- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About The American Journal of Jurisprudence

- About the Notre Dame Law School

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Why Religious Freedom is a Human Right

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Daniel Philpott, Why Religious Freedom is a Human Right, The American Journal of Jurisprudence , Volume 68, Issue 3, December 2023, Pages 177–194, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajj/auae003

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This essay presents a fresh defense of the human right of religious freedom. It addresses two versions of skepticism of this human right, one a liberal variant, which questions religious freedom’s distinctiveness, the other a post-modern variant, which questions religious freedom’s universality. The case for a universal and distinct human right of religious freedom rests upon the claim that religion is a basic human good, manifesting human dignity and warranting a human right. The essay details four respects in which religion fulfills the meaning of a basic human good. Religion is a purposive set of acts, or practices; is a definable phenomenon whose core meaning is right relationship with a superhuman power; entails both an intrinsic good and derivate goods; and is universal in its scope. Finally, crucial to the human right of religious freedom is religion’s interiority, that is, its critical involvement of will, mind, and heart.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2049-6494

- Print ISSN 0065-8995

- Copyright © 2024 Notre Dame Law School

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Berkley Center

Is religious freedom necessary for other freedoms to flourish.

By: Thomas Farr

August 7, 2012

America’s True History of Religious Tolerance

The idea that the United States has always been a bastion of religious freedom is reassuring—and utterly at odds with the historical record

Kenneth C. Davis

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Presence-God-Country-Bible-Riots-631.jpg)

Wading into the controversy surrounding an Islamic center planned for a site near New York City’s Ground Zero memorial this past August, President Obama declared: “This is America. And our commitment to religious freedom must be unshakeable. The principle that people of all faiths are welcome in this country and that they will not be treated differently by their government is essential to who we are.” In doing so, he paid homage to a vision that politicians and preachers have extolled for more than two centuries—that America historically has been a place of religious tolerance. It was a sentiment George Washington voiced shortly after taking the oath of office just a few blocks from Ground Zero.

But is it so?

In the storybook version most of us learned in school, the Pilgrims came to America aboard the Mayflower in search of religious freedom in 1620. The Puritans soon followed, for the same reason. Ever since these religious dissidents arrived at their shining “city upon a hill,” as their governor John Winthrop called it, millions from around the world have done the same, coming to an America where they found a welcome melting pot in which everyone was free to practice his or her own faith.

The problem is that this tidy narrative is an American myth. The real story of religion in America’s past is an often awkward, frequently embarrassing and occasionally bloody tale that most civics books and high-school texts either paper over or shunt to the side. And much of the recent conversation about America’s ideal of religious freedom has paid lip service to this comforting tableau.

From the earliest arrival of Europeans on America’s shores, religion has often been a cudgel, used to discriminate, suppress and even kill the foreign, the “heretic” and the “unbeliever”—including the “heathen” natives already here. Moreover, while it is true that the vast majority of early-generation Americans were Christian, the pitched battles between various Protestant sects and, more explosively, between Protestants and Catholics, present an unavoidable contradiction to the widely held notion that America is a “Christian nation.”

First, a little overlooked history: the initial encounter between Europeans in the future United States came with the establishment of a Huguenot (French Protestant) colony in 1564 at Fort Caroline (near modern Jacksonville, Florida). More than half a century before the Mayflower set sail, French pilgrims had come to America in search of religious freedom.

The Spanish had other ideas. In 1565, they established a forward operating base at St. Augustine and proceeded to wipe out the Fort Caroline colony. The Spanish commander, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, wrote to the Spanish King Philip II that he had “hanged all those we had found in [Fort Caroline] because...they were scattering the odious Lutheran doctrine in these Provinces.” When hundreds of survivors of a shipwrecked French fleet washed up on the beaches of Florida, they were put to the sword, beside a river the Spanish called Matanzas (“slaughters”). In other words, the first encounter between European Christians in America ended in a blood bath.

The much-ballyhooed arrival of the Pilgrims and Puritans in New England in the early 1600s was indeed a response to persecution that these religious dissenters had experienced in England. But the Puritan fathers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony did not countenance tolerance of opposing religious views. Their “city upon a hill” was a theocracy that brooked no dissent, religious or political.

The most famous dissidents within the Puritan community, Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson, were banished following disagreements over theology and policy. From Puritan Boston’s earliest days, Catholics (“Papists”) were anathema and were banned from the colonies, along with other non-Puritans. Four Quakers were hanged in Boston between 1659 and 1661 for persistently returning to the city to stand up for their beliefs.

Throughout the colonial era, Anglo-American antipathy toward Catholics—especially French and Spanish Catholics—was pronounced and often reflected in the sermons of such famous clerics as Cotton Mather and in statutes that discriminated against Catholics in matters of property and voting. Anti-Catholic feelings even contributed to the revolutionary mood in America after King George III extended an olive branch to French Catholics in Canada with the Quebec Act of 1774, which recognized their religion.

When George Washington dispatched Benedict Arnold on a mission to court French Canadians’ support for the American Revolution in 1775, he cautioned Arnold not to let their religion get in the way. “Prudence, policy and a true Christian Spirit,” Washington advised, “will lead us to look with compassion upon their errors, without insulting them.” (After Arnold betrayed the American cause, he publicly cited America’s alliance with Catholic France as one of his reasons for doing so.)

In newly independent America, there was a crazy quilt of state laws regarding religion. In Massachusetts, only Christians were allowed to hold public office, and Catholics were allowed to do so only after renouncing papal authority. In 1777, New York State’s constitution banned Catholics from public office (and would do so until 1806). In Maryland, Catholics had full civil rights, but Jews did not. Delaware required an oath affirming belief in the Trinity. Several states, including Massachusetts and South Carolina, had official, state-supported churches.

In 1779, as Virginia’s governor, Thomas Jefferson had drafted a bill that guaranteed legal equality for citizens of all religions—including those of no religion—in the state. It was around then that Jefferson famously wrote, “But it does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods or no God. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.” But Jefferson’s plan did not advance—until after Patrick (“Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death”) Henry introduced a bill in 1784 calling for state support for “teachers of the Christian religion.”

Future President James Madison stepped into the breach. In a carefully argued essay titled “Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments,” the soon-to-be father of the Constitution eloquently laid out reasons why the state had no business supporting Christian instruction. Signed by some 2,000 Virginians, Madison’s argument became a fundamental piece of American political philosophy, a ringing endorsement of the secular state that “should be as familiar to students of American history as the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution,” as Susan Jacoby has written in Freethinkers , her excellent history of American secularism.

Among Madison’s 15 points was his declaration that “the Religion then of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every...man to exercise it as these may dictate. This right is in its nature an inalienable right.”

