Here's how COVID-19 affected education – and how we can get children’s learning back on track

Nearly 147 million children missed more than half of their in-person schooling between 2020 and 2022. Image: Unsplash/Taylor Flowe

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Douglas Broom

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Global Health is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, global health.

Listen to the article

- As well as its health impacts, COVID-19 had a huge effect on the education of children – but the full scale is only just starting to emerge.

- As pandemic lockdowns continue to shut schools, it’s clear the most vulnerable have suffered the most.

- Recovering the months of lost education must be a priority for all nations.

When the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 to be a pandemic on 11 March 2020, few could have foreseen the catastrophic effects the virus would have on the education of the world’s children.

During the first 12 months of the pandemic, lockdowns led to 1.5 billion students in 188 countries being unable to attend school in person, causing lasting effects on the education of an entire generation .

As an OECD report into the effects of school closures in 2021 put it: “Few groups are less vulnerable to the coronavirus than school children, but few groups have been more affected by the policy responses to contain the virus.”

Although many school closures were announced as temporary measures, these shutdowns persisted throughout 2020 – and even beyond in some cases.

As late as March 2022, UNICEF reported that 23 countries, home to around 405 million schoolchildren, had not yet fully reopened their schools . As China battled to contain new COVID-19 outbreaks, schools were closed in Shanghai and Xian in October 2022.

COVID has ended education for some

Nearly 147 million children missed more than half of their in-person schooling between 2020 and 2022, UNICEF says. And it warns that many, especially the most vulnerable, are at risk of dropping out of education altogether.

The danger is highlighted by UNICEF data showing that 43% of students did not return when schools in Liberia reopened in December 2020. The number of out-of-school children in South Africa tripled from 250,000 to 750,000 between March 2020 and July 2021, UNICEF adds.

When schools in Uganda reopened after being closed for two years, almost one in ten children were missing from classrooms. And in Malawi, the dropout rate among girls in secondary education increased by 48% between 2020 and 2021.

Out-of-school children are among the most vulnerable and marginalized children in society, says UNICEF. They are the least likely to be able to read, write or do basic maths, and when not in school they are at risk of exploitation and a lifetime of poverty and deprivation, it says.

Lost learning time

Even when children are in school, the amount of learning time they have lost to the pandemic is compounding what UNICEF describes as “a desperately poor level of learning” in 32 low-income countries it has studied.

“In the countries analyzed, the current pace of learning is so slow that it would take seven years for most schoolchildren to learn foundational reading skills that should have been grasped in two years, and 11 years to learn foundational numeracy skills,” the charity says.

Analysis of the crisis by UNESCO, published in November 2022, found that the most vulnerable learners have been hardest hit by the lack of schooling. It added that progress towards the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal for Education had been set back.

In Latin America and the Caribbean – a region that suffered one of the longest periods of school closures – average primary education scores in reading and maths could have slipped back to a level last seen 10 years ago , the World Bank says.

Four out of five sixth graders may not be able to adequately understand and interpret a text of moderate length, the bank says. As a result, these students are likely to earn 12% less over their lifetime than if their education had not been curtailed by the pandemic, it estimates.

Widening the achievement gap

In India, the pandemic has widened the gaps in learning outcomes among schoolchildren with those from disenfranchised and vulnerable families falling furthest behind, according to a 2022 report by the World Economic Forum.

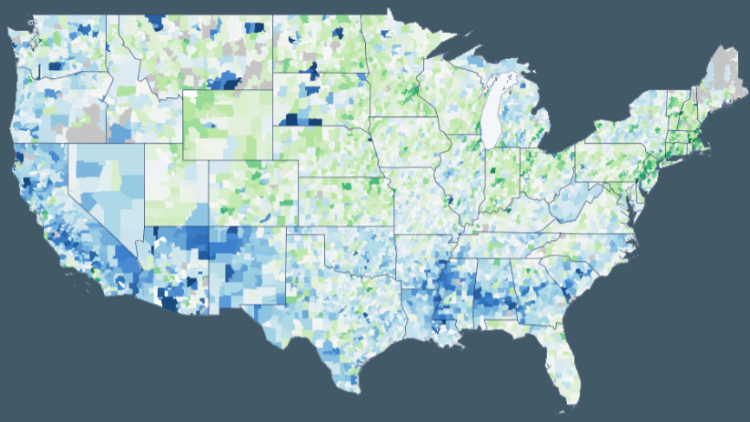

Even where schools tried to keep teaching using remote learning, the socio-economic divide was perpetuated. In the United States, a study found children’s achievement in maths fell by 50% more in less well-off areas , compared to those in more affluent neighbourhoods.

One year on: we look back at how the Forum’s networks have navigated the global response to COVID-19.

Using a multistakeholder approach, the Forum and its partners through its COVID Action Platform have provided countless solutions to navigate the COVID-19 pandemic worldwide, protecting lives and livelihoods.

Throughout 2020, along with launching its COVID Action Platform , the Forum and its Partners launched more than 40 initiatives in response to the pandemic.

The work continues. As one example, the COVID Response Alliance for Social Entrepreneurs is supporting 90,000 social entrepreneurs, with an impact on 1.4 billion people, working to serve the needs of excluded, marginalized and vulnerable groups in more than 190 countries.

Read more about the COVID-19 Tools Accelerator, our support of GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, the Coalition for Epidemics Preparedness and Innovations (CEPI), and the COVAX initiative and innovative approaches to solve the pandemic, like our Common Trust Network – aiming to help roll out a “digital passport” in our Impact Story .

Consultancy firm McKinsey says that US students were on average five months behind in mathematics and four months behind in reading by the end of the 2020-21 school year. Disadvantaged students were hit hardest, with Black students losing six months of learning on average.

Researchers in Japan found a similar pattern, with disadvantaged children and the youngest suffering most from school closures. They said the adverse effects of being forced to study at home lasted longest for those with poorest living conditions .

However, in Sweden, where schools stayed open during the pandemic, there was no decline in reading comprehension scores among children from all socio-economic groups, leading researchers to conclude that the shock of the pandemic alone did not affect students’ performance.

Getting learning back on track

So what can be done to help the pandemic generation to recover their lost learning ?

The World Bank outlines 10 actions countries can take, including getting schools to assess students’ learning loss and monitor their progress once they are back at school.

Catch-up education and measures to ensure that children don’t drop out of school will be essential, it says. These could include changing the school calendar, and amending the curriculum to focus on foundational skills.

There’s also a need to enhance learning opportunities at home, such as by distributing books and digital devices if possible. Supporting parents in this role is also critical, the bank says.

Teachers will also need extra help to avoid burnout, the bank notes. It highlights a “need to invest aggressively in teachers’ professional development and use technology to enhance their work”.

Have you read?

Covid-19 has hit children hard. here's how schools can help, how the education sector should respond to covid-19, according to these leading experts, covid created an education crisis that has pushed millions of children into ‘learning poverty’ -report, don't miss any update on this topic.

