacks of empirical study in emerging market economies, which have more space in improving institutional quality and the economic growth. For example, the study of Aidt et al. (2008) document that corruption has a substantial negative impact on economic growth in high institutional quality economies, otherwise it has no impact on economic growth in low quality one. Ho et al. (2016) find that the improvement in country governance just enhances the effectiveness of banks and then promote the economic growth in developing countries, while it reduces these effects in developed countries due to smaller spaces for improvement. In addition, Wang et al. (2014) argue that the improvements in institutional quality just have strong effects on promoting economic development only when institutional quality is within a certain range. Therefore, we can argued that the improvement in institutions has strong impacts on the effectiveness of fiscal policy in emerging market economies.

The debt burdens, on the other hand, are also concerned in the literature of fiscal policy effectiveness. According to the review of Hemming et al. (2002) , the debt accumulation may be used as a strategic instrument to limit the fiscal capacity for future government, while the availability and cost of domestic and external borrowings are often major tackles on fiscal policy in developing countries. Thus, an emerging market economy with highly level of debts will determine the size of fiscal deficit in facing with more difficulties in assessing to international capital market (inaccessible or accessible with unfavorable terms), which then leads to the stronger crowding-out effects. Meanwhile, the low indebted countries have higher fiscal room for future government in implementing fiscal policy, which may undertake with the favorable terms of debt-financing, and that in turn promotes the crowding-in effects. Moreover, the individuals in high indebted countries are more sensitive to the government expenditures in following the framework of neo-classical views. The public may expect that the increasing of government expenditures in this case be in along with the less favorable terms of government’s borrowings and less efficiency of spending, which then stimulate individuals to cut back their current consumption more and more. As a result, this proposes higher crowding-out effects of fiscal policy. In contrast, the individuals in low indebted countries may less sensitive to the government expenditures, especially through the debt-financing spending, since the interest rates are less responsive and they are easier to access the financial markets, thus the fiscal policy is argued with the existence of crowding-in effects.

According to Kirchner and Wijnbergen (2016) , if banks hold substantially sovereign debt the effectiveness of expansionary fiscal is impaired since deficit-financed fiscal expansions reduce private access to credit in this case. Therefore, we use the total external debt, which includes public debt and private debt in this study to examine the impacts of debt on effectiveness of fiscal policy. This helps us consider the constraints of external debt of ability of private sector in accessing international financial markets. We argue that the expansionary fiscal policy in the highly indebted countries not only creates the crowding-out effects for the private sectors through the impacts on interest rates and exchange rates, but also crowds out the availability of private sectors in accessing into the international financial markets that creates more constraints for private sectors to implement economic activities. In contrast, these effects may not exist or less significance in the case of low indebted countries. As a summary, our hypothesis is argued that the relationship between fiscal policy with the economic growth is non-linear one as the positive effect in the low indebted level and the negative effect in the high indebted level.

In fact, the non-linear relationships between fiscal policy and economic factors are examined under some manners. Adam and Bevan (2005) investigate the relationship between fiscal deficits and economic growth for a panel of 45 developing countries and find evidence of a 1.5 percent GDP threshold deficit effect. They also find evidence that the deficits in line with high debt stocks exacerbates the adverse consequences of high deficits. While, Catão and Terrones (2005) examine inflation as non-linearly related to fiscal deficits through the sample of 107 countries over 1960-2001 period. They find a strong positive relationship between deficits and inflation among high-inflation and developing country groups, but it is not true among low-inflation advanced economies.

This fact suggests that we should consider the non-linear relationship between fiscal policy and economic growth in the emerging market economies. Emerging market economies are an emerging group of countries with interesting economic features in developing countries. While, the expected future revenue plays an important role in explaining the low fiscal limits of developing countries relating to developed countries ( Bi et al. , 2016 ). Therefore, the study of the relationships between institutions, external debts and the effectiveness of fiscal policy is more significant for both literature and practice. Next section presents the methodology and data.

3. Methodology and data

3.1 methodology.

In this paper, we recruit the common determinants of economic growth including capital, technology, labor, technology, capital flows, trade openness, and add the credit element for the basic model of economic growth from a vast of literature. With this beginning of basic model, we incorporate government expenditure to examine the impacts of fiscal policy on economic growth for 20 emerging market economies in the period 2002-2014, and follows the empirical model in Miller and Russek (1997) : (1) g i , t = ∂ 1 g i , t − 1 + ∂ 2 g d p p c i , t − 1 + α X t + β 1 G o v e x g i , t + ε t , s w i t h ε s ∼ i . i . d . N ( 0 , δ s , t 2 ) where i and t is country i at time t . g is GDP growth rate ( gdpg ) that proxies for the economic growth. The lag of g is put into the model to control for the dynamic of economic growth model, while the gdppc is logarithm of GDP per capita that presents for the starting economic development level. X is vector of control variables including: the capital investment factor that presented by the gross capital formation growth rate ( capg ); the labor factor that presented by the population growth rate ( popg ); the credit factor that presented by the logarithm of domestic credit to private sector by banks (credit); the technology factor that presented by the logarithm of total patent applications by both residents and non-residents (patent); the trade openness that presented by the logarithm of total trade to GDP (trade); and the capital flow that presented by the net inflows of foreign direct investment to GDP ( fdi ). govexg is the proxy for fiscal policy that presented by the general government final consumption expenditure growth rate. In this study, we use the government expenditure growth to proxy for the fiscal policy since it presents the changes in the fiscal policy, while the government revenue and tax have strong correlations with the government expenditure, thus in order to examine the fiscal policy effectiveness we only use the government expenditure. Even though the government expenditure can be best proxy for the fiscal policy.

All the definitions and sources of variables are presented in detail in Table I .

In next step, we also incorporate institutional factors into the model to investigate the effects of institutional quality on economic growth following the empirical model suggesting in Lee and Hong (2012) . In this step, we collect three dimensions of institutions from World Governance Indicators (Worldbank) including the government effectiveness ( Goveff ), regulatory quality ( Regu ), and control of corruption ( Concor ) to proxy for the institutional framework, respectively. Despite of critics about bias or lack of comparability and the utility of institutional quality in World Governance Indicators ( Thomas, 2010 ), there are many previous studies that use these indicators as the best proxies for institutional quality (see Zhang, 2016 ).

Next, we estimate the growth model with the explanatory variables including both external debt to GNI and its square to examine the non-linear relationship between external debt and economic growth. Basing on the results of these estimations, we then divide sample into two sub-samples basing on the level of external debt to GNI (see Table II ). Then, we apply the previous procedures to two sub-samples separately to investigate the effectiveness of fiscal policy under two debt regimes.