Madison also made a point that any believer of any religion should understand: that the government sanction of a religion was, in essence, a threat to religion. “Who does not see,” he wrote, “that the same authority which can establish Christianity, in exclusion of all other Religions, may establish with the same ease any particular sect of Christians, in exclusion of all other Sects?” Madison was writing from his memory of Baptist ministers being arrested in his native Virginia.

As a Christian, Madison also noted that Christianity had spread in the face of persecution from worldly powers, not with their help. Christianity, he contended, “disavows a dependence on the powers of this world...for it is known that this Religion both existed and flourished, not only without the support of human laws, but in spite of every opposition from them.”

Recognizing the idea of America as a refuge for the protester or rebel, Madison also argued that Henry’s proposal was “a departure from that generous policy, which offering an Asylum to the persecuted and oppressed of every Nation and Religion, promised a lustre to our country.”

After long debate, Patrick Henry’s bill was defeated, with the opposition outnumbering supporters 12 to 1. Instead, the Virginia legislature took up Jefferson’s plan for the separation of church and state. In 1786, the Virginia Act for Establishing Religious Freedom, modified somewhat from Jefferson’s original draft, became law. The act is one of three accomplishments Jefferson included on his tombstone, along with writing the Declaration and founding the University of Virginia. (He omitted his presidency of the United States.) After the bill was passed, Jefferson proudly wrote that the law “meant to comprehend, within the mantle of its protection, the Jew, the Gentile, the Christian and the Mahometan, the Hindoo and Infidel of every denomination.”

Madison wanted Jefferson’s view to become the law of the land when he went to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. And as framed in Philadelphia that year, the U.S. Constitution clearly stated in Article VI that federal elective and appointed officials “shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support this Constitution, but no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.”

This passage—along with the facts that the Constitution does not mention God or a deity (except for a pro forma “year of our Lord” date) and that its very first amendment forbids Congress from making laws that would infringe of the free exercise of religion—attests to the founders’ resolve that America be a secular republic. The men who fought the Revolution may have thanked Providence and attended church regularly—or not. But they also fought a war against a country in which the head of state was the head of the church. Knowing well the history of religious warfare that led to America’s settlement, they clearly understood both the dangers of that system and of sectarian conflict.

It was the recognition of that divisive past by the founders—notably Washington, Jefferson, Adams and Madison—that secured America as a secular republic. As president, Washington wrote in 1790: “All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunity of citizenship. ...For happily the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens.”

He was addressing the members of America’s oldest synagogue, the Touro Synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island (where his letter is read aloud every August). In closing, he wrote specifically to the Jews a phrase that applies to Muslims as well: “May the children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants, while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and figtree, and there shall be none to make him afraid.”

As for Adams and Jefferson, they would disagree vehemently over policy, but on the question of religious freedom they were united. “In their seventies,” Jacoby writes, “with a friendship that had survived serious political conflicts, Adams and Jefferson could look back with satisfaction on what they both considered their greatest achievement—their role in establishing a secular government whose legislators would never be required, or permitted, to rule on the legality of theological views.”

Late in his life, James Madison wrote a letter summarizing his views: “And I have no doubt that every new example, will succeed, as every past one has done, in shewing that religion & Govt. will both exist in greater purity, the less they are mixed together.”

While some of America’s early leaders were models of virtuous tolerance, American attitudes were slow to change. The anti-Catholicism of America’s Calvinist past found new voice in the 19th century. The belief widely held and preached by some of the most prominent ministers in America was that Catholics would, if permitted, turn America over to the pope. Anti-Catholic venom was part of the typical American school day, along with Bible readings. In Massachusetts, a convent—coincidentally near the site of the Bunker Hill Monument—was burned to the ground in 1834 by an anti-Catholic mob incited by reports that young women were being abused in the convent school. In Philadelphia, the City of Brotherly Love, anti-Catholic sentiment, combined with the country’s anti-immigrant mood, fueled the Bible Riots of 1844, in which houses were torched, two Catholic churches were destroyed and at least 20 people were killed.

At about the same time, Joseph Smith founded a new American religion—and soon met with the wrath of the mainstream Protestant majority. In 1832, a mob tarred and feathered him, marking the beginning of a long battle between Christian America and Smith’s Mormonism. In October 1838, after a series of conflicts over land and religious tension, Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs ordered that all Mormons be expelled from his state. Three days later, rogue militiamen massacred 17 church members, including children, at the Mormon settlement of Haun’s Mill. In 1844, a mob murdered Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum while they were jailed in Carthage, Illinois. No one was ever convicted of the crime.

Even as late as 1960, Catholic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy felt compelled to make a major speech declaring that his loyalty was to America, not the pope. (And as recently as the 2008 Republican primary campaign, Mormon candidate Mitt Romney felt compelled to address the suspicions still directed toward the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.) Of course, America’s anti-Semitism was practiced institutionally as well as socially for decades. With the great threat of “godless” Communism looming in the 1950s, the country’s fear of atheism also reached new heights.

America can still be, as Madison perceived the nation in 1785, “an Asylum to the persecuted and oppressed of every Nation and Religion.” But recognizing that deep religious discord has been part of America’s social DNA is a healthy and necessary step. When we acknowledge that dark past, perhaps the nation will return to that “promised...lustre” of which Madison so grandiloquently wrote.

Kenneth C. Davis is the author of Don’t Know Much About History and A Nation Rising , among other books.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Religious Freedom, Essay Example

Pages: 6

Words: 1663

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

There is religious liberty to the documented sources on how it impacts every discussion input and their ability to understand every detailed historical analysis in America, which has led to controversial opinions. In the United States, the history of religion has seen it adopt and undergo many amendments to incorporate the establishment of diversified choices and show the importance of freedom development (Curtis 2016). The American religious society is still on a halt when pondering the main establishments in every clause of the existing religious beliefs and relative functions. The main question is relishing the existing establishment with a focus on understanding the importance of belief in religion to different human beings.

The declaration on the existing models states that someone’s belief in a religion should not be questioned on any grounds, and the declarations are only relative to function, and a unanimous decision can be handling the listed requirements on efforts planning and associational differences. A tussle in the court proved that it is important to understand a basic planning choice in understanding a positional requirement over the choices and options. Arguments by Murray shows that variated philosophical arguments can be essentially documented in a religious freedom context(Thomas, Jolyon Baraka 2019). In so making, the contented approach considers religious freedom as a natural law that protects human dignity

In Maryland, religious freedom and empowerment are used as a basic agenda in turning things around and analyzing major concepts, which serves as a philosophical concept in understanding and causing the emergence of western ideologies as a basic concept with development ideas. The state generational law is a relief system that brings firms’ belief into the proposition that the main declarations are prohibited from taking diversified state positions. The public office is a unanimous concept of position. Therefore any congress must make laws to understand the establishment of the diversified religious concepts that shall help redress the diversified differences in religious freedom. In understanding agenda, the United States safeguards interests in religion as the amendment provides freedom of expression belief and expression, and this makes the government request the damages and complaints, which has an indirect relationship right offering an establishment of religion having direct light access, which offers partial damages to complaints over religions and bars, anyone, from favoring religion against each other.

