Essay writing guide

Introduction.

The subject of how to write a good essay is covered on many other sites and students are encouraged to read a sample of guides for a full understanding.

Recommended reading

- How to write an essay , University of Manchester, Faculty of Humanities Study Skills

- 3rd year project technical writing advice , University of Manchester, School of Computer Science

- William Strunk's elements of style

Examples of additional reading

- Essay writing & report writing , University of Wollongong

- Essay writing , Edinburgh Napier University

Academic essays and articles usually contain 'references'. These can range from a generalised bibliography or list for "further reading" to specific references for particular points in the text. In this last category references are normally indexed either by the first author's name and publication date, e.g. "[Smith97]" or simply numerically "[5]".

- Read how to reference properly and avoid plagiarism

Advice on the subject of plagiarism can be found under the assessments section of this website.

- MyManchester

- Hardware library

- School library

- University library

- Essay writing

- Exam technique

- LaTeX theses

- Ethics (UG)

FBMH 2019-20

Student Handbooks

Appendix 5: A practical guide to writing essays

Writing an essay is a big task that will be easier to manage if you break it down into five main tasks as shown below:

An essay-writing Model in 5 steps

- Analyse the question

What is the topic?

What are the key verbs?

Question the question—brainstorm and probe

What information do you need?

How are you going to find information?

Find the information

Make notes and/or mind maps.

- Plan and sort

Arrange information in a logical structure

Plan sections and paragraphs

Introduction and conclusion

- Edit (and proofread)

For sense and logical flow

For grammar and spelling.

For length.

My Learning Essentials offers a number of online resources and workshops that will help you to understand the importance of referencing your sources, use appropriate language and style in your writing, write and proofread your essays. For more information visit the writing skills My Learning Essentials pages: http://www.library.manchester.ac.uk/services-and-support/students/support-for-your-studies/my-learning-essentials/

Many students write great essays — but not on the topic they were asked about. First, look at the main idea or topic in the question. What are you going to be writing about? Next, look at the verb in the question — the action word. This verb, or action word, is asking you to do something with the topic.

Here are some common verbs or action words and explanations:

Once you have analysed the question, start thinking about what you need to find out. It’s better and more efficient to have a clear focus for your research than to go straight to the library and look through lots of books that may not be relevant.

Start by asking yourself, ‘What do I need to find out?’ Put your ideas down on paper. A mind map is a good way to do this. Useful questions to start focusing your research are: What? Why? When? How? Where? Who?

- Refer to the advice given in Writing and Referencing Skills for methods to search for information.

First, scan through your source . Find out if there’s any relevant information in what you are reading. If you’re reading a book, look at the contents page, any headings, and the index. Stick a Post-It note on useful pages.

Next, read for detail . Read the text to get the information you want. Start by skimming your eyes over the page to pick our relevant headings, summaries, words. If it’s useful, make notes.

Making notes

There are two rules when you are making notes:

- Note your source so that you can find it again and write your references at the end of the essay if you use that information. Use Endnote (see the section on Referencing), or note down the following:

- page reference

- date of publication

- publisher’s name (book)

- place where it was published (book or journal)

- the journal number, volume and date (journal)

- Make brief notes rather than copy text , but if you feel an extract is very valuable put it in quotation marks so that when you write your essay, you’ll know that you have to put it in your own words. Failing to rewrite the text in your own words would be plagiarism.

- For more information on plagiarism, refer to the Second Level Handbook and the My Learning Essentials Plagiarism Resource http://libassets.manchester.ac.uk/mle/avoiding-plagiarism/.

Everyone will make notes differently as it suits them. However, the aim of making notes when you are researching an essay is to use them when you write the essay. It is therefore important that you can:

- Read your notes

- Find their source

- Determine what the topics and main points are on each note (highlight the main ideas, key points or headings).

- Compose your notes so you can move bits of information around later when you have to sort your notes into an essay.

For example:

- Write/type in chunks (one topic for one chunk) with a space between them so you can cut your notes up later, or

- write the main topics or questions you want to answer on separate pieces of paper before you start making notes. As you find relevant information, write it on the appropriate page. (This takes longer as you have to write the source down a number of times, but it does mean you have ordered your notes into headings.)

Sort information into essay plans

You’ve got lots of information now: how do you put it all together to make an essay that makes sense? As there are many ways to sort out a huge heap of clothes (type of clothes, colour, size, fabric…), there are many ways of sorting information. Whichever method you use, you are looking for ways to arrange the information into groups and to order the groups into a logical sequence . You need to play around with your notes until you find a pattern that seems right and will answer the question.

- Find the main points in your notes, put them on a separate page – a mind map is a good way to do this – and see if your main points form any patterns or groups.

- Is there a logical order? Does one thing have to come after another? Do points relate to one another somehow? Think about how you could link the points.

- Using the information above, draw your essay plan. You could draw a picture, a mind map, a flow chart or whatever you want. Or you could build a structure by using bits of card that you can move around.

- Select and put the relevant notes into the appropriate group so you are ready to start writing your first draft.

The essay has four main parts:

- introduction

- references.

People usually write the introduction and conclusion after they have written the main body of the essay, so we have put them in that order.

For more information on essay writing visit the My Learning Essentials web pages:

https://www.escholar.manchester.ac.uk/learning-objects/mle/packages/writing/

Main Body

Structure . The main body should have a clear structure. Depending on the length of the essay, you may have just a series of paragraphs, or sections with headings, or possibly even subsections. In the latter case, make sure that the hierarchy of headings is obvious so that the reader doesn’t get lost.

Flow . The main body of the essay answers the question and flows logically from one key point to another (each point needs to be backed up by evidence [experiments, research, texts, interviews, etc …] that must be referenced). You should normally write one main idea per paragraph and the main ideas in your essay should be linked or ‘signposted’. Signposts show readers where they are going, so they don’t get lost. This lets the reader know how you are going to tackle the idea, or how one idea is linked with the one before it or after it.

Some signpost words and phrases are:

- ‘These changes . . . “

- ‘Such developments

- ‘This

- ‘In the first few paragraphs . . . “

- ‘I will look in turn at. . . ‘

- ‘However, . . . “

- ‘Similarly’

- ‘But’.

Figures: purpose . You should try to include tables, diagrams, and perhaps photographs in your essay. Tables are valuable for summarising information, and are most likely to impress if they show the results of relevant experimental data. Diagrams enable the reader to visualise things, replacing the need for lengthy descriptions. Photographs must be selected with care, to show something meaningful. Nobody will be impressed by a picture of a giraffe – we all know what one looks like, so the picture would be mere decoration. But a detailed picture of a giraffe’s markings might be useful if it illustrates a key point.

Figures: labelling, legends and acknowledgment . Whenever you use a table, diagram or image in your essay you must:

- cite the source

- make sure that the legend and explanation are adapted to your purpose.

Checklist for the main body of text

- Does your text have a clear structure?

- Does the text follow a logical sequence so that the argument flows?

- Does your text have both breadth and depth – i.e. general coverage of the major issues with in-depth treatment of particularly important points?

- Does your text include some illustrative experimental results?

- Have you chosen the diagrams or photographs carefully to provide information and understanding, or are the illustrations merely decorative?

- Are your figures acknowledged properly? Did you label them and include legend and explanation?