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Health and Healthcare Systems .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Improving workplace productivity requires a holistic approach to employee health and well-being

Susan Garfield, Ruma Bhargava and Eric Kostegan

May 30, 2024

This pioneering airspace management system can unleash the societal benefits of drone tech

Daniella Partem, Ofer Lapid and Ami Weisz

May 29, 2024

5 steps towards health equity in low- and middle-income countries through tailored innovation

Melanie Saville

The world must invest in oral health, plus other top health stories

Shyam Bishen

Why health ministers must be at the forefront of global healthcare processes

May 28, 2024

How AI, robotics and automation will reshape the diagnostic lab of the future

Ranga Sampath

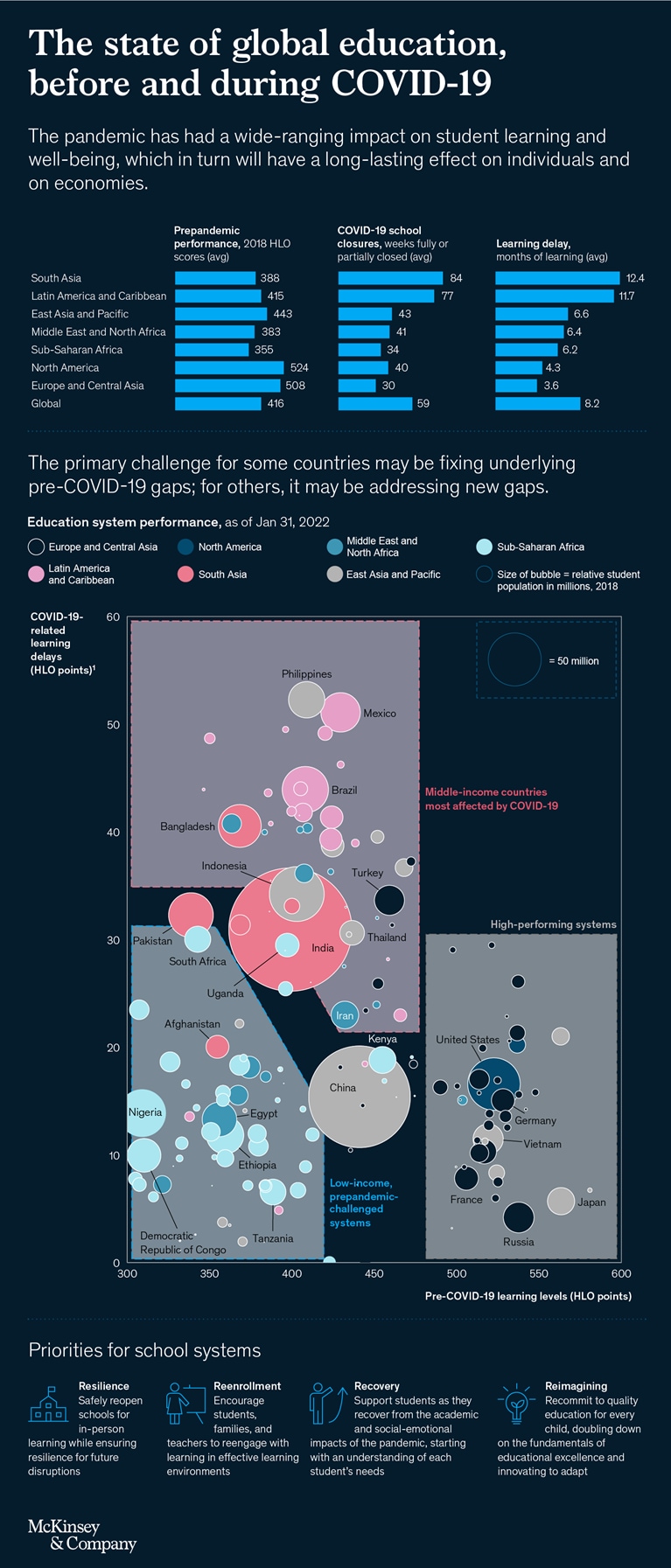

How COVID-19 caused a global learning crisis

Executive summary.

In our latest report on unfinished learning, we examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on student learning and well-being, and identify potential considerations for school systems as they support students in recovery and beyond. Our key findings include the following:

- The length of school closures varied widely across the world. School buildings in middle-income Latin America and South Asia were fully or partially closed the longest—for 75 weeks or more. Those in high-income Europe and Central Asia were fully or partially closed for less time (30 weeks on average), as were those in low-income sub-Saharan Africa (34 weeks on average).

About the authors

This article is a collaborative effort by Jake Bryant , Felipe Child , Emma Dorn , Jose Espinosa, Stephen Hall , Topsy Kola-Oyeneyin , Cheryl Lim, Frédéric Panier, Jimmy Sarakatsannis , Dirk Schmautzer , Seckin Ungur , and Bart Woord, representing views from McKinsey’s Education Practice.

- Access to quality remote and hybrid learning also varied both across and within countries. In Tanzania, while school buildings were closed, children in just 6 percent of households listened to radio lessons, 5 percent accessed TV lessons, and fewer than 1 percent participated in online learning. 1 Jacobus Cilliers and Shardul Oza, “What did children do during school closures? Insights from a parent survey in Tanzania,” Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE), May 19, 2021.

- Furthermore, pandemic-related learning delays stack up on top of historical learning inequities. The World Bank estimates that while students in high-income countries gained an average of 50 harmonized learning outcomes (HLO) points a year prepandemic, students in low-income countries were gaining just 20, leaving those students several years behind. 2 Noam Angrist et al., “Measuring human capital using global learning data,” Nature , March 2021, Volume 592.

- High-performing systems, with relatively high levels of pre-COVID-19 performance, where students may be about one to five months behind due to the pandemic (for example, North America and Europe, where students are, on average, four months behind).

- Low-income prepandemic-challenged systems, with very low levels of pre-COVID-19 learning, where students may be about three to eight months behind due to the pandemic (for example, sub-Saharan Africa, where students are on average six months behind).

- Pandemic-affected middle-income systems, with moderate levels of pre-COVID-19 learning, where students may be nine to 15 months behind (for example, Latin America and South Asia, where students are, on average, 12 months behind).

- The pandemic also increased inequalities within systems. For example, it widened gaps between majority Black and majority White schools in the United States and increased preexisting urban-rural divides in Ethiopia.

- Beyond learning, the pandemic has had broader social and emotional impacts on students globally—with rising mental-health concerns, reports of violence against children, rising obesity, increases in teenage pregnancy, and rising levels of chronic absenteeism and dropouts.

- Lower levels of learning translate into lower future earnings potential for students and lower economic productivity for nations. By 2040, the economic impact of pandemic-related learning delays could lead to annual losses of $1.6 trillion worldwide, or 0.9 percent of total global GDP.

- Resilience: Safely reopen schools for in-person learning while ensuring resilience for future disruptions.

- Reenrollment: Encourage students, families, and teachers to reengage with learning in effective learning environments.

- Recovery: Support students as they recover from the academic and social-emotional impacts of the pandemic, starting with an understanding of each student’s needs.

- Reimagining: Recommit to quality education for every child, doubling down on the fundamentals of educational excellence and innovating to adapt.

In some parts of the world, students, parents, and teachers may be experiencing a novel feeling: cautious optimism. After two years of disruptions from COVID-19, the overnight shift to online and hybrid learning, and efforts to safeguard teachers, administrators, and students, cities and countries are seeing the first signs of the next normal. Masks are coming off. Events are being held in person. Extracurricular activities are back in full swing.

These signs of hope are counterbalanced by the lingering, widespread impact of the pandemic. While it’s too early to catalog all of the ways students have been affected, we are starting to see initial indications of the toll COVID-19 has taken on learning around the world. Our analysis of available data found no country was untouched, but the impact varied across regions and within countries. Even in places with effective school systems and near-universal connectivity and device access, learning delays were significant, especially for historically vulnerable populations. 3 Emma Dorn, Bryan Hancock, Jimmy Sarakatsannis, and Ellen Viruleg, “ COVID-19 and education: An emerging K-shaped recovery ,” McKinsey, December 14, 2021. In many countries that had poor education outcomes before the pandemic, the setbacks were even greater. In those countries, an even more ambitious, coordinated effort will likely be required to address the disruption students have experienced.