Our data are collected yearly from the period of 2002-2014 for 20 emerging countries [2] due to the time limitation in World governance indicators that have continuous data from 2002 to 2014. The government effectiveness, regulatory quality, and control of corruption are collected from World Governance Indicators, meanwhile all remained variables are collected from World Development Index (Worldbank). The data description is presented in Table II .

The data description shows that emerging market economies have high economic growth presenting by both average growth rates of GDP and GDP per capita. It is also noticed that they have high growth rate of investment in line with the target of FDI flows. Meanwhile, the institutional framework has wide space for improvement since their average levels are around the zero level (in the range from −2.5 to +2.5 in World governance indicators report). In addition, the governments in emerging market economies are almost under the expansionary phrases since their general government consumption growth rates are positive, but it may diversify among countries due to the high standard deviation.

4. Results and discussions

All our results are presented in the tables from Tables IV-VIII . In which, the estimators are presented with AR(2) test and Hansen/Sargan test depending on the first difference or system GMM methods. All the p -value of AR(2) test and Hansen/Sargan test are over 10 percent, which define the significance of GMM estimators as suggesting in Roodman (2009) .

Model (1) in Table III shows the results for basic model of economic growth. The significant positive impact of lag economic growth to itself shows that the higher economic growth in current year creates better conditions for growth in next year. This is easy to understand that the higher economic growth rate provides more sources such as capital and incentives for economic activities. While, the significant negative effect of log of GDP per capita with lag on economic growth suggesting the convergence trend in economy among emerging market group. Other control variables including capital formation, population growth, technology, foreign direct investment inflows, and trade openness have signs as expected by theories. It is easy to understand that the increasing of capital, labor, credit, inflow capital, trade openness, and innovations in technology have positive impacts on economic growth, especially in the case of emerging market economies that have space for all of these above drivers to contribute on growth. The results are consistent with literature and many previous empirical results. However, the insignificant positive effect of domestic credit on economic growth points out the argument that the financial markets in emerging market economies do not contribute enough to the growth.

With main explanatory variable, the growth rate of general government expenditure has significant positive effect on economic growth. This result suggests the existence of crowding-in effects of fiscal policy in the context of emerging market economies. Thus, our result supports for the Keynesian views of fiscal policy that the fiscal policy is needed to promote the economic growth in the emerging market economies since the sources for the growth from the private sectors are still limited at there and the roles of governments in creating the basic start for the development of other sectors. In addition, the public sectors still strongly present in emerging market economies through the state-owned enterprises so that the fiscal policy has significant impacts on the whole economy through its effects on public sectors.

The most important of our study, the impacts of institutions on the effectiveness of fiscal policy are examined and presented in Tables IV and V . The estimators prove that the improvement in institutions including aspects of government effectiveness, regulatory quality, and control of corruption enhances the effectiveness of fiscal policy in emerging market economies. In fact, all the interaction terms between government expenditure growth rate with each institutional indicator have positive impacts on economic growth. These results confirm our arguments that the better institutional framework helps boosting the effect of fiscal policy. This fact suggests that the better institutional quality reduces the crowding-out effects (reduces neo-classical effects) and promotes the crowding-in effects (enhances the Keynesian effects) of fiscal policy in emerging market economies. This finding has strong contributions to both literature of fiscal policy and practice in implementing fiscal policy in the context of emerging market economies. The essential requirements for the more effective fiscal policy are macro-measures to improve the institutional environment. This result also recommends that the empirical study in the field of fiscal policy should consider the institutional framework of countries that would be a potential explanatory factor. We then incorporate the external debt into the economic growth model to test the non-linear relationship. The results are provided in Table VI .

The significant positive coefficient of external debt level and significant negative coefficient of square of external debt level suggest that the external debt and economic growth has a non-linear relationship. This result is consistence with our discussion and theory, which shows strong implications for the long-term fiscal policy consolidations. Whereas, the government has to implement fiscal consolidation for the long-term sustainability of the economy. The negative coefficient of square of external debt level means that the external debt is in line with the higher economic growth when it is in low level; it is in line with lower economic growth when it is in high one. This result also requires deeper investigation for the mechanism of this non-linear relationship. The results in Tables VII and VIII provide us some interesting explanations.

By dividing the sample into two sub-samples: the low indebted countries (group 1) and high indebted countries (group 2) and regress the impacts of government expenditure and institutions on economic growth. We find that the increasing in government expenditure in group 1 has significant positive impact on economic growth, while it has insignificant negative impact in the group 2. The results suggest that the fiscal policy is effectiveness in stimulating the economic growth when countries have low debt burden, but it loses the effectiveness when countries face to high burdens of external debt. These findings are consistence with literature and our arguments. This means that the high indebted countries have less fiscal room and the unfavorable terms in accessing the international financial markets, while the high level of external debt creates constraints for the private sectors so that their fiscal policies present the crowding-out effects. We believe that the findings have significant contributions for literature, especially for the practice of fiscal policy. In addition, the results in Table VIII provide us additional interesting facts. While the fiscal policy is more effectiveness in the low indebted countries, the institutions are more effective in promoting economic growth in high indebted countries. This result suggests a very useful measure for the high indebted countries that they should not promoted to use the fiscal policy to stimulating economic growth, otherwise they must improve the institutional framework. As stated in previous findings, the fiscal policy presents crowding-out effects in the high indebted countries so that they face to the dilemma if they want to use fiscal policy to promote economic growth: they want to use the fiscal policy but they have less fiscal room, while they are under the burden of external debts and it makes fiscal policy less effective. Therefore, the rightful choice in this situation is institutional improvement and revolution.

5. Conclusion

This study collects the annual data from World Governance indicators and World Development Indicators of Worldbank for 20 emerging markets in the period 2002-2014 to examine the effectiveness of fiscal policy in the relationships with institutional framework and external debt burden. Applying the endogenous growth model with the common elements of economic growth including labor, capital, technology, credit, trade openness, and capital flow, we then incorporate the government expenditure to investigate the effective of fiscal policy. As our most notable contributions, we examine the impacts of institutions on the effectiveness of fiscal policy through the interaction terms between government expenditure and institutional indicators including government effectiveness, regulatory quality, and control of corruption. In addition, we examine the non-linear relationship between external debt and economic growth, where this relation is investigated more detail for its mechanism through the fiscal policy. Through GMM estimators for panel data, the study presents some meaningful findings.

