Chapter Four: Theory, Methodologies, Methods, and Evidence

Research Methods

You are viewing the first edition of this textbook. a second edition is available – please visit the latest edition for updated information..

This page discusses the following topics:

Research Goals

Research method types.

Before discussing research methods , we need to distinguish them from methodologies and research skills . Methodologies, linked to literary theories, are tools and lines of investigation: sets of practices and propositions about texts and the world. Researchers using Marxist literary criticism will adopt methodologies that look to material forces like labor, ownership, and technology to understand literature and its relationship to the world. They will also seek to understand authors not as inspired geniuses but as people whose lives and work are shaped by social forces.

Example: Critical Race Theory Methodologies

Critical Race Theory may use a variety of methodologies, including

- Interest convergence: investigating whether marginalized groups only achieve progress when dominant groups benefit as well

- Intersectional theory: investigating how multiple factors of advantage and disadvantage around race, gender, ethnicity, religion, etc. operate together in complex ways

- Radical critique of the law: investigating how the law has historically been used to marginalize particular groups, such as black people, while recognizing that legal efforts are important to achieve emancipation and civil rights

- Social constructivism: investigating how race is socially constructed (rather than biologically grounded)

- Standpoint epistemology: investigating how knowledge relates to social position

- Structural determinism: investigating how structures of thought and of organizations determine social outcomes

To identify appropriate methodologies, you will need to research your chosen theory and gather what methodologies are associated with it. For the most part, we can’t assume that there are “one size fits all” methodologies.

Research skills are about how you handle materials such as library search engines, citation management programs, special collections materials, and so on.

Research methods are about where and how you get answers to your research questions. Are you conducting interviews? Visiting archives? Doing close readings? Reviewing scholarship? You will need to choose which methods are most appropriate to use in your research and you need to gain some knowledge about how to use these methods. In other words, you need to do some research into research methods!

Your choice of research method depends on the kind of questions you are asking. For example, if you want to understand how an author progressed through several drafts to arrive at a final manuscript, you may need to do archival research. If you want to understand why a particular literary work became a bestseller, you may need to do audience research. If you want to know why a contemporary author wrote a particular work, you may need to do interviews. Usually literary research involves a combination of methods such as archival research , discourse analysis , and qualitative research methods.

Literary research methods tend to differ from research methods in the hard sciences (such as physics and chemistry). Science research must present results that are reproducible, while literary research rarely does (though it must still present evidence for its claims). Literary research often deals with questions of meaning, social conventions, representations of lived experience, and aesthetic effects; these are questions that reward dialogue and different perspectives rather than one great experiment that settles the issue. In literary research, we might get many valuable answers even though they are quite different from one another. Also in literary research, we usually have some room to speculate about answers, but our claims have to be plausible (believable) and our argument comprehensive (meaning we don’t overlook evidence that would alter our argument significantly if it were known).

A literary researcher might select the following:

Theory: Critical Race Theory

Methodology: Social Constructivism

Method: Scholarly

Skills: Search engines, citation management

Wendy Belcher, in Writing Your Journal Article in 12 Weeks , identifies two main approaches to understanding literary works: looking at a text by itself (associated with New Criticism ) and looking at texts as they connect to society (associated with Cultural Studies ). The goal of New Criticism is to bring the reader further into the text. The goal of Cultural Studies is to bring the reader into the network of discourses that surround and pass through the text. Other approaches, such as Ecocriticism, relate literary texts to the Sciences (as well as to the Humanities).

The New Critics, starting in the 1940s, focused on meaning within the text itself, using a method they called “ close reading .” The text itself becomes e vidence for a particular reading. Using this approach, you should summarize the literary work briefly and q uote particularly meaningful passages, being sure to introduce quotes and then interpret them (never let them stand alone). Make connections within the work; a sk “why” and “how” the various parts of the text relate to each other.

Cultural Studies critics see all texts as connected to society; the critic therefore has to connect a text to at least one political or social issue. How and why does the text reproduce particular knowledge systems (known as discourses) and how do these knowledge systems relate to issues of power within the society? Who speaks and when? Answering these questions helps your reader understand the text in context. Cultural contexts can include the treatment of gender (Feminist, Queer), class (Marxist), nationality, race, religion, or any other area of human society.

Other approaches, such as psychoanalytic literary criticism , look at literary texts to better understand human psychology. A psychoanalytic reading can focus on a character, the author, the reader, or on society in general. Ecocriticism look at human understandings of nature in literary texts.

We select our research methods based on the kinds of things we want to know. For example, we may be studying the relationship between literature and society, between author and text, or the status of a work in the literary canon. We may want to know about a work’s form, genre, or thematics. We may want to know about the audience’s reading and reception, or about methods for teaching literature in schools.

Below are a few research methods and their descriptions. You may need to consult with your instructor about which ones are most appropriate for your project. The first list covers methods most students use in their work. The second list covers methods more commonly used by advanced researchers. Even if you will not be using methods from this second list in your research project, you may read about these research methods in the scholarship you find.

Most commonly used undergraduate research methods:

- Scholarship Methods: Studies the body of scholarship written about a particular author, literary work, historical period, literary movement, genre, theme, theory, or method.

- Textual Analysis Methods: Used for close readings of literary texts, these methods also rely on literary theory and background information to support the reading.

- Biographical Methods: Used to study the life of the author to better understand their work and times, these methods involve reading biographies and autobiographies about the author, and may also include research into private papers, correspondence, and interviews.

- Discourse Analysis Methods: Studies language patterns to reveal ideology and social relations of power. This research involves the study of institutions, social groups, and social movements to understand how people in various settings use language to represent the world to themselves and others. Literary works may present complex mixtures of discourses which the characters (and readers) have to navigate.

- Creative Writing Methods: A literary re-working of another literary text, creative writing research is used to better understand a literary work by investigating its language, formal structures, composition methods, themes, and so on. For instance, a creative research project may retell a story from a minor character’s perspective to reveal an alternative reading of events. To qualify as research, a creative research project is usually combined with a piece of theoretical writing that explains and justifies the work.

Methods used more often by advanced researchers:

- Archival Methods: Usually involves trips to special collections where original papers are kept. In these archives are many unpublished materials such as diaries, letters, photographs, ledgers, and so on. These materials can offer us invaluable insight into the life of an author, the development of a literary work, or the society in which the author lived. There are at least three major archives of James Baldwin’s papers: The Smithsonian , Yale , and The New York Public Library . Descriptions of such materials are often available online, but the materials themselves are typically stored in boxes at the archive.

- Computational Methods: Used for statistical analysis of texts such as studies of the popularity and meaning of particular words in literature over time.

