Metaphysical Poetry – Capturing the Otherworldly in Verse

Sometimes a type of poetry is “of a certain time”, and that is the case with today’s point of focus: metaphysical poetry. So, what is metaphysical poetry then? This will be our question of focus today. We will have a look at the history of this form of poetry, some of the characteristics for which it has become known, some of the goals that it attempted to achieve, and a few examples of metaphysical poetry to help explain and explore the concept in greater depth. This article should be of help to those who want to know about metaphysical poetry but have not yet had the time to do so. If this describes your interest in metaphysical poetry, you have some learning to do!

Table of Contents

- 1 A Look at Metaphysical Poetry

- 2 A Summary of Metaphysical Poetry

- 3 The History of Metaphysical Poetry

- 4 The Characteristics of Metaphysical Poetry

- 5 The Goals of Metaphysical Poetry

- 6.1 The Collar (1633) by George Herbert

- 6.2 The Flea (1633) by John Donne

- 6.3 To His Coy Mistress (1681) by Andrew Marvell

- 7.1 What Is Metaphysical Poetry?

- 7.2 Where Did Metaphysical Poetry Originate?

- 7.3 What Are the Characteristics of Metaphysical Poetry?

- 7.4 Does Metaphysical Poetry Still Exist?

- 7.5 What Are Some Famous Examples of Metaphysical Poetry?

A Look at Metaphysical Poetry

Back when I used to teach high school, and even when I provided educational material to university students, I would sometimes need to explain that certain forms of literature and theory come from a very specific time and place. That is the case with metaphysical poetry. Sometimes, something can only really be understood based on its particular goals during a particular period. That isn’t to say that metaphysical poetry cannot be enjoyed without also knowing your history, but it can perhaps be better enjoyed when we understand where it comes from. This will be part of our focus today.

A Summary of Metaphysical Poetry

There are many different types of poetry out there, and some of them are marked by very specific definitions. This is generally the case with metaphysical poetry. So, what is metaphysical poetry? We’ll be answering that in-depth throughout this article, but here’s a quick look for those who may need it:

- Metaphysical poetry is an intellectually complex form of poetry. Some of the principal characteristics of metaphysical poetry lie in its use of more intellectually complex ideas that are portrayed through elaborate forms. This form of poetry is known for tackling tough and interesting issues.

- Metaphysical poetry originated in 17 th century England. This form of poetry attained its name retrospectively. The metaphysical poets did not call themselves this, and it was instead applied by later thinkers to help describe this particular trend in 17 th -century poetry.

- Metaphysical poetry still exists in some form. While the actual movement that came to be known as metaphysical poetry has come to an end, the influence of this form would have an effect on later writers. While we could argue that later writers who used a similar style to the metaphysical poets are not writing true metaphysical poetry, we could also argue in the other direction.

This has been a summary of metaphysical poetry, which, in my experience as a literature teacher, is something that can be a very useful thing. Many students can easily forget certain aspects of a topic.

A brief and bullet-pointed list can be of great help to those who need a quick leg up.

The History of Metaphysical Poetry

The beginnings of metaphysical poetry emerged in the 17 th century in England. However, these writers did not self-identify as metaphysical poets. Instead, this label came several decades later while other writers were attempting to define this earlier period in time. Many trends in literature, and other areas, can only truly be seen in retrospect.

Some of the poets who were identified as the primary metaphysical poets included figures such as John Donne, Andrew Marvell, and George Herbert. There were several others, but the list of writers who have been labeled as metaphysical poets is a relatively short one. However, this does present us with a question: Does metaphysical poetry still exist today?

The answer is both a yes and a no. You see, these poets were labeled as a historical group, but they would go on to influence many others who made use of ideas and techniques that the metaphysical poets developed. However, this does not necessarily make those people metaphysical poets but rather those who were simply influenced by them. This can become a difficult thing to determine for certain, but it definitely is an interesting question to ponder.

The Characteristics of Metaphysical Poetry

The principal characteristics of metaphysical poetry have to do with its examination of philosophical ideas and concepts. However, while this is one of the central ideas, it is far from the only idea that is often explored in this type of poetry. In addition to the use of philosophical ponderings, metaphysical poetry also made use of more elaborated forms of figurative language, paradoxical structures, strange imagery, and a more intellectual overall focus. Interestingly, many examples of metaphysical poetry also made use of more colloquial language and expression, including the use of more relaxed forms of meter. This means that while metaphysical poetry was noted for its use of philosophical ideas, it also wrapped those ideas in more understandable language.

This is an interesting choice as many other intellectual writers, such as T.S. Eliot, would entirely ignore the idea of ease of understanding in favor of immense complexity.

The Goals of Metaphysical Poetry

What was the point of metaphysical poetry in the first place? Well, it must be remembered that this form of poetry was not defined during its major period. Instead, it would only come to be defined by those who lived decades later. However, the poets who came to be seen as the metaphysical poets did have a number of goals that they explored in their poetry.

Some of the more common of these goals was the exploration of philosophical ideas. They would often try to understand aspects of the world, to focus on spirituality, science, and morality. They explored concepts such as free will and the very nature of the world as a whole. This is also why they came to be known as the metaphysical poets. Metaphysics is a branch of philosophy that focuses on understanding reality itself and is often some of the earliest philosophy that is taught because it serves as a backbone against which other concepts can be later explored.

During my days as an English and literature teacher, I would often inject these kinds of philosophical inquiries into my teaching. We may think that younger people do not consider philosophical questions, but this is not the case. Many people want to explore and discuss these kinds of ideas, but there is seldom an avenue through which they can be allowed to do so. Poetry provides such an avenue. We cannot simply look at poetry from a formal perspective and see how it uses words, symbols, and structure, we also need to look at the ideas that it is presenting to us.

This is what metaphysical poetry allows us to do. Well, that and the use of certain formal elements. While metaphysical poetry was used to explore these kinds of philosophical ideas, it was also there to use figurative language in innovative ways, to alter the way poetic structure was used, and so on.

Many different aspects of metaphysical poetry are worth discussing.

Examples of Metaphysical Poetry

There are quite a number of examples of metaphysical poetry in the world, but we’ll only be having a look at three of them. These poems represent some of the most famous examples of metaphysical poetry from three of the figures who are seen as integral to the movement as a whole. Hopefully, this should serve as a way to aid in answering the question: “What is metaphysical poetry?” If you’d like an answer to that, let’s have a look at some of these particular instances.

The Collar (1633) by George Herbert

The Collar is a famous instance of metaphysical poetry because it examines ideas to do with spirituality, freedom, and pleasure. It explores the constraints that are placed upon those in religious positions and the desires that come with wishing for a guilt-free life in which pleasure is celebrated rather than rejected. This is a good instance of metaphysical poetry because it makes use of an extended metaphor, uses more abstract themes, and is written in a more dramatic monologue style.

This poem has come to be seen as one of the best-known instances of metaphysical poetry, and the ideas that it explores are indicative of the poetic variety as a whole.

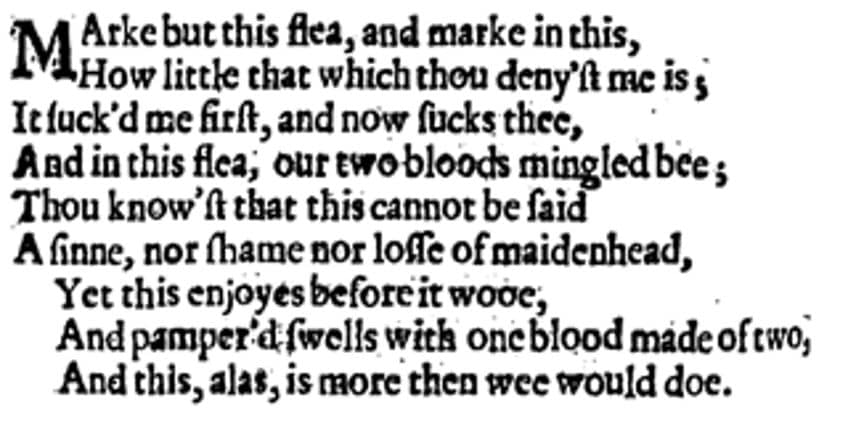

The Flea (1633) by John Donne

The Flea is a poem about sex. This is one of the more common areas that metaphysical poetry would often explore, and the last poem on this list is also an instance of this particular topic. In this poem, the poet uses the metaphor of a flea to show that the drinking of blood is something natural to the flea just as sex is something natural to the human. The use of an extended metaphor, candid explorations of sexual themes, and a wittier delivery are indicative of the kinds of work for which the metaphysical poets became so well known.