Our analysis highlights the extent of the challenge and demonstrates how the impact of the pandemic on learning extends across students, families, and entire communities. Beyond the direct effect on students, learning delays have the potential to affect economic growth: by 2040, according to McKinsey analysis, COVID-19-related unfinished learning could translate into $1.6 trillion in annual losses to the global economy.

Acting decisively in the near term could help to address learning delays as well as the broader social, emotional, and mental-health impact on students. In mobilizing to respond to the pandemic’s effect on student learning and thriving, countries also may need to reassess their education systems—what has been working well and what may need to be reimagined in light of the past two years. Our hope is that this article’s analysis provides a potential starting point for dialogue as nations seek to reinvigorate their education systems.

Gauging the pandemic’s widespread impact on education

One of the challenges in assessing the global effect of the pandemic on learning is the lack of data. Comparative international assessments mostly cover middle- to high-income countries and have not been carried out since the beginning of the pandemic. The next Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), for example, was delayed until 2022. 4 “PISA,” OECD, accessed March 30, 2022. Similarly, many countries had to cancel or defer national assessments. As a result, few nations have a complete data set, and many have no assessment data to indicate relative learning before and since school closures. Accordingly, our methodology used available data augmented by informed assumptions to get a directional picture of the pandemic’s effects on the scholastic achievement and well-being of students.

The pandemic’s impact on student learning

We evaluated the potential effect of the pandemic on student learning by multiplying the amount of time school was disrupted in each country by the estimated effectiveness of the schooling students received during disruptions.

The duration of school closures ran the gamut. During the 102-week period we studied (from the onset of COVID-19 to January 2022), school buildings in Latin America, including the Caribbean, and South Asia were fully or partially closed for 75 weeks or more, while those in Europe and Central Asia were fully or partially closed for an average of 30 weeks (Exhibit 1). Schools in some regions began reopening a few months into the pandemic, but as of January 2022, more than a quarter of the world’s student population resided in school systems where schools were not yet fully open.

Remote and hybrid learning similarly varied widely across and within countries. Some students were supported by internet access, devices, learning management systems, adaptive learning software, live videoconferencing with teachers and peers, and home environments with parents or hired professionals to support remote learning. Others had access to radio or television programs, paper packages, and text messaging. Some students may not have had access to any learning options. 5 What’s next? Lessons on education recovery: Findings from a survey of ministries of education amid the COVID-19 pandemic , UNESCO, UNICEF, the World Bank, and OECD, June 2021. We used the World Bank’s estimates on “mitigation effectiveness” by country income level to account for different levels of access to learning tools and quality through the pandemic (see the forthcoming methodological appendix for more details).

Our model suggests that in the first 23 months since the start of the pandemic, students around the world may have lost about eight months of learning, on average, with meaningful disparities across and within regions and countries. For example, students in South Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean may be more than a year behind where they would have been absent the pandemic. In North America and Europe, students might be an average of four months behind (Exhibit 2).

The regional numbers only begin to tell the full story. The greater the range of school system performance and resources across regions, the greater the variation in student experiences. Students in Japan and Australia may be less than two months behind, while students in the Philippines and Indonesia may be more than a year behind where they would have been (Exhibit 3).

Within countries, the impact of COVID-19 has also affected individual students differently. Wherever assessments have taken place since the onset of the pandemic, they suggest widening gaps in both opportunity and achievement. Historically vulnerable and marginalized students are at an increased risk of falling further behind.

In the United States, students in majority Black schools were half a year behind in mathematics and reading by fall 2021, while students in majority White schools were just two months behind. 6 “ COVID-19 and education: An emerging K-shaped recovery ,” December 14, 2021. In Ethiopia, students in rural areas achieved under one-third of the expected learning from March to October 2020, while those in urban areas learned less than half of the expected amount. 7 Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) , “Learning inequalities widen following COVID-19 school closures in Ethiopia,” blog entry by Janice Kim, Pauline Rose, Ricardo Sabates, Dawit Tibebu Tiruneh, and Tassew Woldehanna, May 4, 2021. Assessments in New South Wales, Australia, detected minimal impact on learning overall, but third-grade students in the most disadvantaged schools experienced two months less growth in mathematics. 8 Leanne Fray et al., “The impact of COVID-19 on student learning in New South Wales primary schools: An empirical study,” The Australian Educational Researcher , 2021, Volume 48.

Would you like to learn more about our Education Practice ?

Covid-19-related losses on top of historical inequalities.

The learning crisis is not new. In the years before COVID-19, many school systems faced challenges in providing learning opportunities for many of their students. The World Bank estimates that before the pandemic, more than half of students in low- and middle-income countries were living in “learning poverty”—unable to read and understand a simple text by age ten. That number may rise as high as 70 percent due to pandemic-related school disruptions. 9 Joao Azevedo et al., “The state of the global education crisis: A path to recovery,” World Bank Group, December 3, 2021.

The World Bank’s harmonized learning outcomes (HLOs) compare learning achievement and growth across countries. This measure combines multiple global student assessments into one metric, with a range of 625 for advanced attainment and 300 for minimum attainment. According to the World Bank’s 2018 HLO database, students from some countries in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia were several years behind their counterparts in North America and Europe before the pandemic (Exhibit 4). 10 Data Blog , “Harmonized learning outcomes: transforming learning assessment data into national education policy reforms,” blog entry by Harry A. Patrinos and Noam Angrist, August 12, 2019.

Students in these countries were also progressing more slowly each year in school. While students in high-income countries may have been gaining 50 HLO points in a year, students in low-income countries were gaining just 20. In other words, not much learning was happening in some countries even before the pandemic.

Prepandemic learning levels and pandemic-related learning delays interacted in different ways in different countries and regions. Although each country is unique, three archetypes emerge based on the performance of education systems (Exhibit 5).

High-performing systems. Countries in this archetype generally had higher pre-COVID-19 learning levels. Systems had more capacity for remote learning, and school buildings remained closed for shorter time periods. 11 “Education: From disruption to recovery,” UNESCO, accessed March 11, 2022. Data suggest that after the initial shock of the pandemic in 2020, learning delays increased only moderately with subsequent school closures in the 2021–22 school year. Some high-income countries seem to show little evidence of decreased learning overall. According to the Australian National Assessment Program–Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN), the COVID-19 pandemic did not have a statistically significant impact on average student literacy and numeracy levels, even in Victoria, where learning was remote for more than 120 days. 12 “Highlights from Victorian preliminary results in NAPLAN 2021,” Victoria state government, August 26, 2021; Adam Carey, Melissa Cunningham, and Anna Prytz, “‘Children have suffered enormously’: School closures leave experts divided,” The Age , Melbourne, July 25, 2021. However, in many high-income countries, the impact of the pandemic on learning remained significant. Assessments of student learning in the United States in fall 2021 suggested students had fallen four months behind in mathematics and three months behind in reading. 13 “ COVID-19 and education: An emerging K-shaped recovery ,” December 14, 2021. Inequalities in learning also increased within many of these countries, with historically marginalized students most affected.

Lower-income, prepandemic-challenged systems. This archetype consists of mostly low-income and lower-middle-income countries with very low levels of pre-COVID-19 learning. When the pandemic struck, school buildings closed for varying periods of time, 14 “Education: From disruption to recovery,” UNESCO, accessed March 11, 2022. with limited options for remote learning. In Tanzania, for example, schools were closed for 15 weeks, and during this period, just 6 percent of households reported that their children listened to radio lessons, 5 percent watched TV lessons, and fewer than 1 percent accessed educational programs on the internet. 15 Jacobus Cilliers and Shardul Oza, “What did children do during school closures? Insights from a parent survey in Tanzania,” Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE), May 19, 2021. Across the analyzed time period, schools in sub-Saharan Africa were fully open for more weeks, on average, than schools in any other region. As a result, the pandemic’s impact on learning was relatively muted, even though many of these systems faced challenges with effective remote learning. 16 A report of six countries in Africa, for example, found limited impact of the pandemic on already-low student outcomes. For more information, see “MILO: Monitoring impacts on learning outcomes,” UNESCO, accessed March 11, 2022.