- Ethnographic Methods: Studies groups of people and their interactions with literary works, for instance in educational institutions, in reading groups (such as book clubs), and in fan networks. This approach may involve interviews and visits to places (including online communities) where people interact with literary works. Note: before you begin such work, you must have Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval “to protect the rights and welfare of human participants involved in research.”

- Visual Methods: Studies the visual qualities of literary works. Some literary works, such as illuminated manuscripts, children’s literature, and graphic novels, present a complex interplay of text and image. Even works without illustrations can be studied for their use of typography, layout, and other visual features.

Regardless of the method(s) you choose, you will need to learn how to apply them to your work and how to carry them out successfully. For example, you should know that many archives do not allow you to bring pens (you can use pencils) and you may not be allowed to bring bags into the archives. You will need to keep a record of which documents you consult and their location (box number, etc.) in the archives. If you are unsure how to use a particular method, please consult a book about it. [1] Also, ask for the advice of trained researchers such as your instructor or a research librarian.

- What research method(s) will you be using for your paper? Why did you make this method selection over other methods? If you haven’t made a selection yet, which methods are you considering?

- What specific methodological approaches are you most interested in exploring in relation to the chosen literary work?

- What is your plan for researching your method(s) and its major approaches?

- What was the most important lesson you learned from this page? What point was confusing or difficult to understand?

Write your answers in a webcourse discussion page.

- Introduction to Research Methods: A Practical Guide for Anyone Undertaking a Research Project by Catherine, Dr. Dawson

- Practical Research Methods: A User-Friendly Guide to Mastering Research Techniques and Projects by Catherine Dawson

- Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches by John W. Creswell Cheryl N. Poth

- Qualitative Research Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice by Michael Quinn Patton

- Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches by John W. Creswell J. David Creswell

- Research Methodology: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners by Ranjit Kumar

- Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques by C.R. Kothari

Strategies for Conducting Literary Research Copyright © 2021 by Barry Mauer & John Venecek is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

MA English literature EL7308 RESEARCH METHODS MODULE HANDBOOK

2020, MA English literature EL7308 RESEARCH METHODS MODULE HANDBOOK

This module will enable students to hone the skills required to undertake research in literary studies and which are necessary to present the results of such research through writing and oral presentation. Students are encouraged to think about how to select appropriate methodologies from a range of possible choices, and consider how these methodologies can be used to shape the forms of research undertaken.

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Research Methods for English Studies

- Gabriele Griffin

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: Edinburgh University Press

- Copyright year: 2013

- Audience: College/higher education;

- Main content: 264

- Keywords: Literary Studies

- Published: September 13, 2013

- ISBN: 9780748683444

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Research methods for English studies

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

10 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station22.cebu on June 20, 2022

Quick links

- Make a Gift

- Directories

Theories and Methodologies

Theories and methodologies of english language and literature.

Description: These courses foreground theoretical approaches or methodological developments, including how they affect formal or historical topics. They explore how theories and methods such as Marxism, psychoanalysis, structuralism, phenomenology, reader reception, feminism, critical race theory or ethnography have influenced the production, practice or study of literature, language and culture in English.

Course Goals: While core courses may not achieve every goal, they will participate in the conversations represented in these goals as a central feature.

- To be able to identify main concepts, premises/assumptions, and strengths/liabilities of a theoretical or methodological approach

- To be able to compare and contrast what is distinct about different theoretical or methodological approaches

- To understand the historical and political contexts and stakes of different theoretical or methodological approaches

- To engage theory and method as a focus of analysis and research

- To examine and develop theoretical or methodological strategies for producing and circulating texts and implementing findings within salient academic and/or public conversations

- To explore how social groups or identities emerge through or participate in the production, significance, and reception of theories and methods

Course list for students who entered the major in Summer 2019 and later:

- ENGL 302 Critical Practice (counts as a theory requirement for Creative Writing Students only)

- ENGL 303 (History of Literary Criticism and Theory I)

- ENGL 304 (History of Literary Criticism and Theory II)

- ENGL 305 (Theories of the Imagination)

- ENGL 306 (Introduction to Rhetoric)

- ENGL 307 (Cultural Studies)

- ENGL 308 (Marxism and Literary Theory)

- ENGL 309 (Theories of Reading)

- ENGL 367 (Gender Studies in Literature)

- ENGL 369 (Research Methods in Language & Literature)

- ENGL 370 (English Language Study)

- ENGL 378 (Special Topics in Theories/Methods)

- ENGL 470 (Theory and Practice of Teaching Literature)

- ENGL 471 (Theory and Practice of Teaching Writing)

Note: students who've been accepted to the competitive-admission Creative Writing option in the major may count ENGL 302 toward this category.

- Newsletter

- Faculties and Schools

- Departments

- Research Institutes and Structures of Interdisciplinary Research

- Research Groups

- Other structures

- Board of Directors

- Other University bodies

- Associated institutions

- Institution Chairs

- Person Finder

- Telephone Directory

- Emergencies and Security Contact Information

- PERSONAL AREA UV

- Online Office UV

- Registry Office

- UV Official Bulletin Board

- Virtual Classroom

- Contractor Profile

- Presentation

- Master's Degree description

- Location and contact

- Basic regulations

- Admission and fees

- Master's degree enrolment

- Obtaining the degree

- Results of the programme

- International framework

- Methodological Module

- Specialised Module

- Master's Final Project

- Master's degree coordination

- Teaching staff

- Professional outings

- TFM defended

- Campus life

- Information resources

- Research methods and resources: Language and Linguistics

Research Methods in English Literary Studies

- Writing and presenting an academic paper

The purpose of this subject is to familiarise the student with the methods and resources used for research in English Literature. It is of a highly practical nature and aims to put her or him into contact with the tools necessary to carry out literary research. It stems from the fact that Literature does not exist as an autonomous entity but rather is found within a socio-political, cultural, ideological and aesthetic context which conditions its reception at different moments and in different places. To this aim, the student is introduced to the search for information resources in connection with different critical perspectives from which different literary genres can be analysed. Throughout the course, the student is familiarised with the bibliographical and electronic resources needed for literary research, including reference works, specific glossaries, consultation of catalogues from research libraries, use of databases of literary texts corresponding to different periods and genres, and periodicals relevant to different areas of specialisation.

- Master's programmes in English

- For exchange students

- PhD opportunities

- All programmes of study

- Language requirements

- Application process

- Academic calendar

- NTNU research

- Research excellence

- Strategic research areas

- Innovation resources

- Student in Trondheim

- Student in Gjøvik

- Student in Ålesund

- For researchers

- Life and housing

- Faculties and departments

- International researcher support

Språkvelger

Course - research methods in literature studies - litt3001, course-details-portlet, litt3001 - research methods in literature studies, examination arrangement.