This is another of the metaphysical poems that has become a standout example of the form.

To His Coy Mistress (1681) by Andrew Marvell

To His Coy Mistress is not only one of the best-known metaphysical poems, but also a famous carpe diem poem. This means that the poem is all about seizing the day and living as if every day is potentially your last. In this particular case, like with many metaphysical poems, the act of seizing the day comes in the form of sexual pleasure. The speaker tries to convince someone to have sex because we’re all going to die eventually anyway, and wouldn’t it have been a waste to maintain chastity when there was so much pleasure to be had? This is a common theme explored in many examples of metaphysical poetry.

In this article on metaphysical poetry, we have looked at the definition of this concept as well as the history of the form, some of its characteristics and goals, and a handful of examples of metaphysical poetry. This should be beneficial to anyone who wants to learn more about the time of the metaphysical poets and the kinds of work that they produced. Hopefully, this has managed to help those with these very same desires. However, to truly experience metaphysical poetry, you should read more examples of this form.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is metaphysical poetry.

When it comes to an understanding of metaphysical poetry, we can somewhat see the idea reflected in the name itself. This is a form of poetry that focuses on intellectual content that uses elaborate language, complex structures, and often strange imagery. The label was applied more retrospectively to several writers.

Where Did Metaphysical Poetry Originate?

The origins of metaphysical poetry can be traced to England in the 17 th century. This term was used later to describe several poets who were not connected to one another yet had similar goals in their poetry. The poets labeled as metaphysical poets did not use this term to describe themselves.

What Are the Characteristics of Metaphysical Poetry?

Some of the standard features of metaphysical poetry lay in the use of more intellectual topics, elaborate forms of figurative language, highly complex forms and ideas, and so on. The name of this poetic form reflects the more philosophical inclinations of the poets who have come to be seen as metaphysical poets.

Does Metaphysical Poetry Still Exist?

This poetic form still exists, but not in the way that it did in the 17 th century in England. Instead, modern writers have taken inspiration from traditional metaphysical poetry and made use of similar ideas and formal arrangements. So, one could also argue that modern writers who use these ideas are not actually true metaphysical poets.

What Are Some Famous Examples of Metaphysical Poetry?

There are several writers who came to be known as the metaphysical poets. Some of their best-known works include The Collar (1633) by George Herbert, The Flea (1633) by John Donne, and To His Coy Mistress (1681) by Andrew Marvell. However, there are more than only these that have been shown.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team .

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Metaphysical Poetry – Capturing the Otherworldly in Verse.” Art in Context. January 18, 2024. URL: https://artincontext.org/metaphysical-poetry/

van Huyssteen, J. (2024, 18 January). Metaphysical Poetry – Capturing the Otherworldly in Verse. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/metaphysical-poetry/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Metaphysical Poetry – Capturing the Otherworldly in Verse.” Art in Context , January 18, 2024. https://artincontext.org/metaphysical-poetry/ .

Similar Posts

Poems About Dogs – Celebrating Man’s Best Friend

What Is a Villanelle Poem? – A Unique French Form of Prose

Sestina – Discover One of the Most Complex Poetic Forms

Poems About Summer – Capturing the Spirit of Summer in Verse

Apostrophe Poetry – The Art of Referencing an Absent Person

Poems About Growing Up – Navigating Life Through Poetry

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

John Donne: Poems

By john donne, john donne: poems essay questions.

How is Donne a Metaphysical poet?

Answer: Metaphysical poetry is distinguished by several unique features; unique metaphors, large and cosmic themes, absence of narrative, and philosophical ideas. Donne invented or originated many of these features in his poetry, and he was a master of this type. Metaphysical poetry may be lyrical in its tone, but its driving force is not necessarily the emotion of the poet. The striving to understand the world and ideas through strange and sometimes strained comparisons, esoteric and philosophical abstract ideas, and paradoxes and heterogenous parallels are the main differences between metaphysical and other types of poetry. These are common in Donne.

Choose a paradox in one of Donne's poems, and show how he puts two different ideas together to make a point or explain a idea.

Answer: A good example of this would be "The Flea," in which Donne describes the combination of his and his lady-love's blood in the flea's body like the union of the two lovers in marriage. How Donne could convert the bite of a pest into a love poem shows his ability to create new thoughts by combining difficult ideas with each other in unusual ways.

What is the basic point in "Death be not proud"?

Answer: The poet is mocking and belittling death. Although many people fear death, in the Christian tradition death is but an entrance to another, better world, so it is not to be feared. A good essay on this topic will show the various ways that Death is weak rather than powerful. It also might draw on "Meditation 17," explaining how Donne views death as a "translation" to a spiritual life.

How is Donne's life reflected in his poetry?

Answer: Several major events in Donne's life--his marriage, his conversion to Anglicanism, his wife's early death, illness, and his elevation to the Deanship of St. Paul's--can be seen in his poetry. In a more complicated way, one can draw inferences about which religious doctrines Donne may have been most fascinated by or skeptical about, considering carefully what he writes when treating various doctrines.

How is death treated in Donne's poetry?

Answer: Death is treated both as a reality of life and as an abstract concept. For Donne death is not necessarily somber but provides a transition moment--often a climax--denoting a change of state. In a superficial instance, "The Flea," the woman's nonchalant killing of the flea ostensibly ruins his argument for their physical intimacy, but the poet turns it into a proof that there is nothing to fear from loving him, just as the loss of the blood she has just obliterated is minimal. Most directly, Holy Sonnet 10, commonly referred to as "Death Be Not Proud," personifies Death as a powerless being who cannot survive past the Resurrection; ultimately, all people will reach their metaphysical states. Sickness brings thoughts of death and the lesson to prepare well for that transition, while anyone's death also provides such a lesson.

How does Donne treat physical and spiritual love in his works?

Answer: As a Metaphysical poet, Donne often uses physical love to evoke spiritual love. Indeed, this metaphysical conceit in much of the love poetry is not explicitly spelled out. To this end, Donne's poetry often suggests that the love the poet has for a particular beloved is greatly superior to others’ loves. Loving someone is as much a religious experience as a physical one, and the best love transcends mere physicality. In this kind of love, the lovers share something of a higher order than that of more mundane lovers. In “Love’s Infiniteness,” for example, Donne begins with a traditional-sounding love poem, but by this third stanza he has transformed the love between himself and his beloved into an abstract ideal which can be possessed absolutely and completely. His later poetry (after he joined the ministry) maintains some of the carnal playfulness from earlier poetry, but transforms it into a celebration of union between soul and soul or soul and God.

How is the individual connected with the whole of humanity in "Meditation 17"?

Answer: One of Donne's most famous statements, "No man is an island complete unto himself," directs readers to see every person as spiritually interrelated to every other. The death of one person affects every person: the effect is immediate upon the deceased's circle of friends, family, and acquaintances, it is felt in the community as the funeral bells ring, and it is experienced across humanity, which is that much less substantial with the loss of each person. Just as grains of sand erode from the shores of Europe and diminish the continent, each person's life and death affects the rest of humanity, considering that all are equal under God.

How does Donne use paradox to illustrate difficult metaphysical concepts?