First, the fiscal policy presents the crowding-in effects in emerging market economies in the period of 2002-2014. This result confirms the important role of fiscal policy in the case of emerging market economies, it is also consistence with our arguments and theory of Keynesian views. In fact, the emerging market economies present with the low level of capital accumulations, the low level of financial development so that the interest rates may not be too sensitive with the fiscal policy, while the fiscal policy is essential to build the basic infrastructure for the economic activities of private sectors. Thus, the fiscal policy is effective in promoting economic growth. This result suggests that Vietnam should consider the fiscal policy as an effective policy in tackling the downturn of the economic growth. Second, even the fiscal policy has positive effects on economic growth; the study finds interesting evidences that fiscal policy loses this effect in the case of high indebted countries. The results have significant contributions to both theories and practice. Whereas, the external debt creates constraints for the effectiveness of fiscal policy, especially in the case of high indebted countries. This relationship may explain the mechanism for the non-linear relationship between external debt and economic growth. Third, we find evidences that the improvement in institutions boosts the effectiveness of fiscal policy. This notable finding has very useful contributions to literature and implications for the practice in the case of emerging market economies. In which, the institutions under aspects of government effectiveness, regulatory quality, and control of corruption enhance the positive impacts of government expenditure on economic growth. In addition, the empirical results also suggest us essential measures for the government in dilemma of ineffective fiscal policy when they are in high indebted level that they should focus on the institutional improvement, which enhances the effectiveness of fiscal policy in one hand, it has positive impacts directly on economic growth on the other hand.

Variables, definitions and sources

Data description

Government expenditure and economic growth

Note: *,**,***Significant 10, 5 and 1 percent levels, respectively

See Hemming et al. (2002) for the more detail summary.

In total, 20 emerging markets are defined in introduction section and the number of emerging market economies is due to the availability of data.

Acemoglu , D. and Robinson , J. ( 2008 ), The Role of Institutions in Growth and Development , World Bank , Washington, DC .

Adam , C.S. and Bevan , D.L. ( 2005 ), “ Fiscal deficits and growth in developing countries ”, Journal of Public Economics , Vol. 89 No. 4 , pp. 571 - 597 , available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.02.006

Afonso , A. and Strauch , R. ( 2007 ), “ Fiscal policy events and interest rate swap spreads: evidence from the EU ”, Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money , Vol. 17 No. 3 , pp. 261 - 276 , available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2005.12.002

Ahmed , H. and Miller , S.M. ( 2000 ), “ Crowding‐out and crowding‐in effects of the components of government expenditure ”, Contemporary Economic Policy , Vol. 18 No. 1 , pp. 124 - 133 .

Aidt , T. , Dutta , J. and Sena , V. ( 2008 ), “ Governance regimes, corruption and growth: theory and evidence ”, Journal of Comparative Economics , Vol. 36 No. 2 , pp. 195 - 220 , available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2007.11.004

Amato , A. and Tronzano , M. ( 2000 ), “ Fiscal policy, debt management and exchange rate credibility: lessons from the recent Italian experience ”, Journal of Banking & Finance , Vol. 24 No. 6 , pp. 921 - 943 , available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378–4266(99)00112–0

Arestis , P. ( 1979 ), “ The ‘crowding-out’ of private expenditure by fiscal actions: an empirical investigation ”, Public Finance= Finances publiques , Vol. 34 No. 1 , pp. 36 - 50 .

Arestis , P. ( 2011 ), “ Fiscal policy is still an effective instrument of macroeconomic policy ”, Panoeconomicus , Vol. 58 No. 2 , pp. 143 - 156 .

Bal , D.P. and Rath , B.N. ( 2014 ), “ Public debt and economic growth in India: a reassessment ”, Economic Analysis and Policy , Vol. 44 No. 3 , pp. 292 - 300 , available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2014.05.007

Baldacci , E. , Hillman , A.L. and Kojo , N.C. ( 2004 ), “ Growth, governance, and fiscal policy transmission channels in low-income countries ”, European Journal of Political Economy , Vol. 20 No. 3 , pp. 517 - 549 .

Barro , R.J. ( 1974 ), “ Are government bonds net wealth? ”, Journal of Political Economy , Vol. 82 No. 6 , pp. 1095 - 1117 .

Barro , R.J. ( 1989 ), “ The Ricardian approach to budget deficits ”, Journal of Economic Perspectives , Vol. 3 No. 2 , pp. 37 - 54 .

Bertola , G. and Drazen , A. ( 1993 ), “ Trigger points and budget cuts: explaining the effects of fiscal austerity ”, The American Economic Review , Vol. 83 No. 1 , pp. 11 - 26 .

Bhattarai , K. and Trzeciakiewicz , D. ( 2017 ), “ Macroeconomic impacts of fiscal policy shocks in the UK: a DSGE analysis ”, Economic Modelling , Vol. 61 , pp. 321 - 338 .

Bi , H. , Shen , W. and Yang , S.-C.S. ( 2016 ), “ Fiscal limits in developing countries: a DSGE approach ”, Journal of Macroeconomics , Vol. 49 , pp. 119 - 130 , available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmacro.2016.06.002

Blinder , A.S. and Solow , R.M. ( 1974 ), “ Analytical foundations of fiscal policy ”.

Bouakez , H. , Chihi , F. and Normandin , M. ( 2014 ), “ Measuring the effects of fiscal policy ”, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control , Vol. 47 , pp. 123 - 151 , available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jedc.2014.08.004

Buiter , W.H. ( 1977 ), “ ‘Crowding out’ and the effectiveness of fiscal policy ”, Journal of Public Economics , Vol. 7 No. 3 , pp. 309 - 328 , available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0047–2727(77)90052–4

Catão , L.A.V. and Terrones , M.E. ( 2005 ), “ Fiscal deficits and inflation ”, Journal of Monetary Economics , Vol. 52 No. 3 , pp. 529 - 554 , available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2004.06.003

Coddington , A. ( 1976 ), “ Keynesian economics: the search for first principles ”, Journal of Economic Literature , Vol. 14 No. 4 , pp. 1258 - 1273 .

Cohen , K.J. , Hawawini , G.A. , Maier , S.F. , Schwartz , R.A. and Whitcomb , D.K. ( 1983 ), “ Friction in the trading process and the estimation of systematic risk ”, Journal of Financial Economics , Vol. 12 No. 2 , pp. 263 - 278 .

Cuadra , G. , Sanchez , J.M. and Sapriza , H. ( 2010 ), “ Fiscal policy and default risk in emerging markets ”, Review of Economic Dynamics , Vol. 13 No. 2 , pp. 452 - 469 , available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2009.07.002

Davis , J.B. ( 2006 ), “ The turn in economics: neoclassical dominance to mainstream pluralism? ”, Journal of Institutional Economics , Vol. 2 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 20 .