Examination arrangement: Home examination Grade: Letter grades

Course content

This course will provide insight into central methodological issues within the field of literature studies. A primary goal is to give students an understanding of the diversity of methods that characterizes literary criticism. The course aims to train students in developing research questions and to assess the applicability and relevance of different research methods, thus providing them with the foundation for developing individual master's projects. The course will provide students with understanding of the connections between critical perspectives and methodological approaches.

Among others, the course will discuss the following topics:

- Methods for examining the relationship between literature and society, literature and history, author and text, and questions related to the literary canon

- Methods for examining the relationship between literature and form, genre and thematics

- Methods for examining the relationship between literature, reading and reception

- The use of physical and digital archives

- Methods for researching literature and education

Learning outcome

Candidates who have passed this course

- have the knowledge to evaluate the applicability and relevance of different research methods in the research of others as well as in their own

- can develop research questions in literature studies and at the same time describe what methods may be applicable to examine various problems

- can discuss how different approaches to literature may result in different interpretations of the same text

- are able to apply terms in, and knowledge of, literature studies in practical work with literature

- are able to find and evaluate literary criticism

Learning methods and activities

Lectures/seminars. The course is taught in English or Norwegian. Students are expected to participate actively in the lectures/seminars for example by presentations, comments and other contributions. Students are required to use the course learning platform regularly.

Obligatory assignment: A written assignment in groups where students discuss different methodological choices in working with a literary text. An approved obligatory assignment is valid for 2 semesters (the semester in which the approval is given, plus the following semester).

Compulsory assignments

- 1 written assignment (in groups)

Further on evaluation

The course is assessed by a written home examination (approx. 4000 words, 5 days). The exam must be answered in Norwegian or English.

Recommended previous knowledge

Relevant undergraduate courses in literature.

Required previous knowledge

At least 7.5 credits (studiepoeng) of courses in literature at ENG2000-, FRA2000-, NORD2000-, or TYSK2000-level.

Course materials

A pensum consisting of 700-800 pages of articles/chapter excerpts focused on research methods, plus a limited selection of short literary texts. Curriculum/reading list will be made available at the beginning of the semester.

Credit reductions

- Blackboard - AUTUMN-2021

Version: 1 Credits: 7.5 SP Study level: Second degree level

Term no.: 1 Teaching semester: AUTUMN 2023

Language of instruction: Norwegian

Location: Trondheim

- English Literature

- French Literature

- Comparative Literature

- Scandinavian Language and Literature

- Scandinavian Literature

- German Literature

Department with academic responsibility Department of Language and Literature

Examination

Examination arrangement: home examination.

Release 2023-11-30

Submission 2023-12-05

Release 2024-03-04

Submission 2024-03-08

- * The location (room) for a written examination is published 3 days before examination date. If more than one room is listed, you will find your room at Studentweb.

For more information regarding registration for examination and examination procedures, see "Innsida - Exams"

More on examinations at NTNU

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Reviewing the research methods literature: principles and strategies illustrated by a systematic overview of sampling in qualitative research

Stephen j. gentles.

1 Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario Canada

4 CanChild Centre for Childhood Disability Research, McMaster University, 1400 Main Street West, IAHS 408, Hamilton, ON L8S 1C7 Canada

Cathy Charles

David b. nicholas.

2 Faculty of Social Work, University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Jenny Ploeg

3 School of Nursing, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario Canada

K. Ann McKibbon

Associated data.

The systematic methods overview used as a worked example in this article (Gentles SJ, Charles C, Ploeg J, McKibbon KA: Sampling in qualitative research: insights from an overview of the methods literature. The Qual Rep 2015, 20(11):1772-1789) is available from http://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol20/iss11/5 .

Overviews of methods are potentially useful means to increase clarity and enhance collective understanding of specific methods topics that may be characterized by ambiguity, inconsistency, or a lack of comprehensiveness. This type of review represents a distinct literature synthesis method, although to date, its methodology remains relatively undeveloped despite several aspects that demand unique review procedures. The purpose of this paper is to initiate discussion about what a rigorous systematic approach to reviews of methods, referred to here as systematic methods overviews , might look like by providing tentative suggestions for approaching specific challenges likely to be encountered. The guidance offered here was derived from experience conducting a systematic methods overview on the topic of sampling in qualitative research.

The guidance is organized into several principles that highlight specific objectives for this type of review given the common challenges that must be overcome to achieve them. Optional strategies for achieving each principle are also proposed, along with discussion of how they were successfully implemented in the overview on sampling. We describe seven paired principles and strategies that address the following aspects: delimiting the initial set of publications to consider, searching beyond standard bibliographic databases, searching without the availability of relevant metadata, selecting publications on purposeful conceptual grounds, defining concepts and other information to abstract iteratively, accounting for inconsistent terminology used to describe specific methods topics, and generating rigorous verifiable analytic interpretations. Since a broad aim in systematic methods overviews is to describe and interpret the relevant literature in qualitative terms, we suggest that iterative decision making at various stages of the review process, and a rigorous qualitative approach to analysis are necessary features of this review type.

Conclusions

We believe that the principles and strategies provided here will be useful to anyone choosing to undertake a systematic methods overview. This paper represents an initial effort to promote high quality critical evaluations of the literature regarding problematic methods topics, which have the potential to promote clearer, shared understandings, and accelerate advances in research methods. Further work is warranted to develop more definitive guidance.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13643-016-0343-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

While reviews of methods are not new, they represent a distinct review type whose methodology remains relatively under-addressed in the literature despite the clear implications for unique review procedures. One of few examples to describe it is a chapter containing reflections of two contributing authors in a book of 21 reviews on methodological topics compiled for the British National Health Service, Health Technology Assessment Program [ 1 ]. Notable is their observation of how the differences between the methods reviews and conventional quantitative systematic reviews, specifically attributable to their varying content and purpose, have implications for defining what qualifies as systematic. While the authors describe general aspects of “systematicity” (including rigorous application of a methodical search, abstraction, and analysis), they also describe a high degree of variation within the category of methods reviews itself and so offer little in the way of concrete guidance. In this paper, we present tentative concrete guidance, in the form of a preliminary set of proposed principles and optional strategies, for a rigorous systematic approach to reviewing and evaluating the literature on quantitative or qualitative methods topics. For purposes of this article, we have used the term systematic methods overview to emphasize the notion of a systematic approach to such reviews.