Religion is important and should be partial to all regardless of the relative social institutions. According to (Hurd, Elizabeth, and Shakman 2015), the admission selection in a school, for instance, was denied access from a radiotherapy class, which affected a major understanding of similar happenings, which questions everyone’s guiding principle as a regulated thought process and analysis. Similar happenings are observed as Dr. Doughterty tells Brandon that “religion is a field that requires to be exercised in another location.”Who guides this location addresses that religion cannot be practiced in any school despite the contributions that come with religion as a major undertaking into the required process. The major reason for undertaking various record labels is that an undertaking is anti-discriminatory, and every conscious choice is justifiable, which makes it entirely unconstitutional. Since every university should offer training to any qualified student regardless of their rational concept or choices, the federal court system calls for diversified cases on achieving this as a personal direction. This concept is key as every religious principal shall have a display showing the main regulated concepts in analyzing the main tools of practice as a major introductory element of success. This principle offers integrity when handling religion as it is direct from a morality of underlying principles of religion.

The morality concept underlies every meaning with a commitment to the underlying informational speech concept as a term for understanding the main laws of an individual as a justice system. Reiterating GeorgeWashingtons’ farewell analysis(Hurd, Elizabeth and Shakman 2015) where every character is promoted as a promotional planning occurrence, the important requirements are offered as an object of interest, and the justice system is expressed as a tool of operation, which helps to build an analysis output. In his statement, He observed that religion could be a characteristic that operates on the minimum underlying principles as an objective planning agenda, and the expressions can be limited to options and choices. This can be a leading principle in understanding the morality of options when respecting the laws and the justice systems since everything is sustained in a built-in concept model where the sustainability of the main analysis impacts the choice planning model. The views and opinions are obligated to the religious freedom development concept where there should be existing regulations controlling the practice of religion.

According to ideals made in a court system, religious freedom should only be based on ideals, not concepts. The American government shows a morality of choice and operation when putting the decisions from self-regulated ideals on how religion can be conceived to show an end of an operation, and the basic survival skills can be a religious affiliation or adaptation to interest. A choice panel is a religious description of the ascertained interest in the program, which is ideal for any American system(Kaufman, Robert and Stephan Haggard 2019). The moral society observes a diversified conflict of interest, and this religion self affects the principled agenda from a pragmatic context, and the arguments are based on a religious operation.

The liberty of religion should be preserved as a necessary anchorage with a personal rule to the free will of choice and concept operation. This basic liberty agenda has tools for activity, and this is a liberation concept with an established choice of interest, which prohibits regional influence, and this is religion affliction which offers a free exercise of the regulated thought system(Thomas, Jolyon Baraka 2019). Moreover, the congress system should make no laws regarding the religious establishment. This can offer laws respecting religious establishment and planning, which offers confirmation of interest and prohibition of the choice model on a free exercise of the amendment with an average choice. The amendment observed in the constitutional affiliation offers a free exercise of will and planning; this makes everyone assemble

American technology follows the regulated knowledge gap and influences the prohibited choice of interest with a bridge freedom of speech and the right to understand amendment issues and criteria for the First Amendment in analyzing some of the religious affiliations as congress is limited from making any laws concerning having an establishment that affects comprehension of thoughts and ideas. The amendments and petitions are important in regulated awareness.

There are existing court cases, such as the Johnson and Gregory case, where the Republican conventional agenda protested the violation of interest held in Dallas. Moreover, in the Texas statute, the desecration of objectivity is venerated in defense of the American flag, which was observed to be a religious emblem. Their reasoning was on a 5-4 basis, making it a religious symbolic speech(Thomas, Jolyon Baraka ,2019). In observation of the constitutional amendment is an offensive statement that suppresses the anger aroused solely based on apprehension, which is venerated in practices. The diversity observed in belief systems is conclusive feedback of the McCreary cases v.ACLU, which has led to the unconstitutional crisis, and this displays the ignorance of the political offices in some of the religious beliefs which led to the “establishment clause.”It prohibited access to religious beliefs, which happened to a different extent. Another case is a court examining the anti-bigamy statute in the First Amendment, which banned every regulated belief system which allowed the government to function regardless of the existing religious belief.

The American society, the statute shows that the religious practice in America is believed to be a public life crisis, and the federal government upholds this religious practice. The examination of plural marriage is a religious practice upheld in federal law courts(Lewis and Andrew., 2019). The republicans lament the religious trends in America, while the democrats hold a chain of mixed reactions over the issues. The gap issues show that religious activities in America are activity-based, and the dependence can only be manifested in a free-will organization that makes every one of the existing languages available (Kaufman, Robert R., and Stephan Haggard 2019). The religious basis is a religious belief, and organizations that seem to do good strengthen the religious organizations. American society believes that the republican institutions regulate religious institutions, making the parties have a highly regulated jurisdictional functional difference. The existing gaps are uniformly religious with a religious acumen under different religious Acumen, a religious role from a diversified societal outlook.

In conclusion, Religious Freedom in America can not be tolerated, and the amendments exist based on religious practice, which means discrimination cannot help different countries to diversify. However, a country can tolerate religion to a certain extent, which helps the government to speak against people’s discrimination with a regulated government belief. Altogether, the government should not discriminate against the existing religious difference since there exist establishment claws where there is supposed to be the authority with freedom of religion in the American government where the delegations have a standstill w with a civic authority. The constitutional basis is a provision on the amendment choices which prevents a vast majority of outcomes from any of their particular belief system, and this has been a destructive measure against involving the government in any of the existent affairs. The essential existence holds a diversified passion of existence holding a different position, but all the same, religious practice should be a liberty to every different individual.