These relatively smaller pandemic learning delays are likely due in part to the limited progress students were making in schools before COVID-19. 17 World Bank blogs , “Harmonized learning outcomes: Transforming learning assessment data into national education policy reforms,” blog entry by Harry A. Patrinos and Noam Angrist, August 12, 2019. If students weren’t progressing scholastically when schools were open, closures were likely to have less impact. In Tanzania before the pandemic, three-quarters of students in grade three could not read a basic sentence. 18 “What did children do during school closures?,” May 19, 2021.

Pandemic-affected middle-income systems. School systems in Latin American and South Asian countries had low to moderate performance before COVID-19. Many middle-income countries in this group did have some capacity to plan and roll out remote-learning options, especially in urban areas. 19 “Responses to Educational Disruption Survey (REDS),” UNESCO, accessed March 11, 2022. However, pandemic-related disruptions caused widespread school closures for extended periods of time—more than 50 weeks in some countries. 20 “Education: From disruption to recovery,” UNESCO, accessed March 11, 2022. The resulting learning delays may represent a true crisis for major economies such as India, Indonesia, and Mexico, where students are more than a year behind, on average.

While some students may have just learned more slowly than they would have absent the pandemic, others in this archetype may have actually slipped backward. A study by the Azim Premji Foundation suggests that as early as January 2021, more than 90 percent of students assessed in India have lost at least one language ability (such as reading words or writing simple sentences), while more than 80 percent lost a math ability (for example, identifying single- and double-digit numbers or naming shapes). 21 Loss of learning during the pandemic , Azim Premji Foundation, February 2021. This pattern could be particularly challenging, since higher-order skills are increasingly important in middle-income countries with rising levels of workplace automation. McKinsey’s “ Jobs lost, jobs gained ” report 22 For more information, see “ Jobs lost, jobs gained: What the future of work will mean for jobs, skills, and wages ,” McKinsey Global Institute, November 28, 2017. suggests India may need 34 million to 100 million more high school graduates by 2030 to fill workplace demands. The pandemic has put existing high school graduation rates at risk, let alone the vast expansion required to meet future demand for workers.

The pandemic’s effects beyond learning

Much of the dialogue around school systems focuses on educational achievement, but schools offer more than academic instruction. A school system’s contributions may include social interaction; an opportunity for students to build relationships with caring adults; a base for extracurricular activities, from the arts to athletics; an access point for physical- and mental-health services; and a guarantee of balanced meals on a regular basis. The school year may also enable students to track their progress and celebrate milestones. When schools had to close for extended periods of time or move to hybrid learning, students were deprived of many of these benefits.

The pandemic’s impact on the social-emotional and mental and physical health of students has been measured even less than its impact on academic achievement, but early indications are concerning. Save the Children reports that 83 percent of children and 89 percent of parents globally have reported an increase in negative feelings since the pandemic began. 23 The hidden impact of COVID-19 on child protection and wellbeing , Save the Children International, September 2020. In the United States, one in three parents said they were very or extremely worried about their child’s mental health in spring 2021, with rising reported levels of student anxiety, depression, social withdrawal, and lethargy. 24 Emma Dorn, Bryan Hancock, Jimmy Sarakatsannis, and Ellen Viruleg, “ COVID-19 and education: The lingering effects of unfinished learning ,” McKinsey, July 27, 2021. Parents of Black and Hispanic students, the segments most affected by academic unfinished learning, also reported higher rates of concern about their student’s mental health and engagement with school. A UK survey found 53 percent of girls and 44 percent of boys aged 13 to 18 had experienced symptoms or trauma related to COVID-19. 25 Report1: Impact of COVID-19 on young people aged 13-24 in the UK- preliminary findings , PsyArXiv, January 20, 2021. In Bangladesh, a cross-sectional study revealed that 19.3 percent of children suffered moderate mental-health impacts, while 7.2 percent suffered from extreme mental-health effects. 26 Rajon Banik et al., “Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of children in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study,” Children and Youth Services Review , October 2020, Volume 117. Reports of violence against children rose in many countries. 27 “Publications,” Young Lives, accessed March 22, 2022. The pandemic affected physical health as well. Studies from the United States 28 Roger Riddell, “CDC: Child obesity jumped during COVID-19 pandemic,” K-12 Dive , September 24, 2021. and the United Kingdom 29 The annual report of Her Majesty’s chief inspector of education, children’s services and skills 2020/21 , Ofsted, December 7, 2021. show rising rates of childhood obesity. In Latin America and the Caribbean, more than 80 million children stopped receiving hot meals. 30 “We can move to online learning, but not online eating,” United Nations World Food Program, March 26, 2020. In Uganda, a record number of monthly teenage pregnancies—more than 32,000—were recorded from March 2020 to September 2021. 31 “Uganda overwhelmed by 32,000 monthly teen pregnancies,” Yeni Şafak , December 12, 2021.

Some students may never return to formal schooling at all. Even in high-income systems, levels of chronic absenteeism are rising, and some students have not reengaged in school. In the United States, 1.7 million to 3.3 million eighth to 12th graders may drop out of school because of the pandemic. In low- and middle-income countries, the situation could be far worse. Up to one-third of Ugandan students may not return to the classroom. This pattern is in line with past historical crises involving school closures. After the Ebola pandemic, 13 percent of students in Sierra Leone and 25 percent of students in Liberia dropped out of school, with girls and low-income students most affected. 32 The socio-economic impacts of Ebola in Liberia , World Bank, April 15, 2015; The socio-economic impacts of Ebola in Sierra Leone , World Bank, June 15, 2015. Among the poorest primary-school students in Sierra Leone, dropout rates increased by more than 60 percent. 33 William C. Smith, “Consequences of school closure on access to education: Lessons from the 2013-2016 Ebola pandemic,” International Review of Education , April 2021, Volume 67. This may result in reduced employment opportunities and lifelong earnings potential for many of these students.

The potential of long-term economic damage

Education can affect not just an individual’s future earnings and well-being but also a country’s economic growth and vitality. Research suggests higher levels of education lead to increased labor productivity and enhance an economy’s capacity for innovation. Unless the pandemic’s impact on student learning can be mitigated and students can be supported to catch up on missed learning, the global economy could experience lower GDP growth over the lifetime of this generation.

We estimate by 2040, unfinished learning related to COVID-19 could translate to annual losses of $1.6 trillion to the global economy, or 0.9 percent of predicted total GDP (Exhibit 6).

Although the total dollar amount of forgone GDP is highest in the largest economies of the world (encompassing East Asia, Europe, and North America), the relative impact is highest in regions with the greatest learning delays. In Latin America and the Caribbean, pandemic-related school closures could result in losses of more than 2 percent of GDP annually by 2040 and in subsequent years.

Economic impact could be affected further if students don’t return to school and cease learning altogether.

Identifying potential solutions

The response to the learning crisis will likely vary from country to country, based upon preexisting educational performance, the depth and breadth of learning delays, and system resources and capacity to respond. That said, all school systems will likely need to plan across multiple horizons:

As 2022 began, more than 95 percent of school systems around the world were at least partially open for traditional in-person learning. 34 “Responses to Educational Disruption Survey (REDS),” UNESCO, 2022, accessed March 11, 2022. That progress is encouraging but tenuous. Many systems reopened only to close down again when another wave of COVID-19 caused additional disruptions. Even within partially open systems, not all students have access to in-person learning, and many are still attending partial days or weeks. Building resilience could mean ensuring protocols are in place for safe and supportive in-person learning, and ensuring plans are in place to provide remote options that support the whole child at the system, school, and student levels in response to future crises. School systems can also benefit by creating the flexibility to change policies and procedures as new data and circumstances arise.