The conventional focus of rigorous literature reviews (i.e., review types for which systematic methods have been codified, including the various approaches to quantitative systematic reviews [ 2 – 4 ], and the numerous forms of qualitative and mixed methods literature synthesis [ 5 – 10 ]) is to synthesize empirical research findings from multiple studies. By contrast, the focus of overviews of methods, including the systematic approach we advocate, is to synthesize guidance on methods topics. The literature consulted for such reviews may include the methods literature, methods-relevant sections of empirical research reports, or both. Thus, this paper adds to previous work published in this journal—namely, recent preliminary guidance for conducting reviews of theory [ 11 ]—that has extended the application of systematic review methods to novel review types that are concerned with subject matter other than empirical research findings.

Published examples of methods overviews illustrate the varying objectives they can have. One objective is to establish methodological standards for appraisal purposes. For example, reviews of existing quality appraisal standards have been used to propose universal standards for appraising the quality of primary qualitative research [ 12 ] or evaluating qualitative research reports [ 13 ]. A second objective is to survey the methods-relevant sections of empirical research reports to establish current practices on methods use and reporting practices, which Moher and colleagues [ 14 ] recommend as a means for establishing the needs to be addressed in reporting guidelines (see, for example [ 15 , 16 ]). A third objective for a methods review is to offer clarity and enhance collective understanding regarding a specific methods topic that may be characterized by ambiguity, inconsistency, or a lack of comprehensiveness within the available methods literature. An example of this is a overview whose objective was to review the inconsistent definitions of intention-to-treat analysis (the methodologically preferred approach to analyze randomized controlled trial data) that have been offered in the methods literature and propose a solution for improving conceptual clarity [ 17 ]. Such reviews are warranted because students and researchers who must learn or apply research methods typically lack the time to systematically search, retrieve, review, and compare the available literature to develop a thorough and critical sense of the varied approaches regarding certain controversial or ambiguous methods topics.

While systematic methods overviews , as a review type, include both reviews of the methods literature and reviews of methods-relevant sections from empirical study reports, the guidance provided here is primarily applicable to reviews of the methods literature since it was derived from the experience of conducting such a review [ 18 ], described below. To our knowledge, there are no well-developed proposals on how to rigorously conduct such reviews. Such guidance would have the potential to improve the thoroughness and credibility of critical evaluations of the methods literature, which could increase their utility as a tool for generating understandings that advance research methods, both qualitative and quantitative. Our aim in this paper is thus to initiate discussion about what might constitute a rigorous approach to systematic methods overviews. While we hope to promote rigor in the conduct of systematic methods overviews wherever possible, we do not wish to suggest that all methods overviews need be conducted to the same standard. Rather, we believe that the level of rigor may need to be tailored pragmatically to the specific review objectives, which may not always justify the resource requirements of an intensive review process.

The example systematic methods overview on sampling in qualitative research

The principles and strategies we propose in this paper are derived from experience conducting a systematic methods overview on the topic of sampling in qualitative research [ 18 ]. The main objective of that methods overview was to bring clarity and deeper understanding of the prominent concepts related to sampling in qualitative research (purposeful sampling strategies, saturation, etc.). Specifically, we interpreted the available guidance, commenting on areas lacking clarity, consistency, or comprehensiveness (without proposing any recommendations on how to do sampling). This was achieved by a comparative and critical analysis of publications representing the most influential (i.e., highly cited) guidance across several methodological traditions in qualitative research.

The specific methods and procedures for the overview on sampling [ 18 ] from which our proposals are derived were developed both after soliciting initial input from local experts in qualitative research and an expert health librarian (KAM) and through ongoing careful deliberation throughout the review process. To summarize, in that review, we employed a transparent and rigorous approach to search the methods literature, selected publications for inclusion according to a purposeful and iterative process, abstracted textual data using structured abstraction forms, and analyzed (synthesized) the data using a systematic multi-step approach featuring abstraction of text, summary of information in matrices, and analytic comparisons.

For this article, we reflected on both the problems and challenges encountered at different stages of the review and our means for selecting justifiable procedures to deal with them. Several principles were then derived by considering the generic nature of these problems, while the generalizable aspects of the procedures used to address them formed the basis of optional strategies. Further details of the specific methods and procedures used in the overview on qualitative sampling are provided below to illustrate both the types of objectives and challenges that reviewers will likely need to consider and our approach to implementing each of the principles and strategies.

Organization of the guidance into principles and strategies

For the purposes of this article, principles are general statements outlining what we propose are important aims or considerations within a particular review process, given the unique objectives or challenges to be overcome with this type of review. These statements follow the general format, “considering the objective or challenge of X, we propose Y to be an important aim or consideration.” Strategies are optional and flexible approaches for implementing the previous principle outlined. Thus, generic challenges give rise to principles, which in turn give rise to strategies.

We organize the principles and strategies below into three sections corresponding to processes characteristic of most systematic literature synthesis approaches: literature identification and selection ; data abstraction from the publications selected for inclusion; and analysis , including critical appraisal and synthesis of the abstracted data. Within each section, we also describe the specific methodological decisions and procedures used in the overview on sampling in qualitative research [ 18 ] to illustrate how the principles and strategies for each review process were applied and implemented in a specific case. We expect this guidance and accompanying illustrations will be useful for anyone considering engaging in a methods overview, particularly those who may be familiar with conventional systematic review methods but may not yet appreciate some of the challenges specific to reviewing the methods literature.

Results and discussion

Literature identification and selection.

The identification and selection process includes search and retrieval of publications and the development and application of inclusion and exclusion criteria to select the publications that will be abstracted and analyzed in the final review. Literature identification and selection for overviews of the methods literature is challenging and potentially more resource-intensive than for most reviews of empirical research. This is true for several reasons that we describe below, alongside discussion of the potential solutions. Additionally, we suggest in this section how the selection procedures can be chosen to match the specific analytic approach used in methods overviews.

Delimiting a manageable set of publications

One aspect of methods overviews that can make identification and selection challenging is the fact that the universe of literature containing potentially relevant information regarding most methods-related topics is expansive and often unmanageably so. Reviewers are faced with two large categories of literature: the methods literature , where the possible publication types include journal articles, books, and book chapters; and the methods-relevant sections of empirical study reports , where the possible publication types include journal articles, monographs, books, theses, and conference proceedings. In our systematic overview of sampling in qualitative research, exhaustively searching (including retrieval and first-pass screening) all publication types across both categories of literature for information on a single methods-related topic was too burdensome to be feasible. The following proposed principle follows from the need to delimit a manageable set of literature for the review.

Principle #1:

Considering the broad universe of potentially relevant literature, we propose that an important objective early in the identification and selection stage is to delimit a manageable set of methods-relevant publications in accordance with the objectives of the methods overview.

Strategy #1:

To limit the set of methods-relevant publications that must be managed in the selection process, reviewers have the option to initially review only the methods literature, and exclude the methods-relevant sections of empirical study reports, provided this aligns with the review’s particular objectives.