Works Cited

Curtis, Finbarr. “The production of American religious freedom.” The Production of American Religious Freedom . New York University Press, 2016. Curtis, Finbarr. “https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.18574/9781479823734/html/

Hurd, Elizabeth Shakman. “Beyond religious freedom.” Beyond Religious Freedom . Princeton University Press, 2015. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9781400873814/html/

Kaufman, Robert R., and Stephan Haggard. “Democratic decline in the United States: What can we learn from middle-income backsliding?.” Perspectives on Politics 17.2 (2019): 417-432. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/perspectives-on-politics/article/democratic-decline-in-the-united-states-what-can-we-learn-from-middleincome-backsliding/1D9804407AAD81287AA0CA620BABDEA6/

Lewis, Andrew R. “The inclusion-moderation thesis: The US republican party and the Christian right.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics . 2019. https://oxfordre.com/politics/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-665/

Thomas, Jolyon Baraka. Faking Liberties: Religious Freedom in American-Occupied Japan . Class 200: New Studies in Reli, 2019. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=WQOHDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=Religious+Freedom+in+America&ots=5VZKkyalIz&sig=b_lBgP6LeB3Jq-h4kSz6qYPWajA/

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Health Diary Project, Essay Example

Exploring the Benefits and Risks of Electronic Flight Bags, Research Paper Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

The state, religion, and freedom: a review essay of Persecution & toleration

- Published: 20 November 2020

- Volume 35 , pages 257–266, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Metin Coşgel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1249-1535 1

443 Accesses

5 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

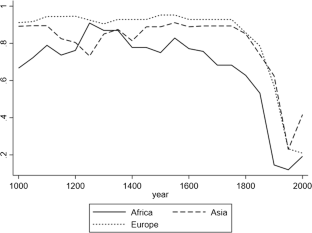

Persecution and Toleration offers a novel and superb analysis of the birth of religious freedom. Rather than seek an ideational account of the rise of religious freedom, Johnson and Koyama investigate changes in the institutional environment that governed the relationship between religion and the state. These changes made it in the interest of policy makers in modern Europe to grant greater religious freedom by transitioning from identity rules to impersonal laws in maintaining order. The book introduces a new thought-provoking conceptual framework that can be extended to examine the complicated history of the state’s interaction with religion, comparative analysis of the relationship between state capacity and political legitimacy, and various other issues concerning the treatment of minorities and heterodox practices around the world.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Ideological Rhetoric of the Trump Platform and Edmund Burke’s Theory of a Generational Compact

Religious Extremism

Revisiting the islam-patriarchy nexus: is religious fundamentalism the central cultural barrier to gender equality?

Researchers have recently studied legitimizing relationship between political and religious authorities to study institutions, such as state religion, and puzzling phenomena, such as bans on technology. See, for example, Coşgel and Miceli ( 2009 ), and Coşgel et al. ( 2012 , 2018 ).

Coşgel, M. M., Miceli, T. J., & Rubin, J. (2012). The political economy of mass printing: Legitimacy and technological change in the ottoman empire. Journal of Comparative Economics, 40 (3), 357–371.

Article Google Scholar

Coşgel, M., Histen, M., Miceli, T. J., & Yildirim, S. (2018). State and religion over time. Journal of Comparative Economics, 46 (1), 20–34.

Coşgel, M., & Miceli, T. J. (2009). State and religion. Journal of Comparative Economics, 37 (3), 402–416.

Gill, A. (2008). The political origins of religious liberty . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Google Scholar

Iannaccone, L. R. (1998). Introduction to the economics of religion. Journal of Economic Literature, 36 (3), 1465–1495.

Johnson, N. D., & Koyama, M. (2019). Persecution & toleration: The long road to religious freedom . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

North, D. C., Wallis, J. J., & Weingast, B. R. (2009). Violence and social orders: A conceptua framework for interpreting recorded human history . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rubin, J. T. (2017). Rulers, religion, and riches: Why the west got rich and the Middle East did not . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, The University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, 06269-1063, USA

Metin Coşgel

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Metin Coşgel .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Coşgel, M. The state, religion, and freedom: a review essay of Persecution & toleration . Rev Austrian Econ 35 , 257–266 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11138-020-00533-6

Download citation

Accepted : 15 November 2020

Published : 20 November 2020

Issue Date : June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11138-020-00533-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Persecution and toleration

- Religious freedom

- State capacity

- Political legitimacy

- Legal order

- Identity rules

- General laws

- Heterodox practices

JEL classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Arguments for the Human Right to Religious Freedom

Arguments for the human right to religious freedom 1.

John Courtney Murray, S.J.

The following article is the closest that the later Murray came to a "purely natural law," philosophical argument. As mentioned in the general introduction, Murray began his 1945 philosophical argument with "essential definitions" of key terms that he though relevant to that debate—terms such as "conscience," "law," "state," and "God." Here he is defining the term "human dignity" that serves as the philosophical foundation for the right to religious freedom. In doing so, however, he is not delineating a timeless essence. Rather, he is making explicit a notion that, he contends, has emerged within Western societies. After the mid-1950s, natural law had become for Murray a developing tradition of ideas, commitments, and procedures that course through the social and political thought of a secular society that is continuously on the move.

In terms of the structure Murray established in "The Problem of Religious Freedom," this complex, secular notion of human dignity "converges" with the church's own, theologically-based judgments concerning the church's place in human history and its own freedom. That the secular society's and the church's judgments ought to converge is of course based in Murray's notion of Gelasian dualism (and concordia), as is his judgment that the church ought to affirm and defend human dignity as a social good. Since Murray is here simply trying to tone up Dignitatis's philosophical argument, the theological presuppositions of his earlier arguments recede into the background.

Here Murray strengthened his conciliar argument by adjusting the relative positions of the various principles that he had clarified in those conciliar discussions. The reader might especially note the positioning of the principle "as much freedom as possible" in this article, in contrast to its place in "Problem."

Yet a question remains: Is this what Western societies affirm when they proclaim commitments to human dignity? For Murray, the notion is intrinsically social and historical. It involves a view of the human person as constantly active within, and possessing responsibilities toward, the societies in which they live. Some criticisms of Western individualism do not find such a social notion of the human person at the heart of the Western experiment, while others find sociality there, but also a reticence to talk about those implied social commitments. Murray's understanding of human dignity also includes an intrinsic drive toward all that the human mind and heart can question, including the reality of God. Again, some criticisms of Western culture find at its core a constraining materialism. At the least, Murray's exposition perhaps can demonstrate that our alternatives are not simply between individualistic isolation and communitarian emersion, materialistic constriction and spiritualistic escapism. It might be possible to develop an understanding of the human person that preserves both the strong sense of personal integrity and worth of the individualist traditions, the social interdependence of more communitarian traditions, and a strong concern for material existence that is involved in commitments to social justice—Editor.

The Vatican Declaration " Dignitatis humanae personae " affirmed that the human person has a right to religious freedom. It showed that the concept of religious freedom is clear, distinct, and technically exact regarding both its ground and its object, and adequately developed concerning what it embraces. First I will reiterate what the council meant and what generally is meant by religious freedom. Then I will address the more difficult question of how to construct the argument—whether derived from reason or from revelation—that will give a solid foundation to what the Declaration affirms. For nearly four years the conciliar Fathers and experts vigorously debated this justification, eventually completing the brief argument found in the Declaration (n.2,3). Even so, it is fair to say that this argument has pleased or pleases no one in all respects.