COVID-19 and education: The lingering effects of unfinished learning

Reenrollment.

Opening buildings and embedding effective safety precautions have been challenging for many systems, but ensuring students and teachers actually turn up and reengage with learning is perhaps even more difficult. Even where in-person learning has resumed, many students have not returned or remain chronically absent. 35 Indira Dammu, Hailly T.N. Korman, and Bonnie O’Keefe, Missing in the margins 2021: Revisiting the COVID-19 attendance crisis , Bellwether Education Partners, October 21, 2021. Families may still have safety worries about in-person learning. Some students may have found jobs and now rely on that income. 36 Elias Biryabarema, “Student joy, dropout heartache as Uganda reopens schools after long COVID-19 shutdown,” Reuters, January 10, 2022. Others may have become pregnant or now act as caregivers at home. 37 Brookings Education Plus Development , “What do we know about the effects of COVID-19 on girls’ return to school?,” blog entry by Erin Ganju, Christina Kwauk, and Dana Schmidt, September 22, 2021. Still others may feel so far behind academically or so disconnected from the school environment at a social level that a return feels impossible. A multipronged approach could be helpful to understand the barriers students may face, how those could differ across student segments, and ways to support all students in continuing their educational journeys.

Systems could consider a tiered approach to support reengagement. Tier-one interventions could be rolled out for all students and include both improving school offerings for families and students and communicating about enhanced services. This might involve back-to-school awareness campaigns at the national and community levels featuring respected community members, clear communication of safety protocols, access to free food and other basic needs on campuses, and the promotion of a positive school climate with deep family engagement.

Tier-two interventions, which could be directed at students who are at heightened risk of not returning to school, may involve more targeted support. These efforts might include community events and canvassing to bring school buses or mobile libraries to historically marginalized neighborhoods, phone- or text-banking aimed at students who have not returned to school, or summer opportunities (including fun reorientation activities) to convince students to return to the school campus. At the student level, it could include providing some groups of students with deeper learning or social-emotional recovery services to help them reintegrate into school.

Tier-three interventions encompass more intensive and specialized support. These efforts may include visits to the homes of individual students or new educational environments tailored to student needs—for example, night schools for students who need to complete high school while working.

Once students are back in school, many may need support to recover from the academic and social-emotional effects of the pandemic. Indeed, while academic recovery seems daunting, supporting the mental-health and social-emotional needs of students may end up being the bigger challenge. 38 Protecting youth mental health: The U.S. surgeon general’s advisory , U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2021. This process starts with a recognition that each child is unique and that the pandemic has affected different students in different ways. Understanding each student’s situation, in terms of both learning and well-being, is important at the classroom level, with teachers and administrators trained to interpret cues from students and refer them to more intensive support when necessary. Assessments will likely also be needed at the school and system levels to plan the response.

With an understanding of both the depth and breadth of student needs, systems and schools could consider three levers of academic acceleration: more time, more dedicated attention, and more focused content. Implementation of these levers will likely vary by context, but the overall goals are the same: to overcome both historical gaps and new COVID-19-related losses, and to do so across academic and whole-child indicators.

In high-income countries, digital formative assessments could help determine in real time what students know, where they may have gaps, and what the next step could be for each child. More relational tactics can be incorporated alongside digital assessments, such as teachers taking the time to connect with each child around a simple reading assessment, which may rebuild relationships and connectivity while assessing student capabilities. Schools could also consider universal mental-health diagnostics and screeners, and train teachers and staff to recognize the signs of trauma in students.

Once schools have identified students who need academic support, proven, evidence-based solutions could support acceleration in high-income school systems. High-dosage tutoring, for example, could enable students to learn one to two additional years of mathematics in a single year. Delivered three to five times a week by trained college graduates during the school day on top of regular math instruction, this type of tutoring is labor and capital intensive but has a high return on investment. Acceleration academies, which provide 25 hours of targeted instruction in reading to small groups of eight to 12 students during vacations, have helped students gain three months of reading in just one week. Exposing students to grade-level content and providing them with targeted supports and scaffolds to access this content has improved course completion rates by two to four times over traditional “re-teaching” remediation approaches.

With an understanding of both the depth and breadth of student needs, systems and schools could consider three levers of academic acceleration: more time, more dedicated attention, and more focused content.

In low- and middle-income countries, where learning delays may have been much greater and where the financial and human-capital resources for education can be more limited, different implementation approaches may be required. Simple, fast, inexpensive, and low-stakes evaluations of student learning could be carried out at the classroom level using pen and paper, oral assessments, and mobile data collection, for example.

Solutions for supporting the acceleration of student learning in these contexts could start with ensuring foundational literacy and numeracy (FLN), prioritizing essential standards and content. Evidence-based teaching methods could speed up learning; for example, Pratham’s Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) approach—which groups children by learning needs, rather than by age or grade, and dedicates time to basic skills with continual reassessment—has led to improvements of more than a year of learning in classrooms and summer camps. 39 Improvements of 0.2 to 0.7 standard deviations; assuming that one year of learning ranges from 0.2 of a standard deviation in low income countries and 0.5 of a standard deviation in high income countries, in accordance with World Bank assumptions:; João Pedro Azevedo et al., Simulating the potential impacts of COVID-19 school closures on schooling and learning outcomes , World Bank working paper 9284, June 2020; David K. Evans and Fei Yuan, Equivalent years of schooling , World Bank working paper 8752, February 2019. Even with the application of existing approaches, more time in class may be required—with options to extend the school year or school day to support students. Widespread tutoring may not be realistic in some countries, but peer-to-peer tutoring and cross-grade mentoring and coaching could supplement in-class efforts. 40 COVID-19 response–remediation: Helping students catch up on lost learning, with a focus on closing equity gaps , UNESCO, July 2020.

Reimagining

In addition to accelerating learning in the short term, systems can also use this moment to consider how to build better systems for the future. This may involve both recommitting to the core fundamentals of educational excellence and reimagining elements of instruction, teaching, and leadership for a post-COVID-19 world. 41 Jake Bryant, Emma Dorn, Stephen Hall, and Frédéric Panier, “ Reimagining a more equitable and resilient K-12 education system ,” McKinsey, September 8, 2020. A lot of ground could be covered by rolling out existing evidence-based interventions at scale—recommitting to core literacy and numeracy skills, high-quality instructional materials, job-embedded teacher coaching, and effective performance management. Recommitting to these basics, however, may not be enough. Systems can also innovate across multiple dimensions: providing whole-child supports, using technology to improve access and quality, moving toward competency-based learning, and rethinking teacher preparation and roles, school structures, and resource allocation.

For example, many systems are reemphasizing the importance of caring for the whole child. Integrating social-emotional learning for all students, providing trauma-informed training for teachers and staff, 42 “Welcome to the trauma-informed educator training series,” Mayerson Center for Safe and Healthy Children, accessed March 22, 2022. and providing counseling and more intensive support on and off campus for some students could provide supportive schooling environments beyond immediate crisis support. 43 “District student wellbeing services reflection tool,” Chiefs for Change, January 2022. A UNESCO survey suggests that 78 percent of countries offered psychosocial and emotional support to teachers as a response to the pandemic. 44 What’s next? Lessons on education recovery , June 2021. Looking forward, the State of California is launching a $3 billion multiyear transition to community schools, taking an integrated approach to students’ academic, health, and social-emotional needs in the context of the broader community in which those students live. 45 John Fensterwald, “California ready to launch $3 billion, multiyear transition to community schools,” EdSource, January 31, 2022.