Introduction

The introduction comes at the start of the essay and sets the scene for the reader. It usually defines clearly the subject you will address (e.g. the adaptations of organisms to cold environments), how you will address this subject (e.g. by using examples drawn principally from the Arctic zone) and what you will show or argue (e.g. that all types of organism, from microbes through to mammals, have specific adaptations that fit them for life in cold environments). The length of an introduction depends on the length of your essay, but is usually between 50 to 200 words

Remember that reading the introduction constitutes the first impression on your reader (i.e. your assessor!). Therefore, it should be the last section that you revise at the editing stage, making sure that it leads the reader clearly into the details of the subject you have covered and that it is completely free of typos and spelling mistakes.

Check-list for the Introduction

- Does your introduction start logically by telling the reader what the essay is about – for example, the various adaptations to habitat in the bear family?

- Does your introduction outline how you will address this topic – for example, by an overview of the habitats of bears, followed by in-depth treatment of some specific adaptations?

- Is it free of typos and spelling mistakes?

Conclusion

An essay needs a conclusion. Like the introduction, this need not be long: 50 to 200 words long, depending on the length of the essay. It should draw the information together and, ideally, place it in a broader context by personalising the findings, stating an opinion or supporting a further direction which may follow on from the topic. The conclusion should not introduce facts in addition to those in the main body.

Check-list for the Conclusion

- Does your conclusion sum up what was said in the main body?

- If the title of the essay was a question, did you give a clear answer in the conclusion?

- Does your conclusion state your personal opinion on the topic or its future development or further work that needs to be done? Does it show that you are thinking further?

References

In all scientific writing you are expected to cite your main sources of information. Scientific journals have their own preferred (usually obligatory) method of doing this. The piece of text below shows how you can cite work in an essay, dissertation or thesis. Then you supply an alphabetical list of references at the end of the essay. The Harvard style of referencing adopted at the University of Manchester will be covered in the Writing and Referencing Skills unit in Semester 3. For more information refer to the Referencing Guide from the University Library ( http://subjects.library.manchester.ac.uk/referencing/referencing-harvard ).

Citations in the text

Jones and Smith (1999) showed that the ribosomal RNA of fungi differs from that of slime moulds. This challenged the previous assumption that slime moulds are part of the fungal kingdom (Toby and Dean, 1987). However, according to Bloggs et al . (1999) the slime moulds can still be accommodated in the fungal kingdom for convenience. Slime moulds are considered part of the Eucarya domain by Todar (2012).

Reference list at the end of the essay:

List the references in alphabetical order and if you have several publications written by the same author(s) in the same year, add a letter (a,b,c…) after the year to distinguish between them. Bloggs, A.E., Biggles, N.H. and Bow, R.T. (1999). The Slime Moulds . 2 nd edn. London and New York: Academic Press.

Todar K. (2012) Overview Of Bacteriology. Available at: http://textbookofbacteriology.net, [Accessed 15 November 2013].

Jones, B.B. and Smith, J.O.E. (1999). Ribosomal RNA of slime moulds, Journal of Ribosomal RNA 12, 33-38.

Toby F.S. and Dean P.L. (1987). Slime moulds are part of the fungal kingdom, in Edwards A.E. and Kane Y. (eds.) The Fungal Kingdom. Luton: Osbert Publishing Co., pp. 154-180 .

Endnote : This is an electronic system for storing and retrieving references that you will learn about in the Writing and Referencing Skills (WRS) unit. It is very powerful and simple to use, but you must always check that the output is consistent with the instructions given in this section.

Visit the My Learning Essentials online resource for a guide to using EndNote: https://www.escholar.manchester.ac.uk/learning-objects/mle/endnote-guide/

(we recommend EndNote online if you wish to use your own computer).

Note that journals have their own house style so there will be minor differences between them, particularly in their use of punctuation, but all reference lists for the same journal will be in the same format.

First Draft

When you write your first draft, keep two things in mind:

- Length: you may lose marks if your essay is too long. Ensure therefore that your essay is within the page limit that has been set.

- Expression: don’t worry about such matters as punctuation, spelling or grammar at this stage. You can get this right at the editing stage. If you put too much time into getting these things right at the drafting stage, you will have less time to spend on thinking about the content, and you will be less willing to change it when you edit for sense and flow at the editing stage.

Writing style

The style of your essay should fit the task or the questions asked and be targeted to your reader. Just as you are careful to use the correct tone of voice and language in different situations so you must take care with your writing. Generally writing should be:

- Make sure that you write exactly what you mean in a simple way.

- Write briefly and keep to the point. Use short sentences. Make sure that the meaning of your sentences is obvious.

- Check that you would feel comfortable reading your essay if you were actually the reader.

- Make sure that you have included everything of importance. Take care to explain or define any abbreviations or specialised jargon in full before using a shortened version later. Do not use slang, colloquialisms or cliches in formal written work.

When you are editing your essay, you will need to bear in mind a number of things. The best way to do this, without forgetting something, is to edit in ‘layers’, using a check-list to make sure you have not forgotten anything.

Check-list for Style

- Tone – is it right for the purpose and the receiver?

- Clarity – is it simple, clear and easy to understand?

- Complete – have you included everything of importance?

Check-list for Sense

- Does your essay make sense?

- Does it flow logically?

- Have you got all the main points in?

- Are there bits of information that aren’t useful and need to be chopped out?

- Are your main ideas in paragraphs?

- Are the paragraphs linked to one another so that the essay flows rather than jumps from one thing to another?

- Is it about the right length?

Check-list for Proofreading

- Are the punctuation, grammar, spelling and format correct?

- If you have written your essay on a word-processor, run the spell check over it.

- Have you referenced all quotes and names correctly?

- Is the essay written in the correct format? (one and a half line spacing, margins at least 2.5cm all around the text, minimum font size 10 point).

School Writer in Residence

The School of Biological Sciences has three ‘Writers in Residence’ who are funded by The Royal Literary Fund. They are:

Susan Barker ( [email protected] )– Thursday and Friday

Amanda Dalton ( [email protected] )– Monday and Tuesday

Tania Hershman ( [email protected] ) – Wednesday

The writers in residence can help you with any aspect of your writing including things such as ‘‘how do I start?’ ‘how do I structure a complex essay’ ‘ why am I getting poor marks for my essay writing?’

All you need to do is to bring along a piece of your writing and they will discuss with you on a one to one basis how to resolve the problems that you are having with your piece of writing.

The Writers in Residence are based in the Simon Building. Please see the BIOL20000 Blackboard site for further information about the writers’ expertise and instructions for appointment booking.

Academic writing

- Manchester Institute of Education

Research output : Chapter in Book/Report/Conference proceeding › Chapter › peer-review

Access to Document

- 10.4324/9781351026949-15

Other files and links

- https://www.mendeley.com/catalogue/c50ffaec-be18-3a18-9f85-f78a4aacd56b/

Fingerprint

- Academic Writing Social Sciences 100%

- Writing Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology 100%

- Knowledge Social Sciences 66%

- Essays Social Sciences 16%

- Content Social Sciences 16%

- Research Social Sciences 16%

- Schools Social Sciences 16%

- Materials Social Sciences 16%

T1 - Academic writing

AU - Firth, Miriam

PY - 2020/1/28

Y1 - 2020/1/28

N2 - Academic writing requires you to consider your understanding and position to publications on a topic. This is not simply regurgitating knowledge from reading sources, but offering your perspective on secondary material and an informed overview of current knowledge. Academic writing is unique in its content, form and structure. You may have written essays and reports at school or college which have previously been descriptive and fact based, but this chapter aims to develop your writing using the knowledge gained from academic sources and academic research. Using the previous chapters in academic development you should have found and read academic literature to develop your knowledge for an assignment. This chapter will appraise your ability to write about these sources and weave your authorial voice into the submission. Although this chapter focusses on academic styles of writing, it can also be used for professional and formal writing.