Answer: Consider the closing couplet of Holy Sonnet 14:

Except you enthrall me, never shall be free, Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.

Just as one often finds in Christian scripture, Donne here sums up a key part of the relationship between individuals and God by using a paradox. The conflict raging within himself consists in the weakness of his reason in cleaving to his love of God rather than indulging his sinful desires. The Christian tradition expresses this problem as the need to die with respect to oneself and then to be reborn with respect to a new spiritual life. Donne similarly argues that the freedom of a Christian comes with binding oneself to God's commandments rather than one's own conflicting desires. Likewise, Christian purity comes from being invaded by God with force and plundering the body by removing its selfish desires.

Resolving this paradox is important for Donne's Christian metaphysics because it identifies a key problem of man: we live in a world so given over to evil that goodness and holiness are considered deviant by many. Donne uses paradoxical statements to get readers to think for themselves about how it could be true that there is radical value in being led by divine rationality rather than one's ungrounded motivations.

How did Donne represent his marriage in his poetry?

Answer: In "The Anniversary," Donne most directly addresses his marriage. When he considers his own and his wife's eventual deaths, he realizes that they should enjoy their living moments together while they are specifically together in this world. Later, their spiritual intimacy will be even more clearly secondary to their relationship toward God. Until then, Donne points out how unassailable their love is this side of the grave: here they are rulers, having one another as subjects, and no one can betray them save each other.

Donne's "Valediction" is a similar promise of future union, this time in the context of Donne's earthly voyage without his wife and his promised return. He chooses the metaphysical conceit of a compass to illustrate their relationship. The joint holding them both together at the top, drawing the circles, is God. His wife is the straight leg of the compass, providing the center-point around which he will travel and eventually return home, and he trusts her to stand firm, even while she leans in his direction wherever he might be.

Is Donne's poetry misogynistic? Does he get a pass because the metaphysical meaning of his poetry is more important than the literal meaning?

Answer: On the spiritual level, Donne puts himself in the place of the feminine, such as when he writes that he must be ravished in order to become pure (if we grant that that the poet is the same as the persona of the poem). Also on the spiritual level, the Church is coded as feminine both in traditional Christianity and in Donne's poetry. Thus, negative lines about infidelity are best understood as Donne's critique of the Church and of humans' propensity to sin and reject God.

Yet, should this interpretation permit the reader to ignore the literal meaning of a poem such as "Go and Catch a Falling Star," in which the poet states that one cannot find a single true woman--or else, if she is true, she will become false very soon? The spiritual meaning is still best; no human is sinless and fully true to God. The extreme hyperbole shows us not to take the conceit literally. Even so, Donne chose this conceit rather than a different one, and today's readers are easily led astray to think that Donne really intended a message about women's fickleness and infidelity.

In "A Valediction," Donne's attention to the steadfastness of his wife seems to express, perhaps, a concern for her fidelity while he is gone, even if his overt message is that he fully expects her to be true to him during that time. Maybe he thought his wife needed a reminder that he would certainly return, yet when one reads "The Anniversary" and "The Canonization," it is difficult to see Donne as anything less than a sincere, loving, trusting husband.

John Donne: Poems Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for John Donne: Poems is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

Summarize each stanza in two sentences in The Sunne Rising.

The poet asks the sun why it is shining in and disturbing him and his lover in bed. The sun should go away and do other things rather than disturb them, like wake up ants or rush late schoolboys to start their day. Lovers should be permitted to...

Batter My Heart

I, like an usurp'd town to another due

Treatment of Sun by the speaker in the poem The Sun Rising

Check out Analysis below:

https://www.gradesaver.com/donne-poems/study-guide/summary-the-sunne-rising

Study Guide for John Donne: Poems

John Donne: Poems study guide contains a biography of John Donne, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About John Donne: Poems

- John Donne: Poems Summary

- The Canonization Video

- Character List

Essays for John Donne: Poems

John Donne: Poems essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of John Donne's poetry.

- A Practical Criticism of John Donne's "Song" and "Go and Catch a Falling Star..."

- Donne's Worlds

- Jonathan Swift and John Donne: Balancing the Extremes of Renaissance England

- The Origin of Love: Donne's Theogony

- Sexism Within Donne's "Elegy 19"

Lesson Plan for John Donne: Poems

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to John Donne: Poems

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- John Donne: Poems Bibliography

Wikipedia Entries for John Donne: Poems

- Introduction

The Best Examples of Metaphysical Poetry in English Literature

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

What is ‘metaphysical poetry’, and who were the metaphysical poets? The term, which was popularised by Samuel Johnson in the eighteenth century, is often used to describe the work of poets including John Donne, George Herbert, and Andrew Marvell, although Johnson originally applied it to the poetry of Abraham Cowley.

Although the heyday of metaphysical poetry was the seventeenth century, the techniques employed by metaphysical poets continue to be used by modern and contemporary poets: see, for instance, the poetry of William Empson or the contemporary poems found on Calenture .

Below are some of the best and most illustrative examples of ‘metaphysical poetry’ from its golden age: poems which highlight the conceits, extended metaphors, wordplay, and paradoxes which many poets associated with the label ‘metaphysical’ embraced and utilised in their work.

1. John Donne, ‘ The Flea ’.

Mark but this flea, and mark in this, How little that which thou deniest me is; It sucked me first, and now sucks thee, And in this flea our two bloods mingled be; Thou know’st that this cannot be said A sin, nor shame, nor loss of maidenhead, Yet this enjoys before it woo, And pampered swells with one blood made of two, And this, alas, is more than we would do …

Like many of the best metaphysical poems, ‘The Flea’ uses an interesting and unusual conceit to make an argument – in this case, about the nature of physical love. Like Andrew Marvell’s ‘To His Coy Mistress’ (see below), ‘The Flea’ is essentially a seduction lyric.

Since this flea has sucked blood from both me and you, the poet says to his would-be mistress, our blood has already been mingled in the flea’s body; so why shouldn’t we mingle our bodies (and their fluids) in sexual intercourse? Of course, this rather crude paraphrase is a world away from the elegance and metaphorical originality of Donne’s poem with its extended metaphor …

2. John Donne, ‘ The Sun Rising ’.

Busy old fool, unruly sun, Why dost thou thus, Through windows, and through curtains call on us? Must to thy motions lovers’ seasons run? Saucy pedantic wretch, go chide Late school boys and sour prentices, Go tell court huntsmen that the king will ride, Call country ants to harvest offices, Love, all alike, no season knows nor clime, Nor hours, days, months, which are the rags of time …

This is one of Donne’s most celebrated poems, and it’s gloriously frank – it begins with Donne chastising the sun for peeping through the curtains, rousing him and his lover as they lie in bed together of a morning. Its ‘metaphysical’ quality is evident in Donne’s planetary imagery later in the poem: especially when he taunts the sun for being unlucky in love because its natural partner, the world, is already spoken for (because Donne and his beloved are the world) …

3. Anne Southwell, ‘An Elegie written by the Lady A: S: to the Countesse of London Derrye supposeinge hir to be dead by hir longe silence’.

Although all of the best-known metaphysical poets are men, it isn’t true that metaphysical poetry in the seventeenth century was solely the province of male poets. Anne Southwell (c. 1574-1636) proves this: born only a couple of years after Donne (probably), Southwell penned this metaphysical ‘elegy’ in which the Ptolemaic and Platonic versions of the universe are used as a way of understanding the power of prayer. This poem is not available elsewhere online, so we reproduce the first few lines below:

Since thou fayre soule, art warbleinge to a spheare, from whose resultances, theise quickned weere. since, thou hast layd that downy Couch aside of Lillyes, Violletts, and roseall pride, And lockt in marble chests, that Tapestrye that did adorne, the worlds Epitome, soe safe; that Doubt it selfe can neuer thinke, make fortune, or fate hath power, to breake a chinke. Since, thou for state, hath raisd thy state, soe farr, To a large heauen, from a vaute circular, because, the thronginge virtues, in thy brest, could not haue roome enough, in such a chest, what need hast thou? theise blotted Lines should tell, soules must againe take rise, from whence they fell.