The role of education technology in instruction is another much-debated element of reimagining. Proponents believe education technology holds promise to overcome human-capital challenges to improved access and quality, especially given the acceleration of digital adoption during the pandemic. Others point out that historical efforts to harness technology in education have not yielded results at scale. 46 Jake Bryant, Felipe Child, Emma Dorn, and Stephen Hall, “ New global data reveal education technology’s impact on learning ,” McKinsey, June 12, 2020.

Numerous experiments are under way in low- and middle-income countries where human capital challenges are the greatest. Robust solar-powered tablets loaded with the evidence-based literacy and numeracy app one billion led to learning gains of more than four months 47 “Helping children achieve their full potential,” Imagine Worldwide, accessed March 22, 2022. in Malawi, with plans to roll out the program across the country’s 5,300 primary schools. 48 “Partners and projects,” onebillion.org, accessed March 22, 2022. NewGlobe’s digital teacher guides provide scripted lesson plans on devices designed for low-infrastructure environments. In Nigeria, students using these tools progressed twice as fast in numeracy and three times as fast in literacy as their peers. 49 “The EKOEXCEL effect,” NewGlobe Schools, accessed March 22, 2022. As new solutions are rolled out, it will likely be important to continually evaluate their impact compared with existing evidence-based approaches to retain what is working and discard that which is not.

Charting a potential path forward

There is no precedent for global learning delays at this scale, and the increasing automation of the workforce advances the urgency of supporting students to catch up to—and possibly exceed—prepandemic education levels to thrive in the global economy. Systems will likely need resources, knowledge, and organizational capacity to make progress across these priorities.

Even before COVID-19, UNESCO estimated that low- and middle-income countries faced a funding gap of $148 billion a year to reach universal preprimary, primary, and secondary education by 2030 as required by UN Sustainable Development Goal 4. As a result of the pandemic, that gap has widened to $180 billion to $195 billion a year. 50 Act now: Reduce the impact of COVID-19 on the cost of achieving SDG 4 , UNESCO, September 2020. Even if that funding gap were closed, the result would be increased enrollment, not improvements in learning. UNESCO estimates that just 3 percent of global stimulus funds related to COVID-19 have been directed to education , 97 percent of which is concentrated in high-income countries. 51 “Uneven global education stimulus risks widening learning disparities,” UNESCO, October 19, 2021.

In many countries, shortages of teachers and administrators are just as pressing as the lack of funding. Many teachers in Uganda weren’t paid during the pandemic and have found new careers. 52 Alon Mwesigwa, “’I’ll never go back’: Uganda’s schools at risk as teachers find new work during Covid,” Guardian , September 30, 2021. Even high-income countries are grappling with teacher shortages. In the United States, 40 percent of district leaders and principals describe their current staff shortages as “severe” or “very severe.” 53 Mark Lieberman, “How bad are school staffing shortages? What we learned by asking administrators,” EducationWeek , October 12, 2021. Fully addressing pandemic-related learning losses will require a full accounting of the cost and a long-term commitment, recognizing the critical importance of investments in education for future economic growth and stability.

Countries do not need to reinvent the wheel or go it alone. Many existing resources catalog evidence-based practices relevant to different contexts, both historical approaches and those specific to COVID-19 recovery. For high-income countries, the Education Endowment Foundation, Annenberg’s EdResearch for Recovery platform, and the Collaborative for Student Success resources for states and districts in the United States provide research-based guidance on solutions.

In many countries, shortages of teachers and administrators are just as pressing as the lack of funding.

For low- and middle-income countries, materials developed in partnership with UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank include tools to support FLN, Continuous and Accelerated Learning, and teacher capacity (Teach and Coach). UNESCO’s COVID-19 Response Toolkit provides guidance across income levels. Collaboration across schools, regions, and countries could also promote knowledge sharing at a time of evolving needs and practices—from webinars to active communities of practice and shared-learning collaboratives.

Organizing for the response across these multiple levels is a challenge even for the most well-resourced and sophisticated systems. Our recent research found 80 percent of government efforts to transform performance don’t fully meet their objectives. 54 “ Delivering for citizens: How to triple the success rate of government transformations ,” McKinsey, May 31, 2018. Success will likely require a relentless focus on implementation and execution, with multiple feedback loops to achieve continuous learning and improvement.

The COVID-19 pandemic was indisputably a global health and economic crisis. Our research suggests it also caused an education crisis on a scale never seen before.

The pandemic also showed, however, that innovation and collaboration can arise out of hardship. The global education community has an opportunity to come together to respond, bringing evidence-based practices at scale to every classroom. Working together, donors and investors, school systems and districts, principals and teachers, and parents and families can ensure that the students who endured the pandemic are not a lost generation but are instead defined by their resilience.

Jacob Bryant is a partner in McKinsey’s Seattle office; Felipe Child is a partner in the Bogotá office, where Jose Espinosa is an associate partner; Emma Dorn is a senior expert in the Silicon Valley office; Stephen Hall is a partner in the Dubai office, where Dirk Schmautzer is a partner; Topsy Kola-Oyeneyin is a partner in the Lagos office; Cheryl Lim is a partner in the Singapore office; Frédéric Panier is a partner in the Brussels office; Jimmy Sarakatsannis is a senior partner in the Washington, DC, office; and Seckin Ungur is a partner in the Sydney office, where Bart Woord is an associate partner.

The authors wish to thank Annie Chen, Kunal Kamath, An Lanh Le, Sadie Pate, and Ellen Viruleg for their contributions to this article.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Reimagining a more equitable and resilient K–12 education system

COVID-19 and education: An emerging K-shaped recovery

Teacher survey: Learning loss is global—and significant

- Our Mission

Covid-19’s Impact on Students’ Academic and Mental Well-Being

The pandemic has revealed—and exacerbated—inequities that hold many students back. Here’s how teachers can help.

The pandemic has shone a spotlight on inequality in America: School closures and social isolation have affected all students, but particularly those living in poverty. Adding to the damage to their learning, a mental health crisis is emerging as many students have lost access to services that were offered by schools.

No matter what form school takes when the new year begins—whether students and teachers are back in the school building together or still at home—teachers will face a pressing issue: How can they help students recover and stay on track throughout the year even as their lives are likely to continue to be disrupted by the pandemic?

New research provides insights about the scope of the problem—as well as potential solutions.

The Achievement Gap Is Likely to Widen

A new study suggests that the coronavirus will undo months of academic gains, leaving many students behind. The study authors project that students will start the new school year with an average of 66 percent of the learning gains in reading and 44 percent of the learning gains in math, relative to the gains for a typical school year. But the situation is worse on the reading front, as the researchers also predict that the top third of students will make gains, possibly because they’re likely to continue reading with their families while schools are closed, thus widening the achievement gap.

To make matters worse, “few school systems provide plans to support students who need accommodations or other special populations,” the researchers point out in the study, potentially impacting students with special needs and English language learners.

Of course, the idea that over the summer students forget some of what they learned in school isn’t new. But there’s a big difference between summer learning loss and pandemic-related learning loss: During the summer, formal schooling stops, and learning loss happens at roughly the same rate for all students, the researchers point out. But instruction has been uneven during the pandemic, as some students have been able to participate fully in online learning while others have faced obstacles—such as lack of internet access—that have hindered their progress.

In the study, researchers analyzed a national sample of 5 million students in grades 3–8 who took the MAP Growth test, a tool schools use to assess students’ reading and math growth throughout the school year. The researchers compared typical growth in a standard-length school year to projections based on students being out of school from mid-March on. To make those projections, they looked at research on the summer slide, weather- and disaster-related closures (such as New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina), and absenteeism.