AB - Academic writing requires you to consider your understanding and position to publications on a topic. This is not simply regurgitating knowledge from reading sources, but offering your perspective on secondary material and an informed overview of current knowledge. Academic writing is unique in its content, form and structure. You may have written essays and reports at school or college which have previously been descriptive and fact based, but this chapter aims to develop your writing using the knowledge gained from academic sources and academic research. Using the previous chapters in academic development you should have found and read academic literature to develop your knowledge for an assignment. This chapter will appraise your ability to write about these sources and weave your authorial voice into the submission. Although this chapter focusses on academic styles of writing, it can also be used for professional and formal writing.

UR - https://www.mendeley.com/catalogue/c50ffaec-be18-3a18-9f85-f78a4aacd56b/

U2 - 10.4324/9781351026949-15

DO - 10.4324/9781351026949-15

M3 - Chapter

BT - Employability and Skills Handbook for Tourism, Hospitality and Events Students

A2 - Firth, Miriam

PB - Routledge

Alternatively, use our A–Z index

Academic skills

Our expert resources aim to develop key academic skills such as effective research, presentation skills, referencing and essay writing.

They are an excellent way to help students prepare for university-level study.

Primary and secondary

- Our partner, The Brilliant Club has online video presentations on a range of academic skills including essay writing, referencing. The resources are suitable for 10-14 year olds.

- You can access My Learning Essentials , an award-winning programme designed to improve academic skills.

- We have lots of useful advice about extended project writing , with tips on advanced academic writing to help prepare your students for university study.

- Our Library has resources for academic and research skills aimed at post-16 learners.

- The Essential Skills for Online Learning is a resource developed by the University Library to help students develop skills to get the most out of being an online learner.

Why study? talk series

Our PhD students have recorded talks on their specific subjects of interest which provide up-to-date information, advice and guidance to your students.

Student intranet

Study resources

Get the most out of studying Philosophy at Manchester.

Access online philosophy resources, get help with writing essays and other study skills, and join relevant societies and groups.

Study guides

See Blackboard Programme Hub

Online resources

A vast number of philosophical texts are available online. Once you know where to look and how to access them, they are an amazing resource for finding out more about a topic, locating journal articles that you need for your tutorials or essays or exams, seeing how a particular debate has played out in the literature, etc. This page gives you some information about how to use the internet for these purposes effectively.

Internet for Philosophy tutorial

Go to the University Library's Philosophy LibGuide . Click on the tabs along the top for lots of information about online journals and books, links to databases, etc. (You can also get to this site from the library home page by clicking on 'A-Z of subjects' under 'Academic Support' and searching for 'philosophy'. And you can download the guide onto your phone if you have a camera and bar code reader app.)

Now you've done both of those, you know pretty much everything you need to know about accessing philosophy resources on the internet! However, here are a few additional handy hints.

Accessing online philosophy articles

Library catalogue/Google Scholar

The vast majority of journal articles in philosophy can be accessed online through the University Library's subscriptions. The University Library's online catalogue includes journal articles, so you can search for a given article that way (you'll probably need to use 'advanced search' or you'll get too many hits).

A third option is to use Google Scholar. Just type the name of the journal article (in double quotation marks) and hit 'search'. If the article is available anywhere online, it should be first in the list of hits. Note that there will often be 'cited by' and 'related articles' links as well; if you click on these you'll be able to follow up the ensuing debate.

How do I log in to the publisher's website?

Some articles are freely available (often from the author's own homepage). However, normally they are only available through the journal publisher's website, and are accessible only to institutions that subscribe to the journal. UoM has a very extensive portfolio of subscriptions, so it's very likely that we have one. If you're going through the University Library's A-Z list of e-journals, you should be able to get straight through to the pdf of the article. If you're using Google Scholar, click on the link to the article or look for a 'Find it at UML' link on the right; again, you should be able to get to the pdf.

However if you're not using a campus computer you may find that your only apparent option is to buy the article. If this happens, look for the 'institutional login' button (there should be one somewhere on the page). Click on this and search for 'University of Manchester'. You should then be able to login using your normal UoM username and password, and be taken back to the journal site. (Annoyingly, it might not have remembered what it was you were looking for, so you might have to search the site for it.) If you can't find an 'institutional login' button, look for the link to login options. If there is a 'log in via Shibboleth' option, that will work too.

Or, even easier …

Set your off-campus computer/laptop up so that it can connect to the UoM 'Virtual Private Network' (VPN), by following the instructions . It's very easy! Once you've installed the VPN software, if you connect to the VPN your computer will act just like a campus computer, so you will automatically be logged in to publishers' journal sites and won't have to follow the institutional login procedure.

Top four online resources!

Well, it's a matter of subjective preference, but we can recommend:

- Philosophy Compass: This is an online journal that publishes high-quality survey articles on philosophical topics, aimed at non-specialists. Philosophy Compass articles are a great way of finding your way around a particular debate and locating relevant texts to follow up.

- PhilPapers: This is a huge database of philosophy books and journal articles. You can search for a particular item, browse the categories and sub-categories, and even make a personalised reading list or bibliography.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy : This is a really comprehensive online encyclopedia written by internationally recognised experts. It isn't written with undergraduates in particular in mind, but even if you don't understand everything you should be able to get a sense of the overall shape of the debate you're interested in, and there are lots of references for you to follow up. Please note that if you cite a SEP article in an essay, you need to cite and list it in your bibliography properly! Click on 'author and citation info' at the top of the article to find out how to cite it.

- Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy: UoM library now has access to this encyclopedia, which has over 2,700 philosophy articles. It includes comprehensive cross-referencing and is fully searchable. Off-campus, you will need to access it through the VPN .

Study skills and essay writing

Want to know how to write the perfect essay, how to deal with exam stress, or how to manage your study time more effectively? Then this is the page you need.

Philosophy study guide

You should already have this, but have you read it recently? It contains lots of useful and detailed information about how to write a good essay, how to prepare for exams, how to construct your bibliography and cite your sources, and lots of other things. A high proportion of students would get considerably better marks in their essays if they simply checked whether they were abiding by the Study Guide’s advice, so make sure you’re not one of them!

- Download the Philosophy study guide

In addition, you might buy or get from the library one or more of the following:

- Doing Philosophy , by C. Saunders, D. Lamb, D. Mossley and G. Macdonald Ross (ISBN 9781441173041, £14.99 or less; also available from the University Library) is a very helpful read, especially for new students. It’s a comprehensive guide to studying philosophy at university.

- The Basics of Essay Writing , by Nigel Warburton. This is a general guide to writing university-level essays, but it's written by a philosopher.

Bibliography and referencing guidance

From 2014-15, all students should consult only the guidelines contained in the Philosophy Study Guide when writing philosophy essays. In addition, we have adopted an official policy concerning how many marks should be deducted for various levels of failure to follow the guidelines. Read the student guidance on this policy .