4. George Herbert, ‘ The Collar ’.

I struck the board, and cry’d, No more. I will abroad. What? shall I ever sigh and pine? My lines and life are free; free as the rode, Loose as the winde, as large as store …

George Herbert (1593-1633) went to the grave without seeing any of his poetry into print; it was only because his friend, Nicholas Ferrar, thought they were worth salvaging that they were published at all.

In this poem, Herbert’s speaker seeks to reject belief in God, to cast off his ‘collar’ and be free. (The collar refers specifically to the ‘dog collar’ that denotes a Christian priest, with its connotations of ownership and restricted freedom, though it also suggests being bound or restricted more generally. Herbert, we should add, was a priest himself.) This central collar-metaphor signals this as one of Herbert’s greatest achievements in metaphysical poetry.

5. George Herbert, ‘ The Pulley ’.

When God at first made man, Having a glass of blessings standing by, ‘Let us,’ said he, ‘pour on him all we can. Let the world’s riches, which dispersèd lie, Contract into a span.’

So strength first made a way; Then beauty flowed, then wisdom, honour, pleasure. When almost all was out, God made a stay, Perceiving that, alone of all his treasure, Rest in the bottom lay …

Another of Herbert’s poems whose paradoxes and wordplay show him to be one of the greatest metaphysical poets. ‘The Pulley’ is a Creation poem which imagines God making man and bestowing all available attributes upon him – except for rest. Work is important so that man should worship the God who made Nature, rather than Nature itself.

We suppose one way of looking it is to say that God is advocating hard work as its own reward, and justifying having just one day of the week as a ‘day of rest’ on which to worship Him. Man should be ‘rich and weary’ – rich not only in a financial but in a moral and spiritual sense, too, we assume.

6. Henry Vaughan, ‘ The Retreat ’.

Happy those early days! when I Shined in my angel infancy. Before I understood this place Appointed for my second race, Or taught my soul to fancy aught But a white, celestial thought; When yet I had not walked above A mile or two from my first love, And looking back, at that short space, Could see a glimpse of His bright face …

The Welsh-born Vaughan (1621-95) is less famous than some of the other names on this list, but his work has similarly been labelled ‘metaphysical’. This poem is about the loss of heavenly innocence experienced during childhood, and a desire to regain this lost state of ‘angel infancy’, playing upon the double meaning of ‘retreat’ as both refuge and withdrawal.

7. Andrew Marvell, ‘ The Definition of Love ’.

My love is of a birth as rare As ’tis for object strange and high; It was begotten by Despair Upon Impossibility.

Magnanimous Despair alone Could show me so divine a thing Where feeble Hope could ne’er have flown, But vainly flapp’d its tinsel wing …

If we were going to try to pin down the term ‘metaphysical poetry’ to a clear example, we could do worse than this poem, from Andrew Marvell (1621-78). In ‘The Definition of Love’, Marvell announces that his love was born of despair – despair of knowing that the one he loved would never be his, because he and his beloved run on parallel lines which means they can never intersect and come together.

In other words, those who are best-suited to each other (if we interpret the ‘parallel’ image thus) are often kept apart (this poem has been interpreted as a coded reference to homosexuality: two men who love each other are ‘parallel’ in being the same gender, but seventeenth-century society decreed that they could never be together). A clever poem, but also a powerful one about frustrated love.

8. Andrew Marvell, ‘ To His Coy Mistress ’.

Had we but world enough, and time, This coyness, lady, were no crime. We would sit down, and think which way To walk, and pass our long love’s day. Thou by the Indian Ganges’ side Shouldst rubies find; I by the tide Of Humber would complain. I would Love you ten years before the flood …

Marvell, addressing his sweetheart, says that the woman’s reluctance to have sex with him would be fine, if life wasn’t so short. But such a plan is a fantasy, because in reality, our time on Earth is short. Marvell says that, in light of what he’s just said, the only sensible thing to do is to enjoy themselves and go to bed together – while they still can.

The poem is famous for its enigmatic reference to the poet’s ‘vegetable love’ – which has, perhaps inevitably, been interpreted as a sexual innuendo, and gives us a nice example of the metaphysical poets’ love of unusual metaphors.

2 thoughts on “The Best Examples of Metaphysical Poetry in English Literature”

Death Be Not Proud is a favorite.

- Pingback: Sunday Post – 19th May, 2019 #Brainfluffbookblog #SundayPost | Brainfluff

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from interesting literature.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish?

- About The Review of English Studies

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Books for Review

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Metaphysics.

- < Previous

Shakespeare’s Metaphysical Poem: Allegory, Metaphysics, and Aesthetics in ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Ted Tregear, Shakespeare’s Metaphysical Poem: Allegory, Metaphysics, and Aesthetics in ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’, The Review of English Studies , Volume 74, Issue 316, October 2023, Pages 635–651, https://doi.org/10.1093/res/hgad055

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Long treated as a poetic curio or a biographical riddle, Shakespeare’s poetic contribution to the 1601 Loves Martyr —usually known as ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’—has recently been reclaimed as an experiment in metaphysical poetry. This essay sets out to ask what that means: for the poem, for metaphysical poetry, and for metaphysics itself. It argues that Shakespeare draws on the language of metaphysics, and its canonical problems, to test the relationship between poetic and philosophical thinking. It follows the poem as it charts the efforts, and failures, of both allegory and metaphysics to apprehend the thought-defying love between phoenix and turtle. It shows how that love engages the dilemma of the particular and the universal, a dilemma native to metaphysics since Aristotle, but felt most acutely in the realm of aesthetic experience. And it suggests that, in sounding out the limits of metaphysical reason, Shakespeare’s poem allows for poetry to think in a way that metaphysics cannot. ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ ends in mourning: for the death of phoenix and turtle, and for the demise of the metaphysical transcendentals they seemed in hindsight to uphold. That mourning might nonetheless offer poetry its vocation, as the space where reason might remember and reflect on the object of its loss.

When, in 1601, John Marston read through Shakespeare’s latest poem, the word that came to his mind was metaphysical . ‘O Twas a mouing Epicedium ’, he enthused, in the contribution to the 1601 Loves Martyr placed immediately after Shakespeare’s own. 1 His praise is shared between that epicedium and its subjects, the phoenix and turtle-dove that he, like Shakespeare, sets out to memorialize. Marston soon warms to his theme: Lo now; th’xtracture of deuinest Essence , The Soule of heauens labour’d Quintessence , ( Peans to Phoebus ) from deare Louer’s death, Takes sweete creation and all blessing breath. ( LM , 2A1 r )

Whatever issues from these lovers’ death is more refined than essence, more ensouled than quintessence, against whose creation the heavens’ own alchemy looks laboured. That labour, the sheer effort of working out what has just happened, becomes the subject of Marston’s poem, and draws him towards the rich but recondite domain of metaphysics: Raise my inuention on swift Phantasie, That whilst of this same Metaphisicall God, Man, nor Woman, but elix’d of all My labouring thoughts, with strained ardor sing, My Muse may mount with an vncommon wing. (2A1 r )

Squeezed out in italics like the poem’s other terms of art, ‘ Metaphisicall ’ hangs at the end of the line, as though sucking the air out of Marston’s lungs. As the poet recovers, he finds it hard to work out what, exactly, might be metaphysical here: ‘God’, ‘Man’, and ‘Woman’ are all possibilities, but with nor , all are revoked as inadequate to the task. The result is a word left somewhere between an adjective and a noun, so transcending all substantives that it becomes almost substantial in itself. Marston follows Shakespeare to the heights of metaphysics; but what is metaphysical about Shakespeare’s poem, it seems, is all but unspeakable.