Dimakou , O. ( 2015 ), “ Bureaucratic corruption and the dynamic interaction between monetary and fiscal policy ”, European Journal of Political Economy , Vol. 40 , Part A , pp. 57 - 78 , available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2015.07.004

Doğan , İ. and Bilgili , F. ( 2014 ), “ The non-linear impact of high and growing government external debt on economic growth: a Markov regime–switching approach ”, Economic Modelling , Vol. 39 , pp. 213 - 220 , available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2014.02.032

Easterly , W. , Rodriguez , C.A. and Schmidt-Hebbel , K. ( 1994 ), Public Sector Deficits and Macroeconomic Performance , The World Bank , Washington, DC .

Fleming , J.M. ( 1962 ), “ Domestic financial policies under fixed and under floating exchange rates ”, Staff Papers , Vol. 9 No. 3 , pp. 369 - 380 .

Giavazzi , F. , Jappelli , T. and Pagano , M. ( 2000 ), “ Searching for non-linear effects of fiscal policy: evidence from industrial and developing countries ”, European Economic Review , Vol. 44 No. 7 , pp. 1259 - 1289 .

Haque , N.U. and Montiel , P. ( 1989 ), “ Consumption in developing countries: tests for liquidity constraints and finite horizons ”, The Review of Economics and Statistics , Vol. 71 No. 3 , pp. 408 - 415 .

Hemming , R. , Kell , M. and Mahfouz , S. ( 2002 ), “ The effectiveness of fiscal policy in stimulating economic activity: a review of the literature ”, Working Paper No. WP/02/208, IMF, Washington, DC .

Heutel , G. ( 2014 ), “ Crowding out and crowding in of private donations and government grants ”, Public Finance Review , Vol. 42 No. 2 , pp. 143 - 175 .

Ho , T.S. and Michaely , R. ( 1988 ), “ Information quality and market efficiency ”, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis , Vol. 23 No. 1 , pp. 53 - 70 .

Ho , P.-H. , Lin , C.-Y. and Tsai , W.-C. ( 2016 ), “ Effect of country governance on bank privatization performance ”, International Review of Economics & Finance , Vol. 43 , pp. 3 - 18 .

Jahan , S. , Mahmud , A.S. and Papageorgiou , C. ( 2014 ), “ What is Keynesian economics ”, Finance & Development , Vol. 51 No. 3 , pp. 53 - 54 .

Kameda , K. ( 2014a ), “ Budget deficits, government debt, and long-term interest rates in Japan ”, Journal of the Japanese and International Economies , Vol. 32 , pp. 105 - 124 , available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jjie.2014.02.001

Kameda , K. ( 2014b ), “ What causes changes in the effects of fiscal policy? A case study of Japan ”, Japan and the World Economy , Vol. 31 , pp. 14 - 31 , available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.japwor.2014.04.003

Kasselaki , M.T. and Tagkalakis , A.O. ( 2016 ), “ Fiscal policy and private investment in Greece ”, International Economics , Vol. 147 , pp. 53 - 106 , available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inteco.2016.03.003

Khan , M.S. and Knight , M.D. ( 1981 ), “ Stabilization programs in developing countries: a formal framework ”, Staff Papers , Vol. 28 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 53 .

Kirchner , M. and Wijnbergen , S.V. ( 2016 ), “ Fiscal deficits, financial fragility, and the effectiveness of government policies ”, Journal of Monetary Economics , Vol. 80 , pp. 51 - 68 , available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2016.04.007

Lee , J.-W. and Hong , K. ( 2012 ), “ Economic growth in Asia: determinants and prospects ”, Japan and the World Economy , Vol. 24 No. 2 , pp. 101 - 113 , available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.japwor.2012.01.005

Lockwood , B. , Philippopoulos , A. and Tzavalis , E. ( 2001 ), “ Fiscal policy and politics: theory and evidence from Greece 1960-1997 ”, Economic Modelling , Vol. 18 No. 2 , pp. 253 - 268 , available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264–9993(00)00038–9

McCallum , B.T. ( 1984 ), “ Are bond-financed deficits inflationary? A Ricardian analysis ”, Journal of political economy , Vol. 92 No. 1 , pp. 123 - 135 .

Martinez-Vazquez , J. , Boex , J. and Arze del Granado , J. ( 2007 ), “ Corruption, fiscal policy, and fiscal management ”, in Martinez-Vazquez , J. , Boex , J. and Arze del Granado , J. (Eds), Fighting Corruption in the Public Sector , Emerald Group Publishing Limited , pp. 1 - 10 .

Masson , P.R. , Bayoumi , T. and Samiei , H. ( 1995 ), “ Saving behavior in industrial and developing countries ”, Staff Studies for the World Economic Outlook , IMF working papers , Washington, DC , pp. 1 - 27 .

Miller , S.M. and Russek , F.S. ( 1997 ), “ Fiscal structures and economic growth: international evidence ”, Economic Inquiry , Vol. 35 No. 3 , pp. 603 - 613 .

Montiel , P. and Haque , N.U. ( 1991 ), “ Dynamic responses to policy and exogenous shocks in an empirical developing country model with rational expectations ”, Economic Modelling , Vol. 8 No. 2 , pp. 201 - 218 .

Mundell , R.A. ( 1963 ), “ Capital mobility and stabilization policy under fixed and flexible exchange rates ”, Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science/Revue canadienne de economiques Et Science Politique , Vol. 29 No. 4 , pp. 475 - 485 .

Nelson , M.A. and Singh , R.D. ( 1998 ), “ Democracy, economic freedom, fiscal policy, and growth in LDCs: a fresh look ”, Economic Development and Cultural Change , Vol. 46 No. 4 , pp. 677 - 696 .

North , D.C. ( 1981 ), Structure and Change in Economic History , Norton .

North , D.C. ( 1990 ), Institutions, Change and Economic Performance , Cambridge University .

Roodman , D. ( 2009 ), “ How to do xtabond2: an introduction to difference and system GMM in stata ”, The Stata Journal , Vol. 9 No. 1 , pp. 86 - 136 .

Ruščáková , A. and Semančíková , J. ( 2016 ), “ The European debt crisis: a brief discussion of its causes and possible solutions ”, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences , Vol. 220 , pp. 399 - 406 , available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.514

Şen , H. and Kaya , A. ( 2014 ), “ Crowding-out or crowding-in? Analyzing the effects of government spending on private investment in Turkey ”, Panoeconomicus , Vol. 61 No. 6 , pp. 631 - 651 .

Sutherland , A. ( 1997 ), “ Fiscal crises and aggregate demand: can high public debt reverse the effects of fiscal policy? ”, Journal of Public Economics , Vol. 65 No. 2 , pp. 147 - 162 .

Thomas , M.A. ( 2010 ), “ What do the worldwide governance indicators measure and quest ”, European Journal of Development Research , Vol. 22 No. 1 , pp. 31 - 54 .