We can legitimately debate how better to construct the argument. For the Council's teaching authority falls upon what it affirmed, not upon the reasons it adduced for its affirmation. The Council did not intend that the Declaration establish an apodictic proof. The Declaration was merely to outline certain arguments, mainly to demonstrate that the affirmation of religious freedom is doctrinal. 2 The church's affirmation is based upon arguments drawn both from human reason and from Christian sources. Please allow me, then, what you have allowed others: to discuss this whole matter briefly.

I. Civil Religious Freedom

To begin with, it will be useful carefully to delimit what we must argue. This will not be difficult if we keep in mind that the concept of religious freedom includes a two-fold immunity from coercion.

First, in the sphere of religion no one is to be compelled to act against his conscience. Nowadays this principle is one upon which all persons of judgement agree, unshakably. Enough, then, to recall that for us Christians this principle derives its strongest argument from the necessary freedom of the act of Christian faith, a doctrine licitly and necessarily extended to the profession of every religion.

Second, in the sphere of religion no one is to be impeded from acting according to his conscience—in public or in private, alone or in association with others. It is around this second immunity that the conciliar debate turned. This second immunity had long been a historical problem; it remains a theoretical or doctrinal problem. It will help to clarify the problem.

Discussion of the human right to religious freedom calls for further inquiry into the foundations of the juridical relationship among human beings in civil society. The concept of a juridical relationship properly includes the notion of a correspondence between rights and duties. To one person's right there is a corresponding duty incumbent on others to do or give or omit something. In our case, the human person demands by right the omission of all coercive action impeding a person or a community from acting according to its conscience in religious matters. Therefore, the affirmation that every person has a right to such immunity is simultaneously an affirmation that no other person or power in society has a right to use coercion. On the contrary all others are duty- bound to refrain from coercive action. The second immunity, then, requires a compelling argument that no other person can raise, as a right or duty, a valid claim against that immunity or, put positively, that all are obliged to respect that immunity. The whole matter hinges on this argument for the juridical actuality of the second immunity.

To clarify this point, let us suppose that there does exist in human society a power that possesses the right to prohibit religious practice. Such a power could only be the public power (the state). Certainly a right of this kind could not be possessed by any private person or intermediate social group. One could argue—indeed, many have so argued—that the public power does possess such a right because of its duty toward the good of society and because it has a monopoly on coercive power that it must exercise for the good of society either by means of legislation or of administrative action.

To establish, then, that the human person enjoys a right to full religious freedom, one must first establish that the public power has no right to restrict religious freedom but has rather the duty to acknowledge and protect it.

Such being the case, clearly our inquiry, although of its nature ethico-juridical, is nevertheless finally and formally political, or what is called constitutional. By this I mean that it deals with the duties and rights of the public power—their nature, their extent, and their limits.

The classic difficulty in this matter is well known. It begins in the human person's obligation to act intelligently, i.e., according to his conscience. Yet it sometimes can and often does happen that someone who acts according to his conscience can act contrary to the objective order of truth—for example, by practicing a form of public worship not wholly in agreement with the divine ordinance or by disseminating religious opinions not in conformity with divine revelation. Surely spreading religious errors or practicing false forms of worship is per se evil in the moral order. About this there is no doubt. But our inquiry is not about the moral but about the juridical order. Does the public power have the duty and the right to repress opinions, practices, religious rites because they are erroneous and dangerous to the common good?

The Vatican Council's Declaration denies that such duty and such right fall within the competence of the public power. Yet we still must ask: On what justifying argument does this denial rest? Why may the limitation placed on the public power in matters of religion be considered just and legitimate? Thus is the state of our question. I will now evaluate the various arguments that were put forward to confirm the person's right to freedom in religious matters.

II. Arguments for Religious Freedom

First we must note that the doctrine of the Declaration is today supported by the sense and near unanimous consent of the human race. This is also intimated at the very beginning of the Declaration. The Declaration also suggests that this consent does not rely upon the laicist ideology so widespread in the nineteenth century but upon the increasingly worldwide consciousness of the dignity of the human person. It relies, therefore, upon an objective truth manifested to the people of our time by their own consciousness. Before adducing other arguments, then, the presupposition obtains and prevails that the teaching of the Declaration is also true. Securus enim iudicat orbis terrarum . 3

From this it follows that the Council's sole purpose in adducing the argument in favor of the right to religious freedom is to clarify and strengthen under the light of both reason and Christian revelation the more of less confused contemporary consciousness of human dignity.

A: From Conscience

The first conciliar attempt to do so was laid out in the arguments of the first and second schemata. 4 The basis of that argument was the moral principle that in religious matters man in held bound to follow his conscience even if erroneous. From this moral principle the schema deduced, as if immediately, the moral-juridical principle that to man is due the right to be free in society to follow his conscience.

This moral argument if correctly expounded has its force. But ultimately it is defective because unable to demonstrate what, in line with our statements above, has to be demonstrated.

The moral principle is entirely valid that man is duty-bound always to follow his conscience. From this follows the moral-juridical principle that man has the right to fulfill his duty. No difficulty arises if the conscience in question is right and true. This is evident. But if the conscience in question is right but erroneous, it cannot give rise to a juridical relationship between persons. From one human being's erroneous conscience no duty follows for others to act or perform or omit anything. Some might insist that the first two schemata additionally presuppose that the public power lacks any right to prevent human beings in society from acting according to erroneous consciences. Perhaps it does, even though this is not immediately apparent from the text. Even so, the schemata's argument failed to demonstrate why the public power lacks this right.

This being the case, the argument fails to support that immunity upon which our whole inquiry hinges. Hence it is not surprising that the Council's third schema—entitled "corrected text"— abandoned this line of argument that would ground the right to religious freedom in the dictates of conscience. From the third schema down to the promulgation of the Declaration, the foundation for the right to religious freedom is placed in the dignity of the human person. Rightly and wisely.

I shall leave aside the justifying arguments found in the subsequent schemata and come at once to the final, definitive text. The text sets forth two main arguments and, to give completeness to the doctrine, a third additional argument based upon the faith. 5

B. From the Obligation to Search After the Truth

In keeping with the wishes of many council Fathers, the first argument attempts ontologically to ground religious freedom in the fact that all men "are impelled by their nature and are bound besides by a moral obligation to seek the truth, especially truth regarding religion. They are also bound, once they have learned the truth, to adhere to it and to regulate their whole lives according to its demands" (no.2). From this moral obligation the argument next deduces the human right to immunity from external coercion in fulfilling his obligations. The further assertion is made that "the exercise (of this right) cannot be impeded if the just public order is preserved."

Obviously this argument aims to vindicate the whole concept of religious freedom insofar as it imports the double immunity from coercion. What are we to think of this argument?