Marston enjoyed ramping up his diction like this. By 1601, it had become a hallmark of his style, which grazes along the knife-edge of grandiloquence and pretension: polysyllabic, neologistic, and conspicuously philosophical. ‘No speech is Hyperbolicall, | To this perfection blessed’, he claims, and he puts that claim to the test. Compared to that perfection, ‘that boundlesse Ens ’, ‘all Beings’ are ‘deck’d and stained’; ‘ Ideas that are idly fained | Onely here subsist inuested’ ( LM , 2A1 v ). Lines like these made Marston a pioneer in what Patrick Cheney has recently christened the ‘metaphysical sublime’, a poetry that propels itself into raptures beyond thinking’s customary bounds. 2 Indeed, his contribution to Loves Martyr is the first time a seventeenth-century poem identifies itself, albeit by association, as metaphysical. The word’s application to a certain style of poetry—smart, witty, metaphorically and conceptually audacious—predates its usage by Samuel Johnson, and earlier by John Dryden, both of them usually credited with bequeathing the idea of ‘metaphysical poetry’ to literary criticism. As early as the 1640s, William Drummond was already defending poetry against those who ‘endevured to abstracte her to Metaphysicall Ideas, and Scholasticall Quiddityes’. 3 Drummond was most likely thinking of John Donne, whose Poems had recently appeared in print; but he may equally have been thinking of Loves Martyr , which appears on his reading list from 1606. 4 If Marston can be read as a metaphysical poet avant la lettre , so too can the poet he celebrates in such glowing terms. Shakespeare’s poem in Loves Martyr is untitled; it merely begins, with disorienting simplicity, ‘Let the bird of lowdest lay’. Since the nineteenth century, it has been known as ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’—a title which, however convenient, risks begging the question, in distinguishing from the outset two lovers whose divisions are rendered so massively vexing. Mired for much of its existence in historical and biographical speculation regarding its cast of characters, the poem has more recently been reclaimed as a vital document in literary history. ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’, James Bednarz argues, is ‘the first great published “metaphysical” poem in English’. 5

Following Marston’s cue, this essay sets out to read Shakespeare’s poem as an experiment in metaphysical poetry, and to understand what that might mean: for the poem, for metaphysical poetry, and for metaphysics itself. These terms are on the move in literary scholarship. Long regarded with some suspicion, and retained, if at all, with caution, the idea of metaphysical poetry has been taken up by recent scholars as an invitation to reconsider the affinity between poetry and metaphysics in seventeenth-century writing. Work by Gordon Teskey, Wendy Beth Hyman, James Kuzner, and others, has shown how lyrics like Shakespeare’s might be metaphysical, not by rehearsing metaphysical arguments, or reciting their terms of art, but by pursuing a kind of thinking in excess of philosophy. 6 ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ itself should dispel any lingering assumptions that a poem’s philosophical content must be extracted and formalized before it can count as truly philosophical. Such a position would accept that whatever knowledge poetry offered must be revoiced in the language of reason; whereas, as we will see, it is Reason that must borrow poetry’s voice for its ‘ Threne ’. Meanwhile, elsewhere in early modern scholarship, metaphysics has been reconceived as a much broader enterprise than previously thought, encompassing a greater variety of writers, forms, and styles. 7 Yet the problem of its definition—of what counts as metaphysics—has only grown starker as a result. In a sense, the history of metaphysics is the history of its attempts to define itself. 8 As the pursuit of the most extreme or original principles of knowledge, it is continually running up against the challenge that these are things it cannot, or should not, know. From the outset, its claims to primacy are hedged by doubts, not only over whether it has the right to make those claims—the first of the puzzles ( aporiai ) Aristotle poses in his Metaphysics , whether there can be a single science of first causes—but over what is lost from view when it does. 9 In reading ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ as a metaphysical poem, then, this essay does not look to establish a substantive metaphysics beneath it, nor to splice metaphysics and poetry together without distinction or division. Instead, it looks to this poem to uncover the catachrestic energy latent within the category of ‘metaphysical poetry’—a category that might best be thought of as an instance of its own best-known operation, by which, in Samuel Johnson’s words, ‘[t]he most heterogeneous ideas are yoked by violence together’. 10 Recognizing the tension coiled within this critical term, the resistance revealed and released by such synthetic force, might thus shed new light on poetry, and on metaphysics too.

In Shakespeare’s case, this turns on the question of what, if anything, can be known about the strange union between a phoenix and a turtle-dove. Like Marston, Shakespeare is grappling with what to call the compound at his poem’s heart, and what it might mean for its beholders and survivors. To do this, the poem tests out various strategies of poetic apprehension, trying first allegory, then metaphysics, before admitting defeat. From that defeat emerges a fresh sense of the matter on which this poem sets to work, and the matter of the poem itself; and with that, the poem reaches the juncture between metaphysics and poetry, where the failure of even the subtlest concepts gives onto the puzzlement of aesthetic experience. The following three parts of this essay thus follow the three moments in Shakespeare’s poem, passing through allegory to metaphysics into aesthetics. As the contours of an early modern aesthetics become sharper, thanks to Rachel Eisendrath and others, so it becomes more plausible to read Shakespeare’s poem as an enquiry into the problem on which metaphysics and aesthetics converge: the dialectic of the universal and particular. 11 Of all the puzzles treated in the Metaphysics , Aristotle judged, this was ‘the hardest of all, and most necessary to theorize’ ( Met , 999a24–5). The waning force of Aristotle’s hylomorphic explanation throughout the seventeenth century, under the pressure of corpuscularian thought, brought the problem’s difficulties into sharper focus. 12 Yet although it falls within the sphere of metaphysics, the disturbances it causes are most keenly felt in aesthetic experience. For the philosophy of aesthetics from Kant onwards, finding something beautiful means encountering a particular that will not be subsumed under a universal concept, but will not renounce its right to some sort of universality. As an obstacle to the reconciliation of particulars and universals, beauty is a scandal for reason, not only because it resists the knowing of the universal, but because it refuses to accept the contrary status of sheer material irrationality. Instead, it holds onto the prospect that the particular, sensuous and fragile, might hold a claim to truth—and that, by stopping its ears to that claim, reason makes itself irrational. This does not mean advocating particular against universal, object against concept. It means, instead, attempting to retrieve a new and better universal, one that is able to reflect on reason’s unacknowledged investments.

Something like this drama unfolds over the course of ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’. Grappling with the love and death of the phoenix and turtle drives the poem to try out new-found capacities of scholastic thinking, only to end up exposing the need that thinking serves. At its centre is a critique of reason as Reason, suddenly rendered visible as an all-too-particular personification, and forced to voice its own shortcomings. Reason is thus returned to the world it seemingly rises above, as a material force in the regime of property and property’s rationalization. Yet if the union of the phoenix and turtle provokes this critique, it does not succeed it with a regime of its own. The truth of love is visible on departure; far from championing its cause, the poem marks its passing. ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ ends in an elegy for the lovers who only in hindsight outstrip rationalization—an elegy that is, moreover, itself an attempt to rationalize. After all, the fact that its closing ‘ Threnos ’ is spoken by Reason itself, ‘As Chorus to their Tragique Scene’ (l.52), reveals the extent, both to which reason has been unsettled, and to which poetry remains invested in reason. 13 In this sense, Shakespeare’s poem cannot escape the critique of metaphysics it ventures. Both metaphysics and poetry are ways of thinking whose vaunted powers are stalked by suspicions of redundancy. Both prove incapable of doing justice to the lovers they remember. And both are reduced, at last, to mourning: metaphysics, by the confounding of its desire for knowledge; poetry, by the recognition that it cannot deduce some posterity from these vanished lovers, let alone be that posterity itself. In that conjunction, however, both metaphysics and poetry afford a better sense of what they have lost. The shortcomings of the poem’s metaphysical concepts are determinate: they are what allow the departed particulars to be represented without being traduced. Poetry, likewise, makes those particulars mournable. In a poem that leads from the failure of the concept to the tomb of its objects, Shakespeare presses the metaphysical dialectic of particular and universal towards its terminus in the aesthetic. By its ending, metaphysics has passed into the material, while that material is redeemed only in memory, through the impassioned but impotent sighing of a prayer. ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ closes in the affinity between art and mourning, where the condition for poetry’s autonomy is also its loss, and where its right to exist is a right to memorialize that loss, mournfully.

‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ begins with a fiat which may not make anything happen. The opening stanza issues a summons that falls somewhere between demand, concession, and invitation: Let the bird of lowdest lay, On the sole Arabian tree, Herauld sad and trumpet be: To whose sound chaste wings obay. (ll.1–4)

By the sound of it, these lines should be louder than they are. The bird is identified only by the loudness of its lay, so forceful that it becomes not just the herald but the trumpet too. It joins a raucous choir of birds announced over subsequent stanzas, from the ‘shriking harbinger’ of the owl (l.5) to the ‘death-deuining Swan’ and his ‘defunctiue Musicke’ (ll.14–15). Yet Barbara Everett is surely right that the tenor of these opening lines ‘unmakes imperatives, the mood of power’. 14 Their speaker is not the bird itself, after all, but some other voice, the one that brings this poem into being. However loud the bird may be, if and when it sounds, its voice is invoked with an uncanny sense of calm. It is only muffled further by the poem’s form. The four-line structure of its first 13 stanzas often tends to fall into a three-line unit from which the fourth line stands enigmatically apart. That can give those final lines an epigrammatic feel: ‘Keepe the obsequie so strict’ (l.12), ‘But in them it were a wonder’ (l.32), ‘Either was the others mine’ (l.36), ‘Simple were so well compounded’ (l.44). Here, the three-line arc of the stanza’s first phrase, and the expectant colon at its end, seemingly anticipate some of some rationale for this summons. Instead, the fourth line preserves the pointed abstraction of the scene: through the metonymy that dissolves a flock of birds in a flurry of wings, before attaching the peculiar epithet of ‘chaste’; but above all, through the verb. ‘Obay’ (l.4) could be indicative or imperative: these wings might naturally obey the herald’s sound, or they might need some additional encouragement to do so. It may alternatively remain as a kind of conditional: let this bird be the herald, and only then will these wings obey. If it is hard to conceive how chaste wings might obey that sound, it is harder still to conceive how they might obey to it. The little glitch in the stanza’s grammar slackens a transitive obedience into an indistinct and intransitive response, further unmaking its imperative, and in doing so, placing an awkward weight on an especially vulnerable moment in the poem’s metre. The four-beat, seven-syllable pattern opens a pause between the last stress of one line and the first of the next. As a result, each line seems marked by an implicit diminuendo, each time growing quieter and slower before restarting in the following line. Rather than smoothing over that technical vulnerability, Shakespeare seems intent on exacerbating it, by routinely beginning his lines with the most unprepossessing of words. ‘To whose sound’ (l.4); ‘To this troupe’ (l.8); ‘From this Session’ (l.9): these monosyllables carry a prosodic charge they cannot bear, and are somehow thickened as a result. Even before its philosophical meditations on distance and space, then, the poem troubles the question of where it takes place. The prepositions, under the weight of the metre, seem to enfold within them some opaque relations of thought.

Meanwhile, the ebbing urgency of this stanza’s verbs brings a new grammatical shape into view. So wide is the space between ‘Let’ and ‘be’, the two terms of this fiat , that another construction emerges: not the giving of orders, but the positing of a hypothesis: let x be y . The stanza has the ring of a geometrical theorem, defining and constructing terms of interpretation that have not yet been set. 15 This is what makes it hard to know what, if anything, is taking place. Over its opening movement, ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ introduces a catafalque of birds, and matches them with a corresponding set of ritual functions. But the form of that ritual wavers. The ‘Session’ (l.9) announced at the beginning of one stanza morphs, by its end, into an ‘obsequie’ (l.12), until the ‘ Requiem ’ (l.16) reframes it finally as a funeral. Yet unless the invitations of Let are accepted, none of these birds arrives, and none of their functions are performed. If one reading sees a procession of birds acting out a funeral, another would emphasize the birds on the one hand, and the funeral on the other, with only the direction of the poem’s mysterious voice to read them together. That direction is more suggestive than instructive: not x is y , but let x be y . By the time that same grammar returns in the fourth stanza, what is standing for what is harder to say: Let the Priest in Surples white, That defunctiue Musicke can, Be the death-deuining Swan, Lest the Requiem lacke his right. (ll.13–16)

Instead of appointing the swan as priest, the poem posits priest as swan; instead of casting birds in a familiar ritual, a familiar ritual is wrenched out of shape, with only the whiteness of the surplice to establish a correspondence between bird and priest so heterogeneous it is positively surreal. Even the ‘ Requiem ’ momentarily comes alive, not as a ceremony with its rite, but a claimant with his right . Elsewhere in the poem, reversing predications has a similar shock-effect, most startlingly in the Threnos , in a line where the deadness of the birds is promoted, abstracted, and vivified: ‘Death is now the Phoenix nest’ (l.56). For all the interpreting the poem’s nouns have provoked, its verbs are just as strange: whether in the archaism of ‘can’, the aetiolated imperatives like ‘obay’, or simply the kind of hypothetical positing involved in letting one thing be another.

This is the speculative grammar in which the poem’s opening section unfolds. Rather than soldering two terms into identity, it sets them in motion, each defining and destabilizing the other. Shakespeare imports this mode of double speaking from allegory. In his landmark argument for reading ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ as metaphysical poetry, James Bednarz situates it at the transition between two phases of literary production: on the one side, a tradition of allegory, stretching back through Edmund Spenser to medieval writing; on the other, the cool, tricky lyrics of John Donne. ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’, Bednarz writes, is ‘an explicitly self-conscious literary work that reconfigures as metaphysical verse the kind of Spenserian allegory Chester employs’. 16 Yet sliding from allegorical to metaphysical poetry along the literary-historical timeline risks foreclosing allegory’s claim to be the most metaphysical poetry of all. If ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ is Shakespeare’s metaphysical poem, it is one he constructed out of allegory’s resources; and appreciating its metaphysics means appreciating the Spenserian elements of his practice. As Bednarz notes, that in turn means attending to the poem that takes up most of Loves Martyr , by which Shakespeare’s experiment with allegory was mediated: ‘Rosalins Complaint’, by the Welsh poet Robert Chester. ‘Rosalins Complaint’ describes itself on the title-page as ‘ Allegorically shadowing the truth of Loue , in the constant Fate of the Phoenix and Turtle ’ ( LM , A2 r ). Spenser’s example looms large throughout: in its inset history of King Arthur, which picks up where Spenser left off in Book II of The Faerie Queene ; but also in the way that episode of British history is enclosed in allegorical shadows. The love and death of the phoenix and turtle-dove is the overarching narrative of Chester’s poem; but around it play a delirious medley of episodes, from an aerial tour of the wonders of the world, to catalogues of flora and fauna, to alphabetical and acrostic celebrations of phoenix and turtle. That eclecticism is perhaps part of allegory’s strategy, a way of signalling the subordination of poetic narrative to some external locus of meaning. 17 In Chester’s hands, though, allegorical polysemy may be just too multiple to form a unified hermeneutic vision. Characters are sporadically identified with abstractions, but seem unable to sustain them. One moment the turtle-dove is constancy, the next, liberal honour. The phoenix may not even be a phoenix at all: ‘O stay me not, I am no Phoenix I’, it insists, ‘And if Ibe that bird, I am defaced’ (C4 v ). Both change meaning as regularly as they change gender. Yet the poem remains insistent that its materials are there to be interpreted.