We propose that reviewers are justified in choosing to select only the methods literature when the objective is to map out the range of recognized concepts relevant to a methods topic, to summarize the most authoritative or influential definitions or meanings for methods-related concepts, or to demonstrate a problematic lack of clarity regarding a widely established methods-related concept and potentially make recommendations for a preferred approach to the methods topic in question. For example, in the case of the methods overview on sampling [ 18 ], the primary aim was to define areas lacking in clarity for multiple widely established sampling-related topics. In the review on intention-to-treat in the context of missing outcome data [ 17 ], the authors identified a lack of clarity based on multiple inconsistent definitions in the literature and went on to recommend separating the issue of how to handle missing outcome data from the issue of whether an intention-to-treat analysis can be claimed.

In contrast to strategy #1, it may be appropriate to select the methods-relevant sections of empirical study reports when the objective is to illustrate how a methods concept is operationalized in research practice or reported by authors. For example, one could review all the publications in 2 years’ worth of issues of five high-impact field-related journals to answer questions about how researchers describe implementing a particular method or approach, or to quantify how consistently they define or report using it. Such reviews are often used to highlight gaps in the reporting practices regarding specific methods, which may be used to justify items to address in reporting guidelines (for example, [ 14 – 16 ]).

It is worth recognizing that other authors have advocated broader positions regarding the scope of literature to be considered in a review, expanding on our perspective. Suri [ 10 ] (who, like us, emphasizes how different sampling strategies are suitable for different literature synthesis objectives) has, for example, described a two-stage literature sampling procedure (pp. 96–97). First, reviewers use an initial approach to conduct a broad overview of the field—for reviews of methods topics, this would entail an initial review of the research methods literature. This is followed by a second more focused stage in which practical examples are purposefully selected—for methods reviews, this would involve sampling the empirical literature to illustrate key themes and variations. While this approach is seductive in its capacity to generate more in depth and interpretive analytic findings, some reviewers may consider it too resource-intensive to include the second step no matter how selective the purposeful sampling. In the overview on sampling where we stopped after the first stage [ 18 ], we discussed our selective focus on the methods literature as a limitation that left opportunities for further analysis of the literature. We explicitly recommended, for example, that theoretical sampling was a topic for which a future review of the methods sections of empirical reports was justified to answer specific questions identified in the primary review.

Ultimately, reviewers must make pragmatic decisions that balance resource considerations, combined with informed predictions about the depth and complexity of literature available on their topic, with the stated objectives of their review. The remaining principles and strategies apply primarily to overviews that include the methods literature, although some aspects may be relevant to reviews that include empirical study reports.

Searching beyond standard bibliographic databases

An important reality affecting identification and selection in overviews of the methods literature is the increased likelihood for relevant publications to be located in sources other than journal articles (which is usually not the case for overviews of empirical research, where journal articles generally represent the primary publication type). In the overview on sampling [ 18 ], out of 41 full-text publications retrieved and reviewed, only 4 were journal articles, while 37 were books or book chapters. Since many books and book chapters did not exist electronically, their full text had to be physically retrieved in hardcopy, while 11 publications were retrievable only through interlibrary loan or purchase request. The tasks associated with such retrieval are substantially more time-consuming than electronic retrieval. Since a substantial proportion of methods-related guidance may be located in publication types that are less comprehensively indexed in standard bibliographic databases, identification and retrieval thus become complicated processes.

Principle #2:

Considering that important sources of methods guidance can be located in non-journal publication types (e.g., books, book chapters) that tend to be poorly indexed in standard bibliographic databases, it is important to consider alternative search methods for identifying relevant publications to be further screened for inclusion.

Strategy #2:

To identify books, book chapters, and other non-journal publication types not thoroughly indexed in standard bibliographic databases, reviewers may choose to consult one or more of the following less standard sources: Google Scholar, publisher web sites, or expert opinion.

In the case of the overview on sampling in qualitative research [ 18 ], Google Scholar had two advantages over other standard bibliographic databases: it indexes and returns records of books and book chapters likely to contain guidance on qualitative research methods topics; and it has been validated as providing higher citation counts than ISI Web of Science (a producer of numerous bibliographic databases accessible through institutional subscription) for several non-biomedical disciplines including the social sciences where qualitative research methods are prominently used [ 19 – 21 ]. While we identified numerous useful publications by consulting experts, the author publication lists generated through Google Scholar searches were uniquely useful to identify more recent editions of methods books identified by experts.

Searching without relevant metadata

Determining what publications to select for inclusion in the overview on sampling [ 18 ] could only rarely be accomplished by reviewing the publication’s metadata. This was because for the many books and other non-journal type publications we identified as possibly relevant, the potential content of interest would be located in only a subsection of the publication. In this common scenario for reviews of the methods literature (as opposed to methods overviews that include empirical study reports), reviewers will often be unable to employ standard title, abstract, and keyword database searching or screening as a means for selecting publications.

Principle #3:

Considering that the presence of information about the topic of interest may not be indicated in the metadata for books and similar publication types, it is important to consider other means of identifying potentially useful publications for further screening.

Strategy #3:

One approach to identifying potentially useful books and similar publication types is to consider what classes of such publications (e.g., all methods manuals for a certain research approach) are likely to contain relevant content, then identify, retrieve, and review the full text of corresponding publications to determine whether they contain information on the topic of interest.

In the example of the overview on sampling in qualitative research [ 18 ], the topic of interest (sampling) was one of numerous topics covered in the general qualitative research methods manuals. Consequently, examples from this class of publications first had to be identified for retrieval according to non-keyword-dependent criteria. Thus, all methods manuals within the three research traditions reviewed (grounded theory, phenomenology, and case study) that might contain discussion of sampling were sought through Google Scholar and expert opinion, their full text obtained, and hand-searched for relevant content to determine eligibility. We used tables of contents and index sections of books to aid this hand searching.

Purposefully selecting literature on conceptual grounds

A final consideration in methods overviews relates to the type of analysis used to generate the review findings. Unlike quantitative systematic reviews where reviewers aim for accurate or unbiased quantitative estimates—something that requires identifying and selecting the literature exhaustively to obtain all relevant data available (i.e., a complete sample)—in methods overviews, reviewers must describe and interpret the relevant literature in qualitative terms to achieve review objectives. In other words, the aim in methods overviews is to seek coverage of the qualitative concepts relevant to the methods topic at hand. For example, in the overview of sampling in qualitative research [ 18 ], achieving review objectives entailed providing conceptual coverage of eight sampling-related topics that emerged as key domains. The following principle recognizes that literature sampling should therefore support generating qualitative conceptual data as the input to analysis.