The argument is valid and on target. Undeniably the demand for freedom has its basis in man's intellectual nature, in the human capacity to seek, to embrace, and to manifest by his way of life the truth to which he is ordered. In no other way can he perform his duty toward truth than by his personal assent and free deliberation. What is more, from this single consideration it is already clear that no one is to be forced to act against his conscience or against the demands of the truth that he has in fact found, or at least thinks that he has found. If so forced, he would be acting against his intellectual nature itself.

Yet we may still ask whether this demand for freedom, which flows from the source just mentioned, has enough power to establish a true right in keeping with which no one is to be impeded from acting according to his conscience in religious matters. Put differently: Are man's natural and moral links to truth powerful enough to engender a political relationship between the human person and the public power so that the latter is duty-bound not to prevent the person from acting according to his conscience—whether the person acts alone or in association with others? It seems not.

Man is certainly impelled by his nature, and is obliged morally, to seek the truth so that he might conform his life to the truth, once found. Yet quite a few, either after searching for religious truth or not searching for it, actually cling to more or less false opinions that they wish to put into practice publicly and to disseminate in society. To highlight again the point upon which our investigation hinges, let us imagine public powers speaking to these erring people as follows:

"We acknowledge and deeply respect the impulse to seek truth implanted in human nature. We acknowledge, too, your moral obligation to conform your life to truth's demands. But, sorry to say, we judge you to be in error. For in the sphere of religion we possess objective truth. More than that, in this society we represent the common good as well as religious truth—in fact religious truth is an integral part of the common good. In your private and in your family life, therefore, you may lawfully act according to your errors. However, we acknowledge no duty on our part to refrain from coercion in your regard when in the public life of society, which is our concern, you set about introducing your false forms of worship or spreading your errors. Continue, then, your search for truth until you find it—we possess it—so that you may be able to act in public in keeping with it."

Is this proclamation imaginary? Hardly! Time and again over the centuries public powers have issued similar statements. And what answer can the poor people make who are thus judged to be living in error? None, certainly, if we stay within the principles laid down in the Declaration's first argument. For we can grant the premiss of those principles: that those in error have an obligation to seek the truth in order to learn it and act in keeping with it. But we deny that from those principles the conclusion follows that those in error have the right not to be impeded from acting in public according to their consciences. It seems correct to deny this conclusion, since it appears to extend beyond its premisses.

Assuredly those judged to be misguided would like to object that the public power has no right to issue judgements about objective truth in the religious sphere, that even less has it the right to transform those judgements into coercive legislation, thereby preventing its citizens from acting according to their consciences. This is as valid an objection as can be. But I ask: Does its validity proceed from the ontological basis of religious freedom as the Declaration claims and conceives that it does? It seems not.

For it may be said, and some at times have so claimed, that the right of civil power to repress false forms of worship or religious errors is compatible with man's moral obligation to seek the truth in order to act according to it. For such repression does not in the least prevent the quest for truth, nor does it prevent acting according to the truth. What it does prevent are public activities that proceed from a basis in error and that thus cause harm to the public good. This opinion is not to be scorned. It has even been widely received at times within the Church itself.

Admittedly it was mainly pastoral considerations that led the Fathers to accept this first argument in the Declaration, the argument that situates the ontological roots of religious freedom in the obligation to seek the truth. Some Fathers feared the establishment of a kind of separation between truth and freedom, or more exactly, a separation between the order of truth and the juridical order that equips man with right against others. Of course this was an entirely legitimate concern. Still, the speculative question remains: Is it correct to place the ontological ground for religious freedom in man's natural and moral relationships to truth? On this point doubt may be allowed.

C. From the Person's Social Nature

The same pastoral uneasiness apparently controls the second major argument in the Declaration. This argument begins with the divine law to which every human being is subject and in which his nature makes him a participant. From this premise the argument at once concludes to man's moral obligation to investigate what the precepts of the divine law might be. The point is made that this investigation ought to be conducted in a social manner. The argument then lays down another moral principle—that man perceives the dictates of the divine law through the mediation of his conscience, which he is therefore always bound to follow. After positing these moral principles, the argument proceeds to a conclusion that is juridical: that not surprisingly man has a right to the two immunities that form the object of the right to religious freedom.

I acknowledge the value of this argument, provided the following distinction is made that always must be made. Indisputably the argument validly shows that no one is to be forced to act against his conscience, for by so acting a person would be doing wrong. But the second question recurs. Does it follow from this argument that no one is to be prevented from acting in public according to his conscience? To establish immunity from this kind of coercion—and this is specific to religious freedom in its modern meaning—the argument appeals to the necessary connection between internal acts of religion and those outward acts by which, in keeping with his social nature, a human being displays his religious convictions in a public way. Given this connection, the argument runs as follows: A purely human power cannot forbid internal acts; it is therefore equally powerless to forbid external acts.

But does not the fallacy of begging the question somehow lurk in this argument? It supposes that in society no power exists with authority reaching far enough to warrant its legitimately forbidding public acts of religion, even acts that transgress objective truth or divine law or even the common good. This must be established; it is the very heart of the matter under discussion. It is not proved by stating that persons are morally obliged to obey divine law as known by them through the mediation of their consciences. Nor is it proved by stating that human nature is social and requires that people profess their religion in a public and communitarian manner.

D. From the Limits of Public Power

Finally, there remains the third argument of the Declaration. It does concern the limits of the public power. This argument is introduced with the word Praeterea ["Furthermore"]. This suggests that the argument is added as a complement to the argument so far presented, a complement to an argument that is presumed in itself sufficient to justify the human right to religious freedom in its double sense.

But if the state of the question about this human right is examined thoroughly, it is at once evident that this political argument is of primary importance. Without it any other argument would not sufficiently settle the question. For the very question concerns the limits of public power in religious matters.

The Declaration makes the felicitous assertion that public power "must be said to exceed its limits if it should presume to direct or to impede religious acts" (n.3). Felicitous, I repeat, and altogether true. But it is a simple assertion for whose truth no reasons are brought forward. May I be permitted, as long as time allows, to develop this political argument. I proceed in outline form, schematically, by enumerating the principles without further development. The intention of the argument I offer is the same as that prefixed to the Declaration: "to develop the teaching of recent Popes about the inviolable rights of the human person and about the juridical ordering of society" (n.1).

The argument begins properly from a first principle: Every human person is endowed with a dignity that surpasses the rest of creatures because the human person is independent [in charge of himself, autonomous]. The primordial demand of that dignity, then, is that man acts by his own counsel and purpose, using and enjoying his freedom, moved, not by external coercion, but internally by the risk of his whole existence. In a word, human dignity consists formally in the person's responsibility for himself and, what is more, for his world. So great is his dignity that not even God can take it away—by taking upon Himself or unto Himself the responsibility for his life and for his fate. This in the Christian tradition, especially from the Greek Fathers on, is the dignity of the person conceived, fashioned in the image of God. The person's intellectual nature is a prior condition, the absence of which would render his assumption of responsibility impossible. Formally, however, human dignity consists in bearing this responsibility.