Wang , Y. , Cheng , L. , Wang , H. and Li , L. ( 2014 ), “ Institutional quality, financial development and OFDI ”, Pacific Science Review , Vol. 16 No. 2 , pp. 127 - 132 , available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pscr.2014.08.023

Williamson , O.E. ( 1981 ), “ The economics of organization: the transaction cost approach ”, American Journal of Sociology , Vol. 87 No. 3 , pp. 548 - 577 .

Zhang , S. ( 2016 ), “ Institutional arrangements and debt financing ”, Research in International Business and Finance , Vol. 36 , pp. 362 - 372 , available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2015.10.006

Acknowledgements

This paper is funded by the University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City.

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Advertisement

Fiscal policy and economic growth: some evidence from China

- Original Paper

- Published: 10 May 2021

- Volume 157 , pages 555–582, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Jungsuk Kim ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5574-1303 1 ,

- Mengxi Wang 1 ,

- Donghyun Park 1 &

- Cynthia Castillejos Petalcorin 1

13k Accesses

22 Citations

Explore all metrics

A Correction to this article was published on 02 July 2021

This article has been updated

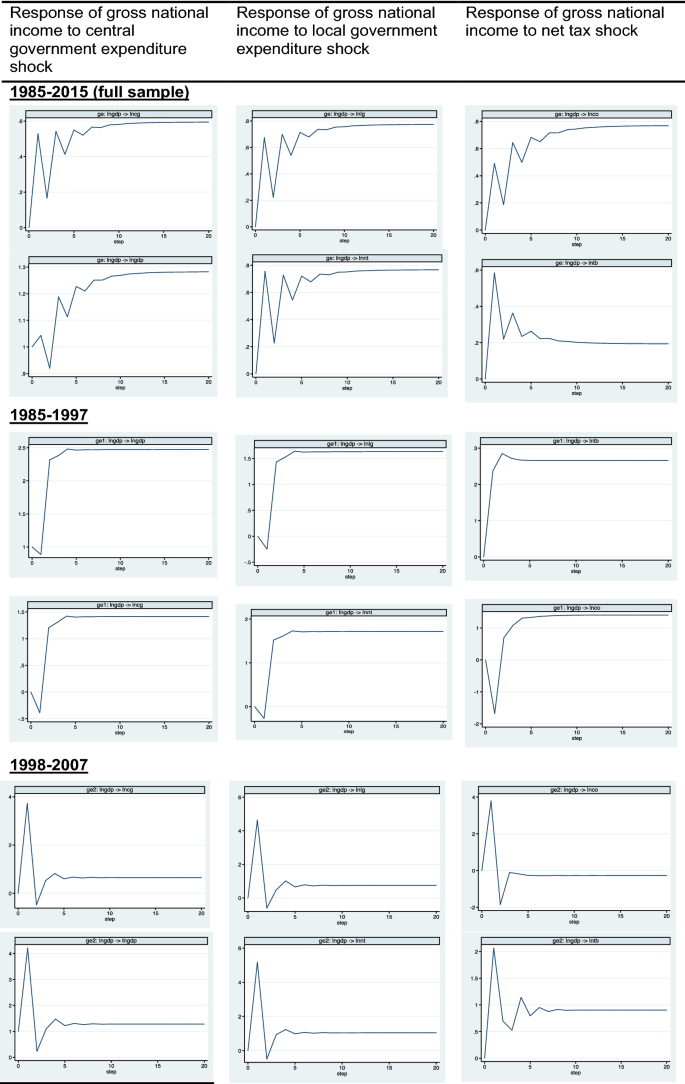

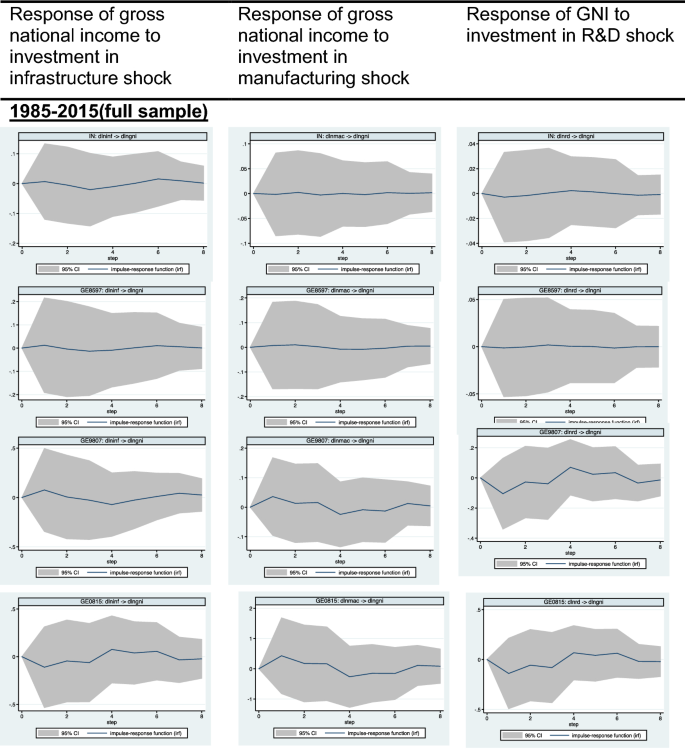

China has experienced profound economic and social changes in recent decades. During this period, China’s fiscal policy framework has been substantially reformed. The objective of this paper is to better understand the key features of the Chinese fiscal system and their impact on China’s economic growth. The study performs empirical analysis to identify the relationship between fiscal policy variables and economic growth. Its evidence suggests that local expenditures growth has a larger impact on output growth than central expenditures growth. The results also reveal that the response of output growth to anticipated changes in taxation was impeded by liquidity constraints. During the initial stages of market-oriented reform, growth of public investment in manufacturing sector contributed the most to output growth. During more recent periods, public investment in R&D made a substantial contribution. In addition, evidence indicates that long-term debt has a significant influence on China’s fiscal system, especially on government revenues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Cyclical variation of fiscal multipliers in Caucasus and Central Asia economies: an empirical evidence

Fiscal Policy in an Age of Secular Stagnation

Growth effects of budgetary fiscal variables in a panel of middle-income countries

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The strategic challenge facing Chinese policymakers is to ensure a gradual and smooth transition toward a more sustainable growth paradigm while maintaining healthy growth rates. The COVID-19 pandemic further strengthens the case for sustainable growth which protects the environment and benefits the poor. While Chinese policymakers have a number of policy tools at their disposal, fiscal policy—i.e. taxation and government expenditure is likely to be at the front and center of any policy package which can help China build back better after the pandemic. For example, fiscal spending on social safety nets may reduce risk and uncertainty facing households and thus encourage them to save less and spend more, thus strengthening domestic demand and economic recovery. Likewise, fiscal spending on COVID-19 vaccines can restore the health of the workforce and reduce social distancing restrictions which limit mobility, thus paving the way for the normalization of economic activity. Furthermore, an effective taxation system is needed to secure the fiscal resources for fiscal spending that promotes sustainable growth.