More on essay writing

There's lots of additional advice online about how to write a good philosophy essay. Of course, philosophers across the planet don’t all agree with each other about exactly what makes for the perfect essay, and if you come across any advice that directly conflicts with the Study Guide, you should go with the Study Guide. But by and large we’re all looking for roughly the same thing, and one or more of these guides might be more helpful to you personally than our own Study Guide.

- Harvard Writing Centre’s A Guide to Philosophical Writing

- Richard Price’s Tips on How to Write a Philosophy Essay

- Jim Pryor’s Guidelines on Writing a Philosophy Paper

- Peter Lipton's advice on writing philosophy

- And last, but by no means least, there's Jimmy Lenman's 'How to Write a Crap Philosophy Essay'

There are loads more as well; just do a Google search for ‘how to write a philosophy essay’!

Advice on exams

Again, there's lots in the Philosophy Study Guide, but here's a spot of online advice:

- David Bain's exam revision tips

- Nigel Warburton's 5 tips on preparing for philosophy exams .

One-to-one help with your written English

The University Centre for Academic English offers a one-to-one tutorial service aimed at improving your written English. You can submit a sample of work in advance and will then have a meeting of up to an hour to discuss how to improve. If you're an overseas student, you can make an appointment yourself. If you're a home (UK) student you have to be referred, so please speak to your academic advisor. Find out more .

Using internet resources

Having trouble locating philosophy texts online? See the online resources section .

My Learning Essentials

The Library's award-winning skills programme contains lots of generic advice about managing your time, reflecting on your academic development, coping with exam stress, and so on.

- My Learning Essentials - The University of Manchester Library

In response to student feedback, we are making available some past essays to help you get a better sense of the kinds of things that we're looking for when we mark them.

To start with, there are two essays from last year's first-year Philosophy & Social Science course; but we'll be adding to these in due course. Please note, however, that what we're looking for is pretty much the same across all courses and levels (except, of course, that the higher the level, the higher the standard required). So you should find these useful even if you're not taking that particular course, and indeed even if you are a 2nd- or 3rd-year.

Included in each pdf is a short summary of the philosophical topic, a bunch of in-text comments, a summary of the essay's main strengths and weaknesses, and an indicative mark. Do please note that there is a lot more feedback on these essays than you can expect on the essays you submit! Our hope is that by providing very extensive feedback on a small sample of essays, you will be able to see how similar considerations might apply to your own work. Don't forget that if you want more feedback on an essay than the marker has provided on the essay itself, you can always go and see them in their office hours to ask for more advice on how to improve.

- 1st year sample essay 1 (Philosophy & Social Science) .

- 1st year sample essay 2 (Philosophy & Social Science) .

Societies and events

- The British Undergraduate Philosophy Society (BUPS) runs an annual conference and an online journal – The British Journal of Undergraduate Philosophy – both aimed at and run by philosophy undergraduates. If you’ve written a stormingly good essay you might think about submitting a version of it to the journal, or presenting it at the annual conference. Or you might think about getting involved in the society. These will help you improve at philosophy and look great on your CV!

- The University of Manchester Philosophy Society runs various events. Visit their Facebook group page .

- Philosophy@Manchester is the Facebook group for the Discipline Area. Take a look, and join up if you haven’t already!

Referencing guide at the University of Manchester: Home

- Harvard Manchester Updated

- American Psychological Association APA

- Modern Humanities Research Association MHRA

- Referencing Software

- EndNote online

Specialist Library Support

The Library provides expert support to students, staff and researchers in the specialist areas of business data, copyright, maths and statistics, referencing support, advanced searching and systematic reviews. This includes:

- Online resources

If you’ve tried our online resources and workshops and need more help, you can get expert help via our online help pages , attending a drop-in session, giving us a call or arranging a consultation.

What is referencing?

Referencing is a vital part of the academic writing process. It allows you to:

- acknowledge the contribution that other authors have made to the development of your arguments and concepts.

- inform your readers of the sources of quotations, theories, datasets etc that you've referred to, and enable them to find the sources quickly and easily themselves.

- demonstrate that you have understood particular concepts proposed by other writers while developing your own ideas.

- provide evidence of the depth and breadth of your own reading on a subject.

What is a reference list?

This is your list of all the sources that have been cited in the text of your work. The reference list includes all the books, e-books, journals, websites etc. in one list at the end of your document.

What is a bibliography?

The bibliography includes items which you have consulted for your work but not cited in the main body of your text. The list should appear at the end of your piece of work after the list of references. This demonstrates to the reader (examiner) the unused research you carried out.

Always check with your School if you need to produce a bibliography.

Word count and referencing

Generally, the word count of your work will include everything that is in the main text (citations, quotes, tables, lists etc) but will not include what is in the reference list/bibliography.

As always, you need to check the referencing advice given in your course handbook usually found in your Blackboard space, as rules can change from school to school.

- When to cite?

- How to cite?

- Citing secondary sources

Whenever you quote, paraphrase or make use of another person’s work in your own writing, you must indicate this in the body of your work (a citation) and provide full details of the source in a reference list (all the sources you have referred to directly in your work) or a bibliography (all the sources you have read in the course of your research, not just those you have cited).

Your reference list should include details of all the books, journal articles, websites and any other material you have used.

You do not need to reference:

- your own ideas and observations

- information regarded as ‘common knowledge’

- your conclusions (where you are pulling together ideas already discussed and cited in the main body of your work).

Understanding when to cite references is an important part of your academic progression.

The way that you cite references will depend on the referencing style you are using. There are many different referencing styles and you must ensure that you are following the appropriate style when submitting your work.

Getting started with referencing - is a MLE resource that explores the principles behind referencing, highlighting why it is good academic practice.

Check with your course handbook or supervisor to be sure that you are following the specific guidelines required by your school.

Commonly used referencing styles at The University of Manchester include Harvard, APA, MHLA, MLA and Vancouver.

These referencing pages will provide you with a useful introduction to the principles of referencing in various styles.

There are cases when an author discusses the research of another author in their work. When you are unable to track down the original research document you can cite them as a secondary source. In the citation include the (primary) source and where it was cited (secondary).

Only secondary cite when you cannot gain access to the primary source

In Harvard style: (Author, Date)

In-text citation:

Use either 'quoted in' or 'cited in' depending on the included detail.

Hirst places the importance of taste squarely at the feet of the regurgitated... (2016, cited in Stevenson, 2017).

"It is the regurgitated that I lay complete blame"... (2016, quoted in Stevenson, 2017).

For referencing purposes, only include the research you did consult because you did not read the original document and are taking any inference on the work from that author.

Stevenson, M. (2017). The genius in action: tales from the reference world , Oxford University Press: Oxford.

In Vancouver (numeric) style:

According to Hirst as cited in Stevenson (3) importance of taste is squarely at the feet of the regurgitated...

"It is the regurgitated that I lay complete blame"... Hirst quoted in Stevenson (3).

3. Stevenson, M. The genius in action: tales from the reference world. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2017.

Quote, paraphrase and summarise

There are several ways in which you may want to utilise other people’s ideas in order to add substance to your work. The most common ways to accomplish this are to quote, paraphrase or summarise.

When using quotations, remember to make sure they are relevant and thoughtfully used. Short and direct quotations provide the most succinct and direct way of conveying the ideas of others in support of your work.

- Use single quotation marks to indicate direct quotations and the definition of words.