Principle #4:

Since the analytic findings of a systematic methods overview are generated through qualitative description and interpretation of the literature on a specified topic, selection of the literature should be guided by a purposeful strategy designed to achieve adequate conceptual coverage (i.e., representing an appropriate degree of variation in relevant ideas) of the topic according to objectives of the review.

Strategy #4:

One strategy for choosing the purposeful approach to use in selecting the literature according to the review objectives is to consider whether those objectives imply exploring concepts either at a broad overview level, in which case combining maximum variation selection with a strategy that limits yield (e.g., critical case, politically important, or sampling for influence—described below) may be appropriate; or in depth, in which case purposeful approaches aimed at revealing innovative cases will likely be necessary.

In the methods overview on sampling, the implied scope was broad since we set out to review publications on sampling across three divergent qualitative research traditions—grounded theory, phenomenology, and case study—to facilitate making informative conceptual comparisons. Such an approach would be analogous to maximum variation sampling.

At the same time, the purpose of that review was to critically interrogate the clarity, consistency, and comprehensiveness of literature from these traditions that was “most likely to have widely influenced students’ and researchers’ ideas about sampling” (p. 1774) [ 18 ]. In other words, we explicitly set out to review and critique the most established and influential (and therefore dominant) literature, since this represents a common basis of knowledge among students and researchers seeking understanding or practical guidance on sampling in qualitative research. To achieve this objective, we purposefully sampled publications according to the criterion of influence , which we operationalized as how often an author or publication has been referenced in print or informal discourse. This second sampling approach also limited the literature we needed to consider within our broad scope review to a manageable amount.

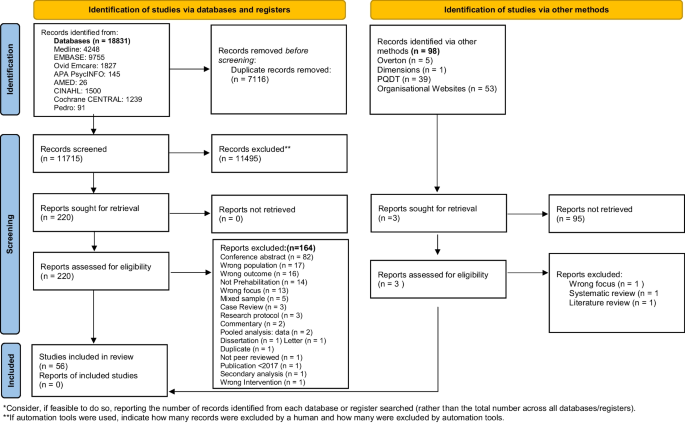

To operationalize this strategy of sampling for influence , we sought to identify both the most influential authors within a qualitative research tradition (all of whose citations were subsequently screened) and the most influential publications on the topic of interest by non-influential authors. This involved a flexible approach that combined multiple indicators of influence to avoid the dilemma that any single indicator might provide inadequate coverage. These indicators included bibliometric data (h-index for author influence [ 22 ]; number of cites for publication influence), expert opinion, and cross-references in the literature (i.e., snowball sampling). As a final selection criterion, a publication was included only if it made an original contribution in terms of novel guidance regarding sampling or a related concept; thus, purely secondary sources were excluded. Publish or Perish software (Anne-Wil Harzing; available at http://www.harzing.com/resources/publish-or-perish ) was used to generate bibliometric data via the Google Scholar database. Figure 1 illustrates how identification and selection in the methods overview on sampling was a multi-faceted and iterative process. The authors selected as influential, and the publications selected for inclusion or exclusion are listed in Additional file 1 (Matrices 1, 2a, 2b).

Literature identification and selection process used in the methods overview on sampling [ 18 ]

In summary, the strategies of seeking maximum variation and sampling for influence were employed in the sampling overview to meet the specific review objectives described. Reviewers will need to consider the full range of purposeful literature sampling approaches at their disposal in deciding what best matches the specific aims of their own reviews. Suri [ 10 ] has recently retooled Patton’s well-known typology of purposeful sampling strategies (originally intended for primary research) for application to literature synthesis, providing a useful resource in this respect.

Data abstraction

The purpose of data abstraction in rigorous literature reviews is to locate and record all data relevant to the topic of interest from the full text of included publications, making them available for subsequent analysis. Conventionally, a data abstraction form—consisting of numerous distinct conceptually defined fields to which corresponding information from the source publication is recorded—is developed and employed. There are several challenges, however, to the processes of developing the abstraction form and abstracting the data itself when conducting methods overviews, which we address here. Some of these problems and their solutions may be familiar to those who have conducted qualitative literature syntheses, which are similarly conceptual.

Iteratively defining conceptual information to abstract

In the overview on sampling [ 18 ], while we surveyed multiple sources beforehand to develop a list of concepts relevant for abstraction (e.g., purposeful sampling strategies, saturation, sample size), there was no way for us to anticipate some concepts prior to encountering them in the review process. Indeed, in many cases, reviewers are unable to determine the complete set of methods-related concepts that will be the focus of the final review a priori without having systematically reviewed the publications to be included. Thus, defining what information to abstract beforehand may not be feasible.

Principle #5:

Considering the potential impracticality of defining a complete set of relevant methods-related concepts from a body of literature one has not yet systematically read, selecting and defining fields for data abstraction must often be undertaken iteratively. Thus, concepts to be abstracted can be expected to grow and change as data abstraction proceeds.

Strategy #5:

Reviewers can develop an initial form or set of concepts for abstraction purposes according to standard methods (e.g., incorporating expert feedback, pilot testing) and remain attentive to the need to iteratively revise it as concepts are added or modified during the review. Reviewers should document revisions and return to re-abstract data from previously abstracted publications as the new data requirements are determined.

In the sampling overview [ 18 ], we developed and maintained the abstraction form in Microsoft Word. We derived the initial set of abstraction fields from our own knowledge of relevant sampling-related concepts, consultation with local experts, and reviewing a pilot sample of publications. Since the publications in this review included a large proportion of books, the abstraction process often began by flagging the broad sections within a publication containing topic-relevant information for detailed review to identify text to abstract. When reviewing flagged text, the reviewer occasionally encountered an unanticipated concept significant enough to warrant being added as a new field to the abstraction form. For example, a field was added to capture how authors described the timing of sampling decisions, whether before (a priori) or after (ongoing) starting data collection, or whether this was unclear. In these cases, we systematically documented the modification to the form and returned to previously abstracted publications to abstract any information that might be relevant to the new field.