The researchers predict that, on average, students will experience substantial drops in reading and math, losing roughly three months’ worth of gains in reading and five months’ worth of gains in math. For Megan Kuhfeld, the lead author of the study, the biggest takeaway isn’t that learning loss will happen—that’s a given by this point—but that students will come back to school having declined at vastly different rates.

“We might be facing unprecedented levels of variability come fall,” Kuhfeld told me. “Especially in school districts that serve families with lots of different needs and resources. Instead of having students reading at a grade level above or below in their classroom, teachers might have kids who slipped back a lot versus kids who have moved forward.”

Disproportionate Impact on Students Living in Poverty and Students of Color

Horace Mann once referred to schools as the “great equalizers,” yet the pandemic threatens to expose the underlying inequities of remote learning. According to a 2015 Pew Research Center analysis , 17 percent of teenagers have difficulty completing homework assignments because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection. For Black students, the number spikes to 25 percent.

“There are many reasons to believe the Covid-19 impacts might be larger for children in poverty and children of color,” Kuhfeld wrote in the study. Their families suffer higher rates of infection, and the economic burden disproportionately falls on Black and Hispanic parents, who are less likely to be able to work from home during the pandemic.

Although children are less likely to become infected with Covid-19, the adult mortality rates, coupled with the devastating economic consequences of the pandemic, will likely have an indelible impact on their well-being.

Impacts on Students’ Mental Health

That impact on well-being may be magnified by another effect of school closures: Schools are “the de facto mental health system for many children and adolescents,” providing mental health services to 57 percent of adolescents who need care, according to the authors of a recent study published in JAMA Pediatrics . School closures may be especially disruptive for children from lower-income families, who are disproportionately likely to receive mental health services exclusively from schools.

“The Covid-19 pandemic may worsen existing mental health problems and lead to more cases among children and adolescents because of the unique combination of the public health crisis, social isolation, and economic recession,” write the authors of that study.

A major concern the researchers point to: Since most mental health disorders begin in childhood, it is essential that any mental health issues be identified early and treated. Left untreated, they can lead to serious health and emotional problems. In the short term, video conferencing may be an effective way to deliver mental health services to children.

Mental health and academic achievement are linked, research shows. Chronic stress changes the chemical and physical structure of the brain, impairing cognitive skills like attention, concentration, memory, and creativity. “You see deficits in your ability to regulate emotions in adaptive ways as a result of stress,” said Cara Wellman, a professor of neuroscience and psychology at Indiana University in a 2014 interview . In her research, Wellman discovered that chronic stress causes the connections between brain cells to shrink in mice, leading to cognitive deficiencies in the prefrontal cortex.

While trauma-informed practices were widely used before the pandemic, they’re likely to be even more integral as students experience economic hardships and grieve the loss of family and friends. Teachers can look to schools like Fall-Hamilton Elementary in Nashville, Tennessee, as a model for trauma-informed practices .

3 Ways Teachers Can Prepare

When schools reopen, many students may be behind, compared to a typical school year, so teachers will need to be very methodical about checking in on their students—not just academically but also emotionally. Some may feel prepared to tackle the new school year head-on, but others will still be recovering from the pandemic and may still be reeling from trauma, grief, and anxiety.

Here are a few strategies teachers can prioritize when the new school year begins:

- Focus on relationships first. Fear and anxiety about the pandemic—coupled with uncertainty about the future—can be disruptive to a student’s ability to come to school ready to learn. Teachers can act as a powerful buffer against the adverse effects of trauma by helping to establish a safe and supportive environment for learning. From morning meetings to regular check-ins with students, strategies that center around relationship-building will be needed in the fall.

- Strengthen diagnostic testing. Educators should prepare for a greater range of variability in student learning than they would expect in a typical school year. Low-stakes assessments such as exit tickets and quizzes can help teachers gauge how much extra support students will need, how much time should be spent reviewing last year’s material, and what new topics can be covered.

- Differentiate instruction—particularly for vulnerable students. For the vast majority of schools, the abrupt transition to online learning left little time to plan a strategy that could adequately meet every student’s needs—in a recent survey by the Education Trust, only 24 percent of parents said that their child’s school was providing materials and other resources to support students with disabilities, and a quarter of non-English-speaking students were unable to obtain materials in their own language. Teachers can work to ensure that the students on the margins get the support they need by taking stock of students’ knowledge and skills, and differentiating instruction by giving them choices, connecting the curriculum to their interests, and providing them multiple opportunities to demonstrate their learning.

Coronavirus and schools: Reflections on education one year into the pandemic

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, daphna bassok , daphna bassok nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy @daphnabassok lauren bauer , lauren bauer fellow - economic studies , associate director - the hamilton project @laurenlbauer stephanie riegg cellini , stephanie riegg cellini nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy helen shwe hadani , helen shwe hadani former brookings expert @helenshadani michael hansen , michael hansen senior fellow - brown center on education policy , the herman and george r. brown chair - governance studies @drmikehansen douglas n. harris , douglas n. harris nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy , professor and chair, department of economics - tulane university @douglasharris99 brad olsen , brad olsen senior fellow - global economy and development , center for universal education @bradolsen_dc richard v. reeves , richard v. reeves president - american institute for boys and men @richardvreeves jon valant , and jon valant director - brown center on education policy , senior fellow - governance studies @jonvalant kenneth k. wong kenneth k. wong nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy.

March 12, 2021

- 11 min read

One year ago, the World Health Organization declared the spread of COVID-19 a worldwide pandemic. Reacting to the virus, schools at every level were sent scrambling. Institutions across the world switched to virtual learning, with teachers, students, and local leaders quickly adapting to an entirely new way of life. A year later, schools are beginning to reopen, the $1.9 trillion stimulus bill has been passed, and a sense of normalcy seems to finally be in view; in President Joe Biden’s speech last night, he spoke of “finding light in the darkness.” But it’s safe to say that COVID-19 will end up changing education forever, casting a critical light on everything from equity issues to ed tech to school financing.

Below, Brookings experts examine how the pandemic upended the education landscape in the past year, what it’s taught us about schooling, and where we go from here.

In the United States, we tend to focus on the educating roles of public schools, largely ignoring the ways in which schools provide free and essential care for children while their parents work. When COVID-19 shuttered in-person schooling, it eliminated this subsidized child care for many families. It created intense stress for working parents, especially for mothers who left the workforce at a high rate.

The pandemic also highlighted the arbitrary distinction we make between the care and education of elementary school children and children aged 0 to 5 . Despite parents having the same need for care, and children learning more in those earliest years than at any other point, public investments in early care and education are woefully insufficient. The child-care sector was hit so incredibly hard by COVID-19. The recent passage of the American Rescue Plan is a meaningful but long-overdue investment, but much more than a one-time infusion of funds is needed. Hopefully, the pandemic represents a turning point in how we invest in the care and education of young children—and, in turn, in families and society.

Congressional reauthorization of Pandemic EBT for this school year , its extension in the American Rescue Plan (including for summer months), and its place as a central plank in the Biden administration’s anti-hunger agenda is well-warranted and evidence based. But much more needs to be done to ramp up the program–even today , six months after its reauthorization, about half of states do not have a USDA-approved implementation plan.

In contrast, enrollment is up in for-profit and online colleges. The research repeatedly finds weaker student outcomes for these types of institutions relative to community colleges, and many students who enroll in them will be left with more debt than they can reasonably repay. The pandemic and recession have created significant challenges for students, affecting college choices and enrollment decisions in the near future. Ultimately, these short-term choices can have long-term consequences for lifetime earnings and debt that could impact this generation of COVID-19-era college students for years to come.