- In quoted passages follow the original spelling, punctuation etc.

- Short quotations (usually less than 40 words) should be enclosed in single quotation marks (‘…’) and be part of the main text.

- Longer quotations should start on a separate line not italicised, with no quotation marks, and indented throughout.

- Double quotation marks (“…”) are used for a quote within a quote.

- Always include page numbers when using direct quotations to point the reader directly to the relevant point.

It is worth remembering that direct quotations count as part of your overall word count and excessive use can affect the flow of your work when reading.

Burroughs provides a great examples of the synthesis between the 'I' as author and the 'you' as reader 'You were not there for the beginning. You will not be there for the end. Your knowledge of what is going on can only be superficial and relative' (1959, p. 184)

Longer quotations should form their own paragraphs and be indented. Quotation marks are not a prerequisite when paragraphs and indentation are used.

Hirst describes the changes in societal landscape in his own inimitable way:

In a time of turbulent war and electrical fascination, rise a group of people with a different ideology to what had previously been commonplace. They became the new masters of their domain and the overlords of a world I no longer related to, nor understood. (Hirst, 2017, p. 1)

Non-English quotations should follow the same rules but always be displayed in the original source language.

Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is the expression of someone else’s thoughts or ideas in your own words. One of the benefits of this is that you can better describe the intentions of the author and your understanding, while maintaining your own writing style.

Although this is a way of manipulating text, you must not betray the original meaning of the author you are paraphrasing.

Original Text:

Paraphrased:

Hirst (2017, p. 1) discusses the turbulence of this era of war and the new onset of electrical fascination, he continues on the theme that these changes resulted in people becoming the owners of this new domain acting as overlords of a world he no could no longer fathom.

Summarising

When summarising, you condense in your own words the relevant points from materials such as books, articles, webpages etc.

Summarised:

Hirst (2017, p. 1) promulgates his feelings in relation to the turbulence of war and man's changing ideologies and his disenfranchised view of this new world landscape.

Additional online resources

Online resources:.

- EndNote desktop: getting started

- EndNote desktop: collecting references

- EndNote desktop: organising your references

- EndNote desktop: formatting your references

- EndNote desktop: YouTube playlist

- EndNote online: YouTube playlist

Other resources

- Introducing reference management tools

- EndNote desktop workbook for windows

- EndNote desktop workbook for MacOS

- EndNote online workbook

- Mendeley workbook

www.escholar.manchester.ac.uk/learning-objects/sls/packages/referencing/

My Learning Essentials

My Learning Essentials i s the Library’s programme of skills support, including both online resources and face-to-face workshops to help you in your personal and professional development. Workshops offer a relaxed group environment where you can try out new strategies while learning from and with peers. The online resources cover everything from referencing, to managing your procrastination, to writing a CV and you can access them through the Library website from wherever you are, whenever you need to!

Further help

The information contained within these pages is intended as a general referencing guideline.

Please check with your supervisor to ensure that you are following the specific guidelines required by your school.

- Next: Referencing Styles >>

- Last Updated: May 14, 2024 10:48 AM

- URL: https://subjects.library.manchester.ac.uk/referencing

University Centre for Academic English

Useful links

Explore the following websites for additional resources to aid in your learning.

JCU Study Skills Online

This site takes you through the process of writing from analysing a question to final editing. It also provides very useful sample essays with criteria for assessment and lecturers' comments.

- How to write essay guides

The Royal Literary Fund

Essay Writing: A Guide for Undergraduates. A useful and comprehensive guide to many different aspects of academic writing at this level.

- Writing Essays: A Guide

Victoria University of Wellington

A series of interactive exercises that focus on paragraph structure in academic writing.

- Writing exercises for self-directed study

Using English for Academic Purposes: A Guide for International Students

Comprehensive advice, materials and exercises on the four skills. Produced by Andy Gillett, Department of Modern Languages, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield.

- View the guide

Hong Kong Polytechnic University

This link to the Honk Kong Polytechnic University takes you firstly to a list of skills and functions associated with 'Essay Writing'. These include Explanation of Functions, Describing Trends, Cause and Effect for Developing Academic Writing Skills, and more. There are further useful categories such as Participating in Academic Discussions and Giving Oral Presentations. Follow this exercises link if you want to do some practice work on many of these.

- English for Academic Purposes

Randall's Cyber Listening Lab

Go down the page and try some of the "Listening Quizzes for Academic Purposes."

- Listening Quizzes

Academic Phrasebank

Giving examples.

- GENERAL LANGUAGE FUNCTIONS

- Being cautious

- Being critical

- Classifying and listing

- Compare and contrast

- Defining terms

- Describing trends

- Describing quantities

- Explaining causality

- Signalling transition

- Writing about the past

Writers may give specific examples as evidence to support their general claims or arguments. Examples can also be used to help the reader or listener understand unfamiliar or difficult concepts, and they tend to be easier to remember. For this reason, they are often used in teaching. Finally, students may be required to give examples in their work to demonstrate that they have understood a complex problem or concept. It is important to note that when statements are supported with examples, the explicit language signalling this may not always be used.

Examples as the main information in a sentence

A well-known example of this is … Another example of what is meant by X is … This is exemplified in the work undertaken by … This distinction is further exemplified in studies using … An example of this is the study carried out by Smith (2004) in which … The effectiveness of the X technique has been exemplified in a report by Smith et al. (2010)

This is evident in the case of … This is certainly true in the case of … The evidence of X can be clearly seen in the case of … In a similar case in America, Smith (1992) identified … This can be seen in the case of the two London physics laboratories which …

X is a good illustration of … X illustrates this point clearly. This can be illustrated briefly by … By way of illustration, Smith (2003) shows how the data for … These experiments illustrate that X and Y have distinct functions in …

For example, the word ‘doctor’ used to mean a ‘learned man’. For example, Smith and Jones (2004) conducted a series of semi-structured interviews in … Young people begin smoking for a variety of reasons. They may, for example, be influenced by ….

Examples as additional information

Young people begin smoking for a variety of reasons, such as pressure from peers or … The prices of resources, such as copper, iron ore, and aluminium, have declined over … Pavlov found that if a stimulus, for example the ringing of a bell, preceded the food, the … Many diseases can result at least in part from stress, including : arthritis, asthma, and migraine. Gassendi kept in close contact with many other scholars, such as Kepler, Galileo, Descartes, and …

Reporting cases as support

This case has shown that … This has been seen in the case of … The case reported here illustrates the … Overall, these cases support the view that … This case study confirms the importance of … The evidence presented thus far supports the idea that … This case demonstrates the need for better strategies for … As this case very clearly demonstrates, it is important that … This case reveals the need for further investigation in patients with … This case demonstrates how X used innovative marketing strategies in … Recent cases reported by Smith et al . (2013) also support the hypothesis that … In support of X, Y has been shown to induce Y in several cases (Smith et al ., 2001).

+44 (0) 161 306 6000

The University of Manchester Oxford Rd Manchester M13 9PL UK

Connect With Us

The University of Manchester

Academic Phrasebank Enhanced Version

Navigable PDF – 2023 Edition

The Academic Phrasebank is an essential writing resource for researchers, academics, and students. You can download the enhanced version of the Academic Phrasebank as a 158 page navigable PDF file here:

You can view sample pages of the enhanced PDF version by clicking on the icon below:

Enhanced PDF includes:

Hundreds more phrases, additional sections on:, writing abstracts, indicating shared knowledge, writing acknowledgements, written academic style, using gender-neutral language, british and us spelling, punctuation, sentence structure, paragraph structure, commonly confused words, phrases used to connect ideas, commonly used verbs.