More generally, fiscal policy can influence economic growth through both macroeconomic and microeconomic channels (IMF, 2015a ). At the macroeconomic level, fiscal sustainability is the cornerstone of macroeconomic stability, which, in turn, is indispensable for economic growth. When the government spends more than its income—i.e. tax and non-tax revenues it collects on a sustained basis, the inevitable outcome is macroeconomic instability, which creates uncertainty among companies and deters private investment. At the microeconomic level, both taxes and spending can influence the behavior of firms in ways that can promote growth. For example, well-targeted tax incentives can promote greater investment by companies and foster higher productivity through research and development (R&D). Another example is public spending on education and health care, which contribute to human capital formation, a core ingredient of economic growth.

The central objective of our paper is to empirically examine the relationship between fiscal policy and economic growth in China. The effectiveness of China’s countercyclical fiscal response to the global financial crisis highlighted the sizable impact of fiscal policy on short-term growth. However, in this paper, we are interested in the effect of fiscal policy on China’s growth beyond the short term.

Our paper contributes to the existing empirical literature on the nexus between fiscal policy and economic growth in China in a number of ways. Above all, we look at the growth impact of not only central government’s fiscal policy but also the impact of local governments’ fiscal policy. In light of the substantial role of local governments in China’s fiscal policy, examining the impact both central and local governments on China’s economic growth gives us a more accurate understanding of the effect of fiscal policy on China’s growth. In addition, our empirical analysis is enriched and extended in several significant directions. In particular, we incorporate both investment and external debt into our empirical analysis of the link between fiscal policy and economic growth in China. Furthermore, we divide the sample period into three different sub-sample periods of China’s economic development. In addition, our analysis distinguishes between automatic fiscal policy and discretionary fiscal policy.

Our econometric analysis yields a number of interesting findings. Our evidence suggests that local government expenditures have a larger impact on output growth than central government expenditures or net taxes. In addition, both government expenditure and net tax multipliers seem to change during the course of a business cycle. However, net tax growth becomes relatively but progressively more influential in the long run. The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 briefly reviews the relevant literature, Sect. 3 describes the data and methodology, Sect. 4 reports and discusses the empirical results, and Sect. 5 concludes the paper.

2 Literature review

There is a growing literature on the relationship between fiscal policy and economic growth. Through government expenditure and taxation, fiscal policy can have lasting effects on medium- and long-term economic growth through several major channels. However, the mix of appropriate policies will depend on the idiosyncratic conditions, capacities, and preferences of each country (IMF, 2015b ). The country-specific nature of policy mix ensures that the policy track is sustainable in the short- and long run and also enhances the credibility of authorities (Kumhof et al., 2010 ).

Fiscal policy can promote economic growth through both macroeconomic and microeconomic channels. At the macroeconomic level, sound and responsible fiscal policy can affect aggregate demand and stabilize the economic cycle, thus boosting business confidence, investment, and long-term growth. At the microeconomic level, fiscal policy can impact private sector behavior via encouraging employment, investment, and productivity. (IMF, 2015b ; Gerson, 1999 ). For example, efficient public investment in infrastructure can boost the productivity of all firms and industries, and reforming capital income taxes can encourage private investment. It is also important to understand the feedback between microeconomic effects and aggregate effects (Ramey, 2009 ).

The distinctive features of new Keynesian conditions include imperfect competition, forward looking expectations by individuals and firms, and some form of rigidity in prices or wages. New Keynesian model arguably remains the dominant framework in most policy modeling (Gali, 2018 ). Since policy interest rates fell to their near-zero levels in the aftermath of the 2009 global financial crisis (GFC), there is a renewed enthusiasm in new Keynesian models to examine fiscal policy effectiveness at the zero lower bound of nominal interest (e.g. Christiano et al., 2011 ; Eggertson, 2009 ).

Policymakers around the world turned to fiscal stimulus packages to support economic growth during GFC (Ramey, 2009 ). US and European countries adopted countercyclical fiscal policies, including tax cuts and government purchases, mainly to boost short-run and medium-run growth (Ramey, 2009 ). Many economies in developing Asia too implemented countercyclical fiscal policy to support domestic demand during the global crisis (Jha et al., 2014 ). In comparing the magnitude of government spending multipliers in US, Cogan et al., ( 2010 ) found out that the GDP and employment impacts estimated by using new Keynesian model are much smaller than the estimates from old Keynesian models.

A growing number of studies on advanced economies based on various modelling refinements provide a mixed picture of size of the fiscal multiplier. For fiscal policy to be effective, the government multiplier should be large to make a difference in the direction of the economy. However, multipliers are largely dependent on varying country-specific circumstances (Ramey & Zubairy, 2014 ). Distinguishing between recessions and expansions, Riera-Crichton et al. ( 2014 ) found out that the response of the economy to changes in government spending is asymmetric. The long-run multiplier for bad times is 2.3 compared to 1.3 for good times, and up to 3.1 for extreme recessions. On the other hand, using US quarterly data covering wars and recessions, Ramey and Zubairy ( 2014 ) found that the estimated multipliers are below 1 irrespective of the amount of slack in the economy. But the results are more mixed for the lower zero bound state, with some specifications producing multipliers as high as 1.5. An extensive literature review by Hemming et al. ( 2002 ) concluded that fiscal multipliers are overwhelmingly positive but small. In a study of 10 developing Asian economies in 1985–1999, Jha et al. ( 2014 ) computed the tax-cut multipliers to be 2.0 at its maximum over a two-year horizon while government expenditure multipliers are around 1.0.

A number of empirical studies support a positive relationship between fiscal policy and medium- and long-term economic growth. In advanced economies, the growth effect can be as high as 0.75 percentage points and even higher in developing countries. For example, IMF ( 2015c ) finds that automatic fiscal stabilizers help prevent public debt accumulation and foster growth. Tax reform can lift long-term growth by as much as 0.5 percentage points while shifting the composition of government spending toward infrastructure can add 0.25 percentage points. Baldacci et al. ( 2010 ) concluded that fiscal deficit reductions based on broadening the tax base while maintaining public investment can support medium-term growth in both advanced and developing countries. Finally, macroeconomic instability associated with large fiscal deficits distorts price signals and thus causes volatility of returns on investment and misallocation of resources, see Fatás and Mihov ( 2013 ) and Fisher ( 1993 ).