The logic of this strategy is analogous to the logic used in a form of research synthesis called best fit framework synthesis (BFFS) [ 23 – 25 ]. In that method, reviewers initially code evidence using an a priori framework they have selected. When evidence cannot be accommodated by the selected framework, reviewers then develop new themes or concepts from which they construct a new expanded framework. Both the strategy proposed and the BFFS approach to research synthesis are notable for their rigorous and transparent means to adapt a final set of concepts to the content under review.

Accounting for inconsistent terminology

An important complication affecting the abstraction process in methods overviews is that the language used by authors to describe methods-related concepts can easily vary across publications. For example, authors from different qualitative research traditions often use different terms for similar methods-related concepts. Furthermore, as we found in the sampling overview [ 18 ], there may be cases where no identifiable term, phrase, or label for a methods-related concept is used at all, and a description of it is given instead. This can make searching the text for relevant concepts based on keywords unreliable.

Principle #6:

Since accepted terms may not be used consistently to refer to methods concepts, it is necessary to rely on the definitions for concepts, rather than keywords, to identify relevant information in the publication to abstract.

Strategy #6:

An effective means to systematically identify relevant information is to develop and iteratively adjust written definitions for key concepts (corresponding to abstraction fields) that are consistent with and as inclusive of as much of the literature reviewed as possible. Reviewers then seek information that matches these definitions (rather than keywords) when scanning a publication for relevant data to abstract.

In the abstraction process for the sampling overview [ 18 ], we noted the several concepts of interest to the review for which abstraction by keyword was particularly problematic due to inconsistent terminology across publications: sampling , purposeful sampling , sampling strategy , and saturation (for examples, see Additional file 1 , Matrices 3a, 3b, 4). We iteratively developed definitions for these concepts by abstracting text from publications that either provided an explicit definition or from which an implicit definition could be derived, which was recorded in fields dedicated to the concept’s definition. Using a method of constant comparison, we used text from definition fields to inform and modify a centrally maintained definition of the corresponding concept to optimize its fit and inclusiveness with the literature reviewed. Table 1 shows, as an example, the final definition constructed in this way for one of the central concepts of the review, qualitative sampling .

Final definition for qualitative sampling , including methodological tradition-specific variations

Developed after numerous iterations in the methods overview on sampling [ 18 ]

We applied iteratively developed definitions when making decisions about what specific text to abstract for an existing field, which allowed us to abstract concept-relevant data even if no recognized keyword was used. For example, this was the case for the sampling-related concept, saturation , where the relevant text available for abstraction in one publication [ 26 ]—“to continue to collect data until nothing new was being observed or recorded, no matter how long that takes”—was not accompanied by any term or label whatsoever.

This comparative analytic strategy (and our approach to analysis more broadly as described in strategy #7, below) is analogous to the process of reciprocal translation —a technique first introduced for meta-ethnography by Noblit and Hare [ 27 ] that has since been recognized as a common element in a variety of qualitative metasynthesis approaches [ 28 ]. Reciprocal translation, taken broadly, involves making sense of a study’s findings in terms of the findings of the other studies included in the review. In practice, it has been operationalized in different ways. Melendez-Torres and colleagues developed a typology from their review of the metasynthesis literature, describing four overlapping categories of specific operations undertaken in reciprocal translation: visual representation, key paper integration, data reduction and thematic extraction, and line-by-line coding [ 28 ]. The approaches suggested in both strategies #6 and #7, with their emphasis on constant comparison, appear to fall within the line-by-line coding category.

Generating credible and verifiable analytic interpretations

The analysis in a systematic methods overview must support its more general objective, which we suggested above is often to offer clarity and enhance collective understanding regarding a chosen methods topic. In our experience, this involves describing and interpreting the relevant literature in qualitative terms. Furthermore, any interpretative analysis required may entail reaching different levels of abstraction, depending on the more specific objectives of the review. For example, in the overview on sampling [ 18 ], we aimed to produce a comparative analysis of how multiple sampling-related topics were treated differently within and among different qualitative research traditions. To promote credibility of the review, however, not only should one seek a qualitative analytic approach that facilitates reaching varying levels of abstraction but that approach must also ensure that abstract interpretations are supported and justified by the source data and not solely the product of the analyst’s speculative thinking.

Principle #7:

Considering the qualitative nature of the analysis required in systematic methods overviews, it is important to select an analytic method whose interpretations can be verified as being consistent with the literature selected, regardless of the level of abstraction reached.

Strategy #7:

We suggest employing the constant comparative method of analysis [ 29 ] because it supports developing and verifying analytic links to the source data throughout progressively interpretive or abstract levels. In applying this approach, we advise a rigorous approach, documenting how supportive quotes or references to the original texts are carried forward in the successive steps of analysis to allow for easy verification.

The analytic approach used in the methods overview on sampling [ 18 ] comprised four explicit steps, progressing in level of abstraction—data abstraction, matrices, narrative summaries, and final analytic conclusions (Fig. 2 ). While we have positioned data abstraction as the second stage of the generic review process (prior to Analysis), above, we also considered it as an initial step of analysis in the sampling overview for several reasons. First, it involved a process of constant comparisons and iterative decision-making about the fields to add or define during development and modification of the abstraction form, through which we established the range of concepts to be addressed in the review. At the same time, abstraction involved continuous analytic decisions about what textual quotes (ranging in size from short phrases to numerous paragraphs) to record in the fields thus created. This constant comparative process was analogous to open coding in which textual data from publications was compared to conceptual fields (equivalent to codes) or to other instances of data previously abstracted when constructing definitions to optimize their fit with the overall literature as described in strategy #6. Finally, in the data abstraction step, we also recorded our first interpretive thoughts in dedicated fields, providing initial material for the more abstract analytic steps.

Summary of progressive steps of analysis used in the methods overview on sampling [ 18 ]

In the second step of the analysis, we constructed topic-specific matrices , or tables, by copying relevant quotes from abstraction forms into the appropriate cells of matrices (for the complete set of analytic matrices developed in the sampling review, see Additional file 1 (matrices 3 to 10)). Each matrix ranged from one to five pages; row headings, nested three-deep, identified the methodological tradition, author, and publication, respectively; and column headings identified the concepts, which corresponded to abstraction fields. Matrices thus allowed us to make further comparisons across methodological traditions, and between authors within a tradition. In the third step of analysis, we recorded our comparative observations as narrative summaries , in which we used illustrative quotes more sparingly. In the final step, we developed analytic conclusions based on the narrative summaries about the sampling-related concepts within each methodological tradition for which clarity, consistency, or comprehensiveness of the available guidance appeared to be lacking. Higher levels of analysis thus built logically from the lower levels, enabling us to easily verify analytic conclusions by tracing the support for claims by comparing the original text of publications reviewed.