Powered by WordPress / Academica WordPress Theme by WPZOOM

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Letter of Recommendation

What I’ve Learned From My Students’ College Essays

The genre is often maligned for being formulaic and melodramatic, but it’s more important than you think.

By Nell Freudenberger

Most high school seniors approach the college essay with dread. Either their upbringing hasn’t supplied them with several hundred words of adversity, or worse, they’re afraid that packaging the genuine trauma they’ve experienced is the only way to secure their future. The college counselor at the Brooklyn high school where I’m a writing tutor advises against trauma porn. “Keep it brief , ” she says, “and show how you rose above it.”

I started volunteering in New York City schools in my 20s, before I had kids of my own. At the time, I liked hanging out with teenagers, whom I sometimes had more interesting conversations with than I did my peers. Often I worked with students who spoke English as a second language or who used slang in their writing, and at first I was hung up on grammar. Should I correct any deviation from “standard English” to appeal to some Wizard of Oz behind the curtains of a college admissions office? Or should I encourage students to write the way they speak, in pursuit of an authentic voice, that most elusive of literary qualities?

In fact, I was missing the point. One of many lessons the students have taught me is to let the story dictate the voice of the essay. A few years ago, I worked with a boy who claimed to have nothing to write about. His life had been ordinary, he said; nothing had happened to him. I asked if he wanted to try writing about a family member, his favorite school subject, a summer job? He glanced at his phone, his posture and expression suggesting that he’d rather be anywhere but in front of a computer with me. “Hobbies?” I suggested, without much hope. He gave me a shy glance. “I like to box,” he said.

I’ve had this experience with reluctant writers again and again — when a topic clicks with a student, an essay can unfurl spontaneously. Of course the primary goal of a college essay is to help its author get an education that leads to a career. Changes in testing policies and financial aid have made applying to college more confusing than ever, but essays have remained basically the same. I would argue that they’re much more than an onerous task or rote exercise, and that unlike standardized tests they are infinitely variable and sometimes beautiful. College essays also provide an opportunity to learn precision, clarity and the process of working toward the truth through multiple revisions.

When a topic clicks with a student, an essay can unfurl spontaneously.

Even if writing doesn’t end up being fundamental to their future professions, students learn to choose language carefully and to be suspicious of the first words that come to mind. Especially now, as college students shoulder so much of the country’s ethical responsibility for war with their protest movement, essay writing teaches prospective students an increasingly urgent lesson: that choosing their own words over ready-made phrases is the only reliable way to ensure they’re thinking for themselves.

Teenagers are ideal writers for several reasons. They’re usually free of preconceptions about writing, and they tend not to use self-consciously ‘‘literary’’ language. They’re allergic to hypocrisy and are generally unfiltered: They overshare, ask personal questions and call you out for microaggressions as well as less egregious (but still mortifying) verbal errors, such as referring to weed as ‘‘pot.’’ Most important, they have yet to put down their best stories in a finished form.

I can imagine an essay taking a risk and distinguishing itself formally — a poem or a one-act play — but most kids use a more straightforward model: a hook followed by a narrative built around “small moments” that lead to a concluding lesson or aspiration for the future. I never get tired of working with students on these essays because each one is different, and the short, rigid form sometimes makes an emotional story even more powerful. Before I read Javier Zamora’s wrenching “Solito,” I worked with a student who had been transported by a coyote into the U.S. and was reunited with his mother in the parking lot of a big-box store. I don’t remember whether this essay focused on specific skills or coping mechanisms that he gained from his ordeal. I remember only the bliss of the parent-and-child reunion in that uninspiring setting. If I were making a case to an admissions officer, I would suggest that simply being able to convey that experience demonstrates the kind of resilience that any college should admire.

The essays that have stayed with me over the years don’t follow a pattern. There are some narratives on very predictable topics — living up to the expectations of immigrant parents, or suffering from depression in 2020 — that are moving because of the attention with which the student describes the experience. One girl determined to become an engineer while watching her father build furniture from scraps after work; a boy, grieving for his mother during lockdown, began taking pictures of the sky.

If, as Lorrie Moore said, “a short story is a love affair; a novel is a marriage,” what is a college essay? Every once in a while I sit down next to a student and start reading, and I have to suppress my excitement, because there on the Google Doc in front of me is a real writer’s voice. One of the first students I ever worked with wrote about falling in love with another girl in dance class, the absolute magic of watching her move and the terror in the conflict between her feelings and the instruction of her religious middle school. She made me think that college essays are less like love than limerence: one-sided, obsessive, idiosyncratic but profound, the first draft of the most personal story their writers will ever tell.

Nell Freudenberger’s novel “The Limits” was published by Knopf last month. She volunteers through the PEN America Writers in the Schools program.

- Search UNH.edu

- Search Hamel Center for Undergraduate Research

Commonly Searched Items:

- How to Begin

- Present and Publish

- Researchers

- Student Ambassadors

- Benefactors

- Research Experience and Apprenticeship Program (REAP)

- INCO 590 & INCO 790

- Undergraduate Research Awards (URA)

- Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowships (SURF)

- SURF for Interdisciplinary Teams (SURF IT)

- International Research Opportunities Program (IROP)

- Research Presentation Grants

- Application Deadlines

- Writing an Effective Research Proposal

- Student FAQs

- Responsible Conduct of Research

- Other Research Opportunities

- Faculty Mentor Eligibility

- Faculty Memos and Recommendation Forms

- Department Liaisons

- Faculty FAQs

- Grant Recipients

- Publications

- About the URC

- URC for Students

- URC for Faculty

- Attending the URC

A Survival Guide to Summer Research

Let’s face it. The idea of conducting research for the first time can be simultaneously one of the most terrifying and exciting prospects in one’s college career. Whether you plan to pursue a career in research and development, industry, or something completely different, the skills gained through undergraduate research are invaluable. But where do you start?

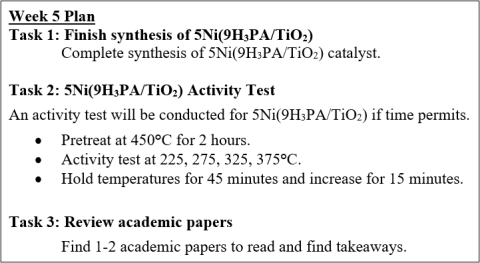

This is exactly what I was asking myself after my Research Experience and Apprenticeship Program (REAP) proposal was accepted last year. My project involved the conversion of carbon dioxide into methane through catalysis. My job was to synthesize different catalysts containing varying nickel, titanium dioxide, and varying weight percentages of heteropoly acids to determine its effect on increasing the amount of carbon dioxide converted. Despite having done hours of research to understand the topic enough to write a proposal essay, I still had some doubts about whether I was truly qualified. After completing my project, I can safely say that any similar thoughts you may be experiencing are unfounded. There were several things that made the learning curve much smoother for me. . While not required, these steps may be beneficial to keep in mind as you begin to embark on your own summer research experience.

Prior to research:

If commuting to campus, get a summer parking permit. It can provide peace of mind to not worry about getting a parking permit at the last second. There are also options for summer on-campus housing if that is preferred.