This paradox is restated insistently in a self-standing poem, ‘To those of light beleefe’, where Chester instructs his poem’s readers: You gentle fauourers of excelling Muses , And gracers of all Learning and Desart, You whose Conceit the deepest worke peruses, Whose Iudgements still are gouerned by Art: Reade gently what you reade, this next conceit Fram’d of pure loue, abandoning deceit. And you whose dull Imagination, And blind conceited Error hath not knowne, Of Herbes and Trees true nomination, But thinke them fabulous that shall be showne: Learne more, search much, and surely you shall find, Plaine honest Truth and Knowledge comes behind. ( LM , C4 r )

Playing on that keyword of allegory, ‘conceit’—perhaps borrowed from Spenser’s letter to Ralegh—Chester praises readers who identify his poem as a ‘conceit | Fram’d of pure loue’, and muster the corresponding ‘Conceit’ while perusing it. By contrast, he censures those whose ‘blind conceited Error’ blocks them from the ‘Plaine honest Truth and Knowledge’ behind the poem’s surface. As the reception of Loves Martyr , and its fervid biographical overinterpretation, have proved, distinguishing between one kind of ‘conceit’ and another is far from self-evident. Rather than signalling Chester’s incompetence, however, this might reveal something about writing allegory after Spenser. Allegory seems to invest a poem with the hope of perfect comprehensibility, through which it might be conceived as true or good and not just as beautiful. Yet the darkness of its conceit suggests this comprehensibility is, if not absent, then certainly hidden. In the absence of some conceptual schema by which the poem’s details could be ordered, but without permission to enjoy those details free from the concept’s demands, allegory is legible only through the piecemeal work of speculation. Only by searching much and learning more can the poem’s readers hope to light on its allegorical moments: the mediations of universal and particular, local and provisional, rather than either’s predominance. 18

If Shakespeare took anything from Chester, it was allegory’s capacity to provoke this kind of thinking. The result, in ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’, is a puzzle: a scene that unfolds according to some cryptic set of norms; a voice that relates those norms, without explaining or performing them; a cast of characters whose significance is uncertain; and a letting-be which holds those characters in a sort of double vision. ‘As a communal ritual of consolation full of shared meanings’, writes Anita Gilman Sherman, ‘the poem seems to instantiate the reverse of a private language and to undo its possibility. Yet, it verges on the unintelligible by offering us the conundrum of a private language on a social scale’. 19 In simultaneously urging collective sense-making and singular incomprehensibility like this, this poem situates itself at the juncture between the universal and particular. That is the site of allegory, and its traffic between its materials and their meaning. But it is also the site of judgement, which from Aristotle onwards had been tasked with relating sensible particulars to intelligible universals. 20 It is this tradition Kant continues, in his third Critique , in defining judgement as ‘the ability to think the particular as contained under the universal’: the rule, the principle, the law. 21 Whether moving from universal to particular, or vice versa, judgement involves a process Kant calls Beurteilung , or ‘estimating’. That process is most energetic in the experience of beauty, where judgement tries and fails to file the stuff of appearance under conceptual headings: lingering over the sensuous particular at hand, without giving up the search for some concept, some universal by which it might be known. In a sense, then, allegory might be seen as an allegory for aesthetic judgement itself. The feverish interpretation required of its readers is a model for the cognitive whirring Kant describes: learning more, searching more, scanning the world in hope of finding recognition. The artwork encourages us to look for its presiding norms, the standards by which we might call it beautiful and know what we mean; yet it escapes subsumption under the universals of understanding (the true) or reason (the good). Although the interpretations it elicits take the form of statements about the work itself, they prove unable to substantiate their claim to cognition, but equally unable to exchange that claim for the comfort of indifferent liking.

The tension between universal and particular ran through aesthetics long before Kant. For Aquinas, Maura Nolan has shown, beauty held a universal scope as a metaphysical transcendental while retaining an irreducibly particular moment in its relation to subjective cognition. 22 That medieval legacy only clarifies the closeness of aesthetics to metaphysics. The dilemma of particular and universal, we have seen, is one they share. Not just a problem, perhaps the problem, on which metaphysics works since Aristotle, it is a problem for metaphysics itself, because it throws into doubt the spectrum of thinking that is its condition of possibility. Aristotle establishes that spectrum at the opening of the Metaphysics , which begins in the love of knowledge: ‘all people by nature desire to know’ ( Met , 980a1). That desire moves upwards from experience ( empeira ) to art ( technē ) to knowledge ( epistēmē ), and from particulars to universals, until, with the first philosophy known afterwards as metaphysics, thinking reaches the first causes of everything that exists. Metaphysical enquiry thus involves an ascent from the particulars, even if Aristotle resists the hypostasis of otherworldly principles he attributes to Plato. It is premised on human cognition as allowing that ascent by progressing through a series of homogeneous moments, from experience to knowledge, whose continuity and hierarchy can make things cohere. Crucially, there is an affinity here with allegory. The fourfold allegorical method developed by Origen and later Christian thinkers, Angus Fletcher has argued, corresponds to an Aristotelian search for the four causes; with this method, readers of allegory follow the path of metaphysics, asking after the essence and meaning of what they read, and stopping only at the universal in which the conceit is illuminated. 23 For Fletcher, as for many theorists of allegory, this spiriting of particulars into universals taints metaphysics and allegory alike with an ideological guilt. Yet what Shakespeare presents in ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ is an alternative possibility latent in allegorical technique. As the following part will argue, the poem shows the recursions of thought from universality as it is driven back to its bodies. But these recursions release an energy that rises above particulars even as it immerses itself in them, to find what, speaking of allegory, Namratha Rao has called ‘a moving concept, one that is both critical and speculative’. 24 The charting of that dialectic, in both its moments, is what makes Shakespeare’s poem metaphysical. Metaphysics’ desire to know may be nothing but wishful thinking, or, worse, the impulse towards domination. But it also makes metaphysics a thinking which can divulge its own innermost wishes.

‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ stages a ‘Session’ that might pass judgement on the phoenix and turtle, and a ‘ Requiem ’ that might set them to rest. But even assuming the ritual can begin—as it seems, in the poem’s second movement, to do—it cannot reconcile the particular and universal dimensions of its central figures. Here the Antheme doth commence, Love and Constancie is dead, Phoenix and the Turtle fled, In a mutuall flame from hence. (ll.21–4)

As this new voice enters, it sounds as though the allegory’s conceit is spoken out loud. ‘Love’ and ‘Constancie’ reveal themselves as the proper essences of phoenix and turtle; with their demise, the concepts they signified and instantiated are dead. Nonetheless, mapping one pair onto another already oversimplifies the internal fusion of love and constancy, for which only a singular verb, ‘is’, is required. Meanwhile, the distinction of the stanza’s internal rhyme is as important as its identification: if love and constancy are ‘dead’, here, in this anthem, the phoenix and turtle may have ‘fled’, still living somewhere ‘hence’. This is the story of the philosophical concepts that characterize the second part of Shakespeare’s poem. Those concepts are brought in to determine what this love between phoenix and turtle might mean; but no sooner do they enter than they are denatured by that love’s resistance to determination. Introduced as the poem’s metaphysical causes, they end up as its materials. So, by the following stanza, ‘Love and Constancie’ has been further reduced, such that now, love alone is the presiding conceit: So they loued as loue in twaine, Had the essence but in one, Two distincts, Diuision none, Number there in loue was slaine. Hearts remote, yet not asunder; Distance and no space was seene, Twixt this Turtle and his Queene; But in them it were a wonder. (ll.25–32)

These stanzas touch on the oldest question of metaphysics—that is, in Aristotle’s description, the question of being qua being; and their answer is somewhat akin to his. What makes something the thing it is, for Aristotle, is its essence : neither the form-matter compound of the concrete object, nor the universal form over and above matter, but the universal actualized and bodied forth by the particular. Correspondingly, in Shakespeare’s poem, the two lovers are materially independent but ontologically identical. They may still be ‘in twaine’, but their true being, the essence, is ‘in one’; and that essence is one only by splitting itself into two. That metaphysical partition is shored up as the stanzas continue. The phoenix and turtle, we learn, simultaneously fulfil and fail the scholastic criteria of what it is to be one thing, as in se indivisum , undivided in themselves, and simultaneously ab aliis divisum , distinct from each other. Their hearts are remote, but not asunder, because their ontological sameness coincides with their accidental differences of distance.