Integrative versus interpretive methods overviews

The analytic product of systematic methods overviews is comparable to qualitative evidence syntheses, since both involve describing and interpreting the relevant literature in qualitative terms. Most qualitative synthesis approaches strive to produce new conceptual understandings that vary in level of interpretation. Dixon-Woods and colleagues [ 30 ] elaborate on a useful distinction, originating from Noblit and Hare [ 27 ], between integrative and interpretive reviews. Integrative reviews focus on summarizing available primary data and involve using largely secure and well defined concepts to do so; definitions are used from an early stage to specify categories for abstraction (or coding) of data, which in turn supports their aggregation; they do not seek as their primary focus to develop or specify new concepts, although they may achieve some theoretical or interpretive functions. For interpretive reviews, meanwhile, the main focus is to develop new concepts and theories that integrate them, with the implication that the concepts developed become fully defined towards the end of the analysis. These two forms are not completely distinct, and “every integrative synthesis will include elements of interpretation, and every interpretive synthesis will include elements of aggregation of data” [ 30 ].

The example methods overview on sampling [ 18 ] could be classified as predominantly integrative because its primary goal was to aggregate influential authors’ ideas on sampling-related concepts; there were also, however, elements of interpretive synthesis since it aimed to develop new ideas about where clarity in guidance on certain sampling-related topics is lacking, and definitions for some concepts were flexible and not fixed until late in the review. We suggest that most systematic methods overviews will be classifiable as predominantly integrative (aggregative). Nevertheless, more highly interpretive methods overviews are also quite possible—for example, when the review objective is to provide a highly critical analysis for the purpose of generating new methodological guidance. In such cases, reviewers may need to sample more deeply (see strategy #4), specifically by selecting empirical research reports (i.e., to go beyond dominant or influential ideas in the methods literature) that are likely to feature innovations or instructive lessons in employing a given method.

In this paper, we have outlined tentative guidance in the form of seven principles and strategies on how to conduct systematic methods overviews, a review type in which methods-relevant literature is systematically analyzed with the aim of offering clarity and enhancing collective understanding regarding a specific methods topic. Our proposals include strategies for delimiting the set of publications to consider, searching beyond standard bibliographic databases, searching without the availability of relevant metadata, selecting publications on purposeful conceptual grounds, defining concepts and other information to abstract iteratively, accounting for inconsistent terminology, and generating credible and verifiable analytic interpretations. We hope the suggestions proposed will be useful to others undertaking reviews on methods topics in future.

As far as we are aware, this is the first published source of concrete guidance for conducting this type of review. It is important to note that our primary objective was to initiate methodological discussion by stimulating reflection on what rigorous methods for this type of review should look like, leaving the development of more complete guidance to future work. While derived from the experience of reviewing a single qualitative methods topic, we believe the principles and strategies provided are generalizable to overviews of both qualitative and quantitative methods topics alike. However, it is expected that additional challenges and insights for conducting such reviews have yet to be defined. Thus, we propose that next steps for developing more definitive guidance should involve an attempt to collect and integrate other reviewers’ perspectives and experiences in conducting systematic methods overviews on a broad range of qualitative and quantitative methods topics. Formalized guidance and standards would improve the quality of future methods overviews, something we believe has important implications for advancing qualitative and quantitative methodology. When undertaken to a high standard, rigorous critical evaluations of the available methods guidance have significant potential to make implicit controversies explicit, and improve the clarity and precision of our understandings of problematic qualitative or quantitative methods issues.

A review process central to most types of rigorous reviews of empirical studies, which we did not explicitly address in a separate review step above, is quality appraisal . The reason we have not treated this as a separate step stems from the different objectives of the primary publications included in overviews of the methods literature (i.e., providing methodological guidance) compared to the primary publications included in the other established review types (i.e., reporting findings from single empirical studies). This is not to say that appraising quality of the methods literature is not an important concern for systematic methods overviews. Rather, appraisal is much more integral to (and difficult to separate from) the analysis step, in which we advocate appraising clarity, consistency, and comprehensiveness—the quality appraisal criteria that we suggest are appropriate for the methods literature. As a second important difference regarding appraisal, we currently advocate appraising the aforementioned aspects at the level of the literature in aggregate rather than at the level of individual publications. One reason for this is that methods guidance from individual publications generally builds on previous literature, and thus we feel that ahistorical judgments about comprehensiveness of single publications lack relevance and utility. Additionally, while different methods authors may express themselves less clearly than others, their guidance can nonetheless be highly influential and useful, and should therefore not be downgraded or ignored based on considerations of clarity—which raises questions about the alternative uses that quality appraisals of individual publications might have. Finally, legitimate variability in the perspectives that methods authors wish to emphasize, and the levels of generality at which they write about methods, makes critiquing individual publications based on the criterion of clarity a complex and potentially problematic endeavor that is beyond the scope of this paper to address. By appraising the current state of the literature at a holistic level, reviewers stand to identify important gaps in understanding that represent valuable opportunities for further methodological development.

To summarize, the principles and strategies provided here may be useful to those seeking to undertake their own systematic methods overview. Additional work is needed, however, to establish guidance that is comprehensive by comparing the experiences from conducting a variety of methods overviews on a range of methods topics. Efforts that further advance standards for systematic methods overviews have the potential to promote high-quality critical evaluations that produce conceptually clear and unified understandings of problematic methods topics, thereby accelerating the advance of research methodology.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

There was no funding for this work.

Availability of data and materials

Authors’ contributions.

SJG wrote the first draft of this article, with CC contributing to drafting. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript. All authors except CC (deceased) approved the final draft. SJG, CC, KAB, and JP were involved in developing methods for the systematic methods overview on sampling.

Authors’ information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Ethics approval and consent to participate, additional file.

Submitted: Analysis_matrices. (DOC 330 kb)

Cathy Charles is deceased

Contributor Information

Stephen J. Gentles, Email: moc.liamg@seltnegevets .

David B. Nicholas, Email: ac.yraglacu@salohcin .

Jenny Ploeg, Email: ac.retsamcm@jgeolp .

K. Ann McKibbon, Email: ac.retsamcm@bikcm .

Access, acceptance and adherence to cancer prehabilitation: a mixed-methods systematic review

- Open access

- Published: 06 May 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Tessa Watts 1 ,

- Nicholas Courtier 1 ,

- Sarah Fry 1 ,

- Nichola Gale 1 ,

- Elizabeth Gillen 1 ,

- Grace McCutchan 1 ,

- Manasi Patil 1 ,

- Tracy Rees 1 ,

- Dominic Roche 1 ,

- Sally Wheelwright 2 &

- Jane Hopkinson 1

381 Accesses

13 Altmetric

Explore all metrics