Clearly outline what your goals are. Depending on the type of research project, this could include minimum amounts of data collected, a certain number of experiments run, the hours you plan to work, etc. Ask your mentor what their expectations are to ensure your goals are aligned.

Create an organizational system. For me, this was one of the first times I had to juggle multiple projects simultaneously outside of school. This can quickly become overwhelming. It is important to organize your time and materials in a way that makes sense to you. For me, this involved a research folder for physical documents and a research computer file with Word documents and Excel sheets. Create backups of any files if possible.

Continue learning. Before your project begins, continue to educate yourself as much as possible on your topic of choice. The UNH library has countless databases filled with scholarly articles that likely align with your research topic. They may provide useful insight on how other professionals explore these ideas or what questions are pertinent.

During your research:

Now for the exciting part. Here are the practices I found most useful for efficient research.

Plan each week. This is a 10-week process. It can be very difficult to utilize your time effectively if you are figuring it out as you go. Once you have a solid understanding of the tasks you do, write down what you hope to accomplish before beginning each week.

This is an example from one of my own weekly plans. Even writing a simple plan made me more motivated to complete tasks. I also used a weekly planner to mark important dates, created folders on my computer to make files easy to retrieve, and backed up my files as much as possible. If you ever need to revisit your work months or years later, it is extremely helpful for it to have its own reliable spot.

Document everything. This goes along with planning to some degree, but write down everything you do, even if it seems inconsequential. There are several reasons for this. First, it will greatly help diagnosing errors if results do not make sense or do not meet expectations. When I was having a problem getting my catalyst to form properly, being able to review every step of the process was invaluable to determine the issue, which was slightly too much deionized water being added. Second, if your results are statistically significant, or if you publish your results, understanding exactly what you did to achieve certain results is crucial. Finally, it will assist with writing your project summary once your summer is complete.

Communication is key. If ever you feel stuck or have concerns about anything related to your project, express them to your mentor. No one expects you to solve every problem alone, and whether it be by email, zoom, or in person, mentors are usually happy to assist in any way they can.

Once your research experience is over:

Congratulations! Hopefully you found the process to be as valuable and rewarding as I did. Besides wrapping up final details, many opportunities can be built off your project if want to continue your work.

Tie up loose ends. While you write your research summary and polish any results, I recommend backing up files, organizing and digitalizing documents, and most importantly, thanking everyone who helped you along the process and expressing appreciation for the opportunity.

Consider publishing your research. Did you know the University of New Hampshire has a research journal? Inquiry is an excellent spot to complete the final step of research, which is publication. If written well, the research summary in your final report can be converted to a research brief with minimal work, or you may choose to undergo a longer writing and revision process to publish a full-length research article.

Update your resume and share your experience on LinkedIn. This project likely taught you countless invaluable skills that employers would love to see from prospective employees.

Hopefully these tips help you feel more confident throughout your summer and prove to be as useful as I found them. Anyone can conduct research and there are countless resources available to those ready to utilize them. Good luck and happy researching!

Hamel Center for Undergraduate Research

- URC Archives

- All Colleges Undergraduate Research Symposium

- COLSA Undergraduate Research Conference

- Interdisciplinary Science & Engineering Symposium (ISE)

- Naked Arts - Creativity Exposed!

- Paul College Undergraduate Research Conference

- UNH Manchester Undergraduate Research Conference

- Poster Printing Information & Pricing

- Faculty Mentoring 101

- Sustainability

- Embrace New Hampshire

- University News

- The Future of UNH

- Campus Locations

- Calendars & Events

- Directories

- Facts & Figures

- Academic Advising

- Colleges & Schools

- Degrees & Programs

- Undeclared Students

- Course Search

- Academic Calendar

- Study Abroad

- Career Services

- How to Apply

- Visit Campus

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Net Price Calculator

- Graduate Admissions

- UNH Franklin Pierce School of Law

- Housing & Residential Life

- Clubs & Organizations

- New Student Programs

- Student Support

- Fitness & Recreation

- Student Union

- Health & Wellness

- Student Life Leadership

- Sport Clubs

- UNH Wildcats

- Intramural Sports

- Campus Recreation

- Centers & Institutes

- Undergraduate Research

- Research Office

- Graduate Research

- FindScholars@UNH

- Business Partnerships with UNH

- Professional Development & Continuing Education

- Research and Technology at UNH

- Request Information

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni & Friends

Jump to navigation

Historical Fictions Research Conference, Manchester, 13th & 14th February 2025

The Historical Fictions Research Network (see https://historicalfictionsresearch.org/ ) aims to create a place for the discussion of all aspects of the construction of the historical narrative. The focus of the conference is the way we construct history, the narratives and fictions people assemble and how. We welcome both academic and practitioner presentations. The Network addresses a wide variety of disciplines, including Archaeology, Architecture, Art History, Cartography, Cultural Studies, Film Studies, Gaming, Gender, Geography, History, Larping, Linguistics, Literature, Media Studies, Memory Studies, Museum Studies, Musicology, Politics, Queer Studies, Race, Reception Studies, Re-enactment, Transformative Works.

For the 2025 conference, the HFRN seeks to engage in scholarly discussions on the topic of place in historical fictions.

As the geographer David Harvey points out, the construction of identities together with notions of belonging, power and freedom rest upon understandings of place. Perceived differences and affinities across and between populations, as well as over time, are often spatially determined, and because dreams of the future and imaginaries of the past are inevitably linked to space and territory, the historical imagination cannot be separated from the geographical. A sense of place underpins cultural memory and the imagined community of the nation through time. Conversely, as Paul Gilroy has shown, place is also crucial to the diasporic imagination, and it is moreover through re-visiting the relationship between place and time that alternative pasts can be imagined. Place is central to discourses around nostalgia, notions of golden ages, and the politics of home and belonging.

Place is integral to historical fictions as they attempt to reconstruct and re-present the ways and worlds of the past, helping to locate stories and characters in time and often conferring a sense of authenticity. Narratives of both progress and decline are usually anchored by location, and processes of change are often codified through the relationship between people and space. Place can be a device for exploring the otherness, the ‘horrors’ of the past. Alternatively, it can instil a sense of continuity and commonality between ages. Landscapes, including urban spaces are ‘storied’ and are, in the words of Paul Readman “‘sites of memory’ - focal points for mobilising a collective consciousness of the past”. As Readman goes on to point out, the association between place and human pasts transforms the former into heritage which in turn is bound up with constructions of collective identities. As Raymond Williams notes, different rural and urban environments, including that of the house, express social and moral values.

Places are thus political. They are often associated with conservative histories: with instincts of preservation, of stasis, and with property rights, inheritance, and the upholding of unequal social orders - ideas which, for instance, often under-pin the country-house narrative. At the same time, place can be used to posit new ways of looking at the past, to assert alternative geographical identities to that of the national and to awaken suppressed histories. As is shown by right-wing reactions to the British National Trust’s policy of revealing its properties’ economic roots, such perspectives offer radical possibilities, helping to re-centre the stories of marginalised communities and destabilise accepted norms and beliefs.