The existing literature encompasses various empirical methodologies for assess the effect of fiscal policy shocks. The Cholesky identification approach assumes that fiscal policy variables and output variables do not have any structural effects on each other (e.g. Fatás & Mihov, 2001 ; Favero, 2002 ). The sign restriction approach, popularized by Uhlig ( 1997 ), identifies fiscal policy shocks using sign restrictions on impulse responses. The approach is traditionally used to assess the impact of monetary policy shocks (Mountford & Uhlig, 2002 ). Another is the strand of empirical studies which includes Romer ( 1994 ); Ramey and Shapiro ( 1999 ); Edelberg et al. ( 1998 ) and Blanchard and Perroti ( 1999 , 2002 ). These studies distinguish between automatic policy and discretionary policy, and estimate the elasticity of tax on output using external information. Sims and Zha ( 1999 ) presented several issues related to the calculation of error bands using Monte Carlo integration, bootstrapping, and impulse response functions (IRFs) for structural vector autoregression (VAR). The methodology was further developed and refined by Perotti ( 2002 ). In contrast to monetary policy, decision and implementation lags in fiscal policy imply that there is limited scope for discretionary fiscal policy in response to unexpected movements in economic activity within a quarter.

Fiscal policy is making a substantial contribution to China’s economic growth. For instance, a massive countercyclical fiscal stimulus during the GFC prevented a recession in China and contributed to the recovery of other emerging and developing economies (Fardoust et al., 2012 ). China's forceful fiscal response was made possible by the fact that China had ample fiscal space when the GFC hit. Kong and Feng ( 2019 ) find that China’s fiscal policy is generally countercyclical and achieves its desired economic effects. Interestingly, a tax cut is found to have a positive impact on output in China (Jha et al. 2014 ; Kong & Feng, 2019 ). This can be attributed to taxation's function in promoting a more efficient resource allocation. For instance, Lam and Wingender ( 2015 ) find that improving the progressivity of personal income taxes, introducing property taxes, and setting up a comprehensive value-added tax can promote China’s growth and boost fiscal revenues as well as reduce fiscal deficit.

Some studies have estimated China’s fiscal multipliers. Using the IMF’s GIMF model, Kumhof et al. ( 2010 ) find fiscal multipliers for China are broadly in line with United States. Chen et al. ( 2017 ) estimated that China’s fiscal multiplier increased from 0.75 in 2001–2008 to 1.4 in 2010–2015, with the biggest impact on the manufacturing sector. Using annual data for 1,800 Chinese counties, Guo et al. ( 2016 ) obtained local government fiscal multipliers of approximately 0.6, which is much lower than the estimates of most previous studies. The effects of local public spending were most pronounced in non-tradable industries. Cove et al. (2010) calibrated New Keynesian model to China and finds that public expenditures which are managed by the local authority and can be financed by raising taxes on local households and issuing local government debt can have New Keynesian effects on output growth. Some province-level studies imply that that fiscal decentralization contributed to higher economic growth (Lin & Liu, 2000 and Jin et al. 2005 ).

3 Empirical framework

In this section, we describe the data and empirical framework used in our analysis. For developing countries such as China, monthly data are difficult to find even in statistical yearbook, so we use statistical way to transfer the yearly data into monthly data. For the Dickey-Fuller test and Phillips-Perron test, we converted all variables to first differences of natural logarithms to address the unit root problem in level data. Table 1 below lists the sources of our data and Table 2 below summarizes the mean values of data in three sub-periods—1985–1997, 1998─2007, and 2008─2015. The period from 1985 to 1997 marks the pre-Asian financial crisis (AFC) period, 1998–2007 is the period between AFC and global financial crisis (GFC), and 2008–2015 is the post-GFC period. To compare the effect of fiscal policy in the three sub-periods, we also denoted the three sub-periods from economic structure reform perspective. The 3 sub-periods are domestic demand-oriented model, three-wheel-oriented (investment, consumption, and trade) model, and export-oriented model, and they track the evolution of China’s economic structure. For the identification of the fiscal policy shocks, the variables in the first structural model—government expenditure model are central government expenditure, local government expenditure, net tax, fixed asset investment, and gross domestic product per capital (GDP per capital).

In the Cholesky decomposition approach, there are several methods for estimating the precision matrix. For example, the order can be selected thorough comparison of the cross-correlation coefficients from the data, Granger causality verification, impact response function, or decomposition of expected error term (Chang & Tsay, 2010 ; Chen & Leng, 2015 ; Park, 2020 ; Wagaman & Levina, 2009 ). But in many applications, the variables often do not have a natural order. That is, the justifiable variable order is not available or the pre-determination of the variable order is not possible before the analysis (Xiaoning & Xinwei, 2020 ). When using structural VAR, one may order the variables with an economic rationale and in this case, the order would be specified by the author’s own matrix (Ludvigson et al., 2020 ).

According to de Castro Fernández & Hernández de Cos ( 2006 ), in the ordering between variables such as taxes and expenditure, it could be quite difficult to fully justify which one should come first. Nevertheless, this choice does not seem to substantially affect the main results, mainly due to the low and non-significant correlation between expenditure and net-tax shocks. In this regard, we decided to re-estimate under the alternative assumption that taxes or consumption come first. Since the residuals of reduced-form in the expenditure and net-tax equations showed low and non-significant correlation, the differences with the baseline VAR results, if any, were minimal. As a matter of fact, none of the variables under analysis showed different response profiles and the output multipliers were almost identical.

Barro ( 1990 ) assumed that government expenditure is financed contemporaneously by a flat-rate income tax which is 0.25 for the Cobb–Douglas case. In our study, we removed the substitution effect between government expenditure and tax through applying 75% of tax as the original tax before regression. Then we follow Perotti ( 2002 ) to build up a model including net tax but without division of the government sector into central versus local government. Table 3 below shows the summary statistics of the main variables.

The structural vector autoregression (SVAR) model can be formed as below:

Perotti ( 2002 ) divides fiscal policy into discretionary measures and automatic stabilizers. The effectiveness of discretionary measures is quantified by the size of the multipliers while the effectiveness of the automatic stabilizer is measured by the magnitude of an exogenous shock that fiscal policy can smoothen out. The formula to calculate net tax is:

The orthogonalization matrix \(P_{s} = A^{ - 1} B\) is then related to the error covariance matrix by \(\Sigma = P_{s} P_{s}^{^{\prime}}\) in the short-run SVAR model.