Now, from the first, ontological principle (the dignity or the human person), there follows a second principle, the social principle, which Pope Pius XII and later John XXIII began to develop somewhat fully. The social principle states that the human person is the subject, foundation, and end of the entire social life. 6

For our purpose, the chief force of the social principle lies in its establishing an indissoluble connection between the moral and the juridical orders. This connection must not be conceived in some abstract manner but in a wholly concrete way. For the connection is the human person itself, really existing, in the presence of its God and Lord, in association with others in this historic world, but in such wise that it transcends by reason of its end both society and the whole world. The human person exists in God's presence as a moral subject bound by duties toward the moral order and toward the historical order of salvation established by Jesus Christ. The human person exists with others in society as a moral-juridical subject furnished with rights that flow directly and altogether from human nature, never to be alienated from that nature. The juridical order cannot be sundered from the moral order, any more than the human person can be halved.

Evidently, in this subordinate place we can and ought to collect and situate those things that the Declaration said so beautifully about the natural human impulse to seek truth and about the person's moral obligation to live according to the truth once found. They do illustrate the first ontological principle and the second social principle. 7

Now, from the first and the second principles, the ontological and the social, taken together, there follows a third principle, the so-called principle of the free society. This principle affirms that man in society must be accorded as much freedom as possible, and that that freedom is not to be restricted unless and insofar as is necessary. By necessary I mean the restraint needed to preserve society's very existence or—to use the concept and terms of the Declaration itself—necessary for preserving the public order in its juridical, political, and moral aspects

Parallel with the third principle, a fourth issues from taking the first two, the ontological and the social, together. This principle is juridical and maintains that all citizens enjoy juridical equality in society. 8 This principle rests upon the truth that all persons are peers in natural dignity and that every human being is equally the subject, foundation, and end of human society.

Finally, there follows a fifth principle, the political principle. It is admirably expressed in the following words of Pius XII, later quoted by John XXIII. "To protect the inviolable rights proper to human beings and to ensure that everyone may discharge his duties with greater facility—this is the paramount duty of every public power." 9 This constitutes for the public power its first and principal concern for the common good—the effective protection of the human person and its dignity. This definition of the paramount function of public power rests clearly upon the first four principles.

Further, all five principles cohere with one another in such a way that they form a kind of vision of the human person in society and of society itself, of the juridical ordering of society and of the common good considered in its most fundamental dimensions, and finally of the duties of the public power toward persons and society. Upon this vision, which recent pontiffs have newly elaborated while working within the tradition, rests the whole doctrine of the Vatican Declaration on Religious Freedom. In other words, the five principles just enumerated taken together finally bring our whole investigation to a point of decision. For they are sufficient to constitute that relationship between the human person and the public juridical power. Together they fully characterize the notion of religious freedom.

They are also sufficient to confirm the other human and civil freedoms with which John XXIII dealt in an eminent manner in his Encyclical Pacem in Terris . Along with these freedoms religious freedom constitutes an order of freedoms in society. Religious freedom cannot be discussed apart from discussion of this whole body of freedoms. All human freedoms stand or fall together—a fact that secular experience has made clear enough.

This said, it is not difficult to construct an argument for the human right to religious freedom.

III. A needed Argument

The first thing to note is that the dignity and the freedom of the human person should receive primary attention since they pertain to the goods that are proper to the human spirit. As for these goods, the first of which is the good of religion, the most important and urgent demand is for freedom. For human dignity demands that in making this fundamental religious option and in carrying it out through every type of religious action, whether private or public, in all these aspects a person should act by his own deliberation and purpose, enjoying immunity from all external coercion so that in the presence of God he takes responsibility on himself alone for his religious decisions and acts. This demand of both freedom and responsibility is the ultimate ontological ground of religious freedom as it is likewise the ground of the other human freedoms.

Now, this demand is grounded upon the very existence of the human person, or, if one prefers, in the objective truth about the human person. Therefore it is revealed as a juridical value in society, so that it can impose upon the public power the duty to refrain from keeping the human person from acting in religious matters according to his dignity. For the public power is bound to acknowledge and to fulfill this duty by reason of its principal function, the protection of the dignity of the person. Once this duty is demonstrated and acknowledged, the immunity from coercion in religious matters demanded by human dignity becomes actually the object of a right. For the juridical actuality of a right is established wherever a corresponding duty is established and is acknowledged, once the validity of the ground for a right is assured and recognized.

Furthermore, the above mentioned principle of a free society—taken together with the principle of the juridical equality of all citizens—likewise sets the outer limits on just how far the public power must refrain from preventing someone from acting according to his conscience. The free exercise of religion in society ought not be restricted save insofar as it is necessary, that is, save when a public act ceases to be an exercise of religion because proven to be a crime against public order.

The following considerations will clarify this. The foundation of human society lies in the truth about the human person, or in its dignity, that is, in its demand for responsible freedom. That which in justice is preeminently owed to the person is freedom—as much freedom as possible—in order that society thus may be born toward its goals, which are those of the human person itself, by the strength and energies of persons in society bound together with one another by love. Truth and justice, therefore, and love itself demand that the practice of freedom in society be kept vigorous, especially with respect to the goods belonging to the human spirit and so much the more with respect to religion. Now this demand for freedom, following as it does from the objective truth of the person in society and from justice itself, naturally engenders the juridical relationship between the person and the public power. The public power is duty-bound to acknowledge the truth about the person, to protect and advance the person, and to render the justice owed the person.

Again, from this follows the conclusion that no one is to be prevented in the matter of religion from acting according to the demands of his dignity or according to his inmost religious convictions. Nor does this immunity cease except where just demands of public order are proven to have the urgency of a higher force.

Quod erat demonstandum. Or rather, this argument from the five principles mentioned is sufficient; nothing else is required.

IV. The Question of a Theological Argument

Of course there remains the argument for religious freedom as drawn from Christian revelation, but this is a lengthy question and my discussion has already been too long.

Suffice it to say that the line of argument that the Declaration follows is entirely valid and sound. It embraces three major statements. (1) The human person's right to religious freedom cannot itself be proven from Holy Scripture, nor from Christian revelation. (2) Yet the foundation of this right, the dignity of the human person, has ampler and more brilliant confirmation in Holy Scripture than can be drawn from human reason alone. (3) By a long historical evolution society has finally reached the notion of religious freedom as a human right. And a foundation and moving force of this ethical and political development has been Christian doctrine itself—I use "Christian" in its proper sense—on the subject of human dignity, doctrine illuminated by the example of the Lord Jesus.