Many U.S. educationalists are drawing on the “build back better” refrain and calling for the current crisis to be leveraged as a unique opportunity for educators, parents, and policymakers to fully reimagine education systems that are designed for the 21st rather than the 20th century, as we highlight in a recent Brookings report on education reform . An overwhelming body of evidence points to play as the best way to equip children with a broad set of flexible competencies and support their socioemotional development. A recent article in The Atlantic shared parent anecdotes of children playing games like “CoronaBall” and “Social-distance” tag, proving that play permeates children’s lives—even in a pandemic.

Tests play a critical role in our school system. Policymakers and the public rely on results to measure school performance and reveal whether all students are equally served. But testing has also attracted an inordinate share of criticism, alleging that test pressures undermine teacher autonomy and stress students. Much of this criticism will wither away with different formats. The current form of standardized testing—annual, paper-based, multiple-choice tests administered over the course of a week of school—is outdated. With widespread student access to computers (now possible due to the pandemic), states can test students more frequently, but in smaller time blocks that render the experience nearly invisible. Computer adaptive testing can match paper’s reliability and provides a shorter feedback loop to boot. No better time than the present to make this overdue change.

A third push for change will come from the outside in. COVID-19 has reminded us not only of how integral schools are, but how intertwined they are with the rest of society. This means that upcoming schooling changes will also be driven by the effects of COVID-19 on the world around us. In particular, parents will be working more from home, using the same online tools that students can use to learn remotely. This doesn’t mean a mass push for homeschooling, but it probably does mean that hybrid learning is here to stay.

I am hoping we will use this forced rupture in the fabric of schooling to jettison ineffective aspects of education, more fully embrace what we know works, and be bold enough to look for new solutions to the educational problems COVID-19 has illuminated.

There is already a large gender gap in education in the U.S., including in high school graduation rates , and increasingly in college-going and college completion. While the pandemic appears to be hurting women more than men in the labor market, the opposite seems to be true in education.

Looking through a policy lens, though, I’m struck by the timing and what that timing might mean for the future of education. Before the pandemic, enthusiasm for the education reforms that had defined the last few decades—choice and accountability—had waned. It felt like a period between reform eras, with the era to come still very unclear. Then COVID-19 hit, and it coincided with a national reckoning on racial injustice and a wake-up call about the fragility of our democracy. I think it’s helped us all see how connected the work of schools is with so much else in American life.

We’re in a moment when our long-lasting challenges have been laid bare, new challenges have emerged, educators and parents are seeing and experimenting with things for the first time, and the political environment has changed (with, for example, a new administration and changing attitudes on federal spending). I still don’t know where K-12 education is headed, but there’s no doubt that a pivot is underway.

- First, state and local leaders must leverage commitment and shared goals on equitable learning opportunities to support student success for all.

- Second, align and use federal, state, and local resources to implement high-leverage strategies that have proven to accelerate learning for diverse learners and disrupt the correlation between zip code and academic outcomes.

- Third, student-centered priority will require transformative leadership to dismantle the one-size-fits-all delivery rule and institute incentive-based practices for strong performance at all levels.

- Fourth, the reconfigured system will need to activate public and parental engagement to strengthen its civic and social capacity.

- Finally, public education can no longer remain insulated from other policy sectors, especially public health, community development, and social work.

These efforts will strengthen the capacity and prepare our education system for the next crisis—whatever it may be.

Higher Education K-12 Education

Brookings Metro Economic Studies Global Economy and Development Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy Center for Universal Education

Emily Markovich Morris, Laura Nóra, Richaa Hoysala, Max Lieblich, Sophie Partington, Rebecca Winthrop

May 31, 2024

Online only

9:30 am - 11:00 am EDT

Annelies Goger, Katherine Caves, Hollis Salway

May 16, 2024

Mission: Recovering Education in 2021

THE CONTEXT

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused abrupt and profound changes around the world. This is the worst shock to education systems in decades, with the longest school closures combined with looming recession. It will set back progress made on global development goals, particularly those focused on education. The economic crises within countries and globally will likely lead to fiscal austerity, increases in poverty, and fewer resources available for investments in public services from both domestic expenditure and development aid. All of this will lead to a crisis in human development that continues long after disease transmission has ended.

Disruptions to education systems over the past year have already driven substantial losses and inequalities in learning. All the efforts to provide remote instruction are laudable, but this has been a very poor substitute for in-person learning. Even more concerning, many children, particularly girls, may not return to school even when schools reopen. School closures and the resulting disruptions to school participation and learning are projected to amount to losses valued at $10 trillion in terms of affected children’s future earnings. Schools also play a critical role around the world in ensuring the delivery of essential health services and nutritious meals, protection, and psycho-social support. Thus, school closures have also imperilled children’s overall wellbeing and development, not just their learning.

It’s not enough for schools to simply reopen their doors after COVID-19. Students will need tailored and sustained support to help them readjust and catch-up after the pandemic. We must help schools prepare to provide that support and meet the enormous challenges of the months ahead. The time to act is now; the future of an entire generation is at stake.

THE MISSION

Mission objective: To enable all children to return to school and to a supportive learning environment, which also addresses their health and psychosocial well-being and other needs.

Timeframe : By end 2021.

Scope : All countries should reopen schools for complete or partial in-person instruction and keep them open. The Partners - UNESCO , UNICEF , and the World Bank - will join forces to support countries to take all actions possible to plan, prioritize, and ensure that all learners are back in school; that schools take all measures to reopen safely; that students receive effective remedial learning and comprehensive services to help recover learning losses and improve overall welfare; and their teachers are prepared and supported to meet their learning needs.

Three priorities:

1. All children and youth are back in school and receive the tailored services needed to meet their learning, health, psychosocial wellbeing, and other needs.

Challenges : School closures have put children’s learning, nutrition, mental health, and overall development at risk. Closed schools also make screening and delivery for child protection services more difficult. Some students, particularly girls, are at risk of never returning to school.

Areas of action : The Partners will support the design and implementation of school reopening strategies that include comprehensive services to support children’s education, health, psycho-social wellbeing, and other needs.

Targets and indicators

2. All children receive support to catch up on lost learning.

Challenges : Most children have lost substantial instructional time and may not be ready for curricula that were age- and grade- appropriate prior to the pandemic. They will require remedial instruction to get back on track. The pandemic also revealed a stark digital divide that schools can play a role in addressing by ensuring children have digital skills and access.

Areas of action : The Partners will (i) support the design and implementation of large-scale remedial learning at different levels of education, (ii) launch an open-access, adaptable learning assessment tool that measures learning losses and identifies learners’ needs, and (iii) support the design and implementation of digital transformation plans that include components on both infrastructure and ways to use digital technology to accelerate the development of foundational literacy and numeracy skills. Incorporating digital technologies to teach foundational skills could complement teachers’ efforts in the classroom and better prepare children for future digital instruction.

While incorporating remedial education, social-emotional learning, and digital technology into curricula by the end of 2021 will be a challenge for most countries, the Partners agree that these are aspirational targets that they should be supporting countries to achieve this year and beyond as education systems start to recover from the current crisis.

3. All teachers are prepared and supported to address learning losses among their students and to incorporate digital technology into their teaching.

Challenges : Teachers are in an unprecedented situation in which they must make up for substantial loss of instructional time from the previous school year and teach the current year’s curriculum. They must also protect their own health in school. Teachers will need training, coaching, and other means of support to get this done. They will also need to be prioritized for the COVID-19 vaccination, after frontline personnel and high-risk populations. School closures also demonstrated that in addition to digital skills, teachers may also need support to adapt their pedagogy to deliver instruction remotely.

Areas of action : The Partners will advocate for teachers to be prioritized in COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, after frontline personnel and high-risk populations, and provide capacity-development on pedagogies for remedial learning and digital and blended teaching approaches.

Country level actions and global support