The variables in the second structural model—the investment model—are investment in infrastructure, investment in manufacturing, investment in R&D, net tax, and GNI. We choose these three investment variables in light of the aggregate nature of the production functions. The exact contribution of infrastructure to productivity remains limited in the sense that the production function approach does not cover all welfare aspects of infrastructure investment. For example, the impact of infrastructure investments on consumers is not taken into account. Furthermore, the production function approach cannot give an ex-ante evaluation of specific investment projects. Industrial development plays an important role in the economic growth of developing countries such as China. Furthermore, manufacturing investment influences the productivity performance of these countries. Romer ( 1986 ) developed the endogenous growth model, in which technological innovation is created in a R&D sector that combines human capital and knowledge.

The second structural model also share the Cobb–Douglas production function which is in line with Gramlich ( 1994 ) and Voss et al ( 2003 ). In this model, public capital is disaggregated into various components. This exercise is similar in spirit to Easterly and Rebelo ( 1993 ) which also examines whether particular sectors of public investment are important for economic growth. In China’s case, investment in infrastructure is calculated by adding investment in management of water, conservancy, environment and public facilities; transport, storage and post; production and supply of electricity, heat, water and gas, services to households, repair and other services; and education; culture, sports and entertainment and public management, and social security and social organizations. Data are collected for 1985–2015 from various editions of the Statistical Yearbook of China from 2003 through 2016.

In the third structural model, external debt is divided into short-term and long-term debt. Other variables are government expenditure and government revenue. Favero and Giavazzi ( 2007 ) emphasized the importance of including the debt feedback effect when estimating the effects of fiscal policy shocks. The identified system is:

where \(Y_{t} = \left( {g_{e} g_{r} } \right)\) , which denote government expenditure and government revenue, \(d_{l,t}\) is long-term debt to GDP ratio, \(d_{s,t} { }\) is short-term debt to GDP ratio, and \(d_{l}^{*}\) and \(d_{s}^{*}\) are unconditional mean values.

Generally speaking, in terms of impulse-response functions, fiscal multipliers reflect the impact of fiscal variables on GDP or GNI, or \(\frac{{\Delta Y_{t} }}{{\Delta X_{t} }},{ }\) where \(X\) is government expenditure or tax. However, Davig et al. ( 2010 ) point out that current fiscal policy will affect future fiscal policy, which means that ordinary impulse response cannot accurately capture the impact of fiscal policy on the economy. Therefore, Perotti ( 2004 ) applies the SVAR model to calculate cumulative impulse response and cumulative multipliers as \(\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{{{\text{i}} = 0}}^{{\text{k}}} \Delta {\text{Y}}_{{{\text{t}} + {\text{k}}}} }}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{{{\text{i}} = 0}}^{{\text{k}}} \Delta {\text{X}}_{{{\text{t}} + {\text{k}}}} }}\) , which can be interpreted as the ratio of the cumulative value of GDP or GNI to the cumulative value of government expenditure or tax. In addition, Mountford and Uhlig ( 2009 ) develop a new method assuming the discount rate as \(\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{{{\text{i}} = 0}}^{{\text{k}}} \mathop \prod \nolimits_{{{\text{i}} = 0}}^{{\text{i}}} \left( {1 + {\upgamma }_{{{\text{t}} + {\text{i}}}} } \right)^{{ - {\text{i}}}} \Delta {\text{Y}}_{{{\text{t}} + {\text{k}}}} }}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{{{\text{i}} = 0}}^{{\text{k}}} \mathop \prod \nolimits_{{{\text{i}} = 0}}^{{\text{i}}} \left( {1 + {\upgamma }_{{{\text{t}} + {\text{i}}}} } \right)^{{ - {\text{i}}}} \Delta {\text{X}}_{{{\text{t}} + {\text{k}}}} }}\) . In our paper, we calculate the multipliers based on three models: \(\frac{{\Delta {\text{Y}}_{{\text{t}}} }}{{\Delta {\text{X}}_{{\text{t}}} }} \times \frac{{\text{Y}}}{{\text{X}}}\) ; \(\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{{{\text{i}} = 0}}^{{\text{k}}} \Delta {\text{Y}}_{{{\text{t}} + {\text{k}}}} }}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{{{\text{i}} = 0}}^{{\text{k}}} \Delta {\text{X}}_{{{\text{t}} + {\text{k}}}} }} \times \frac{{\text{Y}}}{{\text{X}}}\) ; and \(\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{{{\text{i}} = 0}}^{{\text{k}}} \mathop \prod \nolimits_{{{\text{i}} = 0}}^{{\text{i}}} \left( {1 + {\text{r}}_{{{\text{t}} + {\text{i}}}} } \right)^{{ - {\text{i}}}} \Delta {\text{Y}}_{{{\text{t}} + {\text{k}}}} }}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{{{\text{i}} = 0}}^{{\text{k}}} \mathop \prod \nolimits_{{{\text{i}} = 0}}^{{\text{i}}} \left( {1 + {\text{r}}_{{{\text{t}} + {\text{i}}}} } \right)^{{ - {\text{i}}}} \Delta {\text{X}}_{{{\text{t}} + {\text{k}}}} }} \times \frac{{\text{Y}}}{{\text{X}}}\) ; which represent the multiplier, cumulative multiplier, and discounted cumulative multiplier.

4 Empirical results

In this section, we discuss and report the main findings of our empirical analysis, for both the full sample period of 1985─2015 as well as the three sub-periods. We use monthly data because approving and implementing new measures in response to innovations in the macroeconomic variables typically takes at least one month. Therefore, the use of monthly variables allows for setting the discretionary contemporaneous response of government expenditure or net taxes to GNI to zero. Pre-regression analysis shows the presence of co-integrating relations and hence a possible specification of a vector error correction model but the number of long-term equations shows no feasibilities. Blanchard and Perotti ( 2002 ) find no significant differences between estimated results obtained with and without taking the co-integrating relation into account. With regard to the choice of the interest rate, most existing studies use the short-term interest rate. For example, Chan et al. ( 1992 ) uses the one-month US treasury bond yield, while Nowman ( 1997 ) uses the one-month LIBOR. Footnote 1 This study selects 7-day interbank interest rate as the discount rate. It should be pointed out that our sample period 1985 to 2015 coincides with a significant expansion of China’s external debt in tandem with sustained rapid economic growth.

4.1 Test of Johansen cointegration

We use Johansen cointegration test to obtain preliminary evidence of cointegration relationships. The result provides evidence in favor of two cointegration relationship in Model 1. The lag length was chosen by final prediction error (FPE) to be 2. Footnote 2 Tables 4 and 5 show the results for Model 1 and Model 2, respectively.

In a similar way, the result of Johansen cointegration test for Model 2 shows evidence in favor of three cointegration relationship. The lag length was chosen by SBIC to be 1. Footnote 3

4.2 Test for unit roots