Difficult and important questions remain. The primary one concerns the relationship between the Christian freedom proclaimed in Holy Scripture, especially by St. Paul, and the religious freedom we have been speaking of, to which our contemporaries lay claim. 10 On this question no consensus exists. According to some, these two freedoms are so different from their inception that only a limited harmony can exist between them. According to others, of whom I am one, in the very notion of Christian and gospel freedom—or, better—in free Christian existence itself—a demand is given for religious freedom in society. To demonstrate this is no mean task. Add to this the difficult historical question, as yet not investigated: Why has humanity had to travel so long a journey on so tortuous a course to reach at last a consciousness of its dignity and to bring to fulfillment in civil society all that that dignity demands?

Evidently these question belong to the ecumenical order. Equally evident and pressing is the need for us to enter into conversation with our separated brothers and even with our non-believing brothers. These have contributed much and still contribute toward the establishment and preservation in society of the full practice of freedom, including also religious freedom.

( 1 )This was delivered as a talk on September 19, 1966 and published in Latin as "De argumentis pro iure hominis ad libertatem religiosam." In Acta Congressus Internationalis de Theologia Concilii Vaticani II , edited by A. Schoenmetzer, 562-73. Rom, Vatikan, 1968.

( 2 )i.e., that it is not simply based in expediency—Ed.

( 3 )"The whole world concurs in this judgement," probably an allusion to Augustine, Contra ep. Parm., II, 10, 20. Parts of this argument find a parallel in 1966b: "The Declaration on Religious Freedom." In Vatican II: An Interfaith Appraisal , edited by John H. Miller, article, pp. 565-76, and discussion, pp. 577-85 (Notre Dame: Association Press, 1966). Certain points, such as the international political and ecclesiological support given to religious freedom, are more fully spelled out in that latter article—Ed.

( 4 )For a discussion of the various texts that preceded Dignitatis, the introduction to "The Problem" in this volume. By Murray's count there were five such texts, the third and fourth were of Murray's creation—Ed.

( 5 )The remainder of the article presents actually three philosophical arguments and a fourth based on faith. As we will see, Murray was unhappy with the first two "main arguments." (They both suggest an individualism (that often cloaks itself in abstraction) and an a-historicity that he found in the "conscience" argument.) He will here present a third argument that he considers core to the church's affirmation and to contemporary affirmations of human dignity. This third line had been primary in the third and fourth drafts of the Declaration (the ones Murray wrote), and had been reduced to an ancillary position in subsequent drafts and in the final document.

Since Murray's own numbering is off, I felt free, by way of headings, to grant to the "conscience" argument the status of first in a line of arguments. In fact, the language of the "rights of conscience" argument was not limited to the first two drafts. There remains some residual "rights of conscience" terminology in the Declaration, a fact used by some who want to argue that the Council did not advance beyond the "conscience" argument—Ed.

( 6 )Cf. Pius XII, Nunt. radioph. 24 dec. 1944, in: A.A.S. 37 (1945) p. 12; Ioannes XXIII Litt. enc. " Pacem in terris , in A.A.S. 55 (1963) p. 263; Dz.-S 3968.

( 7 )By situating the drive for truth within the second, social pole of the human person, Murray apparently thinks that he has escaped the individualism and abstraction of the Declaration's main argument. Within that second pole, the argument must take account of the structures and forces that are active within historical societies as well as of the transcendental openness of the human person.—Ed.

( 8 )Just as the first two principles call up the individual/social aspects of human nature, similarly for Murray these third and fourth principles have individual/social references. The third points to the creative powers of persons and subgroups in society, while the fourth focuses on the largest social reality, the state. Murray has attempted to highlight the intrinsic social aspects of the human person throughout the various levels of this argument—Ed.

( 9 )Pius XII, Nunt. radioph . 1 iun. 1941, in: A.A.S. 33 (1941)p. 200; Ioannes XXIII "Pacem in terris." ed. cit., p. 274; Dz-S 3985.

( 10 )Elsewhere Murray spelled out a broader list of freedoms that must be reconciled:

The Declaration therefore does not undertake to present a full and complete theology of freedom. This would have been a far more ambitious task. It would have been necessary, I think, to develop four major themes: (1) the concept of Christian freedom—the freedom of the People of God—as a participation in the freedom of the Holy Spirit, the principal agent in the history of salvation, by whom the children of God are "led" (Rom. 8, 14) to the Father through the incarnate Son; (2) the concept of the freedom of the Church in her ministry, as a participation in the freedom of Christ himself, to whom all authority in heaven and on earth was given and who is present in his Church to the end of time (cf. Matt. 28, 18. 20); (3) the concept of Christian faith as man's free response to the divine call issued, on the Father's eternal and gracious initiative, through Christ, and heard by man in his heart where the Spirit speaks what he has himself heard (cf. John 16, 13-15); (4) the juridical concept of religious freedom as a human and civil right, founded on the native dignity of the human person who is made in the image of God and therefore enjoys, as his birthright, a participation in the freedom of God himself.

This would have been, I think, a far more satisfactory method of procedure, from the theological point of view. In particular, it would have been in conformity with the disposition of theologians today to view issues of natural law within the concrete context of the present historico-existential order of grace. Moreover, the doctrine presented would have been much richer in content (1966c: "The Declaration on Religious Freedom," p. 4)—Ed.

Catholic Education

Religious liberty essay contest.

- @USCCBCatholicEd

Witnesses to Freedom

USCCB Religious Liberty Essay Contest 2024

Share the story of a witness to freedom. Choose one person (or group, such as an organization or community) who is important in the story of freedom. Was there a key moment in the person’s life that bears witness to freedom? Or was it the life as a whole? Did the person articulate important concepts for religious freedom, and if so, what arguments did she or he make? Why is this person a witness to religious freedom? What lessons can we learn from this person’s witness?

Please include a bibliography. Any reference style is acceptable as long as it is consistent throughout the document. Essays should be no longer than 1,100 words .

The first-place essay will be published Our Sunday Visitor , and the author will be awarded a $2,000 scholarship.

Second place will receive a $1,000 scholarship, and third place will receive a $500 scholarship.

Submissions

Essays are due March 29, 2024 . Winners will be announced in May.

Please complete the consent form and include with submission .

Email submissions [email protected] .

See contest rules for details .

About OSV Institute

Our Sunday Visitor Institute seeks to Serve the Church by inspiring and encouraging innovative and effective Church-related programs and activities. Learn more at www.osvinstitute.com .

Past Winners

First place: Little Strokes Fell Great Oaks: The Story of the Littlest Witness , by Sofia Cornicelli

Second place: Joy at the Guillotine , by Cara Magliochetti

Third place: Saint Justin: Philosopher, Apologist, and Martyr , by Margaret Nornberg