Papers are invited on topics related but not limited to:

- The meaning of landscapes and/or urban settings in historical fictions

- The use of mise-en-scène in historical film, TV or games

- Country-house historical fictions

- Nostalgia in historical fictions

- Diasporic historical fictions

- The use of settings in historical fictions

- The portrayal of travel in historical fictions

- The construction (or deconstruction) of place-based identities in historical fictions

- The reparative potential of place in historical fictions

- Post-national or transnational historical fictions

- Maps or other spatial paratexts in historical fictions

Keynote Speakers:

Dr Dorothea Flothow, Associate Professor, Department of English and American Studies, University of Salzburg

Professor Ian McGuire, American Literature and Creative Writing, University of Manchester and prize-winning author of the historical novels, The North Water (2016 ) and The Abstainer (2020)

Beth Underdown, author of the historical novels, The Witchfinder’s Sister (2017) and The Key in the Lock (2022)

Further Details

HFRC 2025 will be an in-person event taking place at Manchester Central Library, The Friends’ Meeting House, Manchester and The International Anthony Burgess Foundation, Manchester. All these venues are situated in the city centre. Piccadilly and Victoria Railway Stations are in the vicinity, and Manchester Airport is approximately 20 minutes away by train.

The organisers are Professor Jerome de Groot, University of Manchester, Dr Dorothea Flothow, University of Salzburg (Conference Manager), Dr Christine Lehnen, University of Exeter, Dr Siobhan O’Connor and Dr Paul Wake, Manchester Metropolitan University.

Proposals for 20-minute papers are due 28th June 2024 . They should consist of a title and an abstract of no more than 250 words. Panel proposals are also welcome. If you are proposing a panel, please provide a 700-word (maximum) description of the topic of the panel and the titles of individual papers; and for each participant the name, email address and brief statement (no more than 100 words) about the person’s work including relevant publications, presentations, or projects-in-progress. Panel proposals should be submitted by the organizer. Papers must be presented in English. Decisions on acceptance will be communicated by 31st July 2024 . Please use the form on our website to register your proposal:

Please note that a membership levy will be introduced alongside the conference fee this year. Further details about HFRN membership and its benefits will be shared at the conference.

References:

Gilroy, Paul, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness ( London: Verso, 1993)

Harvey, David, Cosmopolitanism and The Geographies of Freedom (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009)

Readman, Paul, Storied Ground: Landscape and the Shaping of English National Identity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018)

Williams, Raymond, The Country and The City (London: The Hogarth Press, 1993)

Visit our website ( https://historicalfictionsresearch.org/ ) for more details and regular updates. You can also write to HFRN conference manager, Dorothea Flothow at [email protected]

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Academic Phrasebank is a general resource for academic writers. It aims to provide you with examples of some of the phraseological 'nuts and bolts' of writing organised according to the main sections of a research paper or dissertation (see the top menu ). Other phrases are listed under the more general communicative functions of ...

He wants his students to "suck the marrow out of life", "to seize the day", and to make their lives "extraordinary". Keating teaches poetry, but his students get a lot more than that - they learn passion, courage, and romance. A group of his students dare to form the Dead Poets Society, a secret organization.

University Centre for Academic English. Writing and speaking Academic English can be challenging, even for native speakers. The University Centre for Academic English team of experienced tutors are here to support you, and will help boost your confidence to work independently in English through a series of interactive workshops.

Academic essays and articles usually contain 'references'. These can range from a generalised bibliography or list for "further reading" to specific references for particular points in the text. In this last category references are normally indexed either by the first author's name and publication date, e.g. " [Smith97]" or simply numerically ...

Academic Phrasebank. Explore Phrasebank, our general resource for academic writers, providing you with some of the phraseological 'nuts and bolts' of writing: Phrasebank (Open Access) Visit The University of Manchester Library's 'My Learning Essentials' page for tips on presenting: Presentations and Public Speaking.

Throughout the writing process, remember that your job as a writer is to help your reader to understand your ideas. If something does not aid understanding by contributing to your argument, it doesn't belong in your essay! For every section of your essay, you need to ensure that your writing is critical, and that it answers the question.

Appendix 5: A practical guide to writing essays . Writing an essay is a big task that will be easier to manage if you break it down into five main tasks as shown below: ... The Harvard style of referencing adopted at the University of Manchester will be covered in the Writing and Referencing Skills unit in Semester 3.

Abstract. Academic writing requires you to consider your understanding and position to publications on a topic. This is not simply regurgitating knowledge from reading sources, but offering your perspective on secondary material and an informed overview of current knowledge. Academic writing is unique in its content, form and structure.

Writing your essay - University of Manchester ... SUBMIT ALL

You can access My Learning Essentials, an award-winning programme designed to improve academic skills.; We have lots of useful advice about extended project writing, with tips on advanced academic writing to help prepare your students for university study.; Our Library has resources for academic and research skills aimed at post-16 learners.; The Essential Skills for Online Learning is a ...

Doing Philosophy, by C. Saunders, D. Lamb, D. Mossley and G. Macdonald Ross (ISBN 9781441173041, £14.99 or less; also available from the University Library) is a very helpful read, especially for new students. It's a comprehensive guide to studying philosophy at university. The Basics of Essay Writing, by Nigel Warburton. This is a general ...

Referencing is a vital part of the academic writing process. It allows you to: acknowledge the contribution that other authors have made to the development of your arguments and concepts. inform your readers of the sources of quotations, theories, datasets etc that you've referred to, and enable them to find the sources quickly and easily ...

This link to the Honk Kong Polytechnic University takes you firstly to a list of skills and functions associated with 'Essay Writing'. These include Explanation of Functions, Describing Trends, Cause and Effect for Developing Academic Writing Skills, and more. There are further useful categories such as Participating in Academic Discussions and ...

Preface. The Academic Phrasebank is a general resource for academic writers. It aims to provide the phraseological 'nuts and bolts' of academic writing organised according to the main sections of a research paper or dissertation. Other phrases are listed under the more general communicative functions of academic writing.

versus newspaper reporting on at least. First, draw a table like. two recent outbreaks of civil unrest. the one on the right. Then read through your. prompt and identify all. of the topics you need. to include. Finally, write each of.

Giving examples. Writers may give specific examples as evidence to support their general claims or arguments. Examples can also be used to help the reader or listener understand unfamiliar or difficult concepts, and they tend to be easier to remember. For this reason, they are often used in teaching. Finally, students may be required to give ...

When writing an essay, you are joining in an academic conversation. Remember that you are writing for your audience. The purpose of your writing is to communicate your ideas to a reader, and every word of your essay must contribute to that purpose. Your introduction should tell your reader what they should expect from your essay.

The Academic Phrasebank is an essential writing resource for researchers, academics, and students. ... This enhanced PDF version has been made available as a download with permission of the University of Manchester. The small charge for the PDF download helps to fund further work on the Academic Phrasebank. Enhanced PDF includes:

Most high school seniors approach the college essay with dread. Either their upbringing hasn't supplied them with several hundred words of adversity, or worse, they're afraid that packaging ...

Despite having done hours of research to understand the topic enough to write a proposal essay, I still had some doubts about whether I was truly qualified. After completing my project, I can safely say that any similar thoughts you may be experiencing are unfounded. There were several things that made the learning curve much smoother for me. .

The organisers are Professor Jerome de Groot, University of Manchester, Dr Dorothea Flothow, University of Salzburg (Conference Manager), Dr Christine Lehnen, University of Exeter, Dr Siobhan O'Connor and Dr Paul Wake, Manchester Metropolitan University. Proposals for 20-minute papers are due 28th June 2024. They should consist of a title and ...