The technical subtlety of these arguments has sometimes reminded readers of attempts to explain how the Trinity’s three persons might share one indivisible substance. J. V. Cunningham even landed on the idea of the Trinity as the ‘clue’ to reading Shakespeare’s poem, the system of norms through which ‘all the difficulties of the expository part of the poem are resolved’. 25 As a result, these lines are often taken as the key to the poem’s metaphysics, or theology, or political theology. Yet they feel just as invested in rearticulating the problem itself, through ever finer degrees of extremity, as in propounding a solution. This would bring them closer to the early modern culture of paradox, in which the Trinity itself could feature alongside other ‘involved aenigmas and riddles’ to unsettle received opinion. 26 The paradox of the final line above, however, lies in the refusal of paradox’s customary wonder: while in other cases, ‘it were a wonder’, here, the poem claims, it is not. Shakespeare’s stanzas hold the project of metaphysical system together with its dialectical recoil, equally refusing the confidence of doctrine and the paradox’s contrarian flair. This strange combination expresses itself in the poem’s mode of arguing: precise, exacting, but eerily unmoved. These stanzas draw on scholastic concepts and methods, even gently parodying the scholastic tic of distinction by distinguishing distinction itself from division. All the same, they feel simultaneously fragmentary and tranquil. They are more like notes towards a poem; not pushing home an argument, or settling on its terms, but trying again and again to describe the instance of love. For all its philosophical nouns, the verbs in the poem’s second part are in short supply. Strung together with the slightest of connectives, often just a comma, the logical connections remain frustratingly vague. And the arresting force of the line-break stops thought before it can get going. The effect is a sort of philosophical parallax, whose readers must first reconstruct, then reconcile, multiple framings of the phoenix and turtle, on the basis of frustratingly abstruse suggestions. But it also serves to animate the concepts themselves. Without the grammatical nexus that would put them to use, words like ‘Diuision’, ‘Number’, and ‘Distance’—sporadically capitalized as they are—transform from concepts into characters: substances in their own right, players in this philosophical drama.

So it is that metaphysics opens onto allegory once again; and its concepts, technically acute but logically underdetermined, acquire a contradictory prominence. On the one hand, they are hypostatized as universals over and against their particular uses. In absorbing the energies of philosophical argumentation into themselves, they establish themselves as a metaphysical jargon. On the other hand, being relieved of their stricter philosophical functioning also lets them take on an unexpected life of their own. Number cannot count, but can be ‘slaine’ (l.28); and it can only be slain because it can no longer count. Distance, meanwhile—the spatial relation between visible entities—becomes a visible entity itself. Congelations of thinking, these concepts seem both to arrogate thought to themselves, as though it radiated out of them, and simultaneously to make thinking material. Shakespeare develops both tendencies at one stroke as his poem moves from increasingly animate conceptualization towards full-fledged personification: Propertie was thus appalled, That the selfe was not the same: Single Natures double name, Neither two nor one was called. (ll.37–40)

For Aristotle, property ( idion ) is ‘that which does not show the essence of a thing, but belongs to it alone, and is predicated convertibly of it’. 27 As an attribute which denotes the essential character of something, it is a way of defining and thus knowing things. With the love of phoenix and turtle, though, that movement towards knowledge has stalled. No longer does it seem possible to determine the relations between subject and predicate in philosophical propositions; the self-same thing, once it emanates from itself, is no longer the same. The resulting tremor at once makes ‘Propertie’ and makes it appalled; and in being appalled into being, it contravenes its own law. On an Aristotelian account, properties depend on substances; here, property becomes itself a substance. Yet the substance conferred by personification is instantly revoked. ‘Propertie’—one of what would be dubbed the quinque voces of predicable—becomes a speaking persona only to be rendered speechless, appalled by what it sees, and dumbfounded at what to call it: single or double, two, one, or neither. 28

When the next abstraction appears on the scene, it is already afflicted by the curse of property: Reason in it selfe confounded, Saw Diuision grow together, To themselues yet either neither, Simple were so well compounded. That it cried, how true a twaine, Seemeth this concordant one, Loue hath Reason, Reason none, If what parts, can so remaine. (ll.41–8)

At the sight of division growing together, reason seems to divide in on itself, emerging as Reason ‘in it selfe confounded’. The shock is enough to turn one stanza into two, as, in a formal surprise, the poem runs over the break between them. This is almost the only time when its otherwise self-certain form seems disconcerted. Its unruffled manner of proceeding is no longer adequate to the wonder it describes, it seems, and a new voice emerges, an altogether new sound: the startling cry of an abstraction not given to crying. And in that moment, Shakespeare’s experiments with personification reveal a fresh metaphysical significance. For many theorists of allegory, personifications are the worst sort of metaphysics, reducing bodies into concepts without remainder. 29 Here, Reason is the remainder. Its cry is the admission of its failure; unable to stick to the theoretical position of seeing, it is forced to speak for itself. Rather than subsuming the object into the concept, then, this personification drives the concept to reveal itself as object. It is as though we suddenly glimpse the transcendental conditions of the social formation that make the phoenix and turtle in some sense unthinkable. Their love sends a shudder through reason that betrays the subjective investments it had intended to sublate. Reason recognizes the passion in what it witnesses, and simultaneously acknowledges the passion within itself as well: a dialectic of love and reason which undoes their division without drawing them into a lasting concord. And with the challenge of those improper parts ringing in its ears, Reason makes a parting gesture of its own. Its new-found voice is put to work in making ‘this Threne , | To the Phoenix and the Doue ’ (ll.49–50)—moving the poem, in effect, from metaphysics to poetry.

What, then, is the poem saying about the metaphysics it deploys? For Cunningham, its scholastic inflections reach out to Trinitarian theology as its determining intellectual and linguistic context—the metaphysical framework which can ‘sanction’ its thinking. 30 Yet the unsparing clarity of his reading leaves it unclear why, if the Trinity’s logic is so appropriate for the phoenix and turtle, Property and Reason should be so put out. For those who read the poem in light of reason’s collapse, by contrast, these ventures into scholasticism are exclusively critical. In a recent monograph on Loves Martyr , Don Rodrigues thus reads Shakespeare’s poem as a wholesale rejection of metaphysical reason from the standpoint of embodied experience. Speaking for the body captured by ‘externally imposed notions of the rational’, Rodrigues gives voice to the poem itself, which ‘seems to say, Keep your Reason off my body, because it cannot begin to understand me’. 31 My reading of the poem has sympathy with both sides of this argument, but departs from both. Installing metaphysics as the presiding force of ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ would deny the poem’s capacity to think for itself, as though it remained dependent on the heteronomous authority of the understanding for its truth-claims. But establishing an antagonistic dualism between metaphysics and poetry, reason and the body, opens itself to the same charges. In this case, the body becomes some transcendent other—seemingly free from thought’s entanglements, but surreptitiously repeating its distortion, by abandoning its native corporeality and handing itself over for theoretical manipulation. The body is not strong enough to resist the concept’s voracious expansion, for the simple reason that ‘body’ is itself a concept. 32 For this reason, too, the dialectic of universal and particular cannot be resolved by asserting the latter against the former. The particular is a double name, no sooner uttered than it is brought within the ambit of cognition. There is a somatic resistance to the universal in Shakespeare’s poem; but finding it requires subjecting the universal to intense scrutiny on its own terms. For if the particular—the body, the material, the non-conceptual—is tacitly mediated by the concept, then the opposite is also true. Within concepts themselves there is a disavowed residue of the non-conceptual; and it is at the furthest extreme of the concept that this residue manifests itself, in the shudder with which it touches on the limits of its comprehensive powers.